RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

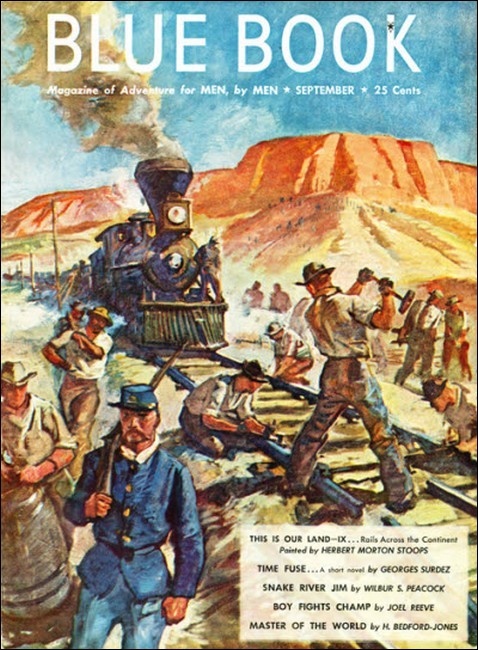

Blue Book, September 1946, with "Master of the World"

Alexander of Macedon had conquered most of the world, and his legions were rolling toward Carthage when—a wily little priest strangely presented to him the Sphinx Emerald.

THE Egyptians called it Sekhet-Amit, meaning "field of palm trees;" to the Romans, it was the Oasis of Jupiter Amon; we know it as Siwa Oasis, one of the ancient and sacredly renowned spots in the world, in the Sahara Desert, three hundred and fifty miles west from Memphis.

It is, and always has been, extremely difficult of access. In the old days before the practical Romans put that Asiatic beast, the camel, to work as a means of desert transport, to reach Siwa was almost impossible; and yet, from the earliest prehistoric time, kings and generals and many lesser men made the pilgrimage hither, and desert caravans from Mid-Africa to Carthage. For the oasis was sacred to Amon, father of the gods, and the oracle of Amon told the future to those who asked, and gave wisdom. So suppliants came to worship the god and seek the aid of the oracle.

In this February of 331 B.C., the spot was an area of about ten square miles, abundantly watered by springs and wells, with about a hundred thousand date palms and a luxuriant growth of olives, figs and other trees. One of the chief wells was accounted miraculous, because it was warm by night and cold by day, and still is so. Under the trees crouched a weird little old temple, home of the god Amon, the Zeus of the Greeks and Jupiter of the Romans.

To this far-famed spot was coming the even more renowned Alexander as a suppliant, a regal suppliant, for he had conquered Persia and Asia Minor and Egypt with his barbarous Macedonian army, and was now rumored to be marching on Carthage and Rome in order to complete his world-conquest and to pillage the West as he had pillaged the East. This rumor had run insistently for months, as Psammon was well aware.

Psammon, they called him; "Little Amon," or more politely "The Little One." He bore a Carthaginian name but only the priests knew it. This oasis was nominally Egyptian, but was at the edge of territory ruled by Carthage, and Egypt had fallen to pieces so the Carthaginian power was largely felt hereabouts.

With the whole Western world atremble at thought of Alexander and his tough Macedonians, who met all opposition by slaughtering the men and raping the women, it was natural that Carthage should have an agent here at Siwa. Psammon had been here a long time. If the great world-conqueror got this far west of Egypt, he would assuredly go on to loot Carthage and Sicily and Rome, and nobody westward enjoyed the prospect.

Psammon was not happy about it either, and with far greater reason. As agent of Carthage, he had been ordered to perform a task so utterly impossible as to appear almost ludicrous, were it not so tragic—one at which kings and empires had failed and gone down to dusty ruin. How, then, could he hope to fulfill it, seeing what he was?

He was a cheerful, sharp-eyed little man of incredible agility; not deformed in any way but merely small—a trifle over three feet in height. His features were aquiline, finely chiseled, mellow as old ivory; his eyes were a very keen and bright blue, usually laughing and sparkling with life.

But now, as he sat talking with the high priest of the temple, they were vexed and gravely helpless. He spoke without reserve, for he could be quite frank with this one person.

"Tell me, help me!" His voice was musical, deep in timbre. "I am ordered to stop this Alexander, to turn him away from Carthage, to avert his destroying legions. How can I hope to do such a thing? The very thought is absurd. Darius, the king of kings, with all his satraps and legions, could not do it. Yet the Suffetes, the rulers of Carthage, order me—me!—to do it. Tell me how!"

His slender-fingered, deft hands, which had been playing with a green stone, fell motionless. He peered at the gentle old priest in perplexity.

"Little One, you touch upon a mystery," said the older man in kindly accents. He liked this dwarf. "If the gods desire a thing done, they inspire men to do it—how, we can never tell in advance. I advise you to pray to them."

"Pray? Bosh! Something better than prayer is needed," snapped the little man. "What I need is some practical help."

"Where can you seek it, except from the gods?" said the old priest. "As to Alexander, we have been kept fully informed by couriers. He comes with his staff and a few guards, not many. Why? Because he fully believes himself to be the son of Zeus or Amon, and wishes this confirmed by our oracle, which is respected by the whole world—"

"Everyone knows he's the son of Philip, King of Macedon," blurted Psammon.

The priest smiled. "His mother Olympias is a woman given to wild, ecstatic furies at times. King Philip called the boy a bastard. She announced that the god had visited her on her wedding-night. Alexander has believed this, always."

"And if you know what's good for you, you'd better confirm it!"

"My son, the priests of the oracle say only what the god puts into their minds. We're honest fellows; but I grant you we would never ask a thunderbolt to hit us. This Alexander is a proud, haughty young man, the greatest today living on this earth: yet he is given to gentle and noble impulses, like all men truly great."

"He, the greatest upon earth, and I the least," murmured Psammon unhappily. "And how am I to turn him from his course of conquest, with all the wealth of Carthage almost in his hand?"

"That I know not, my son; only the gods could tell you," said the old priest frankly. "We must favor this man when he comes, for his heart is noble and honest. Little One, I'll help you in any way possible. Yet every man must seek within his own heart how to accomplish his work in this world; the discovery adds to his merit. What is that green stone you've been juggling?"

The stone seemed to vanish of itself and was tucked into Psammon's girdle.

"That? Oh, an emerald, of a sort," he replied. "You remember the Egyptian who died here last year—the queer fellow Nekht, who lived like a hermit? He gave it to me when he was dying. Well, I must get a letter written to give the courier you're sending, so I'd best get home and write it.... Just when does Alexander get here?"

"Within two or three days, if storms don't detain him on this desert. This is the season of south winds, which bring sand."

Psammon left the temple, looking like a small boy as he flitted among the thick trees, making for his own hut on the outskirts of the village. He had been here some years and was held in great respect by the natives and priests alike. He himself liked the oasis far better than noisy Carthage; what with caravans and visitors, there was no loneliness here, yet the desert nights and days held a mystic peace, the very sunlight was different. It was a simple life, and none despised him for being a dwarf.

IN his hut, he made fire, lighted his palm-oil lamp, dipped a

reed pen and wrote a brief report, which he signed and sealed.

This done, he composed himself, took from his girdle the green

stone and set it close to the lamp so that light was diffused

through it. Then he sat motionless, looking into the lump of

beryl.

An emerald, yes, a huge stone from the Egyptian mines, not of good color. The Egyptian wanderer, the man Nekht who had settled here as a hermit, had given it to him before dying, and Psammon found the thing precious and wonderful beyond belief.

In itself, it was marvelous, for the flaws and bubbles which all beryl contains had settled together at one point, forming an image. Not a fancied shape but a real and perfect semblance of the Great Sphinx, so real it seemed supernatural—a miniature Sphinx sitting there within the gem! Whence had the stone come? A royal jewel, the dying wanderer had said, a relic of the ancient Egyptian kings—well, no matter. Egypt was a Greek country now.

NOT that Psammon cared about Egypt; he was a Carthaginian,

heart and soul. Having long ago accepted his small stature as a

thing beyond help or cure, he gave to his city a fierce

allegiance of spirit, serving it as secret agent with a pure

devotion. He had nothing else in life to serve. Such single-

mindedness had given him a sharp perception of men and agile

mental powers beyond the normal. Perhaps this was why he found

something else, and far more wonderful, in this emerald than the

mere tiny Sphinx.

In the flashing sunlight, or beside the lamp, intent study of the stone rewarded him with strange thoughts, strange mental effects; those green depths of beryl inspired him with nameless but ecstatic beauties, intangible sensations. He imagined pictures of Eastern lands he had never seen, of glorious regal cities and buildings, of vast horizons and marching armies and magnificent panoplies of war by land and sea—he, who would never bear arms, dreamed of such things.

He was no fool. He knew that this ecstasy was due to the jewel, and that it was a sort of auto-hypnosis. It was like a hashish dream, but he never used hashish. The green scintillating depths of the emerald suggested such visions to him and left his brain happily content, fed with aspirations and ambitions he could never know in real life.

He heard a step at his door. Swift as a cat, he reached out, clawed the emerald from sight, and looked up as a man stepped into the hut. It was the courier who had come with the last news of Alexander, and who was leaving shortly for Carthage.

"Greetings, Little One," he said. "Have you a letter for me to take to the Suffetes?"

"Aye," replied Psammon. "Sit and rest. I want to ask a thing or two."

They sat talking of the greatest present subject on earth—the Macedonian. The courier told of his occupation of Egypt—an incredibly young man filled with flaming energy and convinced that a god, the greatest of the gods, had sired him. He was generous to a fault, lived the divine madness of youth to its full, had conquered half the known world and was reaching for the rest.

For some centuries past, Greece and its ideas had gradually molded the thought and politics and religion of all the eastern lands. The gods of various countries and peoples had melted together. In Macedonia, the great Amon of Egypt was worshiped, being identified with Zeus and with Min and other gods. Even here at Siwa, where in the temple was preserved a huge supposed meteorite, Amon was worshiped as the god of meteorites. To any simple soul this theology was a very confusing matter. But Alexander, as the courier made clear, was coming hither not as a conqueror but as a suppliant for the god's favor.

"Some say he'll go on to Carthage and Rome," said the courier. "Others that he'll return to Egypt, then lead his army east to India. Nobody knows. I doubt if he himself knows yet just what he'll do. He's a young man, impressionable, unformed. He has marched a hundred and forty miles west along the coast, then has headed on the hundred-and-eighty-mile march south to this oasis, and the gods have protected him."

"Well, here's my letter." Psammon gave him the sealed scroll. "Whatever happens here, word will be sent on by another courier without delay."

A little more talk, and the courier departed. The Little One did not resume his play with the emerald. He went out into the chill February night and walked to the miraculous well. This had a constant temperature, which made its water seem cold on hot days and warm on chill nights. Psammon made his ablutions, and then took his way to the odd little temple, more ancient than man's memory. A few lights burned there. It was not guarded; there was nothing to steal and no one to steal anything in this sacred place. Passing through the courts and chambers, he came to the very sanctuary of the god, and there made his prayer for light and guidance. His perplexed, helpless mind was in sore need of it.

A queer, dim, ghostly place, this sanctuary. Seventy years earlier, Lysander the great king of Sparta had come hither, seeking the words of the oracle. An army of Cambyses the Persian had perished on the way hither; kings and wanderers had come from all parts of the earth, and had left votive offerings which were hung about the walls. In the depth of the chamber was the god himself.

A portable ceremonial boat stood there, covered with gold leaf; and in this boat or ark stood the figure of Amon, unlike that of any other known god. It was a long, shield-shaped slab of green stone set with precious stones. In the center was a circular hollow, in which stood the tiny figure of Amon himself. This peculiar object was a relic of the most ancient times in Egypt, before the dynasties of kings began; in those primitive days the shield-shaped slabs were supposed to have fallen from heaven as meteorites—and perhaps one had done so, originally. In this ancient temple, aloof from all the world, had lingered the primitive form of worship. The great green stone slab and the tiny figure of Amon in its center were relics of prehistoric days. Both were sacred objects.

Psammon, staring at the thing, felt a sudden catch of the breath. An odd notion had jumped into his head—a notion startling him with its daring, with its breadth and scope. As though Amon himself had answered his prayer! This thought awed him.

Yes, the thing was possible, but to face it took courage. He knelt, eyes wide on the dim golden boat, trying to recapture the threads of that fleeting visionary idea. His own share in the business troubled him not at all. Alexander was one enigma; but the conqueror's character was well known. That courier had painted him aright. He was coming here, a rapt young mystic, an honest believer in the oracle; he would credit anything.

The priests of Amon here were honest too; this might be an even greater problem. They honestly believed that the oracle was the inspiration of the god. None of them would indulge in any sacrilege or falsity.

"Well, that's not necessary," thought the Little One excitedly. "I can do that myself; let them give forth their own oracles! The high priest, however, is wiser than the rest, and he's in command. He has a broader outlook, too; he's keenly anxious to make a friend of this Macedonian. Hm! I think he'll listen to reason—at least, in part. I'll be the one who'll take the chances—the littlest man in the world against the greatest!"

THE notion took shape in his head. Fantastic as it was, his

shrewd brain saw its possibilities, realized fully the queer

powers instinct in the Sphinx emerald, and how those powers might

well affect Alexander—if properly guided. Yes, it might be

done. He knew everyone in the village, he knew women who would

help him with their clever fingers. First, he must make sure of

the high priest—and the less the priest knew about his

scheme, the better.

He bowed before Amon, thanked him for inspiration and help, and went back home, where he lay awake a long time, thinking about the idea.

Next morning he sought the presence of the high priest. The whole oasis was in a hubbub of work and excitement. It was February, and the last of the date crop had long since been gathered from the hundred thousand date trees scattered over the oasis; but now these had to be cleaned up—the old spathes and bunches removed, the dead leaves cut away. Everyone was at it, and the smoke of the burning hung like a cloud against the sunlight. Even the temple precincts were being cleaned up a bit.

THE morning sacrifice was long over, and the old high priest

was breakfasting when the little shape of Psammon settled down

respectfully before him.

"Well, Little One? Have you thought of something?"

"Yes, master. You will show this great man the sanctuary of Amon?"

"Naturally."

"He is a conqueror, the son of the god," said Psammon. "He is a taker, master. He will see the little figure of Amon—he will take it."

"Eh?" The priest started. "No, no! He would not dare such a sacrilege here—"

"It is no sacrilege for a son to take his father's image," said Psammon. "But I have thought of something far better. First, hide the image in a corner somewhere. Replace it in the green slab with something you can offer him as a gift—something so evidently made by the gods themselves that it will satisfy and delight him."

The priest frowned at him uncertainly.

"Your words are full of wisdom, Psammon. But we have no such sacred object."

The Little One took from his girdle the Sphinx emerald, and gave it to the priest.

"Look at this carefully, master. It is a great emerald. That fellow Nekht said it had been made by the gods themselves and once belonged to the royal treasure of Egypt. Such a gift would delight even Alexander, greatest of men. I think Lord Amon himself made me think of this last night, when I was praying to him."

The high priest, naturally, was one who took nothing for granted. He looked at the emerald and saw the Sphinx set far inside it. With an exclamation, he took it to the morning sunlight and gave it a minute examination, seeking any possible cleavage. But there was none. That marvelous figure was obviously formed by the flaws in the beryl itself.

He came back, sat down, scratched his shaven pate and stared at Psammon in awe.

"By the horns of Amon, my son! This is a wonderful thing; I never saw anything like it. Why, it is worth uncounted gold! It would make you rich!"

"Gold is of small worth to me," said the Little One almost sadly. "I shall hate to part with it, true; one becomes attached to the stone. But, in the service of Amon, I must do what I must. If you will use it for this purpose, I give it freely."

The high priest looked into those strange blue eyes, intently. His grave features relaxed and smoothed; perhaps some deep and silent intelligence passed between the two men.

"Come to the sacrifice in the morning," said the priest. "I shall give you the special blessing of Amon, my son. And, whenever you have need of gold, I'll gladly supply it. I am asking no questions. I know there is no evil in your heart. No one else here knows that this emerald belonged to you?"

"No one. I have never shown it to a person, except yourself."

"Very well. I shall do as you suggest; it is quite obvious that Amon himself sent the emerald here for this purpose, so I shall tell no lies in saying it is a gift to Alexander from the god his father—"

He checked himself quickly. Psammon made no sign, and the priest smiled. This odd dwarf was a fellow to be trusted more than most; it would be quite safe to make use of the emerald as suggested, and save the precious little image from possible confiscation by the great visitor. The image, like the huge green stone slab, was thousands of years old, and priceless.

That Alexander intended coming to Siwa, was no secret; it had been openly announced for many months. No preparation had been made against his coming; no one knew what to do. He had taken Egypt and was now its king, and this was Egyptian territory. The wily businessmen of Carthage had Psammon here for agent, as they had agents everywhere, but they, too, had done nothing except give hopeless commands. Everyone was helpless and paralyzed before this young man and his tough, killing, raping Macedonians before whom no army, no city, could stand.

The Little One was bitterly conscious of his own abject inferiority as a person; but now he was far too busy to think about it. At the sacrifice of the emerald, which really hurt, he had started something which he had to finish, and this he himself must accomplish with none to aid. Now it was the littlest man against the greatest—person to person, in a battle not of force but of strategy.

The temple had no guest accommodations. One of the larger houses in the village was being prepared for Alexander and his suite; the troops with him could camp in the open. He would be here on the morrow; a runner had just come in with the news. Beds, lights, food—everything had to be conjured out of nothing.

Amid this bustle, Psammon glided with agility, seeing now one person, now another; he had to have certain things made, he had to make others himself, and time lacked. It would have been much nicer, he muttered, if the god had sent his inspiration a little earlier. Alexander would be here only a couple of days, just long enough to make the usual sacrifices and consult the oracle. It was certain that in Egypt he would have seen the huge Sphinx near the Pyramids, with its great red-painted face and gay head gear, facing toward the rising sun—indeed, it represented Ra- Harmachis, the sun-god. Upon this fact, and upon his own judgment of the hero's mental reaction to the emerald, the Little One was founding his entire plan of campaign.

By afternoon, he had everything under way, and made a trip to the house being prepared for the royal guest. He studied it carefully. He himself could clamber about on these mud houses, with their jutting beams, like a fly, but in this instance he dared risk no error—just one mistake would ruin him most terribly. Then he sat himself down to a barber and had his head shaved completely, like that of a priest, amid many scurrilous jests flung at him from all sides. He made no response and the jesters, disappointed, went their ways.

That night he labored late, completing what he was making, and early in the morning picked up the sandals and robe the women had made for him—taking no more sewing than a child's dress. He got the dark stain he needed, too; with his white skin, this was imperative.

WHILE the excited village buzzed and labored that day, Psammon

sat and looked at these things, and at the false little stubby

beard he had made; and growing fear sat clammily upon him. Such

an easy little thing to talk about and plan—but as it drew

closer, he became bitterly afraid. He began to count the cost of

one mistake, and it terrified him. He spoke Greek, of course, and

there was no reason to fear any mistake—yet he feared.

Alexander, after all, was the greatest man in the world. When he

left here he would be a god.

The Little One wished vainly that he could have the emerald again, even for an hour. To sit and look into it would restore his confidence and hearten him beyond measure; but this was impossible. In the heat of the day, he stole away to the temple, as the next best thing. He could not get into the sanctuary; all were barred from it. He bowed himself in prayer to Amon for help and went back to his hut.

Here he stripped and applied the darkening juice to his whole body, head and face. With this darker skin, his bright blue eyes made even more startling contrast, as he knew. Then he slept away the afternoon, until the trumpets called him.

Alexander would have trumpets, of course. The Little One, peering from openings in his hut of thatched palm-fronds, saw the march come in from the northern highway. No camels—the animal was as yet unknown in Africa. Men who marched afoot, with the swinging march-step of veterans, donkeys following with the baggage. Iron men, these, but none of them the equal of their leader, who led the way with his staff around him. The eye went to him as to a magnet.

Clean-shaven among the bearded Greeks, wearing no armor because of the desert sun, the golden fillet of a king about his hair, Alexander looked what he was—young, impetuous, gawking about in curiosity at the great oasis, waving his hand in return to the shouts of acclaim from the people. He looked unwearied, fresh, in contrast to the fagged officers and men around. His eager laugh was dazzling; he radiated youth, energy, ardent expectancy. He was the greatest man in the world, and knew it, and played up to the role with almost boyish delight. Then they were past.

THE Little One sat on his mat, breathing hard, chewing dates

from a wooden bowl. He had seen the Macedonian! The priests were

greeting him now, making him welcome. The lord of two worlds,

king of Upper and Lower Egypt, of Macedonia, of Tyre, of

countless other lands afar, Alexander, third of the name, son of

Philip—now to be proclaimed son of the god Amon, like many

another potentate. The swift twilight died into darkness, the sun

was gone.

Presently came one of the villagers who had promised to make report. He sat on the mat with the Little One, excitement in him, and spoke.

"They've been bathing at the holy well. The priests put him and his staff in the house. They would take nothing but a few dates. They say he eats the rations of the other Greeks. It's been a hard march; tonight they rest. They are soldiers—a few guards have been placed already. Tomorrow there'll be ceremonies in the temple, and a feast. Ha! Those Greeks have iron feet, Little One—not one of them even limps! And they say birds guided them across the desert after a sandstorm, when the guides lost the way."

Presently the villager departed and the Little One sat, alone and afraid.

That man, like the sun in splendor—Psammon could not help being afraid. How could he hope to impose upon that splendid being with his silly little story? Yet, as he thought about those Greek faces and their look of awe at everything around them, a faint hope revived in him. Alexander was a man—no more. He had marched these hundreds of miles afoot because of credulity. His belief in his own greatness and divinity was mere credulity. Greatest man in the world—yes, from the physical, the material viewpoint. But his own vast credulity and superstition would tend the more to make him credit the words of the Little One.

"The one difficulty now is to reach him, because of the guards," Psammon told himself, his shrewd brain wakening. "They'll be weary. After an hour or so they'll relax. There's a full moon, but it comes up late—so much the better. Moonlight is always more deceptive than darkness, thanks to the gods!"

Waiting was hard. He went outside and sat in the darkness, listening to a distant howling of jackals. Here in the village, everything was silent. Alexander and his trumpets and his guards had gone to rest. Strange, how few men he had brought with him on this long march! Still, that was just good sense, thought Psammon; the fewer men, the less food and water to transport.

Across the mind of the Little One crept a wandering thought that startled him. If he could reach this greatest man in the world alone, asleep, as he purposed—if he could do this, then why not with a knife? Not impossible at all. The thought held a peculiar and almost deadly allure that tempted him. His own hand, tiny, feeble, might send to hell this man at the summit of all earthly grandeur....

He laughed at himself, mockingly.

"You were not made for murder, Little One!" he muttered. "Besides, if you accomplish your design, then you are greater than he, far greater. And, above all, he is a handsome, superb, magnificent creature—such a creature as you might have been but for the accident of birth! Admire him, worship him, but harm him not. Preserve your own greatness, your own integrity—for it's all you have, Little One."

The high palm fronds were silvering. He rose and went into the hut. He laid out the robe that the women had made for him, and on it put the other articles. He rolled it all up into small compass, then slung the bundle about his neck and let it fall over his shoulders, so as not to impede him. He dared not stop now to think. He must go now—now—without pause!

He stole forth, a shadowy figure no larger than a child, stripped to his loincloth, feet bare, weaponless.

Moonlight struck athwart the high trees, with their platforms whence the spathes were pollenized and the dates plucked. Everything beneath was dark. Down the haphazard village street slipped the Little One; the dogs knew him and barked not. There ahead was the large house given over to the royal guest. He approached cautiously; yes, he might have known it. Guards walked up and down. He froze, watching them. Here and there about the house lifted high, leaning palms that overhung the roof. Little by little, he moved toward the one of these he had previously chosen.

Like a gliding shadow, he gained it. No smooth-barked tree, this. The stubs of old branches, cut off year by year across a century of life, protruded all along the thick trunk, forming it, giving secure hold for agile feet and hands. He moved like a dim nightshade up the leaning trunk, came abreast of the flat bare roof where no one slept tonight, and paused. All empty here. No alarm from the sentries on the ground—the worst lay behind him!

Heart leaping, he let himself hang, and dropped. He was on the house-roof.

The night was chill, with a keen wind out of the north. No sleeping in the patio on such a night; the rooms would be used, and he knew which the hero would occupy. He opened his bundle and spread it out on the mud roof, and began to work with the articles in it. He had gained confidence now; as the moment neared to meet the greatest man in the world face to face, his heart quieted, his nerves relaxed.

IN a room prepared for him with such splendor as the oasis

afforded, Alexander lay sprawled upon the couch, sleeping

heavily. His scanty baggage was on the floor; beside his pillow

lay baldric and sword. The chamber was dimly lighted by a night-

lamp that burned on a pedestal; also, a wide ray of moonlight

struck down through an unshuttered window.

This young man, literally the master of the world, stirred a little in his sleep as a whisper sounded in the room. It was repeated again and again, very softly, the Greek words stealing through the veil of slumber. Perhaps he had been dreaming those very words in ecstatic forecasting of the morrow when the oracle of the god would confirm them.

"Son of Amon!—Son of Amon!"

The sleeper turned, threw out an arm. Once again that soft, quiet whisper stole upon the room and penetrated to the drowsy brain. The eyes of the sleeper opened a little, his head moved. Then, as he caught sight of the figure standing close beside him, his eyes flew wide open.

A queer figure, standing motionless in the ray of moonlight—a small, yet perfect figure.

A priest of Amon, or perhaps even Amon himself. The shaven head denoted a priest, as did the priestly robe, the ornamented sandals. His beautifully formed features wore the stubby short beard of a priest. He held the scepter of rule and the little "Tau cross" of life. His eyes were striking in the moonlight, blue and luminous as the eyes of a painted priest sculptured in some temple wall.

A slight gasp escaped Alexander. With a sudden movement he came to one elbow.

"Am I dreaming—is there some one here?" he muttered.

"You are dreaming, son of Amon, lord of the two worlds," came the gentle reply. "I have come to you in dream with a message of great importance. Can you hear me?"

"Yes, yes," assented the young man, eagerly. "I want you to answer my questions—"

"What you want, Alexander of Macedon, does not concern me. Save your questions for the temple oracle," came the gentle voice, with more definite rebuke than Alexander had heard in many a year. "Attune your ears to what I have to say. You must remember the words. You must act upon them, for now I am pointing you toward your greatest destiny—if you read my words aright."

To Alexander this apparition certainly seemed real, as does many a vagrant dream of night; it had, indeed, an appalling reality. The small size of this priest or god was astonishing in the extreme, and must be supernatural. Then there was the broad ray of moonlight that heightened the mystic appearance, surrounding it with an ineffable majesty. Assuredly no harm was intended.

"Very well," said Alexander. "I listen."

"Within the sanctuary of the temple," came the strange message, "lies a gift which Father Amon, the lord of gods and men, has sent for your acceptance. Take it and fear not, but use it aright. This sacred and precious object is god-given. Sit with it alone and look into its heart, where you will see a Sphinx. Study it, listen to what it says to you. Bear in mind that the Great Sphinx faces ever to the east, whence comes all light. In the east lies your destiny, your greatness. Remember this, my son. Your destiny lies in the east with the springing sun, Ra- Horus of the morning strength."

"I hear and obey," murmured Alexander in accents of awe.

"The truth of my words will become evident to you," went on the unearthly visitor. "Son of Amon, greatest of mankind, turn your face ever eastward toward the light! Hold these words in your heart. Remember them when you gaze into the depths of the green stone, the sacred gift of the gods...."

The voice lessened, the figure of the speaker receded—it was gone from the moon-ray. Alexander leaped upright. He fancied a rustle of robes. One instant he hesitated, then went darting from the room, his voice pealing out to the guards, calling at them to stop anyone who tried to pass, to guard all exits from the house.

LIGHTS sprang up, weapons were bared, armed guards came

running. No one had passed out below, said the guards, nor had

anyone entered. Alexander led a search of the whole place,

curious rather than perturbed, found no one at all, and finally

admitted that he had had a dream of a ghostly visitor. No one, of

course, thought to look up at the palm trees leaning against the

house-top. But the search quickly died out at news that it was

only because of a dream. In this sacred spot, with visitors

invariably rapt and ecstatic, dreams were a shekel a dozen. The

startled alarm died out in carefree laughter....

Later next day, Alexander and his staff officers made the ritual visit to the temple and were received by the priests in solemn ceremony. In due time he was conducted alone into the holy of holies by the high priest, who made him welcome in the name of his father Amon-Ra.

The boat or ark, shimmering in its gold-leaf coating, was displayed to him. He gazed curiously at the immense, shield- shaped slab of green stone and at the cavity in its center, now occupied by the lumpish, poorly shaped emerald. This, announced the high priest impressively, was a gift for him that had been sent by the gods in token of their favor. Alexander took the emerald. When he looked carefully at it and saw the image of the Sphinx inside the beryl, he knew what the dream had meant.

He said nothing of the dream, however.

Now came the great thing for which he had tramped these hundreds of miles across desert wastes—his consultation of the oracle. He asked the questions he had prepared, and the priest replied, with the usual ritual, nor was there any trickery considered. The one man had come hither at cost of much hardship in the implicit belief that the god Amon would answer him. The other man undoubtedly believed, with equal firmness, that his replies were inspired by Amon.

The hero was definitely acknowledged as the son of Amon, his career being the best proof of this. He would continue victorious in the coming years, for Amon had conferred upon him the dominion of the known world. Later, Alexander wrote his mother Olympias a full detailed account of his visit to the shrine; and added, in a certain naive manner, that he had also asked some highly secret questions, promising to retail the god's answers next time he saw her. This statement, in view of her admittedly peculiar share in the whole business, must have left the haughty Queen of Macedonia in considerable suspense.

His errand was finished, and after making his gifts to the shrine, he departed and his staff officers consulted the oracle in turn. To this, Alexander paid scant attention. He went back to his quarters and there remained most of the afternoon, closeted with the great emerald given him by the gods.

During the next two days, no more, the illustrious visitor remained at Siwa, then departed as he had come. His plans were not secret; his guards knew them and discussed them. His new city of Alexandria was being laid out; he was anxious to get back for the foundation ceremony. Also, he had to organize the rule of Egypt, and having already marched his troops four thousand miles from home, was anxious to see Greece again. So, with his bearded warriors, he marched away on the northern highway.

FOR a long while Alexander kept the Sphinx emerald beside him,

and when across the Euphrates in the Far East, one day gave it to

his veteran general, Ptolemy—who was destined to become in

later days the King of Egypt.

All this had nothing to do with the dwarf, Psammon. He kept sedulously to his hut while the Greeks were here, not venturing abroad lest he be seen. On the evening after the departure, he came to the temple quarters of the high priest, accepted a glass of wine, and handed over a sealed scroll.

"Send this to Carthage by the next courier, if you will," he said. "That ends it. My task is done. The great man will move his armies eastward, not westward."

The high priest studied him curiously.

"You seem very sure, my son. However, I ask no questions; I well know that your mind is nimbler and deeper than mine. The great man was charmed with the gift given him; it delighted him beyond measure."

"As well it might," said the Little One, a trifle bitterly. "I regret the loss of that emerald, selfishly. It was a wonderful thing. Still, it served its purpose. I am sure that Father Amon put it into my heart to use in that manner."

"And now, I suppose that you'll go to Carthage and some great reward?" asked the high priest.

Psammon sipped at his wine and grunted.

"I? What am I—not even a man!"

"Nonsense. You were greater than the king of kings who was just here, my son."

"True, in one sense. But what rewards can mean anything to me? In the cities, among normal men, I have no place. Money means little or nothing to me; I cannot buy myself a new body, I cannot find a place into which I can fit," said the Little One earnestly. "The only peace and happiness I've ever known has been in this holy place devoted to the service of Amon."

"Then stay here, where you are welcome." The high priest spoke slowly, thoughtfully, watching the agile little face with its queer blue eyes. "These Berber people who live here know you, like you, respect you. The temple is greatly in your debt."

"Yes?" Psammon peered at him sharply. "What is in your mind?"

The high priest smiled. "The priests here with me are good men, but few in number and not particularly blessed with brains, my son. Under Persian rule, the whole priestly organization has fallen to pieces; now the Greeks have taken over Egypt and no one knows what will happen. Did you see those Berbers—light- skinned folk, like you—who came here last week from that oasis to the south?"

Psammon nodded. "I remember a party came, yes."

"They brought with them a young woman; they came seeking help for her. She was twenty years of age, yet no larger than a child—a sweet thing, kind, gentle. Suppose I sent to them, telling them to return here with her? Suppose I arranged for you, as for my own son, a marriage with her. Suppose that you were to remain here, not as a useless visitor, but as a servant of Amon, a temple attendant, a novice priest—I merely show you facets of what is in my mind. You can sketch the rest for yourself."

The priest rose. "Stay, finish your wine, think it over. I must go and see that the temple lights are extinguished. I'll be back soon."

Psammon set down the cup, folded his hands, stared at the lamp as he sat alone.

It was real—incredible, but real. He had never even dreamed of such a thing. A novice priest—a temple attendant! A wife— physically cursed of the gods, like himself, yet like himself perfect and infinitely blessed in spirit—why not? This high priest, he well knew, was never hasty or ill-considered in any matter; if he favored the match, it might be accounted a favorable one.

No one in gaudy, cheap, self-seeking Carthage had ever breathed such kindness to him; and Psammon gulped a little at the thought of it. Then the big thing took hold of him.

A NOVICE priest in the temple service—his whole life

given to the worship of Amon here in this spot of sanctity so far

removed from the noisy world! The mere mention of such a

possibility by the high priest showed that it must have been well

weighed and approved beforehand. Size meant nothing in a priest.

A lifetime of peaceful service, of useful living—why, the

prospect was breathtaking! In those words was offered a future,

such a future as Psammon had never envisioned or hoped for!

Presently the high priest returned, seated himself, and looked at his visitor. Psammon sat silent, rapt, unmoving. The lamplight sparkled on tears stealing out upon his cheeks.

"Well, my son? Have you thought about it?"

"There is something—I must tell you," said the Little One unsteadily. "Something that I did the other night—"

"Wait." The priest lifted a hand to check the words. "Did your action bring harm to anyone, to yourself?"

"No."

"Then it was not wrong. A thing is wrong only if it brings harm. This is no excuse for crime, my son; indeed, the prospect of how our actions may bring harm is appalling. Tell me nothing; the less I know the better. I am quite certain that the gods work their will in singular ways past our understanding. Someone mentioned a dream that came to the great Alexander while he slept here—a very odd dream about the god Amon in most unusual form. I made no inquiries; it was not my affair. None the less, Father Amon is quite able to work out the lives of those who trust in him. You have a firm, superior type of mind, my son. I shall be glad to welcome you to our little circle of life, here in the desert."

Psammon lifted his head, brushed the tears from his cheeks and smiled.

"I—I would not trade places now," he said, "with the greatest man in the world!"