RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

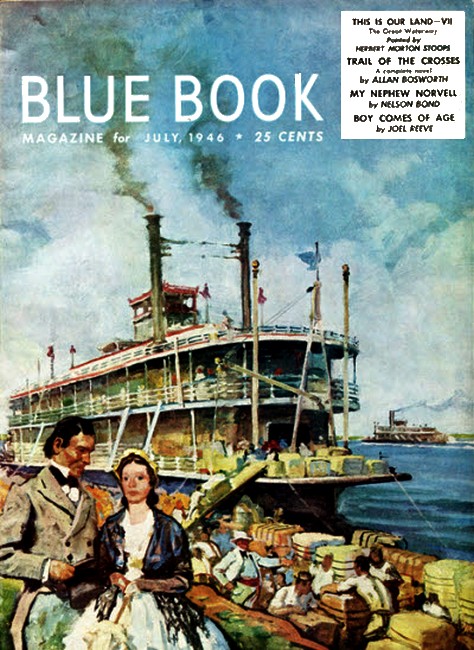

Blue Book, July 1946, with "Red Sky over Thebes"

The Sphinx Emerald passed into other hands—to reappear centuries later when conquering Cambyses came storming into Egypt with his Persian legions...

NEKHT was his name. With a wooden-fork plow and a bullock, he was tilling his field outside the tiny Nile village of peasants, when the Greek captain came from Thebes with the news. An odd fellow, Nekht—tall, thewy, bronzed as any other farmer in the village, but with a hawk-nose and quick eyes of striking intelligence. He usually kept them half shut, and in the village itself passed for a fool. No one here knew or suspected his secret.

He lived alone with his mother, who told the Greek, named Peleus, where to find him. Nekht saw him coming along the edge of the fields, and recognized him; for although the soldier wore a tunic over his armor, the proud lift of the head and the step of authority could not be hidden.

"The captain of the temple guards," Nekht said, and pulled the bullock out of the furrow. "That means a message for me. What now, friend Peleus?"

"Greetings," said the other, who knew him well, "and news. I have a boat waiting; the high priest of Amon wants you."

"And the news?"

"If the Nile ran the other way, the water would be red. There's hell to pay, but the news must keep until we're afloat."

"I'll take the bullock home, and go," Nekht said simply. "Come along."

He unyoked the bullock from the plow, and they started back to the village. As to the news, Nekht had heard enough to guess what it must be; he was already seeking beyond the words, mentally. He, of all people, needed no telling that Egypt was a leaky boat in a bad storm shaking the world. During the past two hundred years the great country had been gradually disintegrating. Still powerful, still crammed with all the looted riches of the earth, it had been ruled by Assyrians, Ethiopians, Greeks—anyone strong enough to seize the throne and defend the desert frontiers. The present Pharaoh, Samthek, was the grandson of an army general who had done just this, bringing Egypt up to a fragment of its former greatness, with Greek help.

THE last native dynasty, that of the great Ramses, had

conquered practically the known world, pouring into Egypt an

enormous flood of treasure and slaves. Softened, slothful, the

old hard Egyptian race became easy-going. Now, in this fateful

year of 528 B.C., Egypt still existed intact, like soft ripe

fruit ready for the taker. Greeks had flooded in like a swarm of

summer flies. The army was composed of Greeks—and the

Persians were coming. During the past two years, the Persian

ruler Cambyses had been pushing armies across the northern

deserts, intent upon plucking this ripe fruit.

Yet one faint breath of hope lingered; somewhere in this great land, unknown, was a descendant of the last royal Egyptian line. Who? Where? Nobody knew. But the chief priests of the gods had announced it as fact. Prophecy said that some day all foreigners would be expelled, and the royal line of Pharaohs would again lift Egypt to greatness. When? Perhaps this year, perhaps a hundred years hence; but the hope lingered.

Four soldiers in the boat, Greeks like Peleus, saluted as he and Nekht appeared and got in; the boat pushed off, swung out into the current, and was on its way to Thebes, still the greatest city on earth. Nekht and Peleus sat together in the stern.

"The news?"

"The worst," said Peleus. "Cambyses has captured Pelusium and is marching up the Nile. The army is completely destroyed, the Pharaoh a prisoner. Phanes of Halicarnassus, commander of the Greek troops, went over to the Persians. They'll be in Thebes in two or three days. They're coming up by ship."

Nekht caught his breath. The worst, indeed! Egypt was no more.

Like a symbol, the shapes of ruined buildings along the river- banks caught his eye. Once barracks had stood here every few miles, each post holding two hundred iron chariots and equipment. Now all were empty, ruined, forgotten. Egypt was forgotten too. The blow was crushing.

"What—what hope for the city, for Thebes the glorious?" he asked, dry-lipped.

"None," Peleus replied. "No army there, except for a few of us guards—and we're Greeks. A huge, sprawling, unkempt city like Thebes can't be defended. Already refugees are pouring out. Cambyses, we hear, has given the loot of the city to his Persian legions. The gods are dead, Nekht. Egypt's dead."

"I'm not dead," said Nekht. "And there's a girl—I must see her."

"You and your girls!" jeered the soldier. "You may be a student, a friend of the chief priest of Amon—but you're a peasant, a villager, food for Persian steel. Your girl is one of thousands destined for Persian couches. We Greeks are safe enough, as allies and friends of the conqueror; but you Egyptians are as dirt under Persian sandals."

Nekht said nothing. It was bitterly true. To Peleus, he was only a farmer, a mere nothing, like all his people—grass doomed to the fire.

He himself knew better. He was one of a few hundreds chosen from those people—chosen for descent, for character, for vigor—and secretly given most careful training, as soldiers and rulers; being made initiates of the Mysteries and heritors of all the higher learning preserved in the priestly castes. Men in each generation were thus chosen and made ready for the day when Egypt should rise again—and one among them all was the heir of the royal line, his secret guarded in bitter darkness for his own safety.

"We hear that Memphis is already taken and looted," Peleus went on. "Until the King and army arrive, we serve as we are; then, naturally, we join our fellows. If you want to get your girl out of the city, Nekht, I'll lend you a hand. Call on me. Some of us have our eyes on the temple treasury—we'll stick together."

NEKHT broke into soft, bitterly ironic laughter; the temple

guards meant to loot it! Everything was falling to pieces. Yet he

liked this Peleus—a strong, tough Greek from Samos, highly

intelligent and famed as a soldier.

"Not a bad idea, Peleus," he said, watching the river reaches. "Perhaps I can tell you a thing or two about the temple treasury that you don't know, too."

The Greek gave him one lightning-swift glance. Well he knew there were temple secrets known to no guard—and this brown fellow educated in the temple of Amon might well be aware of them. He drew closer.

"A trade, friend Nekht! You and me alone—not now, but when the need comes. Keep it in mind."

Nekht gave him a nod, and said no more. The river below them was covered with all manner of boats; the panic flight from Thebes was under way. Escape? There was none, yet the wild thousands fled in terror of the coming wrath—fled to starve, to wander into the southern deserts; and chariots raised clouds of dust on the highways in desperate hope of reaching the Nubian frontier.

So they came to the vast city of Amon-Ra, whose temples and palaces surpassed anything in the world—the "hundred- gated," so the marveling Greeks called it, because of the countless and enormous gateways of these gigantic structures. In the temple quarter along the Nile was little confusion, the guards from Karnak and Luxor keeping fair order here. From the remainder of the city, smoke rose in places, denoting that the mob was looting and burning; but no one cared—no one except Nekht. He, catching the arm of Peleus, spoke rapidly.

"Friend, I'll take you up on your bargain. Whether I'll be detained an hour or a day with the chief priest, I don't know. The afternoon's at an end. When it gets dark, send word to the house of the Royal Architect that I'll come when free—get the message to the hands of the Lady Amenartis. Will you?"

Peleus nodded. "Take it myself," he said. "Come along, and I'll turn you over to the beloved of Amon, who'll taste Persian steel before he knows it."

A tough, cynical fellow, this Greek, but a good man in his way, with a laugh often in his eye. Nekht did not hesitate to trust him—a little.

The two men made their way to the towering Karnak temple, where the high priest of Amon lived. They passed the guards and crossed the vast, almost empty courts where thousands had once worshiped; but few believed in the gods these days. The lofty columns and long walls, sculptured and painted gloriously, flitted past, and they came to the innermost court. Here, said the guards, a conference of priests was under way, and Peleus pushed on into the holy of holies—a high-pillared chamber where sat a dozen priests. A mere dozen, out of the thousands in Thebes, and these all high priests of various gods.

"Here is the man you wanted, my lord," called Peleus, standing on no ceremony. Then, giving Nekht a clap on the shoulder, he went his way.

AN old man, wrinkled, shaven-headed, left the others and came to Nekht. This was Amon's high priest, greatest man in Thebes.

"Greetings, my son," he said. "Go into my study. You'll find wine and food there; help yourself. I'll join you immediately. You know the way."

Nekht obeyed, passing into a small room holding only the tables of scribes and that of the priest. Obviously the temple service had broken down: wine and food were set on the tables haphazard; clothes were scattered about; documents and letters were strewn on the floor. Being hungry, Nekht helped himself to the food, poured a goblet of wine, and was gulping it when the high priest joined him.

"Well, the end has come," said the old man abruptly. "Peleus gave you the news?"

"Such as he had, yes."

"Worse has arrived. The Persians are on the way upriver; they may be here tonight. They're killing, looting everything. Memphis was put to the flames. Cambyses himself is with the vanguard—a drunken despot now maddened by triumph, who hates our gods and us. Those of us not murdered will become slaves. No mercy at all."

"And your plans?"

The old man gestured hopelessly. "We have none, except to die. Everything's ended. Egypt is lost... I didn't get you here merely to rail at fate, however. The time foreseen has come. You will live while others, all of us, perish; you'll have the traditions, the written scripts, the secrets, to revive Egypt once more, you or your descendants. I must show you how to reach the things that have been put aside for that day."

"What about the temple treasures?" queried Nekht.

A thin, horrible laugh came from the high priest, who poured some wine and drained the cup. "Let the gods protect their own gold and silver—the treasure is too huge to be moved, anyway. But now, listen well! You know the underwater chambers, the secret rooms I showed you when last here?"

Nekht assented with a nod.

"They hold the crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt, the records, the chief relics, and all the treasure that can be packed in to fill the place; and the river has been turned in. The slaves who did the work are dead; I soon will be dead; this leaves you as the only person who can reach that hidden treasure in case of need—you and your children. Some day it will serve to rebuild Egypt. Were this entire temple destroyed, the cache would remain intact to serve its purpose."

Again Nekht silently assented, and waited.

"You," said the old man, "are the last Egyptian, last of the blood of the great Ramses; tell your sons these secrets, that they may tell their sons, and some day Egypt will have a Pharaoh of the ancient blood. Go back to your village. Be a simple farmer. That is your one chance of salvation, Egypt's one future hope. Nothing of your existence as such is known, but there may be danger from these Greeks who for so long have been a part of Egyptian life. They may have picked up rumors. Now—what are your plans?"

"To get out of the city with Lady Amenartis, the daughter of the Royal Architect. We love each other. If we can get to my village, we'll be safe."

Nekht spoke simply and to the point. The old man peered at him.

"Good. I can help you a little. The maddened people are fighting up and down the wharves for the boats. I'll show you where one is hidden safely, and how to reach it. But first I have a gift for you, left in keeping of the high priest by the last Ramses, twelfth of the kings thus named."

So saying, he took from his table a small wooden box, and from the box a little object wrapped in cloth—two objects, in fact. One was a doubly convex glass, used by Chaldean priests in studying the stars, and inherited from them as a deep secret by the priests of Egypt. The other was a lumpish green stone, such as Nekht had never seen.

"A bit of glass, and an emerald," said the old man. "The one will enlarge the other. No time now for lengthy explanations... But tuck them away and use them at leisure. Now we must go, and I'll show you the secret of the boat. A long way to go."

"Wait!" exclaimed Nekht. "An emerald, you say?"

"Yes, from the crown jewels, originally. A wondrous thing, too; guard it well, but for the present put it out of sight. We must go."

The old man was impatient, anxious, filled with fears, as well he might be.

Two hours later Nekht made his exit from the temple, free; in his girdle was knotted the Sphinx emerald and the glass. He paused at the entrance, seeing Peleus, and spoke to him. The Greek took his arm.

"Hello! You still here? By Zeus, man, but you can't get away now—no horses left, no boat obtainable without a savage fight! I hear the Persians are already at the city outskirts. Where's your girl? I left the message for her."

"I'm going for her now. I'll be back here. You'll be here?"

"Probably. We want to get into the temple treasury before the Persians arrive."

"I can help you to that," said Nekht. "Wait for me."

"Well, perhaps," agreed the other doubtfully. "You'd better get hold of a Greek outfit—the Greeks are safe. Look at the sky! Damn the fools!"

It was now full night, and red flares from blazing houses dotted the horizon. Nekht broke away and departed. He had some distance to go into the residential quarter, but at first found everything deserted and quiet here, though northward lifted a far, thin, terrible sound—distant screaming that ceased not. He hurried faster. If the Persians were already at hand, there was bitter need for haste.

Flitting shapes suddenly were in the dark street—fugitives. Stone buildings were few here. Only temples and palaces were of stone. The great mass of structures were of wood, perhaps with stone fronts; many were of fire- resistant palm trunks, towering high. An abrupt torrent of screams and shouts turned the corner ahead as a chariot and two horses came tearing madly into the crowd—some noble or priest trying for a belated escape. Blood flowed blackly on the stones. Horses and drivers were stabbed; the whole street was blocked by the uproar of ferocity; corpses or wounded lay everywhere.

Nekht somehow got past the tumultuous, heaving blockade. Light came from the flaring sky ahead. He swung into a street where frantic swarming crowds were threaded by killers of the mob or by slaves, striking and tearing like wolves. Lights flickered through the houses. The sound of screaming voices began to dull everything else. Yet all this was merely a beginning, a symptom of the flood of death which was to come.

Thankful for the plain cotton robe that did not single him out for attack, he hastened on his way; nearly there now—but from northward was increasing momentarily a thunderous dull roar mounting athwart the sky. He knew what it meant; Persians pouring in from the suburban districts, driving before them a furious, helpless mob of many thousands, killing as they came, looting houses, going to every extreme of rapine. The greatest city in the world was going down in flames and blood. All the northern sky was now a ruddy conflagration that threw the streets into plain sight with its reflected glare.

ARRIVED at last, and the house dark, apparently deserted.

Nekht went to the side entrance, and a voice spoke—that of a slave. Recognized, he was led inside. In the central patio he found Amenartis, dark and cool and composed. She gave him her hand, then turned to the crowd of slaves grouped at one side.

"You are free," she said. "I cannot help you. Go where you like; take whatever pleases you. Well, Nekht! Thanks for the message. Where my father is, I don't know. The family left this afternoon. I knew you would come."

"We'd better be gone too, and lose no time about it," he said.

"Why? What good?" She looked at him in the ruddy glare. "Everything's gone. The old order's dead, my dear. Do we just walk out—into nothingness?"

"Hardly that. Life in a village up the Nile, as a farmer's wife, providing we can get there. I have a way, if you are willing."

"Certainly," she said. "A new order, eh? Well, I'm confused, bewildered, helpless. It's like the end of the world, in very truth. So I'll trust to you."

"Things are pretty tough in the streets, and we must reach the temple. Find me a weapon of some kind; leave your jewelry and fine gown and get a cheap robe and a shawl to cover your head. Smear your face with dirt. Do it fast. I'll wait here."

She vanished into the house. The slaves came up and crowded around Nekht. He spoke frankly to them, told them that order, law and government were gone; the Persians were looting the city—they had best go, be free, try to save themselves. Inane, useless words, but all he could offer. They melted away like shadows and left him waiting, alone, while into the reddened sky lifted the sounds of hell. The wild roar was everywhere now, closer, filled with horror and ferocity.

The end of an order—a people, a civilization! She had spoken aright. Beauty and knowledge were being trampled into a mire of blood and tears this night. The Persian and his gods had come to destroy Egypt and her ancient deities—no mercy, no pity.

She came, wrapped in a common blue robe, hair streaming, face and hands smeared with ashes; yet she was calm enough. She put a belt and sword into Nekht's hand.

"This was my father's greatest treasure, Nekht; it belonged to the great Ramses."

With fumbling fingers he buckled on the belt, then took her hand. They went out by the side entrance, and were caught in a whirlwind of screaming, running and fighting humanity pressed by mailed figures—Persians and Greeks, cutting a way through to reach the houses. Nekht drew her to one side, coolly waiting a clear space, then seizing it and darting ahead. They were on their way. No force could avail here; coolness could get them through—and did.

They watched incredible scenes—the helpless fleeing mob had gone stark mad. Soldiers came driving along, laughing, singing, killing any in their path, smashing into houses, seeking loot everywhere. Nekht drew Amenartis away from one furious rush, holding her against a house-wall, waiting.

"Why the temple?" she breathed at his ear. "Will it be spared?"

"No!" he said. "But we'll find safety there, can we reach it."

Like a ravening force of wind, the fury was in all the houses. Beautiful inlaid ivory was trampled on in the streets; delicate screens were smashed; rich broideries were underfoot; figures of gods and men were flung down from the windows; rare furniture was hurled afar—the loot of the world, here stored for centuries, was given over to savage destruction, and corpses were piled up in the highways. Syrians, Chaldeans, Carians, desert Arabs, Iraki, Greeks of the islands and from all the Greek cities—this flood from the north was avenging the woes and fulfilling the hatreds of thousands of years upon the once proud and mighty mistress of the world; and after the looting came fire.

THROUGH the madness Nekht and Amenartis worked their

way—the two persons in all this horror who knew whither

they were going. Half a dozen times Nekht had to use his sword;

once a running burst of insensate Greeks sent them rolling amid

the corpses, but passed on; at length they came into comparative

quiet, and in the glare saw the great high gateways of the Karnak

temple, barred and silent, before them. Nekht sent a shout

pealing up; he heard a reply from Peleus, and led Amenartis

forward to the tiny door in the gate. It was opened, and they

were inside.

"Well done," said Peleus. "The end's getting close here—they'll come in from the sides and back. The priests are all in the temple, awaiting the decree of the fates."

Nekht rubbed splashes of blood from his face.

"I can offer you sure hiding, and your will of the temple treasures, which no one else can find," he said. "The only condition is that you and your friends remain safely until we can get away—perhaps a few days. I can supply a boat, also."

"By the gods, you do better miracles than the priests!" cried Peleus. "How many of us? There are six of us in my own crowd."

"Get them, and let's be going. I'm about done in."

Peleus swung away.

Amenartis came close, with a low, awed word.

"But Nekht—the temple treasures! What are you about to do?"

"What the high priest instructed me to do, to insure our safety. The priests know that for them it's the end... Here, I've got a couple of bad slashes on my right arm. Bind them up, will you? Take a bit of my robe—"

Before she had the cuts bandaged, Peleus came back hastily, with five others of the mailed guards.

"Hurry, if you've some place to go!" he exclaimed. "They're coming in the back now!"

Nekht led the way straight back through the temple courts. In one court they came on a number of Persian and Greek soldiers wandering, sword in hand, staring aimlessly at the magnificent sculptured walls. These paid them no attention, and Nekht turned out into the side courts, the glare in the sky making everything bright as day. He came to the spot indicated by the high priest, counted the pillars, and behind one of these pointed to a tall slab of stone.

"Peleus! Push, all of you, on the right side of this slab."

The Greeks obeyed with a will. The great slab moved on a pivot; one end swung out, and an opening was disclosed.

"In, everyone!" ordered Nekht, as a sudden burst of voices rose. "Quickly! We'll find lamps inside—"

INSIDE with the men Nekht felt in the darkness until he found

the rope attached to the counter-weights. He attacked it with his

sword, cut it, and there was a heavy clash as the slab swung

shut. The Greeks cursed in alarm.

"It's all right," said Nekht. "I couldn't trust you fellows—but there's another way out, fear not. Now we're safe. Feel around for a shelf with lamps on it."

This was found, and presently a lamp was alight. The silence here was profound; the ray of light showed a down-sloping passage. This led to a number of rooms furnished for living; one was stacked with food of all sorts. Nekht stopped at a door and held up his lamp.

"There you are, Peleus," he said. "That goes to the temple treasury. Run along and help yourselves; it can't get away. I'm for a wash-up and rest. Come back to the rooms when you're ready."

He turned away, wearily, and went back to rejoin Amenartis, who had waited in one of the living-chambers.

AN odd, and in some ways a dreadful place, these deep underground rooms constructed to hide treasures and priests from passing dangers; now there were no priests here—for above was no passing danger, but the end of everything.

Any small party could remain here undiscovered for a long time. Food, a running current of water, vents for air, an access to the Nile—everything needed was here. Nekht washed, showed Amenartis where to bathe, then dropped on a couch, and was asleep in two minutes, while overhead, Thebes was dying horribly.

When Nekht wakened at long last, Amenartis was asleep and the lamp burning low. He took it and went to the water-clock in another chamber. Ten hours had passed. Peleus and his friends, exhausted by frantic looting, lay snoring with treasures of gold and precious things heaped around them. His lamp refilled, Nekht returned to Amenartis, who was sitting up, yawning. He had to tell her the whole truth about himself, and did so.

"You and I, my dear, are less than the dust; look at the larger pattern of things," he concluded. "Egypt, the country, the nation, is prostrate under Persia today. Her gods are being destroyed, her civilization wiped out. But a hundred, two, three hundred years from now, she will rise again as a nation; the priests have taught me this. And when she does, one of our children's children will be at her head. The greatest treasures, the records of the gods and of the people, are safely hidden away beyond any discovery, to serve her in that day."

The hand of Amenartis tightened on his; her luminous dark eyes flashed and glowed under the emotion of his words.

"Truly magnificent, Nekht!" she exclaimed.

He shook his head. "No; for us, quite the contrary. You must realize what it means before making your choice. I can take you to safety and leave you, to work out your own future; or you can remain with me. What will this mean? Life as a farmer's wife in a little village. Entire sacrifice of your past, of the future you dreamed. Careful hiding from any discovery of the secret. Poverty, work, no more soft easy living. Make no hasty choice. Here, see what the high priest gave me, his last gift. There is deep reason, but I know it not."

He unknotted the little packet from his girdle and got out the glass and the emerald. They looked at the stone together, beside the lamp.

As a precious object, the emerald was disappointing—a rather shapeless lump of beryl, pale in color, poorly polished. Under the glass, all this changed. The flaws and angular bubbles of the crystal came together in one place to form a distinct, clearly cut image of the Sphinx. Under this, on the bottom of the stone, had been cut a single hieroglyphic—that showing the human eye, emblem of Thoth or Horus, the god of truth. This, at first look, was all. Wonderful as it was, this was all.

"Why did he give me this?" Nekht mused thoughtfully. "Far more beautiful and wonderful things were his, by the thousand. Why this?"

"Perhaps—for me," said Amenartis. "Let me keep the thing a while."

"Gladly. An odd toy," he said carelessly. "Well, you see the difficulties ahead?"

"Yes. They terrify me," she said frankly. "I can't be hasty, impulsive; what you say frightens me. The sacrifice of so much, Nekht! Never to have any hope, any ambition, of better things for ourselves—that's terrible, hard even to realize."

"I know. I was brought up to it from boyhood, as my children must be." A smile touched his thin, hard lips. "I'm a good farmer, Amenartis."

"I can't be a farmer's wife," she said flatly. "Not for ever. I warn you!"

"Take your time, my dear. There's no hurry," he said. "It's not what you can, but what you will. That's one of the great lessons of the Mysteries—the use of man's free will. We're not just puppets of fate, you know."

She grimaced. "The Mysteries are gone. Everything's gone!"

"True. We have to begin anew the task of building—everything. A slow, sorry job."

"Then why do it?" she flashed. "Because your own fathers began it? Because you were trained to it? Because the priests told you to do so?"

"No. I could go off and be a soldier with Peleus if I chose—and I'd much sooner do that, too." He smiled at her. "A matter of decision, I suppose. Duty, perhaps. I must do what is given me to do, for I've so decided, my dear. As you must, without compulsion."

"I was a fool ever to fall in love with you," she said gloomily.

THE Greeks were stirring amid their gold, and so the

conservation ended.

Now began a strangely unreal period when, as the Greeks said, they were like people stranded beyond the world's end: These Greeks were hardy, tough, decent fellows; their contempt for Nekht as an Egyptian changed into respect ere long. The food was coarse but sufficient; there was wine, and water to mix with it. The inner chambers were crammed with a vast, incalculable treasure of all kinds, gathered over centuries.

"But you can't carry it all away," said Nekht, when Peleus called him into conference with them later that day. "Whether some of you come back later, if you can find your way, is of no consequence. I advise you to take your time and make bundles of what each one can carry."

"And you know how to get out of here?" questioned one man.

Nekht assented. "I, and I alone."

"Then when do we depart?" Peleus demanded. "They'll be sacking the city, up above, for days to come."

"That's what I fear," Nekht answered. "When we leave, I want to reach safety, not run into madness. You agreed to land me upriver at my village."

"The promise holds, my friend. But when?"

Nekht pointed to the clepsydra—the water- clock.

"That marks the hours; I'm keeping track. On the seventh night of our stay, I think it will be safe to leave."

They consulted about this, and all agreed. The Greeks went off to play with the treasure.

NEKHT rejoined Amenartis, and found her beside the lamp,

examining the great emerald with help of the enlarging glass.

She looked up to ask:

"Have you given this stone any close examination?"

"No."

"Do it, then." She gave him the glass. "Look into it for a while. See what it tells you."

To humor her whim, he complied, smiling.

He knew rather vaguely that the Great Sphinx by the Pyramids, and its mate, over in the eastern hills, had been erected by the Ancient People in the days before any dynasties began, and were accompanied by shrines to Thoth, or Horus. It was obvious that the little figure composed of flaws and bubbles was a freak of nature—yet this shape in the emerald was so exact, so perfect, as to awaken superstition. It was an impossibility—yet here it was before his eyes.

And to his surprise, there was something further in the beryl, something unseen but felt distinctly. He searched those greenish depths with growing intensity, becoming more aware of this intangible something. Then he sat back and reflected. Acquainted as he was with the inner secrets of the Mysteries and the curiously involved instruction of the priesthood, he perceived that here was some manner of hypnosis induced by looking into the heart of the crystalline beryl—a mental effect, not a trick or contrivance.

This fascinated him; and he pored anew, glass in hand. What he could distinctly sense was a feeling of radiant happiness, a pleasant strength and heartening. He looked up as Amenartis returned.

"I see what you mean, my dear. Tell me what it says to you."

"Peace," she replied, cool and composed as ever. "Assurance, firmness—oh, I hardly know! It just gives one the feeling—does it do that to you?"

"Yes, but in another way," he said thoughtfully. "I think the secret is that it says no one thing to all, but something different to everyone. It makes some mystic appeal to the mind, the physical brain. Perhaps it wakens what is latent within the mind. Those who see it only as an emerald, a jewel, might go mad over its beauty. To one with deeper knowledge, it might say other things. You're naturally a composed person; it may well bring you a feeling of quietness, of firm balance. That's only a guess. Well, I'll have to drop it for the present—the day's getting along. We must keep exact hours for eating and sleeping."

Even in nothingness there was no lack of things to do.

A week? At the first that looked tiny, a mere nothing; but after a couple of days it began to loom with appalling heaviness. Once the pleasure of toying with such treasure as they had never even imagined, began to pall on them, the Greeks had nothing to do. From this they went to gambling; but with sacks of gold-dust under the door, the stakes presented no allure. They came at last to songs and storytelling. Nekht sat in at these, and traded Egyptian tales of magic and adventure for those of Greek heroes.

He learned from these gatherings, also. Cambyses, leader of the Persians, was a madman, drunk most of the time and given over to strange Persian vices; he had even murdered his own brother to gain the throne, and the Greeks said the gods had doomed him to be harried by the Furies, in consequence.

Nekht, however, devoted much of his time to the strange Sphinx emerald, whenever he could get it away from Amenartis. He liked the auto-hypnosis it induced; he divined that the effects were good. It gave him a surer grip on himself. After spending an hour gazing into those green expanses and shimmering depths, he felt a stimulation, a fresh strength and assurance, a quickened vitality—and a new peace within himself. This never ceased to amaze him.

He even tried out the effect of the stone on Peleus, getting the Greek captain to sit and look into the emerald for a half- hour. The result was entirely different. Peleus sat clutching at his sword-grip, keen eyes dilated, his breath coming rapidly, excitement bringing color into his cheeks.

"Hey!" A sudden ringing shout burst from him and he leaped to his feet. "By Ares, Egyptian! Can your damned magic lift a man out of this underground hell to the windy plains of Troy? The clash of chariots at the gallop—the ringing rattle of arrows on the war shields of heroes—oh, madness, madness—the glorious madness of battle—"

He broke off, staring and shamed by his own outburst; then tears streamed out on his face, and he went striding away.

So Nekht was satisfied that he had divined the truth. In Peleus, the mesmeric power of those green depths evoked battle- lust and a heroic ecstasy; with every person would come a different result, as imagination wakened the dominant impulses of the individual mind. He saw now why that eye, the symbol of truth, had been cut in the beryl—truth indeed! Whatever was in the man would be brought forth, however hidden.

"Blessings on you for this gift, old priest!" he murmured, awe in his heart. "A very talisman of the gods, indeed; you could have given me nothing more wonderful, nothing more deeply calculated to give me strength and resolution when they were most needed."

But what of Amenartis? He could not tell; he did not question her, but noted well that she spent long hours with the silent emerald. He could give her no hope at all. He knew with sad assurance that there was none to give. If she stuck to him, there was life ahead, with luck—a life of drudgery in a peasant's humble hut, with never any change, never any higher ambition; complete submission of self to an indefinite and vague formula of some dimly guessed good to come in future generations—why, it was absurd to expect such things of a woman brimming with young life, a woman high-placed, wealthy, proud! And yet her whole world had come to an end.

PELEUS said this very thing, as they talked after a meal.

"Where are you going, lady?" he asked bluntly. "Greatness is gone; show your face in the world, and some Persian will drag you off to his harem. Your entire social system has gone crash... Have you some refuge?"

"Yes," she said. "Hiding. Playing the part of a farmer's handmaid."

Nekht caught the bitterness in her tone.

"Oh, bah!" cried Peleus. "Get out of here, you two—come to Samos, to any Greek city where beauty is worshiped and intelligence given place! Why waste yourselves on some petty farm? Nekht, you could be a great captain if you would!"

"But I wouldn't," said Nekht, smiling. "My world's gone. Some day I'll help to build it up again, in my own fashion. Not as I would like, but as I must."

Amenartis gave him a look. "There's no reason why you couldn't go to Greece."

"Yes," he said. "My own choice. My own free will."

On the last evening but one, Nekht found her on the couch in tears that could not be checked. He sat beside her, holding her hand.

"It's not any lack of love for you, my dear," she sobbed. "It's just the life—the life of slavery, of hopelessness! Condemned to a patch of mud all my life—me! A patch of mud! I can't face it."

Nekht laughed softly. "Yes, that's one way of looking at it, true. Well, I'm not trying to persuade you; this choice must be yours alone, without interference. Once we're in the open air, there's no turning back, no changing. One decision is final, to be endured or made the best of, my heart! A patch of mud—yes. But a patch of mud with love might be better than a palace in Samos without love. What we think a bitter hard thing, may turn out otherwise—I don't say it will, but it may."

"You're hard," she said angrily. "You're stone—cruel stone."

"Yes, I think so," he agreed thoughtfully. "Stone, inflexible. Tears don't soften stone, but water does, across the long years; water blends with it, softens it, wears it gradually down to some mutual end. And love is like water, sometimes."

"Go away," she said. "I want to be alone."

He complied. He saw that she was clutching the emerald; he left her to herself, and to the curious, silent conversation of the little Sphinx.

NEXT day the Greeks made ready—polishing weapons and

armor, rubbing their bodies with oil, getting their final

selection of treasure bundled securely, shaving and preparing to

face the world once more. They had supreme confidence in Nekht's

promise of boat and safe egress; their trust in him was almost

pathetic. He had set the hour of midnight for departure, and

those last hours were hard waiting, and even harder as the end

approached.

Amenartis had shut herself up alone after their final meal, and he left her undisturbed. Of the treasure he took none, wanted none. Peasants had no business with gold-dust and gauds. He kept the sword she had given him—and he would keep the emerald, if she decided against going with him. He divined easily that the trusty lion-hearted Peleus would be glad to make her a princess in some Greek city, did she so desire.

He waited, in silence. The time dragged on; eleven o'clock came and passed. At a sound, he looked up, and saw her coming to him. She had laid aside her fine garments and wore the simple blue robe in which she had come here. He sprang up.

"Amenartis—we can leave now, any minute. Have you decided?"

She looked at him, a queer little shadowy smile twisting her lips.

"Yes. I'm cruel, Nekht. I have to be. There's no other way."

His heart sank. "Oh! I—I'm sorry, bitterly sorry—"

"You don't understand," she broke in. "I mean cruel, as you're cruel. Strong, resolved, firmly decided at last. I think the emerald helped me to it. I'll not fail you, dear Nekht. A farmer's wife—yes. But _your_ wife! That makes all the difference. The water that softens the stone, over long years. We can do this, together. We can do anything—together. And there's gladness in it, Nekht."

He took the hand she held to him, and lifted it to his lips. Then his arms went around her for a long moment, and they stood silently.

Peleus came in, looked at them, and grinned.

"Pardon the interruption," he said. "I came to inquire how long we must wait, but by the looks of things—"

"We go now," said Nekht, and he kissed the woman in his arms, and laughed.

The emerald knotted in his girdle, he led them—into the treasure chamber, out by a secret door, along an interminable passage adrip with dampness, and finally into open air at the river's edge, amid long reeds and trees. Here Nekht showed them where a boat was hidden securely.

THE stars were misty; over the river drifted a pall of smoke

from the city. The moon hung high and white. The boat was dipped,

soaked, put afloat. They climbed in, and the oars began to bite

the water. Ships were black on the river; Cambyses was here.

The Greeks rowed carefully, silently, upstream, then dipped more deeply. They were safely away, without alarm, their bundles of treasure weighting the slim craft. On and on, Peleus watching the water and shores ahead.

He put in at last, just below the dark village. Nekht stepped ashore, took the hand of Amenartis, and she joined him. There was a low chorus of farewells.

"May the gods be kind to you!" said Peleus.

"And to you, friends," said Nekht.

The boat pushed out. Peleus, looking back, saw them standing there in the moonlight, hand in hand. He raised an arm in silent salute.

One of the men grunted. "What, Cap'n? Saluting a brown native?"

"No," said Peleus. "A bit of green stone. I almost wish I were staying!"