RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

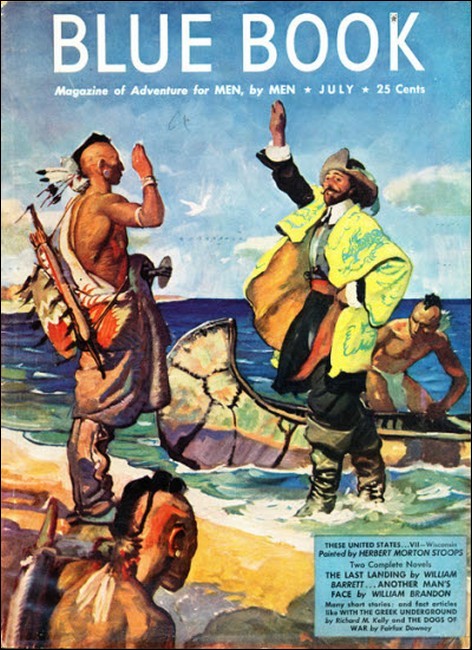

Blue Book, July 1947, with "Richelieu Raids a Tomb"

The malign magic of the Sphinx Emerald works its

spell anew in one of the famous dramas of history.

AVIGNON had been a great and flourishing city while the Popes dwelt here. Now, although they still owned it, and across the Rhone lay the foreign territory of France, the old city was full of decay and ruin and forgotten tombs and dead memories. In this January of 1618, with winter coming on late and bitter, Avignon was a most dismal place. No one lived here who must not. The only travelers were foreigners—sight-seeing French and Germans, or beef-eating Goddams. Even the few troops who garrisoned the citadel made scant pretense of policing the desolate city below.

So it was natural that gossip should center on the young man who had come here in the preceding April, renting a house close by the Minorite convent, and living like a recluse with his cook and lackey. There was no mystery about him. A bishop, as his episcopal ring testified, he lived simply and quietly, had few or no visitors and spent his whole time in the study of theology—he was forever writing sermons. A bishop exiled from Paris, said rumor, speaking truly for once.

This young Bishop of Luçon—a bishop who had never been a priest—had been exiled by King Louis XIII personally; had he not been an ecclesiastic, he would have lost his head, since the King hated him with panicked fear. Now, as he stood on the ramparts and gazed out across the wintry Rhone to the French shores beyond, his thinly handsome hard-jawed face was set in lines of melancholy. Behind him lay complete ruin, just when he had attained power as Secretary of State, thanks to his influence with the Queen-mother, Marie de Medici. Now the boy- king had clapped her into prison and seized power, sending to death or exile or the Bastille those who served her—chief among them the Bishop of Luçon, whom he hated implacably.

Standing here, looking out at the French landscape, the Bishop's manner might well be melancholy. His family held the bishopric of Luçon in its gift, and needed to make sure of its revenues, so he had been plucked from his university studies at the age of twenty-one and created bishop—things were done that way in France. And now, though still bishop, he was a man without a future, his life ruined.

"There lies France, Cadillac; and here stand we, exiled," he said sadly to the faithful lackey who followed him like a shadow.

"Monseigneur, you can mend the broken net if the chance comes," was the reply. It drew a smile from the Bishop, whose long jaw was very hard and firm.

"The broken net—well said. It is true. I can hold the lot of them netted. Yes, I can outwit the foolish, lecherous, haughty lot of them, from the King down. I can manage them, adjust their quarrels, pit one against another, and hold them in balance—control them. No one else can do this. But will the chance ever come?"

"It will come in God's good time," replied Cadillac, a sedate, devout yet surprisingly capable man.

The Bishop's thin lips curled slightly. "No doubt, but I fancy the Deity needs a nudge of the elbow. Run along, my friend, and get your marketing done. I'm for home and a warm fire."

He needed it. His health was none too good, and the wintry air provoked a frequent cough. So Cadillac went to market, and the Bishop turned back to his little house, hoping the cook would have a fire laid in his study.

It was laid, and he relaxed gratefully as it flared up and warmed him. The study was a room of fair size, with theological tomes scattered thickly all about; but the books looked singularly dusty. Sitting before the fire, the Bishop conned written sheets from his desk—a sermon, no doubt. Yet the scribbled lines looked very much like poetry, and brought a smile to his lips as he read them over.

A small table near the desk was occupied by a huge chessboard. Before it was a single chair; an accident, perhaps, though the chessmen looked unusual. Over the fireplace was a mantel in the Italian style; and on this mantel lay two handsome brass pistols and a gold-hilted rapier. The exile was obviously not pressed for funds.

NOW the Bishop went to the desk, opened a drawer and drew out

a dozen sheets of paper. These, evidently, were letters; for one

by one he read each with care, then took a quill from the holder

and signed it, sometimes adding a few words, then folded and

addressed it and sanded the address. When sealed, he laid it

aside and went on to the next, using for seal his thumb, which he

pressed into the warm soft wax after wetting it. There was a neat

little pile of letters ready, when the door opened to admit

Cadillac. The Bishop looked up at him.

"You're back—good. Kindly take these letters at once, before dark, to the Prior of the Gray Penitents, in the Rue des Teinturiers. I think his private courier for Paris leaves tomorrow. Give them to him personally, as usual. Ask if he has any letters for me."

"Yes, monseigneur." And the lackey came forward. "Your pardon, but—"

"Yes? There is something?"

Cadillac held out a folded bit of paper. "A man accosted me, asking me to give this to my master. Apparently he knew me—"

"Cadillac, Cadillac, for the love of God be careful!" broke in the Bishop anxiously. "You know we must beware of spies, that everything we say and do must—"

"I said nothing at all, master. The man disappeared. He wore plain black, not a livery, though he spoke with the tongue of Paris."

The Bishop opened the paper. It bore only a line or two of

writing:

Come tonight at nine to the house of the notary, opposite St. Joseph College. It is on business of the Sphinx emerald.

"Unsigned—perhaps a trap," mused the Bishop. "Here, Cadillac, show this to the Prior when you give him the letters. He's close to the college, and may know the house in question."

The lackey bowed, took the note and the pile of letters, and withdrew. The Bishop sat looking into the fire, his fingers playing with the mustache and chin-tuft that lent distinction to his rather ascetic features.

The Sphinx emerald—that name jogged his memory, a memory that forgot nothing. He probed, and gradually it came clear. There was a famous jewel by that name. François I had owned it; Cellini had set it for him; there had been some public scandal at the time, a hundred years or so ago—all forgotten now. The gem had disappeared.

The most fantastic stories were told about the jewel. Whoever looked into it was bewitched with a mad fascination to have it at any cost. Reputedly it was ancient, for old writers had told of it. It was said to bless some, to curse others, and to be vaguely connected with the Sphinx.

The Bishop of Luçon grunted scornfully, and frowned. He prided himself on his mentality, which was clear and coldly factual.

These fables about jewels were utterly absurd, he reflected. Certainly, precious stones made no appeal to him; he even despised the episcopal ring on his hand, seldom wearing it. Who, then, had come from Paris to summon him on so wild a pretense? A trap, doubtless; traps were ever awaiting him.

The thought made him glance at the chessboard and the pieces on it—at first glance conventional chessmen, until one looked twice and counted. Then it proved there were two queens but only one king, several bishops, half a dozen castles, as many knights, but very few pawns—very singular, indeed.

Returning his gaze to the fire, he thought of the chaos now engulfing France. With his patron Marie de Medici, the Queen- mother, securely prisoned and the weak young King in power, the great nobles fought each other with evil rapacity; crime ran riot; assassination was common. The people themselves were half in revolt; Protestant and Catholic were cutting each other's throats again, and the country was surely headed for renewed civil war. There was no control, no central authority; the King was a figurehead.

"Yet he might become the central force of all France," mused the Bishop of Luçon, "if only the right man put him there—the right man! What might I not do, were I a cardinal and the chief of state! How I would make these rascals, these degenerate nobles, these pompous fools, move into the Bastille or lose their heads—"

A sound roused him; it was the cook, announcing his supper. He followed into the dining-room, where two candles lighted his frugal board, and had scarcely settled in his chair when in came Cadillac, crafty eyes rheumed, long nose frosty.

"Good!" said the Bishop. "Here, drink some wine—sit down. A truce to ceremony—sit down and talk, I say!"

Cadillac obeyed, wiping his nose on his cuff.

"The Prior had no letters, monseigneur," he said, "but expects daily to hear from your friend Père Joseph du Tremblay. He says the house of the notary, so-called, has been taken over by some lady who is in deep mourning and is making a pilgrimage to Rome, pausing here on the way. She has two servants, a man and a woman, and spends her whole time at prayers and devotions."

The Bishop reflected. The intrigues of women prevailed in the sorry court that now ruled France. Yet here might be some emissary of Marie de Medici, trying to get in touch with him. If the Italian Queen-mother ever got out of prison, she would set off a powder-keg under the whole country. Very well, he decided; risk it! He frequently made mistakes, but he never made the same mistake twice.

"Very well," he said; "at eight-thirty be ready to accompany me—pistols charged, warm wraps. We'll beard this female devil in her den."

AT the appointed time the two men left the house, threading

the dark and tortuous old streets at a rapid pace toward the

College St. Joseph. Cadillac led the way to the house of the

notary and knocked. The door slid open; a light was thrown on the

visitors, and a servant admitted them with respectful bows.

"Madame is expecting you, monseigneur," he said, evidently recognizing the Bishop. "This way, if you please."

Hand on sword, pistols ready, the Bishop was shown into a large room where a fire blazed cheerfully. A burst of laughter greeted him.

"My faith, a walking arsenal! Good evening, M. de Richelieu. You need have no fear of me, I promise you."

TO his utter amazement, the visitor recognized Marie de Rohan, wife of the all-powerful Duc de Luynes—the most beautiful, reckless and courted woman in France. Intimate of the young queen Anne of Austria, heiress of the great house of Rohan, self-willed and witty as she was lovely—Marie de Rohan, blonde, beautiful as an angel, and decked out with mocking diamonds, girl rather than woman.

"Impossible! You here—alone, unknown, in secret—"

"To see you, my dear bishop. Lay aside that armament, and enjoy the fire. Better to burn here than hereafter—isn't that good theology? You appreciate good wine—here is some admirable Châteauneuf du Pape from the vineyards by the river yonder. You look well. I am glad. I have need of your help."

"Then the saints defend me, madame, for I shall have need of theirs! I am at your pleasure, naturally."

M. de Richelieu, as the Bishop was named, made himself outwardly comfortable. Inwardly he was in a fury of uneasiness. He knew the infernal cleverness of this young woman, who had neither restraint nor morals. He knew she had a finger in all the court intrigues. He stood in real fear of her because he feared any irresponsible and impetuous person; to his methodic brain, recklessness made no appeal.

Marie's half-secret presence here in Avignon shouted to him that she was risking her great position and herself; therefore, he told himself, it was not secret at all to those who mattered—her husband, her lovers, perhaps the King. He sipped his wine, chatted lightly, fenced verbally with her, and sniffed danger close at hand. Presently he mentioned the Sphinx emerald, and her lovely eyes lit up.

"Oh! That is why I came! Do you know of the stone?"

"Vaguely."

"Take this." She thrust a folded parchment at him. "Sketches made by Leonardo da Vinci. I took them from the King's cabinet. Study them at leisure. That emerald is here in Avignon. You must help me get it."

"I am an exile, without influence, quite helpless—" he began.

Abruptly he found her on her knees before him, clutching his arms, face close to his, pleading and beseeching his aid. She was mad about the jewel—also, she had made a bet with the King that she could obtain it. No one knew she was here; she was supposed to be spending some weeks at Aix, seeking a cure at the famed waters for a chest complaint. A plausible story, he thought, but not very likely.

And yet, for all his freely admitted intellect, the fires of life ran warm in the young veins of the Bishop of Luçon. Here was the most beautiful and hotheaded woman in France on her knees to him, and closely in contact with him, presenting ravishing glimpses of a magnificent bosom—Marie de Rohan knew the full value of personal display. She, whose favors the entire court from the King to old Bellegarde sought most desperately, now sought his! A pleasant sensation, particularly as she was unreserved and quite ardent about it.

So, ere long, they were talking intimately together. The Bishop gathered that she stood ready to reveal many court secrets, and could exert the most powerful influence in his behalf; this was very pleasant hearing. Cadillac, meantime, was being entertained by Marie's faithful lackey, one Giles. Presently she summoned this fellow Giles and presented him to the Bishop.

"You must be ready at all times, Giles, to obey Monseigneur as you would me. Hold yourself at his service in any way he may desire," said she.

Giles, on bended knee, kissed the episcopal ring and swore fealty. The Bishop accepted his devotion and dismissed him, to himself thinking he would sooner have the devil for a servitor; to judge from his face, Giles was ripe for any crime.

"YOU may trust that man absolutely," said Marie, when they

were alone again. "He is loyal. He knows about my quest, and

lately has discovered the whole situation at the church."

"What church?" Richelieu asked.

"The old and ruinous church of St. Martial, now in charge of a rascally caretaker. Plutarch's Laura is buried there."

"You mean Petrarch's Laura?"

"It is all the same. Some woman he wrote verses about."

"Yes, I presume it's all the same," agreed the Bishop. "She's buried in half the churches of Avignon, by report. What has all this to do with the Sphinx emerald?"

"Why, the tomb of the Comte de Vergy is in that same church!" said Marie, wide-eyed, innocent as an angel, a slight and delicious color in her cheeks—induced perhaps by the fire, perhaps by contact of her hand with that of her guest. "The emerald was buried with him—you comprehend?"

"Not in the slightest," he replied curtly and rather coldly. "You must explain—"

From the street outside came a loud burst of furious voices—a mere drunken row, but it flung Marie into trembling fright, or an excellent imitation of it.

"I am afraid—spies may be watching me!" she exclaimed, shrinking against him. "I am in terror all the time—this house echoes strange sounds—it was folly to bring you here. You must go, go now! Tomorrow night I'll confide everything to you—I can't think or talk, with fear in my heart. Where shall I find you?"

Later, Richelieu realized that she had handled the situation quite capably, getting him away at a provocative moment, and forestalling his refusal to help her. He admired her address, thoroughly comprehended her wiles, and found them amusing. A clever young woman, well worth seeing more of—but one, he told himself, with whom every precaution was highly necessary.

So, upon reaching home, he brought Cadillac into his study.

"I am about to ask a disagreeable but vitally important service of you, Cadillac."

Cadillac bowed profoundly. "Monseigneur, it will be an honor to die for you."

"I prefer that you live. That rascal Giles looks like an arrant rogue, but stupid."

"Somewhat so. He worships his mistress, has helped to kill more than one man for her sake—he boasted of it. He did his best to pump me of information about you."

Richelieu smiled grimly, and from his desk produced a heavy purse.

"Here is gold. Spare no money in getting friendly with this Giles. Keep him drunk. Be open-handed. And specifically—" He spoke rapidly for a moment, and Cadillac nodded.

"I understand, master. I think it can be done. His mistress is not free with money."

"If anyone can do it, you can. I know your ability. That is all."

Left alone, the Bishop of Luçon sat motionless for a time, concentrating, calmly analyzing the words and actions of Marie de Rohan. The analysis was thorough, merciless and exhaustive; he was good at this sort of thing. It helped him to reach conclusions which were usually correct; in this instance they would have been very startling to the lady concerned.

Then, sighing, he took up the parchment she had given him and looked at the sketches by Leonardo—bold, assured sketches from a master hand. He looked at them more closely, moved the candles over, sat down and began to study them attentively.

"Remarkable!" he murmured in astonishment. "Can such a thing be possible?"

The sketches showed the emerald in its natural shape and size—noted as eight and a fraction carats, lumpy and very poorly cut—and also in a remarkable and most exquisitely drawn enlargement. It was this that drew the eye of Richelieu, showing what could scarcely be seen at all in the smaller sketches. This was something within the gem itself, some cluster of shadows, perhaps flaws, that took the exact shape of the Sphinx, seen in profile. As if to accentuate the marvel of it, there was a little sketch of this imitation or facsimile Sphinx, all by itself.

The large view exerted a singular fascination. The eye came back to it again and again in search of something half-glimpsed yet not really there at all—like a dim star that reveals itself only when the eye looks away from it. This was extremely puzzling. At last Richelieu began to comprehend the genius of the master artist. Leonardo must have drawn precisely what he saw in the emerald, and giving what he only half saw or imagined, as well—conveying a mood, as it were, a sense of something felt rather than seen.

The Bishop of Luçon blew a kiss in the air, perhaps to Leonardo, laid aside the sketches, and went to bed.

IT was on the following day that Cadillac began a series of

escapades shocking to all those who knew the austere and devout

lackey. He was seen in taverns instead of churches; he was

observed on the street in a tipsy condition; and once he was

known to have emerged from the House of the Nymphs, of which the

less said, the better.

The good Bishop, however, seemed oblivious of this misconduct. And it was upon the following evening that he himself had visitors—a cloaked gallant and a lackey with a lantern. The latter was Giles. The gallant was Marie de Rohan, who had a liking for man's attire and could swagger like any cavalier, thanks to specially made girdles which lessened the risk of discovery.

The Bishop of Luçon was helpless when she took him in her arms and embraced him like an old friend and comrade. She made a merry, laughing fellow full of oaths, but radiant with such charm and magnetism and easy familiarity that all barriers went down before her, especially those of a young and highly impressionable bishop. She perched on the corner of the desk, swung a shapely leg, and laughed gayly.

"Now we're safe and I can talk freely! You have studied the sketches? They are said to be exact. Now, my honest Giles has made friends with the caretaker at the church, a pliant rogue who'll close his eyes for a pistole, and go stone-blind for a doubloon. We can have the sacristy key at will. The tomb is located and easy of access—"

"Good God, madame!" ejaculated the Bishop. "Would you rob a tomb?"

"No; the stone lid is too heavy for me. You must do it," she said gayly. "Now, I've verified the story, though it's vague in places. King François gave the emerald to some medico from Provence who cured him of an ailment—a Dr. Nôtredame or some such name. On the way back to Provence, this physician was followed and waylaid by a Comte de Vergy. Precisely what happened I don't know, except that Vergy died and was buried here. The emerald, for some reason not clear, was buried with him. And that's the tomb from which I mean to get it, by your aid."

"Sacrilege!" muttered the Bishop, shocked.

His impulsive words were abruptly checked. His visitor launched into a discussion of court politics that made him prick up his ears and listen hard. The King had said this; Prince de Condé had said thus; Épernon and Luynes were at swords' points—and so on. Much of this information was vital; all of it was new. The young King was distracted and futile. Any man who could control the factions, restore the royal authority, and prevent the coming civil war, would save France.

"And you, M. de Richelieu, could do it," said she.

Richelieu, with no further mention of sacrilege, nodded. "Yes, I could do it—provided I got the chance."

Taking his well-kept, graceful hand, she looked at his episcopal ring.

"If you exchanged that ring for a cardinal's hat, if the King himself recalled you from exile to a seat in his council—"

Richelieu eyed her sharply. Her words were not fantastic. Bishops and cardinals were appointed by the King in those days—a matter of intrigue, not of theology.

His hand closed upon hers, gently. "Well, madame?"

Her eyes warmed upon him, twinkling softly as she returned the pressure of his fingers.

"I might arrange your recall by the King—if I thought you actually could control the nobles and factions, if I were convinced of your ability—"

"Let me convince you," he said eagerly, as though yielding to impulse and confiding absolutely in her discretion. He kissed her fingers, rose, and went to the chessboard.

"Ah!" said she. "I've been wondering about those queer chessmen!"

She came and stood beside him, an arm about his shoulders, face close to his, as he reached out to the pieces on the board and spoke softly to her.

"For months, hour by hour, day after day, I've sat here studying these players." He touched one after another. "Here's the King—the young Queen—the Queen-mother. Here's Montmorenci, Vendôme, Condé, Épernon. Here's Soissons, your father Rohan, your husband Luynes—the Archbishop of Toulouse—the Bastille, the royal prison at Amboise, and so on. I know all these people. I form combinations of them to meet every contingency. My puppets play on this board, as upon France itself."

As the Bishop paused, comprehension flashed in Marie's face. She saw instantly how this man had schooled himself, had prepared himself for the future. He went on quickly.

"I play with these puppets, knowing what will tempt them to blunder, mindful of their characters, their ambitions, their weaknesses. And," he added, smiling thinly, "you would be astonished to see how fatal many of their weaknesses can be!"

She laughed; her bright blue eyes glittered. She broke out swiftly:

"I see, I see! Let me pose you a game. Look! Suppose the Duc d'Épernon were to release Marie de Medici from prison—suppose his army and half the forces of the kingdom were to back her, with Condé and Soissons—then what, eh? Show me!"

A startled look shot into Richelieu's face, his outstretched hand paused for an instant; her words sent a shaft of fierce and incredulous joy plunging through him.

"Very well—here, we group them like this!" He rearranged the pieces on the board with deft fingers. "Thus! Opposed to them the King and the Duc de Luynes, the court—"

"That means civil war!" she said, and caught her breath.

Richelieu smiled and moved out one of the few pawns. "No, no—look! Here comes a man who can oppose their hatreds and swords with his intellect—and beat them! The Queen-mother retires to her own estates in security; Épernon, her chief support, is bought off; Condé and Soissons are duped into a quarrel; we scatter gold, honors, titles, we make compromises—and see! The King alone remains in supreme authority."

"And the pawn, the unknown strong man, beside him!" Her quick wits leaped at the essential thing. She clapped her hands delightedly. "Who is he, this pawn?"

"That," said the Bishop of Luçon softly, "depends on whether the King recalls him from exile."

"And gives him a cardinal's hat." Her fingers caressed his cheek. "You know that I, like my husband, serve the King. Turn around. Look at me."

He obeyed. She was gripped by excitement. Her eyes were like stars; her breath came in rapid pulses that threw her bosom into tumult. She spoke jerkily.

"The King is a boy, weak, betrayed by everyone, frightened, not knowing whether to kill or to trust. Luynes is the strongest man at court. Good! I promise two things: First, that Louis himself will recall you. Second, that Luynes will propose and back you for the cardinal's hat. And this to seal the promise!"

She kissed him, lips to lips. He remained cynically unmoved. She had given him a vision of power so great, so sure, that it dwarfed all else.

"Judas got thirty pieces of silver for a kiss," he said. "What do you expect?"

The biting words frightened her. His piercing eye frightened her. She shivered, suddenly sensing the cold ambition of this man, the absolute hardness of him; perhaps she perceived that his ruling force was not intellect, but a will-power cruel and utterly inflexible and stupendous in its strength. Then she recovered.

"THE Sphinx emerald," she said. "You must help; you must get

it. I'll obtain the sacristy key, but I cannot move the stone;

you must do that."

Richelieu nodded. He saw the whole trap now; it opened before him like the mouth of hell. But he merely nodded reflectively. He must have time; Cadillac must have time.

"Why not?" he said. "What waste, to bury such jewels in a tomb! It's a bargain, madame. Let us say a week from tonight—Thursday next. That gives time for a courier to reach Paris and bring back confirmation of your promises, if you send tomorrow."

Triumph lightened in her eye and he saw it, but it vanished at once.

"You don't trust me?" she murmured reproachfully. "You don't believe me?"

"I believe no one; I trust no one," replied the Bishop of Luçon. Then, abruptly, he came to life and warmth. The almost diabolic charm which he could so powerfully exert leaped into full play. He became another creature—impulsive, fascinating, intimate. His eyes softened, his voice was sheer music, his hands went out to her. "But, angelic being that you are, who could resist you? I adore you with all my heart! If you want my help, you shall have it—no matter what the cost!"

She laughed softly, deliciously. It was true—no one could resist her.

The crackling fire had died down to merest embers, the wax tapers were guttering in their bobêches, when she summoned Giles, who had been entertained meanwhile by Cadillac, and departed. It was arranged that on the next Thursday evening, provided that her promises received some backing from Paris, the emerald would be attempted.

The Bishop of Luçon put a fresh candle in one of the holders, sat down to the chessboard, and sipping a flagon of wine, stared at the pieces on the board.

"Either she has heard some whisper of a plot, or had the genius to invent it," he reflected. "If Épernon were to free Marie de Medici and back her against the King with an army—ah! How that one amazing stroke would simplify everything! It seems too good to be true. And afterward—let them look to it! All I want, all I need, is to be recalled from exile by the King himself. The rest is in my own head."

For a time he played with the pieces before him, then summoned Cadillac, who, though it was now late, came immediately.

"Well?" his master asked. "How goes it?"

"Excellently, monseigneur. But I have become a great sinner, I fear. He is wavering. He has been drunk for a week. He is almost ripe."

THE days flitted by with chill winds and traces of snow, until

the mistral's unhappy breath blew them away. Twice, in the

street, Richelieu had glimpses of Marie de Rohan in her costume

of deep mourning. They had no opportunity of private speech, but

on Sunday he received an unsigned note. It said: "I shall

bring full confirmation on Thursday evening. Trust me and be

ready."

Reading this, he laughed softly. As though he would trust her! The Prior of the Gray Penitents had his own couriers, and if there were anything in this strange hint about Épernon, it would come long before Thursday. Père Joseph du Tremblay, at Paris, was a true friend and a subtle worker who could discover anything.

Richelieu did not have long to wait. On Monday evening Cadillac came into the study and laid three crumpled letters on the desk.

"There, monseigneur," he said with finality. "The task is ended. He was supposed to have destroyed them. Instead, he sold them to me. And if he gets that pardon for robbing the grave, he will be a very happy man."

"He shall have it." Richelieu dismissed the lackey with another purse, and looked at the letters. All were addressed to the Duchesse de Luynes; one was from her husband, one from the young Queen, Anne of Austria, and the third from Père Arnoux, confessor to King Louis. Richelieu read the letters, then lifted his eyes to heaven as in thanks.

"Luynes hates me because he distrusts me; the Queen hates me because she dislikes me; the King hates me because he is afraid of me!" he murmured. "Ah, female Judas, false as you are beautiful—so I am to be destroyed, eh? And had you not let slip that bit of information about Épernon's plans, you might have succeeded. If that proves to be true—then, pardieu! France is in my hand!"

IN the ensuing days it was observed that the poor young Bishop

of Luçon had somewhat recovered from his melancholy. He

was even seen to smile, at times. On the Thursday morning he had

good reason to smile. From the Prior of the Gray Penitents came a

letter just received from Père Joseph in Paris. When Richelieu

had decoded it, one paragraph struck out at him with almost

stunning force:

The Épernon intrigue about which you ask has been afoot for some time and may come to fruition in a month or so, I find. Your insight amazes me. I should never have believed such a thing possible, but it seems to be true.

When he read this, the exile could have shouted for joy.

That evening came Marie de Rohan, again in her cavalier's attire. She was gay, buoyant, excited, and triumphantly handed Richelieu a letter—a hasty scrawl from her husband, the Duc de Luynes, chief power at court:

Very well, madame, my utmost efforts shall back your promise; your bishop shall have the red hat—I swear it! As to the King, I cannot say. If you want him to write a letter, naturally he cannot refuse. He asks impatiently about your return.

"You see?" she exclaimed, radiant and aglow. "It is as I said. He will himself recall you. Now destroy that letter quickly; it is too dangerous to be kept."

"True. We must take no risks." Richelieu, sitting at his desk, crumpled the letter into a ball and turned toward the fireplace. The top drawer of his desk stood open. For an instant his hand fell to it, dropping the letter from Luynes and catching up another crumpled ball of paper—so swift was the exchange that the substitution could not be suspected. The paper blazed up. Richelieu rose.

"Well, you wish me to keep my pledge—when?"

"Now, instantly!" she exclaimed. "I have a dark-lantern and the key to the sacristy. You and your lackey must do the work, while I hold the light and Giles keeps watch. The stone is heavy, we cannot budge it; you'll need all your strength."

The two servants were summoned. Cadillac carried a short iron bar. The four set out in company. A keen gusty wind was blowing off the Rhone, sweeping down from the Alps. The streets were dark and empty.

Reaching the desolate old shrine of St. Martial, Marie led the way around to the sacristy entrance and unhooded her lantern. The huge rusty key fitted; the door opened and they stole inside. Giles furtively swigged at a bottle and remained on guard. The other three went on into the church, with the dim beam of light showing the way; the place was cold as death itself—a still cold that ate into the bones.

Now, despite herself, Marie de Rohan was fearful, hesitant, uncertain. She pointed out a tomb built against the wall; it was not ornate—merely a marble angel showed perched on the lid. With a word to Cadillac, the Bishop attacked the lid and it moved. The cement was old and poor and broken.

"The light—closer!" he ordered.

Marie obeyed—and unexpectedly, nearly went to pieces. She was overcome by the thing they were doing. The sacrilege of it, the profane desecration of it, left her shattered, wakening all the ingrained religious fears of her nature.

RESOLUTE, coldly efficient, the Bishop helped Cadillac pry

aside the heavy lid, slipped an arm in the tomb, and groped. The

dim light showed him a chain and pendant; he removed it and slid

it into a pocket.

"Now, Cadillac—close it up again. All through, madame. Lead the way."

Her teeth were chattering as she started toward the sacristy. At this instant came a scuffle of feet on the stones, a broader beam of light, a cry of warning, far too late, from Giles. Two cassocked figures, students from St. Joseph College nearby, strode into the chancel and paused at sight of the party, holding a lantern high.

Discovery! Marie faltered, came to a stop. Richelieu strode past her and went up to the intruders, facing them with calm air. He could be very arrogant, and now was.

"What means this intrusion, gentlemen?" he said coldly. "Who are you?"

"There was a light in the church," said one. "We came to investigate—"

"Then you may return," said Richelieu, holding up his hand to show his ring. "I am the Bishop of Luçon. Depart instantly, if you please."

Stammering excuses, they obeyed. The others followed outside. There, Marie took Richelieu's arm for support, gasping and trembling.

"The emerald!" she exclaimed. "Give it to me!"

"Calm yourself," said he in a troubled voice. "This discovery was unfortunate. It disturbs me. Come to my house tomorrow night, and we'll discuss things. I must have the chain and stone cleaned. It is blackened and smells of death—"

She shivered at this, and said no more. Richelieu and the two lackeys escorted her home and left her at the door; she was almost fainting when he bowed and left her.

Back in his own study, Richelieu had Cadillac build up the fire, spoke with calm authority to the unhappy man, who was overcome by the thought of sacrilege, and sent him away comforted. Then, moving the candles close, he took up a large reading-glass and began to study the emerald, on the blackened but magnificent chain made for it by the master Cellini. Since Leonardo had sketched it, he could see, the stone had been re- cut, and the work poorly done.

Nothing, however, could spoil the magic spell caught and held within the heart of the emerald. The sketches had warned him what to expect, but only faintly. Not even the genius of Leonardo could capture the illusive thing opening to Richelieu's eye as the lens brought it into focus. There was the Sphinx, yes; he could see it was formed by great flaws clustered within the beryl crystal. But more than this, beyond it....

His gaze became an intent, breathtaking study as fascination gripped him. Before his eye the interior of the emerald was spread out and enlarged into a landscape, as it were, a glittering, fantastic landscape of queer formations and shapes, caused by the odd bubbles characteristic of the gem—not round but angular bubbles. The field changed with every play of light. It seemed alive. It seemed instinct with motion. He could have sworn he saw moving shapes there; assuredly he could sense a mental reaction, a vibrant appeal, an upsurge of energy and puissance, a steely, dynamic ability rising within him. Fantasy he might reject with contempt; this was something more.

The Bishop of Luçon pushed away the emerald and set himself to analyze and comprehend this amazing thing, affecting him as strong drink did other men. He was well versed in the fundamentals of psychology. He perceived that this stone affected the beholder with a sort of auto-hypnosis. There was no magic about it. His own innate qualities were simply inflamed and carried to extremes; as he could solve some of his problems by gazing into the fire, just so did this green glory waken his imagination.

"So that explains it!" he murmured. He wanted to gaze into the stone anew, to satiate himself with it, to drink in these visions again; he refused. The temptation was almost unbearable; therefore he resisted with all the power of his iron will, dropped chain and emerald into a drawer, and snuffed out the candles. Another time, yes—but he was resolute in not letting the thing master him. This was characteristic of the Bishop of Luçon. Within his purview there could be only one master—himself...

NOT until the next afternoon did he permit himself to take

another look into the stone. Cleaned and polished with its chain,

he slipped it about his neck and for a space gave himself up to

its wizardry—not blindly and fatuously, but critically, as

one tastes a rare liquor. And when he finished, he knew within

himself that he would never give up this marvelous thing while he

lived.

Marie de Rohan arrived for dinner that evening, as bidden, and found her host the most charming of men. He agreed with her in everything; he flattered her extravagantly, he confided to her his most secret thoughts—apparently. And she, well assured that her entire game was won and in the bag, showed herself merry, affectionate and most adorable. When she mentioned the deplorable intrusion of the two seminarians, he waved his hand and dismissed it as a mere nothing—greatly to her wicked but secret delight.

Now and again she surprised an oddly sardonic gleam in the Bishop's eye. This might have disturbed her, had she not been so fully sure of her power over him. She asked about the emerald. Later, said he, with a graceful gesture toward the study, and she nodded. The meal was delicious. Cadillac served it with superb aplomb. The wines were something to astonish even a Rohan.

When they came into the study, where a cheerful fire was burning, she saw that an easy-chair had been provided; Richelieu held it for her, then seated himself at the desk facing her. The desk was littered with documents and papers. To her surprise, Richelieu regarded her without a smile; and when he spoke, his voice held a harsh crackle.

"Madame, we must discuss a certain matter very bluntly, even impolitely."

"Mercy!" A bubbling laugh broke from her. "One would imagine that we were in a formal court of law! What is this certain matter?"

"The reason for your presence here in Avignon," he said coldly.

Marie's merriment vanished. Although incredulous of his attitude, she took warning.

"You astonish me, monsieur! Such a tone, between dear friends—"

"Between enemies, madame. The most bitter and implacable of enemies."

Her pride flicked on the raw, she regarded him with angry flashing eyes.

"Will you have the kindness to explain yourself, M. de Richelieu?"

There was no warmth or kindliness in his manner. For the first, and not the last time in their lives, he wore the air of a prosecutor, cold and precise.

"Certainly." He picked up a paper. "I have here a number of letters whose tenor is much the same; this one is from Her Majesty the Queen. It tells me that you are here with her knowledge and that of others, to carry out a certain design formed by them—namely, to make sure that the unhappy Bishop of Luçon shall be disgraced, deprived of his ecclesiastical honors, and prosecuted for his crimes, both by the Church and by the civil law. In short, to ruin and imprison him for life."

As she listened, the face of Marie altered. It lost its beauty. It became a mask in which glittered twin pools of blue fury. Richelieu touched others of the papers before him.

"These letters from your husband, from the King's confessor, bear out the first, madame. Lies, evasions, trickery—all are useless."

She burst into a low, vehement command. "Let me see those letters!"

"No. They are reserved for other eyes, madame."

"I understand! That vile wretch, that accursed Giles—he shall suffer for this!"

"On the contrary, I have assured him of full protection. However, you are not here to receive accusations, but orders."

She was convulsed by sudden fury, half rising from her chair, her hand sliding a dagger into view, her contorted features terrible to see. The door opened, and Cadillac appeared, his entry checking her action.

Richelieu spoke without emotion.

"Cadillac, you will be so good as to stand behind the chair of Madame and see that she does not leave it."

Cadillac obeyed. She sank back in her chair, composed herself, and spoke almost calmly.

"Very well. Play out this absurd little comedy, monsieur."

Richelieu inclined his head slightly, and produced another paper.

"I see by this letter from your husband, which did not get burned the other day as you thought, that certain promises are made. When, in compliance with these promises, I am recalled to Paris by His Majesty, I shall be very happy to return these missives to you, madame."

"That day will never come," she said with suppressed fury.

"A great pity. These epistles are somewhat indiscreet. The King, no doubt, would be displeased to learn how his actions are controlled."

She drew herself together, realizing her error in showing fury toward this dupe who had so unexpectedly become an enemy. A gleam of assured triumph in her eye, she spoke quietly, with perfect self-possession.

"We will risk all that, my dear M. de Richelieu. I gather that you wish me to manage your recall?"

"Precisely as we agreed, yes," he said, watching impassively, fully aware of her thoughts. "I, in turn, will risk the fulfillment of the promise made by M. de Luynes regarding the red hat—I believe these things will work out excellently."

"And the emerald?" she asked.

Richelieu made a gesture of regret. "Ah, that must wait upon the future, my dear lady. I trust that you will comprehend the importance of making sure about these letters, first of all."

She smiled, but her eyes were deadly.

"Have you finished, monsieur?"

"I think so, unless you find me in error."

"Very much in error." She leaned forward, and with an obvious effort held herself in restraint, launching her bolt in a voice that trembled with rage. "It is obvious that a scoundrel guilty of the vilest crimes would not hesitate to forge such letters. You cannot blackmail me, M. de Richelieu. Within three days the ecclesiastical authorities will arrest you, and you will be handed over to the courts of the King of France as a criminal. The papers are already being drawn up. It is you, monsieur, whom evasions, lies, trickery, cannot avail!" she added with a burst of triumph. "Sacrilege is a hideous sin in the eyes of the Church. A bishop guilty of sacrilege presents a scandal to the whole world. An ordinary man who desecrates a tomb is broken on the wheel—how much worse is this crime when committed by a gentleman! All France will cry out in horror!"

The Bishop of Luçon sat, chin sunken on his chest, eyes gripped to the papers before him. With keen relish, she went on:

"You have committed this crime. There is evidence in plenty to convict you. This lackey of yours must confess to the truth, under torture. The two seminarians who intruded upon the scene, and whom you dismissed with such arrogant declaration of your identity, are damning witnesses to the truth."

Richelieu sighed. "I fear, madame, that you are correct," he said in a dull voice. "I cannot evade the accusation. So you arranged for that intrusion? Cleverly done, very cleverly. It is terrible to think I am so hated by the King, by the Queen, by M. de Luynes!"

"No man in France is more hated," she said pitilessly. "You have brought your destruction on yourself. If you try to use those letters, they will be pronounced forgeries. That such a scoundrel would be guilty of forgery, is quite evident."

Richelieu lifted his head, looking at her with apparently anguished gaze.

"What do you want? What can I do to escape—"

"Nothing!" she cried vibrantly. "The accusation will be laid before the authorities in the morning. Everything is prepared, witnesses ready, statements sworn."

A faint, thin smile touched his lips.

"None the less, madame," he said quietly, "you will go to Paris, you will keep your promises to me, you will see that the King himself recalls me."

"Have you gone out of your mind?" She uttered a contemptuous laugh. "The accusation made against you in Paris—"

Richelieu lifted a document, to which were attached several imposing seals.

"There will be no accusation, madame, either here or in Paris," he said. "This document is signed by the Archbishop and other authorities here. It authorizes me, for certain purposes deemed for the best interests of both church and state, to open the tomb of one Comte de Vergy, situated in the church of St. Martial, and to remove therefrom such object or objects as I desire. I spare you the legal and ecclesiastical phrasing, which is somewhat tiresome." He set down the document, put his finger- tips together, and regarded her sharply. "It might be a mistake, madame, to make any accusations which would tend to involve you yourself in the crime of sacrilege, unless you have a similar permission from the proper authorities."

Listening to his words, the young woman went into a blaze of fury—then the blood ebbed from her cheeks, leaving her white as death. Eyes staring, lips trembling, she dropped back into her chair, beating upon the arms of it with hysterical hands.

"Oh, you devil—you devil!" she cried in a choked voice.

Richelieu inclined his head slightly. "No, madame—merely the Bishop of Luçon, at your service," he said with freezing courtesy. "You have my word of honor that these regretfully compromising letters shall be returned to you as soon as I am in Paris. And you will assure His Majesty that my sole object as Cardinal shall be to render him supreme in France. Now, Cadillac, since Giles is no longer in the service of Madame, you will have the kindness to see her safely to her home."

LATER, when the footsteps and the sound of choking sobs died

away, the Bishop of Luçon sat for a long while, reading-

glass in hand, intently gazing into the heart of the Sphinx

emerald. And what he beheld there seemed to cause him the

greatest satisfaction. Presently he laid the reading-glass aside.

His long, graceful fingers touched the gem almost

caressingly.

"I shall never part with you," he murmured. "Decidedly, we must ever remain friends and allies! I shall have need of your helpful magic in the days ahead!"

And under his touch the emerald warmed and glowed softly, happily, as though in reassurance that everything he most desired was coming true.

But Marie de Rohan, Duchesse de Chevreuse in the future years, was to be the most deadly and implacable of all the great Cardinal's enemies.