RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

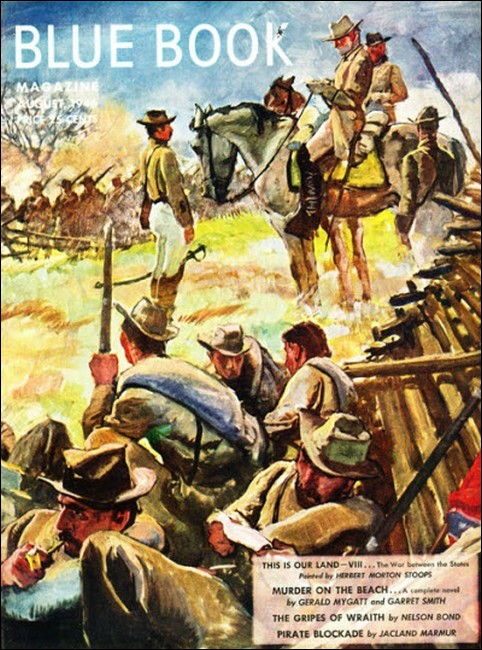

Blue Book, August 1946, with "The Last Pharaoh"

That strange bewitching jewel, the Sphinx Emerald, plays another part in world drama when a Mata Hari betrays the Egyptians, and Artaxerxes of Persia storms up the Nile to take over the ancient kingdom of the Pharaohs.

I HAVE been called a commercial-minded Greek, a sour, money-mad curmudgeon and other such names, and probably with some truth. However, it is safe to say that I am the only person who really understands what lay behind those events in Egypt. I was part of the show myself, and my firm had a finger in the events.

Full thirty years previously, my father had emigrated from Greece, when King Agesilaus of Sparta sailed from Greece to join Nekht Horu-heb, Pharaoh of Egypt, and inflicted a crushing defeat on the Persians. Our contracting firm was founded then, and I carried it on in my own day as the biggest concern of its kind in the world. Our headquarters were in Memphis, of course. This was in the time of Nekht-nebf, whom we Greeks called Nektanebos, the greatest king Egypt had known for generations. The Hebrews gave him that silly title of Pharaoh, deriving it from the Egyptian title Per'aa or Great House, one of the many oddments that dangled on royalty's mantle.

We were doing very nicely in those days. Nektanebos was a great soldier and builder and civilizer. There was always war with Persia, which looked upon Egypt as a revolted province; but in fact our king belonged to an actual native dynasty tracing its blood back to the great Ramses. Our firm, Archias & Co., prospered heavily because Greeks were everywhere. The armies were largely Greek mercenaries. Greeks had settled heavily in Egypt and Persia and Asia Minor; they vied with the Hebrews in business and commerce—indeed, my chief competitor was a fellow named Saul, who headed a Hebrew contracting firm.

Nekht had been king for about eighteen years when that odd business of the Sphinx emerald came to my attention. I was getting on in years, being in my fifties; my wife was dead, and my boy Archias was in Tyre, handling the foreign angles of the business, while I ran the head office in Memphis.

Being on fairly intimate terms with the King helped the bank- account but kept me on the jump. He had made me one of the council, too, which was onerous work at times. He was forty-five or so—easy-going, rather credulous and superstitious, but a fine sort of man just the same. He had one son, who was in charge of the army at Pelusium, on the Syrian frontier. The crack troops were there because of the Persian danger. The prince was not up to much, however, and I said so frankly to Nekht.

"That boy of yours needs a bit of stiffening," I said one evening at the palace. "He's giving his time to women and hard drinking. Give him a job at that new quarry you've opened at Tura—hard work there!"

"I may, when this present crisis is over," he said, stroking his oval, deeply lined features. "At the moment, he's needed where he is, as a figurehead. The army—"

"Oh, I know!" I broke in. "You should be there in place of him. You're a real soldier. You licked the Persians before; you can do it again. I've had letters from my son in Tyre. He thinks the Persians are secretly on the move—the betting is that Ochus will be King of Egypt inside of six months."

He grunted. "That fellow's no soldier—an old man, worn out, faded! The stars say he hasn't two years to live, Archias."

"Are you still steeping yourself in astrology?" I snorted. "That's absurd."

A chamberlain came in, muttering hurried words. The King nodded.

"Bring her in, now," he ordered, then turned to me. "My friend, I'd like your opinion of this woman, and her errand. The stars predicted her coming, you know—"

"Pardon me," I broke in. "The stars don't predict anything. If I were in cahoots with one of your astrologers, I'd make predictions too, and bring 'em about."

"You're a hard-headed old skeptic," he shot out. "Don't you believe in anything?"

"Depends on how much I have to lose," I told him. "You have a good deal—Egypt. Can't you realize that these astrologers you support are taking you for a sucker?"

"No," he said, half-angrily. "The secrets of the stars, their influence on our lives and destinies, is an ancient science. We inherited it from Chaldea. Try now to control your cynic mind, and don't snap so readily at other men's beliefs. Here, while I'm talking with her, you can look at this—it's been handed down in the family from ancient days."

He passed me a green bauble. I took it but disregarded it.

"Wait," I said. "Tell me where she came from?"

"Out of the eastern mountains, with a message from the gods," he said, just as a woman and two guards came in. He motioned them forward.

I relaxed and looked at what he had given me. It was a lumpy emerald set in a ring or circlet of gold—a poor emerald of wretched color, badly flawed, sadly in need of cutting and shaping. This, for the moment, was all I saw in it, for I looked up at the woman as she came forward and sank in prostration before the King, with the two-armed royal salute. Then she rose and threw back her veil and handed him a small scroll.

"The god Horus gave me this scroll for you, O King," she said. "He came to me in dream, left this in token of his coming, ordered me to bring it myself to you. It is sealed with his own seal."

"Who are you?" Nekht asked her; and at the look in his face I suppressed a groan. Some people will believe anything, with superstition to prod them.

"I am named Merti," she said. "In the ancient days my fathers were priests of Horus at the shrine of the Sphinx."

"Oh!" said he. "The Great Sphinx by the Pyramids?"

"No, lord," she replied. "Its fellow, in the eastern hills, that faces westward."

He said no more, but began to read the scroll. She waited, her eyes downcast. She was a pretty thing in a way—beautiful, if you like the word. I prefer women with sense to those with outward beauty, and I glanced at the emerald in my hand. It startled me, and I held it up and looked again, doubting my own eyes.

BY Zeus! It was true—within the stone was a tiny Sphinx!

Some sort of trick, I thought, till I discerned the truth: Flaws

and bubbles in the stone had come together to make the

figure—not a mere rough shape, but exact, perfect, clearly

cut—set in the very heart of the crystal. No man could have

made this; it was supernatural, from the hands of the gods. I am

not superstitious. I do not waste good money buying birds and

bulls for sacrifice on the altars that the lazy priests may

feast. Still, for one moment I did have a sharply uneasy thrill

at sight of this Sphinx. Bad luck, I told myself, with a bit of

Greek instinct; we Greeks never worshiped sphinxes.

"An interesting communication, superbly written," said the King, turning to me. "You read Egyptian—look at it." He passed the scroll to me and looked at the woman. "I shall probably obey the commands of the god Horus, Lady Merti. Anciently, each great Sphinx had an attached temple where Horus was worshiped; we have today forgotten those shrines, which are almost completely buried under the sand. To clear them will be a great labor. To do it myself, as the god desires—well, I shall think about it."

"Horus will reward you, O King," she murmured.

He looked pleased. "Do you remain in Memphis, lady?" he asked.

"Until I receive your answer, yes," she replied. "I have one or two other errands here. I must see a Greek named Archias, and one or two other lords, before returning."

Nekht gave me a glance, but I remained silent, and he took the hint.

"Return, then, in a week," he said, "and receive my answer. You shall be lodged with the priestesses of Isis as a royal guest; see whom you will. Gifts worthy of your beauty will be brought you in the morning."

SHE withdrew. She had never so much as looked at me; yet I had

an idea she knew all about me. When we were alone again, Nekht

turned to me.

"Well, Archias, what do you think of this?"

"Are you asking as the King of Egypt?" I demanded.

He chuckled. "No, confound you! As a friend in need of advice."

"Then it has a bad smell," I said bluntly. "As for Horus and the dream, that's just so much stale cheese. Who actually sent this beauty? Where did she come from? Why are you wanted to do such a job, one that will require thousands of slaves and baskets of money, and do it yourself?"

"Come," he said, smiling. "For once give the gods their due, Archias—"

"I'll do that," I said, "but the gods don't deal with sand, and beautiful women and rummy yarns like this one. No god wrote that letter. I tell you what: Give me three days to think this over. That girl is going to see me, for some reason, and it isn't to make love back of a pillar, either. She'll probably turn up at my office tomorrow. The day after, I'll be able to give you a line on her."

He nodded. "All right. Come and have dinner here that night—day after tomorrow."

"You're shortening me one day, but I'll agree," said I, and held up the emerald. "Where did you get this—part of the ancient royal treasure, you say?"

"Yes. A fascinating thing, Archias. Take it with you and bring it back when you come to dinner. Meantime, sit and look into it, and tell me what the stone says to you."

"Does the Sphinx speak, then?" I asked ironically. "Very well. And I advise you to send a good excavator to look at those Sphinxes and get an estimate on the cost of cleaning them up, before you give her a reply."

This amused him, and he was still laughing when I departed.

On my way out, I stopped for a word with Tii. He was a minor palace official who had a genius for undercover things; I had used him frequently, and knew him to be devoted to Nekht. I spoke frankly with him about Lady Merti.

"You have her shadowed," I said. "What's more, find out if you can, where she's from and who she is. She didn't just walk into town from the eastern hills, that's sure. If there's a plot against the King, I want to know it, and know it fast. Spare no expense."

Tii was an energetic fellow, and promised to get on the job at once.

I WENT home, lighted a couple of oil lamps and sat gazing at

the emerald. What with reports from our agents all over Syria and

beyond, I could guess at a few things myself, and why somebody

wanted Nekht held right here in Memphis by a crackpot job while

the army remained away up north at Pelusium.

Ochus, as they called Artaxerxes, ruler of Persia, was up to mischief. He might be old and outworn, but he had some mighty good moments and was capable of anything. The Persian army had smashed everything in the world, because it was a magnificent long-distance weapon—practically all bowmen, splendid archers who could wipe out an opposing force before it could reach them. Nekht had hammered those Persians, however. He was a tactician, and had figured out how to oppose the archers and smash them, and had done it. They were afraid of him. If they could keep him occupied here, and then jump on our army at Pelusium, they would have a good chance—this might be a key to the riddle.

Having figured this out so easily, I forgot it and watched the emerald.

The cursed stone fascinated me. It sharpened my wits while I looked into it and studied the little Sphinx—complete to its head-dress and forepaws. Something about it really did seem to speak to me, as Nekht had said it would—but not nice things at all. To a Greek like me, Sphinxes were not friends; they were Egyptian inventions and they meant trouble. This emerald was in its way a wonderful jewel. Properly cut and polished, it might well suit a royal owner; an eye, the ancient symbol of Thoth or Horus, was cut on the bottom. Still, the more I looked at it, the less I liked it. I sat back and cursed the thing, and could swear that it winked back at me.

"There's evil in you," I said at last. "You're bad luck, and a lot of it. If you were mine, I'd get rid of you mighty quick! Still, given the proper cutting, you'd become a very handsome cabochon. Easy enough to see why the King—poor fool—thinks you are such a wonder."

Poor Nekht! Friend as he was, fine soldier, builder and kind- hearted man, I felt sorry for him. He had no practical sense at all. He had rebuilt the great old temples and got nothing in return. He really believed in the gods. Worse, he believed in the stars and kept half a dozen astrologers living in luxury by his credulity.

What the stars are, I neither know nor care; but I'm well convinced they have nothing to do with my contracting business or with my own life. Nekht swallowed all the jabber these astrologers poured into him, and credited their deductions and ciphering to boot. I have known him to put off visits of inspection because of some fancied evil influence from the stars.

So, before I rolled up for the night, I wrapped the emerald in a cloth and put it away tightly. I wanted no more of it and its bad luck. I was right about the bad luck, too: About five in the morning they wakened me to receive a courier from Tyre. The company had its own fast courier service; sometimes we even used carrier pigeons, as the Persians did, but in important matters preferred actual couriers. This man had come from the Nile mouth by fast boat, bringing me a letter from the office manager at Tyre. The news in this letter could not have been worse—for me. It read:

Your son, the noble Archias, left for Sidon three weeks ago to arrange details of supply for the fleet from Cyprus. I have just now received word from the Sidon office of his disappearance. More, I know not. I am making every effort to investigate, and shall send you further news as I receive it. May the gods bring him back safe and well!"

This was a facer, and knocked everything else out of my

head. My son was getting on to thirty, and nobody's fool. Indeed,

I was proud of his level head and was hoping to turn the company

over to him in another year or two. And now—this! He was

the only son I had, too.

TWENTY years earlier I would have started hotfoot for Tyre.

Now I could only sit here and curse the distance, and wait. The

company branch managers were good men; they would do what anyone

could. Yet to think of him lost in Sidon, that accursed city of

slave-dealers, was frightful; those rascally Sidonians thought

nothing of knocking some stranger on the head one day and putting

him up in the slave-market the next day.

I told no one the news, but grimly went through my usual morning's routine at the office. Absolutely nothing to do! That hurt. To think of business was hard. Pyrrhus, that old idiot of a money-lender from Samos, dropped in with a fantastic scheme of buying Egyptian manuscripts up and down the Nile. The Persians, he said, intended to conquer Egypt sooner or later, and had announced that they meant to destroy every bit of civilization here; therefore in the future such books would be of great value. Ordinarily I might have gone in with him on the deal, but this morning I turned him out savagely, with my worry about Archias in mind.

Instead of going home for lunch and siesta, I stayed in the office writing letters. Tii popped in without warning.

"I've found out a thing or two," he said. "First, this woman got here several days ago. She came by boat up the Nile. Yesterday she was in the bazaars and bought two pigeons from a bird-dealer named Pharses; probably carrier pigeons. Pharses is a Persian, if that means anything to you. She has the birds with her now at the temple of Isis."

"Who is she?" I demanded.

He shook his head. "Can't say, yet. Let you know later what we pick up."

He slipped off. I was still cursing him when a clerk came in to say that a Lady Merti had arrived in a litter, and would I see her. Naturally, I ordered her brought in, and ordered a scribe to sit behind the partition and take down our conversation—a useful little trick in many a business deal.

She came in and positively took my breath away—it was a hot day, and her only robes were those filmy gauze things women usually wear around the house that reveal every line and wrinkle of them. She was beautiful, as I have said, and well made too. She put on no airs, but took the chair I held for her, and smiled at me.

"Greetings, Archias," she said in excellent Greek. "This is an admirable place you have—quite imposing, in fact. These offices and storage-houses are larger than many a temple."

She was no demure and simple hill maiden now—far from it! Jeweled necklaces and rings adorned her; perfume scented her black hair; kohl rimmed her eyes; she was bending smiles and attention upon me—me, old Archias, who had tired of women before she was born!

"What's your errand with me?" I demanded curtly.

"A pleasant one, noble Archias, that will delight your heart," she said gayly. "But first—suppose that the gods overthrew Egypt and gave this land into Persian hands. How would it affect your enterprises, this vast company of yours?"

"Not at all," I replied. "Our branches in Tyre, Syria, Persia are larger than this one; we serve Persians as well as Egyptians. We have no concern with politics."

She eyed me laughingly. "Indeed? But you have a high place in Egypt. The King trusts you, depends largely upon your wisdom. Suppose I said that my errand here was to win you to the Persian cause—eh?"

"You'd have less sense than I credit you with," I grunted.

"The first day of the new moon is three weeks from now," she said slowly. "On that day, noble Archias, it is vitally necessary that King Nekht-nebf be occupied here, or at the labor on the two Great Sphinxes. You can readily persuade him to undertake that labor and superintend it himself. Will you do this for me?"

"Why for you?" I asked, mindful of the scribe taking down notes, and hoping to make her talk freely. "I could do this, yes; but why should I?"

SHE left her chair and came to me. Oh, she was a sly puss,

with her perfume and her pretty body and guileful ways!

"For more than one reason, dear Archias," she murmured. "First, because you like me a little, and secondly because I can give you all your heart's desire."

"You flatter yourself, sweetheart," I said ironically. "My heart's desire is far from here, and far from any power of yours."

She smiled, put hand to girdle, and drew forth a small sealed scroll.

"You think so? Then read this."

I took the scroll, and saw the seal of my son Archias. I broke it, opened the papyrus, saw his writing. The letter was brief and clear and terrible:

Greetings, my father. I am in Persian hands. Do as they demand, and I shall be set free. Refuse, and I shall be slain. However, do as may seem best to you, and may the gods protect you!

Yes, Archias had written it. The Greek letters had the

little twist of the pen that was the private code of the firm

indicating personally written words, with no ulterior meaning. He

had been seized in Sidon and the Persians had him! I stared at

the letter, thankful that he was at least alive. Lady Merti

pressed close to me, her fingers caressing my cheek.

"He is the one thing in this world whom you love, and for whom you live," she was saying. "He is everything to you; his future, his success and happiness, are twined about your heart. We know this. Do what I ask, then, for his sake; he will be given the favor of the Great King, Ochus; his days shall be bright, prosperity shall crown his work! This is a promise. Surely it is better than causing him to be killed and sent into hell—"

I groaned. They had me, and she knew it. King Nekht and Egypt and the whole wide world were nothing to me, as compared with that curly-haired son of mine. To save him I would betray the gods themselves—if there are any gods, which I doubt.

She caressed my cheek once more. "Agree, dear Archias," she said. "He is a handsome young man, well worth saving; I have seen a good deal of him lately. Now, look! I have the magic power of the god Horus to aid me. Agree, and at this time tomorrow he shall be set free, though he is far away! Refuse, and at this time tomorrow he dies. The choice is yours. His fate is in your hands."

Magic power? Those carrier-pigeons, of course. They had been planted here in Memphis, well in advance of her coming. The whole damnable scheme had been plotted out far ahead. It was good, excellent work.

"Very well, my dear; I agree," I said, looking up at her. "So you were the one who betrayed him into Persian hands, eh? You're working for the Persians. Well, all this does not make me love you. H'm—free him tomorrow. A courier can reach here in two weeks from Tyre, with word to that effect. If it doesn't come, I can still halt any labor on the two Sphinx-temples, a week ahead of the new moon."

"Admirable! I like you even better than your handsome son," she said. "He'll be freed tomorrow. But you must swear an oath to make every effort to keep the King at work on those temples—we could do without you, since we have other means of gaining our end, but it must be made certain."

There was an oath, and this accursed spy knew it. For thirty years the oath of an Archias has been sacred, when sworn upon his father's beard and honor; by that oath, the company has contracted with kings and generals and politicians. It holds the honor of the firm, the personal honor of the Archias who heads the firm, and from Thebes to Babylon it has become a byword for security—and this woman knew it. No Archias has ever broken that oath, nor would I break it—and she knew it.

So she dictated the oath, and to it she added the clause that I would say nothing to any living person of my dealings with her, which effectually stopped my tongue. So she was the one who had lured my son into the trap, eh? Yes, I swore the oath, but to myself I added the clause that she would not live to trap him a second time. She laughed lightly, told me to await the courier with word of my son's freedom and honor at the court of Ochus, and took her departure.

Now, you must understand that to us Greeks, murder is a crime, especially the murder of a woman. It was not always so. The Egyptians held it to be a wrong, but no crime. When the great Ramses killed his sister, this was a wrong but nothing more serious. Either the Greeks or the Hebrews, I know not which, brought in a new code of laws. Murder this woman, I could not; but justice was another matter.

When she had gone, I summoned the scribe from behind the partition and looked at his notes; they were full and complete. At their end, I added an attestation of their veracity, and placed my seal, then returned them to him.

"Guard them well," I ordered, "and be ready to produce them when ordered."

I WENT home and shut myself up to think this out, all of it.

Impelled by some inner prompting, I took out the Sphinx emerald,

set it in the light, and looked at it for a while; hatred had

gathered within me, but those green depths wiled it away. Instead

came caution, and craft, a feeling of immense and deadly

subtlety. It was as though whispers came to me from the very lips

of Odysseus, most crafty and cunning of all men.

Lady Merti had snared me, yes. I was committed beyond recall; I must advise the King to proceed with the work and free the Sphinxes of sand; I must betray him. Free or not, my son would be held by some string until this was done. Very well; but Archias, son of Archias, had not lived fifty-odd years for nothing. I had not outsmarted Jew and Tyrian and Egyptian in business, I had not built up Archias & Co. into a worldwide firm, to be caught in a net by a woman. The old fox could eat his way out of any net.

A fine bit of brag; and quite false. I was nipped. There was no way out. Yet, as I looked at the tiny Sphinx in the emerald, I told myself that there must be some way, if I could only find it or make it. From those green vistas, flash upon tiny flash seemed to leap through my mind. A word, a thought, took shape; "Wait. Keep your oath you must—but wait! When something turns up, be ready."

The emerald did not say this to me, but I think it did cause the thought to rise in my head. I wrapped the stone up and laid it aside, and sat thinking. I must betray the King, the man whom I respected and even loved, him who trusted me; the life of my son was more to me than he or his throne could be, or all the splendor of Egypt. To this course I was bound. By my action the Persians would sweep over Egypt like a plague of locusts and reduce the fat country to the status of a desert. This was hard to realize.

The upshot was that I made up my mind to it; the only thing I could do was to wait for what might turn up. Until a courier came with definite word that my son was free, I must do nothing. So I relaxed, and sent out a code letter to the company branch managers, ordering that all funds of the firm be collected and securely hidden because of anticipated political changes.

THAT night, Tii came to my house. We sat behind closed

doors.

"Lord Archias, the woman has been busy," he reported. "She visited your office this morning and was there an hour."

"Think I don't know it?" I snapped.

He grinned at me.

"She also visited the Persian bird-dealer and bought two more pigeons."

"Oh! Make a note to have that fellow watched; we may want to take him into custody suddenly."

"Right, my lord. This afternoon she visited two of the astrologers who serve the King, spending half an hour with each. She bought some woman's gear in the bazaars—henna and such things, and new sandals."

From my desk I took a string of gold rings and tossed it to him.

"So far, good, Tii. Watch the woman; she is to see the King next week, and then will leave—how, I know not. Let her leave, then stop her, catch her, cage her somewhere close to the palace. I may want to get at her in a hurry. Do it quietly, of course."

He assented. "So far I've learned nothing about her. One of the palace guards, that fellow Antenor from Samos, swears that he saw her in Sidon a year ago, and that she was a fine lady riding in a litter."

"He may be, and probably is, telling the truth," I said. "At least she came here from Sidon. Well, make sure of her when she leaves, then report."

So Lady Merti was probably leaving in a week; another two weeks would bring the new moon and some sort of crisis. And my lips were sealed. Two weeks should bring a courier in regard to my son, and this, at the moment, was all that mattered to me.

NEXT day I started a campaign to collect all funds due Archias

& Co., with a heavy discount for immediate settlement; also to

close outstanding contracts where possible. Word came in from our

upriver agents that royal orders had gone forth for a mass

movement of public slaves downstream at once; some ten thousand

were affected. This meant that Nekht had resolved to do the work

on the two Sphinxes.

He said as much that evening when I went to dine at the palace.

"The estimate is that it will require five thousand men at each Sphinx," he said, "working from thirty to ninety days, to clear them. I expect you to kick in with a food contract, my friend."

I nodded. "Gladly, my lord."

"And I'm not the idle fool you think me. I know something's stirring. I've sent my son strict orders to keep on the lookout, and officers are on the way upriver to raise a force of five thousand Nubian archers, to join him."

"Better," I said gloomily, "if you'd pack off those lazy astrologers to Pelusium or to hell. Sitting all night on their hind ends studying the stars!"

He laughed at this with hearty amusement.

"No. Great things are going to take place on the first night of the new moon," he affirmed. "Certain of the planets will then be in conjunction; there's to be a meeting of the astrologers, at which I'll be present. It's expected that the destiny of Egypt itself will be affected, and we must take advantage of the indications at once."

No use at all talking to him; he was besotted by his superstition. He asked if I were against undertaking the work on the Sphinxes.

"No; quite the contrary," I said, thus keeping my vow. "In fact, an astrologer has made the astonishing prediction that in two weeks I'll receive a vitally important message from my son, who's up in Syria somewhere. If it comes true, I'll withdraw my objections to star-gazing."

He laughed and thumped his golden wine-cup on the table.

"Ho! That'll be worth a celebration!" he cried. "See here, Archias—if it does come to pass, let me know and I'll give a banquet in your honor! To be rid of your croaking would be well worth it. What's more, I'll grant any request you may make of me—my word upon it! What do you say?"

THEN and there the idea flashed over me. I demurred, to make

him more eager, until he swore by the gods to keep his word. I

said that my son had disappeared, and foul play was feared, but

that the astrologer had declared word of his safety would come in

the fortnight. He became keenly interested and repeated his great

oath to do as he had said. So it was settled.

He mentioned the emerald, and asked if it had exerted any effect upon me.

"Yes. I don't like it," I said, and taking it from my pouch, I handed it to him. "I dislike the thing, in fact, distinctly. It brings queer thoughts into my head."

"It does that to everyone, Archias," he said soberly. "I used to gaze into it frequently, and do you know what it made me think of? An oasis in the desert—I could even see the place distinctly in all details. I've been told that it's the oasis of Sekhet-amit, the 'field of palm-trees' where Amen-Ra is worshiped; but I've never been there."

Superstition had him again; and he babbled on about this oasis of Siwa, as we Greeks knew it, but I paid him no further attention. Oracles, priests, oases and gods did not interest me, except where Archias & Co. might be concerned. Besides, I had eaten too much of the delicious duck that was served, and knew I was in for a spell of indigestion. I was, too, and it bothered me for the next three days.

I was not present when Lady Merti saw the King again, and learned he was already preparing for the work, and took her leave of him. Tii informed me about it. She was loaded down with royal gifts and was taking a small boat down the Nile, no doubt to connect with a Sidonian galley below town. She did not connect, because Tii's men bagged her neatly.

Nekht was in earnest about clearing the Sphinxes of sand, and huge batches of slaves came downriver and established camps. The Sphinx in the eastern hills was difficult of access, out of the way, practically forgotten in those wild desert regions; we had taken the food contracts and it was a job getting stores shipped there.

Every day now a palace chamberlain came to see whether any news of my son had arrived. None came; I grew worried and anxious, though the fortnight was not yet up. Everything was quiet on the frontier, and it really looked as though the Persians did not mean to make trouble after all. I even began to think I had made a mistake in having Lady Merti put into a cell close by the palace; everything was uncertain, insecure, trembling in the balance. I wished vainly that I could again look into that Sphinx emerald, for reassurance and its calming effect on the nerves, but this was impossible.

Day after day, and no news; that accursed woman had been caged for nearly a week now and Tii reported she was troublesome—trying to buy a guard, trying a dozen stratagems. I waited, desperately hoping against hope. Then, early one morning, one of our river captains sent up word that a light galley from Tyre, flying our house-flag, had just been sighted coming up the Nile. Word at last!

I sat there fidgeting, until steps sounded and the clerk showed one of our couriers into my private office. The man saluted me.

"He lives, lord—he is safe!" he cried, and handed me a scroll. Evidently the whole firm, up north, had been on tenterhooks. "He is safe, and has taken one of our ships for Samos."

This pleased me intensely. The boy had been freed, and had kept his head, getting completely out of Persian hands at once.

His letter confirmed this. It was not only guarded but also in code, and went into few details. He was well. He had been released, had been given great gifts by the Persians, and promises that Archias & Co. would receive honor and employment from Ochus. "But," he added, "look out for a storm, and quickly. I will write fully from Samos."

SO he was safe, out of their reach! This keen intelligence of

his pleased me intensely; a true Archias, that boy! Further, it

opened to me the path of action that I needed. How true had been

the advice inspired by the Sphinx emerald: Wait! I had

waited, and now had come my reward. Break the oath I had sworn?

No, that was impossible; besides, it would do no good. Nekht was

chained in his own superstitious folly. However—

I sent out my servants—one to bear this news to the King, another to seek Tii, another to summon all company officers to a conference at once. A storm, and quickly—this meant war, and Archias & Co. must be in shape to meet it.

However, when a palace chamberlain came with a message of congratulation and delight from Nekht, and invitation to a banquet in the evening, I accepted. Then came Tii in haste. I gave him my orders.

"Attend the banquet at the palace tonight and be ready for what happens. Watch that bird-seller in the bazaars—Pharses. I may want to reach him swiftly tonight. Guard the woman well. That is all."

Last came the scribe who had taken down my conversation with Lady Merti. I ordered him to have the scrolls ready and to attend me at the banquet. After this, I was free for the company conference, which occupied most of the afternoon. I told them the truth: "Gentlemen, I am uncertain of the future. I am taking steps to hand over Archias & Co. to my son; I want him elected general manager here and now. My only concern is to insure his future and that of the company. Tomorrow I may not be here; therefore, a deputy must be elected to fill my sandals if I turn up missing. Business is business; the company must go ahead regardless. As to his personal future, I shall take charge of that myself."

It was a hot session, but nobody was giving me any back talk and things were done as I directed.

Then I climbed into my litter and proceeded to the palace.

I shall pass over needless minutiae; the banquet was a grand one, and I was heartily congratulated by all on my son's safety. Nekht honored me with the ancient title, "Friend of the King" and in his speech stated that within a day or so he was leaving for a temporary camp near one of the great Sphinxes, where he would inaugurate the beginning of the reparation work. Then he turned to me.

"Now, Archias! I promised you that if things turned out well with your son, I would grant whatever request you might make. I reaffirm that promise now. Ask whatever you will; it shall be granted."

I rose and thanked him. "I do have a wish, my lord; it is that for one hour I may sit upon your throne in the great audience hall and be for that hour the unquestioned King of Egypt, with all your power."

There was a terrific outcry from council and nobles and princes; they called me upstart Greek, sacrilegious blasphemer, and all the usual things. Nekht commanded silence and said:

"Friends, Archias is an honest man and one whom I would trust with more than life. My word is given and shall be kept. Bring out the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt. For the hour he wears those crowns, Archias shall be King of Egypt in name and fact. Come, everyone—to the great hall!"

Off we trooped, palace guards leading the way, and the looks on some of the faces made me chuckle. More than one man there had reason to fear old Archias; however, I had no concern with them. In the great hall of audience, Nekht handed me to the golden throne-seat, took the heavy double crown, and placed it upon my head, then saluted me.

"Hail, King of Egypt!" The salute was repeated after him. The moment had come; for an instant I sat with fear shaking me; then I summoned Tii and the captain of the guards.

"Take men," I told them, "and bring before me the woman you are keeping confined. Also, send and arrest Pharses the bird- seller and bring him here. Let him be the first led before me. My friends, I am going to deal with certain enemies of Egypt in my hour of rule; but let none of you be troubled. Where is my scribe?"

HE came forward and saluted me. I indicated him to Nekht.

"Royal Nekht-nebf, it is my command that you withdraw to some private room with this scribe, and peruse the scroll he carries. Perhaps you have some fear?"

Nekht smiled. "This is the thirtieth dynasty that has ruled Egypt, Archias, and never has a truer man sat upon that throne. I obey your command. Come, scribe."

They strode away. What had first looked like some wild jest to the courtiers now became sober fact. One nitwit princeling essayed a comic role, requesting of me the fit reward for his many services to the throne; I ordered him dipped in the lily- pond in the great courtyard, and the guards took him—and there was no further comedy. At last guards walked in, dragging the trembling bird-seller.

I spoke sternly:

"Pharses, you're a Persian agent, a spy. You were planted here in Memphis to do certain work, and you've done it. From you the woman known as Lady Merti obtained carrier-pigeons that would take her reports to Persian emissaries in Sidon. She has confessed her share in this work. Now, if you tell the truth, you'll be set free, but if you lie, you shall be killed at once. Speak."

The poor devil was shaking like a leaf. In an access of terror, he flung himself on his face and babbled out everything. Lady Merti? She was actually the lady friend of a Persian general, one Memnon, chosen for this work because she spoke Egyptian fluently. Yes, the fellow had been a spy here for the year past, sending reports each month.

"Take him outside and set him free," I told the guards.

Lady Merti was brought in, walking proudly enough until she saw who sat on the throne; then she wilted, staring with great dark eyes. I was anxious to get finished with her before Nekht returned, lest he interfere, so I wasted no time.

"Lady," I said, "you have served the Persians well. You have acted as their agent here, under a false name. You imposed upon the royal Nekht and beguiled him to do your will, but now I am king. Have you aught to say before I sentence you?"

"A lie!" she cried out. "A lie! An outrage—you are not king!"

"And you are not Lady Merti, but the concubine of General Memnon," I said, and motioned to the guards. "Strip her."

THEY tore the rich garments from her—holding her

helpless, naked, for all to see.

"This is madness, Archias!" she cried. "Your son loves me, and I love him—"

"You may possibly speak the truth in that," I said, "but I am not minded to let my son marry the concubine of a Persian general. If he has lost his senses, I still have mine about me." I beckoned the guard captain. "Take her out to the gates and execute her there with the sword, as a spy of the Persians."

She shrieked, and there was a stir in the crowd, but the guards were already in motion and no one dared interfere. They had her out of the hall and away before Nekht came striding in at the side entrance.

"By the gods, Archias!" he cried out. "An amazing conversation, that! Did the woman actually force you to betray me, as she thought?"

"You've just read the record," I replied. "It's all true."

He broke out into a laugh. "It's also true that the stars have predicted great events for the night of the new moon! My astrologers are going to meet there at my camp near the Sphinx—not the one by the pyramids, but the other one, in the eastern hills—and watch the amazing conjunction of the planets. That Lady Merti did me a good turn after all, it seems."

"Then it's a good thing I caught her, and not you," I said.

"Who? What?" He broke into perplexed questions that gained ready enough answer from nobles and courtiers. I let them babble and leaned back. What was done was done. Nekht, listening to what was told him, went white with rage, called a guard, and learned that the woman was dead. This overbore everything else in his mind and threw him into a fit of fury. Spy or not, he never would have killed her, as I well knew.

"I've had my way, and I'm wearied." Taking off the heavy double crown, I held it out to Nekht. "Take it; I've had enough. If any remains of the hour, I resign it. I've done my best, not for you, but for my son and his future."

"Aye," he said, "as I have for mine, the last of the princes of Egypt! But you killed her, Archias—you murdered her, that woman sent by the gods, that glorious woman! I can't forgive that. Guards! Here—this man is a king no more. Into the royal prison with him, at once."

Sent by the gods—why, the man was so besotted by superstition he hardly knew what he said! They led me out, the courtiers jeering at me. I cared not. Nothing mattered; in the prison cell I dropped to the mat with exhaustion, and slept. My work was done...

Two days, three—how long I lay there, I know not. I saw no one, ate what was shoved at me, paid no heed to anything; then guards ordered me forth and set me in a long column of tramping wretches—slaves marching down to the ships. Once aboard, we went down the mighty river, slaves going to their labor at the Sphinxes. We disembarked at the east bank and were lashed up through the hills, past the forests of trees turned to stone in ancient times, and so at last to the camp near the huge westward- facing Sphinx, buried to the neck in blown sands.

From my quarters in the slave camp I could see this great image of stone; it was like looking at the tiny image in the emerald. I looked at it a while before falling into exhausted slumber, and wondering at its meaning; then closed my eyes. This was the end, and I had no regrets. I could not survive the labor and the whips, and I knew it.

With morning, one of the overseers came when the slaves were being turned out to work, and took me aside.

"Lord Archias, I used to work for your company," he said. "Give me an order on your head office for a gold ring, and I'll see to it that you need not labor. Eh?"

I gave him an order for a dozen rings, and went back to my mat and lay there. Age and the journey here had broken me; I could scarcely move. A day passed, two days, and I began to feel more like myself. With the next night, I looked at the sky and saw the faint, thin horn of the new moon hanging there. This was the time of crisis foretold by the astrologers. At this thought, I cackled with ironic amusement, and rolled up to sleep.

Morning came. We were fed, and the slaves filed out to their work. I sat on my mat, looking out westward to the Nile valley, and the shadowy tips of the Pyramids against the sky. A short quarter-mile from the slave camp stood the gorgeous tents of the King's encampment. From these tents a single figure was approaching—a horseman wearing a common blue robe and turban, but riding one of the King's magnificent chargers.

He came straight to the barracks, came to where I sat, and dismounted. Not until he walked over to me and I saw his face, did I recognize Nekht.

"Greetings, lord of the two worlds!" I saluted him ceremoniously.

He said nothing, but sat down. His face was gray and haggard.

"Archias," he said at last, "my son is dead. You know what that means."

The words gave me a shock; yes, I knew what that meant to him.

"An hour ago a courier reached me," he went on. "Night before last, Ochus himself suddenly appeared with his army, and stormed Pelusium, then wiped out our whole army. My son was killed." He lifted his head and looked at me. "You think I wronged you, Archias; but I could not. I arranged that you should do no labor. I meant to free you. I do it now. Take this, get a horse from the tents yonder, and get off to Memphis before the news is known generally."

From his finger he twisted the big blue scarab ring that was his royal signet, and held it to me. I took it.

"But my lord, I cannot desert you!"

He laughed harshly. "It is I who am deserting. The astrologers met last night. I listened to their patter and learned the truth. You were right, Archias; they are a pack of fools, and I am the greatest fool of all. My superstition has lost Egypt. My son is dead; my house has come to an end. The thirtieth dynasty is finished. Go, make your peace with Ochus, and prosper. The gods be good to you!"

He stood up.

"But where go you?" I demanded. "There is still hope—"

"For me there is nothing." He took something from his girdle and I saw a flash of green. It was the Sphinx emerald. "I take this, Archias; I ride into the western desert, to the Siwa oasis or beyond. I've sent a courier to Ochus, abandoning the kingdom to him. I shall never return again to Egypt. Would to the gods I had listened more to you and less to my proud foolish heart! Farewell."

He mounted his horse, and rode away—the last of the house of Nekht, nevermore to be seen among men.

As for me—well, Archias & Co. flourishes under Persian rule, and my son is high in favor with the present Great King, Darius. So I should be happy in my old age. Perhaps I would be, did not my heart turn so often to the vast, empty western desert where a lonely man vanished forever with the Sphinx emerald. Like him, I have but one last word to give—

Farewell!