RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

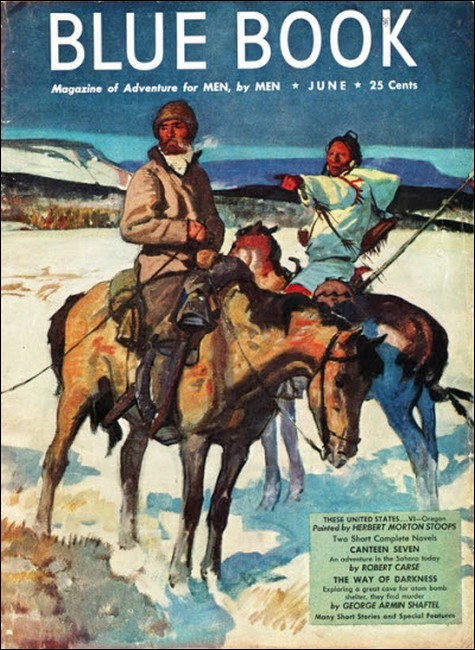

Blue Book, June 1947, with "The Reward of Nostradamus"

Catherine de Medici coveted the Sphinx Emerald. And when the King gave it as a reward to his physician, Dr. Nôtredame rode in dire peril of his life.

THE Comte de Vergy, Royal Equerry, intimate friend of the King, and easily the most influential noble at court, was a handsome, swaggering, arrogant fellow-not half clever, but apt at worming himself forward. One of his methods was to pay much quiet attention to the little Italian princess Catherine de Medici, who would be Queen of France one of these days.

Catherine was extremely plain, but was clever enough to invent the sidesaddle in order to display her one beauty, a well-formed leg. She was highly superstitious, like any girl of nineteen; and having few friends at court, she welcomed the courtesies of Vergy, and ultimately made him her confidant in the matter of the Sphinx emerald.

Catherine and her husband the Dauphin were on hand because the King was believed dying. This was in the summer of 1538. King François had come to Orléans because of its healthy air, and occupied the huge Hôtel Groslot.

Incurably ill, outworn by his vices, François was doomed and accounted dying; but while he lived, he was very much King of France.

On an afternoon, Catherine sat in her apartment, sewing, her attendant ladies at a little distance, while Vergy sat with her, fingering a lute as he talked. Demure as a mouse, careful to avoid scandal, keeping herself well out of the court picture, Catherine saw everything that went on. Despised as an Italian by the incredibly haughty French nobles, she was ever on the defensive, and was most careful to shun their jealousy and envy.

"And you, M. de Vergy, do you think the King will die?" she was asking.

"They say his physician, Maître Guillaume Chrétien, has given up hope," he said, pulling a sad face.

She smiled faintly as she eyed him. "If only someone would do something for me-something wicked, perhaps," she sighed, "he might ask any favor in his heart and find it granted-some day."

The significance of her words could not be missed. Vergy met her eyes-and promptly laid aside his lute.

"I am that someone, madame," he said softly. "And I can be discreet as the dead."

"An ill omen-be careful, my friend!" She frowned slightly. "You know the necklace His Majesty usually wears?"

"Certainly, madame. A gold chain made for him by Cellini; pendent on this chain is an emerald of size, but poor in color."

"The emerald, the Sphinx emerald," she breathed. "The most wondrous I ever saw!"

Vergy shrugged lightly. "One is like another, to me."

"Not to me, monsieur." Her dark eyes lit up; excitement flushed her olive cheek. "More, that stone is rightly mine, belongs to me! The King gave it to me when I came from Italy to be wedded. I wore it, came to cherish it dearly-and then he took it back. He borrowed it from me-and kept it. He refuses to part with it, and laughs at me when I beg for it back. And I must have it, monsieur-I cannot lose it-I must not, I will not!"

Vergy, scenting intrigue and high profit, was all attention. He was not a bad sort, but high-tempered, an expert swordsman, and keenly ambitious.

"Suppose," she went on under her breath, "suppose he-he should die?"

"Then you, madame, will be Queen of France."

She gestured impatiently. "I am thinking of the emerald. You know what will happen. A mad scramble for jewels, for gold, for power-his mistresses seizing what they can, his attendants grabbing at everything within reach!"

From her ladies came laughter at some jest; Vergy murmured:

"Madame, I comprehend-say no more! I shall make myself responsible for that chain and pendant. It shall be my privilege to see that it comes safely to you. Is there any person of your suite whom I can trust, in case of need?"

"Lorenzo," she breathed, and looked up. "Here he comes now."

Lorenzo approached. He was one of the few Italians left in her service, his position being too humble to attract French jealousy. He was one of the grooms-a dark-visaged fellow with crafty eyes, lean and scarred of face. He bowed profoundly to Catherine, delivered a message, and departed cringingly.

"Is that man in your confidence, madame?" Vergy asked incredulously.

She assented. "He is more than he seems, a very able Florentine. He serves me."

The ladies approached. Vergy rose, bowed, and took ceremonious leave.

"Farewell, madame. I repeat, you may rely absolutely upon me."

Catherine looked after him, hiding a smile in her dark eyes....

On the following evening Vergy stood in the royal antechamber with a group of courtiers. He looked at two soberly clad men who had just entered, their birettas or square bonnets proclaiming them master physicians.

"Who," demanded Vergy, "is that short red-cheeked fellow with Guillaume Chrétien, the King's physician?"

Glances were directed at the pair, and one of the group made response.

"Oh, that's a country doctor from Provence-M. de Nôtredame, I think the name is. Another of these rascally medicos who hopes to cure the King. I hope he pulls His Majesty together enough so that we can return to Blois; I hate this accursed rathole."

IN those days France had no capital. The focal point of the

realm was wherever the King happened to be, and François was

ever restless, ever changing his residence. There was no royal

palace at Orléans, but one place was as good as another to die

in.

Chrétien, the King's physician, was famous in his own right, but no less so than his friend and colleague, with whom he stood talking. Formerly professor at Montpellier, greatest college of medicine in Europe, Michel de Nôtredame had thrown up his position in order to combat the fearful pestilence raging in Provence. He had come north to Orléans for a few days only, to purchase drugs of which he stood in dire need. As they talked, Chrétien handed him a small horn box.

"There's the prescription you wanted made up; I watched the job myself. But these simple herbs can have no effect, Michel. He's done for. That abdominal abscess will finish him. Why waste time with a mere salve of herbs?"

"Not being a great man like you, Guillaume, I seldom make predictions," said the visitor with a trace of irony. "I must work with simple things, not with such stuff as powdered pearls and horns of unicorns. How long do we wait here?"

"God knows! Until summoned. But have a care. They tell me he's sadly irritable today, flying into a passion at the least excuse-a result of his melancholic humors."

"More likely from deprivation of the goddess he has so long worshiped."

At this cynical remark, Chrétien glanced about cautiously. One must be careful in this antechamber where so many of the court gentlemen stood about; a loose word could destroy a man. Life was cheap; envy, jealousy, assassination were everywhere.

"True, no doubt." Chrétien spoke now in Latin, for safety's sake. "He sees beautiful women all around; both his natural vanity and his insensate desires are affected by enforced virtue. Make him no promises, I beg of you. He has tried everything known to science, without help."

"Much that was formerly known to science has been forgotten," Nôtredame murmured.

He was a smallish, robust man, lithe and vigorous, with broad brow, straight nose, rosy cheeks and extremely bright gray eyes above his clipped, graying beard. He had made a great name for himself fighting the plague-the same plague which had swept away his immediate family; but he did not always subscribe to the conventions of his colleagues.

"Who," he asked his friend, "is that handsome, arrogant young noble preening himself in the adulation of the throng around him?"

Chrétien looked. "That's the Comte de Vergy, present favorite of François. Rather a decent chap, but a swordsman and duelist. Why do you ask?"

"Curiosity. I have an uneasy suspicion-intuition, perhaps-that he and I are fated to be friends-or enemies.... Ah, at last!"

They turned, as the doors of the inner chamber were opened, and those who had gathered for the royal coucher came out.

Monluc, a scarred Gascon soldier, came to the pair and bowed.

"He's ready for you, Maître Chrétien. I was sent to summon you."

Nôtredame was presented to the Gascon gentleman, whose face lit up.

"Oh, I've heard of you!" he exclaimed. "You're that man Nostradamus who they say has brought the plague under control down south by his magic powers!"

"They exaggerate, monsieur," said Nôtredame. "But we must not keep the King waiting."

They went in. This country physician knew little of courts and their ways, but was no whit awed by his surroundings. He found himself before a great figure perched in a huge bed whose curtains were partly withdrawn for the interview. This was the Valois, center of all majesty and power in the realm, master of such profligacy and splendor as France had never known-this huge, bloated, swollen shape, this face of fringing beard and pendulous dewlap and quenched eye, whose tasseled nightcap topped it like a ludicrous mocking crown. A torrent of groans and profanity poured from the lips of François.

"So here you are, miserable charlatans who pretend to cure and can only torture! Thrice-damned angels of Satan, a pox on your whole tribe! Chrétien, where's the fellow you promised to bring? Ah, I see him.... Step forward, you! I've heard of you, a sorcerer who conquers the plague with wizardry-"

The croaking voice failed of effort. Nôtredame was presented and bowed profoundly.

"Nôtredame-yes, that's it, Nostradamus," said François. "Do you know that sorcerers are sent to the stake? All alike-doctors, sorcerers, astrologers, damn 'em!"

"Sire, M. de Nôtredame desires to present Your Majesty with a new remedy which may afford relief," Chrétien said smoothly. "He is one of our most accomplished physicians, notably honored by Montpellier. I am prepared to vouch for his remedy, and for him."

"Pardieu, well spoken!" said the King. "There are few men for whom I'd say the same. You always were an honest rascal, Chrétien. Bring lights, here! Let me have a look at this sorcerer."

A chamberlain brought a candelabrum to the bedside, and François scrutinized the visitor with suspicious gaze.

"Remedies! There are none," he said thickly, and cursed. "This damned pain has me in the sweat of purgatory. If you rascals were any good, you'd be able to relieve it instead of feeding me vile concoctions which effect nothing."

Nôtredame came close, looked at the King, and smiled a little.

"Sire, my remedy is a penetrating salve, not a draught. If Your Majesty will allow me to examine your pulse, I may somewhat relieve your immediate ills."

Nôtredame took the huge flabby hand, held it for a moment, and motioned for the other; François complied. Quietly, Nôtredame began to speak of Avicenna and his theories; his musical voice flowed softly on as he discussed the Moorish savants and their ideas of art and beauty-subjects which fascinated the Valois.

"Ma foi, I'm resting easier, indeed!" grunted the King. "Come, lean closer! Predict how long I have to live."

"With Your Majesty's permission, I'll make a more pleasing prediction...."

Leaning over until his lips approached the ear of François, he murmured a few words quite inaudible to those around. The King's eyes opened to their fullest extent. A laugh rumbled through his ponderous expanse and came to rest upon his lips-such a laugh as he had not uttered in long days. For an instant he was his old jovial, charming self.

"You lie, you rogue, you lie!" he croaked.

"Pardon, Sire, it is the exact truth." Nôtredame drew back. "And now permit me to withdraw, while M. Chrétien applies the salve-"

'Wait!" came the order. "Will it cure me?"

"Sire, only the grace of God can effect a cure," Nôtredame said calmly, "but my belief is that the salve will afford great relief."

"Very well, I understand. Come, Chrétien! Here's the old belly you should know so well; work your will upon it."

The salve was applied, the interview ended. The two friends walked out together, donned cloaks and birettas, and passing the dour gaze of the Scots Guards on duty, gained the dark streets. Chrétien took his friend's arm, speaking softly.

"Michel, it was marvelous! He was like a bawling calf, and you cured him on the instant! What did you do?"

"I'm ashamed of you. Minor hurts irritate themselves into a fever that aggravates them; a calm presence, a few words to distract the mind, and they lessen in importance. You, so famous for your bedside manner, should know this."

"A king is very different; especially François. And what was the secret which worked a very miracle upon him?"

Nôtredame chuckled in his quiet way. "I told our good patient that tomorrow afternoon I'd give him a prescription of Avicenna's which, within a week's time, would enable him to taste all the delights of marriage without its drawbacks. I'll have to get the prescription made up in the morning."

The other clucked his tongue, horrified.

"Well-it's a risk. If the salve works, and you also accomplish this prediction, your fortune's made!"

"Many false prophecies are laid at my door," Nôtredame rejoined dryly, "but those which I myself utter are infallible, I assure you."

Nôtredame, an unassuming man who put on no airs, had not even a lackey to serve him. He had come to Orléans to purchase a stock of drugs that he needed, and Chrétien had insisted on dragging him to look at the King.

THE next day he was out early, about his business. He meant to

get away as soon as he was free of the royal patient, on the

morrow if possible, and get back to the plague-stricken south

where he was sorely needed.

The two thousand-odd persons of the court had filled the old city of Orléans to bursting, and amid the gay rout the gray-clad figure of Nôtredame drew no eyes. He finished his purchases, watched a chemist put up the secret Avicenna prescription, then started home. He was passing the hostel of the Three Emperors, when a heavy hand fell on his shoulder and a tremendous voice burst forth in the Provençal tongue.

"Saperlipopette-Nôtredame, of all people! Thunders of heaven, man, embrace me!"

He was crushed in the arms of a giant-a huge red-faced, awkward, roughly clad man, no other than Sieur Palamedes Tronc de Condoulet, seigneur and wine-grower of Salon in Provence, whom he had known for years.

Nôtredame freed himself, laughing. "A surprise indeed, old neighbor! What are you doing here?"

"Came with a present for the King, a cask of our best wine," declared the other, with rolling rustic oaths. 'Those accursed courtiers pretend they can't understand me, and pass me from one to another and keep putting me off-"

Nôtredame clapped him on the back. "Listen: The King occupies the Hôtel Groslot. I'm to see him early this afternoon. Come there, ask for me or Dr. Chrétien, and we may be able to help you. Now pardon me, old friend, I must hurry to keep an appointment. We'll meet and talk later, eh? Right."

Knowing the big, kindly, somewhat dense Provençal would talk by the hour, he did not hesitate to free himself, since noon was at hand. Despite his haste, he was pleased and warmed by the meeting. A sterling fellow, Condoulet, with heart of gold.

Upon reaching home, he found Chrétien gone and no sign of lunch. He got himself some bread and cheese, and was eating it when his host burst in upon him hurriedly, with panting speech.

"Michel! He has sent for us-one of his gentlemen came-will meet us at the Hôtel Groslot. He says the King is very cheerful this morning and much better-hurry, man, get ready!"

"I'm ready. No haste. You seem astonished that all has gone well. I should be astonished if it had not."

Chrétien bustled him off. "Ah, Michel! Not even a royal command flurries you! Where did you get your eternal poise, your amazing composure? I suppose one must be born with such a gift."

"It can always be encouraged to grow. Easy, now."

With quiet words, Nôtredame calmed the hurried excitement of his colleague, told of meeting his old friend from Salon; and presently they reached the royal residence. Crowds of city folk were clustered outside the line of Scots Guards to get glimpses of the great, and a gentleman of the King's suite awaited them, bowing to Nôtredame with surprising respect.

"His Majesty is in the garden," said he, leading them into the courtyard. "He wishes to see you at once, so come this way."

They passed through the building into the garden, and as they traversed the graveled paths, it was the turn of Nôtredame to be surprised. A gay awning had been spread beside a marble fountain, and here sat François, talking with Manluc, Vergy and the Comte de St. Pol, the main groups of courtiers remaining at a little distance out of earshot.

And what a François it was! The groaning hulk of last evening was gone; the nightcap was replaced by a jeweled bonnet. The puffed and enormous shape was clad in a magnificent suit of white and gold; the heavy long-nosed features were laughing and radiant. The Valois was himself once more, shrewd, jovial, great- hearted, eking out his words with rapid gesticulation.

"Good day, Maître Chrétien," he wheezed. "Ah, Nôtredame, prince of magicians! Do you know that your wizard salve has banished my ills, as you promised?"

Nôtredame bowed. "Sire, when Dr. Chrétien approved my prescription, I knew that it could not fail."

"Neatly said, my friend. Hm! I seem to have a memory of something else, a voice whispering at my ear. An angelic voice, shall I say?"

François shook with laughter. Nôtredame advanced, and in his

broad palm laid a curious little box of metal, Byzantine or

Saracen work, exquisitely enameled.

"My faith!" The King, who was an excellent judge of such artistry, eyed it with quick pleasure. "What admirable enamel! Limosin himself never made better." He opened the little box and glanced at the tiny pellets it contained.

"If Your Majesty will take one pellet with each meal, or not above four a day," said Nôtredame, "I believe that in a week's time the prediction I made you last evening will be fulfilled."

"So?" A glint came into the shrewd, dulled old eyes. This man, like every crowned head of the period, had lived most of his life in dread of poison. "Suppose we try this noble medicine on M. de Monluc, yonder-what say you, Nôtredame?"

Glancing at the scarred, stalwart Gascon, Nôtredame smiled slightly.

"Sire, that were a pity; indeed, a very sad waste. Allow me to prove the honesty of my own medicine." So saying, he reached out, took several of the tiny pellets, and swallowed them.

François, holding his vast belly as mirth shook him, went off into a roar of laughter. Monluc grinned. The Comte de Vergy made some comment that sent the King into a fresh spasm.

"A waste, says he," came his gasping croak. "A sad waste-ha, Monluc, he has heard of your reputation among the ladies! A pity, says he.... Come hither, Provençal! You've done well. Upon my word, I love you! We must keep you here at court, make a place for you-eh?"

"Sire, you need me not; and Provence, smitten by the plague, does. Maître Chrétien has far greater skill than I."

"Ha! You scoundrelly doctors always pat one another on the back. Your pardon, Chrétien," Francis added quickly. "I meant no reflection on you. God knows you're one of the few I trust with my whole heart! Come, Nôtredame: You've done for me what no other could do. You promise what all the others have denied. What reward seek you?"

"I do not give my help for rewards, Sire," Nôtredame replied, bowing. François peered at him, saw that he really meant the words, and grunted.

"So? On your knee, fellow-on your kneel" As Nôtredame obediently knelt, the King snatched off a chain of beautiful gold links bearing an emerald pendant. He put it over the head of Nôtredame. "There, my favorite of all jewels for you, man-even if it did break the heart of Leonardo the painter. Cellini made the chain for me. Take it with my blessing-if I didn't value it so highly I'd not give it to you. Maître Chrétien," he added, taking a ring from his finger, "accept this with my thanks. Whenever you have more friends like this man, bring them to me without delay."

AS he rose, Nôtredame caught a glimpse of the face of Vergy. It

astonished him, so contorted was it with anger and dismay.

However, thinking he must have made some mistake about it, he

dismissed the matter from his mind.

Rewarded and dismissed, the two, bowing ceremoniously, backed away and left the garden, passing through the building toward the entrance courtyard.

"If you'd come to court as he wishes, you'd soon be the greatest man in France!" Chrétien said softly.

"Or the greatest rogue. More likely the latter," said Nôtredame, as they came into the courtyard. "Hello! Wait a bit. I have business here.... That's my friend from Salon!"

The Scottish archers of the guard were clustered about two figures, their officer and a huge man, roughly dressed, whose words rolled on the air with a rich Provençal accent.

"But I wrote to him!" he bellowed. "I tell you, I wrote the King a letter, and he is expecting me!"

A guardsman tipped Nôtredame a wink.

"This fellow," he said, grinning, "has a name exactly like a Provençal oath!"

"The King will know of me," roared the visitor. "Send to him, you fools! Ask about my letter! Find his physician, or Maître Nôtredame, the physician of Salon-"

Nôtredame pushed forward and spoke loudly.

"Sieur Palamedes Tronc de Condoulet, is it not? Greetings, monsieur!"

Condoulet turned, recognized him, and beamed delightedly.

"Ha! Look there!" He pointed to a horse and cart, detained by the guards, and gesticulated frantically. "I bring the King a cask of our finest vintage, and these popinjay rascals say it might be poisoned!" He went into a storm of fantastic oaths, amid the laughter of the Scots.

Now, the King's physician was an important personage, and anyone just received in private audience was superlatively important; the name of Nôtredame had been on all lips. Consequently a chamberlain came bustling up, swift at the chance to curry favor.

"What is wrong, messieurs? Can I render you any assistance?"

"If you will have the kindness, yes. Have that cask of wine set down from the cart and opened," said Nôtredame. "Let us see if it be good wine or not." To the gentleman from Salon he spoke in Provençal, which no one else understood. "Leave this to me, friend."

Now there was brisk movement. The cask was brought from the cart and opened as Condoulet directed. A number of courtiers, attracted to the scene, looked on amusedly. The golden necklace worn by Nôtredame, which everyone knew for that of the King, aroused swift interest and discussion.

The chamberlain, his eye also on that mark of distinguished favor, approached with a goblet.

"You are serious, monsieur, about tasting the wine?"

"Certainly. I shall do it myself." Nôtredame took the goblet. Wine was poured into it from the cask. He tasted, drank, and beckoned Guillaume Chrétien. "Here, sample this admirable vintage. Have you any hesitation in recommending it to His Majesty?"

"My faith, no!" said the other, after emptying the cup. "I only wish I could get a cask of it myself!"

"Then,"-Nôtredame turned to the officious chamberlain-"suppose you present the gift with word that I and Maître Chrétien beg to recommend it highly. And you might present the Sieur de Condoulet also. If you can do this, pray consider me deeply in your debt."

The chamberlain was overjoyed. He departed, dragging Condoulet after him, and flinging orders about the wine-cask. Nôtredame, laughing, passed out of the Hôtel Groslot into the tree-shaded avenue.

His friend plucked at his sleeve.

"Why this fantastic byplay, Michel?"

"Condoulet and I are old friends and neighbors. We're country folk, we Provençals. Peasants at heart, helping a neighbor at need."

Chrétien, who had as yet eaten nothing, took his guest home, insisted upon having a bounteous meal set forth, and together they curiously examined the emerald and chain. It was one the King had always worn, said Chrétien, an odd, lumpish stone, poorly cut.

"You take it and keep it," said Nôtredame. "I dislike jewels."

The other gaped. "Impossible, man! The King's gift? No, no, it's yours to keep."

"I don't like to own things. I've lost my worldly ties, and desire to own nothing."

"Don't be absurd. This is a famous emerald-the Sphinx, it's called. I don't know why. There was some old scandal about it-connected with the Italian artist Leonardo, if I recall, when I was a boy. Wait till I get an enlarging-glass, and we'll have a look at the stone."

He had barely returned with the lens when Condoulet came bursting in upon them, having tracked Nôtredame to his lodgings here. He was excited, voluble and gesticulating-the proudest, happiest, most blithesome man in France. He embraced both physicians in a fervor of emotion.

Yes, he had been presented to the King, had kissed his hand-he, Tronc de Condoulet, bourgeois of Salon and merchant in wines-though it was true he had a right to the de of nobility, his grandfather having belonged to the petty noblesse-that is to say, his grandfather on the maternal side, who was an Auvergnat....

He talked on interminably. The King had accepted his wine, had thanked him most graciously, had accepted the loan of a few thousand crowns as a token of fealty. Massive, radiant, so overflowing with animal spirits that the room seemed too small to hold him, Condoulet at length ran down, gulped a glass of Chrétien's wine, and vowed he would send the physician a cask of the same vintage he had brought the King.

"Curious, Guillaume," said Nôtredame, who had been examining the emerald under the glass. "Take a look. There's actually a Sphinx in this gem!"

SO there was, indeed. Enlarged, it was plain to see-the flaws in

the stone, by an odd fantasy of Nature, took the exact semblance

of the Sphinx sitting in a field of glittering, flashing green.

More, there was something keenly fascinating about the enlarged

view thus obtained. Chrétien could not take his eyes from

it.

"Magnificent, Michel," he said, awed. "There's magic in the appeal it makes to the imagination. One sees things in the stone-"

"Glimpses of the moon," said Nôtredame with a careless laugh, and turned to the Provençal. "When do you return to Salon?"

"Now! Immediately! That is to say, early in the morning. I'm stopping at the Three Emperors."

"Have you a horse for me? If so, we'll travel together."

Condoulet was overjoyed. He regarded Nôtredame with the awe and veneration any rustic pays to a great physician; the idea of traveling home together elated him. He agreed at once to stop by here and pick up Nôtredame in the morning, and with this took his departure. Chrétien, who had been summoned to visit two ladies of the court who had need of his services, reluctantly handed over the chain and enlarging-glass to his friend, and went his ways.

MICHEL DE NÔTREDAME took the chain into the garden and began a

careful scrutiny of the emerald. The carelessness he had

affected was false. In reality, this emerald affected him so

acutely that he was startled and disturbed. He disliked and

vividly distrusted anything which so aroused his emotions as did

this jewel.

But why? That was what he meant to determine-why such an effect? He pored over the emerald for an hour, two hours. Amazement, even a species of fear, grew upon him. The more he looked into this green lump of beryl, the more he saw, or fancied that he saw, in its heart. It aroused speculation, fed the imagination, suggested singular scenes and fantasies-ah, that was it! Suggestion! As a physician far in advance of his day, he knew well the power of suggestion; he used it almost daily himself; he was thoroughly acquainted with its remarkable effects. Here was suggestion-and something else as well, something darker, more sinister. The fascination this emerald exerted was gripping, almost like that of a drug....

"A mental drug, yes," he murmured, resisting the keen temptation to look anew. "Dangerous, these fancies! One feeds the brain upon them as upon mandragora; one comes back for more, ever more; one eventually loses contact with life's realities.... Bad, very bad!"

Resolutely, uncompromisingly, he put the thing away and would have no more of it where he himself was concerned. Not that he despised it. He could well conceive cases, mental cases, where it would be of the utmost value to him. The everyday opinion about such a stone, he knew, would simply be that it was bewitched by a devil. He discounted such notions, being aware that the natural world around held marvels greater than any necromance, could one but see them.

But while Nôtredame was thus playing with the King's gift, a singular scene was taking place in the apartments of Catherine de Medici.

The little princess was listening to the Comte de Vergy relate the happenings of that afternoon. There was no secret about it, of course; he spoke for all to hear, Catherine's attendants hanging on his words, and bursting with laughter to hear him jest about the doctor from the back-country.

For once, however, Catherine did not share their mirth. Instead, she sat like a cat on tension of the prowl-her lips tight, her nostrils quivering, her hands clenched tight and hard. Gone! The great jewel, the marvelous Sphinx emerald, handed over to a country doctor! It was maddening. However, many things had happened to Catherine de Medici that would have maddened other people, and she was still alive and well. She lost her tension, and when able to speak privately to Vergy, nodded calmly to him.

"There is to be dancing this evening, in honor of the King's recovery," she said. "We may talk then with greater freedom."

Cautious Catherine! They talked safely that evening, under cover of the violins and the gay laughing voices. The Comte de Vergy swore he would get the emerald for her. He had found that Nôtredame was leaving for Provence on the morrow. He could be waylaid easily enough.... Catherine stopped him abruptly.

"We must not be rash, my friend," she said coolly. "In all justice, that emerald belongs to me; the King had no right to give it away-but he did so. If anything happened to this miserable fellow here, and the King's gift were missing, there would be a hue and cry at once. Step softly. I'll send Lorenzo to you tomorrow with horses; you'll find him an excellent lackey. Follow this doctor to a safe distance-you comprehend?"

"Perfectly, madame." Vergy kissed her hand. "We'll manage it safely. Upon my honor, we'll follow him to Provence if need be, and I'll return with your jewel!"

Next morning Catherine instructed the groom Lorenzo, in her careful way:

"Serve M. de Vergy faithfully-but remember you serve me as well. Don't let him overtake this rascally doctor too close to Orléans; and when the fellow is overtaken, make certain that he does not complain to the King. Is my meaning clear?"

Lorenzo showed his white teeth in a merry laugh, and touched his dagger.

"Perfectly, principessa! He shall complain to no one-I promise it!"

HAPPILY ignorant of perils, Nôtredame bade farewell to Maître

Chrétien and set forth with the Sieur Condoulet for sunny

Provence. Before they were over the long stone bridge across the

Loire, Nôtredame caught sight of the barges ascending the river,

and had a notable idea.

It was a long and weary road for two men on horseback-Orléans to distant Lyons, and thence down the Rhone a hundred and thirty miles to Avignon-Papal territory, not a part of France; and the rest was but a step to Salon, for which Condoulet was bound, and Aix, the capital of Provence, Nôtredame's destination. The weariest part of the journey was from here to Lyons-why not, then, ride aboard one of those barges toiling up-river, which could carry them and their horses to boot?

No sooner said than put into effect! And this was why the Comte de Vergy picked up no sign of his quarry until he reached Lyons, and then found himself far behind. With fresh horses, he and his lackey now spurred on desperately. But Nôtredame and the Sieur Condoulet jogged on together, enjoying one another and the countryside as they journeyed.

They came to Vienne, viewed the Roman remains and went on to Valence, thence on to Montelimart and St. Esprit with its magnificent bridge of twenty-six arches. They could smell Provence in the air now, and pushed ahead eagerly to Orange, with Avignon the next town on the way. Here at Orange, however, Sieur Palamedes Tronc de Condoulet over-ate of an enormous eel pie, and Nôtredame had to physick him, which delayed them a day.

They left Orange on an early morning, thinking to make the short distance to Avignon and get in early. Nôtredame knew the Archbishop who ruled there for the Pope-had, in fact, pulled him through the plague only the year previous-and assured his companion of a right warm welcome. The two were ambling along, a league or less this side of the Papal border, when the Comte de Vergy and his lackey at last caught up with them.

Nôtredame had noted the dust-spurts behind, and on making out two riders overhauling them, spoke to Condoulet, who laughed and loosened his sword in its sheath-an old and over-long rapier. Sieur Palamedes, who was more pugnacious if less witty than Sir Palamedes of Troy-town fame, looked forward hopefully to attack by brigands. However, the two pursuers overtook them amicably, called on Nôtredame by name, and the latter amazedly recognized the Comte de Vergy. Not bothering to dismount, the Comte went direct to business, unaware of his lackey's secret instructions, and minded to avoid trouble if possible.

"Monsieur," he said, reining in, "I have followed all the way from Orléans, trying to overtake you. His Majesty sent me after you, monsieur."

Condoulet, finding to his disappointment that it was not an affair of robbers, applied himself with noisy gulps to a large leather bottle of potent wine, which he had obtained at Orange. Nôtredame, although astonished by the words of Vergy, did not doubt them.

"Indeed? And for what purpose, may I inquire?"

"He has repented of the gift which he made you, monsieur," said Vergy, not caring to waste great politeness on a provincial like this fellow. "He desires you to return it to him, and to permit me, in your courtesy, to make good its value in some other fashion. I trust this will prove to your taste, good monsieur-"

Vergy's approach had been carefully weighed, and ordinarily would have succeeded perfectly; Nôtredame would have turned over the emerald with the greatest indifference. But the courtier's words were interrupted by Condoulet, who dropped his bottle and broke into furious oaths.

"What's all this? Do I understand you to say that the King, King François, presented M. de Nôtredame with a jewel and now wants to take it back again?"

"You do," coldly replied the Comte Vergy.

The Provençal exploded wrathfully. "Then, monsieur, I say to your face that you lie!" he thundered. "No one shall so basely insult the King in my presence! The King is my personal friend, and his honor is as my own. Nôtredame, this is all a scoundrelly plot to rob you of the jewel!"

Vergy was dead white with fury and dismay, for Condoulet was absolutely correct. Meanness or lack of generosity had never been a fault of François of Valois.

At this instant Nôtredame intervened, intent only upon avoiding any trouble.

"Tronc, for God's sake hold your tongue," he snapped, and turned to Vergy. "I beg you, M. de Vergy, to overlook the hastiness of my friend. The emerald, I assure you, is at His Majesty's service. I shall be glad to confide it to your care."

While speaking, he reined in his horse beside that of Vergy, and took the emerald and chain from his pouch. The Comte de Vergy accepted the jewel with a polite word of thanks-and it was here that his lackey, finding himself close behind Nôtredame, gave his horse a kick forward and slid out his dagger. He was in the very act of delivering the thrust, when Condoulet intervened.

There was no time to draw weapon, to cry out, to warn Nôtredame. The Provençal merely jerked his steed around, rose in the stirrups, leaned far over and gave the unfortunate Lorenzo one buffet with all his weight behind it. Not only was the Italian struck senseless-he was literally knocked from his saddle, sent headlong to earth and left hanging, one spur caught in his stirrup. The dagger still glittered in his grip.

The Comte de Vergy exploded in an oath, whipped out his rapier, and struck in his spurs. His startled beast lunged forward and struck against Condoulet's horse. Condoulet, nearly unseated by the shock, was pinked in the arm by the rapier. A maddened bellow escaped him; his long weapon leaped forth; and he sent his horse at Vergy. He had no thought for any niceties of fence. In blind fury he slashed the nobleman across the face, knocked his weapon aside, and ran him through the body. The Comte de Vergy dropped his rapier and fell forward, lolling over the neck of his horse.

IT had happened swiftly, all in an instant. Condoulet was

roaring at Vergy to fight on, when Nôtredame, who never lost his

perfect composure, dismounted and went to the side of the

courtier.

"Quiet," he said. "I fear you've done for him. Come, lend a hand here."

Condoulet scrambled down. "He's not dead?"

"No, but he soon will be." They stretched the senseless man on the grass. Nôtredame bared the wound, examined it, and fell to making a bandage and compress. "He may live a few hours if I can stop the blood. What about the other, the lackey?"

Condoulet went to Lorenzo, tried to lift him, and straightened up with an oath.

"Tron de l'air! The fool fell on his head and broke his neck! He was about to stab you in the back when I hit him-here's his stiletto."

Nôtredame glanced at it and nodded. He finished his work, then picked up the chain and emerald, which had fallen in the grass. With a grimace of distaste, he slipped the chain over the head of Vergy. He turned to find Condoulet standing staring at him and scratching his head, heedless of the blood dripping from his wounded arm.

Nôtredame made him bare the wound, and bandaged it.

"I owe you thanks for saving my life, neighbor," he said. "But this is a bad affair. This man was the King's favorite. I'd hate to see you broken on the wheel."

Condoulet eyed him in anxious perplexity.

"Maître Nôtredame, you know everything, so tell me what to do."

Nôtredame laughed slightly, then sighed.

"We can't let Vergy die here."

"Why not? Dead men are picked up on the roads every day."

"True, but this man is a nobleman of the court." Nôtredame reflected, plucking at his beard. After all, Condoulet had saved his life. And had the King really sent for the emerald? That story began to look a little extraordinary.

"We're close to Avignon-and once there, we're out of France," he said. "We'll take Vergy along to the city-and you, Sieur Palamedes, keep your mouth shut. Not a word out of you-not a word! Help me tie him in the saddle. My friend the Archbishop can help us here, providing he doesn't learn the truth."

"But the King-the jewel-"

"Devil take them both." Nôtredame gave him an angry look. "Not a word!"

Making himself dumb, Condoulet fell to work. With Vergy tied in the saddle, they rode on toward the great rock towering against the sky.

Nôtredame gave his name at the city gates, stating that he must reach the Archbishop immediately. He was promptly passed in, and leaving his companions at the first inn they saw, hastened on to the enormous Place du Palais. At the Archbishop's palace, under the high citadel and palace of the Popes, good luck was with him. He reached the prelate at once, and was greeted with the greatest warmth, but made no delay.

"Monseigneur," he said, "my friend and I picked up and brought in an injured man, who lay by the road outside town. I think he will not live long. I can see to his hurts myself, but you might well send a priest to shrive him. Having met him recently at the King's court, I recognized him: the Comte de Vergy-"

A priest was summoned and Nôtredame hurried back with him to the inn. Vergy was still alive and weakly conscious. He looked at Nôtredame and whispered:

"Not the King wanted the jewel-it was the Dauphine, Catherine. That was her man with me. I am sorry-"

Nôtredame left him with the priest and stood in thought. So it was Catherine de Medici who had tried to get hold of the emerald in this way! Things were explained now, and the frowning features of Nôtredame cleared.

"I was right about that emerald," he reflected. "Envy-cupidity-a mad desire for it-ha! Leave it where it is, and good riddance."

He looked up as the priest appeared with a nod.

"Your friend made a good end, monsieur. That is a beautiful chain about his neck."

"It brought him to his death, so leave it where it is," said Nôtredame. "Come, Condoulet; to the palace, and no talk."

He took his friend back to the Archbishop and presented him. The prelate made them welcome; a secretary jotted down their report of discovering the injured man; and now arose the question of how to dispose of the body.

"My friend, Sieur Condoulet of Salon," Nôtredame said calmly, "desires to make a charitable offering, for the good of his soul. He wishes that this gentleman be given burial in one of the churches here, with a suitable tomb and a marble angel above it, and will gladly meet the expenses involved."

The astonished Condoulet opened his mouth, but the look he received from Nôtredame caused him to shut it quickly. The Archbishop was gratified by this laudable purpose of the gentleman from Salon, and nodded amiably.

"The old church of St. Martial, where is buried the Lady Laura, of the poet Petrarch's fancy-the very place!" said he. "The work can be done in two or three days, the gentleman buried, and the marble angel can come in due time."

Condoulet drew Nôtredame aside and got permission to speak.

"On the fountain in my garden at home," said he, "there is a marble angel. It would be the very thing, and save expense-"

"Silence," said Nôtredame. "An angel from Salon would not feel comfortable at all, here in Avignon. Be quiet."

The Archbishop, cautioned that Vergy's body might be robbed, undertook to have it entombed intact, and the matter was finished.

LATER in the evening, when they were alone together, Condoulet

took issue with his friend. A great shame, he said, to bury that

magnificent chain and jewel with the dead man. Let alone its

value, the King-

"He did not send Vergy for it." Nôtredame explained the case. "No, it is an evil thing. I earned it, so I've no desire to return it to the King. It is better off in the tomb, old friend. Between you and me, I'd not be surprised if that emerald were bewitched."

Condoulet hastily crossed himself. He was not in the least superstitious, but no sensible man would have any dealings, any dealings whatever, with any ensorceled thing!

In the days that followed, one matter lingered in Nôtredame's mind. He often wondered what King François had meant by that singular remark about the emerald having broken the heart of the Italian artist Leonardo, now dead a score of years. Nôtredame was a curious man, and would have loved to know the story, if there were a story.

Yet he never tried to learn it; he felt a distrust, an actual hatred, for that green stone with a Sphinx in its heart. Better left alone, said he, and acted accordingly.

A wise man, Dr. Nôtredame-like most country doctors.