RGL e-Book Cover©

RGL e-Book Cover©

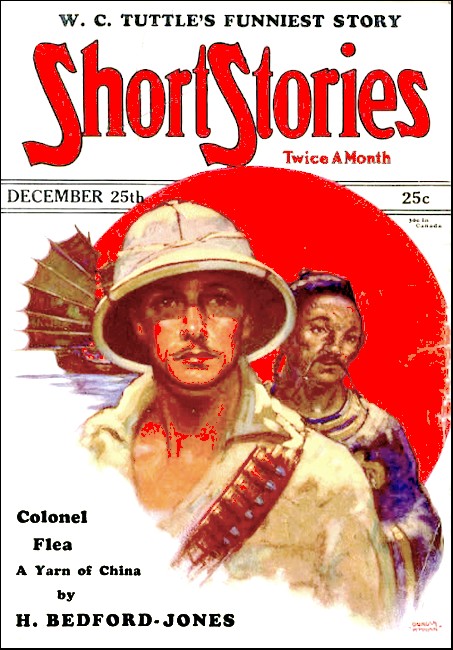

Short Stories, 25 December 1929, with first part of "Colonel Flea"

DARKNESS had fallen, so merged with the usual March fog that the lights along the railroad line were mere yellow blurs. The lights of Hankow and its sister cities made a fervid glow in the sky, but gave little illumination on earth. The train from Peking was just getting into the Ta-che-men Station, which connected with the French Concession.

The door of a third-class compartment suddenly flew open, as the train slowed at a switch before making the station proper. Anyone outside might have caught a swift glimpse of two men, garbed as officers in the Nationalist Army, rolling on the floor—and of a third figure, clad in white, leaping out into the night. The white figure went rolling, and merged with the mist.

Within five minutes lanterns and electric torches were stabbing the obscurity outside the station. Voices rose shrill; soldiers and guards scurried about, but their search proved vain. It was obvious that the escaped man had not been disabled by his fall, and therefore further seeking was vain, until daylight came or the blanketing fog lifted.

On the hillside not far from the Golf Club, just beyond the station, stood a low, comfortable bungalow whose veranda light alone glimmered in the darkness. Voices came from the servants' quarters in the rear, but the main building was evidently unoccupied for the moment. Under the veranda light appeared a disreputable figure—tattered, bloodstained, filthy beyond description, bearded with a week's scrub. The figure poised for an instant, listening, watching—then abruptly darted up to the veranda and tried the door. It was unlocked. The white figure vanished within the bungalow. Over all the vast basin of the Yangtze, over the triple cities, over the huge iron and steel mills and factories, the March fog hung thick, listless, deadening.

SOMEWHAT before midnight Jeffries Curran, Hankow manager for the International Import Company, was brought home from the club in his ricksha. He was an important member of the foreign colony—an excellent bridge player, an eligible bachelor, a gentleman of means. He was accounted handsome, being tall and slender and long jawed, he wore his clothes well, and was under thirty. Altogether a promising man, who had been ten years in China and knew his way around dark streets.

Jeffries Curran let himself into the bungalow, and then stopped short in astonishment. A light—a shaded light—was burning in his study, when it should have been in darkness. He switched on the front room lights and strode to the study door, and looked at a man who sat there reading an American magazine and sipping a brandy and soda.

"You!" he exclaimed, and his voice was not pleased. The man in the chair sprang up.

"Hello, Jeff! Come in and have a drink. Glad to see me?"

The two men shook hands.

"Middling," said Jeffries, surveying his brother critically. "You're looking fit, Donn. Hm! What the devil are you doing in my clothes?"

"Wearing them, mine haven't arrived here," and Donn Curran chuckled.

He was looking fit indeed, as well he might after a bath and shave and complete change of clothes. Tall as his brother, and of much the same build, his features were better balanced, were more keen and striking. Keen gray eyes looked out of an incisive, hard chiseled brown face, which became warm and likable when he smiled or laughed—though this was not often. His movements held a lithe suggestion of restrained power, as did his words and manner.

"Well, this is a surprise and no mistake!" said Jeffries, settling into a chair and pouring a drink. "How! Did the boys let you in?"

"Didn't know I came," said Donn. "I dropped off the night train just outside the station and slipped right up here."

The eyes of Jeffries Curran darkened imperceptibly.

"So! You're in trouble again, Donn?"

"Of course. Ever know when I wasn't?" said Donn cheerfully. "Or did you ever know me to ask your help out of trouble? You give me a night's lodging, old man, and the clothes I'm in, and I'll be in clover. Might have a bite to eat, too—haven't eaten since morning."

"I've some good cheese and crackers in the locker," said Jeffries. He rose and went to a locked cupboard across the room, and took out a key-ring. "Also beer. Open up that card table, Donn, we don't want to rout out the boys, I fancy."

"Your fancy is correct," said Donn Curran, and performed the ordered labor. His elder brother brought beer and cheese and a tin of English biscuits, laid out cigarettes, then settled into his chair again and surveyed Donn more critically.

"Hm! Thought you were up in Manchuria. Where'd you get that wale across your cheek?"

Donn Curran put fingers to a red mark on his cheek, and laughed.

"Bullet made that last night. I nearly got away from 'em then, but didn't quite make it. I've been cooped up for a week; they searched me twice a day and never found the message I was carrying. Now it'll be delivered."

He fell to eating, hungrily. Jeffries Curran surveyed him, nibbled a bit of cheese, and spoke at some length—not heatedly, however. Jeffries was seldom heated or outwardly angry.

"This is about the limit, Donn. You've knocked around China now for going on four years—"

"And seen more of it than you in ten," said Donn, with a grin. "Go on."

"Granted. More of the seamy side. You've been filibustering, handling machine-guns, running airplanes, lord knows what. Your soldier of fortune stuff has got you nothing at all, and it can damage me a great deal if it's known you're here. I've made myself a position, I have a good future—"

"Oh, sure—the old ant and grasshopper fable," said Donn Curran, laughing a little. He swallowed half a glass of beer at a draught and leaned back. Of a sudden his face became hard, tense, incisive. "Listen, Jeff—I'm no fool at all. Get me? I know about your little deal with Hsieu Chang last month and how you tipped him off to that trainload of food going north for the Red Cross, so he could grab it. Let's call the accusation stuff even, what?"

JEFFRIES CURRAN stiffened in his chair. He even turned a trifle pale.

"Don't know what you're talking about," he growled.

"Think hard and you'll remember." Donn took a cigarette, and lighted it. "You're a good little ant, and you're making your pile. I haven't made any pile, but I've had a hell of a lot of fun, and I've no skeleton in the closet. So lay off. Now, I need news. Is Yuan Si-hung still hanging on to his bit of hill country?"

Jeffries nodded, and frowned a little.

"Yuan is hanging on—the old bandit can't be caught," he rejoined. "His hill positions are all but impregnable, and we can't—"

"We?" Donn Curran spoke with a lift of his brows.

"Yes—the Nationalists. Yuan's the only one in all this part of China that hasn't submitted and can't be bought off. They've got him bottled up, I hear, and it's only a matter of time now."

Donn laughed, and his steel eyes flashed in the light.

"Jeff, I'll tell you something that'll make your eyes water," he said in a low voice. "Why is old Yuan impregnable? Because he does the buying off, that's why. Think it over."

"Huh?" The gaze of Jeffries narrowed, became intent. "What's he got to buy anyone off with? He controls one city that he's long ago milked dry, and about a hundred square miles of territory—a drop in the bucket. He's not even a war lord. He's a bandit who grabbed a chunk of good property and hangs on to it."

"By buying off the opposition," said Donn Curran calmly. "He's bought 'em off for two years now, commander after commander, general after general. I hear General Chang is in charge of operations against him now. Well, pretty soon Chang will be retiring to Shanghai to spend his money. And why has Yuan been buying 'em off? To gain time. For two years now Yuan has been sending out gold shipments, quietly smuggling 'em out and getting them off to Japan. I'm bringing him the message telling exactly how much stands to his credit in the Yokohama Specie Bank, and just where and when a boat will be waiting for him on the coast. Yuan is ready to retire, Jeff."

"Eh?" The mouth of Jeffries had been gaping; now it closed like a steel trap for an instant. "Is that straight?"

"Ever know me to lie—except diplomatically?" Donn Curran chuckled.

"Well, I'll be damned!" exclaimed his brother. "And here you're risking your neck and my reputation to get that sort of message to a filthy old bandit, a murderer, a brute who is a byword for oppression and—"

"Yep, so here endeth the first lesson," said Donn satirically. "Me, I'm doing it for business reasons. If I get Yuan aboard that ship, I clear fifty thousand gold and expenses. And he's going to get there, dead or alive!"

"Maybe," Jeffries inspected his brother curiously, greedily. "Where does his loot come from, then?"

Donn Curran ignored the question temporarily. He had a way of ignoring things and people. Some called it arrogance, some called it self-assurance; as a matter of fact, it was nothing more than his perfect balance. He was well-poised, seldom said anything he was apt to regret, and was slow to act—but his action was never slow.

"Listen, Jeff," he said calmly. "I have made all arrangements—all! You understand? I had just completed everything when a minor agent betrayed me. I shot him, but they got me. They were bringing me here, probably to torture the message or secret out of me."

"But—good lord, Donn!" exclaimed Jeffries, in sharp agitation. "They'll know you're somewhere about—they'll know you're my brother, they'll be here looking for you."

"Pipe down." Donn gave him a slow look that lashed him with contempt. "A couple of years ago up in Manchuria, old Marshal Cheng told someone I was harder to catch than a flea. The name—Ko-tsao—stuck to me. Ever since then I've been Colonel Ko-tsao; even my commissions have been made out in that name. My own name is unknown to anyone. You see?"

JEFFRIES stared at him in startled realization.

"My lord, Donn—we've all heard that name!" he broke out. "You're Ko-tsao—the chap who bombed that train and killed Marshal Cheng six months ago! You're the beggar who took an airplane into Hsian-fu and brought out two women missionaries! You're the one who raided up the river and cut off an entire Nationalist regiment and slaughtered 'em…."

"Sure, after they'd finished murdering two hundred prisoners in cold blood," said Donn, with a shrug. "That was justice, not slaughter. Yes, I'm Ko-tsao. When they caught me I was bearded and had stained my hair dark—it goes better among the natives. Now I'm fairly light-haired, clean shaven, and you'll take me into town in the morning as your prodigal brother who's on his way upriver."

"I'll be damned if I will," said Jeffries, an ugly look in his eyes. Donn took a fresh cigarette, lighted it, and then inspected it carefully.

"Wait a minute," he said. "I shan't be in the city longer than a couple of hours or so, and you can breathe freely. All I need is to get into touch with my agent here. As for being damned, my dearly beloved brother, you'll certainly be damned if you don't lend me a hand! I'd hate to start any publicity about that trainload of food belonging to the Red Cross, and destined to save starving Chinks upcountry—"

"Forget it," Jeffries growled. "I didn't mean it, Donn. Sure, I'll take you into town and make everything okay for you."

"Of course," agreed Donn calmly. "Blood is thicker than water, eh?"

If the words held sarcasm, it was not apparent to the sharp glance of Jeffries.

"You bet," he assented. "Just holler for anything you need—I'll fix you up with pajamas and so forth. But about this bandit Yuan and his loot—you didn't say where it all came from."

"Didn't I?" Donn regarded his brother with affected surprise. "Well, in the first place it isn't loot—not much! His gold shipments and his bribes are all in the form of shoe-money—but instead of being silver lumps, they're pure virgin gold. Ever hear of the Yellow Carp mines?"

Jeffries nodded with a gleam in his eyes.

"You mean the big gold mines somewhere in the hills, closed up at the time of the rebellion against the Manchus? Everyone's heard of them. The mandarin in charge massacred the entire force and blew up the mines, and they've never been discovered. Is that where—"

"Yep. Yuan has uncovered and is working them. Those mines set in a stream of raw gold to the Palace of Heaven in the old days; they could pay off the debts of all China in a couple of years. The Nationalists have just learned, somehow, about Yuan having located them. In another week there'll be three army corps and a few air squadrons moving on his little city of Sing-an—and all too late."

"Hm!" said Jeffries. "Well, I hope you pull it off, old man, I sure do! By the way, did you know I'm engaged? That is, it's understood—we'll pull off the wedding in June, I suppose."

"Engaged?" Donn gave him a slow, surprised glance. "Well, that is news! I congratulate you—I can't say I congratulate the lady, unless you've changed a lot. Who is she?"

Jeffries ignored the comment. He was good at ignoring things, too; but he and his brother did not ignore the same sort of things.

"Eleanor Armstrong—her father's a mogul in the company, been out here with her for a month. They left today on a trip down river; be gone three or four days sightseeing. Got a cracking good steam launch, English captain, fine native crew of four. And a machine-gun. So they're safe as safe."

"Undoubtedly. The river's quiet down to Nanking anyhow," said Donn, with a nod. "Well, old chap, I think I'll turn in if you can give me some sort of shakedown. Plenty of room, I imagine. So you're to be married, eh? That explains it."

"Explains what?" asked Jeffries suspiciously. Donn laughed a little.

"Why you haven't a native charmer on hand to keep you company."

Jeffries snarled, then shrugged.

"Don't be a fool," he returned, a harsh edge to his voice. "You know the custom of the country perfectly well."

"Sure. So do you. You follow it and I don't, that's the difference," said Dunn. "But what of it? I'm not sermonizing. Your morals aren't my affairs, old chap. We haven't got on well in the past, so let's try to make the future hang together in better shape. I've served with half a dozen armies, you've stuck to business; now if I get my stake, I'm going home. By the way, Jeff, who's the Nationalist gentleman in command of Hankow?"

"General Hsieu Chang," said Jeffries, almost reluctantly. Donn whistled.

"Same chap who grabbed that food train, your old friend, eh? Fine!" Donn clapped his brother on the shoulder. "All right, cheer up; I'll be gone by noon tomorrow. Now show me to my downy couch, and we'll go by-by."

In ten minutes Donn Curran, otherwise Colonel Ko-Tsao, was comfortably installed in the second bedroom of the bungalow, and, whistling cheerily, was making ready for bed.

In the study, Jeffries Curran sat at his desk writing a brief, short note in French. He placed it in an envelope and addressed this envelope to General Hsieu Chang, at the military governor's office in Wuehang, across the river. Then, smiling to himself, he sealed the envelope, pocketed it and went to bed.

JEFFRIES had a small car, which he seldom used, as the roads were none too good. In the morning he drove into the city, with Donn Curran beside him. As he was well known, his car received salutes instead of questions.

"Where to?" demanded Jeffries, once inside the walls.

"Better go to your offices," said his brother. "I'll go in with you, and then slip out quietly. I have to find a chap named Hoshino, who has a shop back of the Matsu Hotel in the Japanese Concession, but I'll get there in a ricksha or afoot."

"Right," said Jeffries indifferently. "Need a bit of money?"

"Enough for ricksha fare, fifty cents will do," said Donn. "I'll be all set as soon as I see Hoshino."

They came presently to the offices of the International Import Company, not far from the bund in E-wo Road, and Donn Curran entered behind Jeffries. Once in his private office, Jeffries produced a five-pound note and a handful of loose silver and pressed it on his brother.

"Better take this," he said. "And if you need more, come back; or if you find I can be of any help. I hope you have all the good luck you deserve, Donn—and that means a lot."

"Thanks." The two men shook hands, and Donn Curran smiled. "Don't worry, old man. If I get tripped up, they won't get my name. I'm Colonel Flea to everybody else. So long, and thanks for everything!"

Next instant Donn Curran was gone. Jeffries sat down at his desk, took a cigarette from a tin and lighted it, then pressed an electric buzzer. A stenographer entered.

"Nothing yet," he said. "Please send Erh Jen to me."

Another moment, and a thin, spectacled young Chinese entered the office. At a sign from Jeffries, he closed the door and came to the desk. Jeffries extended the sealed envelope.

"Get the next ferry and deliver this personally to General Hsieu. Send in word that it's from me and he'll see you. Tell him the person in question is to be found at the shop of one Hoshino, behind the Matsu Hotel."

"At the shop of Hoshino, behind the Matsu-no-ya," repeated the native, and bowed. He tucked the envelope into his sleeve—though he wore European clothes—and departed.

Jeffries Curran leaned back in his chair, smiled at the picture of a very pretty girl in a silver frame, then tossed away his cigarette and rang again for his stenographer. This time, he took up the letters on his desk and fell to dictation.

MEANTIME, up at the end of the foreign settlement in the Japanese Concession, Donn Curran alighted, paid his ricksha coolie, and then walked along the block to where a gaudy sign in Japanese and English announced that one Hoshino was in the importing business. The shop was small. Entering, Donn found a spectacled young man seated behind a counter.

"Do you speak English?" he inquired, and the other assented. "Tell Mr. Hoshino that Colonel Ko-tsao is waiting to see him."

The young man turned pale behind his spectacles and fairly dived through heavy curtains that shut off the rear of the shop. Next instant a stocky, pockmarked Japanese appeared and stared at Donn Curran.

"You, sir!" he exclaimed. "May I ask who sent you to me?"

Donn chuckled.

"Captain Miyoshi of Yokohama."

"Come in, if you please," and holding aside the curtain, Hoshino sucked in his breath. "You are welcome. We heard of ill fortune and have been much worried."

Donn Curran went along a passage and was ushered into a rear office where another man sat smoking. This man was introduced as Mr. Tsuma, and since he remained with them, Donn knew he must be either a partner of Hoshino or else another Japanese agent. Therefore, it was safe enough to talk.

"It is surprising to find you in Hankow," said Hoshino, proffering cigarettes. "I had certain orders, and carried them out to the letter. Mister Tsuma has just arrived from downriver; he, too, carried out certain orders. We did not know that Colonel Ko-tsao was a white man. Has your arrival anything to do with the escape of an important prisoner from the Peking train last night?"

Donn Curran nodded.

"Everything," he said. "Fortunately, neither do the enemy know that I'm a white man. I must get on my way immediately. Can you provide me with a steam launch and two safe men to take me downriver?"

"Better," said Hoshino placidly. "A launch is waiting—a petrol launch. It has been waiting, day and night, for three days. Mister Tsuma will take you to it. First, are you in any danger here?"

"No," said Donn, then paused. "Only one man knows I'm here—Jeffries Curran, manager for the International Import."

He did not miss the very slight change of expression on the face of Hoshino at mention of the name. Tsuma, small, broad nosed, cat eyed, said nothing.

"Oh, he's safe enough," Donn hastened to add. "However, I'll get gone just as soon as I learn about the arrangements I ordered made. Kindly tell me what has been done."

"What you ordered," said Hoshino, and then went into detail. "The closest river point to Sing-an is at the mouth of the Wang River; the town of Wang-kiang, twenty miles up this river, can be gained by the launch. This town is the base of General Chang, in charge of the operations against Yuan, and now investing Sing-an."

"What!" exclaimed Donn Curran, in surprise. "Sing-an is invested?"

"Yes, but will not soon be captured. The town can be entered. At Wang-kiang the men aboard the launch will put you in touch with one of Yuan's agents, who will take you the forty miles to Sing-an."

"Very well," said Curran. "Having got in, I must then get Yuan out, get him to the coast, put him aboard a ship. What about these arrangements?"

"They are in my charge," said Tsuma mildly. "A ship is waiting near Cape Yu-chow. You will make your way to Feng-yang. There, at the Inn of Ten Thousand Blessings, you will find my brother awaiting you."

"Eh?" Curran glanced at him sharply. "You mean we have to get through the mountains to Feng-yang? But I gave orders—"

"They were obeyed," and Tsuma showed white teeth in a smile. "Since I find you to be an American, if I guess right, every thing is very easy. Yuan's agent, who gets you into Sing-an, will get you out. Twenty miles from the city will be waiting mules and horses and all the baggage of an American botanist."

"Oh!" said Curran. "What's his name?"

The others grinned at him.

"I do not know your honorable name," said Tsuma, and Curran laughed with them.

"I see! You have the arrangements to make—the papers, passports, and so forth. Good. Make the name Donn Garfield—that's my middle name, and will do. Now, as I get it, the launch takes me to Wang-kiang and puts me in touch with Yuan's agent. He takes me into Sing-an and gets us out. You'll have everything in shape to take us to Feng-yang, where we pick up your brother and go on to the coast. Right?"

"Quite," said Hoshino, with the set smile of Japanese politeness.

At this moment a bell tinkled faintly. A coolie came into the room without speaking and handed Hoshino a dirty folded paper, and went out again. Hoshino inspected the paper, and looked up at Donn Curran, squinting. Something had happened; Curran could feel it in the man's suddenly tense manner, in his look, in his face. Tsuma could feel it too; the cat eyed, lithe little Jap rose and stood waiting, expectant.

"Well?" said Curran.

"General Chang is clever," said Hoshino.

"Undoubtedly," said Curran drily. "So is old pirate Yuan. What's happened?"

"Something which will stir the government. A foreign launch under the American flag has been seized by bandits, downriver, not so far from Wang-kiang. It occurred during the night. A telegram just reached the government here; this is a copy of it. An American and his daughter have been carried off, the crew of the launch killed…."

Curran started slightly. His steel eyes flashed a look that bit like a sword.

"Armstrong?" he demanded. Hoshino looked at him.

"You know him?"

"He was a friend of—of Jeffries Curran. An official in the company."

"Quite so—an important man," and Hoshino laughed quietly. "You see? It is the beginning of the end. He is taken by bandits, with his daughter. Yuan's men did it, or so it is announced by General Chang. The foreign ambassadors at Nanking will go wild, the Nationalist government will be foaming at the mouth. Then, suddenly, Chang announces that he has recovered the prisoners. He follows that news with the reduction of Sing-an. The head of old Yuan, sworn to by many who knew him, is sent to Nanking. General Chang is the conqueror, the new hero. You see?"

Curran, frowning, nodded slightly.

"Yes, naturally. And Yuan slips away. He's bribed General Chang, of course. That means I must make tracks, Hoshino."

"There is no time to lose," agreed Tsuma placidly. "I will take you to the launch and since it is under the Japanese flag, they will not touch it on the river. But I wish the man Curran did not know about you."

"What?" asked Donn Curran. "You do? Why?"

Tsuma shrugged.

"Ask Mr. Hoshino yonder. Me, I know very little. If we—"

A telephone bell sounded shrilly. Hoshino took down the receiver and listened for a moment, while Donn Curran frowned at the floor. He knew all about his brother, of course, yet surely not even Jeffries would betray him here—though there was probably a large reward on his head. Ten thousand taels the last he had heard. More now, of course.

Then Hoshino turned from the telephone jerkily.

"Go," he snapped, a new ring in his voice. "Police are on the way here—soldiers. They seek Ko-tsao, who is using the name of a respected foreign resident here, Mister Curran. Go, I tell you—go! There is still time!"

A snarl was fixed on his broad, pockmarked face. Curran was for a moment stunned. He knew only too well that this could have but one meaning. Jeffries had betrayed him, his own brother; deliberately handed him over to yellow men!

"By the lord!" he said, white with anger, as he rose. "Because I knew too much about his relations with Hsieu Chang…. All right, Tsuma. Let's go. Food aboard the launch?"

Tsuma merely nodded and held the curtain aside.

They strode forth together into the street. To a question, Tsuma said the launch was waiting at a slip below the match factory, a matter of three or four blocks, no more. Donn Curran walked along at his quick, swinging march step, with which Tsuma could scarce keep up except by trotting; the gray eyes in that brown, aquiline face was blazing.

So they came to the waterfront and a slip where a long launch rocked idly, two Japanese lolling on her foredeck. A panting word from Tsuma, and the two leaped up. One darted to the lines, the other to the engine. As Curran stepped aboard, the engine caught and began to roar. She moved suddenly, so that he was nearly overbalanced. His last sight of Tsuma showed the lithe little man smiling and waving to him.

Curran little dreamed how or where he would next see this man.

MORNING showed the muddy banks of the Wang River on either side; the launch was a fast one and carried a good store of petrol, enough to keep her going the entire day and night without pause.

Donn Curran got nowhere with the two Japanese aboard. They spoke only their own language, apparently, or else had orders to do no talking with him. Twice Nationalist patrol boats approached the launch, but seeing the Japanese flag and the white man aboard, they sheered off without halting her. Clearly enough, it was not yet known just how Curran had made his escape from Hankow.

Dawn merged into daylight as the launch sped up the muddy Wang, and in the full glory of sunrise sighted the town ahead upon a hill flank. Here lay the real start of Curran's perilous enterprise—and perilous enough it was. He had served in more than one Chinese army, and hundreds uncounted knew him by sight. One whisper that he was the dreaded Colonel Flea would ruin him; and there might be plenty to do the whispering, in this army ahead.

The town was a small one, but vastly increased in size by reason of being the base of supplies for General Chang. Out on the river were scores of craft of all kinds—ya-sau junks, Honan boats, all of the twenty one kinds of river craft and others to boot, moored in solid masses. Ammunition and supply dumps and a forfeited camp extended outside the town itself and along the hillsides, while a yellow road stretching up the valley was crowded with wagons and carts.

The launch drew in upon the mass of junks, threaded a devious way among them, and at last came to rest at what Curran took to be the customs landing. One of the two Japs caught up some papers and went ashore to meet the approaching officials; the other turned to Donn Curran and spoke in English, with a grin.

"You wait. Back quick."

He went ashore, joined his companion, and presently set forth alone into the town. He did not have far to go, obviously; even before the customs officers had gone through the papers and made a cursory examination of the launch, he came back into sight with a lanky white man following him. Curran examined this man with no little surprise. He was tall and gaunt, with a ragged red mustache and a shock of red hair; he slouched as he walked, his clothes were anything but clean, and a broken pith helmet was perched on his rusty thatch. He hurried toward the launch, beside which Curran was standing, and came up with outstretched hand.

"Glad you showed up," he said loudly. Then, under his breath, he added, "Done any talking with these birds?"

"Not a word," said Curran.

"Fine. Got your papers here. You're James Hollister, correspondent for the North China News, get it? Government permission to join Chang and look-see. Shut up and lemme talk. I'm Bill Harper."

Harper turned and engaged the officers in talk. One of the Japs set ashore a suitcase which Donn Curran had never seen before, touched his arm, and shook hands. Then the two little brown men shoved off their launch and departed. Evidently their task was finished.

After a moment Harper turned and joined Curran.

"All right, feller," he said, with a sweep of his faded blue eyes. "Let's beat it 'fore they think to ask more questions. That your bag? I'll have it sent up later on—this here is nip and tuck, get me? I got good hosses waiting, so mosey along."

Curran repressed a smile and followed Bill Harper up the street. Neither man spoke again until they turned in at the courtyard of an inn. At sight of Harper there was a swift movement. Two horses, ready saddled, were led out, and Harper swung up. Curran followed suit, asking no questions, and saw a native speaking quickly to Harper.

"Come along," said Harper to him. "This here is tight work. Damn the telegraph!"

Obviously, word had reached Wang-kiang to be on the lookout for Colonel Ko-tsao, and it threatened to disrupt the plans of Bill Harper—if the latter were really Yuan's agent. Curran was not particularly surprised, for he knew there were a good many white men, and quite a few Americans, filling all sorts of queer positions in the new China.

Harper, silent now, led the way into the street and so out of town. They passed the gates without question, got through the camp beyond by dint of Harper's papers, and in another ten minutes were heading out on the long yellow road that led to the mountains in the north. Then Harper drew rein, grinned widely, and began to roll a cigarette.

"My gosh, I was scared!" he observed. "Thought they'd grab you sure. So you're the Colonel Flea I've heard tell about, huh? You don't look it."

"Same to you," and Curran chuckled. "That is, if you're Yuan's agent."

"Hell, I'm a lot o' things," said Harper genially. "I run Yuan's machine guns, drilled his sojers, laid out some of his defense lines, and so forth. Been running that durned mine for him the last year. None of this gang would know me, so I played safe in coming along to meet you. Besides, I'm the only one that can blow up a train if we have to, so I'm here."

"Why blow up a train?" asked Curran, lighting a smoke. The horses were started onward.

"Diversion," said Harper. "We got to work around to reach Sing-an, get me? That means we got to go across the railroad line—there's a branch feeder comes up west of here and Gen'ral Chang keeps it patrolled and runs troop trains over it. He's cut off Yuan from the westward, that way. We got to get in by the back door. And feller, we got to make time on this here road. That's why the hosses. I got mules and baggage waiting farther on—pick 'em up sometime tonight. We got to kill these here hosses if we have to."

"You won't kill 'em right now," and Curran eyed the road ahead, crowded as far as eye could see with men and wagons.

"Nope, we take a branch road after two mile further," said Bill Harper. "Better cut down on the talk—you can't never tell about these here birds. Some talk English."

Curran nodded, delighted with his companion. Harper was a man after his own heart—reckless, efficient, able to turn his hand to anything, and careless of odds. It was fully as mad for Harper to show himself here as it was for Colonel Flea to try to reach Yuan.

THE two men rode onward, passing files of men and lumbering wagons; General Chang had just received new supplies and reinforcements, it appeared, and was moving them up to the front. Curran noted that his own saddle and that of Harper carried large bags, which were apparently well stuffed. Food, therefore, was taken care of.

"My gosh!" said Harper, as a file of troops held them up momentarily. "From all I've heard about Colonel Flea, I thought he was a hairy pirate with bells on! Can you run an airplane?"

"Some," said Curran, smiling. "Got any?"

"Not a smidgeon," said Harper, "Chang's layin' around the outside forts tryin' not to lose men. He's got a couple airplanes but they ain't much good. Yuan—say, that old devil sure is cute! He's got Chang's goat, believe me, and got it from the air, too! You'll see when we get there."

"May not have time," said Curran. "From what I gather, Chang's aiming to pull his big stuff and send in the head of Yuan pretty quick."

Harper gave him a slow look.

"Say, you ain't so doggoned backward, feller; How come you figured that out?"

"Know about the Armstrongs being captured?"

Harper shook his head, and Curran detailed the matter. Then, with a sheepish grin, Bill Harper said he did know all about it—had wanted to see how much Curran knew. He had heard about it in Wang-kiang. The British captain and all the crew of the launch had been killed, Armstrong and his daughter being carried off.

"It was cute, too," he added. "Chang's men done it, of course. I heard tell they made a mistake and bunged up old Armstrong pretty bad—maybe killed him. They're keepin' 'em at a hill temple until Yuan clears out of Sing-an, then they take 'em on into the city. Armstrong and the girl think Yuan's got 'em all the time, get me? Then Chang, he makes a great stage play, jail delivery and so forth—maybe they'll be found in an outlying fort, I dunno. He sends word to Hankow they're safe, or the girl anyhow, which is all that matters, and then Hankow hears he's captured Sing-an, then they get old Yuan's head. Yuan's got a feller in jail now, looks just like himself to provide the head."

Curran nodded.

"Figured it that way," he said laconically.

However, his brain was busy if his tongue was not. Harper he figured as a genial sort of scoundrel, ready to cut a throat or save a life and call it all in the day's work; a man with no scruples, with a certain personal code of alleged ethics, who had probably salted away enough hard cash to get out of China with and enjoy life. About the only thing that would appeal to Bill Harper would be expediency—the outlook for Number One.

"You got the getaway arranged?" asked Harper, when they were again forced to a walk.

"All set," replied Curran. "You're to take me twenty miles from Sing-an—know where?"

"Sure," said Harper. "A temple. What'll I find there?"

"Everything necessary," said Curran cautiously. "Where's Armstrong being held?"

"A little hill temple about a mile off our route," said Harper, with a shrug.

"We're going there."

"Huh?" Harper swung an astonished look to him. "The hell we are!"

"Yeah. We are," said Curran, and smiled. Harper smothered an oath in his red mustache.

"Listen," he said. "Forget this rescue stuff, get me? There's an officer and six men at that there temple guarding 'em. Armstrong's prob'ly dead, from what I heard tell. We can't take 'em back to safety anyhow."

"We'll take 'em to Sing-an," said Curran amiably.

"Like hell! Yuan doesn't want 'em. It's Chang's game. If we get 'em away, Chang will attack in earnest and raise hell. We don't want any real war, doggone it!"

"You won't get it," said Curran. "Listen, now; pin your ears back. It's gone out that Yuan's men turned the trick. Yuan gets the blame. The foreign consulates are shrieking to heaven. If Yuan gets safe away, Japan doesn't dare shelter him, savvy? I'm here to earn my money, and I don't propose to let a pack of fools lose it for me, Bill. Yuan's got to get away with Eleanor Armstrong and her father, if he's alive; he'll need their testimony to prove they were rescued by us and taken to him, that Chang had raided their launch, and that he got 'em away safe in spite of Chang's army. That'll show up Chang to beat the band, and Yuan is safe, and so is my pay. Otherwise, not."

"Huh!" said Bill Harper, and chewed at his red mustache thoughtfully. "Feller, you've said something. I'll think it over."

Harper proceeded to think it over until they had reached the branch road. Then he struck up a good pace, and the two horses went forward at a brisk clip, heading for the hills. Curran figured they must have covered a good five miles, before Harper broke silence.

"Listen," he said, pulling up and rolling a cigarette from vile black native tobacco. "Looks to me like you're dead right, Colonel. This here hill temple where I heard tell the Armstrongs are being kept, is about twenty mile from here. We'd ought to get there late this afternoon. What you aim to do when we get there?"

"Shoot up the guard, to make the Armstrongs understand we aren't pulling any bluff," said Curran. "You should have a gun for me."

"Got two for you," returned Bill Harper. "In them saddle-bags of yours. Automatics. All right. We shoot up them Chinks and light out with the Armstrongs. Lord help us if that girl's a softie who can't travel! But when we get to Yuan, feller, you got to do the talking. It ain't healthy for me nor nobody else to talk turkey to old Yuan—my gosh, he got two messages from Chang, didn't like their talk, and had 'em impaled right off!"

"Yuan isn't fighting with me, not while I'm running his getaway," said Curran grimly. "Can you write Chinese?"

"Sure," said Harper, with surprising nonchalance. "Was born and grew up here. Went back home three-four years, didn't like it, and come back. I been knocking around China thirty years, feller. Huh, I ought to write Chinese! Why?"

Donn Curran chuckled. "Tell you later."

"All right. But this here excursion is going to delay us a lot, Colonel. It means travel all night, blow up a bridge to check the railroad patrols, and keep going until after sunrise—and then not slow up until we get to where an escort's waiting, tomorrow noon."

"Suits me," said Curran. "All this about escorts and so forth strikes me as pretty soft, Bill. I'm not used to so much ceremony. Say, how's Yuan fixed in case of a real fight?"

"He ain't fixed," returned Harper. "That's why I wasn't so doggoned anxious to have Chang get riled up. Ca'tridges is low; got some ammunition for the machine-guns, and I been fixing up hand grenades. Food supply O.K. We got three thousand fine drilled troops, and they can hold them hill forts outside Sing-an against fifty thousand. Chang wants them fellers in his army."

"Chang gets the gold mine when Yuan skips?"

"I expect so," said Harper gloomily. "Yuan says I can stay and work it for Chang, but not me. I got more sense than that. Well, let's be moving!"

They moved, accordingly.

THERE was a little pagoda in the hills, a shrine to some local saint erected long ago and now forgotten of gods and men alike, long since looted, the interior swept bare. Here Eleanor Armstrong and her father were brought by the ragged bandits who had herded them up from the river. Armstrong was packed aboard a mule, dying; he never recovered consciousness, and was dead a few hours later.

The girl, beside his covered-over body, faced the second day of imprisonment here, bravely enough. The shock had been acute, but the future threatened to dwarf the past. She had seen the steam launch boarded, had seen the yellow men shot down, had seen the British captain sell his life dearly, had seen her father shot. Now she was here in the hill temple, her father dead, all hope destroyed, and a grinning yellow man telling her what a pretty Number One wife she would make him when they got to Sing-an.

Being what she was, Eleanor Armstrong reacted to it all with quiet bravery, put away the past, looked the present and the future in the eye without shrinking. She had won medals at tennis, cups at golf; she was twenty-four, and cool headed. Nothing masculine about her; from the brownish, sun-glinting masses of hair on her head, to her buckskin shod feet, she was entirely feminine, as many a man had found to his sorrow. However, she was not the sort to lose her head. The same quality that had won her sports trophies, now held her chin high when everything seemed lost, when she was alone, crushed, friendless.

She did not know the name of the wiry little Chinese who commanded the bandits camped just outside the pagoda entrance. He was a Honan man, small, active, girt with two Brownings, his right cheek scarred. He spoke to the other men with the voice of authority, and they obeyed him sharply enough; but when he came inside the entrance and squatted down and grinned, his voice was soft and she was doubly afraid of him. Especially now, this second day.

"Missee, plenty quick you mally my," he said with a confident air. "S'pose we come along Sing-an, my got plenty face along Yuan. My think so tomorrow, maybe. My got plenty big house Sing-an. My puttee poor clothes now, maybe tomollow velly fine clothes, soldier clothes. You savvy."

Yes, Nell Armstrong savvied well enough, though she could not speak a word of pidgin English. He had told her all this before. He was an officer of the bandit Yuan, and when they got to Sing-an he would put on his uniform and take her to his fine house and marry her. She looked at him and smiled.

"Nothing doing," she said firmly. "I know well enough that soldiers are hunting you all over, and you're hiding away here. You'll never get to Sing-an, wherever that is—and you'll never marry me, you yellow toad!"

The other grinned again, refusing to get angry.

"You see," he said, with horrifying confidence. "You mally my plenty quick, number one wife! All same plenty foreign girl, belong plenty China boy."

Noon came, and fresh arrivals. Nell Armstrong looked out, and saw more ragged bandits, talking with her captor and laughing. She had learned to fear the laughter of the Chinese by this time; there was something cruel about it, something that bit under the skin. She wondered what this arrival boded, and learned soon enough.

The newcomers were here to take away her father's body. Why, she could not know or guess.

And they had their way, in the end. Nell Armstrong fought them, when the entreaties had no effect—fought them with her bare hands, struck them away, angered them until four of them leaped at her and brought her down and tied her savagely despite all her struggles. Even then she did not lose her head, but lay there panting until tears came to her relief.

When, after a time, the others departed with her father's body and her captor crept inside again and grinned at her, she met his look with cool, dry eyes.

"Tonight, maybe, we go along Sing-an," he said, and gestured to mules tethered on the terrace outside the pagoda. "Maybe stop some more."

"What have you done with—with my father's body?" she demanded. He only grinned and drew out a long, sharp knife, testing the edge delicately.

"No savvy," he returned, and leaned forward, and cut her cords so that she could sit up and rub her hurt wrists. "You eat now."

He had food and tea brought in. Nell Armstrong forced herself to eat, choked down the food—not that she wanted it, but her body would need it this night. For if possible, she meant to escape. Better be shot down in the effort, than submit tamely to what was promised by this grinning yellow ape. There had not even been a mention of any ransom.

She could not know that even now her father's body was being carried back to Hankow as an indication of the sharp action taken by General Chang against the rebels.

The meal over, she curled up in her ragged blanket and feigned sleep, so they would leave her alone. The afternoon was advancing, and presently, worn out by all she had been through, she did fall asleep, passing into a sound and deep slumber. From this she was wakened by a yell—so utterly a yell of fear and dismay that it brought her to the pagoda entrance, staring.

Outside was a broad terrace, paved in ancient years and bordered by brush which partly concealed the pagoda itself from view of anyone on the hill path below. The main road was something over a mile away, she knew. Her guards had been camped on this terrace, which was watered by a spring that dropped down the hillside. As the weather was damp, they had been clustered about a fire, apparently without regard for the telltale smoke it caused; their arms and the mules were at the other end of the paved terrace.

One of the bandits, evidently posted on guard outside the brush, appeared yelling something; there was the smashing report of a shot, and he fell in a limp mass. The little commander cracked out orders. The men sprang up, started for their piled rifles. Then, breaking through the brush, appeared a white man.

NO doubt of it. Nell Armstrong gasped at sight of him, stood petrified. He appeared there calmly, coolly, an automatic pistol in his hand; a man with incisive features, gray eyes that blazed, a voice that issued a curt order in Chinese. Then the bandits broke into action, their commander whipped out a pistol and fired.

The white man's weapon spoke, spoke again in sharp bursts of sound. The bandit leader whirled around and pitched forward. A shrill yell of dismay broke from his men—another white man had appeared at the other end of the terrace. Pistols sent volleying echoes up the hillside, the hollow pagoda reverberating to the sound. Nell Armstrong stood there, wide eyed, watching as the ragged bandits tried to fight and were shot down. One of them alone remained on his feet, hands outstretched, begging for mercy.

The first white man looked up, caught sight of the girl standing there, and strode toward her. He removed his helmet with a smile, and she wondered how the smile could so change the eagle lines of his face.

"Miss Armstrong?" he said. "Glad we found you all right…."

She gave way there and fainted. Her first sign of weakness—but this was pure reaction.

When she opened her eyes, she was outside, sitting near the spring, her face wet with water. The bodies of the bandits had disappeared; the one remaining bandit sat at one side in an attitude of fatalistic resignation. Close by sat the two white men, drinking tea. The second one, with reddish hair and a straggly red mustache, was handling brush and ink slab, writing on a strip of paper. The first man was speaking. Though his back was turned, Nell Armstrong noted his even, unhurried voice, his crisp brown hair, his trim head line.

"Address this to General Chang, and get it right, Bill," he was saying. "I've been too busy to learn to write—all I can do is to sign Colonel Ko-tsao, so leave me room for the scrawl. Tell him that I'm going to Sing-an and am taking Miss Armstrong with me, and if he kicks up any didoes about it, I'll blow the Yellow Carp mines higher than a kite. Tell him to be a good boy and play the game, or else his deal with Yuan will be made public and he'll be out of a job. We'll let this coolie take the message home."

"That'll raise hell with our program, then," objected Bill Harper.

"Leave it to me," was the response. "I'm running this show. Get your hen tracks down and let me sign."

He turned to the hapless prisoner and spoke rapidly. The bandit made sullen, resigned answer, then glanced at the girl. Curran caught the glance, turned, and came to his feet, holding out his hand to her.

"Hello!" he exclaimed genially, and flung a word over his shoulder. "Watch that beggar, Bill. So you've come around, Miss Armstrong? Fine. Let me introduce the rescue party. I'm Donn Curran—I think you've met my brother Jeff, in Hankow?"

"Eh? Jeffries Curran—yes, certainly," she murmured, a little dazedly. "I didn't know he had a brother."

"Oh, Jeff doesn't mention me in society," and Donn Curran chuckled. "This is Bill Harper, my guide, assistant, philosopher and secretary. Sorry we couldn't get here a bit sooner; but we did our best. Your father…."

She winced, as she came to her feet.

"Father died yesterday," she said simply. "This morning they came and…."

Curran raised his hand. "Yes, we've got the whole story out of this rascal. They're taking his body to Hankow now, with word of how General Chang recovered it from the bandits. These fellows, by the way, weren't bandits at all, but some of Chang's bodyguard, his best men. You can see their uniforms laid out over there."

Nell Armstrong blinked. She did see the uniforms, freshly unpacked and laid out near the mules, but she could not credit what she heard.

"I—there must be some mistake," she faltered, a frown creasing her forehead. "Their leader is one of the bandit Yuan's officers. He was taking me to Sing-an…."

Bill Harper grinned, and Curran broke into quick laughter, unassumed.

"He lied, Miss Armstrong. Bill, here, is old Yuan's chief cook and bottle-washer, and I'm about the same, only more so. Chang rigged up the whole thing. He was trying to stir up the foreign consulates against Yuan, and get himself a lot of credit. The idea was to take you along, and rescue you after a couple of days. You'd get it quick enough if you understood Chinese; this rascal here has coughed up all he knew."

Nell Armstrong put her hand to her eyes.

"Oh!" she said softly. "If—if that's true—it was cruel—"

"Cruel?" Curran looked at her. "My dear woman, China is cruel—haven't you discovered that yet? Sit down and take it easy. We've a bit of work to do."

She obeyed, trying to readjust herself. Bill Harper extended the paper and brush to Curran.

"Sign up, colonel," he said. "But lemme tell you, feller, we ain't going to take Sing-an without a scrap. These here extry mules will just about save our necks. Miss Armstrong, can you ride? We got to travel hard, and we got to keep going all night and then some."

"I—of course," returned the girl. "And I haven't thanked you—I forgot about it."

"Don't mention it," said Curran, having signed the paper. "Bill, take a mule-halter and tie this bird's ankles good and hard. He can't pick 'em loose for an hour or two, and that'll be start enough. Don't leave him a knife, mind, or chopsticks, and make plenty of knots to keep him amused. Tell him to take this letter to General Chang."

WHILE Bill Harper was attending to these details, Curran turned to the girl, studied her with one sharp glance, and offered a cigarette. He lighted one for himself.

"Here's the story," he said. "We're breaking through the lines to reach Yuan. We can't take you back to Hankow—the river isn't safe for us, and neither is the country. Our only safety lies ahead. It means hard riding, probable fighting, long chances. Are you equal to it or not?"

"Quite, if it's necessary," she rejoined quietly, and as he met her eyes, Curran nodded a little.

"That's not all," he said. "Going back is impossible. I'm taking Yuan out to the coast and safety. I'll take you along. We can't go back to Hankow. If General Chang or his men got their hands on you, they'd murder you in a moment—to stop your mouth. You know too much. If you'll trust to us, we'll pull you through; or else we'll go the same road you go. Yes or no?"

"Yes, of course," she rejoined, her eyes steady on his face. "Tell me who you are, please. I haven't met you before, Mister Curran?"

"Hardly," and Donn Curran smiled, his gray eyes dancing in the afternoon sunlight. "I'm a black sheep, an adventurer, what they call a soldier of fortune, a good-for-nothing rascal—"

"You're a liar!" spoke out Bill Harper, pausing in his work. "Miss, he's a real soldier, that's what he is! He's been running airplane squadrons, he's got a colonel's commission, he could be a general if he wasn't straight and honest—"

"Shut up," snapped Curran, an edge to his voice. "Now, Miss Armstrong, balance up. You must trust us, obey orders, take what comes. All we can promise is that we'll do our best."

She held out her hand, and a smile broke on her lips.

"Of course!" she said. "I—why, I'd trust you if you were Colonel Flea himself!"

Curran froze a little.

"Colonel Flea?" he said. "What do you mean?"

"Oh, haven't you heard of him?" she exclaimed. "We heard a lot about him, different places. He's a bandit, a soldier of fortune of the worst kind. He's killed hundreds of poor Chinese, robbed banks and armies…. It's some funny Chinese word that means flea. I supposed you'd heard of him."

"Ko-tsao is the word," said Curran. "Yes, Miss Armstrong, I've heard of him. I happen to be Colonel Flea in person. It's the name applied to me by the Chinese."

She read the serious look of his eyes, caught the truth in his voice, and paled.

NIGHT, the stars obscured by high clouds that promised rain later, a steady driving wind out of the north. The hill roads were bitter cold.

Curran and Nell Armstrong rode in the lead, Bill Harper following with the three baggage animals. They had picked up Harper's waiting mules after dark, discarding the horses in their favor; the mules were surer footed on the hill trail and were fresh. The three baggage mules were heavily laden but kept the pace well enough. It was past midnight; hour after hour they had ridden along in silence, except for brief directions from Harper when there was any doubt about the trail.

There was nothing very happy about Donn Curran's silence. He had been most poignantly impressed by the character and beauty of Nell Armstrong; even at the revelation of his identity, she had asked no questions, had continued to take him for granted, on trust. And in the hours following she had never once asked for any explanation of the bloody repute of Colonel Flea, but the three of them had swiftly grown close in a comradely friendship.

And this was the girl engaged to marry Jeffries! He writhed at the thought. Jeffries, who had betrayed a Red Cross food train, who had betrayed starving peasants upcountry, for the sake of gain! Jeffries, who through the years had ever been a sneak and a crafty plausible rascal! Jeffries, who had now capped his sly career by attempting to hand over his own brother to death, without a qualm—nay, upon a handshake! Donn Curran wondered what this straight eyed girl would say if she learned of that business in Hankow, and smiled to himself at the thought. Not that he would ever tell her. If she was fool enough to marry Jeff, that was her affair.

Several times, Curran had caught sounds down or across the wind, sounds which indicated that they were not so distant from the field of action. Two or three times, the heavy shaking burst of a shell or bomb, although there was no gun fire. Once, too, the stuttering chatter of machine-guns.

Soon Bill Harper swung to earth, "Colonel, let's you and me unload, make some observations, and take a pasear. Railroad we're due to blow up is just above us. Miss Armstrong, you set here and keep them mules from strayin'. Here's a pistol—shoot of anything happens, but make sure it happens 'fore you shoot. There's patrols within a quarter mile of us, and only the wind keeps us from being in a right ticklish spot; but they can't hear much in this wind."

Curran joined Harper, helping him tug free one of the loads from a mule.

"If we can slip through," he said quietly, "why do any blowing up?"

"Can't slip, Colonel," rejoined Harper. "We got to go right through a patrol camp in the pass up above. About three hundred yards to our right is a bridge, savvy? Across that bridge is the central camp of their patrols. If we blow the bridge we cut 'em off from following us—"

"And also alarm the camp in the pass," said Curran sharply.

"Sure. What d'you expect? It ain't all candy," was the cool response. "They run several patrol trains every night, with armed parties in between, and we might be lucky enough to catch us a train and raise hell. We ain't bothered this line none whatever—I figured on using it just such a time as this, when we need it most. Don't throw that there pack around too promiscuous; I got the detonators and gelatine in there."

Curran grunted and lowered the pack to the ground very gently. Bill Harper rigged up blankets on the surrounding brush, got out an alcohol stove and a ten outfit, and told Nell Armstrong to occupy her time until their return by making tea and getting a snack ready. Harper had it nearly ready while he was talking.

"All right, let's go," he said. "There's a pack for you. Tote it gentle."

"Back soon," said Curran to the girl, and her soft "Good luck!" floated after them as they went up the trail afoot and were enclosed by darkness. The rifle and ammunition, taken from the party of imitation bandits, were left with the mules.

Curran was astonished indeed, when, before they had climbed a hundred feet, the level line of the railroad appeared vaguely to right and left. Harper turned at once to the right, and they followed the track. Everything close at hand was swallowed up in the darkness; but a cluster of lights showed ahead, perhaps half a mile distant. At length Harper halted and pointed to these lights.

"There's the patrol base—other side the bridge. You can't see it now, but there's a powerful deep gorge right here, Colonel. It widens out, and splits these here hills wide apart. We got to go up and around it, get me? From here to the first fort where Chang's army is held up, ain't only three mile in a straight line; you could see it plain if we had daylight. But we got to go twenty mile around, get me? They'll be after us, too. The most we can do is to cut off that patrol base so's the gang of 'em can't trail us."

"Right," said Curran. "This looks like your party, so give your orders."

HARPER was nothing loath, and set to work emptying the packs. He had thirty pounds of gelatine, insulated wire, magneto and switch and all else necessary. The plugs of gelatine were removed from their paper coverings and the jelly-like mass was flung together and wrapped in a sack provided for the purpose; owing to the cold, it could not be kneaded up, but Harper professed himself satisfied as to results.

"I got thirty foot of wire," he said, "so I'll go lay the charge out on the bridge. Listen, Colonel! You keep an eye out for track-walkin' patrols coming from either way. You can tell 'em by electric torch flashes. Chang, he keeps 'em at work on the line—he's always been scared we'd blow it up. If you see anything, tap on the rail with your gun, get me? Three taps, repeated until I answer."

"Right," said Curran.

"When I get her laid, I'll tap on the rail for you to help me spread this doggoned stiff wire. By gosh, we'll be rid o' one pack-mule anyhow from here on! So long."

Harper departed with his load, and Curran swore softly to himself as he stood eyeing the blackness to right and left. Thirty feet of wire—why, it was sheer madness! That charge would blow the life out of anything within that distance; surely Harper did not mean to set off the gelatinite himself?

Nothing happened. The cold wind poured down from the peaks above.

Suddenly, across the bridge, Curran described the flashing of an electric torch. He stooped, gave the agreed signal, had an answer at once, and then hastily caught up the packs and got everything out of sight amid the brush below the tracks. A moment later, Bill Harper came along and joined him in this shelter.

"My gosh, feller, it's colder'n hell out there!" complained Harper. "Yep, search party comin'—hope it means a train's comin' after 'em! Everything's jake. In five minutes I can have the exploder ready—lay low, now!"

A party of a dozen men was coming along the bridge. Their track searching was a joke; they used the electric torch merely to light their way, and smoked and talked as they came. Curran, listening, found that a train would follow them in twenty minutes. Bill Harper caught the fact also, and nudged him delightedly. The patrol came to the bridge-head and passed above the two hidden men, and were swallowed up by the night.

"Fine!" said Harper. "You go get the lady and the mules. Fetch 'em up here and wait for me. I'll whistle when I have the jigger fixed and come in."

"Hold on," and Curran caught his arm. "You're not fool enough to explode that charge at thirty feet!"

"Not me," said Harper, and chuckled. "Train does it. When the drivers go over my outfit, the connection's made and there's hell to pay thirty foot back—about the first coach. This line mostly carriers supplies, so don't shed any tears over dead Chinks."

"No danger."

Curran retraced his steps to where Nell Armstrong was waiting—no easy task in the pitch blackness. He swallowed some warm tea, while she carried the pot and some food for Harper; then Curran, casting adrift the spare mule, got the others up the slope to the tracks. The blankets and alcohol stove were here put away, and before this was finished Bill Harper's whistle was heard.

"My gosh—you saved some tea for me?" he exclaimed, on joining them. "Miss, you're a blessed angel. And some grub—glory be! Didn't know I was so cold. All set, folks. We can get on our way. Miss, you come with the pack mules. Let me and the colonel go ahead. We got to stop pretty quick and wait for the blow-off."

Stop they did, after some progress along a steeply mounting path—a road, in effect, which traversed a deep gorge ahead. Suddenly Harper ordered a halt.

"There she is," he exclaimed. "Now we'll see if she works! If she does, remember one thing—break 'em when we hit 'em, and yell, 'Kill! Kill!' so they'll think we're a bunch of soldiers. Got a gun, Miss? Then use it, in the air or anywhere. Make noise."

These rapid instructions fell into silence. All three of them were staring back at the headlight of a train, puffing and rattling out along the bridge. The yellow flare lighted the track dimly. Probably no one was watching—

A red flare that split the sky, a rending roar, and then an instant of terrible silence. The exploder had worked.

"Move sharp, everybody!" snapped the voice of Bill Harper.

They swept the mules into speed, hammered them up the sharp slope. Behind, screams and cries, shots, tumults and pandemonium; ahead, bursting lights, quick yells, figures of men passing the fires of a post. From somewhere a rocket soared up, broke, revealed a score of soldiers and their camp in the middle of the road ahead—then all were gone. Curran's pistol poured bullets at the spot.

Shots answered, rifles cracking; abruptly, Curran found himself among yelling Chinese, and heard Harper's pistol hammering out at his stirrup. That of Nell Armstrong took up the refrain. A rifle seared Curran's breast, and he pistoled the soldier with his last shot. His other automatic was in his pocket—he reached for it, felt a tremendous shock, and found himself sprawling in the road amid writhing, yelling men.

Curran lay quiet, got out his pistol, found himself unhurt. Harper and the girl and the mules had swept over and past, unknowing. Chinese voices were shrilling out all around, men were running, wounded were screaming. Curran did not move. His mule had been shot from under him, probably by a wild bullet.

"To the railroad, sons of turtles!" shrieked a furious officer. "Up! Run! Shoot!"

Those who could, ran. Those who had rifles, shot at the night sky. Somewhere close in the rear burst out a terrible and deadly hammer-fire—two machine rifles, thought Curran in surprise. He had not known these Chinese had such arms. A fresh shrieking and banging of rifles resounded.

CURRAN did not know what was going on, but rose and broke into a run, pistol in hand. Bill Harper would wait when they discovered him missing. Another rocket soared in, and he cursed its rising at such an instant—it burst to show him empty road ahead, high rocky walls on either hand, no retreat or evasion. And no sign of Bill Harper.

K"o-tsao!"

The yell pierced to him from behind, as the light died away. It came again and again—shrill, quick cries. Had someone recognized him? Curran, running, suddenly caught the rattle of hooves catching up with him. More than one animal—then, he was caught!

"Ko-tsao!" Again the piercing cry, a wild and exultant note in the voice. Curran snarled and came to a halt. If they had him, all right—and now another rocket went roaring up into the black heavens, and he discerned two riders bearing down on him. His pistol went up, as the drifting light broke across the sky.

"Don't shoot, Ko-tsao!" cried the foremost rider, with a wild laugh. "Don't shoot!"

Just in time. In that whitish glare, Curran recognized the rider, and jerked his weapon aside. Tsuma—the Jap agent! Here, at this instant, of all times and places! Tsuma, reining in, leaped to the ground beside Curran, caught the latter's arm.

"Quickly! Take my mule!" he cried. "No time to waste. My men are holding them. I was bringing you a present—now I go back and join my men. Quick!"

Curran looked at the other mule, upon which a swathed and immobile figure sat.

"Who's this?" he asked sharply. Again that wild, exultant laugh from Tsuma.

"My present. The reins are fastened to my saddle. Mount and ride, Ko-tsao! They will be pursuing quickly—I must rejoin my men."

Very good. Curran was no fool, to stand here asking bootless questions at a moment of stark crisis. He swung up into the saddle, felt the tug of the led mule as his mount started, and behind him Tsuma died into the blackness and was gone. There was a long rein to the second mule; the two animals strained into as quick a pace as the uphill path would permit.

"Hey, Colonel! That you?" came a voice from ahead and above.

"All right, Bill," rejoined Curran. "All O.K. there?"

"Yep. Move along. What held you up?"

Curran did not answer.

The hooves rattled sharply as the six mules went clattering up the gorge, and the tumult behind died away and was drowned in the reverberant echoes of their passing from the rocky walls on either hand. Curran was up with Nell Armstrong now, passed her, and gained place beside Bill Harper.

"Got a match?" inquired the latter.

Curran laughed, found a box of vestas, and passed them over. Harper lighted a cigarette as he rode, the wax vesta holding the flame even in the wind of the gorge. Then he held up the light, and a quick word broke from him.

"What's this you got, Colonel?"

"Don't know." Curran turned, but the vesta had flickered out. "That Jap, Tsuma, showed up. I was knocked off my mule. Said this was a present he'd fetched along for me. He had some men out there in the mixup. This is probably a prisoner."

Bill Harper swore admiringly.

"That there Jap is some pumpkins, colonel," he observed. "Smart as a new whip, he is! Better have a look at what we got. Might be some worth while Chink, at that. Slow up a minute—I guess we're ahead of trouble anyhow."

Harper struck another match as they halted, held it aloft. A slow whistle broke from him. Nell Armstrong uttered a sharp cry of amazement. Donn Curran said nothing, but stared incredulously at the gagged and bound figure on the led mule.

It was that of a white man. It was, in fact, that of Jeffries Curran.

THE little hill city of Sing-an was a place of no commercial importance, far from any trade route; yet, through hundreds of years, it had been a name renowned in the annals of the Manchu and Ming dynasties. For, from a secret place in the near-by hills, had come an unending flood of virgin gold to enrich the treasury of the Palace of Heaven.

The city was by no means invulnerable to modern heavy artillery, for hill crests lay around it; but to anything less, it was impregnable indeed. It occupied a round hill, and was girt about with massive walls furnished with ancient but still formidable cannon whose brazen mouths could sweep every approach with storms of grape. Within a radius of ten miles outside these walls were forts, small but well placed; rumor said that a French engineer had emplaced them for the Emperor K'ang-hi.

The old bandit Yuan had not been slow to improve matters during his occupancy. The city walls were dotted with machine-guns—most of his army, indeed, was devoted to this one branch. The outlying forts had been well armed and put in good shape, so that the tide of conquest had swept up from the Yangtze time and time again, each time a little closer to the city, yet each time broken by force or by raw gold. Half the outlying forts were gone now, in the hands of General Chang, and the city was cut off to the south and north and west; it could not be quite cut off from the east, owing to the rough hills and the few remaining forts, but there was nothing to the east except wild mountain country. One really determined push, with some good artillery work, would reduce the little city in short order.

Yuan, the crafty, knew it well. General Chang knew it also. The only trouble was that in such an event, the Yellow Carp mines would be blown up and lost forever. Which, in the sight of worthy General Chang, would be a pity. Much simpler all around if Yuan were to quietly decamp and turn over everything to General Chang—including an old man in a bamboo cage whose features were surprisingly like those of Yuan the crafty.

Bill Harper and Donn Curran, preceded by the cavalry escort they had encountered, rode in at the auspicious southern gate of Sing-an early in the afternoon. Behind them rode Nell Armstrong and Jeffries Curran.

From the moment he had cut the prisoner's bonds, Donn Curran had not spoken a single word to his brother; he had preserved a silence cold and implacable as death, but under the sword bite of his gray eyes, terror had stirred in the face of Jeffries. The latter had faltered out some fragments of a kidnaping story, but had done the rest of his talking to Nell Armstrong. To Harper's discreet questions, Donn Curran had returned no answer. He had scarcely spoken all this day. Now, as they came in at the city gate, he turned to Bill Harper. His features were drawn, thin, and his eyes brooked no contradiction.

"Bill," he said, "that man is my brother. I must see Yuan, then sleep for a couple of hours. Have him placed under guard, but quietly. Don't let her know about it. I'll settle things after a bit of sleep, when I can think more clearly."

"Leave it to me," said Harper curtly.

"When do we make our getaway with Yuan?'

"As soon as we can start. The quicker the better."

"Midnight, if that suits you."

"Right. Put it up to the old boy."

Donn Curran nodded.

"Any trouble getting out to where we meet the escort?"

"No; I'll have a report on things tonight, Colonel, but there should be no trouble. Only one danger point. We can risk that."

They went on. Bill Harper beckoned an officer and gave him instructions. All the way along the narrow, crooked streets, Donn Curran never once looked around at his brother and Nell Armstrong. When they came to the yamen of the former imperial governor, now occupied as a palace by Yuan, he went in past the guards with Harper. Dismounting in the courtyard, he perceived that the two of them were alone. Jeffries and the girl had disappeared. He asked no questions.

YUAN received his visitors in the hall of honor, for he was a crafty man. He was seated on the central dais; guards were stationed at either end of the hall, but they were beyond earshot, and words could safely pass here that might not dare find utterance in a small and private room.

The master of Sing-an was a tall, spare man of fifty-odd, but his gray beard and mustache made him seem much older. His heavy lidded eyes looked sleepy, but no taint of opium clung to him; looking sleepy was one of his chief assets. He wore a mandarin's cap and a very handsome outer robe of gold brocade. To the experienced eyes of Curran there was much strength and craft in his features, with the usual Chinese disregard for others—called by some cruelty, by others selfishness. He lifted his hands as the two men approached.

"You are welcome," he said quietly, his eyes on Curran. "You are he of whom I have heard, Ko-tsao?"

"That is my unworthy name," said Curran, with ironical amusement employing the old Chinese forms of speech. "It is not fit to be uttered by the lips of the old Maternal Uncle, the Father and Mother of the people! To me, his compassion is as the springtime rain unto a half dead tree…."

Bill Harper grunted. A shadowy smile appeared on the lips of Yuan, who interrupted the polite phrases.

"Enough. You are hungry and weary; I am impatient. What has ceremony to do with an old man who fed himself by making kites for the sport of others? Come and sit down beside me, light a cigarette, and talk. First, Ko-tsao, you had better prove to me just who you are and why you are here."

Curran thankfully dropped on a cushion, lighted a cigarette, and gave Yuan the message confided to him verbally by the bank, mentioning the amounts credited Yuan and certain details which perfectly established his identity.

"Good," said Yuan. "I welcome you. Why do you bring another white man and a white woman with you?"

"The white man is my brother," said Curran. "He betrayed me to Hsieu at Hankow after I had escaped. When I have slept I will arrange matters with him. As for the woman, let Bill Harper tell you the details."

Bill was nothing loath, and when Yuan heard of General Chang's pretty little scheme to smash him after his departure, there flitted across his face a grimace which revealed more of his thoughts than any words could have done. Then, as Harper repeated Curran's argument and reasons for bringing Miss Armstrong, the old bandit nodded approvingly.

"Ko-tsao, your wisdom is like that of heaven itself! I place myself in your hands, and when you arrange matters with your wretched brother, you will find that your orders are obeyed in Sing-an even as my own. Whether you leave him impaled at the gate, or give him the death of the thousand cuts, is as you choose. Now let us talk of leaving. A messenger from General Chang is here—wait a moment."

He summoned an officer, gave rapid orders in a dialect Curran did not understand, then helped himself to a cigarette and leaned back. Bill Harper smothered a curse, but said nothing.

"What are your plans?" said Yuan calmly.

"To leave at midnight, when we have rested," said Bill Harper. "We must gain the old temple of Tiau-tze; there we find the Japanese escort, who will take us to Feng-yang and on to the coast, where a ship is awaiting us. Our only difficulty lies in reaching the temple. If Chang knew our plans, he would not hesitate to cut us off despite his agreement with you. To reach the temple, we must pass his lines at the river-bridge, and we cannot do this by force. We can slip through if we do not have too many in our party."

"What arrangement do you propose?" asked Yuan sleepily.

"Let's go without guards, without escort," said Bill Harper. "Let Chang occupy the city at daybreak tomorrow. Leave your double here, wearing your robes, sleeping in your apartment, drugged with opium. Your men will surrender without a shot being fired. By daybreak we'll be in safety."

Yuan pondered this for a long moment, his eyes slipping from one to the other of the two faces before him.

"Agreed," he said to Harper. "Make arrangements for horses. I will join you in your room at midnight. There will be no baggage. Is there anything you wish done?"

"All is arranged," said Harper, and stifled a yawn.

"Very well; your orders are to be obeyed as my own. And now," and the lined saffron features with their gray wisps of mustache and beard assumed a sudden keen expression, "you may witness my interview with General Chang's officer. He is the colonel in command of Chang's bodyguard—a cousin of Chang."

Harper rose. "If the Venerable Maternal Ancestor will excuse me," he said sarcastically, "I will go to see about my arrangements. I have witnessed these interviews before."

He strolled away, while Yuan, apparently amused at the impertinence, flung an order at an officer. Curran sat motionless, puzzled, waiting.

In five minutes he understood why Harper had departed.

A man in uniform was led in by two guards, his arms bound behind his back. Both his ears had been sliced off—recently—and they were slung about his neck upon a cord. Apparently the wounds had been cauterized with hot irons. He was led forward to the dais, and the two guards retired.

Hardened though he was, Curran felt a little sick. The man met the cruelly amused gaze of Yuan with unflinching eyes, and waited.

"Let me tell you why this was done," said Yuan in a low voice, "so you may return and inform the worthy General Chang. It was done because I have learned about Chang's little killing on the river. My friend Colonel Ko-tsao, of whom you may have heard, rescued the prisoner from Chang's men and brought her to me. You may not understand all this, but your venerable cousin will understand perfectly. Tell him the incident is closed."

The hapless prisoner said nothing. Yuan surveyed him blandly, and smiled.

"Now let us discuss your errand here, in the presence of my friend Ko-tsao. Tell General Chang that I shall order the forts and city to surrender without resistance at daybreak tomorrow. If an attack is made before then, we shall fight, and the Yellow Carp mines will be blown up."

"How are we to know," spoke out the prisoner, "that they will not be blown up in any case?"

Curran leaned forward.

"Perhaps you have heard of Colonel Ko-tsao?"

"Who has not?" answered the man simply. Curran turned to Yuan—a straight look.

"Will the mines be destroyed or not?"

"It is for you to say, my friend," said Yuan, with a slight shrug.