RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

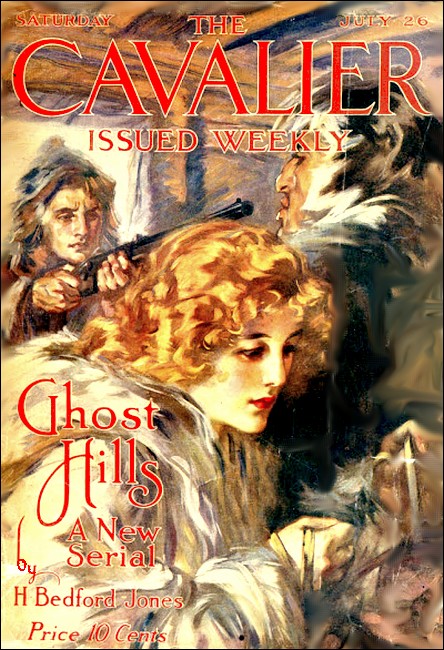

The Cavalier, July 25, 1919, with first part of "Ghost Hills."

"DONE, Take-a-chance!"

"Huh?"

"Last letter's done, and I'm ready."

"Time you were. Been writing all afternoon. Come on."

"What are all these breeds around for this morning? Isn't that unusual this time of year? Anything doing?"

"Sure—lots. They weren't breeds, but pure-bloods. That's what I've been after you to break away for. Hold still, Rad—listen!"

The two figures paused in the shelter of the stockade, beside an ancient little cannon on its crumbling carriage near the flagstaff. Above them flared and danced the lights in uncouth streamers and bands from horizon to horizon, and around lay the clay-plastered log buildings of Fort Tenacity, silent on the snow.

Despite the huge furs that enveloped both figures, their faces stood out clear-cut against the sky, distinct in the weird shadow-light. The one was raw-boned, gaunt with the trail, strong hewed of brow and nose and mouth, for Tom Macklin, or "Take-a- chance Macklin," as he was known from the Mackenzie to the bay, was a son of the lights by breed and birth and choice.

The other was finer-featured, save for his nose, which lent the suggestion of an eagle as he leaned forward, listening. But for the eyes, his face was not distinctive. The mouth was a trifle too firmly set, perhaps; the chin a trifle too short, but the level brown eyes blazed out with a strange intensity as if the owner sought something that lay far out of ken over the horizon.

Even so had Barr Radison sought, for the better part of his life. Blessed with money, he was cursed with the ancient curse of the wanderlust. Ever had he sought the thing undreamed of—the thing that had no name, and ever had he found that beyond the far skyline lay a new horizon, empty. The two men had met in Winnipeg ten weeks before, and Radison had looked Macklin in the eye for a long moment.

"Take me north, will you?" he had asked simply.

"Sure. I'll take a chance on your looks. Stick around—something may turn up."

The "something" had turned up. It had taken them north and northeast; it had drawn them west and then north again, until finally it had brought them to Fort Tenacity. And beyond Tenacity there was nothing.

Beyond Tenacity the breed trappers were not. Beyond Tenacity were Cree and Chipewa, with red snow between. Behind Tenacity lay white snow and the trail of the packet, traveled twice a year, for where the mail comes there must be no red snow.

In the north the mail is the law, relentless, irrevocable, unbreakable. Men are little things, and the mail is the greatest thing, for so the white man has ordained. But beyond Tenacity there was none to ordain.

"Hurry up—it's blamed cold out here!" exclaimed the American after a moment. Both men were staring at a log building next the store, which gleamed dull light through its one window. It was the largest building in the post, where canoes and dog- sleds were stored at other times.

"Hold on," rejoined Macklin stolidly. "Take a chance on hearing something—there he goes! Lord, what a man—stark drunk at that!"

From the building, which had a moment since echoed a raspy fiddle-squeak, rose a single resonant, liquor-charged bass voice. It was not singing; rather, it was intoning in a most monotonous and sing-song manner, as if it had been caught unawares by the stoppage of the Red River Jig.

...and he who will this toast deny:

Down among the dead men,

Down among the dead men,

Down, down, down, down—

Down among the dead men

Let him lie!

Radison grunted as the voice died out. "Pity but he'd learn

the tune—it's a heap better than the words! By thunder,

I'll take a shy at it just to show him how!"

Without warning he raised his voice, unheeding the quickly protesting hand of Macklin. He lilted out the swinging chorus of the old buccaneer song in a rough but virile baritone that exactly suited the words and air, until the stockade walls echoed it back again.

As he swung down to the last low note there came a roar from the big shack ahead, the door was flung wide, and out into the yellow-lit space stumbled a giant figure that seemed to blink around in questioning.

"Darn your imperious nose!" growled Macklin. "Now you've done it. Come along and see if McShayne can quiet him."

A moment later they stood within the area of light from the open door. Before them was a big man with flaring black beard and unkempt hair, opening and closing his huge fists as he swayed unsteadily. He glared at them, unmindful of the bitter cold, and a growl of words issued from the tangle of beard.

"An' who may you be, spoilin' my luck? D'ye know who King Mont—"

Another figure darkened the doorway and broke in with a keen, curt voice of authority.

"Montenay, come inside, you fool! Do you want to freeze? What cheer, Macklin! I've been looking for you. Hurry up, Montenay!"

Without a word of protest the giant turned and lurched inside. Radison guessed that he stood about six feet five, while his long, gorilla-like arms swung almost to his knees.

As Barr Radison and Macklin stepped inside, the man at the door slammed it shut, and they threw off their heavy furs. The Canadian, used to similar scenes all his life, kept an attentive eye on the mumbling giant; but the tall American was frankly interested in the people surrounding him.

This was the last day of a wedding. In the big shack donated by the factor for the purpose were crowded the families of the Cree couple, who had evidently come in from their winter grounds with this express object. Two days earlier the missionary had done his work, which was the least part of the wedding in Cree eyes.

After the feast had come the dance, kept up with ever fresh vigor by fiddle and ancient concertina with every variety of known tune, from the Saskatchewan Circle to the Reel of Eight and back again. The few whites who took part out of politeness had long since given up the struggle, but the Crees were tireless. Order was preserved by McShayne, an ex-corporal of the Mounted, now in the company's service. In the corner beside him stood Montenay, glowering and growling.

Now there came a pause in the festivities, every one watching the newcomers, for Radison had got in only the night before, and had seen few about the post save the factor and McShayne.

In that first moment the tall American with the wide shoulders and prominent nose caused a whisper of "Moosewa!" and a laugh that rippled through the chunky squaws, but he did not hear this.

For him the squalid shack held only high romance, the lure of a strange land and a strange people, and as his keen, brown eyes met those of the Crees he smiled in sheer joy.

But there was etiquette to be observed, and Radison had small chance to stare around him. McShayne seized his arm and turned him toward the bearded giant, for where dark men are there white men come always first.

"Shake hands with Barr Radison, Macferris Montenay. Radison's from the States, and came in last night with Macklin, here."

The cool, incisive tones of McShayne seemed to strike the giant into an amazed civility. He stuck out one hairy paw, then Radison felt the black eyes fixed on him in a peculiar glare, whether of liking or hate it was hard to determine.

"Radisson?" growled Montenay with a nasal twang. "Radisson? Sure, I'm not as far gone as that! Was it Radisson you said?"

"No," laughed Barr. "Radison—pure American, Montenay, and not French."

A puzzled look swept into the giant's face, and now Radison saw that he wore a belt that seemed made of bead-work, yet he had never seen such beads before. They were of a pure, lustrous white, interspersed with odd figures in red, lacked the usual backing of buckskin, and the whole affair was peculiar to Radison's eyes.

"But, man, ye spoiled my luck!" Montenay was looking down at him, an evil flame dancing in the bloodshot eyes. Macklin broke in at this instant, however, Montenay seemed to forget his thought, and Radison dismissed the whole matter as a drunken vagary. McShayne introduced him to the company in general, and to the bride's father in particular, and instantly all thought of Montenay dropped out of Radison's mind.

Uchichak, or the Crane, was a man of strength. From the narrow, almost Mongolian eyes to the vigorous mouth and firm chin, every line of his face bespoke crafty virility and power. His blanket capote was thrown open, but Radison saw that it was richly decorated in bead and quill work. The wiry black hair fell in a tufted strand on either side of his brown, sinewy neck.

As the American shook hands and met the steady, keen gaze of the searching eyes he felt that Uchichak was one of the real Indians of days gone by, and to his surprise the chief spoke in almost flawless English.

"Welcome, man with strong eyes! You have brought gifts?"

To Radison's relief Macklin pushed forward and held out packages of tea and tobacco. The Crane accepted them with stolid dignity, as befitted the tribute to his superior qualities from these white men.

"Nothing slow about him," thought Radison with a chuckle. "He's as different from most of these low-browed Crees as day is from night."

Uchichak waved his hand at the waiting fiddler. Instantly the crowd broke into the "Drops of Brandy" with the enthusiasm of pent-up energy, while Radison and Macklin sought shelter in a corner. To his surprise, the American noted that Montenay was treated in a coldly polite manner by the Crees, as if he were a guest to be tolerated, but not to be encouraged or warmed up to.

"What did Montenay mean about his luck?" he asked the other. "And what's that belt he wears? Looks funny to me."

Take-a-chance grinned. "I guess he's the problem we're up against, Barr. At least, so the factor thinks. He'll be in hot water with these Crees if he doesn't watch out. Shut up and lay low for a while."

Radison nodded, though he did not understand. He knew that for two months and more he and Macklin had been tracing silver fox and black fox pelts, and had finally brought the quest to Fort Tenacity.

When there are "white tobacco" posts scattered about in open competition with the great company, no one is very much concerned, for the Indians know only one Ookimow, or great master.

But when the free-traders begin to send down skins of black and silver fox with monotonous regularity, at the rate of two or three every six months, and when the company's factor gets none in a year, then the company may be pardoned for desiring an explanation—and desiring it badly.

Such was the mission on which the two men had come; Macklin, because it lay in the line of duty, and Radison, because he had chanced upon the task and scented adventure. They had spent two months on the winter trail, going from post to post, from Indian village to lost hunters' shacks in the wilderness, vainly. Always had come the same answer from stalwart Ojibway and cunning-eyed Cree.

"Kusketawukases? Sooneyowukases? Neither black nor silver skins have we seen, my brothers, for many winters. Of a surety, we would take them to the great master, for is not the company our father?"

Finally they had gained a clue from a drunken Chipewa down at Lake Doobaunt, and the clue had led them to Tenacity, on the edge of the Empty Places, where there was daylight the whole summer through—half-light that knew no change, save when the lights turned all things grotesque.

That first month had been torture for the American. Unused to the country, the life, or the food, Radison had been racked from head to foot. At night he had sunk down helpless, and at morning he had donned his outer moccasins with a groan; but that was all past now. Toughened by the long trail from Fort Resolution, he had experienced the inevitable reaction of clean, hard living, rugged fare, and more rugged work.

Well was it for him that this was so, for now the clue promised to lead even beyond Fort Tenacity—on into the empty places where the snow was red; where Cree and Chipewa had swept out the Esquimaux. Not far from Tenacity was an independent post where Murphy, a free-trader, played a lone hand against long odds.

The Empty Places were being filled. First the Crees had pushed up, with a party of wandering Saulteaux. Then had come more Crees, and the Saulteaux had disappeared, for Ojibway blood is full of the wanderlust.

Afterward had come the Chipewa rovers, bringing with them certain women of the Saulteaux, so that the fate of the latter was in no doubt. This had started the trouble, although there is age-old feud in the souls of Chipewa and Cree, ready to flame out instantly; and after Tenacity was built, the wanderers, outcast from their people to the south, had pushed on once more to north and east, and in their trail the snow was red. So said the gossip of the northland, and Radison had come to look forward to these Empty Places with keen anticipation.

He and Macklin had reached the fort the night before, half their dogs dead, and with them a half-crazed runner bearing the mail, whom they had found perishing of hunger.

Radison had slept late in luxurious repose, then had fallen to work writing letters to go out before their trail had been covered. His sole family tie was the brother back in Baltimore, and Radison had no mind to sever all connections with the past. So he had yet seen little of the post itself, and Montenay had been a complete surprise to him.

He watched the big, heavily bearded giant as the dance proceeded. More than one Cree flashed a glance of quiet hatred at this white man who forced the women to dance with him, but Montenay paid little heed to such things.

Watching him, Radison was moved to give grudging admiration to the splendid physique of the man; and there was something fascinating about the high brow, strong bearded jaws, and massive features, though the eyes gleamed with a drunken leer.

Montenay seemed upheld by a tremendous pride, an arrogant sense of authority, which the American could not understand.

Suddenly Uchichak rose from his seat and lifted a hand. Upon the instant the fiddle ceased and the dancers fell away. As quiet settled down over the shack only the harsh breathing of Montenay could be heard, and the Crane flashed a look of contempt at him. The American leaned forward, keenly interested.

"There are many trails awaiting us, my brothers. Our lodges are far. Our traps call us, lest we fail in our debt to the Great Master and our lodges be empty of food. White Berries!"

The bride came forward and knelt at his feet, about her head the shawl which had been given her by Factor Campbell. Uchichak waited to be sure that every eye was fixed on him, then leaned down and kissed her.

"For the last time. Kiss now your husband, and after that no other man."

The groom, a stalwart young Cree, stepped forward, but another was ahead of him. Montenay, his eyes aflame, brushed him back with a drunken laugh.

"One first, Uchichak! Macferris Montenay owns this country, so, m'dear—"

A hoarse growl of rage quivered up from every throat; but even before the knife of the Crane whipped from its sheath, Montenay crashed down in his tracks. Over him stood Barr Radison, quivering with rage, and from his knuckles gathered a bright red drop that fell unheeded to the floor.

WHILE the serious-minded Macklin leaned over the map with Factor Campbell, Barr stretched back in his chair and stared at the log ceiling.

The stove was red-hot in the back-room of the trading store, and looking through to the larger room, Radison could see McShayne surrounded by squaws, who filled the space inside the long U-shaped counter.

Behind, on racks, and hung from the rafters, was every conceivable object, from sowbelly and blankets to pain-killer and flintlock muskets.

Thinking over the events of the night before the American had almost concluded that a certain Macferris Montenay was not right in his head. It was peculiar, mused Radison, that after he had knocked Montenay down the giant had made no offensive move.

He had raised himself on one elbow, stared up at his assailant, whom he could have broken across one knee, with a queer, almost frightened expression and a mutter about his "luck." Suddenly Barr realized that Macklin was speaking to him.

"Here, old man, the evidence is all in, and you'd better get the result of the inquest. Give him what you know about the pelts, factor."

"I know nothing about 'em," Campbell grunted. "It's all news to me, and if such furs are going out, then Murphy must get them from the Chipewas. None of the Crees go near the Ookimasis, or Small Master, as they call him, and he caters to the Chipewas; we get a good deal of the Chipewa trade, just the same."

"Where does Montenay get his liquor?" shot out Take-a-chance. "Murphy?"

"No, nor from me," returned Campbell sturdily. "Whatever he does, Murphy is clean in that respect. As for Montenay, he's been up here for years. Where he came from no one knows; but he's a big man among the Chipewas, though I doubt if he's a squaw- man.

"Once in a while he blows in here with some common pelts, seems to have plenty of liquor, and is eternally chanting that fool song of his—calls it his 'luck.' The Crees hate him like poison, but I never could learn just why. They don't talk much about what happens out yonder, you know.

"The missionary expects to get a church up this summer; but, Lord, the Crees don't bother with religion since old Père Sulvent vanished! He was the boy could hand it to 'em!"

"Who's he?" queried Radison. "What do you mean by vanished?"

"Same as the dictionary," came the curt answer. "Sulvent was a Frenchman, with Irish blood. He went out on a trip six months ago, when the darkness had come; but he never came back. He'd handed it to Montenay pretty heavy just before, and that may have something to do with the Crees' hatred; but I don't know. Maybe it was frost got him; maybe a bullet."

Macklin nodded, frowning, and Radison's eyes glistened.

"Do you mean there's actual war out there?"

"The Lord only knows what's out there, Radison, and that's the truth," returned the factor wearily. "The Empty Places are hell; I've been out once or twice; but it's too much for me. Montenay always strikes off to the northeast, and a man must have the fear of God or the devil in him to make that trip alone. Murphy lives there, on the edge of things, and he often comes over here with his daughter—"

"Daughter?" broke in Macklin. "Does the fool take a chance like that? Is she a breed?"

The factor shook his head sourly. "No—our kind. She's lived there for a year, now; Père Sulvent got him to send her back to Quebec to school. That was years ago, before my time here; but I've heard that she was born up here, and her mother died, after Murphy started his God-forsaken post.

"It's my idea that Montenay lords it over the Chipewas, for when he's drunk he calls himself 'King Montenay,' and Murphy seems to know him pretty well."

"What's that belt of his, Campbell?" asked the American. Macklin grinned.

"That's what we all want to know, Barr! The factor swears that it's wampum—the original shell wampum like the old Injuns used to make down south. That's all rot, though."

"Don't be too sure, Take-a-chance," retorted Campbell. "Four months ago, with the first snow, a Chipewa came in to get credit with us. He carried a rifle, but besides that he had a flintlock pistol. Where did he get it?"

"Murphy, of course," said Macklin. The factor grunted disgustedly.

"Murphy don't trade pistols stamped with the Fleur-de- lis and the date 1704," was his dry answer. The others stared at him.

"Do you mean to say that a two-hundred-year-old flintlock pistol can still be in use?" demanded the Canadian.

"Aye, perfect in every way. The Chipewa refused to trade it, and said he carried it as big medicine.

"Now, there's something almighty queer out there, boys, and Macferris Montenay is behind it. He's no fool, that man. Any one who can win the hatred and respect of these Crees about here, and still live to enjoy it, is going some.

"Where that wampum belt or that pistol came from, I don't know; the old French and English traders were never up here, to my knowledge. But if all them black and silver pelts go out every year, I'd either say that somebody is a blamed liar or else Montenay has a fox farm—which don't fit exactly."

"No," laughed Radison, "a fox farm doesn't fit in with Montenay very well. I'm inclined to think the man is crazy, myself."

"The Crees call him Crazy Bear to his face," chuckled Campbell. "That suits him, all right. Well, that covers all I know. I've sent for Uchichak—hello! Here's the chief now, to a dot!"

"What cheer!"

In the doorway appeared the Crane, his woolen capote slashed with red on arms and hips, a gay scarlet sash about his waist. He gravely shook hands with the three, then pulled out his pipe and sat down. Without preamble Macklin divulged his story for the benefit of the Cree, whom Campbell declared they could trust thoroughly.

Uchichak listened in silence. Several times Radison caught the beady eyes fixed on him, and remembered the wordless handclasp he had received after the affair of the previous night. The Crane was a man who spoke little, and when Macklin stated that Radison was with him there came a little gesture of inquiry.

"He is my friend," replied Macklin. "He is an American, from the States; not of the company, but to be trusted. He is a man, my brother."

The chief bowed his head gravely and Macklin went on. Suddenly the dark face flashed up and the deep, even voice broke in.

"Wait. Has my brother seen these pelts of which he speaks? Are they fresh, or are they old?"

"By thunder!" ejaculated the other quickly, "I clear forgot about that, factor! I saw one of them down at Winnipeg. It was hard, very dry, and creased pretty deep, as if it had been laid away for a long while. No, it wasn't fresh at all, Uchichak, but it was in prime condition just the same."

The chief puzzled over this inscrutably until his pipe and the story were concluded together. Campbell handed him a plug of tobacco, which he stowed away after whittling off another pipeful.

"It is well, my brothers. Do you wish to follow Crazy Bear when he departs?"

"That seems to be the only thing to do," returned Macklin doubtfully. "How about dogs? What's left of ours are all to the bad, and our sled is pretty well banged up."

"Uchichak has the best dogs around here," put in the factor. The dark eyes gleamed with pride and the Cree nodded.

"The Crane will go," he decided quietly. "But my young men must follow us. We must take with us food and powder for a long time. The journey will be a very bad one; but not even Crazy Bear will dare to harm one of the company, and the others will fear. We must follow in secret while my young men are gathering. That will take time, my brothers, for they are on their fur-grounds now."

"They shall not lose by it," promised Macklin. "Their debt for this year shall be wiped off the books. Yes, we must follow in secret, and then come to him openly as if we were surveying for the company. If we can persuade him to throw those pelts to us, and perhaps find out where they come from, there will be more rewards for you and your men, Uchichak."

"Miwasin! Good!" returned the chief, his eyes glittering. Campbell grunted, for such wholesale promises were not at all to his liking and promised to make wild confusion with his books. Still, orders were orders, and Macklin was to have a free hand in everything that he wished.

Radison knew that the Crane would be a powerful aid to them in their quest. In thus deciding to strike off on the trail of Montenay into the Empty Places they were attempting a desperate venture, and from what they could learn of these same Empty Places they were likely to run into trouble.

Neither man was of the stamp to hesitate on that account, however, and it was unbelievable that Montenay would dare offer violence to any men directly in the company's service.

Such a thing was unheard of, even in these days when the north country is open to all traders alike; for, although the wastes have changed hands, it has not changed masters, and every "nichie" from Rupert to the Great Bear is fully aware of the fact.

Now, the Crane and Tom Macklin put their heads together, while Campbell made out the list they would require from his stores. The largest item, of course, was frozen whitefish for the dogs, the chief priding himself on his team and regarding them above all else, which was well, for three men's lives might depend on those dogs ere Montenay was run down to his lair.

The Indian's heart was made glad by the gift of the extra rifle which Macklin had brought. The company trade-guns are good weapons enough for hunting and fur-killing, but for such a trip as lay before them it was more fitting that the chief should carry a rifle. Also, as Campbell grunted, it was safer.

"Nonsense," laughed Radison easily, rising and stretching himself. "We're not leading any war-party, Campbell. There's no harm in paying Montenay a visit, and I don't mind saying that I'd like to have a look at that freetrader's post."

"Yes—her name is Noreen," chuckled the factor. "The Injuns call her Minebegonequay—Girl-with-flowers-in-her- hair."

"Get out of here, you old humbug!" added Macklin with a grin. "We have something else to think of if you haven't. Take a chance on meeting your friend Montenay, and get along with you!"

Radison laughed easily and strolled into the outer room, where McShayne had got rid of the squaws and was bartering with one of the Crane's men. To tell the truth, he had not had the free- trader's daughter in mind when he spoke, but he carried the name out with him reflectively.

Noreen—it was not hard to guess at Trader Murphy's mother country. As to the Indian title, Radison already knew enough about northern nomenclature to make a shrewd guess that Noreen Murphy was either red or golden-haired. Therefore, she must be pretty; and Murphy was a fool to keep her up here in the wastes.

Rather pleased with his own deductions, Barr filled his pipe from McShayne's plug and put a question or two to him about the Empty Places. The ex-trooper watched the Cree go out, flung the pelts behind the counter, and emitted a growl.

"Wanted nothing but powder! That crazy fool Montenay will get a bullet in the back yet. Why, as to the Empty Places, every one talks and no one knows anything. I've heard say that the Spirit Dancers live out there in the hills.

"You don't know what the Spirit Dancers are? Why, the northern lights—that's what the nichies call the lights. Think they're ghosts, I s'pose. Dunno's I blame them much. Take 'em sometimes and they sure do look human-like, especially if a man's on a lonesome trail and kind o' off his head."

McShayne could or would say little about the red snow, however, except that out in the wastes anything might take place. Barr gathered that the post stood in what might be termed neutral ground, which accounted for Montenay's visits. The actual conflict, if conflict there were, would be more apt to happen out on the lonely hunting-grounds, and those at Tenacity knew nothing of it save when some hunter failed to take up his debt.

"That's the devil of it," concluded the aggrieved corporal. "It wouldn't matter how much they scrap if them as gets killed only left life-insurance, but they don't. Last winter as many as a dozen accounts had to be put down to loss. Good thing Murphy won't sell 'em liquor on the sly, like some freetraders do."

Where, then, did Macferris Montenay get his liquor? That question was flitting through Radison's mind as he nodded to McShayne and stepped to the door. Evidently the giant had some secret supply of his own.

As he emerged into the sunlight the American halted abruptly. A dozen feet away stood Montenay himself, calmly smoking a pipe as he worked over a broken snow-shoe. Barr tensed his muscles for instant action, but to his surprise the other merely nodded amiably.

"'Mornin'!" Montenay set down the long shoe, leaning carelessly on it as he met the eyes of Radison. "Name's Radisson—or do I misremember?"

At this astonishing greeting Radison chuckled to himself.

"Speak it English fashion, Montenay. It's not Radisson, but Radison, and I'm no Frenchman. I thought you might be wanting to punch my head this morning."

To the half-quizzical look that accompanied these words Montenay replied with a slow shake of the head, his face serious.

"Young man, that blow o' last night saved Macferris Montenay from a Cree knife, belike, an' I bear ye no ill-will—for that. From the States, eh? I was part ways under liquor, but I remember that plain enough. Also, ye spoiled my luck, an' I remember that."

A puzzled look flashed into Radison's face as he gazed at the big fellow and met the dark, passionate eyes.

"If you call that old pirate song your 'luck,' you're off your base. Why on earth don't you learn the right tune if you want to sing it? As to the other matter, I'm glad that you aren't out after my blood, for, to tell the truth, I'd rather let you scrap with some one else."

Montenay did not respond to the laughing words for a moment. No light answered from his heavy face, and he stared at the other with that same serious, somber air.

"Ever chance to hear o' him that founded the Hungry Belly Company?"

"Who?" asked the puzzled American.

"Why, him that found the Mississip', him that vanished somewheres—him, the friend o' kings an' king o' Hudson Bay while he lasted, before they betrayed him?"

"You don't mean the Canadian, Pierre Radisson?"

"Aye, but I do! Pierre the Great he was. Listen, now! Go back where ye came from, Radisson; don't think the prophecy is so easy carried out, even if ye do bear his name."

With which enigmatic speech the big man flung the snow-shoe over his shoulder and tramped away, leaving Radison standing in blank wonder.

Montenay was crazy, certainly. That was the only solution, and for an instant Barr felt troubled over their journey after him. That he himself bore the name of Pierre Radisson might be true, though he had no thought that he was a descendant of the old explorer.

One or two squaws of the Crane's party, flitting silently by, threw admiring glances at him, and with an answering wave of his hand Radison dismissed the vexing problem of Macferris Montenay.

"I'm glad to be alive!" he muttered, looking upward at the sky. "Glad to be here! Glad to be in this new world! I think—I think that I have come to be proven at last in the midst of snow and crazy men!"

With a little sigh of humorous contentment he re-lit his pipe and turned back into the store. He did not notice that the squaws had suddenly veered from the shadow of a small, lithe man in the stockade gateway, a man who wore moccasins of Chipewa cut, and who defiantly filled his pipe from a whittled plug of "white" tobacco in the very gateway of the "black" tobacco post.

SPAT! Spat!

Still dreaming of Broadway, Radison awoke. He laughed aloud as the log rafters overhead recalled him to the Northland, and his laughter was echoed by another dull whip-crack, loud in the frost without.

"Must have fallen asleep while I waited," he muttered, sitting up with a yawn. "Hello! This looks something like!"

He went to the window, and stood there in awe as the purple light blazed dimly on his face. Many times had he seen the lights, but never like this.

Across the sky flitted grotesque-sheeted figures of lambent flame, dancing, whirling, flinging many-colored ribbons in what appeared wild confusion—yet to the American it seemed that there was something methodical, something human behind it all.

Up and across and back again the fires flashed, as if some unseen hand were playing on a mighty keyboard in a vast harmony of colorings.

"Radison! Get your shoes—here's the chief!"

Barr came back to earth with a start as the voice of Macklin rang out, followed by a yapping of dogs. Turning, he slipped into his thick blanket capote, knotted the sash, and drew up the hood. Then he took his moosehide-cased rifle, emerged from the shack, and got into his snow-shoes, upturned at the toes in Ojibway fashion. Take-a-chance Macklin and Uchichak were standing beside a heavily laden dog-sled, waiting.

Six hours before Montenay had departed with his team alone, as he had come. What preparations the Crane had made Radison did not know, for the chief had vanished after that talk in the store the morning previous.

That Montenay suspected the errand of Macklin and Barr did not appear. In fact, none knew of it save the factor and Uchichak, and Montenay had asked no questions. He had brought in pelts to the value of thirty skins—a "skin" being a dollar in the north—and had taken in exchange, to the utter mystification of Campbell and McShayne, a load of such delicacies as tinned goods, beef extract, and unadulterated tea.

"The devil must be settin' up housekeeping," had growled the ex-trooper. "Why didn't he go to Murphy for 'em? I wonder. He's never got such stuff here before."

"He may have his eye on Minebegonequay," suggested Campbell in heavy facetiousness and with a sly glance at Radison. "Better make a trip over there, Rad. You might spoil his luck in another direction."

"Not on your life!" laughed Barr. "I'm no trouble-hunter!"

Now, in impressive gravity, the factor and his assistant came out to see the party off. There was a handshake all around, Macklin nodded, the chief cracked his whip and emitted an equally snappy mash, and the dogs leaned forward on the traces.

Handing over the whip to Macklin, Uchichak preceded the team more from custom than from necessity. Radison saw at once that they were following a newly broken trail. He did not need the finger of Macklin pointing at the oval-shaped snow-shoe track to know whose it was.

"There have been no sundogs," declared the Canadian confidently. "We'll probably have a clear run all the way, so it's safe to give him his six-hour start and take our time. We don't want to catch him till after he's reached home, wherever that is."

The day-like night was coming on bitterly cold, and it was not long before all three covered their faces up to the eyes. Uchichak did not hurry, for the sled was heavy with fish and pemmican bricks and other things—such as cartridges.

That their run would be a long one all knew well; but the march was a silent and ceaseless "sluff-sluff" over the snow, until Radison exclaimed in wonder at a particularly brilliant flare of the lights, which shot red and green far above the zenith.

"They are the Spirit Dancers," affirmed the Cree solemnly. "Crazy Bear prays to them, and his Chipewa braves make big medicine. We know that they are only the spirits of the dead watching over their children, the Naeyowuk (Crees)."

With a slight gesture of contempt the stalwart chief swung ahead, his bronze face immobile. Macklin turned with a grin and a low mutter of words.

"Montenay prays to 'em, eh? Looks like we're up against something ugly, Barr. Wouldn't be surprised if he had started some newfangled religion up here among the Chipewas. We may have a second Riel rebellion on our hands, north of the circle!"

Radison did not reply. So Montenay prayed to the Spirit Dancers—why? Was the man really crazed? What was the meaning of his allusion to the "prophecy"? But there was no answer to his questionings, and the three slapped along in silence while the slow miles slipped behind them.

They had left the Arkilinik behind, and with the passing of the river only jack-pine and spruce and snow-barrens stretched around in wild wastes that had no end and no beginning.

"Is the free-trader's post anywhere near here?" asked Radison suddenly. Macklin shook his head, but the chief answered from in front.

"It is a day and a half from the black tobacco house. Crazy Bear travels fast toward it. To-morrow we will meet Niska, one of my young men, at the Wusap. There we will rest and gain news."

Wusap Lake, according to the map Radison had seen in the factor's store, lay northeast of the post some fifty miles. Beyond this lay the "white tobacco house"—so called because the free-traders sell the light-colored plug, that of the company being dark in color.

Ever as they trudged onward, the Spirit Dancers leaped and twisted across the sky, and a faint rumbling as of distant thunder came out of the dim north. Hour after hour fled past, and still the "sluff-sluff" of the shoes went on at an even, tireless pace. The team of huskies was a magnificent one, and Radison knew they could overhaul the bearded giant if Uchichak was so minded.

It was not until after midnight that they halted in a little clump of twisted jack-pine. There was no deep snow among the trees, and they soon had made camp. Radison had already noted that the Cree wore Ojibway shoes like his own, and now Uchichak built a conical fire, standing the sticks on end.

"Some Chipewa might be hanging around," explained Macklin, throwing a fish each to the dogs. "If he saw a Cree trail or a Cree fire on Montenay's trail he'd get suspicious; but if he finds our tracks or this fire he'd lay it to a Saulteaux party. The Saulteaux wander all over, and get up here now and then. They're willing to take a chance on being wiped out—and they take considerable chance up in this country."

The halt was short—only a smoke, to give the dogs a rest and to make a cup of tea. Then they sped on again, hour after hour, and gradually the Spirit Dancers faded out into faint silver streamers that slowly died away into nothing.

The American was striding along behind the sled, followed by Macklin, when he saw Uchichak suddenly fling up his hood, throwing back his head to listen for an instant. Radison glanced about quickly, but the waste of snow and scattered tree-clumps was as lonely as ever, and if the Indian's keen senses had caught some warning flicker of shadow or branch, it did not come to the others.

From near and far the frost was cracking the trees, for there had been a slight thaw the day before, and the limbs were sending forth reports that rang like pistol-shots.

That Uchichak had caught a warning became evident five minutes later. One of the dogs uttered a quick, short howl, commenced floundering in the snow, and within a moment the entire team was in a snarling tangle of bodies. Leaving the others to attend to the dogs, Uchichak caught up his cased rifle from the sled and whirled about.

Radison thought that he caught a faint gun-shot drifting to them, but it might have been frost in the trees. The snowy wastes were bare as ever and there was nothing in sight to indicate any enemy; but when Radison turned to Macklin the other had straightened out the team, and one dog lay dead, shot through the body and freezing already.

"This looks like business, chief," exclaimed Take-a-chance quietly. He sent a thin-lipped, mirthless grin at the American. "I guess that's a pretty plain hint to mind our own business, eh?"

"Who from—Montenay?"

"Lord knows! But I doubt it. Sounded like a trade-musket; pretty distant shot, and it was evidently meant for the Crane. Hello! Going to camp?"

Uchichak was already squatting over some twigs and a shred of birch-bark. He answered without looking up, in a voice that sounded like the snarl of a dog.

"Stop one smoke. Rest the dogs."

No sooner had he swallowed a cup of scalding hot tea than the Crane took up his rifle and slipped away over the snows toward the left. Radison filled his pipe and settled down beside his comrade, who seemed to take the happening with calm unconcern.

"You're an emotionless sort of beast, Mack! Think he'll find any one?"

"No." Macklin shrugged his shoulders. "Wants to find which way the beggar went. I'd take a chance that it wasn't Montenay, though. What's the matter—tired?"

"Not a bit. Just thinking, that's all."

He stared out over the snows, absently watching the distant figure of the Crane. His companion threw a quick glance at him, but ventured no comment. After a moment the American turned with a grunt and flung an entirely useless twig on the fire.

"Funny how some things will bring back other things, entirely different, isn't it?"

"Hope the chief brings back something that looks like a Chipewa," returned the Canadian curtly. Radison smiled.

"You know I don't mean that. Stop your fooling, Mack. I just thought of something that I'd forgotten all about for six years. I had left home at nineteen, and after a bit I got mighty sick of the tourists I was with in Spain.

"I skipped the bunch at Cordova and went up to Madrid with a mule-train—through a damned desolate part of Spain, too. Well, one morning a mule died. That was all.

"I hadn't thought about it for years, but somehow this brings the whole scene back to me—the little line of mules, me with my camera, Pedro and Vasquez cursing like devils as they changed the packs about, and a solitary guardia civile riding past across that sun-damned plain."

He paused, staring morosely into the fire. Macklin was frankly puzzled by his mood, for there was nothing of the dreamer in his rugged nature. After a moment he removed the pipe from his mouth and waved it at the dogs.

"What's the sunny land of Spain got to do with this? And why the blue streak? I don't quite get the connection, Barr."

"Because it brought me back to where I was then—made me realize the years between, that's all. There's no connection, of course; only this scene happened to bring back the other one. Makes me think of the six years' difference in myself."

"Huh! You ain't exactly cheerful over it. Been murdering anybody? Stole anything? Broke any hearts?" The bantering tone suddenly became earnest. "Got a girl anywheres?"

"No," laughed Radison. "It's only that I'm getting old, Mack. Lord, no! Not remorse, or anything like that—simply that I'll never be nineteen again. I've lost my grip on youth, and I wish that I had those six years back."

Suddenly comprehending, the other knocked his pipe out against his moccasin.

"Listen, Barr. You ain't lost much in that six years, I guess. You've been decent, I mean; you've been doing things; you've been growing all the while?"

"On the outside, yes. But I'm not so sure about the inside. I don't look at things now the way I did then—well, it's hard to explain."

"Shucks! You need some sass'fras tea. Why, you can't grow on the outside unless you grow inside first. Ain't that right? As for looking at things, wait till you're fifty or so; if you look at 'em half-way decent by that time, you'll be in pretty safe shape to take the last trail. Why, you ain't full-grown up yet, partner! Talking about losing your grip on youth—rats! All you need to do is to reach out and grab her again—like getting your second wind."

"Maybe you're right," and Barr hesitated a moment, biting his lips. "But I'm a useless sort of cuss to everybody except myself. Six years—and it's gone unnoticed!"

"Well, you wouldn't expect it to rise up and whack you over the head, would you? But here's the chief coming back, so we'll adjourn the meeting for a bit."

Radison, flinging off his mood, emptied his pipe and rose to meet the tall figure of Uchichak. The latter had circled around behind and came in from the right; now, in response to their questioning looks, he shook his head.

"There is a usam trail, but there is no time to follow now."

"Chipewa snowshoe?" asked Barr. The chief nodded grimly.

"To our right, leading east. If I had struck to right instead of left, my brothers, I might have gained a shot. Kisamunito, the Master of Life, has spared him to another day. It is well."

Uchichak philosophically strapped his rifle on the sled and caught up the dog-whip, Macklin now breaking trail. A light, keen wind was sweeping down across the barrens, but Macklin pushed up the pace and they were soon all aglow.

Silently, putting all their heart into the work, they pushed on through the morning, and at noon came to a narrow stretch of ice, bordered with heavy, snow-burdened pine and spruce. This Uchichak stated to be an arm of Wusap Lake, and here they halted.

After the kettle boiled and the frozen pemmican was soft, the Crane flung a handful of old birch-bark on the fire. Up darted one full puff of smoke, and the next instant he scattered the small blaze with his foot.

"The Goose is near by," he deigned to explain, "and Niska is cunning of eye."

Radison settled down to wait, and the three held a low discussion as to the slayer of the dog that morning. It was finally decided that it must have been a Chipewa who had wandered on their track, and that after the shot he had fled on ahead toward his own people.

Without the slightest warning, the bushes on the opposite side of the ice, fifty feet away, opened and an Indian stepped confidently toward them. Guessing from the calm demeanor of the chief that the newcomer was Niska, or the Goose, Radison watched the short, sinewy man approach.

"What cheer!" was his greeting, to which the three answered as one. Then came a rapid dialogue between the two Crees. Niska's face darkened, and he gave an angry exclamation, but Uchichak turned to his companions.

"The Goose passed a breed from the south—a man named Nichemus, who dwells with the Chipewas," he said. "It was he who killed the dog. Also, the man must have followed us from the post. Five miles ahead is a camp of ten Chipewas. Crazy Bear is with them."

Macklin uttered a grunt at this surprising information.

"He had us spotted, Barr. We'd better join him openly, chief,"

"No." Uchichak shook his head. "The Goose overheard their talk, and it was not of us. They have some other plan on foot, my brothers. Crazy Bear looks toward the white tobacco-house for a squaw."

"I feel sorry for Murphy's girl, then," stated Radison, and he felt oddly disappointed. Minebegonequay was a pretty name.

Finally it was decided that Niska should return, gather what Crees he could, and meet them at Murphy's. In case Montenay made any trouble, which Macklin did not expect, a few braves might came in handy; besides, as the Crane said, the absence of the Chipewas from their fur-grounds looked suspicious.

"The chief and I will take a scout ahead, and maybe drop in on Crazy Bear," concluded Macklin. "You stay here and rest up, old man. This affair don't look just right."

Niska finished off the tea and pemmican and started on the back trail. Barr made no objection to Macklin's proposal, for the hard trail had worn him out and he was glad to rest. Besides, the Canadian knew his own business best.

Five minutes later Uchichak and Macklin departed, sweeping out to the left in a wide circle. Radison built up his fire again, rolled up in his blanket, and was fast asleep in a moment, too weary even to smoke.

"I T'INK me he's be one ver' fine gun—make for keel one, two mile off, mebbe." The liquid, reflective words were followed by a swift, vicious kick in the side that jarred Radison awake instantly. Flinging his blanket wide, he sat up and stared in puzzled wonder at the speaker.

Brown of face, yet far lighter than an Indian, the man was small, wide-shouldered, and plainly possessed tremendous strength beneath his dirty white capote. The hood of the latter extended over his head in two points, like lynx ears, and on the front were worked rude eyes in red beads and quill which lent him a striking appearance, to say the least.

It was not this that caused Radison's wonder, however, for the man was coolly regarding him over the sights of his own rifle, whose casing lay on the snow at his side. The American frowned, comprehending.

"What's this—a hold-up? Who the devil are you?"

"Be ver' quiet!" The warning voice held a menace that could not be mistaken, and Barr sat still. A glance around showed that his fire had not died down, so that his companions had not been long away.

He remembered the message of Niska—this man must be the breed, Nichemus! No doubt he had followed the Goose back, had seen the departure of Macklin and Uchichak, and had descended upon the camp forthwith. Yet surely there must be some mistake, thought the American; this hunter would never dare attack men in the service of the company.

"Are you Nichemus?" he asked.

"Oui, Jean Nichemus, m'sieu!" The breed grinned. "B'jou, b'jou!"

"Put down that gun," commanded Barr quietly. "Do you know that I am in the employ of the company? What do you mean by this?"

Nichemus quickly slid back a few paces, but held the rifle steady.

"By Goss, you be quiet!" Again the glittering eye warned Radison. "We don' got no p'leece by dis place! W'at I mean, hey? You fin' dat out ver' soon, Meestair Radisson. You go for make scrap, de Crane, he fin' one dead man on de cam'."

The humor of the situation struck Radison oddly, and he laughed.

"All right, Jean; I won't start anything, since you have the drop on me. Now suppose you get down to cases. What're you holding me up this way for? Don't you know that if the company turns on you it can drive you into the ground like a rat?"

"De comp'ny—Here before Chris', hey?" There was a note of supreme contempt in the voice of Nichemus as he used the slang phrase for the H.B.C., which held more truth than most slang phrases. "W'at do I care for de comp'ny? She's be de one beeg cheat, dat comp'ny."

"Well, what in thunder do you want of me?" cried the exasperated American.

"You," came the cool retort. "De king he's say to me, 'Go for catch dat Radisson. Don' keel, jus' catch.' So I come on de cam'; now we go see de king."

Radison stared at him, bewildered.

"Say," he gasped at length, "is every one crazy up here, or am I off my head? What king are you talking about, Nichemus? You'd better get a move on and clear out of here before Uchichak gets back."

The breed's face darkened.

"I t'ink me you be de one beeg fool. Mebbe you nevair hear of Mont'nay? Now you get up, or I shoot."

In a flash Radison understood.

Montenay! The giant had sent this breed to get him without injury, for some purpose that could not be guessed, but Radison had no mind to obey such a peremptory summons. He glanced about the camp with a smile.

"Shoot your blamed head off, Jean," he returned cheerfully. "You won't budge me out of here; so you can forget that part of it."

"So?" The other nodded toward a twig snapped out from the fire, lying within an inch of Radison's hand. Before the American guessed his purpose the rifle shifted and spat flame; as the sharp crack echoed over the barrens and brought him up, startled, he saw that the twig had vanished. Instantly Nichemus jerked out the shell and covered him again grimly.

"You see? Mebbe you come now, hey? Nex' time I make for hit your han'—one finger go lak de twig."

There was no mistaking the earnestness of his voice, the uncompromising, deadly eyes that looked over the rifle-sights. Radison merely nodded and got to his feet, for Jean Nichemus was plainly not a man to be trifled with and fear of the great company lay not in his heart.

Radison began to realize that if Montenay was a maniac, he was unusually sane for a crazy man; also, that Jean Nichemus was like to prove worthy of his master.

"Well, Jean, what next?" he said with a grimace as he rose.

The breed lowered his rifle, regarding the American curiously. In turn, Barr took in the sensitive yet brutal face, the dark, liquid eyes, heavy lidded with strength and cunning, and the coarse black hair that was almost the only trace of the man's motherhood—that and the eyes.

It occurred to Radison that the rifle-shot might serve to recall his comrades, but the breed must have known they were safe from interruption or he would not have fired. With a little gesture of decision Nichemus stooped for the rifle-case.

"M'sieu, you give me your parole—ver' good, den we go for see de king."

"And if I don't?"

"Non? Den we go, anyhow."

Radison's jaw set aggressively for a moment; he was not used to receiving orders in this fashion, and it rasped him the wrong way instantly. Then the cool, determined manner of the breed was borne in on him, and he assented.

"Very well. I give you my parole until we reach Montenay—and if you think he's a king you're very much mistaken. Wait till Macklin comes back and you'll see your king jump down off his perch mighty quick, Jean!"

The other only grinned cheerfully, cased the rifle, picked up his own musket, and untied his snow-shoes, which he handed to Radison.

"Put dem on, m'sieu, an' follow my trail back. I t'ink me dat Uchichak be one ver' 'stonishe' fellair, non?"

Radison was not so sure that Uchichak would be puzzled, but the ruse would, at least, serve to hold Macklin and the Crane here for a time on their return. Radison swung off on the trail of the breed, while Jean slipped on the American's shoes and followed, carefully covering the trail, in order to make the others think that Barr had gone out alone.

That he was in any danger from Montenay never entered the head of Radison, and yet he was decidedly worried over this abrupt and forceful summons. The more he had seen of Montenay, the more he liked other company, and the fact that Nichemus seemed to have an all-abiding trust in his master's power was by no means reassuring.

Barr Radison had seen a good deal of other men with the mask off. He had gone through the Cotabatos with a dozen lost troopers, he had found Sokotra with a motorboat and well nigh stayed there, he had braved the Lorian Swamp with two daredevil Afrikanders, and he knew that Jean Nichemus was just plain man, every inch of him, and not quite up to his own mark when it came to that. But Montenay was different. Drunk, Montenay was a gorilla. Sober—

"God knows!" he thought to himself, "when Montenay is sober he's either stark mad, which isn't to be wondered at in this country, or he's a good deal more of a man than I've ever met before. I think we'll have quite an interesting bit of conversation, Mr. Macferris Montenay—and if you try to come any of that king business on me, there'll be more than conversation!"

With a little scorn of the man, he looked back to see Nichemus crunching down over the tracks he left, sweeping them as he strode with the tasseled end of his rifle-case and obliterating every trace of the shoes worn by the American. Though the cunning swiftness of the work was admirable, Radison knew that neither Macklin nor Uchichak would be deceived into thinking that only one man had come and gone.

"It's second nature to him, that's all," he concluded as he followed the oval tracks that Nichemus had left in reaching the camp. "He's on dangerous business, and he covers the trail just as Macklin stamps a burned match into the snow, from force of habit; one's about as useless as the other, but at certain times it may mean everything."

Across the lake they went, while overhead the Spirit Dancers sent long, shuddering, grotesque shadows moving all around them; the woods seemed peopled with quivering life, and as they drove up the hill beyond and through the trees that stretched dark and silent ahead, a strange sense of oppression began to fall upon Radison.

Soon the woods were all about them, and that indefinable oppression leaped into something very like fear as from the distance, thin and clear and sharp, rose a single whine that deepened suddenly—"Whi-i-i-i-mbuh! Whi-i-i-i-m-buh-h-h!" Then another and another and another joined in, until all finished with one swift "Ghur-r-r—yap!" that struck eery echoes from the silent places and was no more.

"You damn fool!" muttered Barr, rubbing his mitten against his hood to wipe the sweat from his brow. "To let a wolf-howl get your goat like that! Buck up here and get ready to lam the spots out of that Montenay!"

With an effort he shook the chill from his heart and became himself again, alert and self-contained as he swung forward on the trail, exchanging no word with Nichemus.

When he knew that they must have covered five miles, he was puzzled; Niska had said that Crazy Bear was five miles ahead, but they had seen no sign of life. A few moments later, however, they crossed another narrow tongue of ice, showing that they were still near the lake, and came to a deserted, fire-less camping- place.

Radison took the broad trail that went on ahead, and Nichemus merely grunted his assent, so he concluded that Montenay was waiting for them farther on. The breed made no effort at concealment now, but came steadily along.

Suddenly he growled out a word of warning, swept around and took the lead. Five minutes later he flung up a hand, and upon reaching his side Radison halted, to stare in amazement at the scene before them.

They stood on the brow of a little declivity. A dozen feet below, and twice as many away, was a clump of figures with two dog-sleds. Montenay's huge fur hood rose high over the rest, and his deep voice reached Radison in a rumble of sound that had no meaning, for it was evidently the Chipewa tongue.

Though their arrival must have been heard, not a figure stirred save among the dogs, who uttered one or two yaps as they scented the stranger.

Suddenly Montenay flung up his arms and broke out into English, his rime-whitened tangle of beard thrown upward.

"O Spirits of the Dead, Watchers of the King, prosper me your servant this night! Even as the Silent Ones who sit yonder, you, their spirits, hear me! Let the prophecy be vain for this time, O Dead!"

A startled gasp broke from the group below. As if answering Montenay, one vivid arrow of crimson leaped up to the zenith and was gone, the green and purple fires playing as before in its place.

Suddenly Radison felt a nudge, saw that the Chipewas had broken apart, and in utter bewilderment at what he had seen and heard he strode forward to meet Montenay, who had turned to greet him with outstretched hand.

"So, Radisson, ye had to come?"

The American gripped the other's hand, feeling that the spell of the thing had rendered him powerless to resist. But there was no animosity in the face of Montenay; rather, the great eyes were filled with a mingled eagerness and strange wistful longing, and his hand held that of Radison for a tense minute.

"I'd like to know what warrant you had for taking me prisoner," returned Barr quietly.

"Warrant? Why—but that can come later. I need you, Radisson—I wanted ye to be with me, to grip and grip, share and share with me. Man, but I like ye fine! Tell me, what brought you up here?"

"I don't think this is any place to discuss our business," rejoined Radison decisively. "You might send out for Macklin and—"

"None o' them go with me this night! Tell me, was it the Silent Ones called you here?"

"Silent Ones?" Radison repeated the words, puzzled. "If you must have it, we came up here to trace a number of silver fox—"

"Ho, ho!" Montenay threw back his head in a great laugh. "It was the pelts, eh? Lord bless me, but I'm a fool! That's what comes to a man when he gets fear into his bones, Radisson; I've been fearing that you'd come for a year past, but now you're here—I want ye for a friend."

Radison looked at him in silence. Mad as the words seemed, Montenay's voice and aspect were certainly sane enough. He decided that it would be folly to provoke the man, but he had no mind for meek acquiescence.

"I don't pretend to understand what you're driving at; but, as I have no reason to bear animosity against you, I don't see why there should be any between us. None the less, I can't go off and leave my party this way."

"They'll know what's happened, never fear," chuckled the other. "But before they pick up the trail we'll be miles away. Ye'll go with me, Radisson? Come, have sense, man! Of course ye don't know the Silent Ones—pray God you never will, for they're a fearsome sight! Don't make me use force on ye, to-night of all nights—but say ye'll go!"

Barr glanced around at the dark faces, and knew that whatever this weird greeting meant, there was, at least, the right of might behind the appeal. And on the instant something in the big man seemed to draw him—some lonely grip that reached out and conquered him in its wistfulness.

"I'll go," he said simply.

"GOOD!"

Montenay turned with a sharp order. The dogs began to snarl in wild confusion, the loaded snake-whips trailed out their thirty- foot lashes and restored order, and a moment later the ten Chipewas, headed by Nichemus, took the trail. Montenay and Barr followed, side by side.

The American regretted his decision almost instantly, but it was too late now. Suddenly he turned to the other, remembering that shot across the snow.

"Was it by your orders that Nichemus fired on us and killed a dog, Montenay?"

"No, it was not on you that he fired, friend Radisson. He has borne a grudge against Uchichak for a long time."

"Well, a thing like that won't go unpunished—"

"Tut, tut!" Montenay interrupted with great good humor that nothing could shake. "Nothing but firewater can interfere with an Injun's feud, Radisson," for so he always used the name. "He saw his chance, and took it, which is Injun nature."

Barr fell silent for a little, his mind reverting to Montenay's earlier words. Why had the man feared his coming for a year past, and who were the Silent Ones? And what did "to-night of all nights" signify?

Where they were bound for he had not the slightest idea, nor could he imagine why Montenay was so evidently anxious to have his friendship. The whole affair was a tremendously vexing puzzle, with no solution in sight.

"Well, Mack will probably follow us," he thought, "and I guess he can take care of himself. Besides, Uchichak's men will be along before many days."

He had not been given his rifle, which Nichemus still carried, and he put a curt request for it to Montenay. The other slapped him on the shoulder with a laugh.

"Not yet; not yet! Have patience, man; if all goes well with us, we'll have a little talk with Pierre and arrange things satisfactorily. If ye like, I may hand over everything to you and skip out for the South—'twill depend on Minebegonequay. First, we'll have to see what Pierre has to say about it, though."

"Pierre who?"

"Pierre Radisson, of course."

Radison stared for a second, but Montenay seemed to think little of the words. "A little talk with Pierre"—and this particular Pierre dead for two hundred years! What Noreen Murphy had to do with it, troubled Barr little.

Yet if Montenay were crazy, it would not explain his evident power. The odd belt that he wore over his capote instead of sash, like some symbol of authority, the pelts, the flintlock pistol—the whole thing seemed to have some mystery behind it. Straightway Barr decided that Montenay was not crazy; he was an immense brute of a man, whose mind might be a trifle warped, but he was plainly of birth and breeding.

"Time will show," concluded the American with a little shrug of resignation. "I suppose we're going to get his sweetheart, as McShayne thought. I wonder what on earth ever got him started on this Pierre Radisson stuff?"

He recalled the story of the old explorer—how, deserted and betrayed on every hand, the man who had opened all the North and West to trade suddenly disappeared. Whether he had died in broken poverty; whether he had made his way back to his ancient friends the Mohawks; whether he had borne up once more for the great bay where he had raided and pirated and made his name a terror, no one ever knew. Pierre Radisson had vanished, though his sons had come to the Detroit with Cadillac.

However, he was not greatly concerned with a two-hundred-year- old Canadian just at present. He knew that the party was keeping to the northeast, plunging through the heavy timber that skirted the long and crooked Wusap Lake, though they did not debouch upon the lake itself. Once the lonely, terrible wolf-cry shrilled through the trees far to their right, and Montenay turned with a smile.

"The cry of the kill, Radisson! This is the seventh year, and the wolves are bad to meet with."

Barr nodded. "Yes, the rabbits were pretty scarce as we came north. You don't know what that seven-year business is, I suppose?"

"No, nor any one else. Every seventh year, as sure as fate itself, the rabbits die off and there's no trapping them. It's bad for the animals who live on 'em, too. A queer country."

"Aren't you a Scotchman?" inquired Radison, something in the deep voice giving him the idea. He half expected Montenay to flare up, but the giant was in a jovial mood and merely laughed rumblingly, as one would laugh to a child's question.

"Aye, like enough, but no man is the master of Macferris Montenay now, bear that in mind. What I've won I'll keep—here, try this."

He pulled a flask from inside his capote, where the heat of his body kept the liquor from freezing, and passed it over. Radison was weary and cold, and unscrewing the cap he took a swallow of fiery liquid.

"Great Scott, man!" he gasped, handing it back quickly. "Where did you get such stuff as that? How old is it?"

"Ask the Silent Ones," gurgled Montenay. The drink seemed to change his mood abruptly, for he shot a dark glance at the American. "Don't get too curious, Radisson—it don't set well on a man o' your name."

The warning was enough, though Barr had never tasted such liquor as that in all his life. Warmed and heartened by the few drops he had swallowed, he plodded ahead with new energy.

It irritated him that Montenay persistently stuck to the French form of his name, but he kept his thoughts to himself, for a word seemed to set the giant off when liquor was in him.

A wild conjecture flitted through his brain—a thought that Montenay might, after all, have established a rude kingdom here in the Empty Places where no man was lord, that he might have brought the Chipewas under his rule by dint of religious frenzy, that he might have formed a confederacy which in future would cause trouble, as Macklin had guessed.

But the thought was too wild, too improbable. Neither Montenay nor any other man could do such a thing without the news being borne to the outer world, Barr knew well enough.

Suddenly the string of men ahead halted in a clump of spruce, and a little fire was built. While Nichemus was making tea, Radison flung himself down on one of the dog-sleds, which was empty save for a few furs, and stretched out to rest.

Montenay talked with his followers in their own tongue, and the American noticed that all carried muskets, while the giant himself bore a rifle. Whatever the purpose of the expedition was, it hardly seemed a wedding-party, he thought.

A cup of tea and some half-thawed pemmican was eaten in silence, Radison, receiving no less and no more than the rest, including Montenay himself. Since there seemed to be a good store of provision on the loaded sled, this careful portioning out the rations foreboded a long and hard trip ahead, it appeared.

A swift order from Montenay and all the men save Nichemus leaped up and got into their snowshoes, took their rifles and, without a word, filed off. Montenay turned to the startled Radison, who wondered what this new move meant.

"We'll be back in an hour, friend Nichemus will stay to keep ye company—eh, Jean?"

The breed, it seemed, was also a person of moods, for he flashed one sullen glance at Montenay and went on with his work of scraping the frost-rime from his capote. Before Radison could speak, the giant caught up his own rifle and was gone on the trail of the rest.

"Where are they off to, Nichemus?" queried the American.

Slowly the breed looked up and met his eyes. The thin, sensitive face was hard and set, and the eyes were wholly brutal now.

"To raise de hell, m'sieu. I t'ink me some one die, to- night."

"Well, I guess they're the ones can raise considerable Cain," and Radison got out his pipe, lighting it from an ember. "A pipe certainly does taste good when you light it from a fire!" he sighed contentedly. "By the way, where are we? Anywhere near Murphy's post?"

"Huh? How you know 'bout heem?"

The Indian was certainly uppermost in Jean Nichemus now, thought the other, as he noted the lowering, vindictive gaze of the man.

"Oh, I heard about it! Are we near the place?"

For answer Nichemus picked up his rifle, carried a brand twenty feet away, coolly built himself another fire, and settled down to watch. Radison flushed angrily at the action, then stretched out on his sled and fixed his eyes on the huskies. After the manner of their kind they lay motionless, asleep; but let him move a hand and every sharp eye would open the merest trifle.

There was silence for half an hour, and Barr was just dozing comfortably when a single sharp rifle-shot sounded clear and distinct, though from some distance. He sat up, startled, to see Nichemus on his feet.

"What was that—some one hunting?"

"Be quiet!" The breed turned a face on him that was like a snarling wolf's, and Radison was wide awake instantly. "He's be de king's wife, mebbe; we see ver' soon."

The king's wife! Was it possible that anything so romantic as an elopement was going on here amid the snows? Barr tried to picture Montenay making love, and chuckled. There was something wistful about the fellow, at times, but certainly nothing of the lover.

"Look here, Nichemus," he said good humoredly, "you aren't going to keep me from talking, anyhow. I suppose your friend the king is running off with the girl called Minebegonequay, isn't he? Loosen up, old man!"

Nichemus quietly strode over, his face working with passion, and faced Barr.

"Listen! By Goss, I say for be quiet, you be quiet! De debil he is raise' in me dis night, m'sieu—an' I t'ink I la'k for keel you w'en you make for talk!"

The hoarse words issued like a growl from the man, but Radison, still seated, laughed and stretched forth a hand.

"Give me your fist."

For an instant the other hesitated, then shifted his rifle and obeyed. Barr put all his force into the grip, and rose swiftly to his feet as Nichemus doubled up in pain. Kicking away the rifle, he caught the breed by the throat and bent him back across the dog-sled. So swiftly was it all done that before the rifle lay quiet on the snow, Barr was staring down into the distorted eyes, his weight holding Nichemus firmly against the sled.

"You fool!" he said slowly, grimly. "Do you think you can order me around like that? Talk of killing me—you! You raise all the devil you want to and I'll choke it out of you in mighty short order, Jean Nichemus! Now, get up and behave yourself."

He jerked the breed to his feet, half thinking to see the long knife flash out; but to his surprise Nichemus stood feeling his hand, a ghastly smile flitting across his face, his dark eyes looking steadily at Radison.

"M'sieu, s'pose dere be jus' one star on de sky, an' de night, she's be all de time; jus' dat one petite star, no more. Den s'pose God, he's put out his han' for take dat star an' make it dark—eh? Mebbe de debil he's be raise' in you, too."

He turned away abruptly, picked up his rifle, and crouched down by his fire. As Radison watched him, thinking that he understood, a flash of pity came into his heart.

"Poor devil!" he thought to himself. "I suppose this bunch brought him some bad news—his squaw dead, or something like that. I'll swear there was no fear in his eyes, though! Poor devil!"

He stared at the huddled figure reflectively, for there was a queer Latin strain in some of these French half-breeds, a strain that seemed oddly out of place here in the northland. Suddenly Barr turned with a start; a dark shadow was slipping through the trees, and even as Nichemus gained his feet one of the Chipewas ran up and tied on his snowshoes.

Then came another and another, all panting hard. Radison counted nine, then he felt his heart leap as the great form of Montenay loomed up, doubly huge. Over the giant's shoulder was flung a figure thickly wrapped in furs; he lowered it to the empty sled beside Radison, but no sign of life came from it. The American looked about for the tenth Chipewa—and then he saw that one of the men carried two guns.

"Where's your other man?" he inquired lightly. "Have a scrap?"

He started again, as Montenay looked up. The man's face was lit with a strange passion, and the black beard was stiff with frozen blood, lightly covered with white frost-rime.

"Aye, a bit of a scrap, Radison. Get your shoes on, man."

He obeyed without a murmur. The huskies were beaten into snarling submission and were quickly harnessed, then Nichemus swung away to break the trail, Montenay snapped out a deep "Mash! Mash!" and the march was on.

With mind awhirl Radison fell into line behind the giant; what was the meaning of this rapid march, this silent figure on the sled? Was it the tenth Chipewa, and had Montenay been foiled in his elopement?

But soon the American was too spent for wonder. He began to realize that he had hardly slept since leaving the fort, and the pace set by Nichemus was a cruel one; the monotonous thrust of the snowshoes was terrible, but he gave no sign of weakness, only clenching his teeth grimly with the determination to keep going until he dropped. He wished now that he had slept while alone with the breed.

The swift march continued only an hour, however. Then Montenay rasped out a growling order and the band halted, Nichemus stripping some bark and starting a fire.

Radison dropped in his tracks, but as he saw Montenay approach the sled his curiosity was greater than his weariness, and he pulled himself up on one elbow, watching. The giant threw off the bands of hide and pulled up the bundle of furs; an instant later Barr heard a startled cry as a face emerged from the furs.

Transfixed, he gazed as it lay on Montenay's arm—pale, with deep golden-red hair drifting out over the dark furs like lost strands of sunlight. Then the violet eyes met his, and their horror-struck look brought him to his feet, tired as he was.

Instantly he realized the whole thing. This was no elopement; this girl was no willing bride—but a captive, taken in primal fashion by this giant of the snows!

As he gained his feet he saw the violet eyes fixed on him in startled appeal. Beyond that first low cry, the girl had made no sound. Radison sprang to Montenay's side, not heeding Nichemus, who drew close at the movement.

"What is this deviltry?" he cried hoarsely, tugging at the giant's shoulder. The bearded, blood-flecked face was slowly upturned to his. "Who is this girl, Montenay?"

"My wife to be, so mind your own affairs," came the amazing response. Startled, Barr stared down at the pale face among the furs, but at the words it had flashed into a quick blaze of protest.

"No!" came the cry, as the girl's hands struck out to push Montenay away. "They stole into the house last night. Help me, help me!"

Radison forgot his weariness in a wild flame of rage, and with one quick snarl he sprang at Montenay. As he struck at the scowling face a foot tripped him and he rolled headlong; a dozen hands gripped and struck at him, but he broke free with one savage effort.

Gaining his knees, he sent blow after blow against the lithe, dark bodies which had hemmed him in. Fingers clutched at his neck, but he tore them away, struggling to his feet, silent in the grasp of the terrible battle-lust that was on him. Men were on his back, clinging to his arms and legs and shoulders, but still he dragged them slowly forward, every energy centered on reaching that scowling face above the sled.

One brave after another went down, reeling, staggering back before him; his fist crashed into the face of the Chipewa who clung to his knees; a kick freed him from another; and there, only a step ahead, was Montenay, who had risen to his feet in amazement at the struggle.

The fury was full on Radison now. He lunged forward with a yell of exultation and struck with his whole weight, his fist crashing into the tangle of blood-frozen beard.

He saw Montenay waver and go back, felt the great hands grip him as if they would crush shoulders and ribs together, and his fist thudded home again.

The grip loosened, and he felt a fierce delight at sight of his own torn, bleeding knuckles; then the sky seemed to fall on him and all things went from red to black.

Nichemus stood ready for a second stroke with his rifle clubbed, but there was no need, and Montenay regained his feet in time to hold him back. The pale face of the girl was once more buried among the dark furs, and for a space only the cracking whips and yelpings echoed through the trees, as the excited dogs were beaten into quiet.

Montenay stood over the American with a grim smile, then he rolled the body on its back and gazed down at the deadly pale features, on which the blood was already frozen. Suddenly he went to his knees, flung back the hood from Radison's head, and called Nichemus, while the others made camp.

Here the band rested two hours, and although Montenay attempted to revive Radison, the American remained as if dead. Finally he was tied on the sled which carried the provisions; Nichemus cracked his whip, and the dogs moved off to the east, followed by the Chipewas.

Behind, and a quarter-mile to one side, among the bushes on a hill, Macklin snapped his glasses together and turned to his companion.

"Whew! That was some fight Rad put up, chief! Who was the girl on the sled?"

The other nodded, his deep-set eyes burning.

"Napawew! He is a man! The girl is the white tobacco girl, my brother—Minebegonequay. Let us go to the small master's house and wait for news of my young men."

And save for the snakelike file of men that crept away to the northeast, the Empty Places were silent and deserted, while around the horizon hovered the sundogs, boding storm.