RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

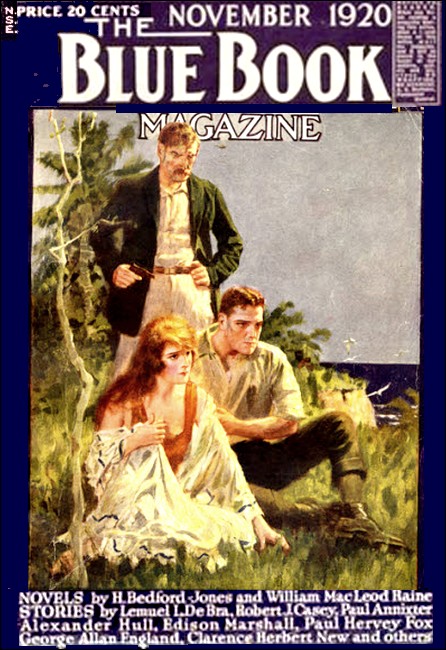

Blue Book Magazine, Nov 1920, with "The Second Life of Monsieur the Devil"

THE pool of sweet water glowed like a round bit of the sky, a round mirror that reflected the clear cerulean blue which the Ch'ien-lung artists hit exactly, and which the K'ang- hsi artists missed with their greenish tinge.

Fifty feet was the diameter of that circle. About it, on all sides save one, ran a thirty-foot strip of white sand, unstained and beautiful as snow. On the one side was stretched an awning of coral-striped canvas, warding the tropical sear of the burning sunlight. Behind this canvas, leading down to it, was an avenue of trees; a thick, green, shady avenue, carpeted with the same white sand, walled by the pineapple-like trunks and the interlaced pinnate fronds of the palms. Under this hot sun Phoenix canarensis throve mightily, and the avenue formed a corridor walled and roofed in green, through which the sun-rays pierced in a tiny lace-work of golden meshes, but robbed of all their strength and heat.

Round about this white sand circle rose a twenty-foot wall of weathered pink stucco. This circular wall was broken by many odd projections and ledges, over which had been trained climbing roses. Just now, the wall was a mass of rich pink foliage that shut out all the world—or seemed to. The only break in this wall was where the avenue of palms lay like a streak of greenish- black shadows pointing away from the pool. On the side opposite this break, was a gate in the wall, a gate as solid as the wall itself. Thus, within this wall was a little world, and the wall shut out all the horizon, and the sea, and those who might intrude upon the little world within.

Yet, in the back of Sigurd was a tiny space the size of a leaf where the magic blood of Fafnir had not touched; and by this tiny space came the hero to his death. Likewise in this wall was a gate, and in this gate, which was seldom opened, was a tiny keyhole. A single swimmer was disporting herself in the pool, making evident its depth by her long dives. She was no marvellous swimmer; still, she enjoyed this pool with the whole-hearted abandon of one who relaxes absolutely to the pleasure of the moment. Against the rippling blue of the water, her body glowed golden. A cap of yellow rubber bound her hair. Tired of swimming, she turned upon her back and floated idly, her figure half revealed, half hidden by the lapping wavelets, her eyes rapt upon the blue sky above. Staring thus into the depths of the sky-bowl, she lay motionless, and presently lost her poise in the water, as one will. Quietly her staring eyes went down under the fluid.

A splutter and cough, and her body flashed. She laughed at her own mischance, and struck out for the shore and the canvas awning. Behind the keyhole, in the gate, came a slight and insignificant flash; as it were, the flash of the sun upon a black and glittering eye which moved to follow her.

The girl came to the shore, and stood up. For a moment the sunlight bathed her figure, painting it a pure golden hue, vibrant and delicate of outline. Then one saw that she was clad in a skin-tight vesture of golden wool—a suit that clothed her slender shape like a glove, revealing every swelling outline, every exquisite curve and shape. Her bare feet splashed in the shallows, and she flung herself forward into the shade of the awning, gathering the warm white sand in about her hips.

For a space she sat there motionless, hands clasped about her knees, gazing at the sky and the pink wall and the blue pool. Suddenly she glanced at the empty avenue of shade, as though moved by some inward impulse. Her hand crept to the shoulder- strap that bound her vesture, and she unbuttoned it. One could easily comprehend the impulse, in this spot so shut away from all the world, to be free of all clinging garments and to plunge gloriously into that blue pool of the sky!

Her one shoulder bared, the girl suddenly paused. There had been no faintest sound, no stir of the warm and listless sunlight; yet she paused, her eyes roving about. One would have declared that she was startled by no physical thing, but by some spiritual intuition. Her gaze dwelt for an instant upon the gate opposite her. It was impossible that she should detect the minute glitter at the keyhole, yet slowly she buttoned the shoulder- strap again. A shrug of her shoulders and she stood up, plunged into the pool, and swam straight across it to the farther side. There she landed and walked up to the gate. She did not attempt to open this, but set her bare feet in the rough stucco and ascended the wall like a golden flame. Her head rose above the ornamented top of the wall; she clung there a moment, watching, a slight frown clouding her clear features.

No one was in sight.

Beyond the wall was ground, solidly sown with tight clusters of lipia-grass, like a greenish gray carpet. Here and there were set trees, in round places cleared of grass; mangoes, clad in massy pink blossom, their leaves like wine-hued ribbons; limes and oranges, scenting the air. A queer medley of trees, here! One or two flame-trees, blood-red in the sunlight, were mingled with the fat deep greenery of figs. And amid the mangoes was that tree with the most rare and wonderful of all tree perfumes, the Chinese magnolia, ivory petals ready to fall.

Around these trees one glimpsed a thick pomegranate hedge, while water ran in rivulets from some hidden source, following channels which seemed haphazard yet which were deeply grooved—the rains were long since over, and a little irrigation hurt nothing. A hundred feet distant, the land dropped sharply away in a thin, sword-like line, and beyond it appeared the sea-horizon. That drop was very abrupt and startling. There was no shore; nothing, in fact, but fifty feet of cliff, with the ocean at the bottom. A strange place, this, beneath the tropic sun!

The girl beheld no living thing in sight, although many men might have lain concealed there before her; and one, in fact, did so lie. She dropped back from the wall into the white sand, swam across the pool again, and came to land. Beneath the awning, she picked up a robe of gossamer silk, wrapped it about her shoulders, and walked up the shady avenue of palms. The frown had vanished from her face, and she sang light-heartedly as she walked.

IN the garden orchard over which she had just gazed, the brown

figure of a man arose from the thick hedge. This man had some

excuse for hiding himself, since he was stark naked. The sun had

burned him much. Over his head was a thatch of dark red hair,

white with brine from the sea-water. His face was flat, broad,

powerful without being refined; the black eyes glittering beneath

dark reddish brows were alight with an incredible intelligence

and energy. His body was bony from hunger and suffering, drawn by

long immersion in water, yet very muscular.

This man crept to the gate in the wall and peered through the keyhole. He rose again, a grin upon his lips, and hastened to the nearest rivulet of water. He flung himself down and drank thirstily. Rising, he drew his hand over his lips and glanced at the sun.

"Nine o'clock!" he muttered. "All morning climbing that cliff!"

He cast a malevolent glance toward the cliff and the horizon. Something in his words, in his look, in his appearance, conveyed the idea that he had come out of the sea below and was now exulting over it in a fiercely triumphant hatred. Yet, to have come from the sea, he must have come from some other land—and there was no other land in sight. When he turned about, one saw that over his naked back, like grids, ran the faint meshes of scars that could have come only from many whippings under the lash. When he walked, it was seen that to a very slight degree "il claudiquait," as the French say—he showed that he had trailed ball and chain behind him.

On one side of him was that cliff. On two sides were pomegranate hedges, behind which appeared rank tropic shrubbery, with no semblance of order. The irrigating water was a constant seep from the swimming pool, which was therefore fed by under- ground springs.

On the fourth side was the wall, and to this the man turned. He tried to open the locked gate, but its massive strength resisted him. He tried to climb the wall, but fell back and lay in the sand, exhausted by the slight effort.

"Done up!" he muttered. Suddenly his eyes shone.

"There must be a house, eh? Then there must be boats. Done up? Not yet!"

He came to his feet and laughed. That laugh was an effort of the will. He went to the wall, covered on the outside with roses, and searched among these vines. Presently an exclamation of satisfaction broke from him. He stood erect, holding a bit of wire which had been used to fasten the original vines in place. With this wire he went again to the gate, and stooped to the keyhole. In two minutes he touched the gate and it swung open.

He stepped through, closed the gate carefully, and flung himself toward the pool of fresh water, and the avenue of shading palms beyond.

MEANTIME, at the other end of this avenue of palms, was being

enacted a quaint idyll in the frailty of human nature and one's

affectionate regard for the muse of science. Who was this muse of

ethnologic philosophy, by the way? I, for one, do not know. Yet

it is high time that she were tracked down, discovered, named; in

these latter days she has many devotees. It is to be doubted if

she had any more faithful devotee, however, than Jean Marie

Auguste des Gachons.

Once upon a time, and not so very long since, Des Gachons had been a high official in that great colonial realm of France which began with an expedition into Indo-China, reached out grasping fingers until Cambodia on the south and Tonkin on the north were enclosed, stretched forth a thumb into Siam and a little finger into Yunnan, and gripped at an empire. A high official in this empire has many chances at wealth, and Des Gachons thoughtfully neglected none of them. He was a gentle soul, hating the army and colonial politics. When his wife died, and his brother was killed in Tonkin, Des Gachons took his pile and withdrew to devote his life to science and his daughter. And, one must admit, he had chosen a very pretty place for his devotions.

Here was an island, where he reigned as absolute monarch and owner. Crowning this little island, he had built a great rambling house in French Colonial style, where he dwelt with his daughter and his two secretaries, his French gardener, his French chef and boatman, his native servants. Here he was a little emperor, and here he could grow fat and wise in perfect bliss.

Berangère, having dressed after her swim, sought this father of hers. She turned from the wide, shaded colonnade before the house, and passed into the sunken gardens. Here, now that the rains had subsided, Des Gachons had transferred his library and his atelier, into the open air.

The girl paused at sight of the scene which greeted her, a light smile touching her lips. A small amphitheatre had been planted with limes and Chinese magnolias. These trees had been trimmed very high, so that they formed a shady roof over the place—a roof from which was wafted the rarest of perfumes. Below were tables, typewriters, Singapore chairs, a huge round gong to summon servants.

Here sat Des Gachons. He was a great fat man, dreamy of eye, tender of heart, his beard trimmed into two long prongs. He was very vain of this beard, which, in conjunction with his elaborately curled moustaches, gave him the deceptive appearance of a very Porthos. The desk beside him was littered with papers and note-books. At a portable bookcase one young man was diligently searching for some item. Another young man was seated, taking in shorthand the stream of wisdom which flowed from the master's lips. These two secretaries, naturally, were desperately in love with Berangère, and might as well have been in love with the moon for all the good it did them.

At sight of his daughter, Des Gachons struggled to his feet and bowed. He kissed her cheeks, and the two young men trembled. She dutifully kissed his cheeks, and the two secretaries turned pale. They bowed profoundly as she directed smiling greetings toward them.

"Mon père," she said, allowing Des Gachons to reseat himself and draw her upon his knee, "I must go to Saigon again, at once!"

The big man's brows uplifted in Gallic astonishment.

"So soon, Bergeronnette? So soon, when we have just returned to our charming home after spending the entire season of the rains in that little Paris—"

"Exactly," said the girl. "You see, all six of those frocks I had made, are absolutely impossible! I ordered the sleeves very short, to conform with the newest modes—after cabling to Paris in the matter, too!—and that assassin of a modiste has made them too long! So I must go and attend to it."

Des Gachons grimaced uncomfortably. "But, my tender little shepherd-girl," he said, lingering on the diminutive of her name, "but Bergeronnette, you perceive that I must finish this paper—"

Her shoulders lifted in a shrug. "Tiens, donc! I am not going to interfere, mon père. I shall take old Paul, who keeps your fleet in order, and we may have the small cruiser, is it not? Three days, and we shall be in Saigon. A week there, and we return."

"Oh, if you insist! I shall have to go—"

"I refuse to permit it! Am I a child, then? Am I a silly little thing?"

"The good God knows you are not!" Des Gachons stifled a sigh. "But—"

"Never mind the rest." The girl stooped and planted a swift kiss upon his cheek. "Then we shall leave tonight—"

"If you will wait but two days," said Des Gachons, with the air of one who is resigned to the inevitable, "I shall have this paper completed, ready for you to mail from Saigon. It must reach the Révue Archéologique at the earliest date, for it completely refutes certain theories of the great Pelliot in the Bulletin de—"

"Very well," cut in the girl. "Very well. In three days, to give you an extra day of grace! Now I shall not interfere further with your work."

She withdrew. Des Gachons gazed after her with another of his heavy sighs. The two secretaries echoed the sigh.

"Should she go thus, unaccompanied?" ventured one of them, a mournful hope in his voice. Des Gachons darted a look at the speaker, then smiled dryly.

"Mon brave, when you can take care of yourself as well as this girl—nom d'un nom! I would like to see the man who can handle her! Heaven knows I cannot. Now, where did we leave off with those quotations—"

He resumed his work.

Berangère, meantime, followed a cement walk that led from the house amid its bowers of green; she descended this walk to its precipitous end. She came out upon a small terrace. Directly below her, at some thirty feet, was a small, perfectly enclosed harbor. At the edge of this harbor were boat houses. Anchored in the little port were a large motor cruiser, a smaller and faster model exactly like it, a schooner, tiny in size but perfect in detail. On the sand were a number of whale-boats.

The girl touched a lever at the edge of the cliff, and brought into view an escalier which was moved by an ingenious arrangement of counterbalanced weights. She stepped on to this and set it in motion. It deposited her upon the shore beneath, and from the boat houses appeared an old man wearing a Breton cap, who saluted her respectfully. Berangère danced up to him and kissed his brown cheek.

"In three days, Paul, we go to Saigon, you and I—with the little cruiser!"

"Ciel!" exclaimed the old seaman. "But—"

"Pas un mot, Paul!" exclaimed the girl. "Not a word! And listen: you know that papa was expecting a consignment of brandies from America? We shall bring them back, as a surprise!"

"Heaven knows," said Paul, with the grumbling air of one who is privileged, "there is a cellar full of liquor up above now! An army could not drink it all."

"Bah! If it pleases Papa, why not? He says that when all the world has gone dry, this island shall be an asylum for the next thousand years! In three days, remember!"

Paul nodded.

Neither the old Breton nor the girl perceived a slight movement upon the crest of the cliff above, nor the imperceptible glitter of a flashing eye.

Upon the following day, old Paul reported that one of the whaleboats had vanished from the lagoon. No one was missing from the island. The thing was inexplicable, unless the boat had been laid up too low on the shore, and had washed out with the tide. So, they concluded, it must have done.

SAIGON is a city consciously modelled, in general plan, buildings, streets and customs, upon Paris—that is to say, upon the Paris of a generation ago. One may find much in Saigon that is supposedly forgotten in Paris—even to very bad French.

For example, there is a certain Cabaret du Chat Gris, located in the lower part of the city, convenient to the wharfs and railroad and the Arroyo Chinois. Here, for a few cents, one may drink from divers fountains of evil. Here, for a few dollars, one may disappear forever. The cents largely predominate, naturally.

Five men were sitting about a table in the Gray Cat, fingering a greasy deck of cards and drinking execrable red wine. Le Brisetout was a huge uncouth monster of hair and flesh who worked in the nearby abattoir. L'Étoile, a fiery little devil of a man, wore a green patch over one eye; the other orb blazed like a star of green fire. Le Morpion was a human bulldog, bulging of brow and chin, a retired seaman whose hands were knotted and lumpy, and whose glittering little eyes were extremely dangerous.

The fourth man was different. He had come of a finer strain; even in his poverty and dirt he retained a certain grace, a certain debonnaire scoundrelism. His beard was somewhat trimmed, and one conjectured that he might have been a gentleman. His weary and dissipated features held a lingering suspicion of having once been handsome. He had the peculiar skin of one who eats opium, which was not intended by the Creator to be eaten by white men.

The fifth man was dissimilar to all these four.

Like them, he was ragged, unkempt, prone to vicious words. His unshaven features were bony and rugged, his gray eyes were bloodshot. Unlike these others, he was neither French nor of mixed blood, but an American. He had drifted into Saigon, broke, and was working as a labourer at the Quai François Garnier.

Aside from these five at the table, two other persons were in the room. One was the proprietor, who was reading a newspaper across the bar. The other was a man with a dirty bandage about his jaw. He had entered, demanding wine and "de quoi écrire," and sat at a table in a dark corner. Here, however, he wrote only briefly. He mainly watched the five gamesters and sucked at a long cheroot hungrily, as though drinking the nicotine into his very soul after long abstinence.

"Now, as for me," said L'Étiole in crisp argot, "I have been at honest work for six months—Laugh, fools, laugh! But it is true. When they took M. le Diable, and sent him to Noumea, I swore that I would turn to honest work until he escaped."

"Bah!" said Curel, he who might once have been a gentleman. "One does not escape from Noumea!"

"Exactly." Le Brisetout reached out hairy paws for the cards. "One does not! I know, for I have been there, me!"

There was a laugh. Smith, the American, looked up. "Who is this M. le Diable? I've heard you speak of him, but—"

"Yes!" Le Brisetout mouthed an oath. "Who is he, you? We know him not, in Saigon."

L'Étiole looked at Le Morpion. Between these two men passed a glance of singular meaning. It was Le Morpion who answered, as though in that glance he had read a command.

"Monsieur the Devil? Why, he is Monsieur the Devil—that is all! He is the king of all good rascals and honest thieves. They say that he was an artist, a man of talent, and that something happened to him. You know the crazy artists who lived on Tahiti for years? Something of the sort. At all events, one night in Shanghai—croque! And they had him. They brought him down here for trial and sent him to Noumea for life, the dogs! It was a betrayal."

"Yes," said L'Étiole with a certain mournful satisfaction, "it was a betrayal. But the man who betrayed us—I mean the man who betrayed him—confound this wine, it thickens the tongue!—Well, that man died very suddenly the next day."

"Good enough," put in Curel languidly. "I hope this M. le Diable escapes. I have heard of him. I would like to meet him. I think that he might break the monotony of life's facts."

Le Brisetout glared at the speaker in scorn. "Escape? Bah!" he roared. "No one can escape from Noumea! All around in the hills are brown devils, armed with clubs shaped like—like—well, you know what, you! When one escapes, they beat him nearly to death, then drag him back. And, besides, one cannot swim a hundred miles."

"Ah! But M. le Diable can," said L'Étiole with conviction.

"Certainly he can," said the American. "I can myself. At least, if it were a question of escape from that hell, Noumea!"

The eyes of the bandaged man in the corner dwelt curiously on the face of Smith.

The cards were dealt. The five men fell to their game. Presently it was over, and Curel gathered in the pack. Le Brisetout stretched out one hairy, mammoth paw.

"A hundred miles!" he said, as though recollecting the former train of speech. "Ah! That is clearly impossible, M. Smith!"

Curel's voice cut in, a bit dreamily.

"I should like to meet this M. le Diable!" he reflected aloud. "Decidedly, the monotony of life is a fearful thing. The facts of life—you apprehend! One desires to get away from facts. How pleasant to be a Bolshevik and abolish all fact!"

L'Étiole, adjusting his green patch, laughed softly. That laugh was like the snicker of steel on steel.

"If you ever meet M. le Diable," he responded, "you will have no more monotony, my gentleman! As for your facts of life, I know nothing about them. You should have known our M. le Diable—a true artist! No gutter pickings for him. 'Cré nom!"

"He was an Apache, perhaps?" queried Curel, dealing.

"Devil take me if I know," said L'Étiole frankly. "He spoke all tongues, had been all places. I have thought at times he might be American or English. One hardly asks him questions."

"I wish to hell he'd show up here, then," said Smith roughly. "If I could get away from this cursed town, I'd sell myself to the devil, man or fiend!"

Suddenly the voice of Le Brisetout boomed forth upon them.

"I say it is impossible!"

Smith looked at him. "What now, hairy ape?"

"To swim a hundred miles is impossible!" Rage flooded into the brutish features. "The man who says so lies, and is a—"

The epithet fell. Instantly Smith's arm flashed across the table and his fist struck Le Brisetout a blow which would have staggered any other human being. This human gorilla, however, only mouthed a curse and flung himself forward. His two immense, hairy paws gripped Smith by the throat. The table was hurled aside in the encounter.

Le Brisetout stood up, still gripping Smith by the throat, and shook him savagely. Then, with swift precision, the hands of the American crept upward. Each hand gripped a little finger of Le Brisetout. Smith gave a sudden heave of his shoulders and arms.

From the hairy giant burst a hoarse cry of agony. He flung his two hands about in the air, tried confusedly to wring them, cried out anew. Smith seized him by the shoulder and kicked him toward the door. Le Brisetout vanished in the street outside, whimpering and groaning. His two little fingers had been broken.

The proprietor turned his uninterested gaze to his newspaper again.

Smith rejoined his companions, laughing easily at their astonishment. Curel put forth a hand to him, with a gesture of pride. Caste, after all, does assert itself.

"Congratulations! It was well done, that; I am glad to be rid of the brute."

Smith nodded, then glanced at the other two.

"You are not his friends?"

L'Étiole shrugged disdainfully, Le Morpion shook his bulging head.

"His friends? Hardly, my American! M. Curel was dealing, I believe?"

Smith bent to pick up the table. Suddenly L'Étiole, who was glancing at the bandaged man in the corner, turned pale as a ghost. This man had made an almost imperceptible gesture.

The bandaged man made another gesture, this time toward the proprietor—evidently asking if the latter were to be trusted. The jaw of L'Étiole fell. His pallor deepened, but he nodded assent.

From his seat in the corner rose the bandaged man, and stepped forward. He removed his wide hat, to uncover a shock of reddish hair. With a deft motion, he unwound the bandage from about his face. Le Morpion uttered one choking, inarticulate cry, and staggered back as from some awful apparition.

"M'soo—m'soo—"

"M. the Devil," said the stranger, bowing. "Messieurs, good evening!"

All four stood staring blankly at him. Smith glanced at the two rogues. In their stricken faces he read amazed recognition. It was impossible to doubt that the man before them was the same of whom they had been speaking.

The proprietor quietly came from behind his bar, locked the door, and returned to his newspaper. He was, obviously, a discreet individual.

The silence continued. Smith was well aware of the audacity of this appearance, here in Saigon, the very hub and headquarters of French authority! This M. le Diable would be hunted like a wild beast the instant his escape became known, the instant his presence was suspected!

"When one swims a hundred miles," and M. le Diable smiled at Smith as though reading his thoughts, "one is naturally given up for dead! And I think," he added reflectively, "that it was something more than a hundred. Of course, I had assistance at first—a preserver lost from some ship. Providence must have sent it to me—or perhaps my namesake! Yes, decidedly, it must have been my namesake."

Curel bowed, a trifle mockingly, and spoke in cultured accents.

"Perhaps it is desired that I withdraw? One gathers that M. Smith and I may find ourselves de trop—"

"On the contrary," responded the other, in equally pure French, "I should be greatly pleased to cultivate your acquaintance, gentlemen."

Smith picked up the table and set it on its feet.

"The pleasure is mutual," he said. "Suppose we sit down."

Le Morpion and L'Étiole dropped into their chairs, still staring at this individual who had come from the dead—or worse, from Noumea! M. le Diable seated himself. Under his thatch of reddish hair, glittered his black eyes. His broad, powerful features were filled with virile energy. He quite ignored his two former followers, and gave his attention to Curel and Smith. The bandage must have served him only as a disguise, for he was quite uninjured.

He spoke in English.

"I am glad we met. These two friends do not understand us, so speak freely," he said. His voice was level and poised, a voice of refinement and deadly reserve strength. "You first, M. Curel. From your recent conversation, I gather that you are wearied by the monotony of facts. And yet there must be some reason for that boredom, and for your presence here—"

Curel laughed. From his pocket he took a tiny box of opium pellets and laid it before him.

"The reason, M. le Diable? Behold it! In the days of my youth, I was given to liquor. I learned that one who took opium, entertained an aversion to liquor. Hence, to cure myself, I began to take opium in the form of pills. True, the liquor habit was cured; yet—"

M. le Diable threw back his head in a burst of hearty laughter.

"Come, this is rich!" he exclaimed, in tones which would have led Smith unhesitatingly to pronounce him an American. "Devil take me, but this is rich! One overcomes absinthe in order to become an opium fiend! Well, M. Curel, I believe you. This little incident of your career is one of those things which, although perfectly true, would appear incredible to most people.

"If I guarantee to relieve you from the monotony of facts, and place before you an adventure in which no sane man could believe, will you join me?"

"With all my heart," answered Curel.

"Agreed." Mr. Devil turned to the American.

"Well, sir? How come you here?"

Smith rolled a cigarette and surveyed his interlocutor whimsically.

"What is this, some Arabian Nights affair? If you want any facts from me, come across with some yourself, first."

"This is droll!" said the other, smiling. His smile betrayed vividly white teeth, queerly pointed, not unlike the teeth of those Africans who file their incisors to sharp points. His laugh was gay and infectious.

"Droll! One man shrinks from facts; the other demands them!"

Suddenly he fell serious. "I might say that, before my somewhat enforced visit to Noumea, I instructed L'Étiole, who is a faithful soul, to await me at this place and to have with him two or three others. That you are here, is a recommendation, I assure you."

"Your assurance is a compliment," said Smith politely. "Who are you?"

Again the other smiled.

"What, still more insistence upon facts? My dear sir, you show little toleration of the modesty which M. Curel shows in the face of these naked facts! I presume you desire a name for me. Well, it would be convenient to have a name, I admit. Therefore I take the name of Lebrun, to be in harmony with the majority. A few moments ago you declared that you would sell yourself to the devil, my Faustus junior. Have a care! Such an invocation may well become an application!"

Curel interposed with a whimsical word.

"This goes well, M. le Diable, I assure you! We are certainly departing from all prosaic facts. I trust you do not claim to be the devil in person?"

"Some have thought so," responded Lebrun. His black eyes flashed with sombre fire. "Have you any doubts in the matter, M. Curel?"

The other shrugged. "I? Ma foi, none! I am satisfied."

"Then, pray, do not interrupt." Lebrun turned to Smith. "Come! Yes or no?"

"To what?" drawled the American.

"To an alliance."

"Yes, if you like."

"Agreed. What brought you here?"

Smith puffed at his cigarette. "My feet in the first instance," and he grinned. "In the second, lack of money. In the third, the interference of the police in my affairs."

"Ah!" Lebrun regarded him with satisfaction.

"You are wanted?"

"Very badly wanted," said Smith.

"Shall you have a little money now—"

"I?" Smith shrugged his shoulders. "Oh, I have plenty!"

"The devil! But you just said the lack of money brought you here—"

Smith grinned at him. "Sure! The lack, you see, made me obtain some; the obtaining it, made me take to my heels; taking to my heels brought me here. Once here, I found it hard to get away. So I am working on the docks until my chance comes to slip aboard a ship."

"The police here are seeking you?"

"I don't know. In Tonkin, up north, they certainly are."

"Very well, gentlemen." M. le Diable assumed an air of business. "My usual custom is to take one-half the proceeds of our business, and to divide the other half among those who aid me. There will be you four, and a fifth, a lady. No more. Is this satisfactory?"

Both Smith and Curel indicated their assent. Lebrun turned to L'Étiole and Le Morpion, and changed his tongue to the argot they spoke.

"Do you remember, you, the name of the excellent gentleman who sentenced me to spend the rest of my life in Noumea?"

L'Étiole, by far the more adroit of the two rascals, made prompt reply.

"It was Des Gachons—his approval of the papers was almost his last official act. We have often regretted that he left the country before we could interview him."

"It is just as well." Lebrun smiled grimly. "Do you know where he is?"

"No."

"But I do." He rose. "Come with me. You others follow, but not too closely."

All five of them politely bade the proprietor good night, and issued forth into the street. Smith and Curel were the last to leave. In obedience to the orders of Lebrun, they waited in order to give the other three a slight lead.

At this instant, the American felt his companion touch his arm significantly.

"Damnably clever!" said Curel in English.

"Eh?" Smith glanced at him. "What do you mean?"

"Nothing. Only that I happen to recognize you. I remember you now."

Smith laughed. "So? I'm afraid you are mistaken."

"As you like. Only, I am very sure that I saw you two months ago, in Hué City, under somewhat different circumstances than these."

Smith started. "The deuce you did! Then—"

"My dear Smith," and Curel laughed softly, "why be alarmed? My interest in such a game as this gives me something to live for. Two hours ago, I strongly contemplated suicide. Now, I am eager, full of the joie de vivre!"

"I congratulate you," said Smith dryly. "None the less, I fear you are mistaken."

"As you prefer. But I bear by right a 'de' before my name. My ancestor rode to Egypt with Joinville. I think you are no longer alarmed concerning what I know?"

"I never have been," said Smith cheerfully. "One may be surprised, but not alarmed. Only, if you hinted it to Lebrun—"

"It would make trouble?"

"For Lebrun, perhaps."

Curel laughed heartily. "You have an astonishing self- confidence! But I shall say nothing of it. I repeat, the game interests me. I have never delved deeply into crime, but now I am grateful for the opportunity. It will be absorbing! You have my promise."

"Your word's good with me. Come along—I don't want to lose the others!"

The two started after their companions.

WHEN Berangère des Gachons arrived at Saigon, the government had departed for Hanoi for their six-months' residence in the north, and she had the southern capital pretty much to her own sweet self. She made the most of it.

No longer was the absence of "the court" regretted, no longer was the pleasant city dull and lifeless. The Rue Catinat picked up in business, and the Boulevard Norodom witnessed the amazing sight of government clerks hastening to work and hastening away. In effect, Berangère not only demoralized the Palais, but the city itself. Brought up in official life, she had no awe of the chiefs of bureau, and if she wanted a trifle of help in a customs affair or any such petty detail, she came straight to the Palais du Gouvernement and cut the red tape.

Berangère was apt to be impetuous, although it must be admitted that she had a way of converting over-hasty impulses into triumphs on the approach of disaster. It had occurred to her that if she provided another objective for the sheep's-eyes of the two secretaries at home, she might save herself a good deal of annoyance. Accordingly, on the second day of her visit, there appeared in L'Opinion an advertisement which stated that she desired a maid. Many maids, Eurasian, French and native, sought admission to her rooms at the Continental, but none were chosen. At length appeared Félice Bonnard.

It was morning when this application came.

Berangère had breakfasted in her room. She was arrayed in a robe de chambre of gorgeous deep yellow, with boudoir cap to match; she had a penchant for this hue, which well set off her own golden yellow hair, her deep blue eyes, her vivacity of colour. When Félice entered, she perceived at once that she had found her maid.

This Félice was a woman of twenty-odd, very chic, a decided brunette. Her mournful dark eyes held a fund of experience. They were dangerous, those eyes. They marked their owner as one who knew much of the world from varied angles. Her dress betrayed remnants of taste—real worth fallen upon days of poverty. Berangère saw before her what would be termed in England a "gentlewoman in reduced circumstances."

"Ah!" she exclaimed, motioning to a chair. "You are not exactly the type one would expect to see, Mademoiselle."

"Madame," corrected Félice, smiling a little. Her smile was most attractive. "Madame Bonnard, Mademoiselle. My husband was an officer in the army, and was killed at Verdun. We had been married only three months. After that, I nursed. At length I heard of a fine opening here, and came. Now I am in trouble with the authorities, because they do not wish nurses and since I have no family they say I must go back to France. The opening did not develop. I have no money and no friends. If I could get a position of any sort—"

"Listen," said Berangère. "I wish a maid, you comprehend? You have pride—"

"When one has nursed the poilus, Mademoiselle, one has no pride; that is, no pride in the old sense. Only pride that one has been of service."

Well, that was a good answer. It captivated Berangère. She perceived that this woman would have the two secretaries fighting a duel within a fortnight.

"I live on an island," she said. "There is little companionship. You will be lonely. We spend the rainy season each year here in Saigon. For the remainder of the time, we live on the island by ourselves. We have few visitors, no social life. Consider!"

Félice smiled. "Mademoiselle, I have much to forget."

Berangère nodded and rose. "Come back this afternoon at three."

WHEN her visitor had departed, Berangère dressed and summoned

a riksha. She was whirled out the Boulevard Norodom to the

palace, and there impressed an eager and attentive clerk into

service.

She started a train of inquiries that took them to the Commissariat Central, then down to the Customs and Revenue office on the quay, and finally ended at the government office in the Rue Lagrandière. Here a smiling official spread before the young lady a dossier which related to the Veuve Bonnard.

"But," said Berangère, "there is then nothing wrong with her?"

The official spread his hands. "Nothing. But we do not care to have young women come out here alone and without expectancies. In Algeria, you comprehend, that has been done with very unfortunate circumstances—for the young women. And here we are taking much caution and no chances."

"Tut!" broke in the girl swiftly. "If I engage her, all is well?"

"Of a certainty. Still, as you may see, one knows little about her. It is true that she was given the Croix for her hospital work under fire. But the Croix has gone to Apaches who served la patrie. It might be well to wait, to cable home and inquire—"

"Nonsense!" declared Berangère calmly. "I shall engage her."

As she spoke, her eye fell upon a paper which lay on the desk of the official. She reached over and picked it up. "What is this? There is a handsome man, monsieur! Tiens—one thousand dollars! What has he done, then, to be worth so much to the government?"

The other shrugged. "Mademoiselle, I do not know. Me, I know nothing of it. The paper came in the official mail from Hanoi, this morning."

Berangère frowned. "An American and a criminal! This is singular."

The paper in her hand was one which bore the enlarged picture of a man—not a bad-looking fellow, excellently dressed. The face was full of possibilities. It was a bronzed and rugged face, anything but handsome from the oily and moustached French colonial standard of masculine beauty; a keen and incisive face, rather good-humoured and very calm.

Beneath this picture was the name, "J. Hudson Smith. American," followed by the information that the governor general would pay one thousand piasters—locally termed dollars—for information of his whereabouts. It was an unusual thing, this circular; the police seldom follow such a system of advertising.

"I shall keep this," said Berangère coolly. "Somewhere I have seen this man; whether lately or long ago, I cannot say. But perhaps I shall gain the reward, eh?"

"Could Mademoiselle have the cruelty to deliver a poor wretch of a man to justice?"

She laughed gaily. "That remains to be seen! He must first be found."

Returning to her hotel, Berangère laid the circular upon her table and forgot it temporarily. In the course of the afternoon, Félice Bonnard appeared, was promptly engaged, and was given enough money to supply herself with a modest wardrobe. Berangère dined out, and attended a band concert in the Jardin Botanique, followed by an evening with friends. When she finally returned home, she noted that the circular about Hudson Smith was gone. Since it was nowhere about the rooms, she concluded that it had been thrown out with the trash and so passed the matter by.

FÉLICE BONNARD was inhabiting a none too pleasant chambre

meublée in the Rue Turc. That same evening, she left her room

exactly at eight, and was joined outside by a man who had been

awaiting her. They walked several blocks without speaking, came

at length to the Café de la Terrasse, and took one of the outside

tables beneath the tamarind trees. When the waiter had departed

with their orders, the man, who revealed himself as a well-

dressed person with a rather broad, powerful face crowned by a

thatch of reddish hair and adorned by a sprouting red moustache,

looked at Félice and smiled.

"Well, dear sister? You succeeded?"

"Perfectly," answered Félice coolly. "I am engaged."

The other nodded. "Of course. Who could resist you?"

"You have managed it very well." Félice regarded him with a flash of cold challenge.

"Ah!" said the man blandly. "But I resist all women, my dear sister—"

"Abandon that term!" she exclaimed with a trace of anger. "I am not your sister, Paul! I do not wish you to speak again in that manner!"

The man laughed amusedly. "Very well, my dear Félice. As you wish."

The waiter arrived with their orders, and departed.

"Here is something of interest." Félice took a folded paper from her handbag. "It was lying on the table in the apartment of mademoiselle, so I brought it. The face, you understand, was interesting. Our friend M. Smith seems to be in some demand, and in case you desire to make a thousand dollars at once—"

She concluded with a shrug.

Her companion studied the handbill, then pocketed it.

"I must thank you, Félice, for this thoughtful act. We must leave town immediately."

"Then you do not want to turn him in?"

Lebrun made a gesture of dismissal. "For a thousand? Bah! We are playing for ten thousand, for a hundred thousand! He is a good man; we need him. It does not matter about your mademoiselle. If she saw this picture, she may recognize Smith on the island. But what of that?"

"When are you leaving?" asked Félice.

"Tonight," said M. le Diable, reflectively. "Le Morpion, who is a sailor and who perfectly understands navigation, will remain to bring you and Mademoiselle to the island."

"But she has a man—an old Breton—"

"Oh!" Lebrun laughed softly. "You mean, she had such a one! He was attended to this evening. L'Étiole and Curel tied an anchor to his neck and dropped him over the rail. Trust Le Morpion for the rest, my dear. He is very capable, that one! So is this Curel, also a seaman."

"You intend to work swiftly or slowly, Paul?"

"Slowly, of course. Who knows what may turn up? There on the island we are safe. There is none to interfere. Why not take our time? This is a case where art is worth more than brute force. Listen!"

Enthusiasm kindled in the broad, powerful features. One saw that those features held not so much a lack of refinement, as a loss of pristine refinement; as though some elder fires of evil had burned out much of the inner man, purging him of conscience and all spiritual things.

"My dear Félice, that island was absolutely made for us; the ensemble is perfect—perfect! No communication with anywhere. A fool of a fat man and his silly butterfly of a daughter. A house filled with artistic, fictitious treasures. A cellar filled with real, factitious treasure; liquor, you comprehend—the most absolute treasure in the world of today. Do you realize that America has ceased to ship liquor to us, that lack of space forbids much being sent from England and France? A cellar filled with liquors can be taken to any port on the mainland and sold instantly, where a cellar filled with gold would only excite queries. You see? Besides, there is the place itself—a magnificent health resort for one so lately undermined by hard work on Noumea, not to mention a difficult escape."

FÉLICE regarded him with a slight frown. "You mistake," she said slowly, "when you speak of the girl as a silly butterfly. Here, I grant, she is gay and reckless and merry. But be careful! I think this girl is no fool."

M. le Diable nodded soberly. "I respect your judgment, Félice. I shall not forget it."

"Besides, what do you plan for her?"

A sardonic smile tipped his lips as he regarded her. "Ah, you look upon her with jealous eyes? Nonsense! When have you known me to look upon a woman? Never—unless it were you; and sometimes I think that even here I made a mistake."

She trembled slightly, but her eyes did not waver. "Then, about this girl—"

"Bah! I shall give her as a reward to L'Étiole. Now, by all means neglect no details; remember, I plan to remain on that island for some time. Recuperated, refreshed, enriched, we shall leave there when we wish. Then the world lies before us!"

"Before—who?" asked Félice.

"Before—well, before us two! Is that satisfactory? To your health, Veuve Bonnard! You and I, we shall spend our honeymoon in Japan!"

The woman's eyes flashed with a singular fire—a fire, one would say, of exultation. She seized and lifted her glass.

"Good! It is a promise, Paul?"

"It is a promise," the man nodded. "My promises are never broken."

His glittering black eyes watched her, a terrible gleam in their depths, as she drank; when her gaze returned to him, the gleam was gone.

A man who sat at the adjoining table, and whose eyes had several times fallen upon the face of M. le Diable, rose and departed. He strode along to the Rue Lagrandière, turned down to the middle of the block, and entered the Gendarmerie.

This man came to an office where a light showed, and entered. Inside, he found another man, like himself clad in civilian clothes, who glanced up and nodded from a paper-littered desk.

"Do you remember," said the new arrival abruptly, "a man who was brought to Hanoi from our settlement in Shanghai—a man wanted for a particularly atrocious murder in Hué City?"

"Paul Adran, alias Lebrun, alias Thomson, alias le Diable—alias everything!" said the man at the desk, without hesitation. "Suspected of being an Englishman or American. He was sentenced to Noumea for life; sentence approved by Des Gachons and appeal denied. He was transported. Well?"

"I thought tonight," said the newcomer reflectively, "that I saw him sitting at a table of the Café de la Terrasse. I only saw M. le Diable once, so I am not certain, yet—"

The other smiled. "My dear fellow, absolutely impossible!"

"All the same, let us have the Noumea report that came in two days ago."

Ten minutes later, the man at the desk read aloud a sentence.

"Drowned in attempting escape," he said. "I trust this satisfies you?"

"Evidently." The bearded one sighed. "Evidently! What about this American, this man Smith? The information that he was believed to be here in Saigon—"

"Was correct." The man at the desk glanced up, nodded. "I found this afternoon that he had been here, had been employed as a labourer at the quay."

"Had been?"

"He vanished from sight two days ago."

The newcomer made a gesture of resignation.

"Not just Smith has vanished, then, but a thousand dollars, which is more to the point." He picked up several official cables and telegrams, and began to open them. "Ah!" His voice again drew the eyes of the man at the desk. "Here is word from Hanoi! We must look out for two men, known as L'Étiole and Le Morpion—descriptions given. Also a request from the governor-general himself that we leave nothing undone to locate the man Smith. Devil take it! Who is this American, and what has he done? Why do they send us no details?"

The other man shrugged his shoulders.

"Who knows? But we may find him. Five of our best men are going over the lower end of the city at this hour. What about the two who are wanted?"

"A murder and robbery in Hanoi. See that the bulletins are copied and posted in the hall at once. With luck, we may pick up all three before dawn."

At this precise moment, the men under discussion were engaged in getting supplies aboard a whaleboat which lay at the wharf, not a hundred yards from the Customs house.

LEBRUN had taken in charge the whaleboat, which was moored openly at the Messageries wharf on the river. Presumably, the palm of the quay watchman had been gilded, to prevent interference. Curel and Smith were handing down provisions and boxes, while in the boat L'Étiole and Le Morpion stowed them away. Smith had known M. le Diable twenty-four hours, yet he had not the least idea of where they were going or what they were going to do. If his companions knew, they said nothing to him. Smith had not shared in the removal of Paul, the Breton boatman, but Curel had participated in that murder, with his usual bored air.

Suddenly, an indistinct figure appeared from the shadows of the godowns, darted forward and engaged in a low conversation with Lebrun. The figure darted away and was gone again. Lebrun came to the boat and spoke, addressing the two men below.

"Messieurs! The police are looking for you gentlemen. Le Morpion, you will have to go with us instead of remaining here."

There was a sound of hearty oaths from below. Monsieur the Devil took the arm of Curel and drew him to one side. He spoke in a low tone.

"You told me that you had been in the navy. You can navigate?"

"Perfectly," said Curel. "That is, if I have opium. My pills are gone, and I can find only pipe outfits—"

"I know, I know," said Lebrun impatiently. "You who eat, cannot smoke, eh? Very well; I have a supply of pills ready for you. You must remain and take charge of that Des Gachons boat—apply for the job. Félice will make things easy for you, if you tell a convincing lie. If you cannot do it, then the devil take you! I want no inefficient ones."

"Oh, I'm scoundrel enough for anything," said Curel philosophically.

"You had better be," said Lebrun dryly. "We must get out of here at once. M. Smith! The police are in search of you!"

Smith chuckled as he joined them. "Not for the first time. I like this way of leaving town, too—right under the noses of the customs people, from the biggest wharf in the city!"

"Always audacity," quoted Lebrun, with a soft laugh and a glance at the lights of the nearby Customs house. "Everything is stowed? Very well. We must get down the river and be off Cap St. Jacques before daylight. Curel, can you accomplish your share?"

"If I have the opium."

Lebrun handed him a package. "Then, au revoir, and the devil's luck! Down with you, Smith, we're off this instant!"

SMITH climbed down into the boat; its mast was already

stepped. He joined L'Étiole. Behind them sat Le Morpion. Monsieur

the Devil came down, cast off the lines, and took his position in

the stern at the tiller.

"Up with the sail, once we are in the tide," he ordered softly. "Watch for police boats!"

The craft floated silently out into the current of the river. It merged into the mists that writhed slowly about the surface of the muddy water, and then it was gone into the night, absorbed. Curel gazed after it for a little, then turned and walked away, tearing at the package of opium with fumbling fingers. A queer smile was set upon his dissipated face, the smile of one who sees in prospect some very singular events. The four men in the whaleboat went down the river without hindrance. Lebrun conned the lights and steered their course; once they passed within thirty feet of a gay Fluviales steamer, whose bright lights flooded them with brilliancy. Lebrun waved ironically at those who lined the rail, as the searchlight touched him. It seemed to occur to none of the four that they were doing a remarkable thing in thus setting out to sea in a whaleboat, bound on an errand which could hardly be philanthropic in nature. Perhaps Curel, who so hated facts, regretted that he was not with them in this mad fantasy.

When dawn heaved up out of the ocean, the whaleboat was skimming along beneath a brisk wind. The river and its narrow, widening entrance had fallen behind. To the east was a faint blur upon the horizon—Cap St. Jacques.

Lebrun headed the boat into the south, steering by a compass which lay beside him. This remarkable man was not questioned by his companions as to his navigating ability; one takes for granted that M. le Diable can do anything.

A little afterward, the four breakfasted. Then Lebrun gave over the tiller to Le Morpion, who crouched above it like a bulging-jawed dog, and lay down to sleep upon some canvas. As he stretched out, he glanced at Smith and put one hand into his pocket.

"Here is something that may interest you," he said, and handed Smith the folded paper which he had received from Félice, and which Félice Bonnard had taken from the table in the room of Berangère des Gachons. Then he closed his eyes and slept.

Smith, sitting beside L'Étiole, glanced at the paper and smiled sardonically. He took out his pipe and lighted it. Certainly, he reflected, this picture of J. Hudson Smith, shaven and trimmed and collared, looked very unlike the Smith who he was now—the dirty-jawed ruffian bound for he knew not where!

The paper fell from his hand as he puffed. L'Étiole bent over, caught it as it fluttered. He saw the picture, and his one blazing eye opened wide in astonishment as he read at a glance the heavy lines of type below.

"Name of a dog!" he ejaculated softly, lifting his eye to Smith. "This—why, this ventre-bleu looks like you!"

Smith laughed. "Thank you, my friend. Looks are not deceiving."

L'Étiole started. "You—why, it's not possible! I know who this man Smith is—at least, I heard in Hanoi that he—"

Here, all in an instant, Smith perceived disaster leaping at him. His face hardened.

"You don't know everything!" he said in a low voice. "Be careful!"

L'Étiole was so utterly taken aback by astonishment, that for an instant he could only stare, incredulous.

"But—why, I never connected you with him! This dog of hell is the one who—"

Smith's fingers gripped his arm.

"Be careful!" said Smith quietly. He realized that Le Morpion, who could hear nothing of what they said, was gazing at them curiously. "Be careful, I warn you!"

From L'Étiole broke a sudden bursting snarl of fury.

"You—hell be kind to you!" he gasped. "So this is your game, is it—"

The hand of Smith tightened on his arm. But the other arm moved, flashed, drove in and out like the head of a striking snake. The other hand of Smith was in his jacket pocket. That pocket vomited a splash of red flame, gave vent to a single smashing report. From Le Morpion came a hoarse, inarticulate bellow. The figure of Lebrun leaped straight upright, pistol in hand. But there was no need. L'Étiole had fallen back against the corner of thwart and gunnel. His two hands were clasped about his throat, and through the fingers seeped a dreadful tide of bubbling crimson. A knife had fallen from his fingers into his lap. His one blazing eye stared for a moment at Lebrun, his lips were open and vainly trying to utter a word. Then his lips closed, his one eye fluttered shut, and he fell back in limp death.

Smith sat motionless, his left hand bringing a pistol into sight. Over his face was creeping a deathly pallor. His eyes went to Lebrun.

"What's this?" crackled the latter's voice.

"We disagreed," said Smith. "You've lost L'Étiole. Don't ask questions, you fool! You'll lose me if you don't give me—a hand—quick!"

His right hand, pressed against his side, came away red. L'Etoile's knife had bitten him. Then, quietly, he laid down the pistol and doubled forward, unconscious.

"He shot L'Étiole!" cried out Le Morpion, his voice terrible. One would have said that this scoundrel, this unspeakable ruffian, was pierced by grief for his dead comrade in sin. "He shot L'Étiole—"

Lebrun gestured for silence.

"Don't be a fool, you! What caused the quarrel?"

"I couldn't hear. They were talking. L'Étiole snapped with his knife—"

"And paid for it," said Lebrun. "I am sorry. But this fellow Smith—did you note how he used his brains? Said I'd lose him if I didn't act! Clever, I call it. He knew that I couldn't afford to lose two at once. Keep your hands off him, understand? This man is worth a hundred. He has more brains than L'Étiole."

"How about me?" grunted Le Morpion.

"You're a friend. He's a mercenary. Besides, he is to be blamed for our future sins."

Le Morpion saw sense in this, and said no more, although his eyes were very dark and evil.

MEANTIME, Lebrun was bending over the figure of Smith.

Removing jacket and shirt, he laid bare the side—white,

firm skin marred by an ugly gash that welled slow blood. Then,

and coolly enough, Lebrun searched the unconscious man from hair

to socks; searched him thoroughly, carefully, unhurriedly.

Whatever the object of his search, it was unattained. He replaced

everything.

After this, he gave his attention to the wound, which was not serious. He bound it very deftly, replaced shirt and jacket, and left Smith to recover of his own volition. He picked up the body of L'Étiole, poised it a moment at the boat's edge, and sent it overboard.

"A good friend, a faithful friend, an honest friend!" he said, gazing out after the bobbing speck. Yet, perhaps, the words were sardonic; there was a queer gleam in his black eyes as he gazed.

"What brought it on?" demanded Le Morpion sulkily. "What caused it?"

Monsieur the Devil shook his head. "Who knows? Waken me when this man opens his eyes. Touch him not. Speak not. Only—waken me."

With this, he took his former place on the canvas, and appeared to fall asleep at once.

The morning wore past in magnificence of solitude, the sun blazing in the sky, the ocean all blue-green and desolate, empty of ships. The whaleboat skimmed on and on, pushed steadily by the crisp breeze, Le Morpion steering her skilfully and cunningly. Once or twice, when his eyes wandered to the inert figure of Smith, the sail wavered, for he was steering by the wind rather than by compass. The seas swung past endlessly, the foam hissing and swirling under the lee rail to bubble out behind in a thin wake. On the canvas, Lebrun slept, an arm over his face; above the tiller crouched Le Morpion, watching, always watching.

Then, suddenly, the eyes of Smith opened. Le Morpion was gazing upward at the moment. Like the Indian who does not see the waving grass yet perceives something amiss with Nature's ordering, this man perceived the movement. An inarticulate word came from his lips. Instantly, Lebrun sat up and gazed at Smith; he was wide awake, speaking, even as he sat up. One would have thought that he had slept with the words breaking on his lips, so swiftly did he speak.

"Ah! Smith, what did you and L'Étiole quarrel over?"

Smith, equally alert, was conscious that much time had passed since the affray. He saw danger in the question. He read danger in the intent gaze which Le Morpion bent upon him.

"Quarrel?" he responded. "I remember now—why, there was no quarrel! He drew a knife and struck; I shot him."

"Ah!" said Lebrun calmly, regarding him. "Well, let it pass. You are thirsty? There is water beside you."

NO more was said. None the less, Smith was subtly aware that

he had not given the right answer. He felt intuitively that he

had bungled somehow; yet he was too thirsty to care. He got the

water and drank. Lebrun went to sleep again.

After some time, Lebrun awakened and took the tiller while Le Morpion crawled up forward, munched some biscuit and curled up in slumber. Smith stared up at the calm gaze of Monsieur the Devil, and voiced the question that was bothering him.

"Where are we going?"

Lebrun's black eyes glittered on him reflectively. "To an island. To a place of vengeance. There is a man whom I hate, whom I shall kill; then we take his possessions. His name, Des Gachons."

The eyes of Smith widened a trifle.

"Des Gachons!" he repeated in a low voice. Lebrun regarded him attentively. "What? You know him?"

Smith feebly shook his head. "No. But he may know me."

"No. He has been out of official affairs for quite a long time. He will not know that you are wanted, that there is any reward for you. Nor will he know me, since he never saw me; although he might have seen my picture. We must chance that."

"I'm not worried about you," said Smith. "But when he knew me, I was employed by the government."

"Ah!" said Monsieur the Devil calmly. "This is news. In what capacity?"

Smith allowed his head to droop for an instant. He was lying now, and lying artistically; he was not so weak as he seemed. Still, there was not great strength left in him.

"If I told you, then you would consider it a lie."

"None the less," said Lebrun, regarding him, "I would advise you to tell me."

There was something deadly in these words.

"I was an engineer—of construction. With the new railroad. Not long ago, I needed money—I made a mess of things, but got away."

Lebrun nodded. "Then you got the money?"

"I have five thousand dollars in my belt."

Lebrun had discovered this money in his search. He nodded his head.

"Very well. Now go to sleep—there will be no difficulty about Des Gachons."

The matter was closed. None the less, Smith retained an uncomfortable conviction that he had somehow bungled. Not in words, perhaps, but in some detail—a glance, a gesture!

However, there was nothing to be done about it now, and he dropped off to sleep.

J. HUDSON SMITH, lying in the boat or sitting propped against his rolled jacket, spent several uncomfortable, painful and reflective days. His wound was developing badly; had taken on a touch of fever which made Lebrun frown over the dressings. Lebrun was a good surgeon, deft and cunning in the fingers. This man seemed a good everything. A good navigator, certainly. He guided the whaleboat over the waste of waters without help from Le Morpion, and with unerring certitude. There were charts and instruments in the boat. During these days, Smith learned for the first time, from conversation and scattered hints, how Lebrun had come to find the island owned by Des Gachons.

The American could guess at much of the story which remained untold—much at which even M. le Diable himself seemed now to reluct in thought and word. It was an odyssey fit for the devil himself! Bad enough was the escape from that infernal paradise, Noumea; the escape, tinctured with blood and desperation, imbued with images of savage, naked brown men, of weary-eyed guards, of the night swim past the ships and that little island which sits in the jaws of the harbor and vomits the shrieks of tortured humanity. Worse yet was the sequel, the tossing for days and nights upon a crazy raft of brush, the finding of a life-buoy lost from some ship or some corpse, the savage persistency of spirit which held the failing body ever to its work. After this, the island; the last flickering effort of the iron will, and safety. Following upon these things, the flame of vengeance toward the man who had finally succeeded in sending him to the penal colony.

Smith realized that he was going to be in a bad way unless his wound quickly received antiseptic treatment; but he fought down the fever and held his peace. He had little to do but study his companions. Le Morpion possessed a good deal at bottom; a sullen brute, yet capable withal, and extremely cunning. But the other, this Monsieur the Devil—here was a man not to be fathomed or understood! Mentally abnormal beyond doubt. Somehow warped into a career of undiluted deviltry. In brief, an enemy of society.

Then, at last, the unceasing monotony of sky and sea was broken; in that long sword-like line of the horizon appeared a slight nick. This came at sunset. With dawn, the nick had grown into a green smudge, and by noon the whaleboat was off the entrance to the island harbor.

Here Lebrun delayed purposely. There was evident commotion ashore; the small cruiser taken to Saigon by Berangère had not yet returned. The whale-boat came slowly in toward the curving crescent of beach, where, in obvious agitation, Jean Marie Auguste des Gachons was marshalling his forces to receive the unexpected visitors.

The escalier was working fast; the two secretaries, the gardener, the chef, and several native servants appeared on the beach, and Des Gachons stood at their head. Lebrun, smiling thinly, directed the boat to the sand at his very feet.

SMITH watched and listened sardonically. Was it possible that

the judge would not recognize the criminal? True, Lebrun was

changed now; the reddish moustache altered his entire appearance,

nor was there anything of the criminal in his bearing. Quite the

contrary.

"Who are you?" boomed out Des Gachons, theatrically. His pose was majestic.

Lebrun leaped out to the sand, drew in the prow of the boat, turned, and rendered an elaborate bow. "Monsieur," he said gravely, "you see before you three shipwrecked unfortunates. I am a humble devotee of ethnology, mineralogy, and the scientific arts; Paul Lebrun by name, an unsuccessful aspirant for the Prix Goncourt in times past, and for some years a student of the sciences of China."

Before he could proceed further, Des Gachons advanced with open arms and tendered him a warm Gallic embrace. "Colleague, I welcome you!" he exclaimed sonorously. "You have come to a good house of hospitality. I, too, am something of a savant in my unworthy way; Des Gachons by name—"

"What!" exclaimed Lebrun, drawing back in astonishment. "Not the author of that admirable and learned treatise upon the ethnologic significance of the lamaic rosaries?"

"The same," admitted Des Gachons modestly.

"Then it is a kindly fate which has drawn us to your shore!" cried Lebrun. "To think that I have touched the hand of this master! I am overcome! But I forget our friends. Allow me to present to you an American gentleman, a fellow passenger on our hapless coasting steamer—Monsieur Smith. He was hurt during a wild scramble for the boats, you comprehend. And this is one called Le Morpion, an excellent seaman, to whose care and skill we all owe our lives."

"Ah!" said Des Gachons briskly. "A wounded man? Monsieur, have no fear! We shall care for you excellently! We have guests; that is admirable! I welcome you!"

It was at this point that Smith gave way suddenly; the over- tensed nerves, the overstrained muscles, collapsed. He realized that he was burning with fever, and fell asleep. The words that had formed upon his lips remained unuttered....

When he wakened, it was to find himself lying in a bed. The room about him was, to his disordered senses, a room of some eastern palace. Real furniture, real paintings on the walls, real flowers at the window! He was in a guest room, of course. What made it more terribly real, was Le Morpion sitting beside him, watching.

And Le Morpion stayed there, as though he had orders to this effect.

A day had passed, thought Smith; it was another morning, and the fever was gone out of him. He did not try to speak. He lay silent and unmoving; as he lay, there came voices from outside the open window, which in fact overlooked the sunken garden. They were the voices of Des Gachons and Lebrun. Their host, gathered the American, was about to show Lebrun over his island estate. To this M. de Diable objected for a moment.

"One thing, dear colleague!" he protested. "I wish your opinion upon a vexed point. For some time I have been studying the question of turquoise in China—a most interesting problem!"

"Most interesting, indeed," agreed the voice of Des Gachons. "Well?"

"You are aware that the stone is unknown in many provinces of China," pursued Lebrun, proving himself master of some astonishing knowledge. "Indeed, it is regarded as pertaining to barbarians; it did not enter imperial circles until the K'ien- lung period of the Chings. It was regarded as a form of petrified or transformed fir, as is indicated by its present name of lu sung shi or 'green fir-tree stone.' Yet we know that Marco Polo—"

"Exactly!" exclaimed Des Gachons eagerly. "He spoke of the monopoly—"

"I am coming to that. My theory is that the stone was introduced under the Mongol emperors, and that its mining and use was broken up during Ming times, not to be revived until the recent K'ien-lung period. I base this theory on the fact that the earliest word for the stone is tien-tse, occurring in the Cho-keng-lu, published in 1366. Therefore—"

The voices drifted off and became indistinct.

Smith saw Le Morpion glance at the window, a dark smile hovering about his ugly lips.

Smith saw nothing of his host. As the hours passed, native servants appeared, but Le Morpion never left the room. One would have fancied this man utterly devoted to the wounded American; but in this devotion, Smith read a sinister significance. Very possibly Le Morpion was here to guard against any delirious babbling.

The native servants of the establishment numbered three. They were a man and two women, brown creatures who spoke French after a fashion, and who had been fetched from the mainland. They were ignorant and timorous creatures, quite devoid of any graces or civilized culture; the man and his two wives had been brought here to serve, and they served—that was all. As for the polygamous aspect of the case, in these days when one can get servants at all, one does not inquire too closely into their private lives, n'est ce pas?

LEBRUN, on this fine morning, had terminated his argument

anent turquoise, and was accompanying his host upon a walk about

the place—a walk which was destined to terminate very

unhappily for Jean Marie Auguste des Gachons.

This simple and honest-hearted fat man was supremely happy. To have his little paradise invaded by three unfortunates to whom he could give shelter and aid, was a pleasure. To find that one of these men was a fellow savant, a person of discernment and much ethnologic lore, was a delight. To find himself recognized as a master, deferred to, regarded with awe and honour, was a supreme happiness.

So Des Gachons accounted himself fortunate, and devoted his energies to showing Lebrun about the place. First came the house itself; a house built not for show, but for living in. The cellars were exhibited with some complacency—indeed, there was a stock of liquors in them which was now worth a small fortune alone! The kitchen, under its French chef, an excellent man with a brain like that of an ox in all things save food. The collections in their cases—jewels and rare works of art from all the eastern coasts; an excellent array of gilded bronzes, champlevé and cloisonné from China, and some magnificent porcelains. If Des Gachons made his money in princely fashion, he had also spent it in the same way.

After the house, the exterior, with the old gardener proud of his work; the establishment was on display, and all recognized it. And at last, ignorant that his visitor knew the way no less than he, Des Gachons took Lebrun down the avenue of palms to the swimming pool.

This was now the same as when he had first looked upon it, except that there was no golden figure aflame in the sunlight. The two men circled that pool of cerulean blue, Des Gachons opened the gate in the wall, and they passed to the fantastic little orchard, with the cliff and the sea beyond.

Here Des Gachons paused, and sighed as he surveyed the place.

"This was planned for the hot days, my friend," he said, waving his hand about the orchard. "You comprehend, one visits the pool, which is fed by springs; then one comes out here beneath the trees with a book, perhaps, and sits on the cliff and watches the sea. I must set about building the little summer- house which I have planned, to perch just here on the edge of the cliff."

He indicated the spot. The two men stood there at the verge, and gazed on the sparkling waters beneath. Perhaps Lebrun was thinking of how he had come here first, naked and perishing; how he had struggled up this cliff to the place where they now stood. His eyes were sombre as he regarded that cliff.

"One does not miss the city here," said Des Gachons, pulling at his pronged beard and looking vastly complacent. "It was work, of course, building all this; vessels and labourers and architects, you understand. But now—it is a paradise!"

"It is indeed," said Lebrun in a low voice. "But do not forget, my friend, that into the earthly Paradise came Satan!"

Des Gachons regarded him with a smile. "What do you mean, then?"

Lebrun took a cheroot from his pocket and lighted it, leisurely.

"I have some knowledge of which you may be ignorant," he said. "Do you remember having passed upon the sentence of a criminal who was called M. le Diable?"

Des Gachons frowned, considered, and at length uttered an exclamation.

"Ah, yes! Tron de l'air!" Like the immortal Tartarin, this fat man was also of the south. "M. le Diable! Of course; the man was a hardened criminal, a degenerate bit of humanity, who was caught by our people in Shanghai. He had committed atrocious murders in the province. He was said to be at the head of a band of desperate Apaches. I remember very well. It gave me tremendous satisfaction to be rid of such a person—he was sent to Noumea for life. One does not live long in Noumea, you comprehend."

"Exactly," said Lebrun in a dry tone.

"It was most unfortunate," reflected Des Gachons, "that this man alone was taken, and not all the members of his gang. I remember recommending most urgently to my successor that no pains be spared to hunt down and root out every branch of this evil tree! But, my friend, what caused you to bring this criminal to memory?"

"Because," said Lebrun, "I heard recently that he had escaped from Noumea."

Des Gachons started. His ruddy countenance blanched slightly.

"Impossible! No man can escape from Noumea; one dies there, but escapes—never!"

"No man, perhaps," said Lebrun calmly. "But Monsieur the Devil—that is another matter entirely! However, there are two versions of the story. One that he escaped; another, that he died in Noumea and came to life elsewhere. Are you interested in hearing them?"

Des Gachons stared at him. "But—but—you are saying incredible things!"

"Incredible? Nothing is incredible, when one believes in a personal devil!" returned Lebrun. His smile was, as the French say, "sourd"—a coldly disdainful, inexpressible smile. "One story goes that he escaped by sea, and that the sea brought him to this island."

Des Gachons started again, this time more violently. From his pallid lips was wrung a low cry.

"This—this is some jest, monsieur?"

"On the contrary, unfortunately," said Lebrun.

"The story says this criminal came here, stole one of your boats, and departed."

"The whaleboat!" cried Des Gachons. "The whaleboat that was missing!"

"Exactly. This M. le Diable took your boat and departed. He went to the mainland, found the remnants of his old gang, and planned a razzia upon your island. Probably he did not regard you with any feeling of gratitude—"

Des Gachons staggered, his face pale as the dead.

"Incredible! This—this is some frightful lie—"

"Possibly." Lebrun made a calm gesture of assent. "The other story runs that he died in Noumea. Well, he died—and he came to life again later. You understand? The devil could hardly die, my dear monsieur; at least, the life after death of M. le Diable would be most fascinating to contemplate, from the stand- point of science, is it not? Still, in either case we arrive at the same conclusions; namely, that he would come to interview you—"

"Devil fly away with me!" ejaculated the other, thickly.

"Precisely." Lebrun bowed. "I am M. le Diable, at your service. Let us fly, by all means!"

He threw away his cheroot and approached Des Gachons, upon his lips a terrible smile.

SMITH and Le Morpion were alone in the room, shortly after noon, when Lebrun joined them. M. le Diable took a chair beside the bed and inquired with solicitude after the patient.

"I'm all right," said Smith. "A bit weak, naturally."

Lebrun nodded. "Very good! You are hungry?"

"Somewhat. What's the matter with luncheon?"

"Nothing; I have just come from the kitchen, and I assure you that an excellent meal is waiting. A very excellent meal, in fact!"

The trifling detail that Lebrun had just come from the kitchen, quite escaped the attention of J. Hudson Smith at the instant. Before he could respond, the figure of one of the secretaries appeared in the doorway.

"Ah, M. Lebrun! Your pardon—the chef told me that you had returned—luncheon is served, monsieur! Can you inform us where M. des Gachons has vanished to?"

Lebrun smiled. "I can, monsieur. He is at this moment located near the cliff beyond the swimming pool, and is contemplating a serious poem upon immortality, after the manner of M. Ronsard. He requests that luncheon go forward without awaiting his coming; as for myself, I shall remain here to watch the condition of my patient, if you will be good enough to send me something on a tray. Le Morpion, do you wish to be relieved?"