RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

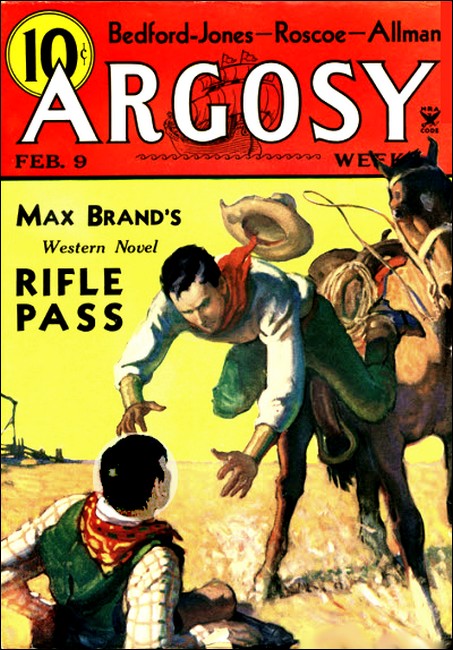

The Argosy, 9 February 1935, with "The Case of the Deathly Barque"

Sir Ronald has evidently been dead only a few minutes.

"Matilda Briggs was not the name of a young woman, Watson," said Holmes in a reminiscent voice. "It was a ship which is associated with the giant rat of Sumatra, a story for which the world is not yet prepared." —"Adventure of the Sussex Vampire"

DURING The period of his retirement at Limehouse, John Solomon was approached by all manner of people and I acted as his buffer, his contact man. Many of the affairs in which we were engaged together, such as the one herein described, were referred to Solomon by Scotland Yard, and I suppose might be termed detective work.

In certain incidents, notably the horrible episode of the Atkinson brothers, real crimes were involved; or, as in the frightful matter of the Sleeper, crimes beyond the realm of criminology. John Solomon was no student of crime; he detested it. His remarkable fund of specialised knowledge, his singular mental processes, his uncanny way of grasping at the essential heart of a mystery, form the most interesting part of all these cases. In the present instance, for example, despite repeated murders, there was no crime involved—as I think he, and he alone, sensed almost from the start.

IT was, I remember, a drizzling, blustery afternoon in March,

and I was busily dictating letters in Solomon's private office,

when the telephone rang. I responded.

"Hello, Mr. Carson? Inspector David speaking. I'm on a job that might interest Mr. Solomon—the investigation of the barque Matilda Briggs, due at Greenhithe tomorrow from Brest. Do you suppose I might step around and see him?"

I did not hesitate, for David was one of the Yard's best men and on more than one occasion had worked intimately with Solomon.

"By all means," I replied. "He's been feeling a bit down in the mouth today and talks of going back to Egypt and Port Said. A sure sign his liver's out of whack. Drop in and haul him out of the depression, if you can."

"In half an hour," said David, and rang off.

I passed on through the blind office into the shop, to apprise Solomon. To my disgust he gave me one blank look and then ignored me utterly. He was selling an old ship's lantern to a tourist lady from Ohio, and was absorbed in the deal.

Solomon took this ship chandlery business seriously, oddly enough. He had made his start as a ship's chandler in Port Said, and now, despite his unlimited resources, he had settled in Limehouse in the same line. This shop, with its heaped-up mixture of rope, canvas, ship's stores, chronometers and heaven only knows what else, was the dingiest place in the dingiest section of London.

Yet Solomon's keenest pleasure lay in tending shop. I watched him as he argued and chaffered with the lady from Ohio, who doubtless took him to be a regular Limehouse character, and wondered at the man. He wore baggy, slipshod old garments and carpet slippers that were out at the toes. His gray hair stuck out at odd angles. His pudgy but perfectly expressionless features, his mild blue eyes, the old clay pipe in his mouth, gave not the slightest hint of his actual abilities. He was absorbed in selling that ship's lantern.

And finally he sold it. Half a crown, I think, was the price. He wrapped it up and the lady, giving me an uneasy glance, departed. She was probably shaking in her boots all the time, having heard no end of stories about the desperate characters and dangerous dives of Limehouse. Then Solomon turned to me, with a twinkle in his eye.

"Well, Mr. Carson? Werry sorry I am to keep you waiting."

"David just called," I said, and told him of the message. He nodded placidly, but his eye lit up all the same.

"Werry good, sir. I'll just call Mahmud to mind the shop."

The shop safely in the hands of the intelligent young Arab who usually served there, we repaired to the private office, and in due time Inspector David arrived. He was a brisk, capable man who was surprised at nothing Solomon did or said, as a rule. This time, however, was an exception.

"Make yourself at 'ome, Inspector," Solomon said cheerfully. "Since the murderer must be aboard that 'ere ship, it beats me why you'd want 'elp, but werry glad I am to see you."

"What?" exclaimed David, staring. "Then you know all about it?"

"No, sir," and Solomon chuckled, as he whittled black tobacco from his plug into his palm. "You said as 'ow the ship was a- coming from Brest, and you're inwestigating. That means the French police 'as called in Scotland Yard. Why? Nothing less'n murder, I says. It's all werry simple, sir."

Inspector David relaxed, laughing, and swept a glance about the room. Anyone just in out of the blustery rain must have found this office remarkably comfortable, with its cosy fire and air of luxury. David was not astonished by the wonderful old Ispahan rug on the floor, the amazing collection of tapestries and arms and bric-à-brac around the walls—he had seen it often enough. But he nodded gratefully at the drink I mixed and set before him.

"Simple enough, yes," he observed. "At the same time, Mr. Solomon, the affair of this sailing vessel is just a trifle too obvious; it's a nasty piece of work, and has me worried. It's clearly a question of a homicidal maniac, always an unpleasant business. The barque will arrive tomorrow afternoon at the Greenhithe docks of the owners."

"I thought sailing vessels were rare these days?" I put in. Inspector David assented.

"They are. The Matilda Briggs, Mr. Carson, is an old keel owned by the firm these forty years and kept going largely from sentiment, since she barely pays her costs. She is returning from a run to Mediterranean ports with mixed cargo. Her master, Captain Fleming, is by all accounts a most reliable man. She left Greenhithe early in December last and went direct to Malta, where we first heard of anything amiss. To be exact," and David consulted his notebook, "it was on December 30th, the day she left Malta for Marseilles."

John Solomon carefully stuffed his old clay pipe, which smelt most vilely. His placid blue eyes surveyed the inspector for a moment.

"And was it murder, sir?" he asked, with a wheezy sigh.

"It was. A native boatman was found dead close to the ship. No details have been ascertained, except that the nature of his death paralleled that of the other victims. The barque loaded cargo at Marseilles, taking on a consignment for Barcelona. She cleared on January 19th and sailed with the tide early next morning. After her departure, a woman of the port was found dead on the wharf to which the vessel had made fast. The woman had been murdered during the night. Her throat was horribly mangled."

"You mean as 'ow it was cut," interjected Solomon, scratching a match.

"Not at all; that's the frightful part of it. Not cut but torn, mangled, the flesh ripped away and even missing entirely!"

Solomon, holding the match to his pipe, lifted slightly startled eyes.

"Dang it," he ejaculated mildly, "was there animals aboard the barque, then?"

"No animals of any kind," Inspector David returned. "Not even a cat. The Marseilles police did not connect this murder with the ship. At Barcelona, nothing happened. A shipment for Brest was taken aboard. After passing the Straits, the barque ran into nasty weather. She was badly knocked about and made a very slow passage. In the course of this run, the junior mate, a Mr. Haskins, was one morning found dead in his bed."

David paused, nodded at a sharply inquiring glance from Solomon.

"The same way, sir. His throat mangled, and not a thing to show who had done it. This, you must understand, was the first known of the murders to those aboard. Three days later one of the apprentices, a lad named Sotherby, was killed in the same ghastly fashion. He had entered the after hold with a lantern, to inspect certain repairs below decks. When he did not return, they searched and found him dead. These two murders were reported upon reaching Brest, but I know no details.

"On the very night the ship left Brest, the night watchman was found on the wharf there and the French police got in touch with us. Apparently the case is simple, despite its horrible phase."

"Too simple," Solomon said gloomily, puffing at his pipe. "The simplest things is the 'ardest to come at, as the old gent said when 'e kissed the 'ousekeeper."

THE inspector shrugged. "The facts are patent. The murders

were identical. In each case the throat was badly mangled, but no

other injury seems to have been inflicted. Plainly, one of the

barque's crew is possessed by a maniacal frenzy. Granting the

French police average intelligence, it seems certain that the

murderer is at this moment aboard the ship; they would know if

anyone had gone ashore at Brest and remained."

"No, sir," said Solomon positively.

He swung his desk chair a trifle, cocked his feet up on another chair, and his mild blue eyes rested steadily on the police officer. "It wasn't no maniac. It was a stowaway, I says. Just like that."

David shook his head. "A stowaway could not live for months aboard a sailing vessel, unseen and unsuspected."

"Maybe. But It all depends on them 'ere two murders aboard ship," said Solomon. "Then we'll know for sure, when we 'ave the details. It's a stowaway. There ain't no other way out of it."

"If you mean that for a pun," I said, "it's a poor one. So is your theory, John. The inspector is dead right. A stowaway might exist unfound for a week or so, no more. Such a notion isn't logical."

David, I could see, was astonished and irritated by the positive statements of Solomon. So was I. His position was absurd.

"We'll see about that tomorrow," he said, with a wheezy chuckle.

"Then you'll run down to Greenhithe, sir?" asked the inspector. "Excellent! We might make the trip in a police launch, if you like."

Solomon nodded. "I 'ave an old friend as lives in Greenhithe," he observed. "Might be as 'ow you've 'eard of him, though I ain't seen 'im for a matter o' five years. Colport, the name is. Sir Ronald Colport."

"Oh, of course!" exclaimed the inspector quickly. "The great brain specialist, eh? I believe he's been retired for a number of years. The greatest brain man in Europe, they used to call him. Wasn't there some talk about his being inclined to radical ideas and rather singular experiments?"

Solomon sucked at his pipe.

"A great man can afford to be talked about, I says. You might 'ave 'im in if so be as you find there 'ere maniac you talk about, Inspector. Let Colport examine 'im. It's a 'ard job to tell when anyone's crazy, as the old gent said when 'e took 'is third."

"Not a half bad idea, sir," assented Inspector David, and after arranging about meeting us on the morrow, took his leave.

In no uncertain terms, I took Solomon to task for his nonsensical insistence that a stowaway was responsible for the murders. Although he heard me out with a twinkle in his blue eyes, I could see that my words put him in a stubborn humor. Presently he laid aside his pipe and shook his head.

"Just the same, Mr. Carson, you slip a pistol in your pocket tomorrow afore we start. Mind that!"

ON the following afternoon we met Inspector David and with him

went aboard a fast police launch. It was still drizzling, but

with a promise of letting up.

The Matilda Briggs, we learned, would be at her owners' wharf under heavy police guard by the time we reached Greenhithe. I was not looking forward to the trip with any keen delight. Being an American and blind to what the English call the beauties of their beloved river, the Thames on a rainy day made no appeal to me. None the less, the mystery of it exerted a certain fascination.

"Mr. Solomon," said the Inspector, who treated John with a great deal of respect, "I've been thinking over your stowaway idea. A dozen men are awaiting us on board, and I'd like to send the entire crew below and make a thorough search of the vessel, first thing. Then, later, we may interview the crew. Needless to say, no one goes ashore before we arrive."

"We shall 'ave to 'ave lights," said Solomon.

"All prepared," the inspector said cheerfully. "I've neglected nothing."

Darkness was indeed closing down when we passed the training ships and drew in upon Greenhithe. David pointed out the barque to us; she was just being made fast at her owners' docks, at the far end of the town. Close to them, reaching up the hillside and along the water, were villas and a number of rather pretentious residences.

"I see that my men are ready," the inspector said. "Any suggestions, Mr. Solomon?"

"No, sir. Only," Solomon added apologetically, "I'd like to be askin' of the master one or two questions. It don't never 'urt to ask the question, as the old gent said when 'e kissed the 'ousemaid."

We landed. As I was afterward to recall, the barque lay a few feet from the edge of the wharf, held off by buffers and made fast by heavy lines. A gangway had been run across to her deck. The crew, after knocking the battens from the hatches and removing the tarpaulin coverings, made no protest upon being sent below to their quarters. The inspector posted his men, and Captain Fleming was introduced. He was a bluff, hearty man of fifty.

He joined Inspector David and the police about the forward hatch. Two police remained on the wharf to guard the gangway, and the search was got under way. Solomon, who seemed to take no interest in it, moved along the deck with me into the lee of the deck house, well aft, for shelter from the drizzle.

"That's 'is 'ouse," and Solomon pointed with his pipe to a large villa surrounded by a wall.

"Whose house?" I demanded.

"Sir Ronald Colport's, o' course," said Solomon.

"A warm fire and a drink wouldn't be a bad notion," I commented. "We'll wait to see if your stowaway turns up, of course. If not—"

Solomon nodded assent. Presently he moved off to talk with the two constables on the wharf, and I lost track of him.

After a bit, Inspector David and his forces moved aft, having found absolutely no one hidden below. There was a bit of joking among the men, a couple of whom had been whitened from head to foot by a burst flour-cask while moving the upper tier of cargo.

I heard Solomon's voice calling me, from somewhere forward, and following it I found him just emerging from the forward hatchway, which was still open. He had flour about his boots, and in his hand the headboard of a cask. He was looking intently at the deck.

"Look at 'em!" he exclaimed.

"Quick, Mr. Carson, afore the rain washes 'em off!"

The note of excitement in his voice impelled me. I saw a number of white flour-patches on the deck, rapidly vanishing under the fine drizzle. Solomon had brought a flash light and threw it on them.

"The men's boots left 'em," I said. He shook his head.

"Not much. They ain't packed down 'ard, sir. And if I ain't mistook, whoever made 'em 'eaded for the rail. Quick! Ask them constables on the dock—"

I got his idea, and going to the rail, called to the two men there. No one had left the ship anywhere along the rail, they assured me. Their flare covered the whole length of the wharf- side.

"No luck," I said, rejoining Solomon. "You thought your stowaway might have left those patches, eh? Well, he didn't, unless he slipped into the water—and he'd have to jump, not slip. He'd have been seen."

"Dang it!" said Solomon, and examined the headboard of the cask in his hand. Upon it I saw numerous heavy gashes, as though made with an adze. Then, hearing Inspector David call us from the after deck, Solomon went to the rail and gave the circular board to one of the police on the wharf, telling him to take good care of it.

We found that the police search had drawn a blank. There was no stowaway aboard; there were no signs or indication of any stowaway. Captain Fleming placed himself entirely at our command, and led us down to one of the after cabins. Here Inspector David questioned him briefly in regard to the two men who had been murdered aboard ship.

"The murdered mate, I believe, slept aft."

"In the next cabin," rejoined the old captain. "That's where he was killed."

"And the apprentice? He was killed in the after hold?"

"No, sir. The lad had gone down for'ard. We had sprung a bad leak under the bow and he went down to see if the repairs were holding."

"Then the for'ard 'atch was off," said Solomon, sucking at his empty clay pipe. "And when the mate was killed, was the 'atches off likewise?"

"The for'ard hatch, yes. That was when we were making the repairs I just mentioned."

"And at Marseilles?" went on Solomon. "And at Brest? Was the 'atches off then?"

"Yes indeed," said Captain Fleming. "They are battened down the very last thing. When you come to interview the men—"

"We ain't a-going to," Solomon observed placidly. "It ain't no manner of use. Cause why, there ain't no murderer aboard this 'ere ship."

At this flat statement, Inspector David swallowed hard and regarded Solomon with an air of stupefaction.

Before he could speak, however, one of his constables knocked and entered, beckoning him aside. The inspector joined him at the door, listened to what he said, then turned to us with a startled word.

"Good heavens! Mr. Solomon, I've just been sent for. Will you come with me, please? What you just said was correct, remarkable as it seems. Sir Ronald Colport has just been found in his own garden, yonder. Murdered, sir! Murdered in the same terrible fashion!"

WITHIN a few moments we had reached the scene, to admire the

precision with which the police had already worked. A terrified

servant, aware of the police at the wharf close by, had summoned

them. The inspector's men had roped off the body and were

searching the grounds.

Sir Ronald, an elderly but by no means enfeebled man, had apparently been dead only a few moments. His body lay face down near the side entrance of the house. He must have died instantly, for his throat had been torn out in a very horrible fashion. The rain had quite ceased by this time, and after one look at the scene, I was content to join Solomon in the open portico of the house, where the dead man's old butler stood also, gray-faced, horrified.

Presently Inspector David joined us, sent the butler into the house to get us a bite to eat, then spoke softly.

"My, Solomon, this is positively incredible. There's not a mark, not a footprint; and after three days of rain the soil is soft. Sir Ronald had stepped out for a short walk. His own footprints are plain to see. There are no others."

"Ain't 'is shirt wet?" asked Solomon Suddenly. Giving him a startled look, the inspector nodded.

"Yes. I dare say you'd like to think your stowaway swam ashore and grappled with him, and murdered him? Impossible, Mr. Solomon. Not a footprint, I tell you. And what earthly reason would bring even a maniac to such a deed? No, no; there's something mysterious and horrible about this affair, sir."

"There's something werry mysterious and 'orrible about a maniac, too," observed John Solomon. The inspector shook his head.

"Perhaps my men will turn something up. The local police will soon be at work outside. The bushes here in the garden certainly cannot hide a man."

This was obvious. The walled enclosure was of some size, but contained no garage, no other building than the old house itself. This was a large central structure with two wings; one of which held the servants' quarters and kitchen. Except for the cook and gardener. Sir Ronald had lived here alone with his butler, Osgood. Two old men nearly of an age who had been together for many years past.

At Solomon's suggestion, I turned into the house with him, and Osgood conducted us to the library. This butler was gray, with deeply lined, powerful features. Before we had more than glanced around, Inspector David joined us.

The interior of this ancient English mansion conveyed to us all, I think, the same impression of mystery, of tragedy. It was one of those places that seem inhabited, but not lived in. The library, with its solemn racks of books, its severely oak-paneled walls, its insufficient lights, was typical of English discomfort and was extremely depressing.

Osgood could throw absolutely no light upon the murder. He himself occupied a room in the east wing, adjoining that of his master. Sir Ronald depended on him for minor services and desired to have him close at hand.

"There are only the two rooms in the east wing, then?"

"That's all, sir."

"Suppose you give us a look at them. Here, use my flash light."

THERE were only lamps and candles in the house—neither

gas nor electricity. Personally, I have never been able to

understand why so many Englishmen positively shut out the

comforts and benefits of civilization; but then, I am an

American.

Osgood led us to the east wing; except in the central portion the house had no upper floors. The two large bedrooms here had a connecting door. In Sir Ronald's room showed a second and farther door which the inspector tried without avail. He turned to Osgood with a question.

"The door has been closed up, sir," the butler replied. "It formerly opened on the garden, but Sir Ronald disliked an outside door from his bedroom and had it closed."

David nodded. "Well, suppose you lay a fire in the library and see if cook has a snack ready for us. You might serve it in the library, too."

"Very good, sir."

Osgood conducted us back to the library, then disappeared. Solomon went out for a turn in the garden by himself; he was thoughtful and preoccupied. A handsomely bound little volume lay on the table, and I picked it up. It proved to be an address which Sir Ronald Colport had delivered before the Royal Society some years previously, and fell open of itself, as a much-used book will do, at a certain page which bore copious marginal notes in pencil.

A cheerful fire was lighted, a table was brought in, and Osgood laid it. Solomon came back into the room, with word that the men outside were still searching vainly. I showed the book I had found to the others, and the annotated pages.

"Talk about your radical theories," I said. "He was evidently working on this one for a long time. He predicted that wheat and other foods, impregnated and radiated, would prove a tremendous stimulus to the brain, forcing it as one forces plants. A chemical reaction bringing the brain cells to abnormal proportions, combined with certain vitamins—"

"Let's 'ave a look at that 'ere book," exclaimed Solomon, and taking it from me, he pored over it.

When Solomon laid down the little volume, he took out a pencil, jotted down a few notes on the back of an old envelope, and passed the paper to Inspector David. His blue eyes were sparkling—the only sign of emotion in his pudgy, expressionless face. David read the jottings, looked startled, then gave Solomon a long regard, and nodded.

"Right, sir. Osgood!"

"Yes, sir?" The butler paused in his work and looked up.

"Bring in the meal whenever it's ready, and leave it. I want these gentlemen to go across the gardens with me and talk over an idea that's just occurred to me—we'll be back in a few minutes. Don't bother to show us out. Come along, Mr. Carson."

While a bit mystified, I gathered that the Inspector was obeying a suggestion that Solomon had made in his notes, and rose. We all went out of the library and Solomon took my arm. At the house entrance, the inspector turned back. Solomon led me outside and slammed the door heavily.

"Quick, Mr. Carson!" he exclaimed. "This way—"

A moment later we stood at one of the uncurtained windows of the library. Osgood was not in sight. The room was empty.

"What the devil's all this?" I said in a low voice.

"That 'ere east wing, sir, is a good eighteen foot longer'n them two rooms inside," Solomon said. "The door 'e showed us ain't walled up at all. Lied to us, that's what 'e did! Now watch. If I ain't mistook—there 'e comes! And 'e thinks we're out of the way, so to speak. That 'ere book you found, give me the 'ole blessed thing—watch 'im!"

I WAS bewildered. That the staid old butler could be suspected of the murder was arrant nonsense. Before our eyes, he came across the library with a swift stride, glanced around, then stepped to the fireplace. The hand of Solomon tightened on my arm.

Moving rapidly, Osgood pressed a spring that released a panel of the oak wall. Behind it appeared the door of a small safe, which the butler opened. He took out a large sheaf of papers, closed the safe and the panel, and stepped with the papers to the nearby fireplace. He was in the act of throwing them into the fire when Inspector David halted him.

The wretched man shrank back, terror in his features.

"Come on, sir," and Solomon chuckled. "Fell into the trap, 'e did, like a good 'un! Now we're a-getting somewheres."

We returned hastily to the library, where the inspector had placed the sheaf of papers on the table. I glanced at them; they were nothing but notes on experiments, it seemed.

"Well, my man, you have some explaining to do," said the inspector curtly. "You lied to us about that room beyond the two bedrooms. You've attempted to destroy these papers—"

"I had to do it!" cried out the butler frantically. "I promised him I would destroy his notes—I knew everything, I had helped him. God forgive me! If anything happened, he made me promise—"

"Very well," intervened the inspector. "You've kept your promises. Now do your duty, my man. And no lies this time."

The unhappy, deeply agitated butler led us into the hall and then on through the bedrooms—first his own, then that of Sir Ronald. Both Solomon and the inspector held their flash lights, and as we followed the other two, Solomon jogged my arm.

"Best 'ave your pistol ready, sir," he murmured. "I ain't noways sure, but—"

I assented. Osgood came to a halt before the farther door which he had said was closed up. He produced a key, with shaking fingers, then turned imploringly to Inspector David.

"It—it may be dangerous," he said in broken accents. "One of them must have escaped. That is what killed him. I cannot understand it! He put new locks on the cages only last week; he meant to use padlocks in future, but had not obtained them yet. He said they would learn to work the bolts—"

"Open up," intervened the inspector coldly.

I must confess that to me it seemed we were dealing with a madman, for Osgood whimpered and babbled as he undid the top and bottom locks of the door. Then it swung open. The four of us stepped into a large room, and I heard Solomon murmur something about having paced off the length of the wing outside.

A distinct animal odor assailed us. About the walls, in cages ticketed with notes, were rats, mice, guinea-pigs. At the far end of the room were two cages of extraordinary size and strength.

"Animal experiments, eh?" said the Inspector. "Come, come! Nothing illegal about all this—good heavens!"

He had swung his light on the two large cages. "Osgood, what are those creatures?"

"Sumatran rats, sir," the butler replied. "They're the ones—"

WE approached the two cages, and a sort of horrified astonishment fell upon all three of us. One cage held an enormous female rat with a number of young, all of such abnormal size that incredulity gripped me as I regarded them. The mother must have been well over two feet in length, whereas an ordinary rat seldom attains eleven inches. In the other cage, staring at us, was a male rat of even larger size—so large as to be perfectly astounding.

"Dang it!" I heard Solomon murmur. "Look at them 'ere eyes!"

I am not easily disconcerted, but I admit that the eyes of this male rat sent a chill of horror through me. They were filled with a singular expression of hatred; it was an actual intelligence like that in the eyes of a man. I drew back. Those eyes followed me. Then a sudden wild cry burst from Osgood.

"Get away, get away! He was afraid of it—they've learned how to open—"

The sentence remained unfinished. What now took place occupied but the fraction of a moment.

Those cages were fastened by formidable bolts. As we looked, the male rat reached forward. I saw his paw creep between the bars and fasten upon the bolt of the cage door. Even when he moved it, swung it back, I scarcely realized the truth. The female rat, as though at some signal, was performing a like action. In their steadily glaring eyes was a horrible malevolence.

"For God's sake, look out!" cried Inspector David.

All in perhaps ten seconds. The male rat darted out of his cage and leaped. He rose in the air, rose straight at my throat. The shining glitter of those eyes against the light, the bared, hideous teeth, sickened me, even as I fired.

Luckily, I kept my head. The nauseous thing crashed down upon the floor; I fired again and again, in a mad instinct of destruction. Barely in time, too. Inspector David was fighting off the huge female in frantic horror as my bullets took effect.

I scarcely remember how we got out of that horrible place. The inspector hastened outside to reassure his men, who had heard the shots and were shouting at us. By the time we had regained the library, David rejoined us.

His features contorted, his voice broken, Osgood sank into a chair and made a clean breast of everything.

"I knew what he was doing, of course. If—if anything went wrong, I promised to seal up the door and destroy his notes. That would let them all starve to death. But, gentlemen, what did happen to him? They were both in the cages, you saw them! They could not get out or in by the ventilator! If one of them had killed him—no, no! We had stopped up the ventilator, after the first one escaped three months ago—"

"What's that?" broke out Solomon. "One of them 'ere rats escaped?"

"Yes, sir, early last December. It was never found. It was the first one Sir Ronald experimented upon—"

"Good Lord!" I exclaimed. "Then that explains everything, Solomon! The creature went aboard that ship at the docks and was carried away. It remained hidden. It emerged only when the hatches were off—your stowaway, John! You were right after all!"

"Yes, sir," assented Solomon. "And what's more, it come back 'ere wi' the ship, and swam ashore, and them 'ere police never seen it."

"Go to your room, Osgood," said the inspector quietly, touching the broken old man on the shoulder. "No blame attaches to you."

The butler stumbled out of the room. I seized upon the sheaf of papers taken from the wall safe. Inspector David joined me at the table. We began to examine them, and found them to be voluminous notes concerned with Colport's experiments upon the giant rats of Sumatra. As we glanced through the sheets, the frightful truth was brought home to us. At length I shoved away the papers and looked up.

"This is beyond belief, Solomon! The vitamin feeding to increase size, the use of pituitary extracts, the forced growth of the brain cells, the grafting of human brain tissue upon the rat's brain—good heavens! This is not science—it's a menace to civilization!"

"It's 'orrible," said Solomon in a wheezy voice. Inspector David leaned back, wiping his brow. "It's a crime against the 'uman race, that's what I says."

And leaning forward, he caught up the sheaf of papers. The inspector started up.

"Here! What are you doing?"

"Destroying these 'ere notes," said Solomon.

"You can't! I can't allow it—that's evidence, sir—"

"Evidence be damned," and Solomon dropped the papers into the fireplace and swung around, his blue eyes alight and blazing at us. "I ain't a-going to be no party to letting loose that sort o' knowledge on the world! If Scotland Yard don't like it, then let 'em take up the matter wi' me, just like that."

Inspector David subsided, still mopping his brow. A timid knock sounded, and Osgood came into the library. He advanced to the table and took matches from a tray there.

"Excuse me, gentlemen, but I must have matches. My room is dark."

"You'd better close your windows," said Solomon grimly. "That 'ere rat that escaped is the one that killed Sir Ronald. Come back in that 'ere ship, 'e did."

"Thank you, sir." Osgood's shoulders sagged, and a drawn pallor stole into his cheeks. "Please ring if you lack anything, gentlemen. Good night."

He left the room. The inspector swung around on us.

"Mr. Solomon, you must have guessed some of this aboard the barque. Your statement that the murderer was not aboard—"

Solomon, whittling tobacco from his plug, nodded and placidly explained. That trail of flour to the rail, the cask head he had found scored either by an adze or by enormous teeth, had suggested something of the truth to him. Later, the absence of footprints near the body of Sir Ronald confirmed the theory of some animal. The monograph written by Sir Donald, the deliberate lie of Osgood about the existence of another room—all this had formed a chain leading to the discovery of the truth.

"Then," cried out Inspector David, "do you realize what it means? The creature which committed these murders, which killed Sir Ronald—is still at liberty!"

"Yes, sir," assented Solomon calmly. "If I was you, Inspector, I'd 'ave a search made for that 'ere rat, and werry sharp about it too—"

Solomon's voice was checked. I leaped from my chair. Through the whole house rang a most appalling scream, a scream that chilled my blood and made me whip out my reloaded pistol. The inspector dashed for the doorway, his flashlight ready.

"Come along!" he cried, and I ran after him. As the door of the butler's room swung open, his electric beam picked up the body of Osgood on the floor; then it picked up something else. At the closed window of the room beat and fluttered an enormous shape frantically seeking to escape as it must have entered. A thing, now turning its head and its bloody slavering jaws, staring at us with half human eyes—

Once again my pistol spoke, this time deliberately. A moment later, the creature was stretched out dead, beside the body of its final victim.

LATER, John Solomon sat with me before the library fire,

stuffing tobacco into his clay pipe. At one side of the hearth

was a crinkly swirl of gray ash. Solomon leaned forward and

stirred it with the tongs, then picked up a coal for his

pipe.

"There goes the last of them 'ere notes," he said, "and a werry good job, I calls it. It don't never pay to put things down in writing, as the old gent said when 'e took 'is third."

"Has it occurred to you, John," I asked slowly, "that this creature, created by these two men, came back here by a sort of implacable destiny to cause their death? Even your effort to warn Osgood only made his death more certain. If you had not told him to shut his window, if he had not gone directly to do that, ignorant that the rat had already stolen into his room—"

Solomon gave me one look that checked my words. Then he lifted the coal to his pipe, and puffed steadily; but I saw that his fingers were shaking.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.