RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

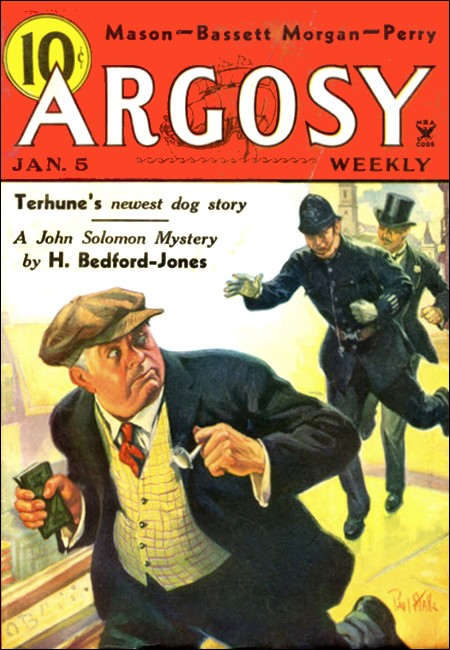

The Argosy, 5 January 1935, with "The Case of the Kidnapped Duchess"

CARSON had just finished dressing, in his room in the Engineers Club. That enormous building in Whitehall Court, housing—a dozen residential clubs, was like a rabbit warren until one got the hang of it.

A knock came at his door.

"Note for you, sir. Thank'ee, sir—"

Carson tore open the envelope. It was addressed to him in the neat, copperplate hand of John Solomon. Inside, also in that unmistakable chirography, was a brief message which required no signature:

Urgent. Meet me precisely nine o'clock outside window of tobacco shop south side of Strand at Temple Bar.

Bewildered, Carson read and reread the note in the keenest perplexity. Then he glanced at his watch. Eight-five. Time to get breakfast and keep that appointment, yes, but—Why, the thing was preposterous, absurd! Even for London, where everything strikes an American as absurd.

Carson descended to the office, went to a telephone, and called Solomon's ship-chandler's shop in Limehouse. No response. Evidently no one there. He hung up and went into the breakfast room, frowning. He even neglected his morning paper, for once.

On the previous evening he had arranged to meet Solomon here at the club at noon. They were catching an afternoon plane together from Croydon for the Continent, on an errand of which Carson knew little. His chill gray eyes speculative, he recalled Solomon's exact words in regard to that errand:

"The worst kind of a job, sir. One that you and me together might swing, and 'elp out the most beautiful woman in Europe, Mr. Carson. But it's a werry dangerous business, sir. That 'ere Duchess o' Furstein is in a werry bad 'ole, and if we give 'er a 'and it means risking our necks—"

That was all Carson knew. Until now, this crazy note, of all things! If Solomon had wanted to appoint another meeting place, why this involved fashion of doing it?

Carson knew, however, that the little old ship-chandler, with his grotesque appearance and Cockney speech, was an extraordinary person; the most extraordinary he had ever met. The Limehouse shop was a mere blind. So, apparently, was the man himself. Behind those pudgy, expressionless features, behind those blank blue eyes, lay a brain of lightning rapidity, a personality of amazing resource and power.

This obscure, humble little man was distinctly not what he seemed. In reality, he moved behind the scenes of political power, in a singular fashion. Carson, who had been on the other side for several years and knew a little of alleged diplomacy himself, had been startled by Solomon's inside knowledge.

"But why the devil didn't he telephone me?" Carson asked himself, as he bolted his breakfast. "He does things in his own way, yes, but this looks asinine. He's got some reason for it, though; that means I'd better keep my brain clear."

In his brief acquaintance with John Solomon, Carson had acquired a vast respect for the pudgy little man's mental workings.

Presently he left the club and strode along the Embankment past the Strand underground station, where he cut up to the Strand by way of Essex Street. This brought him to his destination three minutes before nine. Knowing that when Solomon appointed an hour, he meant that hour to the very second, Carson loitered about.

The tobacco shop in question, a chain store, was the only one in the vicinity; no danger of any mistake. At one minute of nine Carson went in, bought some cigarettes, came out again, and stood in front of the window looking at the display of wares, as he lit a cigarette. Nine o'clock; a minute past; another.

Nothing happened.

Suddenly there was a quick, limping step, a panting breath. At the window, but not too close to him, appeared Solomon. Pudgy figure, shabby garments, wisps of gray hair protruding from the edges of a greasy cap—John Solomon, sure enough. Something fell to the sidewalk; a very small leather wallet, flat. "Dang it!" came Solomon's voice. "Put your foot on it, 'ide it! Move sharp!"

It was not for nothing that this American with the gray eyes, the sharply chiseled features, the alert manner, had been chosen to work with such a man. Carson moved, almost mechanically, covering the little wallet with his foot. At the same moment Solomon turned and hurriedly entered the tobacco shop.

"There he goes! That's the man—in there, officer!"

Two men came dashing into the shop. One a "bobby" in helmet and uniform, the other a tall, distinguished looking man of forty, in silk topper and morning clothes.

Carson let his handkerchief fall. He stooped quickly, retrieved it, and with it the leather wallet. The latter he slid up his cuff.

ALREADY a crowd was collecting. The traffic officer from the

intersection hurried along and held back the curious. Carson

loitered at the window. Inside, he could see John Solomon being

questioned. He went closer to the door, heard the indignant,

whining Cockney voice.

"Wot, me? Why, blime, I don't know nothin' about it—I never seen this 'ere bloody toff before!"

"I could swear this is the man who jostled me!" exclaimed the 'toff.' "And a moment later I missed my wallet, officer. Search him—I demand it!"

"Sorry, sir; you'll have to lay a charge against him," said the officer.

"We can't search him without his consent, you know, unless—"

"Search me, is it?" cried out Solomon loudly. "All right, search me! Nice way to treat an 'onest workin'-man, I calls it; but go on, search me! Out of 'is ruddy 'ead, that's wot 'e is. Search me, officer, and get it over with. I 'ave to meet a pal in no time at the pub in Chancery Lyne—"

Carson took the hint.

He edged his way out of the crowd, walked down Fleet Street, and turned left into Chancery Lane. A pub? Yes, there it was. His step quickened. He entered and after securing a seat at a table, ordered an innocuous drink and lit another cigarette.

"So that was it!" he thought with a certain helpless admiration. "The confounded little miracle had me meet him there on the chance. If he didn't need me, all right. If he did, I was there—and he sure did. What the devil is he picking pockets for, anyhow?"

He had brought along his morning paper, as yet unread. Now, as he waited, he glanced through its pages. Suddenly the pictured face of a woman caught his careless glance; his eyes widened on it. Lovely, lovely! More than mere passing beauty in that face. Something in it struck at him. He looked to see the caption.

S.A. ALIXE, DUCHESS OF FURSTEIN.

Good Lord! Why—He hurriedly folded over the paper, devoured the news story surrounding the picture. In the prosy fashion of English news stories, this related that among the guests arriving aboard the yacht of Sir Basil Lohancs, the famous industrial magnate of Central Europe, was Alixe, Duchess of Furstein. The yacht was touching at London to-day, it appeared, in the course of an extended cruise.

"Our readers will remember," went on the story, "that three years ago the Duchess was forced to abdicate as a result of the social upheaval in Furstein. Then a mere girl, she is now said to be the most beautiful woman in Europe. Unfortunately, she has an aversion for society, being entirely engaged in social welfare work and economic improvements in Palermo, where she inherited the lovely Palazzo di Gonsido. Her Highness is said to have the most remarkable collection of emeralds in existence, which includes those formerly belonging to the Spanish crown."

Carson grimaced at all this. Emeralds, Sicilian palaces—hm! Didn't look as though this dame were in any great need of help. No longer a duchess, either, except to the English press, which for obvious reasons held that once a duchess, always a duchess. But good Lord, what a lovely thing she was!

"Yes, sir, werry pretty indeed, but that 'ere picture don't do 'er justice," said the voice of Solomon. "And she's in a werry bad fix, as the old gent said when 'e buried 'is third."

Carson glanced up at the pudgy little figure which stood beside him, glancing over his shoulder at the newspaper.

"Are you a mind-reader, John?"

"Well, sir, it ain't werry 'ard to read your mind when you look at that 'ere picture," and with a wheezy chuckle John Solomon pulled out a chair and sat down at Carson's elbow. "A pint of 'alf and 'alf, miss," he said to the barmaid, and then got out knife and plug, shredding the black tobacco into his palm.

"You've got it safe, sir?" he asked, low-voiced.

"Yes." Carson regarded him curiously, but made no comment until the drink was brought and they could talk in peace.

"What's back of all this funny business anyhow. I thought we were leaving for Furstein this afternoon."

"I never said so," rejoined Solomon, his placid blue eyes showing nothing except a faint twinkle. "I 'ad a plane chartered to take us to Palermo; but dang it, I was too late. Days too late. I didn't get 'er message in time, that's all. And now they've got 'er."

Carson frowned. "Who's got her? Here's all about her in the morning paper—"

"I seen that 'ours ago, sir," and Solomon sighed. "That's what got me busy, so to speak, and a werry 'ard morning I've 'ad, if I do say it as shouldn't. Dang it! That 'ere Sir Basil almost 'ad me, for a fact. If you 'adn't been there—well, no matter now. A miss is as good as a mile, I says, and werry true it is."

"Sir Basil, eh? Was that the man in the silk hat? Odd!" said Carson. "According to this paper, his yacht doesn't arrive until to-day."

"Correct." Solomon held a match to his old clay pipe and puffed contentedly. "Werry likely 'e ain't aboard 'er, Mr. Carson. That was 'im, all right. One o' me men spotted 'im last night. Come by air, 'e did, to meet the yacht. Now let's 'ave a look at that 'ere wallet, sir. If it's got the telegram in it, we'll 'ave a chance to 'elp 'er after all."

Carson slid the beautiful little wallet from his cuff. Solomon opened it, to disclose a gold monogram inside, and slid from it a folded blue paper and a ten-pound bank note. He opened the paper, then his blue eyes darkened.

"Dang it!"

Carson took the paper, saw that it was a telegram sent from Calais, and was addressed to Sir Basil Lohancs at the Cecil.

The message was a long one and was absolutely incomprehensible.

Solomon puffed at his pipe for a moment.

"Somebody aboard that 'ere yacht sent it from Calais early this morning, before they sailed," he muttered. "Dang it! Now I'll 'ave to call on the Foreign Office. They can break down that 'ere cipher in two or three 'ours at most. Werry good."

With a wheezy sigh, Solomon took the message and sought out a telephone, where he presumably read it off—to whom?

The Foreign Office? Carson was startled. Well though he knew the extent of this little Cockney's resources, this seemed a bit stiff. After a time, Solomon returned, wiping his rotund visage, and resumed his pipe and chair.

"We'll 'ave it later, sir. Werry lucky it was as you got me message in time to show up. That 'ere Sir Basil is a-going to think some snatcher copped 'is wallet, and won't get aroused, so to speak. Them 'ere Foreign Office experts is wonderful wi' ciphers, Mr. Carson. They can't take a 'and with us, of course, but they're always glad to give me a bit of 'elp. And if we don't act quick, that poor girl is dead and damned, just like that."

"Are you serious?" Carson's gray eyes were startled.

"Yes, sir; serious is the word, as the old gent said when 'e kissed the 'ousemaid. Sir Basil is the worst scoundrel in Europe, and 'is ruddy friends are the same."

"But he's a famous man, John!" exclaimed Carson. "And look at that newspaper—look at the list of people on the yacht! World-famous musicians, nobility—"

"All bluff, just like that." Solomon swept his pipe in the air. "What makes it bad is that Sir Basil knows she 'as asked me for 'elp. Lucky 'e don't know me by sight. If I ain't mistook, 'is errand in London now is to try and get a line on me."

"Can he do it?"

Solomon nodded. "There ain't much 'e can't do, sir. Money, brains, and no scruples whatever; that's 'im. What 'e goes after, 'e gets; that's 'is boast. You see, sir, she was afraid of it. A month ago she asks me for 'elp. I 'ad known 'er father, the last Duke, and I 'ave some of 'er money now, taking care of it for 'er, so to speak. I told 'er to let me know when the time come. Poor girl, she got off word too late."

Carson was by this time really alarmed by Solomon's reference to the Duchess.

"What kind of trouble is she in?"

"Dang it, we can't talk 'ere," said the other irritably. "I don't like these 'ere questions. Come along; we'll take a cab 'ome, sir. We can't do nothing until we find what's in that 'ere message from Calais, anyhow. And I'll 'ave to get some men to work down along the docks. If that 'ere yacht don't come no farther up the river than Tilbury or Greenhithe we'll 'ave our work cut out for us."

Paying for their untouched drinks, they left the place and in the Strand caught a cruising taxicab, whose driver went wild with enthusiasm at receiving an address in Limehouse—a long run for a city job.

Once settled in the cab, Solomon relapsed into a brown study, apparently without the slightest intention of doing any talking.

"All right." Carson caught up the speaking tube. "I'm getting out. I took the job, but I'm not taking any job where I don't know what's going on. You and your duchess can go to thunder, for all of me. I'd probably fall in love with her anyhow, from her looks—I never did see a girl who was so attractive. So long. Get somebody else."

And he ordered the driver to pull in at the curb.

Solomon woke up. "Dang it, 'ave you gone off your 'ead?" he cried out in some agitation.

"No," said Carson. "You don't seem to want to tell me what's wrong with her—"

"Dang it, I don't know!" said Solomon earnestly.

Carson sniffed. "You don't know? And you're holding a lodge of sorrow over her, calling her dead and damned and so forth? Don't give me any such nonsense."

"That is the God's truth, sir!" Solomon exclaimed. "I don't know, just like that. All I know is it's something 'orrible. The woman said so when she called me up last night."

"What woman?" snapped Carson.

"Why, 'er personal maid, sir. I sent me men to fetch 'er. She 'ad come from Naples by air to find me. That's why I told you then we 'ad to jump. I ain't talked with 'er yet. She's 'ad a collapse. She's in my 'ouse now, I 'opes, and we'll 'ave a talk with 'er."

Carson told the chauffeur to drive on. Then he sank down and regarded Solomon with a grim expression.

"And you've gone clear off the handle, turned pickpocket, and scurried around like a chicken with its head off—all on account of something you don't know about?"

"Yes, sir," said Solomon; but his placid blue eyes twinkled slightly. "I 'ave me own way of doing things, Mr. Carson."

"So I'm learning," Carson rejoined tartly. "Under the circumstances, any sane person, it seems to me, would call the police to act. Why not drag in Scotland Yard?"

"So I did, sir, so I did, and a werry black eye was all I got for me pains," said Solomon. With a wheezy sigh, he produced a sheaf of telegrams. "Look 'ere. I 'ad the Yard get in touch wi' the French police at Calais—but see for yourself, sir."

These telegrams, none of them more than three hours old, told their own story. John Solomon was right. So far as Scotland Yard was concerned, he had received a very black eye indeed. For, acting upon his plea, the Yard had caused the French police to board Sir Basil's yacht at Calais that same morning.

They had seen the Duchess of Furstein. And, with great indignation, she had resented their importunity, scoffed at the idea of anything wrong, sent them about their business. The resultant comments to John Solomon from the Yard were polite but frigid.

Carson whistled. "Why, John, this knocks all your cock and bull story plumb in the head."

"Yes, sir," said the other morosely. "That's what Scotland Yard says, sir."

"And Scotland Yard is right about it."

Under his breath John Solomon muttered something about Scotland Yard that was neither frigid nor polite.

CARSON turned abruptly to his companion.

"John, didn't you say that woman should be at your house by now? Well, I telephoned an hour ago, when I got your note. No one answered."

Solomon gave him a startled look, then caught up the speaking tube and ordered the driver to head in at the curb and wait. They were in a dingy street of Stepney.

"Dang it, I might 'ave knowed it! I've 'ad a dozen things on me mind; I'm a-getting old and no mistake," he muttered. Then he turned and laid his hand on Carson's knee, and spoke earnestly.

"I'll 'ave to move werry fast, sir. Mr. Carson, it ain't often as I goes outside the law, so to speak, but in this 'ere case it's got to be done. You see for yourself what Scotland Yard 'as to say about it. I don't pretend to know what 'appened at Calais, or why she turned off them French police like that—"

"Are you going ahead with this thing?" demanded Carson, frowning.

"Yes, sir, I am, just like that. And we'll 'ave the law dead against us; and if so be as we slip up, there's no 'elp for it as I can see. English law ain't to be sneezed at, sir."

Carson nodded. Pull or no pull, if the laws of England nipped John Solomon, he would be nipped. That's all there was to it.

"Then we mustn't slip up, John."

"You ain't backing out?"

"Not much. I believe with the Yard that you're on a false trail, and this whole thing is a lot of hooey. It's been proven by what happened at Calais. But at the same time, John, if you said black was white I'd put my money on your say-so. Only," and Carson paused, thinking of that girl's picture, "I want to know a few things."

"All right, all right, dang it! There's a mortal lot I want to know too." Solomon opened the cab door and prepared to descend. "I'm a-getting out 'ere, sir. If I ain't mistook, I've got work to do in a 'urry. You take this 'ere cab and go to the old 'arbormaster's 'ouse. Do you know it?"

"Never heard of it."

"The 'arbor-master 'as brand new offices now in Trinity Square, but this 'ere is the old Port o' London 'eadquarters. You can still get permits there. I'll telephone about it from that corner pub yonder. Get general permits to enter the docks, for you and me both. When you get them passes, come back to me shop, sir, and watch your step. There's mortal bad deviltry afoot, but I'll know more about it when you show up. Dang it! If they've gone and murdered that poor woman—"

"Murdered her? The duchess?"

"No; 'er maid. They'd want to shut 'er mouth. I should 'ave gone after 'er meself instead o' sending them men o' mine, but I've been busy. Well, sir, good luck, and don't talk to no strangers."

With this apparently jocose admonition, Solomon got out and slammed the door. He told the driver to take Carson to the house of the harbormaster, and stamped away. The cab meandered on toward the Thames, through the narrow lanes of Limehouse. It halted abruptly. Carson got out and paid off the driver. Then he lit a cigarette and stood looking around. No need to ask his way here.

He was plunged suddenly into a new world, here in the ancient heart of Limehouse. He had supposed vaguely that the enormous London docks, the greatest port in the world, were something worth seeing; he had yet to learn the truth of that. But here, in a backwater of the river life, was the central authority of all this vast port system—the house of the harbor-master of the port of London.

THE huge letters on the curved front of the house told him

so. Its wide verandas overlooked the water, a flag flapped gayly

above in the dim morning sunlight. All about were crowded old

tottering houses half falling toward the ugly graveled beach,

warehouses, boat sheds, barges half built, in a confused

mass.

Carson paused, taking in the wide sweep of the river. Here, unexpectedly, he had a glimpse of what London docks really meant, for the tide was right and the shipping was all in motion.

The river ran between huge, high banks. A little before, there had been no sign of any docks, but now the enormous gates were swinging, up and down the stream, like unguessed doors opening on fairyland. There behind the walls, there among the houses and factories and warehouses, lay London docks, unseen and unguessed of any who passed by.

Turning into the pleasant building, Carson found few people about; it was still a bit early in the morning. He inquired his way, and presently found himself seated in a most attractive office where a coal fire burned in the grate, and a grizzled man wrote out the passes. Yes, Mr. Solomon had telephoned about them. Unusual, of course, but in his case quite all right.

With the passes in his pocket, Carson emerged again into the dirty, unkempt streets of Limehouse, heading for the shop which served John Solomon there as a blind for his own house behind.

He turned into Reach Road at last, a street of strange foreign peoples, from Hindus to Chinese, ugly grog shops, slatternly rooming houses. Ahead of him loomed his dingy and unwashed destination, a shop over whose door was the sign of John Solomon, chandler.

As Carson approached, this door opened and a man came out. Amazed as he was, Carson instantly checked his pace and halted, ostensibly to light a cigarette. For this man was the same whose pocket Solomon had picked—Sir Basil Lohancs, cane, silk topper and all.

He turned and surveyed the dingy shop with a puzzled frown. A frowzy fellow in the cap and coat of a coster slouched across the street and addressed him, evidently for a match. Sir Basil handed him one. Carson, watching, fancied that a few words passed between them. Then Sir Basil turned away and strode briskly toward Carson, who had now become interested in the contents of a shop window.

Sir Basil halted abruptly.

"Look here, my man," he exclaimed to Carson, "I wonder if you can tell me anything about the man who keeps that shop yonder—"

His words died, as Carson turned. A sudden light blazed in his dark, powerful eyes.

"Ah!" he said. "I remember you. Yes; you were the man outside that tobacco shop. Following me, are you?"

For an instant Carson was utterly astounded. He was sharply wakened to the truth of Solomon's words about this man.

Sir Basil had seen him for a moment only, apparently had paid no heed to him there outside the tobacco shop; yet now, at a glance, knew him again. Was this why Solomon had so hastily sent him to the pub in Chancery Lane? All this flashed through his head, even as he smiled, attempting no evasion.

"Yes, I don't mind admitting it," he rejoined easily. "Is it any crime to follow you?"

"It's an impertinence at least," said Sir Basil. "And you appear to be quite brazen about it. You know my name?"

"My dear Sir Basil, you're an important man in the world, and following important men is my business," said Carson affably. Long ago he had learned that the best offense to any attack is the unexpected. His easy assurance took the older man aback.

He appraised Carson with one swift glance.

"I fail to follow you, sir," he said crisply.

Carson chuckled.

"No pun intended, I trust? Come, come. Sir Basil! Sorry I haven't a card. Carson is the name; Amalgamated Press. You'll not be too hard on me, I hope? To tell the truth, I recognized you in the Strand, and followed you here. I'd been on the look-out for you, of course. We want to get a story about this yacht of yours—and then there's this affair of the Strand this morning. Your pocket was picked, I believe?

"Perhaps you'll do me the honor to give me a few moments. I'm really most anxious to get an interview with one of your guests aboard the yacht, the Duchess Alixe. You saw her picture in the Post this morning, perhaps? Surely you have no antagonism toward the press—"

As he rattled all this off with glib tongue, Carson watched the effect of his words, and was delighted. The angry tension in the other man's face relaxed. Here all Sir Basil's questions and suspicions were answered in a very natural and affable manner, even before he had any chance to voice them.

"Hm! Amalgamated Press, eh? I've a notion to report your impudence to your general manager, Rothstein."

Carson grinned. "Good! That'll give me a step up. Seriously, Sir Basil, I had no intention of annoying you. I'd be only too glad if you'd give us a short statement in regard to present industrial conditions on the Continent, and arrange an interview for me with the Duchess. If you want nothing said about this affair in the Strand, of course I'll comply with your desires."

The dark, powerful features cleared. "Very good. Carson, I think, is the name? Come to my rooms at the Ritz this afternoon about three. I'll have the statement for you, and shall see what can be done about the interview. And now, perhaps, I may be permitted to go on my way alone?"

"By all means; and thank you," said Carson, laughing.

With a nod Sir Basil strode away down Reach Road, turned the next corner, and was gone.

Hesitating, Carson glanced about for the coster, but there was no sign of that frowzy individual anywhere. After all, he might have been mistaken, probably had been mistaken, in imagining anything between that man and Sir Basil; the fellow might have been begging for money as well as for a light.

None the less, he passed by Solomon's shop, looked in the windows beyond, then came back and entered the dingy place. A bell tinkled as he stepped in. All about was a litter of cable, anchors, ship's paint and other supplies. A slender, darkish young man approached; this was Mahmud, who kept the shop.

"Good day, Mr. Carson. Go right on through; you know the way."

With a nod, Carson threaded a path through the jungle of stuff and gained a door at the rear. This admitted him to a dilapidated little office; a door beyond stood open, and Carson found himself in John Solomon's actual office.

It was empty.

Before the desk was a swivel chair, on the desk was Solomon's old clay pipe and a new plug of black tobacco. There was no apparent opening in the room except the one door by which Carson had entered; he was not sure just where the other door lay, behind the magnificence that hid the walls.

In this one room were treasures to make a collector's mouth water. On the floor was a sixteenth century Isphahan carpet, perfect and glorious.

The walls were entirely overlaid by rare Chinese tapestries of woven silk.

Against these curtains, on tables, on the desk, everywhere in the room, were weapons, jades, vases, jewels of every description, all oriental and all priceless.

One of the tapestries was waved aside. A door opened, and Solomon came into the room.

"Oh, 'ello!" he exclaimed warmly. "So you 'ad a chat with 'im, sir?"

"Eh?" Carson started. "How the devil did you know that?"

Solomon chuckled wheezily, took his seat at the desk, and began to whittle tobacco from the plug into his hand.

"I've been keepin' me eye on the street, so to speak, Mr. Carson. It pays to keep your eyes open, as the old gent said when 'e kissed the 'ousemaid. A werry sharp man, that 'ere Sir Basil. Think of 'im a-following me 'ere, quick as that!

"But 'e was a-runnin' down John Solomon, and 'e run 'im down. Bless 'is black 'eart, 'e don't know yet as I'm Solomon. What did 'e have to say, sir?"

Carson recounted the conversation. Solomon stuffed his clay pipe, puffed it alight, tipped his chair back, and fastened his mild blue eyes steadily on Carson.

"And I s'pose you think, sir, as 'ow you fooled 'im completely."

"Naturally. I've an appointment for this afternoon at the Ritz—"

"And I went and told you once as 'ow 'e ain't stopping at the Ritz, nor Brown's, nor nowheres else, but the Cecil. Recognized your face, 'e did. This werry blessed minute, what's 'e doing? Looking of you up. Finding there ain't no Carson with the Amalgamated Press. Well, did you get them 'ere passes?"

"Yes." Carson laid them on the desk. Solomon seized and pocketed them.

"By the way, Sir Basil was in your shop, wasn't he?"

"And 'e didn't get no satisfaction out o' Mahmud."

"When he came out, a man who looked like a coster asked him for a light, came from across the street. I thought some words passed; but after Sir Basil was gone, there was no sign of the coster."

"That 'ere chap," said Solomon complacently, "'as been a- watching of the shop for the past 'our. Werry good, Mr. Carson; you're a-coming on. You stay with me long enough and you'll know a lot, as the old gent said when 'e 'ired the pretty 'ouse- keeper. That 'ere coster ain't gone away. 'E seen you come in. No use thinking Sir Basil ain't on to you now. Ah! Dang it, now we're a-going to get somewhere!"

The telephone on the desk had rung sharply. Solomon answered. A faint hint of excitement came into his voice. He seized a pencil and began jotting down notes.

"Thank you werry much, sir. What's that? Yes, indeed, I'll keep me 'ands out of 'is affairs; a werry bad customer 'e is."

He hung up, and chuckled wheezily. "Warned me against Sir Basil, they did."

"Who did?"

"The Foreign Office, sir. This 'ere is the decoded message."

Carson seized the sheet of paper thrust at him, examined it hastily. Somewhat to his disappointment, it turned out to be very prosaic:

STEAM STEERING GEAR IN URGENT NEED OVERHAUL AND REPAIRS REQUIRING AT LEAST A DAY. ARRANGE TO BE DONE LONDON OR CANNOT ASSUME RESPONSIBILITY.

DEVRIES, MASTER.

"Eh?" Carson glanced up. "Just what does this mean?"

"What it says, just like that, sir. Devries is the cap'n of the yacht. I'll 'ear any minute now just where the Nureddin will be docked; that's 'er name."

Carson laid down the paper.

"Well, we're doing a lot of shifting all over the ring," he said, irritated, "and still I don't know any more about the whole thing than I did."

"You're a-going to learn, sir, and so am I, in a werry few minutes," Solomon rejoined, placidly puffing at his pipe. "And then we're a-going to get out of 'ere werry fast. It ain't 'ealthy. That 'ere Sir Basil 'as got on me nerves, and werry sorry I am to say it. That 'ere man don't stick at nothing."

"Nonsense. Are you trying to tell me that a man of his caliber, his wealth and standing, is an arrant scoundrel?"

Solomon grunted. "Worse'n that, 'e is. And 'ow did 'e get 'is wealth, except by bein' a scoundrel? But right now. Sir Basil 'as a mortal lot of influence and power, so watch out. Yes, we'll 'ave to move fast."

Again the telephone rang. Solomon spoke, listened, and hung up with a grunt.

"Coming into the dock now, she is. Newbegin Overhaul Docks, right close to the old East India docks—and not so far away from 'ere, neither. Oh, 'ello!"

The tapestries swung aside. In the opening appeared, to the astonishment of Carson, an elderly man clad in the white apron of a surgeon, Solomon glanced up.

"Well?"

"She can't last long," and the other shook his head. "I've injected adrenalin; if you want a word with her, come along. She'll probably be able to talk in five minutes or so."

"Mr. Carson, this is Sir 'Enry Macnaughton of Harley Street," said Solomon, laying his pipe aside and rising. "Werry good of 'im it is to give us a 'and with this 'ere poor female—"

"What!" Carson remembered suddenly. "You mean the woman you spoke about? The maid of Duchess Alixe? Is she here, then?"

"Yes, sir, me men got 'er 'ere after all, but she's in a werry bad way indeed, 'cause why, somebody else got to 'er afore us."

The famous Harley Street surgeon swept Carson a keen glance, and a nod.

"Poison," he said curtly. "Better come along. My assistant has her in charge."

Carson rose and accompanied them, with a sickish feeling.

"WHO got ahead of you? Sir Basil?" muttered Carson, as he passed with Solomon into a corridor that led to the house proper. The pudgy little man nodded gloomily.

"Yes, sir. That 'ere man 'as agents and spies all over. Look what 'appened wi' that poor woman! In there, she is. That's 'er 'usband with 'er."

They paused in a doorway. The surgeon went on to speak with his assistant at the bedside. The woman lying there, a woman of forty, was still unconscious. Standing watching her, eyes unmoving, features rigid, was a grotesque little dried-up man, not over five feet six, shrunken and wizened, but with immense sweeping mustaches. He looked like a gnome dressed in street clothes. He was the head gardener of the duchess, his wife was her maid.

As Solomon murmured in the ear of Carson, upon finding their mistress gone, the pair had gone to Naples, then to London by air. Devoted to their mistress, their sole hope was to find Solomon, whom Duchess Alixe had mentioned more than once to her maid. Reaching here the previous evening by air, they had telephoned him. A car had picked them up at Croydon airport, presumably sent by Solomon, but had taken them to a cheap Italian boarding house where they were told to wait for him.

When Solomon's men finally ran them down, in the early morning hours, the woman had been poisoned, was unable to talk. Solomon imparted all this in a few brief words, caught the attention of the grotesque fellow, whose name was Merlin, and beckoned. The man approached the doorway and Solomon addressed him in very fair Italian.

"Do you know what your mistress feared?"

"No, signor. My wife did not tell me. It was something about Sir Basil Lohancs. And at that boarding house last night, I heard his name mentioned." A flash of ferocity came into the shriveled, grotesque face. The big mustaches quivered. "He has done this, he has done it! If I can find him—"

"Never mind." Solomon brushed him aside, 'the surgeon was beckoning. They all three crossed to the bed. The woman had just opened her eyes; Merlin sank on his knees and caught her hand, with a passionate cry, but she stared up at the others.

"Signor—Signor Solomon!"

"Tell me," said Solomon. "What Is wrong?"

"The yacht!" cried out the woman, her pallid face flashing into life. "They have a doctor aboard! Vecchini, the poisoner, who escaped from prison. She will die, I tell you—she will die—"

A pitiful whimpering cry of pain was wrenched from her, she quivered spasmodically, and then she relaxed. Her eyes closed. MacNaughton caught up her wrist. A cry broke from Merlin, a storm of sobs as he realized that she was dead. And her story remained untold.

"A serious matter, Solomon," said the surgeon slowly. "My report, you know—"

"All right. Get 'old of Inspector David o' Scotland Yard," said Solomon promptly. "You might take this chap Merlin there. Let 'im tell 'is story, then send 'im back 'ere. I'll take care of 'im. Inspector David can 'andle the matter."

Carson went back to the office, frowning, agitated by what he had just witnessed. Solomon presently appeared and sat down to the telephone.

He put through a number of calls. Then, with a wheezy sigh, he swung his chair around to face Carson.

"Confound it!" said Carson, meeting the mild blue eyes. "Do you realize that woman might simply have died of ptomaine poisoning?"

"That's what Sir 'Enry says," Solomon admitted, holding a match to his pipe. "Only an autopsy can tell for sure. So I expect as 'ow Scotland Yard ain't a-going to make werry much of the matter, sir."

"And still you've nothing to go on but some hearsay talk. Why, it's absurd, sir."

"That 'ere woman died tryin' to save 'er mistress, Mr. Carson."

The American drew a deep breath.

"All right. I'll see it through with you. As for Duchess Alixe—"

"She's aboard that 'ere yacht, sir," said Solomon, eyeing him steadily. "The master, Devries, is English; the crew is French and Italian. And she's a-going to be killed if we don't 'elp 'er. Do you understand?"

"Certainly, to some extent; but what I understand simply can't be credited," Carson rejoined bluntly. "You say that Sir Basil had this poor woman poisoned. She tells us that the duchess is in the hands of some rascals who intend to drug her, poison her, kill her. Do you expect me to believe that a man of Sir Basil's position and standing would be back of such nonsensical business?"

Solomon appeared irritated.

"It ain't nonsensical," he said sharply. "As for standing, Sir Basil ain't got none, so to speak. Put out o' the Royal Yacht Club last year, 'e was, for crooked work. Crazy about jewels, 'e is, fair mad about 'em, sir. It's the main thing in 'is life. Maybe you know 'ow a man like 'im will go after jewels?"

Carson nodded. So this was it! Such a consuming passion, in such a man, would explain many things. He thought again of that dark, powerful face, and realized that this man might indeed stop at nothing.

"What's that got to do with the Duchess of Furstein?" he demanded.

"Didn't you read that 'ere newspaper this morning? She 'as the Furstein emeralds, the greatest lot o' green stones in the world. She 'as plenty o' money; no reason for 'er to sell them emeralds. To get 'em, Sir Basil would commit murder a 'undred times over, sir. Murder don't mean nothing to 'im."

"But to murder a girl, a lovely creature like this duchess—"

"That's 'is way. Women don't mean much to 'im, sir. That 'ere man 'as women all over Europe; buys 'em like 'e does jewels, but 'e don't keep 'em. An animal, Mr. Carson, as 'as shoved 'is bloody way to the top of the 'eap. Jewels is 'is one great passion, so to speak."

"But," said Carson slowly, "she must have known what sort of a man he is. How did he get her aboard his yacht? Is she kidnapped?"

"More or less, I expect." Solomon shook his head. "But that don't matter. She's there, and your job is to get aboard and see 'er, and werry sharp about it. I 'ave me own plans for comin' aboard meself, and I'll get there later on."

"But what'll I do, providing I do get on the yacht?"

Solomon regarded him blankly. "I ain't got the faintest notion, sir. We can't tell a blessed thing till we see 'er. But I 'ave a letter asking me to 'elp 'er, and that letter may save our necks if we slip up. You see, I knew 'er father well, and was agent for 'im. We'll 'ave to use our 'eads, just like that. And maybe more than out 'eads, too."

Pulling at a drawer of his desk, Solomon took out a small Browning and passed it over. Carson pocketed the weapon and frowned slightly.

"No plan, you say? Do you realize how impossible it is for anyone to get aboard such a craft as that, guarded as she must be at every point?"

"There ain't nothing impossible, sir, if so be as you 'ave a 'ead," said Solomon. At this moment the shop door swung open and Mahmud appeared.

"Effendi, a man is here by your command—"

"Show 'im in, dang it!" ordered Solomon rather testily.

A moment later, into the room came a middle-aged man who had the air and dress of a shop foreman. He nodded to Solomon.

"Well, sir, I got here as quick as possible. The works are busy this morning."

"This 'ere is me friend Mr. Carson," said Solomon. "Carson, this is Don McCabe, general manager of the Newbegin works. Me and 'im 'ave knowed each other for a long time."

McCabe nodded to Carson. "A matter of fifteen years, Mr. Solomon."

"Werry good. That 'ere yacht Nureddin is a-coming into your docks on the tide."

"Yes; the owner called me on the telephone about her. Her steam steering gear needs an overhaul, I believe."

"Now, McCabe, you listen sharp," said Solomon. "There's a werry bad gang aboard that 'ere yacht, but that ain't your business. I want you to take Mr. Carson along with you, put dungarees on 'im, and get 'im aboard that yacht. Make your inspection, and report it'll take the best part o' four days to fix up that 'ere gear. And if so be as Mr. Carson loses 'imself aboard, you pay no attention."

McCabe whistled softly. "It's a good thing I know you to be no crook, Mr. Solomon! But I can't do such a thing as this. In the first place, the dock police are very strict, and I couldn't get Mr. Carson into the docks themselves without a pass—"

"We 'ave one," and Solomon produced the pass in question, handing it to Carson.

McCabe shook his head firmly. "Even so, it can't be done. If any questions were asked, and it looks to me as though they might be asked, it's as much as my job is worth."

"Werry good, McCabe," said Solomon placidly, and opened one of the desk drawers. He took out two large, fat envelopes, and handed one of them to the visitor.

"There's a thousand quid in twenty-pound notes. This 'ere is another thousand, to be yours after the work's done. Is it worth risking your job for or not?"

The man swallowed hard, peered into the envelope, and his eyes bulged. Five thousand dollars there in his hand, and as much more to be earned; it was next to incredible.

"You're damned right it is," he replied hoarsely. "But mind, if they know just what's wrong wi' the gear and that it won't take so long—"

"Then make something else wrong," said Solomon, with a chuckle. He swung back to the desk, and from another drawer produced a small box, which he handed Carson. "Better put on that 'ere false mustache, sir. Then you and 'im slip out the back way. It ain't far to the works from 'ere. Are you satisfied now, Mr. Carson?"

"More or less." Carson smiled slightly. "Do you know everybody in London, John?"

"Well, sir, I 'ave a pretty fair acquaintance," and Solomon nodded, a twinkle in his blue eyes. "It ain't knowing people as counts; it's 'aving them know you. Eh, McCabe?"

"Right you are, sir," affirmed the latter.

PRESENTLY Carson found himself striding briskly beside McCabe

up India Dock Road; and after that, things moved swiftly, with an

admirable precision. McCabe was an efficient man.

As by magic, the vast expanses of the docks were open to them, and they plunged into a world unsuspected from the river or from the city, a world walled in and girdled about with precaution. Great basins for anchorage, unending wharfs, godowns, warehouses, shops, dry-docks, a strident clangor of life in the heart of London yet utterly alien to it.

Wearing dungarees, a cap, his false mustache, Carson carried a kit of tools and followed McCabe to where a slim white shape was warping in beside an open wharf. As soon as the plank was down and the gangway rigged, McCabe strode aboard. The first officer halted them, heard McCabe's business, and turned to a seaman at his side.

"Take them to the bridge," he ordered in French. Carson noted that the men around were apparently Latins.

McCabe followed the seaman closely; Carson lagged, as they headed forward. He would never get another chance like the present moment, he knew. Men were passing and repassing, the decks were in confusion, a hundred things were being done. On the after deck, Carson had glimpsed three men in steamer chairs, watching the docks and being served by a steward in trim uniform.

An open door, a glimpse of steel gratings, of lower darkness—the engine-room hatch. Carson quietly slipped into the opening, waited a moment.

He peered out. McCabe and the guide had disappeared. No one was in sight hereabout. A few seconds later, Carson was back aft at another door. A passage; the saloon lounge opened before him, empty. A stairway at the forward end; he took a chance, descended. Ah! The cabins, spick and span, luxurious.

Carson hesitated, alert, poised. Which way? Any port of refuge, temporarily, would do. Down the passage he observed two large vases of flowers, set outside a door. The quarters of the duchess, no doubt. He approached, came to a side passage—suddenly ducked into it. The door ahead had opened. A woman emerged, humming a light tune. She came past the passage where Carson stood immobile against a wall. He had a glimpse of her face, framed in yellow hair; a young, impetuous, crafty face. The uniform of some sort, perhaps that of a maid. Then she was gone, without seeing him.

A man's voice was uplifted, close by. Carson started, glanced about. A door was almost at his back. He tried it, looked into the empty cabins, stepped in and closed the door. With a breath of relief, he set down his tool kit.

Here were two luxurious cabins, one a lounge, in which he was, the other with two brass beds. Occupied? No, thank heaven! The closets were empty, no personal effects in sight. A door in the bedroom wall caught his eye. He calculated swiftly; this door must communicate with the adjoining suite.

Excellent! His pulses leaped. Then he had the duchess within reach! He quickly got out of his dungarees, beneath which were his own clothes, hung them in the closet, put the kit of tools with them. The false mustache, he left. The cap went into the closet. He had half-closed the door to the outer lounge cabin. He now approached that in the wall, tried it softly. It was locked; but the key was in the lock. He turned it—and hesitated. The full enormity of his act came sharply into his mind.

It was noon and past. At an early hour of this same morning, the duchess had angrily repelled the French police. If she did the same thing now, Carson very well knew he would suffer. After all, it looked as though Solomon were on a wild goose chase.

With a shrug, he tried the door, opened it a bare crack, peered into the cabin beyond. Then he was thankful he had made no sound. Back to the door, a man was standing there speaking, not three feet away. Carson, as he softly closed the door again, caught the words.

"—regret, your highness, that I must ask you not to leave this cabin for the present. You are on the side of the ship away from shore; you cannot, therefore, communicate with anyone, and such efforts on your part would only force me to take unpleasant steps."

"But this is intolerable!" cried a high, clear voice, a woman's voice. Carson closed the door. He glanced over his shoulder, startled. He was caught beyond escape.

Men were coming into the adjoining cabin, the lounge by which he had entered this suite.

FOR an instant he stood petrified.

"This will do very well," said a man's voice in French. "It is unoccupied."

Steps sounded in the adjacent cabin, chairs were moved about. Carson caught the pistol from his pocket. If they came on into this cabin, he was lost.

Yet through his brain flashed, in exultation, the brief dialogue he had just overheard ere the door closed. So it was all true, all of it! That was her suite. She was a prisoner there. Solomon had been right!

"Well, why the secrecy?" came the impatient question from the outer cabin. The door was ajar between; every word reached Carson clearly. "Why not talk on deck, Vecchini?"

A man laughed, curtly. "With that steward around? Nonsense. Sir Basil will be aboard in an hour or less. What explanation am I going to give him?"

"Tell him the truth."

"Bah! Here, give me one of your cigarettes."

Carson relaxed, put the pistol out of sight. They were not coming in here, then. And this must be the Italian doctor mentioned by the dying woman.

"Now, Dufour, listen to me," went on Vecchini. "Excuses do not go with Sir Basil. We had our orders. You became soft-hearted; so, I admit, did I. To drug that beautiful creature, that charming specimen of womanhood, before reaching England—well, I have put off doing it. I have listened to you."

"It seemed absurd, a monstrous thing," returned Dufour, evidently a Frenchman, in a gloomy voice. "She could not escape; why fill that glorious body with drugs, why ruin one of the most perfect women imaginable with morphia and render her an insensate thing?"

"Because those were our orders. That was why we came aboard here, received our money."

"What can he do?"

"Kill us, you fool. Don't you know he has no heart, no soul, except for those damned glittering stones? They have robbed him of all human emotion."

The other grunted. "Suppose we open a port in the next cabin. It's close in here—"

Carson thought of the closet—it was across the room. A chair scraped. Another moment and one of them would be in here. His hand, still on the knob of the door, turned it. Again he opened it slightly. Silence now, except for a stifled sob.

Swiftly, he chanced everything, opened the door, passed through, closed the door again. Then he turned.

There was a startled gasp. One other person in the cabin; a woman, sitting at the table, her eyes widening upon him. The duchess herself—no mistaking that face, the face of a lovely girl, but tenfold more lovely than the newspaper likeness. A door stood open behind her, the passage to a bedroom cabin.

With one swift gesture of reassurance to her, Carson stepped swiftly to this door and closed it. Almost at once, a sharp rap came on the panel. A woman's voice sounded, calling.

"Madame desires something?"

Carson made a despairing gesture, but the woman at the table understood. She lifted her voice in reply. Her distended, startled eyes did not leave the intruder.

"Nothing. Leave me alone."

With quick relief, Carson turned, approached her, and smiled.

"My name is Carson, madame; I have come from John Solomon. Thanks—you saved the day splendidly, just now; I was nearly caught. You speak English, I think?"

"Naturally, since my mother was English. Oh, I cannot believe it!" she broke out abruptly. "Where is Mr. Solomon? Here?"

Carson shrugged. "I don't know where he is. He sent me aboard here to see you if possible. Why on earth did you send the French police packing this morning?"

"The French police?" Astonishment, perplexity, filled her features. "But, my friend, I don't know what you mean, I assure you—"

"We had the French police come aboard this yacht at Calais, early this morning. You saw them, stated emphatically there was nothing wrong, that you wished no interference."

She gazed at him steadily for a moment, then her eyes widened. "Oh!" she said slowly. "So that was it! That maid, Therese—yes, I see now. She came in very early and took one of my gowns, my coats—oh, and I remember there were voices outside. The police, eh? Then she saw them, pretended to be me. Yes, she could have done that."

Carson, startled, saw that she had hit it. The yellow-haired woman he had glimpsed must be this Therese. Probably the Calais police had no picture of the duchess and accepted as true whatever was told them.

"Clever crowd you have aboard here," said Carver. "Well, if you want help, I'm here. Do you want to get away?"

"Do I want—oh, if you only knew!" she exclaimed. "This terrible ship, these unspeakable men! And Sir Basil the worst of them all—"

"He'll be along soon," Carson said. "We've no time to lose. If they catch me aboard here, I'm sunk. Wait; what's that?"

A noise at the door, a woman's voice. Therese, no doubt.

Carson saw an open closet door. He darted to it, stepped in, made a gesture of cheerful reassurance to the duchess, and drew the door shut. He could hear nothing.

Splendid girl! No fuss; yet she had been crying when he entered. Sharp as a whip, too. She had seen the explanation of that French police blunder in a flash. No wonder Sir Basil had wanted her safely drugged before the yacht reached England.

Suddenly the door swung open. She stood there, eager, alert, poised for action.

"All right, Mr.—what is the name? Carson, yes. They've gone. I've locked the door. What am I to do? How can we leave, get ashore, anywhere?"

Carson, emerging, saw the table set for luncheon with a glitter of silver and glass. He glanced at the cabin ports. Over the outside of each one was a stout iron bar, effectually banishing any thought of escape by that means. Then he recollected the adjoining suite, and his eyes lit up.

"We've no time to fool around," he said rapidly. "I can jump overboard—looks like the only way. You can't. If you stay here while I make my getaway and bring the police—"

"Wait!" she exclaimed sharply, coming close to him, speaking tensely but not loud. "You don't understand. Sir Basil brought me to hear the great pianist, Ludovics, play. It was a lie. He was not aboard at all. I drank some water; it was drugged. I know little of what happened. I was bewildered, stupefied, helpless. They told me to sign papers, give up my emeralds, and I did everything they asked. It was like an evil, monstrous dream. Long before, I had been given warnings that people were after my emeralds. That was why I tried to get word to Mr. Solomon."

"Well, you're all right now," said Carson, with more assurance than he felt.

"But I cannot stay here and let you go," she went on, desperation in her eyes. "I am in terror of that man, Sir Basil; no, no, we must both go ashore at any cost!"

"All right," said Carson briskly. "I suppose the officers are in on the game?"

"The captain, of course. Probably the others. I don't know what they think would happen here in London—"

"Hold on." Carson swung around and went quickly to the door of the adjoining suite. He gripped the knob, opened it softly. The two men were still there. From the cabin beyond he caught the voice of Vecchini, shrill and petulant.

"It's true we were soft about her; but we'd better wake up. Why did Sir Basil leave us at Gibraltar and come on here alone? I don't like it. That marriage ceremony should have ended the whole business! It's absurd to use drugs on a lovely creature like—"

"You've been drinking too much, Vecchini," came the voice of the Frenchman.

Carson, despite his nervous tension, could not help listening for more. A glance showed him that the girl had caught the words and was listening, sudden wild alarm in her face. Dufour went on speaking.

"Give up the liquor, you fool. You're a fine one to shrink from drugging a girl, just because she's pretty."

"Speak for yourself," growled Vecchini sulkily. "You started it. We'd better do it before he comes aboard. I tell you, I'm afraid of him!"

Carson could picture the Italian—weak, criminal, yet so impressed by the beauty and fineness of this girl as to be unable to complete his infernal work. But now, with Sir Basil at hand, swift terror had risen in him.

"Bah! Be sensible," Dufour returned. "She's his wife. The law can't touch him or us either. You should know that in England a man can beat his wife, do what he likes; she's his property. All Englishmen are brutes. Everything was made safe by that ceremony. Even if she makes a fuss later, who'd believe her? You know he came on here to present the proofs of the marriage and the receipts she signed, and get the jewels that are here in London. Come along on deck. Let's find how long these repairs will keep us here."

A SCRAPE of chairs, the slam of the outer cabin door. Carson,

feeling as though a cold hand had gripped his neck, turned and

looked at the Duchess Alixe. She was white as death. Despite the

urgency of their case, despite the peril on every side, what he

had just heard overbore everything else in Carson's mind.

"Is it true, what they said?"

"I don't know, I don't know," she said in a low, dead voice. "It was all a trap, of course. Everything is so confused in my mind—"

"Were any of your jewels here in London?"

"Yes. Some of the unset emeralds were being made into a necklace. Other settings were being repaired."

"Good Lord! I begin to see light," muttered Carson. "What about the marriage they mentioned? Was there a marriage?"

She flinched.

"Yes—there was something—I thought I had dreamed it! Therese laughed at me when I spoke of it. Oh, I tell you I don't know what happened, I wasn't myself at all. Marriage! If it—if it were not a dream—"

She lost her poise, broke into almost incoherent phrases, then shrank back in her chair and was silent, motionless. Suddenly anger rose in her eyes, color in her cheeks.

"He would dare they would dare—do such a thing!" she broke out.

"Listen, young lady; keep your head. You need it," exclaimed Carson. "How much are those emeralds of yours worth, in cash?"

"I don't know. A million—two million, I think."

"What, francs?"

"No, no; pounds sterling, of course. There are no emeralds in the world like them. Oh, what does all that matter? You must do something, get me away from here, help me! To think of what they have done, of what I have become—

"All right," snapped Carson. "Keep quiet. Let me think, will you?"

He went to the door, listened, found the adjoining suite apparently empty now. The two men had departed. He glanced at the ports there. No bars. Then, fumbling for a cigarette, he lit it and turned. The girl sat with her face in her hands, motionless.

Terror had gripped her, and no wonder. But to Carson had come startled dismay and a full comprehension of everything. Now, for the first time, this apparently absurd affair resolved itself into grim coherency. The melodramatic plot pointing out Sir Basil Lohancs as something like a madman, now showed itself as an unscrupulous but thoroughly shrewd bit of deviltry with a very definite aim.

A million, two million pounds—there was a stake worth playing for! And in jewels, for which Sir Basil had an inordinate passion. A diabolic but perfectly, safe scheme, too.

That marriage altered everything. Even if the girl had been carried off and drugged into signing everything, even if the marriage was in name only. Sir Basil was safe. Who would credit such a story, even did she live to tell it? Sir Basil's witnesses would brand it a lie. Not that it lay in Sir Basil's plans to let her do any telling, however.

Something of all this must have passed through the girl's mind also. Gradually she pulled herself together, until she looked up at Carson, then sprang to her feet.

"Out of here, out of here!" she exclaimed. "Helpless, yes; he will have false evidence, everything. What a fool I was to come aboard here with him! Yet I suspected nothing. Let me get away, help me, and I'll fight him, fight him, fight him in spite of everything!"

Her eyes shone like stars. She was suddenly alive with anger, with energy.

"Right," snapped Carson. "Keep your voice down, for heaven's sake! Let's go. They have the gangway guarded. Can you swim?"

"Yes. Miles," she said, tensely alert.

"Fine. Then we'll swim for it. All we need is to attract police attention, and the fight is on." Carson spoke jerkily, sharply, aroused to the passage of time. He glanced at her simple woollen sports costume. "You can't swim in those clothes. Strip—shoes, everything possible! I have some overalls; they call 'em dungarees here. Wait a minute."

He slipped into the adjoining cabins, empty now. Retrieving his dungarees, he came back and tossed them to her.

"Move fast! Get into these. I'll knock his whole game in the head if you get away now, if we start right in to raise hell with him. Later on, we'd not do so well. Kill you for a million or two million pounds, eh? You bet he would. Come on into the next cabin when you're ready."

He withdrew, puffing at his cigarette, wakened now to action. And, as the door closed, he saw her slipping out of her shoes, catching hurriedly at her dress. She was herself again.

Carson removed his own shoes, stripped to shirt and trousers. The port-hole was open, the round brass-bound glass flung far back; plenty of room for a person to squeeze through. He cursed under his breath at thought of it all. Marriage—probably a legal enough ceremony, even though she were drugged. Money, bribes, could do anything.

He went to the open port, looked out. This was the side of the yacht away from the wharf. There, not three hundred yards away, was anchored a tramp steamer, with two lighters at her gangway, booms and winches at work. Good! If they could make one of those lighters and hold any boat from the yacht until the Thames police came along, all would be well.

Carson felt a touch on the shoulder.

"Oh, hello!" he exclaimed, and turned. "Are you ready—"

To his utter dismay, he found himself looking into the eyes of Sir Basil Lohancs, who stood there within a foot of him. That was all he remembered.

TWO men had entered the cabin with Sir Basil. Dufour, whose hand had just struck Carson down, pocketed his slingshot, knelt, and drew the pistol from the pocket of the insensate American. He was a thick-set man, massive in build, with hard, square features. The second man was Devries, master of the yacht, a slim, wiry man of forty.

"Take him away," said Sir Basil. "Iron him and put him in a cabin for the present. We can turn him over to the police later on a charge of attempted robbery—I'll determine that when the time comes. Send those gentlemen of the press down here in five minutes."

The inanimate figure of Carson was lugged out. Sir Basil lit a cigar and glanced from the open port at the tramp steamer and its two lighters. The gardenia at his buttonhole lent his impeccably attired figure a hint of festive gaiety, belied by the powerful lines of his iron features and the smoldering fire in his dark eyes. Then he turned, as the connecting door opened and the Duchess Alixe appeared, now in the blue dungarees. At sight of him, she halted, a paralysis of dismayed recognition gripping her.

"Good day, my dear," and Sir Basil bowed to her. "A charming costume; but is it not a mere trifle indiscreet? In a moment or two there will be journalists here to receive the news of our wedding. If you will permit me to say so, I should prefer a more conventional dress."

Horror widened her eyes. She lifted a hand to her lips, checking an instinctive cry. Sir Basil smiled.

"Allow me to point out the unfortunate scandal that would ensue," he went on suavely, "were you to tell these newspaper men some wildly improbable story—especially in your present costume. You are at perfect liberty to see them, tell them what you like. In such an event, I should naturally be impelled to hush up the matter and have you committed to a private sanitarium for mental cases. In fact, I should be forced to do so. On the other hand, if you will retire to your own cabin, you will be quite unmolested there, and this evening I shall place a motor car at your disposal and allow you to depart with a man named Solomon. I do not know the person, but he is insistent—"

"Are you mad?" she cried out suddenly. "To do a thing like this, all of it—"

"Quite sane, my dear." Sir Basil bit at his cigar, with a curt nod. "You are my wife. Make the best of it. Now, take your choice. Do you wish to leave here to-night with this man Solomon, or shall you make a scene here and now?"

She stared wildly at him; then, with a low, choked cry, drew back into her own cabin and slammed the door. Sir Basil, with a quiet laugh, turned the key in the lock. He swung around at hasty footsteps. It was Dr. Vecchini, thin, pallid, with intense black eyes and a pointed black beard.

"Ah, Vecchini!" he exclaimed quickly. "I am pleased with you. It was fortunate that you disregarded my orders to give her a morphia course, for I have changed my plans."

The pallid face of the Italian lighted up. "Ah! Then you are not angry!"

"On the contrary; but I do not advise you to repeat the experiment of trifling with my orders," said Sir Basil. "Did you bring the photographs as I requested?"

Vecchini produced a large envelope, from which Sir Basil took a number of photographs, inspecting them with a nod of approval. Captain Devries entered.

"Dufour is bringing the pressmen, sir. Ready?"

"Quite," and Sir Basil smiled.

He received the half-dozen men who crowded in behind Dufour, in his most charming manner. They were excited, as well they might be; they had been invited to receive a news story of the first magnitude, so far as the London press was concerned. Presently Sir Basil waved aside their eager questions.

"Gentlemen, it is entirely true. Duchess Alixe and I were quietly married aboard this yacht at Palermo. I regret that she is at the moment indisposed after her voyage and cannot receive you. Here are the papers concerning the marriage, which I may say was purely a love match. Here are photographs of us, taken before the ceremony. Doctor Vecchini, who acted as best man, and I are now entirely at your disposal if you have any questions."

They had; questions entirely discreet and respectful, as befitted the English press. Sir Basil held back nothing, spoke vaguely of future plans, regretted that he and his bride were leaving London at once.

"Certain repairs necessary to the yacht," he said affably, "have changed our plans. We shall leave this afternoon for Scotland. I think you can pick us up at Glasgow, Devries?"

"Easily, sir," returned Captain Devries.

The interview ended. Sir Basil went on deck with his guests, saw them off, then turned to a man waiting impatiently.

"Well?" he exclaimed. "What have you learned?"

"Little enough, Sir Basil. The man Carson is an engineer, who has been associated with this Solomon recently. Solomon himself is a person of rather large influence—"

"I know all that," snapped Sir Basil. "But personally? Did you get a picture?"

"I did, sir—"

Seizing on the picture handed him, Sir Basil uttered an angry exclamation. A glitter came into his eyes; his dark features turned white with fury. This man, born in the Balkans, who had thrust himself into the front rank of industrial success and wealth, held in check behind his impassive demeanor a gusty torrent of human passions.

"That's the man who picked my pocket—and I let him go! All right. Have you located him?"

"No, Sir Basil. I've a dozen men working on it. He's not at his shop—"

"Your business is to find him; do it. And no excuses." Sir Basil turned away. "Vecchini! Come this way."

The Italian with the pointed beard accompanied him aft, and they took easy chairs beneath the awning there. A steward appeared, but Sir Basil waved him away.

"Now, Vecchini, pay close attention," he said. "That Carson is a fool; to think that a false mustache—well, never mind. Devries has put him somewhere, ironed. Look him up and give him a stiff injection that'll keep him quiet. To-night Devries can turn him over to the police, after you've gone."

"Gone?" echoed Vecchini inquiringly.

"Yes. I must get to the City at once and finish the business that brought me to London. It seems that the yacht must remain here four or five days, so I've changed all my plans. At seven o'clock to-night, I'll have a car here to take you and her away. Arrange with Therese to repeat the drug we gave her at Palermo. The car will take you both to an exclusive sanitarium in Kent, where private mental cases are treated. You'll remain as her personal physician and see to it that the usual legal phases of the matter are properly covered. Yes or no?"

"Yes, of course," said the Italian. "How long is she to stay there?"

"Indefinitely; until I send you a change of orders. You'll receive five hundred pounds a month and all expenses. Therese, by the way, will accompany you."

"Very well, sir. You may count on me," said Vecchini, his eyes shining eagerly.

"I'll return later in the afternoon, perhaps just in time for dinner." Sir Basil rose. "That's all. Ah, Devries!" He turned, as the captain approached. "You don't know yet how that fellow got aboard?"

"No, sir."

"You'd better have a care, Devries," and there was a sinister inflection in his voice. "I don't welcome incompetence, you know. Another slip, and you're broke. That's all."

When Sir Basil had departed, Doctor Vecchini went to his own cabin. There he spent a few moments in preparing and loading a hypodermic syringe, which he carefully carried out and down the passage. Before one of the cabin doors, an Italian seaman in the uniform of the yacht was standing at ease.

"He is in here, eh?" said the doctor. "Safe?"

The man held up a small key, with a laugh. "Handcuffs, signor. You wish to enter?"

Vecchini nodded. The guard unlocked the door for him and stepped back. Passing in, Vecchini saw the figure of Carson lying on one of the two beds, wrists handcuffed, eyes closed, no doubt still unconscious. At this instant, he caught a shrill whistle from the deck above, an outburst of voices, the swift thudding of feet. His nerves jumped. He laid down the syringe on the vacant bed, then darted back to the door and flung it open.

"What's happened?" he demanded.

The guard shrugged in ignorance. Vecchini hastened along the passage to the stairs, and so to the deck above. There he came upon a singular scene.

Near the gangway stood Captain Devries, facing a man who had just come aboard and who was now firmly held by two of the crew. An elderly, pudgy little man, his rotund features quite expressionless, his mild blue eyes apologetic.

"Yes, sir," he was saying to Devries. "I 'ave a message for Sir Basil, sir. Personal, it is, and if so be as I can see 'im—"

"You can't," snapped Devries, and then glanced at the empty wharf. The visitor had obviously come alone. Devries caught sight of Vecchini, and turned. "Oh, doctor, come here a minute."

Vecchini complied. Captain Devries extended a photograph to him.

"Here's a picture of that man Solomon," he said in a low voice. "No doubt about it, is there?"

Vecchini laughed softly and returned the picture. "None, captain, none."

Grimly, Captain Devries turned to the pudgy little man.

"All right, you're going to see Sir Basil," he said. "But you can't see him until he returns aboard. And until then you're going to stay put, my man. What's your business with him?"

"Well, sir, it ain't to be made public," said Solomon apologetically. Devries motioned to his seamen.

"Search him."

Vecchini, with a grin, turned away and hurried back to his job below.

Gaining the cabin, he found the door again locked. The guard opened it; he was taking no chances whatever. Vecchini went in, closed the door, picked up the syringe, and stepped to the bed where the prisoner lay with eyes closed.

Carson was wearing only shirt and trousers. Leaning forward, Vecchini opened one cuff and turned it back, laying bare the forearm. He took up a bit of skin between finger and thumb, and was on the point of inserting the needle, when something happened.

The bound wrists of the prisoner flew up. The handcuffs, which were of a heavy type, caught Vecchini under his bearded chin and chucked his head back—hard. He lost balance. Next instant Carson's hands had him around the throat, fingers sinking into the flesh.

The syringe flew through the air and smashed. Vecchini, half lying across the bed, thrashed furiously but vainly. No sound came from him. He tore at Carson's hands, but the grip of those steel fingers could not be loosened.

Gradually the efforts of the Italian lessened. His face was turning purple. His tongue protruded, his eyes were horrible to see; convulsive gasps of his choked lungs shook his whole body. Then his arms fell and he went limp. Carson relaxed his grip, made sure the man was not shamming, then let him fall beside the bed.

"Done it!"

With the exultant words, Carson came to his feet. Except for a bump on the head, he was quite himself. He looked down at Vecchini.

"A little more, and you'd have got what you deserved," he muttered. "But I'm no murderer. Trying to give me a shot, eh? Not this trip, thanks. Now, if I had something to take care of that guard—"

He glanced around. Handcuffed wrists are no great impediment to the use of the hands; a grunt of satisfaction broke from him as he perceived, above the washstand, a heavy glass water carafe in its rack. Carson reached it down, gripped it carefully in both hands, and went to the door.

This he kicked lightly, and stood waiting, the carafe poised.

As he had anticipated, the seaman outside threw open the door and entered the cabin.

The carafe crashed down with stunning force. The man pitched forward and lay motionless.

Guessing that this man held the key of his handcuffs, Carson knelt and searched swiftly for it. In his eagerness, he did not observe that the cabin door still stood ajar. Next instant he had found the key he desired. At the man's waist was belted an automatic pistol. Everything! Freedom, a weapon—he was not going to be taken unawares again! Once rid of these steel bracelets, he would turn the tables with a vengeance.

The key between his teeth, he was trying to work it in the lock of the handcuffs as he knelt, when a sudden tramp of feet startled him. He looked up, saw the open door, and tried to gain his feet—too late.

A sharp order. Devries himself, and two seamen, came bursting in the doorway as Carson tried desperately to get the door shut. Then they had him, holding him helpless; and Carson, sick with futile hope, looked into the passage and saw John Solomon standing there, arms held by two more seamen. Solomon! A prisoner!

Then the door was slammed, cutting off further sight of the passage. Devries, finding that Vecchini was not dead, turned in a cold fury to Carson.

"Handy devil with your hooks, aren't you? Well, this finishes you, my man. Assault and attempted murder, eh? This guarantees you a nice little stay in prison. Here, hold out your hands—we'll just make sure of you this time."

Carson's handcuffs were released, then snapped on again; this time with his hands about the brass bed-post. He said nothing; talk was useless. Solomon was a prisoner likewise.

Vecchini and the seaman were taken out. Carson, ironed to the bed, was left alone with despair for his sole companion.

IT was six thirty that evening when Sir Basil Lohancs returned to his yacht. This time he arrived in a large limousine which, with great care, drew up on the wharf beside the gangway, and remained there.

Captain Devries met the owner and made his report, curtly enough. A gleam of savage joy lit up the dark features of Sir Basil, and he clapped Devries heartily on the shoulder.

"Good, good; better than I had dared hope, Devries. What about the workmen?"

"They've cleared off long ago, sir. I tried to have night shifts put on, to get the work done sooner, but for some reason it was impossible. Five days we'll have to lie here, I'm afraid."

"No matter," said Sir Basil triumphantly. "It'll fit in all the better, as things are now. Where's Vecchini? Not too badly hurt, I trust?"

"He should be all right now. I've sent for him, sir. Do you want to see the two men?"

"Not yet; later. We'll get Vecchini off with my wife, first thing. Ah, here we are."

Vecchini appeared, pale and shaken; he had been a very sick man, and had not repeated his attempt to give Carson an injection. He could do it now, he said, if desired; but Sir Basil, rubbing his hands, merely laughed.

"No, no, let it go now. We'll turn over both men to the police as soon as you're out of the way with her. Come along."

With Vecchini, he went to the suite of the Duchess Alixe. There the woman Therese opened the door, smiling.

"She drank the tea, sir," said Therese calmly. "She's all ready to go, I think."

She was, indeed. Duchess Alixe looked up at them as they entered her cabin; her gaze was blank, stupid, she did not know them. She moved mechanically and obeyed orders listlessly, without protest.

"Pack at once, get off in five minutes," said Sir Basil. "The driver of the car has full instructions."

Under his eye, it was done. He himself escorted the duchess on deck and to the waiting car, treating her with a scrupulous politeness as though she were indeed his wife—as she was in fact. Vecchini and Therese got in with her, the luggage was disposed, and the driver saluted Sir Basil as he started the engine.

When the car had gone, Sir Basil turned to Devries.

"And now for the prisoners," he said. "Better fetch them into the saloon, and have them well guarded. Send a man to the night watchman's office on the wharf, and have him telephone for the police to take two men in charge. I'll lay criminal charges against them."

Five minutes later Carson was marched out of his cabin, handcuffed, and in the large, brilliantly lighted saloon found Solomon awaiting him, under guard. Sir Basil, with Devries and the bulky Frenchman, Du four, beside him, sat at a table. Beyond a brief nod, Solomon took no apparent notice of Carson, but fastened his placid blue gaze on Sir Basil.

The latter regarded his two prisoners affably, but in his dark eyes lurked a flame.

"You fools," he said with bland contempt, "I hope you've learned a lesson. Solomon, you and your man here are to be prosecuted for assault, attempted murder, and any other charges that I can file. That is precisely all you'll get out of pitting yourself against me."

"Yes, sir," responded Solomon mildly, even apologetically. "But if I might make so bold, Sir Basil, I've been workin' on me statement of accounts with you. And 'ere they are, sir, all shipshape and Bristol fashion. If you'd be so good as to cast your eye over it—"

He held out a little red notebook. At a gesture from Sir Basil, one of the guards took it and laid it on the table.

"Your accounts with me, indeed! A fine impertinence—"

Contemptuously, Sir Basil picked up the little book and ruffled through its pages. Some entry caught his eye; he frowned, looked more closely. His eye flashed. His dark features became livid with anger. He dashed the notebook to the floor and leaped to his feet.

"You insufferable ass!" he cried furiously. "How dare you—how dare you! My wife has left the yacht, do you understand?"

"Yes, sir," returned Solomon. "I thought as 'ow she would, sir, if you 'ad to lay up 'ere for several days."

Carson started slightly, looked at Solomon; something in that wheezy voice, in those words, drew his attention.