RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

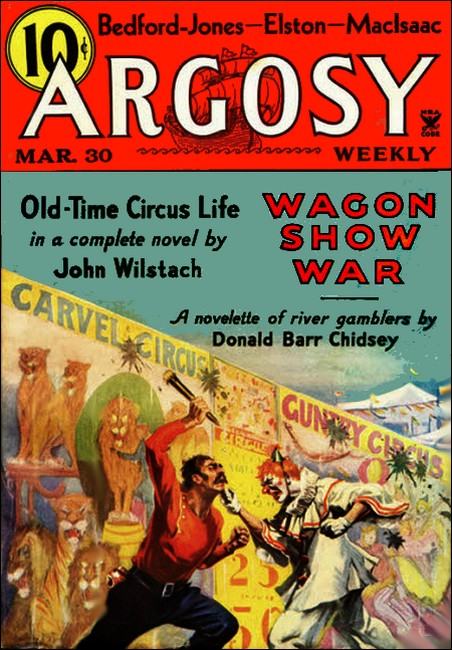

Argosy Weekly, 30 March 1935, with "Free-Lance Spy"

The Sphinx played the greatest game in the world, a game for life

and death—his own included—against the shrewdest spies of Europe.

IN the darkness of a room overlooking the courtyard of the old Hôtel des Anglais, in Nice, a slight sound broke the early morning silence. A warning bell, so thin and silvery that it might have been imagination. Day after day, night after night, Marie Nicolas had been awaiting this sound.

She swiftly flung back the covers, threw herself out of bed, and over her nightgown drew a padded bathrobe. In her hand glowed a tiny flashlight. The faintly reflected radiance showed a glimpse of her dark and lovely features, her wide, hurried eyes ablaze with excitement. Then darkness closed down again.

A large Bible was on her dresser. She snapped it open; the book, made solid with glue and cut out in the center, was a box. From this she took a set of head-phones. The tiny finger of light touched a mark on the wall paper. She inserted a plug, pushing it into the paper; the round points, so different from those of American plugs, shoved neatly home. In her ears leaped a voice.

"They are fools, these Americans. Smart Yankees! I'll show you the truth, Truxon. I've taken care of them, all of them. I know everything about them."

Excitement set her pulses hammering. She could visualize the scene in that room, only two doors away from hers. The speaker was Rothstern; fat, jovial, with gold teeth and a shining bald spot. One of the cleverest secret agents of all Central Europe. Who employed Rothstern? No one knew, positively.

He was identified with Germany, but he might be working for the Nazi party, for Hitler personally, for Poland, now the close ally of Germany, or for any other cause.

Truxon? Yes, she knew this lean, dark, savage man, this renegade Englishman who had been kicked out of the British diplomatic ranks. It was Truxon's room yonder, his and Stacey's. Another of the same sort was Stacey, but weak and vicious, diabolically crafty.

Now she crouched closer, listening intently. The dictaphone worked perfectly. She had been two weeks getting it in place, since learning that Truxon always occupied this same room when in the city.

"They're not fools," cracked out Truxon's hard, smashing voice. "They're smart. The smartest of them is that fellow Barnes."

Marie Nicolas thrilled to the name, to the grudging admiration of this enemy.

"Barnes will be dead within the week," and Rothstern laughed softly. "Let me explain two things to you; this American activity, and the general situation."

"Damn the situation," growled Truxon. "I work for whomever pays me."

"I pay you." Rothstern spoke with abrupt authority. "Listen. Certain Americans like Barnes are working for their government. Idealistic fools, who place themselves and their brains and money at the service of their country; they have no standing, they have no acknowledged connection with Washington.

"They are free-lances who prate of bringing a new deal into diplomacy, of fighting us here in Europe with our own weapons."

The scorn in his voice was acid.

"Barnes is one. He pretends to be a fool, but is smart enough; however, he is in my hand. There's Hutton in Vienna, Morlake in Berlin, McGibbons in Warsaw, Pratt in Moscow, Williams in London, Reilly in Paris; also, there are half a dozen less important ones who have no steady position. Every one of these men is under the most strict watch. So is this girl, Marie Nicolas."

"What?" ejaculated Truxon. "But she's working for Italy!"

Rothstern laughed, and at his jovial laugh, Marie Nicolas trembled.

"So you think; so others think. She is really one of these American amateurs, my friends. She is here, in this same hotel; she has been here for two weeks, ill with influenza, or so she pretends. She leaves her room only twice a day, to sit in the sun in the courtyard. Well, she is attended to. Now, here's your pay for the next month."

A rustle of paper as banknotes were counted out.

"You don't care to go into the general situation?" Rothstern asked, with a note of mockery.

"No!" shot out Truxon. "Perhaps we know it as well as you do. We're only interested in earning our money."

"You shall earn it, I assure you. I have met this Barnes and know him well; he is open to bribery if rightly handled. But he's not the fool he looks, as you've found to your cost. On next Friday he will be in Ostend; you'll be there ahead of him, and so shall I. My work is to trap him; yours is to kill him. Understood?"

"Gladly," and Truxon's voice held a savage note of hatred. "But how?"

"How? Once and for all," and Rothstern's voice shook with laughter at his own jest. Then he sobered. "Now listen carefully. Next Friday evening, Ostend is to witness a gala performance of Beethoven's Solemn Mass, with chorus and artists from Paris. The king will attend. From Paris come a number of diplomats to attend, among them the American ambassador, and also Grimaldi, the Italian ambassador.

"Barnes is going to meet the American ambassador and obtain the signed draft of the tentative Abyssinian treaty."

"Abyssinian treaty!" echoed Truxon. "Are you insane? The States make a treaty with Abyssinia? That's nonsense."

ROTHSTERN'S jovial laugh boomed out. "Ah, you know so much, you care so little for information! Well, never mind. There is much more to the business than appears on the surface. The main thing is that this man Barnes must be killed."

"Leave it to me," said Truxon.

"I can't leave it entirely to you. I must obtain the treaty draft from him."

"Sounds like nonsense," growled the renegade. "Why doesn't the American ambassador put it on the cables?"

"He has done so. We do not desire to keep it from Washington; merely to know its terms; so we prefer to intercept the original draft which Barnes is to take to London for inclusion in the diplomatic pouch to Washington. You see, these people have learned that we have a friend planted in the Paris embassy. They have become cautious."

"Looks to me, Rothstern," Truxon stated coolly, "as though you're lying about the whole thing; or you're covering up the real truth. Well, no matter. It's none of our concern."

"You are right, it is not," said Rothstern with a touch of asperity. "Barnes is the most dangerous of these American fools. He must be removed for good and all—ah! Someone at the door."

Silence; incoherent sounds, a mutter of voices. The crouched girl strained against the dresser in the darkness, shivering, but not with cold. Fear was in her heart, and not for herself alone! Then the voice of Rothstern exploded violently.

"A message for me! Give it here. Ah, a telegram, eh! It is—it is—ten thousand devils!" His voice broke in a passionate oath. "Greetings to our pleasant conference; signed merely "The Sphinx, U.S.A.' Is this a joke? Damn you, answer me!"

The Sphinx! A thrill ran through the crouching girl. Then she started violently and turned. Outside her door was a step. It paused there.

She moved like a flash. Snatching off the head-phones, she silently slapped them and the cord into their false Bible, and next instant was beside the bed. She poised there, holding her breath.

A low, soft rustle came from the door, then ceased. The step sounded again, moving away.

AFTER a moment she threw the pencil-beam of her tiny flashlight on the door, then to the floor below it. A folded paper lay there; apparently a bluish French telegraph form. She went to it, picked it up, and opened it. It was no telegram, but on the form was typed in English:

THE FRENCH POLICE ARE ARRESTING YOU TOMORROW. CATCH THE PARIS EXPRESS AT 5 A.M. LEAVE TRAIN AT LYON, HIRE A BLUE RENAULT WHICH WILL BE WAITING ON EAST SIDE OF PLATFORM WITH A "FOR HIRE" SIGN ON THE RADIATOR. IT WILL TAKE YOU TO BRUSSELS.

The only signature at the bottom of this message was the red figure of a Sphinx, stamped there with a rubber stamp. Beneath the figure were the letters, "U.S.A."

The Sphinx! She, and she alone, knew whom that could be—whom it must be!

Suddenly she turned, darted to the dresser, seized her head-phones again, and listened. She caught Rothstern's voice. "I tell you, the French police are working with me! In this affair, France is with us—but not openly. Yes, come along to my room. I'll get the things you need, and there'll be no trouble at the frontier."

A door slammed. Silence. The girl swiftly put away her phones again. She flashed the tiny light on her wristwatch. Four A.M. It would still be dark at five. If she were to catch that express for Paris—

The French police working with Rothstern? What .was it all about? She had no idea. But she had been ordered to wait here for some message from Barnes. On her own responsibility she had arranged this dictaphone, this communication with Truxon's room. This hotel was well known to her. For the past two years she had been on the go all over Europe. And now something had happened, something big was coming up. War? No telling. All Europe was a hotbed of intrigue, of rivalry; France and Italy stood out against each other.

The Sphinx! Her brain rocked with indecision. She remembered that day when she had called Barnes a Sphinx, and how his face had lighted up. Now he had sent an ironic message to Rothstern, another message to her. Barnes! Yes, it must be Barnes, it could be no one else. Why was he adopting this nom-de-guerre? Why were the police about to arrest her? They had nothing against her. Yet she could not doubt. Rothstern knew everything about this little band of gallant Americans who were pitting themselves against the secret agents of Europe. They would have no recourse if they failed. They had no connection with Washington.

A thousand questions rioted in her brain; she sat with eyes closed, trying to evoke some order out of the mental chaos. Gradually it came. She must reach Barnes with what she had heard, yes! She had something definite now. Rothstern knew everything. Not one of the unofficial American agents, these free-lances who risked everything for their country, was safe. Rothstern knew of them all. He boasted that he had her in his hand. Yes, it was he who intended to have her arrested. How did Barnes know of it? Again the questions rioted. Again she beat them down, crushed them back. Nothing mattered now except to follow the orders of the Sphinx. Barnes? Ah—

She broke off abruptly, rose, switched on the lights in her room, after closing the window and drawing the blinds. She looked around. If there were danger from the police, she could not take away her belongings. She must abandon everything, her luggage, her clothes, and take only what she could carry in her handbag. No one must see her leave; well, that could be managed!

The holes in the wall paper she carefully patched; this room might again come in handy. The head-phones she must throw away in the street. Clothes, personal effects—she swiftly made her choice among them. Queer, that Barnes should know what the French police intended! It was two months since she had seen him; in this interval he had completely dropped from sight.

Now she was clear-headed, cool, alert. She left money for her hotel bill, with a note asking to have her effects held; she had gone to Menton for a few days. This might throw the police off the track. If only she did not have to buy a ticket and a place in the train! There was the danger-point, if the police were on the lookout. Room lights off, she slipped out into the deserted corridor.

IN the street, the chill wind of coming dawn, the sparse lights, the emptiness and absence of life, appalled her. She came into the Boulevard Gambetta; a long way still to the station. A glance at her wrist-watch and she stepped out more briskly. Only twenty minutes left now.

With a hoot-hoot and a flicker of yellow, lights, a taxicab rattled along behind, overtook her, and passed on. She paused, shivering. From the open cab window, floated a laughing voice; the hearty, jovial tones of Fat Rothstern, accompanied by the harsh, inhuman laugh of Truxon. She faltered. On their way to that same train? No help for it. She feared Rothstern more than the renegade Englishman, because his merry deviltry was abnormal. The same train? Well, she must go on. She had her orders.

Resolute, she hastened on with something very like a suppressed oath at her own heart-hurried fears. After all, she could take care of herself. She was the equal of any man of them, as she had proved ere this. What folly, to let the chill morning darkness oppress her! A laugh, and she flung off the weight. The thrill of it all seized upon her. Her pulses leaped to the fervor, the quick chances of the game.

She took the short-cut out of the Place Franklin. Two bicycle police rolled along, eyed her sharply, went their way. Ahead opened the width of the Avenue Thiers and the railroad, the glittering lights of the station beyond. The train was there; the engine was huff-huffing like all French engines. No time to lose if she were to make the express!

Suddenly a man appeared ahead, a dark, thin man, a stranger. He was aiming to intercept her. Hand flew to bag; her little pistol was jerked out. She went straight at him. Then, to her astonishment, she heard her own name.

"Mademoiselle Nicolas, is it not? Correct. Your billet—everything. Hurry!"

She took the envelope thrust at her. The man turned away and was gone, slouching off into the shadows. Hurriedly, she examined the envelope. Yes; a seat to Paris, a ticket to Paris. Also a ticket to Lyon. She understood in a flash. She must show the Paris ticket in case she were traced. At Lyon, where she would leave, she must give up her ticket before getting out of the station. No Frenchwoman would give up a Paris ticket before getting halfway there; hence, the Lyon ticket to avoid comment.

Who had done this? She caught her breath, as she turned over the envelope in her hand. Upon it was the rubber-stamp of the Sphinx. Barnes? No, no, that was impossible. Barnes knew his way around Europe, but he was an innocent, a new hand at this game. She must be on some false scent after all.

The whistles of the guards were shrilling when she came on to the platform. She had one glimpse of Truxon standing there, tall, lean, savage, waving his hand. Rothstern was on this same train, then!

DAYLIGHT crept down from the Alps, with Toulon still well ahead. It would be afternoon before they reached Lyon. Sunlight filled the morning. Marie Nicolas wakened from her nap, stretched, found her handbag and little toilet case at her side, and her brain leaped alert instantly. She forced herself to forget all the mystery of the night, even the dark stranger who had supplied her with tickets. She now had to face the danger of the day, with Rothstern on the same train.

Fortunately, she was no longer an apprentice at this business. She had brought with her all she needed.

She went into the dressing room between the compartments, glanced into the next compartment and found it empty, and went to work rapidly. She grimaced into the mirror at her neat, trim face and figure, her warm cape and the Rue Vignon dress. She was indeed very lovely, the essence of good taste; well, this must be altered!

Her masses of dark hair were rearranged in careless, sloppy fashion. Cheap, musky perfume was liberally splashed about her dress. She deliberately ripped her chic little hat and sewed it together again, a flimsy ruin; the lines of her dress, her figure, could not be spoiled, but the set of the dress could be spoiled with a reckless tug here, a pull there. When she looked in the mirror again, it was with a sigh.

Now for her face. Gaudy, splashy earrings were nipped in place, dangling almost to her shoulders. Deft touches darkened her brows, changed their contours. Darker skin about her eyes, the lids darkened; a hideous, flashy lipstick completely out of harmony with her complexion changed and spoiled her mouth. Last of all, glasses; pince-nez that really pinched. Another grimace when she inspected the result.

"A woman in the worst possible taste—can it be you?" she observed cheerfully. "Yes, it really is little Marie; but who would know it? Especially a man. And the hair, the hair! That's the best of all. Marie Nicolas, you're a perfectly horrid person—and hungry!"

All this had taken time. The dining-car messenger appeared, reserved her a place, and went on. She left her cape behind, bunched her dress still more shapelessly, and ventured forth.

She was early; she wanted to be early. The train was wakening as it thundered along. Tourists of all kinds, many French, but few Americans; the rate of exchange kept Americans out of France, these days. Fortunately, the restaurant car was close at hand, and with relief she entered and found herself placed at table. The waiter addressed her significantly in English; she, who was invariably taken for Russian or French, was now an obvious tripper! She smiled brightly.

Then, for an instant, she shrank, and her pulse stopped. A presence behind her, a jovial, hearty voice—Rothstern. Coming in with another man.

"Yes, garçon, yes, a good breakfast," she exclaimed in an abominably harsh voice. Her English accent made the waiter wince. "Muffins and everything. And don't forget the marmalade, my man. Right!"

To her horror, Rothstern paused at the next table. Then he turned his back; he sat down with his back to her. She could see the shiny bald spot, the clipped hair, the roll of fat above his collar—but thank heavens, he could not look at her! For an instant she closed her eyes, then opened them.

They dilated. Incredulity came into her face and passed. For there, sitting opposite Rothstern and chatting gaily with him, was Franklin. Young Franklin, the laughing Baltimore boy who was the latest recruit to the free-lances; he was supposed to be in Rome, getting on to the ropes. And Rothstern had him in tow!

She watched them. Once or twice Franklin's gaze rested upon her and flicked away again. He looked tired, a bit drawn, but evidently he was charmed with Rothstern. Most men were, who did not know him well. Marie could hear Franklin's voice at times.

"Yes, a bit of business in Paris. Importing is pretty well wrecked these days… sight-seeing in Italy. Wonderful place under the Fascist régime! No, I didn't hear any talk of war… in the wine business, eh? You speak perfect English, really!"

From what snatches of talk she caught, the girl gathered that they occupied the same compartment. Was this by chance? She doubted it. Was it by chance that she was on this train with Franklin? The question startled her with its implications. How far ahead did this unknown Sphinx see and plan? Questions be hanged! She dared not let them engulf her, and resolutely put them aside.

Somehow she must warn the young fellow. That he did not recognize her was quite evident. It was unfair to pit him against the veteran Rothstern, who had already enmeshed the boy. As she lingered over her breakfast, more questions rushed upon her; what was going on, what game was being played out with its final scene reaching up to Ostend in Belgium? She could not guess. She struggled to keep her mind on the business in hand, on her own perilous strait.

Toulon was behind them; the train was creeping on westward to Marseilles, before it turned north to Avignon and Lyon. Suddenly the bulk of Rothstern heaved up. His voice came to her clearly.

"You will pardon me? I must prepare telegrams to go from Marseilles. We may meet again on the platform, eh?"

Telegrams, eh? The fat fox was up to something; yes, the boy must be warned. Rothstern brushed past the table of Marie Nicolas without a glance and went his way. Quickly, the girl seized pencil and a scrap of paper.

I am Marie Nicolas. Destroy this. The man with you is Rothstern. He knows every one of us. If you bear any messages look out. Keep away from me.

Presently Franklin rose, paid his bill, and started past Marie's table. Her handbag was knocked from the edge as he passed, though not by his doing. He halted, and with a word of apology stooped for it. As he rose and handed it to her, she slipped the note in his hand. He gave no sign of astonishment, but went on and was gone.

She breathed more easily. After a moment she, also, paid for her breakfast and departed. On the way back to her compartment she kept a sharp eye out, but saw nothing of either man; therefore, they must be beyond her car, toward the rear of the train.

THEY were flashing into Marseilles now. As by magic, the station appeared and the express slid to a smooth halt. Ten minutes here. Marie opened the door and stepped out to the platform. The news-wagon was almost opposite. She bought Paris editions of English papers, a couple of English magazines, and ducked back into her own compartment again. She had not seen a paper, except the French journals, for two weeks.

Minutes passed. Suddenly Franklin appeared, opening the compartment door that led into the passage. He came suddenly, his voice leaped at her.

"They've got me. Do your best—"

Something flashed in the air and fell at her feet. An envelope. She kicked it under the seat. Franklin was gone; at the same instant, the outer door was wrenched open and two Frenchmen entered, typical business men. Politely, with many apologies, they asked if they might share the apartment. She affected ignorance of French. One explained himself in halting English. Marie Nicolas shrugged, nodded, and opened up her newspapers. The two Frenchmen settled down, deep in talk.

Men moved rapidly past the passage door. After a moment, glancing out at the platform, she saw Franklin there with several suave gentlemen; he was being arrested, then. The engine whistled, the guards slammed the doors, the train moved out of the station. Arrested! Then Rothstern had done it. And her warning had come barely in time. That fat devil was checkmated for once, thank heaven!

The guard appeared, verified the first-class tickets of the two Frenchmen, and went on. Suddenly their words reached into her consciousness.

"Did you see the statement of Count de Prorok, the explorer? He has just left Abyssinia. He says the Italians have massed troops in their colony of Eritrea and are preparing to seize Abyssinia, that France and England have consented, that Italy has caused the frontier fighting. It means war!"

"Bah!" was the response. "No one knows or cares anything about Abyssinia. It is the Balkans that should worry us!"

"No worry," said the first. Marie abruptly realized that she was listening to a keen analyst who knew whereof he spoke. "England, France, Germany, want no war. Russia allied with the French, wants no war. Mussolini will keep the peace, depend on it! He'll permit no Balkan conflict. All this is a mask; he intends to seize Abyssinia. Forty years ago, an entire Italian army was destroyed there, at Adowa, and Il Duce means to avenge the loss and seize the whole country. Just as Prorok says. Another Manchuria, my friend!"

"Well, you should know." And the other laughed. "You have a nose in the Quai d'Orsay. But what is it to us, to France? Let Italy rule the black savages. Her rule will be good for them."

"Shall we step out into the passage and smoke?" was the reply. "This Englishwoman will be sure to object if we smoke here—"

The two left the compartment. Marie Nicolas leaned over, picked up the fallen envelope, and glanced at it. Sealed, and addressed only to John Barnes. She thrust it away beneath her dress and pinned it there securely.

She returned to her papers. There, she found the key to the conversation she had just heard; conflict on the borders of Abyssinia and Eritrea, an appeal to the League of Nations by the former, a refusal of any arbitration by Mussolini. So Il Duce would keep the peace in Europe in order to have a free hand in Abyssinia? Very likely. She shrugged and dismissed the matter as of no interest.

SUDDENLY, with a leap of the pulse, she remembered what Rothstern had told his two mercenaries. A commercial treaty with Abyssinia? It was nonsense, on the face of it. The United States had no commerce, no interests, there. Then why was Rothstern so desperately set on learning the terms of this alleged treaty?

"More questions," she muttered angrily. "Plague take them all!"

Back to the newspapers. A short, sharp exclamation broke from her; she stared at the news items with distended eyes. Morlake in Berlin, Hutton in Vienna, had been arrested the previous evening. American business men, charged with espionage. And both were members of the free-lances! Rothstern again, striking savagely. Why?

The two Frenchmen came back into the compartment, apologized politely, and went back to their rapid French conversation in supreme confidence that their fellow-traveler could not follow. The one who had his "nose in the Quai d'Orsay" explained a detail to his companion.

"I tell you, a month ago ships went out of Marseilles loaded with munitions for Abyssinia! There is only one railroad into that country; we control it. Are we letting arms reach the Ethiopian emperor? Then why this disregard of treaties? It looks singular. Watch. You will see things happen in that country."

A fat shape bulked against the glass of the passage door, looking in. Rothstern. Then he went on. A sense of suffocation oppressed Marie Nicolas. The Frenchmen had switched to a discussion of business conditions. She listened no longer.

The express rolled on to the north. The Sphinx, the Sphinx! Incredible as it seemed, this might be Barnes. At least, he had given Rothstern and the two renegades a startling surprise with his telegram. He seemed to be aware of their secrets; no, he could not be Barnes, after all. A glow crept into the girl's eyes as she thought of him. A splendid fellow, Barnes, but new at this business. No, he could not be this mysterious Sphinx.

Avignon fell behind; a brief stop only. Crossing the river, she had a glimpse of the storied castle of the Popes, with its towering height and the broken bridge below. No stop now until Lyon.

The chief of the train, the "conductor" in America, made his appearance, heavy with gold braid and authority, as befitted a trusted employee of the government. He beckoned the two Frenchmen outside and there, in the passage, conferred with them; many shrugs, gestures, explosive sounds. Finally they appeared to agree. A guard arrived and came in, taking their luggage out. They all vanished up the corridor.

Another guard came in sight, carrying two suitcases, an umbrella, a portable typewriter. He lugged them in, disposed of them in the racks. The girl spoke quickly.

"Is someone else coming in here?"

"But yes, ma'mselle," he responded, touching his cap. "A rearrangement, you comprehend; many passengers came on at Avignon. A gentleman from the second class is moving in here. It will not inconvenience you."

She could not reply. The words died in her throat. For there at the door was the gentleman from the second class. It was Rothstern.

He entered, tipped the guard, and lowered himself upon the opposite seat. He did not glance at the girl. His heavy, jovial features were intent upon a number of telegrams which he must have received at Avignon. At length he stuffed them into his pocket, picked up a newspaper, and began to peruse it.

Marie Nicolas sat reading. She felt stifled; her thoughts were inchoate; terror was upon her. She, who was supposed to be so fearless, so well able to take care of herself, stood in absolute fear of this man. She could face the brutality of Truxon, but the gold-toothed smile of Rothstern unnerved her.

She became aware of furtive glances stealing at her. What to do? She could not leave without making a scene, if he were really suspicious of her. If not, her best bet was to keep quiet. Suddenly he chuckled slightly and laid aside his paper.

"Madame is, no doubt, a tourist?" he said in English. The girl gave him a cold look through her glasses, and returned to her magazine.

"The eye is a wonderful organ," he went on, with another chuckle. "When it follows lines of type, it moves back and forth, one sees it at work. But the eyes of madame are fastened upon one point, they do not move—"

"Sir, are you determined to be insulting?" demanded the girl icily.

"A thousand pardons!" said Rothstern humbly, and spread out his hands. "I merely pass the time with observations. I am a philosopher."

He paused to light a cigarette. Marie Nicolas felt a cold, chill thrill pass up her spine. She knew what was coming; and she was right.

"Elimination," murmured Rothstern, as though to himself, "can solve many things. A young lady disappeared from her hotel at Nice. I learn of it later on. I determine that she must be on a certain train. I search, I see nothing of her. I speak with my friend the conductor. Yes, a young lady bound for Paris did come aboard. She is not the one I seek, obviously; yet I think she must be the same. One thing she cannot change, and that is the little foot. The shoe made in America is so obvious in France! So is the shoe made in England—but she does not wear the English shoe."

MARIE NICOLAS shrank for a moment, conscious that the blood had drained from her face. Then she quietly laid down her magazine and looked at Rothstern. He met her gaze, a twinkle in his eye, his jovial laugh showing his gold teeth.

"So?" he asked. "You would not tell a lie to old Papa Rothstern, hein?"

She knew the grim, ruthless cruelty behind that laugh. "Not much use trying to fool you, is it?" she said quietly.

"Not a bit. Ah, now you are sensible!" Rothstern beamed upon her. "Why did you run away from the hotel at Nice, my dear?"

"To see where you went, if you must know."

Rothstern chuckled. "Good. We are in company; we go to Paris together. Now, my dear Marie, shall we be frank and abandon all fencing? Good. Perhaps you caught this train to meet Mr. Franklin, hein? And somehow, somewhere, he gave you what I want very much to have. Perhaps you warned him, even, about poor old Papa Rothstern."

The girl shrugged. "Yes, I did. But I didn't know he was on the train until I saw both of you together. After that, I had no chance to speak with him again."

"Evasion, eh?" Rothstern rubbed his pudgy hands—big hands, massive hands they were. The gesture chilled her. "Very good. No doubt you have read the paper there. No doubt you saw what happened to poor Franklin; an estimable young man whom I had no chance to warn. Very well. Now, suppose we are friends, eh? Suppose you tell me something I want to know. We lunch together, we reach Paris friends, and part. I will protect you against anything unpleasant, such as happened to poor Franklin. You will not do badly to have Papa Rothstern for a friend, Miss Nicolas. Yes or no?"

"What do you want to know?" she demanded. The threat was clear enough. She would be arrested if she refused. Probably she would be arrested anyway, later.

"Just who is the gentleman who calls himself The Sphinx, U.S.A.?"

She started, her eyes widened. "But I can't tell you that! I must not tell—at any price!"

Rothstern beamed. "The price? It is simple. You remain free, my dear, as you should remain. Come; I see you know. Tell Papa Rothstern."

Beneath his joviality the threat began to appear more pronounced.

"If I tell you—but no, no, I cannot!" she exclaimed in agitation. "No one—"

Rothstern's ponderous features came closer, as she shrank. He seemed fully aware of the terrifying effect he exerted upon her.

"The French police can be most unkind to a poor prisoner," he suggested. "It would pay you, really, to make a friend of me. And nobody would know, upon my honor!"

"I—could—I trust you?" she breathed, staring wide-eyed. "But wait! I must send a telegram from Lyon.

"We shall lunch together, then. If when we leave Lyon I feel that you won't betray me—I'll tell you."

Rothstern beamed, and nodded. "Good! We shall have a nice luncheon with champagne, my dear. Ah, if I were twenty years younger! But we shall see. Yes, you'll find that it pays to trust Papa Rothstern."

She shivered a little, thinking of the envelope pinned within her dress.

JOHN BARNES stood on the station platform at Lyon and waited for the P.L.M. northbound express.

Over one ear was cocked a disreputable chauffeur's cap. Over the other ear, in the approved chauffeur's custom, was tucked a spare cigarette. A dirty white chauffeur's dust-coat, the French survival of a prehistoric motoring age, cloaked most of his body. He had a sandwich in one hand, a bottle of vin blanc in the other, and excitement blazing in both eyes.

A thin, dark man drifted up to the lunch-counter, bought a sandwich, and began to eat it. He drifted away, paused for an instant beside Barnes to inspect his sandwich suspiciously, and spoke under his breath.

"M. Franklin was taken off the train at Avignon by agents of the Sûreté. I just got the wire."

"Cover the exit gate," muttered Barnes, and the dark man drifted on.

You must see Barnes as he stood there, munching ravenously, drinking from the bottle, dirty hands, face ingrained with dirt and beard-rubble. An impudent chauffeur type, a humorous glitter in his excited eyes, a strong, hard jaw, lean in the sunlight as he tipped his head back to drink. And those stabbing, dancing gray eyes of his covered everything in sight. A man playing the greatest game in the world, and playing it for life or death. His own included.

Let us suppose, to get the picture, that a Frenchman stands before the lunch-counter of the Pennsylvania station in Philadelphia. The Federal secret service is after him. The local police are watching for him. The railroad detectives have his description. And he stands there, eating, drinking, laughing, ready to pull off the biggest coup of his career! That was the situation of John Barnes as he waited.

The sandwich gone, he finished the bottle, handed it back over the counter, took the cigarette from behind his ear, and struck a match. At the other side of the platform a south-bound train had pulled up, and people were drifting everywhere. A French station platform is like a jail. To get in and out, one buys a ticket; to leave it from a train, one gives up the railroad ticket. Barnes took the ticket he had bought and held it ready in his hand. The north-bound express was coming in. He made his way toward the nearest exit, glanced at the guard there, then turned to watch.

There was the express now. News-wagons trundled out, wine and sandwich wagons; police strutted about importantly; porters rushed about, their straps aswing. Barnes puffed at his cigarette, motionless. The express came to its swift and silent stop. Bells clanged, whistles blew. Passengers began their frantic concourse, shrieking at porters. The carriages were emptied, everyone strolling up and down.

A girl appeared. Barnes threw away his cigarette, pulled down his cap over one eye, stood tensed. Marie Nicolas, holding a telegraph blank in her hand, hurrying. Behind her loomed up the fat figure of Rothstern, overtaking her with a jovial laugh. She swung around Rothstern took her by the arm.

Like a flash, she slapped him across the face, hard. Her voice shrilled up in a torrent of rapid French: "Dirty pig! You would insult a woman of France—oh, to me, to me, messieurs! This sale cochon of a German would insult me—"

Instantly, the platform was in an uproar. From all sides, Frenchmen came on the jump. Rothstern, incapable of a word, was surrounded and drowned in a rushing hostile mass of figures.

Barnes turned to the exit, gave up his ticket, and strode swiftly out to the street. There, where a blue Renault stood with a "For Rent" sign on the radiator, was a dark, sad man. Barnes made him one quick gesture, and got into the car. The other turned and departed at a run and was gone around the next corner.

Out from the exit slipped the figure of Marie Nicolas. One swift look, and she came toward the car. Barnes swung open the door. Without hesitation, she ducked in and slammed the door behind her as she half fell on the rear cushions, the car already in motion.

With a swoop and a roar, the Renault went leaping away.

"M'sieu," came the girl's voice from behind, breathless, excited. "Are you sure that it is all right? You expected me?"

"Hold your breath, baby," said Barnes in English, and chuckled. "Change cars at the next transfer stop. This is fast work; no time to talk."

A startled gasp from behind, and he chuckled again. Then he settled down to business.

He drove fast and hard for five minutes, dodging traffic and rounding corners like a madman. Then he slowed. A garage appeared ahead, before it a large gray roadster, and beside the roadster, the same thin, sad, man who had departed so hurriedly from the station. Barnes came to a halt behind the roadster, which bore an English license.

"All out, Marie!" he exclaimed, and ducked from the front seat. With a swift movement he was out of his cap and white robe. "Ready, Eremian?"

"Quite, monsieur." The thin, sad man handed him a little packet. "Passports, touring permit, everything. Here is the driver's license in your new name."

"Good. In with you, Marie."

HE settled under the wheel of the roadster, Marie Nicolas beside him The car leaped away. Ten minutes later, they had passed the city tax-barrier without question. Then Barnes drew a long breath, and glanced at Marie, his gray eyes dancing merrily.

"Made it! By glory, that was a tight squeeze, young lady. Did you see Franklin?"

"Yes. He gave me a letter for you."

"Thank heaven! Keep it for the present. How are you?"

She gestured helplessly. "Bewildered. Utterly bewildered. John Barnes, you're not the same man I knew!"

A joyous, eager laugh escaped Barnes. "You bet I'm not! But I've got you safe away out of the smash."

"It looks crazy to me," she said. "I could have got across the border from Nice without heading north over the whole of France."

"Not a chance," Barnes said decisively. "Every road, every border station, on the south and east, was stopped this morning. This trip, we've got the whole of France against us. Germany as well. What I predicted to our ambassador in London, months ago, has happened. Every one of our men has either been clapped into jail or is under the closest sort of scrutiny; they've smashed our organization, Marie."

"And Rothstern did it. He said so," she cut in swiftly. Then she caught the arm of Barnes. "Tell me! Are you the Sphinx? Are you?"

Barnes gave her a quick, hard glance, then watched the road again.

"Yes. I thought you'd guess it. I heard of Rothstern's coup just one jump too late. He's tried to clear the slate at one crack, and he's darned near done it, too. Half Europe is behind him—just for this one occasion. Two weeks from now, the storm will be over; but right now we're sure in the soup all around."

"But why?" she demanded. "What is it about? Is there really an Abyssinia treaty?"

"Good Lord!" Barnes flung her a look of startled wonder. "How the devil did you catch on to that? You certainly are a marvel! Go on, talk. That was a lovely getaway you made on the platform. Tell me about it. About everything."

"For one thing, they plan to get you when you go to that musical thing at Ostend, to meet the ambassador from Paris. Truxon has that job."

Barnes started, then whistled softly. "Damn it! They have a spy in the Paris embassy; we can't locate him. All right, tell me how you know so much."

Laughing, she complied, delighted at having puzzled him, and still lost in wonder at finding him to be the Sphinx in sober earnest. And as she talked, Barnes kept the roadster roaring to the northward at high speed.

What a girl she was! Her vibrant personality, her keen ability, fascinated him. She was the one person he had determined to save at all costs, from this sudden debacle which had burst upon the little company of free-lances. She was worth all the rest; not because she was a woman, or from any personal interest, but because her wits, her brain, was worth the others combined.

"There you have everything," she concluded. "Is it really something about Abyssinia? What we could have to do with that country, I've no idea."

Barnes nodded frowningly. "We have. Their envoy in Paris has arranged terms with our ambassador there; tentative terms, to be confirmed in Washington. The mutually signed draft is the crux of this situation. It must go by special messenger, and getting it out of Europe is the very devil. Why, I'm not sure. Why Rothstern must have the terms, I don't know. Abyssinia no doubt hopes that a special treaty throwing her borders open to our commerce will forestall Italy, for Mussolini is intent upon grabbing the country. Reilly is to meet us at Dijon, if he gets out of Paris safely.

"He'll know the answer, and why France is so suddenly backing Rothstern's hand."

"But, tell me about yourself, about the Sphinx!" exclaimed the girl eagerly. "How did you send those messages to Nice? How did you have those tickets awaiting me as by magic? Who was the dark, sad man in Lyon?"

"I ALMOST hate to tell you," said Barnes slowly. "And yet, Marie, you're the one person whom I can trust, and who must know the truth. For weeks, I've been sitting in front of a café doing nothing, while Rothstern's agents watched me. In that time, I've built up an organization to take the place of our own. I saw the smash coming. Good as we are, we're nothing against these double-crossing rats who call themselves secret agents."

"Apparently you've done the impossible," she said dryly.

"I have. Everybody has overlooked a great bet. For fifteen years, France has been the haven of Armenians—not the low-class peddlers we know at home, but people of the highest class. That man in Lyon is a graduate of the Sorbonne, Oxford, and Geneva. His father was an intimate friend of the sultan before the war. The man who gave you the tickets in Nice, was once a prince. These refugees have no country, no cause, no hope. I have given them all these things.

"One of them alone might betray me; banded together, they would never betray one another. They have a cohesion of blood, of race; America helped the Armenians, and they remember this. I am cashing in on byproducts of past history."

She drew a quick breath; her eyes dilated as she watched his keen, alert profile.

"You? Who else?"

"No one else—except you. I figure on keeping the wrecks of our organization and using them, chiefly as a mask. Rothstern and the like will never look beyond to seek a second-degree organization."

"Then you—single-handed—you are doing this—"

Barnes smiled thinly. "The Sphinx, my dear; the Sphinx, U.S.A.!"

"Who supplies the money?"

"I furnish some of it. Other Americans have contributed. I have friends who trust me, remember, and who ask no questions."

"Either you are an absolute madman—or a genius!"

The gray eyes twinkled at her. "Which do you say?"

"Both. Oh, it's wonderful, it's splendid!" she broke out passionately. "If only you can depend on these people—"

"I can. They have relatives, friends, all over France. They are like the Jews, a race absolutely banded together in ruin; they have an infinite genius for detail. I give one of my key men certain instructions; he arranges everything. I can hand one a message today in Paris, and it will be delivered in the most spy-proof manner that same night in Vienna, Naples, Marseilles, Petrograd—and at the same identical moment. You see, the possibilities are vast, almost unlimited."

A sobering thought. "And you see why I've picked on you?" Barnes glanced at her, laughing. "Any other woman would have been mourning her clothes, her personal possessions, everything she'd lost. You don't. You're always a good campaigner."

"Oh, we can always buy more!" she exclaimed brightly. "But don't you want that letter?"

Barnes shook his head. "Wait until we reach Dijon. It'll be in code; it was given Franklin for delivery to me, by an Armenian in Rome."

"So you're using codes, which can always be broken down?"

Barnes chuckled. "I'm using the German code system, which has never been broken down, and never will be. With an Armenian complex, it's invulnerable. You'll see." She shrugged and relaxed on the cushions.

It was nearly dark when they came into Dijon; Barnes did not want to arrive in full daylight. They avoided the grand Hôtel de la Cloche and in a side-street off the main Rue de la Liberté, halted before a small hostelry, the Hotel Burgundy.

"We become brother and sister; the name is Smith; passports are ready in that name," said Barnes. "I'll take that letter, if I may. Meet you downstairs in half an hour."

She produced the letter Franklin had turned over, and they entered the little hotel, which had for lobby only the usual small office.

Once in his own room, Barnes tore open the letter, which contained a single sheet of paper. On this were three lines of unbroken typing in capital letters.

In ten minutes he had reduced this to the "cable-ese" of newspaper correspondents, which he then amplified into familiar English. The result was very definite:

BALKAN TENSION HOLDING UP ABYSSINIAN CAMPAIGN BUT PREPARATIONS GOING STEADILY FORWARD. LEAGUE OF NATIONS WILL CONTROL JUGO-SLAVIA. AIRPLANE FLEET PREPARING HERE FOR LONG FLIGHT.

Mussolini had once sent a squadron of twenty-odd ships across the Atlantic to America. He would be able to send a fleet of fifty bombers to Eritrea to act against the Ethiopians. No particular news here; Franklin might have lost this message without any dire consequences, thought Barnes angrily. Then he started, at a sudden thought. He held the paper against the electric bulb in his room. Between the lines of typing, appeared writing as the paper grew warm. He copied it swiftly, decoded this second and more secret message, then whistled softly.

MY BROTHER AT MARSEILLES INFORMS ME THAT TWO BELGIAN SHIPS CLEARED FROM THERE FOR BOMBAY. REALLY FOR DJIBOUTI WITH IMMENSE QUANTITIES WAR SUPPLIES CONSIGNED ADIS ABEBA.

There, by glory, was something!

DJIBOUTI was the French port of Somaliland, whence the railroad ran to Addis Ababa, capital of Abyssinia. The French, then, were permitting war supplies to go through, in defiance of all conventions. Why? Stumbling block. And Marie Nicolas had heard talk of those two ships. Belgian ships; and the Belgians had furnished drill-masters for the Abyssinian army. Something here, something big, if only the key could be obtained.

Hastily washing up, Barnes went downstairs and found Marie awaiting him in the lobby. They left the hotel; they were going to dine, he told her, at the Grande Taverne in the Rue de la Gare, near the railroad station. Reilly, if he got through alive from Paris, was to meet them there about eight.

"It is a risk meeting him, of course, but it must be done," said Barnes. "He has the key to all this business. Now, listen to what was in the letter," and he swiftly sketched the contents of the missive she had brought.

"What does it mean, then?" she asked.

"I don't know. That's what Reilly can tell us. Washington is involved somewhere; so is half Europe. Abyssinia is helpless, but has money to burn—an important point. Well, here we are."

The entered the café, took a corner table within view of the door, and settled down to satisfy hunger.

"Where did you leave the car?" asked the girl.

"In the street, handy for a quick getaway. Whether we'll stay the night, I can't say. Depends on Reilly and Rothstern. Our fat friend isn't so slow, you know," Barnes added thoughtfully. "We're taking chances stopping at hotels. By this time, our registration slip is at the police prefecture. Rothstern might figure you for Dijon, of course. We're bound to take chances any way you look at it," and he shrugged.

"Have you anyone here? Any of your friends?"

"No."

Dinner arrived. As the meal drew to its close and eight o'clock came and passed, Barnes grew more and more uneasy. Then the door opened; a gangling man with flaming red hair and clipped mustache entered and glanced around. He sighted Barnes, who rose.

"Hello, old chap," said Reilly. "Ah! And Marie as well, eh? Glad to see you enjoying life. You won't very long."

He dropped into a chair and fired a rapid order at the waiter, who vanished.

"Trouble getting here?" asked Barnes.

"Nothing else but. I've been driving that old Ford of mine over half the back roads in France. You know what's happened to the gang?" Barnes nodded. He liked this brisk, energetic Chicagoan.

"Sure. But we're not washed up yet. What have you for me? Spit it out."

"You're welcome to it," said Reilly, and grinned. From inside his hat he brought a small envelope. "And, by the way, you'd better be prepared to hustle. Ten miles out of town they caught me. I rammed their car into the ditch, but it'll mean that the net is spread here."

Barnes took the envelope and looked at Marie. "Sorry, comrade; you'll have to wait to get the news. Will you slip back to the hotel, get my suitcase put into the car, and drive the car here?

"Tell the hotel people we're going to join friends at the Hôtel de la Cloche. The rooms are paid for."

With a quick nod, the girl rose and swung away. Reilly looked after her; his face was suddenly drawn and tired.

"A swell girl, there," he said. "I'm done for. I'll stop here and let 'em grab me."

"You will not," said Barnes quickly. "You'll go with us. What's this thing?"

He tapped the envelope as he put it out of sight.

"PHOTOSTAT of an agreement between Rothstern and that chap Forville, in the French Foreign Office," Reilly said crisply. "Cost me a thousand bucks cash, but I got it a week ago. Forville will be made the goat if it should become public, of course; the French government is really back of it. Ever hear of Abyssinia?"

"Once or twice," Barnes replied. "Anything to do with war munitions?"

Reilly chuckled. "You're not so slow, huh? Right. Here's the layout—hold on."

The waiter came with the ordered dishes. Reilly, saying he had not eaten since morning, pitched in ravenously. When the waiter was gone, he spoke between bites.

"For three months, Rothstern, on the basis of this secret agreement, has shipped munitions into Abyssinia. Made money hand over fist at it. That Italy's going to grab the country is no secret. France is bitterly jealous of her already; so is Germany. Mussolini is all burned up over the disaster of Adowa, forty years ago, and means to avenge it. Well, he's going to run into another Adowa, that's all. The Italian army will be smashed; his prestige will never recover. Rothstern is behind the whole thing. A gigantic trap in the mountains.

"Get the picture? France then becomes the dominant power in Europe, and so forth."

"Holy smoke!" exclaimed Barnes, as he comprehended the reality. "What's it got to do with Washington? We don't give a hang about Abyssinia?"

"Sure," grunted Reilly, "they've hung it on the Paris ambassador; he thinks it's swell. The Abyssinian envoy has let it be understood that America will guarantee the integrity of Abyssinia; which is all rot. But they've got Rothstern scared stiff about it. So the fat boy wants to find out about that treaty. He thinks we might stop Italy from grabbing; more rot. He wants Italy to grab, burn her fingers, and take a tumble."

"I get you. What good is this photostat to us?"

"Proof. Our diplomatic corps doesn't dare touch it; the thing was swiped out of the French archives, you know. But any of us can handle it, with the fervent blessing of Washington. If Mussolini gets it, he has proof that France is double-crossing him. You knew I was bringing you orders to meet Grimaldi in Ostend, on neutral ground?"

"No! I was told to meet our ambassador there and take the treaty to London."

"All hooey, brother. You're to do it, sure, but the important thing is to meet Grimaldi. He's Mussolini's best friend. We didn't dare reach him in Paris; you can do it in Ostend. Give him the photostat—on condition Italy won't grab Abyssinia. If Grimaldi assents, Il Duce will probably stick to it."

Barnes saw the whole thing now. If Italy held off, that commercial treaty might or might not go through. All this was a job that no accredited diplomat could handle for a moment. Grimaldi, not the American ambassador, was the real work ahead of him.

"I get you. Grimaldi might not agree, though."

"He will if you tell him that Italy gets a fifty-fifty split in the treaty, and a concession to build a railroad into Addis Ababa. The black boys will probably repudiate the whole thing, even if Washington makes the treaty, but we should worry. Our game is to smash Rothstern—wheels within wheels, savvy?"

Barnes nodded. "What a whale of a scheme! It saves Abyssinia's independence and yet profits all concerned. Who thought it all up?"

"Those blacks aren't so dumb," and Reilly grinned. "Look here, you'd better skip out! Leave me here to act as decoy."

"Nothing doing. Come along. Marie must be outside by this time," and Barnes beckoned the waiter.

He paid his bill, and a moment later the two men left the restaurant together.

As they went out the door, a man rose from a table on the other side of the room, and made an abrupt signal. Two other men joined him, and all three hurriedly departed.

REILLY, crowded into the roadster seat with Barnes and Marie, continued his sketch of the situation as Barnes headed out of the city.

"You see, once the proof is in Grimaldi's hands, he's got Rothstern by the neck. And believe me, Mussolini would like to see that bird done for! France will have to sacrifice Rothstern, and so will Germany. They won't dare let him squawk. That's added incentive for us. We owe him something. Where you heading for now?"

"Troyes," said Barnes. "I'll have a man waiting there for me with news, food and anything else needed—including gas. We'll get there long before midnight. Then on to the Belgian border."

"I can't cross it," said Reilly. "You had better let me go."

"Be hanged to you!" Barnes snapped. "I'll manage it somehow."

They got out of town without incident and the powerful roadster began to eat up the miles of the highway, as the rolling hills of Burgundy fled past.

"Light's behind!" said Marie Nicolas, presently.

Although Barnes knew the road, it was strange to him at night; a hilly road with sharp curves and blind turns. Speed was impossible. Gradually the following car lights crept closer.

"Looks like a pinch," commented Reilly. "And those birds will shoot. They shot at me; that's why I rammed them off the road."

Barnes reached down with one hand, drew a pistol from the car pocket, and laid it in his lap. "This stuff has to get through," he said grimly. "If we're nabbed, you two step out and give up. You'll only get a week in jail at worst. Orders, understand?"

The minutes passed. That the other car was the faster, now became all too apparent. Barnes reflected swiftly, and came to a decision. Alone, he might outrun or outfight the enemy, no matter which; they were not French police, who would use pistols only as a last resource. But with Marie in the car, he could not risk her life so freely.

"Be ready to pile out," he said curtly. The other car was close now, its lights holding them in full glare.

Barnes slowed gradually. He ran along the edge of the road, giving plain evidence of his intention to stop. There was still a chance, of course, that the other car held nothing but tourists or fast travelers who wanted to pass. A honk-honk from behind as the pursuing car closed in and began to pass. It came alongside, roaring along without slowing. Then—

The jets of fire, the crashing of the windshield, the barking explosions of pistols. A wild cry from Marie.

Sheer blind fury seized Barnes. The whole windshield in front of him was shattered out. Glass flinders stung his face.

Like a flash, he stepped full on the gas, snatched up his own pistol, and as the roadster spurted into a roar after the other car, he began to fire. Shot after shot, steadily, always in the one place. Suddenly a scream drifted back to him. Then a chorus of voices. The car ahead veered, skidded off the road, went slap-bang into a tree with a terrific crash. One of his bullets had found the driver.

The roadster shot past. Barnes looked back once, saw no flames, and grimly held his course. To hell with them! They could take the consequences, so long as their car had not caught afire.

"Marie! Hurt?"

"No, no," came her gasp. "But Reilly—you'll have to stop—"

Barnes slowed, and presently ran to a stop. Like all European cars, this one had a right-hand drive. Thus, the other two had acted as shields for him against those bullets. And one had found Reilly. The red-headed Chicagoan was dead—had died at once, for a bullet had gone through his head.

"What'll we do?" exclaimed Marie, careless of the gashes in her arms from the shattered glass. "We can't leave him here."

"No. You drive. I'll hold him. We're well on our way to Troyes. I'll leave him with my man there, who will take care of it. The body can't be shipped home in any case; anyone who dies from violence must remain buried in France. That can all be taken care of later. The main thing now is to get on." They went on.

IT was a grim ride. Barnes sent his thoughts flitting ahead, groping with what might lie across the border. No such danger from the police as here. The whole French bureaucracy was riddled with graft and corruption and scandal; Belgium was another thing. He could understand why Reilly had held this photostat for days, no doubt in the hope of getting it to the Italian embassy, but in vain. Rothstern had paralyzed the little band of American volunteers.

For Rothstern knew of this photostat. What an incredible devil of mental agility, of information, of secret sources, that fat man must be! He had learned of this. He knew his own peril. He even knew—or guessed—that it was to reach Grimaldi on the Ostend musical expedition.

Barnes voiced his thoughts, as Marie sent the roadster roaring on. She had the whole story in her mind, now.

"If I'm stopped, you must carry on," he said. "The photostat is in my inside right coat pocket. You must put through the deal if I fail. Understand?"

"Yes," she said simply. The one word held volumes.

"Get the thing straight. Rothstern probably knows what I don't know—that I'm picked to meet the American ambassador in Ostend and carry that treaty over to London, where it can be sent in the diplomatic pouch without danger. That arrangement is of course a mask. I'm to meet Grimaldi, or someone is, with this photostat and make the deal. And Rothstern surely knows of the photostat."

"But you're to meet the American ambassador too?"

"Naturally. That can be done openly enough, without danger. There is probably going to be a whole diplomatic gathering at this musical affair next Friday. Which reminds me—I must arrange about tickets. It'll be held at the Kursaal, of course; that's the big concert place in Ostend. My man at Troyes will attend to it."

"Are you going to explain that code to me?"

"Yes. The minute we have an hour to ourselves. Over the border."

"Shall we get over?"

"We must."

Troyes was at last on the horizon, and the ghastly ride was presently at an end, and poor Reilly at peace. This was in a furtive little street behind the Hotel Terminus, where a plump, gray-bearded man and his two sons saw to everything. He put into the roadster a hamper of food and wine, and when Barnes introduced the girl to his unpronounceable name, he bowed to her like a courtier.

"Mademoiselle, I am honored. You behold but a damned dirty dog of an Armenian, as they called me at Eton in my youth; yet we Armenians may have our uses, eh? Here, Mr. Barnes, are telegrams. One, I fear, will cause you sadness."

They drove on, Marie taking the wheel while Barnes looked at the telegrams.

"I suppose," she asked, "that man was a prince or something?"

"Eh? Oh, not at all," said Barnes. "He was a multi-millionaire before the war. Look here! McGibbons was killed today, in Warsaw. An automobile accident."

"McGibbons?" she echoed in dismay. "Sandy McGibbons? Oh—"

"Exactly; one of our best men. Accident? Not a bit of it." The voice of Barnes was grim. "Now we've come down to murder. Poland, remember, is a close ally of Germany in the new alignment. Our other news isn't so good, either. Truxon left Nice today and landed in Paris this afternoon, by air; Stacey was with him. Rothstern went on by the same train from Lyon to Paris. Gave you up as a bad job, evidently. Once we get out of town, I'll drive. Tired?"

"Not a bit," she lied bravely.

Troyes fell behind.

A meal as they drove, with hot coffee and a dash of cognac from the hamper, made the cold night look different. Spare gasoline was in the luggage compartment; later, they filled the tank. It was a mad, wild flight through the morning hours; dawn found them speeding forward, with Marie huddled up asleep. Sunrise at last, and in the golden morning they railed up to the frontier station of the Douane, and Barnes adroitly conveyed a thousand-franc note to the customs inspector in a packet of cigarettes.

Ten minutes later they were in Belgium, unhindered; even the broken windshield had drawn no suspicion.

"Now what?" asked the girl.

"On to the city of Mons. Then hotel; sleep; rest; buy whatever we need. No hurry," and Barnes uttered a gay, joyous laugh. "To-day is Wednesday. We'll stop here till morning, get the windshield replaced, and drive on to Ostend tomorrow. Comrade, we've done it!"

"At a price," she murmured. Barnes lost his cheery air; his face darkened.

"Right. Let me tell you something; when I fight fire with fire, I don't use water. Rothstern murdered Reilly and McGibbons, and that signed his death-warrant. You can pull out of my game if you don't like it. Fair warning!"

She eyed his harsh, strong features with their hint of savage determination, and nodded. She made answer with quiet restraint.

"You're not the man you were; not the same. You're getting bigger, if not better. You're going far. And I'm trailing along, thanks."

"GOOD girl. You know. I've got something to fight for; we both have," broke out Barnes with sudden deep feeling. "Back home, these callow university pinks, these agitators, these damned communists who never heard of patriotism, say that Americans have no cause, nothing to fight for, no reason for loving country. Wait and see. By God, I'm going to carry things home to these murdering rats over here! This organization is now mine. I'm going to use it in my own way. And everyone else be hanged!"

"Good for you!" came her voice, low, vibrant, rich. "You're not afraid to do things; right or wrong, you do things. Most men don't, any more. They're afraid to make mistakes, afraid somebody will call them down. Ugh!"

"And let me tell you one thing," Barnes said, tapping her on the knee. "Your report on that conversation in the hotel in Nice—girl, that's big! It's going to change everything, all my plans. It shows me a lot. We'll not go into it now, for my brain's dead. By the way, take this photostat, won't you? Pin it under your dress and carry it; I'll feel safer."

"All right, Mr. Sphinx," she said, smiling, and the precious thing passed into her keeping.

Mons grew ahead of them at last, in mid-morning. Ten minutes after they arrived, Barnes was asleep. For the present, worries and cares were left behind.

That same evening, after Barnes had dispatched a sheaf of telegrams, they visited a movie together in delicious relaxation and safety. A good night's sleep followed. With morning, they were off, driving unhurried through the rich Belgian fields. The wild and frenzied flight north was like an evil dream over and done with.

Before reaching Ostend they halted for dinner, in order to delay their arrival until after dark. Marie Nicolas, getting a postcard, demanded a fountain pen.

"Haven't one," said Barnes. She stared at him blankly.

"But you have! What's that clipped to your waistcoat pocket?"

Barnes grunted, drew out the pen to which she referred, and replaced it.

"That," he said, "is a little improvement of my own on a parlor toy. Waiter! De quoi écrire. Well, Marie, this time tomorrow night either you or I should be hearing the Beethoven Mass and talking business with Grimaldi. I've instructed all my agents, by the way, that you're second in command."

"Oh! But—do you know you haven't explained that cipher?"

Barnes whistled. "Right! Later on, then. It'll take time. Get your postcard off and we'll be on our way."

OSTEND, the glittering Atlantic City of the Belgian coast, opened before them. Ostend, the cheap and flashy, shop-worn with years and British trippers. Barnes, as usual, avoided the big hotels and drew to a halt before a small and unostentatious hostelry half a block from the "board walk," as it would be termed in America.

"Behold the Belgian Lion!" he exclaimed gaily. "Warranted a cheap, inconspicuous, and small inn. As soon as we get rooms, will you chase out and find me a stenographer?"

"I'm one," she said.

"I must have one who can put English or French into Italian, which I don't know."

"I speak Italian perfectly."

Barnes broke into a laugh. "Good! We'll dispense with the stenographer."

They secured rooms on the same floor. Half an hour later, Barnes finished his dictation. He took the photostat, which he had requested from Marie.

"Doesn't it seem rather silly to have only one of those?" she asked.

"Precisely," and the gray eyes twinkled at her. "I'm going out now to find one of my men and have another made. Then we'll each have one. I've decided to let you conduct all negotiations with Grimaldi."

"What?" Her gaze widened on him. "But you—"

"Will be throwing Truxon off the trail. The performance begins at eight tomorrow evening. At seven, two tickets will be delivered here; the two seats next Grimaldi, his wife and secretary. You'll take them and go, presuming nothing happens to prevent you. If I don't show up, you'll have an empty seat beside you.

"Make an extra copy of that dictation and leave it for me, if you don't see me in the morning, at the hotel desk. Take your own copy with you. First, is the contents of the photostat; give that to Grimaldi and get his instant attention. Then give him the terms on which he may have the photostat—the second dictation. If he signs these, give him the photostat and the game's finished."

"But you—"

"What? Are you going around all your life repeating those two words?" demanded Barnes. "Me, I've got to see the American ambassador in the afternoon, let Truxon and possibly Rothstern follow me around, and maybe buy me off.

"Who knows? I'll shove the photostat under your door if you're asleep when I get back."

"I was trying to tell you," she retorted, "that you can't have a copy made at night."

Barnes regarded her with lifted brows.

"You might tell me, also," he rejoined, "that it is impossible to get, from the eye of a dead man, the picture of his murderer. In both cases, you would be wrong—quite contrary to general belief. I'll go into the matter scientifically with you the next time we find a murdered man and no clue to his killer. Meanwhile, my dear, enjoy yourself, keep off the streets, and don't talk with strange men.Au revoir!"

He departed, with a grin, leaving her half angry, half perplexed.

An hour later, after a long conversation with a lean, dark man whose curio shop-window bore the startling name of Djismardahossian, Barnes went to one of the largest hotels in Ostend. No other, in fact, than the singularly named Hotel Delicious. Here he displayed himself prominently about the lobby, registered, secured a room, went to his room and turned in for the night.

"She can handle Grimaldi better than I can anyhow," he reflected cheerfully, as he switched off his light. "And I'm the bird they're all out to catch. So, with luck and one stone, I'm liable to kill two birds and prove that the hand is quicker than the eye. Good hunting tomorrow, Rothstern—damn your black heart!"

When Marie Nicolas wakened next morning, she found an envelope shoved under her door. In the envelope was the photostat. On the envelope was the rubber stamp of The Sphinx, U.S.A. But she saw nothing of Barnes that day.

AT three o'clock on Friday afternoon, Barnes was ushered into the presence of the American ambassador to France, who by some curious chance was also stopping at the Hotel Delicious. The diplomat looked worried, and he was worried.

"Barnes, this damned nonsense must stop," he exclaimed, in the undiplomatic language of big business. "Your wild-cat organization is busted. These European crooks have got the whole crowd by the tail. Reilly's dead. McGibbons is dead. Others are in jail. You must give up the whole show; it's come to an end."

"On the contrary," said Barnes coolly, "it's just begun. If you think two boys like Reilly and McGibbons are going to be bumped off, and nothing done about it, guess again. The crowd's busted, sure, just as I predicted it would be. I'm running the show with a crowd of my own, now."

The other gave him a keen, angry glance.

"You're in earnest?"

"Absolutely and entirely, sir." The level glance of Barnes was like gray steel.

"You're a fool. These secret agents are dirty, double-crossing, treacherous rats. Men like you can't hope to fight 'em."

"Terriers wipe out rats," said Barnes. "Me, I'm the damndest terrier you ever saw, right now. This time tomorrow I can walk down the boulevards in Paris and the police will tip their hats to me instead of trying to grab me. Wait and see."

"You're a blasted ass. Europe is in a ticklish condition. None of us in the service can be responsible for you. If you get in a jam, you're without appeal. You've no connection with Washington. Damn it, I admire you with all my heart, but—"

"You stick in the embassy and I'll play the small-time circuit," and Barnes grinned. "What you don't know, won't hurt you. With Marie Nicolas and a few of the old gang, I'm going ahead; you might tip off the other appointees from Washington to this effect. Now, I'm in a bit of a rush. Do you want me to take that treaty draft over to the London embassy?"

"Yes. It's blasted important too." The ambassador extended a sealed envelope.

"Wrong; it'll die a-borning," said Barnes. "I've learned something about it. This treaty is a blind to get Europe all het up over America's butting into the African game. Abyssinia would repudiate the treaty even if we bothered about it, which we won't."

And he departed, leaving the ambassador frowning after him, more worried than ever.

BARNES left the hotel. He strolled over toward the plage, the wide expanse of sands, villas, bathing huts, stretching up to the massive concrete harbor works. He paused at a café, seated himself with a sigh, and ordered a Rossi. It was just four o'clock. He squirted the glass full of seltzer water, pinched the slice of lemon peel into the blood-red mixture, then sipped at it contentedly and watched the passing throng.

Ten minutes later a large, beaming, jovial figure came swinging along, stopped short at sight of Barnes in well-simulated astonishment, then came to his table.

"My friend, Mr. Barnes, of all people!" exclaimed Rothstern, cordially. "May I sit down"

"Why not?" Barnes said. "Trailed me, have you? No use lying about it?"

Rothstern chuckled, as he seated himself and ordered a beer. "I suppose not. We need not lie to each other, hein?" He wiped his bald spot and beamed. "Well, like you Americans, I shall get down to business. Come, Mr. Barnes, we need not be unfriendly. You are going to England; would not a little English money come in useful over there?"

"A little? No," said Barnes curtly. "A whole lot might, though."

Rothstern heaved with laughter. "Ah, you Americans! Come, my friend. I will make you an offer," and his voice dropped until it was barely audible. "Two thousand English pounds if you will let me copy the document you received from the American ambassador. No one will ever know. It will take ten minutes."

"You think I'd sell out? To you?"

"Yes," said Rothstern blandly. "Remember we have met before; you were ready enough to take my money then. Why not now? The cash is ready. We need only step over to my hotel. Why should we not remain friends, to the advantage of both?"

The gaze of Barnes lowered. "Hm! Maybe you're right, Rothstern. If what I hear is true, the game is up for most of us Americans, anyhow."

"Ah, my boy! With Papa Rothstern your friend, who knows? Come. Finish your drink, step to the Grand Hotel with me, and in fifteen minutes—pouf! It is over."

Barnes kept his eyes veiled, to hide their hot agitation. So plausible was the man that he might have been fooled, had not Marie Nicolas overheard the actual intention of Rothstern, had he not known who was responsible for the deaths of Reilly and McGibbons. Abruptly, he tossed down his drink.

"All right," he said with decision. "But I'll not walk over with you, naturally."

"Oh, as you like!" Rothstern rose. "Come in five minutes. Take the elevator to the fourth floor; I'll be awaiting you in the corridor. So long!"

He swung away with a wave of his malacca stick. Barnes looked after him, eyes narrowed, cold, implacable.

Five minutes later, Barnes rose, paid for the drinks, and walked toward the Grand Hotel. The die was cast now; he was gambling everything on one turn of the cards, almost literally. As he had told the ambassador, it was make or break this same night.

He had no illusions whatever about Rothstern's intentions, or the trap laid for him.

The Grand Hotel, with its gardens and spacious lobby, opened before him.

He walked steadily to the elevators, took a car up, and left it at the floor designated. Rothstern was waiting.

"Ah! You are wise, my friend, very wise; I welcome you," said the fat man with hearty cordiality. "Come along. I have everything ready. Here is the room—" and he flung open the door of a corner room, with a laughing bow.

Barnes, with a slight shrug, walked in. The door closed behind him. At one side stood Truxon, at the other the rat-like Stacey, each with a pistol in hand.

"Hello," exclaimed Barnes. "Why not a machine gun? I thought this was a private affair, Rothstern."

"An excess of zeal, perhaps—merely to make sure you are not armed, my friend," purred Rothstern. "You do not object?"

"Not in the least." Barnes held up his arms. Truxon, he of the lean and savage features, stepped forward and frisked him—efficiently.

"So that is finished!" exclaimed Rothstern. "Now we shall all be friends, Stacey! Go and get the motorcar ready for us. Mr. Truxon, you will remain, if Mr. Barnes has no objection?"

"I have," said Barnes coolly. "Our talk is to be private."

"Very well." Rothstern turned, and winked significantly at Truxon. "Go into the adjoining room, and wait. But leave the door open, mind! Come, Mr. Barnes, we can settle matters comfortably at the table."

STACEY departed, with an air of disappointment. Truxon, scowling savagely, went into the next room of the suite. Rothstern showed his victim to a chair at the center table, himself taking a seat opposite.

"Now," he said, rubbing his hands, "first, the treaty draft. Here, I have paper ready,"

"And the money?" asked Barnes in a cold voice.

"Ah, yes! The money, of course." Rothstern:reached into his pocket and brought forth an envelope, which he handed over. His gaze was greedy, excited, nervous. Barnes produced the sealed envelope which the ambassador had given him; and Rothstern snatched at it, broke the seals, drew out the folded paper. "Ah, this is it!"

"Of course," said Barnes. "You want to copy it. Here's a pen."

He took the fountain pen from his pocket—then froze abruptly. Rothstern's hand jumped forward, covering him with a pistol. The fat, jovial features were suddenly cruel, tense, deadly.

"Hands there on the table—that's right!" cried Rothstern. "All right, Truxon."

The latter appeared, giving Barnes a quick, cold grin.

"So, my very good friend!" snarled Rothstern viciously. "You think to play with me, eh? You think to take my money and go? Not so quickly, young man. You have a lot to learn. You have other things I want to see; what about your meeting with the Italian ambassador, Grimaldi? Yes, I know about that. You're helpless. You're in my hands now; I have the treaty entrusted to you. Be careful, or I can ruin you!"

"Rothstern, you're a good actor," said Barnes coolly. "Trying to work me, are you? Trying to force me to cough up all I know—and then you'll kill me. Oh, don't deny it. What about your instructions to Truxon and Stacey, that night you met them in the hotel at Nice?"

Rothstern started. His eyes distended a trifle. "Ah! Herr Gott! How do you know that?" he muttered thickly.

"Never mind. No time to discuss it," Barnes rejoined. "I've only time to remind you of something, Rothstern. You're a damned murderer. You were behind the death of Reilly, of McGibbons, just as you expected to be behind my death."

"Well?" The gaze of Rothstern bored into him, no longer jovial, but wicked and cold with hatred. "What of it?"

Barnes shrugged and looked down. "I'm just reminding you, that's all. Suppose you go ahead and copy the paper."

And, casually, he unscrewed the top of the fountain pen and laid it down. Then he leaned back in his chair, produced a cigarette, and lit it, with an air of perfect unconcern.