Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

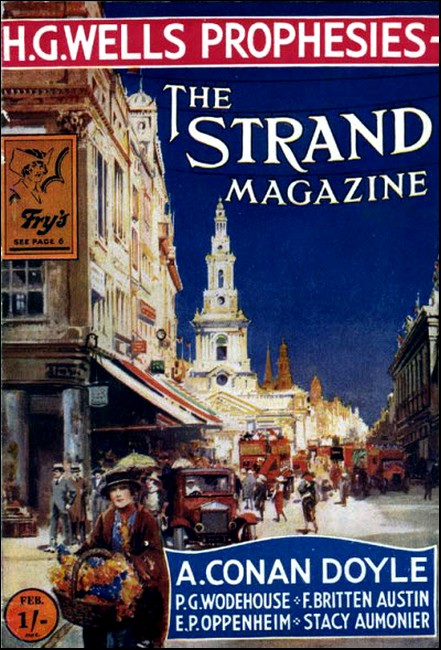

The Strand Magazine, February 1924, with

"The Gifts of the New Sciences: H.G. Wells Prophesies"

"The coming hundred years or so will mark a revolution in human

affairs altogether more profound than that merely material revo-

lution of which our great grandparents saw the early beginnings."

ONE of the most attractive and at the same time most baffling of speculations is to guess about the progress of science and about the possible inventions of the years ahead of us. Baffling and uncertain it is bound to be. As a friend of mine put it, "it is trying to think about what won't be thought of for ever so long." But that is just a little more witty than it is true. Coming inventions cast their shadows before—often shadows that are centuries long—and one may have a reasonable conviction that a tree is going to bear fruit even when the blossom is just budding. Frosts, blights, and suchlike disasters may disappoint the most justifiable hopes for a year or even for a succession of years; nevertheless a survey of the possible scientific harvest is well worth making. It may even—to extend our horticultural image—set us spraying or protecting some threatened crop.

The last hundred years has been a century productive on a stupendous scale of mechanical inventions arising out of physical and chemical discoveries. It has been an epoch, a corner in human history. There have been great advances in medicine and surgery also, but these—the use of anaesthetics and antiseptics for example and the applications of microscopy—have been largely by-products of chemical and physical progress. There has also been a great expansion and clarification of biological knowledge, but although this has produced profound effects upon religious thought and moral ideas, it has not yet given any such revolutionary practical results in human affairs as have the inorganic sciences. It has made possible the new developments in psychology upon which I shall have more to say presently, but it has yielded no dividends directly. When we talk of inventions and the triumphs of science it is of steamships and great machines, rapid transport, electricity, wireless, and the aeroplane that we think, and when we turn to the future our first idea is of another shelf-ful of still vaster and more astonishing mechanical contrivances. But that may be just the common error of prophesying by continuing the current movement of things in a straight line. It is quite possible that there may be no further physical or mechanical discoveries of first-class importance forthcoming for a very long time. That at any rate is my own conviction.

OF course there will be improvements in detail, increases of efficiency, economies and so forth. The railways may be scrapped, and probably will be scrapped within another half century, as slow and wasteful; we may have a steady improvement in road material; the aeroplane and possibly the airship may go on developing and improving; we may presently transmit pictures as well as sounds by wireless, survey and map the Polar regions, and so forth and so on. But there will be nothing beyond the aeroplane; only an improved aeroplane. Nothing beyond wire-borne or wireless telegraphy; only speedier and more effective transmission. We shall thrash out and make the most of that great harvest of the last hundred years that has come in from the physical field, but from that field I do not believe that there will be any fresh harvest, any new things now, any really revolutionary changes, for quite a long time.

This will strike some readers as a flat contradiction to much current expectation. They will ask: "What about all these new discoveries in physics about which we have heard so much? What about Einstein? What about the energy of the atom?"

Well, these things, I think, are just the first blossoms of another Spring whose harvest may still be hundreds of years away. We are not likely to get much out of them but wonder for a long time. Einstein has given us a new, a more free and more subtle way of thinking about the space-time system in which we live. But that is unlikely to have any immediate practical reaction upon human life at all. And there is much wild and baseless talk about the possible utilization of atomic energy; but though that is good enough for a fantastic story it is not good enough for a serious discussion of practical developments in the near future. We have come to know that several elements, and possibly most or even all elements in the space-time system we call our universe, are undergoing a steady—and in most cases an extremely slow—process of decomposition which releases energy. And that is a very marvellous thing to realize. We already make a clumsy, half superstitious use of that released energy in the radium treatment in medicine. But nobody has yet made the ghost of the shadow of a suggestion how that process of decomposition might be delayed or accelerated. Current science has no more practical justification for hope that this can be done than that we may presently be able to turn on or turn off the gravitational pull and make things heavier or lighter.

Our universe, which carries us along with it through time, has these characteristics of gravitation and molecular decomposition and we do not know why it has them. They are as blank riddles to the greatest professors of physics and chemistry as they arc to us ordinary people. Some day it may begin to dawn upon men why these things are so, and then our race will get to business. But I do not believe that atomic energy is coming into human affairs until such names as Einstein, Curie, and Soddy, and so forth, seem as remote and past as do the names of Archimedes and Hero to-day. Hero, as the reader will remember, described a turbine steam engine nineteen centuries before it became of any utility. The primary properties of frictional electricity were on record in the time of Aristotle. The fruit of these curious flowers of knowledge took a score of centuries to ripen.

That first great wasteful harvesting of material science, which has been going on during the past hundred years, is, I believe, drawing to its end. The next is still too far off from our present experience for us even to guess about it. It is in quite other directions now that I think we must look for the next main crop of practical results from scientific thought and research.

THE past century has been the supreme century of material achievement; the present and the twenty-first centuries will, I believe, be the great fruiting and harvesting time of psychological and physiological science. Man having run all over his world from pole to pole, having learnt how to fly round it in seven or eight days and how to look or speak round it in a flash, will presently, I think, become introspective and turn his practical attention to himself.

Unfortunately, it is necessary nowadays, before one talks in this popular way of psychological science, to make it perfectly plain that one does not intend that term to cover any of that queer traffic in messages from the dead and the like which figures in certain circles as "psychic" science. The whole of this mass of legend and lore is no doubt of interest to the psychologist, but rather because of what it teaches us of the infirmities of the human mind as a truth-seeking, truth-testing instrument than for any light it throws upon the nature of men or things.

For a third of a century since his college days the writer has watched this flow of necromancy, telepathic experiment, and pseudo-scientific inquiry; for some years he was a member of the English Society for Psychical Research; he has observed the exploits of clairvoyants, read occult books, so far as such books are readable, heard the late W.T. Stead relate the adventures of his Double, watched the careers of Sir A. Conan Doyle and Sir Oliver Lodge, endured the marvellous histories of many inferior storytellers, and his growing conviction is that in this vast cloud of witnesses, in this fog of unprogressive assertions, there is no grain of any substantial reality, that there is nothing in it at all beyond deliberate fraud, unconscious fraud, self-deception, the will to believe marvels, the craving to be marvellous, the suggestibility of unguarded minds, tricks of divided personalities, uncritical treatment of coincidences and resemblances, the obstinacy of men committed to a view, very ancient traditions about ghosts and magic received as fables and then strengthening to belief, reinforcing legends from the East, hallucinations fostered and welcomed, and, last but not least, the moral decay and imaginative excesses due to the use of drugs. As the years have passed the writer has become less and less interested in the raps and the scratchings, the enigmatical mutterings of the medium, the automatic scrawlings on the table, and more and more curious and fascinated by the motives and hidden thoughts of those who sat around the revelation. Later on he may be able to deal with this queer world of the psychic investigator; at present he mentions it only to express his complete scepticism of any progress or promise in that world.

BUT what is of the greatest promise in the science of the present time is the new study of human motives which centres about what is called psycho-analysis. The science of psychology as it was presented to me when I took my educational diploma a third of a century ago was about as empty a science as one could well imagine. It was resonantly empty. Sully's "Psychology," the first text book I encountered, a book written by an Englishman of French origin, was as logical and lucid a development of false classifications and negligently observed realities as the Latin mind has ever produced. It was as handsome and impressive as the Eiffel Tower or the Arc de Triomphe, and like those glories it got nowhere and did nothing. Mental phenomena were neatly classified into Thinking and Feeling and Willing; and the methodical assembling of sensations into percepts and of percepts into concepts which it expounded so charmed my sense of order that for quite a long time I did not realize, and indeed it was only after I had read Hoffding and William James that I began to realize, that, as a matter of fact, no such synthesis went on in my mind at all, but quite different and much more complicated processes.

The advances that have been made in psychology since then have been enormous. In the last thirty or forty years psychology has laid out a whole new scheme of foundations. It has passed through a period of establishment very much as the science of physics did in the later seventeenth century, and the science of chemistry in the early nineteenth. Much light has come in from the side of experimental neurology, but the greater beginnings of the new psychology lie in the works of Freud And Jung. These two men, so different from each other in character and quality, Freud the homely and absurd and Jung the almost too poetic, will take a place side by side in the history of their field of science comparable to that of Gilbert or Newton or Faraday or Pasteur in their respective fields. They are initiators of primary importance. They have broken up a soil that was previously hard and obdurate, and now it is bearing crops in increasing abundance.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.