The Story of a Great Schoolmaster is a 1924 biography of Frederick William Sanderson (1857-1922) by H. G. Wells. It is the only biography Wells wrote. Sanderson was a personal friend, having met Wells in 1914 when his sons George Philip ('Gip'), born in 1901, and Frank Richard, born in 1903, became pupils at Oundle School, of which Sanderson was headmaster from 1892 to 1922. After Sanderson died while giving a lecture at University College London at which he was introduced by Wells, the famous author agreed to help produce a biography to raise money for the school. But in December 1922, after disagreements emerged with Sanderson's widow about his approach to the subject, Wells withdrew from the official biography (published in 1923 as Sanderson of Oundle; Wells wrote much of the text but the volume was published without listing an author) and published his own work separately. —Wikipedia

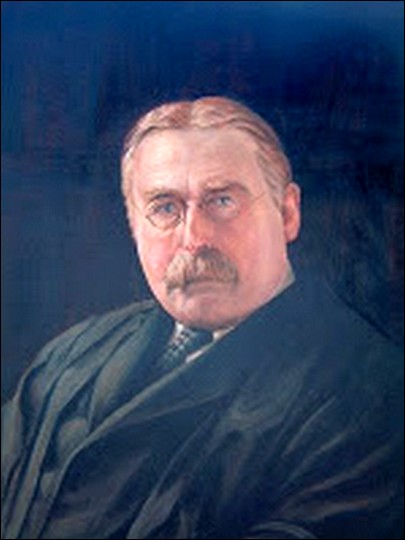

Portrait of Frederick William Sanderson

Coat-of-Arms of Oundle School

Of all the men I have met—and I have now had a fairly long and active life and have met a very great variety of interesting people—one only has stirred me to a biographical effort. This one exception is F.W. Sanderson, for many years the headmaster of Oundle School. I think him beyond question the greatest man I have ever known with any degree of intimacy, and it is in the hope of conveying to others something of my sense not merely of his importance, but of his peculiar genius and the rich humanity of his character, that I am setting out to write this book. He was in himself a very delightful mixture of subtlety and simplicity, generosity, adventurousness, imagination and steadfast purpose, and he approached the general life of our time at such an angle as to reflect the most curious and profitable lights upon it. To tell his story is to reflect upon all the main educational ideas of the last half-century, and to revise our conception of the process and purpose of the modern community in relation to education. For Sanderson had a mind like an octopus, it seemed always to have a tentacle free to reach out beyond what was already held, and his tentacles grew and radiated farther and farther. Before his end he had come to a vision of the school as a centre for the complete reorganisation of civilised life.

I knew him personally only during the last eight years of his life; I met him for the first time in 1914, when I was proposing to send my sons to his school. But our thoughts and interests drew us very close to one another, I never missed an opportunity of meeting and talking to him, and I was the last person he spoke to before his sudden death. He was sixty-six years of age when he died. Those last eight years were certainly the richest and most productive of his whole career; he grew most in those years; he travelled farthest. I think I saw all the best of him. It is, I think, no disadvantage to have known him only in his boldest and most characteristic phase. It saves me from confusion between his maturer and his earlier phases. He was a much stratified man. He had grown steadfastly all his life, he had shaken off many habitual inhibitions and freed himself from once necessary restraints and limitations. He would go discreetly while his convictions accumulated and then break forward very rapidly. He had a way of leaving people behind, and if I had fallen under his spell earlier, I, too, might have been left far behind. He was, I recall, a rock-climber; he was a mental rock-climber also, and though he was very wary of recalcitrance, there were times when his pace became so urgent that even his staff and his own family were left tugging, breathless and perplexed, at the rope.

Out of a small country grammar-school he created something more suggestive of those great modern teaching centres of which our world stands in need than anything else that has yet been attempted. By all ordinary standards the Oundle School of his later years was a brilliant success; it prospered amazingly, there was an almost hopeless waiting-list of applicants; boys had to be entered five years ahead; but successful as it was, it was no more than a sketch and demonstration of the great schools that are yet to be. I saw my own sons get an education there better than I had ever dared hope for them in England, but from the first my interest in the intention and promise of Oundle went far beyond its working actualities. And all the educational possibilities that I had hitherto felt to be unattainable dreams, matters of speculation, things a little too extravagant even to talk about in our dull age, I found being pushed far towards realisation by this bold, persistent, humorous and most capable man.

Let me first try to give you a picture of his personality as he lives in my memory. Then I will try to give an account of his beginnings, as far as I have been able to learn about them, and so we will come to our main theme, _Sanderson contra Mundum,_ the schoolmaster who set out to conquer the world. For, as I shall show, that and no less was what he was trying to do in the last years of his life.

'Ruddy' and 'jolly' are the adjectives that come first to mind when I think of describing him. He had been a slender, energetic young man his early photographs witness; but long before I met him he had become plump and energetic, with a twinkling appreciation for most of the good things of life. His complexion had a reddish fairness; he had well-modelled features, thick eyebrows and thick moustache touched with grey, and he wore spectacles through and over and beside which his active eyes took stock of you. About his eyes were kindly wrinkles, and generally I remember him as smiling—often with a touch of roguery in the smile. Quick movements of his head caused animating flashes of his glasses. He was carrying a little too much body for his heart, and that made him short of breath. His voice was in his chest, there was a touch of his native Northumbria in his accent, and he had a habit of speaking in incomplete sentences with a frequent use of the interrogative form. His manner was confidential; he would bend towards his hearer and drop his voice a little. 'Now what do you think of ——?' he would say, or 'I've been thinking of ——' so and so. At times his confidential manner became endearingly suggestive of a friendly conspirator. This, as yet, he seemed to say, was not for too careless a publication. You and he understood, but those other fellows—they were difficult fellows. It might not be practicable to attempt everything at once.

That reservation, that humorous discretion, is very essential in my memory of him. It is essential to the whole educational situation of the world. He was an exceptionally bold and creative man, and he was a schoolmaster, and that is perhaps as near as one can come to a complete incompatibility of quality and conditions. In no part of our social life is dull traditionalism so powerfully entrenched as it is in our educational organisation. We have still to realise the evil of mental heaviness in scholastic concerns. We take, very properly, the utmost precautions to exclude men and women of immoral character not only from actual teaching but also from any exercise of educational authority. But no one ever makes the least objection to the far more deadly influences of stupidity and unteachable ignorance. Our conceptions of morality are still grossly physical. The heavier and slower a man's mind seems to be, the more addicted he is to intellectual narcotics, the more people trust him as a schoolmaster. He will 'stay put.'

A timid obstructiveness is the atmosphere in which almost all educational effort has to work, and schoolmasters are denied a liberty of thought and speech conceded to very other class of respectable men. They must still be mealy mouthed about Darwin, fatuously conventional in politics, and emptily orthodox in religion. If they stimulate their boys they must stimulate as a brass trumpet does, without words or ideas. They may be great leaders of men—provided they lead backwards or no whither. Sanderson in his latter days broke into unexampled freedom, but for the greater part of his life he was—like most of his profession—'wading hips-deep in fools,' and equally resolved to work out his personal impulse and retain the great opportunities that the governing body of Oundle School had, almost unwittingly, put into his hands. He was therefore not only a great revolutionary but something of a Vicar of Bray. A large part of the amusing subtlety of his personality was the result of the balanced course he had to pursue. In all he did, in all he said, he was feeling his way. No other schoolmaster—and there must be many a rebellious heart lying still in the graves of dead schoolmasters and many a stifled rebel in the schoolrooms of to-day—no other schoolmaster has ever felt his way so discreetly, so far and, at last, so triumphantly.

I remember as a very characteristic thing that he said one day when I asked for his opinion of a particularly progressive and hopeful addition to his board of governors: 'He does not know much about schools yet, but he will learn. Oundle will teach him.' And in his last great lecture, he flung out a general 'aside'—that lecture was full of astonishing 'asides'—'I turned round on the boys and the parents,' he said, _'both are my business.'_

Never was schoolmaster so emancipated as he in his latter years from the ancient servility of the pedagogue. Not for him the handing on of mellow traditions and genteel gestures of the mind, not for him the obedient administration of useful information to employers' sons by the docile employee. He saw the modern teacher in university and school plainly for what he has to be, the anticipator, the planner, and the foundation-maker of the new and greater order of human life that arises now visibly amidst the decaying structures of the old.

Sanderson was born and brought up outside the British public-school system that he was to affect so profoundly. His early education was obtained in a parish school. His father was employed in the estate office of Lord Boyne at Brancepeth in Durham. There were several brothers but they all died before manhood, and the scanty indications one can glean of those early years suggest a slender, studious, and probably rather delicate youngster. He was never very proficient in any out-of-door games. In the early days at Oundle he careered about on a bicycle; in later years he played tennis; his vacation exercise was rock-srambling. He became a 'student-teacher,' so the official Life phrases it, at a school at Tudhoe, but whether there was any difference between being a student-teacher at a school at Tudhoe and being an ordinary pupil-teacher in an ordinary elementary school under the English Education Department I have been unable to ascertain. He was already notable in his village world as exceptionally intelligent, industrious, and ambitious, and with a little encouragement from the local vicar and one or two friends he effected an escape from the strangling limitations of elementary teaching.

He may have aimed at the church at that time. At any rate he gained a scholarship and entered Durham University as a theological student. He did well in Durham University both in theology and mathematics; he was made a Fellow and he was able to go on as a scholar from Durham to the wider and more strenuous academic life of Cambridge. At Cambridge theology drops out of the foreground of the picture. He took a fairly good degree in mathematics, and he worked for the Natural Science Tripos. He did not fight his way up into that select class which secures Cambridge fellowships, but he had made a reputation as an able, hard, and honest worker; he was much sought after as a coach, and he was given a lectureship in the woman's college of Girton. From this he went as senior physics master to the big school for boys at Dulwich.

A photograph of him in the early Dulwich period shows him slender and keen-looking, already bespectacled and with a thick moustache; except for the glasses not unlike another ruddy north-countryman I once knew, the novelist George Gissing. Both were what one might call Scandinavian in type. But Gissing was as despondent as Sanderson was buoyant. In those days, an old Dulwich associate tells me, Sander.. son was in a state of great mental fermentation. He loved long walks in his spare time, and along the pebbly paths and roads and up and down the little hills of that corner of Kent, the two of them talked out a hundred aspects and issues of the perplexing changing world in which they found themselves.

It was the world of the eighteen-eighties they were looking at, before the first Jubilee of Queen Victoria, and it may be worth while to devote a paragraph or so to a reconstruction of the moral and intellectual landscape this lean and eager young man was confronting.

Upon the surface and in its general structure that British world of the eighties had a delusive air of final establishment. Queen Victoria had been reigning for close upon half a century and seemed likely to reign for ever. The economic system of unrestricted private enterprise with privately owned capital had yielded a great harvest of material prosperity, and few people suspected how rapidly it was exhausting the soil of willing service in which it grew. Production increased every year; population increased every year; there was a steady progress of invention and discovery, comfort, and convenience. Wars went on, a marginal stimulation of the empire, but since the collapse of Napoleon I no war had happened to frighten England for its existence as a country; no threat of warfare that could touch English life or English soil troubled men's imagination. Ruskin and Carlyle had criticised English ideals and the righteousness of English commerce and industrialism, but they were regarded generally as eccentric and unaccountable men; there was already a conflict of science and theology, but it affected the national life very little outside the world of the intellectuals; a certain amount of trade competition from the United States and from other European countries was developing, but at most it ruffled the surface of the national self-confidence. There was a socialist movement, but it was still only a passionless criticism of trade and manufacturers, a criticism poised between aesthetic fastidiousness and benevolence. People played with that Victorian socialism as they would have played with a very young tiger-cub. The labour movement was a gentle insistence upon rather higher wages and rather shorter hours; it had still to discover Socialism. In a world of certainties the rate of interest fell by minute but perceptible degrees, and as a consequence money for investment went abroad until all the world was under tribute to Britain. History seemed to be over, entirely superseded by the daily paper; tragedy and catastrophe were largely eliminated from human life. One read of famines in India and civil chaos in China, but one felt that these were diminishing distresses; the missionaries were at work there and railways spreading.

It was indeed a mild and massive Sphynx of British life that confronted our young man at Dulwich and his friend, an amoeboid Sphynx which enveloped and assimilated rather than tore and devoured. It had not been stricken for a generation, and so it felt assured of the ages. But beneath its tranquil-looking surfaces many ferments were actively at work, and its serene and empty visage masked extensive processes of decay. The fifty-year-old faith on which the social and political fabric rested—for all social and political fabrics must in the last resort rest upon faith—was being corroded and dissolved and removed. Britain in the mid-Victorian time stood strong and sturdy in the world because a great number of its people, its officials, employers, professional men and workers honestly believed in the rightness of its claims and professions, believed in its state theology, in the justice of its economic relationships, in the romantic dignity of its monarchy, and in the real beneficence and righteousness of its relations to foreigners and the subject-races of the Empire. They did what they understood to be their duty in the light of that belief, simply, directly, and with self-respect and mutual confidence. If some of its institutions fell short of perfection, few people doubted that they led towards it. But from the middle of the century onward this assurance of the prosperous British in their world was being subjected to a more and more destructive criticism, spreading slowly from intellectual circle into the general consciousness.

It is interesting to note one or two dates in relation to Sanderson's life. He was born in the year 1857. This was two years before the publication of Darwin's _Origin of Species._ He was growing up through boyhood as the application of the Darwinian criticism of life to current theology was made, and as the great controversy between Science and orthodox beliefs came to a head. Huxley's challenging book, _Man's Place in Nature,_ was published in 1863; Darwin became completely explicit about human origins only in 1871 with _The Descent of Man._ Sanderson, then a bright and forward boy of fourteen, was probably already beginning to take notice of these disputes about the fundamentals, as they were then considered, of sound Christianity.

He was already at college when Huxley was pounding Gladstone and the Duke of Argyll upon such issues as whether the first chapter of Genesis was strictly parallel with the known course of evolution, and whether the miracle of the Gadarene swine was a just treatment of the Gadarene swineherds. Sanderson's Durham and Cambridge studies and talks went on amidst the thunder of these debates, and there can be little doubt that his early theology underwent much bending and adaptation to the new realisations of the past of man, and of human destiny that these discussions opened out. He did not take holy orders but he remained in the Anglican Church; manifestly he could still find a meaning in the Fall and in the scheme of Salvation. Many other promising teachers of his generation found this impossible; such men as Graham Wall as, for example, felt compelled for conscience' sake to abandon the public-school teaching to which they had hoped to give their lives. Wallas found scope for his very great gifts of suggestion and inspiration in the London School of Economics, but many others of these Victorian non-jurors were lost to education altogether.

The criticism of the economic life and social organisation of that age was going on almost parallel with the destruction of its cosmogony. Ruskin's _Unto this Last_ was issued when Sanderson was four years old; _Fors Clavigera_ was appearing in the seventies and the early eighties. William Morris was a little later with _News from Nowhere_ and _The Dream of John Ball;_ they must have still been vividl y new books in Sanderson's Cambridge days. Marx was little heard of then in England. He was already a power in German socialism in the seventies, but he did not reach the reader of English until the eighties were nearly at an end. When Sanderson discussed socialism during those Dulwich walks, it must have been Ruskin and Morris rather than Marx who figured in his talk. Al though there remains no account of those early conversations, it is easy to guess that this stir of social reconstruction and religious readjustment must have played a large part in them. Sanderson meant to teach and wanted to teach; he was quite unlike that too common sort of schoolmaster who has fallen back into teaching after the collapse of other ambitions; like all really sincere teachers he was eager to learn, open to every new and stimulating idea, and free altogether from the malignant conservatism of the disappointed type.

He kept that adolescent power of mental growth throughout life. I remember my pleased astonishment on my first visit to Oundle to find in his library—I had drifted to his bookshelves while I awaited him—a row of the works of Nietzsche (who came into the English-speaking world in the late nineties) and recent books by Bertrand Russell and Shaw. Here was a schoolmaster, a British public schoolmaster, aware that the world was still going on! It seemed too good to be true. But it was true, and in the end Sanderson was to die, ten years, shall we say?—or twenty, ahead of his time.

And while we are placing Sanderson in relation to the intellectual stir of the age let us note, too, the general shape of human affairs as it was presented to his mind. It was an age of steadily accelerated political change, and of a vast increase in the population of the world. The fifties and sixties of the nineteenth century had seen the world-wide spread of the railway and telegraph network, and a consequent opening up of vast regions of production that had hitherto lain fallow. The screw was replacing the ineffective paddle-wheel of the earlier steamships and revolutionising ocean transport. There was a great increase in mechanical and agricultural efficiency. We still call that time the mid-Victorian period, but the history teacher of the future, more sensible than we are of the innocence of good Queen Victoria in any concern of importance to mankind, is more likely to distinguish it as the Advent of the New Communications. These new inventions were 'abolishing distance.' They were demanding a political synthesis of mankind. But there was little understanding as yet of this now manifest truth. One hardly notes a sign of any such awareness in literature and public discussions until the end of the century; and failing a clear understanding of their nature the new expansive forces operated through the cheap and unsound interpretations first of sentimental nationalism and then of romantic imperialism.

Sanderson's boyhood saw the differences of the cultures of north and south in the United States of America at first exacerbated by the new means of communication and then, after four years of civil war, resolved into a stabler unity. The straggling peninsula of Italy under the sway of the new synthetic forces recovered a unity it had lost with the decay of the Roman roads; the internal tension of the continental powers culminated in the Franco-German war. But these were insufficient adjustments, and a renewed growth of armaments upon land and sea alike, betrayed the growing mutual pressure of the great powers. All dreamt of expansion and none of coalescence. The dominant political fact in Europe while Sanderson was a young man, was the rise of Germany to political and economic predominance. German energy, restrained from geographical release, drove upward along the lines of scientific and technical progress, and the outward thrust of its pent-up imperialism took the form of a gathering military threat. Germany first and then the United States, released and renewed after their escape from the fragmentation that had threatened them, made the economic pace for the rest of the world throughout the eighties and the nineties. They stirred the British manufacturer and parent to indignant inquiries; they forced the drowsy schools of Great Britain into a reluctant admission of scientific and technical teaching. But they awakened as yet no profounder heart-searchings.

The young science-master at Dulwich talked, no doubt, as we all did in those days, of Evolution and Socialism, of the rights of labour and the Christianisation of industry, of the progress of science and the scandal of the increasing expenditure upon armaments, with the illusion of an immense general stability in the background of his mind. It was an illusion that needed not only the Great War of 1914-18 but its illuminating sequelae to shatter and destroy.

Accounts of Sanderson's work in Dulwich school differ very widely. At one time it would seem that he had troubles about discipline, and it is quite conceivable that his methods there were experimental and fluctuating. No doubt he was trying over at Dulwich many of the things that were to establish his success at Oundle. On the whole the Dulwich work was good work, and it gave him sufficient reputation to secure the headmastership of Oundle School when presently the governing body of that school sought a man of energy and character to modernise it.

The most valuable result of his Dulwich period was the demonstration of the interestingness of practical work in physical science for boys who remained apathetic under the infliction of the stereotyped classical curriculum. He was not getting the pick of the boys there but the residue, but he was getting an alertness and interest out of this second-grade material that surprised even himself. The interest of the classical teaching was largely the interest of a spirited competition which demanded not only a special sort of literary ability but a special sort of competitive disposition. But there are quite clever boys of an amiable type to whom competition does not appeal, and some of these were among the most interesting of the youngsters who were awakened to industrious work by his laboratory instruction.

It is clear that before Sanderson went to Oundle he had already developed a firm faith in the possibility of a school with a new and more varied curriculum, in which a far greater proportion of the boys could be interested in their work than was the case in the contemporary classical and (formal) mathematical school, and also that he had conceived the idea of replacing the competitive motive, which had ruled the schools of Europe since the establishment of the great Jesuit schools three hundred years before, by the more vital stimulus of interest in the work itself. He also took to Oundle a proved and tested conception of the need for the utmost possible personal participation by every boy in every collective function of the school. Quite early in his Oundle career he came into conflict with his boys and carried his point upon the issue whether every boy was to sing in the school singing or whether that was to be left to the specialised choir of boys who had voices and a taste for that sort of thing. That was an essential issue for him. From the very first he was working for the rank and file and against the star system of school work by which a few boys sing or work or play with distinction and encouragement, against a background of neglected shirkers and defeated and discouraged competitors.

Sanderson married soon after he went to Dulwich. His wife came from Cumberland and she excelled in all those domestic matters that make a successful headmaster's wife. Throughout all the rest of his life she was his loyal and passionate partisan. His friends were her friends, and his critics and opponents were her enemies, and if she had a fault it was that she found it difficult to forgive anyone who had seemed ever to differ from him. Two sons were born during the seven years that passed in the little home in Dulwich. It must have been a very brisk and happy little home. One can imagine the tall young man with his gown a little powdered with blackboard chalk, flying out behind him, striding along the school corridors to some fresh and successful experiment in laboratory work, or in homely tweeds walking along the Kentish lanes with his friend, or snatching a delightful half-hour in the nursery to see Master Roy's first attempts to walk, or reading some new and stirring book with the lamp of those days before electric lighting at his elbow. He was thirty-five when he achieved his last step in the upward career of a secondary schoolmaster and was appointed headmaster of Oundle. That success probably came as a surprise, for Sanderson's modest origins and the fact that he was not in holy orders must have been a serious handicap upon his application. It must have been a very elated young couple who packed their household belongings for the unknown town of Oundle.

Oundle School, which was to be the material of Sanderson's life work, which was to teach him so much and profit so richly by the reaction, was one of comparatively old standing. It was a pre-reformation foundation; a certain Joan Wyatt having endowed a schoolmaster in the place in 1485. Its main revenues, however, derived from Sir William Laxton, Lord Mayor of London and Master of the Grocers' Company, who in 1556 left considerable property to that body on condition that it supported a school in his native town of Oundle. The Grocers' Company took over the Joan Wyatt school and schoolmaster, and has discharged its obligations to Oundle with intermittent energy and honesty to this day.

Oundle has always been a school of fluctuating fortunes. The district round and about does not sustain a sufficient population to maintain full classes and an efficient staff, and only when the prestige of the school was great enough to attract boys from a distance had it any chance of flourishing. Time after time an energetic head with more or less support from the distant governing body would push it into prominence and prosperity only to pass away and leave it to an equally rapid decline. The London Grocers' Company is a very unsuitable body for educational work. It is not organised for any such work. It was originally a chartered association of city wholesalers, spice dealers, and so forth, who maintained a certain standard of honest trading and protected their common interests in the middle ages; it commended itself to the spiritual care of St. Anthony, and built a great hall and acted as almoner for its impoverished members and their widows and orphans; its normal function to-day is the entertainment of princes and politicians. It is now a fortuitous collection of merchants, business-men, and prosperous persons, and it is only by chance that now and then a group of its members have had the conscience and intelligence to rise above the normal indifference of such people to the full possibilities of the Laxton bequest. Generally the Company's conduct of the school has varied between half-hearted help and negligence and the diversion of the funds to other ends; it has no tradition of competent governorship, and the ups and downs of Oundle have been dependent mainly upon the personal qualities of the masters who have chanced to be appointed.

There was a period of prosperity during the second quarter of the seventeenth century which was brought to an end by the plague, and by the impoverishment of the school through the fire of London in which various Laxton properties were destroyed. Throughout a large part of the eighteenth century the school was completely effaced, and the entire revenues of the Laxton bequest were no doubt expended in hospitality. There was a revival in 1796. In the seventies of the nineteenth century the school was doing well in mathematics under a certain Dr. Stansbury, and in the eighties it had as many as two hundred boys under the Rev. H. St. J. Reade. Then it declined again until the numbers sank below a hundred. It was a time of quickened consciences in educational matters, and some of the more energetic and able members of the Grocers' Company determined to make a drastic change of conditions at Oundle. They found Sanderson ready to their hands.

The world is changing so rapidly that it may be well to say a few words about the type of school Sanderson was destined to renovate. Even in the seventies and eighties these smaller 'classical' schools had a quaint old-fashioned air amidst the surrounding landscape. They were staffed by the less vigorous men of the university-scholar type; men of the poorer educated classes in origin, not able enough to secure any of the prizes reserved for university successes, and not courageous enough to strike out into the great world on their own account. They protected themselves from the sense of inferiority by an exaggeration of the value of the schooling and disciplines through which they had gone, and they ignored their lack of grasp in a worship of the petty accuracies within their capacity. Their ambition soared at its highest to holy orders and a headmastership, a comfortable house, a competent wife, dignity, security, ease, and a certain celebrity in equation-dodging or the imitation of Latin and Greek compositions. Contemporary life and thought these worthy dominies regarded with a lofty scorn. The formal mathematical work, it is true, was not older than a century or a century and a half, but the classical training had come down in an unbroken tradition from the seventeenth century. One of the staff of Oundle when Sanderson took it over is described as a 'wonderful' classical master. 'His master passion,' we are told, 'for Latin elegiacs and Greek iambics fired many of his pupils, whose best efforts were copied into a book that bore the title _Inscribatur.'_ These exercises in stereotyped expression were going on at Oundle right into the eighteen-nineties. They had their justification. From the school the boys passed on to the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, where sympathetic examining authorities awarded the greater prizes at their disposal to the more proficient of these victims. The Civil Service Commissioners by a mark-rigging system that would have won the respect of an American election boss, kept the Higher Division of the Civil Service as a preserve for ignorance 'classically' adorned. So that the school could boast of 'an almost uninterrupted stream of scholarship successes at Cambridge' even in its decline in the late eighties, when its real educational value to the country it served was a negative quantity.

This seventeenth century 'classical' grind constituted the main work of the school, and no other subject seems to have been pursued with any industry. Most of the staff could not draw or use their hands properly; like most secondary teachers of that time they were innocent of educational science, and no attempt was made to teach every boy to draw. Drawing was still regarded as a 'gift' in those days. The normally intelligent boy without the peculiar aptitudes and plasticity needed to take Latin elegiacs seriously, had no educational alternative whatever. There was no mathematical teaching beyond low-grade formal stuff of a very boring sort, and the only science available was a sort of science teaching put in to silence the complaints of progressive-minded parents rather than with any educational intention, science teaching that was very properly called 'stinks.' It was a stinking imposture. The boy of good ordinary quality was driven therefore to games or 'hobbies' or mischief as an outlet for his energies, as chance might determine. The school buildings before Sanderson was appointed were as cramped as the curriculum; old boys recall the 'redolent' afternoon class-rooms; the Grocers' Company in its wisdom had built a new Schoolhouse during the brief boom under St. John Reade, between a public house on either side and a slum at the back. It must have been pleasant for master and boys alike to escape from the stuffiness of general teaching upon these premises, and from the priggish exploits in versification of the 'inspired' minority, to the cricket field. There one had scope; there was life. The Rev. H. St. J. Reade, the headmaster in the eighties, had been Captain of the Oxford Eleven, and drove the ball hard and far, to the admiration of all beholders.

The Rev. Mungo J. Park, who immediately preceded Sanderson, is described as a man of considerable personal dignity, aloof and leisurely, and greatly respected by the boys. Under him the number of the boys in the school declined to fewer than a hundred. That dwindling band led the normal life of boys at any small public school in England. Most of them were frightfully bored by the teaching of the bored masters; the wonderful classical master lashed himself periodically up to the infectious level of enthusiasm for his amazing exercises; there was cribbing and ragging and loafing, festering curiosities and emotional experimenting, and, thank Heaven! games a fellow could understand. If these boys learnt anything of the marvellous new vision of the world that modern science was unfolding, they learnt it by their own private reading and against the wishes of their antiquated teachers. They learnt nothing in school of the outlook of contemporary affairs, nothing of contemporary human work, nothing of the social and economic system in which many of them were presently to play the part of captains. If they learnt anything about their bodies it was secretly, furtively, and dirtily. The gentlemen in holy orders upon the staff, and the sermons in the Oundle parish church, had made souls incredible. There has been much criticism of the devotion to games in these dens of mental dinginess, but games were the only honest and conclusive exercises to be found in them. From the sunshine and reality of the swimming-pool, the boats, the cricket or football field, the boys came back into the ill-ventilated class-rooms to pretend, or not even to pretend, an interest in languages not merely dead, but now, through a process of derivation and imitation from one generation to another, excessively decayed. The memory of school taken into after life from these establishments was a memory of going from games and sunshine and living interest into class-rooms of twilight, bad air, and sham enthusiasm for exhausted things.

Sanderson made his application 'for the headmastership of Oundle at an unusually favourable time. There were several men of exceptional enlightenment and intelligence upon the governing body of the school, and they were resolved to modernise Oundle thoroughly and well. To the innovators the very unorthodoxy of Sanderson's upbringing and qualifications was a recommendation, to their opponents they made him a shocking candidate, and the Grocers' Company was rent in twain over his application. It requires a little effort nowadays for us to understand just how undesirable a candidate this spectacled young man from Dulwich must have appeared to many of the older and riper 'grocers.'

In the first place he was not in holy orders, and it was a fixed belief of many people—in spite of the fact that few of the clerically-ruled English public schools of that time could be described as hotbeds of chastity—that only clergymen in holy orders could maintain a satisfactory moral and religious tone. On the other hand, he had been a distinguished theological student. That, however, might involve heresy; English people have an instinctive perception of the corrosive effect of knowledge and intelligence upon sound dogma. Then he was not a public-school boy, and this might involve a loss of social atmosphere more important even than religion or morals. The almost natural grace of deportment that has endeared the English traveller and the English official to the foreigner, and particularly to the subject-races throughout the world, might fail under his direction. Moreover, he was no cricketer. He had no athletic distinction; a terrible come-down after the Rev. H. St. J. Reade. These were all grave considerations in those days. Against them weighed the growing dread of German efficiency that was already spreading a wholesome modesty throughout the commercial world of Britain. This young man from Dulwich might bring to Oundle, it was thought, the base but valuable gifts of technical science. And there was apparent in him a liveliness and energy uncommon among scholastic applicants. His seemed to be a bracing personality, and Oundle was in serious need of a bracing regime. The members who liked him liked him warmly, and he roused prejudices as warm; feeling seems to have run high at the decision, and he was appointed by a majority of one.

The little world of Oundle heard of the new appointment with mixed and various feelings, in which there was no doubt a considerable amount of resentment. No man becomes headmaster of an established school without facing many difficulties. If he is promoted from among the staff of his predecessor old disputes and rivalries are apt to take on an exaggerated importance, and if he comes in from outside he finds a staff disposed to a meticulous defence of established usage. And the young couple from Dulwich came to the place in direct condemnation of its current condition and its best traditions. There can be no doubt that at the outset the school and town bristled defensively and unpleasantly to the newcomers.

In one respect the old educational order had a great advantage over the new that Sanderson was to inaugurate. It had a completed tradition, and it provided the standards by which the new was tried. Whatever it taught was held to be necessary to education, and all that it did not know was not knowledge. By such tests the equipment of Sanderson was exhibited as both defective and superfluous. Moreover, the new system was confessedly undeveloped and experimental. It could not be denied that Sanderson might be making blunders, and that he might have to retrace his steps. People had been teaching the classics for three centuries; the routine had become so mechanical that it was done best by men who were intellectually and morally half asleep. It led to nothing; except in very exceptional cases it did not even lead to a competent use of either the Latin or Greek languages; it involved no intelligent realisation of history, it detached the idea of philosophy from current life, and it produced the dreariest artistic Philistinism, but there was a universal persuasion that in some mystical way it _educated._ The methods of teaching science, on the other hand, were still in the experimental stage, and had still to convince the world that even at the lowest levels of failure they constituted a highly beneficent discipline.

I do not propose to disentangle here the story of Sanderson's first seven years of difficulty. He found the school and the town sullen and hostile, and he was young, eager, and irascible. The older boys had all been promoted upon classical qualifications, they were saturated with the old public-school tradition that Sanderson had come to destroy, and behind them were various members of a hostile and resentful staff inciting them to obstruction and mischief. Neither Mr. nor Mrs. Sanderson was old enough or wise enough to disregard slights or to ignore mere gestures of hostility.

Reminiscences of old boys in the official life give us glimpses of the way in which the old order fought against the new. Everything was done to emphasise the fact that Sanderson was 'no gentleman,' 'no sportsman,' 'no cricketer,' 'no scholar.' It is the dearest delusion of snobs everywhere that able men who have made their way in the world are incapable of acquiring a valet's knowledge of what is correct in dress and deportment, and the dark legend was spread that he wore a flannel shirt with a sort of false front called a 'dicky' and detachable cuffs, in place of the evening shirt of the genteel. Moreover, his dress tie was reported to be a made-up tie. Unless he is to undress in public I do not see how a man under suspicion is to rebut such sinister scandals. The boys, with the help and encouragement of several members of the staff, made up a satirical play full of the puns and classical tags and ancient venerable turns of humour usual in such compositions, against this Barbarian invader and his new laboratories. It was the mock trial of an incendiary found trying to burn down the new laboratories. It was 'full of envenomed and insulting references' to all the new headmaster was supposed to hold dear. Finally it was rehearsed before him. He sat brooding over it thoughtfully, as shaft after shaft was launched against him. 'It didn't seem so funny then,' said my informant, 'as it had done when we prepared it.' It went to a 'ragged and unconvinced applause.' At the end 'came a pause—a stillness that could be felt.' The headmaster sat with downcast face, thinking.

I suppose he was chiefly busy reckoning how soon he would be rid of this hostile generation of elder boys. They had to go. It was a pity, but nothing was to be done with them. The school had to grow out of them, as it had to grow out of its disloyal staff.

He rose slowly in his seat. 'Boys, we will regard this as the final performance,' he said, and departed thoughtfully, making no further comment. He took no action in the matter, attempted neither reproof nor punishment. He dropped the matter with a magnificent contempt. And, says the old boy who tells the story, from that time the spirit of the school seemed to change in his favour. The old order had discharged its venom. The boys began to real ise the true value of the forces of spite and indolent obstructiveness with which their youth was in alliance.

Not always did Sanderson carry things off with an equal dignity. His temperament was choleric, and ever and again his smouldering indignation at the obstinate folly and jealousy that hampered his work blazed out violently. Dignified silence is impossible as a permanent pose for a teacher whose duty is to express and direct. Sanderson's business was to get ideas into resisting heads; he was not a born orator but a confused, abundant speaker, and he had to scold, to thrust strange sayings at them, to force their inattention, to beat down an answering ridicule. He was often simply and sincerely wrathful with them, and in his early years he thrashed a great deal. He thrashed hard and clumsily in a white-heat of passion—'a hail of swishing strokes that seemed almost to envelop one.' A newspaper or copybook at the normal centre of infliction availed but little. Cuts fell everywhere on back or legs or fingers. He had been sorely tried, he had been overtried. It was a sort of heartbreak of blows.

The boys argued mightily about these unorthodox swishings. It was all a part of Sanderson being a strange creature and not in the tradition. It was lucky no one was ever injured. But they found something in their own unregenerate natures that made them understand and sympathise with this eager, thwarted stranger and his thunderstorms of anger. Generally he was a genial person, and that, too, they recognised. It is manifest quite early in the story that Sanderson interested his boys as his predecessor had never done. They discussed his motives, his strange sayings, his peculiar locutions with accumulating curiosity. Two sorts of schoolmasters boys respect: those who are completely dignified and opaque to them, and those who are transparent enough to show honesty at the core. Sanderson was transparently honest. If he was not pompously dignified he was also extraordinarily free from vanity; and if he thrust work and toil upon his boys it was at any rate not to spare himself that he did so. And he won them also by his wonderful teaching. In the early days he did a lot of the science teaching himself; later on the school grew too big for him to do any of this. All the old boys I have been able to consult agree that his class instruction was magnificent.

Every year in the history of Sanderson's headmastership shows a growing understanding between the boys and himself. 'Beans,' they called him, but every year it was less and less necessary to 'Give 'm Beans,' as the vulgar say. The tale of storms and thrashings dwindles until it vanishes from the story. In the last decade of his rule there was hardly any corporal punishment at all. The whole school as time went on grew into a humorous affectionate appreciation of his genius. It was a sunny, humorous school when I knew it; there was little harshness and no dark corners. No boy had been expelled for a long time.

The official life gives a diagram and particulars of the growth of the school during Sanderson's time, and there is no need to repeat those particulars here. From 1892 to 1900 there was no very remarkable increase in the number of boys; it rose from ninety-odd to a hundred and twenty or so. Then as Sanderson's grip became sure there followed a rapid expansion.

From 1900 onwards Oundle grew about as fast as it was possible to grow. New laboratories were built, new subjects introduced so as to furnish a wider and wider variety of courses to meet such intellectual types as the school had hitherto failed to interest. There was a great development of biological and agricultural work from about 1909 onward. The attention given to art increased, and there was a great change and revolution in the history teaching. By 1920 the numbers of the school were soaring up towards six hundred. He wanted them to go to eight hundred, because he still wanted to increase the variety of courses, and the larger numbers gave a better prospect of classifying out the boys effectively and making I sure that each course of studies was sufficiently attended to keep it active and efficient.

The prestige of the school grew even more rapidly than its size. From 1905 onward the inquiring parent who wanted something more than school games and _esprit de corps_ was sure to hear of Oundle.

And Sanderson was growing with his school. Every installment of success stimulated him to new experiments and fresh innovations. No one learnt so muc h at Oundle as he did, and it is with that growth of his conception of school method and his widening vision of the schoolmaster's role_ _in the world that we must now proceed to deal.

When Sanderson first came to Oundle his ideas seem to have differed from the normal scholastic opinion of his time mainly in his conviction of the interestingness and attractiveness of real scientific work for many types of boys that the established classical and stylistic mathematical teaching failed to grip. He developed these new aspects of school work, and his earliest success lay in the fact that he got a higher percentage of boys interested and active in school work than was usual elsewhere, and that the report of this and the report of his wholesome and stimulating personality spread into the world of anxious parents. But it early became evident to him that the new subjects necessitated methods of handling in vivid contrast to the methods stereotyped for the classical and mathematical courses.

There have been three chief phases in the history of educational method in the last five centuries, the phase of compulsion, the phase of competition, and the phase of natural interest. They overlap and mingle. Medieval teaching being largely in the hands of celibates, who had acquired no natural understanding of children and young people, and who found them extremely irritating, irksome, or exciting, was stupid and brutal in the extreme. Young people were driven along a straight and narrow road to a sort of prison of dusty knowledge by teachers almost as distressed as themselves. The medieval school went on to the chant of rote-learning with an accompaniment of blows, insults, and degradations of the dunce-cap type. The Jesuit schools, to which the British public schools owe so much, sought a human motive in vanity and competition; they turned to rewards, distinctions, and competitions. Sir Francis Bacon recommended them justly as the model schools of his time. The class-list with its pitiless relegation of two-thirds of the class to self-conscious mediocrity and dufferdom was the symbol of this second, slightly more enlightened phase. The school of the rod gave place to the school of the class-list. An aristocracy of leading boys made the pace and the rest of the school found its compensation in games or misbehaviour. So long as the sole subjects of instruction remained two dead languages and formal mathematics, subjects essentially unappetising to sanely constituted boys, there was little prospect of getting school method beyond this point.

By the end of the eighteenth century schoolmasters were beginning to realise what most mothers know by instinct, that there is in all young people a curiosity, a drive to know, an impulse to learn, that is available for educational ends, and has still to be properly exploited for educational ends. It is not within our present scope to discuss Pestalozzi, Froebel, and the other great pioneers in this third phase of education. Nearly all children can be keenly interested in some subject, and there are some subjects that appeal to nearly all children. Directly you cease to insist upon a particular type of achievement in a particular line of attainment, directly your school gets out of the narrow lane and moves across open pasture, it goes forward of its own accord. The class-list and the rod, so necessary in the dusty fury of the lane, cease to be necessary. In the effective realisation of this Sanderson was a leader.

For a time he let the classical and literary work of the school run on upon the old competition compulsion, class-list lines. For some years he does not seem to have realised the possibility of changes in these fields. But from the first in his mechanical teaching and very 'soon in ma thematics the work ceased to have the form of a line of boys all racing to acquire an identical parcel of knowledge, and took on the form more and more of clusters of boys surrounding an attractive problem. There grew up out of the school Science a periodic display, the Science Conversazione, in which groups of youngsters displayed experiments and collections they had co-operated to produce. Later on a Junior Conversazione developed. These conversaziones show the Oundle spirit in its most typical expression. Sanderson derived much from the zeal and interest these groups of boys displayed. He realised how much finer and how much more fruitful was the mutual stimulation of a common end than the vulgar effort for a class place. The clever boy under a class-list system loves the shirker and the dullard who make the running easy, but a group of boys working for a common end display little patience with shirking. The stimulus is much more intimate, and it grows. Jones minor is told to play up, exactly as he is told to play up in the playing field.

In the summer term the conversazione in its fully developed form took up a large part of the energy of the school. Says the official life:

'All the senior boys in the school were eligible for this work, the only qualification necessary being a willingness to work and to sacrifice some, at least, of one's free time. There was never any dearth of willing workers, the total number often exceeding two hundred. The chief divisions of the conversazione were: Physics and Mechanics; Chemistry; Biology; anti Workshops. A boy who volunteered to help was left free to choose which branch he would adopt. Having chosen, he gave his name to the master in charge; if he had any particular experiment in view, he mentioned it, and if suitable, it was allotted to him. If he had no suggestion, an experiment was suggested, and he was told where information could be obtained. As a general rule two or three boys worked together at anyone experiment.

'Some of the experiments chosen required weeks of preparation; there was apparatus to be made and fitted up, information to be sought and absorbed, so that on the final day an intelligent account could be given to any visitor watching the experiment. This work was all done out of school hours. Four or five days before Speech Day, ordinary school lessons ceased for those taking part in the conversazione; the laboratories, class-rooms, and workshops were portioned out so that each boy knew exactly where he was to work, and how much space he had. The setting up of the experiments began. To anyone visiting the school on these particular days it must have seemed in a state of utter confusion, boys wandering about in all directions apparently under no supervision, and often to all appearances with no purpose. A party might be met with a jam-jar and fishing-net near the river; others might be found miles away on bicycles, going to a place where some particular flower might be found. Three or four boys would appear to be smashing up an engine and scattering its parts in all directions, while others could be seen wheeling a barrow-load of bricks or trying to mix a hod of mortar. Gradually a certain amount of order appeared, some experiments were tried and found to work satisfactorily, others failed, and investigation into the cause of failure had to be carried out. As the final day approached excitement increased, frantic telegrams were sent to know, for example, if the liquid air had been despatched, frequent visits to the railway-station were made in the hopes of finding some parcel had arrived; sometimes it was even necessary to motor to Peterborough to pick up material which otherwise would arrive too late. A programme giving a short description of the experiment or exhibit had to pass through the printer's hands. At last everything would be ready; occasionally, but very seldom, an experiment had to be abandoned or another substituted at the last moment.'

The year 1905 marked a phase in the co-operative system of work on the mechanical side with the machining and erection of a six-horse-power reversing engine, designed for a marine engine of 3500 horse-power. Castings and drawings were supplied by the North Eastern Marine Engineering Works. The engine was a triumphant success, and thereafter a number of engines has been built by groups of boys. Concurrently with this steady replacement of the instructional-exercise system by the group-activity system, the mathematical work became less and less a series of exercises in style and more and more an attack upon problems needing solution in the workshops and laboratories, with the solution as the real incentive to the work. These dips into practical application gave a great stimulus to the formal mathematical teaching, for the boys realised as they could never have done otherwise the value of such work as a 'tool-sharpening' exercise of ultimately real value.

Quite early in his Oundle days Sanderson displayed his disposition towards collective as against solitary activity in his dealings with the school music. When he came to the school the 'musical' boys were segregated from the non-musical in a choir; the rest listened in conscious exclusion and inferiority. But from the outset he set himself to make the whole school sing and attend to music. The few boys with bad ears were carried along with the general flood; the discord they made was lost in the mass effect. Towards the end a very great proportion of the boys were keen listeners to and acute critics of music. They would crowd into the Great Hall on Sunday evenings to listen to the organ recital with which that day usually concluded.

Presently Sanderson began to apply the lessons he had learnt from grouping boys for scientific work to literature and history. Most of us can still recall the extraordinary dreariness of school literature teaching; the lesson that was a third-rate lecture, the note-taking, the rehearsal of silly opinions about books unread and authors unknown, the horrible annotated editions, the still more horrible text-books of literature. Sanderson set himself to sweep all this away. A play, he held, was primarily to be played, and the way to know and understand it was to play it. The boys must be cast for parts and learn about the other characters in relation to the one they had taken. Questions of language and syntax, questions of interpretation, could be dealt with best in relation to the production. But most classes had far too many boys to be treated as a single theatrical company, so small groups of boys were cast for each part. There would be three or four Othellos, three or four Desdemonas or Iagos. They would act their parts simultaneously or successively. The thing might or might not ripen into a chosen cast giving a costume performance in public. The important thing is that the boys were brought into the most active contact possible with the reality of the work they studied. The groups discussed stage 'business' and gesture and the precise stress to lay on this or that phrase. The master stood like a producer in the auditorium of the Great Hall. Let anyone compare the vitality of that sort of thing with the ordinary lesson from an annotated text-book.

The group system was extended with increasing effectiveness into more and more of the literary and historical work. Here the School Library took the place of the laboratory and was indeed as necessary to the effective development of the group method. The official life of Sanderson gives a typical scheme of operations pursued in the case of a form studying the period 1783-1905. The subject was first divided up into parts, such as the state of affairs preceding the French Revolution; the French Revolution in relation to England; the industrial system and economic problems generally; and so on. The form divided up into groups and each group selected a part or a section of a part for its study. The objective of each group was the preparation of a report, illustrated by maps, schedules, and so forth, upon the section it had studied. After a preliminary survey of the whole field under the direction of a master, each boy followed up the particular matter assigned to him by individual reading for a term, supplemented when necessary by consultation with the master. Then came the preparation of maps and other material, the assembling of illuminating quotations from the books studied, the drafting of the group's report, the discussion of the report. In some cases where the group was in disagreement there would be a minority report.

In this way there was scarcely a boy in the form who did not feel himself contributing and necessary to the general result, and who was not called upon not merely by his master but by his colleagues, for some special exertion. It might be thought that the departmentalising of the subject among groups would mean that the knowledge would accumulate in pockets, but this was not the case. Boys of separate groups talked with one another of their work and found a lively interest in their different points of view. It is rare that boys who have received the same lesson can find much in it to talk about, unless it is a comparison of who has retained most, but a boy who has been preparing maps of the Napoleonic military campaigns may find the liveliest interest in another who has been following the history of the same period from the point of view of sea power. There was indeed a very considerable amount of interchange, and when it came to facing external examiners and testing the general knowledge attained, the Oundle boys were found to compare favourably with boys who had been drummed in troops through complete histories of the chosen period.

This group system of work had arisen naturally out of the conditions of the new laboratory teaching, and it had been developed for the sake of its educational effectiveness; but as it grew it became more and more evident to Sanderson that its effects went far beyond mere intellectual attainment. It marked a profound change in the spirit of the school. It was not only that the spirit of co-operation had come in. That had already been present on the cricket and football fields. But the boys were working to make something or to state something and not to gain something. It was the spirit of creation that now pervaded the school.

And he perceived, too, that the boys he would now be sending out into the world must needs carry that creative spirit with them and play a very different part from the ambitious star boys who went on from a training under the older methods. They would play an as yet incalculable part in redeeming the world from the wild orgy of competition that was now afflicting it. In one of his very characteristic sermons he gave his ripened conception of this side of his work. He had been speaking, perhaps with a certain idealisation, of the old craftsmen's guilds—with a glance or so at the Grocers' Company. The school, he declared, was to be no longer an arena but a guild. For what was a guild?

'A community of co-workers and no competition, that was its idea. It is all based on the system of apprenticeships and co-workers. The apprentices helped the masters in every way they could; even the masters were grouped together for mutual assistance and were called assistants. The Company was a mystery or guild of craftsmen and dealers, and their aim was to produce good craftsmen and good dealers.

'To-day, in these days of renascence, we return to the aim and methods of the guilds. Boys are to be apprentices and master-workers and co-workers. In a community this needs must be. We are called to a definite work, all who are privileged to attend here, staff and boys alike—the work of infusing life into the boys committed to our care. Nor can anyone stand out of this and seek work elsewhere. Nemesis sets in for all who try to live for themselves alone. They may try to work—but their work is sterile. The community calls for the energies and activities of all. We are beginning to learn something of what this means. It does not mean an abandonment of the best methods of the past. But it does mean that we have to concern ourselves with the pressing needs and problems of to-day, and join in the work. I do not dwell on this now. My mind goes off to the possible effect of these ideas on the general life of the school.

'The working of these ideas is well seen already in the outdoor life of the school. We see it when houses are getting their teams together to join a competition for a shield, say. We see the mutual help, the voluntary practice, the consultations of the captain with others. We see it in the work in the Cadet Corps. We see it in the preparation for a play—this time, the _Midsummer Night's Dream._ We see it in the new work in the library, and we see it as clearly as in anything in the preparation for a conversazione. No more valuable training can be given than this last-well worth all the many kinds of sacrifice it entails. From it, at any rate, the spirit of competition is, I think, altogether removed. Boys, we believe, set forth to do their work as well as they possibly can—but not to beat one another...I dwell upon these things because we hope that all boys will become workers at last, with interest and zeal, in some part of the field of creation and inquiry, which is the true life of the world. It is from such workers, investigators, searchers, the soul of the nation is drawn. We will first of all transform the life of the school, then the boys, grown into men—and girls from their schools grown into women—whom their schools have enlisted into this service, will transform the life of the nation and of the whole world.'

In the previous chapter I have told how Sanderson was taught by his laboratories and library the possibility of a new type of school with a new spirit, and how he grew to realise that an organisation of such new schools, a multiplication of Oundles, must necessarily produce a new spirit in social and industrial life. Concurrently with that, the obvious implications of applied science were also directing his mind to the close reaction between schools and the organisation of the economic life of the community.

It is amusing to reflect that Sanderson probably owed his appointment at Oundle to the simple desire of various members of the Grocers' Company for a good school of technical science. They did not want any change in themselves, they did not want any change in the world nor in the methods of trading and employment, but they did want to see their sons and directors and managers equipped with the sharper, more modern edge of a technical scientific training. Germany had frightened them. If this new training could be technical without science and modern without liberality, so much the better. So the business man brought his ideas to bear upon Oundle, to produce quite beyond his expectation a counter-offensive of the school upon business organisation and methods. Oundle built its engines, organised itself as an efficient munitions factory during the war, made useful chemical inquiries, extended its work into agriculture, analysed soils and manures for the farmers of its district, ran a farm and did much able competent technical work, but it also set itself to find out what were the aims and processes of business and what were the reactions of these processes upon the life of the community. From the laboratory a boy would go to a careful examination of labour conditions under the light of Ruskin's _Unto This Last;_ he was brought to a balanced and discriminating attitude towards strikes and lock-outs; he was constantly reminded that the end of industry is not profits but life a more abundant life for men.

As one reads through the sermons and addresses that are given in _Sanderson of Oundle_ one finds a steadily growing consciousness of the fact that there was a considerable and increasing proportion of Oundle boys destined to become masters, managers, and leaders in industrial and business life, and with that growing consciousness there is a growing determination that the school work they do shall be something very far beyond the acquisition of money-getting dodges and devices and commercialised views of science. More and more does he see the school not as a training ground of smart men for the world that is, but as a preliminary working model of the world that is to be.

Two quotations from two of Sanderson's sermons will serve to mark how vigorously he is tugging back the English schools from the gentlemanly aloofness of scholarship and school-games to a real relationship to the current disorder of life, and how high he meant to carry them to dominance over that disorder.

The first extract is from a sermon on Faraday. Under Sanderson, it has been remarked, Faraday ousted St. Anthony from being the patron saint of Oundle School. 'With what abundant prodigality,' Sanderson exclaims, 'has Nature given up of her secrets since his day!'

'A hundred years ago Man and Nature as we think of them to-day were unexplored by science; to-day a new world, a new creation. Industrial life has developed, machinery, discoveries, inventions—steam engine, gas engine, dynamo—electrical machinery, telegraphy, radioactive bodies, tremendous openings out of chemistry, biology, economics, ethics. All new. These are Thy works, O God, and tell of Thee. Not now only may we search for Thy Presence in the places where Thou wert wont in days of old to come to man. Not there only. Not only now in the stars of heaven; or by the seashore, or in the waters of the river, or of the springs; among the trees, the flowers, the corn and wine, on the mountain or in the plain; not now only dost Thou come to man in Thy works of art, in music, in literature; but Thou, O God, dost reveal Thyself in all the multitude of Thy works; in the workshop, the factory, the mine, the laboratory, in industrial life. No symbolism here, but the Divine God. A new Muse is here:

'Mightier than Egypt's tombs, Fairer than Grecia's, Roma's temples. Prouder than Milan's statued, spired cathedral, More picturesque than Rhenish castle-keeps, We plan even now to raise, beyond them all, Thy great cathedral, sacred industry, no tomb—A keep for Life.'

'And the builders, a mighty host of men: Homeric heroes, fighting against a foe, and yet not a foe, but an invisible, impalpable thing wherein the combatant is the shadow of the assailant.

'Mighty men of science and mighty deeds. A Newton who binds the universe together in uniform law; Lagrange, Laplace, Leibnitz with their wondrous mathematical harmonies; Coulomb measuring out electricity; Oversted with the brilliant flash of insight "that the electric conflict acts in a revolving manner"; Faraday, Ohm, Ampere, Joule, Maxwell, Hertz, Rontgen; and in another branch of science, Cavendish, Davy, Dalton, Dewar; and in another, Darwin, Mendel, Pasteur, Lister, Sir Ronald Ross. All these and many others, and some whose names have no memorial, form a great host of heroes, an army of soldiers—fit companions of those of whom the poets have sung; all, we may be sure, living daily in the presence of God, bending like the reed before His will; fit companions of the knights of old of whom the poets sing, fit companions of the men whose names are renowned in history, fit companions of the great statesmen and warriors whose names resound through the world.

'There is the great Newton at the head of this list comparing himself to a child playing on the seashore gathering pebbles, whilst he could see with prophetic vision the immense ocean of truth yet unexplored before him. At the end is the discoverer Sir Ronald Ross, who had gone out to India in the medical service of the Army, and employed his leisure in investigating the ravishing diseases which had laid India low and stemmed its development. In twenty years of labour he discovers how malaria is transmitted and brings the disease wi thin the hold of man.'

The second is from a sermon called 'The Garden of Life.'

'As Canon Driver says, "Man is not made simply to enjoy life; his end is not pleasure; nor are the things he has to do necessarily to give pleasure or lead to what men call happiness." This is not the biological purpose of man. His purpose or instinctive end is to develop the capacities of the garden in the wilderness of nature; to adapt it to his own ends, i.e. to the ends of the races of men. Or, as we would now say, his aim is to take his part in the making of his kind; and he is to "keep it," or guard it—i.e. he is to conquer the jungle in it, to prevent it from roving wild again, from reverting to the jungle, from losing law and order, from becoming unruly and disorderly, from breaking loose and running amok. He is to bring and maintain order out of the tangle of things, he is to diagnose diseases; he is to co-ordinate the forces of nature; he is above all things to reveal the spirit of God in all the works of God.

'And in all this we read the duty and service of schools. The business of schools is through and by the use of a common service to get at the true spiritual nature of the ordinary things we have to deal with. The spirit of the true active life does not come to us _only_ in those experiences we have been so accustomed to think of as beautiful and revealing. The active spirit of life is not revealed simply by the arts-the beautiful arts as they may be thought-of music or painting, or literature. These indeed may be only and abundantly _material,_ and the eye and ear may be blind and deaf to the active, creative, discovering, revealing spirit. "Painting, or art generally, as such," says Ruskin in his _Modern Painters,_ "with all its technicalities, difficulties, executive skills, pleasant and agreeable sensations, and its particular ends, is nothing but an expressive language, invaluable if we know it as we might know it as the vehicle of thought, but by itself nothing." He who has learnt what is commonly considered as the whole art of painting, that is the art of representing any natural object faithfully, has as yet only learnt the language by which his thoughts are to be expressed. One language or mode of expression may be more difficult than another; but it is not by the mode of representing and saying, but by the greatness, the awakening, the transmuting and transfiguring conception and knowledge of the thought presented, that the gift cometh, that man is created. Awkward, discordant, stammering attempts may be the burning message of a new hope. But this "voice" of art is too often drowned. It is drowned by executive skill—as is the history of all art-when this skill stretches itself to present things that are static, motionless, dead...

'It is especially our duty to reveal the spirit of God in the things of science and of the practical life. Herein lies a new revelation, a new language, a direct symbolism. Science, just like art and music, can be materialistic—science can aim only at mechanical advancement and worldly wealth, which is not wealth at all—just as art can aim only at pleasure, desire, and drawing-room appreciation. But this need not be so. Certainly no one in a responsible position can teach science for long without the coming of the revelation of a new voice, a new method of expression, a new art—revealing quite changed standards of value, quite new significances of what we speak of as culture, beauty, love, justice. A new voice speaks to the souls of men and women calling for a new age with all its altered relationships and adventures of life.

'With eyes opened to this new art you can wander through the science block and find in it all a new Bible, a new book of Genesis. So we believe. This is our duty and our faith. Into this Paradise have you been placed to dress it and to keep it.'

Let me turn from these two passages of talk to his boys—they are rescued from a mass of pencil notes in his study—to a passage from an address delivered in the Great Hall in Leeds in 1920. It shows very plainly the quality of his conception of what I have called the return of schools to reality.

'Schools should be miniature copies of the world. We often find that methods adopted in school are just the methods we should like applied in the state. We should, in fact, direct school life so that the spirit of it may be the spirit which will tend to alleviate social and industrial conditions. I will give an example of the kind of influence the ideals and methods of a school can exert upon the working life. I will take a condition of labour which is now recognised as probably the greatest of tragedies. It is the slow decay of the faculties of crowds of men and women, caused by the nature of their employment—the tragedy of the unstretched faculties. So common is it, and ordinary, that we pass it by on one side; but no one can go into a factory without seeing workers engaged in work which is far below their capacities. Decay sets in, and the death of talent and enthusiasm, the inspirer of creative work. A little thought will convince us that the process of decay of such a delicate and vital organism as the brain is bound to set up violent, destructive, anarchic forces which go on for several years. A recent writer in the _Times Educational Supplement_ (and this paper cannot be called revolutionary) says that the tragedy of undeveloped talent is being seen more and more to be a gigantic waste of potentiality and an unpardonable cruelty. It is a tragic disease and produces in early life startling intellectual and moral disturbances, which are the natural sources of unrest. As years go on a mental stupor sets in, and there is peace, but peace on a low plane of life. The loss to the community by this waste is colossal, and it is not too much to say that the output of man could be multiplied beyond conception.

'Schools should send boys out into the industrial world whose aim should be to study these tragedies, and by experiments, by new inventions, by organisation, try, we may hope, by some of their own school experience, to alleviate the disease. To my mind this is the supreme aim of schools in the new era.'