Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

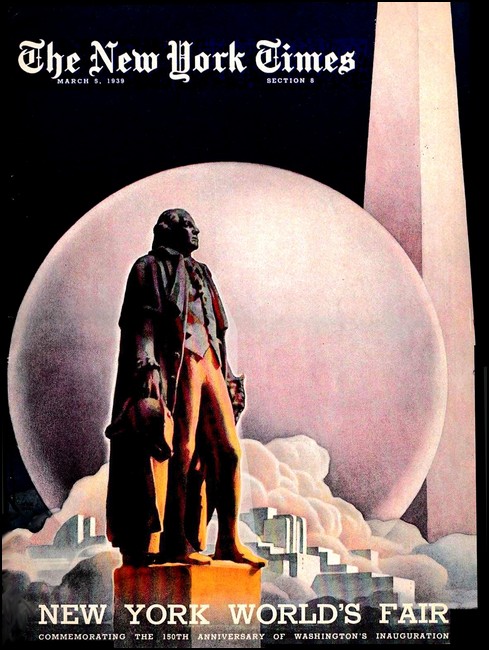

New York World's Fair, 5 March 1939, with "World of Tomorrow"

ON 5 March 1939 The New York Times commemorated the 150th anniversary of George Washington's inauguration as President of the United States of America with a lavishly-illustrated 72-page supplement devoted to the New York World's Fair.

In keeping with the Fair's slogan "The Dawn of a New Day" the supplement offered a collection of articles about various aspects of Man's future socio-economic, industrial, scientific and cultural development.

In the lead article—"World of Tomorrow"—H.G. Wells predicts several developments, some of which (e.g., tele- conferencing and the increasingly systematic organization of human knowledge) have since become reality.

The contents of the NYT supplement were presented as follows:

The present RGL e-book was built from digital image files of Wells' lead article donated by Art Lotrie.

—Roy Glashan, 8 October 2021

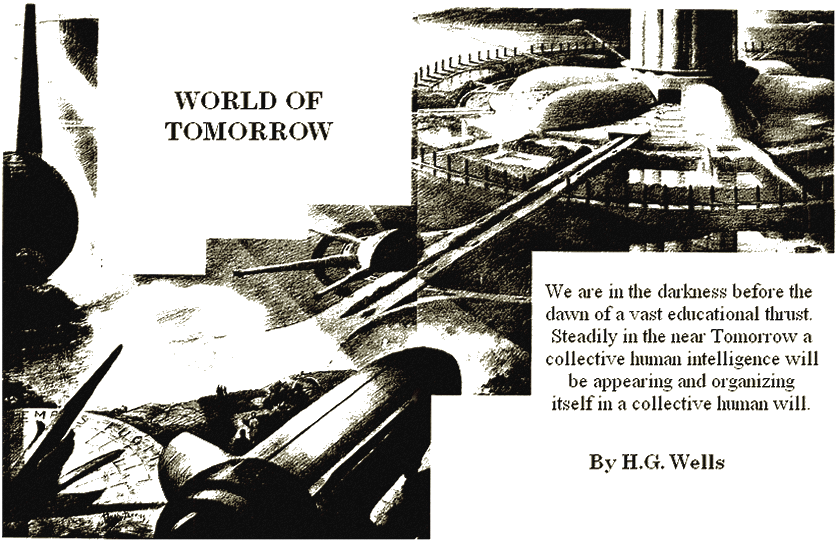

We are in the darkness before the dawn of a vast educational thrust. Steadily in the near Tomorrow a collective human intelligence will be appearing and organizing itself in a collective human will.

THE World's Fair in New York is to differ from most World Fairs in being a forward-looking display. Its keynotes are not history and glory but practical anticipation and hope. It is to present the World of Tomorrow. It is arranged not indeed as the visible rendering of a Utopian dream—there is to be nothing dreamlike about it—but to assemble before us what can be done with human life today and what we shall almost certainty be able to do with it, if we think fit, in the near future. It is, to go back to the original meaning of the word, a prospectus, the prospectus of tomorrow. It is a promotion show.

Long ago in London—it was somewhen in the middle Eighties when I was a student at the Royal College of Science—there was an Inventors Exhibition conceived in much the same spirit. There we had our imaginations stimulated by the sight of horseless carriages, mostly driven by steam or oil; arc lights spluttering in a sort of purple indignation, of photographs of a white horse in motion taken so swiftly that they could be put into a sort of zoetrope and you could to see the creature galloping again.

There we had plain hints of the motor cars, electric lighting and movies of today. We knew, we students, of the Hertzian waves, but I do not remember any intimations of radio. And not a hint then of an airplane.

When, in 1900, I wrote that a plane would fly before 1950 I was considered extravagant indeed. "Imaginative," I was called, which still in England is a way of calling a man a silly fool.

We are living today in the tomorrow of that exhibition, and the amount of change in the interval gives us some justification for a certain boldness in our interpretation of the present World's Fair in New York.

I do not think it is necessary to be very political in such a speculation. We may end with political consequences, but we need not begin with political assumptions. Wars may come and wars may cease, liberty may wax and wane, populations may be enslaved or liberated; these are indeed matters of primary importance to human life and happiness, but I do not think they are going to affect the general drift of the material circumstances of mankind.

THESE latter seem to follow a logical process of their own;

one thing leads to another. Nothing is in sight that will stanch

the flow of invention and very little to stay innovation. The

trend of mechanical invention and enterprise is likely to be much

the same, a little faster or a little slower, cramped or happy,

whatever dictators or financial adventurers or patriotisms or

fananticisms may prevail. The ways in which the suburbs of Kansas

City, Berlin, Moscow and London grow follow parallel lines. The

radios, the garages, the cinemas spread with a recognizable

similarity; all the world wears the same rouge and dances to the

same tunes.

FROM first to last the outward framework of behavior at least

is conditioned by this well-nigh invincible drive in material

affairs. Some of these outward forms as they change will carry

with them changes at a deeper level, but that is another

matter.

So the visitor who wants to get the most out of this World's Fair will do best to regard it not as a show of things but as a collection of hints and let his imagination off the leash of discretion for a bit, directly it shows the least disposition to start up some entertaining quarry. Then he may really get a glimpse of the realities of tomorrow that lurk in this jungle of exhibits. It will cease to look like a collection of things for sale and reveal its real nature as a gathering of live objects, each of which is going to do something to him, possibly something quite startling, before he is very much older.

THE possibility I find nearest at hand and likely to strike

us most vividly, if we could be transferred to a not-very-distant

tomorrow to see it realized, is an immense change in the

landscape of city and country alike.

In the first place, the new methods of communication and transport that are still increasing in speed, precision and safety have scarcely begun to produce their inevitable effects upon the distribution of population. It seems that the concentration of a majority of humanity in towns and cities is now no longer necessary, and, if it is now simply a traditional gregariousness that makes the townsmen bunch together, it is quite probable that presently there may be so rapid a dispersal that the difference of town and country will vanish altogether.

[Those of us who experienced the] evacuation of London during the war panic of September, 1938, will realize how the menaces of modern warfare may accelerate that process. Many people have been jumping to the conclusion that modern war may drive cities underground; they have not sufficiently considered the possibility of its dispersing them altogether.

EVEN the existence of business centers is no longer

imperative. It is so close a Tomorrow that it is almost Today

when it will be possible for a dozen men or a score of men to sit

in conference, seeing and hearing each other, by radio,

television, telephone, when bodily they are hundreds of miles

apart. All that this exhibition of the World's Fair will show

plainly.

This is a hard staying for New York, the largest, intensest wen of humanity in existence, that already it has nearly outlived the forces that gathered it together. Yet that is so plainly the case that even in a score of years or so New York may be scattered to the four quarters of the earth.

And how scattered? In such buildings as we know today? I doubt if they will be anything like the buildings we know today. For the next series of building possibilities that the World's Fair will assemble will be a dazzling array of absolutely new materials to replace the brick, stone, timber and iron of our fathers. We have Henry Ford building motor cars out of soy bean products now and half the gadgets in a modern home are made of stuffs unheard of in 1900. At present only the gadgets. But the rest of our dwelling places will follow. In some fashion. Who can imagine the forms these new substances will take?

In these matters our reasoning can go far beyond [this. The] new building materials have their own esthetic possibilities that it will need millions of artistic minds to reveal. At present the new materials ape the forms of the old or else affect a gawky plainness. Only by trial and error in the world of feeling can mankind grope its way, one artist following another, to the new loveliness that has become possible.

We can reason out to a certain extent what the men and women of tomorrow will be free to do, but we cannot guess what they will decide to do. Will they even want to live in definite places when they can live anywhere; and if they do not remain in "settlements" is it a world of hostels that is ahead of us or a world of caravan cars, or shall we have portable homes—glorified tabernacles?

POSSIBLY we shall have all these and a number of other

arrangements. The likelihood is of an extraordinarily varied

landscape replacing the homely pattern of town and villages, town

and villages, city, town and villages to which this generation is

still attuned. Travel will certainly become much more exciting

when every place will be different, with a character of its own.

Maybe people's lives will fall into phases. They will settle down

in a temperate climate for a time to have children and see them

through their early years. Home will he a family nest—and

it will come to an end when the last chick has flown.

When I was young I used to think of old people going home to some "Haven of Rest." I doubt that now. I find myself at 72 with far more wanderlust than I had forty years ago, and I perceive that most of my elder contemporaries wind up their careers with a tour round the globe. So long as it is reasonably comfortable the old are as eager for travel as any one.

The World of Tomorrow will certainly be a world intercommunicating and aware, to a relatively immense extent.

ANOTHER germ that the World's Fair will set before us, for

our imaginations to incubate, is the steady progress being made

in indexing and documenting knowledge, storing facts, theories

and representations in colored micro-films, and making this

methodical accumulation more ana more generally accessible. Out

of this growing movement there is bound to grow a synthesis, a

summary, which will form the basis of factual instruction in all

schools throughout the world.

Today none of us knows a tithe of the things that are known; we do not even know about them, not so much because they are too many and too much for us as because they are so badly presented to us in our schools and records, so tumultuously and so confusingly, and with such imperfect means of verification, that we cannot make anything like the best possible use of them. The wisest of us are stuffed with mere bits and clots and jumbles or ill-adjusted knowledge, and it is not too much to anticipate a far clearer-headed common man in this diversified town-countryside about the world, to which the World's Fair points us.

It is not necessary to suppose any improvement in [the] human faculty to anticipate that. We merely suppose a better exploitation of our mental stuff in school, college and encyclopedia.

City of Tomorrow

Designed by Norman Bel Geddes

for the General Motors exhibit

OF course, all over the world, whether people are living in home-automobiles or cottages (with every convenience) or some modernized sort of tents or palatial apartment houses or hotels, there will have to be stores for the swift distribution of goods—whether they are privately owned or publicly owned is really a secondary matter—and everywhere there will be eating places.

I am very doubtful if these various sorts of human shelter and residences that impend will include many private dining rooms Will there be universal good cooking then, or is my Utopian streak running away with me?

This is the physical direction in which we arc going, wars or no wars, whether we have democratic socialism, totalitarianism or financial rule. I am less inclined to foretell a twilight of civilization, new Dark Ages, than I used to be. We are possibly in the darker phase of the modern Dark Ages now or just on the verge of that umbra. Human institutions and human thought are being subjected to an enormous strain in their adjustment to the vaster scale of possibility that has challenged them. Social biology and in particular social psychology have lagged a century or more behind physical science, but now they are hurrying.

WE are only beginning to realize the correlations that have

to be observed in our developments. The popular motor car, for

instance, was launched upon roads entirely unprepared for it, and

the vast slaughter that has ensued is very largely due to that.

We still resist the abolition of administrative boundaries that

should manifestly follow the abolition of distance. We fail to

stand up to the fact that patriotism should be now almost as

obsolete as the honor tradition of the duel and the vendetta. We

boggle at the cost and effort of that universal education which

alone can save political life from mass hysteria, gangster

exploitation and war.

But the consequent disasters, frightful as they are, are not overwhelming disasters, and there is no perceptible ebb of vitality in the confused torrent of events. The common human pride and conscience have been profoundly shocked by the black horror produced by race mania, nationalism, economic dogmatism and financial dislocation in recent years.

In these years hundreds of thousands, millions perhaps, of people have thought intensely about the human problem and realized political and social truths to which they were totally indifferent before. They realize they must know more and know better.

We are in the darkness before the dawn of a vast educational thrust. Steadily in the near Tomorrow a collective human intelligence will be appearing and organizing itself in a collective human will.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.