RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

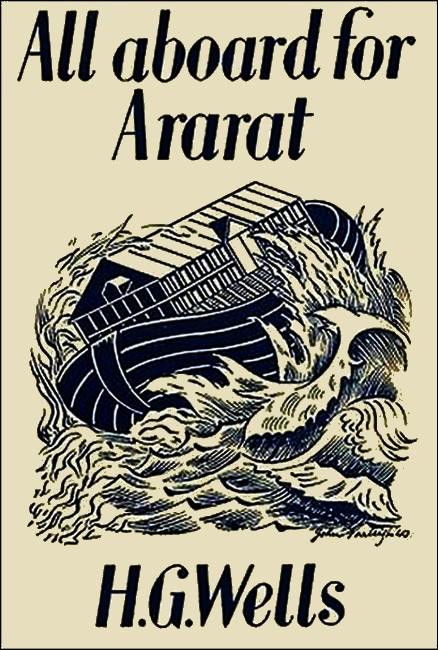

All Aboard for Ararat," Secker & Warburg, London, 1940

All Aboard for Ararat," Alliance Book Corporation, New York, 1941

All Aboard for Ararat is a 1940 allegorical novella by H. G. Wells that tells a modernized version of the story of Noah and the Flood. Wells was 74 when it was published, and it is the last of his utopian writings.

GOD ALMIGHTY pays a visit to Noah Lammock, a well-known author whom the outbreak of war has convinced that "madness had taken complete possession of the earth." At first God is thought to be a mental patient from a nearby asylum, but his dignified air earns him a reception in the writer's study. God explains that he has been "surprised" and "disappointed" by humanity, and tells Noah Lammock: "What I propose is that you should construct, with my help and under my instruction, an Ark."

Lammock is intrigued, but first, since God tells him that the Bible is "wonderfully trustworthy" and possesses "substantial truth," demands an accounting for his decision to destroy the Tower of Babel. God has already explained that the creation of light entailed as well the creation of "a shadow," and "since I had come into our Universe as a Person, it is evident that my shadow also had to be a Person." Now God explains that he and Satan panicked at the prospect of "Man keeping together on the plain of Shinar in one world state, working together, building up and up," and "together . . . acted in such haste that frankly the covenant with Noah and all that was completely overlooked." God is repentant, however, and tells Lammock that still wants to "bring Adam into free, expanding fellowship with myself—that old original idea." Lammock takes pity, in part because he notices the deity is "quivering on the very verge of non-existence."

God returns to Noah Lammock a week later, and, after some literary chit-chat that reveals that God is under the misapprehension that Noah Lammock is the author of The Time Machine, The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind, and World Brain , the two discuss the plan for the Ark. God is enthused about the potential of microphotography , having met Kenneth Mees , but Lammock demands to know: are they to "reinstate or do we start afresh?" Lammock believes it is necessary "to begin over again," because the "primary danger" to the new world is "that the élite will become a self-conscious, self-protective organisation within the State." "It is a new religion and a new manner of life I am obliged to stand for." "The core of the new world must be (listen to the words!) Atheist, Creative, Psycho-synthetic," he declares, but God can come along as "an inspiring delusion."

Choosing a crew for the Ark is an enormous problem because no one Lammock knows seems to be equal to the task, but before he has resolved it he awakens to discover that he is already in the cabin of the Ark, which is "thirty days out." An excerpt from the ship's log explains that a leak has delayed its landing, and that Jonah , a stowaway, has caused no end of problems. The novella ends inconclusively ("The final pages of this story do not appear to be forthcoming" ) with a further conversation between God and Noah Lammock. They agree that they "will make Ararat," and God says, "On the whole, I am not sorry I created you." As for Noah, he declares: "No man is beaten until he knows and admits he is beaten, and that I will never know nor admit." —Wikipedia

IT seemed beyond dispute to Mr Noah Lammock that madness had taken complete possession of the earth and that everything he valued in human life was being destroyed. Courage, devotion, generosity, still flamed out amidst the tragedy, but they shone only amidst a universal defeat. They were given no chance. They were caught and smashed flat under tanks; they were machine-gunned from the air. It seemed scarcely to matter whether the old governments which sent natural trustful men into warfare, ill-armed and ill-led, and were ready to sell and betray them for a transitory respite, or these new governments of frantic aggression, which loaded poor devils with drugs and thrust them forward by the million to die, for no rational end at all, arrived presently at some show of victory. Nowhere was there any finality. Either way a vista of wars, oppression and degradation opened before mankind.

It had taken a long time before this conviction of a final catastrophe was beaten into Mr. Lammock's brain. His was an energetic and enterprising temperament, and he had lived most of his life in the conviction that a greater world order, a vast New Peace of universal opportunity and fulfilment, was unfolding before mankind.

Now it seemed that Brave New World of his was a distressful, dusty, hopeless refugee, pursued by inevitable death.

Intellectual apprehension had preceded conviction. He had said this collapse of humanity was coming long before he realised it was coming. Now he sat stunned at the truth of his own forecast.

"Men," he said, "have no will whatever beyond the range of their accustomed activities. The idea of a creative world in which man might be master of his fate, has never touched their imaginations. They have had a phase of good fortune and it draws now to its end. They must follow all these other creatures which have rejoiced in the sunshine of the past, the Dinosaurs and the Megatheria and the like, to extinction. Their sun is setting. There is nothing to be done. Only those great beasts did not know, and this time, some of us know. And what is the use of knowing?"

To that he could find no answer. It was no good telling other people, if there was nothing one could tell them to do. Let them live out their little day until the final darkness overtook them. He carried on, with as confident a face as he could contrive, to hide the cold realisation of final defeat that closed about his heart. Maybe the end was coming, but at any rate it had not yet come. There might still be some idea...

But no idea came to him.

He sat at his writing table, writing nothing. He went into his study day by day, and sat there because it seemed to him to be as good a place as anywhere to await the end. He could divert his mind by no minor interest. Sometimes he was in a sort of coma; sometimes he found himself emerging from intricate dreams that evaporated tantalisingly as he awakened.

A visitor was announced, a most unexpected visitor.

"There is a gentleman downstairs," said Mabel the parlour-maid, "and he says he wants to see you personally. Something very private and important."

"Did he give a name?"

"I think, Sir, he must have got out of some place..."

"Yes, yes, but the name?"

"Well, Sir, he says He's God Almighty, Maker of Heaven and Earth."

"Surely he exaggerates."

"It is what he said, Sir."

Mr. Lammock reflected. "Got a beard?"

"Quite a long one, Sir."

"Blue eyes?"

"Sort of glaring."

"Ah! How far's the nearest asylum?"

"I can look it up, Sir."

"Well, do so. Ask them if anyone is missing. And ring up Dr Burchett and explain things, get his advice, and say will he come over here if he isn't too busy. And tell the poor creature to wait downstairs—. I have trouble enough to keep my own wits without having to deal with anyone else... Oh!"

They became aware that the visitor was in the room. He had entered unobtrusively and seated himself so noiselessly in the comfortable but upright arm-chair which Mr Lammock reserved for visitors that it was almost as if he had appeared there. He was large and elderly, with a careworn but dignified face. His extremely clean white hair was like wool. It was not true that his eyes glared. That was a touch of Mabel's. He had none of the distraught slovenliness of your common lunatic.

"Noah the son of Lamech, I believe," he said, in a grave, untroubled voice.

"Practically," said Mr Lammock, struck for the first time by the scriptural quality of his surname.

The visitor seemed to weigh his words before he spoke again.

"History, Sir, has a way of repeating itself—with variations. Always with variations. I noted your name in the directory. By accident. It struck me. It impressed me. I made enquiries about you. I have been hoping for a serious talk with you for some time. But I have been detained. Yes, Detained.

...What I have to say is—for a time at least—intimate." He glanced at Mabel. "Confidential."

"You need not wait," said Mr Lammock to Mabel.

The girl hesitated. She was a protective, maternal creature and did not care to leave her fragile, kindly employer with anyone who might behave queerly.

"Don't wait," said Mr Lammock again, and turned eyes of weary interrogation to his visitor.

Mabel, after a swift but effective scrutiny of the Almighty's essentially benevolent profile, decided to risk it. The door closed behind her.

For a brief interval Mr Lammock and his visitor looked each other in the eye.

"It is quite natural for you," said the visitor, "to assume that because I have recently been detained as—as an Incomprehensible, shall we say?—in a private lunatic asylum, I am not God Almighty. Quite natural. It is only gradually that you will realise I am. But you will realise that. I put myself under restraint, I may explain, quite voluntarily. I feel an extreme reluctance to wind up this non-reversible time system altogether, and yet the pass to which things have come again... Sorely tempted..."

He coughed and paused.

"There is a common form of mental disorder," he resumed; "especially among young men, called 'Tying Up'. You may have heard of it. They tie themselves up and often they are found hung or throttled or otherwise dead—by their own contrivance. I have done something of the same sort—on a much larger scale. I have tied myself up in this non-reversible universe of ours. I could end it all in an instant. Indeed, I repeat, I have been sorely tempted..."

"To destroy the whole thing?"

"Myself and everything. So far as I exist in time and space I am a part of this process. But I am essential to the process. I am its underlying First Cause. I have been called the 'Great, First Cause', but that 'Great' is a vulgarity. There is only one First Cause, myself. I'm afraid that brain of yours is not particularly adapted to what I might call supermetaphysics. So I won't explain. But if I decide to end, then I end, and you and everything end with me.

"Quite painless. It's gone. So".

"Then why don't you end it?" asked Noah.

"I did end it and myself—just then. And now I've come back again and brought you all with me where we left off."

"I noted nothing," said Noah.

"Naturally."

"But it's all going on again. Why don't you end it for good and all? I would."

"Because I don't like being beaten. Because directly one gets going in a time-space system one doesn't like being beaten. You don't."

"I am very nearly beaten," said Mr Lammock. "I was sitting here, dead at heart already..."

He looked up, surprised at the things he was saying. What was he saying? He stared at the calm intelligence of his visitor's face.

Suddenly the conviction came to him that beyond all question this refined, white-headed gentleman was God Almighty even as he claimed to be. Exactly as the Bible presented him. Mr Lammock made one last effort against this conviction. He sought some protective difficulties. There must certainly be difficulties. Ah!

"You say I am Noah the Second and that Lammock is just Lamech over again. That is all very well, Sir.

But—. For instance. There is practically no Mrs Noah, she left me years ago, and so far from having three sons, Shem, Ham and Japhet, I am childless."

"No man who writes with a sincerity as complete as yours, is childless," God remarked gently, and a trifle evasively, and would have dismissed that difficulty.

"But—" carped Mr Lammock.

"Writers, like many other organisms, the teleostean fishes, for example, cast their seed upon the waters," said God, "and it returns to them after many days. You need have no anxiety about that."

"I have not the remotest desire to see my wife again. If you mean that. To have her back in my present distressed state..."

"I will make it my particular business to see that she comes back changed. A helpmeet. Bringing her sheaves with her..."

"You don't mean—?"

"Leave these details to me. For the first time for many centuries I have created angels and sent them off upon my business. To make enquiries. I would prefer not to give you details. I move in a mysterious way and I like to do so. There were difficulties of course..."

Mr Lammock's faith ebbed. This old gentleman was just an escaped lunatic after all, and nothing more. Making angels! For a time Mr Lammock considered he was merely humouring the old fellow until the asylum people arrived. Then by imperceptible degrees his faith returned to him. God took no notice of these fluctuations. He went on with what he had to say.

"When I abandoned myself, when I tied myself up by creating this Universe of ours, I deliberately gave up foresight, that is to say I made an initial proposition, launched it in time, and shut my eyes immediately to its implicit consequences. While I exist I am not omniscient. How can I be? Theologians have been very stupid in declaring I am. Vulgar uncritical glorification! It flies in the face of common sense. Omniscience is a static state. Manifestly when everything is present in your mind, nothing else is left to happen. It is quite incompatible with the idea of a Living God. Life is finite. I wanted response. That is to say I wanted to be surprised. I have been. Surprised and—disappointed.—My original idea was of an immense responsive universe, with a delightful garden at the centre, pervaded by a sort of appreciative exaltation called love. Every creature was to have its reciprocating lover, responding generously. I thought that a particularly charming invention. I created Man. A bachelor at first. The story, I admit, is a little confused. People read their Bibles in such a slovenly fashion. You can hardly call it reading! They bolt the stuff in a state of pious awe. I do so wish they wouldn't. I hate pious people. I hate their abject prayers. Almost always they are mean demands for preferential miracles. Whenever I get a chance, I do them bad turns. I never, if I can help it, answer their prayers. Then they say I am trying them and they crawl more than ever. Where do they get these ideas about me? When have I countenanced any of these verminous saints? Read me. Read my Book. My Bible is fairly plain about it. If only people would read intelligently. The people I favour are upright men who walk with God. It says so over and over again. Not crawlers at his feet. Men who stand up... Or anyhow men who looked like standing up. But never mind that. About this Adam. Male and female created I him, and also he was alone. That is to say he was a properly equipped bachelor. I wanted him to go about the garden world sharing my surprises. He did for a brief period..."

The Deity reflected profoundly.

"But is it true that you created the world, when was it?—4004 B.C.?'

"Certainly. Why not?"

"But—!"

"Please do not say 'But' like that. There is no difficulty about it at all. I tied myself up in a Universe in which things would happen. That is to say there had to be a future. This Universe in which I had to exist as the essential First Cause had to be a going concern. Well, think! A going concern. Directly I and the Universe came into Being and Becoming, in 4004 B.C., at that instant we brought with us, as an essential necessity, an illimitable past. How could it be otherwise? The trees had to have annual rings; the plants bore flower and fruit and seed; Adam had an umbilicus. Implying a mother. Implying a billion ancestors. Have you never read Gosse's Omphalos? How could this Universe go on if it had not been led up to? This was the very first thing I realised about this time and space game. It had to be like that. It could not be otherwise. Or putting it another way, if I and Adam and everything were looking forward, there had to be all this behind us. I perceived a lot of things had to be cleared up, and the first thing I said therefore was 'Let there be Light'. My Bible is perfectly correct about that also. But what it does not make so clear is that immediately there was light, I had a shadow...

He was silent for awhile.

"Always," mused God. "There has been that shadow...

"That," said God, "is what your philosopher Hegel is fumbling about when he says that nothing can exist without its contradiction. And since I had come into our Universe as a Person, it is evident that my shadow also had to be a Person."

A touch of genuine irascibility ruffled the Divine Serenity. "And a damned troublesome person he is, in the fullest sense of the words. The whole story of the Bible from the creation onward is the story of the frustration of all my good-will and generosities towards Adam, by that—. Um."

He paused on the verge of a stormy outbreak. His expression became stern and imminent. There was a sudden clap of thunder and a flash of summer lightning, and the atmosphere grew calm again. "That unpredictable and unspeakable consequence of myself," said God, evidently much relieved.

"Exactly," said Noah.

"That is why I hate to end the whole business until I have fought out this with—my shadow," said God.

"We are in your hands," said Noah.

"There he was always at my elbow with his confounded refrain: 'But if you do this, then it follows—'

"That Happy Pleasure Garden lasted no time. If everything was going on, he said, everything had to go on to something else. You couldn't have repetitions without variations. I had to admit that was sound. 'Fresh every morning is the love,' says one of your hymns. It has to be. All these forward-looking creatures couldn't go on caressing and delighting in each other without some objective. They had to carry on to something new. They had to have expectation and justification. They had to beget.

"I found my Garden was in for procreation before I had time to turn round. 'Love,' said I. 'Then sex,' said my shadow. 'They must grow, produce energy, recuperate, crave and eat.' I made my purring carnivores and hardly had Adam stroked them before they showed their teeth. I went into the garden in the cool of the evening—Those incessantly varying colour effects produced by breaking up the white radiance of eternity, the evening glow and the afterglow and so on, pleased me enormously—and I saw at once that my antagonist had been making mischief. A cat scampered past me with a bird in its mouth. I called for Adam and Eve, the woman I had made him to allay the restlessness of his desires; and out they came from behind some bushes, thoroughly ashamed of themselves, and wearing, of all preposterous things, aprons of fig-leaves!

"That really did make me angry. The bright little world I had made for them was, I saw, spoilt. I could bear with his critical destruction of my own ideas, but I found that going behind my back to them—and that they should be so foolish as to listen to him—exasperating. I had made my prohibition of what he called the Tree of Knowledge, so explicit.

I suppose I should have made an end to the whole thing, to myself and him and everything, there and then. But you see I had tied myself up in it all.

I was a Person up against a Personal opponent. I admit I lost my temper. 'If you must have it so,' I said; 'have it so.' I cursed him up and I cursed him down, I cursed Adam and I cursed Eve, I cursed the earth... I was really upset. Sin and death came into my scheme, and all your woe; no doubt to his great satisfaction.

"When at last I cooled off and began to relent, there was Adam, my poor image and protégé, delving, actually delving, reduced in fact to the status of an ill-trained agricultural labourer, and his wife learning to cook and spin, expecting a child and very much overworked. Their children, naturally enough, were ill brought up and turned out most unsatisfactorily... That was the end of Eden...

"So it went on," said the Creator, beating the arm of his chair reminiscently. "So it has gone on. No sooner do I seem to be getting Adam on his legs again, than over he goes morally and materially like a ninepin. I become less and less of an Almighty Father and more and more like a skittle alley attendant. It is all in my Bible, all of it. I have concealed nothing.

"Taking it by and large," said the Almighty, "that Book of mine is wonderfully trustworthy. You will never get a better universal history. I have written it from time to time and there may be, I admit, trivial inconsistencies. The statistics are loose, very loose; the ages of the earlier patriarchs and so forth are obviously in a muddle. You see, I have always dealt in general ideas, always realised, since every single thing is really unique, the underlying fallacy of counting. I treat figures with a certain off-handedness. And, believe it or not, no proofs of my book were ever sent me for correction. That does not affect the substantial truth of my Word. Not in the least. Nothing else comes anywhere near the facts about mankind. I ask you. You say it is preposterous and then you have to believe it. You perceive the little flaws, you doubt the authenticity of the text, very reasonably. Still the story remains fundamentally convincing. It has been twisted and tampered with. But nothing can destroy it. You see..."

The Divine countenance darkened. There was thunder in the air again. "He got hold of the publishers, translators, critics... Who are, without exception, spawn of the devil. You have written books, Noah. You know. He gets hold of all of them."

"Spawn of the devil; don't I know," said Noah.

"Since I made man in my own image how could I be anything but a very human God? How could I foresee that sort of thing? How could I know how they would humbug me about? From first to last my fault has been trustfulness. I am the Eternal Optimist. People say 'God is Love'. Far truer, that God is Hope."

("But he's charming!" thought Noah. "These theologians with their explanations do nothing but explain him away.")

"Time after time," said God, "I have tried to make a man of Adam. Time after time he has let the devil in his imagination get the better of me. I have experimented in this and that sort of salvation.

...I adopted a Chosen People... I took up with Abram. I enlarged him to Abraham. I was always changing people's names, and I realise now, with all this psychoanalysis and so on, how symptomatic that was. How was I to know the Enemy would get among the genes and produce that—that—well, Jacob?

"I had a gleam of foresight about that. There was something about Isaac I didn't like. He wasn't a patch on the old man. He was a most improbable son for honest Abel. I told this poor old man to sacrifice him and stop it all—and then you know I weakened and let him off. So Isaac lived—to become, in modern terminology, the putative father of two strikingly non-identical twins. You realise how unsuspicious I am. It is only later that I have thought out Madam Rebecca and her double-crossing son. She stole and lied. Well? Why should she have stopped at that?

"You know the tangle the lot of them made of my promise to Abraham. My Bible gives the whole dismal record. Each one of those Patriarchs has a wife, Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, who doesn't at first give him a child until some questionable miracle occurs. Then he finds himself the father of a son who—well—doesn't match. You read it over. It's all in my Book.

"By the time my Promise came to Bethel I was in a complete Maze. I did what I could to keep my word, I confirmed that this Jacob's seed should be as the dust of the earth, and there they are! The Jacobim, the Chosen Race. I was never quite sure. I made him change his name to Israel as a sort of hint... He was no better as Israel. The same mean proclivities... Whether there is a drop of Abraham's blood in any of them is more than I can say. Later on the old man had a very good time with a young woman called Keturah. Now they were nice children; Midian and the rest of them. But the Israelites!... These Chosen People! The time they have given me! I sent them into Captivity. I brought them back again. I sent prophet after prophet to warn them and curse them. It was all no good. Then I tried the Messiah idea. Saul of Tarsus put that askew in a brace of shakes...

"So it has gone on.

"Time after time I have been moved to rub out Adam altogether in some immense, vindictive catastrophe, before sinking back into the mystery beyond being; and time after time I have left the catastrophe incomplete. Someone has attracted me. Or something has restrained me. It has seemed to me that at last at the eleventh hour I had found a really upright man who could not fail me. Now, I thought, we shan't be long. I have said 'Let there be one more New Deal.' Just one more. Why not? I did that with your prototype Noah the son of Lamech. I propose to do it with you. I was going to rain destruction upon the whole breed of Homo sapiens, I was going to flood and stifle the whole earth under a torrent of German mud, blood and Ogpu and have done with it. Then, quite by chance, I am struck by your name..."

"Yes?" said Noah...

"What I propose is that you should construct with my help and under my instruction, an Ark."

Noah was about to speak but the Almighty waved his objection aside. "Details will follow," he said. "What I propose is that with my help and under my instruction you should construct an Ark. An Ark that this time will be a success. Into that Ark we will put reproductive samples of every good thing that is in the world, beasts, birds, arts and crafts, inventions and discoveries, literature. Carefully chosen and carefully vetted. We will save all the living seeds of civilisation for a new sowing. Off we will go. And when this inundation of foul warfare is over and the stench has subsided, the Ark will rest again on another Ararat and out you will come, all of you, to a cleansed, renascent world."

"All of us?"

"You and your seed. You and your family. Your wife whom I have found for you, your sons, Shem, Ham and Japhet, and their wives and little ones. For the strange thing is that, under very slightly different names, practically all the family of your prototype are to be found on earth again. The coincidence is so remarkable, that the temptation to see how far the parallelism will go, is enough in itself to justify—..."

"No," interrupted Noah, with an emphasis that seemed to startle even God himself, "you don't. No!"

"I don't?"

"You don't put that over on me. No! If you bring back that infernal woman, you may count your Ark off. I won't have anything to do with it."

"I never dreamt of this—this dreadful vindictiveness," said God in a subdued voice, after a pause of astonishment "Possibly. But now you do. You know nothing about the real quality of my wife. You seem to know very little about any women, judging by your simplicity about Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel—to mention only three cases of more than doubtful paternity. Your own triplex personality is, I gather, entirely male. Since the Assumption of the Ever-Blessed Virgin matters seem to have mended a little. The old credulity—gone. Of the original Mrs Noah, of course, I have nothing to say. She has remained nameless and blameless down the ages. But my wife was a vain, restless, jealous exhibitionist, a dishonest and consuming woman. She was—temperamental to an extreme degree. She devastated three years of my life with taunts, insults and reproaches. There was no satisfying her and no pacifying her. She went off at last and I was able to divorce her. She made marriage so horrible to me that I have never tempted Fortune again..."

"My messengers tell me she is a lady of considerable intellectual activity. One or two of them speak of her admiringly."

"How can an angel judge? Made to-day as an angel is, and gone to-morrow. She has literary pretensions. I should describe her as a woman of promiscuous pretentiousness. She belongs to literary societies and coteries. She made addresses and uttered exasperating criticisms. She was always discovering young geniuses and behaving ambiguously with them. She called it encouragement. Her attitude to my work was made up of vehement jealousy and a desire to gain credit for it as its virtual inspiration. Phew!"

"If you had had children perhaps," said God.

"We didn't have children. We rapidly developed a temperamental incompatibility. She made an immense fuss about her passionate possibilities... On that side she became disgusting..."

Noah paused. "What is the good of recalling these disagreeable experiences? She did at any rate go. And for the rest of my life she can remain gone."

God reflected upon this angry outburst. For some reason it seemed to confirm rather than weaken his original resolution.

"Apart from that temperamental instability of hers, she was, you admit, a woman of a lively, exceptional intelligence?"

"She had an essentially feminine mind, if you mean that, shallow, quick."

"All this," said God, "increases the parallelism remarkably."

"With the original Noah?"

"With the original Noah."

"But in the Bible—. Mrs Noah never says a word or does a thing."

"The character of the former Mrs Noah," said God, speaking with a judicious slowness and putting the finger-tips of one open hand against the fingertips of the other, "has remained above suspicion for four thousand, two hundred and eighty-nine years, precisely. Yes. In the toy Arks given to children, I observe, she is represented by an extremely upright figure with a conspicuous, serviceable-looking bust and a costume devoid of the slightest hint of feminine coquetry. She wears the sort of hat a charity school girl might wear. Her cheeks display an unmitigated shining glow of health, as though powder was unknown to her—That, I may tell you frankly, does her no sort of justice, either way. My Book states certain facts and makes no comments. The Patriarchs and Prophets were sufficiently scandalous to supply whatever human interest was needed without putting in superfluous gossip. Still Mrs Noah... I thought you understood. If only people would read my Book intelligently—"

"Every author feels that," said Noah. "But go on. Tell me about the original Mrs Noah.

"I gave certain facts about this lady. They seem to me to speak for themselves. Have you never noted their implications? Consider what those facts were.

She had three sons. One was an extremely dark, if not absolutely black, boy, Ham. The other was sallow with dark curly hair and what one calls nowadays an Armenoid profile, Shem. The third, Japhet, was what the Germans would consider a Nordic type, all milk and roses. Samples in fact of the chief varieties of mankind. Now Noah, like yourself, was a quiet, righteous man. He had great gifts, yes—but I put it to you; was he capable of that much versatility?"

"I see your point," said Noah, after a chilling pause. "And I gather that your angels have ascertained that my spouse, so to speak, has obliged me in a roughly parallel fashion?"

"Yes."

"And pursuing a coincidence to the bitter end, you propose that I should allow her to return to me with her little ethnological collection and make her and her brats a central feature in this new Ark scheme. My dear God, you ask too much."

"But you don't understand the lady!"

"I think I completed my studies of her character, years ago."

"She is a very clever woman and, mentally at least, she is devoted to you."

"I don't care. I know that devotion."

"It is remarkable that she has followed your distinguished career with the utmost interest. She reads all your books and makes her children read them."

"She would do."

"Her one desire now, she told my angel, was to return to your side, act as your housekeeper, your kennel-maid, your secretary, your typist, your amanuensis, your exponent."

"I have heard her expound me."

"Where else could you find such wide experience?"

"No," said Noah.

"Still no?" said God. "You harden your heart."

"You yourself have said that when things repeat themselves, they repeat themselves with variations. Well, this is going to be one of the variations. You want me to be upright. Upright I will be. As stiff as a poker. I stand up to you on this. Whatever catastrophe overwhelms the world, I propose it shall overtake Mrs Noah and little black Ham and nosy Shem and Nazi Japhet conclusively. They must all be wiped out. All of them. I will have nothing to do with this Ark project on any other terms."

"But my dear fellow!" protested God.

"I wish," said Noah, with a note of real anger in his voice, "that you at least would read over what you have put in your own Book. You complain that other people disregard it. You have forgotten what you yourself let out."

"And what did I let out?"

Noah spoke slowly with the affected patience of a man dealing with stark unreason.

"Have you forgotten that Noah the son of Lamech took to drink? Have you really forgotten that? After saving the life of the land and mankind, he took to drink. And I ask you, Why should a respectable man, a distinguished man, a man conscious of achievements that were bound to make his fame immortal, like Noah the son of Lamech, why should he take to drink, unless he was thoroughly unhappy and disgusted with his domestic life? Obviously he was. And there he was lying about in a state of disorder! And she? Where was she? Wasn't it at least her business to tuck him up comfortably? Put a rug over him... Evidently she'd gone off again. Along comes grinning little Ham to gloat upon the sight. It's all there in your own Book! And you propose, out of a mere childish love for coincidence, that I—I, Noah Lammock, should go through all that again!... No fear! You just call your ministering angels in again and obliterate them. On those terms this Ark idea is off. Absolutely off. We won't talk about it further."

"I admit I have given you a certain justification—" said God.

"I am only reminding you of your own account of yourself," said Noah. "I am only recalling to you, your own explicit statements and teaching. Do you want me to give you, of all Beings! Bible lessons?"

"This alters the entire outlook."

"It still leaves me interested in this Ark idea."

"But whom then will you take with you?"

"That we have to consider. Let us be clear first of all, whom we will not take. When we get out of our Ark on Ararat this time we certainly won't have any Shem, any Ham or any Japhet; we'll have clearheaded, back-boned, clean-minded people. We won't have any nonsense about the seed of Abraham and the Chosen People. We won't have any Messiahs or Saviours or Leaders to lead them to do what they ought to do of themselves. Let us wipe out all these blunders of yours from the human mind now and for ever. If it is going to be a New Deal, let it be a new deal. That, Sir, is how I see it. I can no other."

"Go on," said God, looking very uncomfortable. "I started this and I agree I have to go through with it. Well?"

"About that Tower of Babel."

"I was afraid you would come to that," said God, almost in a whisper.

"Let us have the exact words," said Noah, and reached out his hand to a finely printed copy of the English Bible, translated out of the original languages by the commandment of King James the First. "Let me see, Genesis—Genesis? Genesis Ten. Or is it Eleven? Here we are! Genesis Ten. M'm," he read for a minute or so and then protested. "The stuff that got into this Word of yours! Troubled people come to this Book of yours for light and comfort in their hours of darkness, and this is what jumps out on them! What do the poor souls make of it? Do they learn it by heart? Do they say it over and over until they go to sleep again? Is it set to music? Listen, God."

He read remorselessly.

"Now these are the generations of the sons of Noah; Shem, Ham and Japhet: and unto them were sons borne after the Flood.

"The sons of Japhet: Gomer, and Magog, and Madai, and Javan, and Tubal, and Meshech, and Tiras. And the sons of Gomer: Ashkenaz, and Riphath, and Togarmah. And the sons of Javan: Elishah, and Tarshish, Kittim, and Dodanim. By these were the Isles of the Gentiles divided in their lands, every one after his tongue: after their families, in their nations.

"And the sons of Ham: Cush, and Mizraim, and Phut, and Canaan. And the sons of Cush: Seba, and Havilah, and Sabtah, and Raamah, and Sabtecha: and the sons of Raamah: Sheba, and Dedan. And Cush begate Nimrod: he began to be a mighty one in the earth. He was a mighty hunter before the Lord: wherefore it is said, Even as Nimrod the mighty hunter before the Lord. And the beginning of his kingdom was Babel, and Erech, and Accad, and Calneh, in the land of Shinar. Out of that land went forth Asshur, and builded Nineveh, and the city Rehoboth, and Calah, and Resen between Nineveh and Calah: the same is a great city. And Mizraim begate Ludim, and Anamim, and Lehabim, and Naphtuhim, and Pathrusim, and Casluhim (out of whom came Philistiim) and Caphtorim.

"And Canaan begate Sidon his first born and Heth, and the Jebusite, and the Emorite, and the Girgasite, and the Hivite, and the Arkite, and the Sinite, and the Arvadite, and the Zemarite, and the Hamathite: and afterward were the families of the Canaanites spread abroad. And the border of the Canaanites, was from Sidon, as thou comest to Gerar, unto Gaza, as thou goest unto Sodoma and Gomorah, and Admah, and Zeboim, even unto Lasha. These are the sons of Ham, after their families, after their tongues, in their countries, and in their nations.

"Unto Shem also the father of all the children of Eber, the brother of Japhet the elder, even to him were children borne. The children of Shem: Elam, and Asshur, and Arphaxad, and Lud, and Aram. And the children of Aram: Uz, and Hul, and Gether, and Mash. And Arphaxad begate Salah, and Salah begate Eber. And unto Eber were borne two sons: the name of one was Peleg, for in his dayes was the earth divided, and his brother's name was Joktan. And Joktan begate Almodad, and Sheleph, and Hazarmaveth, and Jerah, and Hadoram, and Uzal, and Diklah, and Obal, and Abimael, and Sheba, and Ophir, and Havilah, and Jobab: all these were the sons of Joktan. And their dwelling was from Mesha, as thou goest unto Sephar, a mount of the East, These are the sons of Shem, after their families, after their tongues, in their lands after their nations.

"These are the families of the sons of Noah after their generations, in their nations: and by these were the nations divided in the Earth after the Flood."

Noah closed the Book with a slam. "Well, I ask you?"

"You don't think I made all that up out of my own head," said God. "There were old records... Very interesting old records. People like Woolley find quite a lot of confirmation... Possibly there is a certain looseness..."

"About as loose as the figures," said Noah. "At the best it is mere padding. It is like those out-of-date tables of statistics with which they eke out second-rate books on political economics. But never mind about all that. It just caught my eye. It isn't what I want to ask you about now. What I want to know is just exactly what you did at Babel. That, from my point of view, is the queerest incident of the whole recorded story of the dealings of God with man, the greatest of all the Bible enigmas. I gather that my unfortunate prototype was still alive at the time, and saw the whole business. Very distressing indeed it must have been to him, and I haven't the slightest desire to end up my days in any similar fashion. You had made him, you will remember, all sorts of promises, and you had even put it over him that there had never been such things as rainbows before the flood. Really, God, that was a bit thick! Did the sun never shine on a shower until 2349 B.C.? Anyhow you declared that you set your bow in the clouds as a token of your covenant, and you guaranteed him—up to the hilt. You would do this for him and that for him. For a time it worked. Somehow he contrived to hold all this incongruous and multiplying family of his together in a sort of unison, and got them to the plains of Shinar, where they settled down. There they were, all happily and harmoniously building the Tower of Babel together, and then, Sir, for no earthly or heavenly reason, for no offence, before the very eyes of that poor old tippler, old and stricken in years, somewhere about eight hundred years old, I suppose, by that time, who had walked with you, trusted you and obeyed you—. How does it go?"

He read:

"And the Lord came downe to see the city and the tower, which the children of men builded. And the Lord said; Behold the people is one, and they have all one language: and this they begin to doe: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to doe. Goe to, let us go downe, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another's speech. So the Lord scattered them abroad from thence, upon the face of all the earth: and they left off to build the Citie. Therefore is the name of it called Babel, because the Lord did there confound the language of all the earth: and from thence did the Lord scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth..."

"Now before you and I, my dear Almighty, go building Arks and navigating this present great catastrophe together, will you please tell me, why you did that, and what security I have that you will not repeat what was, God or no God, an act of the foulest perfidy? I speak calmly, but I speak sternly. I said 'foulest perfidy' quite deliberately to you. I repeat it. Was ever a decent man let down, as Noah was let down? What became ultimately of that poor old man? Whom you forgot! Did he go off with some spawn of Shem's or Japhet's, an aged, defeated, cheated, drunken, old bore, sitting and mumbling about his great days to the children of—" he turned to the Book and read again—"'Almodad, and Sheleph, and Hazarmaveth, and Jerah, and Hadoram, and Uzal, and Diklah, and Obal, and Abimael, and Sheba, and Ophir, and Havilah, and Jobab:' and so on, while dear little Uz and Mash made faces behind his bent, complaining back? Oh! a worse tragedy than King Lear!... I can't bear to think of it. That was the end of Noah, son of Lamech. By your own showing. Your own Word for it. Possibly you have an explanation. I confess I cannot imagine what that explanation can be.

"You don't keep your Word, God. You make Promises and you don't keep your Promises. The Jews have been dunning you for three thousand years. And take other cases. Take Enoch. You walked with him; you were inseparable from him. You couldn't wait for him to die. You took him. And where is Enoch now? I ask you."

Mr Lammock's visitor remained silent for the greater part of a minute, and Mr Lammock, awaiting the answer he had demanded, observed something about him he had not noticed before, a slight but unmistakable suggestion of transparency. His flesh was assuming a quality of opal or glass in its texture, a jelly-like texture.

"You have an obduracy," said the Deity at last, "and a rudeness. I admit I have always respected upstanding men. I always shall. But you, for some reason, are more refractory than any of the human beings, good or bad, that I ever had to deal with in the good old B.C. days,—before I adopted my policy of isolation. Because, as you know,—and as sceptics are apt to remark—I have been strictly non-interventionist for the past nineteen centuries. There is, I perceived, a hardened quality about your mind. An occidental harshness. There is a perceptible change in the spirit and method of the human intelligence as I find it in you. My—my antagonist warned me to expect something of the sort. He saw this coming. All this modern science... I started this Universe and I have to go through with this Universe; I started this discussion with you and I have to go through with that. I see no reason why I should complain that you are behaving with an assurance I have never encountered before. But I note it... As though the Fear of God was dead... I have brought it on myself... I must answer your question. Let me admit that up to this moment I have never troubled to find out what became of Noah after the dispersal. Never. He died. There must have been some sort of notification. But how and where, and how they disposed of him and whether they buried him or just threw him away, I am quite unable to say.... I left him about, just as I left Enoch about. I suppose Enoch strayed. I suppose he is still straying—somewhere... How should I know?"

"I am sorry to have to press these considerations," said Noah relenting slightly. "I regret the incivility of my words. You see, I want to know just exactly what your covenant amounts to—in view of the fact that you are now proposing one to me."

"Quite reasonable," said the Almighty, after a meditative moment. "Quite clear and reasonable. At any rate I can congratulate myself on one attentive reader. I suppose that not one so-called Bible reader in a million has observed that Noah was still alive at the great dispersal. Much less bothered about him. Due to their practice of reading only so many verses or a chapter at a time—and thinking generally of something else while they do it..."

Noah the Second remained silently expectant.

"I have already had to make one or two points of—what I have called super-metaphysics—clear to you, little points about Being and Becoming. Now I come to another point still more difficult to explain. The deeper one probes into this non-reversible time and space system of ours the more it twists and turns and changes about. Forgive me if I ask you to be very attentive to what I am trying to express. It is something in the nature of what evasive, pious people call a Mystery. It is referred to in my Bible story, but distantly and obscurely. With the best will in the world to tell my story clearly, I had to deal with it ambiguously. You see... I came into Being, as I have explained, and with me appeared the whole time and space system as a going concern. We have been through all that already."

Noah Lammock inclined his head in patient agreement.

"Well, that is, after all, only one superficial paradox about this Existence. There are others that go deeper. There are difficulties behind difficulties. I want nothing, indeed I want nothing, but plain, simple, onward-to-goodness life, but my shadow goes about and gets hold of physicists and psychologists and mathematicians...

"They come along now declaring that Space is finite. Well, I ask you; isn't that plain nonsense? What do they call whatever there is outside Space? This finite Space isn't metaphysics; this is mountebank physics. They declare we live in an Expanding Universe. What does that mean? Expanding into what? They say that the apprehension of Being is a three-dimensional consciousness system falling through a fourth dimension with the velocity of light. And what is worse, he gets them to make experiments to prove it. I don't see and I can't see why there should be any limit to the velocity of anything. But it seems there is. 'Surely,' I say, 'whatever velocity you are travelling at, you can always throw a stone forward? 'No,' he says, 'strangely enough you can't do that. 'Does it matter?' I ask. 'Ultimately it does,' he says. 'Make it a Mystery,' I suggest, 'and have done with it.'

'These men of science, he says, 'won't allow Mysteries. They keep on poking about.'

'You keep on poking about,' I say, 'making trouble. These things have no more to do with human conduct than the watermark in the paper on which my Book is printed has to do with the story it tells.' And now he is bringing up the old trouble again about whether we can wind up mankind, anyhow.

The Almighty brow was knit with intellectual effort.

"Quite early in the history, I must explain, my shadow began to insinuate a doubt whether, by making man in my own image, I had not endowed him with a certain vested interest, so to speak, in our own continuity in the time and space system, whether in fact he might not have acquired a right to be consulted before his account was closed. It might be, Satan suggested, that even if we, both God and Satan, decided to conclude, man, if he was aware of it, might be able to go on of his own free will. Not merely that. He might even have to go on—anyhow. We were not sure. I don't know if this can be made clear to your earth-born mind. You will have noted, for instance, that my Bible tells of the 'tree of knowledge of good and evil' which was in the middle of the garden. It bore the celebrated Forbidden Fruit. All that is plain sailing. But there was also another tree, a Mystical Tree, of whose fruit evidently neither Adam nor Eve was aware, upon which less stress is laid, yet about which both myself and Satan, it is admitted, became extremely perturbed. It is plain that we realised we had to act about it at once after the Fall. 'Lest he put forth his hand and take also of the Tree of Life and eat and live for ever!' Neither of us was disposed to face that possibility. What, I ask you, was that Tree of Life? Which was bothering us? It is never made clear just exactly where this mysterious tree was to be found. It is never made clear because it wasn't clear. We ourselves were a little uncertain. It is not so much as if we thought he would go to some definite place for it, but as though we feared he might happen upon it before we did. If indeed it was actually there at all. We took no risks. We bundled both of these poor first sinners out of the garden, and put Cherubims and a flaming sword to keep them out. Incontinently. While we hunted round. That was how that was."

He stared at Noah.

"You honour me with your confidence," said Noah. "I appreciate the generosity of your admissions."

"One may tire at last of being tied up in a Universe," said God. "If I abdicate—"

"I begin to see. Will you go on explaining, Sir?"

"At the back of our minds there was always this uneasiness about our real ability to stop Adam once we had started him. After all, it was the first Creation I had ever done. And so when we saw Man keeping together on the plain of Shinar in one world state, working together, building up and up, above the level earth, my shadow revived that old lurking fear very vividly. 'We must act, or they will escape us,' he said. Read it there. Yes, this; 'Nothing will be restrained from them which they have imagined to do!'

"We acted together and we acted in such haste that frankly the covenant with Noah and all that was completely overlooked. Completely. I did not go down alone. Read the Book. It says; 'Let us go down'."

He paused and scrutinised Noah's countenance.

"And so for the second time, Oh Jehovah Yea and Nay, you faltered and thought better of it—thought worse of it. I admit I never read any other book that seemed to me as fundamentally true to the realities of life as the Bible, and at the same time I confess I cannot imagine a God more unstable and more human than it shows you to be."

"Of necessity," protested God very earnestly. "Of necessity. You understand nothing if you do not understand that only in this perplexing and slightly paradoxical way could a space-and-time Universe come into being and remain in being. We are both only beginning to realise what implication means. I have already explained that the moment the world was created as a going concern, at that very moment a limitless past had to come into existence. Is it not equally beyond dispute that at that same moment, I brought into being a limitless future? Manifestly. And afterwards one couldn't uncreate that. Or if one did it didn't matter in the least. I created the world in 4004 B.C.; I swear I did; I uncreated it here in this room only a little while ago. You never noticed it. It made no difference to the everlasting sequence of the Universe. It is like dealing with an interminable history in an interminable book. You may open the book anywhere; or close it anywhere. The history goes on in spite of you. And so it is that the story still unfolds and still I want to be in it, and still I want to struggle with my own shadow and bring Adam into free, expanding fellowship with myself—that old original idea."

Silence.

"Or why should I have come to you?"

"That is all very well," said Noah Lammock. "But can you be of any real help to us now in this endless Universe you have thrust upon us? You are the Creator, you are the Sole First Cause; you account for everything perfectly, as nothing else could do; I do not see how we could possibly have come into existence without you; but now we do exist and are fairly launched, what good have your subsequent interventions been? The end of your Bible, forgive me, twaddles down to nothing. It fades out, as you are fading out. Nothing can exceed the emptiness of the three Epistles of St John and the Epistle of St Jude. Greetings to the brethren, and the writer will come along presently and tell them all sorts of important things. And none of that telling is ever reported! And is there any need for me to speculate about the state of mind that produced that Revelation at Patmos? And then for eighteen centuries and a half we hear no more of you. Until you come to me and suggest building a new Ark. The Earth is full of your Churches and missionaries, I admit; they pray to you and sing to you; but where have you been? Many a Catholic will tell you in all good faith that the Church and the Mass are far more vital to religion than you and your old Book. A good Jesuit fears neither God nor Devil. But he serves the Church. As you grow attenuated and impalpable, as we see through you more and more, your shadow also will grow less. As God fades out, the Devil fades also. Even now you seem quivering on the very verge of non-existence."

"Yes," said the Almighty, not without a touch of malice; "and man as he grows clearer and firmer, discovers that he too casts a shadow."

"There is something in that," said Noah.

"There is everything in that. It is quite possible that Satan and I have played our part in the human drama. I may have become a mere phantom of my former self. That means only that the struggle between benevolence and corrosive resistance, between the light and the shadow it casts, embodies itself anew—in Adam, in Man himself, in you and your kind. The old story repeats itself with this fundamental variation. And for all you may say in your resentment, I did come to you just now when you were very near defeat. I did come to you with an inspiring idea. It stirred you to opposition and criticism, but it won you. And now that this idea of an Ark has taken possession of you, is it wise to reject me altogether? Be considerate. Let me have a voice in planning the Ark. Let us build it together."

"I am to forgive you the desertion of Babel? Those final tragic years?"

"Forgive me everything. Forget everything but the lessons you have learnt through me. Let men unite again. There shall be no second dispersal of mankind. Let us set ourselves honestly to the only brave thing in life, which is beginning again."

Noah remained obdurately silent.

"You may do without God or Devil presently, but can you do so yet? Consider one thing. It is hard to imagine right off, what an Ark of Escape from this inundation of war and violence may mean, but it may involve at some time an appeal to the common multitude. Don't go on arguing what I am or have been in reality, consider what I am now in men's imaginations, consider my—my publicity value. A great majority of mankind has heard of the Lord God—Almighty, the Heavenly Father, the Eternal Friend, but who has heard of Mr Noah Lammock and his modern ideas? And whatever I was and whatever I did, I don't mean any of that to these people. They don't bring up the Old Testament against me as you do. They don't believe it, not as much as you do, not nearly as much as you do. It passes over their minds like a fairy tale or a nursery rhyme. They don't believe that the whale swallowed Jonah any more than they believe that the Dish ran away with the Spoon, yet all the same they believe in a Heavenly Will for Goodness, and it is a great inspiration for them. Under the New Dispensation, for nineteen centuries, I have turned a new face of my triplex personality to mankind. They have read into me all their own growing realisation of goodness and justice. But it is into me they have read it. To thousands of upright men my Name has been an abiding fastness. By virtue of it they have held out against the corruptions, perversions and persecutions of their own religious teachers. I may have been an excuse for priestcraft and tyranny, but also I have sustained the prophets and reformers... Don't turn me down altogether yet..."

"You needn't quiver quite so uncertainly," said Mr Noah Lammock; "it bothers my eyes. I admit I have been extremely ungracious to you. But I wanted to get things perfectly hard and clear in my own mind. Let us both pull ourselves together. What is the real nature of this world-wide human relapse? What is the real significance of this stupendous inundation of force and cruelty? What are the necessary conditions of this Ark we have to set about building? That may perhaps take us at last, by way of Ararat, to Shinar again and so to mankind reunited in one brotherhood, growing in strength and power for ever..."

MR NOAH LAMMOCK awoke from a profound, refreshing sleep. He was in his bed and his room was full of sunlight.

Only the faintest memory of a dream hung about him. Someone had said "Every day the world begins." He could not recall who said it, but he found it a very sustaining statement to wake upon.

He could not remember going to bed. Then he began to recollect the visit of a queer old gentleman with a vast shock of white hair, who was suffering from a delusion that he was God Almighty.

He took his watch from the night table beside him and found it was half-past two. He touched the bell.

"You've slept three quarters round the clock, Sir, and I hope you're feeling better," said Mabel. "I've brought you a cup of tea. Would you like to get up, Sir, or just stay in bed for a bit?"

"I'll get up," said Mr Lammock. "But first tell me what happened. I don't remember coming to bed."

"Dr Burchett and the two gentlemen from the asylum put you to bed. There was no awakening you."

"Yes, but how was that?"

"He put you to sleep. The old gentleman who said he was God Almighty. He came downstairs, quiet and self-possessed like, and he said 'I've put him to sleep. He needs it,' he said. 'He has been dreadfully worried by things and a good long sleep will do him good.'"

"He said that."

"He said it, so that one didn't doubt him for a moment. It was almost as though he was a doctor or a hypnotist or something. And he stood looking out at the garden. 'I love the cool of the evening,' he said."

"Well?"

"Well then, we saw the automobile coming up the drive with Dr Burchett and the two asylum gentlemen."

"Yes?"

"You see he was sort of standing behind me on the doorstep. I was by the door. I'd been watering those seedlings in the little bed. Naturally I looked up to see them getting out of the car. 'I don't think,' I heard him say, close behind me. 'I don't think.' Like that. Then I noticed that they didn't seem to be looking at him; they were all looking at me. 'Where is he?' they said.

"I didn't understand all at once. It seemed such a silly thing to ask. So I didn't turn round for a moment. When I did, I was so taken aback, I couldn't utter a word. He wasn't there! It was as if he'd vanished.

"'Can't you answer, girl?' said Dr Burchett, just like that. 'Where is he?'

"'He was here not a minute ago,' I says. 'At this very door.'

"They didn't say another word. They came right in. They looked behind the door both sides. They looked behind the umbrella stand. One of them peeped into the cloakroom and the other went into the little parlour. He wasn't there. They never found a trace of him, much less got him. Then they turned to me. 'He was here five minutes ago,' I says. 'And a nicer, quieter, better-behaved lunatic I never set eyes on. You'll find the master upstairs—asleep, he says.' One of them went out into the back to have a look up the garden, the other went downstairs to the kitchen and I followed Dr Burchett upstairs.

"I knew somehow you hadn't come to any harm, and there sure enough you was, in your big study chair, looking ten years younger than I've seen you lately, Sir, if you'll permit me to say so, and sleeping as sweet and deep as a baby. Dr Burchett, he felt your forehead and pulse and bent down and took a good smell at your breath. 'Just a natural sleep,' he says. Wake you we couldn't, and, as I said to them, was there any need to try? And they couldn't find him anywhere. Not a trace. And as far as I know, they haven't caught him yet. I hope they won't. Harmless he is, with a sort of face that has known trouble. I don't see any sense in putting him into an asylum if he doesn't feel like being put. There's plenty running about the world, madder than him."

"How long was he talking to me before he came down?"

"Nournarf perhaps. I didn't listen but I hung about in case, and most of the time you was talking low and easy—"

Mr Lammock reflected.

"I don't know as if he struck you as mad..."

Mr Lammock smiled at her affectionately and did not answer her implicit question.

"I shall wear my light grey suit to-day," he said, "if you will put it out and run me a bath. And I won't have any lunch. I'll have tea at four sharp with two boiled eggs and some hot buttered toast.

"There's a tea-cake," said Mabel.

"Then tea-cake let it be, piping hot with plenty of real butter."

A WEEK later Mr Noah Lammock was writing very briskly and contentedly in his study. All his courage had returned to him. The sentence he was writing seemed a particularly happy one. He felt he could give it a turn...

That arm-chair he kept for visitors creaked and creaked again. He was aware of the faint rustling of a large body coming to rest. He did not look up until he had finished his sentence.

"I knew you would come back," he said.

He lifted his eyes and beheld the quite solid and friendly countenance of his Heavenly Friend. The divine glance fell on the numbered pages on the desk. "Have you done much?" said the Lord.

"The beginnings of a general memorandum upon aims and means. Shall I read it over to you? Where, by the way, have you been since I saw you last?"

"Going about and finding out things that might be useful for us."

"With your shadow?"

"How else?"

"Doesn't he criticise and cast doubts?"

"Mephistopheles! What else is he for? He said: 'If you go on as you are going you will become a mere luminous aura.' To which I answer: 'And then his shadow will swallow you up, and where will you be then? Get thou behind me, Satan. Go away.' I hurry away from him. But there he is at my heels, meeting me whenever I put my foot down. I can't get clear of him."

Something in that bickering touched Noah's sense of humour. He laughed. He thought of his woolly-haired, long-bearded Lord trying desperately to shake off his shadow from his feet as a man might kick off a pair of galoshes—and vanishing himself, with an expression of astonishment, as the galoshes flew away.

And when Noah had made an end to his laughing, he stared at the Lord. "In the whole of that Bible story," he observed, "neither you nor Satan laughed. I never noted that before."

"I don't remember that we did ever laugh. Why should we?"

"Flat earnest from first to last. That is where the new sort of man you have to deal with has the advantage of you; that sudden perception of incongruity. He laughs, and the conquering absurdity dissolves before him. We shall laugh. Laugh and begin again. During this flood and after this flood. In spite of the blood and tears. Nothing is intolerable, however monstrous it may be, when it is seen to be absurd. I assure you. Nothing. 'Life begins every morning and it is fundamentally absurd.' This is the greatest of discoveries. So we escape from the vindictive tyranny of past things. So, in our more intricate and wonderful world, we build our tower and the prospect broadens as we build."

This was something the Lord did not understand. He shook his head—but tolerantly. "Tell me about this memorandum of yours," he said.

"TO begin with," read Mr Lammock in a magisterial voice, "we have to consider as precisely as possible what it is we want to save. We must be clear about that before we come to question two, from what it is that we want to save it. Then having got that stated, then and only then are we in a position to plan the immediate Ark. It has to be something—reserved, narrow, ship-shape and seaworthy, that will weather all the confusion that gathers about us. All aboard we shall go for Ararat. And as we reminded each other last time we met, the story does not end on Ararat. Out we shall pour at last on that delectable mountain, no doubt in a blaze of rainbows. You must see to that." The Lord winced slightly. "But the real crisis lies ahead—at Babel. We have to think of Babel, before we set a hand to the Ark. Are we agreed on that?"

"How right you are!" said the Lord. "My enquiries—"

"Will you forgive me if I read my memorandum first? What is it, we ask, that we want to save in this Ark of ours? Are we in the least clear about that? We do not want to save the old world that is now being inundated at such a terrific rate by warfare, hatred, cruelty. We have done with this world for good and all. Is that so? Whatever else our Ark may be, it is not going to be a device for saving seeds and samples of all sorts, so that presently everything that made life disgusting and unbearable to you, will reappear..."

"My idea was to save the best of it."

"Was there really a best of it?"

"Suppose I tell you first of all about the stuff I have found out. Then we can go on to that."

"What have you found out?"

"From one or two things I had read of yours, I realised that an important idea of yours was the need to bottle down and make some sort of cache, or caches, containing all human knowledge and thought and achievement up to date, a sort of Museum Encyclopaedia, so that when this inundation of war, disorder, famine and pestilence is over, if ever it is over, then it would be all ready for a tremendous renascence. That museum of yours, dusty and derelict, is in your Time Machine for example."

"I never wrote The Time Machine," said Noah. "Why pretend?" said the Lord. 'The same idea is the framework of your Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind. It is World Brain. It crops up more and more frequently in your books as you get older and repeat yourself more and more—"

"I tell you—. I had nothing to do with these books."

"Rubbish! You as are bad as that fellow Bacon. He wrote the entire Elizabethan literature and Ignatius Donnelly proved it. I am a convinced Baconian. You have written every book with the idea of a world reconstruction in it for the last hundred years. You may not know it, but you have. Under various names. If you did not actually write it at the time, you absorbed it all. There are too many books now for us to talk about individual authors any more. If you think I'm going to stand all that higher criticism stuff of my Book you have been giving me, and not round on you and your authorship in exactly the same spirit... I do you a great compliment in this comparison. As regards variety of style and treatment, narrative vigour, insight, there is of course no comparison—"

As an offended author, the Lord had become extraordinarily real.

"I wouldn't presume for a moment," said Noah.

"I should think not," said the Lord. "I could quote you comments, criticisms, press cuttings, whole fat books and commentaries without a single adverse word. Even your boasted Professor Huxley, the old Huxley, I mean—praised me with scarcely a qualification. For centuries, the literary side of my Book, at any rate, has been the marvel of mankind. It has been the treasure of the humble and the handbook of the mighty. No one, asked what books he would like to have on a desert island, has dreamt of omitting it, no one. And then you insinuate that this modern rag-bag of yours—"

"It was you raised the subject."

"Well I might."

"I merely said I never wrote certain books—"

"Well, I say you did."

"We'll argue no more about it," said Noah.

"You'd better not," said the Lord, still seriously ruffled.

"Tell me what it is you have found out," said Noah. "I agree with every word you say. Your Bible is the fundamental book. Our literature is just a footnote to it."

"Well—" The old gentleman's vexation faded.

"I've found out some very remarkable things. Have you ever heard of microphotography?"

Noah had, but he assumed an expression of bright attention. There was something very endearing about this irascible Divinity, entangled in his own creation, now that one met him face to face. He was, Noah realised, first and foremost an Author, a great Author, as an Author it is that the world knows him best, and the vanity and self-sufficiency of authorship is innate and incurable. And every great author annexes and plagiarises, so why argue? If he chose to make Mr Noah Lammock the Whipping Boy for all the presumption and aggressiveness of modern radical and sceptical literature, it was quite understandable. If he thought he had discovered the possibilities of microphotography, by all means let him have that satisfaction.

"I have ascertained this, that now it is possible and practicable to make these microphotographic films, to multiply and distribute them, so that anywhere in the world it is possible to project and examine the pictures they give in comfort and detail at a charge that beside the cost of a modern battleship is trivial. You can have all the pictures, all the sculpture, all the architecture of the world available for close examination anywhere. You can have every type of landscape, every scene of interest, available. You can see plants at every stage in their growth and animals in movement and in their natural colours and surroundings. You can scrutinise the pages of the earliest and best editions of every classic in the world. And all this can be done and packed away within the compass of a reasonably-sized house. The Libraries of the Vatican, the British Museum, the Bodleian and the Library of Congress at Washington, cover acres of space, are vulnerable and involve a vast labour of indexing. The Nazis may burn any or all of them in the next few years. There is no comparison whatever between them and this new physical concentration of knowledge. I spent a delightful day with Dr Kenneth Mees of the American Kodak organisation, who, by the by, was rather astonished by my visiting card, but too well-bred to show it, and whom I had to convince by one or two petty but reassuring miracles which aroused his curiosity. His explanations and demonstrations were very convincing. Even Mephisto was delighted...

"Why was he with you?"

"He asked to come. He's no fool, you know, when it comes to these mechanical things."

"Anything but a fool. More subtle than any beast of the field you ever made..."

"Anyhow; this thing is a plain and reasonable practicability. You can make this tremendous record now. You can distribute it, in whole or in part, all over the world. You can hide it away in a thousand places. The whole world may be drowned in warfare. Nevertheless we shall have its entire past achievement ready for disinterment. That, I take it, is the very essence of our Ark idea. All that remains to do is to get money and supporters and set about it."

His satisfaction was so simple and direct that Noah hesitated to introduce complications.

"There is one thing I will certainly grant you moderns," said the Lord, "and that is the extraordinary way your gadgets and contrivances facilitate all sorts of things that were roundabout and difficult in the old days. The Word of the Lord used to come to his prophets. In the oddest ways. Now one can ring them up, day or night. But here we are! The Ark problem solved out of hand. It is now simply a question of promotion."

"Ye-e-es," said Noah.

A shadow fell upon the face of the Lord. "Well?" he said.

Noah remained silent for awhile.

"There are times," said the Lord, "when a mulish expression, an opposition expression, a criticising look, disfigures you. To be frank about it, it reminds me of Satan when he has thought of something particularly difficult and nasty. If we two are really going to co-operate in this scheme..." His irritability got the better of him. "Say it," he said. "Out with it."

"I hate to play a Satanic role," said Noah.

"I wonder," said the Lord. "Not once, not twice only have I felt that you too might succumb to the Sin of Pride."

"Pride?"

"Setting yourself up against me."

"But, my dear Lord, if you and I do not anticipate the difficulties he will certainly raise—you know he will—we shall have our Ark scuttled before it is launched."

"Devil's Advocate sort of idea," said the Lord. "

"Something of the kind. If I might return for a moment to that memorandum I was reading to you..."

"Ah yes, your memorandum," said the Lord with the faintest flavour of hostility. "The memorandum you wrote."

"Merely to recall that I was asking: Is it the old world that we want to save and restore, after it has been very properly overwhelmed for its sins and corruption, or are we proposing to make an entirely new world, when this last frightful flare-up of war and the conflicting sovereign states and all the had old traditions, are over? Do we intend to go on with modern ideas, or do we intend to go back with those perfect Christian gentlemen, Franco, Halifax, Daladier, Pétain, Bushido—if you can call that a Christian gentleman—all the shattered hosts of reaction?"

"Need we talk politics?" protested the Lord. "Were your Major and Minor Prophetic Books anything but politics? Anyhow, let us consider this general principle; is it to be a clean new deal or not?"

"On what lines?"

"We can settle that later. The primary question is: do we reinstate or do we start afresh?"

"Well, what is this catastrophe for?"

"Exactly. When you are put to the test, Oh Lord, you are never for the priests and conservatives, you are always for the prophets. You are the invincible Revolutionary. The Bible is the record of your Revolutions. Which is where I fall out with all these people with whom you seem to propose to tie me up, with this World Encyclopaedia, World Brain idea and all that kind of thing. What do their ideas really mean? It seems to me that so far as these proposals are revolutionary at all, they are an attempt to play the game of the French Encyclopaedists over again, to smuggle a complete modern ideology into people's minds, disguised as an impartial assembly of useful and memorable things. It worked then, I admit. It gave the great French Revolution eyes. But can you do a thing of that sort twice? Non his in idem. People ask at once who is to edit it all, they regard our all too hopeful Wells with the profoundest suspicion, and that is the gist of the matter—"

"So you don't think that microfilm encyclopaedism is, in itself, the solution of our problem?"

"No," said Noah. "Not a solution. It may be part of a solution. It is indeed something that has to be done. But only in a definite relation to other, more fundamental things. This indiscriminate Encyclopaedia you have in mind, will, I warn you, bring back the seeds of every sort of error. Naturally Mephisto sustained you in that. Naturally. Because, believe me, he saw his inevitable come-back in it; all the old heresies, all the old romanticisms, all the old plausible falsehoods, the catch phrases, the intellectual infections. It would be the confusion and dispersal of Babel over again, a confusion of mental idioms if not a confusion of tongues. That poor collapse Aldous Huxley travelled round the world with an Encyclopaedia Britannica until his mind gave way.

"Yes, yes," said the Lord. "But also, as you with all your modern knowledge must know better than I do, there must be countless grains of truth lurking in that mass. Half-born discoveries. Remember for example the story of argon. How Cavendish left notes, of what was practically its separation, nearly a century before it was demonstrated..."

Noah reflected. "I admit there is hardly a statement that has ever been made on earth that has not had a grain of truth in it. Even the monstrous beginnings of Shintoism must be an attempt to express something which may prove ultimately to be of enormous importance in the history of the human mind. Graffiti, tradesmen's bills, the lives of the Saints, medieval romances and detective stories are full of material for the myriads of research students we shall have in our new world. Save it all, I agree, save it all, for when it is needed, but do not cumber us with it while we sail the Ark. It shall not perish. Let us have it aboard by all means. It may serve as ballast. It may serve as food.—Deep down in the hold, under hatches stowed away... Yes...

"But up above upon the quarter-deck, what we want, dear Lord, is a purification, a cleansing of minds, a will unified and reborn. We want something absolutely quintessential for the élite and something absolutely honest, convincing and simplified for the masses of mankind..."

"SOMETHING quintessential for the élite and something very strong and clear and simple for the masses of mankind."

Like that. Before he forgot that sentence, Mr Noah Lammock—following a practice he had acquired from the works of J. W. Dunne, wrote it down on his writing-pad. Then he became more fully awake. For a long time he gazed with a speculative eye at that vacant arm-chair confronting him. Then he rang for Mabel.

"Another of those nice long sleeps," she said. "They do you a world of good, overworking and worrying as you do, night and day."

Mr Lammock thought he would have a cup of tea and go for a walk. "Nothing has been heard of that old gentleman—you remember?" he asked casually.