RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Reilly & Britton Co., Chicago, 1910

The Reilly & Britton Co., Chicago, 1910

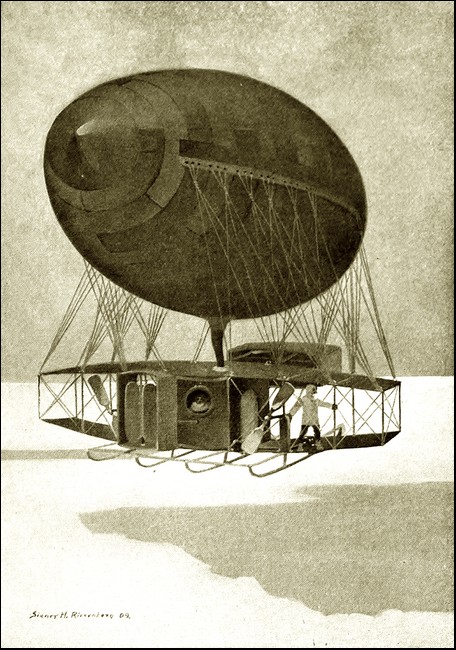

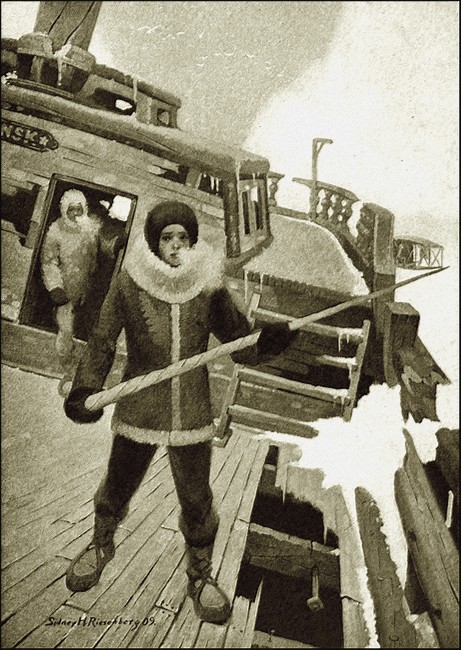

Frontispiece.

Spinning along above the white chaos below.

WHEN the three thousand-ton steamer Roger C. Waldo, out of Boston in the Nova Scotia trade, was purchased and sent on her long journey around the Horn to San Francisco, it was for the purpose of overhauling and refitting her. Early in the following spring when she came into commission again, it was under a new name and a new commander. On a certain afternoon in late April, rechristened the Aleutian and with Captain Thomas McKay, recently of the Alaska coastwise trade, on the bridge, the staunch sixteen-knot vessel lay in one of the slips near the old India dock at San Francisco ready for sea once more.

The steamer flew no company flag to indicate in what part of the world her new course might be and no list of "sailings" in the papers of that date called attention to her departure. Only her own increasing smoke, a squint-eyed man in a pilot cap at the starboard end of the bridge, and a tug standing by with steam up indicated that the vessel was about to put to sea.

But these signs had attracted the attention of one person. A young man, who had just been refused permission to ascend the landing ladder, had run forward along the dock until he was beneath the bridge. As he stopped for breath and looked up, the squint-eyed man in the pilot cap on the bridge smiled in greeting.

"Tom," called the young man, "who's the skipper o' this vessel and where is he?"

The man addressed only smiled again and jerked a thumb over his shoulder.

"What's the matter with you?" shouted the young man, who was apparently in no pleasant frame of mind. "Tell him the shipping reporter o' the Chronicle wants to come aboard."

Before the pilot could reply, a ruddy-faced man with close-cropped grey whiskers and sandy hair stepped to the end of the bridge.

"I'll be Captain McKay," he exclaimed with a smile. "What might I be doin' for ye?"

"I want to come aboard."

"I'm sorry," replied the officer. "'Tis no time for veesitin'. We'll be soon sailin'."

The young man's face grew red.

"I'm Ingersoll," he exclaimed impatiently, "of the Chronicle."

"An' I'll be Captain McKay o' the Aleutian. Verra glad to meet ye," was the reply in a soft Scotch burr.

"Can't I come aboard?"

"'Tis too late, lad."

The reporter's face flared in anger.

"What line are you?" he snapped suddenly.

The officer above shook his head. "Private craft," he added.

"Tramp?" the young man almost sneered.

"Not in trade," good-naturedly responded the skipper, unruffled.

At this moment and before the young man could further vent his anger a cab rattling up to the dock entrance attracted his attention. As a tanned, military looking man using a cane alighted and made his way toward the ladder of the steamer the reporter hurried forward and intercepted him.

"Can you tell me where this vessel is bound?"

"She has cleared for Unalaska."

"Ah," exclaimed the reporter looking back and upward with some exultation toward the non-committal captain on the bridge. "In the Alaska trade?" he continued.

"I didn't say so," answered the military man quietly.

The interviewer flushed in anger again.

"She certainly carries a lot of junk," the reporter added, sweeping his eyes over the well laden amidship's deck.

"I hope it isn't," calmly retorted the man. "It has been selected with considerable care and at some cost."

"Say, look here, Captain," suddenly exclaimed the reporter. "What's the use of all this mystery? I only want to know what's usually told. Your voyage is certainly regular, isn't it?"

"Quite irregular," responded the new arrival with a laugh. "Perhaps I should say 'unusual.'"

At that moment the squint-eyed man in the pilot cap on the bridge, who had been an amused spectator of the proceedings below, roused himself, glanced at his watch and turned toward the sandy-haired skipper.

"Captain," he exclaimed, "it's a bit after two o'clock. The tide is full on the bar at three. Time for all ashore."

Captain McKay advanced to the forward rail of the bridge. Just below, and on what had been the promenade deck of the old Waldo, two officers and two young men were leaning over the port rail conversing in low tones.

"Mr. Wales," exclaimed the captain, "see that all going are aboard. Clear the ship of those not going. Then stand by to cast off."

The two officers sprang to their duties and the boys turned and faced each other.

"Where's Ned!" exclaimed the elder.

"In his cabin, writing," answered the other. "I've done mine." As he said this he exhibited a bulky letter.

"I'll have to wait until we get back, I guess," added the first speaker a little sadly. "I'd like to tell the world what we hope to do, if I could," and he shrugged his shoulders. "But I guess the public can wait. It ought to be worth waiting for."

"The Major!" suddenly interjected the younger boy. "I wonder if he's returned."

The next moment both boys were on the pier side of the Aleutian. In the midst of a few dock employees and a dozen or so idlers they saw, amidships, the late comer and the perplexed reporter. At sight of the two boys the reporter's chagrin broke out again.

"I see," he exclaimed. "Unusual, eh? Kind of a training ship for boys?"

The halting passenger smiled again and then his face took on a sober aspect.

"My young friend," he observed, "you are wholly wrong. This vessel is not a training ship. Your persistence is excusable, of course. But I must refuse you any details of our voyage. This I will say, and it must satisfy you. My name is Honeywell—Major Baldwin Honeywell, late of the U. S. Army—"

The Chronicle reporter sprang forward, glanced quickly again at the two boys leaning over the rail above him, grasped the speaker excitedly by the arm and almost shouted:

"Are you the gentleman who sent those Chicago lads into the Arizona mountains in a dirigible balloon?"

The man addressed smiled, hesitated and then acknowledged his identity.

"And are these the kids?" exclaimed the young journalist, pointing to the boys at the rail above.

At this point Major Honeywell laughed outright. Then, glancing upwards and extending his arm, he exclaimed:

"On our left," pointing to the younger of the two boys, "Mr. Alan Hope, who has the undeniable distinction of being one of our justly famed young aeronauts." The reporter did not join in the general laughter, and the Major continued: "On our right, his friend and but little less famed associate, Robert Russell of the Kansas City Comet."

As the reporter recovered himself and made an attempt to turn the joke into a formal introduction, he turned suddenly upon the Major once more.

"And where's your star performer—Ned Napier?"

"Right on deck when called!" replied a new voice, and a third young man suddenly obtruded his form between Hope and Russell.

"Well, I'll be blowed!" was the journalist's only comment.

"What's wanted?" exclaimed the newcomer, a smiling-faced, tousled-headed youngster with ink-besmeared fingers. "You aren't the pilot, are you?" he added, leaning over the rail and exhibiting a bulky envelope.

"No," answered the reporter slowly, "I'm not." Then, breaking into a laugh, he added, "I'm certainly no pilot. I can't even steer myself, let alone a ship. But," he continued in a resigned tone, and turning again to Major Honeywell, "I interrupted you."

"As I was about to remark," continued the Major in a kindlier tone, "my name is Honeywell. In conjunction with a few other gentlemen, who do not desire to be known, I have purchased this steamer and sent her to this port from the other side of the continent. Further than that, all that can be said is this: 'The three thousand-ton steamer Aleutian, Captain Thomas McKay, sailed to-day for Unalaska. She crossed the bar at three o'clock. Major Baldwin Honeywell, one of her owners, and a few friends were aboard.'"

At this moment the sharp cry, "Cast off your stern line," rang out aft, and Major Honeywell made his way to the ladder, where waiting hands were ready to assist him up.

There was a short blast of the tug's whistle on the far side of the steamer and then in quick succession came the orders to cast off the breast and bow lines. Ingersoll of the Chronicle, balked but yet determined, rushed forward as if to throw himself on the now ascending ladder and wrest from the big, gray, silent vessel the secret that he now knew was there. Three mournful, hollow blasts from the hoarse siren of the Aleutian told him that he was too late.

"Say, Russell!" he shouted, putting his hands to his mouth funnel-wise. "If you'll loosen up and do us a story the Chronicle'll give you extra space on it."

While he yet pleaded, the Aleutian slid into the open waters of the bay and a few moments later the sudden ceasing of the tug's "chug chug" and three more blasts of the steamer's whistle indicated that the mysterious craft was forging ahead under her own power.

At half speed the deep-laden Aleutian made her way up the great bay. In half an hour the tall buildings of the city, and soon afterward its villa-topped hills, had dropped astern. The gay pleasure craft, lying low before the fresh breeze, and the bustle and cheer on the larger vessels entering port were in marked contrast to the serious faces of those on the gray steamer.

"A cheer or two and a few toots of a whistle would help a little, wouldn't it, boys?" exclaimed Ned Napier. "But it's what we wanted. We ought to be satisfied."

"Or at least one 'Good luck!' one 'bon voyage,'" suggested Bob Russell.

"Wait," interrupted a voice just behind them. It was Major Honeywell's. "Yonder is Fort Point."

As the Aleutian altered her course and the swell of the Pacific swept in through the Narrows this last western post of Uncle Sam's outlined itself on the rocks to the right. At a smile from Major Honeywell, Captain McKay gave the word and an instant later the stars and stripes went sailing aloft at the stern. Almost instantly a white ball of smoke rolled from the parapet and then the boom of a cannon came over the water.

"Do they know?" asked Alan quickly.

Major Honeywell smiled again. "It is Captain Hearne," he said, lifting his hat toward the fort. "I have known him for twenty-five years. I dined with him last evening."

"Then he knows," exclaimed Ned.

"Somebody must," thoughtfully answered their elder. "He is my brother officer. It is his 'Good luck!' and 'Farewell,' the first and last salute our expedition will receive."

Then the Narrows opened out into the wide Pacific; the Golden Gate—that Mecca of mariners for centuries—passed astern and the engines of the already rolling steamer came to a pause abreast the pilot schooner. A small boat came alongside and Tom, his pockets laden with the last letters and messages of the voyagers, made ready to drop overboard. On the bridge he took his farewell of the skipper:

"Captain McKay," he said, "I never had the honor o' meetin' ye afore but I give ye good luck and safe voyage. When ye return it's me hope to bring ye in—"

"Thankee now," answered, the soft-accented officer, "but I misdoubt it." And then, in a yet lower voice: "We'll hardly be comin' this way, again."

There was nothing more to be said. The discreet pilot descended to the deck, raised his cap to the group assembled there and scrambled nimbly over the rail. For a few moments the steamer rose and sank idly on the long heave of the Pacific. Then Major Honeywell, standing alone and thoughtfully gazing shoreward, turned and nodded to Captain McKay standing at the signal wheel. The soft-voiced skipper faced the pilot room just above.

"What's the hour, Mr. Wales?"

"Three fifteen P.M., sir."

"Very good. Make it so. The course is west by north one half north."

Mr. Wales and the wheelman on watch threw the wheel over, Captain McKay gave the signal lever a turn, the answering arm flew to "full speed ahead" and the Aleutian forged slowly onward—finally at sea on her unheralded voyage of peril and mystery.

WHEN Major Baldwin Honeywell made known his name to the Chronicle man on the dock just before sailing, it was not surprising that the reporter instantly recognized his identity. The exploits of Ned Napier and Alan Hope, "The Airship Boys," and their friend, Bob Russell, the reporter, had received more than passing mention in the newspapers. To newspaper men the adventures of the boys with their dirigible balloon in search of the "Aztec Treasure" and their subsequent remarkable rescue from drowning in the Pacific when they were "Saved by an Aeroplane" were both recent stories. And Major Honeywell, as one of the promoters of these enterprises, was not less well known to the public.

The long letter that Ned Napier had finished just before the Aleutian left her dock was addressed to his mother.

I can now tell you a little more about our plans, [the letter ran], "but I can't tell you all. We haven't even yet been told just where we are finally going and what we are to do. As you know, we are headed to the far north and directly into the Arctic Seas. Somewhere up there, Alan and I are to assist, somehow, with our aero-sledge. We hope to return late this fall.

My best news is that Bob Russell is with us. At our request and on the endorsement of Major Honeywell and Colonel Oje, Mr. Osborne consented and in four days Bob made the trip from Kansas City. He has an indefinite leave of absence from the "Comet," and, like those of us who are members of the expedition, he is taking pretty much everything on faith. Undoubtedly we are going to have strange adventures, and probably perils are ahead of us. But remember the old saying: "Nothing venture, nothing have."

I have been told at last how the expedition came about and the real originator of it. The man most deeply interested in it financially is Mr. James W. Osborne of Boston, a millionaire manufacturer of rubber boots and overshoes. Although he is nearly seventy years old, he is sailing with us.

Mr. Osborne has more the appearance of a student than a business man. He is smooth-shaven and wears small nose glasses. At time he has the look of a man who is thinking of something far away. Certainly he has a big idea of some kind, but what it is I can't yet tell you.

Early last summer Mr. Osborne spent some weeks in San Francisco arranging for the "Waldo's" arrival. On his way back East from Seattle he came by way of Denver and was a passenger on the same train that carried Major Honeywell, Colonel Oje, Bob Russell and Elmer to Chicago, after they had given up the search for Alan and me in the mountains. Between Denver and Chicago the Major and the Colonel and Mr. Osborne became acquainted. Before they separated Mr. Osborne invited them to join him on this voyage.

A few weeks later when Major Honeywell and Colonel Oje were in the East disposing of the metal and the other Mesa treasures, they visited Mr. Osborne in Boston. I don't know what argument was made to persuade Colonel Oje to go, but he finally consented to do so if allowed to defray part of the expenses. So he too has an idea.

Major Honeywell, as an ex-military man with some scientific knowledge, was urged to go and take charge of the expedition. He too consented on condition that he also become a financial partner. And it was also one of his conditions that Alan and I be employed to take charge of a balloon and aeroplane equipment which he insisted should be added to the outfit.

At least, when Major Honeywell and Colonel Oje became partners in the voyage, there were new plans made, or the first one was charged. When the "Waldo" reached San Francisco she was completely overhauled and two months ago Captain McKay arrived here and took charge of her. I have already written to you describing her stores and the immense quantities of coal in her. Because she is full of coal, not only in her bunkers but in much of her freight hold, there is a mass of material on deck.

As it is time to cast off I must bring my letter to a close. Don't worry, for we shall come back safe and sound.

Your loving son,

Ned Napier.

As the Aleutian at last got into free sea-room and

settled on her course, Ned, Alan and Bob all became suddenly

thoughtful. The excitement of the departure was over, and the

steamer seemed strangely silent. There were no enthusiastic

passengers rushing about, locating steamer chairs; the few

members of the crew under Mr. Wales went noiselessly at their

tasks of stowing odd ends and lashing fast the harbor boat; and

even Captain McKay had disappeared from the bridge. Only a

solitary sailor paced back and forth on the bow watch and when

the austere figure of Mr. Osborne appeared suddenly from the deck

stateroom just adjoining Captain McKay's quarters, the three boys

went aft.

There, near the unused wheel on the upper deck, they took station at the rail. At last Bob, who had been watching the distant Cliff House drop lower and lower into the horizon, aroused himself and with a glance over his shoulder as if to be sure he was not overheard, exclaimed:

"I suppose we are at least entitled to a guess." The other boys looked up. "Where are we going?"

Ned and Alan smiled.

"I've guessed it a thousand times," said Alan in a low tone.

"And the answer?" suggested Ned, almost laughing.

Bob, leaning forward and striking the rail, exclaimed, with some emphasis: "It must be the North Pole! What else can it be?"

"That's it," answered Ned. "What else can it be? That's the mystery."

"If this was an old whaling craft with double oak decks and steel bows I'd say the Pole," interrupted Alan. "But whoever heard of a passenger steamer touring to the top of the world?"

"I've heard of them going pretty far that way, off Spitzbergen," answered Ned in a low voice. "But I don't think Mr. Osborne cares much about the North Pole. And I'm sure Colonel Oje doesn't."

"Then what's that aero-sledge of yours for?" exclaimed Bob. "You say you can use it as an aeroplane or as an ice yacht. Doesn't that look like a dash over the ice and snow?"

"There are nearly three million square miles of ice and snow in the unknown polar regions," replied Ned. "The Pole is only a point in that waste."

"You can be sure of one thing at least," put in Alan. "Everything we are going to do has been thought out. Every preparation has been made for some systematic work. And we are three mighty lucky boys to have a chance to share in it."

Ned turned and looked seaward. The sharp spring air had a sea tonic in it; the long roll of the ocean breaking on the Aleutian's low sides sent a soft spray over the boys.

"Isn't it great?" Ned exclaimed, pulling off his cap and thrusting his face into the breeze. "It's worth even the risk of the unknown. I hope—" and he faced about with a happy twinkle in his eyes—"I hope we do it—whatever it is."

"And I hope," added Alan, as enthusiastically, "that it is the Pole!"

"And I hope," exclaimed Bob in turn, "that, at least, we go where white men have never been before."

Just then the Aleutian's bow, plunging through an extra high swell, settled quickly and with a side motion into the hollow beyond. Righting herself on the next roller, the steamer stuck her nose in the air and then struck the sea again with a crack and a shiver. Bob, who had released his hold on the rail, lost his balance, stumbled forward and then brought up sitting on the edge of the skylight, his face, suddenly, very pale.

"What's the matter, Bob?" exclaimed Alan.

"Matter?" repeated the reporter as he arose feebly. "Nothing's the matter."

"Ever been to sea before?" asked Ned, kindly.

"Never," answered Bob slowly. And then, looking up with a ghostly smile, he added: "I guess I've got it."

The other boys were just suggesting that he go forward to his stateroom and lie down when Mr. Wales, the first officer, appeared. Without noticing Bob's condition he exclaimed:

"Young gentlemen, Mr. Osborne's compliments and his request that you come forward."

As the officer turned and disappeared Alan exclaimed, in a low voice:

"He's going to tell us!"

Ned assisted Bob to his feet.

"Are you seasick?" he asked solicitously.

"I was," exclaimed Bob with grit. "But if Mr. Osborne is ready to talk I'm cured."

THE old Waldo being a passenger steamer, and originally in the West India service, her cabins were large and well ventilated. Captain McKay's room just abaft the pilot house was particularly large, extending the width of the upper works.

Mr. Wales beckoned the boys toward the open door, within which Ned was surprised to see Captain McKay and the three owners of the vessel. Mr. Osborne and Major Honeywell occupied two chairs on either side of the deck, attached to the forward wall. Colonel Oje, the wealthy ranch and sheep owner, was sprawled on Captain McKay's berth over which he had thrown a blanket. The captain sat on a camp stool, his cap on the desk, with a sailing chart crumpled over his knees.

Mr. Osborne sat looking toward Captain McKay as if partly listening and partly thinking. As the boys blocked the doorway Captain McKay paused. Major Honeywell nodded his head, spoke in a low voice to the abstracted Mr. Osborne, and, with a smile, signaled to the newcomers to enter.

With a laugh and a careless flip of his cigar ash on the floor, Colonel Oje sprang up.

"Here, young men," he exclaimed, "a couple of you sit here. I'll get out in the air. Excuse me, gentlemen," he added, addressing all, but apparently more for Mr. Osborne's benefit.

As Colonel Oje picked up his wide, white plainsman's hat, which he had not yet exchanged for maritime gear, and breezily left the cabin, Captain McKay arose and made room for the boys.

It was only then that Mr. Osborne bowed from his chair. Captain McKay was rolling up his chart. While he did this Ned detected Mr. Osborne glancing from himself to the other boys as if making an inventory of them. The task of rolling the chart finished, Captain McKay stowed it away, and with a look first at Major Honeywell and then at Mr. Osborne exclaimed:

"Well, gentlemen, what'll it be? We can do fourteen knots, I 'm thinkin' but it'll call for coal. An' if we miss the collier—"

"That is an 'if' we need hardly consider, Captain McKay," interrupted Mr. Osborne. "You may push the engines to their limit, Mr. McKay."

"Verra good, sir," the trim little Scotchman replied. "Unless I'm meestaken we'll find oursel' a roundin' Cape Kalighta in seven or eight days."

"Thank you," said Mr. Osborne.

Captain McKay, apparently accepting this as his dismissal, left the room. For a moment all sat without speaking. Then Ned, assuming the role of representative, exclaimed: "You sent for us, sir?"

"We have quite a voyage before us," said Mr. Osborne, without making direct answer. "It occurred to me that we ought to have some general understanding." As he said this he glanced at Major Honeywell. "Which is Mr. Russell?" continued Mr. Osborne in the same calm tone. Ned indicated the still qualmish reporter and Bob bowed.

"Ordinarily, I am told," went on the reserved speaker, "on an expedition of this sort all participate in the ship's duties. I see no need for such an arrangement on the Aleutian. Captain McKay has a small crew, but one able, I understand, to care for the steamer. Mr. Napier and Mr. Hope will have, in time, quite likely, certain professional duties. Until that time arrives you are both free to spend your time as you please.

"Mr. Russell," he continued, turning to Bob, "the owners of the Aleutian extend to you their hospitality. As our guest you will also make yourself free on board. I believe each of you has been assigned a stateroom?"

Each boy bowed in assent.

"We dine this evening at seven o'clock."

Seeing that the interview was at an end the boys arose. Ned, speaking again for the others, said, a little awkwardly: "We thank you, sir."

Before they could leave the cabin Mr. Osborne, who had also arisen, turned to Bob and added:

"I am told you are a journalist, Mr. Russell."

"I am at least a reporter," Bob answered modestly.

"I have great respect for the press of our country, sir," exclaimed Mr. Osborne, "and I trust you may find your voyage with us both instructive and interesting."

"I'm sure it will be both," answered Bob. "I'm certainly grateful for the honor you do me in permitting me to join you. I hope you will call on me for any task that is in my power to execute."

"I believe you are assigned to Colonel Oje," answered Mr. Osborne, dropping again into an abstracted air. The boys looked quickly from one to the other and then, Mr. Osborne dropping once more into his chair, they bowed in turn and left the cabin. Outside, without speaking, they moved quickly toward the stern.

"Well, by the Great Horn Spoon," ejaculated Alan at last. "Assigned to Colonel Oje! You—" he added pointing to Bob and laughing.

"We dine this evening at seven," said Bob, his face a puzzle. "The secret is out at last!"

Ned was too astonished to join in the laughter. "Well," he exclaimed at last, "what do you expect? We are all hired hands, aren't we?"

"I should say not," retorted Bob, laughing, "not I. Representing the honored and respected press of our nation, I'm a guest."

For a long time the boys hung over the rail, hugging to their breasts the joy of the sea. They speculated and they theorized, but it was to no end. Finally it was wholly dark.

The dining saloon of the former Waldo had been on the main deck. This part of the ship had now been cleared, and the space, together with that once devoted to staterooms on this deck, was packed with freight. The new dining room was on the upper deck in the space between the large staterooms, formerly the "social hall." The cook's galley was retained on the main deck below.

On the forward upper deck Captain McKay's room adjoined the wheel house. Then came Mr. Wales' and the second mate's rooms. Adjoining these were four special staterooms, two on each side of the vessel, in three of which Mr. Osborne, Major Honeywell and Colonel Oje were located. On each side of the "social hall" aft were six single and two double staterooms. The boys had their choice of these. Bob selected Number 27, a single room, and Ned and Alan took 29 and 31, double rooms connecting. The engineer, Jackson, and his assistant were in 33 and 35; the cook and the steward in 34 and 36; four wheelmen were in the double room 30 and 32, and 28 was unoccupied.

When the boys entered the social hall and dining saloon, they found it aglow with electric lights. In the gold painted ornamentation of the ivory white woodwork scores of bulbs sparkled and brought out the warmth of the heavy crimson carpet. On the snowy cloth of the long table a bowl of roses gave additional color to the picture. At the entrance the boys paused while a Japanese boy in a white jacket drew himself up and saluted.

"Does this look like the North Pole and icebergs?" began Bob.

"Or walrus meat and seal blubber?" put in Alan.

"You can't tell," said Ned soberly. "Not these days."

The first meal on the Aleutian began under somewhat of a strain. For the time there were only formalities, for Mr. Osborne, on Captain McKay's right, seemed to make some ceremony of dining. Until after the fish was served Mr. Osborne, next to whom Ned was sitting, gave little attention to his neighbor. At last, turning unexpectedly, he remarked, almost casually:

"We were discussing your aero-sledge this afternoon, Mr. Napier. Are you quite convinced that it is practical?"

Ned, a little embarrassed, thought a moment:

"Not wholly," he answered at last. "But I have tested so many of the theories applied in it that I am convinced that it is well worth a trial. Of course," and he smiled, "I couldn't actually test it, as it has never been assembled. I know the balloon will fly. We need no longer consider the aeroplane a theory. And as for the sledge idea, I can only say I believe it is practical."

Mr. Osborne nodded his head without comment.

Finally the coffee and cigars were reached. Ned and Alan, partaking of neither, were about to retire, when to Ned's renewed surprise, Mr. Osborne addressed him again in his usual low voice:

"Mr. Napier, would it be too much trouble for you to tell me about your new idea in air navigation?"

"I DON'T know that I can call it our idea," Ned began. "There is so much that is now understood in aeronautics—so many practical, worked-out ideas, that we haven't done much but put together other persons' work."

Ned hesitated and then added: "But I can show it better with a blue print." Hastening to his stateroom, he returned with a folded sheet of plans. As he spread it on the table those about him drew their chairs closer; all except the reserved Mr. Osborne. Ignoring the blue print he sipped his coffee and seemed indifferently waiting.

"When we learned," went on Ned, "that the balloon would probably be used in very high latitudes we decided that a dirigible would not do. Unless the bag is rigid, you can't drive a wide-surfaced balloon against a wind blowing thirty miles an hour."

"Why?" asked Mr. Osborne.

"The elastic surface would collapse," answered Ned and continued:

"You could go forward with a thirty-mile wind, but you couldn't come back. We decided to attach to the balloon an aeroplane instead of the usual car. In that way the craft could go forward with the wind and, if it couldn't come back against it, the balloon might be abandoned and the aeroplane used.

"But the trouble with this was," went on Ned, "that if the balloon drifted several hundred miles from the fuel supply and you counted on returning with two or three passengers in your aeroplane, the gasoline capacity would be so reduced that you couldn't fly all the way back. That is why we determined to fly part way back and sail the rest."

Mr. Osborne leaned forward and glanced at the plan.

"We merely took another step. Having turned a dirigible frame into an aeroplane, we altered the aeroplane into a flying sledge."

"Let me see," interrupted the millionaire manufacturer. Ned took up the blue print and held it before him.

"You recall the two long, landing skis or runners under the center of the Wright aeroplane?" continued Ned. "Well, we make these actual runners strong and elastic and heavy enough to bear up the car."

"An' will ye be pullin' it wi' dogs?" interrupted Captain McKay.

"When you've gone as far as you can in the balloon," resumed Ned, shaking his head and smiling, "the useless bag will be cut away and your aero-sledge will rest on the ice or snow. When the wind comes fair you turn the top and bottom surfaces of the aeroplane vertically on their hinged fronts and, well, why can't you sail just as you would in an ice boat?"

Captain McKay knit his brows.

"You can see," interrupted Alan, indicating on the plan, "that the vertical guiding planes in the rear become the rudder and that the horizontal guiding planes in front, with slight readjustment, can act as a jib."

The Scotch skipper smiled.

"And what'll ye be doin' when ye meet open water?" he asked.

"Throw down the planes, start your propellers and fly!"

While the astounded Mr. Osborne and Captain McKay leaned back and listened Ned gave them a brief summary of the apparatus. The device for regulating ascent and descent without ballast was a distinctly novel feature. Five small resistance coils were to be hung within the gas bag and connected with a small dynamo operated by one of the propeller motors. These coils were safeguarded from igniting the gas by being encased in aluminum cylinders, in which they were insulated—and by fuses on the feed wire outside the bag.

"After the loss of an appreciable amount of hydrogen," explained Ned, "the heating of the remainder increases its volume, forces the heavy atmospheric air out of the balloonet and the balloon ascends. The shutting off of the current and the reinflation of the balloonet obviously increases the weight of the balloon, and it descends."

The bag of the White North was an oblong sphere, 69.5 feet in its longest and 27.4 feet in its shortest diameter. The envelope was made of two layers of Japanese silk with a middle and interior coating of rubber, and had a capacity of 87,750 cubic feet. The lifting capacity was nearly 5,000 pounds.

In selecting motive power another innovation was made. This was the use, for the first time on an air vehicle, of the long dreamed of and hoped for gyroscopic or revolving motor. In this motor, although it operates on the four-cycle principle, as do most gasoline motors, the cylinders are allowed to revolve instead of the crank shaft. The shaft is secured to a base and the motor revolves. This engine not only furnishes a steadying, gyroscopic influence over the car, but it solves a difficult problem.

In a temperature of thirty-five or forty degrees below zero water could not be used to cool the motor cylinders. In this motor the cylinders revolved rapidly through the air without water jackets, radiator or even a fan. Incidentally, there was no fly wheel. These motors had a rating of thirty-six horse-power, a normal speed of 1500 revolutions per minute and weighed 97-1/4 pounds each. The cost of the two was $2400.

"The aeroplane itself," said Ned, "is the result of a close examination of the Wright Brothers, Farman and Curtiss machines. Some feature of each is used. Although the propelling power is of almost twice the weight generally provided, and the planes of the car might have been considerably lessened in square feet, we recognized that more weight would have to be carried. Therefore Farman's area of 560 square feet was selected. This provides a frame 42.9 feet long and 6.7 feet wide.

"The steering apparatus is copied from the Wright machine; a horizontal rudder in front fifteen feet long and three feet wide and a vertical rudder in the rear five and a half feet long and one foot wide. The two propellers, because of the divided and increased power, were modeled after the Curtiss pattern, each six feet two inches in diameter, with a pitch of 17 degrees and designed to be run at about 1200 revolutions per minute.

"The aeroplane is divided into seven sections, each 6.12 feet long, except the center one, which is 6.18 feet. The center sections, protected by aluminum-coated silk, lined with felt, is reserved for the operators. The two motors are mounted at the far sides of the sections, to the right and left of the center section.

"The propellers are set on the vertical framework opposite each motor and operated by chain gear. The balloonet blower and dynamos are next to the middle section frame and connected with the motor shafts by belts. The gasoline reservoir is attached to the top of the center section and both it and the feed pipes are thickly encased with felt. Levers to operate the rudders are patterned after the Wright Brothers' design and operated from the enclosed section in which are isinglass-covered port holes.

"The silk planes on both the top and bottom of the end sections are fixed. The planes on all the other sections, except the bottom of the middle compartment, are hinged in front and can be elevated vertically. These surfaces, when in that position, give a sail area of 369.43 square feet. The planes on the bottom of the car are raised and locked into a vertical position by hand. On the top of the car the sections are provided with controlling arms of aluminum resembling the breaking joints in buggy tops. The frames, once pushed into place, hold themselves automatically rigid until a pull from beneath breaks the joint, when they fall again into place and are retained by snap bolts.

"The sledge runners are shod with vanadium steel, increased in number, materially strengthened and given elasticity by the installation of stout steel springs as shock absorbers on each vertical brace.

"They afford a foundation for a most important contrivance. Braced into one rigid body, the middle runners are also strutted so as to provide a small front and rear platform. Here surplus stores can be lashed and carried until air flights are attempted. Then, of course, they are cleared. These platforms also give access to the front and rear rudders.

"Although these aeroplane rudders are braced independently of the sledge platform and operated directly from the center section, the front or vertical rudder is also supported by the sledge platform. On this it is pivoted so that, from the platform, its vertical movement can be thrown, by a lever, into a horizontal motion. In this manner, while operating as a sledge, the rudder can be turned into a jib for the control of the sledge in the wind."

The weight of all this apparatus, which Ned read from his memorandum book, was:

When the White North made her remarkable flight after

the steamer Aleutian was finally beset in the ice, she

carried considerable additional weight in instruments and tools.

This included:

There were, when flight was finally made, in addition to the two heavily clad passengers 125 pounds of provision which included a spirit stove and ten pounds of fuel. The provisions on board included pemmican, salt pork, steak, corned beef, baked beans, and preserved butter in tins; biscuits, tea and cocoa, sugar, salt, cheese and raisins.

The total weight of the balloon, car and equipment, exclusive of the operators, was 4,298.9 pounds. The theoretical buoyancy of the balloon was nearly 5,000 pounds. But, after the two daring young operators were aboard, the condensation of the hydrogen in the extreme cold was found to be so great that but little ballast was needed.

When Ned had finished his explanation, Mr. Osborne relighted his cigar and said:

"I am sure you are going to be of assistance to us. We shall certainly be in the vicinity of ice."

Ned glanced quickly and surreptitiously at Alan and Bob and then, very boldly, he exclaimed:

"I believe, with good luck and a favoring wind, that we could reach the North Pole in this craft."

The other boys instantly realized what Ned meant. It was a desperate probe at the secret that was holding them in suspense.

Not changing his expression, and barely glancing toward Ned, who could scarcely conceal the alarm he felt at his own boldness, Mr. Osborne slowly replied:

"Indeed? It's too bad we can't try it. I'm almost sorry we're not going toward the Pole."

WHEN dinner was at an end the boys went on deck. But the spring wind was raw and the sky was overcast; and as it was easier to talk in their staterooms, all three returned to the double apartment. Here they made themselves comfortable and theorized and gossiped to their heart's content. Until Mr. Osborne made his positive statement there was a general and growing belief that the voyage could mean but one thing—some novel and daring sally into the much debated and almost unknown polar region. But, with that eliminated, the boys could think of no reasonable substitute.

On his trip west Bob had been reading a volume on Arctic research and he was full of the wonders of the New Siberian Islands.

"If we can't go to the Pole, I'd like to go there, if I had my 'ruthers'," suggested the reporter.

"For mammoth tusks?" inquired Ned.

"Why not?" answered Bob. "I think the most wonderful thing in life is to find that some astounding thing you never did believe, is really true after all. I'll never believe until I see it that the flesh of these thousands-of-year-old mammoths is still firm and hard meat that dogs can eat."

"What do you mean?" interrupted Alan.

"He means," explained Ned, "that up there in the New Siberian Islands, north of Siberia, is the fountain head of paleocrystic ice—"

"Come again," exclaimed Alan, while Bob smiled quizzically.

"Well, eternal ice; ice that has existed so long that it is like rock; paleocrystic ice they call it—"

"That's one that escaped me," laughed Bob. "I'm much obliged. It's a dandy word. I'll file it away."

And while Ned went on to explain somewhat of the Siberian Islands, Bob made a note of "paleocrystic" in his memorandum book along with a lot of other Arctic adjectives that he had been compiling.

"These islands are the home of the mammoth," Ned explained. "I'm like Bob," he went on. "I used to read about these extinct, ice-preserved beasts in the geographies, look at the pictures of the tremendous ivory tusks and their coats of long, coarse hair and then pass them by in the same way that I did pictures of fairies with wings."

Alan shrugged his shoulders. "I didn't," he said. "What's the use of doubting such things? I never thought them so wonderful as all that."

"What?" interrupted Bob, somewhat excitedly. "You don't see anything wonderful in those old mammoths?"

"Why, isn't he just an elephant preserved in ice—just like cold storage?"

Bob looked at Alan in disgust.

"Say," he added suddenly, "how do you suppose he got in the ice?"

It was Alan's time to smile. "I give it up," he said. "Just as I give up the question how did the ice get there?"

"That's the point," judicially broke in Ned, pretending to separate the two boys. "How did the ice get there? The mammoth was there before the ice—he couldn't have lived there after the ice came. Once this animal and many others now ex-long extinct in that part of the world—bears horses, tigers—"

"Tigers?" interrupted the prosaic Alan.

Ned simply waved him aside with a confirming nod of the head.

"And even monkeys roamed what are now the tundra wastes of Siberia. There is evidence that these present wastes were then tropic-treed."

Alan began to whistle.

"Wait a minute," broke in Bob. "He's going to give you worse than that. I've read the same thing."

"I suppose this leads up to oranges and pineapples?" laughed Alan.

"Some daring thinkers go further," went on Ned solemnly.

"Well, I don't. And if you fellows think you can string me with any such stories of flower-scented North Pole romances you're off. That's all."

"Again," exclaimed Ned after he and Bob had had a laugh at Alan's skepticism, "I must repeat what I have often said—you are a great mathematician, Alan, but a mighty poor poet. Now let me tell you something—something for you to dream over to-night. It isn't any the less true or less plausible because you don't happen to know anything about it."

"All ready, Professor," retorted Alan throwing himself on a berth and shutting his eyes. "But call me when the lecture is done."

"Before the days of the great glacial period that we read so much about," began Ned, seating himself on the edge of Alan's berth and winking at Bob, "the North Pole was not where it is now. That is, according to some daring thinkers. A few French geological savants—" Alan opened his eyes quickly—"a few French savants," repeated Ned, slowly rolling the word over his tongue boldly and unctuously, "have figured it out that the North Pole was somewhere in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Mexico."

"What are you talkin' about?" exclaimed Alan springing up. "You'll have to show me the books on that."

"I can," laughed Ned, forcing the doubter back into the berth, "but not now. Please attend. After ages and ages the poles as they then were became overloaded with ice. While this was going on the lands of the present North and South Poles were temperate if not partly tropic. Mexico and Central America were icy wastes and Siberia was a flower- and tree-covered region of animal life. Monkeys flitted from tree to tree and the mammoth roamed at will."

"If you'll excuse me I think I'll go out and get some real air," broke in Alan, making an effort to rise.

Bob joined Ned on the edge of the berth to form a barricade.

"You didn't think a mammoth wonderful," went on Ned. "You'll wait until you hear something that is. After the North Pole out there in the Pacific became so loaded with ice that it got top-heavy something broke loose. Some geologists say that was the real glacial period. Any way, our French savants say that this overloaded world of ice upset things and the world wobbled."

"Wobbled?" almost shrieked Alan, "wobbled?"

"Precisely," went on Ned, "and when it did, everything joggled around until it settled into a new place—until the great polar caps broke up and scattered themselves in bits over the land and sea. Then, relieved of its overbalancing loads, the great ball of this world found that it had two new poles. What had been polar regions were now thrown nearest the sun, and the earth had new tropics. And what had been tropic regions now became the lands of the long night, of everlasting cold and paleocrystic ice."

Alan was silent some moments. Then he exclaimed with decision: "Rubbish!"

"Well," added Bob somewhat soberly, "I don't know that I believe it. But that is probably because my teachers never told me anything about it. Anyway," and he slapped his leg, "it's a dandy theory and it explains a good many strange things that I'm told are to be found in the polar regions."

"What?" interrupted Alan, defiantly.

"Coal," answered Bob, "coal good enough for steamers. Found where no vegetation grows today, as far north as the 75th degree. And fossil tree trunks."

"You'll have to show me," persisted Alan decidedly.

"That's what we could do," persisted Bob enthusiastically, "if we had you in the Siberian Islands."

"Do you know," interrupted Ned thoughtfully and addressing both boys, "the one thing that makes this shifting of the poles theory seem a probability?"

"Nothing will make it probable to me," snorted Alan.

"If," went on Ned, smiling, "the North Pole was ever in the Pacific, off Mexico, and the South Pole somewhere corresponding to that on the other side of the world, and you drew an equator between the two, it would pass through present Egypt."

"Well, what of that?" went on Alan.

"Nothing, except that the present equator passes just south of Egypt. That being true, Egypt would be one place on the globe that this world-wrecking deluge of ice would least affect. Perhaps that is why we have specimens of the handiwork of man in Egypt that are so much older than those found anywhere else in the world."

"Say," exclaimed Alan, forcing his way out of the berth at last. "Maybe Mr. Osborne has this same 'bug'. Do you reckon he's going up there to look for fossils and cold storage mammoth skins?"

"You'll find it the trip of your life if he is," persisted Bob. "Think of those great walls of—of—paleocrystic ice on which even the sun has no effect. Why, that's where the icebergs come from—some of them," he added guardedly. "Anyway, I can imagine the Aleutian steaming up to those flint-like, steel-blue glacier walls in which are hidden the mysteries of ages, of some of which man has as yet, perhaps, no hint. I could write it now," he went on, bubbling over with enthusiasm, "how, just within its crystal sepulcher, we first caught sight of the mountain-like shape of a perfect mammoth. Encased in its glassy tomb we could yet make out its erect form—the ivory white tusks, the extended tree-like legs, and the hair-draped hill of flesh. There is a crack, a crash and with a roar of an avalanche the face of the glacier parts; a new iceberg is thrown into the sea and from its heart the mammoth falls at our feet—"

"You spring forward," interrupts Alan in mock enthusiasm, "and your quick reportorial eye detects an implement or weapon protruding from the left foreleg of the beast. With feverish energy you pluck it forth. It is a stone hatchet. And on the side is carved 'A. Sussoski, trapper of mammoths'."

"Good!" shouted Bob. "Good! I have hopes of you. That's fine."

Alan had to laugh in spite of his assumed soberness. "Anyway," he went on, "since there are such notions in existence—and I'll say frankly it's all news to me—I really wonder if our bosses are headed to that part of the world?"

"I hardly think so," suggested Ned. "If they are it would have been easier to lave outfitted in Denmark or even in Russia, and have started from that corner of the world."

"I have an idea," exclaimed Bob.

"Pre-glacial or present?" asked Alan.

"So near the present that it's fresh," answered Bob, smiling. "We all want to know where we are going. I'm going to find out."

"But how to discover the will?" laughed Alan, "as they say in the play."

"Easiest thing in the world when you get to it," answered Bob, "I'm going right to headquarters and ask."

Both boys looked at him almost open-mouthed in astonishment.

"Mr. Osborne?" exclaimed Alan.

"He'll freeze you," added Ned.

"Never been more than frost-bitten yet by any man," laughed Bob. "They say I'm a fair reporter."

THE Aleutian carried three masts, all bearing light canvas. The foremast and mizzenmast also carried a wireless outfit, the operating end of which was now in what had been the purser's room amidships on the main deck. No operator was carried, but the outfit as used on the old passenger steamer had not been disturbed. The upper deck between the foremast and mizzenmast had been cleared of all superstructure—a galley, smoking saloon, the chief engineer's and his assistant's rooms having been thus demolished.

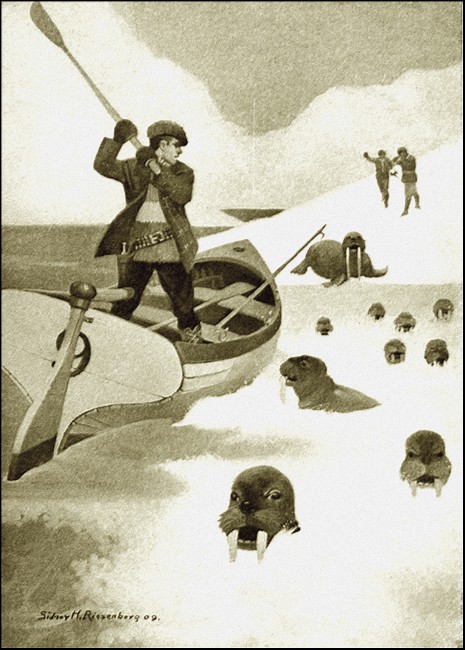

In this cleared position of the deck was an orderly array of cargo that the Chronicle reporter had referred to as "junk." In this "junk" were the crated sections of a small steamboat, a portable wood-burning boiler and an engine for the same; a rebuilt whaleboat carrying a powerful looking gasoline engine and two auxiliary masts of the Mackinac rig—unshipped, of course—and not less than twenty steel drums of gasoline, all housed beneath a board and canvas protecting covering.

Next to these, and familiar enough in appearance to the boys, stood the old oak casks for generating hydrogen gas. These had been forwarded on Ned's order from Clarkville, New Mexico, and were now ready for use once again. In the vicinity were the carboys of sulphuric acid and the sacks of iron filings to be used in making hydrogen gas. Apart and under a separate covering of tarpaulin were the boxes and crates containing Ned's and Alan's pride—the big balloon bag, its rigging, the aero-sledge and the light but powerful engines for the latter. "And what's this," asked Bob, indicating several large bundles of snowy duck canvas and a heap of cordage"—a circus tent?"

"Our balloon house," answered Ned. "We haven't the time to build a steel house, as Mr. Wellman did. But we've got to have protection to fill a balloon, if there is any wind. From the upper yards of the foremast and mizzenmast we are going to extend rope stays. From them we expect—if we are ever called on to inflate the balloon—to hang our four canvas walls. We'll lace them together at the corners as they are drawn aloft, and there's your canvas balloon house open at the top and snug as a chimney shaft on the sides."

Bob took a quick glance at the towering masts and fragile yards. Then he shook his head. "I don't mind ballooning," he exclaimed, "but excuse me from rigging up that contraption."

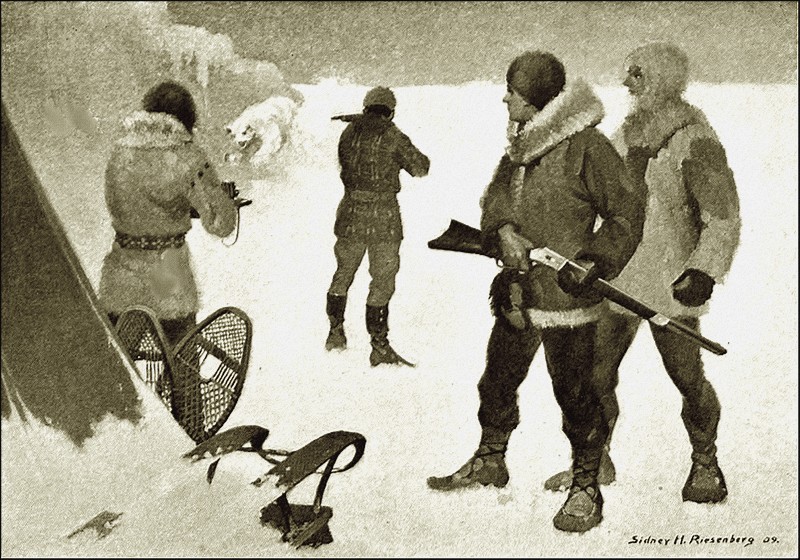

On the lower main deck, what had been the old dining saloon was now almost completely filled with goods that would answer as well for an extended hunting trip as for an Arctic voyage. There were provisions of varied kinds; preserved meats, vegetables in glass, flour, and sweets even in the form of confectionery. Three of the aft staterooms that had not been removed were crowded with ammunition and firearms. The latter included not only pocket and holster automatic revolvers of the latest patterns but an assortment of magazine express rifles and shot guns.

At sight of these the youthful investigators wondered what use Colonel Oje could find for his own assortment of gun cases, for that gentleman had in his own cabin a gun trunk, whose contents were a marvel.

Conveniently near, in the cargo space, were unopened boxes of heavy blankets, sleeping bags and felt boots. Two rooms were packed with flat pasteboard boxes labeled variously: Mackinac woolen coats; extra heavy shirts; woolen socks and stockings; woolen and deerskin mittens; moccasins and many other articles of winter apparel, most of them such as timber men in the Northwest or the voyageurs of the Canadian North wear.

Amidships, on this desk, next to the purser's office and the wireless outfit in what had been the "valuable baggage" room were dozens of cotton-encased boxes which, Mr. Wales, the first officer, explained, held "the most elaborate set of instruments" he had ever seen.

"I don't know that we will bother this room very much," remarked Ned. "We've got, under the berth in our stateroom, a good many more registering and measuring appliances than the old Cibola ever had and, goodness knows, we had more on her than we ever used."

"By the way," broke in Bob, "you don't name sledges do you?"

"Shackelton did, at the South Pole," answered Ned, soberly.

"What's the aero-sledge's name?"

"The White North."

"Dandy!" exclaimed Bob. "But say—what if she doesn't go to the 'white north'?"

The usual smile went out of Ned's face for a moment and a glint of determination seemed to dart from his half-closed eyes.

"She's got to," he answered.

The words had so much of force and thrill in them that both Alan and Bob looked up in astonishment. Ned had passed on.

"By cracky," whispered Alan, "I believe he'll make it a polar expedition of some kind."

"Sounds as if he had an idea or two," whispered Bob, "even if he is a hired man."

The adjoining room was a photographic shop—with everything ready for setting up; dark room equipment, cameras, tripods, flash-light apparatus and cases of plates and films.

"Here's where I live," exclaimed Bob, thinking of his own new personal outfit—two beautiful and powerful film cameras that he had brought aboard.

Ned was a few steps ahead. As he looked back he remarked, banteringly, as he pointed to the open door of the purser's office:

"I thought you referred to the wireless telegraph."

"Oh, I don't know," answered the reporter. "We newspaper fellows have to make ourselves handy at a good many things."

At the moment the remark had no particular significance to Ned and Alan. Later they understood.

In the bow on this deck was the crew's mess and bunks. In the stern, on the same deck and aft of the now cargo-crowded dining saloon were the colliers' bunks. The lower or cargo deck and the steamer's hold forward and astern of the engine room were packed with coal. Such was the Aleutian's burden.

Alan, in the afternoon, stood for a long time with his hands gripped on the idle wheel at the stern, and as the steamer lunged and sank, he leaned forward as if holding the steel hulk on its course. Bob, hanging over the taffrail, amused himself with the clicking log. Ned had disappeared. Later his two friends found him in the pilot house above the bridge. And, to their surprise, his companions found him firmly grasping the real wheel.

"Let's find the engineer and have a look at the engines," suggested Alan, anxious not to be wholly outdone by Ned. But Bob shook his head.

"Plenty of time coming for that," he answered. "I'm getting my sea legs and it's too fine out here. You go. With you in the engine room and Ned at the wheel I'll take the deck. I guess the three of us can run her all right."

In this manner the boys separated. Alan's stay in the engine room was not protracted. The heat and hot oil soon drove him out. On deck, although he made several circuits of the steamer, he could find no trace of Russell. Feeling a trifle shaky in his knees Alan went into his own stateroom for a nap.

Perhaps an hour and a half later he was aroused by the somewhat excited entrance of Bob and Ned.

"Get up," exclaimed Bob, laughing, "wake up. I've got it."

"Got it?" drawled Alan, half asleep. "Got what?"

"Get up. Turn out," added Ned. "Bob's seen Mr. Osborne."

This was better than a dash of cold water. Alan slipped off the berth like a fish.

"Did he tell?" he asked, breathlessly.

Bob laughed again and put a finger to his lip.

"Hist!" he whispered, stage-like. "Not so loud. Follow me."

Through the stateroom windows it could be seen that the raw breeze was turning into a foggy wind. When Bob insisted that he could talk only in the open air the three boys donned rain-coats and were soon on what they had already come to consider their part of the deck—the extreme stern of the steamer. Bob had accomplished something and he showed it. Pulling his cap down over his radiant face, he leaned proudly back against the rail.

"And so you went right into his stateroom, eh!" suggested Ned.

"I did," answered Bob slowly.

"And he told you?" added Alan whistling.

Bob nodded his head.

"Where?" exclaimed Ned, unable to longer control himself.

"What?" whispered Alan excitedly.

Bob extended his two dripping hands as if to hold back his questioner.

"That's my climax," he answered, "I've got to work it up to that. I'm going to tell you from the beginning."

"IT took all the courage I had, but I'd said I would. After you fellows disappeared I figured out my campaign. Persuading the Jap to act as a messenger I got out the cleanest card I had and sent it to Mr. Osborne's stateroom. The card had 'Kansas City Comet' on it. I had a notion that the representative of the press might have a chance.

"He sent word to come in. When I did so I found him standing by the table with a chart in his hand. Before I could begin he stopped me by saying in the nicest tone:"

"I'm glad to see you. Won't you be seated?"

"But my program was brevity—I've tried it before. I said:

"'I thank you. But it is only a moment I want, Mr. Osborne,' I explained, 'I asked to see you because I feel that my being on the Aleutian warrants some explanation. You lave been good enough to permit me to accompany you. I want to thank you for that—'"

"He interrupted me. 'We are honored to have a representative of the press as a guest.'

"I saw I had guessed right. So I hurried on after bowing my thanks.

"'And,' I continued, "'I want you to know that I appreciate the confidence you have placed in me. We all appreciate that, whatever the mission of your voyage may be, its purpose solely concerns you and your associates.'

"At this he shrugged his shoulders as if surprised. Then be again motioned to a chair and I took it, but I sat on the edge as if I had but a moment to stay—that's an old reportorial trick, you know—" added Bob. "'I hope,' I went on after we were both seated, 'you won't misunderstand me. But if I do not impress you as having sufficient loyalty to you and the voyage, I want you to ask me to withdraw from the expedition at Unalaska.'

"If I had any notion he was going to fall over himself to ask me to stay I got a chill right there."

"I told you he'd freeze you," interrupted Ned.

"Wait," added Bob. "He looked at me without any expression for a moment. Then he said:

"I have never yet been deceived by a reporter—and I have known many. Your profession is a sufficient guarantee of your character."

"Say," broke in Alan, throwing the accumulated water from his folded arms, "what's this? A book? Tell as how it came out! You'd got a fine call down from your city editor for all those 'says I' and 'says he.'"

Bob scowled. "I'm working into the story," he growled.

"You'll hear it quicker if you keep still. Now, where was I?"

"'Guarantee of your character,'" suggested Ned, laughing.

"Yes! Well, then I thanked him for that. Then he got down to tacks.

"'We asked you to come because we had use for you,' he went on. 'I see no reason to feel we have not made a wise choice. That is, unless you are averse to roughing it and hunting.'

"'Hunting?' I exclaimed. I suppose he saw he had gone too far, too.

"'Yes,' he went on almost at once, 'you know you are assigned to Colonel Oje.'

"'I reckon I was a little embarrassed.'

"'Yes, I know,' I stammered, 'but I didn't know it was to be hunting.'

"'He hopes to have the greatest hunting trip a sportsman ever made,' Mr. Osborne answered, as calmly and easily as if he wasn't telling a thing. 'Perhaps he has not yet spoken to you of his plans. He will probably seek an early opportunity to do so,' continued Mr. Osborne. 'He should do it before we reach the islands. You might not care to go on.'

"'I know Colonel Oje,' I answered in a hurry. 'He's the best shot in America. I'll be only too glad to help him in any way I can.'

"'In that event,' explained Mr. Osborne, 'I have no doubt you'll help take our little steamboat up the McKenzie River. I understand that that part of Northern Canada is the greatest big game region in the world—'"

"Then we're going shooting?" exclaimed Alan, dejectedly.

"One moment," interrupted Bob. "Some of us are."

"Up the McKenzie River?" added Ned quickly.

"Don't hurry me," pleaded Bob. "But I was just as excited, I guess, for Mr. Osborne went on and let the cat right out of the bag."

Ned and Alan crowded close in their excitement.

"He told it so naturally and easily that it seemed as if I knew it already," explained Bob.

"From Unalaska we are going to sail directly up through Bering Sea, into the Straits and into the Arctic Ocean—"

"Whoopee!" exclaimed Alan in aloud whisper. "I knew it!"

"Then we're going to head east and make for Herschel Island—"

"Where's that?" broke in Ned.

"That's where the Pacific steam whalers winter when they are caught in the North," explained Bob with a great show of erudition. "But there's nothing there except land and fresh water. And it lies off the month of the McKenzie River."

"And that's all?" broke in Alan ruefully. "What's the use of an aero-sledge there?"

Bob held out his hand, smiled, and went on.

"I'm the one who ought to feel disappointed," he continued. "Only I don't. Colonel Oje and I and some others are going ashore there and that's where I tell you good bye."

The other boys stepped back with no effort to conceal their astonishment.

"To say good bye?" broke in Alan again.

"That's the program. I can't give details but when we've killed caribou and musk ox, wood buffalo, elk, bear and deer to Colonel Oje's content we're going to get to civilization again by going on up the McKenzie River to Great Slave Lake and then by lakes and rivers I don't know to Edmonton in Canada, twenty-four hundred miles away."

"And the rest of us and the aero-sledge?" urged Alan, who did not yet realize the novelty and wonder of this daring and hazardous journey through the almost unexplored wilderness of Northern British America.

"That's what I wondered," continued Bob.

"And I didn't hesitate to ask. 'Do we all go with Colonel Oje?' I asked directly after I sort of got my senses.

"'We may remain a week at Herschel Island,' Mr. Osborne said, 'for that is where we meet our collier.' I was getting a little used to surprises now, but I suppose he saw that this, too, was news to me. So he added, 'I forwarded a cargo of coal there last summer in a steam whaler.' Then he told me where you fellows come in. 'We have not said anything of our plans,' he explained, 'as the expedition is a business secret. But,' he went on, 'there is no reason why you young gentlemen should not know now where you are going. Mr. Napier and Mr. Hope will remain with us. It is not unlikely that they may be of great assistance to Major Honeywell.'"

"I just sat and looked at him and said nothing. Then he got up and took down the big map he had rolled up. It was the northern section, of British America and the polar lands and seas next to it—"

"And that's where we go?" exclaimed Alan springing in front of the narrator.

"You are going to sail along the north end of America, south of Prince Albert Land and Banks Land until—"

"Until?" broke in Ned.

"Until you find a settlement of white Eskimos!" Ned and Alan drew back again as if struck.

"No North Pole?" quivered Alan.

"What do you want?" exclaimed Bob. "Didn't you hear me? White Eskimos, I said. That's your job while I'm pushing a wood-burner boat after musk ox."

"What's this mean?" put in Ned at last. "Is Mr. Osborne out after freaks? Who wants white Eskimos?"

"You will when you stop to think," exclaimed Bob, almost breathlessly. "But particularly Major Honeywell does."

"Oh, I see," muttered Ned with disappointment yet uppermost. "The ethnologist still. Having exhausted the south end of the continent he is now bound for the northern extreme. But who ever heard of white Eskimos?"

"I have; from Mr. Osborne. You remember the Sir John Franklin polar expedition? The one that lost over a hundred men? Well, some folks don't believe all those men died—at once. Mr. Osborne says there is reason to believe that some of those bold English explorers, after being beset in the ice for two winters, left their ships and made their way to Eskimo settlements."

"But that was long ago," put in Ned.

"In 1848," answered Bob, fresh with his new information. "They wouldn't be alive now, but their descendants might."

"I don't see yet where we come in with that sledge we figured on all winter to say nothing of the balloon," almost wailed Alan.

Bob ignored him. "As I understand it, Major Honeywell is taking advantage of Mr. Osborne's fortune and Colonel Oje's hunting project to see if he can't learn something about the Eskimos in this part of the world. I guess he's got an Eskimo fad," explained Bob. "Anyway his big hope is to push the Aleutian eastward along the British American shores as far as he can toward King William Land. That's where the Franklin runners were last seen. And on his way he's going to look into every Eskimo camp he sees in the hope of finding some traces of the descendants of the Franklin crews. Probably grandchildren if there are any," laughed Bob.

"Eskimos who have never been below the Arctic Circle talking English," exclaimed Ned in a low voice, as if talking to himself and entering at last partly into the secret dream of his friend, Major Honeywell. "White Eskimo boys and girls, perhaps," he went on to himself.

Alan cracked his heel against the side of the boat.

"So that's it," he almost sneered, "hunting deer from a steamboat and looking for half-civilized Eskimos with a spyglass. No wonder they made it a blind chase and bottled up their secret."

"Well," added Bob, after a moment, "I see you are both tickled to death. But that's the story. I told you I'd get it and I have. As far as I'm concerned I'm game—I'm satisfied."

Ned and Alan stood silent, their brows wrinkled.

"And I'll just say this," Bob continued, "from what I've seen of Mr. Osborne, if you fellows don't like your contract, I'll bet you he'll let you quit the boat at Unalaska and give you tickets back home besides. As for me, I'm going to stick."

NED looked up sharply as if he had something on his mind.

"I suppose that's what you call a clever piece of reportorial work?" he remarked.

"I should say not," answered Bob. "I don't believe I've yet referred to myself as 'clever'. But what's the matter with it? Doesn't it cover the case?"

"One moment," exclaimed Ned, with an unexpected smile. "You feel certain that the Aleutian has been outfitted to take Colonel Oje after musk ox and Major Honeywell after white Eskimos."

Bob smiled in turn.

"Want to hear it all over again?" was his only reply.

"No, I don't," said Ned. "I don't pretend to be much of an interviewer, but I'd like to ask you a question or two."

"Fire away!"

"When was the old Waldo sent to San Francisco from Boston?"

"A year ago, I believe," answered Bob, a little puzzled.

"Do you know when Mr. Osborne started his coal supply to Herschel Island?" continued Ned.

Alan had joined the two, curiously attentive.

"Since he sent it on one of the Pacific steam whaling vessels it must have started last spring," answered Bob, doubly puzzled.

"That's the way I figure it," remarked Ned.

"Now," he went on, "when did Mr. Osborne first meet Colonel Oje and Major Honeywell?"

"Why, on our way home from Denver last fall, you know that," was Bob's answer.

"That's why I'm wondering," exclaimed Ned. "Can you tell me just why Mr. Osborne bought a steamer, sent it all the way round South America and arranged to transport a cargo of coal nearly five thousand miles to accommodate men he did not know, never saw and never heard of until six months afterward?"

Bob's puzzled face turned into an icy stare. Then his chin dropped.

"I—I—say—what do you mean?" he faltered at last.

"I mean," said Ned, "that your friend, Mr. Osborne, isn't as easy as you think. I mean that you are smart enough, but that the gentleman who is engineering this trip is a little smarter."

"Don't you believe what he told me?" spluttered Bob, growing red in the face.

"Certainly," answered Ned, his smile broadening. "Every word of it. Only that isn't all. That's what I mean."

Bob could stand it no longer.

"Look here, Napier—" he began vehemently.

"I've looked," chuckled Ned. "And I see just what you'll see in a second. Were not the big things of this trip arranged for before Mr. Osborne ever heard of Major Honeywell or Colonel Oje? Tell me—weren't they?"

"That's certainly a fact," interrupted Alan.

Bob's chagrin was passing, and as the jovial young journalist saw that he had left out a link in his chain of reasoning he resumed his smile. Then he pulled himself together and laughed outright. He surrendered at once to the logic of the situation.

"I guess we'd better go in and think it over," he said at last. "We've been thinking Mr. Osborne was a sort of big, quiet, polar bear. I'll tell you what he is; he's a sharp-eyed fox."

Alan sighed.

"Between you fellows, where do I stand?" he interrupted. "First I'm up; then I'm down. Now I'm at sea."

At that moment Ned laid a hand on the arm of each of the other boys and started across the deck with them.

"I don't like to knock a good thing without offering something in its place," he began. "Let's go into our stateroom, get out of these wet togs, make ourselves comfortable and then I've got a little theory of my own."

Despite their protests he would say no more until the stateroom was reached. The chill of the later afternoon made the warmth of the spacious cabin grateful. Ned took from a rack a small package.

"I guess I'd better brace you fellows up a bit," he explained with a smile. "Here's a five-pound box of pretty fine candy. A friend gave it to me—"

"A friend," laughed Alan, glancing at the sweets. "Guess it was Sister Mary."

Ned colored. "Stuff your mouths full of it," he exclaimed, hurriedly, "for I don't want to be interrupted. My theory doesn't just fit in with Bob's, but it's a corker just the same."

"Is this going to be another 'says he' and 'says I' narrative," asked Alan, as the contents of a cream chocolate oozed over his lips and he threw himself on a berth. "If it is, tell it backwards. I'm getting sleepy."

"I'll wake you up," said Ned. "Here's the title of my tale: 'The Treasure Ship on the Ice.'" Alan rolled over and faced him, open-eyed. Bob nodded his head in unctuous approval.

"That's the stuff," he whispered, "I can see the sails of the White North headed toward it right now. Pray hasten thy tale."

"'The Treasure Ship on the Ice'," repeated Ned, squatting upon the floor after snapping on the electric light bulb, "or 'The Remarkable Adventures of Captain Thomas McKay, as related by Andrew Zenzencoff, Mariner.'"

"Say, Ned," interrupted Alan, springing up in his berth. "If this is a fairy tale I've had enough for one day. Excuse me," he added, turning toward Bob, "nothing personal."

"Shut up," exclaimed the latter, frowning. "Don't you know a good thing when you hear it?"

"Or," continued Ned, not heeding either, "making it plain for children, 'A Story told me this Afternoon by Andy Zenzencoff concerning our Skipper, Captain McKay.'"

"Who is Zenzencoff?" asked Alan.

"The wheelman on watch while I was in the wheel house," explained Ned.

"What's he know about Captain McKay?" continued the doubting Alan.

"That's really a part of the story," Ned replied. "But I'll anticipate a little. He is a Russian sailor who made a remarkable voyage with Captain McKay."

"How'd he get 'way over here?" went on the cross-examiner.

A pillow came banging from the upper berth and Bob's broad shoulders lunged over the side.

"Shut up, I tell you. What does that matter? It'll come out, maybe. Go on, Clark Russell," pleaded Bob.

"Go on?" laughed Ned. "Certainly, if the audience is seated at last. But I'm all in on the Clark Russell business already. What's coming now is just my own way of putting it."

"That's rough," was Alan's parting comment. "But remember the 'says he to me' business."

"Andy, the wheelman," began Ned, "is a Russian. He's been sailing in American waters in the Alaska trade from Seattle to Graham Island on a steamer commanded by Captain McKay. Fifteen years ago he was a sailor on a Russian whaler. I can't pronounce the name of his ship. After a winter at Bear Island south of Spitzbergen the whaler got out of the ice and reached Bergen in bad shape. Bergen is in Norway," explained Ned. "This was in the early summer. In port at Bergen was a Scotch whaler, the Lady of Dundee—"

Bob chuckled.

"Should a' been the Lass o' Dundee," he murmured. "But the other is good enough."

"On the Lady," continued Ned, "Captain McKay was then first mate. The captain's name doesn't matter because I can't remember it. The Lady was clearing for walrus and seals north of Nova Zembla and hoped to reach the new sealing grounds south of the Franz Joseph Islands away up on the eightieth parallel. Zenzencoff shipped. At least that's where he thought he was going. But, instead of making for the eightieth parallel, Zenzencoff says, the Lady of Dundee sailed west around the north end of Nova Zembla and on through oceans of ice, in which she was beset—"

"That's the word," interrupted Bob, "always 'beset' in polar work—never 'caught.'"

"In which she was caught for days at a time," continued Ned perversely, "and finally brought up when winter came on in the month of the Tamer River in Northern Siberia."

"You must spell it T-a-i-m-y-r," interrupted Bob again, "and it's the limit."

It was now Alan's turn.

"Just call me at the crisis," he drawled sleepily.

"Anyway," went on Ned, "that's where they were. Andy says the captain told the crew that they could walk home if they didn't like it. In their winter quarters Andy says he got to knew Mate McKay and to like him. When they broke out the next summer, instead of steering for Scotland they made east again. There was almost a mutiny because six men had died from scurry. But the captain's revolver and Mate McKay's smooth talk settled that. At least they kept things moving for six weeks and then the winter began to close in again.

"They hadn't made another port and they had fought drift ice until scurvy and hard work made things look blue. But the Lady was pushed on, no one knew where—of the crew at least—until it was plain that it meant another winter of walrus meat. Andy says he was scared himself to see how quiet the eight remaining men became and when they brought up at last at Great Liakhof Island 'way around on the other side of the world, he knew something was about to happen. Well, it did. From that island the ship was edged along north until it came to in a cove on another island—and he didn't say what that was," explained Ned, "only that it was one of several."

"I'll have to give the medal to you," exclaimed Alan suddenly, "Bob isn't in it for long-windedness."

"Come outside with me, Bob," said Ned, "and I'll finish."

As the two boys made toward the door Alan sprang in front of it.

"What happened then?" he exclaimed defiantly. "What's the point?"

"This Liakhof Island is one of the New Siberian group," explained Ned, turning to Bob. "I reckon you can guess what they were after."

"Mammoths?" answered Bob, with assurance.

"Their tusks, anyway," answered Ned, "and fossil ivory. Andy says it was then that he found out what they were going to do. This snow-covered island was off the mouth of the Yana River. McKay told him they expected, when the summer came again, to fill the Lady of Dundee with ivory—fossil ivory—but ivory just the same.

"Somewhere in that region the captain believed he could mine ivory. Oh, that isn't ridiculous," exclaimed Ned, turning to Alan who had sneered outright, "it has been found since then—mammoth tusks, walrus tusks, narwhal swords—whole beds of them. Where? I don't know. But I know Russia has been using that ivory for years and that some freak of nature put it there."

"Take it for granted," replied Alan, "and go on."

"This island—"

At that moment there was a tap on the stateroom door. Ned paused and threw it open. Just without was the cabin boy, Yoshina. He pointed to the table opposite. On this was a Russian tea samovar, from which steam was puffing, and at the table's side stood Captain McKay and Mr. Osborne.

"Tea is served," explained the Jap politely.

THE ceremony of drinking tea was prolonged by Mr. Osborne's leisurely actions. Captain McKay, damp from the rain, attacked the refreshment energetically. He consumed two full cups, using in each a slice of lemon.

"You are fond of Russian tea, Captain?" Mr. Osborne suggested.