High up, crowning the grassy summit of a swelling mount whose sides are wooded near the base with the gnarled trees of the primeval forest stands the old chateau of my ancestors. For centuries its lofty battlements have frowned down upon the wild and rugged countryside about, serving as a home and stronghold for the proud house whose honored line is older even than the moss-grown castle walls. These ancient turrets, stained by the storms of generations and crumbling under the slow yet mighty pressure of time, formed in the ages of feudalism one of the most dreaded and formidable fortresses in all France. From its machicolated parapets and mounted battlements Barons, Counts, and even Kings had been defied, yet never had its spacious halls resounded to the footsteps of the invader.

But since those glorious years, all is changed. A poverty but little above the level of dire want, together with a pride of name that forbids its alleviation by the pursuits of commercial life, have prevented the scions of our line from maintaining their estates in pristine splendor; and the falling stones of the walls, the overgrown vegetation in the parks, the dry and dusty moat, the ill-paved courtyards, and toppling towers without, as well as the sagging floors, the worm-eaten wainscots, and the faded tapestries within, all tell a gloomy tale of fallen grandeur. As the ages passed, first one, then another of the four great turrets were left to ruin, until at last but a single tower housed the sadly reduced descendants of the once mighty lords of the estate.

It was in one of the vast and gloomy chambers of this remaining tower that I, Antoine, last of the unhappy and accursed Counts de C—, first saw the light of day, ninety long years ago. Within these walls and amongst the dark and shadowy forests, the wild ravines and grottos of the hillside below, were spent the first years of my troubled life. My parents I never knew. My father had been killed at the age of thirty-two, a month before I was born, by the fall of a stone somehow dislodged from one of the deserted parapets of the castle. And my mother having died at my birth, my care and education devolved solely upon one remaining servitor, an old and trusted man of considerable intelligence, whose name I remember as Pierre. I was an only child and the lack of companionship which this fact entailed upon me was augmented by the strange care exercised by my aged guardian, in excluding me from the society of the peasant children whose abodes were scattered here and there upon the plains that surround the base of the hill. At that time, Pierre said that this restriction was imposed upon me because my noble birth placed me above association with such plebeian company. Now I know that its real object was to keep from my ears the idle tales of the dread curse upon our line that were nightly told and magnified by the simple tenantry as they conversed in hushed accents in the glow of their cottage hearths.

Thus isolated, and thrown upon my own resources, I spent the hours of my childhood in poring over the ancient tomes that filled the shadow haunted library of the chateau, and in roaming without aim or purpose through the perpetual dust of the spectral wood that clothes the side of the hill near its foot. It was perhaps an effect of such surroundings that my mind early acquired a shade of melancholy. Those studies and pursuits which partake of the dark and occult in nature most strongly claimed my attention.

Of my own race I was permitted to learn singularly little, yet what small knowledge of it I was able to gain seemed to depress me much. Perhaps it was at first only the manifest reluctance of my old preceptor to discuss with me my paternal ancestry that gave rise to the terror which I ever felt at the mention of my great house, yet as I grew out of childhood, I was able to piece together disconnected fragments of discourse, let slip from the unwilling tongue which had begun to falter in approaching senility, that had a sort of relation to a certain circumstance which I had always deemed strange, but which now became dimly terrible. The circumstance to which I allude is the early age at which all the Counts of my line had met their end. Whilst I had hitherto considered this but a natural attribute of a family of short-lived men, I afterward pondered long upon these premature deaths, and began to connect them with the wanderings of the old man, who often spoke of a curse which for centuries had prevented the lives of the holders of my title from much exceeding the span of thirty-two years. Upon my twenty-first birthday, the aged Pierre gave to me a family document which he said had for many generations been handed down from father to son, and continued by each possessor. Its contents were of the most startling nature, and its perusal confirmed the gravest of my apprehensions. At this time, my belief in the supernatural was firm and deep-seated, else I should have dismissed with scorn the incredible narrative unfolded before my eyes.

The paper carried me back to the days of the thirteenth century, when the old castle in which I sat had been a feared and impregnable fortress. It told of a certain ancient man who had once dwelled on our estates, a person of no small accomplishments, though little above the rank of peasant, by name, Michel, usually designated by the surname of Mauvais, the Evil, on account of his sinister reputation. He had studied beyond the custom of his kind, seeking such things as the Philosopher's Stone or the Elixir of Eternal Life, and was reputed wise in the terrible secrets of Black Magic and Alchemy. Michel Mauvais had one son, named Charles, a youth as proficient as himself in the hidden arts, who had therefore been called Le Sorcier, or the Wizard. This pair, shunned by all honest folk, were suspected of the most hideous practices. Old Michel was said to have burnt his wife alive as a sacrifice to the Devil, and the unaccountable disappearance of many small peasant children was laid at the dreaded door of these two. Yet through the dark natures of the father and son ran one redeeming ray of humanity; the evil old man loved his offspring with fierce intensity, whilst the youth had for his parent a more than filial affection.

One night the castle on the hill was thrown into the wildest confusion by the vanishment of young Godfrey, son to Henri, the Count. A searching party, headed by the frantic father, invaded the cottage of the sorcerers and there came upon old Michel Mauvais, busy over a huge and violently boiling cauldron. Without certain cause, in the ungoverned madness of fury and despair, the Count laid hands on the aged wizard, and ere he released his murderous hold, his victim was no more. Meanwhile, joyful servants were proclaiming the finding of young Godfrey in a distant and unused chamber of the great edifice, telling too late that poor Michel had been killed in vain. As the Count and his associates turned away from the lowly abode of the alchemist, the form of Charles Le Sorcier appeared through the trees. The excited chatter of the menials standing about told him what had occurred, yet he seemed at first unmoved at his father's fate. Then, slowly advancing to meet the Count, he pronounced in dull yet terrible accents the curse that ever afterward haunted the house of C—.

'May ne'er a noble of thy murd'rous line

Survive to reach a greater age than thine!'

spake he, when, suddenly leaping backwards into the black woods, he drew from his tunic a phial of colorless liquid which he threw into the face of his father's slayer as he disappeared behind the inky curtain of the night. The Count died without utterance, and was buried the next day, but little more than two and thirty years from the hour of his birth. No trace of the assassin could be found, though relentless bands of peasants scoured the neighboring woods and the meadowland around the hill.

Thus time and the want of a reminder dulled the memory of the curse in the minds of the late Count's family, so that when Godfrey, innocent cause of the whole tragedy and now bearing the title, was killed by an arrow whilst hunting at the age of thirty-two, there were no thoughts save those of grief at his demise. But when, years afterward, the next young Count, Robert by name, was found dead in a nearby field of no apparent cause, the peasants told in whispers that their seigneur had but lately passed his thirty-second birthday when surprised by early death. Louis, son to Robert, was found drowned in the moat at the same fateful age, and thus down through the centuries ran the ominous chronicle: Henris, Roberts, Antoines, and Armands snatched from happy and virtuous lives when little below the age of their unfortunate ancestor at his murder.

That I had left at most but eleven years of further existence was made certain to me by the words which I had read. My life, previously held at small value, now became dearer to me each day, as I delved deeper and deeper into the mysteries of the hidden world of black magic. Isolated as I was, modern science had produced no impression upon me, and I labored as in the Middle Ages, as wrapt as had been old Michel and young Charles themselves in the acquisition of demonological and alchemical learning. Yet read as I might, in no manner could I account for the strange curse upon my line. In unusually rational moments I would even go so far as to seek a natural explanation, attributing the early deaths of my ancestors to the sinister Charles Le Sorcier and his heirs; yet, having found upon careful inquiry that there were no known descendants of the alchemist, I would fall back to occult studies, and once more endeavor to find a spell, that would release my house from its terrible burden. Upon one thing I was absolutely resolved. I should never wed, for, since no other branch of my family was in existence, I might thus end the curse with myself.

As I drew near the age of thirty, old Pierre was called to the land beyond. Alone I buried him beneath the stones of the courtyard about which he had loved to wander in life. Thus was I left to ponder on myself as the only human creature within the great fortress, and in my utter solitude my mind began to cease its vain protest against the impending doom, to become almost reconciled to the fate which so many of my ancestors had met. Much of my time was now occupied in the exploration of the ruined and abandoned halls and towers of the old chateau, which in youth fear had caused me to shun, and some of which old Pierre had once told me had not been trodden by human foot for over four centuries. Strange and awesome were many of the objects I encountered. Furniture, covered by the dust of ages and crumbling with the rot of long dampness, met my eyes. Cobwebs in a profusion never before seen by me were spun everywhere, and huge bats flapped their bony and uncanny wings on all sides of the otherwise untenanted gloom.

Of my exact age, even down to days and hours, I kept a most careful record, for each movement of the pendulum of the massive clock in the library told off so much of my doomed existence. At length I approached that time which I had so long viewed with apprehension. Since most of my ancestors had been seized some little while before they reached the exact age of Count Henri at his end, I was every moment on the watch for the coming of the unknown death. In what strange form the curse should overtake me, I knew not; but I was resolved at least that it should not find me a cowardly or a passive victim. With new vigor I applied myself to my examination of the old chateau and its contents.

It was upon one of the longest of all my excursions of discovery in the deserted portion of the castle, less than a week before that fatal hour which I felt must mark the utmost limit of my stay on earth, beyond which I could have not even the slightest hope of continuing to draw breath that I came upon the culminating event of my whole life. I had spent the better part of the morning in climbing up and down half ruined staircases in one of the most dilapidated of the ancient turrets. As the afternoon progressed, I sought the lower levels, descending into what appeared to be either a mediaeval place of confinement, or a more recently excavated storehouse for gunpowder. As I slowly traversed the niter-encrusted passageway at the foot of the last staircase, the paving became very damp, and soon I saw by the light of my flickering torch that a blank, water-stained wall impeded my journey. Turning to retrace my steps, my eye fell upon a small trapdoor with a ring, which lay directly beneath my foot. Pausing, I succeeded with difficulty in raising it, whereupon there was revealed a black aperture, exhaling noxious fumes which caused my torch to sputter, and disclosing in the unsteady glare the top of a flight of stone steps.

As soon as the torch which I lowered into the repellent depths burned freely and steadily, I commenced my descent. The steps were many, and led to a narrow stone-flagged passage which I knew must be far underground. This passage proved of great length, and terminated in a massive oaken door, dripping with the moisture of the place, and stoutly resisting all my attempts to open it. Ceasing after a time my efforts in this direction, I had proceeded back some distance toward the steps when there suddenly fell to my experience one of the most profound and maddening shocks capable of reception by the human mind. Without warning, I heard the heavy door behind me creak slowly open upon its rusted hinges. My immediate sensations were incapable of analysis. To be confronted in a place as thoroughly deserted as I had deemed the old castle with evidence of the presence of man or spirit produced in my brain a horror of the most acute description. When at last I turned and faced the seat of the sound, my eyes must have started from their orbits at the sight that they beheld.

There in the ancient Gothic doorway stood a human figure. It was that of a man clad in a skull-cap and long mediaeval tunic of dark color. His long hair and flowing beard were of a terrible and intense black hue, and of incredible profusion. His forehead, high beyond the usual dimensions; his cheeks, deep- sunken and heavily lined with wrinkles; and his hands, long, claw-like, and gnarled, were of such a deadly marble-like whiteness as I have never elsewhere seen in man. His figure, lean to the proportions of a skeleton, was strangely bent and almost lost within the voluminous folds of his peculiar garment. But strangest of all were his eyes, twin caves of abysmal blackness, profound in expression of understanding, yet inhuman in degree of wickedness. These were now fixed upon me, piercing my soul with their hatred, and rooting me to the spot whereon I stood.

At last the figure spoke in a rumbling voice that chilled me through with its dull hollowness and latent malevolence. The language in which the discourse was clothed was that debased form of Latin in use amongst the more learned men of the Middle Ages, and made familiar to me by my prolonged researches into the works of the old alchemists and demonologists. The apparition spoke of the curse which had hovered over my house, told me of my coming end, dwelt on the wrong perpetrated by my ancestor against old Michel Mauvais, and gloated over the revenge of Charles Le Sorcier. He told how young Charles has escaped into the night, returning in after years to kill Godfrey the heir with an arrow just as he approached the age which had been his father's at his assassination; how he had secretly returned to the estate and established himself, unknown, in the even then deserted subterranean chamber whose doorway now framed the hideous narrator, how he had seized Robert, son of Godfrey, in a field, forced poison down his throat, and left him to die at the age of thirty-two, thus maintaining the foul provisions of his vengeful curse. At this point I was left to imagine the solution of the greatest mystery of all, how the curse had been fulfilled since that time when Charles Le Sorcier must in the course of nature have died, for the man digressed into an account of the deep alchemical studies of the two wizards, father and son, speaking most particularly of the researches of Charles Le Sorcier concerning the elixir which should grant to him who partook of it eternal life and youth.

His enthusiasm had seemed for the moment to remove from his terrible eyes the black malevolence that had first so haunted me, but suddenly the fiendish glare returned and, with a shocking sound like the hissing of a serpent, the stranger raised a glass phial with the evident intent of ending my life as had Charles Le Sorcier, six hundred years before, ended that of my ancestor. Prompted by some preserving instinct of self-defense, I broke through the spell that had hitherto held me immovable, and flung my now dying torch at the creature who menaced my existence. I heard the phial break harmlessly against the stones of the passage as the tunic of the strange man caught fire and lit the horrid scene with a ghastly radiance. The shriek of fright and impotent malice emitted by the would-be assassin proved too much for my already shaken nerves, and I fell prone upon the slimy floor in a total faint.

When at last my senses returned, all was frightfully dark, and my mind, remembering what had occurred, shrank from the idea of beholding any more; yet curiosity over-mastered all. Who, I asked myself, was this man of evil, and how came he within the castle walls? Why should he seek to avenge the death of Michel Mauvais, and how bad the curse been carried on through all the long centuries since the time of Charles Le Sorcier? The dread of years was lifted from my shoulder, for I knew that he whom I had felled was the source of all my danger from the curse; and now that I was free, I burned with the desire to learn more of the sinister thing which had haunted my line for centuries, and made of my own youth one long-continued nightmare. Determined upon further exploration, I felt in my pockets for flint and steel, and lit the unused torch which I had with me.

First of all, new light revealed the distorted and blackened form of the mysterious stranger. The hideous eyes were now closed. Disliking the sight, I turned away and entered the chamber beyond the Gothic door. Here I found what seemed much like an alchemist's laboratory. In one corner was an immense pile of shining yellow metal that sparkled gorgeously in the light of the torch. It may have been gold, but I did not pause to examine it, for I was strangely affected by that which I had undergone. At the farther end of the apartment was an opening leading out into one of the many wild ravines of the dark hillside forest. Filled with wonder, yet now realizing how the man had obtained access to the chateau, I proceeded to return. I had intended to pass by the remains of the stranger with averted face but, as I approached the body, I seemed to hear emanating from it a faint sound, as though life were not yet wholly extinct. Aghast, I turned to examine the charred and shrivelled figure on the floor.

Then all at once the horrible eyes, blacker even than the seared face in which they were set, opened wide with an expression which I was unable to interpret. The cracked lips tried to frame words which I could not well understand. Once I caught the name of Charles Le Sorcier, and again I fancied that the words 'years' and 'curse' issued from the twisted mouth. Still I was at a loss to gather the purport of his disconnnected speech. At my evident ignorance of his meaning, the pitchy eyes once more flashed malevolently at me, until, helpless as I saw my opponent to be, I trembled as I watched him.

Suddenly the wretch, animated with his last burst of strength, raised his piteous head from the damp and sunken pavement. Then, as I remained, paralyzed with fear, he found his voice and in his dying breath screamed forth those words which have ever afterward haunted my days and nights. 'Fool!' he shrieked, 'Can you not guess my secret? Have you no brain whereby you may recognize the will which has through six long centuries fulfilled the dreadful curse upon the house? Have I not told you of the great elixir of eternal life? Know you not how the secret of Alchemy was solved? I tell you, it is I! I! I! that have lived for six hundred years to maintain my revenge, for I am Charles Le Sorcier!'

The horrible conclusion which had been gradually intruding itself upon my confused and reluctant mind was now an awful certainty. I was lost, completely, hopelessly lost in the vast and labyrinthine recess of the Mammoth Cave. Turn as I might, in no direction could my straining vision seize on any object capable of serving as a guidepost to set me on the outward path. That nevermore should I behold the blessed light of day, or scan the pleasant bills and dales of the beautiful world outside, my reason could no longer entertain the slightest unbelief. Hope had departed. Yet, indoctrinated as I was by a life of philosophical study, I derived no small measure of satisfaction from my unimpassioned demeanor; for although I had frequently read of the wild frenzies into which were thrown the victims of similar situations, I experienced none of these, but stood quiet as soon as I clearly realized the loss of my bearings.

Nor did the thought that I had probably wandered beyond the utmost limits of an ordinary search cause me to abandon my composure even for a moment. If I must die, I reflected, then was this terrible yet majestic cavern as welcome a sepulcher as that which any churchyard might afford, a conception which carried with it more of tranquillity than of despair.

Starving would prove my ultimate fate; of this I was certain. Some, I knew, had gone mad under circumstances such as these, but I felt that this end would not be mine. My disaster was the result of no fault save my own, since unknown to the guide I had separated myself from the regular party of sightseers; and, wandering for over an hour in forbidden avenues of the cave, had found myself unable to retrace the devious windings which I had pursued since forsaking my companions.

Already my torch had begun to expire; soon I would be enveloped by the total and almost palpable blackness of the bowels of the earth. As I stood in the waning, unsteady light, I idly wondered over the exact circumstances of my coming end. I remembered the accounts which I had heard of the colony of consumptives, who, taking their residence in this gigantic grotto to find health from the apparently salubrious air of the underground world, with its steady, uniform temperature, pure air, and peaceful quiet, had found, instead, death in strange and ghastly form. I had seen the sad remains of their ill-made cottages as I passed them by with the party, and had wondered what unnatural influence a long sojourn in this immense and silent cavern would exert upon one as healthy and vigorous as I. Now, I grimly told myself, my opportunity for settling this point had arrived, provided that want of food should not bring me too speedy a departure from this life.

As the last fitful rays of my torch faded into obscurity, I resolved to leave no stone unturned, no possible means of escape neglected; so, summoning all the powers possessed by my lungs, I set up a series of loud shoutings, in the vain hope of attracting the attention of the guide by my clamor. Yet, as I called, I believed in my heart that my cries were to no purpose, and that my voice, magnified and reflected by the numberless ramparts of the black maze about me, fell upon no ears save my own.

All at once, however, my attention was fixed with a start as I fancied that I heard the sound of soft approaching steps on the rocky floor of the cavern.

Was my deliverance about to be accomplished so soon? Had, then, all my horrible apprehensions been for naught, and was the guide, having marked my unwarranted absence from the party, following my course and seeking me out in this limestone labyrinth? Whilst these joyful queries arose in my brain, I was on the point of renewing my cries, in order that my discovery might come the sooner, when in an instant my delight was turned to horror as I listened; for my ever acute ear, now sharpened in even greater degree by the complete silence of the cave, bore to my benumbed understanding the unexpected and dreadful knowledge that these footfalls were not like those of any mortal man. In the unearthly stillness of this subterranean region, the tread of the booted guide would have sounded like a series of sharp and incisive blows. These impacts were soft, and stealthy, as of the paws of some feline. Besides, when I listened carefully, I seemed to trace the falls of four instead of two feet.

I was now convinced that I had by my own cries aroused and attracted some wild beast, perhaps a mountain lion which had accidentally strayed within the cave. Perhaps, I considered, the Almighty had chosen for me a swifter and more merciful death than that of hunger; yet the instinct of self-preservation, never wholly dormant, was stirred in my breast, and though escape from the on-coming peril might but spare me for a sterner and more lingering end, I determined nevertheless to part with my life at as high a price as I could command. Strange as it may seem, my mind conceived of no intent on the part of the visitor save that of hostility. Accordingly, I became very quiet, in the hope that the unknown beast would, in the absence of a guiding sound, lose its direction as had I, and thus pass me by. But this hope was not destined for realization, for the strange footfalls steadily advanced, the animal evidently having obtained my scent, which in an atmosphere so absolutely free from all distracting influences as is that of the cave, could doubtless be followed at great distance.

Seeing therefore that I must be armed for defense against an uncanny and unseen attack in the dark, I groped about me the largest of the fragments of rock which were strewn upon all parts of the floor of the cavern in the vicinity, and grasping one in each hand for immediate use, awaited with resignation the inevitable result. Meanwhile the hideous pattering of the paws drew near. Certainly, the conduct of the creature was exceedingly strange. Most of the time, the tread seemed to be that of a quadruped, walking with a singular lack of unison betwixt hind and fore feet, yet at brief and infrequent intervals I fancied that but two feet were engaged in the process of locomotion. I wondered what species of animal was to confront me; it must, I thought, be some unfortunate beast who had paid for its curiosity to investigate one of the entrances of the fearful grotto with a life-long confinement in its interminable recesses. It doubtless obtained as food the eyeless fish, bats and rats of the cave, as well as some of the ordinary fish that are wafted in at every freshet of Green River, which communicates in some occult manner with the waters of the cave. I occupied my terrible vigil with grotesque conjectures of what alteration cave life might have wrought in the physical structure of the beast, remembering the awful appearances ascribed by local tradition to the consumptives who had died after long residence in the cave. Then I remembered with a start that, even should I succeed in felling my antagonist, I should never behold its form, as my torch had long since been extinct, and I was entirely unprovided with matches. The tension on my brain now became frightful. My disordered fancy conjured up hideous and fearsome shapes from the sinister darkness that surrounded me, and that actually seemed to press upon my body. Nearer, nearer, the dreadful footfalls approached. It seemed that I must give vent to a piercing scream, yet had I been sufficiently irresolute to attempt such a thing, my voice could scarce have responded. I was petrified, rooted to the spot. I doubted if my right arm would allow me to hurl its missile at the oncoming thing when the crucial moment should arrive. Now the steady pat, pat, of the steps was close at hand; now very close. I could hear the labored breathing of the animal, and terror-struck as I was, I realized that it must have come from a considerable distance, and was correspondingly fatigued. Suddenly the spell broke. My right hand, guided by my ever trustworthy sense of hearing, threw with full force the sharp-angled bit of limestone which it contained, toward that point in the darkness from which emanated the breathing and pattering, and, wonderful to relate, it nearly reached its goal, for I heard the thing jump, landing at a distance away, where it seemed to pause.

Having readjusted my aim, I discharged my second missile, this time most effectively, for with a flood of joy I listened as the creature fell in what sounded like a complete collapse and evidently remained prone and unmoving. Almost overpowered by the great relief which rushed over me, I reeled back against the wall. The breathing continued, in heavy, gasping inhalations and expirations, whence I realized that I had no more than wounded the creature. And now all desire to examine the thing ceased. At last something allied to groundless, superstitious fear had entered my brain, and I did not approach the body, nor did I continue to cast stones at it in order to complete the extinction of its life. Instead, I ran at full speed in what was, as nearly as I could estimate in my frenzied condition, the direction from which I had come. Suddenly I heard a sound or rather, a regular succession of sounds. In another Instant they had resolved themselves into a series of sharp, metallic clicks. This time there was no doubt. It was the guide. And then I shouted, yelled, screamed, even shrieked with joy as I beheld in the vaulted arches above the faint and glimmering effulgence which I knew to be the reflected light of an approaching torch. I ran to meet the flare, and before I could completely understand what had occurred, was lying upon the ground at the feet of the guide, embracing his boots and gibbering. despite my boasted reserve, in a most meaningless and idiotic manner, pouring out my terrible story, and at the same time overwhelming my auditor with protestations of gratitude. At length, I awoke to something like my normal consciousness. The guide had noted my absence upon the arrival of the party at the entrance of the cave, and had, from his own intuitive sense of direction, proceeded to make a thorough canvass of by-passages just ahead of where he had last spoken to me, locating my whereabouts after a quest of about four hours.

By the time he had related this to me, I, emboldened by his torch and his company, began to reflect upon the strange beast which I had wounded but a short distance back in the darkness, and suggested that we ascertain, by the flashlight's aid, what manner of creature was my victim. Accordingly I retraced my steps, this time with a courage born of companionship, to the scene of my terrible experience. Soon we descried a white object upon the floor, an object whiter even than the gleaming limestone itself. Cautiously advancing, we gave vent to a simultaneous ejaculation of wonderment, for of all the unnatural monsters either of us had in our lifetimes beheld, this was in surpassing degree the strangest. It appeared to be an anthropoid ape of large proportions, escaped, perhaps, from some itinerant menagerie. Its hair was snow-white, a thing due no doubt to the bleaching action of a long existence within the inky confines of the cave, but it was also surprisingly thin, being indeed largely absent save on the head, where it was of such length and abundance that it fell over the shoulders in considerable profusion. The face was turned away from us, as the creature lay almost directly upon it. The inclination of the limbs was very singular, explaining, however, the alternation in their use which I bad before noted, whereby the beast used sometimes all four, and on other occasions but two for its progress. From the tips of the fingers or toes, long rat-like claws extended. The hands or feet were not prehensile, a fact that I ascribed to that long residence in the cave which, as I before mentioned, seemed evident from the all-pervading and almost unearthly whiteness so characteristic of the whole anatomy. No tail seemed to be present.

The respiration had now grown very feeble, and the guide had drawn his pistol with the evident intent of despatching the creature, when a sudden sound emitted by the latter caused the weapon to fall unused. The sound was of a nature difficult to describe. It was not like the normal note of any known species of simian, and I wonder if this unnatural quality were not the result of a long continued and complete silence, broken by the sensations produced by the advent of the light, a thing which the beast could not have seen since its first entrance into the cave. The sound, which I might feebly attempt to classify as a kind of deep-tone chattering, was faintly continued.

All at once a fleeting spasm of energy seemed to pass through the frame of the beast. The paws went through a convulsive motion, and the limbs contracted. With a jerk, the white body rolled over so that its face was turned in our direction. For a moment I was so struck with horror at the eyes thus revealed that I noted nothing else. They were black, those eyes, deep jetty black, in hideous contrast to the snow-white hair and flesh. Like those of other cave denizens, they were deeply sunken in their orbits, and were entirely destitute of iris. As I looked more closely, I saw that they were set in a face less prognathous than that of the average ape, and infinitely less hairy. The nose was quite distinct. As we gazed upon the uncanny sight presented to our vision, the thick lips opened, and several sounds issued from them, after which the thing relaxed in death.

The guide clutched my coat sleeve and trembled so violently that the light shook fitfully, casting weird moving shadows on the walls.

I made no motion, but stood rigidly still, my horrified eyes fixed upon the floor ahead.

The fear left, and wonder, awe, compassion, and reverence succeeded in its place, for the sounds uttered by the stricken figure that lay stretched out on the limestone had told us the awesome truth. The creature I had killed, the strange beast of the unfathomed cave, was, or had at one time been a MAN!!!

In the spring of 1847, the little village of Ruralville was thrown into a state of exitement by the arrival of a strange brig in the harbour. It carried no flag, and everything about it was such as would exite suspicion. It had no name. Its captain was named Manuel Ruello. The exitement increased however when John Griggs dissapeared from his home. This was Oct. 4. On Oct. 5 the brig was gone.

The brig, in leaving, was met by a U.S. frigate and a sharp fight ensued. When over, they* missed a man named Henry Johns.

*(The Frigate.)

The brig continued its course in the direction of Madagascar. Upon its arrival the natives fled in all directions. When they came together on the other side of the island, one was missing. His name was Dahabea.

At length it was decided that something must be done. A reward of £5,000 was offered for the capture of Manuel Ruello. Then startling news came: a nameless brig was wrecked on the Florida Keys.

A ship was sent to Florida, and the mystery was solved. In the excitement of the fight they would launch a submarine boat and take what they wanted. There it lay, tranquilly rocking on the waters of the Atlantic when someone called out "John Brown has dissapeared." And sure enough John Brown was gone.

The finding of the submarine boat, and the dissapearance of John Brown, caused renewed exitement amongst the people, when a new discovery was made. In transcribing this discovery it is necessary to relate a geographical fact. At the North Pole there exists a vast continent composed of volcanic soil, a portion of which is open to explorers. It is called "No-Mans Land."

In the extreme southern part of No-Mans Land, there was found a hut, and several other signs of human habitation. They promptly entered, and, chained to the floor, lay Griggs, Johns, and Dahabea. They, upon arriving in London, separated, Griggs going to Ruralville, Johns to the frigate, and Dahabea to Madagascar.

But the mystery of John Brown was still unsolved, so they kept strict watch over the port at No-Mans Land, and when the submarine boat arrived, and the pirates, one by one, and headed by Manuel Ruello, left the ship, they were met by a rapid fire. After the fight Brown was recovered.

Griggs was royally received at Ruralville, and a dinner was given in honour of Henry Johns, Dahabea was made King of Madagascar, and Brown was made Captain of his ship.

In the Spring of 1847, the little village of Ruralville was thrown into a state of excitement by the landing of a strange brig in the harbour. It carried no flag, and no name was painted on its side, and everything about it was such as would excite suspicion. It was from Tripoli, Africa, and the captain was named Manuel Ruello. The excitement increased, however; when John Griggs (the magnate of the villiage) suddenly disappeared from his home. This was the night of October 4th—On October 5th the brig left.

It was 8 bells on the U.S. frigate Constitution when Commander Farragut sighted a strange brig to the westward. It carried no flag, and no name was painted on its side, and everything about it was such as would excite suspicion. On hailing, it put up the Pirates Flag. Farragut ordered a gun fired and no sooner did he fire, than the pirate ship gave them a broadside. When the fight was over Commander Farragut missed one man named Henry F. Johns.

It was summer on the Island of Madagascar. And natives were picking corn, when one cried "Companions! I sight a ship! with no flag and with no name printed on the side and with everything about it such as would excite suspicion!" And the natives fled in all directions. When they came together on the other side of the island one was missing. His name was Dahabea.

At length it was decided something must be done. Notes were compared. Three abductions were found to have taken place. [The] dissapearance of John Griggs, Henry John, and Dahabea, were recalled. Finally advertisements were issued offering £5000 reward for the capture of Manuel Ruello, ship, prisoners, and crew. Then exciting news reached London! An unknown brig with no name was wrecked off The Florida Keys in America!

The people hurried to Florida and behold— A steel spindle-shaped object lay placidly on the water beside the shattered wreck of the brig. "A submarine boat!" shouted one "Yes!" shouted another. "The mystery is cleared," said a wise-looking man. "In the excitement of the fight they launch the submarine boat and take as many as they wish, unseen. And—" "John Brown has disappeared!" shouted a voice from the deck. Sure enough John Brown was gone!

The Finding of the submarine boat and the dissapearance of John Brown caused renewed excitement among the people, and a new discovery was made. In relating this discovery it is necessary to relate a geographical fact:— At the North Pole there is supposed to exist a vast continent composed of volcanic soil: a portion is open to travellers and explorers but it is barren and unfruitful, and thus absolutely impassable. It is called "No-Mans Land."

In the extreme southern part of No-Mans Land there was found a wharf and a hut etc., and every sign of former human habitation. A rusty door-plate was nailed to the hut inscribed in old English "M. Ruello." This, then, was the home of Michael Ruello. the house brought to light a note-book belonging to John Griggs, and the log of the Constitution taken from Henry Johns, and the Madagascar reaper belong to Dahabea.

When about to leave, they Observed a spring on the side of the hut. They pressed it.—A hole appeared in the side of the hut which they promptly entered. They were in a subterranean cavern; the beach ran down to the edge of a black, murky, sea; on the sea lay a dark oblong object—viz another submarine boat which they entered. There, bound to the cabin floor lay Griggs, Johns, and Dahabea, all alive and well. They, when arriving in London, separated, Griggs going to Ruralville, Johns, to the Constitution and Dahabea to Madagascar.

But the mystery of John Brown lay still unsolved. So they kept strict watch over the port at No-Man's Land, hoping the submarine boat would arrive. At length, however, it did arrive bearing with it John Brown. They fixed upon the 5th of October for the attack. They ranged along the shore and formed bodies. Finally, one by one, and headed by Manuel Ruello, the pirates left the boat. They were (to their astonishment) met by a rapid fire.

The Pirates were at length defeated and a search was made for Brown. At length he (the aforesaid Brown) was found. John Gregg was royally received at Ruralville and a dinner was [given in honour of Henry Johns].

Dahabea was made King of Madagascar, and Manuel Ruello was executed at Newgate Prison.

It was noon in the Little village of Mainville, and a sorrowful group of people were standing around the Burns's Tomb. Joseph Burns was dead. (when dying, he had given the following strange orders:—"Before you put my body in the tomb, drop this ball onto the floor, at a spot marked "A"." he then handed a small golden ball to the rector.) The people greatly regretted his death. After The funeral services were finished, Mr Dobson (the rector) said, "My friends, I will now gratify the last wishes of the deceased. So saying, he descended into the tomb. (to lay the ball on the spot marked "A") Soon the funeral party Began to be impatient, and after a time Mr. Cha's. Greene (the Lawyer) descended to make a search. Soon he came up with a frightened face, and said, "Mr Dobson is not there"!

It was 3.10 o'clock in ye afternoone whenne The door bell of the Dobson mansion rang loudly, and the servant on going to the door, found an elderly man, with black hair, and side whiskers. He asked to see Miss Dobson. Upon arriving in her presence he said, "Miss Dobson, I know where your father is, and for £10,000 I will restore him. My name is Mr. Bell." "Mr. Bell," said Miss Dobson, "will you excuse me from the room a moment?" "Certainly". replied Mr Bell. In a short time she returned, and said, "Mr. Bell, I understand you. You have abducted my father, and hold him for a ransom"

It was 3.20 o'clock in the afternoon when the telephone bell at the North End Police Station rang furiously, and Gibson, (the telephone Man) Inquired what was the matter,

"Have found out about fathers dissapearance"! a womans voice said. "Im Miss Dobson, and father has been abducted, "Send King John!" King John was a famous western detective. Just then a man rushed in, and shouted, "Oh! Terrors! Come to the graveyard!"

Now let us return to the Dobson Mansion. Mr Bell was rather taken aback by Miss Dobson's plain speaking, but when he recovered his speech he said, "Don't put it quite so plain, Miss Dobson, for I—" He was interrupted by the entrance of King John, who with a brace of revolvers in his hands, barred all egress by the doorway. But quicker than thought Bell sprang to a west window,—and jumped.

Now let us return to the station house. After the exited visitor had calmed somewhat, he could tell his story straighter. He had seen three men in the graveyard shouting "Bell! Bell! where are you old man!?" and acting very suspiciously. He then followed them, and they entered The Burns's Tomb! He then followed them in and they touched a spring at a point marked "A" and then Dissapeared". "I wish king John were here", Said Gibson, "What's your name,"? "John Spratt". replied the visitor.

Now let us return To the Dobson Mansion again:—King John was utterly confounded at the Sudden movement of Bell, but when he recovered from his surprise, his first thought was of chase. Accordingly, he started in pursuit of the abductor. He tracked him down to the R. R. Station and found to his dismay that he had taken the train for Kent, a large city toward the south, and between which and Mainville there existed no telegraph or telephone. The train had Just Started!

The Kent train started at 10.35, and about 10.36 an exited, dusty, and tired man* rushed into the Mainville hack. office and said to a negro hackman who was standing by the door—"If you can take me to Kent in 15 minutes I will give you a dollar". "I doan' see how I'm ter git there", said the negro "I hab'n't got a decent pair of hosses an' I hab—" "Two Dollars"! shouted The Traveller. "All right," said the Hackman.

* King John.

It was 11 o'clock at Kent, all of the stores were closed but one, a dingy, dirty, little shop, down at the west end. It lay between Kent Harbour, & the Kent & Mainville R.R. In the Front room a shabbily dressed person of doubtful age was conversing with a middle aged woman with gray haire, "I have agreed to do the job, Lindy," he said, "Bell will arrive at 11.30 and the carraige is ready to take him down to the wharf, where a ship for Africa sails to-nighte".

"But If King John were to come?" queried "Lindy." "Then we'd get nabbed, an' Bell would be hung" Replied The man. Just then a rap sounded at the door "Are you Bell"? inquired Lindy "Yes" was the response, "And I caught the 10.35 and King John got Left, so we are all right". At 11.40 the party reached The Landing, and saw a ship Loom up in the darkness. "The Kehdive" "of Africa" was painted on the hull, and Just as they were to step on board, a man stepped forward in the darkness and said "John Bell, I arrest you in the Queen's name"! It was King John.

The daye of The Trial had arrived, and a crowd of people had gathered around the Little grove, (which served for a court house in summer) To hear the trial of John Bell on the charge of kid-napping. "Mr. Bell," said the judge "what is the secret of the Burns's tomb" "I well tell you this much" said Bell, "If you go into the tomb and touch a certain spot marked "A" you will find out" "Now where is Mr Dobson"? queried the judge, "Here"! said a voice behind them, and The figure of Mr Dobson HIMSELF loomed up in the doorway. "How did you get here"!&c was chorused. "'Tis a long story," said Dobson.

"When I went down into the tomb," Said Dobson, "Everything was darkness, I could see nothing. but Finally I discerned the letter "A" printed in white on the onyx floor, I dropped the ball on the Letter, and immediately a trap-door opened and a man sprang up. It was this man, here," (he said (pointing at Bell, who stood Trembling on the prisoner's docke) "and he pulled me down into a brilliantly lighted, and palatial apartment where I have Lived until to-day. One day a young man rushed in and exclaimed "The secret Is revealed!" and was gone. He did not see me. Once Bell left his key behind, and I took the impression in wax, and the next day was spent in filing keys to fit the Lock. The next day my key fitted. and the next day (which is to-day) I escaped."

"Why did the late J. Burns, ask you to put the ball there"? (at "A"?) queried the Judge? "To get me into trouble" replied Dobson "He, and Francis Burns, (his brother) have plotted against me for years, and I knew not, in what way they would harm me". "Sieze Francis Burns"! yelled the Judge.

Francis Burns, and John Bell, were sent to prison for life. Mr Dobson was cordially welcomed by his daughter, who, by the way had become Mrs King John. "Lindy" and her accomplice were sent to Newgate for 30 days as aidors and abbettors of a criminal escape.

"Now be good children," said Mrs. Lee "While I am away and don't get into mischief." Mr. and Mrs. Lee were going off for the day and to leave the two children John, 10 years old, and Alice 2 years old. "Yes," replied John.

As Soon as the elder Lees were away the younger Lees went down [into the] cellar and began to rummage among the rubbish. Little Alice leaned against the wall, watching John. As John was making a boat of barrel staves the Little girl gave a piercing cry as the bricks behind her crumbled away. He rushed up to her and lifted her out screaming loudly. As soon as her screams subsided she said "the wall went away."

John went up and saw that there was a passage he said to the little girl "lets come and see what this is."

"Yes," she said, [and] they entered the place. They could stand up [in] it. The passage was farther than they could see. John went back upstairs and went to the kitchen drawer and got two candles and some matches and then they went back to the cellar passage. The two once more entered. There was plastering on the walls, ceiling and floor. Nothing was visible but a box. This was for a seat. Nevertheless they examined it and found it to contain nothing. They walked on farther and pretty soon the plastering left off and they were in a cave. Little Alice was frightened at first but at her brothers assurance that it was "all right" she allayed her fears. soon they came to a small box, which John took up and carried. Within pretty soon they came on a boat. In it were two oars. He dragged it with difficulty along with him. Soon they found the passage came to an abrupt stop. He pulled the obstacle away and to his dismay water rushed in in torrents. John was an expert swimmer and long breather. He had just taken a breath, so he tried to rise, but with the box and his sister he found it quite impossible. Then he caught sight of the boat rising [and] he grasped it...

The next he knew he was on the surface, clinging tightly to the body of his sister and the mysterious box. He could not imagine how the water got in but a new peril menaced them. If the water continued rising it would rise to the top. suddenly a thought presented itself. He could shut off the water. He speedily did this and, lifting the now lifeless body of his sister into the boat, he himself clim[b]ed in and sailed down the passage. It was gruesome and uncanny [and] absolutely dark. His candle being put out by the flood and a dead body lying near, he did not gaze about him but rowed for his life. When he did look up he was floating in his own cellar. He quickly rushed up stairs with the body to find his parents had come home. He told them the story.

The funeral of Alice occupied so much time that John quite forgot about the box;but when they did open it they found it to be a solid gold chunk worth about $10,000—enough to pay for anything but the death of his sister.

"Heave to, there’s something floating to the leeward." the speaker was a short stockily built man whose name was William Jones. he was the captain of a small cat boat in which he and a party of men were sailing at the time the story opens.

"Aye aye sir," answered John Towers and the boat was brought to a stand still Captain Jones reached out his hand for the object which he now discerned to be a glass bottle "Nothing but a rum flask that the men on a passing boat threw over," he said but from an impulse of curiosity he reached out for it. it was a rum flask and he was about to throw it away when he noticed a piece of paper in it. He pulled it out and on it read the following

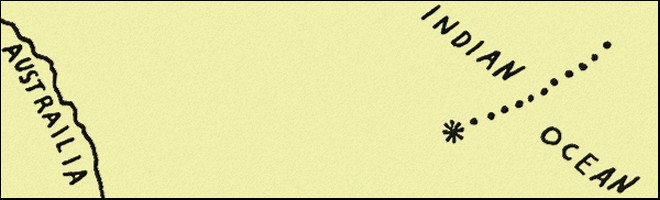

Jan 1, 1864

I am John Jones who writes this letter my ship is fast sinking with a

treasure on board I am where it is marked * on the enclosed chart...

Captain Jones turned the sheet over, and the other side was a chart.

On the edge were written these words: "dotted lines represent course we took."

"Towers," Said Capt. Jones exitedly "read this." Towers did as he was directed "I think it would pay to go," said Capt. Jones "do you?" "Just as you say," replied Towers. "We’ll charter a schooner this very day," said the exited captain "All right," said Towers so they hired a boat and started off guided by the dotted lines of they chart. In four weeks the reached the place where directed and the divers went down and came up with an iron bottle they found in it the following lines scribbled on a piece of brown paper

Dec 3, 1880

Dear Searcher excuse me for the practical joke I have played on you but it

serves you right to find nothing for your foolish act—

"Well it does," said Capt Jones "go on..."

However I will defray your expenses to & from the place you found your bottle I think it will be $2,500.00, so that amount you will find in an iron box. I know where you found the bottle because I put this bottle here & the iron box & then found a good place to put the second bottle. Hoping the enclosed money will defray your expenses some, I close—Anonymus."

"I’d like to kick his head off," said Capt Jones "Here diver go and get the $2,500.00 in a minute the diver came up bearing an iron box inside it was found $2,500.00 It defrayed their expenses but I hardly think that they will ever go to a mysterious place as directed by a mysterious bottle.