RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

HARD man was Ralph Strang, seventh Karl of Beden, seventy years of age on his last birthday, but still upright as a dart, with hair white as snow, but with the devilry of youth still sparkling in his keen dark eyes. He was, indeed, able to follow the hounds with the best of us, and there were few men, even among the youngest and most hot-headed of our riders, who cared to follow him over all the jumps he put his horse at.

When I first came to Upstanway as a doctor I thought it strange that so good a sportsman should be so unpopular. As a rule a man can do pretty well anything in a sporting county so long as he rides straight to hounds. But before I had been in the place a month I attended him after a fall in the hunting-field, and I saw that a man like that would be unpopular even if he gave all his goods to the poor and lived the life of St. Francis of Assisi. Not that he was harsh or even unpleasant, but he had the knack of making one feel foolish and uncomfortable, and there was something in the expression of his eyes that made one unable to look him squarely in the face. His manners, indeed, were perfect, and he retained all the old-world courtliness which seems to have been permanently abandoned by this generation, but I could not help feeling that underneath all his politeness and even hospitality lay a solid substratum of contempt.

It was doubtless this impression which had earned him his unpopularity, for I never heard a single one of his enemies lay anything definite to his charge beyond the fact that his elder brother had died in a lunatic asylum, and that Lord Beden was in some vague way held responsible for this unfortunate event.

But it was not until Lord Beden purchased a 12-h.p. "Napier" motor-car that the villagers really began to consider him possessed of a devil. And certainly his spirit of devilry seemed to have found a worthy plaything in that grey mass of snorting machinery, which went through the lanes like a whirlwind, enveloped in a cloud of dust, and scattering every living thing close back against the hedges as a steamer dashes the waves against the banks of a river. I had often heard people whisper that he bore a charmed life in the hunting-field, and that another and better man would have been killed years ago; and be certainly carried the same spirit of dash and foolhardiness, and also the same good fortune, into a still more dangerous pursuit.

It was the purchase of this car that brought me into closer contact with him. I had had some experience of motors, and he was sufficiently humble to take some instructions from me, and also to let me accompany him on several occasions. At first I drove the car myself, and tried to inculcate a certain amount of caution by example, but after the third lesson, he knew as much about it as I did, and, resigning the steering-gear into his hands, I took my place by his side with some misgivings.

I must confess that he handled it splendidly. The man had a wonderful nerve, and when an inch to one side or the other would probably have meant death his keen eye never made a mistake and his hand on the wheel was as steady as a rock. This inspired confidence, and though the strain on my nerves was considerable, I found after a time a certain pleasurable excitement in these rides. And it was excitement, I can tell you. No twelve miles an hour for Lord Beden, no precautionary brakes down-hill, no wide curves for corners. He rode, as he did to hounds, straight and fast. Sometimes we had six inches to spare, but never more, and as often as not another half inch would have shot us both out of the car. We always seemed to come round a sharp corner on two wheels. It was certainly exhilarating. But there was something about it I did not quite like. I don't think I was physically afraid, but I recalled certain stories about Lord Beden's mad exploits in the hunting-field, and it almost seemed to me as though he might be purposely riding for a fall.

Then all at once my invitations to ride with him ceased. I thought at first that I had offended him, but I could think of no possible cause of offence; and, besides, his manner towards me had not changed in any way, and I dined with him more than once at Beden Hall, where he was as courteous and irritating as usual. However, he offered no explanation, and I certainly did not intend to ask for one. I watched him narrowly when we talked about the motor, but he made no mystery about his rides. I noticed, however, that he looked older and more xare-worn, and that his dark eyes burned now with an almost unnatural brilliancy.

I met him two or three times on the road when I was going my rounds in the trap, and he appeared to be driving his machine more furiously and fearlessly than ever. I was almost glad that his invitations had ceased. Strangely enough, I always encountered him on the same road, one which led straight to Oxminster, a town about twenty miles away.

One evening, however, late in August, while I was finishing my dinner in solitude, I heard a familiar hum and rattle along the road in the distance. In less than a minute I saw the flash of bright lamps through my open window and heard the jar of a brake.

Then there was a ring at the bell and Lord Beden was announced.

"Good evening, Scott," he said, taking off his glasses. "Lovely night, isn't it? Would you care to come for a ride?" He looked very pale, and was covered with dust from head to foot.

"Would you care to come for a ride?"

"A ride, Lord Beden?" I replied, thoughtfully. "Well, I hardly know what to say. Will you have some coffee and a cigar?"

He nodded assent and sat down. I poured him out some coffee, and noticed that his hand shook as he raised the cup to his lips. But driving a motor-car at a rapid rate might easily produce this effect. Then I handed him a cigar and lit one myself.

"Rather late for a ride, isn't it?" I said, after a slight pause.

"Not a bit, not a bit," he answered, hastily. "It is as bright as day and the roads clear of traffic. Come, it will do you good. We can finish our cigars in the car."

"Yes," I replied, thoughtfully, "or at any rate the draught will finish them for us."

"Look here, Scott," he continued, in a lower voice, leaning over the table and looking me straight in the eyes, "I particularly want you to come. In fact, you must come—to oblige me. I want you to see something which I have seen. I am a little doubtful of its actual existence."

I looked at him sharply. His voice was cold and quiet, but his eyes were certainly a bit too bright. I should say that he was in a state of intense excitement, yet with all his nerves well under control. I laughed a little uneasily.

"Very well, Lord Beden," I replied, rising from my chair. "I will come. But you will excuse me saying that you don't look well to-night I think you are rather overdoing this motor business. It shakes the system up a good deal, you know."

"I am not well, Scott," he said. "But you cannot cure me."

I said no more, and left the room to put on my glasses and an overcoat.

We set off through the village at about ten miles an hour. It was a glorious night and the moon shone clear in the sky, but I noticed a bank of heavy black clouds in the west, and thought it not unlikely that we should have a thunderstorm. The atmosphere had been suffocating all day, and it was only the motion of the car that created the cool and pleasant breeze which blew against our faces.

When we came to the church we turned sharp to the right on to the Oxminster Road.

It ran in a perfectly straight white line for three miles, then it began to wind and ascend the Oxbourne Hills, finally disappearing in the darkness of some woods which extend for nearly five miles over the summit in the direction of Oxminster.

"Where are we going to?" I asked, settling myself firmly in my seat.

"Oxminster," he replied, rather curtly. "Please keep your eyes open and tell me if you see anything on the road."

As he spoke he pulled the lever farther towards him and the great machine shot forward with a sudden plunge which would have unseated me if I had not been prepared for something of the sort. We quickly gathered up speed: hedges and trees went past us like a flash; the dust whirled up into the moonlight like a silver cloud, and before five minutes had elapsed we were at the foot of the hills and were tearing up the slope at almost the same terrific pace.

As we ascended the foliage began to thicken and close in upon us on either side; then the moon disappeared, and only our powerful lamps illuminated the darkness ahead of us. The car was a magnificent hill-climber, but the gradient soon became so steep that the pace slackened down to about eight miles an hour. Lord Beden had not spoken a word since he told me where we were going to, but he had kept his eyes steadily fixed on the broad circle of light in front of the car. I began to find the silence and darkness oppressive, and, to say the truth, was not quite comfortable in my own mind about my companion's sanity. I took off my glasses and tried to pierce the darkness on either side. The moon filtered through the trees and made strange shadows in the depths of the woods, but there was nothing else to be seen, and ahead of us there was only a white streak of road disappearing into blackness. Then suddenly my companion let go of the steering-gear with one hand and clutched me by the arm. "Listen, Scott!" he cried; "do you hear it?"

I listened attentively, and at first heard nothing but the throb of the motor and a faint rustling among the trees as a slight breeze began to stir through the wood. Then I noticed that the beat of the piston was not quite the same as usual. It sounded jerky and irregular, faint and loud alternately, and I had an idea that it had considerably quickened in speed.

"I hear nothing, Lord Beden," I replied, "except that the engine sounds a little erratic. It ought not to make so much fuss over this hill."

"If you listen more carefully," he said, "you will understand. That sound is the beat of two pistons, and one of them is some way off."

I listened again. He was right There was certainly another engine throbbing in the distance.

"I cannot see any lights," I answered, looking first in front of us and then into the darkness behind. "But it's another motor, I suppose. It does not appear to me to be anything out of the way."

He did not reply, but replaced his hand on the steering gear and peered anxiously ahead. I began to feel a bit worried about him. It was strange that he should get so excited about the presence of another motor-car in the neighbourhood. I was not reassured either when, in re-arranging the rug about my legs, I touched something hard in his pocket I passed my fingers lightly over it, and had no doubt whatever that it was a revolver. I began to be sorry I had come. A revolver is not a necessary tool for the proper running of a motor-car.

We were nearly at the top of the hill now, and still in the shadow of the trees. The road here runs for more than a mile along the summit before it begins to descend, and half-way along the level another road crosses it at right angles, leading one way down a steep slope to Little Stanway, and the other along the top of the Oxbourne Hills to Kelston and Rutherton, two small villages some miles away on the edge of the moors.

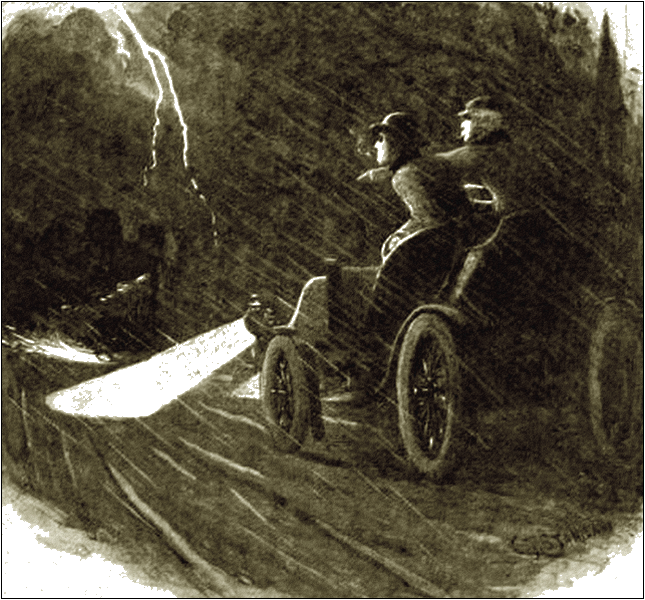

We had scarcely reached the level when a few heavy drops of rain began to fall, and, looking up, I saw that the moon was no longer visible through the branches overhead. A minute later there was a low roll of thunder in the distance, and for an instant the scenery ahead of us flashed bright and faded into darkness. I turned up the collar of my coat.

The car was now moving almost at full speed, but to my surprise, before we had gone a quarter of a mile, Lord Beden slowed it down and finally brought it to a full stop with the brake. Then he appeared to be listening attentively for something, but the rising wind and pouring rain had begun to make an incessant noise among the trees, and the thunder had become more loud and continuous. I strained my sense of hearing to the utmost, but I could hear nothing beyond the sounds of the elements.

"What is the matter?" I queried, impatiently. "Are we going to stop here?"

"Yes," he replied, curtly. "That is to say, if you have no objection. There is a certain amount of shelter."

I drew a cigar from my pocket and, after several attempts, managed to light it. To say the truth, I was in hopes that we should go no farther. The downward descent, three-quarters of a mile ahead of us, was about one in ten, and I did not feel much inclined to let my companion take me down a hill of that sort.

Then, for a few seconds, the rustling of the wind and pattering of the rain ceased among the trees, and once more I could distinctly hear the thud, thud, thud of an engine. It might have been a motor-car, but it certainly sounded to me more like the noise a traction engine would make. As we listened the sound came nearer and nearer and appeared to be on our left, still some distance down the hill. Then the storm broke out again with fresh fury, and we could hear nothing else. Lord Beden pulled the lever towards him and we ran slowly forward until we were within thirty yards of the cross-roads, when he again brought the machine to a standstill.

The noise had become much louder now, and was even audible above the roar of the wind and rain. It certainly came from somewhere on our left. I looked down through the trees, and thought I saw a faint red glow some way down the hill. Lord Beden saw it too, and pointed to it with a trembling hand.

"Looks like a fire in the wood," I said, carelessly. I did not very much care what it was.

"Don't be a fool," he replied, sharply. "Can't you see it's moving?"

Yes, he was right. It was certainly moving, and in a few seconds it was hidden by a thicker mass of foliage. I did not, however, see anything very noticeable about it. It was evidently coming up the road to our left, and was probably a belated traction engine returning home from the reaping. I was more than ever convinced of my companion's insanity and wished that I was safe at home. I had half a mind to get off the car and walk, but he had by now managed to infect me with some of his own fear and excitement, and I did not quite fancy being left with no swifter mode of progression than my feet.

The thumping sound came nearer and nearer, and, as we heard it more distinctly, was even more suggestive of a traction engine. Then I saw a red light through the trees like the glow of a furnace, and not more than fifty yards away from us. My companion laid his left hand on the lever and stared intently at the corner.

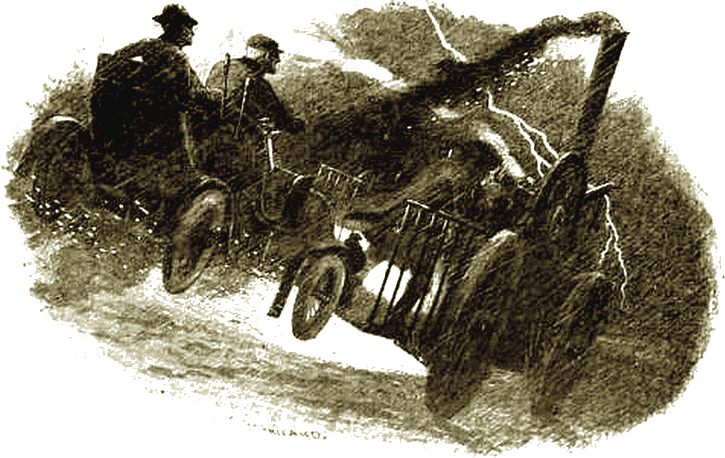

Then a rather peculiar thing happened. Whatever it was that had been lumbering slowly up the hill like a gigantic snail suddenly shot across the road in front of us like a streak of smoke and flame, and through the trees to our right I could see the red glow spinning up the road to Kelston at over thirty miles an hour.

"It suddenly shot across the road in front of us.

Almost simultaneously Lord Beden pulled down the lever and I instinctively clutched the seat with both hands. We shot forward, took the corner with about an inch to spare between us and the ditch, and dashed off along the road in hot pursuit But the red glow had got at least a quarter of a mile's start, and I could not see what it proceeded from. A flash of lightning, however, showed a dark mass flying before us in a cloud of smoke. It looked something like a large waggon with a chimney sticking out of it, and sparks streamed out of the back of it until they looked like the tail of a comet.

"What the deuce is it?" I said.

"You'll see when we come up to it," the Earl answered, between his teeth. "We shall go faster in a few minutes."

We were, however, going quite fast enough for me, and though I have ridden on many motors since, and occasionally at a greater speed. I shall never forget that ride along the Kelston Raid. The powerful machine beneath us trembled as though it were going to fall to pieces, the rain lashed our faces like the thongs of a whip, the thunder almost deafened us, the lightning first blinded us with its flashes and then left us in more confusing darkness, and, to crown all, a dense volume of smoke poured from the machine in front and hid the light of our own lamps. It would be hard to imagine worse conditions for a motor ride, and a man who could keep a steady hand on the steering-gear under circumstances like these was a man indeed. I should not have cared to try it, even in the daytime. But Lord Beden's luck was with him still, and we moved as though guided by some unseen hand.

"You will find a small lever by your side, Scott," he said, after a long pause. "Pull it towards you until it gives a click. It is an invention of iny own."

I found the handle and, following out his instructions, saw the arc of light from our lamps shoot another fifty yards ahead, leaving the ground immediately in front of the car in darkness. We had gained considerably. The light just impinged on the streaming tail of sparks.

"At last!" my companion muttered. "He has always had half a mile's start before, and the oil has given out before I could catch him. But he cannot escape us now."

"What is it, Lord Beden?"

"I am glad you see it," he replied. "I thought before to-night that it was a fancy of my brain."

"Of course I see it," I said, sharply. "I am not blind. But what is it?"

He did not answer, but a flash of lightning showed me his face, and I did not repeat the question.

Mile after mile we spun along the lonely country road, but never gaining another inch. We dashed through Kelston like a streak of light. It was fortunate that all the inhabitants were in bed. Then we shot out on to a road leading across the open moor, which stretches from here to the sea, twenty miles away, and I remembered that eight miles from Kelston there was a deep descent into the valley of the Stour, and it was scarcely possible that we could escape destruction. I quickly made up my mind to overpower Lord Beden and gain control of the machine.

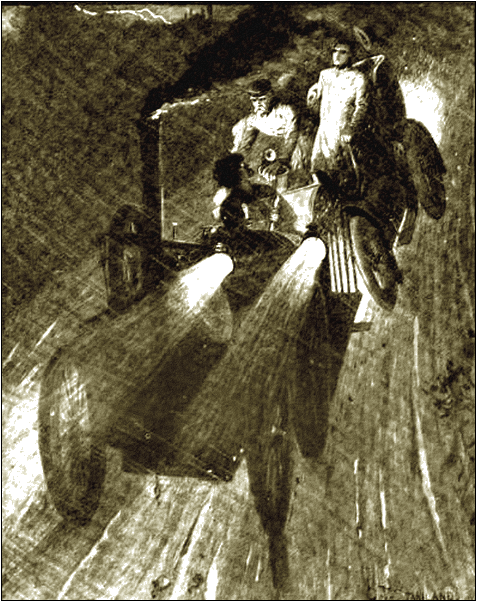

Then we suddenly began to sweep down a long and gentle gradient, and second after second our speed increased until the arc of light shone on the machine ahead of us, and I could see what manner of thing it was that we pursued.

It was, I suppose, a kind of motor-car, but unlike anything I had ever seen before, and bearing no more resemblance to a modern machine than a bone-shaker of twenty years ago does to the modern "free-wheel." It appeared to be built of iron, and was painted a dead black. In the fore-part of the structure a 5-foot fly-wheel spun round at a terrific speed, and various bars and beams moved rapidly backwards and forwards. The chimney was quite 10ft. in height, and poured out a dense volume of smoke. On a small platform behind, railed in by a stout iron rail, stood a tall man with his back to us. His dark hair, which must have reached nearly to his shoulders, streamed behind him in the wind. In each hand he grasped a huge lever, and he was apparently gazing steadily into the darkness before him, though it seemed to me that he might just as well have shut his eyes, for the machine had no lamps, and the only light in the whole concern streamed out from the half-open furnace door.

Then, to my amazement, I saw the man take his hands off the levers and coolly proceed to shovel coal into the roaring fire. I held my breath, expecting to see the flying mass of iron shoot off the side of the road and turn head over heels down the sloping grass. But nothing happened. The machine apparently required no guidance, and proceeded on its way as smoothly and swiftly as before.

I took hold of my companion's arm and called his attention to this somewhat strange circumstance. He only laughed.

"Look at the smoke," he cried. "That is rather strange too."

I looked up and saw it pouring over our heads in a long straight cloud, but I did not notice anything odd about it, and I said so.

"Can you smell it?" he continued. I sniffed, and noticed for the first time that there had been no smell of smoke at all, though in the earlier part of the journey we had been half blinded with it. I began to feel uncomfortable. There was certainly something unusual about the machine in front of us, and I came to the conclusion that we had had about enough of this kind of sport.

"I think we will go back, Lord Beden," I remarked, pleasantly, moving one hand towards the lever.

"You will go back to perdition, Scott," he answered, quietly. "If you meddle with me we shall be smashed to pieces. We are going forty miles an hour, and if you distract my attention for a single instant I won't answer for the consequences."

I felt the truth of what he said, and put my hand ostentatiously in my pocket. It was quite evident that I couldn't interfere with him, and equally evident that if we went on as we were going now we should be dashed to pieces. My only hope was that we should speedily accomplish whatever mad purpose Lord Beden had in his mind, although by now I began to think that he had no other object than suicide. The valley of the Stour was only two miles off.

But we had been gaining inch by inch, down the slope, and were now not more than thirty yards from the machine in front of us. Showers of sparks whirled into our faces, and I kept one arm before my eyes. I soon found, however, that, for some reason or other, the sparks did not burn my skin, and I was able to resume a more comfortable position and study the occupant of the car.

His figure somehow seemed strangely familiar to me, and I tried hard to recollect where I had seen those square shoulders and long, lean limbs before. I wished I could see the man's face, for I was quite certain that I should recognise it. But he never looked back, and appeared to be absolutely unconscious of our presence so close behind him.

Nearer we crept, and still nearer, until our front wheels were not more than 10 ft. from-the platform. The glow of the furnace bathed my companion's face in crimson light, and the figure of the man in front of us stood out like a black demon toiling at the eternal fires.

"Be careful, Lord Beden," I cried. "We shall be into it."

He turned to me with a smile of triumph, and I thought I saw the light of madness in his eyes.

"Do you know what I am going to do?" he said, in a low voice, putting his lips close to my ear. "I am going to break it to bits. We have a little speed in hand yet, and when, we get to the slope of the Stour Valley I shall break the cursed thing to bits."

"For Heaven's sake," I cried, "put the brake on, Lord Beden. Are you mad?" and I gripped him by the arm. He shook my hand off, and I clung to my seat with every muscle of my body strained to the utmost, for as I spoke there was a flash of lightning, and I saw the road dipping, dipping, dipping, and far below the gleam of water among dark trees, and on the height above a large building with many spires and towers. I idly called to mind that it was the Rockshire County Asylum.

Our speed quickened horribly, and the car began to sway from side to side. I saw my companion pull the lever an inch nearer to him and grip the steering-wheel with both hands. Then suddenly the road seemed to fall away beneath us; we sprang off the ground and dropped downward and forward like a stone flung from a precipice. We were going to smash clean through the machine in front of us.

"We sprang off the ground and dropped downward and forward.

For five seconds I held my breath, only awaiting the awful

crash of splintering wood and iron and the shock that would fling

us fifty feet from our seats. But we only touched the ground with

a sickening thud an inch behind the other machine, and then a

wonderful thing happened. We began to slowly pierce the rail and

platform in front of us, until the man seemed to be almost

touching our feet, and at last I saw his face—a wild, dark

face with madness in the eyes, and the face of Lord Beden, as I

had seen a portrait of him in Beden Hall taken thirty years

ago.

My companion rose on his seat and grappled with his own likeness, but he seemed to be only clutching the air, and neither car nor occupant appeared to have any tangible substance. Steadily and silently we bored our way clean through the machine, inch by inch, foot by foot: through the blazing furnace, through the framework of the boiler, through bolt and bar and stanchion, through whirring fly-wheel and pulsing shaft and piston, until there was nothing beyond us but the dip of the white road, and, looking back, I saw the whole dark mass running behind our back wheels.

Steadily and silently we bored our way clean through the machine.

Lord Beden was still standing and tearing at the air with his

fingers. Our car was running without guidance, and I sprang to

the steering-wheel and reversed the lever, but it was too late.

We struck something at the side of the road and the whole machine

made a leap from the ground. There was a rush of air, an awful

shock and crash, and then—darkness!

A WEEK afterwards in the hospital they told me Lord Beden

was dead. He had fallen on a large piece of scrap-iron by the

road-side, and nearly every bone in his body had been broken. I

myself had had a miraculous escape by falling into a thick clump

of gorse, and had got off with a broken arm and dislocated

collarbone, but I was not able to get about for two months. I

said nothing of what had happened, and the accident required but

little explanation. Motor-car accidents are common enough,

especially on slopes like that of the Stour Valley.

When I was able to get about, however, I visited the scene of the disaster. A friend of mine, one of the doctors at the County Lunatic Asylum, called for me and drove me over to the place. The smash had occurred nearly half-way down the hillside, close to a ruined shed. The ground was covered with gorse and bracken, but here and there huge pieces of rusty iron were scattered about. Some of them were sharp and brown and ugly, but many were overgrown with creeping convolvulus. They looked as if they had once been parts of some great machine.

"A curious coincidence," said my companion, as we drove away from the place.

"What do you mean?"

"I have been told," he continued, "that thirty years ago this old shed was used by the late Karl's elder brother. He was a mechanical genius, and they say that his efforts to work out some particular invention in a practical form drove him off his head. He was allowed to have this place as a workshop, and, under the supervision of two keepers, worked on his invention till the day of his death. It was thought that perhaps he would recover his reason if he ever accomplished the task. But in some mysterious way his plans were stolen from him no fewer than three times, and after the third time the poor fellow lost heart and destroyed himself. I have heard it whispered by one of my colleagues up yonder that the late Karl was not altogether ignorant of these thefts, but this is probably only gossip. All the fragments of iron you saw lying about were parts of the machine. Heaven knows what it was."

I did not venture any suggestion on this point, but I think I could have done so.