RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Argosy All-Story Weekly, 25 June 1921

with first part of "A Self-Made Thief"

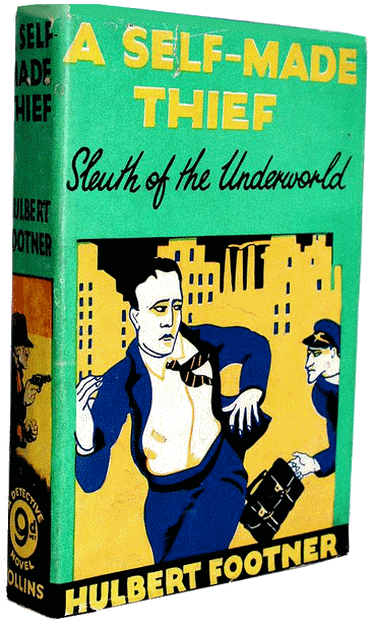

"A Self-Made Thief," Collins, London, 1927

"A Self-Made Thief," Collins, London, 1934, Reprint

IN the little card-room upstairs at the staid old Chronos Club on Gramercy Park a heated argument was going on. It was late on a night something like two years ago, and a long succession of refreshments from the bar downstairs was, without doubt, contributing to the heat. Heberdon, Spurway, Hanwell and Nedham, excellent fellows all, and good friends, had become involved in a discussion which had nothing to do with the game of bridge, and the cards were now lying unheeded on the table, while the players scowled and shook their fingers at each other, and otherwise went through the absurd pantomime of gentlemen annoyed with each other.

"You don't know what you're talking about!"

"Oh, I don't, don't I? Do you?"

"You talk as if you were the fount of all wisdom, and we were humble worshippers at the shrine."

"Your metaphors are mixed."

"Give us credit for some sense, Frank."

"I will, when you show any."

And so on. It appeared not to be a battle royal, but a case of three against one, Heberdon being the one. He was making certain asseverations on the subject of crime and criminals which the others violently and scornfully combated. Heberdon was a lawyer in his early thirties, a good-looking man of a pale, correct and regular cast of features, and of a demeanour exact and punctilious to match. He appeared to be the calmest of the quartet, but it was a calmness more apparent than real; he had his features under better control, that was all.

Like most men of his type, his cold and inscrutable exterior concealed an unbounded egoism and a mule like obstinacy. Opposition put him in a cold fury contradict him often enough, and he would go to any lengths to justify himself. This weakness of character was well known to his friends, and in the beginning they had had no object, save to amuse themselves by baiting him, but in doing so, as is not infrequently the case, they had lost their own tempers—all about nothing.

It had started innocently enough. Heberdon, shuffling the cards, had remarked in accents of scorn, "I see the police have got Corby."

"Who's Corby?" Spurway had asked. Spurway was a pink and portly stockbroker. His ideas were few, but he repeated them often. He was the noisiest of Heberdon's opponents.

"The hold-up man who got six thousand from a customer of the Eastern Trust Company three days ago."

Heberdon's ideas on the subject of crime were a source of diversion to his friends. Spurway had winked at the others. "What do you care?" he asked.

"Nothing," was the indifferent reply. "Only, one hates to see such a display of foolishness. Why, he got clean away with his six thousand without leaving a clue. Six thousand for, maybe, three minutes' work! How long do we have to sweat for six thousand, working honestly?"

"Oh, well, I guess honest work's easiest in the end," Spurway had remarked virtuously.

"It is, if you're a born fool," said Heberdon tartly.

"If he left no clue, how did they land him?" asked Nedham idly. Nedham was also a lawyer, but of a very different type from Heberdon, a large, blond, slow and reliable sort of fellow, with eyes set wide apart in his head and a benignant cast in one of them; in short, a man cut out by nature to be the trusted repository of wills and family skeletons.

"The conceited fool wrote a letter to the newspapers, bragging of his crime."

"Corby a friend of yours?" Hanwell had asked dryly. He was an advertising man, dark, slender and quick. He dealt mostly in personalities, and he knew best how to get under Heberdon's thin skin.

"Don't be an ass, Han."

"Well, you seem to take it to heart, his getting pinched."

"It's nothing, of course, but one hates to see a neat bit of work spoiled by stupid conceit."

"Why don't you set up a correspondence course in crime, Frank?" Hanwell had asked at this juncture.

Heberdon ignored the flippant query. The laughter of the others annoyed him excessively.

"Oh, well, I expect if they hadn't got him one way they would in another," Spurway remarked in his heavy way. "A crook hasn't got a chance in the world. The dice are loaded against him."

Now, Heberdon's hobby was crime and criminals. He possessed quite an extensive library on such matters, and he had likewise gone deeply into the correlated subjects of police methods, locks, disguises, et cetera. He looked upon himself as an expert authority, and, therefore, it greatly increased his irritation to hear a stupid fellow like Spurway laying down the law.

"That shows how little you have thought about it," he had retorted. "That's the impression the police like to give out. That's what we tell ourselves in order to feel comfortable. As a matter of fact, the exact reverse is the truth. Wealth is wide open. All a man has to do is to help himself. With the most ordinary horse sense a crook would run no greater risks than a man in a so-called honest business."

It was these extreme statements which had really started the fray. "Come off!" they cried derisively. "What kind of dope do you use?"

"Oh, when you can't answer an argument it's easy to become abusive!" retorted Heberdon with his irritating superior air.

"The movies have softened your brain!" suggested Spurway.

"I'm not interested in the movie brand of crime," returned Heberdon coldly. "I know something about the real thing."

"But according to the statistics a very great proportion of crimes are solved and the perpetrators punished," remarked Nedham.

"A very great proportion of crimes never get into the newspapers or into the statistics," said Heberdon. "In such cases it is to the interest both to those who have suffered and to the police to conceal them. Even if your argument were well founded it would only prove that criminals have no more sense than other men. I said if he had horse sense."

"In your opinion there's only one really sensible man honest or dishonest," remarked Hanwell dryly. Heberdon ignored him.

"Haven't we got ten thousand police in this town?" demanded Spurway. "How do they occupy themselves?"

"Ten thousand patrolmen," corrected Heberdon. "They have nothing to do with solving crime. That's in the hands of the few hundred men in the Central Detective Bureau. All they do is to look wise and wait for a crook to betray himself."

"It's just a cheap popular stunt to run down the police," observed Spurway. "I don't take any stock in it."

"I'm not running down the police," said Heberdon. "I suppose they do all they can. But what can they do? In fiction, of course, the super-detective performs amazing feats of analysis and deduction, but you've got to remember that the author planned it all out in advance and was able to make things come out just the way he pleased. In life, detectives are just ordinary human beings. If a crook makes his getaway without leaving any clue, the sleuths are up a tree, aren't they? They can't get messages out of the air!"

"There's always a clue!"

"There needn't be, if the crook has good sense."

"That's all right as far as it goes," said Nedham in his slow way; "but you overlook the fact that the whole of society is organised on a law-abiding basis. That is to say, every one of us is behind the policeman, while every hand is raised against the crook He's at a hopeless disadvantage."

"Not at all," retorted Heberdon. "It's only the consciousness of our helplessness that makes us stand behind the police. It's the policeman that's at a disadvantage. The crook prepares his plans in secrecy; he can take as much time as he wants. Every crime is a surprise sprung on society, a fresh riddle to be guessed. It's easier to make a riddle for others to solve than to solve other people's riddles, isn't it?"

"It's not only a question of being caught," said Nedham. "When a man kicks over the traces he becomes an outcast, a stray dog; all the decencies of life are out of his reach."

Heberdon, in his anger, went a little further than he intended. "When a man kicks over the traces he becomes free!" he cried. "He is no longer subject to the absurd and galling rules that bind us down. He lives his own life!"

The other three stared at him in a startled way.

"The policeman has the telephone, the telegraph, the newspapers to help him." Spurway spoke with the air of one laying down an unanswerable proposition.

"Sure," said Heberdon, "so has the crook. Especially. the newspapers. For the newspapers print all the doings of the police, and the crook only has to read them to keep one move ahead."

"But organised society—" began Nedham still pursuing his own line of thought.

"All bluff and intimidation!" interrupted Heberdon. "A man only has to defy what you call organised society to discover how helpless it is!"

"You seem to know," put in Hanwell dryly. Heberdon turned slightly paler. "Can't you engage in a discussion without descending to personalities?" he demanded.

It would be tedious to report the entire discussion. As in all such controversies, once they had set forth their ideas, the participants had nothing to do but repeat them, making up in increased emphasis what their statements lacked in freshness. It soon became a hammer-and-tongs' affair of flat assertion opposed by flat denial. Here they stuck. The slow Nedham became rosy, Spurway turned an alarming purple, Hanwell's face showed a fixed grin like a cat's, and Heberdon's pallor took on a livid hue.

Quite carried away, the latter cried at last, "It's a cinch to stick up a bank nowadays! With a car waiting outside, the engine running, a turn around the corner, and the trick is done!"

This was received with loud jeers.

"Frank Heberdon, the heroic highwayman!"

"Desperado by proxy?"

"Oh, Frank's a new type, the theoretical thief!"

"Leader of the club-lounge gang of yeggs!" Heberdon could not take joshing of this sort. His eyes narrowed dangerously.

"If it's so easy why don't you give us a demonstration?" taunted Hanwell.

"By gad, I will!" cried Heberdon, beside himself.

The others stared, and laughed queerly. They had not expected to be taken up so quickly. Then suddenly a mental picture of the correct Heberdon in the role of hold-up man suggested itself to them, and the laughter became uproarious.

Their laughter was unbearable to Heberdon. "You think I don't mean it!" he cried. "I'll show you!" He snatched his cheque-book out of his pocket. "I've got five hundred to put up on it. Will you match it?"

This effectually stilled their laughter. Spurway, who was the most nearly drunk of the quartet, solemnly drew out his cheque-book and prepared to write. After he had made the first move it was difficult for the other two to draw back, Hanwell, thinking to call Heberdon's bluff, made haste to produce his cheque-book in turn. Only Nedham ventured to remonstrate.

"Come on, fellows, this has gone too far. Think what you're doing!"

Heberdon turned on him with an ugly sneer. "I thought that would show up the short sports!" he said. There was a hateful, jeering quality in his voice that no man with warm blood in his veins could tolerate. Nedham flushed, and, taking out his cheque-book, wrote a cheque and tossed it in the centre of the table.

"I'm content," he said shortly.

Hanwell looked anxious. He would have liked to draw back then, but he lacked the initiative. Grown men, no less than boys, are led into strange situations through their fear of taking a dare.

"Is it five hundred each?" he asked in an uncertain voice.

"Sure," said Heberdon. "That's only fair since I take the risk."

Hanwell wrote his cheque out slowly.

Spurway had signed his. "I suppose we can have them certified in the morning," he remarked solemnly.

"Oh, I hope we're not bona-fide crooks," said Nedham bitterly.

Nedham, once the die was cast, seemed more determined than any of them. "I think it's all damned nonsense," he said, "but since you insist on it, let the consequences be on your own head!" He drew a sheet of paper toward him, and wrote rapidly.

"What are you doing?" asked Hanwell anxiously. "Drawing up a memorandum of the bet."

"Oh, your word is sufficient," said Heberdon patronisingly.

"You don't get the idea," observed Nedham dryly. "You might slip up, you know."

"No fear of that," Heberdon spoke confidently.

"I hope not, for all our sakes. I don't relish being made a fool of any more than the next man. It's just as well to take precautions. We'll seal this and deposit it in the office, where it will be stamped with the receiving stamp and the date. If you should happen to be nabbed by the stupid police, it may save you a jail sentence—or at least mitigate it."

Hanwell's and Spurway's eyes bolted at the ominous sound of the words "jail sentence," but not Heberdon's. Anger blinded him to every consideration save the necessity of justifying himself.

"What conditions do you lay down?" Nedham asked him. "It's your privilege to make your own." Heberdon affected a nonchalant air. "I undertake to stick up a New York City bank single-handed during business hours, and get clean away with a sum exceeding two thousand. Of course, I can't tell what the haul will amount to."

Nedham wrote. Finishing this, he said: "There ought to be a time limit set. I don't suppose any of us can afford to keep this amount of money tied up indefinitely."

"Say within a month, or I forfeit," suggested Heberdon.

Nedham completed writing his statement.

"What would you do with the loot?" Hanwell nervously wanted to know.

"Return it, of course," answered Heberdon with a cool stare. "What do you think I am?"

The paper was passed around the table and signed in characteristic style, Heberdon with bravado, Hanwell with signs of panic, Spurway solemnly closing one eye, and Nedham doggedly with tight lips. It was then enclosed with the cheques, and the envelope sealed with wax. They carried it downstairs to the club superintendent, who, according to instructions, stamped it with the club stamp and put it in the safe. The superintendent understood only that it contained the stakes of a wager, and was to be yielded up on demand of any two of the parties concerned.

HEBERDON lived in a tiny but rather luxurious flat immediately across the park from the club. The same building now altered into bachelor apartments had been the city residence of his family for a generation, and from it Heberdon derived the modest income that barely sufficed his needs. He himself had scraped together every cent of his little patrimony to make the necessary alterations to put the house on an income-producing basis. Indeed, up to this time every act of Heberdon's life had been marked by prudence and caution—too much caution perhaps.

His law practice was largely one of courtesy. It about paid the rent of the smallest office in a good building and the wages of an office boy, who was necessary to keep the establishment open, for Heberdon never allowed his "practice" to interfere with his afternoon bridge at the club, nor, for that matter, with golf in the mornings, when the weather was suitable. He had a standing offer to enter the office of his uncle, ex-Judge Palliser, of the State Supreme Court, but that he knew entailed real work, and he was coy about accepting it.

"Really, I can't give up my practice," he would say. That practice did yeoman's service in conversation.

Heberdon was the last of his immediate family, but he enjoyed a large and ultra-respectable connection of uncles, aunts, cousins, et cetera. Besides Judge Palliser—head of the firm of Palliser, Beardmore, Beynon and Riggs, and one of our leading corporation lawyers—there was Mrs. Pembroke Conard, leader of the old Knickerbocker set, his aunt; Professor Maltbie Heberdon, Dean of Kingston, another uncle, and so on. Heberdon, though he affected to despise them as a lot of dull owls, was, nevertheless, very sensible of the advantages of such connections, and lost no opportunity of cultivating his graft with those who counted. For years h had been "paying attention" to his cousin, Ida Palliser, the judge's eldest daughter. It was an indefinite sort of affair, entailing no responsibilities.

Other young men might have considered that Heberdon's lines were cast in very pleasant places, but never was there a more inveterate grumbler. Nobody appreciated him at his true worth, he felt. He had been born to accomplish great things, he told himself, but circumstances held him down.

Next morning he awoke, conscious of a feeling of heaviness under the occiput. His thoughts ran: "What's the matter with me? Drank too much last night! Blamed fool! Well, never again!"

Suddenly recollection of the bet rushed back on him, and he sat up in bed in a panic. "Great Heaven! What have I done? I must have been out of my mind! How can I get out of it? How can I get out of it?"

He got out of bed all shaky and took a stiff horn of whisky to steady his nerves. Presently he felt better.

"It's not up to me to get out of it," he thought. "At least, not right away. I have a month. The other fellows are sure to weaken. Hanwell's scared green already, and Spurway will be, as soon as he sobers up. If I play my cards right they'll pay me the money not to do it. As for Nedham, he can go to hell, dam stubborn mule!

"In the meantime I'll go ahead just as if I meant to carry the thing through. Pick my bank. Lay all my plans—"

At this point in his deliberations a queer little feeling of pleasure began to run through his mind like quicksilver. "It would be fun to plan such a job! To pit my wits against the whole of what Nedham calls 'organised' society. I have the wits and the pluck to do it, too. Never had a chance to prove them. Rotten dull life I lead. I was cut out for something better.

"They laughed at me! I'd love to show them! If I should do it, it would be perfectly safe. Nobody would ever suspect me. And those fellows would damn well keep their mouths shut. Lord! The very idea makes my blood run faster!

"But, of course, I'm not going to do it really. And yet—"

In the course of the morning Hanwell called him up at the office. At the first sound of his anxious voice Heberdon smiled contemptuously into the receiver. "Hallo, Frank! How do you feel this morning?"

"Great!" rejoined Heberdon, with particular heartiness.

Hanwell's voice fell. "Oh, you do, do you?" He paused.

"What can I do for you, old man?" asked Heberdon. "Say, about that bet last night. What a pack of fools we were!" A loud but unconvincing laugh here. "You didn't take it seriously, of course."

"Do I understand you're trying to get out of it?" demanded Heberdon with assumed astonishment.

"Oh, no, no!" said Hanwell quickly. "A bet's a bet, of course. That's not what I called up about. I wanted to know—er—if you'd be at the club to-night."

"Sure."

Later Spurway dropped in on him, pinker than usual and very self-conscious. His greeting was effusive. He tried to get away with the innocent candid, but he was as transparent as window-glass.

"'Lo, Frank. I certainly did get beyond myself last night."

"Oh, you had a bit of a bun on."

Spurway passed a fat hand over his brow. "I have a vague recollection of making some bet or other. Thought I'd better come round and find out what it was. Of course I'll stick by my part of it, though I was drunk."

"Come off," said Heberdon scornfully. "You weren't as drunk as all that."

Spurway made a heavy pretence of trying to remember. "Something about your sticking up a bank," he said.

"Cut out the comedy," exclaimed Heberdon. "You remember just as well as I do."

"But when I woke up this morning I couldn't believe in my own recollection. You surely weren't in earnest."

"I was."

"Oh, my Lord, Frank! Think what you're doing!" Heberdon stuck out his chin truculently. "Are you trying to renege?" he demanded.

"Oh, no, no!" said Spurway helplessly. "But this is awful—awful!" He went out muttering to himself.

Finally Nedham came. Nedham was of tougher fibre than the other two, and he went directly to the point.

"Look here, Frank, that was a damn fool business we started last night. Let's call it off. I'm quite sure that Hanwell and Spurway feel the same about it as I."

"I don't know that it is exactly up to them—or to you," said Heberdon with a disagreeable smile. "I was the challenged one."

Nedham stared. "You can't mean that you intend to carry it out!"

"I carry out everything I start."

"But, my dear fellow, you're risking everything, your professional reputation, your liberty!"

"Why don't you say plainly that you want to get out of it?" said Heberdon with a sneer.

"I do want to get out of it," answered Nedham earnestly. "I don't want to be a party to another man's suicide—worse than suicide."

"Much obliged," said Heberdon. "You can always stop payment on your cheque, you know."

Nedham flushed up angrily and rose. "You talk like a schoolboy!"

"I don't need you to put me right," retorted Heberdon. "It isn't my feet that are cold."

Nedham strode angrily out of the office.

Heberdon immediately started making his plans. He still told himself that, of course, he would drop the thing as soon as Nedham et al. were reduced to a proper state of humility, but in the meantime he went about it as in a game with himself. That very day he dropped into several down-town banks to look around. He soon found that wealth was not so "wide-open" as he had confidently asseverated.

You no sooner started to look around a bank than you found watchful eyes upon you. "How dare they suspect me of anything crooked?" thought Heberdon with a sense of outrage.

He had no sense of humour. The largest bank of all had a "pill-box" elevated above the floor with ugly looking loopholes commanding the entrances. Heberdon shrewdly suspected that this was a mere bit of stage business, but if the pill-box had been constructed merely for its psychological effect, it worked in his case. The skin of his scalp tingled at the thought of defying the aim of a possible unseen watcher within. He decided that the big down-town banks with their crowds of customers and numerous guards and attendants were out of the question.

There remained the up-town and suburban banks. Their business is now mainly in the hands of two or three big institutions who specialise in outlying branches. Heberdon procured lists of the latter, and, striking out the obviously impossible ones, began to visit the others in order.

He put them through a gradual process of elimination. Some were hopeless at first glance. Others more promising he revisited and compared. He gave up his whole time to it. More and more it became like a fascinating game. At last he had an opportunity to apply his long-pondered theories on crime. His idle days were at last filled with an object. Never had his brain worked so quickly and sharply; never had life seemed so full.

From his long list he struck off one name after another. He found that small banks generally were arranged according to one of two plans; either the banking office was a square—or round—enclosure with the cages ranged all round, or else the cages extended in a row down one side of a corridor. Needless to say the latter plan suited him better. In such a bank all the clerks were under his eye at once, and no one could take him from the rear.

The paying-teller's window was his particular object. Sometimes it was awkwardly placed in relation to his getaway; sometimes the teller himself was too determined-looking a fellow. In one bank otherwise suitable, Heberdon was shocked to discover an electric lock on the street door which presumably could be operated from within the cages in case anybody tried to make a hasty getaway. This he considered a low-down trick. Some banks dealt principally with stores; these paid out little money, but only took it in. Others did a business so small as to be beneath Heberdon's notice altogether.

Not to detail too minutely the different stages of his search, it may be said at once that he finally picked on the Princesboro branch of the Wool Exchange Trust Company. This bank included several large factories among its customers and paid out large sums weekly for pay-roll purposes. It faced the plaza of the Princesboro Bridge. It occupied a corner store, and the cages stretched in a long line down a corridor none too brightly lighted. The paying-teller occupied the cage nearest the street door, though separated from the door by the office of the cashier or manager. Most important of all to Heberdon, the paying-teller was a pale, mild-appearing young man, just what he was looking for. "He'll collapse like a pricked balloon," he told himself.

With exemplary patience Heberdon returned to the bank day after day to watch and observe from without and within. The appearance of the elegant correct young lawyer, with his pince-nez, was not such as to excite suspicion readily. Those clerks who noticed him probably took him for a new customer. As a result of these visits Heberdon established the following main facts:—

(a) There was a uniformed attendant—possibly armed—on guard in the corridor during business hours, a dangerous-looking customer.

(b) But he went out to lunch every day at twelve-thirty, remaining until one.

(c) Between the hours of twelve and one very few customers visited the bank.

(d) The little glass-enclosed office just inside the street door and on your left as you entered was occupied by two men, manager, presumably, and his assistant. The former went out every day, remaining until one, whereupon the other went out for an hour. Both were exact and regular in their habits.

(e) The pay-roll money was mostly drawn on Friday afternoons. The rush to withdraw began soon after one o'clock and continued until the closing hour. For a while before they came on Fridays, the paying-teller always occupied himself in getting his cash out of the safe and arranging it on the desk in front of him in convenient form to pay out.

(f) At the street entrance to the bank were a pair of old-fashioned doors which opened inward only, and had knobs on them.

Outside the doors there was a folding steel gate, but as

this was always drawn back during business hours, it did not

enter into Heberdon's calculations. It was perhaps the doors that

finally led him to settle on the Princesboro Bank. "Oh, this is a

cinch!" he said to himself.

From the foregoing may be readily deduced the reasons that led Heberdon to decide that the hour of twelve-fifty on any Friday would be the proper time to pull off his trick.

It would be difficult to say just at what moment all this ceased to be a game, and crystallised into a positive intention. Heberdon himself could not have told. He was an adept in deceiving himself anyway. He discouraged what further timid overtures Spurway and Hanwell made, waiting for Nedham to humble himself. But Nedham never did, and in the end all three avoided him at the club, and took in another man to make a fourth at bridge.

Heberdon shrugged and went on planning. The elaborate imaginary structure that he reared for his amusement ended by mastering him. It became more real than reality. He became enamoured of the ingenuity of his plan; he could not bear to destroy anything so perfect; he had to try it. Still protesting to himself that it was all a game, he went on with his preparations until it was too late to turn back.

No trouble was too great for him to take in respect to the smallest detail of his scheme. He could have done it the second Friday after the wager was laid, but he took a whole extra week to make sure he had not forgotten anything, or had not overlooked any contingency. For instance, his disguise, he devoted whole days to perfecting that.

Among the members of the Chronos Club were a number of actors with whom Heberdon was acquainted. He made a practice of dropping into the dressing-room of one of them who happened to be playing in town, and watched him make up. He learned that professionals commonly do not use false moustaches, et cetera, but glue loose hair to their faces and trim and curl it to suit. Such appendages are almost impossible to detect.

Practising endlessly before his own mirror, Heberdon finally succeeded in making a glossy little moustache and embryo side-burns that would pass closest muster. He designed to play the part of a flashy young sport of the latest model and haunted burlesque theatres, roadhouses, and shore resorts to study his types.

A straw hat of exaggerated pattern, a much "shaped" and bepocketed suit of a weird shade of green, loud shoes, socks, tie, and shirt altered the correct Heberdon's appearance beyond all recognition. He left o the pince-nez, without which he had never been seen. On the day before that set for his enterprise he made up and dressed in his new clothes, in order to accustom himself to them, and spent the afternoon at Brighton Beach.

Here he boldly wooed the sun, and by evening the added pink tinge to his complexion completed his metamorphosis. He looked ten years younger; a perfect product of Coney Island and the East Side social clubs, one would have said. On his way home he came face to face with his three friends in Gramercy Park. They passed him without recognition, and Heberdon triumphed inwardly.

In his own room that night Heberdon bent all the faculties of his mind on the next day's task. He went over and over his plan, looking at it from every angle. "It is water-tight," he said to himself at last. "I can't fail!" Then he went to bed and slept like a child on the eve of an excursion.

THERE is a little hotel in Princesboro, and just above it is the single taxi-stand that the suburb boasts. At precisely twelve-forty next day a young fellow with a glossy little moustache and a nobby green suit issued from the hotel and hailed the first cab in line. It may be said that it was no part of Heberdon's plan to take the chauffeur into his confidence. In case of a chase, should the man prove unwilling, Heberdon carried that wherewith to persuade him.

With his hand on the door, Heberdon consulted his watch. "Must catch the one o'clock from the Nugent Avenue Station," he said to the chauffeur with a careless air. "Got to stop at the bank first. The Wool Exchange Trust on the plaza."

The man nodded. Heberdon got in and pulled the door after him. They started.

Up to this moment Heberdon's mind had been occupied with his calculations to the exclusion of aught else. But in the brief period of inaction during the ride, stage-fright laid its icy hand on his breast. His heart began to beat alarmingly, and to rise suffocatingly in his throat; a cold sweat sprang out on his palms and his temples, "I'll never be able to do it! Never! Never!" something whispered to him.

He would have given anything to leap out of the cab and run for it, but a force stronger than his will kept him fast. As a matter of fact, his days and nights of concentration on the plan of robbing the bank had in the end obsessed his brain. He could not conceive now of giving it up. His long preparations had created a power that carried him along in spite of himself. "Too late! Too late!" he thought despairingly.

He sought desperately to distract his mind from its terrors. Had he everything? Yes, the satchel, pistol unloaded—the light cloth cap to replace the too-conspicuous straw later, the thin hardwood wedge, the stout double iron hook that he had made himself out of a necktie-holder.

The taxi-cab stopped in front of the bank and the shaking Heberdon started subconsciously to go through the oft-rehearsed performance. To the driver he said with the best imitation of nonchalance he could muster:

"Let your engine run. I shan't be inside but a second."

Within the bank everything was always as he had seen it in his mind's eye; the uniformed attendant missing, the assistant manager alone in his little glass-enclosed office, at least half of the clerks out to lunch. At the door of the private office—which swung both ways—Heberdon made a feint of dropping his satchel. Stooping to pick it up he slipped his wedge under the door, and, straightening, tapped it home with the toe of his shoe.

There was but one customer in the corridor, and he was down at the receiving teller's window at the far end. Even as Heberdon looked at him he got his pass-book through the window and started to leave. In order to give him time to get out Heberdon turned to the customers' desk at his right hand, as if to write a cheque.

Silence filled the bank. The man who was walking out had on rubber-soled shoes, and his footfalls made no sound. From behind the brass grating came a sudden loud crackle as the book-keeper turned a page of his big ledger. He muttered to himself as he carried forward his column of figures. Then all was still again.

The silence contributed to Heberdon's demoralisation. He was suddenly conscious of the furnace-like heat of the place. His hand was trembling as with the palsy. Catching a sudden glimpse of a noiseless overhead fan out of the tail of his eye, he almost jumped out of his shoes.

"This will never do!" he said to himself as to somebody else. "You'll make a ghastly mess of the affair." All the way through he had the feeling of watching an alien body carry through what he had planned. "Drop it! Drop it!" he whispered. "Get out while there's time?" But that force outside his will kept him to it.

When the departing customer passed out through the street doors Heberdon turned around to the paying-teller's window. Within the pale and conscientious young man was counting and recounting his money, and arranging the packages of bills convenient to his hand against the rush he presently expected. All of a sudden the icy grip on Heberdon's breast relaxed. His hands ceased to tremble; he drew a long breath and found himself perfectly cool. "I have the pluck!" he told himself exultingly.

The paying-teller, aware of some one waiting at the window, looked up. He found himself gazing down the short barrel of an ugly little automatic pistol. Behind the pistol was a grim set face. He took his breath sharply, his jaw dropped, his hands fell nervelessly on his desk, a sickly green tinge crept under his skin. Heberdon had not mistaken his man.

In the soft and courteous tones he had often rehearsed, Heberdon said: "If you cry out or turn your head, I'll blow the top of your skull off. Raise the wicket and pass out all the money on your desk!"

Even before he finished speaking the young man's trembling hands flung up the brass gate and started shoving out the tall piles of bills. His wide and fascinated gaze never left the pistol. There was no sound to be heard but the whisper of the overhead fan and the soft plop of the packages as they slid off the little glass shelf into the satchel that Heberdon held beneath.

It was all over in fifteen seconds. "Twenty thousand, if it's a dollar!" thought Heberdon, with a fearful joy. At a peremptory nod from Heberdon the paying-teller let the little gate rattle down. Heberdon began to back away. The other man's sick eyes followed the pistol barrel. Heberdon turned and walked smartly to the street door. As he laid hand upon it he heard a gasping cry behind him:

"Boys, I'm robbed!"

The young man in the glass-enclosed office snatched a revolver from a pigeon-hole of his desk with incredible swiftness, and, springing up, launched himself against the door. But the wedge held it, at least for the moment. Heberdon passed out into the street, and turning with a careless movement dropped his double-hook over the two handles. No indifferent passer-by would be likely to catch the significance of what he was doing. He then walked sedately across the pavement and got in a cab.

"Nugent Avenue Station," he said with an off-hand air. "Let her go!"

As the cab got under way Heberdon had a fleeting glimpse of white and excited faces within the doors of the bank. The doors were violently rattled. The chauffeur did not hear it above the noise of his engine, but passers-by did, and Heberdon, looking back through the little rear window, saw them stop and look. He was only going to have a few seconds' start.

"It's enough!" he told himself. "There is no other car right handy. If my chauffeur gets cold feet I have the gun for him."

His spirits soared. "Twenty thousand! The Riviera, Italy, Cairo! A whole year of delicious idleness! Choice eats, choice drinks, choice smokes, and lively company! At last I'll be able to play the part I'm fitted for!"

In his flush of triumph he completely forgot his intention of returning the money. They were crossing the plaza at a good rate, the chauffeur, all unconscious of the storm preparing to break behind, when there came a report like a small cannon from beneath the cab. The sound had the effect of letting all the wind out of Heberdon, too.

"By the eternal, a tyre!" he thought. "I'm done! Why didn't I look at the tyres? What shall I do?"

The taxicab drew up beside the curb at the corner of the principal street leading from the plaza. At the same moment across the open space figures came tumbling out of the bank, and seeing the stoppage of the cab set up loud shouts. Heberdon leaped out and forthwith took to his heels down the street. The shoppers instinctively made for the doorways. The chauffeur, arrested in full motion, stood staring after his fare, a comical figure of astonishment.

The shouts from the bank gave him his cue. Suddenly he came to life and with a whoop leaped after Heberdon. Heberdon, stealing a white glance over his shoulder, saw with a sinking heart what long legs he had, and what a hard eye. Heberdon, like most city men, had not really tried out his legs in years. To be sure, Nature suggested the proper motions at this juncture, but he lacked confidence in his legs.

"I'll never be able to do it!" he told himself despairingly, and in so thinking his sinews softened. On the other hand, the young chauffeur looked able to run all day, and half a block behind the chauffeur was a mob gathering volume like a snowball.

All the other people gave them the right of way like fire-engines. The chauffeur gained on Heberdon with every stride. Heberdon could hear his quick, sure steps—quicker than his own. Finally the chauffeur cried, seemingly right behind him: "Stop, you thief!"

Heberdon, in a panic, dropped the satchel. The chauffeur stopped to pick it up, and the fugitive gained a precious thirty yards. But down the block the roar was momentarily growing louder. Those who dared not stop Heberdon were safely falling in behind his pursuers. The sound of that roar struck terror into the very core of Heberdon's breast. He learned what it was to be hunted.

"Why do I go on running," he thought. "It's all up! I might as well stop!"

He almost collided with a young lady in the act of descending from her limousine to enter a shop. The hunted creature received an impression of warm, kind eyes. She drew aside a little from the door of her cab with a barely perceptible gesture of invitation. Heberdon, swerving, flung himself in. She sprang after. A roar of rage went up from the pursuing crowd. The girl's eyes sparkled. Leaning out, she cried to the chauffeur:

"Step on her! Step on her! Turn the first corner to the left!"

The engine was running, and the car jerked violently into motion. She slammed the door. As they turned the corner, Heberdon, looking back, saw that his pursuers had stopped another car, and, climbing aboard, were pointing out the limousine to the chauffeur.

At such a moment Heberdon was not exactly susceptible to the charms of sex. He had an impression that with heightened colour and sparkling eyes she was studying him with extraordinary curiosity. He wished to escape from the regard of those eyes.

At the moment he was not conscious of what she looked like, but he remembered well enough later; her lovely clothes—a little too spectacular for Heberdon's lady cousins; her full, red, generous mouth, her glowing dark eyes. She was very young; her whole person radiated youth recklessly, lavishly.

She was as excited as a boy. Snatching up the speaking-tube, she cried: "Faster! Faster! Never mind what you break! Fifty dollars if you shake that car!" They were in a quieter street with a bad pavement, over which the car bounced, flinging them to the roof. They turned to the right and again to the left, but the following car clung to them. It was of lighter build, and picked up faster. The pavements became worse and worse, and, in spite of himself, the chauffeur and the limousine slowed down. His mistress snatched up the speaking-tube again.

"Step on her!" she cried. "To hell with the springs! I'll pay."

Heberdon's cold heart experienced a feeling of warmth. "Splendid creature!" he thought.

They turned to the right again into a well-paved street stretching away to the south. The chauffeur "stepping on her" at last they roared down with wide-open exhaust.

"No more corners!" commanded the girl. "We'll leave them at a standstill in the straight."

Looking through the back window, they saw their pursuers turn into the street, and other cars behind them. But as she had said, they were distancing them fast. They had now left the central part of Princesboro behind them, and their way stretched ahead of them unhindered by traffic. Heberdon began to breathe more freely.

The girl was still studying him. "What did you do?" she asked downrightly, like a boy.

"Nothing," muttered Heberdon. He looked away. He was scarcely in the posture in which he cared to talk to a pretty woman. He was accustomed to patronise women from an eminence. This one had him at a disadvantage. His vanity squirmed under those candid eyes.

But feeling that she was entitled to some sort of an explanation, he went on: "There was some trouble in the bank when I was passing. I don't know what it was. But they picked on me."

The girl looked disappointed. "You could trust me," she said.

The limousine was now making fifty miles an hour. "I'm safe if those tyres hold," thought Heberdon.

As if in answer to his thought, the girl said, smiling, "The tyres are new."

Alas for their hopes! There was a railway crossing at grade in their path, and as they approached it the striped gates slowly descended. The chauffeur put on his brakes, and the car half-slewed around in the road.

"Smash through!" cried the girl excitedly. "Take the gates! You have time!"

But the man, with a shake of his head, brought his car to a stop at the barrier.

"Oh, damn him for a coward!" cried the girl with tears in her eyes. "If I had been at the wheel!"

Without more ado, Heberdon leaped out. He never gave a thought to the fate of the girl. He ducked under the gates, but the oncoming train was now at hand, and he could not pass in front. It was an outbound freight, miles long, it seemed to his despairing heart, and moving slowly. There was nothing for him to do but run down the line alongside the train. The cars with his pursuers were drawing near.

Heberdon thought: "I'll swing myself on the caboose as she passes and hide inside. She's gathering way all the time. I have money to square the train crew. Anyhow, they couldn't throw me off until she slows down."

But on the rear platform stood a trainman with an uncompromising, hard eye. Heberdon ran on.

His pursuers had likewise taken to the railway line on foot. Catching sight of him, they raised renewed shouts. Heberdon was now at the entrance to the railway yards. A high board fence bounded it on either hand. But long lines of freight cars stood on the spreading tracks, and these suggested good cover to the fugitive. Crossing the main line, he ran around the end of one string of cars and crawled under another. Here he felt safe enough to slow down a little and give his overladen heart a chance.

"They'll run on down through the yard," he decided. "If I stay up at this end perhaps I can double back."

He heard his pursuers, now reduced to a score or so of men, come running down the line and pause among the cars at a loss. But one of them must have dropped to the ground and looked along underneath, for a voice was raised:

"I see his legs! Third track over!"

The fugitive took to his heels again, darting, twisting, doubling around the cars until he had fairly lost his own way in the depths of the yard. He saw nothing of his pursuers, nor did he hear them again. There must have been moments when they were close, but with a common impulse of prudence, they no longer called to each other. Heberdon did not know at what moment he might plump on them around a car. His heart was continually in his mouth. He who had lived such a sheltered and well-ordered life up to this time would have shuddered to catch sight in a mirror of the wild-eyed, hunted thing he was now.

The partly open portal of a box-car tempted him. He drew himself aboard, and softly closing the door flung himself down to rest. There was no rest for his fears, though. He felt trapped. He pictured his pursuers drawing a line around the yard, and when they had every point of egress watched, starting a car-to-car search. It appeared that he had made a fatal tactical error. He ought to have kept on going until he found a way out of the yard.

He wasted some moments of agony, then, trying to screw up his courage sufficiently to open the door again. Finally he began to draw it back an inch at a time. The crack revealed nothing stirring outside, nor could he hear any sound. He opened it sufficiently to permit the passage of his body, and stuck his head out. He looked into the face of the tall young chauffeur who was flattened against the car waiting for him. The chauffeur roared with laughter.

A hand shot out and gripped Heberdon's collar. He was ignominiously hauled out and dropped to the ground. He got to his feet and stood apathetically awaiting his captor's pleasure. There was no fight in him.

"Hey, men!" cried the chauffeur. "Here he is! I've got him!"

Men appeared from several directions around the cars.

HEBERDON was frisked and his gun taken from him. Forming in procession, they wended their way out of the yard and back up the line toward the street crossing where the automobiles had been left. Midway in the procession walked the chauffeur with his hand in Heberdon's collar. This connection was in sharp contrast to all of Heberdon's former relations with taxicab drivers.

The men, still heated with excitement, talked about Heberdon as if he were an inanimate object or were not there at all. They displayed no particular animus against him, but in a way were almost kindly disposed as to one who had furnished the excuse for a madly exciting and successful man-hunt.

"Gee! If he'd kept on to the river, we'd never have got him. He could have slipped on a ferry."

"Aw, they always do the wrong thing, them crooks. Lose their heads when they want it most."

"He don't look like an old-timer, do he? Bet this was his first job."

"Well, he's got all the pep scared out of him now all right, all right."

"Don't look right human, does he?"

"Oh, you can tell he's a bad one. Got a shifty eye."

Heberdon at first was merely dazed. But the exercise of walking restored his faculties, and the future began to unroll itself before his mind's eye in colours hideously vivid. The loss of his secure and desirable place in the world—he could see his respectable relatives disowning him in horror; shame, disgrace, jail! Bitterest of all to his vanity was the thought of the triumph of his clubmates; he made sure they would triumph. Heberdon lived on his vanity. A sick feeling of desperation seized him. He looked around him furtively.

They were now streaming along the double-tracked line. The approach of another long freight, this one bound in at a good rate of speed, forced them all to take to a ditch. Heberdon saw his chance. It was a desperate one, but better death under the wheels than—

Wrenching himself free, he sprang across the track immediately in front of the looming engine. The breath of the monster was hot on his neck, but he found himself safe on the other side—and none had cared to follow. For the moment he was safe. On the other side of the long train, let the men shout themselves hoarse if they wanted.

In a trice Heberdon was over the high fence that bounded the right of way, across a dingy yard and through a working man's humble cottage before the startled eyes of the housewife. He cut diagonally across a main street, and turned down another that led away at right angles from the railway. From the little houses women and children looked curiously after the running figure, but prudently forbore to take up the chase. He turned two more corners, and, feeling comparatively safe, slowed down to a walk. As a walker, nobody noticed him.

He considered his situation anxiously. He was not by any means out of danger, for they had him awkwardly cornered in a peninsula of Princesboro. On his right was the East River a half-mile or so distant. The ferry-houses were now well behind him, and he dared not retrace his steps. Somewhere in front of him, he knew, was the mouth of Oldtown Creek, and to the left was Central Avenue, the automobile thoroughfare which was presumably patrolled by those looking for him. The nearest bridge over the creek was that which carried Central Avenue across. He finally decided to make for Central Avenue, watch his chance of getting across, and then cross the creek by one of the bridges higher up. If it had only been a neighbourhood where taxicabs were to be had!

At the next corner he turned to the left again. Crossing the first street, to his dismay he saw figures of men far to the left, their attitude proclaiming them searchers. Before he could get out of sight one perceived him and raised a shout. The hunt was on again.

Heberdon realised that it was the bright band around his hat, visible as far as he was, which had betrayed him. How vainly he cursed it now. Why hadn't he thrown it away? He had the cap in his pocket to take its place. Luck was certainly against him!

Swerving to the right, he ran blindly down the street, with his pursuers in full cry. This was another tactical error, but he was becoming confused now. Still, he had two blocks start, and there was no automobile to run him down. Attracted by the shouting, people rushed out of the little houses. Fearful of being tripped up or seized by some bolder spirit, Heberdon took to the middle of the road.

Two blocks ahead of him the street ended at the bank or the creek. Heberdon could see a strip of foul, black water. Before this he had realised his mistake in taking this direction, and at the last corner he essayed to turn toward Central Avenue again. But a fresh shout greeted him from this direction. An automobile was approaching with men on the running-board. Heberdon stopped short with despair in his heart. Escape was cut off in three directions. There was only one way left, to the south. Whirling about he saw that he was cut off there, too, by a bend in the creek.

For a moment he hung in indecision at the crossroads, his wild eyes darting this way and that. The approaching men were yelling like fiends. Better the water than the men. Heberdon ran down the remaining short block and across the wharf at the end and jumped into the oily creek.

Heberdon was a swimmer—or had been a swimmer in boyhood—and he instinctively struck out, much hampered by his clothes. The stream was only forty or fifty yards wide at this point, more of the nature of a canal. The outgoing tide helped him more than his own efforts; he was carried swiftly away from the wharf. The silly hat floated away on an independent course.

Heberdon had made perhaps a third of the way across when his pursuers began to arrive on the wharf. None offered to follow him into the foul water, but all contented themselves with yelling imprecations after him. One man pulled a revolver and began to shoot. Heberdon's heart turned to water. "Inhuman brute!" he thought. "I'm done!"

He kept under water as well as he could, and what with that and the poorness of the marksman's aim, the ammunition was exhausted without any damage to the swimmer.

Before the man could reload, the tide carried Heberdon around the bend out of his range of vision. Some had started to run away, evidently in the hope of cutting him off below, and Heberdon had heard the automobile start off. It would naturally make for the bridge a quarter of a mile upstream.

Somehow Heberdon found himself across the creek. At the point of exhaustion he pulled himself up a rotting ladder on an old bulkhead. Some of his pursuers had come out lower down across the stream, but he was safely out of their reach. He was more anxious about the automobile.

He found himself in a paved way between great bonded warehouses, shuttered and silent. There was no one about on his side. He started to run weakly over the cobblestones.

The smelly water squished out of his shoes, and left a wet trail as he ran. He came out on a street paralleling the creek. There were people here, and he dared not run, though this was the street down which he expected the automobile to appear. He got around a corner and found himself in a block of lumber and coal yards and small factories.

Aware of the danger of being trapped again, nevertheless he could run no further. His heart was bursting. The tall piles of boards drying in the air offered good cover. There was no one watching at the gate of the lumber yard. He ran in and twisted and turned through the alleys between the lumber until even terror could carry him no farther. He flung himself down and lay there gasping.

By-and-by the sound of an automobile in the street outside brought him to his feet again. It was not necessarily the automobile he feared, but the mere sound was enough to start him going. He staggered on until he came to the other side of the yard which fronted on the broad expanse of the East River. The matchless panorama brought no joy to Heberdon's heart. It was only another wall cutting off escape.

On the river-front some men were loading lumber on a lighter. Heberdon was careful not to expose himself to them. By keeping behind the piles, and watching his chance to dart across open spaces, he contrived to circle around them, and to gain the boundary fence at the lower side of the yard. Here in a slip on the waterfront his glazed eyes were brightened by the sight of a skiff, a way of escape without returning to the street.

There were no oars in the boat, but a hasty search finally revealed them hidden under some boards. Heberdon cast off and pulled out of the slip with inept strokes; what matter if he was venturing in his inexperience on perilous waters or small boats? Anything was better than what lay behind him.

There was only one way to go, for the tide was running out faster than he could pull against it. So much the better for him; Princesboro and Oldtown Creek were left safely behind. He pulled but feebly, letting the tide carry him as it would, taking care only to avoid the ends of the piers. He was now off the district of Johnsburgh, with the great black sugar refineries stretched alongshore, and ahead of him the far-flung span of the Johnsburgh Bridge, with the trolley-cars and automobiles threading their way across like spiders on a web.

As he was carried down-stream the river traffic ever increased and the unpractised oarsman's heart was continually in his mouth, with the tugs, lighters, and ferries that came at him from every side, bearing down on him with contemptuous disregard for a mere rowboat, and kicking up great waves behind that threatened to swamp him. Even more alarming were the great car-floats swinging around helpless in the grip of the tide. Had he escaped one danger only to fall victim to another? Heberdon, with his unstrung nerves, was ready to weep.

He reflected that a general alarm would shortly be out for him, if indeed his description was not already in the hands of every policeman in the five boroughs. The sight of a natty little launch with a big P. D. on the bow, smartly bucking the tide, reminded him that there were police on the water, too. He almost had heart failure when it bore down on him. But it passed without stopping. The next one might have later information. It was up to him to find a hiding-place.

Yet he dared not land either. As long as it was daylight his drenched and bedraggled appearance would render him fatally conspicuous in the streets. A pier higher than its neighbours and with a clear space beneath offered a solution. He allowed the skiff to drift beneath it, and, making sure from the high-water mark on the piles that the tide would not presently rise and crush his skiff under the overhead sleepers, he made his painter fast and determined to wait there until dark.

For a long time he sat gazing out on the bright river from its gloomy hiding-place in a daze of fatigue, not thinking about anything in particular. The tide lapped and sucked at the piles, and the sounds of the outer world reached him reverberating hollowly over the surface of the water. Gradually drowsiness overcame him. Once he heard the scamper of little feet on the overhead beam, and started up in affright. But even the thought of rats could not keep him awake. He slept.

When he awoke it was beginning to grow dark on the river outside, the water gleamed like a sapphire in the evening light. The sounds of traffic had almost ceased. He resolved to wait yet a while. He was stiff and sore all over and his head ached continually from the emanations of the sewer-laden water.

It was pitch-dark where he was, and, what with the smell of corruption and the threatening chuckle of the water, a nightmare cavern. He imagined that he saw snaky shadows in every corner. His damp clothes clung to him heavily. How sickeningly he longed for light, warmth, and the sound of human voices! The thought of the club was like an unattainable Elysium.

He was crouching between the two thwarts of his skiff. Suddenly a heavy body dropped in the stern, landing within a few inches of him, and almost rolling the skiff under. A grunt of terror was forced from Heberdon's lungs, and like an animal he scrambled to the point of the bow. He clung there, paralysed with fear. The place suggested nameless things. He could see nothing but a darker shadow in the stern. It was creeping toward him, feeling for a weapon. His throat was constricted; he could not make a sound. The thing fumbled with an oar.

Heberdon, in the expectation of a blow, suddenly recovered the use of his limbs, and like an ape, half-leaped, half-scrambled to the joist overhead. He lay upon it, gripping it between elbows and knees. The creature below jabbed viciously with the oar at the place where he had just been. Meeting with no resistance, the shape crept farther forward in the skiff. Heberdon could then have dropped on its back, but not for worlds would he have come to grips with the loathsome thing.

It fumbled at the painter, freed it, and with a push against the piles propelled the boat out from under the pier. The tide was now running up. Heberdon was so relieved to be rid of the shape that he let the boat go without a thought. Not until he perceived, in the fading light outside, it was a man like himself, did the reaction set in and, mixed with the feeling of relief and impotent rage, convulsed him. But he did not curse him nor seek to call him back, for it was an ominously burly figure with a gorilla-like head sunk between his shoulders. Heberdon never saw his face. The skiff was quickly carried out of his range of vision.

Where the man had come from Heberdon never knew. He must have lain concealed under the floor of the pier, like a gigantic wood-louse. There are no doubt many underground routes in the city that people who live on the surface never suspect. As for Heberdon, blocked in front and behind by girders running in the other direction, there was no possible escape save by dropping into the water. He dreaded it as a shell-shocked man dreads a battle, but finally he had to let himself drop, gasping.

In the water he pulled himself shoreward from pile to pile. It was quite dark now, but he dared not venture outside, because he heard quiet voices just overhead, working people, no doubt, taking the evening air on the water-front. He could not call for help, of course, without giving an account of himself. At the shore end of the pier extended a long bulkhead, smooth and greasy, affording him no finger-hold. Up and down he searched in vain for a ladder or a break. It was like the futile struggles of an insect, bumping its head against the side of a water-pail.

He swam a distance of blocks, it seemed to him, and his strength was rapidly failing when he came at last to a place where the bulkhead was rotten and the interstices between the planks afforded him a precarious hand-and-foot hold. He drew himself out and sat down on the stringpiece to recover himself. Fortunately in this place there were no loiterers, but by that time he would not have cared if there had been.

He was in the factory district of Johnsburgh, silent and deserted at this time of night. After having wrung the water from his clothes as best he could, he started up-town, heading for the bridge terminal. Some time passed before he could nerve himself to cross the brightly lighted plaza. He thought of the other plaza with a shudder. A street clock told him it was after ten.

He dared not expose himself in a lighted trolley-car, and was obliged to drag his weary body across the two-mile span in the comparative obscurity of the promenade. And on the Manhattan side he had yet another two miles to walk to Gramercy Park.

When he finally reached his own building, it was fortunately closed for the night, the hall attendant gone. Otherwise he must still have been a wanderer. He let himself in with a thankful heart, and, climbing the stairs, closed his own door behind him with a sob of relief, and, flinging himself on the couch without undressing, slept again.

WHEN he awoke Heberdon's clock was striking six, and the little park below his windows was bright in the sunshine. He lay aghast at his recollections of the day before and hugging his sense of present security. The whole affair seemed like a dream now—a hideous dream at which he shuddered and tried to put out of mind. How cozy and charming his little rooms were! Every object how inexpressibly dear to him!

He was presently aroused to the fact that he had lain down in his damp clothes, and that his pleasant rooms were contaminated with a faint odour of sewage. Cursing himself for his folly, he hastened to bathe and to dress himself in his proper garments. On the clothes of the bank robber he poured benzine that he had provided for that purpose, and burnt them in the fireplace. He sprayed his atomiser around the room to sweeten the air.

He was keenly curious to see the morning paper—and not without apprehensions. It was delivered at his door at eight o'clock. He had no doubt that it was already waiting downstairs. But he did not care to betray too great an eagerness for news to the hall-boy. Finally when it dropped with a swish outside his door he waited until the receding footsteps had passed out of hearing, then pounced on it.

The hold-up of the Princesboro Bank occupied a prominent position on the front page. Heberdon read the story with a queer thrill. A pang of chagrin went through him when he learned the amount of cash that had been in his possession for a minute or two—twenty-seven thousand dollars. First, he hastily skimmed through the story and was reassured; the thief had got away clear, it was stated, and the police were with out clues. Then he read it more carefully, his vanity deliciously tickled by references to the desperado's cool nerve and resourcefulness.

He eagerly read of the girl who had aided him. She had been arrested and later arraigned in the magistrate's court. It had naturally been supposed that she was an accomplice of the thief, but she stoutly protested that she had never seen him before, and had simply yielded to an impulse of compassion, seeing a human creature hunted by a mob. A cloud of witnesses appeared in her behalf—storekeepers of Princesboro, her fashionable friends, a faithful old man-servant.

Evidently she had made a conquest of the newspaper reporter; he was for her through and through, and indeed the whole court-room must have fallen under the spell of her beauty and candour. The magistrate had discharged her with a reprimand that scarcely veiled a compliment. Her name was Miss Cora Flowerday, and she lived at No. 23 Deepdene Road, Greenhill Gardens, an outlying part of Princesboro. "An orphan, with means of her own," so ran the story, and many a poor young man's mouth must have watered at the phrase.

"Splendid girl!" Heberdon said to himself—but not so warmly as on the day before. He was glad she had got off so easily, since it cost him nothing, but he had no desire at the moment ever to see her again. That incident in his life, that nightmare, was to be sponged off clean. Never again, he told himself, would he willingly set foot on the streets of Princesboro. Oh, blessed was respectability and all its works! He thought of all his solid and respectable relatives with positive affection. How could he ever have thought them dull? He decided to go see the Pallisers that very day. And yet—'way deep down in his consciousness, unheard and unacknowledged, there was a little nagging voice: "If only that cursed tyre had not burst!"

His breakfast was sent up as usual by the housekeeper of the apartment house. Heberdon lingered over it, tasting the satisfaction of a safe and ordered life with every mouthful. Never again would he call existence dull. He had a fleeting picture of himself in the grip of the chauffeur, and shuddered. He had had his fill of excitement. Anyway, it was high time he settled down.

He would think about that offer of a berth in his uncle's office—tremendously important firm. And his cousin Ida Palliser wasn't so bad by lamplight. Anyway, a man who wanted to get on couldn't afford to marry for youth and beauty. Solid family connections were the thing.

After breakfast he telephoned down to the hall-boy. As landlord, Heberdon enjoyed rather better service than the other tenants in the building.

"Thomas, what time do the first editions of the afternoon papers come out?"

"About ten o'clock, sir."

"Get me one, and bring it up."

"Yes, sir."

When it came, Heberdon read the usual rehash of the earlier story—but in another part of the paper there was a paragraph that caused the skin of his scalp to prickle and his palms to become moist. The blessed sense of security was stripped from him; a chasm yawned at his feet; the old sickening hunted feeling came winging back.

"In connection with the hold-up of the Princesboro branch of the Wool Exchange Trust Company at midday yesterday, an extraordinary story has been told the district attorney by a young man whose name for the present is withheld. This young man claims to be employed as bell-boy or waiter in one of the best-known clubs in the city. About a month ago, he says, four prominent young members of the club became involved in a discussion as to the ease with which crimes might be committed. In waiting on them he overheard much of their talk, he claims, and the upshot of the argument was that one of the four bet the others that he could hold up a New York City bank, single-handed, and get away clean. The police and the district attorney do not place much credence in the story, suspecting that it may be the invention of a notoriety-seeker who sees his chance of breaking into the newspapers. But, of course, it will be investigated."

Investigated! With a shiver Heberdon gazed at his timepiece. Ten-thirty; even now an emissary from the district attorney's office might be on the way! With trembling hands he made haste to dress himself for the street. Gone was his delightful feeling of affection for his little flat. His one idea now was to get away from it. As he picked up his hat the telephone bell rang, and his heart turned to water.

He instantly made up his mind what to do. He did not answer the 'phone, but stole out of the flat, and made his way up the final flight of stairs, which ended at a door opening on the roof. In a similar building two doors east, Heberdon had an acquaintance who, like himself, lived on the top floor. In order to save the stairs they had visited each other over the roof, and Heberdon, knowing the way, now proceeded to this other building and descended through it to the street.

Without daring to look back, he made rapid tracks to the east, pausing not until he was safely swallowed in the comfortable throng at the intersection of Broadway and Fifth Avenue. By this time, no one having tapped him on the shoulder, he began to breathe more freely. Entering a cigar-store, he made for a telephone booth and called up Hanwell's office.

Mr. Hanwell was out, his stenographer said. She believed that he might be found at the Chronos Club, as she had lately heard from him there. Heberdon called up the club and presently got Hanwell on the wire. From a slightly tremulous quality in his voice he guessed that the other had read the disturbing paragraph. Hanwell admitted as much.

"You'd better see the superintendent about a certain paper," Heberdon said meaningly.

"I have seen him. I got it from him."

"Good. Have you heard from the other fellows?"

"They're both here. We've got to see you at once, Can't talk about such a thing over the 'phone."

"I'd better not come there. Some one from the—well, we might be asked for there. I'm telephoning from a cigar-store at—" and Heberdon gave the number on Broadway. "You three get a taxi and pick me up at the door. We can talk in the cab."

"There in three minutes," said Hanwell.

Of the conference between the quartet that presently took place in a joggling taxi-cab, it is unnecessary to speak in detail. They all spent a bad quarter of an hour. It was Nedham who finally tried to stop the wrangling.

"Look here, you fellows, this gets us nowhere," he said. "What's the use of recrimination? We're all in the same hole, and we've got to get out of it the best we can."

"I didn't stick up a bank!" growled Spurway.

"Shut up; you were a party to it."

"What'll we do?" quavered Hanwell.

"Deny the whole thing," declared Spurway, "and stick to it."

"But we don't know how much the boy overheard."

"He can't know anything about the paper Nedham drew up. He wasn't in the room then. Anyhow, what's the word of a bell-boy against us four?"

"But the publicity will ruin us even if they can't prove anything!"

"Oh, for God's sake, stop snivelling! Buck up, can't you?"

"Then there's Maynard, too," wailed Hanwell. Maynard was the club superintendent.

"Maynard is safe. For the honour of the club, and all that."

Nedham spoke least, and to the best effect. "Maynard is safe, all right," he said. "But to deny the boy's story is to keep it alive. Admit it, and it will be forgotten."

"Admit it!" cried the other three, staring.

"Sure. Up to a point. Nothing need be said about the memorandum I drew up. Admit it, and turn it into a joke. Say it was all talk."

Heberdon, who had pursued his own line of thought, affirmed abruptly. "Nedham is right. That's what I'm going to do."

Hanwell and Spurway still expostulated. The former suggested that they had all better leave town. Nedham patiently set to work to convince them, but Heberdon lost his temper.

"Hang it all!" he said irritably. "Can't you do what I say without any more argument? I'm the one that's got to be considered in this matter, aren't I?"

"Clumsy bungler!" muttered Spurway. Heberdon turned pale.

Nedham made haste to pour oil on the troubled waters. "Cut it out I Cut it out!" he said. "If we can't stop quarrelling among ourselves we're all done for!"

Hanwell and Spurway finally agreed to Nedham's suggestion.

Nedham asked: "What are you going to do about yesterday, Frank?"

"Establish an alibi," was the solemn reply. "Can you make it water-tight?"

"You leave that to me."

Having reached an agreement, they separated.

Heberdon continued in the cab to ex-Judge Palliser's office. Here, having no appointment, he had to wait for a miserable half-hour in the outer office, still in momentary expectation of a tap on the shoulder. When he was finally admitted to his uncle's sanctum he was paler than usual, and moist in his agitation. The older man, scenting trouble, instinctively adopted a defensive attitude.

"Judge" Palliser, as he was always called, was a typical successful lawyer who has been on the bench. Most lawyers when they ascend to that eminence take on flesh, mellow, and become rotund. It is the exercise of the wits that keeps men thin; lawyers have to think, and judges don't. Judge Palliser had a complexion like port wine, and a figure like a butt of malmsey. In voice he boomed unctuously, if one may be permitted the expression. His grand and single aim in life was to keep at bay the perplexities that interfere with a good digestion.

"Well, Frank!" he cried with the heartiness that he assumed as a cover for all sorts of real feelings. "How goes it?"

Heberdon, knowing his uncle, was not much heartened by the heartiness. "Well enough," he answered with a somewhat sickly attempt to appear at his ease. In his nervousness he plunged directly into the business that had brought him. "Have you read the papers to-day?"

"As much as I ever do," said the judge with a grand carelessness. "What about 'em?"

"That hold-up over in Princesboro yesterday," stammered Heberdon.

"Outrageous! Don't know what we're coming to, I'm sure! Nobody is safe nowadays. But that's nothing in our line, is, it?"

"Oh, no," said Heberdon feebly. "Have you read the evening papers?"

"Evening papers!" repeated the judge, staring. "It's only eleven o'clock in the morning!"

"Yes, I know. But they start coming out right after breakfast."

"Catchpenny rags!" was the scornful comment. "Battening for idle minds! I don't bother with newspapers during office hours."

It was impossible for Heberdon to find the words actually to open the business he had come on. Instead, he took the newspaper out of his pocket, and mutely called attention to the upsetting paragraph. Judge Palliser adjusted his glasses and read it through.

"Scandalous innuendo," he cried. "The newspapers love to start that sort of thing, confident they will never be called to account." Suddenly he looked sharply at his nephew. "Good God, Frank, you—you haven't got anything to do with this, have you?"

"Nothing, really," said Heberdon quickly. "But it's very unfortunate—"

"What do you mean? Don't whine!"

"Well, it's a fact," stammered the young man, "that some friends and I at the club got into an argument about crime one night—and I suppose a bell-boy overheard us—"

Judge Palliser turned pale under the fine network of purple veins that overspread his expansive countenance, and his eyes seemed to protrude a little farther. "And were you the one that took up the bet?" he asked.

"Yes—but—"

"Good God, Frank! You might at least have considered your family!"

"But it was all a joke," said Heberdon. "Only talk. None of us has ever thought of it since."

"Then what did you come to me for?" demanded the judge.

"Well, I suppose I'll be questioned," said Heberdon—to save his life he could not keep the whining tone out of his voice. "It's damned awkward. As it happens, I'm not in a position to establish an alibi for yesterday."

"H'm!" said his uncle, grimly studying him. Heberdon squirmed.

"Where were you yesterday?" demanded the elder.

Heberdon was ready with his tale. "I felt seedy," he explained glibly enough. "I went down to Brighton Beach for lunch and spent the afternoon on the sand. Just as luck would have it, I didn't meet a soul I knew."

"H'm!" said Judge Palliser again. "What can I do about it?"

Heberdon could not quite meet the irate eye. "Well, I thought—" he mumbled. "A man in your position—a word would be sufficient."

"Ah," said his uncle. "I take it you are suggesting that I perjure myself on your behalf."

"Where's the harm?" whined Heberdon. "If I had done anything wrong it would be different. But just an unlucky accident—you surely can't think there is anything in it!"

"Oh, no," said Judge Palliser. Heberdon was unable to decide whether his words concealed irony.

"And it would be damned unpleasant—for all of us, if they were to go on with the thing. I'm only thinking of you and the girls."

"That's kind of you!" This time there could be no doubt of the irony.

There was a silence while Judge Palliser stared grimly at Heberdon, and Heberdon twisted on his chair.

"What is it exactly that you want me to do?" the older man asked at last.

"If it could be shown that you knew where I was yesterday—or, better still, if I was with you—"

"Ah!"

Another silence.

"Where were you yesterday afternoon?" Heberdon ventured to ask.

"I went up to Chester Hills to play golf."

"Did you go up alone?"

"Yes."

Heberdon brightened. "Well, then, how simple—"

"Hold on a minute," said his uncle. "The money was recovered, if I remember aright?"

"What's that got to do with—" Heberdon began, but changed his mind under the look in his uncle's eye "Yes," he said meekly.

"And his pistol, when they took it from him—"

"Was unloaded."