RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

"Jack Chanty," Doubleday, Page & Co., New York, 1913

"Jack Chanty," Title Page

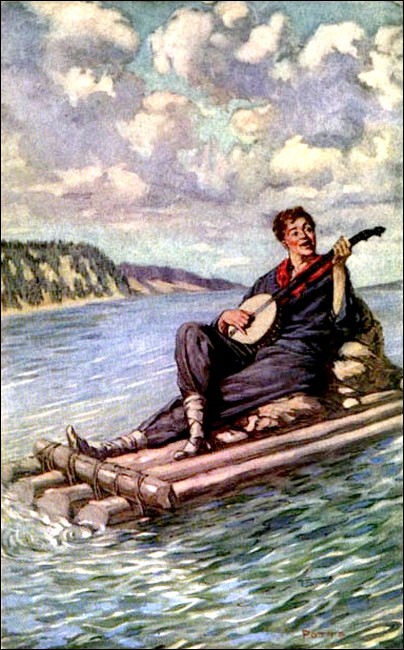

Frontispiece

Such was Jack Chanty, sprawling on his little raft

The surface of the wide, empty river rang with it like a sounding-board, and the undisturbed hills gave it back, the gay song of a deep-chested man. The musical execution was not remarkable, but the sound was as well suited to the big spaces of the sunny river as the call of a moose to the October woods, or the ululation of a wolf to a breathless winter’s night. The zest of youth and of singing was in it; to that the breasts of any singer’s hearers cannot help but answer.

“Oh! pretty Polly Oliver, the pri-ide of her sex;

The love of a grenadier he-er poor heart did vex.

He courted her so faithfu-ul in the good town of Bow,

But marched off to foreign lands a-fi-ighting the foe.”

The singer was luxuriously reclining on a tiny raft made of a single dry trunk cut into four lengths laced together with rope. His back was supported by two canvas bags containing his grub and all his worldly goods, and a banjo lay against his raised thighs. From afar on the bosom of the great stream he looked like a doll afloat on a shingle. The current carried him down, and the eddies waltzed him slowly around and back, providing him agreeable views up and down river and athwart the noble hills that hemmed it in.

“I cannot live si-ingle, and fa-alse I’ll not

prove,

So I’ll ’list for a drummer-boy and follow my love.

Peaked ca-ap, looped jacke-et, whi-ite gaiters and drum,

And marching so manfully to my tru-ue love I’ll come.”

Between each verse the banjo supplied a rollicking obbligato.

His head was bare, and the waves of his thick, sunburnt hair showed half a dozen shades ranging between sienna and ochre. As to his face, it was proper enough to twenty-five years old; an abounding vitality was its distinguishing character. He was not too good-looking; he had something rarer than mere good looks, an individuality of line and colouring. It was his own face, suggesting none of the recognized types of faces. He had bright blue eyes under beautifully modelled brows, darker than his hair. One eyebrow was cocked a little higher than the other, giving him a mocking air. In repose his lips came together in a thin, resolute line that suggested a hard streak under his gay youthfulness.

He was wearing a blue flannel shirt open at the throat, with a blue and white handkerchief knotted loosely away from it, and he had on faded blue overalls tucked into the tops of his mocassins. These mocassins provided the only touch of coxcombry to his costume; they were of the finest white doeskin elaborately worked with silk flowers. Such footwear is not for sale in the North, but may be surely construed as a badge of the worker’s favour.

Such was Jack Chanty, sprawling on his little raft, and abandoning himself to the delicious sunshine and the delights of song. It was July on the Spirit River; he was twenty-five years old, and the blood was coursing through his veins; inside his shirt he felt the weight of a little canvas bag of yellow gold, and he knew where there was plenty more to be had. Is it any wonder he was filled with a sense of wellbeing so keen it was almost a pain? Expanding his chest, he threw back his head and relieved himself of a roaring fortissimo that made the hills ring again:

“’Twas the battle of Ble-enheim, in a ho-ot

fusillade,

A poor little drummer-boy was a prisoner made.

But a bra-ave grenadier fou-ought hi-is way through the foe

And fifteen fierce Frenchmen toge-ether laid low.

“He took the boy tenderly in his a-arms as he

swooned,

He opened his ja-acket for to search for a wound.

Oh! pretty Polly Olive-er, my-y bravest, my bride!

Your true love shall nevermore be to-orn from your side!”

By and by the raft was carried around a wide bend, and the whitewashed buildings of Fort Cheever stole into view down the river. Jack’s eyes gleamed, and he put away the banjo. It was many a day since he had hobnobbed with his own kind, and what is the use of gold if there is no chance to squander it?

Sitting up, he applied himself to his paddle. Edging the raft toward the left-hand bank, he left the main current at the head of an island, and, shooting over a bar, paddled through the sluggish backwater on the shore of which the little settlement lay. As he came close the buildings were hidden from him by the high bank; only the top of the “company’s” flagpole showed. The first human sound that struck on his ears was the vociferous, angry crying of a boy-child.

Rounding a little point of the bank, the cause of the commotion was revealed. Jack grinned, and held his paddle. The sluggish current carried him toward the actors in the scene, and they were too intent to observe him. A half-submerged, flat-bottomed barge was moored to the shore. On the decked end of it a young girl in a blue print dress was seated on a box, vigorously soaping an infant of four. Two other ivory-skinned cupids, one older, one younger, were playing in the warm water that partly filled the barge. Their clothes lay in a heap behind the girl.

She was a very pretty girl; the mere sight of her caused Jack’s breast to lift and his heart to set up a slightly increased beating. It was so long since he had seen one! Her soft lips were determinedly pressed together; in one hand she gripped the thin arm of her captive, while with the other she applied the soap until his writhing little body flashed in the sun as if burnished. Struggles and yells were in vain. The other two children played in the water, callously indifferent to the sufferings of their brother. It was clear they had been through their ordeal.

The girl, warned of an approaching presence, raised a pair of startled eyes. Her captive, feeling the vise relax, plunged into the water of the barge with incredible swiftness, and, rapturously splashing off the hated soap, joined his brothers at the other end, safely out of her reach. The girl blushed for their nakedness. They themselves stared open-mouthed at the stranger without any embarrassment at all. The fat baby was sitting in the water, turned into stone with astonishment, like a statue of Buddha in a flood.

Something in the young man’s frank laugh reassured the girl, and she laughed a little too, though blushing still. She glowed with youth and health, deep-bosomed as Ceres, and all ivory and old rose. Her delicious, soft, roundness was a tantalizing sight to a hungry youth. But there was something more than mere provoking loveliness—her large brown eyes conveyed it, a disquieting wistfulness even while she laughed.

He brought his raft alongside the barge, and, rising, extended his hand according to the custom of the country. Hastily wiping her own soapy hand on her apron, she laid it in his. Both thrilled to the touch, and their eyes quailed from each other. Jack quickly recovered himself. Lovely as she might be, she was none the less a “native,” and therefore to a white man fair game. Naturally he took the world as he found it.

“You are Mary Cranston,” he said. “I should have known if there was another like you in the country,” his bold eyes added.

The girl lowered her eyes. “Yes,” she murmured.

Her voice astonished him, and filled him with the desire to make her speak again. “You don’t know who I am,” he said.

She glanced at the banjo case. “Jack Chanty,” she said softly.

“Good!” he cried. “That’s what it is to be famous!” Their eyes met, and they laughed as at a rich joke. Her laugh was as sweet as the sound of falling water in the ears of thirst, and the name he went by as spoken by her rang in his ears with rare tenderness.

“How did you know?” he asked curiously.

“Everybody knows about everybody up here,” she said. “There are so few! You came from across the mountains, and have been prospecting under Mount Tetrahedron since the winter. The Indians who came in to trade told us about the banjo, and about the many songs you sang, which were strange to them.”

The ardour of his gaze confused her. She broke off, and, to hide her confusion, turned abruptly to the staring ivory cupids. “Andy, come here!” she commanded in the voice of sisterly authority. “Colin! Gibbie! Come and get dressed!”

Andy and Colin grinned sheepishly, and stayed where they were. The smile of Andy, the elder, was toothless and exasperating. As for the infant Buddha, he continued to sit unmoved, to suck his thumb, and to stare.

She stamped her foot. “Andy! Come here this minute! Colin! Gibbie!” she repeated in a voice of helpless vexation.

They did not move.

“Look sharp, young ’uns!” Jack suddenly roared.

Of one accord, as if galvanized into life, they scrambled toward their sister, making a detour around the far side of the barge to avoid Jack.

Mary rewarded him with a smile, and dealt out the clothes with a practised hand. Andy, clasping his garments to his breast, set off over the plank to the shore, and was hauled back just in time.

“He has to have his hair cut, because the steamboat is coming,” his sister explained; “and I don’t see how I can hold on to him while I am dressing the others.”

“Pass him over here,” said Jack.

Andy, struck with terror, was deposited on the raft, whence escape was impossible without passing the big man, and commanded to dress himself without more ado.

Mary regarded the other two anxiously. “They’re beginning to shiver,” she said, “and I can’t dress both at once.”

Jack sat on the edge of the barge with his feet on the raft. “Give me the baby,” he said.

“You couldn’t dress a baby,” she said, with a provoking dimple in either cheek.

“Yes, I can, if he wears pants,” said Jack serenely. “There’s no mystery about pants.”

“Besides, he’d yell,” she objected.

“No, he won’t,” said Jack. “Try him and see.”

And in sooth he did not yell, but sat on Jack’s knee while his little shirt was pulled over his head and buttoned, sucking his thumb, and staring at Jack with a piercing, unflinching stare.

“You have a way with babies,” the girl said in the sweet, hushed voice that continually astonished him.

He looked at her with his mocking smile. “And with girls?” his eyes asked boldly.

She blushed, and attended strictly to Colin’s buttons.

Colin, fully attired in shirt, troussers, and moccasins, was presently dismissed over the plank. He lingered on the shore, shouting opprobrious epithets to his elder, still in captivity. At the same time the baby was dressed in the smallest pair of long pants ever made. He was as bow-legged as a bulldog. Jack leaned back, roaring with laughter at the figure of gravity he made. Gibbie didn’t mind. He could walk, but he preferred to sit. He continued to sit cross-legged on the end of the barge, and to stare.

Next, Andy was seated on the box, while Mary, kneeling behind him, produced her scissors.

“If you don’t sit still you’ll get the top of your ears cut off!” she said severely.

But sitting still was difficult under the taunts from ashore.

“Jutht you wait till I git aholt of you,” lisped the toothless one, proving that the language of unregenerate youth is much the same on the far-off Spirit River as it is on the Bowery.

Jack returned to the raft and unstrapped the banjo case. “Be a good boy and I’ll sing you a song,” he said, presumably to Andy, but looking at Mary meanwhile.

At the sound of the tuning-up the infant Buddha in long pants gravely arose stern foremost, and reseated himself at the edge of the barge, where he could get a better view of the player.

Jack chose another rollicking air, but a new tone had crept into his deep voice. He sang softly, for he had no desire to bring others down the bank to interrupt his further talk with Mary.

“Oh, the pretty, pretty creature!

When I next do meet her

No more like a clown will I face her frown,

But gallantly will I treat her,

But gallantly will I treat her,

Oh, the pretty, pretty creature!”

The infant Buddha condescended to smile, and to bounce once or twice on his fundament by way of applause. Andy sat as still as a surprised chipmunk.

Colin was sorry now that he had cut himself off from the barge. As for the boy’s big sister, she kept her eyes veiled, and plied the scissors with slightly languorous motions of the hands. Even a merry song may work a deal of sentimental damage under certain conditions. And the sun shone, and the bright river moved down.

“Thank you,” she said, when he had come to the end. “We never have music here.”

Jack wondered where she had learned her pretty manners.

The hair-cutting was concluded. Andy sprang up looking like a little zebra with alternate dark and light stripes running around his head, and a narrow bang like a forelock in the middle of his forehead. Jack put away the banjo, and Andy, seeing that there was to be no more music, set off in chase of Colin. The two of them disappeared over the bank. Mary gathered up towels, soap, comb, and scissors preparatory to following them.

“Don’t go yet,” said Jack eagerly.

“I must,” she said, but lingering. “There is much to be done before the steamboat comes.”

“She’s only expected,” said Jack of the knowledge born of experience. “It’ll be a week before she comes.” Mary displayed no great eagerness to be gone.

A bold idea had been making a covert shine in Jack’s eyes during the last minute or two. It suddenly found expression. “Cut my hair,” he blurted out.

She started and blushed. “Oh, I—I couldn’t cut a man’s hair,” she stammered.

“What’s the difference?” demanded Jack with a great parade of innocence. “Hair is just hair, isn’t it?”

“I couldn’t,” she repeated naively. “It would confuse me so!”

The thought of her confusion was delicious to him. He was standing below her on the raft. “Look,” he said, lowering his head. “It needs it. I’m a sight!”

Since in this position he could not see her face, she allowed her eyes to dwell for a moment on the tawny silken sheaves that he exhibited. Such bright hair was wonderful to her. It seemed to her as if the sun itself was netted in its folds.

“I—I couldn’t,” she repeated, but weakly.

He swung about and sat on the edge of the barge. “Make out I am your other little brother,” he said insinuatingly. “I can’t see you, so it’s all right. Ju’st one little snip to see how it goes!”

The temptation was too great to be resisted. She bent over, and the blades of the scissors met. In her agitation she cut a wider swath than she intended and a whole handful of hair fell to the deck.

“Oh!” she cried remorsefully.

“Now you’ll have to do the whole thing,” said Jack quickly. “You can’t leave me looking like a half-clipped poodle.”

With a guilty look over her shoulder she drew up the box and sat down behind him. Gibbie, the youngest of the Cranstons, was a solemn and interested spectator. Jack thrilled a little and smiled at the touch of her trembling fingers in his hair. At the same time he was not unaware of the decorative value of his luxuriant thatch, and it occurred to him he was running a considerable risk of disfigurement at her hands.

“Not so short as Andy’s,” he suggested anxiously.

“I will be careful,” she said.

The scissors snipped busily, and the rich yellow-brown hair fell all around the deck. Mary eyed it covetously. One shining twist of it dropped in her lap. He could not see her. In a twinkling it was stuffed inside her belt.

Meanwhile Jack continued to smile with softened eyes. “Hair-cutting was never like this,” he murmured. He was tantalized by the recollection of her voice, and he cast about in his mind for something to lead her to talk more freely. “You were not here when I came through two years ago,” he said.

“I was away at school,” she said.

“Where?”

“The mission at Caribou Lake.”

“Did you like it there?”

He felt the shrug in her finger-tips. “It is the best there is,” she said quietly.

“It’s a shame!” said Jack. There was a good deal unspoken here. “A shame you should be obliged to associate with those savages,” he implied, and she understood.

“Have you ever been outside?” he asked.

“No,” she said.

“Would you like to go?”

“Yes, with somebody I liked,” she said in her simple way.

“With me?” he asked in the off-hand tone that may be taken any way the hearer pleases.

Her simplicity was not dullness. “No,” she said quickly. “You would tell me funny lies about everything.”

“But you would laugh, and you would like it,” he said.

She had nothing to say to this.

“Outside they have regular shops for shaving and cutting hair,” he went on. “Barber-shops they are called.”

“I know,” she said offended. “I read.”

“I’ll bet you didn’t know there was a lady barber in Prince George.”

“Nice kind of lady!” she said.

The obvious retort slipped thoughtlessly off his tongue. “I like that! What are you doing?”

Her eyes filled with tears, and the scissors faltered. “Well, I wouldn’t do it for—I—I wouldn’t do it all the time,” she murmured deeply hurt.

He twisted his head at the imminent risk of impaling an eye on the scissors. The tears astonished him.

Everything about her astonished him. In no respect did she coincide with his experience of “native” girls. He was vain enough for a good-looking young man of twenty-five, but he did not suspect that to a lonely and imaginative girl his coming down the river might have had all the effect of the advent of the yellow haired prince in a fairy-tale. Jack was not imaginative.

He reached for her free hand. “Say, I’m sorry,” he said clumsily. “It was only a joke! It’s mighty decent of you to do it for me.”

She snatched her hand away, but smiled at him briefly and dazzlingly. She was glad to be hurt if he would let that tone come into his mocking voice.

“I was just silly,” she said shortly.

The hair-cutting went on.

“What do you read?” asked Jack curiously.

“We get newspapers and magazines three times a year by the steamboat,” she said. “And I have a few books. I like ‘Lalla Rookh’ and ‘Marmion’ best.” Jack, who was not acquainted with either, preserved a discreet silence.

“Father has sent out for a set of Shakespeare for me,” she went on. “I am looking forward to it.”

“It’s better on the stage,” said Jack. “What fun to take you to the theatre!”

She made no comment on this. Presently the scissors gave a concluding snip.

“Lean over and look at yourself in the water,” she commanded.

Obeying, he found to his secret relief that his looks had not suffered appreciably. “That’s out of sight!” he said heartily, turning to her. “I say, I’m ever so much obliged to you.”

An awkward silence fell between them. Jack’s growing intention was clearly evident in his eye, but she did not look at him.

“I—I must pay you,” he said at last, a little breathlessly.

She understood that very well, and sprang up, the scissors ringing on the hollow deck. They were both pale. She turned to run, but the box was in her way. Leaping from the raft to the barge, he caught her in his arms, and as she strained away he kissed her round firm cheek and her fragrant neck beneath the ear. He roughly pressed her averted head around, and crushed her soft lips under his own.

Then she got an arm free, and he received a short-arm box on the ear that made his head ring. She tore herself out of his arms, and faced him from the other side of the barge, panting and livid with anger.

“How dare you! How dare you!” she cried.

Jack leaned toward her, breathing no less quickly than she. “You’re lovely! You’re lovely,” he murmured swiftly. “I never saw anybody like you before. I’ll camp quarter of a mile down river, out of the way. Come down to-night, and I’ll sing to you.”

“I won’t!” she cried. “I’ll never speak to you again! I hate you!” She indicated the unmoved infant Buddha with a tragic gesture. “And before the baby, too!” she cried. “Aren’t you ashamed of yourself?”

Jack laughed a little sheepishly. “Well, he’s too young to tell,” he said.

“But what will he think of me?” she cried despairingly. Stooping, she swept the little god into her arms, and, running over the plank, disappeared up the bank.

“I’ll be waiting for you,” Jack softly called after her. She gave no sign of hearing.

Jack sat down on the edge of the barge again. He brushed the cut hair into the water, and watched it float away with an abstracted air. As he stared ahead of him a slight line appeared between his eyebrows which may have been due to compunction. Whatever the uncomfortable thought was, he presently whistled it away after the manner of youth, and, drawing his raft up on the stones, set to work to take stock of his grub.

The Hudson Bay Company’s buildings at Fort Cheever were built, as is customary, in the form of a hollow square, with one side open to the river. The store occupied one side of the square, the warehouse was opposite, and at the top stood the trader’s house in the midst of its vegetable garden fenced with palings. The old palisade about the place had long ago disappeared, and nothing military remained except the flagpole and an ancient little brass cannon at its foot, blackened with years of verdigris and dirt. The humbler store of the “French outfit” and the two or three native shacks that completed the settlement lay at a little distance behind the company buildings, and the whole was dropped down on a wide, flat esplanade of grass between the steep bare hills and the river.

To-day at the fort every one was going about his business with an eye cocked downstream. Every five minutes David Cranston came to the door of the store for a look, and old Michel Whitebear, hoeing the trader’s garden, rested between every hill of potatoes, to squint his aged eyes in the same direction. Usually this state of suspense endured for days, sometimes weeks, but upon this trip the river-gods were propitious, and at five o’clock the eagerly listened for whistle was actually heard.

Every soul in the place gathered at the edge of the bank to witness the arrival. At one side, slightly apart, stood the trader and his family. David Cranston was a lean, up-standing Scotchman, an imposing physical specimen with hair and beard beginning to grizzle, and a level, grim, sad gaze. His wife was a handsome, sullen, dark-browed, half-breed woman, who, unlike the majority of her sisters, carried her age well. In his grim sadness and her sullenness was written a domestic tragedy of long-standing. After all these years she was still a stranger in her own house, and an alien to her husband and children. Their children were with them, Mary and six boys ranging from Davy, who was sixteen, down to the infant Buddha.

A small crowd of natives in ragged store clothes, standing and squatting on the bank, and spilling over on the beach below, filled the centre of the picture, and beyond them sat Jack Chanty by himself, on a box that he had carried to the edge of the bank. Between him and Mary the bank made in, so that they were fully visible to each other, and both tinglingly self-conscious. In Jack this took the form of an elaborately negligent air. He whittled a paddle with nice care, glancing at Mary from under his lashes. She could not bring herself to look at him.

While the steamboat was still quarter of a mile downstream, the people began to sense that there was something more than usual in the wind, and a great excitement mounted. We of the outside world, with our telegrams and newspapers and hourly posts, have forgotten what it is to be dramatically surprised. Where can we get a thrill like to that which animated these people as the magic word was passed around: “Passengers!” Presently it could be made out that these were no ordinary passengers, but a group of well-dressed gentlemen, and finally, wonder of wonders! what had never been seen at Fort Cheever before, a white lady—no, two of them!

Mary saw them first, two ladies, corseted, tailored, and marvellously hatted like the very pictures in the magazines that she had secretly disbelieved in. In another minute she made out that one of them, leaning on the upper rail, smiling and chatting vivaciously with her companions, was as young as Mary herself, and as slender and pretty as a mundane fairy.

Mary glanced swiftly at Jack. He, too, was looking at the deck of the steamboat and he had stopped whittling his paddle. A dreadful pang transfixed Mary’s breast. Her hands and feet suddenly became enormous to her, and her body seemed like a coarse and shapeless lump. She looked down at her clean, faded print dress; she could have torn it into ribbons. She looked at her dark-browed mother with eyes full of a strange, angry despair. The elder woman had by this time seen what was coming, and her lip curled scornfully. Mary’s eyes filled with tears. She slipped out of the group unseen, and, running back to the house, cast herself on her bed and wept as she had never wept.

The steamboat was moored alongside the half-submerged barge. She came to a stop with the group on the upper deck immediately in front of Jack and a little below him. True to the character of indifference he was fond of assuming, he went on whittling his paddle. At the same time he was taking it all in. The sight of people such as his own people, that he thought he had put behind him forever, raised a queer confusion of feelings in him. As he covertly watched the dashing, expensive, imperious little beauty and three men hanging obsequiously on her words, a certain hard brightness showed briefly in his eyes, and his lips thinned.

It was as if he said: “Aha! my young lady, I know your kind! None of you will ever play that game again with me!”

Consequently when her casual glance presently fell on the handsome, young, rough character (as she would no doubt have called him) it was met by a glance even more casual. The young man was clearly more interested in the paddle he was making than in her. Her colour heightened a little and she turned with an added vivacity to her companions. After a long time she looked again. The young man was still intent upon his paddle.

The first to come off the boat was the young purser, who hurried with the mail and the manifests to David Cranston. He was pale under the weight of the announcement he bore.

“We have his honour the lieutenant-governor and party on board,” he said breathlessly.

Cranston, because he saw that he was expected to be overcome, remained grimly unconcerned. “So!” he said coolly.

The youngster stared. “The lieutenant-governor,” he repeated uncertainly. “He’s landing here to make some explorations in the mountains. He joined us without warning at the Crossing. There was no way to let you know.”

“We’ll do the best we can for his lordship,” said Cranston with an ironic curl to his grim lips. “I will speak to my wife.”

To her he said under his breath, grimly but not unkindly, “Get to the house, my girl.”

She flared up with true savage suddenness. “So, I’m not good enough to be seen with you,” she snarled, taking no pains to lower her voice. “I’m your lawful wife. These are my children. Are you ashamed of my colour? You chose me!”

Cranston drew the long breath that calls on patience. “’Tis not your colour that puts me to shame, but your manners,” he said sternly. “And if they’re bad,” he added, “it’s not for the lack of teaching. Get to the house!”

She went.

The captain of the steamboat now appeared on the gangplank, ushering an immaculate little gentleman whose sailent features were a Panama hat above price, a pointed white beard, neat, agile limbs, and a trim little paunch under a miraculously fitting white waistcoat. Two other men followed, one elderly, one young. Cranston waited for them at the top of the path.

The captain was a little flustered too. “Mr. Cranston, gentlemen, the company’s trader here,” he said. “His Honour Sir Bryson Trangmar, the lieutenant-governor of Athabasca,” he went on. “Captain Vassall”—the younger man bowed; “Mr. Baldwin Ferrie”—the other nodded.

There was the suspicion of a twinkle in Cranston’s eye. Taking off his hat he extended an enormous hand. “How do you do, sir,” he said politely. “Welcome to Fort Cheever.”

“Charmed! Charmed!” bubbled the neat little gentleman. “Charming situation you have here. Charming river! Charming hills!”

“I regret that I cannot offer you suitable hospitality,” Cranston continued in his great, quiet voice. “My house is small, as you see, and very ill-furnished. There are nine of us. But the warehouse shall be emptied before dark and made ready for you. It is the best building here.”

“Very kind, I’m sure,” said Sir Bryson with offhand condescension—perhaps he sensed the twinkle, perhaps it was the mere size of the trader that annoyed him; “but we have brought everything needful. We will camp here on the grass between the buildings and the river. Captain Vassall, my aide-de-camp, will see to it. I will talk to you later Mr.—er?”

“Cranston,” murmured the aide-de-camp.

Cranston understood by this that he was dismissed. He sauntered back to the store with a peculiar smile on his grim lips. In the free North country they have never become habituated to the insolence of office, and the display of it strikes them as a very humorous thing, particularly in a little man.

Sir Bryson and the others reconnoitred the grassy esplanade, and chose a spot for the camp. It was decided that the party should remain on the steamboat all night, and go into residence under canvas next day. They then returned on board for supper, and nothing more was seen of the strangers for a couple of hours.

At the end of that time Miss Trangmar and her companion, Mrs. Worsley, arm in arm and hatless, came strolling over the gangplank to enjoy a walk in the lingering evening. At this season it does not become dark at Fort Cheever until eleven.

Jack’s raft was drawn up on the beach at the steamboat’s bow, and as the ladies came ashore he was disposing his late purchases at the store upon it, preparatory to dropping downstream to the spot where he meant to camp. In order to climb the bank the two had to pass close behind him.

At sight of him the girl’s eyes brightened, and, with a mischievous look she said something to her companion. “Linda!” the older woman remonstrated. “Everybody speaks to everybody up here,” said the girl. “It was understood that the conventions were to be left at home.”

Thus Jack was presently startled to hear a clear high voice behind him say: “Are you going to travel on the river with that little thing?”

Hastily straightening his back and turning, he raised his hat. Her look took him unawares. There was nothing of the insolent queenliness in it now. She was smiling at him like a fearless, well-bred little girl. Nevertheless, he reflected, the sex is not confined to the use of a single weapon, and he stiffened.

“I came down the river on it this morning,” he said politely and non-committal. “To-night I’m going just a little way to camp.”

She was very like a little girl, he thought, being so small and slender, and having such large blue eyes, and such a charming, childlike smile. Her bright brown hair was rolled back over her ears. Her lips were very red, and her teeth perfect. She was wearing a silk waist cunningly contrived with lace, and fitting in severe, straight lines, ever so faintly suggesting the curves beneath. In spite of himself everything about her struck subtle chords in Jack’s memory. It was years since he had been so close to a lady.

She was displeased with the manner of his answer. He had shown no trace either of the self-consciousness or the eager complaisance she had expected from a local character. Indeed, his gaze returned to the raft as if he were only restrained by politeness from going on with his preparations. He reminded her of a popular actor in a Western play that she had been to see more times than her father knew of. But the rich colour in Jack’s cheek and neck had the advantage of being under the skin instead of plastered on top. Her own cheeks were a thought pale.

“How do you go back upstream?” she asked with an absent air that was intended to punish him.

“You travel as you can,” said Jack calmly. “On horseback or afoot.”

She pointedly did not wait for the answer, but strayed on up the path as if he had already passed from her mind. Yet as she turned at the top her eyes came back to him as if by accident. She had a view of a broad back, and a bent head intent upon the lashings of the raft. She bit her lip. It was a disconcerting young man.

A few minutes later Frank Garrod, the governor’s secretary, who until now had been at work in his cabin upon the correspondence the steamboat was to take back next day, came over the gangplank in pursuit of the ladies. He was a slim and well-favoured young man, of about Jack’s age, but with something odd and uncontrolled about him, a young man of whom it was customary to say he was “queer,” without any one’s knowing exactly what constituted his queerness. He had black hair and eyes that made a striking contrast with his extreme pallor. The eyes were very bright and restless; all his movements were a little jerky and uneven.

Hearing more steps behind him, Jack looked around abstractedly without really seeing what he looked at. Garrod, however, obtained a fair look into Jack’s face, and the sight of it operated on him with a terrible, dramatic suddenness. A doctor would have recognized the symptoms of what he calls shock. Garrod’s arms dropped limply, his breath failed him, his eyes were distended with a wild and inhuman fear. For an instant he seemed about to collapse on the stones, but he gathered some rags of self-control about him, and, turning without a sound, went back over the gangplank, swaying a little, and walking with wide-open, sightless eyes like a man in his sleep.

Presently Vassall, the amiable young A. D. C., descending the after stairway, came upon him leaning against the rail on the river-side of the boat, apparently deathly sick.

“Good heavens, Garrod! What’s the matter?” he cried.

The other man made a pitiable attempt to carry it off lightly. “Nothing serious,” he stammered. “A sudden turn. I have them sometimes. If you have any whiskey—”

Vassall sprang up the stairway, and presently returned with a flask. Upon gulping down part of the contents, a little colour returned to Garrod’s face, and he was able to stand straighter.

“All right now,” he said in a stronger voice. “You run along and join the others. Please don’t say anything about this.”

“I can’t leave you like this,” said Vassall. “You ought to be in bed.”

“I tell you I’m all right,” said Garrod in his jerky, irritable way. “Run along. There isn’t anything you can do.”

Vassall went his way with a wondering air; real tragedy is such a strange thing to be intruding upon our everyday lives. Garrod, left alone, stared at the sluggishly flowing water under the ship’s counter with the kind of sick, desirous eyes that so often look over the parapets of bridges in the cities at night. But there were too many people about on the boat; the splash would instantly have betrayed him.

He gathered himself together as with an immense effort, and, climbing the stairway, went to his stateroom. There he unlocked his valise, and drawing out his revolver, a modern hammerless affair, made sure that it was loaded, and slipped it in his pocket. He caught sight of his face in the mirror and shuddered. “As soon as it’s dark,” he muttered.

He sat down on his bunk to wait. By and by he became conscious of a torturing thirst, and he went out into the main cabin for water. Jack, meanwhile, having loaded his craft, had boarded the steamboat to see if he could beg or steal a newspaper less than two months old, and the two men came face to face in the saloon.

Garrod made a move to turn back, but it was too late; Jack had recognized him now. Seeing the look of amazement in the other’s face, Garrod’s hand stole to his hip-pocket, but it was arrested by the sound of Jack’s voice.

“Frank!” he cried, and there was nothing but gladness in the sound. “Frank Garrod, by all that’s holy!” He sprang forward with outstretched hands. “Old Frank! To think of finding you here!”

Garrod stared in stupid amazement at the smile and the hearty tone. For a moment he was quite unnerved; his hands and his lips trembled. “Is it —is it Malcolm Piers?” he stammered.

“Sure thing!” cried Jack, wringing his hand. “What’s the matter with you? You look completely knocked up at the sight of me. I’m no ghost, man! What are you doing up here.”

“I’m Sir Bryson’s secretary,” murmured Garrod, feeling for his words with difficulty.

Jack’s delight was as transparent as it was unrestrained. The saloon continued to ring with his exclamations. In the face of it a little steadiness returned to Garrod, but he could not rid his eyes of their amazement and incredulity at every fresh display of Jack’s gladness.

“You’re looking pretty seedy,” Jack broke off to say. “Going the pace, I expect. Now that we’ve got you up here, you’ll have to lead a more godly and regular life, my boy.”

“What are you doing up here, Malcolm?” asked Garrod dully.

“Easy with that name around here, old fel’,” said Jack carelessly. “I left it off long ago. I’m just Jack Chanty now. It’s the name the fellows gave me themselves because I sing by the campfires.”

“I understand,” said Garrod, with a jerk of eagerness. “Good plan to drop your own name, knocking around up here.”

“I had no reason to be ashamed of it,” said Jack quickly. “But it’s too well known a name in the East. I didn’t want to be explaining myself all the time. It was nobody’s business, anyway, why I came out here. So I let them call me what they liked.”

“Of course,” said Garrod.

“Knock around,” cried Jack. “That’s just what I do! A little river work, a little prospecting, a little hunting and trapping, and one hell of a good time! It beats me how young fellows of blood and muscle can stew their lives away in cities when this is open to them! New country to explore, and game to bring down, and gold to look for. The fun of it, whether you find any or not! This is freedom, Frank, working with your own hands for all you get, and beholden to no man! By Gad! I’m glad I found you,” he went on enthusiastically. “What talks we’ll have about people and the places back home! I never could live there now, but I’m often sick to hear about it all. You shall tell me!”

A tremor passed over Garrod’s face. “Sure,” he said nervously. “I can’t stop just this minute, because they’re waiting for me up on the bank. But I’ll see you later.”

“To-morrow, then,” said Jack easily; but his eyes followed the disappearing Garrod with a surprised and chilled look. “What’s the matter with him?” they asked.

Garrod as he hurried ashore, his hands trembling, and his face working in an ecstasy of relief, murmured over and over to himself. “He doesn’t know! He doesn’t know!”

Jack was sitting by his own fire idly strumming on the banjo. Behind him was his canvas “lean-to,” open to the fire in front, and with a mosquito bar hanging within. All around his little clearing pressed a thick growth of young poplar, except in front, where the view was open to the river, moving smoothly down, and presenting a burnished silver reflection to the evening sky. The choice of a situation, the proper fire, and the tidy arrangements all bespoke the experienced campaigner. Jack took this sort of thing for granted, as men outside ride back and forth on trolley cars, and snatch hasty meals at lunch counters.

The supper dishes being washed, it was the easeful hour of life in camp, but Jack was not at ease. He played a few bars, and put the banjo down. He tinkered with the fire, and swore when he only succeeded in deadening it. He lit his pipe, and immediately allowed it to go out again. A little demon had his limbs twitching on wires. He continually looked and listened in the direction of the fort, and whenever he fancied he heard a sound his heart rose and beat thickly in his throat. At one moment he thought: “She’ll come,” and confidently smiled; the next, for no reason: “She will not come,” and frowned, and bit his lip.

Finally he did hear a rustle among the trees. He sprang up with surprised and delighted eyes, and immediately sat down again, picking up the banjo with an off-hand air. Under the circumstances one’s pet affectation of unconcern is difficult to maintain.

It was indeed Mary. She broke into the clearing, pale and breathless, and looked at Jack as if she was all ready to turn and fly back again. Jack smiled and nodded as if this were the most ordinary of visits. The smile stiffened in his face, for another followed her into the clearing— Davy, the oldest of her brothers. For an instant Jack was nonplussed, but he had laid it down as a rule that in his dealings with the sex, whatever betide, a man must smile and keep his temper. So, swallowing his disappointment as best he could, he greeted Davy as if he had expected him too.

What Mary had been through during the last few hours may be imagined: how many times she had sworn she would not go, only to have her desires open the question all over again. Perhaps she would not have come if the maddeningly attractive young lady had not appeared on the scene; perhaps she would have found an excuse to come anyway. Be that as it may, she had brought Davy. In this she had not Mrs. Grundy’s elaborate code to guide her; it was an idea out of her own head—or an instinct of her heart, rather. Watching Jack eagerly and covertly to see how he took it, she decided that she had done right. “He will think more of me,” she thought with a breath of relief.

She had done wisely of course. Jack, after his first disappointment, was compelled to doff his cap to her. He had never met a girl of the country like this. He bestirred himself to put his visitors at their ease.

“I will make tea,” he said, reaching for the copper pot according to the ritual of politeness in the North.

“We have just had tea,” Mary said. “Davy will smoke with you.”

Mary was now wearing a shawl over the print dress, but instead of clutching it around her in the clumsy native way, she had crossed it on her bosom like a fichu, wound it about her waist, and tucked the ends in. Jack glanced at her approvingly.

Davy was young for his sixteen years, and as slender as a sapling. He had thin, finely drawn features, and eyes that expressed something of the same quality of wistfulness as his sister’s. At present he was very ill at ease, but his face showed a certain resoluteness that engaged Jack’s liking. The boy shyly produced a pipe that was evidently a recent acquisition, and filled it inexpertly.

Jack’s instinct led him to ignore Mary for the present while he made friends with the boy. He knew how. They were presently engaged in a discussion about prairie chicken, in an off-hand, manly tone.

“Never saw ’em so plenty,” said Davy. “You only have to climb the hill to bring back as many as you want.”

“What gun do you use?” asked Jack.

The boy’s eyes gleamed. “My father has a Lefever gun,” he said proudly. “He lets me use it.”

“So!” said Jack, suitably impressed. “There are not many in the country.”

“She’s a very good gun,” said Davy patronizingly. “I like to take her apart and clean her,” he added boyishly.

“I’d like to go up on the prairie with you while I’m here,” said Jack. “But I have no shotgun. I’ll have to try and put their eyes out with my twenty-two.” This sort of talk was potent to draw them together. They puffed away, ringing all the changes on it. Mary listened apart as became a mere woman, and the hint of a dimple showed in either cheek. When she raised her eyes they fairly beamed on Jack.

Jack knew that the way to win the hearts of the children of the North is to tell them tales of the wonderful world outside that they all dream about. He led the talk in this direction.

“I suppose you’ve finished school,” he said to Davy, as man to man. “Do you ever think of taking a trip outside?”

The boy hesitated before replying. “I think of it all the time,” he said in a low, moved voice. “I feel bad every time the steamboat goes back without me. There is nothing for me here.”

“You’ll make it some day soon,” said Jack heartily.

“I suppose you know Prince George well?” the boy said wistfully.

“Yes,” said Jack, “but why stop at Prince George? That’s not much of a town. You should see Montreal. That’s where I was raised. There’s a city for you! All built of stone. Magnificent banks and stores and office buildings ten, twelve, fourteen stories high, and more. You’ve seen a two-story house at the lake; imagine seven of them piled up one on top of another, with people working on every floor!”

“You’re fooling us,” said the boy. His and his sister’s eyes were shining.

“No, I have seen pictures of them in the magazines,” put in Mary quickly.

“There is Notre Dame Street,” said Jack dreamily, “and Great St. James, and St. Catherine’s, and St. Lawrence Main; I can see them now! Imagine miles of big show-windows lighted at night as bright as sunshine. Imagine thousands of moons hung right down in the street for the people to see by, and you have it!”

“How wonderful!” murmured Mary.

“There is an electric light at Fort Ochre,” said the boy, “but I have not seen it working. They say when the trader claps his hands it shines, and when he claps them again it goes out.”

Mary blushed for her brother’s ignorance. “That’s only to fool the Indians,” she said quickly. “Of course there’s some one behind the counter to turn it off and on.”

Jack told them of railway trains and trolley cars; of mills that wove thousands of yards of cloth in a day, and machines that spit out pairs of boots all ready to put on. The old-fashioned fairy-tales are puerile beside such wonders as these—think of eating your dinner in a carriage that is being carried over the ground faster than the wild duck flies!— moreover, he assured them on his honour that it was all true.

“Tell us about theatres,” said Mary. “The magazines have many stories about theatres, but they do not explain what they are.”

“Well, a theatre’s a son-of-a-gun of a big house with a high ceiling and the floor all full of chairs,” said Jack. “Around the back there are galleries with more chairs. In the front there is a platform called the stage, and in front of the stage hangs a big curtain that is let down while the people are coming in, so you can’t see what is behind it. It is all brightly lighted, and there’s an orchestra, many fiddles and other kinds of music playing together in front of the stage. When the proper time comes the curtain is pulled up,” he continued, “and you see the stage all arranged like a picture with beautifully painted scenery. Then the actors and actresses come out on the stage and tell a story to each other. They dance and sing, and make love, and have a deuce of a time generally. That’s called a play.”

“Is it nothing but making love?” asked Davy. “Don’t they have anything about hunting, or having sport?”

“Sure!” said Jack. “War and soldiers and shooting, and everything you can think of.”

“Are the actresses all as pretty as they say?” asked Mary diffidently.

“Not too close,” said Jack. “But you see the lights, and the paint and powder, and the fine clothes show them up pretty fine.”

“It gives them a great advantage,” she commented. Mary had other questions to ask about actresses. Davy was not especially interested in this subject, and soon as he got an opening therefor he said, looking sidewise at the leather case by the fire:

“I never heard the banjo played.”

Jack instantly produced the instrument, and, tuning it, gave them song after song. Brother and sister listened entranced. Never in their lives had they met anybody like Jack Chanty. He was master of an insinuating tone not usually associated with the blatant banjo. Without looking at her, he sang love-songs to Mary that shook her breast. In her wonder and pleasure she unconsciously let fall the guard over her eyes, and Jack’s heart beat fast at what he read there.

Warned at last by the darkness, Mary sprang up. “We must go,” she said breathlessly.

Davy, who had come unwillingly, was more unwilling to go. But the hint of “father’s” anger was sufficient to start him.

Jack detained Mary for an instant at the edge of the clearing. He dropped the air of the genial host. “I shall not be able to sleep to-night,” he said swiftly.

“Nor I,” she murmured. “Th—thinking of the theatre,” she added lamely.

“When everybody is asleep,” he pleaded, “come outside your house. I’ll be waiting for you. I want to talk to you alone.”

She made no answer, but raised her eyes for a moment to his, two deep, deep pools of wistfulness. “Ah, be good to me! Be good to me,” they seemed to plead with him. Then she darted after her brother.

The look sobered Jack, but not for very long. “She’ll come,” he thought exultingly.

Left alone, he worked like a beaver, chopping and carrying wood for his fire. Under stress of emotion he turned instinctively to violent physical exertion for an outlet. He was more moved than he knew. In an hour, being then as dark as it would get, he exchanged the axe for the banjo, and, slinging it over his back, set forth.

The growth of young poplar stretched between his camp and the esplanade of grass surrounding the buildings of the fort. When he came to the edge of the trees the warehouse was the building nearest to him. Running across the intervening space, he took up his station in the shadow of the corner of it, where he could watch the trader’s house. A path bordered by young cabbages and turnips led from the front door down to the gate in the palings. The three visible windows of the house were dark. At a little distance behind the house the sledge dogs of the company were tethered in a long row of kennels, but there was little danger of their giving an alarm, for they often broke into a frantic barking and howling for no reason except the intolerable ennui of their lives in the summer.

There is no moment of the day in lower latitudes that exactly corresponds to the fairylike night-long summer twilight of the North. The sunset glow does not fade entirely, but hour by hour moves around the Northern horizon to the east, where presently it heralds the sun’s return. It is not dark, and it is not light. The world is a ghostly place. It is most like nights at home when the full moon is shining behind light clouds, but with this difference, that here it is the dimness of a great light that embraces the world, instead of the partial obscurity of a lesser.

Jack waited with his eyes glued to the door of the trader’s house. There was not a breath stirring. There were no crickets, no katydids, no tree-toads to make the night companionable; only the hoot of an owl, and the far-off wail of a coyote to put an edge on the silence. It was cold, and for the time being the mosquitoes were discouraged. The stars twinkled sedulously like busy things.

Jack waited as a young man waits for a woman at night, with his ears strained to catch the whisper of her dress, a tremor in his muscles, and his heart beating thickly in his throat. The minutes passed heavily. Once the dogs raised an infernal clamour, and subsided again. A score of times he thought he saw her, but it was only a trick of his desirous eyes. He became cold to the bones, and his heart sunk. As a last resort he played the refrain of the last song he had sung her, played it so softly none but one who listened would be likely to hear. The windows of the house were open.

Then suddenly he sensed a figure appearing from behind the house, and his heart leapt. He lost it in the shadow of the house. He waited breathlessly, then played a note or two. The figure reappeared, running toward him, still in the shadow. It loomed big in the darkness. It started across the open space. Too late Jack saw his mistake. He had only time to fling the banjo behind him, before the man was upon him with a whispered oath.

Jack thought of a rival, and his breast burned. He defended himself as best as he could, but his blows went wide in the darkness. The other man was bigger than he, and nerved by a terrible, quiet passion. To save himself from the other’s blows Jack clinched. The man flung him off. Jack heard the sharp impact of a blow he did not feel. The earth leapt up, and he drifted away on the swirling current of unconsciousness.

What happened after that was like the awakening from a vague, bad dream. He had first the impression of descending a long and tempestuous series of rapids on his flimsily hung raft, to which he clung desperately. Then the scene changed and he seemed to be floating in a ghastly void. He thought he was blind. He put out his hand to feel, and his palm came in contact with the cool, moist earth, overlaid with bits of twig and dead leaves, and sprouts of elastic grass. The earth at least was real, and he felt of it gratefully, while the rest of him still teetered in emptiness.

Then he became conscious of a comfortable emanation, as from a fire; sight returned, and he saw that there was a fire. It had a familiar look; it was the fire he himself had built some hours before. He felt himself, and found that he was covered by his own blanket. “I have had a nightmare,” he thought mistily. Then a voice broke rudely on his vague fancies, bringing the shock of complete recollection in its train.

“So, you’re coming ’round all right,” it said grimly.

At his feet, Jack saw David Cranston sitting on a log.

“I’ve put the pot on,” he continued. “I’ll have a sup of tea for you in a minute. I didn’t mean to hit you so hard, my lad, but I was mad.”

Jack turned his head, and hid it in his arm. Dizzy, nauseated, and shamed, he was as near blubbering at that moment as a self-respecting young man could let himself get in the presence of another man.

“Clean hit, point of the jaw,” Cranston went on. “Nothing broke. You’ll be as right as ever with the tea.”

He made it, and forced Jack to drink of the scalding infusion. In spite of himself, it revived the young man, but it did not comfort his spirit any.

“I’m all right now,” he muttered, meaning: “You can go!”

“I’ll smoke a pipe wi’ you,” said Cranston imperturbably. “I want a bit of a crack wi’ you.” Seeing Jack’s scowl, he added quickly: “Lord! I’m not going to preach over you, lying there. You tried to do me an injury, a devilish injury, but the mad went out wi’ the blow that stretched ye. I wish to do you justice. I mind as how I was once a young sprig myself, and hung around outside the tepees at night, and tried to whistle the girls out. But I never held by such a tingle-pingle contraption as that,” he said scornfully, pushing the banjo with his foot. “To my mind it’s for niggers and Eye-talians. ’Tis unmanly.”

Jack raised his head. “Did you break it?” he demanded scowling.

“Nay,” said Cranston coolly. “I brought it along wi’ you. It’s property, and I spoil nothing that is not my own.”

There was a silence. Cranston with the greatest deliberation, took out his pipe and stuck it in his mouth; produced his plug of tobacco, shaved it nicely, and put it away again; rolled the tobacco thoroughly between his palms, and pressed it into the bowl with a careful forefinger. A glowing ember from the fire completed the operation. For five minutes he smoked in silence, occasionally glancing at Jack from under heavy brows.

“Have ye anything to say?” he asked at last.

“No,” muttered Jack.

There was another silence. Cranston sat as if he meant to spend the night.

“I don’t get too many chances to talk to a white man,” he finally said with a kind of gruff diffidence. “Yon pretty fellows sleeping on the steamboat, they are not men, but clothespins. Sir Bryson Trangmar, Lord love ye! he will be calling me ‘my good man’ to-morrow. And him a grocer once, they say—like myself.” There was a cavernous chuckle here.

Jack sensed that the grim old trader was actually making friendly advances, but the young man was too sore, too hopelessly in the wrong, to respond right away.

Cranston continued to smoke and to gaze at the fire.

“Well, I have something to say,” he blurted out at last, in a changed voice. “And it’s none too easy!” There was something inexpressibly moving in the tremor that shook his grim voice as he blundered on. “You made a mistake, young fellow. She’s too good for this ‘whistle and I’ll come to ye, my lad,’ business. If you had any sense you would have seen it for yourself—my little girl with her wise ways! But no offence. You are young. I wouldn’t bother wi’ ye at all, but I feel that I am responsible. It was I who gave them a dark-skinned mother. I handicapped my girl and my boys, and now I have to be their father and their mother too.”

A good deal less than this would have reached Jack’s sense of generosity. He hid his face again, and hated himself, but pride still maintained the ascendency. He could not let the other man see.

“It is that that makes you hold her so lightly,” Cranston went on. “If she had a white mother, my girl, aye, wi’ half her beauty and her goodness, would have put the fear of God into ye. Well, the consequences of my mistake shall not be visited on her head if I can prevent it. What does an idle lad like you know of the worth of women? You measure them by their beauty, which is nothing. She has a mind like an opening flower. She is my companion. All these years I have been silenced and dumb, and now I have one to talk to that understands what a white man feels!

“She is a white woman. Some of the best blood of Scotland runs in her veins. She’s a Cranston. Match her wi’ his lordship’s daughter there, the daughter of the grocer. Match her wi’ the whitest lilies of them all, and my girl will outshine them in beauty, aye, and outwear them in courage and steadfastness! And she’s worthy to bear sons and daughters in turn that any man might be proud to father!”

He came to a full stop. Jack sat up, scowling fiercely, and looking five years younger by reason of his sheepishness. What he had to say came out in jerks. “It’s damn hard to get it out,” he stuttered. “I’m sorry. I’m ashamed of myself. What else can I say? I swear to you I’ll never lay a finger of disrespect on her. For heaven’s sake go, and let me be by myself!”

Cranston promptly rose. “Spoken like a man, my lad,” he said laconically. “I’ll say no more. Goodnight to ye.” He strode away.

Morning breaks, one awakes refreshed and quiescent, and, wondering a little at the heats and disturbances of the day before, makes a fresh start. Mary was not to be seen about the fort, and Jack presently learned that she and Davy had departed on horseback at daybreak for the Indian camp at Swan Lake. He was relieved, for, after what had happened, the thought of having to meet Mary and adjust himself to a new footing made him uncomfortable.

Jack’s self-love had received a serious blow, and he secretly longed for something to rehabilitate himself in his own eyes. At the same time he was not moved by any animosity toward Cranston, the instrument of his downfall; on the contrary, though he could not have explained it, he felt decidedly drawn toward the grim trader, and after a while he sheepishly entered the store in search of him. He found Cranston quite as diffident as himself, quite as anxious to let bygones be bygones. There was genuine warmth in his handclasp.

They made common cause in deriding the gubernatorial party.

“Lord love ye!” said Cranston. “Never was an outfit like to that! Card-tables, mind ye, and folding chairs, and hanging lamps, and a son-of-a-gun of a big oil-stove that burns blue blazes! Fancy accommodating that to a horse’s back! I’ve sent out to round up all the company horses. They’ll need half a regiment to carry that stuff.”

“What’s the governor’s game up here?” asked Jack.

“You’ve got me,” said Cranston. “Coal lands in the canyon, he says.”

“That’s pretty thin,” said Jack. “It doesn’t need a blooming governor and his train to look at a bit of coal. There’s plenty of coal nearer home.”

“There’s a piece about it in one of the papers the steamboat brought,” said Cranston.

He found the place, and exhibited it to Jack, who read a fulsome account of how his honour Sir Bryson Trangmar had decided to spend the summer vacation of the legislature in touring the North of the province, with a view of looking into its natural resources; that the journey had been hastily determined upon, and was to be of a strictly non-official character, hence there were to be no ceremonies en route beyond the civilities extended to any private traveller; that this was only one more example of the democratic tendencies of our popular governor, etc.

“Natural resources,” quoted Jack. “That’s the ring in the cake!”

“You think the coal they’re after has a yellow shine?” suggested Cranston.

Jack nodded. “Even a governor may catch that fever,” he said. “By Gad!” he cried suddenly, “do you remember those two claim-salters—Beckford and Rowe their names were—who went out after the ice last May?”

“They stopped here,” said Cranston. “I remember them.”

“What if those two—” suggested Jack.

“Good Lord!” cried Cranston, “the governor himself!”

“If it’s true,” cried Jack, “it’s the richest thing that ever happened! A hundred years from now they’ll still be telling the story around the fires and splitting their sides over it. It’s like Beckford, too; he was a humourist in his way. This is too good to miss. I believe I’ll go back with them.”

From discussing Sir Bryson’s object they passed to Jack’s own work in the Spirit River Pass. No better evidence of the progress these two had made in friendship could be had than Jack’s willingness to tell Cranston of his “strike,” the secret that a man guards closer than his crimes.

“I don’t mind telling you that I have three good claims staked out,” said Jack. “In case I should be stopped from filing them, I’ll leave you a full description before I go. I’ll leave you my little bag of dust too, to keep for me.”

“You’re serious about going back with them, then?” said Cranston.

Jack nodded. “I ought to go, anyway, to make sure they don’t blanket anything of mine.”

In due course Jack produced his little canvas bag, which the trader sealed, weighed, and receipted for.

“There’s another thing I wanted to talk to you about,” said Jack diffidently. “I can’t hold these three claims myself. I want you to take one.”

“Me?” exclaimed Cranston in great astonishment.

“Yes,” stammered Jack, still more embarrassed. “For —for her, you know—Mary. I feel that I owe it to her. I want her to have it, anyway. She needn’t know it came from me. It’s a good claim.”

Cranston would not hear of it, and they argued hotly.

“You’re standing in your own daughter’s light,” said Jack at last. “I’m not giving you anything. It’s for her. You haven’t any right to deprive her of a good thing.”

Cranston was silenced by this line; they finally shook hands on it, and turned with mutual relief to less embarrassing subjects. Jack had the comfortable sensation that in a measure he had squared himself with himself.

“Who’s running the governor’s camp?” asked Jack.

“They brought up Jean Paul Ascota from the Crossing.”

“So!” said Jack, considerably interested. “The conjuror and medicine man, eh? I hear great tales of him from all the tribes. What is he?”

Cranston exhibited no love for the man under discussion. “His father and mother were half-breed Crees,” he said. “He has a little place at the Crossing where he lives alone—he never married— but most of the time he is tripping; long hikes from Abittibi to the Skeena, and from the edge of the farming country clear to Herschel Island in the Arctic, generally alone. Too much business, and too mysterious for an Indian, I say. He’s a strong man in his way, he has a certain power, you wouldn’t overlook him in a crowd; but I doubt if he’s up to any good. He’s one of those natives that plays double, you know them, a white man wi’ white men, and a red wi’ the reds. Much too smooth and plausible for my taste. Lately he has got religion, and he goes around wi’ a Bible in his pocket, which is plumb ridiculous, knowing what you and I know about his conjuring practices among the tribes.”

“I’ve heard he’s a good tripper,” said Jack.

“Oh, none better,” said Cranston. “I’ll say that for him; there’s no man knows the whole country like he does, or a better hand in a canoe, or with horses, or around the camp. But, look you, after all he’s only an Indian. Here he’s been with these people a week, and already his head is turned. They don’t know what they’re doing, so they defer to him in everything, and consequently the Indian’s head is that swelled wi’ giving orders to white men his feet can hardly keep the ground. Their camp is at a standstill.”

“Hm!” said Jack; “it’s a childish outfit, isn’t it? It would be a kind of charity to take them in hand.”

A little later Jack ran into the redoubtable Jean Paul Ascota himself, whom he immediately recognized from Cranston’s description. As the trader had intimated, there was something strongly individual and peculiar in the aspect of the half-breed. He was a handsome man of forty-odd years, not above the average in height, but very broad and strong, and with regular, aquiline features. Though Cranston had said he was half-bred, there was no sign of the admixture of any white blood in his coppery skin, his straight black hair, and his savage, inscrutable eyes. He was dressed in a neatly fitting suit of black, and he wore “outside” shoes instead of the invariable moccasins. This ministerial habit was relieved by a fine blue shirt with a rolling collar and a red tie, and the whole was completed by the usual expensive felt hat with flaring, stiff brim. A Testament peeped out of one side-pocket.

But it was the strange look of his eyes that set the man apart, a still, rapt look, a shine as from close-hidden fires. They were savage, ecstatic, contemptuous eyes. When he looked at you, you had the feeling that there was a veil dropped between you, invisible to you, but engrossed with cabalistic symbols that he was studying while he appeared to be looking at you. In all this there was a certain amount of affectation. You could not deny the man’s force, but there was something childish too in the egregious vanity which was perfectly evident.

He was sitting on a box in the midst of the camp disarray, smoking calmly, the only idle figure in sight. Tents, poles, and miscellaneous camp impedimenta were strewn on one side of the trail; on the other the deck-hands were piling the stores of the party. Sidney Vassall, with his inventory, assisted by Baldwin Ferrie, both in a state approaching distraction, were pawing over the boxes and bundles, searching for innumerable lost articles, that were lost again as soon as they were found.

Vassall was not a particularly sympathetic figure to Jack, but the sight of the white men stewing while the Indian loafed was too much for his Anglo-Saxon sense of the fitness of things. His choler promptly rose, and, drawing Vassall aside, he said:

“Look here, why do you let that beggar impose on you like this? You’ll never be able to manage him if you knuckle down now.”

Vassall was a typical A. D. C. from the provinces, much better fitted to a waxed floor than the field. The hero of a hundred drawing-rooms made rather a pathetic figure in his shapeless, many-pocketed “sporting” suit. His much-admired manner of indiscriminate, enthusiastic amiability seemed to have lost its potency up here.

“What can I do?” he said helplessly. “He says he can’t work himself, or he won’t be able to boss the Indians that are coming.”

“Rubbish!” said Jack. “Everybody has to work on the trail. I’ll put him to work for you. Show me how the tents go.”

Vassall gratefully explained the arrangement. There was a square tent in the centre, with three smaller A-tents opening off. Jack measured the ground and drove the stakes. Then spreading the canvas on the ground, preparatory to raising it, he called cheerfully: “Lend a hand here, Jean Paul. You hold up the poles while I pull the ropes.”

The half-breed looked at him with cool, slow insolence, and dropping his eyes to his pipe, pressed the tobacco in the bowl with a delicate finger. He caught his hands around his knee, and leaned back with the expression of one enjoying a recondite joke.

Jack’s face reddened. Promptly dropping the canvas, he strode toward the half-breed, his hands clenching as he went.

“Look here, you damned redskin!” he said, not too loud. “If you can’t hear a civil request, I’ve a fist to back it up, understand? You get to work, quick, or I’ll knock your head off!”

The native deck hands stopped dead to see what would happen. Out of the blue sky the thunderbolt of a crisis had fallen. Jean Paul, the object of their unbounded fear and respect, they invested with supernatural powers, and they looked to see the white man annihilated.

The breed slowly raised his eyes again, but this time they could not quite meet the blazing blue ones. There was a pregnant pause. Finally Jean Paul got up with a shrug of bravado, and followed Jack back to the tents. He was beaten without a blow on either side. A breath of astonishment escaped the other natives. Jean Paul heard it, and the iron entered his soul. The glance he bent on Jack’s back glittered with the cold malignancy of a poisonous snake. It was all over in a few seconds and the course of the events for weeks to come was decided, a course involving, at the last, madness, murder, and suicide.

On the face of it the work proceeded smartly, and by lunch time the tents were raised, the furniture and the baggage stowed within, and Vassall’s vexatious inventory checked complete. His effusive gratitude made Jack uncomfortable. Jack cut him short, and nonchalantly returned to his own camp, where he cooked his dinner and ate it alone.

Afterward, cleaning his gun by the fire, he reviewed the crowded events of the past twenty-four hours in the ever-delightful, off-hand, cocksure fashion of youth that the oldsters envy, while they smile at it. His glancing thoughts ran something like this:

“To be put to sleep like that! Damn! But I couldn’t see what I was doing. If it hadn’t been dark! ... At any rate, nobody knows. It’s good he didn’t black my eye. Cranston’ll never tell. He’s a square old head all right. I suppose it was coming to me. Damn! ... I like Cranston, though. He’s making up to me now. He’d like me to marry the girl. She’d take me quick enough. Nice little thing, too. Fine eyes! But marriage! Not on your cartridge-belt! Not for Jack Chanty! The world is too full of sport. I haven’t nearly had my fill!... The governor’s daughter! Rather a little strawberry, too. Professional angler. I know ’em. Got a whole bookful of fancy flies for men. Casts them prettily one after another till you rise, then plop! into her basket with the other dead fish. You’ll never get me on your hook, little sister.... I can play a little myself. If you let on you don’t care, with that kind, it drives ’em wild.... Shouldn’t wonder if she had old Frank going.... Rum start, meeting him up here. What a scared look he gave me. I wonder!... He’s changed.... Very likely it’s politics, and graft, and getting on in the world. Doesn’t want to associate too closely with a tough like me, now.... Oh, very well! These big-bugs can’t put me out of face. I can show them a thing or two.... I put that Indian down in good shape. I have the trick of it. He’s a queer one. They’ll have trouble with him later. Women with them, too. Hell of an outfit to come up here, anyway.”...

Jack’s meditations were interrupted by Frank Garrod, who came threading his way through the poplar saplings. Jack sprang up with a gladness only a little less hearty than upon their first meeting the night before.

“Hello, old fel’!” he cried. “Glad you looked me up! We can talk off here by ourselves.”

But it appeared that Frank had come only for the purpose of carrying Jack back with him. Sir Bryson had expressed a wish to thank him for his assistance that morning. Jack frowned, and promptly declined the honour, but upon second thought he changed his mind. There was a plan growing in his head which necessitated a talk with Sir Bryson.

They made their way back together, Frank making an unhappy attempt to appear at his ease. He had something on his mind. He started to speak, faltered, and fell silent. But it troubled him still. Finally it came out.

“I say,” he said in his jerky way, “as long as you want to keep your real name quiet, we had better not let on that we are old friends, eh?”

Jack looked at him quickly, all his enthusiasm of friendliness dying down.

“We can seem to become good friends by degrees,” Garrod went on lamely. “It need only be a matter of a few days.”

“Just as you like,” said Jack coolly.

“But it’s you I’m thinking of.”

“You needn’t,” said Jack. “I don’t care what people call me. You needn’t be afraid that I’ll trouble you with my society.”

“You don’t understand,” Garrod murmured miserably.

However, in merely bringing the matter up he had accomplished his purpose, for Jack never acted quite the same to him afterward.

A little to one side of the tents they came upon a group of finished worldliness such as had never before been seen about Fort Cheever. From afar, the younger Cranston boys stared at it awestruck. Miss Trangmar and her companion sat in two of the folding chairs, basking in the sun, while Vassall and Baldwin Ferrie reclined on the grass at their feet, the former, his day’s work behind him, now clad in impeccable flannels. The centre of the picture was naturally the little beauty, looking in her purple summer dress as desirable, as fragile, and as expensive as an orchid. At the sight of her Jack’s nostrils expanded a little in spite of himself. Lovely ladies who metamorphosed themselves every day, not to speak of several times a day, were novel to him.

As the two men made to enter the main tent she called in her sweet, high voice: “Present our benefactor, Mr. Garrod.”

Garrod brought Jack to her. Garrod was very much confused. “I —I”—he stammered, looking imploringly at Jack.

“They call me Jack Chanty,” Jack said quietly, with his air of “take it or leave it.”

“Miss Trangmar, Mrs. Worsley,” Garrod murmured looking relieved.

Jack bowed stiffly.

“We are tremendously obliged,” the little lady said, making her eyes big with gratitude. “Captain Vassall says he would never have got through without you.”

A murmur of assent went round the circle. Jack would not out of sheer obstinacy make the polite and obvious reply. He looked at the elder lady. He liked her looks. She reminded him of an outspoken cousin of his boyhood. She was plain of feature and humorous-looking, very well dressed, and with an air of high tolerance for human failings.

“In pleasing Miss Trangmar you put us all under heavy obligations,” said Baldwin Ferrie with a simper. He was a well-meaning little man.

“By Jove! yes,” added Vassall; “when she’s overcast we’re all in shadow.”

Everybody laughed agreeably.

“Mercy!” exclaimed Linda Trangmar, “one would think I had a fearful temper, and kept you all in fear of your lives!”

There was a chorus of disclaimers. Jack felt slightly nauseated. He looked away. The girl stole a wistful glance at his scornful profile, the plume of fair hair, the cold blue eyes, the resolute mouth. All of a sudden she had become conscious of the fulsome atmosphere, too. She wondered what secrets the proud youthful mask concealed. She wondered if there was a woman for whom the mask was dropped, and if she were prettier than herself.

Meanwhile Jack felt as if he were acting like a booby, standing there. He was impelled to say something, anything, to show them he was not overcome by their assured worldliness. He addressed himself to Vassall.

“You have had no trouble with the Indian, since?”

“None whatever,” Vassall said. “He’s gone off now with some of the people here.”

Garrod took advantage of the next lull to say: “Sir Bryson is waiting for us.”

Jack bowed again, and made a good retreat.

“I told you he was a gentleman,” said Linda to Mrs. Worsley.

That lady had been impressed with the same fact, but she said cautiously, as became a chaperon: “His manner is rather brusque.”

“But he has manner,” remarked Linda slyly.

“We know nothing about him, my dear.”

“That’s just it,” said Linda. “Fancy meeting a real mystery in these matter-of-fact days. I shall find out his right name.”

“They say it’s not polite to ask questions about a man’s past in this country,” suggested Vassall with a playful air.

“Nor safe,” put in Mrs. Worsley.

“Who cares for safety?” cried Linda. “I came North for adventures, and I mean to have them! Isn’t he handsome?” she added wickedly.

The two men assented without enthusiasm.

Within the main tent Sir Bryson was seated at a table, looking the very pink of official propriety. There were several piles of legal documents and miscellaneous papers before him, with which he appeared to be busily occupied. It was noticeable that his chief concern was to have the piles arranged with mathematical precision. He never finished shaking and patting them straight. At first he ignored Jack. Handing some papers to Garrod, he said:

“These are now ready to be sent, Mr. Garrod. Please bear in mind my various instructions concerning them.”

Garrod retired to another table. He proceeded to fold and enclose the various documents, but from the tense poise of his head it was clear that he followed all that was said.

Sir Bryson now affected to become aware of Jack’s presence with a little start. He looked him up and down as one might regard, a fine horse he was called on to admire. “So this is the young man who was of so much assistance to us this morning?” he said with a smile of heavy benignity.”

Jack suppressed an inclination to laugh in his face.

“We are very much obliged to you, young sir—very,” said Sir Bryson grandly.