RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

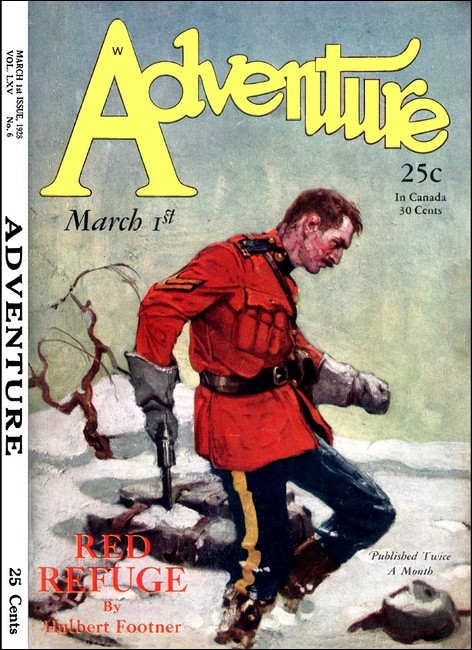

Adventure, 1 March 1928, with first part of "Red Refuge"

CONSTABLE DAN McNAB, R.N.W.M.P., in the bow of the dugout canoe, was not glorying in his career at the moment. He and Sergeant Brink-low, circling Great Swan Lake on the first patrol of the season, were bucking a head wind and a big sea that came sloshing over the bows every few seconds. The long, slender dugout was not designed for heavy weather; but the big Peterboro' in which they usually made the journey had been requisitioned for an emergency patrol up to Opawaha Lake where the Indians had measles.

McNab's slicker kept the upper part of his body dry, but he was kneeling in three inches of icy water, and it filled his boots. Moreover, the slicker hampered the free use of the paddle and chafed him under his arms. In short, his discomfort was perfect.

He resented the privileges of rank which permitted his sergeant to sit high and dry in the stern, unhindered by any slicker. Brinklow was whistling cheerfully and unmelodiously between his teeth. The younger man darkly suspected that he was letting him do the lion's share of the work. The wind was like a giant hand pressing them back. McNab gloomily calculated that they were making about a mile an hour against it. They had been fighting it for all of two hours, yet their starting place was still in sight behind them. He was sore against the whole world, and particularly against the man behind him, who was making him work like a galley slave.

Yet Brinklow presently spoke up in his rich, slow voice:

"We'll go ashore at Cut Across Point yonder and let this blow itself out. There's an abandoned shack there where we can build a fire. We'll bake bread, and you can dry out your hindquarters, lad."

A swift, warm reaction took place in McNab. Good old Brinklow! What a decent head he was! Always thinking of his men!

Thereafter the young man kept his eyes fixed full of anticipation on the low spruce clad point that ran out ahead. It got its name from the fact that here you cut straight across the lake for the intake of the river. The sky was gray and the face of the lake gray, daubed with white; the tall spruces along shore looked almost black in their winter suits. It was late May and there was a sense of spring in the air; the grass bordering the distant shallow inlets was madly green; but all along the main shores at the foot of the spruces great cakes of ice were still fantastically piled where they had been shoved up when the fall of the lake moved. This made landing difficult; however Brinklow knew that a little stream came in on the other side of the point and would have melted the ice there.

Great Swan lake was a hundred miles long and shaped something like a pair of saddle bags pinched in the middle. Apart from the little settlement at the head, which included police headquarters for the district, nobody lived upon it except a few miserable villages of fish eaters who shifted up and down the shores. This patrol was maintained for the benefit of the new settlers who would try to come this way at the wrong season. In the winter there was a good road over the ice and in the summer they could come by boat without too much difficulty, but with the wrongheadedness of tenderfeet they insisted on driving in in the summer, and there was no road around the lake. It was barely possible to drive around the beach, but not for tenderfeet; the services of the police were continually required to get them out of trouble.

The policemen rounded the point at last and ran into the mouth of a little stream between walls of ice. The tall, thickly springing spruce trees hid all sign of the shack of which Brinklow had spoken. Alongside the stream rose a clump of canoe birches, and the sergeant immediately pointed out to his young companion where several patches of bark had lately been cut from their trunks.

"The fish eaters mended canoes here yesterday," he said.

There was a regular landing place in a pool inside the line of ice, and from it a well beaten trail led away through the spruce trees. As soon as he disembarked Brinklow's keen eyes became busy upon it.

"Humph!" he grunted. "There's been a reg'lar crowd here. Both moccasins and hobnails."

It was about a hundred and fifty yards to the little clearing where the log shack stood with its attendant stable. These buildings had been put up by a new settler who designed to open a stopping house for freighters in the winter, but the enterprise had not prospered. As soon as the trees opened up, McNab, who was in advance, saw a wagon.

"There are white men here now," he said in surprise.

"No smoke in the chimney," said Brinklow.

They had to pass the stable first and looked in the door. No horses there, but a settler's outfit stowed neatly in one corner; boxes, bags, trunks, farming implements and so forth.

"Another greenhorn," said Brinklow dryly. "Mark the iron cookstove and the boxes of canned vegetables, ninety per cent, water. They will do it!"

There was no one about as far as they could see. Absolute silence brooded on the little clearing, save for the wind in the tops of the spruce trees. Passing around the stable, Brinklow called McNab's attention to a smashed window in the end of the house.

"A hell of a smash," he said succinctly. "See how the sash is splintered. From the inside."

A strong disquiet seized upon the younger man.

Drawing near to the door of the shack, Brinklow stopped; his eyes searched the ground all about and he scowled. It had rained heavily on the day before and the earth was soft. McNab saw everywhere the tracks of dogs, as he thought.

"Coyotes," said Brinklow; "nosing right up to the door. I never knew them to do that before. I don't like it!"

He laid his hand on the old fashioned latch and pushing the door in a few inches, raised his head and sniffed like an old hound.

"There is something wrong here!" he said gravely. "Stand back, lad."

McNab felt as if an icy hand had been Laid on his breast.

Brinklow kicked the door all the way open and looked over the threshold. He caught his breath and made a step backward.

"Oh, my God!" he ejaculated, instinctively thrusting backward with his hand to keep the young man away.

But McNab evaded the hand and looked over Brinklow's shoulder. Lying on his back on the floor of the shack with his feet pointing toward them was a dead man. His eyes were staring open and his jaw fallen down. In his forehead there was a round hole, and a great pool of blood had spread over the floor under his head. A burly man in his forties, with a thick dark beard. Even in death his vigor was impressive.

"Oh, my God!" echoed McNab.

There was no furniture in the shack except a rough homemade table and a pair of chairs. One of the chairs lay smashed on the floor under the broken window. At the other end of the room bedding for several men had been spread on piles of hay brought from the nearby stable. Four men had slept there. Various rough garments hung from nails driven into the log walls. A few soiled cooking utensils stood about on the hearth; the ashes were cold.

McNab was young enough and new enough to the force to feel nauseated and helpless. It was his first experience of death by violence. "What shall we do?" he murmured nervously.

But to Brinklow, the old sleuth, the sight acted as a spur. He instantly recovered from his start of horror; his eyes glistened with a kind of zest.

"Do!" he cried in a strong voice. "I'll tell you what you've got to do, my lad. Sit ye down on that bench outside the door, and stay there till I give ye leave to move. I don't want anybody else messing up these tracks until I can study them. If anybody heaves in sight, grab hold of him, that's all."

McNAB sat down at the door of the shack as he was bidden and lit his pipe to steady himself. Brinklow disappeared within, where he could be heard stirring about with quick, assured movements. Bye and bye he came out and without speaking to the other commenced to search the tracks around the house, all his senses on the alert; always heedful where he placed his own feet so as not to blot out anything. Frequently he squatted on his heels to sue better. McNab, watching him, thought:

"Brink is a natural born detective. He's been wasted up here where all his cases are simple and obvious. Maybe this will give him his big chance. Outside, he would have been famous long ago."

Sometimes Brinklow's investigations carried him out of the clearing, now to the left, now to the right. So quiet was he that the moment he was out of sight McNab lost him. A perfect stillness brooded over the scene; the sun, partly breaking through the clouds, cast a watery shine on the clearing. Green was springing up everywhere. In spite of the chill there was a feeling of life and growth in the air, hard to reconcile with the thought of the dead clay in the cabin.

In perhaps an hour, during the latter part of which he had been hidden from McNab's sight, Brinklow reappeared and, dropping on the bench beside the young man, allowed himself to relax. He carried a fine, new automatic pistol which he put down between them. McNab surveyed it with an uneasy respect. Drops of water clung to it. So this ugly bit of machinery had been the means of setting a soul free of its earthly tenement! Brinklow lit his pipe and studied for a while, chewing on the stem. Finally he began to speak.

"This is how the matter stands so far as I can dope it out. This poor stiff in here was one of a party of four incoming settlers. There are no papers on his body nor among his dunnage to tell me what his name was, nor the names of his companions, but as I take it, that ain't essential. The murder was provoked and accomplished right here, and it won't be necessary to dig far into his past. He and his mates were comin' in with a loaded wagon and team, and six spare horses. Town bred beasts with shoes on. Up to this point they had fairly easy goin', but here they were held up by the ice along the beach. Been here a week.

"He was shot while he was running down the path towards the landing place. We walked over the spot on the way up. He was shot in the back of the head. That hole you saw in his forehead was the point of egress of the bullet. The gun must have been close to his head, but not directly against it, because his hair is not singed. The first shot must have laid him out cold, but the murderer continued to shoot, and a curious thing is that, although the man must have been lying directly at his feet he didn't hit him again. I found three other bullets imbedded in the ground. Either the murderer was crazy with passion or totally unaccustomed to handling a pistol—or maybe both.

"He then threw the gun away. I found it about five yards off. It was lying in a puddle of rain water, which is unfortunate because the water would wash out the finger prints, always supposin' that I was smart enough to decipher them. I wish to God I had a magnifier. It is the latest type automatic, the first that was ever brought into this country .38 caliber. It has been kept carefully cleaned and oiled. This don't jibe with the clumsy way it was used, so I have it in mind that maybe the murder was done by some one other than the owner of the gun. The holster from which the gun was drawn is hanging up on the wail of the shack, just inside the door.

"Immediately after the murder the body was dragged to the shack and dropped where you see it now. He lost most of his blood inside here as you can see. Whether it was the murderer who brought him in I can't say. At any rate he was in a hell of a hurry, for most any man would have done the dead the decency of coverin' him up. The body is stiff, yet the blood is not all congealed, so that fixes the moment of the deed at about twelve hours back. Say ten o'clock last night. At that hour it is dusky but not totally dark."

"Sergeant, you're a wonder!" said the younger man admiringly. Brinklow waved it aside. "Well, that is what happened accordin' to what my eyes tell me," he went on. "As to what led up to it, I am all at sea. The smashed window suggests there was a hell of a time here previous to the shootin'. Why anybody should want to smash the window for, I can't figger. Tain't big enough to let a man out of. There's a greasy deck of cards on the table from which you might suppose there was a quarrel over the game. But that won't hold, because the dead man has got over live hundred dollars cash in his pocket. If they were so keen about money they wouldn't go away without that. Five hundred in cash, and a draft on the company for a thousand, made out to bearer. Even though, robbery had no part in the motive I can't understand how they went away without taking that.

"Neither does a gamblin' quarrel or robbery as a motive account for the Indians bein' here. Where they come in, I can't tell you. The tracks of moccasins are everywhere. Four or five different individuals. God knows these fish eaters are pretty near the lowest of mankind, but they haven't got nerve enough to hunt game. That's why they're fish eaters. I can't conceive of the fish eaters attackin' even one white man, let alone a party of four. And can you picture three able bodied white men running away from those miserable savages when one of their number was shot? It couldn't have been the fish eaters, because nothing around the place is touched.

"One set of moccasin tracks seems to favor the right foot. This suggests the man was lame. The only lame man that I can recall among the fish eaters is Sharley Watusk, who generally pitches at the mouth of Atimsepi across the lake. Has the name of bein' a bad egg, but cowardly as a coyote. If it was robbery, I could well believe it of him. But never the murder of a white man. Sharley has a daughter called Nanesis, a remarkable beauty. Once in a while you find them in the teepees.

"There's another relic of the visit of the fish eaters here. About fifty yards up the little stream from where we landed is a smashed birch bark canoe, a fish eater canoe. It was not broken by accident, but somebody had turned it over and stamped on it until it was completely smashed to pieces. Now what do you make of that? Some hellish passions have been let loose here!"

McNab could only shake his head. "Here's something else that bears on the killing," Brinklow went on, "but I can't as yet fit it into its place. There's a second little window in the westerly wall of this shack. It is not smashed. Outside it the ground is soft from the rain and bears the imprint of two knees there. Somebody knelt there last night, peeping over the sill into the shack. It wasn't the murdered man, because the knees are smaller than his. First off I reckoned they couldn't see much inside at that time of night, because I couldn't find that they had any way of lighting the shack except from the fire. Yet at that they couldn't have played cards on the table by firelight. Afterward I found a candle in the fireplace. Fire must have been near out when it was thrown there, because it had rolled to one side and only melted a little. Now candles are worth something up here. I wish somebody would tell me why they threw a good candle on the fire."

Another shake of the head from McNab.

"The first thing I've got to do is to find where the other three white men have gone to," resumed Brinklow. "One might almost suppose that the fish eaters had carried them off in their canoes, but that idea seems a little fantastic. They turned out their horses in a little natural meadow of blue grass alongside the stream a hundred yards or so back from the lake shore. Four of the horses are still grazing there. Sorry plugs. This suggests that 'the men took the other four and rode off somewhere, but I haven't tracked them yet. They did not ride back east the way they come, nor can I find any horse tracks to the west of us. They went in an awful hurry without fetching their saddles from the stable or taking any grub. Whatever it was drove them away, they're bound to return. In this country a man can not abandon his grub. Soon's I finish my pipe I'll take another look."

However, Sergeant Brinklow's pipe was not destined to be finished. As he sat chewing the stem and studying, the two of them were electrified by the sound of a distant shot from the southward.

"Ha! Still at it!" he cried, leaping to his feet. "Now I know where they've gone! Rode up the bed of the stream! Come on, lad! Bring your carbine!"

THE horses in the little meadow were hobbled and for further convenience in catching them each wore a rope bridle with a short length hanging from it. The policeman threw off the hobbles from two horses and clambered on their backs. The docile and broken spirited beasts answered willingly enough to the tugging of the rope, but, bred to the pavements, they were very unsure of foot and stumbled continually in the rough ground.

"We'd make as good time on our own legs," grumbled Brinklow.

Urging their mounts into the stream, they turned their heads against the current- The sergeant rode in advance. Where the stream ran through the meadow the water was almost breast high, but striking into another dense growth of pines and spruces it shallowed and ran brawlingly over small stones. Here the going was fairly easy, though they had occasionally to dismount and lead their horses around a tree which had fallen into the stream. McNab observed with surprise that Brinklow kept his attention upon the footing of his horse and never looked at the banks on either side.

"Mightn't they have turned off somewhere?" he suggested.

"Not here," said Brinklow. "You couldn't put a horse through virgin timber like that."

The stream ran as through a winding tunnel between the gigantic trunks. The curious monotony of the way made it seem longer than it was. At the bases of the trees a species of raspberry spread gigantic pale leaves in the dim light, a nightmare plant. The size and the endlessness of the trees oppressed the spirits; one felt that they reached to the confines of the earth. While they were still among them, the sound of another shot, somewhat muffled, reached their ears, followed by a hoarse yell and presently by two more shots. It had an uncanny effect there in the shadows and Dan McNab's heart contracted.

"Hope those shots didn't find human targets," said Brinklow gravely. "One murder is a plenty."

They got through the dark forest at last, issuing suddenly into a parklike country set out with clumps of willow and poplar. Sun and sky made a different world, and a fresh resolution inspired McNab, the recruit. He urged his dejected mount ahead. If there was evil and murder abroad in the world it was a man's job to ride it down.

Brinklow's keen little eyes were now searching the banks on either hand, and presently with an exclamation he put his horse to the right hand bank. McNab followed him. Even he could see where other horses had clambered up before them. Up on top they found themselves in rolling grass starred with crocuses. But though in general effect the country was as open as the sky, they could not see far ahead, because of the unevennesses of the ground and the frequent bluffs of trees. Brinklow, his eyes fixed on the tracks in the grass, rode in a bee line southwestward.

"Looks as if we were following somebody who knew the country," he said. "This is a natural route around the big timber and back to the lake at the narrows."

The ground must have been imperceptibly rising, for presently, looking back, they could see over the black sea of the forest to the blue waters of the lake.

Rounding a clump of black poplars, both horses shied violently. McNab lost his seat, but managed to cling to the rope fastened to his mount's head. That which had frightened them proved to be a wounded horse lying in the grass. One of his hind legs had been broken by a shot. There was no other living object visible in all the green landscape. The poor beast looked at them with soft, agonized eyes and Brinklow fingered the butt of his carbine. However, he slung it over his shoulder again.

"A shot would give warning of our coming," he said. "I mustn't do it." They rode on.

In another mile or so both horses pricked tip their ears and whickered softly. Brinklow pulled up and dismounted.

"We're near other horses," he said. "Lead your horse slowly ahead and hold his nose until we find out what we're up against."

A wide and seemingly impenetrable thicket of poplar saplings lay athwart their course; in the parlance of the country, a poplar bluff. The little trees, all of a uniform height of ten or twelve feet, seemed to grow as thickly as hair out of the prairie, their branches misted with a tender green. Drawing closer, they saw that the bluff, though wide, was not thick through; they could see to the other side. Presently they could make out the shadowy forms of two horses tethered within the shelter of the little trees and, coming closer yet, distinguished two men beyond the horses with their backs turned. The horses had perceived their fellows and were moving restlessly and pulling at their halters, but so intent were the men on what lay in front of them that they never looked around.

Seeing this, Brinklow turned off at a tangent, softly walking away through the grass until an inequality of the ground put both men and horses out of sight. He then led the way to the edge of the bluff, where they tied their horses and made their way back on foot.

They now came up on the two men from one side. The little trees, when one was under them, did not grow so thickly as appeared from a distance. A man could make his way through the bluff without difficulty. Brinklow, followed by McNab a few yards in the rear, approached to within half a dozen paces of the men and stopped, surveying them grimly. Both policemen had their carbines in their hands. The two men, likewise holding rifles ready, were crouched down peering out into the sunlight on the other side of the bluff. Occasionally they brought their heads together and whispered. Why they whispered, since as far as they knew there was no one within hearing but the horses, it would have been hard to say. Brinklow watched them for a moment or two, then said coolly— "Well, gentlemen?"

The two whirled around with a gasping breath. One lost his balance and toppled over backward, dropping his gun.

"Oh, Christ!" he gasped.

In spite of himself a start of laughter escaped from McNab. The man on the ground was red faced and red haired; the other black haired and pale; both heavy men, rough customers in their late thirties. The red faced man continued to gibber and mow out of sheer nervousness; the other turned wary and ugly.

Notwithstanding his shaken nerves the red haired man was the first to find his voice.

"Thank God! The police," he said, picking himself up. "That lets us out!"

But his voice rang false and his eyes bolted as he said it. He was not glad to see the police. The other man said nothing, but only scowled.

"What is going on here?" demanded Brinklow. "Who shot your partner last night?"

"The cook," they answered simultaneously. "We were tryin' to take him for you," the red haired man-added.

"Much obliged." said Brinklow dryly. "Where is he?"

"Yonder," answered the other, pointing. "Takin' cover behind the dead horse. Him and the girl with him."

"Oh, there's a girl in it!" said Brinklow. "I might have known as much. Who is she?"

"A redskin girl. I can't say her name rightly. Nan Somethin' or other."

"I know her," said Brinklow.

Looking out beyond the little trees, the two policemen saw a wide stretch of sunny green without any trees within a furlong's distance. In the center of the picture, a couple of hundred yards away, lay a dead horse in the grass. Over his ribs stuck the barrel of a rifle, and behind the rifle the top of a sleek black head.

"Hand over your guns to the constable." said Brinklow crisply, and when the two men reluctantly obeyed, "Now follow me, and we'll look into this."

Brinklow stepped out into the sun, raising his hand in token of amity. The two men followed him sullenly and McNab brought up the rear, carrying the three guns over his arm. The black head raised itself up and proved to belong to a woman. As they came closer she stood up and McNab's eyes widened in astonishment- An extraordinarily beautiful girl! Her companion was not visible until they reached the horse. A young man was then seen to be lying unconscious in the grass, one of his shirt sleeves soaked with blood.

"Well, Nanesis, what is this?" asked Brinklow in a gentler voice than ho had used heretofore.

The gun slipped out of her nerveless arms.

"Oh, Brinklow, I so ver' glad you come!" she faltered. "I so glad—"

She swayed and seemed about to fall, just like one of her white sisters. Brinklow flung an arm around her.

However, she did not swoon.

"I all right." she whispered. "Tak' care of him. He is shot."

She dropped down in the grass and hid her head between her arms while she struggled with her weakness. Brinklow knelt beside the wounded man. McNab out of the corners of his eyes surveyed the girl with growing amazement. A red girl they all called her, but he had never seen another like this. Her voice was as soft as a breeze in the spruce branches. Her skin was no darker than a brunette of his own race; it had the texture of creamy flower petals. Her big dark eyes were limpid with intelligence and feeling. Red or white, savage or civilized, she would have been a beauty among beauties anywhere.

From her he looked toward the young man with a spice of jealousy, her voice had been so warm with solicitude and tenderness. He saw a tawny headed lad of his own age, smaller and lighter than himself, but nevertheless well knit. Even in unconsciousness his face had a resolute, tight lipped look. A good head, was McNab's inward verdict. Knowing nothing of the circumstances of the case, his sympathies went out strongly to these two.

BRINKLOW cut away the sleeve of the young man's shirt. There was a bullet hole through the fleshy part of his arm.

"Never touched the bone," said the sergeant cheerfully. "He's just fainted from the loss of blood. We'll bring him round directly. What have you got for a bandage, Nanesis?"

His words acted like a tonic on the girl. She got up immediately and turning her back on them tore the hem off her petticoat.

"Don' let that touch the hurt," she said. "It's not 'nough clean. I get med'cine."

Searching in the herbage until she found a small plant with fleshy leaves, she rolled the leaves between her palms to crush them, and applied them to the wound as a plaster. While Brinklow held the arm up, she hound the place with her strip of colored cotton as neatly as a trained nurse.

"Either of you fellows got a drop of liquor?" asked Brinklow.

The two men, perceiving that the sympathies of the police had gone to the other side, had watched the scene with a growing sullenness. The black haired one answered with a sneer—

"Not for him, the murderer!"

A peculiar hard sparkle appeared in Brinklow's blues eyes. He stood up.

"You hand over what you got," he said with a dangerous mildness that was characteristic of him "and I'll decide who's to get it."

The man's angry black eyes quailed and without another word he handed over a flask with a little in the bottom of it.

Brinklow poured a few drops between the wounded man's lips and the effect was almost instantaneous. He opened a pair of startled gray eyes on them and, springing to a sitting position, looked around wildly for his gun.

"Easy! Easy, pardner!" said Brinklow, pressing him back.

From the other side the girl murmured:

"It's all right, Phil. The police 'ave come. We are safe!"

He fell back with a sigh of relief. She took his head in her lap. "Tak' ease," she softly whispered, stroking his hair. "All is well now."

Envy struck through McNab. "Gosh!" he thought, "if there was only a girl like that somewhere for me!"

The wounded man fell into what appeared to be a natural sleep. It would have been inhumane to attempt to move him at such a moment, and the whole party therefore sat down in the grass almost within arm's length of the dead horse. Young McNab was struck by the strangeness of the scene; a sort of magistrate's court sitting in the sunny prairie.

"Well, what are the rights of this matter?" asked Brinklow.

"There's your prisoner," said the red haired man violently. "He shot our partner."

The girl jerked up her brooding head and her soft eyes flashed. "He lyin'!" she said. "Phil not near the man w'en he shot."

"Aah! She's cracked about the kid," retorted the other bitterly. "You can see it for yourself. She'd say anything to save him!"

"One of them two, him or him," said the girl, pointing dramatically, "he kill!"

"She lies!" cried both the men together.

"Why should we kill our partner?" added the red haired one with a plausible air.

"I don't know," said Brinklow coolly. "What reason had they for killing their partner?" he asked the girl.

She hung her head and blushed like a white girl.

"I tell you," she said low. "All the men is wantin' me. So they play for me wit' the cards. An' him, the dead one, Black-beard, he win. So the ot'er men are sore."

A tense little drama was suggested by her words. McNab's youthful idealism was hurt by the disclosure. Had she permitted them to gamble for her? Was she then only a common thing of the country? Impossible, he thought, with such eyes. But her words propounded a dozen new questions for the one they answered. How had she fallen in with these men? How came this common Indian girl to have the looks and the feelings of a white lady?

"She ain't got that right," spoke up Red Head. "Our partner hadn't won her yet. He had only won the right to court her first, to have the first say. We meant fair by the girl," he added with a virtuous air. "Any one of us was willin' to marry her."

Brinklow looked from the rough and brutalized men to the flowerlike girl and said dryly—

"That certainly was square of you!"

His sarcasm was wasted.

"We hadn't no cause to croak our partner," put in the black haired one with his heavy air. "He hadn't won the girl."

"All right," said Brinklow. "Why should your young partner have done it then?"

"He wasn't no partner of ours," was Red Head's contemptuous answer. "He was just a grub rider, kind of. We let him cook for us for his keep. He hadn't no share in the outfit. He hadn't nothin' but the clo'es he stood in and his gun."

"Darn' good gun," remarked Brinklow, glancing at the weapon with the eye of a connoisseur. "A Harley express rifle."

"He; wasn't allowed no show with the girl and he was sore. That's why he croaked our pardner."

"It's a lie!" cried the girl. "W'at I care for the cards? I choose Phil. I tell him I choose him. What for he want kill Blackboard?"

"Liar yourself!" retorted the man. "Didn't you bust out of the shack, and call for Phil to come to you?"

"I call him to go way wit' me in my canoe," she said.

"Yeah," ho said contemptuously, "but he shot the man first."

"It's a lie! He is in front, and Black-beard shot be'in'!"

"Aah, tell that to the Marines!"

The listening policeman could make nothing of these confused particulars. Brinklow wagged his hand for silence.

"This is gettin' nowhere," he said. "One at a time! You," he commanded, singling out the red headed man, "you have a ready tongue. Tell your story from the start. What's your name and what brought you up here?"

There was an emotional, conceited streak in this bruiser, and he had a certain enjoyment in holding the center of the stage. He paused and took a chew of tobacco before beginning his story, and looked around to make sure he had the attention of all.

"Me, I'm Russ Carpy," he said with a swagger. "I been a prize fighter, and a darn good one. Not so long ago on'y three men stood between me and the light heavyweight champeenship. Sojer Carpy was my professional name. Guess you've heard it."

"Can't say as I have," said Brinklow dryly.

"Oh, well, you wouldn't, up in this neck of the woods. Havin' retired from the fightin' game, I aimed to take up land some'eres. I heard there was good free land in Northern Athabasca, so I headed this way. I met up with the other two fellows in the city of Hammonton at the end of the railway; Bill Downey here, and Shem Packer, that's the dead guy. Bill, he raised cattle down in Southern Athabasca, but the dry farmers run him out. Shem, I don't know what his line was before. He never told us. Shem, he had a wagon and eight horses he brought up from Vancouver, and me and Bill we each had a stake in money, so all chipped in together bein' as all had the same idea, which was to take up land along the line of some new railroad and sit down and raise cattle until it come through."

"Where was you aimin' to get the cattle to start with?" asked Brinklow dryly.

"Oh, from the Indians," said Carpy vaguely.

"Moose or Caribou?" asked Brinklow, with a private wink in McNab's direction.

Carpy stared-at him stupidly. "Go on," said the sergeant. Carpy nodded toward the wounded man.

"We picked up this kid bummin' around Hammonton half starved. Phil Shepley is the name he give. He was aimin' to go north so, as I tell you, we let him be our cook. We never had much truck with him, bein' as he was a sullen crab. Thought himself too good for his company."

Brinklow glanced at McNab again. Showed his good taste, his eyes said; but he did not speak it.

"This was in the winter," resumed the other. "We put our wagon body on runners and started in over the snow and ice. Got as far as the joinin' of the rivers two hundred miles from town, when the snow melted and the ice begun to soften Had to go into camp until the land road was fit for travel. Then we put the wheels to the wagon and come up alongside the little river to the lake, and so to the place where you found our outfit. We was stopped there by the ice on the beach. Lucky we found the empty cabin and stable. Been there a week yesterday. It was a tiresome time. Hadn't nothin' to amuse ourselves with but a greasy deck of cards."

Carpy paused and looked at the girl sullenly. For all of his conceited air, a look of awe came into his face.

"At dinnertime yesterday," he went on in a lowered voice, "this girl come to our shack. She come in a canoe, but we didn't know that then. She hid the canoe and it was like as if she dropped from the sky. E'ything about her was myster'ous. We couldn't make her out noways. She let on she couldn't speak English nor understand it, so we had to talk to her by signs ... I leave it to you if she ain't a deep one," he said with resentful bitterness, "takin' us in all the time, and never givin' nothin' away herself!"

Brinklow looked down his nose and made no comment. Young McNab leaned forward to hear better.

"We couldn't figger out what she come for at all," said Carpy, his resentful puzzled scowl on the girl. "Like a tigress if a man laid hands on her. Yet she seemed friendly, too. Cooked us up a darn sight better meal than our own cookee was good for, and showed herself real handy, sewin' and fixin' things up and all.

"Well, bein' as she was such a good looker and all," he went on, "ev'y one of us begun to think it would be nice to have her round for keeps. Though she come like an Indian and made out to be red, what with her white skin and the color in her cheeks we made sure she had white blood. A settler in a new country needs a good wife above all, to help him make a go of it, and she was like one sent a purpose. But only one, whereas we were three.

"So there begun to be trouble right away, ev'y man snarlin' at his pardners and ready to fight at the drop of the hat. The girl never let nothin' on, but just stayed around mendin' our clo'es as if for to advertise herself as a good wife. Tell me she wasn't a deep one! It got worse and worse all afternoon. The on'y thing that kep' us from fightin' was, if any fellow picked a quarrel he always had the other two lo fight. None of us could get the girl alone for a minute, because we had to watch each other.

"Towards supper time Shem proposed that we leave it to the cards. 'Boys,' he says, 'we can't go on this way. We all want this girl, and if we don't settle it somehow, we'll be blowin' the tops of each others heads off before mornin'. None of us wanted to stake his chance on the turn of a card, but there wasn't no way of escapin' from Shem's logic; we had to agree. So it was fixed as soon as supper was over we'd play for who should have the first chance to court the girl. The winner was to have the shack that evenin', and if he made good with her, all right. If he was turned down the second man was to have the shack and the second evenin'; and if he was unsuccessful, the third man followin' him."

As a result of hearing this curious tale young McNab was somewhat relieved in mind. It was evident from the speaker's reluctant tribute that the girl was neither light nor common. Still McNab could not understand how she had come to put herself in such a dangerous situation. He waited eagerly for the explanation.

"Meanwhile the girl and cookee was gettin' supper together," Carpy resumed with increased bitterness. "Must 'a' been somewheres about that time they come to an understandin' with each other. It didn't occur to none of us that she might take a shine to that measley little feller. Why, any of us would most have made two of him! We never seen them whisperin' together; we never suspected she had any English. Shows what a sneakin' onderhand pair they was, the two of them!" he burst out passionately.

"That's right!" put in Downey with a black look.

"Well, it's all in the point of view," remarked Brinklow.

"After we eat there was another wrangle how to settle it with the cards," Carpy resumed. "Some wanted to cut for it, and some to deal. In the end we did both. We cut for deal and Shem won it. It was agreed he was to deal out the cards face up and whoever got the ace of spades was eliminated. Both me and Bill shuffled the cards and then Shem dole them out. I had no luck; I got the ace of spades the first round. Bill got it on the second, leavin' Shem the winner. It made me sore."

Here it transpired that though Carpy and his partner were ready to combine against the young pair, they had their own differences. Downey broke in bitterly—

"Yeah! Why don't you tell the sergeant you was a bum sport and wouldn't stand by the decision of the cards?"

"Be quiet," said Brinklow. "You'll have your say directly."

"Well, it looked funny to me," grumbled Carpy, "bein' as Shem was the dealer and all. Cookee, he fired up. He said it was a shame and all, and he was thrown out of the shack. I don't know where he went. The girl took it all perfectly quiet. Then me and Bill left the shack aocordin' to agreement—."

"You mean you was thrown out too," put in Downey.

"Shut up!" said Brinklow.

"—and the two of us went down to the lake shore and built a fire there," Carpy continued; "but we was sore. And pretty soon Bill went away. I was suspicious what he would be up to, so I went back to the shack and looked around. It was pretty dark, but you could see a little. I seen Bill kneel in' on the ground, spyin' on 'em through the window—"

"It's a lie!" cried Downey. "I went to the shack, and I seen Sojer spyin' through the window. He's tryin' to put off on me what he was doin' hisself!"

"Never mind it now," said Brinklow. "Get on with the story."

"I went back to my fire," said Carpy. "I was good and sore. I doubted if Shem would play fair with the girl, and I was darn sure Bill wouldn't—"

Downey snarled at him.

"—so it looked as I didn't stand no chance at all. While I was by the lake I hear a crash of glass and breakin' wood, and right after that the door of the shack open, and I heard the girl callin', 'Phil! Phil! Phil!' Just as good as I could say it myself. That was a staggerer. Then I hear Shem cussin' her, and the sound of runnin' feet. I run myself. Seemed like they was makin' for the landin' place, and I followed. Before I got there I hear a shot and a fall on the ground, and four more shots fired as fast as you could pull the trigger. Then silence."

SOJER CARPY had lost his conceited air by now. His eyes were haunted by the recollection of that scene in the dark, and the ready tongue stumbled.

It was impossible for young McNab to judge how far the man might be telling the truth. As for Sergeant Brinklow, he looked down his nose and kept his own counsel.

"The sound of them shots scairt me," said Carpy, "and I come to a stop. Not another sound reached me. I went on slow, and pretty soon I all but stumbled over the body of Shem lyin' in the path. Bill Downey was standin' on the other side of him."

"You lie!" interrupted Downey. "When I got there you was already there."

"You lie!" snarled Carpy.

"Oh, get on! Get on!" said Brinklow with a bored air.

"I left him there," said Carpy. "I thrashed around through the timber lookin' for the girl. But it was useless in the dark. When I stopped to listen all I could hear was Bill bulling around just like me. Bime-by we met by the corpse again. God! I judged from his actions he was goin' to shoot me next."

"You raised your gun at me," snarled Downey.

"Well, anyhow, we seen we couldn't go on that way," said Carpy, "and so we made a deal to hunt for the girl together—"

"And kill the cook?" put in Brinklow softly.

Carpy ignored it.

"And when we found her then we could decide which was to have her—"

Young McNab looked at the girl in astonishment. What fearful passions her beauty had set loose in the dark! At the moment she seemed perfectly indifferent to what Carpy was saying. All her attention was given to the sleeping man whose head lay in her lap.

"By that time." Carpy went on, "we figured she must have come by canoe, though we hadn't seen the canoe. The on'y place you could land from the lake or push off was the mouth of the little river, so Bill went down there to watch while I dragged Shem's body to the shack to keep him from the coyotes. Ev'y night the coyotes come around camp after we went in. I dropped Shem in the shack and shut the door on him, and then I went back to the river and watched there with Bill, him on one side, and me on the other.

"Well, after a long time we heard 'em comin' real soft. About a hundred feet in from the lake there's a shallow place where the stream runs over stones, and that's where we was watchin'. They had to get out there and float their canoe down. Bill and me, we rushed 'em, and they left the canoe and run for it."

The girl spoke up unexpectedly—

"They fire' at us."

"It was Bill fired at them," said Carpy quickly.

"You lie! It was yourself!" cried Bill.

"We smashed the canoe good," Carpy went on unabashed, "so they couldn't escape any more by that means. And then as it was useless to look for them in the dark, we set down to wait for daylight. Before three it begins to get light again up her. Seems there's scarcely no night at all at this season. Soon as we could see a little, it occurred to us they would steal horses next, so we crep' up to the little prairie where we had our horses turned out. We wasn't quite soon enough. We saw them ride a couple of horses into the water and disappear upstream. They didn't see us.

"So we got two more horses and took after them. They rode slow up the stream, not knowin' we was behind, and it wasn't long before we came in sight of them. They saw us too, and they went behind a big fallen tree which made a natural barricade across the river. From behind it they held us off all mornin'. We'd 'a' been there yet, on'y we discovered they'd left a couple of sticks pointin' at us like guns and had ridden clear away behind the tree. So we took after them again. We seen where they left the stream, and took to the prairie. Bill was experienced in trackin' horses through the grass. We caught 'em in range as they rode around a clump of poplars—"

"Yeah, and who fired at them then?" sneered Bill Downey.

"I did," said Carpy defiantly. "And I had a good right to. Wasn't he tryin' to escape from justice?"

"So?" drawled Brinklow. "When did that notion first strike you?"

"Me and Bill talked it over good durin' the night, and we decided that cookee had shot our partner."

"I see," said the Sergeant dryly. "Go ahead."

"I brought down one of the horses. But cookee, who was ridin' it, he jump up behind the girl, and I was afraid to fire again for fear of hittin' her. They rode into cover amongst some trees. We caught 'cm fair as they loped across this open space, and both of us fired."

"I fired at the horse," said Downey.

"So you say," sneered his partner. "However that was, between us we killed the second horse and winged the man. When the horse fell they dropped behind it, and then they had us at a stall, for bein' in the open out here, we couldn't approach them without exposin' ourselves. We didn't want to shoot the girl, and the man was hidden from us. Well, that was how matters stood when you come. I cert'n'y was glad to see the red coats of the police!"

"I reckon you were," said Brinklow.

Carpy pulled out his pipe and started to fill it with an air of bravado. It was a bit overdone. His hand shook slightly. To Young McNab he had the look of a liar. Certainly his last sentence was transparent hypocrisy. Brinklow was studying him through narrowed eyes. Finally the Sergeant turned to Bill Downey with an inscrutable face.

"Well, what have you got to say?" he asked. "Do you corroborate his story? Have you got anything to add to it?"

This man, while no more prepossessing than his partner, was of an entirely different character; he was black and saturnine. Ordinarily a silent man, he clipped his sentences when forced to speak. He said in his slow way:

"It's true in the main. But colored to suit himself. You was right in givin' him a ready tongue. Too damn' ready. Nobody can't believe Sojer Carpy. I learned that long ago. Me and him made it up to stick together, and look how he was gettin' at me all through. Well, two can play at that."

"Aah, shut up, you fool!" snarled Carpy.

Brinklow silenced him.

"So you made it up to stick together," he said dryly to Downey. "Go ahead."

"What ho didn't tell," Downey went on, "was what a dirty part he played all through. It was him made all the trouble when the girl come yesterday. Fancied hisself as a ladies' man. Tried to shoot Shem and me, he did, on'y when he run to the corner where the guns was kept, they wasn't there."

"Where were they?"

"Sojer, he accused me of havin' hid 'em for my own purpose," said Downey. "He set Shem against me, and the two of them was beatin' me up when cookee says he hid the guns. Didn't want to be concerned in no wholesale murders, he said."

"What a happy little family!" murmured Brinklow.

"Cookee says they was shoved under the eaves of the stable if we was bent on blowing each others' heads off," said Downey. "But Shem stopped us gettin' them. It was then we made up to settle it with the cards. Sojer wouldn't stand by that neither. Me and Shem had to throw him out of the shack. He run and got his gun then. And I got mine just to watch him. We went down to the lake shore together. Sojer proposed that him and me bump off Shem together—"

Carpy broke out into furious denials. Brinklow silenced him.

"But I wouldn't," Downey went on coolly, "because I knew if I did Sojer would lay for me afterwards. He made me sick with his grousin' and cryin' and I went by myself. Bime-by I hear somethin' and I went back to the shack, and I seen Sojer kneelin' on the ground peepin' through the window."

"It was you!" cried Carpy.

"I ain't no peeper," said Downey. "It's a woman's trick."

"Will you go on the stand and lay your hand on the book and swear that you seen me kneelin' at the window?" demanded Carpy.

"Sure, I will," answered Downey with the utmost coolness. "And if anybody's got a Bible, I'll swear it now."

"It's a lie!" yelled Carpy hysterically. "And your soul will be damned to hell for sayin' it!"

"Well, leave it lay for the present," said Brinklow with a bored air. "Let him go on with his story."

"It disgusted me like, to see him peepin'," Downey went on, "and I went away from there. I was down by the water hole when I heard the glass busted."

"The water hole?" queried Brinklow.

"That's the landing place in the little river. We fetched our water from there. I heard the girl run out and call for the cookee. I heard Shem cussin' her. Then I heard the shots—five shots. I run up the path and I come on Shem's body lyin' there and Sojer kneelin' down beside it."

"You lie!" cried Carpy. "You was there before me!"

"After that," Downey went on unconcernedly, "ev'thing happened just like he said. On'y it was him fired at cookee and the girl when they was tryin' to escape in the canoe. If the fool hadn't fired his gun they would 'a' walked right into our arms in the dark, and we'd 'a' had 'em both. That's all I got to say."

Young McNab, having heard both stories, thought:

"It lies between these two all right. I believe Downey's side of it. He's just as big a scoundrel as the other, but he hasn't got enough imagination to lie."

Sergeant Brinklow betrayed no sign of what his opinion might be. He gave the situation a new twist by turning to the girl and unexpectedly asking—

"Nanesis, what were your father and his friends doing at Cut Across Point yesterday?"

"Sharley Watusk, him not my fat'er," she said quickly and proudly. "Him jus' my mot'er's osban'. My fat'er him white man. Name' Dick Folsom."

"Sure," said Brinklow. "I had forgotten. Well, what was your mother's husband doing at Cut Across Point?"

"I not know what 'e do there," she said with a contemptuous air. "Ask them."

Brinklow turned to Carpy.

"You had some other visitors at your camp yesterday," he said.

"A parcel of redskins," was the indifferent answer. "What they call fish eaters. They come before the girl."

"What did they come for?"

"Nothin' so far as we could make out. Just curiosity. When we got up in the mornin' they was already there. Jus' squattin' on their heels lookin' at us. Four little men. Couldn't get no sense out of 'em."

"But Sharley Watusk speaks good English," said Brinklow. "That was the lame man."

"I suspected as much," said Carpy. "But we couldn't get nothin' out of him but grunts and signs." He looked resentfully at the girl. "Seems to be the custom hereabouts to make out to be dumb. They begged for ev'ything they saw. Made out to be starvin', but we found they had plenty nice fish in their canoe. So we wouldn't give em nothin'. Got our goat bime-bye to see them squattin' on their heels, starin', starin', starin'! Never lettin' nothin' on. So we told them to get the hell out o' there. They jus' went off a little way and squat down again. Finally the three of us we got good and sore and booted them down to the stream and into their canoe. They paddles across the lake. That was about half an hour before the girl come."

Brinklow studied this, rubbing his chin. Finally he turned to the girl again.

"Nanesis, what were they after?" he asked.

"They lookin' for me," she answered in the contemptuous tone she always used toward her own people. "But I not show myself till they gone back. I done wit' fish eaters. I white girl now."

IN the haste of escape and pursuit nobody had brought any food. It was now past midday and all felt the pangs of hunger. The wounded man, awakening, said that he felt able to ride the three miles or so back to camp; so his arm was bound in a sling, he was helped on a horse, and the slow walk back began. Brink-low, McNab and Nanesis mounted the other three horses, while Bill and the Sojer were required to foot it. They grumbled loudly.

"Well, you shot the other two horses," said the Sergeant unsympathetically.

The two then set off ahead at a fast walk that would soon have carried them out of sight of the rest of the party. Brinklow, mindful of the dugout in the mouth of the stream which would have afforded them an excellent means of escape, ordered them to heel in no uncertain tone.

"Aah, what's the matter?" snarled Carpy. "Are we under arrest?"

"Don't say arrest," said Brinklow ironically. "Say detained as material witnesses."

Slow as their progress was, young Shepley, with his wound and his having no saddle, was hard put to it to keep his seat. He suffered much pain and was obviously incapable of telling a connected story. Brinklow tried to get the girl to talk, but such was her concern with Shepley's condition she could only give him half her attention.

"We'en I mak' him comfortable, I tell all," she said.

And Brinklow let her be. Passing the wounded horse, the sergeant ended his sufferings with a bullet.

In an hour they were back at the shack, where all was found as they had left it. Blankets were spread on a bed of hay out of doors for the wounded man, while Nanesis made haste to prepare a meal. McNab's job was to watch Sojer Carpy and Bill Downey. All ate in silence watching each other out of walled faces.

Afterward, leaving Nanesis to nurse her man, Brinklow and McNab took Sojer and Bill into the shack, where the Sergeant bade them to pick up the dead man and carry him outside, preparatory to burying him. He watched them keenly, hoping, as McNab supposed, that the guilty man might betray himself in the presence of his victim. But both Bill and the Sojer regarded the corpse with the greatest coolness. They were a callous pair. The latter said—

"Gee! a feller ain't pretty when he's dead."

"You won't look no better," retorted Bill.

"I didn't know a man held so much blood," said Sojer.

"Aah, Shem would 'a' died a apoplexy if he'd lived," said Bill in his stupid fashion.

"By the way," said Brinklow carelessly, "whose was the automatic in the leather holster hanging by the door?"

The two men looked at each other warily, then at Brinklow, evidently studying how to answer. Finally Sojer said—

"I don't rec'lect no holster hangin' by the door."

And Bill echoed him—

"Me neither. Where is it now?"

"I have it," said Brinklow. "That was the gun this man was shot with."

"No!" they both said, with such a transparent affectation of surprise, that Brinklow laughed in their faces.

"Do you mean to tell me," he said, "that you don't know the difference between the report of a pistol and a rifle?"

"Well, I suppose I do," said Sojer. "But I was so excited I never noticed."

"Same here," said Bill. "I was too excited."

Brinklow singled out the Sojer.

"Answer me, you. Are you tryin' to tell me you didn't know there was such a weapon in the outfit?"

Sojer hesitated in a painful indecision. Evidently he reflected that such a fact could not be hidden for he said sullenly: "Sure I knew we had it. But I ain't seen it lately."

"Whose was it?"

"Shem's."

"So! The man was shot with his own gun! Was there any other pistol in the outfit?"

"No. We knew it was against the law to carry pistols—short guns—up in this country, but Shem already had it and didn't want to sacrifice it. So he put it in the bottom of his dunnage bag when we come in."

"Well, why do you try to make a mystery of it," said Brinklow, "unless you used it last night."

"I swear to God I never had my hands on it!" cried Sojer in a panic. "I was outside! I was outside! How could I get it? Why, I wouldn't know how to shoot with a pistol anyway."

"Neither did the murderer," said Brinklow dryly.

Sojer stared at him in terror, then hastily corrected himself.

"Well, of course I have shot with a pistol. I was pretty good at it once. But I ain't tried it lately."

Brinklow turned away.

"Fetch the body outside," he said.

Billy Downey was not ill pleased at his partner's discomfiture.

A spot was chosen for the grave at the edge of the clearing behind the shack. Spades and picks were fetched from the stable, and a piece of canvas to wrap the body in. The two partners were set to work digging under McNab's watchful eye, and Brinklow went off to search the ground anew in the light of what he had learned.

McNab stood a few paces off from the men he was guarding, wishing to encourage them to talk to each other. They did talk in whispers, while he watched them narrowly. Sometimes they cursed each other bitterly, then appeared to make it up with an effort. Simple men they seemed, and McNab thought that he could pretty well read what had happened. Sojer had done the deed, and Bill knew it; perhaps Bill had helped him. They had then agreed together to put the crime off on the young lad.

But so deep was their distrust of each other, they were continually blocking their own game by quarreling. Sojer feared that Bill meant to denounce him, while Bill suspected that Sojer might try to lay the murder at his door.

When Brinklow came back, Sojer hailed him with a wheedling grin. "Sarge," he said, "me and Bill here's been talkin' things over."

"What, again?" said Brinklow.

"We both seen where we made mistakes in what we said. That's nacherl, ain't it, in all the excitement? Bill ain't sure now that it was me he seen kneelin' at the window. No more ain't I sure it was Bill I seen there. Seems like it was a smaller man than Bill. And as to our findin' the body, I recollect now that we both arrived there runnin' the same moment simultaneously."

"That's right. Sergeant," added Bill heavily.

"Well, maybe you turned around and run back again," said Brinklow slyly.

The Sojer pulled up short in his plausible explanation, stared at Brinklow with a falling jaw.

"Climb out of the grave," said Brinklow briskly. "Let's practise a little shootin'."

They obeyed with wary, suspicious glances. Brinklow produced the automatic. "This is the gat that silenced him," he said with a nod towards the corpse. "I've reloaded it. Bill, see that spruce tree yonder with the blaze. Fifty feet, an easy shot. Let me see you hit the blaze."

Bill took the gun in an unconcerned way, threw it into position with the assurance of old experience and pulled the trigger. A black spot appeared in the center of the blaze.

"Good!" said Brinklow, taking the gun. He handed it to Sojer Carpy. "Let's see what you can do."

Sojer's red face looked bluish in his agitation. He raised the gun but his hand shook so that he could not take aim. He endeavored to support it on his left hand. He fired, and the bullet, went wide. He fired again, but no second mark appeared on the blaze of the tree. Sojer flung the gun on the ground.

"I'm too nervous!" he cried with tears in his voice. "Tain't fair to make me shoot when I'm so nervous. I can shoot all right when I ain't nervous!"

Brinklow possessed himself of the gun.

"The grave is deep enough," he said curtly. "Lay the body in it and cover it."

The two policemen stood off a little way watching them at their task. The younger man wondered at the indifference with which the two men threw the earth upon the poor human clay. A man with whom they had eaten and slept for months past! It seemed as if they were devoid of all human feeling. He said to Brinklow in a low tone—

"It must have been Sojer who did it."

Brinklow grinned at him indulgently out of his greater experience, and slowly shook his head.

"But," objected McNab, "according to his own story he ran down the path after Shem. Shem was shot from behind. If Bill Downey came from the other side it couldn't have been him."

"It wasn't either of them," said Brink-low.

McNab stared. "Then who was it?"

"I don't know," said Brinklow.

The two diggers paused in their work, and it could be seen that they were quarreling again.

"It wasn't me!" said Sojer.

"It was you!" said Bill.

Sojer flung down his spade with an oath.

"I'll prove it to you!" he said, starting away from the grave.

McNab made a move to stop him, but Brinklow laid a hand on his shoulder.

"Let them go," he whispered. "The truth may come out."

The two returned to the shack, the policemen following. Sojer was heading for the westerly end, the wall which con-tamed the unbroken window. Rounding the corner, he said, pointing—

"That's where I seen him kneeling, under the window there! Look!" he added excitedly; "You can still see the marks of his knees!"

The two rounded depressions were clearly visible in the soft earth under the window.

Sojer went up near to the two marks, and plumped down on his knees. Springing up again, he cried challengingly:

"Compare them! Compare them! Is them my knees?"

Bill approached on the other side and likewise pressed his knees into the earth.

"Well, they're not mine neither," he said. "Look for yourself!"

To the policemen it was clear without the necessity of taking measurements that the one who had knelt under the window was a smaller man than either Sojer or Bill.

The blood rushed back to Sojer's face; his eyes glittered with exultation. All of a sudden he and Bill were like blood brothers. Sojer pumped his arm up and down crying:

"It wasn't me and it wasn't you! I ask your pardon for suspicioning you. Bill!" He whirled around on Brinklow. "Are you satisfied of that. Sergeant?"

"Perfectly," said Brinklow dryly.

"It was a smaller man than either him or me," Sojer went on examining the marks afresh. "It was that damned cook! I see it all now! Lookin' into the shack from here he could see the gun hangin' by the door. When the girl and Shem bust out of the shack he run round to the door and took the gun, and 'went after him and shot him! We got him where we want him now!"

It sounded only too convincing, and McNab's heart sunk.

"Come on and finish the grave," said Brinklow curtly.

STONES from the lake shore were piled upon the grave to keep the coyotes from digging. McNab shaped a cross out of two pieces of plank and lettered the dead man's name and the date of his death upon it. Further particulars were lacking. Meanwhile, as the afternoon wore on the chill increased, and it became necessary to make the cabin fit for occupancy. The floor was washed and a fire built to sweeten the air. The wounded man was helped to a bed inside, and Nanesis cooked another meal.

Afterwards they sat in front of the fire; Brinklow and Nanesis on the two chairs; McNab sitting on the little table swinging his long legs; Sojer Carpy and Bill Downey squatting on the floor. Even while the sky was full of light outside, the thick walled cabin was dark, and the fire filled its corners with dancing shadows. The wounded man lay on his bed back in the shadows.

"Well, Nanesis," said Brinklow, "tell us your story. First of all, what brought you here?"

The girl looked at him with a proud, calm air.

"I lookin' for white 'osban'," she said.

Sojer and Bill broke into loud guffaws. McNab scowled at them. He saw nothing comic in the girl's proud naturalness.

Nanesis was disconcerted by their laughter.

"Why they laugh?" she asked Brinklow in a low tone.

"Well, my dear," he said dryly "amongst white people the men are always supposed to do the hunting. It is not so really, but our girls never admit that they go looking for husbands."

"I not on'erstan' that," said Nanesis with her proud air. "I spik w'at is in my mind or say not'ing."

There was renewed laughter from the two partners.

"Quite right, too," said Brinklow with a hard glance in that direction, "and if our friends don't mend their manners they can go outside."

The laughter ceased.

"Always I t'ink I half white," Nanesis resumed in her soft voice. "I know my fat'er call' Dick Folsom. Many tam my mot'er tell me 'bout him. She say he ver' pretty yong man wit' curly black hair and red face. Mak' moch fun wit' laugh and sing. He ver' kind man. That is w'at I lak, me. Fish eater treat his woman mean. Dick Folsom is die w'en I a baby, and my mot'er marry Sharley Watusk. Mak' big mistake. Sharley Watusk no good. He mean man. So all tam I live wit' fish eaters. I not lak those people. They not lak me. Say I t'ink too moch myself. Fish eater woman are slaves. I no' slave, me. So there is trouble. Mos'ly wit' Sharley Watusk I got trouble. W'en I little he all tam beat me. W'en I big I tak' the stick and beat him." Nanesis paused. "Always I t'ink I half white," she repeated in a low, thrilling voice. "Now I know better!"

"What," said Brinklow surprised. "Do you mean to say you have no white blood at all?"

"I all white," she said proudly. "My fat'er white, my mot'er white."

The sergeant looked politely incredulous.

"Mary Watusk is dead two weeks," Nanesis went on. "Her I call my mot'er. Before she die she tell me she not my mot'er. She tell me when Dick Folsom come in he bring white wife. He goin' Willow Prairie take up land, but his wife is sick. He got stop beside river, build her shack. I born there. My mot'er die. Dick Folsom go to fish eaters' village get woman tak' care his little baby. Get Mary Watusk. She tak' care so good he marry her to mak' mot'er his baby. They go to Willow Prairie. In the spring one year Dick Folsom is freightin' on the lake. Brak through wit' his team. Never come up. So my mot'er go back to the fish eaters. Got no ot'er place to go. Marry Sharley Watusk. Long tam pass. All forget I not fish eater too."

Nanesis sitting straight in her chair with her hands in her lap and her eyes fixed on the fire, told her story in a proud, quiet voice that asked no pity of her hearers. For that reason it was doubly piteous. It made young McNab grind his teeth with compassion to think of that fine nature condemned to live among the mean fish eaters. Of course they hated her. Her gentle voice played on his heartstrings. Ignorant she might be, but the precious ore was there. She had intelligence and feeling. What a delight it would be to civilize such beauty! Ho glanced resentfully over at the wounded man. Why hadn't he met her first?

Nanesis resumed.

"W'en Mary Watusk die I got moch trouble. All say a girl can't live alone. Many yong men want marry me. I don't know why. I treat them bad. I say 'Go 'way from me, you fish eaters.' But all tam they come around. Then Sharley Watusk he say he goin' marry me. Mak' me mad. Him ogly an' mean an' lame. I say I marry no man I beat wit' a stick! But he spik to head men. Give presents. All say I got marry Sharley Watusk. So I want leave the fish eaters. But got no place to go. I am white but don' know to liv lak white people.

"Men fishin' in the lake see smoke at Cut Across point. Paddle over to look. Say four white men is camp there. Comin' in to tak' up land. Got wait there till beach ice melt. So I t'ink I go see those white men. There is four to choose. If I lak one maybe I marry him. A farmer needs a wife bad. I am a good worker. I can cook and sew and fish and dress skins for him. Maybe he tak' me wit'out I know white man's ways. I am not afraid. I am t'inkin' all white men is good to their women like my fat'er. I know they are bad to red girls, but I am white!

"So I go at night in my canoe. It is rough, and I am slow crossin'. W'en the light come I am still crossin' and Sharley Watusk see me and come after in big canoe wi' three men. So I paddle into little river and hide my canoe. Hide my canoe so good Sharley not find. Not find me. All tam I am watchin'. When Sharley go back I come to white men. I am a little scare then.' They so big. I mak' I can' spik no Anglays. I want find out 'bout them before give myself away. There is three: Blackboard, Redface and Yellowface. They smile at me, mak' moch friend. Jomp aroun', mak' jus' lak fish eaters. I see I can have any one I want, but I not want none. They not true men lak my fat'er. They bad men. Got bad eyes. I sorry I come.

"Bam-bye I see ot'er man, little man, cook. Then I glad I come. When I see him I know he true man to woman lak my fat'er. My heart tell me that. Right away I want him. He do not lak those ot'er men, but he not scare of them neit'er, though he is little. He got proud strong eye. They let him alone. I want him, but he not want me at all. Jus' look at me cool and go on workin'. Never look again. Mak' me mad and sorry too. Not know what mak' wit' a man lak that. I feel bad. I mak'out not look at him no more. But my heart is sore.

"Bam-bye I see him lookin' sideways and I feel glad. He think I not lookin' and he look hard. I see his heart in his eyes. It is sore lak my heart, and I am glad. I see he jus' makin' out not lak me. I see he want me bad. So I look at him lak I not care, jus' to mak' him want me more. I think I mak' all right w'en I spik wit' him. But how can I spik wit' him? I scare ot'er men kill him w'en they see I choose him over all.

"They have tell you how they curse and fight all afternoon over who shall talk to me. Mak' me sick. I see white men no better than fish eaters after all. Only bigger. I not care if they kill each ot'er if they leave the cook alone. Soon as it is dark I t'ink I tak' him away in my canoe. They have no boat to follow. They tell you how they deal the cards for me. Blackbeard win me. Mak' me laugh inside me. Not much good the cards do him with me, I t'ink. I heard them say the cook's name—Phil. A little name, easy to say.

"He help me mak' the supper. The others are cursin'. I watch them close. I say to the cook, not movin' my lips, 'I spik Anglays, Phil.' He is scare'. Bam-bye he say, 'For God's sake w'at you doin' here? Don' you know your danger?' I not answer that. Got no tam. Can't spik right along. Got watch my chance. Bam-bye I say, I white girl, Phil. White fat'er. White mot'er.' He nod his head. Bam-bye I say, 'You lak me, Phil?' He say not'in'. Look at me hard. Squeeze my hand till it mos' break. I am glad. W'en I get not'er chance I say, 'I got canoe here.' He say, 'Get away while you can!' I say, 'I wait till dark. Come wit' me, Phil.' He say, 'You mak' mistake. I on'y cook here. Got not'in' my own.' I say, 'No matter. We paddle to the Settlement. You work for wages. Men are wanted there.' He say, 'You sure you not makin' mistake?' I say, 'I know w'at I want w'en I see it!' He laugh, and the fire shoot out his eyes. 'All right!' he say. 'So do I! At dark we'll beat it!'"

Brinklow chuckled.

"Swiftest courtship on record!" he said in his dry way. But his eyes were friendly.

"W'at is courtship?" asked Nanesis gravely.

"Never mind now. Go on with your story."

"Got no more chance to spik," she said, "They begun to watch us. Never fixed what to do or where to meet at dark. They made me sit to eat with them. Phil, he eat alone. When they want Phil go out, he mad. He curse them. He fight all three. I try tell him wit' my eyes all is right. I will get out. But he not see. They throw him out. I not know where he go then. After that Redface mak' a fight, and they got throw him out. Then Blackbeard and me is alone in the shack. He been drinkin' some. I not moch scare. I know w'at to do."

Young McNab listened to this story with stretched ears. The girl's air of simple courage and truthfulness laid a spell on him. What her brief, bare sentences omitted his imagination could supply. He pictured the scene in the low, dark cabin lighted by a single candle on the table, the fire having almost burned out. The supper dishes had been left on the hearth unwashed. He could see the gross, bearded face of Shem Packer leering at the girl—Shem who was so soon to die; and he could see the grave, beautiful, wary girl who, in that dangerous situation, had nothing but her mother wit to aid her.

"Blackbeard, he spik me ver' friendly," she went on. "Say he goin' marry me. Say he goin' leave his pardners when get to Settlement and we set up for ourselves. Tell me all he got, wagon and many horses, moch money. Say we rich for that country. Long tam he talk. I say not'in', nie. Jus' listen. Always I am watchin' the window for dark to come. Blackbeard tell me what good man he is. Say he ver' kind man to women. I t'ink he lie. His eye is not true. But I friendly too. Not want any trouble till dark come. He want hold my hand. I let him. But no more.

"Bam-bye he want me say somet'in'. He say, 'Wat you say marry me, Nanesis?' I say got t'ink it over. That mak' him little mad. Talk moch and curse. Say I never get such good chance as him. Want me say why I not marry him. Always I say got t'ink it over. He say, 'How long you want t'ink it over?' I say I tell him tomorrow mornin'. He get more mad. Talk bad to me. It is gettin' pretty dark now, so I say got go now. He say, 'Where you goin' tonight? I say I camp by myself. He curse and say, 'No you don't!' You don't leave this shack till you promise marry me!' I say again got t'ink it over.

"He run bar the door. He try catch me. I blow out candle and t'row in fire where he can't get it 'gain. Then I pick up chair, brak window. He t'ink I goin' out that way, so he run there. I run soft back to the door and unbar it. I run out. I call, 'Phil! Phil! Phil!' He is not there. I run for the little river. Blackbeard run after. He is close be'in' me. There is a shot. He fell. More shots."

Nanesis lowered her head. It was evident, notwithstanding her air of composure, that she was deeply agitated. McNab was full of compassion.

"Go on," said Brinklow, after giving her time to recover herself.

"I hear somebody runnin' to me from the river," said Nanesis. "I not know if it is Phil, so I hide be'in' tree. It is Yellowface run by me. I not know where find Phil then. I scare' to call him again. Feel moch bad. Walk among the trees. Not know where I goin'. Then I see a man standin' so quiet like a shadow in the dark; Wah! I am lak wood! I t'ink I weh-ti-go—w'at you say, lose my mind. But it is Phil. Oh! I so glad! I weak lak a rabbit. I am fallin' down, but he hold me."

Nanesis sighed deeply and went on: "You know what happened after that. My canoe is hide in deep grass of little prairie. We go there ver' soft. We put it in the river and go down. In the shallow place Redface and Yellowface jomp out. Redface fire his gun. We got run away and leave canoe. We hear them smashin' it. We go back. Hide in tall grass till the light begin to come. Catch horses and ride up little river. I goin' to the fish eaters at the narrows. Trade horses for canoe and grub and paddle to Settlement. But Redface and Yellowface was be'in' us. Shoot one horse. Shoot ot'er horse. Shoot Phil. Then you come."

The silence that followed upon the completion of the story was broken by Sojer Carpy.

"What'd I telk you?" he cried. "Cookee was right on the spot! It was him shot Shem Packer!"

All the evidence pointed that way, McNab thought anxiously. I wouldn't have been sorry to shoot him myself, he thought, for all of the red coat he wore.

"Phil not shoot Blackbeard," said Nanesis with quiet confidence.

"How do you know that?" demanded Sojer. .

"He tell me," she said proudly.

Sojer and Bill looked at each other and burst into a coarse guffaw. McNab felt his neck swell under the collar of his tunic, but he pressed his lips together. It was not his place to speak in the presence of his superior. As it proved, Nanesis could very well speak for herself.

She stood up, her fine nostrils quivering with indignation.

"Liars!" she said, not loud. "They t'ink all ot'er men liars too!"

Sojer and Bill laughed louder than before, but there was no heart in it. Her scorn penetrated their thick hides.

Brinklow rose. His face expressed nothing.

"Time to turn in," he said. "We'll go into this in the morning."

THE wounded man was lying at one end of the shack and Nanesis made up her bed near, where she could attend upon him during the night. The rest lay at the other end of the room. Brinklow sat up to watch by the fire. A store of wood had been fetched in sufficient to keep it going through the night.

At two o'clock Brinklow awoke McNab to stand watch.

"Keep the fire going," he said, "so they can't turn a trick on you in the dark. Don't let yourself get sleepy. Remember the dugout is lying on the shore. If they got that we'd be up against it."

He lay down to get his well earned sleep, while the young man sat himself in front of the fire, and lit his pipe. Sojer and Bill were making loud music on the nasal trumpet. McNab did not feel sleepy. He had too much to think about. A whole page of life had been unrolled for him that day; the untaught Nanesis had given him a new conception of steadfastness. She had brought to his mind the great things that never changed—love, truth, courage—but which a young man does not often consciously think about.

When he put fresh wood on the fire, the mounting flames lighted up her face. She lay with her hands pressed together under her head for a pillow. Her curled black lashes swept her pale cheeks. In Bleep her face was as beautiful and pure as a child's, and the sight softened the young man's heart completely. If, as seemed certain, Phil Shepley had killed this man, what a tragic time lay ahead of her! He longed to do something to avert it

After awhile the wounded man stirred and groaned. In a twinkling Nanesis was up and kneeling beside his bed without having made a sound. He asked for water. From the pail which stood outside the door she fetched it in a tin cup and partly raised him while she put it to his lips. When she put him down again she kissed his forehead. They murmured together. McNab wondered uncomfortably if, as a good policeman, he ought to insist on hearing what they were saying. The wounded man fell asleep again, holding her hand between his. For a long time Nanesis remained kneeling on the hard floor gazing at him with the look that no woman had as yet given to McNab. It made the young man ache a little with envy.

Bye and bye she gently detached her hand and stood up. As she returned toward her own bed, she looked at McNab in the proud and guarded fashion that was habitual with her. McNab grinned at her with the utmost friendliness and she instantly smiled back. It was like the sun breaking through.