RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

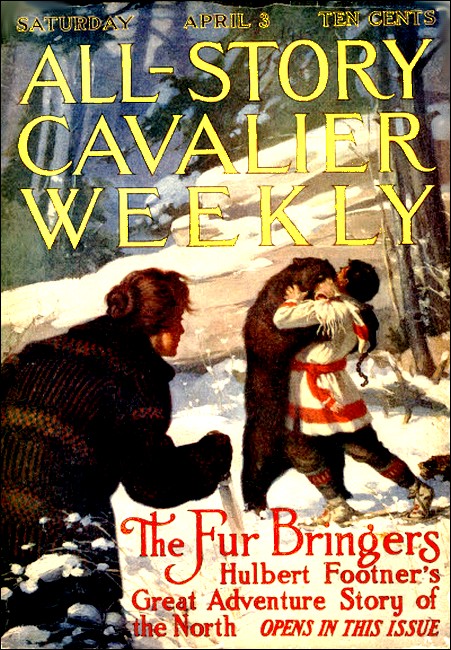

All-Story Cavalier Weekly, 3 Apr 1915, with first part of "The Fur Bringers"

"The Fur Bringers," Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1916

Frontispiece from 1st Edition

Nesis, landing, could not face his look.

The firm of Minot & Doane sat on the doorsill of its store on Lake Miwasa smoking its after-supper pipes.

It was seven o'clock of a brilliant day in June. The westering sun shone comfortably on the world, and a soft breeze kept the mosquitoes at bay.

Moreover, the tobacco was of the best the store afforded; yet there was no peace between the two. They bickered like schoolboys kept indoors.

"How many link-skins in the bale you made up today?" asked Peter Minot.

"Three-seventy-two," his young partner answered in a surly tone that was in itself a provocation.

"I made it three-seventy-three," said Peter curtly.

"What's the difference?" demanded Ambrose Doane.

"Seven dollars," said Peter dryly.

"Well, you can claim the extra one, can't you," snarled Ambrose, "and make an allowance if it's found short?"

"That's not the way I like to do business!"

"Too bad about you!"

The older man frowned darkly, clamped his teeth upon his pipe, and held his tongue.

His silence was an additional aggravation to the other. "What do you want me to do," he burst out with an amount of passion absurdly disproportionate to the matter at issue, "cut it open and count it over and bale it up again?"

"To blazes with it!" said Peter. "I want you to keep your temper!"

"I'm sick of this!" cried Ambrose with the wilful abandon of one hopelessly in the wrong. "You're at me from morning till night! Nothing I do is right. Why can't you leave me alone?"

Peter took his pipe out of his mouth and looked at his young partner in astonishment. His face turned a dull brick color and his blue eyes snapped.

He spoke in a voice of portentous softness: "Who the hell do you think you are? A little gorramighty? To make a mistake is natural; to fly into a temper when it is discovered is childish. What's the matter with you these past ten days, anyway? A man can't look at you but you begin to bark and froth. You'd best go off by yourself a while and eat grass to cool your blood!"

Having delivered himself, Peter pulled deeply at his pipe and gazed across the lake with a scowl of honest resentment.

It was a long speech to come from Peter, and it went unexpectedly to the point. Ambrose was silenced. For a long time neither spoke.

Little by little the angry red faded out of Peter's cheeks and neck, and his forehead smoothed itself. Stealing a glance at young Ambrose, the blue eyes began to twinkle.

"Say!" he said suddenly.

Ambrose twisted petulantly and muttered in his throat.

"Stick out your tongue!" commanded Peter.

Ambrose stared at him in angry stupefaction. "What the deuce—"

"No," said Peter, "you're not sick. Your eyeballs is as clean as new milk; your skin is as pink as a spanked baby. No, you're not sick, so to speak!"

There was another silence, Ambrose squirming a little and blushing under Peter's calm, speculative gaze.

"Have you anything against me?" Peter finally inquired. "If you have, out with it!"

The young man shook his head unhappily.

"Forget it then!" cried Peter with a scornful, kindly grin. "You ornery worthless Slavi, you! You Shushwap! You Siwash! Change your face or you'll give the dog distemper!"

Ambrose laughed sheepishly and stole a glance at his partner. There was pain in his bold eyes, and the wish to bare it to his friend as to a surgeon; but he dreaded Peter's laughter.

There was another long silence. The atmosphere was now much clearer.

Peter, having come to a conclusion, removed his pipe and spoke again: "I know what's the matter with you."

"What?" muttered Ambrose.

"You've got the June fever."

Ambrose made no comment.

"I mind it when I was your age," Peter continued; "when the ice goes out of the lake and the poplar-trees hang out their little earrings, that's when a man catches it—when Molly Cottontail puts on her brown jacket and Skinny Weasel a yellow one. The south wind brings the microbe along with it, and it multiplies in the warm earth. Gee! It makes even an old feller like me poetical. After six months of winter it's hell!"

Still Ambrose kept his eyes down and said nothing.

Peter smoked on, and his eyes became reminiscent. "I mind it well," he continued, "the second spring I was in the country. The first year I didn't notice it so much, but the second year—when the warm weather come I was like a wild man. I saw red! I wanted to fight every man I laid eyes on. I felt like I would go clean off my head if I couldn't smash something!"

Ambrose broke in on Peter's reminiscences. He seemed scarcely to have heard.

"I don't know what's the matter with me!" he cried bitterly. "I can't seem to settle down to anything lately. I've got no use for myself at all. I get so cranky, anybody that speaks to me I want to punch them. God knows I need company, too. It is certainly square of you to put up with me the way you do. I appreciate it—"

"Aw, bosh!" muttered Peter.

"I've tried to work it off!" cried Ambrose. "You know I've worked, though I've generally made a mess of things because I can't keep my mind on anything. My head goes round like a top. Half the time I'm in a daze. I feel as if I was going crazy. I don't know what is the matter with me!"

"Twenty-five years old," murmured Peter; "in the pink of condition! I'm telling you what's the matter with you. It's a plain case of June fever. Ask any of the fellows up here."

"What am I going to do?" said Ambrose. "As it is, I work till I'm ready to drop."

"I mind when I had it," said Peter, "I came to a camp of French half-breeds on Musquasepi, and I saw Eva Lajeunesse for the first time. It was like a blow between the eyes. You do not know what she looked like then. I didn't think about it this way or that; I just up and married her. I was glad to get her!

"Man to man I'll not deny I ain't been sorry sometimes," he went on; "who ain't, sometimes? But, on the whole, after all these years, how could I have done any better? She's good enough for me. A man worries about his children sometimes; but I guess if they go straight there's a place for them, though they are dusky. Eva, she has her bad points, but she's been real good to me. How can I be but grateful!"

This was a rare and unusual confidence for Peter to offer his young partner. Ambrose, flattered and embarrassed, did not know what to say, and said nothing.

He was right, for if he had referred to it, Peter would have been obliged to turn it into a joke. As it was, they smoked on in understanding silence. Finally Peter went on:

"You see, I gave right in. You're different; you want to fight the thing. Blest if I know what to tell you."

"Eva and I don't get on very well," said Ambrose shamefacedly. "She doesn't like me around the house. But I respect her. You know that."

"Sure," said Peter.

"I couldn't do it, Peter," Ambrose went on after a while with seeming irrelevance—howsoever Peter understood. "God knows it's not because I think myself any better than anybody else, or because I think a man does for himself by marrying a—by marrying up here. But I just couldn't do it, that's all."

"No offense," said Peter. "Every man must chop his own trail. I won't say but what you're right. But what are you going to do? A man can't live and die alone."

"I don't know," said Ambrose.

"Tell you what," said Peter; "you take the furs out on the steamboat."

"I won't," said Ambrose quickly. "I went out last year. It's your turn."

"But I'm contented here," said Peter.

Ambrose shook his head. "It wouldn't do me any real good," he said. "It makes it worse after. It did last year. I couldn't bring a white wife up here."

"Well, sir, it's a problem," said Peter with a weighty shake of the head.

This serious, sentimental kind of talk was a strain on both partners. Ambrose made haste to drop the subject.

"I believe I'll start the new warehouse to-morrow," he said. "I like to work with logs. First, I must measure the ground and make a working plan."

Peter was not sorry to be diverted. "Hadn't we better get lumber from the 'Company' mill?" he suggested. "Looks like up to date somehow."

"A board shack looks rotten in the woods?" said Ambrose.

"You're so gol-durn artistic," said Peter quizzically.

Minot & Doane's store was a long log shack with a sod roof sprouting a fine crop of weeds. The original shack had been added to on one side, then on the other. There was a pleasing diversity of outline in the main building and its wings. The whole crouched low on the ground as though for warmth.

Three crooked little windows and three doors so low that a short man had to duck his head under the lintels, faced the lake. The middle door gave ingress to the store proper; the door on the right was the entrance to Peter Minot's household quarters; while that on the left opened to a large room used variously for stores and bunks.

Farther to the left stood the little shack that housed Ambrose Doane in bachelor solitude, and a few steps beyond, the long, low, log stable for the use of the freighters in winter.

Seen from the lake the low, spreading buildings in the rough clearing among gigantic pines were not unpleasing. Rough as they were, they fulfilled the first aim of all architecture; they were suitable to the site.

The traveler by water landed on a stony beach, climbed a low bank and followed a crooked path to the door of the store. On either hand potato and onion patches flourished among the stumps.

From the door-sill where the partners sat, the farther shore of the lake could be seen merely as a delicate line of tree tops poised in the air.

Off to the right their own shore made out in a shallow, sweeping curve, ending half a mile away in a bold hill-point where the Company's post of Fort Moultrie had stood for two hundred years commanding the western end of the lake and its outlet, Great Buffalo River.

To one who should compare the outward aspects of the two establishments, Minot & Doane's offered a ludicrous contrast to the imposing white buildings of Fort Moultrie, arranged military-wise on the grassy promontory; nevertheless, as is not infrequently the case elsewhere, the humbler store did the larger trade.

The coming of Peter Minot ten years before had worked a kind of revolution in the country. He had brought war into the very stronghold of the arrogant fur monopoly, and had succeeded in establishing himself next door. The results were far-reaching. Formerly the Indian sat humbly on the step with his furs until the trader was pleased to open his door; whereas now when the Indian landed, the trader ran down the hill with outstretched hand.

Far and wide Minot & Doane were known as the "free-traders"; and some of their customers journeyed for three hundred miles to trade in the little log store.

The partners were roused by a shrill hail from up the shore. Grateful for the interruption, they hastened to the edge of the bank.

Summer is the dull season in the fur trade. Most of the firm's customers were "pitching off" among the hills, and visitors were rare enough to be notable.

"Poly Goussard," said Ambrose after an instant's examination of the dug-out nosing alongshore. Ambrose's keenness of vision was already known in a land of keen-eyed men.

"Taking his woman to see her folks," added Peter.

Soon the long, slender canoe grounded on the stones below them. It contained in addition to all the worldly goods of the family, a swarthy French half-breed, his Cree wife and three coppery infants in pink calico sunbonnets.

The man climbing over his family indiscriminately, landed and came up the bank with outstretched hand. The woman and children remained sitting like statues in their narrow craft, staring unwinkingly at the white men.

Mrs. Goussard as a full-blooded Cree was considerably below Peter's half-breed wife in the social scale, and she knew better than to make a call uninvited. Even in the north, woman, the conservator, maintains the distinctions.

"Stay all night," urged Peter when formal greetings had been exchanged. "Bring your family ashore."

Poly Goussard shook his head. Poly had a chest like a barrel, a face the color of Baldwin apples and a pair of rolling, gleaming, sloe-black eyes. His head of curly black hair was famous; some one had called him the "Newfoundland dog."

"I promise my wife I sleep wit' her folks to-night," he said. "It is ten miles yet. I jus' come ashore for a little talk."

"Fine!" said Peter, "we're spoiling for news. Come on up to the store and have a cigar."

Seven hundred miles from the railway a cigar is something of a phenomenon. Poly Goussard displayed twenty dazzling teeth and made haste to follow. The three men entered the store and found seats on boxes and bales.

"Me, I work all winter at Fort Enterprise," said Poly.

"So I heard," said Peter. "You've had quite a trip."

The rosy half-breed shrugged. "It is easy. Jus' floatin' down the Spirit River six days."

"What kind of a job did they give you at Enterprise?" asked Peter.

"I drove a team, me, haulin' logs to the saw-mill," said Poly. "There is plentee work at Fort Enterprise."

"The Company's most profitable post," remarked Peter to Ambrose. "They have everything their own way there." The look which accompanied this suggested to Ambrose it would be a good place for Minot & Doane to start a branch.

"What did you think of the place, Poly?" asked Ambrose.

The half-breed flung up his hands and dramatically rolled his eyes.

"Wa! Wa! Towasasuak! It is a gran' place! Jus' lak outside! Trader him live in great big house all make of smooth boards and paint' yellow and red lak the sun! Never I see before such a tall house, and so many rooms inside full of fine chairs and tables so smoot' and shiny.

"He is so reech he put blankets on the floor to walk on, w'at you call carrpitt. Every day he has a white cloth on the table, and a little one to wipe his hands! I have seen it! And silver dishes!"

"There is style for you!" said Peter, with a whimsical roll of his eye in Ambrose's direction.

"There is moch farming by the river at Fort Enterprise," Poly went on; "and plaintee grain grow. There is a mill to grind flour. Steam mak' it go lak the steamboat. They eat eggs and butter at Fort Enterprise, and think not'ing of it. Christmas I have turkey and cranberry sauce. I am going back, me."

"They say the trader John Gaviller is a hard man," suggested Peter.

Poly shrugged elaborately. "Maybe. He owe me not'ing. Me, I would not farm for him nor trade my fur at his store. Those people are his slaves. But he pay a strong man good wages. I will tak' his wages and snap my fingers!

"But wait!" cried Poly with a sparkling eye. "The 'mos' won'erful thing I see at Fort Enterprise—Wa!—the laktrek light! Her shine in little bottles lak pop, but not so big. John Gaviller, him clap his hands, so! and Wa! she shine!

"Indians, him t'ink it is magic. But I am no fool. I know John Gaviller make the laktrek in an engine in the mill. Me, I have seen that engine. I see blue fire inside lak falling stars.

"Gaviller send the laktrek to the store inside a wire. He send some to his house too. They said it cook the dinner, but I think that is a lie. If a man touch that wire they say he will jomp to the roof! Me? I did not try it."

Peter chuckled. "Good man!" he said.

The wonders of Fort Enterprise were not new to Ambrose. Other travelers the preceding summer had brought the same tale. With the air that politeness demanded he only half listened, and pursued his own thoughts.

On the other hand Peter, who delighted in his humble friends, drew out Poly fully. The half-breed told about the bringing in of the winter's catch of fur; of the launching of the great steamboat for the summer season, and many other things.

"Enterprise is sure a wonderful place!" said Peter encouragingly.

"There is something else," said Poly proudly. "At Fort Enterprise there is a white girl!"

The simple sentence had the effect of the ringing of an alarm going inside the dreamy Ambrose. He drew a careful mask over his face, and leaned farther into the shadow.

"So!" said Peter with a glance in the direction of his young partner. "That is news! Who is she?"

"Colina Gaviller, the trader's daughter," said Poly.

"Is she real white?" asked Peter cautiously.

"White as raspberry flowers!" asseverated Poly with extravagant gestures; "white as clouds in the summer! white as sugar! Her hair is lak golden-rod; her eyes blue lak the lake when the wind blows over it in the morning!"

Peter glanced again at his partner, but Ambrose was farthest from the window, and there was nothing to be read in his face.

"Sure," said Peter; "but was her mother a white woman ?"

"They say so," said Poly. "Her long tam dead."

"When did the girl come?" asked Peter.

"Las' fall before the freeze-up," said Poly. "She come down the Spirit River from the Crossing on a raf'. Michel Trudeau and his wife, they bring her. Her fat'er he not know she comin'. Her fat'er want her live outside and be a lady. She say 'no!' She say ladies mak' her sick.' Michel tell me she say that.

"She want always to ride and paddle a canoe and hunt. Michel say she is more brave as a man! John Gaviller say she got go out again this summer. She say 'no!' She is not afraid of him. Me, I t'ink she lak to be the only white girl in the country, lak a queen."

"How old is she?" inquired Peter.

"Twenty years, Michel say," answered Poly. "Ah! she is beautiful!" he went on. "She walk the groun' as sof' and proud and pretty as fine yong horse! She sit her horse like a flower on its stem. Me and her good frens too. She say she lak me for cause I am simple. Often in the winter she ride out wit' my team and hunt in the bush while I am load up."

"What did Eelip say to that?" Peter inquired facetiously. Eelip was Poly's wife.

"Eelip?" queried Poly, surprised. "Colina is the trader's daughter," he carefully explained. "She live in the big house. I would cut off my hand to serve her."

"I suppose Miss Colina has plenty of suitors?" said Peter.

Ambrose hung with suspended breath on the reply.

Poly shook his curly pate. "Who is there for her?" he demanded. "Macfarlane the policeman is too fat; the doctor is too old, his hair is white; the parson is a little, scary man. All are afraid of her; her proud eye mak' a man feel weak inside. There are no ot'er white men there. She is a woman. She mus' have a master. There is no man in the country strong enough for that!"

There was a brief silence in the cabin while Poly relighted his cigar. Ambrose had given no sign of being affected by Poly's tale beyond a slight quivering of the nostrils. But Peter watching him slyly, saw him raise his lids for a moment and saw his dark eyes glowing like coals in a pit. Peter chuckled inwardly, and said:

"Tell us some more about her."

Ambrose's heart warmed gratefully toward his partner. He thirsted for more like a desert traveler for water, but he dared not speak for fear of what he might betray.

"I will tell you 'ow she save Michel Trudeau's life," said Poly, nothing loath, "I am the first to come down the river this summer or you would hear it before. Many times Michel is tell me this story. Never I heard such a story before. A woman to save a man!

"Wa! Every Saturday night Michel tell it at the store. And John Gaviller give him two dollars of tobacco, the best. I guess Michel is glad the trader's daughter save him. Old man proud, lak he is save Michel himself!"

Poly Goussard, having smoked the cigar to within half an inch of his lips, regretfully threw the half inch out the door. He paused, and coughed suggestively. A second cigar being forthcoming, he took the time to light it with tenderest care. Meanwhile, Ambrose kicked the bale on which he sat with an impatient heel.

"It was the Tuesday after Easter," Poly finally began. "It was when the men went out to visit their traps again after big time at the fort. There was moch frash snow fall, and heavy going for the dogs. Colina Gaviller she moch friends with Michel Trudeau for because he was bring her in on his raf las' fall.

"Often she go with him lak she go with me. Michel carry her up on his sledge, and she hunt aroun' while he visit his traps. Michel trap up on the bench three mile from the fort. He not get much fur so near, but live home in a warm house, and work for day's wages for John Gaviller."

Poly paragraphed his story with luxurious puffs at the cigar and careful attention to keep it burning evenly.

"So on Tuesday after Easter they go out toget'er. Colina Gaviller ride on the sledge and Michel he break trail ahead. Come to the bench, leave the dogs in a shelter Michel build in a poplar bluff. Michel go to see his traps, and Colina walk away on her snowshoes wit' her little gun.

"Michel not ver' good lok that day. In his first trap find fool-hen catch herself. He is mad. Second trap is little cross-fox; third trap nothin' 'tall!

"Come to fourth trap, wa! see somesing black on the snow! Wa! Wa! Him heart jomp up! Think him got black fox sure! But no! It is too big. Come close and look. What is he catch you think? It is a black bear!

"Everybody know some tam a bear wake up too soon in winter and come out of his hole and roll aroun' lak he was drunk. He can't find somesing to eat nowhere, and don' know what to do!

"This bear him catch his paw in Michel's little fox trap. It was chain to a little tree. Bear too weak to pull his paw out or break the chain. He lie down lak dead.

"Michel him ver' mad. Him think got no lok at all after Easter. For 'cause that bear is poor as a bird out of the egg. Michel mak' a noise to wake him up. But always he lie still lak dead. Michel think all right.

"Bam-by he lean over with his knife. Wa! Bear jomp up lak he was burn wit' fire! Little chain break and before Michel can tak a breath, bear fetch him a crack with the steel trap acrost his head!

"Wa! Wa! Michel's forehead is bus' open from here to here lak that! Michel drop his knife in the snow. Him get ver' sick. Warm blood run all down his eyes, and he can't see not'ing no more.

"Bear grab Michel round his body and squeeze him pretty near till his eyes jomp out. Michel say a little prayer then. Him say him awful sorry he ain't confessed this year.

"But always he fight that bear and fight some more. Always he is try get his hands aroun' that hairy throat. Bear tear Michel's shoulder with his teeth. Michel feel the hot blood run down inside his shirt and get cold.

"Michel, him always thinkin' Colina is not far, but he will not call to her. She is only a girl him say; she can't do not'ing to a crazy bear. Bear hurt her too, maybe, and John Gaviller is mad for that.

"So Michel he jus' fight. He is ver' tire' now. And always they stamping and tumbling and rolling in the snow, and big red spots drop all aroun'.

"Colina, she tell me the end of it. Colina say she is walkin' sof' in the poplar bush looking sharp and all tam listen for game. All is ver' quiet in the bush.

"Bam-by she hear a fonny little noise way off. Twigs crackling, and somesing bumping and tromping in the snow. Colina think it is big game and go quick. Some tam she stop and listen. Bam-by she hear fonny snarling and grunting. She know there is a fight and she is a little scare. But she go more fas'.

"Wa! Wa! What a sight she sec there! Poor Michel he pretty near done. She can't see his face no more for blood. She think he got no face now. Michel he see her come, and say to her loud as he can: 'Go way! Go way! You get hurt and John Gaviller give me hell!'

"Colina say not know what to do. Them two turn around so fas' she 'fraid to shoot. She run aroun' and aroun' them always looking for a chance. Bam-by she see the handle of Michel's knife in a hole in the snow. She grab it up. She watch her chance. Woof! She stick that bear between the neck and the shoulder!

"That is all!" said Poly. "Bear, him grunt and fall down. Stick his snoot in the snow. Michel crawl away. Colina is fall down too and cry lak a baby. For a little while all three are dead!

"Then Colina wash his wounds with clean snow, and tear up her petticoat for to mak' bandage. She put him on his snowshoes and drag him back where the dogs is. She bring him quick to the fort. In one week Michel is go to his traps same as ever. That is the story!"

"By God, there's a woman!" cried Peter. Ambrose said nothing.

When Poly Goussard reembarked in his dug-out a heavy constraint fell upon the two partners.

Ambrose dreaded to hear Peter call attention to the remarkable coincidence of Poly's story following so close upon their own talk together. He suspected that Peter would want to sit up and thrash the matter to conclusions.

At the bare idea of talking about it Ambrose felt as helpless and sullen as a convicted felon.

In this he underrated Peter's perceptions. Peter had lived in the woods for many years. He intuitively apprehended something of the confusion in the younger man's mind, and he was only anxious to let Ambrose understand that it was not necessary to say anything one way or the other.

But he overdid it a little, and when Ambrose saw that Peter was "on to him," as he would have said, he became still more hang-dog and perverse.

They parted at the door of the store. Peter went off to his family, while Ambrose closed the door of his own little shack behind him, with a long breath of relief.

Feeling as he did, it was torture to be obliged to support the gaze of another's eye, however kindly. So urgent was his need to be alone that he even turned his back on his dog. For a long time the poor beast softly scratched and whined at the closed door unheeded.

Ambrose was busy inside. As it began to grow dark he lit his lamp and carefully pinned a heavy shirt inside his window in lieu of a blind.

Since Peter and his family went to bed with the sun it would be hard to say whom he feared might spy on him. One listening at the door might well have wondered what the activity inside portended.

Later Ambrose opened the door and, putting the dog in, proceeded cautiously to the store. Satisfying himself from the sounds that issued through the connecting door that Peter and his family slept deeply, he lit a candle and quietly robbed the stock of what he required. Then he wrote a note and pinned it beside the store door.

Carrying the bundles back to his cabin, he packed a grub-box and bore it down to the water.

His preparations completed, he went to his shack to bid good-by to his four-footed pal. Job, instantly, comprehending that he was to be left behind, whimpered and nozzled so piteously that Ambrose's heart began to fail.

"I can't take you, old fel'!" he explained. "You're such a common-looking mutt. Of course, I know you're white clear through—but a lady would laugh at you until she knew you!"

Even as he said it his heart accused him of disloyalty. He suddenly changed his mind.

"Come on!" he whispered gruffly. "We'll chance our luck together. If you open your head I'll brain you! Wait here a minute."

Job understood perfectly. He crept down to the lake shore at his master's feet as quiet as a ghost. Seeing the loaded boat he hopped delightedly into his accustomed place in the bow.

During June it never becomes wholly dark in the latitude of Lake Miwasa. An exquisite dim twilight brooded over the wide water and the pine-walled shore. The stars sparkled faintly in an oxidized silver sea. There was no wind now, but the pines breathed like warm-blooded creatures.

Ambrose's breast hummed like a violin to the bow of night. The poetic feeling was there, though the expression was prosaic.

"By George, this is fine!" he murmured.

Job's curly tail thumped the gunwale in answer.

"I'm glad I brought you, old fel'," said Ambrose. "I expect I'd go clean off my head if didn't have any one to talk to!"

Job beat a tattoo on the side of the boat and wriggled and whined in his anxiety to reach his master.

"Steady there!" said Ambrose.

Presently he went on: "Three hundred miles! Six days for Poly to come with the current; nine days to go back! Fifteen days at the best! Anything might happen in that time. . . . Poly said no danger from any of the men there. But some one might come down the river! . . . If wishing could bring an aeroplane up north!"

After a silence: "I wish I could get my best suit pressed! . . . It's two years old, anyway. And she's just come in; she knows the styles. . . . Lord, I'll look like a regular roughneck!"

Next morning when Peter Minot threw open the door of the store he found the note pinned to the door-frame. It was brief and to the point:

Dear Pete:

You said I ought to go by myself till I felt better. So I'm off. Don't expect me till you see me. Charge me with 50 lbs. flour, 18 lbs. bacon, 20 lbs. rice, 10 lbs. sugar, 5 lbs. prunes, 1/2 lb. tea, 1/2 lb. baking powder, and bag of salt. Please take care of my dog. So long! A.D.

P.S.—I'm taking the dog.

Peter, like all men slow to anger, lost his temper with startling effect.

Tearing the note off the door and grinding it under foot, he cursed the

runaway from a full heart.

Eva, hearing, hastily called the children indoors, and thrusting them behind her peeped into the store. Peter, purple in the face, was wildly brandishing his arms.

Eva closed the door very softly and gave the children bread and molasses to keep them quiet. Meanwhile the storm continued to rage.

"The young fool! To run off without a word! I'd have let him go gladly if he'd said anything—and given him a good man! But to go alone! He'll break an arm and die in the bush! And to leave me like this with the year's outfit due next week!

"I'll not see him again until cold weather—if I ever see him! Fifty pounds of flour—with his appetite! He'll starve to death if he doesn't drown himself first! He'll never get to Enterprise! Oh, the consummate young ass! Damn Poly Goussard and his romantic stories!"

John Gaviller and Colina were at breakfast in the big clap-boarded villa at Fort Enterprise.

They were a good-looking pair, and at heart not dissimilar, though it must be taken into account that the same qualities manifest themselves differently in a man of affairs and a romantic, irresponsible young woman.

They were secretly proud of each other—and quarreled continually. Colina, by virtue of her reckless honesty, frequently got the better of her canny father.

"Well," he said, now with a gesture of surrender, "if you're determined to stay here, all right—but you must live differently."

At the word "must" an ominous gleam shot from under Colina's lashes.

"What's the matter with my way of living?" she asked with deceitful mildness.

"This tearing around the country on horseback," he said. "Going off all day hunting with this man and that—and spending the night in native cabins. As long as I considered you were here on a visit I said nothing—"

"Oh, didn't you!" murmured Colina sarcastically.

"—But if you are going to make this country your home, you must consider your reputation in the community just the same as anywhere else—more, indeed; we live in a tiny little world here, where our smallest actions are scrutinized and discussed."

He took a swallow of coffee. Colina played with her food sulkily.

Her silence encouraged him to proceed: "Another thing," he said with a deprecating smile, "comparatively speaking, I occupy an exalted position now. I am the head of all things, such as they are. Great or small this entails certain obligations on a man. I have to study all my words and acts.

"If you are going to stay here with me I shall expect you to assume your share; to consider my interests, to support me; to play the game as they say. What I object to is your impulsiveness, your outspokenness with the people. Remember, everybody here is your dependent. It is always a mistake to be open and frank with dependents. They don't understand it, and if they do, they presume upon it.

"Be guided by my experience; no one could justly accuse me of any lack of affability or friendliness in dealing with the people here—but they never know what I am thinking of!"

"Admirable!" murmured Colina, "but I'm not a directors' meeting!"

"Colina!" said her father indignantly.

"It's not fair for you to drag that in about my standing by you and supporting you!" she went on warmly. "You know I'll do that as long as I live! But I must be allowed to do it in my own way. I'm an adult and an individual. I differ from you. I've a right to differ from you. It is because these people are my inferiors that I can afford to be perfectly natural with them. As for their presuming on it, you needn't fear! I know how to take care of that!"

"A little more reserve," murmured her father.

Colina paused and looked at him levelly. "Dad, what a fool you are about me!" she said coolly.

"Colina!" he cried again, and pounded the table.

She met his indignant glance squarely.

"I mean it," she said. "I'm your daughter, am I not?—and mother's? You must know yourself by this time; you must have known mother—you ought to understand me a little but you won't try—you're clever enough in everything else! You've made up an idea for yourself of what a daughter ought to be, and you're always trying to make me fit it!"

Gaviller scarcely listened to this. "I'll have to bring in a chaperon for you!" he cried.

"Oh, Lord!" groaned Colina. "Anything but that! What do you want me to do?"

"Merely to live like other girls," said Gaviller; "to observe the proprieties."

"That's why I couldn't get along at school," muttered Colina gloomily. "You might as well send me back."

"You're simply headstrong!" said her father severely. "You won't try to be different."

"Dad," said Colina suddenly, "what did you come north for in the first place, thirty years ago?"

The question caught him a little off his guard. "A natural love of adventure, I suppose," he said carelessly.

"Perfectly natural!" said Colina. "Was your father pleased?"

Gaviller began to see her drift. "No!" he said testily.

"And when you went back for her," Colina persisted, "didn't my mother run away north with you, against the wishes of her parents?"

"Your mother was a saint!" cried Gaviller indignantly.

"Certainly," said Colina coolly, "but not the psalm-singing kind. What do you expect of the child of such a couple?"

"Not another word!" cried Gaviller, banging the table—last refuge of outraged fathers.

Colina was unimpressed. "Now you're simply raising a dust to conceal the issue," she said relentlessly.

Gaviller chewed his mustache in offended silence.

Colina did not spare him. "Do you think you can make your child and hers into a prim miss, to sit at home and work embroidery?" she demanded. "Upon my word, if I were a boy I believe you'd suggest putting me in a bank!"

John Gaviller helped himself to another egg with great dignity and removed the top. "Don't be absurd, Colina," he said with a weary air.

It was a transparent assumption. Colina saw that she had reduced him utterly. She smiled winningly. "Dad, if you'd only let me be myself! We could be such pals if you wouldn't try to play the heavy father!"

"Is it being yourself to act like a harum-scarum tomboy?" inquired Gaviller sarcastically.

Colina laughed. "Yes!" she said boldly. "If that's what you want to call it? There's something in me," she went on seriously. "I don't know what it is—some wild strain; something that drives me headlong; makes me see red when I am balked! Maybe it is just too much physical energy.

"Well, if you let me work it off it does no harm. If I can ride all day, or paddle or swim, or go hunting with Michel or one of the others; and be interested in what I'm doing, and come home tired and sleep without dreaming—why everything is all right. But if you insist on cooping me up!—well, I'm likely to turn out something worse than harum-scarum, that's all!"

Gaviller flung up his arms.

"Really, you'll have to go back to your aunt," he said grimly. "The responsibility of looking after you is too great!"

Colina laughed out of sheer vexation. "The silly ideas fathers have!" she cried. "Nobody can look after me, not you, not my aunt, nobody but myself! Why won't you understand that! I don't know exactly what dangers you fancy are threatening me. If it is from men, be at ease! I can put the fear of God into them! It is the sweet and gentle girl you would like to have that is in danger there!"

"I'm afraid you'll have to go back," said Gaviller.

Colina drew her beautiful straight brows together. "You make me think you simply want to get me off your hands," she said sullenly.

Gaviller shook his head. "You know I love to have you with me," he said simply.

"Then consider me a fixture!" said Colina serenely. "This is my country!" she went on enthusiastically. "It suits me. I like its uglinesses and its hardships, too! I hated it in the city. Do you know what they called me?—the wild Highlander!

"Up here everybody understands my wildness, and thinks none the worse of me. It was different in the city—you've always lived in the north, you old innocent—you don't know! Men, for instance, in society they have a curious logic. They seem to think if a girl is natural she must be bad! Sometimes they acted on that assumption—"

"What did I tell you!" cried her father. "Men are the same everywhere!"

"Well," said Colina, smiling to herself, "they didn't get very far. And no man ever tried it twice. Up here—how different. I don't have to think of such things."

"I have to think of settling you in life," said Gaviller gloomily. "There is no one for you up here."

"I'm not bothering my head about that," said Colina. She went on with a kind of splendid insolence: "Every man wants me. I'll choose one when I'm ready. I can't see anything in men except as comrades. The decent ones are timid with women, and the bold ones are—well—rather beastly. I'm looking for a man who's brave and decent, too. If there's no such thing—"

She rose from the table. Colina's was a body designed to fill a riding-habit, and she wore one from morning till night. She was as tall as a man of middle height, and her tawny hair piled on top of her head made her seem taller.

"Well?" said Gaviller.

"Oh, I'll choose the handsomest beast I can find," she said, laughing over her shoulder and escaping from the room before he could answer.

John Gaviller finished his egg with a frown. Colina had this trick of breaking things off in the middle, and it irritated him. He had an orderly mind.

Colina groomed her own horse, whistling like a boy. Saddling him, she rode east along the trail by the river, with the fenced grain fields on her right hand.

Beyond the fields she could gallop at will over the rolling, grassy bottoms, among the patches of scrub and willow.

It was not an impressively beautiful scene—the river was half a mile wide, broken by flat wooded islands overflowed at high water; the banks were low, and at this season muddy. But the sky was as blue as Colina's eyes, and the prairie, quilted with wild flowers, basked in the delicate radiance that only the northern sun can bestow.

On a horse Colina could not be actively unhappy, nevertheless she was conscious of a certain dissatisfaction with life. Not as a result of the discussion with her father—she felt she had come off rather well from that.

But it was warm, and she felt a touch of languor. Fort Enterprise was a little dull in early summer. The fur season was over, and the flour mill was closed; the Indians had gone to their summer camps; and the steamboat had lately departed on her first trip up river, taking most of the company employees in her crew.

There was nothing afoot just now but farming, and Colina was not much interested in that. In short, she was lonesome. She rode idly with long detours inland in search of nothing at all.

Loping over the grass and threading her way among the poplar saplings, Colina proceeded farther than she had ever been in this direction since summer set in.

She saw the painter's brush for the first time—that exquisite rose of the prairies—and instantly dismounted to gather a bunch to thrust in her belt. The delicate, ashy pink of the flower matched the color in her cheeks.

On her rides Colina was accustomed to dismount when she chose, and Ginger, her sorrel gelding, would crop the grass contentedly until she was ready to mount again. To-day the spring must have been in his blood, too.

When Colina went to him he tossed his head coquettishly, and trotting away a few steps, turned and looked at her with a droll air. Colina called him in dulcet tones, and held out an inviting hand.

Ginger waywardly wagged his head and danced with his forefeet.

This was repeated several times—Colina's voice ever growing more honeyed as the rose in her cheeks deepened. The inevitable happened—she lost her temper and stamped her foot; whereupon Ginger, with lifted tail, ran around her like a circus horse.

Colina, alternately cajoling and commanding, pursued him bootlessly. Fond as she was of exercise, she preferred having the horse use his legs. She sat down in the grass and cried a little out of sheer impotence.

Ginger resumed his interrupted meal on the grass with insulting unconcern. Colina was twelve miles from home—and hungry.

Desperately casting her eyes around the horizon to discover some way out of her dilemma, Colina perceived a thin spiral of smoke rising above the edge of the river bank about a quarter of a mile away.

She had no idea who could be camping on the river at this place, but she instantly set off with her own confident assurance of finding aid. Ginger displayed no inclination to leave the particular patch of prairie grass he had chosen for his luncheon.

As Colina approached the edge of the bank she heard a voice. She herself made no sound in the grass.

Looking over the edge she saw a man and a dog on the stony beach below, both with their backs to her and oblivious of her approach. Of the man, she had a glimpse only of a broad blue flannel back and a mop of black hair.

She heard him say to the dog: "Our last meal alone, old fel'! To-night, if we're lucky, we'll dine with her!"

This conveyed nothing to Colina—she was to remember it later.

In speaking he turned his profile, and she received an agreeable shock; he was young; he was not common; he had a fair, pink skin that contrasted oddly with his swarthy locks; his bold profile accorded with her fancy.

What caught her off her guard was his affectionate, quizzical glance at the dog.

It was a seductive glimpse of a stern face softened.

The dog scented her and barked; the man turning sprang to his feet. Colina experienced a sudden and extraordinary confusion of her faculties.

He was taller than she expected—that was not it; in the glance of his eager dark eyes there was a quality that took her completely by surprise—that took her breath away. This in one of the sex she condescended to!

The young man was completely dumfounded by the sight of her. He hung in suspended motion; his wide eyes leaped to hers—and clung there. They silently gazed at each other—each with much the same pained and breathless look.

Colina struggled hard against the spell. She was badly flustered. "Please catch my horse for me," she said with, under the circumstances, intolerable hauteur.

He did not move. She saw a dull, red tide creep up from his neck, over his face and into his hair. She had never seen such a painful blush. He kept his head up, and though his eyes became agonized with embarrassment, they clung doggedly to hers.

She knew intuitively that he blushed because he fancied that she, from his rough clothes, had judged him to be a common tramp.

She was glad of it—his blush gave her a little security.

But she could not support his glance. She all but stamped her foot as she said: "Didn't you hear me?"

With a visible effort the young man collected his wits, and with unsmiling face started to climb toward Colina. The dog, making to follow him, he spoke a word of command and it returned to the boat. Face to face with him Colina felt as if his glowing dark eyes were burning holes in her.

"Where is he?" he asked soberly.

Colina merely pointed across the bottoms where Ginger could be seen still busy with the grass.

"I'll bring him to you," he said coolly, and started off.

His assurance exasperated Colina. "It isn't as easy as you think," she said haughtily, "or I shouldn't have asked for help!"

He turned his head, his face suddenly breaking into a beaming smile. "I know horses," he said.

Colina was furious. He made her feel like a little girl. She bit her lips to keep in the undignified answer that sprang to them. Inside her she said it: "Smarty! I shall laugh when he leads you a chase!" She sat down in the grass under a poplar-tree, prepared to enjoy the circus from afar.

There was none. Ginger having tired of his waywardness, perhaps, or having eaten his fill, quietly allowed himself to be taken. The young man came riding back on him. Colina could almost have wept with mortification.

He slipped out of the saddle beside her and stood waiting for her to mount. There was no consciousness of triumph in his manner.

His eyes flew back to hers with the same extraordinarily naïve glance. When Colina frowned under it he literally dragged them away, but in spite of him they soon returned.

Many a man's eyes had been offered to Colina, but never a pair that glowed with a fire like this. They were at the same time bold and humble. They contained an imploring appeal without any sacrifice of self-respect. They disturbed Colina to such a degree she scarcely knew what she was doing.

He offered her a hand to mount, and she drew back with an offended air. He instantly yielded, and she mounted unaided—mounted awkwardly, and bit her lip again.

He did not immediately loose her rein. Out of the corner of her eye Colina saw that he was breathing fast.

"It will he late before you get home," he said. His voice was very low—she could feel the effort he was making not to let it shake. "Will you—will you eat with me?"

The modest tendering of this bold invitation disarmed Colina. She hesitated. He went on with a touch of boyish eagerness: "There's only a traveler's grub, of course. I got a fish on a night-line this morning. Also there's a prairie chicken roasted yesterday."

A self-deceiving argument ran through Colina's brain like quick-silver: "If I go, I shall be tormented by the feeling that he got the best of me; if I stay a while I can put him in his place!"

She dismounted. The young man turned abruptly to tie Ginger to the poplar-tree, but even in the boundary of his cheek Colina read his beaming happiness.

With scarcely another glance at her he plunged down the bank and set to work over his fire. Colina sedately followed and seated herself on a boulder to wait until she should be served.

Now that he no longer looked at her, Colina could not help watching him. A dangerous softness began to work in her breast; he was so boyish, so clumsy, so anxious to entertain her fittingly—his unconsciousness of her nearness was such a transparent assumption.

Colina was alarmed by her own weakness. She looked resolutely at the dog.

He was a mongrel black and tan, bigger than a terrier, and he had a ridiculous curly tail. He had received her with an insulting air of indifference.

"What an ugly dog!" Colina said coolly.

The young man swung around and affectionately rubbed the dog's ear.

"The best sporting dog in Athabasca," he said promptly, but without any resentment.

Colina bit her lip again. It seemed as if everything she did was mean. "Of course his looks haven't anything to do with his good qualities," she said. Here she was apologizing.

"He's almost human," said the young man. "I talk to him like a person."

"Come here, dog," said Colina.

The animal was suddenly stricken with deafness.

"What's his name?" she asked.

"Job."

"Come here, Job!" said Colina coaxingly.

Job looked out across the river.

"Job!" said his master sternly.

The dog sprang to him as if they had been parted for years, and frantically licked his hand. This display of boundless affection was suspiciously self-conscious.

The young man led him to Colina's feet. "Mind your manners!" he commanded.

Job in utter abasement offered her a limp paw. She touched it, and he scampered back to his former place with an air of relief, and turning his back to her lay down again. It cannot be said that his enforced obedience made her feel any better.

Lunch was not long in preparing, for the rice had been on the fire when Colina first appeared. The young man set forth the meal as temptingly as he could on a flat rock, and at the risk of breaking his sinews carried another rock for Colina to sit upon. His apologies for the discrepancies in the service disarmed Colina again.

"I am no fine lady," she said. "I know what it is to live out."

Colina was hungry and the food good. A good understanding rapidly established itself between them. But the young man made no move to serve himself. Indeed he sat at the other side of the rock-table and produced his pipe.

"Why don't you eat?" demanded Colina.

"There is plenty of time," he said, blushing.

"But why wait?"

"Well—there's only one knife and fork."

"Is that all?" said Colina coolly. "We can pass them back and forth—can't we?"

Starting up and dropping the pipe in his pocket he flashed a look of extraordinary rapture on her that brought Colina's eyelids fluttering down like winged birds. He was a disconcerting young man. Resentment moved her, but she couldn't think of anything to say.

They ate amicably, passing the utensils back and forth.

After a while Colina asked: "Do you know who I am?"

"Of course," he said. "Miss Colina Gaviller."

"I don't know you," she said.

"I am Ambrose Doane, of Moultrie."

"Where is Moultrie?"

"On Lake Miwasa—three hundred miles down the river."

"Three hundred miles!" exclaimed Colina. "Have you come so far alone?"

"I have Job," Ambrose said with a smile.

"How much farther are you going?" she asked.

"Only to Fort Enterprise."

"Oh!" she said. The question in the air was: "What did you come for?" Both felt it.

"Do you know my father?" Colina asked.

"No," said Ambrose.

"I suppose you have business with him?"

"No," he said again.

Colina glanced at him with a shade of annoyance. "We don't have many visitors in the summer," she said carelessly.

"I suppose not," said Ambrose simply.

Colina was a woman—and an impulsive one; it was bound to come sooner or later: "What did you come for?"

His eyes pounced on hers with the same look of mixed boldness and apprehension that she had marked before; she saw that he caught his breath before answering.

"To see you!" he said.

Colina saw it coming, and would have given worlds to have recalled the question. She blushed all over—a horrible, unequivocal, burning blush. She hated herself for blushing—and hated him for making her.

"Upon my word!" she stammered. It was all she could get out.

He did not triumph over her discomfiture; his eyes were cast down, and his hand trembled. Colina could not tell whether he were more bold or simple. She had a sinking fear that here was a young man capable of setting all her maxims on men at naught. She didn't know what to do with him.

"What do you know about me?" she demanded.

It sounded feeble in her own ears. She felt that whatever she might say he was marching steadily over her defenses. Somehow, everything that he said made them more intimate.

"There was a fellow from here came by our place," said Ambrose simply. "Poly Goussard. He told us about you—"

"Talked about me!" cried Colina stormily.

"You should have heard what he said," said Ambrose with his venturesome, diffident smile. "He thinks you are the most beautiful woman in the world!" Ambrose's eyes added that he agreed with Poly.

It was impossible for Colina to be angry at this, though she wished to be. She maintained a haughty silence.

Ambrose faltered a little.

"I—I haven't talked to a white girl in a year," he said. "This is our slack season—so I—I came to see you."

If Colina had been a man this was very like what she might have said—-to meet with candor equal to her own in the other sex, however, took all the wind out of her sails.

"How dare you!" she murmured, conscious of sounding ridiculous.

Ambrose cast down his eyes. "I have not said anything insulting," he said doggedly. "After what Poly said it was natural for me to want to come and see you."

"In the slack season," she murmured sarcastically.

"I couldn't have come in the winter," he said naïvely.

Colina despised herself for disputing with him. She knew she ought to have left at once—but she was unable to think of a sufficiently telling remark to cover a dignified retreat.

"You are presumptuous!" she said haughtily.

"Presumptuous?" he repeated with a puzzled air.

She decided that he was more simple than bold. "I mean that men do not say such things to women," she began as one might rebuke a little boy—but the conclusion was lamentable, "to women to whom they have not even been introduced!"

"Oh," he said, "I'm sorry! I can only stay a few days. I wanted to get acquainted as quickly as possible."

A still small voice whispered to Colina that this was a young man after her own heart. Aloud she remarked languidly: "How about me? Perhaps I am not so anxious."

He looked at her doubtfully, not quite knowing how to take this. "Really he is too simple!" thought Colina.

"Of course I knew I would have to take my chance," he said. "I didn't expect you to be waiting on the bank with a brass band and a wreath of flowers!"

He smiled so boyishly that Colina, in spite of herself, was obliged to smile back. Suddenly the absurd image caused them to burst out laughing simultaneously—and Colina felt herself lost.

Laughter was as dangerous as a train of gunpowder. Even while he laughed Colina saw that look spring out of his eyes—the mysterious look that made her feel faint and helpless.

He leaned toward her and a still more candid avowal trembled on his lips. Colina saw it coming. Her look of panic-terror restrained him. He closed his mouth firmly and turned away his head.

Presently he offered her a breast of prairie chicken with a matter-of-fact air. She shook her head, and a silence fell between them—a terrible silence.

"Oh, why don't I go!" thought Colina despairingly.

It was Ambrose who eased the tension by saying comfortably: "It's a great experience to travel alone. Your senses seem to be more alert—you take in more."

He went on to tell her about his trip, and Colina lulled to security almost before she knew it was recounting her own journey in the preceding autumn. It was astonishing when they stuck to ordinary matters—how like old friends they felt. Things did not need to be explained.

It provided Colina with a good opportunity to retire. She rose.

Ambrose's face fell absurdly. "Must you go?" he said.

"I suppose I will meet you officially—later," she said.

He raised a pair of perplexed eyes to her face. "I never thought about an introduction," he said quite humbly. "You see we never had any ladies up here."

In the light of his uncertainty Colina felt more assured. "Oh, we're sufficiently introduced by this time," she said offhand.

"But—what should I do at the fort?" he asked. "How can I see you again?"

She smiled with a touch of scorn at his simplicity. "That is for you to contrive. You will naturally call on my father; if he likes you, he will bring you home to dinner."

Ambrose smiled with obscure meaning. "He will never do that," he said.

"Why not?" demanded Colina.

"My partner and I are free-traders," he explained; "the only free-traders of any account in the Company's territory. Naturally they are bitter against us."

"But business is one thing and hospitality another," said Colina.

"You do not know what hard feeling there is in the fur trade," he suggested.

"You do not know my father," she retorted.

"Only by reputation," said Ambrose.

The shade of meaning in his voice was not lost on her. Her cheeks became warm. "All white men who come to the post dine with us as a matter of course," she said. "We owe you the hospitality. I invite you now in his name and my own."

"I would rather you asked him about me first," said Ambrose.

This made Colina really angry. "I do not consult him about household matters," she said stiffly.

"Of course not," said Ambrose; "but in this case I would be more comfortable if you spoke to him first."

"Are you afraid of him?" she inquired with raised eyebrows.

"No," said Ambrose coolly; "but I don't want to get you into trouble."

Colina's eyes snapped. "Thank you," she said; "you needn't be anxious. You had better come—we dine at seven."

"I will be there," he said.

By this time she was mounted. As she gave Ginger his head Ambrose deftly caught her hand and kissed it. Colina was not displeased. If it had been self-consciously done she would have fumed.

She rode home with an uncomfortable little thought nagging at her breast. Was he really so simple as she had decided? Had he not baited her into losing her temper—and insisting on his coming to dinner? Surely he could not know her so well as that!

"Anyway, he is coming!" she thought with a little gush of satisfaction she did not stop to examine. "I'll wear evening dress, the black taffeta, and my string of pearls. At my own table it will be easier—and with father there to support me! We will see!"

Colina did not see her father until he came home from the store for dinner. She was already dressed and engaged in arranging the table.

John Gaviller's eyes gleamed approvingly at the sight of her in her finery. Black silk became Colina's blond beauty admirably. Manlike, he arrogated the extra preparations to himself. He thought it was a kind of peace offering from Colina.

"Well!" he began jocularly, only to check himself at the sight of three places set at the table. "Who's coming?" he demanded with natural surprise.

Colina, busying herself attentively with the centerpiece of painter's brush, wondered if her father had met Ambrose Doane. She gave him a brief, offhand account of her adventure without mentioning their guest's name.

"But who is it?" he asked.

She answered a little breathlessly; "Ambrose Doane of Moultrie."

Gaviller's face changed slightly. "H-m!" he said non-committally.

"Doesn't the table look nice?" said Colina quickly.

"Very nice," he said.

"We must prove to ourselves once in a while that we are not savages!"

"Naturally! Do you want me to dress?"

Colina, who had not looked at her father, nevertheless felt the inimical atmosphere. She stooped to a touch of flattery. "You are always well dressed," she said, smiling at him.

"Hm!" said Gaviller again. "Call me when you're ready." He marched off to his library.

Colina breathed freely. So far so good! Ambrose Doane had not been to call on her father. He was hardly the simple youth she had decided. But she couldn't think the less of him for that.

When she heard the door-bell ring—Gaviller's house boasted the only door-bell north of Caribou Lake—her heart astonished her with its thumping. She ran up to her own room. Ambrose according to instructions previously given was to be shown into the drawing-room.

Another wonder of Gaviller's house was the full-length mirror imported for Colina. She ran to it now. It treated her kindly. The crisp, thin, dead-black draperies showed up her white skin in dazzling contrast.

On second thought she left off the string of pearls. The effect was better without any ornament. Her face was her despair; her eyes were misty and unsure; the color came and went in her cheeks; she could not keep her lips closed.

"You fool! You fool!" she stormed at herself. "A man you have seen once! He will despise you!"

She could not keep the dinner waiting. Bracing herself, she started for the hall. A final glance in the mirror gave her better heart. After all she was beautiful and beautifully dressed. She descended the stairs slowly, whispering to herself at every step: "Be game!"

Though the sun was still shining out-of-doors, according to Colina's fancy, every night at this hour the shutters were closed and the lamps lighted. The drawing-room was lighted by a single, tall lamp with a yellow shade.

Ambrose was standing in the middle of the room. He had changed his clothes. His suit was somewhat wrinkled, and his boots unpolished, but he looked less badly than he thought. At sight of Colina he caught his breath and turned very pale. His eyes widened with something akin to awe. Colina was suddenly relieved.

"So you dared to come!" she said with a careless smile.

He did not answer. Plainly he could not. He stood as if rooted to the floor. Colina had meant to offer him her hand, but suddenly changed her mind.

Instead, with reckless bravado considering her late state of mind, she went to the lamp and turned it up. She felt his honest, stricken glance following her, and thrilled under it.

"You have not met my father?"

Ambrose "took a brace" as he would have said. "No," he answered.

"I thought very likely you would see him this afternoon," she said with a touch of smiling malice.

His directness foiled it.

"I waited down the river," he said. "I didn't want to have a row with him that might spoil to-night."

"What a terrible opinion you have of poor father!" said Colina.

"Does he know I'm coming?" asked Ambrose.

"Certainly!"

"What did he say?"

"Nothing! What should he say?"

"He has boasted that no free-trader ever dared set foot in his territory."

"I don't believe it! It's not like him. Come along and you'll see."

"Wait!" said Ambrose quickly. "Half a minute!"

Colina looked at him curiously.

"You don't know what this means to me!" he went on, his glowing, unsmiling eyes fixed on her. "A lady's drawing-room! A lamp with a soft, pretty shade!—and you—like that! I—I wasn't prepared for it!"

Colina laughed softly. She was filled with a great tenderness for him, therefore she could jeer a little.

Ambrose had not moved from the spot where she found him.

"It's not fair," he went on. "You don't need that! It bowls a man over."

This was the ordinary language of gallantry—yet it was different. Colina liked it. "Come on," she said lightly, "father is like a bear when he is kept waiting for dinner!"

The two men shook hands in a natural, friendly way. With another man Ambrose was quite at ease. Colina approved the way her youth stood up to the famous old trader without flinching. They took places at the table, and the meal went swimmingly.

Ambrose, whether he felt his affable host's secret animosity and was stimulated by it, or for another reason, suddenly blossomed into an entertainer. When her father was present he addressed Colina's ear, her chin or her golden top-knot, never her eyes.

John Gaviller apparently never looked at her either, but Colina knew he was watching her closely. She was not alarmed. She had herself well in hand, and there was nothing in her politely smiling, slightly scornful air to give the most anxious parent concern.

Under the jokes, the laughter, and the friendly talk throughout dinner, there were electric intimations that caused Colina's nostrils to quiver. She loved the smell of danger.

It was no easy matter to keep the conversational bark on an even keel; the rocks were thick on every hand. Business, politics, and local affairs were all for obvious reasons tabooed. More than once they were near an upset, as when they began to talk of Indians.

Ambrose had related the anecdote of Tom Beavertail who, upon seeing a steamboat for the first time, had made a paddle-wheel for his canoe, and forced his sons to turn him about the lake.

"Exactly like them!" said John Gaviller with his air of amused scorn. "Ingenious in perfectly useless ways! Featherheaded as schoolboys!"

"But I like schoolboys!" Ambrose protested. "It isn't so long since I was one myself."

"Schoolboys is too good a word," said Gaviller. "Say, apes."

"I have a kind of fellow-feeling for them," said Ambrose smiling.

"How long have you been in the north?"

"Two years."

"I've been dealing with them thirty years," said Gaviller with an air of finality.

Ambrose refused to be silenced. Looking around the luxurious room he felt inclined to remark, that Gaviller had made a pretty good thing out of the despised race, but he checked himself.

"Sometimes I think we never give them a show," he said with a deprecating air, "We're always trying to cut them to our own pattern instead of taking them as they are. They are like schoolboys, as you say.

"Most of the trouble with them comes from the fact that anybody can lead them into mischief, just like boys. If we think of what we were like ourselves before we put on long trousers it helps to understand them."

Gaviller raised his eyebrows a little at hearing the law laid down by twenty-five years old.

"Ah!" he said quizzically. "In my day the use of the rod was thought necessary to make boys into men!"

Ambrose grew a little warm. "Certainly!" he said. "But it depends on the spirit with which it is applied. How can we do anything with them if we treat them like dirt?"

"You are quite successful in handling them?" queried Gaviller dryly.

"Peter Minot says so," said Ambrose simply. "That is why he took me into partnership."

"He married a Cree, didn't he?" inquired Gaviller casually.

Colina glanced at her father in surprise. This was hardly playing fair according to her notions.

"A half-breed," corrected Ambrose.

"Of course, Eva Lajeunesse, I remember now," said Gaviller. "She was quite famous around Caribou Lake some years ago."

Ambrose with an effort kept his temper. "She has made him a good wife," he said loyally.

"Ah, no doubt!" said Gaviller affably. "Do you live with them?"

"I have my own house," said Ambrose stiffly.

Here Colina made haste to create a diversion.

"Aren't the Indian kids comical little souls?" she remarked. "I go to the mission school sometimes to sing and play for them. They don't think much of it. One of the girls asked me for a hair. One hair was all she wanted."

The subject of Indian children proved to be innocuous. They took coffee in John Gaviller's library.

"Colina brought these new-fangled notions in with her," said her father.

"They're all right!" said Ambrose soberly.

Colina saw the hand that held his spoon tremble slightly, and wondered why. The fact was the thought could not but occur to him: "How foolish for me to think she could ever bring her lovely, ladylike ways to my little shack!"

He thrust the unnerving thought away. "I can build a bigger house, can't I?" he demanded of himself. "Anyway, I'll make the best play to get her that I can!"

In the library they talked about furniture. It transpired that the trader had a passion for cabinet making, and most of the objects that surrounded them were examples of his skill. Ambrose admired them with due politeness, meanwhile his heart was sinking. He could not see the slightest chance of getting a word alone with Colina.

In the middle of the evening a breed came to the door, hat in hand, to say that John Gaviller's Hereford bull was lying down in his stall and groaning. The trader bit his lip and glanced at Colina.

"Would you like to come and see my beasts?" he asked affably.

"Thanks," said Ambrose just as politely. "I'm no hand with cattle." He kept his eyes discreetly down.

Gaviller could not very well turn him out of the house. There was no help for it. He went.

The instant the door closed behind Gaviller, Ambrose's eyes flamed up. "What a stroke of luck!" he cried.

It had something the effect of an explosion there in the quiet room where they had been talking so prosily. Colina became panicky. "I don't understand you!" she said haughtily.

"You do!" he cried. "You know I didn't paddle three hundred miles up-stream to talk to him! Never in my life had I anything so hard to go through with as the last two hours. I didn't dare look at you for fear of giving myself away."

There was an extraordinary quality of passion in the simple words. Colina felt faint and terrified. What was one to do with a man like this! She mounted her queenliest manner. "Don't make me sorry I asked you here," she said.

"Sorry?" he said. "Why should you be? You can do what you like! I can't pretend. I must say my say the best way I can. I may not get another chance!"

Colina had to fight both herself and him. She made a gallant stand. "You are ridiculous!" she said. "I will leave the room until my father comes back if you can't contain yourself."

He was plainly terrified by the threat, nevertheless he had the assurance to put himself between her and the door.

"You have no cause to be angry with me," he said. "You know I do not disrespect you!" He was silent for a moment. His voice broke huskily. "You are wonderful to me! I have to keep telling myself you are only a woman—of flesh and blood like myself—else I would be groveling on the floor at your feet, and you would despise me!"

Colina stared at him in haughty silence.

"I love you!" he whispered with odd abruptness. "No woman need be insulted by hearing that. You came upon me to-day like a bolt of lightning. You have put your mark on me for life! I will never be myself again."

His voice changed; he faltered, and searched for words. "I know I'm rough! I know women like to be courted regularly. It's right, too! But I have no time! I may never see you alone again. Your father will take care of that! I must tell you while I can. You can take your time to answer."

Colina contrived to laugh.

The sound maddened him. He took a step forward, and a vein in his forehead stood out. She held her ground disdainfully.

"Don't do that!" he whispered. "It's not fair! I—I can't stand it!"

"Why must you tell me?" asked Colina. "What do you expect?"

"You!" he whispered hoarsely. "If God is good to me! For life."

"You are mad!" she murmured.

"Maybe," he said, eying her with the resentment which is so closely akin to love; "but I think you understand my madness. Talking gets us nowhere. A dozen times to-day your eyes answered mine. Either you feel it too or you are a coquette!"

This brought a genuine anger to Colina's aid. Her weakness fled. "How dare you!" she cried with blazing eyes.

"Coquette!" he repeated doggedly. "To dress yourself up like that to drive me mad!"

Colina forgot the social amenities. "You fool!" she cried. "This is my ordinary way of dressing at night! It is not for you!"

"It was for me!" he said sullenly. "You were happy when you saw its effect on me! If it's only a game I can't play it with you. It means too much to me!"

"Coquette!" still made a clangor in Colina's brain that deafened her to everything else. "You are a savage!" she cried. "I'm sorry I asked you here. You needn't wait for my father to come back. Go!"

"Not without a plain answer!" he said.

Colina tried to laugh; she was too angry. "My answer is no!" she cried with outrageous scorn. "Now go!"

He stood studying her from under lowering brows. The sight of her like that—head thrown back, eyes glittering, cheeks scarlet, and lips curled—was like a lash upon his manhood. The answer was plain enough, but an instinct from the great mother herself bade him disregard it. Suddenly his eyes flamed up.

"You beauty!" he cried.

Before she could move he had seized her in her finery. Colina was no weakling, but within those steely arms she was helpless. She strained away her head. He could only reach her neck, under the ear. She yielded shudderingly.

"I hate you! I hate you!" she murmured.

Their lips met.

Colina swayed ominously on his arm. She sank down on the sofa, still straining away from him, but weakly. Suddenly she burst into passionate weeping.

"What have you done to me!" she murmured.

At sight of the tears he collapsed. "Ah, don't!" he whispered brokenly. "You break my heart! My darling love! What is the matter?"

"I am a fool—a fool!—a fool!" she sobbed tempestuously. "To have given in to you! You will despise me!"

He slipped to the floor at her feet. He strove desperately to comfort her. Tenderness lent eloquence to his clumsy, unaccustomed tongue.

"Ah, don't say that! It's like sticking a knife in me! My lovely one! As if I could! You are everything to me! I have nothing in the world but you! Forgive me for being so rough! I couldn't help it! I couldn't go by anything you said. I had to find out for sure! It had to happen! What does it matter whether it was in a day or a year? The minute I saw you I knew how it was. I knew I had to have you or live like a priest till I died."

Colina was not to be comforted. "You think so now!" she said. "Later, when you have tired of me a little, or if we quarreled, you would remember that I—I was too easily won!"

"Ah, don't!" he cried exasperated. "If you say it again I'll have to swear. What more can I say? I love you like my life! I could not despise you without despising myself! I don't know how to put it. I sound like a fool! But—but this is what I mean. You make me seem worth while to myself."

Colina's hands stole to her breast. "Ah! If I could believe you!" she breathed.

"Give me time!" he begged. "What good does talking do! What I do will show you!"

Little by little she allowed him to console her. Her arm stole around his shoulders, her head was lowered until her cheek lay in his hair.

They came down to earth. Ambrose seated himself beside her, and looking in her shamed face laughed softly and deep. "You fraud," he said.

Colina hid her face. "Don't!" she begged.

He laughed more.

"What are you laughing at?" she demanded.

"To think how you scared me," he said. "With your grand clothes and high and mighty airs. I had to dig my toes into the floor to keep from cutting and running. And it was all bluff!"

"Scared you!" said Colina. "I never in my life knew a man so utterly regardless and brutal!"

"You like it," he said. Colina blushed.

"I had no line to go on," said Ambrose with his engaging simplicity. "I never made love to any girls. I haven't read many books either. I guess that's all guff, anyway. I didn't know how the thing ought to be carried through. But something told me if I knuckled under to you the least bit it would be all day with Ambrose."

They laughed together.

John Gaviller's step sounded on the porch outside. They sprang up aghast. They had completely forgotten his existence.

"Oh, Heavens!" whispered Colina. "He has eyes like a lynx!"

Ambrose's eyes, darting around the room, fell upon an album of snapshots lying on the table. He flung it open.

When Gaviller came in he found them standing at the table, their backs to him. He heard Ambrose ask:

"Who is that comical little guy?"

Colina replied: "Ahcunazie, one of the Kakisa Indians in his winter clothes."

Colina turned, presenting a sufficiently composed face to her father. "Oh," she said. "You were gone a long while. What was the matter with the bull?"

She strolled to the sofa and sat down. Ambrose idly closed the book and sat down across the room from her. Gaviller glanced from one to another—perhaps it was a little too well done. But his face instantly resumed its customary affability.

"Nothing serious," he said. "He is quite all right again."

Ambrose was tormented by the desire to laugh. He dared not meet Colina's eye. "It is terrible to lose a valuable animal up here," he said demurely.

After a few desultory polite exchanges Ambrose got up to go. "I was waiting to say good night to you," he explained.

"You are camping down the river, I believe."

"Half a mile below the English mission. I paddled up."

"I'll walk to the edge of the bank with you," said Gaviller politely.

As in nearly all company posts there was a flag-pole in the most conspicuous spot on the river-bank. It was halfway between Gaviller's house and the store. At the foot of the pole was a lookout-bench worn smooth by generations of sitters.

Leaving the house after a formal good night to Colina, Ambrose was escorted as far as the bench by John Gaviller. The trader held forth amiably upon the weather and crops. They paused.

"Sit down for a moment," said Gaviller. "I have something particular to say to you."

Ambrose suspected what was coming. But humming with happiness like a top as he was, he could not feel greatly concerned.

Still in the same calm, polite voice Gaviller said:

"I confess I was astonished at your assurance in coming to my house."

This was a frank declaration of war. Ambrose, steeling himself, replied warily: "I did not come on business."

"What did you come for?"

Ambrose did not feel obliged to be as frank with father as with daughter. "I am merely looking at the country."

"Well, now that you have seen Fort Enterprise," said Gaviller dryly, "you may go on or go back. I do not care so long as you do not linger."

Ambrose frowned. "If you were a younger man—" he began.