RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

All-Story Weekly, 13 Nov 1915, with first part of "The Huntress"

"The Huntress," The James A. McCann Company, New York, 1922

Frontispiece.

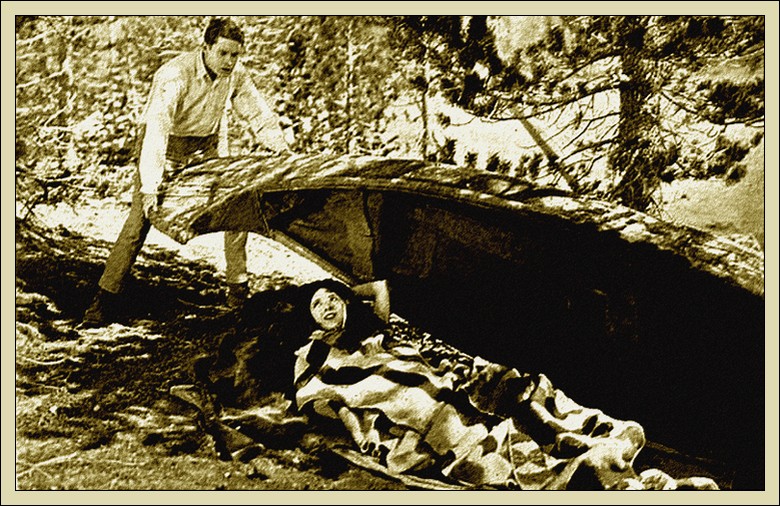

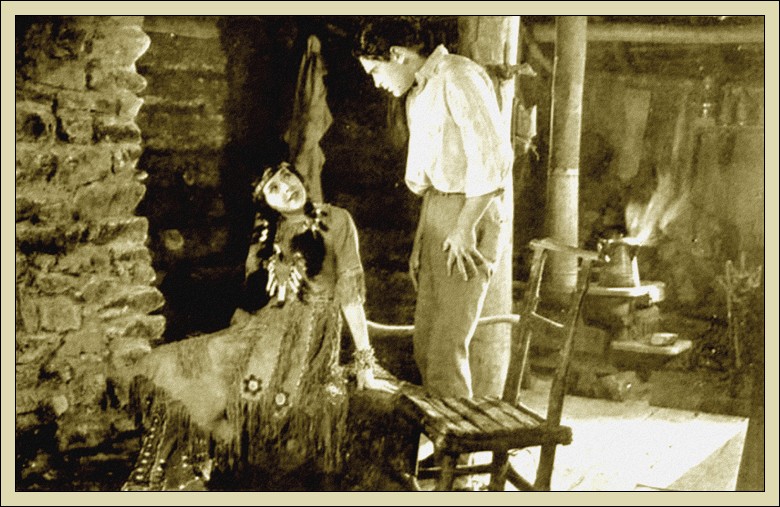

Bela (Colleen Moore) says to Gladding (Lloyd Hughes): "Fine surprise um white man."

FROM within the teepee of Charley Whitefish issued the sounds of a family brawl. It was of frequent occurrence in this teepee. Men at the doors of other lodges, engaged in cleaning their guns, or in other light occupations suitable to the manly dignity, shrugged with strong scorn for the man who could not keep his women in order. With the shrugs went warning glances toward their own laborious spouses.

Each man's scorn might well have been mitigated with thankfulness that he was not cursed with a daughter like Charley's Bela. Bela was a firebrand in the village, a scandal to the whole tribe. Some said she was possessed of a devil; according to others she was a girl born with the heart of a man.

This phenomenon was unique in their experience, and being a simple folk they resented it. Bela refused to accept the common lot of women. It was not enough for her that such and such a thing had always been so in the tribe.

She would not do a woman's tasks (unless she happened to feel like it); she would not hold her tongue in the presence of men. Indeed, she had been known to talk back to the head man himself, and she had had the last word into the bargain.

Not content with her own misbehaviour, Bela lost no opportunity of gibing at the other women, the hard-working girls, the silent, patient squaws, for submitting to their fathers, brothers, and husbands. This naturally enraged all the men.

Charley Whitefish was violently objurgated on the subject, but he was a poor-spirited creature who dared not take a stick to Bela. It must be said that Bela did not get much sympathy from the women. Most of them hated her with an astonishing bitterness.

As Neenah, Hooliam's wife, explained it to Eelip Moosa, a visitor in camp: "That girl Bela, she is weh-ti-go, crazy, I think. She got a bad eye. Her eye dry you up when she look. You can't say nothing at all. Her tongue is like a dog-whip. I hate her. I scare for my children when she come around. I think maybe she steal my baby. Because they say weh-ti-gos got drink a baby's blood to melt the ice in their brains. I wish she go way. We have no peace here till she go."

"Down the river they say Bela a very pretty girl," remarked Eelip.

"Yah! What good is pretty if you crazy in the head!" retorted Neenah. "She twenty years old and got no husband. Now she never get no husband, because everybody on the lake know she crazy. Two, three years ago many young men come after her. They like her because she light-coloured, and got red in her cheeks. Me, I think she ugly like the grass that grows under a log. Many young men come, I tell you, but Bela spit on them and call fools. She think she better than anybody.

"Last fall Charley go up to the head of the lake and say all around what a fine girl he got. There was a young man from the Spirit River country, he say he take her. He come so far he not hear she crazy. Give Charley a horse to bind the bargain. So they come back together. It was a strong young man, and the son of a chief. He wear gold embroidered vest, and doeskin moccasins worked with red and blue silk. He is call Beavertail.

"He glad when he see Bela's pale forehead and red cheeks. Men are like that. Nobody here tell him she crazy, because all want him take her away. So he speak very nice to her. She show him her teeth back and speak ugly. She got no shame at all for a woman. She say: 'You think you're a man, eh? I can run faster than you. I can paddle a canoe faster than you. I can shoot straighter than you!' Did you ever hear anything like that?

"By and by Beavertail is mad, and he say he race her with canoes. Everybody go to the lake to see. They want Beavertail to beat her good. The men make bets. They start up by Big Stone Point and paddle to the river. It was like queen's birthday at the settlement. They come down side by side till almost there. Then Bela push ahead. Wa! she beat him easy. She got no sense.

"After, when he come along, she push him canoe with her paddle and turn him in the water. She laugh and paddle away. The men got go pull Beavertail out. That night he is steal his horse back from Charley and ride home.

"Everybody tell the story round the lake. She not get a husband now I think. We never get rid of her, maybe. She is proud, too. She wash herself and comb her hair all the time. Foolishness. Treat us like dirt. She is crazy. We hate her."

Such was the conventional estimate of Bela. In the whole camp this morning, at the sounds of strife issuing from her father's teepee, the only head that was turned with a look of compassion for her was that of old Musq'oosis the hunchback.

His teepee was beside the river, a little removed from the others. He sat at the door, sunning himself, smoking, meditating, looking for all the world like a little old wrinkled muskrat squatting on his haunches.

If it had not been for Musq'oosis, Bela's lot in the tribe would long ago have become unbearable. Musq'oosis was her friend, and he was a person of consequence. The position of his teepee suggested his social status. He was with them, but not of them. He was so old all his relations were dead. He remained with the Fish-Eaters because he loved the lake, and could not be happy away from it. For their part they were glad to have him stay; he brought credit to the tribe.

As one marked by God and gifted with superior wisdom, the people were inclined to venerate Musq'oosis even to the point of according him supernatural attributes. Musq'oosis laughed at their superstitions, and refused to profit by them. This they were unable to understand; was it not bad for business?

But while they resented his laughter, they did not cease to be secretly in awe of him, and all were ready enough to seek his advice. When they came to him Musq'oosis offered them sound sense without any supernatural admixture.

In earlier days Musq'oosis had sojourned for a while in Prince George, the town of the white man, and there he had picked up much of the white man's strange lore. This he had imparted to Bela—that was why she was crazy, they said.

He had taught Bela to speak English. Bela's first-hand observations of the great white race had been limited to half a score of individuals—priests, policemen, and traders.

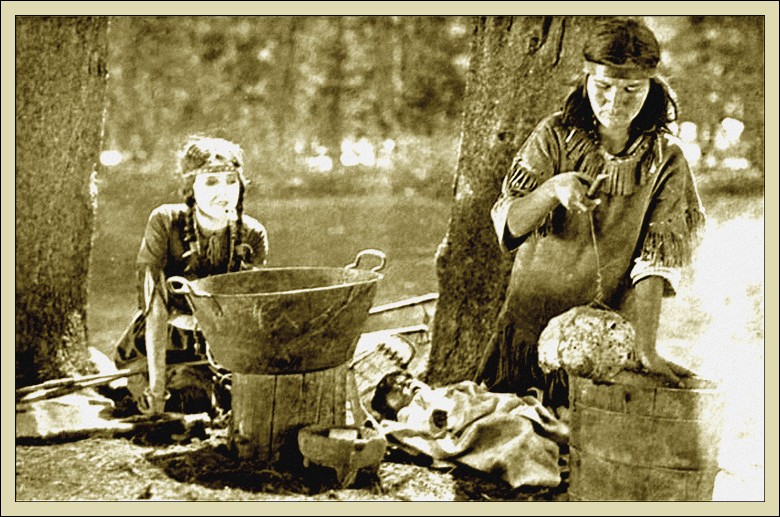

The row in Charley's teepee had started early that morning. Charley, bringing in a couple of skunks from his traps, had ordered Bela to skin them and stretch the pelts. She had refused point blank, giving as her reasons in the first place that she wanted to go fishing; in the second place, that she didn't like the smell.

Both reasons seemed preposterous to Charley. It was for men to fish while women worked on shore. As for a smell, whoever heard of anybody objecting to such a thing. Wasn't the village full of smells?

Nevertheless, Bela had gone fishing. Bela was a duck for water. Since no one would give her a boat, she had travelled twenty miles on her own account to find a suitable cottonwood tree, and had then cut it down unaided, hollowed, shaped, and scraped it, and finally brought it home as good a boat as any in the camp.

Since that time, early and late, the lake had been her favourite haunt. Caribou Lake enjoys an unenviable reputation for weather; Bela thought nothing of crossing the ten miles in any stress.

When she returned from fishing, the skunks were still there, and the quarrel had recommenced. The result was no different. Charley finally issued out of the teepee beaten, and the little carcasses flew out of the door after him, propelled by a vigorous foot. Charley, swaggering abroad as a man does who has just been worsted at home, sought his mates for sympathy.

He took his way to the river bank in the middle of camp, where a number of the young men were making or repairing boats for the summer fishing just now beginning. They had heard all that had passed in the teepee, and, while affecting to pay no attention to Charley, were primed for him—showing that men in a crowd are much the same white or red.

Charley was a skinny, anxious-looking little man, withered and blackened as last year's leaves, ugly as a spider. His self-conscious braggadocio invited derision.

"Huh!" cried one. "Here come woman-Charley. Driven out by the man of the teepee!"

A great laugh greeted this sally. The soul of the little man writhed inside him.

"Did she lay a stick to your back, Charley?"

"She give him no breakfast till he bring wood."

"Hey, Charley, get a petticoat to cover your legs. My woman maybe give you her old one."

He sat down among them, grinning as a man might grin on the rack. He filled his pipe with a nonchalant air belied by his shaking hand, and sought to brave it out. They had no mercy on him. They out vied each other in outrageous chaffing.

Suddenly he turned on them shrilly. "Coyotes! Grave-robbers! May you be cursed with a woman-devil like I am. Then we'll see!"

This was what they desired. They stopped work and rolled on the ground in their laughter. They were stimulated to the highest flights of wit.

Charley walked away up the river-bank and hid himself in the bush. There he sat brooding and brooding on his wrongs until all the world turned red before his eyes. For years that fiend of a girl had made him a laughing-stock. She was none of his blood. He would stand it no longer.

The upshot of all his brooding was that he cut himself a staff of willow two fingers thick, and carrying it as inconspicuously as possible, crept back to the village.

At the door of his teepee he picked up the two little carcasses and entered. He had avoided the river-bank, but they saw him, and saw the stick, and drew near to witness the fun.

Within the circle of the teepee Charley's wife, Loseis, was mixing dough in a pan. Opposite her Bela, the cause of all the trouble, knelt on the ground carefully filing the points of her fish-hooks. Fish-hooks were hard to come by.

Charley stopped within the entrance, glaring at her. Bela, looking up, instantly divined from his bloodshot eyes and from the hand he kept behind him what was in store. Coolly putting her tackle behind her, she rose.

She was taller than her supposed father, full-bosomed and round-limbed as a sculptor's ideal. In a community of waist less, neckless women she was as slender as a young tree, and held her head like a swan.

She kept her mouth close shut like a hardy boy, and her eyes gleamed with a fire of resolution which no other pair of eyes in the camp could match. It was for the conscious superiority of her glance that she was hated. One from the outside would have remarked quickly how different she was from the others, but these were a thoughtless, mongrel people.

Charley flung the little beasts at her feet. "Skin them," he said thickly. "Now."

She said nothing—words were a waste of time, but watched warily for his first move.

He repeated his command. Bela saw the end of the stick and smiled.

Charley sprang at her with a snarl of rage, brandishing the stick. She nimbly evaded the blow. From the ground the wife and mother watched motionless with wide eyes.

Bela, laughing, ran in and seized the stick as he attempted to raise it again. They struggled for possession of it, staggering all over the teepee, falling against the poles, trampling in and out of the embers. Loseis shielded the pan of dough with her body. Bela finally wrenched the stick from Charley and in her turn raised it.

Charley's courage went out like a blown lamp. He turned to run. Whack! came the stick between his shoulders. With a mournful howl he ducked under the flap, Bela after him. Whack! Whack! A little cloud arose from his coat at each stroke, and a double wale of dust was left upon it.

A whoop of derision greeted them as they emerged into the air. Charley scuttled like a rabbit across the enclosure, and lost himself in the bush. Bela stood glaring around at the guffawing men.

"You pigs!" she cried.

Suddenly she made for the nearest, brandishing her staff. They scattered, laughing.

Bela returned to the teepee, head held high. Her mother, a patient, stolid squaw, still sat as she had left her, hands motionless in the dough. Bela stood for a moment, breathing hard, her face working oddly.

Suddenly she flung herself on the ground in a tempest of weeping. Her startled mother stared at her uncomprehendingly. For an Indian woman to cry is rare enough; to cry in a moment of triumph, unheard of. Bela was strange to her own mother.

"Pigs! Pigs! Pigs!" she cried between sobs. "I hate them! I not know what pigs are till I see them in the sty at the mission. Then I think of these people! Pigs they are! I hate them! They not my people!"

Loseis, with a jerk like an automaton, recommenced kneading the dough.

Bela raised a streaming, accusing face to her mother.

"What for you take a man like that?" she cried passionately. "A weasel, a mouse, a flea of a man! A dog is more of a man than he! He run from me squeaking like a puppy!"

"My mother gave me to him," murmured the squaw apologetically.

"You took him!" cried Bela. "You go with him! Was he the best man you could get? I jump in the lake before I shame my children with a coyote for a father!"

Loseis looked strangely at her daughter. "Charley not your father," she said abruptly.

Bela pulled up short in the middle of her passionate outburst, stared at her mother with fallen jaw.

"You twenty year old," went on Loseis. "Nineteen year I marry Charley. I have another husband before that."

"Why you never tell me?" murmured Bela, amazed.

"So long ago!" Loseis replied with a shrug. "What's the use?"

Bela's tears were effectually called in. "Tell me, what kind of man my father?" she eagerly demanded.

"He was a white man."

"A white man!" repeated Bela, staring. There was a silence in the teepee while it sunk in. A deep rose mantled the girl's cheeks.

"What he called?" she asked.

"Walter Forest." On the Indian woman's tongue it was "Hoo-alter."

"Real white?" demanded Bela.

"His skin white as a dog's tooth," answered Loseis, "his hair bright like the sun." A gleam in the dull eyes as she said this suggested that the stolid squaw was human, too.

"Was he good to you?"

"He was good to me. Not like Indian husband. He like dress me up fine. All the time laugh and make jokes. He call me 'Tagger-Leelee.'"

"Did he go away?"

Loseis shook her head. "Go through the ice with his team."

"Under the water—my father," murmured Bela.

She turned on her mother accusingly. "You have good white husband, and you take Charley after!"

"My mother make me," Loseis said with sad stolidity.

Bela pondered on these matters, filled with a deep excitement. Her mother kneaded the dough.

"I half a white woman," the girl murmured at last, more to herself than the other. "That is why I strange here."

Again her mother looked at her intently, presaging another disclosure. "Me, my father a white man too," she said in her abrupt way. "It is forgotten now."

Bela stared at her mother, breathing quickly.

"Then—I 'most white!" she whispered, with amazed and brightening eyes. "Now I understand my heart!" she suddenly cried aloud. "Always I love the white people, but I not know. Always I ask Musq'oosis tell me what they do. I love them because they live nice. They not pigs like these people. They are my people! All is clear to me!" She rose.

"What you do?" asked Loseis anxiously.

"I will go to my people!" cried Bela, looking away as if she envisaged the whole white race.

The Indian mother raised her eyes in a swift glance of passionate supplication—but her lips were tight. Bela did not see the look.

"I go talk to Musq'oosis," she said. "He tell me all to do."

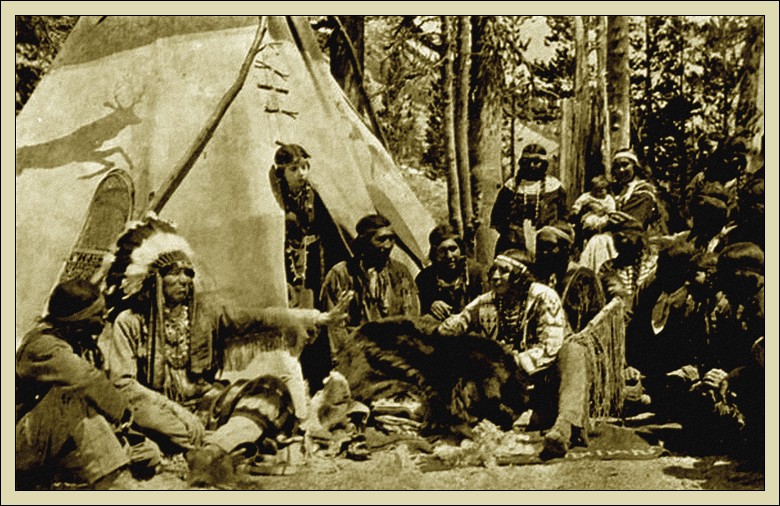

THE village of the Fish-Eaters was built in a narrow meadow behind a pine grove and the little river. It was a small village of a dozen teepees set up in a rough semicircle open to the stream.

This stream (Hah-Wah-Sepi they call it) came down from the Jack-Knife Mountains to the north, and after passing the village, rounded a point of the pines, traversed a wide sand-bar and was received into Caribou Lake.

The opposite bank was heavily fringed with willows. Thus the village was snugly hidden between the pines and the willows, and one might have sailed up and down the lake a dozen times without suspecting its existence. In this the Indians followed their ancient instinct. For generations there had been no enemies to hide from.

It was at the end of May; the meadow was like a rug of rich emerald velvet, and the willows were freshly decked in their pale leafage. The whole scene was mantled with the exquisite radiance of the northern summer sun. Children and dogs loafed and rolled in aimless ecstasy, and the whole people sat at the teepee openings blinking comfortably.

The conical teepees themselves, each with a bundle of sticks at the top and its thread of smoke, made no inharmonious note in the scene of nature. Only upon a close look was the loveliness a little marred by evidences of the Fish-Eaters' careless housekeeping.

Musq'oosis's lodge stood by itself outside the semicircle and a little down stream. The owner was still sitting at the door, an odd little bundle in a blanket, as Bela approached.

"I t'ink you come soon," he said. These two always conversed in English.

"You know everyt'ing," stated Bela simply.

He shrugged. "I just sit quiet, and my thoughts speak to me."

She dropped on her knees before him, and rested sitting on her heels, hands in lap. Without any preamble she said simply: "My fat'er a white man."

Musq'oosis betrayed no surprise. "I know that," he replied.

"My mot'er's fat'er, he white man too," she went on.

He nodded.

"Why you never tell me?" she asked, frowning slightly.

He spread out his palms. "What's the use? You want to go. Got no place to go. Too much yo'ng to go. I t'ink you feel bad if I tell."

She shook her head. "Mak me feel good. I know what's the matter wit' me now. I understand all. I was mad for cause I think I got poor mis'able fat'er lak Charley."

"It is well," said Musq'oosis.

"You know my fat'er?" asked Bela eagerly.

He nodded gravely.

"Tell me."

Musq'oosis seemed to look within. "Long tam ago," he began, "though I am not yo'ng then neither. It was in the Louis Riel war I see your fat'er. He a soldier in that war, wear red coat, ver' fine. Ot'er soldier call him Smiler Forest. Red people call him Bird-Mouth for cause he all tam mak' music wit' his wind, so"—here Musq'oosis imitated a man whistling. "He is one good soldier. Brave. The Great Mother across the water send him a medal wit' her face on it for cause he so brave."

"What is medal?" interrupted Bela.

"Little round piece lak money, but not to spend," explained Musq'oosis. "It is pin on the coat here, so everybody know you brave.

"Always I am a friend of the white people," Musq'oosis went on, "so I fight for them in that war. I can't march me, or ride ver' good. I canoe scout on the Saskatchewan River. Your fat'er is friend to me. Moch we talk by the fire. He mak' moch fun to me, but I not mad for cause I see he lak me just the same. Often he say to me, 'Musq'oosis, my boy, I bad lot.'"

"Bad lot?" questioned Bela,

"He mean no good," Musq'oosis explained. "That is his joke. I not believe ev'ryt'ing he tell me, no, not by a damnsight. He say, 'Musq'oosis, I no good for not'ing 't'all but a soldier.' He say, 'When there ain't no war I can't keep out of trouble.' He ask moch question about my country up here. He say, 'When this war over I go there. Maybe I can keep out of trouble up there.'

"Me, I all tam think that just his joke. Bam-by the fighting all over, and Louis Riel sent to jail. Me, I got brot'ers up here then. I want to see my brot'ers after the war. So I go say good-bye to my friend. But he say, 'Hold on, Musq'oosis, I goin' too.' I say, 'W'at you do up there? Ain't no white men but the comp'ny trader.' He say, 'I got fight somesing. I fight nature.'"

"Nature?" repeated Bela, puzzled.

Musq'oosis shrugged. "That just his fonny way of talk. He mean chop tree, dig earth, work. So he come wit' me. He ver' good partner to trip. All tam laugh and sing and mak' music wit' his wind. He is talk to me just the same lak I was white man, too. Me, I never have no friend lak that. I lak Walter Forest more as if he was my son."

The old man's head drooped at this point, and the story seemed to have reached its end.

"What do you do when you come here, you two?" Bela eagerly demanded.

Musq'oosis sighed and went on. "The Fish-Eaters was camp down the lake by Musquasepi then. Your mot'er was there. She ver' pretty girl. Mos' pretties' girl in the tribe, I guess."

"Pretty?" said Bela, amazed.

"She is the first one we see when we come. We are paddling up the river and she is setting muskrat trap on the bank. Your fat'er look at her. Her look at your fat'er. Both are lak wood with looking. Wa! I think me, Bird-Mouth ain't goin' to keep out of trouble up here neither! Well, he is lak crazy man after that. All night he want stay awake and talk me about her. He ask me what her name mean. I tell him Loseis mean little duck. He say, 'Nobody ever got better name.' 'Better wait,' I say, 'plenty ot'er girl to see.' 'Not for me,' he say.

"In a week he marry her. Marry her honest wit' priest and book. He build a house at Nine-Mile Point and a stable. Say he goin' to keep stopping-house for freighters when they bring in the company's outfit in the winter. He cut moch hay by Musquasepi for his stable. He work lak ten red men. When the ice come, right away he start to freight his hay across. I say 'Wait, it is not safe yet.' He laugh.

"One day come big storm wit' snow. He got lost out on the ice wit' his team and drive in airhole. We find the hay floating after. He never see you. You come in the spring. He was a fine man. That is all."

After a silence Musq'oosis said: "Well, what you think? What you goin' do?"

"I goin' outside," Bela promptly answered. "To my fat'er's country."

Musq'oosis shook his head heavily. "It is far. Many days' journey down the little river and the big river to the landing. From the landing four days' walk to town. I am too old to travel so far."

"I not afraid travel alone," exclaimed Bela.

Musq'oosis continued to shake his head. "What you goin' do in town?" he asked.

"I marry a white man," replied Bela coolly.

Musq'oosis betrayed no astonishment. "That is not easy," he observed with a judicial air. "Not easy when there are white women after them. They know too moch for you. Get ahead of you."

"I am a handsome girl," said Bela calmly. "You have say it. You tell me white men crazy for handsome girls."

"It is the truth," returned Musq'oosis readily. "But not for marry."

"My fat'er marry my mot'er," persisted Bela.

"Ot'er white men not same lak your fat'er."

Bela's face fell. "Well, what must I do?" she asked.

"There is moch to be said. If you clever you mak' your white man marry you."

"How?" she demanded.

Musq'oosis shrugged. "I can't tell you in one word," he replied.

"I can't stay with these people," she said, frowning.

"All right," said Musq'oosis. "But stay in the country. This is your country. You know the way of this country. I tell you somesing else. You got some money here."

"Money?" she echoed, opening her eyes wide.

"When your fat'er die, he have credit wit' the company. Near six hundred dollars. Beaton, the old company trader, he talk wit' me for cause I your fat'er's friend. He say this money too little to go to law wit'. The law is too far from us. He say 'I not give it to Loseis, because her people get it. They only poor, shiftless people, just blow it in on foolishness.' He say, 'I goin' keep it for the child.' I say, 'All right.'

"Well, bam-by Beaton leave the company, go back home outside. He give me an order on the new trader. He say keep it till Bela grow up. I have it now. So I say to you, this money buy you a team, mak' you rich in this country. But outside it is nothing. I say to you, don't go outside. Marry a white man here."

Bela considered this. "Which one?" she asked. "There is only Stiffy and Mahooly, the traders. The gov'ment won't let the police to marry."

"Wait," said Musq'oosis impressively. "More white men are coming. Many white men are coming."

"I can't wait," complained Bela rebelliously. "Soon I be old."

"Some are here already," he added.

She looked at him questioningly.

"Las' week," he went on, "the big winds blow all the ice down the lake. It is calm again. The sun is strong. So I put my canoe in the water and paddle out. Me, I can't walk ver' good. Can't moch ride a horse. But my arm's strong. When I yo'ng, no man so strong lak me on a paddle. So I paddle out on the lake. Smell sweet as honey; shine lak she jus' made to-day. Old man feel lak he was yo'ng too.

"Bam-by far across the lake I see little bit smoke. Wa! I think, who is there now? I look, I see the sky is clean as a scraped skin. I think no wind to-day. So I go across to see who it is. I go to Nine-Mile Point where your fat'er built a house long time ago. You know it. Wa! Wa! There is five white men stopping there, with moch horses and wagons, big outfit. Rich men.

"So I spell wit' them a while. They mak' moch fun. Call me ol' black Joe. Feed me ver' good. We talk after. They say gov'ment goin' measure all the land at the head of lake this summer and give away to farmers. So they come to get a piece of land. They are the first of many to come. Four strong men, and anot'er who cooks for them. They got wait over there till ice on the shore melt so they drive around."

"All right. I will marry one of them," announced Bela promptly.

"Wait!" said Musq'oosis again, "there is moch to be said."

"Why you not tell me when you come back?" she demanded.

"I got think first what is best for you."

"Maybe they got girls now," she suggested, frowning.

"No girls around the lake lak you," he stated.

She was mollified.

"Do everything I tell you or you mak' a fool!" he remarked impressively.

"Tell me," she asked amenably.

"Listen. White men is fonny. Don't think moch of somesing come easy. If you want get white man and keep him, you got mak' him work for you. Got mak' him wait a while. I am old. I have seen it. I know."

Bela's eyes flashed imperiously. "But I want him now," she insisted.

"You are a fool!" said Musq'oosis calmly. "If you go after him, he laugh at you. You got mak' out you don' want him at all. You got mak' him run after you."

Bela considered this, frowning. An instinct in her own breast told her the old man was right, but it was hard to resign herself to an extended campaign. Spring was in the air, and her need to escape from the Fish-Eaters great.

"All right," she agreed sullenly at last.

"How you goin' pick out best man of the five?" asked Musq'oosis slyly.

"I tak' the strongest man," she answered promptly.

He shook his head in his exasperating way. "How you goin' know the strongest?"

"Who carries the biggest pack," she said, surprised at such a foolish question.

Musq'oosis's head still wagged. "Red man carry bigger pack than white man," he said oracularly. "Red man's arm and his leg and his back strong as white man. But white man is the master. Why is that?"

She had no answer.

"I tell you," he went on. "Who is the best man in this country?"

"Bishop Lajeunesse," she replied unhesitatingly.

"It is the truth," he agreed. "But Bishop Lajeunesse little skinny man. Can't carry big pack at all. Why is he the best man?"

This was too much of a poser for Bela. "I don't want marry him," she muttered.

"I tell you," said Musq'oosis sternly. "Listen well. You are a foolish woman. Bishop Lajeunesse is the bes' man for cause no ot'er man can look him down. White men stronger than red men for cause they got stronger fire in their eyes. So I tell you when you choose a 'osban', tak' a man with a strong eye."

The girl looked at him startled. This was a new thought.

Musq'oosis, having made his point, relaxed his stern port. "To-morrow if the sun shine we cross the lake," he said amiably. "While we paddle I tell you many more things. We pass by Nine-Mile Point lak we goin' somewhere else. Not let on we thinkin' of them at all. They will call us ashore, and we stay jus' little while. You mus' look at them at all. You do everyt'ing I say, I get you good 'osban'."

"Bishop Lajeunesse coming up the river soon," suggested Bela. "Will you get me 'osban' for him marry? I lak marry by Bishop Lajeunesse."

"Foolish woman!" repeated Musq'oosis. "How do I know? A great work takes time!"

Bela pouted.

Musq'oosis rose stiffly to his feet. "I give you somesing," he said.

Shuffling inside the teepee, he presently reappeared with a little bundle wrapped in folds of dressed moose hide. Sitting calm he undid it deliberately. A pearl-handled revolver was revealed to Bela's eager eyes.

"The white man's short gun," he said. "Your fat'er gave it long tam ago. I keep her ver' careful. Still shoot straight. Here are shells, too. Tak' it, and keep her clean. Keep it inside your dress. Good thing for girl to have."

Bela's instinct was to run away to examine her prize in secret. As she rose the old man pointed a portentous finger.

"Remember what I tell you! You got mak' yourself hard to get."

During the rest of the day Bela was unobtrusively busy with her preparations for the journey. Like any girl, red or white, she had her little store of finery to draw on. Charley did not show himself in the tepee.

Her mother, seeing what she was about, watched her with tragic eyes and closed mouth. At evening, without a word, she handed her a little bag of bread and meat. Bela took it in an embarrassed silence. The whole blood of the two women cried for endearments that their red training forbade them.

More than once during the night Bela arose to look at the weather. It was with satisfaction that she heard the pine-trees complaining. In the morning the white horses would be leaping on the lake outside.

She had no intention of taking Musq'oosis with her. She respected the old man's advice, and meant to apply it, but an imperious instinct told her this was her own affair that she could best manage for herself. In such weather the old man would never follow her. For herself, she feared no wind that blew.

At dawn she stole out of the teepee without arousing anybody, and set forth down the river in her dugout alone.

THE camp at Nine-Mile Point was suffering from an attack of nerves. A party of strong men, suddenly condemned in the heat of their labours to complete inaction, had become a burden to themselves and to each other.

Being new to the silent North, they had yet to learn the virtue of filling the long days with small, self-imposed tasks. They had no resources, excepting a couple of dog-eared magazines—of which they knew every word by heart, even to the advertisements—and a pack of cards. There was no zest in the cards, because all their cash had been put into a common fund at the start of the expedition, and they had nothing to wager.

It was ten o'clock at night, and they were loafing indoors. Above the high tops of the pines the sky was still bright, but it was night in the cabin. They were lighted by the fire and by a stable lamp on the table. They had gradually fallen into the habit of lying abed late, and consequently they could not sleep before midnight. These evening hours were the hardest of all to put in.

Big Jack Skinner, the oldest and most philosophic of the party—a lean, sandy-haired giant—sat in a rocking chair he had contrived from a barrel and stared into the fire with a sullen composure.

Husky Marr and Black Shand Fraser were playing pinocle at the table, bickering over the game like a pair of ill-conditioned schoolboys.

On the bed sprawled young Joe Hagland, listlessly turning the pages of the exhausted magazine. The only contented figure was that of Sam Gladding, the cook, a boyish figure sleeping peacefully on the floor in the corner. He had to get up early.

It was a typical Northern interior: log walls with caked mud in the interstices, a floor of split poles, and roof of poles thatched with sods. Extensive repairs had been required to make it habitable.

The door was in the south wall, and you had to walk around the house to reach the lake shore. There was a little crooked window beside it, and another in the easterly wall. Opposite the door was a great fire-place made out of the round stones from the lake shore.

Of furniture, besides Jack's chair, there was only what they had found in the shack, a rough, home-made bed and a table. Two shared the bed, and the rest lay on the floor. They had some boxes for seats.

Something more than discontent ailed the four waking men. Deep in each pair of guarded eyes lurked a strange uneasiness. They were prone to start at mournful, unexpected sounds from the pine-tops, and to glance apprehensively toward the darker corners. Each man was carefully hiding these evidences of perturbation from his mates.

The game of pinocle was frequently halted for recriminations.

"You never give me credit for my royal," said Shand.

"I did."

"You didn't."

Husky snatched up the pencil in a passion. "Hell, I'll give it to you again!" he cried.

"That's a poor bluff!" sneered Shand.

Big Jack suddenly bestirred himself. "For God's sake, cut it out!" he snarled. "You hurt my ears! What in Sam Hill's the use of scrapping over a game for fun?"

"That's what I say," said Shand. "A man that'll cheat for nothing ain't worth the powder and shot to blow him to hell!"

"Ah-h! What's the matter with you?" retorted Husky. "I only made a mistake scoring. Anybody's liable to make a mistake. If it was a real game I'd be more careful like."

"You're dead right you would," said Black Shand grimly. "You'd get daylight let through you for less."

"Well, you wouldn't do it!" snarled Husky.

Shand rose. "Go on and play by yourself," he snarled disgustedly. "Solitaire is more your style. Idiot's delight. If you catch yourself cheating yourself, you can shoot yourself for what I care!"

"Well, I can have a peaceful game, anyhow," Husky called after him, smiling complacently at getting the last word.

He forthwith dealt the cards for solitaire. Husky was a burly, red-faced, red-haired ex-brakeman, of a simple and conceited character. He was much given to childish stratagems, and was subject to fits of childish passion. He possessed enormous physical strength without much staying power.

Black Shand carried his box to the fire and sat scowling into the flames. He was of a saturnine nature, in whom anger burned slow and deep. He was a man of few words. Half a head shorter than big Jack, he showed a greater breadth of shoulders. His arms hung down like an ape's.

"How far did you walk up the shore to-day?" big Jack asked.

"Matter of two miles."

"How's the ice melting?"

"Slow. It'll be a week before we can move on." Jack swore under his breath. "And this the 22nd of May!" he cried. "We ought to have been on our land by now and ploughing. We're like to lose the whole season.

"Ill luck has dogged us from the start," Jack went on. "Our calculations were all right. We started the right time. Any ordinary year we could have gone right through on the ice. But from the very day we left the landing we were in trouble. When we wasn't broke down we was looking for lost horses. When we wasn't held up by a blizzard we was half drowned in a thaw!

"To cap all, the ice went out two weeks ahead, and we had to change to wheels, and sink to the hubs in the land trails. Now, by gad, before the ice on the shore is melted, it'll be time for the lake to freeze over again!"

"No use grousing about it," muttered Shand.

Big Jack clamped his teeth on his pipe and fell silent. For a while there was no sound in the shack but Husky muttering over his game, the licking of the wood fire, and faint, mournful intimations down the chimney from the pines. The man on the bed shuddered involuntarily, and glanced at his mates to see if they had noticed it.

This one, Joe Hagland, was considerably younger than the other three. He was a heavy, muscular youth with curling black hair and comely features, albeit somewhat marked by wilfulness and self-indulgence.

Back in the world outside he had made a brief essay in the prize-ring, not without some success. He had been driven out, however, by an epithet spontaneously applied by the fraternity: "Crying Joe Hagland."

The trouble was, he could not control his emotions.

"For God's sake, say something!" he cried at the end of a long silence. "This is as cheerful as a funeral!"

"Speak a piece yourself if you feel the want of entertainment," retorted Jack, without looking around.

"I wish to God I'd never come up to this forsaken country!" muttered Joe. "I wish I was back this minute in a man's town, with lights shining and glasses banging on the bar!"

This came too close to their own thoughts. They angrily silenced him. Joe buried his face in his arms, and another silence succeeded.

It was broken by a new sound, a soft sound between a whisper and a hum. It might have come from the pine-trees, which had many strange voices, but it seemed to be right there in the room with them. It held a dreadful suggestion of a human voice.

It had an electrical effect on the four men. Each made believe he had heard nothing. Big Jack and Shand stared self-consciously into the fire. Husky's hands holding the cards shook, and his face changed colour. Joe lifted a livid white face, and his eyes rolled wildly. He clutched the blankets and bit his lip to keep from crying out.

They moved their seats and shuffled their feet to break their hideous silence. Joe began to chatter irrelevantly.

"A funeral, that's what it is! You're like a lot of damn mutes. Who's dead, anyhow? The Irish do it better. Whoop things up! For God's sake, Jack, dig up a bottle, and let's have one good hour!"

The other three turned to him, oddly grateful for the interruption. Big Jack made no move to get the suggested bottle, nor had Joe expected him to. The liquor was stored with the rest of the outfit in the stable. None desired to have the door opened at that moment.

Young Joe's shaking voice rattled on: "I could drink a quart myself without taking breath. Lord, this is enough to give a man a thirst! What would you give for an old-fashioned skate, boys? I'd welcome a few pink elephants, myself, after seeing nothing for days. What's the matter with you all? Are you hypnotized? For the love of Mike, start something!"

The pressure of dread was too great. The hurrying voice petered out, and the shack was silent again. Husky made a bluff of continuing his game. Jack and Shand stared into the fire. Joe lay listening, every muscle tense.

It came again, a sibilant sound, as if out of a throat through clenched teeth. It had a mocking ring. It was impossible to say whence it came. It filled the room.

Young Joe's nerves snapped. He leaped up with a shriek, and, springing across the room, fell beside Shand and clung to him.

"Did you hear it?" he cried. "It's out there! It's been following me! It's not human! Don't let it in!"

They were too much shaken themselves to laugh at his panic terror. Both men by the fire jumped up and turned around. Husky knocked over his box, and the cards scattered broadcast. He sidled towards the others, keeping his eyes on the door.

"Stop your yelling!" Shand hoarsely commanded.

"Did you hear it? Did you hear it?" Joe continued to cry.

"Yes, I heard it," growled Shand.

"Me, too," added the others.

Joe's rigid figure relaxed. "Thank God!" he moaned. "I thought it was inside my head."

"Listen!" commanded Jack.

They stood close together, all their late animosities forgotten in a common fear. There was nothing to be heard but the wind in the tree-tops.

"Maybe it was a beast or a bird—some kind of an owl," suggested Husky shakily.

"No; like a voice laughing," stammered Joe.

"Right at the door like—trying to get in," added Shand.

"Open the door!" said big Jack.

No one made a move, nor did he offer to himself.

As they listened they heard another sound, like a stick rattling against the logs outside.

"Oh, my God!" muttered Joe.

The others made no sound, but the colour slowly left their faces. They were strong men and stout-hearted in the presence of any visible danger. It was the supernatural element that turned their breasts to water.

Big Jack finally crept toward the door.

"Don't open it!" shrieked Joe.

"Shut up!" growled Jack.

They perceived that it was not his intention to open it. He dropped the bar in place. They breathed easier.

"Put out the light!" said Husky.

"Don't you do it!" cried Shand. "It's nothing that can shoot in!"

Their flesh crawled at the unholy suggestion his words conveyed.

They stood elbow to elbow, backs to the fire, waiting for more. For a long time all was quiet except the trees outside. They began to feel easier. Suddenly something dropped down the chimney behind them and smashed on the hearth, scattering the embers.

The four men leaped forward as one, with a common grunt of terror. Facing around, they saw that it was only a round stone such as the chimney was built of. But that it might have fallen naturally did not lessen the fresh shock to their demoralized nerves. Their teeth chattered. They stuck close together, with terrified and sheepish glances at each other.

"By God!" muttered Big Jack. "Ice or no ice, to-morrow we move on from here!"

"I never believed in—in nothing of the kind," growled Shand. "But this beats all!"

"We never should have stopped here," said Husky. "It looked bad—a deserted shack, with the roof in and all. Maybe the last man who lived here was mur—done away with!"

Young Joe was beyond speech. White-faced and trembling violently, the big fellow clung to Shand like a child.

"Oh, hell!" said Big Jack. "Nothing can happen to us if we stick together and keep the fire up!" His tone was less confident than the words.

"All the wood's outside," stammered Husky.

"Burn the furniture," suggested Big Jack.

Suiting the action to the words, he put his barrel-stave rocker on the embers. It blazed up generously, filling every corner of the shack with light, and giving them more confidence. There were no further untoward sounds.

Meanwhile the fifth man had been sleeping quietly in the corner. The one who goes to bed early in camp must needs learn to sleep through anything. The other men disregarded him.

The table and the boxes followed the chair on the fire. The four discussed what had happened in low tones.

"I noticed it first yesterday," said Big Jack.

"Me, too," added Husky. "What did you see?"

"Didn't see nothing." Jack glanced about him uneasily. "Don't know as it does any good to talk about it," he muttered.

"We got to know what to do," said Shand.

"Well, it was in the daytime, at that," Jack resumed. "I set a trap for skunks beside the trail over across the creek, and I went to see if I got anything. I was walkin' along not two hundred yards beyond the stable when something soft hit me on the back of the head. I was mad. I spun around to see who had done it. There wasn't nobody. I searched that piece of woods good. I'm sure there wasn't anybody there. At last I thought it was a trick of the senses like. Thought I was bilious maybe. Until I got the trap."

"What was it hit you?" asked Husky.

"I don't know. A lump of sod it felt like. I was too busy looking for who threw it to see."

"What about the trap?" asked Shand.

"I'm comin' to that. It was sprung, and there was a goose's quill stickin' in it. Now, I leave it to you if a wild goose ain't too smart to go in a trap. And if he did, he couldn't get a feather caught by the butt end, could he?"

They murmured in astonishment.

"Me," began Husky; "yesterday I was cuttin' wood for the fire a little way back in the bush, and I got het up and took off my sweater, the red one, and laid it on a log. I loaded up with an armful of wood and carried it to the pile outside the door here. I wasn't away two minutes, but when I went back to my axe the sweater was gone.

"I thought one of you fellows took it. Remember, I asked you? I looked for it near an hour. Then I came in to my dinner. We was all here together, and I was the first to get up from the table. Well, sir, when I went back to my axe, there was the sweater where I first left it. Can you beat it? It was so damn queer I didn't like to say nothing."

"What about you?" Jack asked of Shand.

Shand nodded. "To-day when I walked up the shore there was something funny. I had a notion I was followed all the way. Couldn't shake it. Half a dozen times I turned short and ran into the bush to look. Couldn't see nothing. Just the same I was sure. No noise, you understand, just pad, pad on the ground that stopped when I stopped."

"What do you know?" Jack asked in turn of Joe.

"W—wait till I tell you," stammered Joe. "It's been with me two days. I couldn't bring myself to speak of it—thought you'd only laugh. I saw it a couple of times, flitting through the bush like. Once it laughed——"

"What did it look like?" demanded Jack.

"Couldn't tell you; just a shadow. This morning I was shaving outside. Had my mirror hanging from a branch around by the shore. I was nervous account of this, and I cut myself. See, there's the mark. I come to the house to get a rag.

"You was all in plain sight—cookee inside, Jack and Husky sittin' at the door waitin' for breakfast, Shand in the stable. I could see him through the open door. He couldn't have got to the tree and back while I was in the house. When I got back my little mirror was hangin' there, but——"

"Well?" demanded big Jack.

"It was cracked clear across."

"Oh, my God, a broken mirror!" murmured Husky.

"I—I left it hanging," added Joe.

Meanwhile the chair, the table, and the boxes were quickly consumed, and the fire threatened to die down, leaving them in partial obscurity—an alarming prospect. The only other movable was the bed.

"What'll we do?" said Joe nervously. "We can't break it up without the axe, and that's outside."

Husky's eye, vainly searching the cabin, was caught by the sleeping figure in the corner.

"Send cookee out for wood," he said. "He hasn't heard nothing."

"Sure," cried Joe, brightening, "and if there's anything out there we'll find out on him."

"He'll see we've burned the stuff up," objected Shand, frowning.

"What of it?" asked Big Jack. "He's got to see when he wakes. 'Tain't none of his business, anyhow."

"Ho, Sam!" cried Husky.

The recumbent figure finally stirred and sat up, blinking. "What do you want?" Sam demanded crossly.

As soon as this young man opened his eyes it became evident that a new element had entered the situation. There was a subtle difference between the cook and his masters, easier to see than to define. There was no love lost on either side.

Clearly he was not one of them, nor had he any wish to be. Sam's eyes, full of sleep though they were, were yet guarded and wary. There was a suggestion of scorn behind the guard. He looked very much alone in the cabin—and unafraid.

He was as young as Joe, but lacked perhaps thirty pounds of the other youth's brawn. Yet Sam was no weakling either, but his slenderness was accentuated in that burly company.

His eyes were his outstanding feature. They were of a deep, bright blue. They were both resolute and prone to twinkle. His mouth, that unerring index, matched the eyes in suggesting a combination of cheerfulness and firmness. It was the kind of mouth able to remain closed at need. He had thick, light-brown hair, just escaping the stigma of red.

There was something about him—fair-haired, slender, and resolute—that excited kindness. There lay the difference between him and the other men.

"We want wood," said Husky arrogantly. "Go out and get it."

An honest indignation made the sleepy eyes strike fire. "Wood!" he cried. "What's the matter with you? It's just outside the door. What do you want to wake me for?"

"Ah!" snarled Husky. "You're the cook, ain't you? What do we hire you for?"

"You'd think you paid me wages to hear you," retorted Sam. "I get my grub, and I earn it."

"You do what you're told with less lip," said Husky threateningly.

At this point Big Jack, more diplomatic, considering that a quarrel might result in awkward disclosures, intervened. "Shut up!" he growled to Husky. To Sam he said conciliatingly: "You're right. Husky hadn't ought to have waked you. It was a bit of thoughtlessness. But now you're awake you might as well get the wood."

"Oh, all right," said Sam indifferently.

He threw off his blanket. As they all did, he slept in most of his clothes. He pulled on his moccasins. The other four watched him with ill-concealed excitement. The contrast between his sleepy indifference and their parted lips and anxious eyes was striking.

Sam was too sleepy and too irritated to observe at once that the table and chair were missing. He went to the door rubbing his eyes. He rattled the latch impatiently and swore under his breath. Perceiving the bar at last, he flung it back.

"Were you afraid of robbers up here?" he muttered scornfully.

"Close the door after you," commanded Jack.

Sam did so, and simultaneously the mask dropped from the faces of the men inside. They listened in strained attitudes with bated breath. They heard Sam go to the wood-pile, and counted each piece of wood as he dropped it with a click in his arm. When he returned they hastily resumed their careless expressions. Sam dropped the wood on the hearth.

"Better get another while you're at it," suggested Jack.

Sam, without comment, went back outdoors.

"Well," said Jack with a foolish look, "nothing doing, I guess."

"I thought there was nothing," boasted Husky.

"You——" began Jack indignantly. He was arrested by a gasp from Joe.

"My God! Listen!"

They heard a sharp, low cry of astonishment from Sam, and the armful of wood came clattering to the ground. They heard Sam run, but away from the cabin, not toward the door. Each caught his breath in suspense. They heard a thud on the ground, and a confused, scrambling sound. Then Sam's voice rose quick and clear.

"Boys, bring a light! Quick! Jack! Shand! Quick!"

The four wavered in horrible indecision. Each looked at the other, waiting for him to make a move. There was no terror in the cries, only a wild excitement.

Finally Big Jack, with an oath, snatched up the lantern and threw open the door. The others followed in the order of their courage. Joe bringing up the rear.

A hundred yards from the door the light revealed Sam struggling with something on the ground. What it was they could not see—something that panted and made sounds of rage.

"Boys! Here! Quick!" cried Sam.

To their amazement his voice was full of laughter. They hung back.

"What have you got?" cried Jack.

The answer was as startling as an explosion: "A girl!"

A swift reaction passed over the four. They sprang to his aid.

"Hold the light up!" Sam cried breathlessly. "Shand, grab her feet. I've got her arms locked. God! Bites like a cat! Carry her in." This ended in a peal of laughter.

Between them Shand and Sam carried her toward the door, staggering and laughing wildly. Their burden wriggled and plunged like a fish. They had all they could do, for she was both slippery and strong. They got her inside at last. The others crowded after, and they closed the door and barred it.

Sam, usually so quiet and wary in this company, was transformed by excitement. "Now, let's see what we've got!" he cried. "Put her feet down. Look out or she'll claw you!"

They set her on her feet and stood back on guard. But as soon as she was set free her resistance came to an end. She did not fly at either, but coolly turned her back and shook herself and smoothed her plumage like a ruffled bird. This unexpected docility surprised them afresh. They watched her warily.

"A woman!" they cried in amazed tones. "Where did she drop from?"

They instantly ascribed all the supernatural manifestations to this human cause. Everything was made clear, and a load of terror lifted from their breasts.

The suddenness of the reaction dizzied them a little. Each man blushed and frowned, remembering his late unmanly terrors. They were amazed, chagrined and tickled all at once.

Big Jack strode to her and held the lantern up to her face. "She's a beauty!" he cried.

A silence succeeded that word. Four of the five men present measured his mates with sidelong looks. Sam shrugged and, resuming his ordinary circumspect air, turned away.

THE girl turned an indifferent, walled face toward the fire, refusing to look at any of the men. Her beauty grew upon them momentarily. Their amazement knew no bounds that one like this should have been led to their door out of the night.

"Well," said Big Jack, breaking the silence at last. "It was a rough welcome we give you, miss. We thought you was a spook or something like that. But we're glad to see you."

She gave no sign of having heard him.

"Was it you whistled through the keyhole and tossed a stone down the chimney?" demanded Husky.

No answer was forthcoming.

"I'm sorry if we hurt you," added Jack.

He might as well have been addressing a wooden woman.

"I say, I'm sorry if we hurt you," he repeated louder.

"Maybe she can't understand English," suggested Sam.

"What'll I do then?" asked Jack hopelessly.

"Try her with sign language."

"Sure," said Jack. He looked around for the table. "Oh, hell, it's burnt up! We'll have to eat on the floor. Hey, look, sister!" He went through the motions of spreading a table and eating. The others watched interestedly. "Will you?" he asked.

She gravely nodded her head. A cheer went up from the circle.

"Hey, cookee!" cried Big Jack. "Toss up a bag of biscuits and put your coffee-pot on. You, Joe, chase out to the stable and fetch a box for her to sit on."

For the next few minutes the cabin presented a scene of great activity. Every man, with the tail of an eye on the guest, was anxious to contribute a share to the preparations. Husky went to the lake for water; Shand cut bacon and ground coffee for the cook; Big Jack produced a clean, or fairly clean, white blanket to serve for a tablecloth, and set the table.

A glitter in each man's eyes suggested that his hospitality was not entirely disinterested. They were inclined to bristle at each other. Clearly a dangerous amount of electricity was being stored within the little shack. Only Sam was as self-contained in his way as the girl in hers.

Big Jack continued his efforts to communicate with her. He was deluded by the idea that if he talked a kind of pidgin-English and shouted loud enough she must understand.

"Me, Big Jack," he explained; "him, Black Shand; him, Husky; him, Young Joe. You?" He pointed to her questioningly.

"Bela," she said.

It was the first word she had uttered. Her voice was like a strain of woods music. At the sound of it Sam looked up from his flour. He quickly dropped his eyes again.

When Joe brought her the box to sit on, he lingered beside her. Good-looking Young Joe was a boasted conqueror of the sex. The least able of them all to control his emotions, he was now doing the outrageously masculine. He strutted, posed, and smirked in a way highly offensive to the other men.

When, Bela sat down Joe put a hand on her shoulder. Instantly Big Jack's pale face flamed like an aurora.

"Keep your distance!" he barked. "Do you think the rest of us will stand for that?"

Joe retreated to the bed, crestfallen and snarling, and things smoothed down for the moment.

"Where do you live?" Jack asked the girl, illustrating with elaborate pantomime.

She merely shook her head. They might decide as they choose whether she did not understand or did not mean to tell.

Husky came in with a pail of water. The sanguine Husky was almost as visibly ardent as Joe. He rummaged in his bag at the far end of the cabin, and reappeared in the firelight bearing an orange silk handkerchief. His intention was unmistakable.

"You put that up, Husky!" came an angry voice from the bed. "If I've got to stay away from her, you've got to, too!"

Husky turned, snarling. "I guess this is mine, ain't it? I can give it away if I want."

"Not if I know!" cried Joe, springing toward him. They faced each other in the middle of the room with bared teeth.

Big Jack rose again. "Put it away, Husky," he commanded. "This is a free field and no favour. If you want to push yourself forward at our expense you got to settle with us first, see?"

The others loudly approved of this. Husky, disgruntled, thrust the handkerchief in his pocket.

After the two overweening spirits had been rebuked, matters in the shack went quietly for a while. The four men watched the girl, full of wonder; meanwhile each kept an eye on his mates.

It was their first experience at close range with a girl of the country, and they could not make her out at all. Her sole interest seemed to be upon the fire. This air of indifference at once provoked and baffled them. They could not reconcile it with the impish tricks she had played.

They could not understand a girl alone in a crowd of men betraying no self-consciousness. "Touch me at your peril," she seemed to say; but if that was the way she felt, what had she come for?

Sam brought his basin of flour to the hearth and, kneeling in the firelight, proceeded to mix the dough. After the manner of amateur cooks, he liberally plastered his hands and arms with the sticky mess.

The girl watched him with a scornful lip. Suddenly she dropped to her knees beside him, and without so much as "By your leave," took the basin out of his hands. She showed him how it ought to be done, flouring her hands so the batter would not stick, and tossing up the mess with the light, deft touch of long experience. At the sight of Sam's discomfiture a roar of laughter went up from the others.

"Guess you're out of a job now, cookee," said Shand.

"Now we'll have something to eat besides lead sinkers," added Joe.

Sam laughed with the others, and, retiring a little, watched how she did it. The girl affected him differently from the rest. Diffidence overcame him. He scarcely ever raised his eyes to her face.

All watched her delightedly, each man showing it according to his nature. In every move she was as graceful as a kitten or a filly, or anything young, natural, and unconscious of itself.

In a remarkably short space of time the three frying-pans were upended before the fire, each with its loaf. No need to ask if it was going to be good bread. It appeared that this wonderful girl had other recommendations beside her beauty.

She rose, dusting her hands, and backed away from the fire, as if to cool off. Before they realized what she was doing, she turned and quietly walked out of the door, closing it after her.

They cried out in dismay, and of one accord sprang up and made for the door. Sam involuntarily ran with the others, filled, like they were, with disappointment. It was now pitch dark under the trees, and straight from the fire as they were, they could not see a yard ahead.

They scattered, beating the woods, loudly calling her name and making naive promises to the night, if she would only come back. They collided with each other and, tripping over roots, measured their lengths on the ground.

Curses began to be mixed with their dulcet invitations to the vanished one to return. From the sounds, one would have been justified in thinking a part of bedlam had been let loose in the pine-woods.

Sam was the first to take sober second thought. He began to retrace his steps toward the cabin. Common sense told him she would never be caught by that noisy crew unless she wished to be. In any case, the bread might as well be saved.

In his heart he approved of her retreat. Trouble in the shack could not long have been averted if she had stayed. Perhaps she had been better aware of what was going on than she seemed. What a strange visitation it had been altogether! How beautiful she was, and how mysterious! Much too good for that lot. It pleased him to think that she was honest. He had not known what to think before.

Thus ruminating he came to the cabin door, and was pulled up short on the threshold by a fresh shock of astonishment. There she was, kneeling on the hearth as before!

She glanced indifferently at him over her shoulder and went on with her work. Such hardihood in face of all the noise outside did not seem human. Sam stared at her open-mouthed. She had some birds that she was skinning and cutting up. The pungent, appetizing smell of wild fowl greeted his nostrils.

"Well, I'll be damned!" he exclaimed involuntarily. "What does this mean?"

She disdained any answer.

"You were foolish not to beat it while you had the chance," he said, forgetting she was supposed not to understand. "This is no place for a woman!"

She glanced at him with a subtle smile; Sam flushed up. "Oh, very well!" he said hotly. Turning, he called outside: "Boys, come back! She's here!"

One by one they straggled in, grinning delightedly, if somewhat sheepishly. They shook their heads at each other. "We sure have a queer customer," was the general feeling. It was useless to bombard her with questions. The language of signs is a feeble means of communication when one side is intractable.

Apparently she had merely gone to some cache of her own to obtain a contribution toward the feast. She had brought half a dozen grouse. The biscuit-loaves were now done sufficiently to stand alone, and the pans were giving off delicious emanations of frying grouse and bacon.

The four men who, for the past week, had been sunk in utter boredom, naturally reacted to the other extreme of hilarity. Loud laughter filled the cabin. The potentialities for trouble were not, however, lessened. On the contrary, a look or a word was enough at any moment to bring a snarling pair face to face. Presently the inevitable suggestion was brought forth.

"This is goin' to be a regular party," cried Joe. "Jack, be a sport; get out a bottle, and let's do it in style!"

To save himself, Sam could not keep back the protest that sprang to his lips. "For God's sake!" he cried.

"What the hell is it to you, cook?" cried Joe furiously.

There was old bad blood between these two. Perhaps because they were of the same age.

Big Jack was bursar and commissary of the expedition. He smiled and gave his mouth a preliminary wipe. "Well, I think we might stand one bottle," he said.

Sam shrugged and held his tongue.

Jack returned with one of the precious bottles they had contrived to smuggle past the police at the Landing. He opened it with loving care, and the four partners had an appetizer.

When the food was ready, the always unexpected girl refused to sit with them around the blanket. No amount of urging could move her. She retired with her own plate to a place beside the fire.

Though she was the guest, she assumed the duty of hostess, watching their plates and keeping them filled. This was the first amenity she had shown them. They were perplexed to reconcile it with her scornful air.

Only once did she relax. Big Jack, jumping up to put a stick on the fire, did not mark where he set his plate. On his return he stepped in it. The others saw what was coming, and their laughter was ready.

Above the masculine guffaws rang a girlish peal like shaken bells. They looked at her, surprised and delighted. More than anything, the laughter humanized her. She hastily drew the mask over her face again, but they did not soon forget the sound of her laughter.

Big Jack kept control of the bottle, and doled it out with strict impartiality. Under the spur of the fiery spirit, their ardour and their joviality mounted together.

Sam was not offered the bottle. Sam was likewise tacitly excluded from the contest for the girl's favour. It did not occur to any of the four to be jealous of little Sam. He accepted the situation with equanimity. He had no desire to rival them. His feeling was that if that was the kind she wanted, there was nothing in it for him.

Like all primitive meals, it was over in a few minutes. Sam gathered up the dishes, while the other men filled their pipes and befogged the atmosphere with a fragrant cloud of smoke. Like all adventurers, they insisted on good tobacco.

The rapidly diminishing bottle was circulated from hand to hand, the hilarity sensibly increasing with each passage. Their enforced abstention of late made them more than usually susceptible. Their faces were flushed, and their eyes began to be a little bloodshot. They continually forgot that the girl could not speak English, and their facetious remarks to each other were in reality for her benefit. A rough respect for her still kept them within bounds.

Bela, as a matter of course, set to work on the hearth to help Sam clean up. This displeased Joe.

"Ah, let him do his work!" he cried. "You come here, and I'll sing to you."

His partners howled in derision. "Sing!" cried Husky. "You ain't got no more voice than a bull-bat!"

Joe turned on him furiously. "Well, at that, I ain't no fat, red-headed lobster!" he cried.

A violent wrangle resulted, into which Shand was presently drawn, making it a three-cornered affair. Big Jack, commanding them to be silent, made more noise than any. Pandemonium filled the shack. The instinctive knowledge that the first man to strike a blow would have to fight all three kept them apart. No man may keep any dignity in a tongue-lashing bout. Their flushed faces and rolling eyes were hideous in anger.

Through it all the amazing girl quietly went on washing dishes with Sam. He stole a glance of compassion at her.

Big Jack, having the loudest roar, battered the ears of the disputants until they were silenced. "You fools!" he cried. "Are you going to waste the night chewing the rag like a parcel of women?"

They looked at him sullenly. "Well, what are we going to do? That's what I'd like to know," said Shand.

A significant silence filled the cabin. The men scowled and looked on the floor. The same thought was in every mind. An impossible situation confronted them. How could any one hope to prevail against the other three.

"Look here, you men," said Jack at last. "I've got a scheme. I'm a good sport. Have you got the nerve to match me?"

"What are you getting at?" demanded Husky.

Jack put his hand in his pocket. "I'm gettin' at a weddin'. Why not? Here's as pretty a piece of goods, as I, for one, ever see or ever ask to. Handy, too, and the finest sort of prime A1 cook. Bride O.K. Four lovin', noble bachelors to choose the bridegroom out of. Bishop Lajeunesse'll be along to-morrow or the next day, or mighty soon. He's due to pass any minute. Priest all ready. Husband ready—leastwise I am for one. Bride all ready——"

"Damned if she is," contradicted Sam.

"Give her a chance and see," snarled Jack truculently. "She don't look no manner of a fool. It'll be a mighty fine thing for a girl of this blasted country to get a downright white husband, and I'll bet my bottom dollar this here girl's cute enough to see it—or—what the hell did she come to our shack for? And, if no such notion ever crossed her prutty head, I'll explain it to her clear enough—give me five minutes' chin with her——You all been complainin' it was so gol darn dull. Well, here's some excitement: a weddin' on the spry." He pulled his hand from his pocket and showed the dice in its palm. "This shack ain't big enough to hold the four of us men, not just at present," he said meaningly. "Three has got to get out for a bit, and leave one to do his courtin'—and do it quick. I've got a pair of dice here. Three rounds, see? The low man to drop out on each round. The winner to keep the shack, and to pop the question—while the other three camp on the shore. What do you say to it?"

THE three stared at Big Jack in a dead silence while the underlying significance of his words sunk in. They began to breathe quickly. Sam, hearing the proposal, flushed with indignation. His heart swelled in his throat with apprehension for the girl. How could he make her understand what was going on? How could he help her? Would she thank him for helping her?

Shand was the first to speak. "Say, you fellows, it's some idea—what? And it'll be cheerfuller than a funeral. Yes," he muttered. "I'm on!"

"How about the cook?" demanded Husky thickly.

"Hell, he ain't in this game!" said Jack indifferently. "He goes outside with the losers."

"I'm damned if I'll stand for it!" cried Joe excitedly. "It's only a chance! It doesn't settle anything. The best man's got to win!"

"You fools!" growled Shand. "How will you settle it—with guns? Is it worth a triple killing?"

"With my bare fists!" said Joe boastfully.

"Are you man enough to take on the three of us, one after the other?" demanded Shand. "You've got to play fair in this. You take an equal chance with the rest of us, or we'll all jump on you."

Jack and Husky supported him in no uncertain terms. Joe subsided.

"It's agreed, then," said Jack.

Shand and Husky nodded.

"Let him come in, then, if he wants his chance," said Jack indifferently. "The losers will take care of him."

Joe made haste to join them. They squatted in a circle around the blanket. Under the strong excitement of the game, each nature revealed itself. Black Shand became as pale as paper, while Husky's face turned purple.

Young Joe's face was drawn by the strain, and his hand and tongue showed a disposition to tremble. Only Big Jack exhibited the perfect control of the born gambler. His steely blue eyes sparkled with a strange pleasure.

"Let me see them?" demanded Husky, reaching for the dice.

Jack laughed scornfully. "What's the matter with you? 'Tain't the first time you've played with them. There's only the one pair. We've all got to use them alike."

"Let me see them!" persisted Husky, showing his teeth. "It's my right!"

Jack shrugged, and the bone cubes were solemnly passed from hand to hand.

"You can't shoot on a mat," said Joe. Jerking the blanket from the floor, he tossed it behind him.

"Get something to shake them in," said Shand. "No palming wanted."

Husky reached behind him and took a cup from Sam.

A long wrangle followed as to who should throw first. They finally left it to the dice, and the choice fell on Joe. Shand was at his left hand; Husky faced him; Jack was at his right. They held their breath while the bones rattled in the cup. When they rolled out, their eyes burned holes in the floor.

"Ten!" cried Joe joyfully. "I'm all right! Beat that if you can!"

Sam, obliged to await the result without participating, was suffocating with suspense. When the cup passed to Shand he touched the girl. She looked at him inquiringly. None of the other four were paying the least attention to them then. Sam asked her with a sign if she understood the game. He had heard that the natives were inveterate gamblers.

She nodded. He then, by an unmistakable gesture, let her know that the stake they played for was—herself. Again she nodded coolly. Sam stared at her dumbfounded.

In her turn, she asked him with a glance of scorn why he was not in the game. Young Sam blushed and looked away. He was both abashed and angry. It was impossible for him to convey his feeling by signs.

Meanwhile Shand threw seven, and Joe rejoiced again. But when Husky, opposite him, got a beggarly three, the young man's triumph was outrageous. The evening had left an unsettled score between these two.

"You're done for, lobster!" he cried with intolerable laughter. "Take your blankets and go outside!"

A vein on Husky's forehead swelled. "You keep a civil tongue in your head, or I'll smash your face, anyhow," he muttered.

"You're not man enough, Braky!" taunted Joe.

"Well, I'll help him," said Shand suddenly.

"Me, too," added Jack. "Play the game like a man and keep your mouth shut!"

When the cup went to Jack, Sam caught the girl's eye again. He could not help trying once more. He looked significantly toward the door. While the four heads were bent over the floor she could easily have gained it. She slightly shook her head.

Sam ground his teeth and doggedly attended to the dishes. A surprising angry pain transfixed his breast. What did he care? he asked himself. Let her go! But the pain would not be assuaged by the anger. She was so beautiful!

While rage gnawed at Husky's vitals, and he tried not to show it, Big Jack shook the cup with cool confidence and tossed the dice on the floor. Strange if he could not beat three! The little cubes rolled, staggered, and came to a stop. For a second the four stared incredulously. A pair of ones!

An extraordinary change took place in Husky. He grunted and blinked. Suddenly he threw back his head and roared with laughter. Big Jack steeled himself, shrugged, and rose. Going to the fire-place, he tapped the ashes out of his pipe and prepared to fill it again.

"'Tain't for me to kick," he said coolly; "since I got it up!" Jack deserved better at the hands of fortune.

The cup passed to Joe again. He shook it interminably.

"Ah, shoot!" growled Shand.

Whereupon Joe put down the cup and prepared to engage in another snarling argument. Only a combined threat from the three to put him out of the game forced him to play. He got five, and suddenly became quiet and anxious.

Shand threw four, whereupon Joe's little soul rebounded in the air again. Husky got eight. Shand rose without a word and crossed the room to the door.

"Wait till the game is over," said Big Jack quietly. "We'll all go out together and save trouble."

Young Joe, once more in possession of the cup, was unable to get up sufficient nerve to make the fateful cast. He shook it as if he meant to wear a hole in the tin. He offered to let Husky shoot first, and when he refused tried to pick a quarrel with him.

Finally Big Jack drew out his watch. "Ten seconds," he said, "or you forfeit. Are you with me, Shand?"

"Sure!" muttered the other.

Joe, with a groan of nervous apprehension, made his cast. He got a ten. Another reaction took place in him.

"Let me see you beat that!" he cried offensively. "I'm all right!" He smirked at the girl.

Husky picked up the dice and with one hasty shake tossed them out. By this time he had had as much suspense as he could stand. His nervous cast sent the cubes flying wide. One turned up a five between them. The other rolled beyond Joe. They had to crawl on hands and knees to see it. Six black spots were revealed.

"Eleven!" roared Husky. "I win!"

Joe's self-control gave way altogether. Tears were in his voice. "Do it over!" he cried. "You got to do it over! It wasn't on the table! You never shook the cup! I won't stand for it!"

Husky, having won, blissfully calmed down. "Ah, you short sport," he contemptuously retorted, "you deserve to lose!"

Joe sprang up with a tearful oath. "I won't stand for it!" he cried. "I said I wouldn't stand by a throw of the dice. You've got to fight me!"

Big Jack, expecting something of the kind, intervened from one side, Shand from the other. Joe's arms were promptly pinned behind him. He struggled impotently, tears of rage coursing down his cheeks.

"You fool!" said Jack. "We told you we'd see fair play done. What can you do against the three of us? If he had lost we would have done the same for you. Go outside, or we'll drag you."

Joe finally submitted. They released him. Still muttering, he went out without looking back.

"Come on!" said Big Jack brusquely to Sam. "You are the contract."

Another and an unexpected mutiny awaited them here. Sam very promptly arose from among his tins and turned on Big Jack. He had become as pale as Shand, but his eyes were hot enough. His lips were compressed to a thin line.

"Yes, I heard it!" he cried. "And a rotten, cowardly frame-up I call it! We never lacked for hospitality from her people. And this is the way you repay it. With your mouth full of talk about fair play, too. You make me sick!"

For an instant they stared at him flabbergasted. For the masters to be bearded by a humble grub-rider was incredible. Husky, the one most concerned, was the first to recover himself. Flushing darkly, he took a step toward Sam with clenched fists.

"Shut up, you cook!" he harshly cried. "It's none of your put! You stick to dish-washing and let your betters alone, if you know what's good for you!"

Sam's pale cheeks flamed and paled again. Instead of falling back, he took another step toward Husky.

"You can't shout me down, you bully," he said quietly in his face. "You know I'm right. And you all know it."

Husky towered over the slight figure.

"Get out," he roared, "before I smash you!"

"Go ahead!" said Sam, without budging. "I'm not afraid of you!"

For the first time, the girl seemed really interested. Her nostrils were slightly distended. Her glance flew from face to face. There was a pregnant pause. Husky's great fist was raised. But not having struck on the instant, he could not strike at all. Under the blaze of the smaller man's eyes, his own glance finally bolted. He turned away with an assumption of facetiousness.

"Take him away," he said to his mates, "before I kill him."