RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

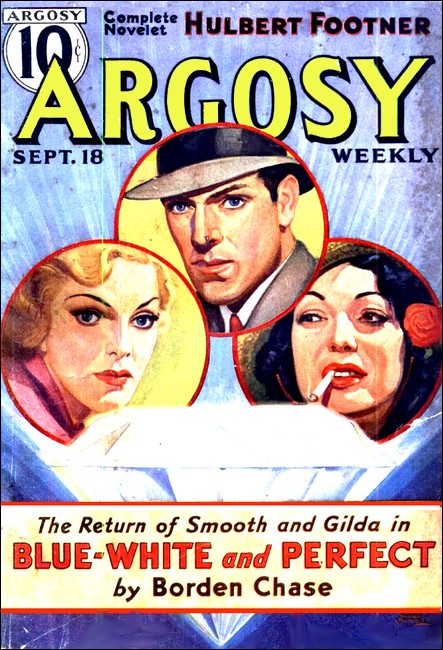

Argosy Weekly, 18 September 1937, with

"The Man in the Next Office"

WHEN I entered my office Patty, my little blond operator, was telling a story; Jewel was polishing her nails, her head bent and on her lips was that slight, withdrawn smile which suggests that she is listening to Beethoven's music inside her head, whereas, as a matter of fact, Irving Berlin is her line.

"Hi, Pop!" they called out, and Patty started her story all over for my benefit. Patty always shows you the tip of her red tongue when she begins a sentence; it makes her lisp.

"Pop, you were perfectly right about that playful pet who dated me last night. He was really pretty foul. I will never question your judgment of a man again. He was like a left-over éclair; looks all right on the outside, but sour when you bite."

"Where's Stella?" I asked.

The two girls exchanged a look. "She just stepped into Rufe's office," said Patty.

"Who the heck is Rufe?"

"The man in the next office."

"Rufus Penry, manager of the St. Nicholas Toy Company," added Jewel. "Haven't you noticed the lettering on the door?"

"How long has this been going on?" I asked, getting a little annoyed. "And what exactly is going on?"

Pat made a face. "Nothing. Nothing at all. Rufe just happens to be very nice and—and friendly. And he likes Stella. Quite a lot, I think. As a matter of fact, he's very nice. Probably even you'd like him."

Pat and Jewel were all right. Smart and quick and pretty shrewd, both of them, but Stella was the one I really counted on, and I didn't want her to go getting messed up with any collar-ad in the next-door office.

"I'm not paying her to put in her time down the hall," I said sharply, and wished 1 hadn't spoken. I've never been very good at barking, and I've always made a point of letting the girls do pretty much as they please. But it was one of those July broilers that generally makes me feel pretty mean. I was tired and uncomfortable. I wanted people to be around when I wanted them.

So I said some things I didn't really want to say, and Stella walked in right in the middle of them....

MY old friends on the force have, at one time or another,

given me a pretty stiff ribbing about opening up an

investigator's office with just three girls to help me. But

between the four of us we've had pretty good luck with cases that

have given my old plainclothes pals plenty of headaches. In the

five years we've been operating, we've eaten regularly, and

stalling the landlord for the rent is something we haven't done

much of.

As a matter of fact the girls are about twice as dependable as any men I could have hired. I'm not, for instance, always having to have them pulled out of speakeasies and stuck under cold showers before I can get them on the job. They don't lose their dough on the gee-gees nor blab everything they know about a case to some doll-faced gal who turns out to be the guilty party's girl friend. No, sir. You can take all the men operatives in town and dump them into the East River—I'll stick to my girls.

Patty's the youngest. Her uncle was a cop. Her father was a cop. She's got a brother on the Homicide Squad—and her sister's married to a desk-sergeant in Brooklyn. She's small and pert and pretty fresh and at least twice as smart as any flatfoot in town.

Jewel came to New York originally to study law. After she passed her bar exams, she tried to get a clerkship in a big commercial office. But the best she could do was a thirty-five-dollar-per job as a legal stenographer. Patty brought her to me about a year ago.

She's the one who smiles at you when you come through the door; the one who takes your name and makes up her mind whether I'm going to see you or not. And with her law experience, she can check and double-check any offside play the boy we're after might make, faster than he can yell for his attorney. Nope, I couldn't do without Jewel.

There's no sense trying to explain to you about Stella. She's only twenty-four but somewhere in those twenty-four years she's found time to try her hand at almost everything. She was an actress on the Coast for two years. She worked on a newspaper in Chicago. She was a waitress in a hash-house on Eighth Avenue and sang at a night club off Fifth. She speaks three languages, can spot me three strokes at golf and win by four, cooks spaghetti indienne better than Tony ever did, rides like an angel and drives like a fiend, and handles herself in a jam as coolly and as smartly as any man I've ever met.

That's telling you what she can do—but it isn't even giving you the smallest idea what she's like. She's tall and slender without being what they call willowy. She's got the poise of a princess and the good-natured charm of a child. She wears warm browns a good deal, to match her eyes and hair, and when she smiles it makes you feel as fine as you do just after the first, perfect puff of good tobacco in a friendly pipe.

No, I'm not maudlin about Stella. I'm just trying to tell you calmly. And I don't need her any more than I do my right arm. Not that there's ever been anything sloppy between Stella and me. In fact, until that day, she'd never seemed to be particularly interested in men, even if nine out of every ten were more than particularly interested in her.

I guess maybe I began to be afraid I was going to lose her. Seeing the glance Patty and Jewel had exchanged—amused, sympathetic and interested the way women get when another woman has fallen in love—had scared me. Anyway, as I say, I was jawing away like the middle-aged chump that I am when Stella came in through the door. I didn't see her right away, so I don't know what she heard.

THE other girls sent her warning glances but she blurted out,

"Pop, something has happened. The police have come looking for

Rufe—I mean Mr. Penry. You must help him, Pop."

"Yeah!" said I.

They all started yelling at once. Finally I got them more or less under control, and Stella told me what happened. She'd been in the outer office next door when the police had come in asking for Penry. Without waiting to find out what was up, she had slipped out to get me. I could see how upset she must have been, because I'd never known her to lose her head before.

While she was talking, a shadow darkened the windowsill and we all turned around. There he stood on the ledge outside. My offices, in case you didn't know, are in the Waltham Building on the twenty-first floor.

All three girls gasped and froze where they stood. The man seemed to be clinging to the frame by his fingernails. He grinned, and letting go with one hand, tapped on the glass.

"Oh, Rufe!" Stella whispered.

I crossed the room and raised the lower sash very gingerly in order not to shake him off. He caught hold of the frame with a sinewy hand and jumped in.

"Thanks," he said. "Sorry to intrude. I just had some unwelcome callers in my office... so I stepped across."

The girls laughed shakily. But the whole fool stunt made me sore. Not that there was anything wrong with Penry. I would have liked him myself, but he was just a little too sure of my girls. And much too good-looking.

"You can go out this way," I said, pointing to the entrance door.

"No!" said Stella quickly. "One of them is watching in the corridor."

Penry started back for the open window. Stella's hand fluttered out. "Rufe—please!"

He stuck his head out. "I suppose the next two windows belong to your private office, Mr. Enderby. If I could only get around the corner of the court I could go through the room that opens on the side corridor. There's a fire exit at the end of it."

"What's the use?" said Stella.

"I'm at the peak of my year's business," said Penry. "I've got eight important appointments today. I've no time to fool with the police."

"There's a door into the side corridor from my private office," I said stiffly. I wished something would make a little sense.

"Swell!" said Penry. "I'd like to have a word with you before I go. Look," he went on to Patty, "if the flatfoot should take it into his head to look in here while I'm talking to your boss, just shove that book off on the floor, will you?"

"Surely, Mr. Penry."

"Rufe to you, darling. It's a good thing to protect you from the weather."

At the door of the private office he paused to look back at the girls. He was dark and young, with fine shoulders and a sweep of straight black hair across his forehead. A gleaming smile glistened on has dark face. He took it for granted that everybody liked him. He said to me: "Enderby, I've got to hand it to you! With the demand for beauty what it is, how in blazes did you manage to cop three such winners? Three of them!"

"It's a sort of gift," I said. "Come in."

Once inside, he came direct to the point. "You're a detective Mr. Enderby."

"I prefer to be called a confidential investigator."

"Right! Well this is confidential."

"What are you wanted for?"

He produced his cigarette case. "Murder."

"That all?"

IT rolled off without even touching him. "Most men in my

situation would run to a lawyer," he said. "I don't want a

lawyer. I want somebody to stall off the police for me. Until

this mess gets straightened out."

"Who—whom—are you accused of murdering?"

"They don't know it, but it's Matthew Sleasby. They have come to get me to identify the body. He was found floating in the Buttermilk Channel with a bullet in his skull."

"Well, why don't you identify him and have done with it?"

"Because the trail would lead straight to me. I profit by his death, see? He had a stranglehold on my business; held all my stock in escrow. His death automatically releases it. And I'm a free man." He flung up his arms. "Free!"

"Did you kill him?" I asked.

He bared his white teeth in that gleaming smile. "Do I have to commit myself one way or the other?"

"Naturally."

"I don't see why. I wouldn't have to tell a lawyer. A lawyer would work to get me off just the same whether I was innocent or guilty."

"That may be," I said nettled, "but I'm not a lawyer. And I'm pretty particular."

"Good!" he cried. "Then you're the man for me."

"What do you want me to do? Pin the murder on somebody else?"

"No!" he said waving his hands. "This Sleasby was a number one so-and-so, you understand—a skunk, a swine of the purest water. Whoever bumped him off was a public benefactor."

The conference—if you can call it that—was cut short by the slap of a book on the floor in the outer office. Penry made swift tracks for the side door. The key was in it. As he went out he said:

"Sleasby's death releases the profits of my business. I can pay you your fee. I'll call you up."

As I locked the door after him I reflected that he had not told me whether or not he had killed Sleasby. I dropped the key in the bottom drawer of my desk.

A plainclothesman stuck his head in the other door and looked around the room. "Beg pardon for disturbing you, Mr. Enderby. Orders are to look in every office on the floor for a man we want. It's Rufus Penry. Is he a friend of yours?"

"No," I said, honestly enough. I was pretty sick of Penry by then.

"Where does that door go to?"

"Opens on the side corridor. I don't use it. The key is somewhere in my desk."

"Don't trouble yourself, Mr. Enderby."

An hour later a messenger boy arrived bringing (a) a dozen American Beauty roses for Jewel, (b) a five pound box of Maillard's for Patty, and (c) a bottle of some French perfume for Stella. They told me that the translation of its silly label was Adieu to Wisdom. I thought it well named.

ABOUT nine that night, Penry turned up at my flat. He brought

a pocketful of good cigars and a bottle of fine scotch. Within

half an hour we were calling each other Ben and Rufe. He didn't

seem to irritate me so much when the girls were not around.

"Well, Ben," he said, "what have you done in the case?"

I pointed out that I had not yet taken it.

He grinned. "Anyhow, what have you found out?"

"Matthew Sleasby was a widower of fifty-five," I said. "He had no near relatives. Though reputed wealthy he lived in modest style—"

"Say he was as tight as a bale of hay and have done with it!"

"He lived in a snail cheap flat on East Fifty-fifth Street, alone except for an old woman-servant. Night before last, about seven-thirty, he was called to the phone. Immediately afterward he told his servant that he was going out. Didn't say where. Would be back in an hour, he told her.

"She didn't see him again, but did not worry, because he often went away for a day or two without telling her. He was last seen by a newsdealer walking east on Fifty-fifth Street near Second Avenue. At dawn this morning his body was discovered by a pilot of the Hamilton Avenue ferry. He had been shot in the back of the head by a bullet of thirty-two caliber which was found in his skull. In his pocket was a notebook with an entry reading: In case of accident notify Rufus Penry, and your address."

"Oh-oh!" said Penry; "So that was what brought the police to me! A grim little joke of Sleasby's!"

"The body has not yet been identified."

"It will be soon," he said gloomily. "As soon as it is, Sleasby's attorney will show the police the agreement between Sleasby and me. Then good-night!"

"Who is Sleasby's attorney?" I asked.

"Thomas Rekar, another chromium-plated crook."

"What was in the agreement?" I asked.

"Understand, I've been working for this toy company since I was a boy. Five years ago the boss died and the firm was forced into bankruptcy. I saw a big opportunity in it, but I was only twenty-one, I had no money. Matt Sleasby put up the necessary capital to reorganize the concern and drew up this agreement.

"It sounded all right. He took fifty-one percent of the capital stock and allotted forty-nine percent to me. My stock was to be placed in escrow until I had paid him for it in full. After that, I was permitted to buy Sleasby's stock if I could, until I acquired full control. The price of the stock to be based on the profits of the concern at the time of purchase.

"For five years I have been nailed to that damned agreement. We prospered from the start, but it did me no good. The more money we made, the more I had to pay Sleasby for the stock. His object was to milk the concern of every cent of profits, and at the same time delay the day when he would lose control. He and his dummy directors voted me down at every meeting.

"I haven't had much of a life these past five years, denying myself everything—good times, girls, spending—while I scraped together enough to pay off Sleasby. By January first I would have been a free man. Well, when Sleasby saw that he couldn't hang on any longer, what did he do? Opened negotiations to a big toy firm to sell out to them and give me the big laugh. And as he was still technically in control I couldn't do a darned thing to stop him. Whoever killed him certainly handed me a new deal on a platinum platter—"

"I know how you feel," I said; "but unfortunately—"

"Unfortunately, my story makes me an object of suspicion, eh?"

His grin made me sore. "Confound it, Penry, a charge of murder is no joke!"

"Are you telling me?" he said. "I'm just whistling in the dark—and boy, it's plenty dark." He smiled again, less jauntily.

I couldn't help but like the kid. And he really was worried. Dark fear had come to lodge in his eyes; his voice was edgy.

"What's to be done?" he asked calmly.

"According to the medicos," I said, "Sleasby was killed soon after he left his house. Can you establish an alibi for the time between—say, sever-thirty and nine-thirty last night?"

"Sure!" he said quickly. Then he hesitated, biting his lip. "I took a girl out to dinner in a restaurant," he went on more slowly. "Mary Douglas."

"Can you bring forward others to support her story?"

"Sure. The proprietor of the restaurant where we dined knows me."

"What restaurant?"

"I'll tell that later."

"Blast it! If you have a real alibi, all you've got to do is to tell it to the police and they'll quit bothering you."

"The police are not going to give up as easy as that. They'd try to shake my witnesses—No, they're not going to let go of me until they find another stooge."

"It doesn't matter, if the stories of your witnesses stand up in court."

"Sure!" he agreed. "But what am I going to do until my case comes up? Sit and twiddle my thumbs in a cell and see my business go to smash? All the toy-buyers in the country are in town to stock up for Christmas."

"That's just silly," I said. "Do you think you can dodge the police and carry on your business at the same time?"

"Not indefinitely," he said, grinning, "but within two or three days I expect you to clear me."

"I'll have nothing to do with it," I said, "unless you take me into your confidence!"

He got up. "Sorry," he said. "I like you, Ben."

I was sorry myself then that I had spoken so quickly. I tried once more. "Tell me plainly as man to man, did you kill Matthew Sleasby?"

"I decline to answer," he said, grinning still, but the grin was not so brash. It conveyed some feeling that I could not analyze. "Good night, old fellow," he went on. "I still have hopes of winning you over."

I WENT to bed in a very bad temper. I had no more than got to

sleep when I was awakened by the ringing of the telephone at my

bedside. It was about two o'clock. I heard Rufe's cheerful voice

over the wire and silently cursed him.

"Oh, Ben," he said, "I just thought of something that I thought I ought to pass on to you at once."

"Is that so?" I said. "I hate to cast suspicion on anybody else," he went on, his voice sharp with irony. "But I am forced to do it in self-defense. Take down this name, Ben. Fred Wiser. Got that? W-I-S-E-R. Works as a salesman for the Manhattan Novelty Co., Five Hundred and Ninety-one Broadway. Lives at Eighteen Locust Street, Leonia, New Jersey. I have a photograph of him. I'm mailing it to you now.

"Listen, Ben. Matt Sleasby has been on the outs with this Wiser for a long time back. Can't tell you what first started it. I heard that Sleasby bought up a first mortgage and a second mortgage on Wiser's house in Leonia. Also a chattel mortgage on his furniture. The interest seems to have been paid up—or most of it.

"Sleasby allowed the due dates of the mortgages to pass without saying anything. Last week he presented a demand for immediate repayment under threat of foreclosure. Wiser has no money and the property has depreciated in value since the mortgages were given. He couldn't possibly renew elsewhere. So I reckon he had even more reason to liquidate Sleasby than I had, eh, what?"

Rufe's laugh was too much for my temper. "Go to the devil!" I said, shouting into the receiver. "And why couldn't you tell me that when you were here?"

Laughter gurgled into my ear. Rufe Penry's tone was the serene, sweetly reasonable twelve-year-old placating a scolding parent. "I thought," he said, "that you were mad at me." And hung up.

I OVERSLEPT myself next morning, and awoke unrefreshed. What I found when I arrived at the office—half an hour late—did not improve my temper. An air of suppressed excitement; Patty tapping the typewriter with unusual industry; Jewel filing away the accumulated correspondence; and Stella's desk—empty again.

"Rufe called Stella up half an hour ago," Patty began chirping before I was well inside the door. "Said he had a bookkeeper and a stenographer but neither of them could sell a bill of goods if their lives depended on it. So he asked Stella to go in and take care of the customers until he could make other arrangements. He said he would keep in touch with her by phone. The bookkeeper would furnish her with all prices and discounts."

I was so sore that I turned around without waiting to tale off my hat and overcoat, and hit out for next door. Rufe's office was similar to my own outer room—a rail inside the door, and beyond it a bookkeeper working at a high desk, and a homely stenographer at a low one. Knowing Penry as I did, her homeliness surprised me. In the center of the office sat a plainclothes man with a distinctly sour expression. It was not a man that I knew. The door of Penry's private office was on the right.

The showroom was in a long L to the left, lined all around with shelves and showcases displaying toys of every description. Dolls, tops, fire engines, airplanes, bears—everything. Here I saw Stella active as if she had been in toys for years. She had two buyers on a string, and both of them had more eyes for her than for the toys. Stella had two pads in her hand and was entering their orders first on one pad then on the other as she led them around.

The bookkeeper came to the rail to greet me. He was skinny and flat-chested with carroty hair and wispish sideburns; red-rimmed eyes and an expression as meek and gentle as a dying sheep. His name was Bryan but I learned later that everybody called him Joe.

"Good morning," he said, "what can I do for you?"

"I want to speak to Miss Deane—when she is free."

He missed my sarcasm completely.

"Yes, sir. What name, please?"

"Enderby. From next door."

The bookkeeper paled. "Yes, sir. Yes, sir," he stammered. "Mr. Enderby, would you mind—if you please—making out that you are a customer. You see—this man behind me is a police officer."

"So I see," I said.

He raised his voice for the benefit of the plainclothes man. "Yes, sir. Certainly, sir. Will you have a seat or would you prefer to look around at the stock while you're waiting?"

He leaned toward me. "Mr. Enderby," he whispered. "Excuse me, but is there any news? Have you found out anything? You see—we're all so attached to Mr. Penry. This means everything to me, Mr. Enderby. What has happened? Is Mr. Penry in danger?"

He was a pathetic object, but I was too burned to bother about him then. "There is no news," I said.

He went back to his desk.

THE telephone rang. Flatfoot made a move toward it, but the

stenographer beat him to it. "Miss Deane, you're wanted," she

said. Stella excused herself and came into the room. Passing me

she said sweetly: "I'll be with you in just a minute, sir." Lord!

but women can be exasperating.

As soon as she picked up the receiver I knew from her expression that it was Penry on the line. The plainclothes man knew it, too, and scowled.

"Yes?" said Stella. "Oh yes. Just a minute." She drew pencil and pad towards her and proceeded to take down his instructions. Afterward she said: "Mr. Rugose and Mr. Pine are in the showroom now. I'm taking care of them."

The plainclothes man could stand it no longer. "Here. Let me talk to him, sister."

Stella was not at all intimidated. "Just a minute," she said, waving him back. She continued to Penry; "Mr. Ploughman telephoned that he was at the Hotel McArthur, and Mr. Staples is at the Conradi-Windermere. Mr. Verney will arrive tomorrow. There's a gentleman here from Police Headquarters who would like to speak to you."

The plainclothes man snatched the instrument from her. "Say, looky here," he began roughly. Then a blank expression came over his face. "Damn! He hung up on me!" he muttered, smashing down the receiver. "Where was he phoning from?"

"Oh, were you cut off?" she said sweetly. "He called from the Vandermeer."

He banged out through the door, and Stella gravely winked at me.

She went back to her customers. When she had their orders signed, she disengaged herself smoothly and had eased them out the door before they knew what was happening to them. Then she came back to me, looking so contrite that I couldn't stay sore.

"Oh, Pop, don't scold me."

All my anger evaporated like smoke. All I could do was puff out my cheeks and make a bluff at it.

"I'm truly sorry," she went on. "But how could I have done any differently, Pop? Rufe expected to consult you about it, but you were late this morning and his customers were already coming in. I had to help him, didn't I, Pop? It's what you'd have wanted me to do if you'd been here."

I made my eyes severe. "This attempt to stall off the police won't do Penry any good. If he goes to those hotels to meet his customers—"

She smiled. "Foolish," she murmured. "Those were not the right hotels. We fixed up a code for telephoning." She looked as pleased as Punch, and blew me a kiss with her fingertips.

When I got back to my office, Patty and Jewel rushed at me like bloodhounds. "What is happening, Pop?"—"What have you turned up?"—"Give me an assignment on the case, Pop. I'm caught up with my office work"—"Let us help!"

I gave in all along the line. "All right," I said. "I've got an assignment for Jewel. I want to get a line on a man called Fred Wiser. He works for the Manhattan Novelty Company, Five Hundred and Ninety-five Broadway, and his home address is Eighteen Locust Street, Leonia. Find out what you can about him. Fetch him into the office if you can, otherwise arrange for me to meet him some place."

Jewel had her hat and coat on and was gone before you could count ten.

I turned to Patty. "Sorry, child. Somebody's got to hang around here, and you're elected." She pouted. So I said: "Penry might call up," and she brightened, like quicksilver.

I HAD Fred Wiser's photograph from Rufe by then, and my idea

was to take it up to Matt Sleasby's place and show it to the

servant. In the picture, Wiser's face was sort of ratty. He was

dark, looked about forty. I'd been to Sleasby's old-fashioned

flat the afternoon before. It was on East Fifty-fifth Street near

Third.

The grim old female who was his servant nodded at me glumly and raised a hand to shove back a blowsy wisp of gray hair from her forehead. She did not ask me in.

"You again?" she said. Her mouth tightened.

"Have you heard anything from Mr. Sleasby?" I asked, staring right back at her.

"No," she muttered.

"I'm looking for information about a man who owes Mr. Sleasby money," I said. "This man." I showed her the photograph.

She snorted. "I know him. Name's Wiser. He was here to see Mr. Sleasby. Last time was a week ago come Thursday. They had a fight. Mr. Sleasby was awful mad—I could hear their voices just as plain. This fellow here wanted to beg Mr. Sleasby off from foreclosing. Said him and his wife would starve if Mr. Sleasby put them on the street."

"And what did Sleasby say?"

"He says it was nothing to him. Says the business was in his lawyer's hands."

"What then?"

She grinned and looked wise and ugly. "Why, I showed this fellow out. What else?"

"You told me Sleasby was called up on the phone just before he went out Monday evening," I suggested. "Who took the call?"

"Me. He was called up twice. The first time he wasn't home."

"Was it Wiser's voice?"

"I couldn't tell you, mister. He spoke sorta growling-like."

"Disguised, eh? Would you know the voice again?"

She shrugged. "Mebbe."

"Did Sleasby call him by name when he talked to him?"

"Nope."

"Well, go on."

"The other fellow must have said he had news because Mr. Sleasby says: 'Well spill it!' Then he listened and looked real pleased. 'Good!' says he. And then: 'Are you there now?' Then he says: 'I'll be there in ten minutes. Sure, I always carry a gun,' and hangs up."

THAT was all I could get out of her. And it didn't get me very

far. If the old woman's version of the telephone talk was

correct, it couldn't have been Wiser who had called Sleasby

up.

As I came out of the house I noticed, across the way, the side door of a saloon that fronted on Third Avenue. It struck me that if anybody had been trailing Sleasby that saloon would have made a swell observation post. I went over and showed Wiser's photograph to the barkeeper, who was a good-looking young Irishman with a forearm that could have felled an ox.

"Sure, I seen this guy before somewhere," he said. He called his boss out of the back room and they consulted over the picture. Finally the boss sad:

"This guy was in here two or three days ago. Three. Yep, that's right. I noticed him because he acted so funny. I was in the back room figuring up my accounts and he was sitting by the window."

"What time of day was this?" I asked.

"Well, he was here for more than an hour. From about quarter past six to half past seven, I guess. Made two beers last him out while he watched through the window. Then all of a sudden he went out and walked away from his beer. I watched him crossing the avenue. He was trailing a guy on the other side."

"What did the other guy look like?"

"Man of fifty, but slim-like. Dry, leathery kind of face and pale blue eyes."

That was Matt Sleasby, all right.

I had a direct lead now and I felt pretty good. I called up my office from a pay-station. Patty told me that Jewel had phoned in to report that Fred Wiser had been discharged by the novelty company ten days before and nothing had been heard from him since. Jewel was going on over to Leonia and would phone from there. I told Patty to get her number when she called up, and tell her to stand by the phone until I called her back.

I needed to know a lot more about Matt Sleasby before I could hope to solve his murder. So I thought I'd best drop in to see his lawyer, Thomas Rekar, while I waited for another report from Jewel.

THERE was nothing shabby or mean about Rekar's place. His

offices were in a good building on Fifth Avenue. There was heavy

mahogany furniture and thick-piled rugs all over the place. I

sent in my card and was admitted right away. I find that people

are generally pretty curious to find out what a detective wants

of them.

Rekar was a tall man. He was thin but flabby, too. He had a neat gray mustache and a soapy voice that set me against him from the start. "What can I do for you, Mr. Enderby?"

"I am looking for a man called Fred Wiser," I said.

A subtle change came over his face.

"Never heard of him," he said. "What made you think I had?" His pale eyes were brightly speculative.

"I am informed that he owes a sum of money on mortgages to your client, Matthew Sleasby."

"Why not go to Mr. Sleasby himself, then?"

"I have been to his house twice, in fact. He is away from home. His servant said the matter was in your hands."

He ran up his eyebrows. "What does she know about it?"

"She only said that she overheard Mr. Sleasby tell Wiser that the matter was in the hands of his lawyer."

"A routine matter, I presume," Rekar said carefully. "It would not be brought to my attention. No doubt my clerks are attending to it."

I thought he was lying. "Sure," I said. "Sure."

"But you must understand that I can give out no information without instructions from my client," he added. "Whom do you represent?"

"I'm not permitted to say. It's another party that Wiser owes money to."

"Oh, a bill-collector," he said.

"Wiser gives it as his excuse for not paying my client that Mr. Sleasby has been bearing on him pretty hard," I said.

Rekar leaned back and placed the tips of his finger together.

"That's a deliberate falsification," he said. "Many people believe that Sleasby is something of a"—he smiled—"a skinflint. That is not exactly the fact. Nobody knows Matt Sleasby better than I do, and I say to you that some day, Mr. Enderby, some day, when Matthew Sleasby is gone, the world will learn how truly generous he really was."

"You mean—his will?" I said, playing up. This would be a valuable piece of information if I could tease it out of him.

"I mean his will."

"Would it be indiscreet to ask—?"'

"It is indiscreet, and Matt would be angry if he knew I had divulged it. Still—under the circumstances I think I may tell you, Mr. Enderby. But it must not go any further. Matthew Sleasby is leaving his entire fortune to found homes for working-girls in several of our largest cities."

To save myself I couldn't help grinning. But I quickly flattened my smile. "That's pretty fine of him, all right."

From that point on we sat there telling each other how noble Sleasby was, and if Rekar had any idea that Sleasby had been dead for at least twenty-four hours, he was careful not to give himself away. And the only other bit of Information I could dig out of him—painlessly—was that Sleasby's will named him executor and trustee.

So I left him, putting two and two together, hopefully, and getting totals of three and five and eight—but never four.

WHEN I got to the office Stella came in to hear my story. She listened quietly, making no comment. When I had finished, Patty said breathlessly:

"Are you going to tell the police about Wiser?"

"Not yet," I said.

"But we know now that Fred Wiser did it!"

"All we know is that Wiser might have done it. We can't prove a thing. We don't even know where Sleasby was murdered. Judging from that telephone conversation, he started for some place he'd been to before."

"Yes," said Stella. "And he said, 'I'll be over.' That suggests that it was neither uptown nor downtown, but crosstown."

"Right. And he said he'd be there in ten minutes. Well, how far can a man walk in ten minutes? About two-thirds of a mile, if he's a brisk walker, and Sleasby was. We can narrow it down even further because he was seen by a newsdealer crossing Second Avenue. That would be two minutes later. And he was still heading east. If he had eight minutes to go, it could not be to any place in that block, consequently we have him at the corner of First Avenue and Fifty-fifth, four minutes after he had left home and with six minutes to go."

"Pop, you're smart," Patty put in.

"Sure." I grinned. "One of us should start from the corner of First Avenue and Fifty-fifth, and explore the territory that a man could cover in six minutes. Always keeping to the east of First Avenue, of course, because he wouldn't retrace his steps. There isn't so much ground to go over because there's only one block east of First, then the river."

"Let me do it, Pop," Patty begged. "It's my turn." I'd never seen the girls so anxious to work on a case before.

"All right," I said. "You can start out as soon as Jewel comes in."

Shortly after twelve o'clock Jewel called up from Leonia. "Pop," she said, "the Wisers have pulled a sneak."

"So," I said. "When?"

"About nine o'clock this morning, they locked up their house here and set off in a little old Chevvie that Wiser owned."

"Did you get the license number?"

"Sure. Got it from a garage that had made repairs on the car. According to the neighbors the Wisers were right up against it. They weren't very popular. Wiser was a sorehead. Always fighting with somebody. For some days past they have been telling people that they were going to Utica, New York, to live with Mrs. Wiser's sister until something turned up. I mooched around the house and found a window on the back porch that had been left unlocked. So I went in. The house was a mess.

"I found that they had left all their winter clothes hanging in the cupboards, including Wiser's heavy overcoat and a fur coat of Mrs. Wiser's—not a very good one, but wearable. So they weren't starting out for northern New York in October. Next I went through the waste paper and in a basket I found a crumpled-up circular issued by the Chamber of Commerce of Miami, Florida. I also found a scrap of paper with a mysterious row of figures on it. May not mean anything, but I kept it."

"Good work, Jewel," I said. "There's nothing further you can do out there. Come on in to the office."

"What are you going to do, Pop?"

"What d'ya think?" I barked. "I'm going after the Wisers."

YOU cannot drive south without passing through Baltimore. I

knew a guy on the Baltimore force so I called him up. After

describing the Wisers and their car, and giving him the license

number, I asked him to set a watch for them and to detain them if

they came along before I got there. Then I hustled over to the

Newark Airport and took the one o'clock plane for the South.

I got in Baltimore before three. According to my figuring it would take the Wisers, driving an old car, at least six hours to make it. I got in touch with my friend Sergeant Driggs, and we started out in a police car to relieve the man he had set to watch the Washington Boulevard.

It was too easy.

We hadn't been waiting beside the road more than quarter of an hour when the Wisers came bowling along, all unsuspecting. When we told them to pull up, Mrs. Wiser was shrill and indignant, but Wiser didn't say much, only smiled in a nasty way. His wife was all dolled up in sleazy finery, and plastered with rouge, lipstick and mascara. I took the wheel of Wiser's car and drove them back to the police station. Driggs followed in his car.

When we got to Driggs' office, Wiser turned on me with an ugly grin. "Well, what's it all about, mister?"

"Matt Sleasby," I said. "He's pretty dead. I think maybe you could tell us something about it."

"Have yourself another think, pal."

"You were seen watching his house from about six until seven-thirty three days ago. And when he came out you followed him. That was the night he was killed."

Wiser, still grinning, said: "Ain't it funny the way things happen? Sure I was watching his house. I wanted to make a touch. I didn't expect him to ease off on the foreclosure, but I thought he might be good for a ten-spot when he was putting me on the street."

"Did you get it?" I asked.

"I did not. Sleasby told me to go to blazes and I beat it."

"And where did you go from there?"

"I got a watertight alibi, mister," he answered. "I happened to think of a friend of mine who might give me a loan and I went right to his place. I took a taxi because I knew he was going out at eight o'clock. He lives on East Forty-second and I was there before quarter of eight. I would've had to be pretty sharp to kill Matt Sleasby in that short time, now wouldn't I? Where was he killed?"

"Never mind that," I said. "What's your friend's name?"

"Manny Harris. He's a lawyer, and he's got an office by Jefferson Market Police Court. You can call him up right now."

"Leaving that for the moment," I said, "if your hands are clean, why did you go to all the trouble of telling everybody you were going to upstate New York and then started out for Florida?"

Wiser began to laugh. "You certainly been fooled bad, mister! Say, it's a wow! Coming all the way to Baltimore just to get the ha-ha! I feel sorry for you, really I do, but I got to laugh!"

"Cut the comedy," I said sharply, "and answer my question."

"Listen," he said, "I'm broke, see? And my wife and me had to go up to Utica to live with her folks. That's what I wanted the ten bucks for. It wasn't no picnic for me, but I hadn't no choice. Well, last night, past one o'clock it was, there was a ring at the door and I says to my wife it must be Santy Claus, and she says we need him bad enough. So I goes down to let him in. And by golly, it was Santy Claus! Santy Claus in the person of Rufe Penry, the toy man!"

The skin of my face began to tighten.

"Rufe knew all about me and my trouble with Sleasby," Wiser went on, "because when I got fired I went to Rufe for a job but he didn't have any. So last night Rufe says to me: 'Fred, they say that Matt Sleasby has been killed. The cops have got me on the run,' he says, 'and I'm so darn busy at this season I just can't fool with them. Now,' he says, 'everybody knows about your trouble you had with Sleasby, and if you was to disappear, like, it would drag a red herring across the trail as they say, and I'd get a chance to turn around.'

"I says: 'How much is it worth to you, Rufe?' 'Five hundred smackers,' he says, so we shakes on it, and here I am. I'm darn sorry you run me down so quick. Don't seem like Rufe is getting value for his money." He went off into his ugly laughter again.

His story had a fatally convincing ring. I scowled.

"Call up Rufe Penry if you don't believe me," Wiser said. "It was part of our agreement that if the cops run me to earth he would square me."

I went into another room to telephone. I got somebody who said he was Manny Harris and he substantiated Wiser's alibi. Afterward, through Stella, I got Rufe on the wire, and Rufe, apologizing all over the place, said that Wiser's story was the McCoy. I swore at him for a while and hung up.

So there was nothing for me to do but let Wiser go. I was as sore as if I'd had a smack in the face. I got Driggs to telegraph the chief of police in Miami to ask him to keep the Wisers under surveillance. Partly because Wiser had my goat, and partly—well, you never can tell what's going to bob up in a murder case. Anyhow I couldn't think of anything else to do.

MY blood was hitting the high Fahrenheits. I was going to find

the murderer of Matt Sleasby if it was my last act on earth. I

don't have to tell you that Rufe Penry was still my favorite

candidate. They could have slapped him into the electric chair

right then and I wouldn't have lifted a finger. Except for the

girls. And my biggest job was to make them see the light.

When I got back to New York my office was closed, but there was a memo from Stella on my desk telling me to look in the safe. Unlocking it, I found a note:

Dear Pop:

We hope you will get back in time to have dinner with us. If you can make it by seven o'clock (we'll wait until half past) come to Forty-seventh Street, east of Broadway, and stand at the curb in front of the cigar store—for five minutes. Or you can walk slowly up and down if you're restless. Then cross the street and enter the building directly across the street. Climb four flights of stairs and go to the front suite on the right. Smith is the name on the door. Knock three—one—three, like this: --- - ---.

Stella.

These dime-novel precautions made me grin. But I went to Forty-seventh Street and obeyed directions. I knocked on "Smith's" door, and, after Patty had peeked out at me through a crack, the door flew open and the girls pulled me through.

They were all there, the girls, Rufe Penry, and Rufe's bookkeeper, Joe. The girls were getting dinner in a kitchenette off the living room while Rufe sat and made unhelpful suggestions. They all talked at once, got in each other's way, snatched things off the stove, burned their fingers, and in general acted more like village belles at a strawberry festival than the three girls I'd come to know and respect.

Rufe was sitting there grinning like the lord of all creation. Joe said little, but kept staring at Rufe with a kind of dumb admiration. Rufe was Joe's hero. In fact thinking Rufe Penry was a sort of cross between Alexander the Great and Clark Gable seemed to be a disease that was rapidly becoming an epidemic.

"Quite a hideout you have here, Penry," I said, sourly.

"Isn't it? Patty found it for me this afternoon. There aren't any doormen or elevator boys to give me away. There are people going in and out all night. It's as public as an aquarium."

"Just what you want," I said.

They put me at the head of the table, served me first and treated me like Napoleon entering Warsaw. It was Pop this, and Pop that, every face turned in my direction and there was loud laughter to applaud my feeblest cracks. I wasn't fooled by it. It just made me madder. I could see that there had been a general agreement to smooth the old man down. The real hero of our festive little love-feast was the black-haired lad who was wanted by the police.

It gave me a wrench to see the look that passed between Stella and Rufe as we were sitting down. I haven't forgotten what it is to be young. I hated to think how I was going to hurt her by taking the line I'd made up my mind to take. However, better for her to be hurt now than when it was too late. That's what I told myself, anyhow. But it wasn't going to be easy.

When we had finished eating Rufe got up to give a toast.

"Ladies," says he. "Ladies—and Joe. I give you Pop. Foursquare, true-blue, no-surrender Pop. You can tell he's a stout fella by the way he turns his toes out. And Pop is going to yank little Rufe right from the jaws of an unpleasantly public execution. I hope." And the damned young idiot grinned all over.

I got away before I'd bust out and tell Rufe off. He came to the door with me. "No hard feelings on account of what happened today, Pop?"

"None whatever," I said. "Leave Stella alone until this mess is cleared up, Penry. Or I'll take you apart. And don't pull any more fast ones."

"Look Pop, send me a bill for the time you have already put in on this case, will you?" he said. "And forget the darn thing."

"Going to be a martyr now, eh?"

His face darkened. "You don't like me," he said suddenly.

"Don't let it bother you. Everybody else does." I looked at him wearily. "Oh go lie down and gnaw a bone somewhere, won't you?"

His eyes had a funny light. "Okay, Pop," he said, swallowing hard.

WHEN I entered the office next morning Jewel and Patty were chattering like parakeets.

"Come on, girls, let's get to work," I said. "Patty, what about that assignment I gave you yesterday?"

The girls stared at me. "But—but Pop! Rufe told us that you had given up the case."

"He misunderstood me. I belong to the bulldog breed. I never let go." I'd had a night to think it over, and I was tired of being a sorehead. I had to settle this thing... one way or another.

"But Pop!..."

"Only two days ago you were keen enough to have me take it up," I said.

Womanlike, they ignored this. Jewel said cajolingly: "There's nothing in it for a man of your standing, Pop."

"I know darned well that there's nothing in it for me," I said. "Nothing but abuse. However, I'm going to see it through."

The two girls exchanged a look of understanding. Jewel got up and slipped through the door. They always called on Stella when they got in a jam.

"Well, what did you find out yesterday?" I said to Patty.

"Nothing," she answered.

"Patty, you've never lied to me before." I slammed a fist down on her desk. "What the hell's got into everybody around here?"

She began to weep.

"Cut it out," I said. "Let's have the situation understood. Two days ago Rufe engaged me to represent him on this case. Last night he fired me. I am now working on my own, and you're working for me, not for him!"

"How can you be so m-mean!" she wailed, glancing toward the door to see if Stella was coming.

"What did you find out yesterday?" I persisted.

"What did I find out?" she repeated, suddenly turning voluble. "I walked up one street and down another until my feet groaned. What did you expect me to find out? Did you expect some man to come up to me and say: 'I shot Matt Sleasby with my trusty thirty-two!' Or perhaps you thought there'd be a sign out on one of the buildings: 'Matt Sleasby shot here. Twenty-five cents to view the spot!'"

Jewel came back, bringing Stella. Patty went off into a driving rain of tears and I lost my temper.

"Look here," I shouted, "you do your work as well as any men, but I can carry on my business without cloudbursts, I—I'll fire the lot of you!"

Stella flushed. "I'm not crying, Pop." Her eyes were defiant. "You never get squalls from me."

She was right, but I was too mad to be fair. I didn't answer.

Stella turned on Patty then. "You're acting like a lunatic, Pat. And you're not helping Rufe, either. What has Rufe got to fear if he isn't guilty? And he isn't. The only way to get at the truth is to let it all come out."

Patty gave in. "Rufe's toy factory is on York Avenue. That's the street nearest the East River, and it's just six minutes walk from the corner of First Avenue and Fifty-fifth."

"And that would be a place of course where Matt Sleasby would often go," I said. "And if a message came from the factory it would arouse no suspicion in his mind."

Stella turned on me. "There's nothing conclusive in this, Pop."

"Oh certainly, not conclusive," I said. "It's just one more link in the chain."

"What links have you to connect Rufe with the crime?" she demanded.

"Three," I said, and counted them off on my fingers. "First: he had a powerful motive for putting Matt Sleasby out of the way. Second: no innocent man would be so keen to keep out of the hands of the police. Third: he went to any amount of trouble and expense yesterday to create a false scent."

Stella turned without a word and went back to the toy shop. I wanted to go after her and take it back. But I didn't.

BY pulling a wire or two, I got a young building-inspector

called Bracker to take me with him to visit Rufe Penry's factory.

York Avenue after masquerading for a few blocks as fashionable

Sutton Place, dips down a hill and resumes its own name. It runs

through a kind of No Man's Land with nondescript buildings, many

of them vacant, and various storage-yards. I could see that it

would be a lonely spot at night. It was none too reassuring in

broad daylight.

The toy factory had begun life as a stable or milk depot, but had been cleaned up and painted and furnished with a new red sign. It was not directly upon the river; there was a junk-yard between. It was primarily a warehouse.

There was a tumult of packing and shipping on the ground floor. The building-inspector introduced me to the foreman. This foreman was a keen young fellow named McClary who regarded me with truculent blue eyes. He had evidently been warned against me, but under the circumstances he couldn't do anything. Like everybody else who worked for Rufe, he was for the boss right or wrong.

The inspection was completed, and we went up to the second floor. The foreman tagged along. There were a couple of dozen girls at work here painting little porcelain figures with movable heads. The rear of the long loft was empty.

"You don't seem to be very busy," I said.

"All our manufacturing is completed for the season," the foreman said curtly. "This is a special order."

I found nothing to get excited about until I saw the little office boarded off in the front. Naturally Matt Sleasby, if he had come to the factory that night, would have headed for the office. I glanced in and saw a couple of plain chairs, an old safe, a battered desk. There was a woman scrubbing the floor, and I thought that was odd, since all attempts to keep the ancient floor clean had obviously been given up years ago.

"Why are they so keen to wash up this particular corner? I asked her.

"You can search me," she said. "It's twice this week they had me in to scrub it."

"You don't seem to be getting it very clean at that," I said. "What's this brown smear in front of the safe?"

"I been over it three times," she said, "but it won't come out."

The young foreman came up. "It's an old varnish stain," he said sullenly. Or blood. I thought.

WHEN Bracker had finished his so-called inspection we went out

in the backyard. I could see the foreman standing back inside the

building, watching me. The yard was a small one, about fifty by

fifty. A dilapidated wooden fence separated it from the junk-yard.

Examining the fence, I found a spot where two of the boards

had recently been wrenched off and nailed back on again with

new nails. Taking a line between this hole in the fence

and the back door, I was able to establish a faint wavering track

which showed in the soft spots. It was a heel-track—made by

the heels of a body. I could also make out, here and there, a

footprint of the man who had dragged it.

The inspector and I left. He went back to his office and I turned into the junkyard. For half a dollar I was given the run of the place, and by degrees I was able to piece out the sinister track from the hole in the fence across the yard to the river. More than this, I found a brown button by the fence which had been torn from a man's coat. Some shreds of material were clinging to it.

There was a tumbledown wharf at the water's edge. Sleasby's body had undoubtedly been dropped overboard here. The place where it had been recovered was about six miles away. If the tide was at the ebb, it would just about make it. I made a mental note to look up the tides.

Adjoining the junk-yard to the south was the shanty of a squatter who made his living by repairing and renting small boats. He was a battered hulk of a man and, I suspected, not above turning his hand to any shady job that came along.

"Have you had any experience in recovering objects lost in the river?" I asked him.

"Sure," he said with a grin. "It's part of my trade, mister."

"What I'm after is a gun," I said. "I figured that a man stood on the junkman's wharf Monday night and threw it in the river.

"If it's there, I'll find it," he said.

"I'll pay you for your time," I said, "and if you get the gun, there's a ten-dollar bonus. Keep your mouth shut."

"That's part of my trade too, mister," he said with a snag-toothed grin.

On my way downtown I stopped at the Morgue where Matt Sleasby's body was still being held for identification. I asked to be shown his clothes first, and I saw at once that the button in my pocket had been torn from the jacket of his coat. I was then shown the body on its slab—a lean, stringy figure with a hard, ugly face. Even in death he had no dignity. Nobody regretted him. He had done nothing but harm in his fifty-odd years of life.

"Do you know him, mister?" asked the attendant.

"Never saw him before," I said.

WHEN I got back to the office, the girls were peeved because I

wouldn't tell them what I was up to. We were all sore with each

other; all the good feeling of the office was gone, and I cursed

Matt Sleasby's memory—and Rufe Penry's presence.

By two o'clock the waterman was in my office with the gun. He kept it hidden from the girls until he was alone with me. It was a thirty-two automatic, made by one of the best firms. Only one bullet had been discharged from the magazine.

I started tracing the sale of the gun, and before I left the office I had full information. It had been sold two years before by a prominent sporting-goods store to Rufus Penry of One Hundred and Fifty Central Park South.

So there it was. I wondered at Rufe's foolishness in leaving so open a trail. But of course when he bought the gun he didn't know he was going to kill a man with it.

Now the only thing needed to complete my case was to prove that the bullet which had been taken from Matt Sleasby's skull had been discharged from this gun. The police had the bullet and I could not obtain it without putting my whole case in their hands. I still hesitated to do this. I decided first to test the alibi that Rufe had given me. He had told me that he took a girl called Mary Douglas to dinner on the night of the murder. There was a Mary Douglas in the phone book but it proved to be the wrong one. So I tried a little ruse. Rufe kept a servant at his apartment. I called up and asked to speak to Miss Douglas.

"Why, she doesn't live here," answered a surprised female voice.

"Miss Mary Douglas," I said. "Don't you know her?"

"I know the young lady, but she doesn't live here."

"Isn't this Central six-one four one o?"

"That's the number, but Miss Douglas lives at the Allingham."

I hung up grinning. After dinner, I drove to the Allingham hoping to catch the Douglas girl before she went out for the evening. I sent up my card and was promptly shown to her suite. She was pretty—trust Rufe Penry for that! A medium blonde with fine grey eyes. She was looking at my card wonderingly.

I said: "You are a friend of Rufus Penry's."

"Yes," she said. "What of it?"

"When did you see him last?" I asked.

"Why do you ask?" she parried. "Who are you, anyway?"

"You have my card," I said. "I must call your attention to the word 'confidential' upon it."

"I won't answer your questions," she said with spirit. "I don't have to."

"Of course if there's any reason why you shouldn't answer—"

"There's no reason! Rufe Penry is the finest chap I know! I had dinner with him Monday night."

"Where?"

"At a little restaurant called Charles à la Pomme Soufflée."

"At what time did he leave you?"

She flushed up. "I don't know. I won't answer any more of your questions!" she said angrily.

I tried a little bluff. "I'm sorry, but you must answer. If you want to know who I am, call up Police Headquarters."

It worked. "It was early when he left me," she stammered. "About a quarter to eight. He said he had to go back to his factory."

I got up. "Thank you," I said. "That's all."

"But please tell me what this is all about," she begged.

"I'm sorry, I'm not free to do so."

Before I got to the door the telephone rang. She picked up the instrument and I heard her exclaim: "Oh, Rufe!"

She was listening to some communication with growing dismay. "Oh Rufe! he's here now!" she cried. "And I have told him!" She dropped the instrument.

"Rufe's been terribly busy," I said.

She jumped up in anger. "Well, it's not going to do you any good!" she cried. "If you attempt to put me on the stand I'll lie out of it! I don't believe Rufe Penry has done anything wrong, and if he has I don't care!"

I bowed myself out. Certainly Rufe had a way with him! A regular card, that guy. Right then I'd have given my right arm up to the elbow to have had his neck between my fingers....

I DROVE home in a low state of mind. Inspector Lanman was a personal friend, and I felt it my duty to put him in possession of the facts. But my hands were reluctant to take down the receiver and I kept putting; it off from moment to moment. I have a three-room flat on University Place on the sixteenth floor. I was still pacing up and down when there was a ring at the bell. I went to the door and the three girls came tumbling in, all talking at once—or rather two of them were talking, for Stella was oddly quiet.

"Oh Pop, what have you done?—Have you notified the police yet?—You mustn't do it, Pop!—You are making a terrible mistake!—" And so on! And so on!

"Wait a minute! Wait a minute!" I protested. "One at a time!"

"Have you communicated with the police?" Stella asked sharply.

"Not yet," I said. "But I am about to do so."

She dropped in a chair as if her knees had suddenly given way under her. "Thank the Lord we're in time," she murmured.

This made me a little sore. "Let's have a long drink to cool our fevered blood," I said. "What'll it be, girls?"

Stella waved the glass aside.

"We have come to prevent you from making a terrible mistake," Stella said.

I looked them over with mixed feelings: all flushed and bright-eyed with excitement, they were a treat to a man's eyes—but I saw that I was in for a bad time. I prepared to be firm and unyielding.

"I'm delighted to see you," I said, "but your coming here cannot change me from the course I have decided on."

"Stop talking like Frank Merriwell's grandfather," Jewel snapped.

"What is the exact situation," Stella demanded.

"Listen!" I said. I told them how Rufe had lied to me about spending the fatal evening with Mary Douglas, when he had gone to the factory at quarter of eight; that Matt Sleasby had arrived there at about the same time; that a man had been shot in the factory and his body dragged across the yard and dropped in the river; that the button I had found was from Matt Sleasby's coat; and finally that he had been shot with Rufe Penry's gun which I now had.

They wouldn't believe it because they didn't want to believe it. My story was received with a storm of denials and counter-accusations—even from Stella. "Rufe didn't do it! Rufe didn't do it!"

"Wait a minute!" I said. "You, Stella, answer me. How do you know he didn't do it?"

"I just know, that's all," she said with her chin up.

I flung up my hands. "Well, I'm no clairvoyant," I snapped.

"I know Rufe didn't do it because he acts so strangely," said Patty.

"And how can you explain his strange actions except that he is guilty?" I asked.

"If Rufe had done it," Jewel said, "either he would say he had done it or he would say he hadn't done it."

BOTH the other girls seized on this as if it was the judgment

of a Solomon.

"That's as clear as mud," I said.

"Pop, all I ask of you," Stella said, "is not to act in a hurry. Rufe isn't going to run away—or he would have run away already. Give yourself forty-eight hours, and I know you'll discover the truth."

"Forty-eight hours of this and I'll go off my nut!" I said.

"Then drop it, Pop. Give us girls a free hand and we'll prove Rufe's innocence."

"I haven't a doubt of it," I said.

"Well, you needn't get nasty," said Patty.

"You'd better go, all of you," I said, "or we'll really quarrel."

"We'll go," said Stella quickly, "if you will promise not to take any action within forty-eight hours."

"I refuse!"

"Twenty-four hours."

"No!"

"Just give me time to get in touch with Rufe, Pop."

"That's just what I don't mean to let you do!"

"You talk about being reasonable!" she said with a breaking voice.

That drove me wild. I said: "What women can't understand is a man's sense of duty. It is my job to expose crime."

"Oh, goodness, don't mount that hobby horse," cried Patty.

At that I flew off the handle altogether. "Get out! Get out! Get out!" I shouted, waving my hands.

They only looked at me. Patty's and Jewel's faces were working like those of children about to cry, but Stella's was set and white.

"It's useless to try to reason with him," she said to Jewel. "Go and do what we agreed on."

Jewel ran into my bedroom.

"What's this?" I cried, starting after her.

Stella and Patty, making an unexpected rush, pushed me backward into an easy chair. Patty began to cry. I sat there staring at them with my mouth open. Then I began to laugh.

Jewel came out of the bedroom carrying the telephone. She had cut the wires. My laughter turned to swearing. Stella said:

"Did you get the keys too?"

Jewel nodded.

"Then put that down and come help us."

I jumped up in a fury but Stella and Jewel seized hold of me, and Patty pushed from behind. No man in the world was ever in such an humiliating position. I couldn't hit my girls. I could only push them off. But I could only push one off at a time, and when I turned to another, the first one grabbed me again. I planted my feet and was pushed along the floor like a balky mule.

All the while little Patty was crying: "I hate to do this, Pop! I hate to do it!" And Jewel with big tears running down her cheeks: "But you wouldn't listen to reason, Pop!"

This only made me madder. I was choking with rage.

Stella said to the others: "What are you bawling about? When you've got a thing to do, do it and shut up!"

We struck against the table and the whole darn thing crashed over carrying lamps, books, papers, ashtrays to the floor. I got behind a heavy chair, but they pushed the chair along with me. It caught on a rug, and the whole crowd of us went down in a heap on the floor. When I picked myself up they ran in on me like three terriers. All the time we were nearing the open door of the bedroom.

I tried to temporize. "Wait a minute, girls. You're doing something you'll be sorry for!"

They went on hauling and shoving.

I got a clutch on the edge of the door-frame and hung on, gritting my teeth. The girls let go of me suddenly, and moving back a little charged me like a battering ram. My hold broke and I went sprawling on the bedroom floor. The door slammed and the key turned.

I RAN into the bathroom. There was a door from the bathroom

into the kitchen. However, they had locked it and there I was, a

prisoner sixteen floors above the street. I ran to a window. But

I shrank from opening it and hollering for help. Suppose I did

succeed in bringing the police and the fire engines, what a

figure I'd cut! After all this was a private matter between the

girls and me.

I went back to the door through which I had been thrown. It was a heavy panel of mahogany that opened towards me. Putting my ear to the crack I could hear Patty crying outside, and Jewel's murmuring voice. Nothing from Stella, and I took it that she had slipped out to warn Rufe Penry. So they had got the best of me!

Presently I heard Patty on the other side of the door. "Pop, dear," she said, "are you all right: I hope we didn't hurt you."

I wouldn't answer her.

"Pop," she went on, "let the cold water run and put a wet compress on your bruises. It will take the sting out."

Not a sound from me.

"Pop! Answer me!"

From behind her I heard the calm voice of Jewel saying: "Ah, let him alone. He's only sore and you can't blame him."

I HEARD a ring of the bell and made haste to put an ear to the

crack again. It was Stella back. I heard Patty's and Jewel's

exclamations of relief upon seeing her. Then I got a surprise.

There was the rumble of a man's voice. I hardened. It would be a

satisfaction to have a man to deal with.

After a whispered consultation, the door was thrown open and Rufe stood there. "Gosh! I'm sorry for this, Pop!" he said.

I marched out ignoring the outstretched hand.

"I know how you feel," he went on. "The girls meant well but—" Suddenly his face broke up. He struggled against it, but laughter broke from him with a roar. He dropped in a chair laughing and gasping out: "I'm sorry, Pop—I'm sorry—but I can't help it!"

The girls were laughing, too, and holding their hands over their mouths—even Stella.

"I'm glad you think it's so funny," I said.

"Look in the glass, Pop!" said Patty.

I looked in the mirror but I couldn't see anything funny.

"Like a little turkey gobbler with his feathers all ruffled up!" cried Patty. "Oh, I'm sorry, Pop!"

I started for the door. If I wasn't safe from insult in my own house I could leave it. Rufe ran after me and drew me back.

"Ah, come back, Pop," he said. "We're all for you. Come back and let's talk things out as man to man."

"All right," I said. "Did you or did you not shoot Matt Sleasby?"

"I did not," he said, looking me square in the eye.

"Then why in blazes didn't you say so in the beginning?"

"I had my reasons," he said, "good ones, too."

Another evasion!

"What did happen?" I asked.

He hesitated. "In telling you this I am trusting you further than I ever expected to trust any man."

I shrugged impatiently.

"All right. I said I trusted you. First, about the gun. I bought it because our factory was in such an out of the way spot. So far as I know it was never out of the office safe."

"Who possesses the combination to the safe?" I asked.

"I have it; McClary my foreman has it; Bryan my bookkeeper has it; Matt Sleasby had it; and his attorney Rekar has it."

The girls were listening with sharp attention. They had tidied the room. Patty came over and smoothed down my ruffled hair.

"Now as to Matt Sleasby," Rufe went on. "I didn't call him up at any time last Monday. I had a perfectly legitimate reason for going to the factory that night. McClary had been after me to come and pass on a new figure we were starting to manufacture. I couldn't make it during the day, and I phoned him to leave the stuff out where I could see it.

"I took Mary Douglas home and drove on up to the factory. It was about eight o'clock. As I turned the corner I saw that there was a light on the stairs and another in the office above. I let myself in with my key. On the stairs I saw a gun. Not my gun. I left it there. When I entered the office I was aware of four things: the safe was open; my gun was gone; there was a splash of blood on the floor; a man's hat on the table. I looked inside the hat. It had Matt Sleasby's initials."

"Was there any money in the safe?" I asked.

"No, only on payday. Robbery had no part in this killing.... I could dope out what had happened. Sleasby was always snooping around, you understand, trying to get something on somebody. He had made so many men hate him that this was bound to happen sooner or later. I won't pretend that I was sorry.

"The blood was still wet, and with the hat and gun there and the lights burning, I guessed that the killer was still around. I went downstairs. The back door of the shipping room was standing open. While I watched it was darkened by the shadow of a man coming in. It occurred to me that I had better keep out of this, and I dropped behind a pile of boxes until he passed and went upstairs. I then let myself out of the building and beat it for home. Next morning the police came to my office to make inquiries. You know the rest."

I SAID: "The notebook found in the dead man's pocket was

described to me as being a new one. It had no other entries but

your name which was printed in block letters. It suggests that

the note-book was planted in the dead man's pocket by the

killer."

"That's not possible," said Rufe quietly.

This answer gave away more than he intended. I lit a cigar and studied. "Rufe, your story is true up to a point," I said.

"Where did you catch me lying?" he asked with a grin.

"Human beings have inherited a sense of curiosity from the monkeys," I said. "It is incredible that anybody could have let the killer pass him without peeping out to see who it was."

Rufe grinned and let it go at that

"Who was it, Rufe?" I asked softly.

"I will never tell you that," he said.

"Good grief, man! I can't cover up a murder!" I cried. "I've got to report this case. Consider the evidence there is against you. You'll have to stand trial and you may well be convicted."

"I have faced that out," he said. "I didn't kill the man."

"Ah, don't fool yourself!" I cried. "Many a man has been sent to the chair on less evidence than they will have against you!"

"I shall make a good witness for myself," said Rufe confidently.

Stella pleaded with him. "Think what it means, Rufe! Months of imprisonment followed by a trial that's bound to be sensational. Even if you are acquitted, it would ruin you."

He lowered his head. "Sure, it's a hard choice," he said in a low tone. "But I have no other. My mind is made up."

"Don't kid yourself with talk of an acquittal," I said. "This story about arriving on the scene a few minutes after the crime and seeing the shadow of the killer is the kind of story that a hard-pressed defendant always tells. It's typical."

A painful scene followed. The girls pleaded with Rufe, but he only set his mouth in a hard line and shook his head. It was maddening to see him bent on sacrificing himself.

In the middle of this the door bell rang. "Don't answer it!" said Rufe. "We don't want any outsider horning in.

"I'll get rid of them," I said. When I opened the door I saw Joe, Rufe's meek bookkeeper. I let him in. He stammered so that it was difficult to make out what he wanted. He had been working late at the office, it seemed, and a telegraphic order had came that he thought Rufe ought to see.

"How did you know I was here?" asked Rufe.

"I took it to the flat on Forty-seventh Street. McClary was there. He said Miss Deane had come to fetch you down to Mr. Enderby's."

Rufe gave him his instructions but he didn't go. Everybody is familiar with the spasms of boldness that shy people exhibit. "What were you talking about when I came in?" he asked suddenly.

"The National Debt," said Rufe. "Run along, Joe."

The little man's voice scaled up. "No! I want to know.... Is Mr. Enderby still trying to prove Rufe guilty of murder?"

"Don't be silly," said Rufe.

A hunch came to me that Caspar had used the telegram merely as an excuse to find out what was going on. "Unluckily I have proved my case," I said. "Rufe will have to stand trial!"

Rufe sprang up white with anger. "Damn it, Pop!"

The little bookkeeper smiled peculiarly and stroked the back of a chair. "You are on the wrong track, Mr. Enderby—"

"Don't say it! Don't say!" shouted Rufe.

Joe only raised his voice. "—I shot Matt Sleasby."

The girls cried out in amazement; a groan was forced from Rufe.

"I couldn't let you stand trial," Joe stammered.

"I've got a good thick skin," said Rufe, "I could take it. But you!" His voice broke. "They'll kill you!" He turned to me in bitterness. "Well, I hope you're satisfied, Pop."

"Joe knows all my business," Rufe went on presently, "and I suppose he brooded on what Sleasby was doing to me until something snapped in his brain and he did this thing. For me! How can I let him suffer for it?" He turned away to conceal his emotion. "Well, it's up to you, Pop."

I was floored. What could I do or say? It was one of those situations where every possible course of action seemed wrong.

Joe stood looking at me as if his life hung on my next words. I couldn't meet his piteous eyes. Rufe remained glum and silent. The girls began to plead with me in broken voices.

"Pop, you couldn't lay a charge against Joe! It would be like hurting a child! He did it for Rufe!"

"You all know that this is useless," I said. "I couldn't fall for hushing up a murder."

THERE was silence in my living room. Two of the girls were crying softly; Rufe was scowling and biting his lips; Joe sat with his chin on his breast awaiting his fate. As I thought over what had been said, a maggot began to stir in my brain. Had I after all got to the bottom of the case? I said to Joe:

"How did you decoy Sleasby over to the factory?"

"I didn't decoy him. I just happened to meet him there."

This confirmed my suspicions. Certainly somebody had decoyed Sleasby out of his house that night.

"Are you willing to tell me just what happened?" I asked.

Joe nodded. "I worked late at the office on Monday. A couple of things came in that I wanted to show Rufe. He had told me that he was going to the factory after supper, so I went up there with them. Mr. Sleasby was there. He suspected that Rufe was cooking the accounts. I hated him because I knew he was going to sell the company out and destroy everything that Rufe had built up since he was a boy.

"Mr. Sleasby started to question me, trying to trap me into something to Rufe's discredit. It was more than I could bear because Sleasby was the crook, not Rufe. Finally he offered to pay me if I would help him to 'get' Rufe." Joe began to tremble at the recollection. "At that I became a different person. It came to me that we were alone in that solitary factory and that the river was handy. I made believe to fall for his offer. When he turned his back I took the gun out of the safe and I shot him."

The little man had to stop for a moment until he could control himself. "I then got a rag and wrapped it around his head so that he wouldn't leave blood on the way and I—"

"Did you do this right away?" I interrupted.

"Oh yes! Quickly. Quickly. I was terrified of somebody coming."

There was a discrepancy here. A man bleeds but slowly after he is dead and there had been quite a lot of blood on the floor. I figured that Sleasby must have lain there for some minutes at least. "Go on," I said.

"I dragged him downstairs through the shipping-room, out the back door and across the yard...."

"Weren't you afraid?" I asked.

A shiver went through him. "I was sick with fear. But it had to be done. I pulled a couple of boards off the fence, dragged Sleasby, through, and dropped him off the wharf. I threw the gun into the water. I then went back to clean up the blood and get the hat. Sleasby's gun had fallen out of his pocket on the stairs. I didn't make a very good job of the floor. I got a hammer and nails and fixed the fence. Then I went home. I dropped Sleasby's gun in a sewer opening. I dropped pieces of the hat in different places."

As I mulled over this story, a gleam of light came into my mind. "Have you and Rufe talked this over?" I asked.

"Oh no!" he said quickly.

"You didn't know, did you? that when you came back from the river, Rufe was in the shipping room watching you."

"Oh no! Rufe wasn't there!"

"Rufe himself told us."

"I—I don't understand."

"And what's more, shortly before you came in Rufe looked me square in the eye and told me that he had not killed Sleasby."

"He said that—he said that—" Joe turned to Rufe with his hands clasped together. "Didn't you kill Sleasby?" he asked.

"Have you lost your wits?" said Rufe. "You have just told us that you killed him."

A wild cry broke from Joe. "Oh, thank heaven!" His mild eyes were blazing with joy. "I didn't kill him!" he screamed. "I would never have the nerve to fire a gun. I only said that because I thought Rufe had done it!"

WE looked at each other to see if we had heard right. Rufe

flung an arm around the thin shoulders. "Oh, you little fool!" he

cried, in a voice warm with feeling. "Did you think for a moment

that I would stand for that if I had done it?"

"You can't be spared," stammered Joe. "I'm nobody."

Let me pass lightly over the scene that followed. We laughed and cried; shook hands, clapped each other on the back, and otherwise comported ourselves as if we were demented with joy. Each of them assured me fifty times over that I had saved the works. Such was my revenge.

Finally I asked Joe to give us the real dope. He said: