RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

"Two on the Trail," Doubleday, Page & Co., New York, 1911

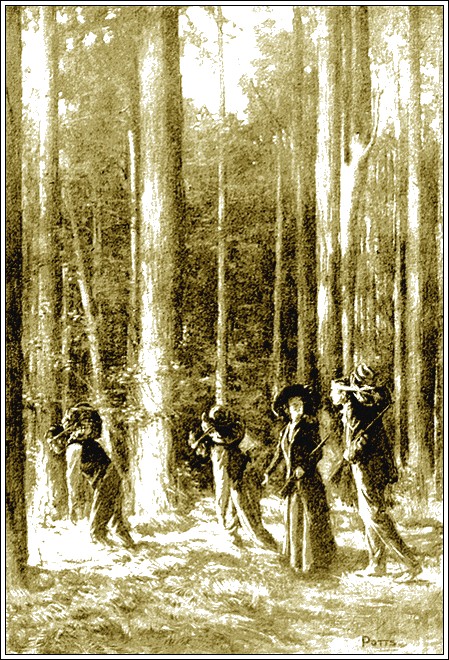

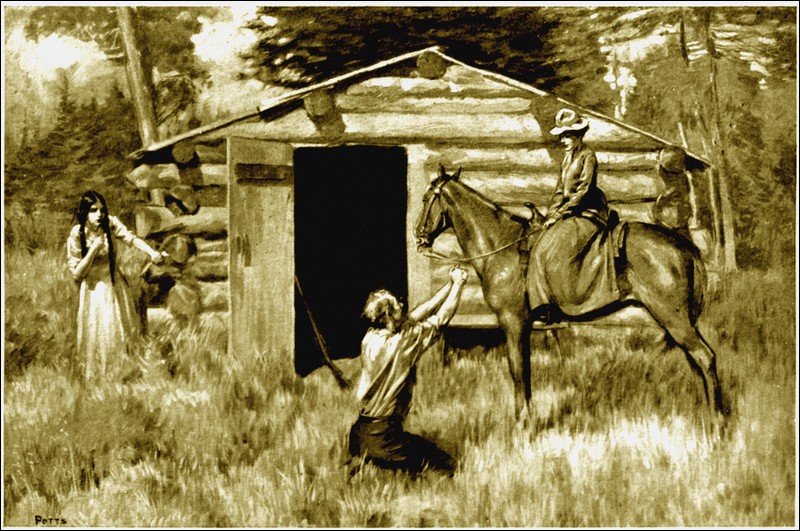

Frontispiece.

"Look!" she cried. "Isn't it like the frontispiece to a book of adventure!"

THE interior of Papps's, like most Western restaurants, was divided into a double row of little cabins with a passage between, each cabin having a swing door. Garth Pevensey found the place very full; and he was ushered into a cubby-hole which already contained two diners, a man and a woman nearing the end of their meal. They appeared to be incoming settlers of the better class—a farmer and his wife from across the line. Far from resenting Garth's intrusion, they visibly welcomed it; after all, there was something uncomfortably suggestive of a cell in those narrow cabins to which the light of day never penetrated.

Garth passed behind the farmer's chair, and seated himself next the wall. He had no sooner ordered his luncheon than the door was again opened, and the rotund Mr. Papps, with profuse apologies, introduced a fourth to their table. The vacant place, it appeared, was the very last remaining in his establishment.

The newcomer was a girl; young, slender and decidedly pretty: such was Garth's first impression. She came in without hesitation, and took the place opposite Garth with that serenely oblivious air so characteristic of the highly civilized young lady. Very trimly and quietly dressed, sufficiently well-bred to accept the situation as a matter of course. Thus Garth's further impressions. "What a girl to be meeting up in this corner of the world, and how I should like to know her!" he added in his mind. The maiden's bland aloofness was discouraging to this hope; nevertheless, his heart worked in an extra beat or two, as he considered the added relish his luncheon would have, garnished by occasional glances at such a delightful vis-à-vis. Meanwhile, he was careful to take his cue from her; his face, likewise, expressed a blank.

The farmer and his wife became very uncomfortable. Simple souls, they could not understand how a personable youth and a charming girl should sit opposite each other with such wooden faces. Their feeling was that at quarters so close extra sociability was demanded, and the utter lack of it caused them to move uneasily in their chairs, and gently perspire. They unconsciously hastened to finish, and having at length dutifully polished their plates, arose and left the cabin with audible sighs of relief.

This was a contingency Garth had not foreseen, and his heart jumped. At the same time he felt a little sorry for the girl. He wondered if she would consider it an act of delicacy if he fastened the door open with a chair. On second thoughts, he decided such a move would be open to misconstruction. Had he only known it, she was dying to laugh and, at the slightest twinkle in his eyes, would have gone off into a peal. Only Garth's severe gravity restrained her—and that in turn made her want to laugh harder than ever. But how was Garth to learn all that? Girls, more especially girls like this, were to him insolvable mysteries—like the heavenly constellations. Of course, there are those who pretend to have discovered their orbits, and have written books on the subject; but for him, he preferred simply to wonder and to admire.

Since her arrival the objective point of his desire shifted from his plate some three feet across the table; he now gazed covertly at her with more hunger than he evinced for his food. She had a good deal the aspect of a plucky boy, he thought; a direct, level gaze; a quick, sure turn to her head; and the fresh, bright lips of a boy. But that was no more than a pleasant fancy; in reality she was woman clear through. Eve lurked in the depths of her blue eyes, for all they hung out the colours of simple honesty; and Eve winked at him out of every fold of her rich chestnut hair. She was quick and impulsive in her motions; and although she showed such a blank front to the man opposite, her lips flickered with the desire to smile; and tiny frowns came and went between the twin crescents of her brows.

As for her, she was sizing him up too, though with skilfully veiled glances. She saw a square-shouldered young man, who sat calmly eating his lunch, without betraying too much self-consciousness on the one hand, or any desire to make flirtatious advances on the other. Yet he was not stupid, either; he had eyes that saw what they were turned on, she noted. His admirable, detached attitude piqued her, though she would have been quick to resent any other. She was angry with him for forcing this repression on her; repression was not natural to this young lady. She longed to clear the air with a burst of laughter, but the thought of a quick, cool glance of surprise from the steady eyes opposite effectually checked her. As for his features, they were well enough, she thought. He had a shapely head, broadest over the ears, and thatched with thick, straight hair of the ashy-brown just the other side of blonde. His eyes were of the shade politely called gray, though yellow or green might be said with equal truth, had not those colours unpleasant associations. His nose was longish, and he had a comical trick of seeming to look down it, at which she greatly desired to laugh. His mouth was well cut, and decisively finished at the corners; and he had a chin to match. In spite of her irritation with him, she was reminded of a picture she had seen of Henry Fifth looking out from his helmet on the field of Agincourt.

As the minutes passed, and Garth maintained his calm, she became quite unreasonably wroth. Her own luncheon was now before her. By and by she wanted salt, and the only cellar stood at Garth's elbow. Nothing could have induced her to ask for it; she merely stared fixedly. Garth, presently observing, politely offered the salt-cellar. She waited until he had put it down on the table, and removed his hand from the neighbourhood; then took it.

"Thank you," she murmured indignantly; furious at having to say it.

Garth wondered what he had done to offend her.

At this moment there was an interruption; again the apologetic Mr. Papps with yet another guest. This was a tradesman's comely young wife, with very ruffled plumage, and the distracted air of the unaccustomed traveller. She was carrying in her arms a shiny black valise, three assorted paper-covered bundles with the string coming off, and a hat in a paper bag; and, although it was so warm, she wore her winter's coat, plainly because there was no other way to bring it. Her hair was flying from its moorings; her face flamed; and her hat sat at a disreputably rakish angle. As she piled up her encumbrances on the chair next to the girl, and took off her coat, she bubbled over with indistinguishable, anxious mutterings. At last she sank into the seat by Garth with something between a sigh and a moan.

"I've lost my husband," she announced at large.

Her distress was so comical they could not forbear smiling.

Encouraged by this earnest of sympathy, the newcomer plunged into a breathless recital of her mischances.

"Just came in over the A. N. R.," she panted. "By rights we should have arrived last night, but day-before-yesterday's train had the right of way and we was held up down to Battle Run. I tell you, the rails of that line are like the waves of the sea! I was that sea-sick I thought never to eat mortal food again—but it's coming back; my appetite I mean. He was to meet me, but I suppose he got tired after seventeen hours, small blame—and dropped off somewheres. S'pose I'll have to make a round of the hotels till I find him. You don't happen to know him, do you?" she asked Garth. "John Pink, the carpenter?"

"I'm a stranger in Prince George," said he politely.

"Oh, what and all I've been through!" groaned Mrs. Pink, with an access of energetic distress. She shook a warning finger at the girl. "Take my advice, Miss," she warned, "and don't you let him out of your sight a minute, till you get him safe home!"

The girl looked hard at her plate; while for Garth, a slow, dark red crept up from his neck to the roots of his hair. Yet Mrs. Pink's mistake was surely a natural one; there they sat lunching privately together in the secluded little cabin. Moreover, they looked like fit mates, each for the other; and their air of studied indifference was no more than the air commonly assumed by young married couples in public places—especially the lately married. Without appearing to raise her eyes, the girl in some mysterious way, was conscious of Garth's dark flush. "Serve him right," she thought with wicked satisfaction. "I shan't help him out." But Garth's blush was for her more than for himself.

Mrs. Pink, absorbed in her own troubles, was innocently unaware of the consternation she had thrown them into. She plunged ahead; still addressing her remarks to the girl.

"Perhaps you think there's no danger of losing yours so soon," she went on; "and very like you're right. But, my dear, you never can tell! Bless you, when I was on my wedding journey, he hung around continuous. I couldn't get shet of the man for a minute, and I was fair tired out of seeing him. But that wears off—not that I mean it would with you"—turning to Garth—"but nothing different couldn't hardly be expected in the course of nature."

Garth considered whether he should stop Mrs. Pink's tongue by telling the truth. But it seemed ungallant to be in such haste to deny the responsibility. He felt rather that the disclaimer should come from the girl; and she made no move; indeed, he almost fancied he saw the ghost of a smile. Under his irritation with the woman and her clumsy tongue, he was conscious of a secret glow of pleasure. There was something highly flattering in being taken for the husband of such an ultra-desirable creature. The thought of her being really one with his future, as the woman supposed, and travelling about the country with him made his heart beat fast. Slender, trim and mistress of herself, she had exactly the look of the wife he had pictured.

Mrs. Pink broke off long enough to order her luncheon, and from the extent of the order it appeared she had entirely recovered her appetite.

"The next thing I have to do after finding my man," she resumed, with a wild pass at her hat, which lurched it as far over on the other side, "is to find a house. They tell me rents are terrible high in Prince George. Are you two going to settle here?"

Garth replied in the negative. He had decided if the girl did not choose to enlighten Mrs. Pink, he would not.

"It has a great future ahead of it," she said solemnly. "It's a grand place for a young couple to start life in. And elegant air for children. Mine are at my mother's."

Garth swallowed a gasp at this; but the girl never blinked an eye.

"But how I do run on!" exclaimed Mrs. Pink. "No doubt you've got a good start somewheres else."

"Not so very," said Garth with a smile.

The smile disarmed the young lady sitting opposite, and somehow obliged her to reconsider her opinion of him. "I believe the creature has a sense of humour," was her thought.

"Are you Canadians?" inquired Mrs. Pink politely.

"I am from New York," said Garth.

Mrs. Pink opened her eyes to their widest. If he had said Cochin China she could not have appeared more surprised. For New York has a magical name in the Provinces; and the more remote, the more glowing the halo evoked by the sound.

"Bless me!" she ejaculated. Then, addressing herself to the girl: "How fine the shops and the opera houses must be there!"

"I've not been there in some years," she answered coolly. "I am from Ontario."

"Well, I declare!" cried Mrs. Pink. "Quite a romance! Where did you meet?"

"Here," said Garth readily. There was no turning back now.

"What a nice man!" now thought this perverse young lady.

"Well! Well!" exclaimed Mrs. Pink with immense interest. "Ain't that odd now! Was it long since?"

"Not so very," said Garth vaguely. He glanced across the table and saw that his supposed wife had finished her lunch. His heart sank heavily.

"Three months?" hazarded Mrs. Pink.

"It was about half an hour ago," came brisk and clear from across the table.

Mrs. Pink looked up in utter amazement; her jaw dropped; and a piece of bread was arrested halfway to her mouth. The girl had risen and was drawing on her gloves.

"Good-bye, Mrs. Pink," she said sweetly. "I hope you find your husband sooner than I find mine!"

With that she passed out; and the swing door closed behind her. All the light went with her, it seemed to Garth, and the cabin became a sordid, spotty little hole. Mrs. Pink stared at the door through which she had disappeared, in speechless bewilderment. Finally she turned to Garth.

"Wh-what did she mean?" she stammered.

"I do not know the young lady," said Garth sadly.

"Good land, man!" screamed Mrs. Pink. "Why didn't you say so at first?"

GARTH PEVENSEY was a reporter on the New York Leader. His choice of an occupation had been made more at the dictate of circumstances than of his free will; and in the round hole of modern journalism he was something of a square and stubborn peg. He had become a reporter because he had no taste for business; and a newspaper office is the natural refuge for clever young men with a modicum of education, and the need of providing an income. He was not considered a "star" on the force; and his city editor had been known to tear his hair at the missed opportunities in Pevensey's copy, and hand it to one of the more glowing stylists for the injection of "ginger." But Garth had his revenge in the result; the gingerized phrases in his quiet narrative cried aloud, like modern gingerbread work on a goodly old dwelling.

It was agreed in the office that Pevensey was too quiet ever to make a crack reporter. On a big story full of human interest he was no good. It was not that he failed to realize the possibilities of such stories; he had as sure an eye for the picturesque and affecting as Dicky Chatworth himself, the city editor's especial favourite; but he had an unconquerable repugnance to "letting himself go." Moreover his stuff was suspected of having a literary quality, something that is respected but not desired in a newspaper office. Howbeit, there were some things Garth could do to the entire satisfaction of the powers; he might be depended on for an effective description of any big show, when the readers' tear-ducts were not to be laid under contribution; he had an undeniable way with him of impressing the great and the near-great; and had occasionally been surprisingly successful in extracting information from the supposedly uninterviewable.

Though his brilliancy might be discounted, Pevensey was one of the most looked-up-to, and certainly the best-liked man on the staff. He was entirely unassuming for one thing; and though he had the reputation of leading rather a saintly life himself, he was as tolerant as Jove; and the giddy youngsters who came and went on the staff of the Leader with such frequency liked to confide their escapades to him, sure of being received with an interest which might pass very well for sympathy. It was with the very young ones that he was most popular; he took on himself no irritating airs of superiority; he was a good listener; and he never flew off the handle. Such a man has the effect of a refreshing sedative on the febrile nerves of an up-to-date newspaper office.

Outside the office Garth led an uneventful life. He lived with his mother and a younger brother and sister, and ever since his knickerbocker days he had been the best head the little family could boast of. New York is full of young men like Garth who, deprived of the kind of society their parents were accustomed to, do not assimilate readily with that which is open to all; and so do without any. Young, presentable and clever, Garth had yet never had a woman for a friend. Those he met in the course of a reporter's rounds made him over-fastidious. He had erected a sky-scraping ideal of fine breeding in women, of delicacy, reserve and finish; and his life hitherto had not afforded him a single opportunity of meeting a woman who could anywhere near measure up to it. That was his little private grievance with Fate.

Garth came of a family of sporting and military traditions, which he had inherited in full force. These, in the young bread-winner of the city, had had to be largely repressed; but he had found a certain outlet in joining a militia regiment, in which he had at length been elected an officer. He had a passion for firearms; and was the prize sharpshooter of his regiment. Wonderful tales were related of his prowess.

When the Leader was invited to send a representative on the excursion of press correspondents, which an enterprising immigration agency purposed conducting through the Canadian Northwest, Garth was chosen to go—most unexpectedly to himself, and to the higher-paid men on the staff. This trip put an entirely new colour on Garth's existence. He had always felt a secret longing to travel, to wander under strange skies, and observe new sides of life. From the very start of the journey he found himself in a state of pleasant exhilaration which was reflected in the copy he sent back to his paper. Pevensey's articles on the West made a distinct hit. The editors of the Leader did not tell him so; but in the very silence from New York that followed him, he knew he had found favour in their eyes; and he felt the delicious gratification of one who has been unappreciated.

When the excursion, lapped in the luxury of a private car (nothing can be too good for those who are going to publish their opinions of you), reached Prince George, the outermost point of their wide swing around the country, the good people of the town outdid themselves in entertaining the correspondents. Among the festivities, a large public reception gave the correspondents and the leading men of the country the opportunity to become acquainted. To Garth the most interesting man present was the Bishop of Miwasa. His Lordship was a retiring man in vestments a thought shabby; and the other correspondents overlooked him. But Garth had heard by accident that the Bishop's annual tour of his diocese included a trip of fifteen hundred miles by canoe and pack-train through the wilderness; and he scented a story. The Bishop was one of those incorrigibly modest men who are the despair of interviewers; but Garth stuck to him, and got the story in the end. It was the best sent out of Prince George on that trip.

During the five days the correspondents spent there, the quiet Garth and the quiet Bishop became fast friends over innumerable pipes at the Athabasca Club. They discovered a common liking for the same brand of tobacco, which created a strong bond. Garth was entranced by the Bishop's matter-of-fact stories of his long journeys through the wilderness during the delightful summers, and in the rigorous winters; and the upshot was, the Bishop asked him to join him in his forthcoming tour of the diocese, which was to start from Miwasa Landing on the first of August.

Garth jumped at the opportunity; and telegraphing lengthily to his paper to set forth the rich copy that was pining to be gathered in the North, prayed for permission to go. He received a brief answer, allowing him two months' leave of absence for the journey at his own risk and expense; and promising to purchase what of his stuff might be suitable, at space rates. This was precisely what he wanted; it meant two months' liberty. By the time he received it, the excursion had left Prince George behind; and was turned homeward. Garth dropped off at a way station and made his way back, this time without any fêtes to greet his arrival. He caught the Bishop as he was starting for the Landing; and it was arranged Garth should follow him by stage, three days later. Meantime he was to purchase an outfit.

On the evening of the day following his luncheon at Papps's, Garth, in his room at the hotel, was packing in a characteristically masculine fashion, preparatory to his start for the North woods next day.

It would have been patent to an infant that he had something on his mind. He was not thinking of the romantic journey that lay before him; that prospect, so exhilarating the past few days, had, upon the eve of realization, lost its savour. He would actually have welcomed an excuse to postpone it for a few days—so that he might spend a little more money at Papps's. It was a pair of flashing blue eyes—for blue eyes do flash, though they be not customarily chosen to illustrate that capacity of the human orb—which had disturbed his peace. He was very much dissatisfied with the part he had played at luncheon the day before. What he ought to have said and done was now distressingly clear to him; and he craved an opportunity to put it into practice. He had spent the whole middle part of this day at Papps's, loitering in the entrance to make sure the blue eyes should not be swallowed in one of the cabins without his knowledge; but they had not illumined the place; nor had his cautious inquiries elicited a single clue to the identity of the possessor. He felt sure if he had three days more in Prince George he could discover her: but unfortunately the weekly stage for the North left the following morning; and the Bishop was waiting for him at the Landing; likewise the Leader back in New York was waiting for stories—and not about blue eyes. It was at this point in his circular train of reflections that he would resume packing with a gusty sigh.

He was interrupted by a knock on the door, and, upon opening it, was not a little astonished to receive a note from the hands of a boy, who signified his intention of waiting for an answer. It was contained in a thick, square envelope with a crest on the flap; and was addressed in a tall, angular, feminine hand. Garth, his mind ever running in the same course, tore it open with a crazy hope in his heart; but the first words brought him sharply back to earth.

"Will Mr. Garth Pevensey," thus it ran, "be good enough to oblige an old lady by calling at the Bristol Hotel this evening? Mrs. Mabyn will be awaiting him in the parlour; and as it concerns a matter of supreme importance to her, she trusts he will not fail her; no matter how late the hour at which he may be able to come."

Garth dismissed the boy with a message to the effect that he would answer the note in person. As he leisurely put his appearance in order, he thought: "Verily one's adventures begin upon leaving home." He was human, consequently his curiosity was pleasantly stimulated to discover what lay before him: but the little adjective in the first sentence of his appellant's letter was fatal to the idea of any violent enthusiasm on her behalf.

The parlour of the Bristol Hotel was on the first floor above the street level. Garth paused at the door; and cast a glance about the room. It was empty except for two figures at the further end. The one he could see more plainly was an old lady sitting in an easy-chair; she was dressed in black, with a white cap and white wristbands; a spare, erect little lady. Garth judged her to be the writer of the note. The other figure, also a woman, was partly hidden in a window embrasure. She was standing by the window holding the curtain back with one hand, and looking into the street. She turned her head to speak to the old lady; whereupon Garth's heart leapt in his bosom, the room rocked, and the chandeliers burst into song; that clear profile, that slender figure could belong to none in Prince George but Her! He was overcome with delight and amazement; he could scarcely credit his eyes. He wished in the same instant he had spent more care on his appearance, and that he had not kept them waiting so long.

The younger lady perceived him standing in the shadowy doorway, and came toward him.

"Mr. Pevensey?" she began in a voice of cool inquiry. Then she stopped aghast; and the colour flamed into her face. "You!" she exclaimed in a voice too low to reach the older woman's ears. "Oh, I didn't know—I never suspected it might be you!"

Garth was conscious of a complicated feeling of irritation, a kind of jealousy of himself. "Why did they send for me, if they didn't know it was me?" was his thought.

"What must you think of me?" she said in obvious distress.

"I am in the dark," said Garth helplessly.

She recovered her forces. "I am not in the habit of going to restaurants alone," she said. "But the hotel here is so bad! I am afraid you must think me a frivolous person, and I am anxious you should not think so."

"I don't," said Garth bluntly.

She smiled. "Very well," she said; "then there's no harm done."

"Natalie!" called the old lady, with a hint of irritation.

"Come and meet Mrs. Mabyn," she said quickly; and led the way.

"This is Mr. Pevensey, Mrs. Mabyn," she said.

The old lady regarded Garth with a sharp scrutiny; and Garth looked with interest at her. She was a fragile, elegant, plaintive little person of the old "lady-like" régime; but for all her gentleness, Garth was somehow conscious that he faced a woman of an iron will. She had the impatient, inattentive manner of one possessed by a single idea. With the result of her examination she appeared but half satisfied; she held out a delicate, wrinkled hand, dubiously.

"How do you do?" she said. "Please sit down."

"I am Natalie Bland," further explained the girl, who had again retreated to the window embrasure. "Mrs. Mabyn and I are travelling together."

"Dear Natalie is a daughter to me," murmured Mrs. Mabyn with commendable feeling.

The two women exchanged a glance which Garth was at a loss to interpret. He was looking at Natalie and he thought he saw patience, real affection, and perhaps a little kindly amusement—but there was something beyond; something grimmer and more determined, a hint of rebellion.

"My husband, Canon Mabyn, was the rector of Christ's Church Cathedral in Millerton, Ontario, up to the time of his death," murmured Mrs. Mabyn in her dulcet tones, with the air of one delivering all-sufficient credentials.

Garth murmured to show that he was suitably impressed.

"You are from New York, I believe," said Mrs. Mabyn.

Garth acknowledged the fact.

"So the newspaper said," she remarked. "Of course, I know very few Americans, still it is possible we may have common friends. You—er—" She paused invitingly.

"Hadn't we better explain why we asked Mr. Pevensey to call?" put in Natalie quietly.

"My dear, Mr. Pevensey was just about to tell me of his people," Mrs. Mabyn said in tones of gentle reproof.

Garth saw what the old lady would be after. "My father, Lieutenant Raymond Pevensey, was in the Navy," he said. "He was killed by a powder explosion on the gunboat Arkadelphia, twelve years ago."

"Dear me, how unfortunate!" murmured Mrs. Mabyn sympathetically; but it rang chillingly, and her abstracted eyes dwelt throughout upon that relentless thought of hers, whatever it was.

"I am related distantly to the Buhannons of Richmond, and the Mainwarings of Philadelphia," continued Garth, willing to humour her.

"There was a Mainwaring at Chelsea with my husband as a boy," remarked Mrs. Mabyn.

"Probably my great-uncle," he said. "In this part of the world," he went on, "there is no one who knows me beyond mere acquaintanceship, except the Bishop of Miwasa—"

"Pray say no more, Mr. Pevensey," interrupted Mrs. Mabyn. "The mere fact that the Bishop invited you to accompany him is, after all, sufficient." She turned to the girl. "You may continue, dear Natalie."

"We read in this evening's paper," began that young lady with a directness refreshing after Mrs. Mabyn's circumlocutions; "that you were starting for Miwasa Landing to-morrow morning, to join the Bishop on his annual tour. We wished particularly to see you before you started; and that is why I—why Mrs. Mabyn wrote."

"We thank you for coming so promptly," put in Mrs. Mabyn with her gracious air.

Garth murmured truthfully that the pleasure was his. He felt himself on the breathless verge of a discovery. Intuition warned him of what was coming; but he could not believe it yet.

"Mr. Pevensey," resumed the young lady as if with an effort; she had the humility of a proud soul who stoops to ask a favour; "we are going to make a very strange request, as from total strangers."

Mrs. Mabyn raised an agitated hand. "Wait, wait, my dear Natalie," she objected. "Perhaps after all, we had better go no further. I—I think we had better give the plan up," she said in apparently the deepest distress.

The girl turned a patient shoulder, and looked into the street again, abstractedly playing with the cord of the blind.

"It is really too much to ask of you," continued Mrs. Mabyn distressfully; "and I am so afraid for Natalie! Natalie is so very dear to me. The situation is so unusual!" she wailed.

Poor Garth was sadly perplexed and exasperated by all this. The discovery he anticipated was now apparently in retreat.

"We are glad, anyway, to have had the pleasure of making your acquaintance," said Mrs. Mabyn with an air of finality.

Suddenly it was borne in upon Garth, partly from the girl's patient attitude, partly from the other's emphasis upon her distress, that it was simply, in newspaper parlance, all a bluff on the part of the older woman. Her fanatic eyes seemed to tell him that she was still bent on her object, whatever it might be. Experience had taught him that the quickest way to find out if he were right was to seem to fall in with her desire. So he promptly rose as if to leave. It worked.

Mrs. Mabyn's eyes snapped. She did not relish being taken up so quickly. "One moment, Mr. Pevensey," she said plaintively—and hastily. "Overlook the distraction of an old woman; I am torn two ways!"

Garth understood by this that the matter was reopened; and sat down again. There was a pause, while the old lady struggled, with the air of a martyr, to regain her composure. The girl continued to look stolidly out of the window; and Garth simply waited for what was coming.

"You may continue, Natalie," said Mrs. Mabyn at length, faintly.

The girl resumed her explanation at the exact point where she left off. "We expected—that is, we hoped you were an older man—" Garth looked so disappointed she immediately added: "For that would make the request seem less strange." She hesitated.

"What is it?" asked Garth.

But she parried awhile. "What sort of a man is the Bishop?" she asked.

Garth described his modesty and his manliness.

"A very proper person to be Bishop in a wild country," remarked Mrs. Mabyn, patronizingly.

"And his wife?" asked Natalie.

Garth pictured a homely, unassuming body, with a great heart.

"Of course!" said Mrs. Mabyn. A whole chapter might be devoted to the analysis of the tone in which she said it.

"We had heard she accompanies her husband," said Natalie.

"Yes," said Garth.

"That simplifies matters!" exclaimed Mrs. Mabyn.

"Their route takes in Spirit River Crossing, I believe," pursued Natalie.

Garth affirmed it, wondering.

Natalie paused before she went on. "Whatever you may think of what I am going to tell you, Mr. Pevensey," she said with the same proud appeal in her voice, "we may count on you, I am sure, not to speak of it to any one for the present."

"Indeed you may!" he said warmly.

"I am obliged to get to Spirit River Crossing at the earliest possible moment," she said simply.

Through the wilderness with her! Garth had to wait a moment before he could trust himself to reply with becoming coolness.

"Have you considered the kind of a journey it is?" he asked quietly.

"That is the worst of it!" complained Mrs. Mabyn. "I had expected to go with her; but we find it is out of the question."

Garth hastened to assure her that it was.

"I have considered everything," said Natalie.

"But do you know that you will have to travel two or three weeks in an open boat in all weathers, a mere canoe in fact; that you will have to sleep out of doors, and live on the very roughest of fare? Could you stand it?" he demanded almost sternly.

"I am perfectly well and strong," answered Natalie.

"That is quite so, happily," said Mrs. Mabyn. "Otherwise, I would not hear of it for a moment."

"If the Bishop's wife can stand it, certainly I can," said Natalie.

"But she is obliged to do it," said Garth.

"So am I!" said Natalie quickly.

There was an awkward pause. Garth said nothing, but his question was felt.

"Naturally you wonder what forces me to undertake such a journey," said Natalie uncomfortably.

"Couldn't I help you more intelligently if I knew?" suggested Garth.

"But I cannot tell you," she said. "That is, not yet. Believe me, it is nothing I need be ashamed of——"

"Natalie!" exclaimed Mrs. Mabyn indignantly. "Is it not I who urge you to go?"

"Yes, I am doing what will be considered a most praiseworthy thing," said Natalie with what sounded strangely like—bitterness.

"Yes, indeed!" urged Mrs. Mabyn, who seemed to have forgotten her late anxiety on Natalie's account.

"But in telling you," objected Natalie gently, "I would have to trust you to a far greater extent than you would be trusting me, in lending me, without knowing my reasons, the assistance of one traveller to another."

Garth was ready enough to throw himself at her feet without this affecting appeal. "Please count on me," he said, moved more than he would let them see, especially the old woman. "How can I help you?"

"See me as far as Miwasa Landing," she said simply. "I will then throw myself on the goodness of the Bishop and his wife; and trust to them to take me with them the rest of the way—that is, if I wish to go. The Bishop may be able to give me information," she added darkly.

"Natalie!" put in Mrs. Mabyn, warningly. "I—I will give her letters to those good people," she added hastily, to divert Garth's mind from the strangeness of Natalie's last words.

But Garth was in no temper to be deflected by a mystery. "I am thankful for the chance to be of service," he said fervently, having a keen sense of the poverty of words.

"Thank you," said Natalie, simply. "Let us talk of ways and means," she added decisively. "What should I take?"

AT a quarter to eight next morning Garth was waiting again in the parlour of the Bristol Hotel. Promptly to the minute Natalie came sailing in, in her own inimitable way, walking all of a piece, with a sweep like a banner, Garth thought. When he saw her, his last doubt of the reality of this intoxicating journey vanished. She bore no trace now of the seriousness of the night before; all smiles and red-cheeked eagerness, she radiated the very joy of being.

"Enter Mrs. Pink!" she cried.

She had a brown valise, a fat bundle, a flat, square package wrapped in paper, a coat and a parasol.

"You said trunks were taboo," she explained. "I only had one valise and I couldn't nearly get everything in. Indeed I sat up half the night studying how little I could do with."

"We'll get you a duffle-bag at the Landing," he said.

"Am I suitably dressed?" she demanded, showing herself.

Garth smiled. She was perfection; how could he blame her? She had interpreted his suggestions as to sober, serviceable clothes, in a diabolically well-fitting suit of brown, the colour of her hair. At the wrists and neck of her brown-silk waist were spotless bands of white; and on her head was a dashing little brown hat with green wings. She exhibited square-toed little brown boots as an evidence of exceeding common sense; and was pulling on a pair of absurdly small boy's gloves. This most suitable costume for the North was completed by a brown-silk parasol.

"All in place and well tied down," she announced. "Nothing to fly or catch!"

Garth pictured to himself the effect likely to be created in the wilderness by this adorable acme of the feminine, with something between a smile and a groan.

They walked to the post office, quaffing deep of the delicious morning air, Garth glancing sidewise at his exuberant companion, and wondering, like the old lady in the nursery rhyme, if this could really be he. It was a day to make one walk a-tiptoe; the sky overhead bloomed with the exquisite pale tints of a Northern summer's morning; and the bricks of Oliver Avenue were washed with gold.

Natalie's face fell a little at the sight of the stage-coach; for it had nothing in common with the imagined vehicle of romance except the four horses; and they were but sorry beasts. In fact, it was nothing but a clumsy, uncovered wagon, which had never been washed since it was built; and was worn to a dull drab in a long acquaintance with the alternating mud and dust of the trail. Behind the driver's seat was a sort of well, for the mail bags and express packages; and behind that, two excruciatingly narrow seats for the passengers, running lengthwise between the rear wheels. The entrance was by a step at the tail-board.

Everything awaited the word to start. The driver, whip in hand, stood by the front wheel surrounded by a group of idlers; and his two great mongrel huskies, squatted on the pavement with expectant eyes on their master. Garth helped Natalie into the body of the wagon; and, climbing in after her, disposed her baggage with his own already in the well. The eyes of the driver and all his satellites were promptly transferred in wide wonder to the girl with the green wings in her hat. Garth, with a keen sense of difficulties ahead, was indignant and uncomfortable; but Natalie, serenely conscious that everything was in place, dropped her hands in her lap, and chatted away, as if quite unaware of her conspicuousness.

Garth had put Natalie in the right-hand corner of the little cockpit. Another woman passenger was already in place opposite; and the aspect of this lady made an additional element in his uneasiness. She, too, was gotten up bravely according to her lights. She seemed something under forty, tall and angular; her hair, a crass yellow, was tied with a large girlish bow of black ribbon behind; and in her cheeks she had crudely striven to recall the hues of youth. Around her long neck another black ribbon accentuated the scrawny lines it was designed to hide; and on top of all she wore a wide black hat, which had a fresh yet collapsed effect, as if it had long been cherished under the lid of a trunk. Her knees touched Natalie's, and Garth's gorge rose at her nearness to his precious charge—and yet the antique girl greeted them with a sort of anxious, appealing smile, which disarmed him in spite of himself.

Promptly at eight o'clock the door of the post office was opened; and the last bag of mail was thrown into the stage. Still the driver made no move to climb into his seat; and Garth, becoming restless as the minutes passed, got out and approached him.

"Good morning, driver," he said, while the bystanders stared afresh. "What's the delay?"

He gazed at Garth with a mild and cautious blue eye; and spat deliberately before replying. He was one of those withered little men, with a shock of grizzled hair, and deeply seamed face and neck and hands, who might be forty-five or seventy. As it turned out, Paul Smiley was within three years of the latter figure. He had on a pearl Fedora very much over one ear, a new suit of store clothes with a mighty watch chain, and new boots, which seemed like little souls put to torment—they screeched horribly whenever he moved.

"I couldn't start off and leave Nick Grylls," he said deprecatingly. "He has spoke for two seats."

Garth was sensible that he was hearing a great man's name.

"I tell you it ain't often Nick Grylls travels by the stage," continued Smiley, addressing the bystanders impressively. "He hires a rig and a team and a driver to take him to the Landing, he does."

"Who is this Mr. Grylls?" asked Garth, pursuing the reporter's instinct.

"Don't know Nick Grylls!" exclaimed old Paul, exchanging a wondering glance around the circle. "You must be a stranger! Nick Grylls is a wonderful bright man, wonderful! He's the biggest free-trader in the North country; trades down Lake Miwasa way. Wonderful influence with the natives; does what he wants with them. I tell you there ain't much north of the Landing Nick Grylls ain't in on. Here he comes now! All aboard!"

As Garth resumed his seat by Natalie he saw a burly, broad-shouldered figure hurrying along the sidewalk; he saw under the wide, stiff-brimmed hat, a red face with an insolent, all-conquering expression, and fat lips rolling a big cigar. There followed after, a young breed staggering under the weight of a Gladstone bag, which matched its owner. Arrived at the stage, Nick Grylls flung a thick word of greeting to the bystanders, and taking the bag from the boy, threw it among the mail bags as one tosses a pillow; and climbed into the seat by the driver. The breed sprang on the step behind; another passenger took the place opposite Garth; old Paul cracked his whip and shouted to his horses; the dogs leaped and barked madly; and the Royal Mail swung away to the North with its oddly assorted company.

As they rattled through the suburbs the fat back on the front seat shifted heavily; and the red face was turned on them.

"Hello, old Nell!" shouted Nick.

The woman simpered unhappily. "How's yourself, Mr. Grylls?" she returned.

"Fine!" he bellowed from his deep chest.

This little manoeuvre in the front seat was merely for the purpose of obtaining a prolonged stare at Natalie. The insolence of the little, swimming, pig-eyes infuriated Garth. The young man opposite him too, a sullen, scowling bravo, was staring boldly at Natalie. Garth stiffened himself to play a difficult part.

"I feel like a rare, exotic bird," whispered Natalie in his ear.

"You are," he returned grimly. "I think it would be better if you did not speak my name," he added. "I will not address you by yours. We must be prepared to parry questions."

"I will be careful," she said.

To do him justice, Nick Grylls, on a close examination of Natalie, had the grace to feel a little ashamed of his rough outburst. He altered his features to what he thought was a genteel expression; but Garth called it a leer.

"Bully day for our trip," he said.

They all agreed in various tones; even Garth. He knew it would not help Natalie for him to start by inviting trouble.

"You're the New York newspaper man," said Grylls to Garth.

"That's right," said Garth quietly.

"They tell me you're going to write up the country," said Grylls; exhibiting that curious blend of suspicion, contempt and respect his kind has for the fellow who writes. "I can tell you quite a bit about the country myself," he added with a braggadocio air.

Garth thanked him.

"It's an onusual trip for a lady," continued Grylls, cunningly trying to draw Natalie into the conversation; "but nothing out of the way at this season. The Bishop travels comfortable enough; separate tent for the women; and an ile stove like."

His move was not successful; Natalie continued looking charmingly blank. Old Paul created a diversion by facing them with a confiding smile. The pert Fedora with its curly brim was comically ill-suited to his seamed old face, and mild blue eye. He pointed with his whip down a road on the outskirts of the town.

"My place is down there," he said simply. "Just sold it last week; three hundred acres at three hundred dollars an acre. They're layin' it out in town lots."

"Good God, man!" cried Grylls. "You could buy me out and have a pile over!" Every time he spoke, he glanced over his shoulder at Natalie.

Old Paul smiled up at him admiringly. "But this is only a sort of accident," he said. "You made yours."

"What in he—Why are you driving the stage, then?" demanded Grylls.

"Well," said the old man slowly; "seems though I just got in the way of it. Seems I just had to keep hanging on to the ribbons, or lose holt altogether."

"What are you going to do with all that money?" Grylls wanted to know.

"Well," said Paul with a quiet grin; "I bought me a new hat like the swells wear; and a pair of Eastern shoes. They pinch me somepin' cruel, too."

"Why don't you travel East, Mr. Smiley?" suggested Nell. She whom they all addressed so cavalierly was particular to put a handle to each name.

"Travel! I had enough o' that, my girl," he said. "Forty-five years ago I travelled East to Winnipeg and got me a wife. Brought her back over the plains in a Red River cart. Eight hunder miles, and hostile redskins all the way! What's travellin' nowadays!"

"Were you born out here?" asked Garth, shaping a story for the Leader in his mind.

"At Howard House, west of here in the Rockies," said Paul. "My father was Hudson's Bay trader there."

"Paul's an old-timer all right," said Grylls carelessly. He was becoming bored with the trend the conversation was taking.

"One of the first eight who broke ground in Prince George," said the old man proudly. "Yonder's the first two-story house in the country. I built it. No!" he continued thoughtfully; "I'm keeping my house and ten acres; and me and the old woman's calc'latin' to stop there and watch the march o' progress by our door. She wouldn't give up her front step for all the real-estate sharks in Prince George. But," he added with a chuckle, "I shouldn't wonder if she was shocked some when them trolley-cars I hear tell of goes kitin' by."

"I kin understand just how she feels," remarked old Nell to Natalie, with her apologetic little smile. "What could take the place of a home with real nice things in it? I got a house up near the Landing with a carpet in every room. I just love to buy things for it. You see I never had what you might call a regular house until just lately. This trip I bought a pink-and-gold chiny washin' set; and a down comfort for the best room. I never could tire of fixin' it up. We'll pass there to-morrow afternoon. I'd just love to have you step in—"

Grylls laughed boisterously.

"Ah-h, shut up, Nell!" muttered the dark young man beside her.

"Thank you, I'd like to see it," said Natalie, with a flash of the blue eyes.

They had now left the town behind; and were rolling, or rather bumping, over the prairie. Here, it is not an empty plain, but a series of natural, park-like meadows, broken by graceful clumps of poplar and willow. On a prairie trail when the wheels begin to bite through the sod, and sink into ruts, a new track is made beside the old—there is plenty of room; and in turn another and another, spreading wide on each side, crossing and interweaving like a tangled skein of black cotton flung down in the green.

Natalie had never seen such luxuriant greenness; such diverse and plentiful wild flowers. Nell pointed out the brilliant fire-weed, blending from crimson to purple, the wild sunflower, the lovely painted-cup, old-rose in colour; and there were other strange and showy plants she could not name. Occasionally they passed a log cabin, gayly whitewashed, and with its sod roof sprouting greenly. These dwellings, though crude, fulfilled the great aim of architecture; they were a part of the landscape itself.

When they stopped at one of these places for dinner, Garth watched Natalie narrowly to see how she would receive her first taste of rough fare. But far from quailing at the salt pork, beans and bitter tea, she ate with as much gusto as if it had always been her portion. "She'll do," he thought approvingly.

Afterward as they toiled up a long, sandy rise in the full heat of the afternoon sun, Paul, the old dandy, had leisure while his horses walked to devote to his passengers. He was pleased as a child at the interest shown by Garth and Natalie in his anecdotes. Turning to them now, he pointed to a high mound topped by a splendid pine standing by itself, and said:

"Cannibal Hill. Used to be an Indian called Swift had his lodge there. A fine figger of a man too; high-chested; beautiful-muscled. He was a good Indian; and I want to say when a redskin is good, he's damn good—beg pardon, Miss—he's good and no mistake, I should say. He has a high-minded way of looking at things, which ought to make a white man blush; but it don't; for them kind makes the softest tradin'. I been a trader myself.

"This here Swift had a wife and ten childer, that he thought a power of. He hunted for 'em night and day; and he come to be known as the best provider in the tribe. Well, come one winter he went crazy; yes, ma'am, plumb looney; and he went for 'em with his hatchet. He killed and et 'em one at a time, beginning with the youngest; while the others waited their turn. You see an old-fashioned Indian was the boss of his family; and they didn't dast fight him back. Right up there on that hill, under that very same tree; I seen the ashes of their bones myself. In the Spring he come down to the settlement and give himself up; said he didn't want to live no more. Shouldn't think he would."

Grylls made no secret of his impatience with the old man's yarns. He interrupted him, careless of his feelings.

"Are you making the round trip with the Bishop?" he asked Garth.

Garth answered in the affirmative.

"I have a rabbit-skin robe at the Landing I'd be glad to lend the lady," he said leering sidewise at Natalie.

"Much obliged," said Garth agreeably; "but we really have all we can use."

"What does she say?" growled Nick.

"Thank you very much," said Natalie quickly; "but I could not think of accepting it."

He had forced her to speak to him at last; but the words were hardly to his satisfaction. He flung around in his seat with an ugly scowl.

Meanwhile old Paul was still pursuing his thoughts about redskins. "Indians think when they go off their heads they're obliged to be cannibals," he continued agreeably. "They can't separate the two idees somehow. So when a redskin feels a screw beginning to work loose up above, he settles on a nice, fat, tender subject. He says his head's full of ice, and has to be melted. I mind one winter at Caribou Lake forty years back, we were all nigh starving, and our bones was comin' through our skins, like ten-p'ny nails in a paper bag. And one night they comes snoopin' into the settlement an Indian woman as sleek and soft and greasy as a fresh sausage—and lickin' her chops—um—um! There was a man with her and he let it out. She had knifed two young half-breed widows, as fair and beautiful a two girls as ever I see—and she et 'em, yes, ma'am! And nobody teched her; they warn't no police in them days. She lives to the Lake at this day!"

"Good Law! Mr. Smiley!" cried Nell with an uneasy glance at the grinning half-breed on the tail-step.

"Keep cool, old gal!" growled Nick. "Nobody wouldn't pick you out for a square meal!"

Nell's companion rewarded this sally with an enormous guffaw; and poor, mortified Nell made believe to laugh too. Natalie's cheeks burned.

"I suppose you hunted buffalo in the old days," said Garth to old Paul.

"Sure, I was quite a hunter," he returned with a casual air. "It weren't everybody as was considered a hunter, neither. You had to earn your reppytation. We didn't do no drivin' over cliffs or wholesale slaughterin'; it was clean huntin' with us, powder and ball. I mind they used to make a big party, as high as two hundred men, whites, breeds, and friendly redskins. Everything was conducted regular; camp-guards and a council and a captain was elected; and all rules strict observed. Every night we camped inside a barricade. One of the rules was, no tough old bulls useless for meat should be killed under penalty of twenty-five dollars. I was had up before the council for that; but I proved it was self-defense."

"Tell us about it," suggested Garth.

The old man scratched his head, and shot a dubious glance at Natalie. "I ain't sure as this is quite a proper story," he said. "You see, I was having a wash, as it might happen, at the edge of a slough—a slough is a little pond in the prairie, Miss, as you're a stranger—and my clothes and my gun was lying beside me, and my horse was croppin' the grass at the top of the rise. When I was as clean as slough water would make me, which isn't much, 'cause I stirred up a power of mud, and soap was an extravagance them days, I begun to dress myself. Well, I had my shirt on, and was sittin' down to pull on my pants, when I heard my cayuse start off on a dead run. I looked up quick-like and blest if there wasn't old Bill Buffalo a-pawin' and a-bellerin' and a-shakin' of his head, not thirty yards away! Soon as he see me look up he come chargin' down on me with his big head close to the ground like a locomotive cow-catcher. And me in that awkward state of dishabilly!"

"What did you do, Mr. Smiley?" cried Nell in suspense.

Paul shifted his quid, spat, and shoved his pearl Fedora a little further over his ear. "G'lang there," he cried shaking the reins. "I reached my gun before he reached me," he said; "and I gave him the charge, bang in his little red eye. He reared up; and come down kerplunk right on top o' me; only I rolled away just in time!"

The trail to the Landing is considered something of a road up North; and the natives are apt to stare pityingly at the effeminate stranger who complains of the holes. It is something of a road compared to what comes after; but Natalie, hitherto accustomed to cushions and springs in her drives, could not conceive of anything worse. As the afternoon waned, what with the heat, the hard, narrow seat, and the incessant lurching and bumping of the crazy stage, which threw her now backward till her head threatened to snap off, and now forward on Nell's knees, the blooming roses in Natalie's cheeks faded, and her smile grew wan. Poor Garth, anxiously watching her, almost burst with suppressed solicitousness.

But at last the journey came to its end; and at six o'clock the Royal Mail with its bruised and famished passengers swung into the yard at Forbie's, the halfway house, fifty miles from Prince George. Garth had learned that the men slept in an outside bunkhouse, while the women were received into the farmhouse itself. He hastened to interview Mrs. Forbie in private, that the dreadful possibility of Natalie's being asked to share a room with the other woman passenger might be avoided. It is doubtful if Natalie would have taken any harm from poor old Nell; but Garth was a young man falling in love; and so, ferociously virtuous in judging Nell's kind. Natalie had a room to herself.

NEXT morning, Old Paul, assisted by Nell's dark companion, and the half-breed Xavier, was hitching up in the yard of Forbie's, when Nick Grylls appeared from the house, and walked heavily up and down at some distance moodily chewing a cigar. Big Nick was wondering dully what in hell was the matter with him. He had tossed in his bunk the night through; and now, at the beginning of the day, when a man should be at his heartiest, he found himself without appetite for his breakfast, and in a grinding temper, without any object to vent it on. In his little eyes, bloodshot with the lack of sleep, and unwonted emotion, there was an almost childish expression of bewilderment.

A deep sense of personal injury lay at the root of his discomfort. Nick was accustomed to think of himself as a whale of a fine fellow, as they say in the West; he heard every day that he was the smartest man up North; and, of course, he believed it. He regarded himself as a prince of generosity; for was not his liberality to the half-breed women a reproach among cannier white men? He was fond of children, too; and one of his amusements was to distribute handfuls of candy over the counter of his store. And candy ("French creams," God save the mark!) is worth seventy-five cents a pound on Lake Miwasa. When any poor fellow froze to death, or went "looney" in the great solitudes, it was Nick Grylls who dug deepest in his pocket for the relief of the unfortunate family. This, then, was the meat of his amazed grievance; that he, the great man, the patron, should, here in his own country, be coolly ignored by a mere boy and girl.

There was good in Nick Grylls; and Garth travelling alone would have got along very well with him, and worked him for copy; but having Natalie to look after, he instinctively put himself on his guard against the triumphant Silenus. Grylls, with an enormous capacity for pleasure, had carelessly taken his fill. He had to content himself with the coarse plants of the North; and up to now he had desired no other. But he had arrived at the age when, the passions beginning to cool, the grossest man conceives of fastidiousness; and at this crisis Fate had thrust a perfect blossom before him. Never so close to a woman of Natalie's world before, he had been free to look at her throughout an entire day; and she had actually spoken to him once. He did not realize what was the matter with him yet; but presently, when Natalie came out of the house, he would know.

Garth strolled out from breakfast; and filled his pipe while he waited for Natalie to repack her valise within. Nick's chaotic passions leaped to meet the aspect of the cool young man, and fastened on him. But there was no relief here; his hearty and irresistible career over prostrate necks was suddenly arrested in the light of Garth's cool glance. In his heart Nick suspected he was despised, and the fact emasculated his rage. He hung his head, and looked elsewhere.

When the horses were hitched, Xavier went into the bunkhouse for his master's bedding, old Paul pottered around the harness, while Albert, Nell's companion, strolled back to join Grylls.

"What do you make of this young couple?" asked Nick, assuming an indifferent air.

"I dunno," Albert returned lethargically.

"There wasn't anything about a girl in the newspaper," pursued Nick; "and young reporters don't generally have coin enough to travel with a wife."

"They ain't married," said Albert.

"What!" exclaimed Nick eagerly.

"Nell says she heard her call him Mr. Pevensey before the stage started; and he called her Miss What's-this."

Nick's little eyes glittered. "Then what in hell are they doing up here together?" he muttered.

"Search me!" said Albert indifferently. "Nell says she can't make it out."

"She seems to have taken a kind of shine to Nell," suggested Nick carefully. "Women are sly as links. Pass a quiet word to Nell to draw her out."

"She's tried," said Albert. "Nice as you please but mum. Why don't you pump him?" he suggested, indicating Garth.

"Because he's a damned, self-sufficient dude!" Nick burst out with a string of curses. "One of these porridge-mouthed Easterners that run up their eyebrows with a 'my word!' at any free speech or liberality in a man! The first time he finds himself in man's country he patronizes us! Going to write us up! My God! My stomach turns over every time I look at him!"

"Well, he better not get you down on him," said Albert propitiatingly.

Natalie came sailing out of the farmhouse as fresh and smiling as the morning itself. Garth hastened to meet her. A dark flush rose in Grylls's cheeks, and he gritted his teeth, until the muscles stood out in lumps on either side his jaw. He felt a desire to possess this slender, swimming figure mounting in his brain to the pitch of madness. As she passed him Natalie nodded not unkindly, and the big man's eyes followed her in a sort of dog's agony.

Nell followed her out of the house; and Garth handed them both into the stage. He did not get in himself, but stood on the ground below Natalie, talking up to her. One of the horses had refused to drink at the trough, and old Paul, wishing to give him another chance, sent Xavier for a pail of water.

This Xavier deserves a word. The young breeds run to extremes of good looks or ill; and in his case it was the latter. In downright English he was hideous. A shock of intractable, lank hair hung over what he had of a forehead; and underneath rolled a pair of whitey-blue eyes, with a villainous cast in one of them. Some accident had carried Nature's work even further, for one swarthy cheek was divided from temple to chin by a dirty white scar. He wore a pair of black-and-white checked trousers, which, once Nick's, hung strangely on his meagre frame. He was absurdly proud of this garment. His outer wear was completed by a black cotton shirt, and the inevitable stiff-brimmed hat, without which no brown youth feels himself a man. Xavier's face wore an expression of blankness verging on idiocy; but he was by no means deficient in cunning. His full name was St. Francois Xavier Zero.

Returning from the pump with the pail of water, as he passed Nick, the big man threw him an idle word or two in Cree. Xavier grinned comprehendingly; and Nick and Albert followed him a little way. Xavier came up close behind Garth; and in passing him, made believe to stumble. Some of the water splashed over Garth's legs. Garth swung around, and took in the situation at a glance; Grylls and Albert were grinning in the background. There was a crack as his fist met the half-breed's jaw; and Xavier rolled in the dust. In falling the pail capsized, emptying its contents on the cherished trousers.

Nick's guffaw was quickly changed for a scowl; Garth saw that an explosion was imminent; and that quick thought was necessary. He knew he must at all cost to his pride avoid trouble until he got Natalie off his hands. He walked over to Nick; the big fellow clenched his fists as he approached.

"Hope I haven't hurt the beggar," said Garth blandly. "Perhaps he didn't mean to spill the water; but you have to deal quickly with a breed. That's your way, I'm told."

Nick was completely disconcerted by this unexpected line of action. His hands dropped; and he muttered something which might pass for agreement. Garth coolly returned to Natalie.

The breed picked himself up, and went crouching to his master with a voluble, whining complaint in his own tongue. Nick lifted his hand; and with a vicious, backhanded stroke sent Xavier again reeling across the yard. It was the blow which was meant for Garth. Passion had set Nick dancing to a strange tune. Albert, seeing the look in his eye, instinctively edged out of reach.

Old Nell looked at these things with a resigned air that spoke volumes for her daily life. Natalie kept perfectly quiet; but a bright spot burned in either cheek, and she turned a pair of shining eyes on Garth when he came back to her. His difficulties were by no means over. Old Paul, feeling that it might be well to forego the pail of water, gave the word to start. Grylls climbed in by the rear step, and sat next to Nell with a dogged air. This brought him opposite Garth, and very near Natalie. Albert and the half-breed following him, they started. Xavier, covered with dirt, snivelling, and nursing a split lip, was as ugly as a gargoyle.

Garth saw a way out in the vacant place beside Paul. "The front seat would be more comfortable for you; it's wider," he said to Natalie, loud enough for all to hear. "Paul," he called, "have you room beside you for the young lady? She wants to hear some more stories."

Paul, delighted, immediately pulled up, and held out a hand. Natalie climbed over the mail-bags and took her place beside him. In crossing, she gave Garth's hand a grateful squeeze; and he returned to his place with a swelling heart, ready for Nick Grylls and any like him. But he would not allow himself to depart from the course he had laid out. In the past he had been compelled to conciliate, to flatter, to mould such men as Grylls for the advantage of the Leader; and he could certainly do it once more for the sake of Natalie. Nick faced him with a venomous eye, but was unable to make an opening for more trouble.

Old Paul, whenever they came to a hill and he could allow his four to walk, turned around; and half to Natalie, half to Garth, delivered himself of one of his characteristic stories. Neither was Nick impatient with his monologues to-day; for when Paul turned Natalie half turned also; and then Nick could watch her face.

Garth had asked the old man about the half-breed rebellion.

"Sure, I was through it all," he began. "I was buildin' boats in Prince George; and scoutin'. Upwards of three months we hadn't no news from outside and the settlement was in a continuous state of scare. It was supposed the Crees had been joined by the Montana Indians; and all said we was cut off on the south. Women, children and cattle was crowded together in the stockade; but I didn't bring my family in. My old woman weren't afraid; and somepin' told me it was just one of these here panics like.

"Well, one day up came word to the commandant to send a force down the river to Fort Pitt, as they called it, to jine with General Middleton. Then it was Smiley here, and Smiley there, and they couldn't do nothin' without Smiley. I started down the river at last with two work boats carryin' fifty men under Major Lewis and Cap'n Caswell. It was a Saturday night, I mind. Lewis was one of these stuck-up, know-it-all johnnies, not long breeched. But Caswell was an old Crimea veteran; his face had been spiled by a powder explosion; but he certainly was a sporter! Me and him got along fine. My! My! what a randy old feller he was! The men used to sit around him with their mouths open waitin' to laugh. Grimy Caswell they called him, along of his speckled face—great big man!

"We travelled for three days and three nights without stoppin'; and would you believe it, that damn fool Lewis—'scuse me, Miss—made us light a lantern at night! A mark for all the reds in the country! I was steerin' the first boat; and signallin' the channel to Dave Sinclair in the boat behind, with my hand; this way and so. But the second day Dave ran her aground. Young Lewis wouldn't allow that we knew how to lift a boat off a shoal up North. I let him break all the ropes tryin' to drag her off; then I showed him. Meanwhile, all this time, Grimy Caswell was dressin' himself up like a redskin in my boat; and smearin' his face with red earth. When it got dusk-like, he hid in the bushes; and by and by Lewis came along the shore. All of a sudden, Grimy in his war-paint popped out in front of him, let out a hell of a screech, and sent a shot over his head. Say, that young man near died right there. He turned the colour of a lead bullet; and made some quick tracks to the rear boat. Grimy sneaked back to ours and washed and dressed; and all night long he plagued Lewis to light the lantern; but he wouldn't; and the men near died holdin' theirselves in. Oh! Grimy Caswell was a humorous feller, he was!

"We landed at Fort Pitt on the fourth day; and at the same time the steamboats come up from Battle Run with the whole army. They landed 'em all; and say, they had a brass band; and General Middleton rode a white horse. Never see such a grand sight in all my born days; they must have been all of seven hundred and fifty men!"

At the foot of another long hill Natalie expressed a wish to walk up; and Garth helped her down. They set off briskly, ahead of the horses; and for the first time found themselves free to talk to each other.

"How good you have been to me!" she murmured.

"Don't think of thanking me," said Garth, almost roughly.

"If I had known how literally you would have to take care of me, I would not have been so quick to ask you."

"It was nothing, really."

"Nothing, you mean to what is before us?" she asked quickly.

"I look for nothing worse," he said.

"Perhaps my appearance is too conspicuous," she suggested with a humility new to her.

"A little, perhaps," Garth admitted.

"What shall I do?" she said. "I have nothing else."

"At the Landing I will dress you in a rough sweater, and a felt hat strapped under your chin," he said with a smile.

Natalie was aggrieved. "I like to look nice," she protested.

"You would—even then," said poor Garth.

She changed the subject. "What a gross beast that big man is!" she said strongly.

"Poor devil!" said Garth unconsciously. He understood from his own feelings a little of what Nick was going through.

Natalie turned a surprised face on him. "Are you sorry for him?" she demanded.

"A little."

"Why?"

"Well—I think perhaps he never saw any one like you before," he said quietly.

"But he hates you!"

"Naturally!"

"Why?" she demanded again—and was immediately sorry she had spoken.

Garth looked away. "He thinks I am—I am more than I am," he said oracularly.

She affected not to hear this. "What shall we do about him?" she asked.

"He won't trouble us after the Landing," said Garth. "He is bound down the river to Lake Miwasa, while we go up to Caribou Lake."

"It's a precious good thing for me I didn't start off alone," she said feelingly.

"I'm glad if I've won your confidence a little," said Garth hanging his head.

This meant: "Aren't you going to tell me about yourself?" Natalie's mystery had been a thorn in his flesh all the way along the road. He was ashamed to speak of it, for seeming to imply a doubt of her; but he couldn't help approaching it in this roundabout way.

Natalie understood. "I'll tell you now, gladly," she said at once. "But not here; there isn't time. We have to get in directly."

This was precisely what Garth desired her to say. He longed for her to want to tell him; but for the story itself, he dreaded it, and was quite willing to have the telling deferred.

Later in the day they reached Nell's house, quite a fine edifice built with lumber instead of the usual logs. Natalie, true to her word, allowed herself to be shown through; and did not stint her admiration of Nell's treasures. When they drove on, she looked back with a genuine feeling for the old girl, who was so anxious to please. They left her standing in the doorway in her finery, with the sullen, black-browed bravo slouching beside her.

The way became very much rougher; and Garth was glad of Natalie's having greater comfort on the front seat. About five o'clock they climbed their last hill. At the top Old Paul, pulling up his horses, swept his whip with an eloquent gesture over the magnificent prospect lying below.

"All the water this side goes to the Arctic," he said.

Looking over a wealth of greenery, away below them they saw the mighty Miwasa River coming eastward from the mountains, make its southernmost sweep, and shape a course straight away for the North. The Miwasa river! There was magic in the name; they gazed down at it with a feeling akin to awe. Off to the left lay the roofs of the Landing, farthest outpost of civilization.

Presently they were rattling down the steep village street at a great pace, traces hanging slack; past the factor's house, the "Company's" store, the blacksmith shop and the "French outfit"; with a dash and a clatter that brought every inhabitant running to the hotel. Most of them were already there; for the arrival of the mail is the event of the week. Old Smiley swept up to the gallery at Trudeau's with a flourish worthy of coaching's palmiest days. The passengers alighted; and again the girl with the green wings in her hat became the cynosure of every eye. Garth delivered her into the comfortable arms of Mrs. Trudeau, who took her upstairs. Turning back into the general room, he asked the first man he met where the Bishop lived.

"Up the street and to the left a piece," was the reply. "But say—"

"Well?" said Garth.

"The Bishop and his party started up the river two days ago."

Garth, turning, saw Nick Grylls listening with an evil grin.

MIWASA LANDING is the jumping-off place of civilization; here, at Trudeau's, is the last billiard table, and the last piano; here, the wayfarer sleeps for the last time on springs, and eats his last "square" ere the wilderness swallows him. It is at once the rendezvous, the place of good-byes, and the gossip-exchange of the North; here, the incomer first apprehends the intimate, village spirit of that vast land, where a man's doings are registered with more particularity than in the smallest hamlet outside. For where there are not, in half a million square miles, enough white men to fill a room, or as many white women as a man has fingers, each individual fills a large space in the picture. Away up in Fort Somervell, three months' journey from Prince George, they speak of "town" as if it were five miles off.

And Trudeau's on the river bank, quite imposing with its three stories and its gingerbread gallery, is the nucleus of it all. Trudeau's is a reminder of the jolly bustling inns of a century ago. The traders, the policemen, the mail-carriers, the rivermen and the freighters come and go; each sits for a day or two in the row of chairs tipped back against the wall—for no one is ever in a hurry in the North—gives his news, if he be on the way "out"; takes it if he be coming "in"; and appoints to meet his friends there next year. The commonest type of all is the genial dilettante, the man who traps a little, prospects a little, grows a few potatoes, and loafs a great deal. Trudeau's is also the eddy which sooner or later sucks in the derelicts of the country, sons or brothers of somebody, incredibly unshaven and down at heel; capitalists of bluster and labourers with the tongue.

Such was the crowd that witnessed Natalie's arrival open-mouthed; and such the individuals that fastened themselves in turn on Garth, with the determination of extracting a full explanation of the phenomenon. Garth succeeded in avoiding at the same time giving offense and giving information. But he could not prevent a fine podful of rumours from bursting at the Landing, and scattering seeds broadcast over the North.

He found a letter awaiting him from the Bishop.

"I find," he wrote, "that Captain Jack Dexter's steamboat will be going up the river to the Warehouse in the middle of the week; and as my preparations are completed a day or two earlier than I expected, I am starting on ahead with my outfit. You will probably overtake us in the big river, as we have to track all the way; but should you be delayed, I will go on up the rapids; and will see that a wagon is waiting for you at the Warehouse, to bring you to me at Pierre Toma's house on Musquasepi. This will be more comfortable for you, as all this first part of the journey is tedious up-stream work."

The good man little suspected when he wrote it what a quandary his kindly note would throw Garth into.

After supper, he and Natalie, sitting in the rigid little parlour upstairs, talked it over; while Mademoiselle Trudeau, aged fifteen, sought to entertain them by rendering effete popular songs on the famous piano. From below came the rise and fall of deep-voiced talk, and the incessant click of billiard balls.

Natalie made a picture of adorable perplexity to Garth's eyes as she said: "What would you advise me to do?"

"How can I advise you?" he said, looking away; "I do not know all the circumstances."

"But I can't tell you now," she said appealingly. "Don't you see, my reasons for going must not be allowed to influence our decision as to whether I can go?"

Garth did not exactly see this; but unwilling to beg for her confidence, he remained silent.

"My trouble is," she continued presently, "that if we follow the Bishop and overtake him, he'll virtually be obliged to take me; and I do not wish to force myself on him."

"As to that," Garth said, "one has to give and take in the North. It's not like it is outside. Besides, we pay our own score you know; and carry our own grub. I'll answer for the Bishop."

"Then I see no reason why I should not go," she said.

The journey with her stretched itself rosily before Garth's mind's eye; but his instinct to take care of her made him oppose it. "There is me," he said diffidently; "travelling alone with me, I mean. Even in the North a girl is obliged to consider what people will say."

Natalie shook her shoulders impatiently. "There's not the slightest use urging reasons of propriety," she said resolutely. "As long as my conscience is clear, I can't afford to consider it. This is too important. It affects my whole life," she added in a deeper voice. "There's something up there I have to find out!"

Something in this made Garth's hopes lift up a little; for she did not speak as one whose heart was in thrall.

Mademoiselle Trudeau concluded her piece with an ear-tearing discord; and turned, self-consciously inviting applause.

"How well you play, dear!" said Natalie, the wheedler. "Isn't it nice to have music away up here! Try something else."

The performer, adoring Natalie, promptly turned her pig-tails to them again, and attacked "Two Little Girls in Blue." Garth groaned.

"Discourages listeners," remarked Natalie, indicating the curtained doorway.

"So," she continued presently, "if you haven't any better reasons to urge against it, we'll consider the matter settled."

"Couldn't I go for you?" asked Garth.

She resolutely shook her head. "I have promised," she said.

"It was a promise given in ignorance of the conditions," Garth persisted with rough tenderness. "This wild country is no place for you. I could not bear to see you wet and hungry and cold and tired, and all that is before us—besides dangers we may not suspect."

Natalie faced him with shining eyes. "Clumsy man!" she cried—but there was tenderness in her scorn too. "Do you think this is persuading me not to go? I'm not a doll; I won't spoil with a little rough handling! If you only knew how I longed to experience the real; to work for my living, to get under the surface of things!"

Garth, amazed and admiring of her bold spirit, was silenced.

As they were parting for the night, she said: "As soon as the steamboat casts off, and it's too late to turn back, I will tell you what I have to do up there."