RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

My obsession is Mother Goose rimes.

(Miss Erda Hammill and Miss Betty Buhannon in peignoirs and slippers are discovered toasting marshmallows over the open fire in the pink and white bedroom of the latter young woman. The hands of the clock on the mantel above their heads are about to meet at the top of the face. There is no light but that from the fire. Erda speaks.)

MY brother Corwin says it's an obsession—have you ever noticed how boys

always sprout a crop of big words with their mustaches? It's like this: when

your brain stops working for a moment, and your head is perfectly empty,

before it starts off on a new track something rolls around in it like a pea

on a hot shovel. I knew a girl at college who at such times always found

herself muttering "Fourteen hundred and twenty-nine," and there was another

who said "lehthyosorcerous" over and over. She didn't know what it meant, and

neither do I.

My obsession isn't so silly as that; it's Mother Goose rimes. And really, if you stop to think, there's a lot in Mother Goose. There seems to be a rime to fit every mood. When you're all trembly and jumpy, what could be better than, "Hey diddle diddle, the cat and the fiddle"? And when you're in the dumps doesn't "Three wise men of Gotham went to sea in a bowl" just express it? And when you're filled with that big, solemn feeling of I don't know what, you naturally say slowly, "Fee, fi, fo, fum. I smell the blood of an Englishmun!"

One generally keeps an obsession to oneself, it sounds so silly. But mine helped me out of an awful scrape this summer. Wait till you bear!

I WAS almost engaged to Thomas Bunting, you know. No, I didn't care about him

especially; but I had my plan of life all doped out, as Corwin says, and had

decided not to care for anybody really. You see they all say I'm pretty, and

seem to like me,—I don't think so myself; but I suppose I have my

moments,—so I was just going to be sweet to everybody alike, and not be

bothered myself with any topsy-turvy feelings.

It's true Thomas is so soft you could poke your finger through him; but he was a willing slave. He's tall and loose jointed, and he falls over everything or drops it, and the worst thing about him is, no one ever thinks of calling him Tom. He's a Thomas through and through. But I thought he would do as well as anybody.

I've changed my mind. Men are like marshmallows,—aren't they, Dear?—either like they come out of the box, floury, tasteless, and sticky; or else like this one, properly toasted, a little bitter and crackly on the outside and—oh! sweet underneath.

The Buntings asked me to go for a cruise down Chesapeake Bay in their motor yacht. Of course I knew what this meant. This was to clinch matters. They would have invited the lady in the moon if their darling had cried for her. But I was quite willing to let it happen. I had some lovely yachting clothes.

"It's going to be a picnic, my dear," Mrs. Bunting said to me. "We won't take any servants, I shall do the cooking, Thomas will steer, and we're taking a young man from Mr. Bunting's office who knows all about machinery. He's a gentleman and will be quite one of us," she thought it necessary to add.

Mrs. Bunting, I should tell you, is a dear little old fashioned rolypoly, with her front hair waved and laid down smooth on each side of her forehead. She always has a surprised and scandalized look. Her husband has been poking fun at her for twenty-five years, and she still takes him seriously. She's a little balmy on the subject of her Thomas.

It was great fun getting ready, though Thomas scarcely ever left my side, and when he did his mother would be whispering his praises in my ear, or his father would drop perfectly transparent hints of what he meant to do for Thomas later on. The Lorelei was a love of a boat, and I was to have the cunningest little stateroom!

Everything went well until just before the start from Sparrows Point, when I met the young engineer, and he had a perfectly horrible effect on me. His name was French Straiker. He was the dark, thin kind that looks so well in rough outing clothes. He had a kind of careless, scornful air. I had on my prettiest embroidered dress and my lingerie hat—and he scarcely looked at me! I spent ten minutes there on deck doing my prettiest to old Mr. Bunting, and that French Straiker went on coiling his old ropes the whole time, and never looked around once! I felt like sticking out my tongue at him! He was very good looking, Dearest. He had that hard look that softens only for one girl, you know, and every girl that sees it wants to be it.

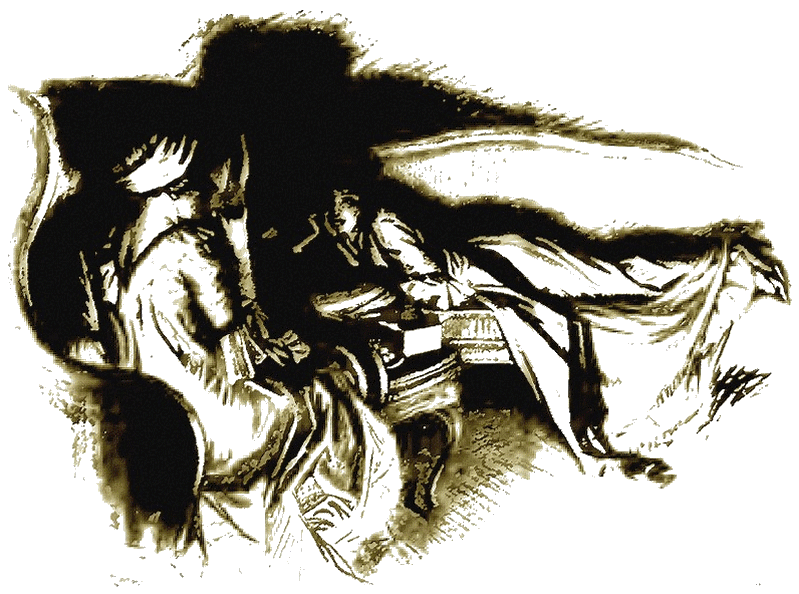

That French Straiker never looked around once!

The strangest part of it was, I instantly began to hate Thomas in the most unreasonable way. His wrinkly white ducks, and his brass buttons, and his yachting cap, and his marine glasses were perfectly ridiculous. His canvas shoes clung to the deck like immense white pancakes. Thomas made calf's eyes, and breathed heavily down the back of my neck—you know the see-how-devoted-I-am kind. Good Heavens! I thought, what will the other one think of a girl who stands for this kind of thing? And I got hot and cold all over and found myself muttering. "Peter, Peter, punkin eater," a sure sign of threatening showers.

I HAD not been on board long before I discovered the only man that knew

anything about boats. Less than a hundred from the dock that silly Thomas, in

his anxiety to show off, ran us smack in the mud. He blamed it on French

Straiker for answering the engine room signals wrong; but it was Thomas who

got the bells mixed up. French Straiker just showed all his white teeth

good-naturedly, and got her off. After that he had to keep one eye on the

engine and one on the steering wheel, or we should have been running into

things all the way down the river.

You see, Dear, the trip started very badly for me, and it went from bad to worse. I had planned to manage everything so sweetly, and here I was quite distracted! I seemed to go all to pieces. I was furious with myself. You know how I always despised girls who had no control over their feelings. But that man always seemed to put me in the wrong. He was exasperatingly right in everything he did. He worked from morning till night; he could even wash dishes without losing his dignity.

The others treated him as something between a friend and a servant; but it never ruffled him. He went about his work looking as if he had pleasant thoughts inside his head that he didn't feel called upon to share with anyone. I didn't know how to act toward him. If I ignored him, I felt like a snob, and if I was friendly I felt as if I was throwing myself at him. At night I used to lie in my bunk thinking of the different kinds of fool I had made of myself during the day. I repeated Mother Goose from end to end to keep from thinking of him; but the moment I fell asleep I started to dream of his handsome, good-humored, scornful face, and would finally wake up weeping. There's a confession for a self respecting girl to make!

Meanwhile, fancy how I was enjoying that overgrown Thomas' lovemaking! Thomas was like liquid glue. In the daytime I kept his mind distracted a good deal by letting him take my photograph. They turned out awful, and I destroyed them, except one that wasn't so bad. It showed me in my white Peter Thompson sitting among the cushions in the stern with an expression as if I had broken my best doll. I let him keep that; but the silly thing lost it, and I wouldn't let him have another.

I dreaded the approach of night. We always laid at anchor in one of the harbors. The old people remained below—to keep out of the dampness, they said—and there was nothing for me to do but sit with Thomas in the stern. Very often French Straiker would be sitting up in the point of the bow with his back to us, strumming on a guitar very softly. That's where my heart was! It was moonlight too.

I used to show Thomas as plainly as I could that I didn't like sitting close or anything; but you couldn't snub him! Talk about rhinoceros hide! Thomas' way with a girl was to make believe in the face of Heaven and earth that she was fond of him, and that a perfect understanding existed between them. What can you do with a man like that, short of making a regular scene? And how could I do that while I was a guest on board their boat?

His conversation was about as interesting as a patent medicine almanac. Thomas used to impart information. It's a wonder I didn't become a gibbering idiot. I used to close my eyes and think over the wonderful brilliance of Mother Goose as compared with Thomas.

ONE night he heard me muttering and asked me to repeat what I said.

I was too far gone to make any pretenses. I just opened my eyes in an innocent stare and murmured:

There was a man in our town.

And he was wondrous wise;

He jumped into a bramble bush

And scratched out both his eyes.

And when he saw his eyes were out,

With all his might and main

He jumped into another bush

And scratched them in again.

Thomas laughed in a constrained way, and tried to take my hand.

I ticked off his fingers. "This little pig went to market; this little pig stayed at home; this little pig had rare roast beef—"

Thomas dropped my hand as if it burnt him. "Can you find the lady in the moon?" he asked foolishly.

Thomas is like a cake that didn't rise, or jelly that refuses to jell. There's something lacking. He became more and more alarmed at my foolishness, and of course I enlarged upon it. Finally I began to talk about insanity in an offhand way.

"It's a funny thing, isn't it?" I asked.

"I am unable to see the joke," said Thomas crushingly.

"But you never know when you're crazy," I went on. "You always think you're a King or something. How jolly!"

"Poor unfortunates!" said Thomas, just like his mother.

"Everybody's crazy," I said, "about something. You knock against the subject accidentally, and—bang! there's an explosion."

"There's never been any in my family," said Thomas severely.

"Of course," I said sweetly. "That explains why you're what you are."

"Oh, I don't know," said Thomas deprecatingly. "Was there ever any in yours?" he asked, very offhand.

Fancy how I jumped at the chance!

"Only my grandfather and two of my aunts," I said carelessly.

Thomas started.

"Isn't it funny? It is said they were always worse by moonlight," I added.

An expression of horror overspread his foolish face, and he moved away a little. I made my eyes big and stared up at the moon.

"I don't see anything unnatural about the cow jumping over it," I murmured.

"I think we'd better go below," said Thomas quickly. "It's getting very damp."

So I was saved for that night! How I hugged myself!

BUT that didn't help matters in the other direction at all. In the mornings

Thomas and his father lay abed late, and I found, if I went up on deck when

Mrs. Bunting was starting breakfast in the galley, I could usually find

French Straiker there. He used to get up at an unearthly hour and go for a

long swim. He was a splendid swimmer. He wouldn't go in with us, I am not so

bad in the water myself; but he never noticed my performances. When I came on

deck his cheeks would be pink and his eyes bright just to be alive in the

early morning. You'll think I'm foolish, Dear, but he made me think of the

shining creatures we imagined at sixteen. He wore his old working clothes as

if they were a suit of armor.

At such moments he was almost human, and would look at me as if I were a person. But at the first approach of any real friendliness between us he would shy like a skittish horse, and then look as if he had been guilty of an awful weakness, making me feel as flat as a paper pattern on the cutting board.

I suppose you'll say it was a judgment on me. In all my life up to that time I had never been denied anything I wanted, consequently I never wanted anything much—and the first thing I did want I couldn't have! By night or day I couldn't think of anything but him. He bothered me to that extent I thought I must surely begin to hate him—but I couldn't. When he was in sight I was unhappy because he didn't notice me; but when he was out of sight I was perfectly wretched because I imagined him writing to some other girl, or looking tenderly at her picture. I was sure he carried some girl's picture in his pocket book, he was so careful of it. How I hated her, whoever she was!

ONE morning when we lay off Solomons Island, Mr. Bunting and Thomas took the little motorboat up to the dockyard to be fixed. Thomas has a perfect genius for getting things out of whack. Mrs. Bunting and I needed some sewing materials, and she asked French Straiker to row me ashore in the dinghy. My heart jumped when I heard her; but unfortunately it was only a few hundred yards away.

He handed me into the dinghy with a face like a polite wooden Indian's. He had his coat over his arm, and as I got in his little pocketbook that was so much in my thoughts slipped out without his seeing it and fell in the bottom of the boat. When I sat down there it lay at my feet, and he had his back turned. Imagine how frightfully tempted I was. But I only poked it a little with my foot. It fell open for a second, and I saw the picture clearly, then it closed again.

Dearest, you know how it is to wake up in the middle of a frightfully ghastly dream and find yourself safe in bed? That is how I felt then. I drew the same long breath of sweetest relief and peacefulness, and said to myself in just the way you do, "It's all right! It's all right! Here I am!" For the picture in that blessed little pocket book was I, the one sitting in the stern of the Lorelei that Thomas had lost! And all the time he was bellowing about his loss, French had quietly hung onto it!

I was so happy the harbor and all the boats seemed to spin round and round, and Mother Goose rimes rang in my head like hymns of joy. No sooner had French sat down to his oars than he saw the pocket hook, and with a sharp look at me pounced on it. But my face was as innocent as a babe's.

I was so happy the harbor seemed to spin round and round.

I found I could look at him now without it hurting me inside. I seemed to

have got myself back again, after having had some crazy girl's head by

mistake. Do you know that rapturous feeling? And of course I wanted to tease

him to pay him back—just a little. And I did! There are so many ways to

tease a man! In spite of his stony face, I knew it hurt. And I was glad.

The next thing I had to do was to solve the mystery. Why did he treat me so, when he was carrying my picture around? Well, I found out, and I learned at the same time that it's not safe to play with a real man—when you care yourself', I mean. He made me very sorry for it.

WHEN we were still at Solomons one night we were asked to a party on another

yacht. At the last moment I developed a headache, and the Buntings were

obliged to go without me. I did have an ache; but it was in my heart—I

already had my fill of teasing French.

After they got safely away I came up on deck. He was in the bow with his guitar. I called him back and made him sit beside me. He didn't try to come close like that idiotic Thomas.

"It was so hot below I couldn't stand it," I said, which was quite true.

For the first time he seemed to have lost his confident air. His eyes looked soft in the moonlight. I had to keep mine hidden for fear of showing too much.

"I'm sorry you're not well," he said awkwardly.

I was as well as well could be then; but I didn't say so.

"Sing something," I said.

He shook his head. "I have no voice tonight," he said in a low tone.

I answered with the obvious thing. "You never do anything to please me!" Saying it to him sounded horribly flat.

"I'll tell you a story," he said, putting down the guitar.

"With lots of adventures?" I said. I didn't want to be flippant; but I couldn't help it.

He shook his head again. "This is a problem story," he said, "and you must supply the answer."

My heart began to beat like anything; for I guessed he was going to talk about us.

"Once upon a time there was a fellow," he began, "and he was as poor as Job's turkey—"

"Good!" I said. "I like to have the hero poor in the beginning."

"This isn't a hero," he said quickly; "an ordinary sort of fellow. He was so poor he couldn't give himself a decent education. And there was a rich man came along and offered to lend him the money to go through college, without any security. You see, the fellow couldn't work himself through, because he was taking a four years' course in two years, and he had to study night and day."

Dearest, he was so nice, so manly and modest and tender! I was just longing to squeeze his hand or something, and instead there I was making frivolous remarks!

"The fellow wanted an education more than anything else in the world," he went on, "and so he was mighty grateful to the man, and he swore to himself that he would pay off the debt of gratitude as well as the money. After he graduated he went to work for the man, paying him little by little, and everything went along all right until a girl came along—"

"Was she pretty?" I asked.

"Yes," he said very low, "lovely enough to make the fellow's head swim; lovely enough to make him forget his gratitude to the man, and everything else in the world!"

Fancy how sweet this was for me to hear! "Go on!" I said breathlessly.

"The man's son was in love with the girl, you see, and the man's heart was set on their getting married. In the circumstances the fellow's duty was plain—hands off! But he was taken by surprise. You see, he'd had to work so hard that girls had no part in his life up to that time, and he didn't know how to resist them. He was obliged to see her every day, and little by little he found himself caving in—though he despised himself for it."

"Didn't he ever happen to think about the girl?" I demanded indignantly.

"Yes," he said. "As long as he thought she was in love with the man's son, it was easy to keep his own feelings under; but by and by he began to suspect that she wasn't—"

"Well?" I said, as he stopped.

"There you have the problem," he said. "Should the fellow tell the girl—or should he go on keeping it to himself?"

My heart beat so loud I thought he must hear it. What was I to say? I wanted him so; but I was furious at him too! I wasn't going to give in so long as his conscience was troubling him.

"It was for him to decide," I said sharply; "not her."

He hung his head a little. "Suppose he'd got to the end of his rope," he said, "and wasn't able to think any more about what was the right thing to do?"

It was so strange and sweet to see his stiff neck humbled at last! I just longed to throw my two arms around it. But he had put it up to me. I couldn't run the risk of having him feel sorry the next day. I finally got it out.

"The right thing for him to do was to keep it to himself."

How I hoped he wouldn't obey me! But he did.

"Of course that's the answer," he said, raising his head. He picked up the guitar. "It was a stupid story, wasn't it?"

THE next few days were very hard to get through. If he really cared, I never

thought he would give me up so easily; but he was as hard as a rock. He set

his lips and went to work, and never looked at me again. I didn't expect to

be taken at my word—and the cruise was drawing to a close! I was

dreadfully unhappy.

And then I had Thomas on my hands. I don't suppose he was having a very good time, either; but I wasn't caring much about that. Thomas was pulled two ways. On the one hand my eccentricities scared him out of his wits; but on the other hand he had gone too far to back out, and his Father and Mother were waiting to give us their blessing.

FINALLY the last night came around. The Lorelei was lying in West

River, and next day we were to run up to Sparrows Point, and so home. I

thought I would never see French again, and my heart was broken. Also Thomas

was unpleasantly ardent.

The moon was full now. It rose like an immense pale Japanese lantern out of the bay. Thomas and I were in the stern as usual, and French was away up in the bow. He had left the guitar below.

"Our last night!" Thomas began in his most sentimental tones.

I shuddered at what was coming. "Last night the nightingale woke me," I murmured foolishly—that was one of French's songs.

"You're not paying attention," Thomas complained.

"Paying attention!" I said crossly. "My head is going round like a revolving cage with a squirrel in it—and you're not the squirrel," I added under my breath.

"I don't believe it," said Thomas. "You're as sensible as I am."

This was pretty good for Thomas. "Thank you," I said sweetly.

"You're just putting me off!" he whimpered.

"Where?" I asked.

"Oh, Erda, be serious!" he said, trying to take my hand.

"Mustn't," I said. "I'm like poor Aunt Lizzie."

"How?" he asked.

"Aunt Lizzie always said her hands weren't finished and mustn't be disturbed."

But my imaginary Aunt Lizzie had lost her terrors. "I don't care if your whole family was crazy!" Thomas blurted out.

I got up and walked to the end of the rail. I should explain that the after deck of the Lorelei was encircled by a stout rail. It ended amidships, and there was a place there by the davits where you could step right off.

I stood there hanging to the rail looking off at the moonlight on the water. Did you ever, when you were bothered about something and couldn't sleep, try imagining yourself floating in calm, cool water? Try it sometime, and see how quickly you fall asleep. I thought of that then. There were all my troubles pressing on me, and at my feet the delicious water. The river was as smooth as oil, and its surface had a lovely dusty effect in the moonlight. Besides, I had been in only once that day and my dress was ready for the wash.

Thomas came up and tried to put his arm around me. He was so clumsy. "I'm going to kiss you!" he said.

I felt it coming like a hot blast over desert. I had already slipped my feet out of my best white pumps. I just stepped off.

I stiffened my body and went straight down. The embrace of the water charmed away all my troubles. When I came up I could have sung for joy. I struck out for the moon.

BEHIND me I heard a cry and a splash like a cow falling in, and I knew Thomas

was after me. Poor Thomas! He hated the water at night. Then I heard a clean

cut splash like a round stone dropping in. I knew French had dived. I had no

doubt about which one would catch me first. He soon came up.

"Are you all right?" he asked anxiously.

"Sure!" I said. I couldn't think of anything romantic.

"Put your hand on my shoulder, if you're tired," he said.

I wasn't; but I put it there. He turned his head and kissed it.

"Where are we going?" he asked.

"To the moon!" I said.

He understood. "Good old water! Good old moon!" he cried.

We swam for a little while, and then we heard a frightened cry behind us.

"By gad! I forgot Thomas!" French cried.

So had I. We turned and raced back. Halfway to the Lorelei we came upon him floundering and gasping, just about all in. French took him under one arm, I under the other, and we shoved him back to the ladder like two tugs with a waterlogged barge. There his terrified father and mother hauled him aboard.

"My hero!" cried his mother.

French and I loitered in the water. It was so beautiful we couldn't bear to go in. His arm came stealing around me in the most natural way possible, and he caught me to him tight.

"Mermaid!" he whispered. "I just can't keep it to myself! I love you! I love you!"

As for me, I just kissed him on his strong brown neck.

Fancy! That was the picture that met the eyes of Mr. and Mrs. Bunting when they came rushing back to pull me out. Their eyes almost popped out of their heads. Goodness! what a moment!

My dear, when we got on deck there was the most dreadful scene! Everybody—but French—talked at once, and no one paid the least attention to what anyone else said. Mrs. Bunting wept, and the old man used language. The two of them joined in calling my poor French the worst names they could lay their tongues to,—"Ingrate! Upstart!" and so on like that. The old man discharged French about five times in a minute. I tried my best to explain; but I couldn't make myself heard. French took it all in silence, looking adorably pale and dangerous.

As for Thomas—you would have died if you could have seen him! There he stood with his hair in his eyes, and his clothes clinging to him, full to the brim with salt water, very groggy, very dignified and trying his best to look like a hero. When he got through his muddled head what had happened, he pulled me aside. He had a desperate, foolish expression like a clown.

"Erda, you—you can't care about this fellow!" he spluttered.

My dear, I can tell you about it now calmly enough; but at the time, with everybody going at once, I lost my head completely. I didn't know what I was saying. I found myself murmuring slowly:

Hickory, dickory dock,

The mouse ran up the clock;

The clock struck one.

And down it run;

Hickory, dickory, dock!

"There's a mistake in grammar, isn't there?" I asked wildly.

Thomas shrank from me as if I had the plague. He turned to his father and mother, who were still abusing poor French.

"Stop!" he said hurriedly. "'It's all right!"

They turned to him in amazement. Thomas put on a grand air—and him dripping wet, my dear! "I have given up my pretension to the hand of Miss Hammill," he said. "Let French go in and win if he can."

"But, Thomas!" cried his father and mother together.

"Let us say no more about it," said Thomas. "I have changed my mind. I will explain in private."

Mr. Bunting shrugged, and curtly begged French's pardon. Mrs. Bunting was more firmly convinced than ever that her Thomas was a hero. We went below and changed.

That's about all, Dear. The funniest thing was Mrs. Bunting's scared and pitying manner toward me, after Thomas had presumably made his explanations. I can hear the dear little lady saying to her friends as she casts up her eyes, "What a narrow escape for dear Thomas!"

We landed at Sparrows Point next day, and I have not seen the Buntings since. Mr. Bunting has made it all right with French—I expect he needs him in the business... Isn't it a love of a ring?... The dear boy!