RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

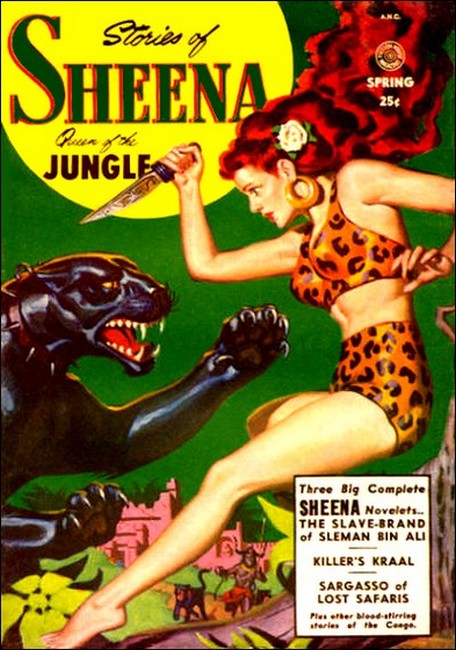

Rain had forsaken the Congo. Hunger stalked the land. And lean, ravenous Abama warriors led by the Golden Goddess of all the Jungle—Sheena—marched doggedly against the walls of mighty Kilma to bury the ancient curse of Sleman bin Ali.

SHEENA stepped out of the pool. She shook out the wet veil of her golden hair and stood, statuesque, her bronzed beauty glowing in a shaft of amber sunlight. The warm ray caressed her, and swiftly drank the moisture from the shimmering veil. Then she flashed across the little clearing to the hut which stood on stilts, five feet above the crawling earth. Quickly she shrugged into leopard skin, and then came to stand in the doorway of the hut, looking out across the pool.

How still it was on these idle days under the thatched eaves of the little house. The pale fruit hung high on the ajap tree before the door, and, higher still, Chim, her pet ape, swung from branch to branch, performing amazing gymnastic feats, and scolding because she did not laugh and shout her approval. The twelve-hour tyranny of the sun was at its ebb, its violence done to the yellow earth of the clearing, and the arras of the forest hung breathless over its secret; for here, deep in the African Congo, was the holy dwelling place of Sheena, the Golden Goddess of the Jungle and all its tribesmen. Here no man had ever set foot, not even those whose escutcheon was white skin and who boasted the title, Bwana. Wise men knew better than to flaunt tribal taboos, and fools die quickly on the forbidden trails of the Congo jungle.

The rainy season was overdue, the heat oppressive in the little clearing even after sundown. Lightning flashed around the horizon, the thunder rolled like distant drums, and all nature waited in breathless suspense. But no rain fell and, though Sheena knew that it must make her forest home damp and depressing, she longed for it to come and break this brooding stillness, this tense waiting for something to happen.

It was a strange, new feeling that had beset her in this season, a feeling that incessantly grew out of her inner heart. She could no longer believe that it was entirely due to the weather. It was linked with the young trader who had come up to the Kuango post as surely as it was linked with his black, bearded companion.

Though no white man had set eyes upon Sheena, not one who came into her domain escaped her scrutiny. Always she liked to look closely into their faces when sleep had removed the mask of consciousness and showed the naked soul. Through their camps she stole, like a ghost in the dead of night. The trader, the hunter, explorer and missionary—she knew them all. Some were wise in the ways of exile, and came and went their ways; others went into the forest with a backward look, and came out with secret and stricken countenance. Sometimes one or another lingered too long in the jungle, and then, as the Abamas said: "He sent his heart into the dark," and built out of his lonely horror and the license of solitude a perverse habitation for his soul. Such men were dangerous, as deadly as the mamba.

And such a man was the Black-Bearded One, with gold rings in his ears. An evil face was his, with a cruel twist to the mouth even in repose. But the young one, flung out on his canvas cot, bronzed chest and muscular limbs thinly veiled by mosquito netting, had not been hard to look at. Black curls against the white of his pillow, a strong face softened by some dream that made him smile in his sleep. Not so tall, perhaps, as Ekoti, chief of the Abamas, but then Ekoti was a giant of a man.

WAS IT the evil she had seen in the face of the one, or was it the disturbing which came when she thought of the other, that kept her in idleness beside this jungle pool?

She could not tell. The uncertainty made her moody and reawakened in her a craving for the trails long familiar to her—the trails that ever coiled and wound mysteriously around the mountains, down into the valleys, and through the dark forest. Chim dropped to the ground and then bounced up onto the floor beside her. She ran her hand through his black hair, and spoke softly what was in her mind:

"Soon the rain must come, little one. Tomorrow we will leave this place for the cave in the mountains."

Chim grimaced at her. They had never stayed in this place for so long before. He sensed his mistress' moodiness, and it made him feel bad. He could not keep still. He swung up into the ajap tree again, and sat scolding her in his comical way.

The sun sank behind the mountains, and shadows overflowed the clearing. The surrounding jungle was windless, yet full of hurried noises, and the sweet, lingering song of the bush cuckoos. Soon the drums, in the deep, absorbing silence of the forest so like the clicking of a giant telegraph, began to talk. At this hour, everywhere, the villages gave ear to the gossip of the jungle.

The drums were not of equal power, nor were their voices more alike than the voices of people are. Sheena never failed to locate a drum by its voice. In the old, primeval code all the facts of life had their phrases, all the adventures and misadventures of the day, their announcements; and no sovereign, despite the white man's magic, knew more of the hopes and fears of his people, or knew them sooner, than did Sheena, Queen of the Jungle.

"Your wife has borne a son!" one drum said. And somewhere on the veldt, or deep in the forest, a lone hunter paused to build a ritual fire, and give thanks to his gods. Then out of the darkness, as swift as an arrow aimed at her heart, Sheena heard her own name, her own drum name, and coupled with it was this phrase:

"Aku is dead. The Bearded One killed him. Come, cross his hands on his breast!"

And then there was a crying in the wilderness as one drum, and then another, and another, sobbed out the old, poignant call to mourning.

Under the immediate thrust of it all life in the clearing seemed to be arrested, and Sheena's heart was like a cold stone in her breast. Then, suddenly, she jumped to her feet, her hands clenched, her blue eyes blazing. So, they had dared to kill one of her people, a hunter brave and good. This was the thing her un-quiet spirit had tried to warn her against. But she had not listened to the small voice within her. She had seen the evil in the face of the Bearded One, yet she had not sent Ekoti and his warriors to drive him out. No, she had not done that, because—because, in her heart there lurked a hidden wish to talk with the young one! Ah, but she was not deaf to the small voice now. Let the white men beware, soon they would meet Sheena face to face!

From a peg above her bed she snatched her quiver and bow; then sped down the moon-dappled trail to the Abama village, as light as dust, as swift as a cloud shadow over the veldt. From his perch in the ajap tree Chim saw her flash down the trail, and shrieked out his protest. To keep off the jungle trails at night was just plain monkey-sense.

At sunrise Sheena stood on a rocky eminence, looking toward the distant mountains, a superb figure with her hair streaming out in the hot wind from the south-east. The rippling veldt ran out to the foothills, and there were dark pools of shadow under the euphorbia trees which pointed milky-jade fingers against the serene blue of the sky. But Sheena looked upon the familiar panorama, frowning, undeceived by its beauty. The creeks that wiggled across the plain were showing ripples of sun-baked mud, and there was the stench of decaying fish in the wind. The land was drying up under the furnace-heat of the sun, and the blistering wind from the desert. All the game was drifting south—the eland and the zebra in flashing stampede to avoid the lion and the leopard slinking on their flanks. If the rain did not come soon, it would be bad for her people who hunted and pastured their herds on this plain.

In the far distance the huts of the Abama village released smoke to smudge the blue of the sky. Swiftly she sped on.

THE VILLAGE surrounded a hill and straggled along the fast-drying river which looped around it like a great python. Sheena had been born among the Abamas, but not in this village. All she knew of her past had come to her from the lips of old N'bid Ela, the witch-woman of the tribe. And that was so long ago that it was hard to remember what the old woman had said. But sometimes, as now when she drew near to the village, a vivid picture of N'bid Ela would arise in her mind, and she would see the old woman strike the earth with her staff and drone:

"This and I—we are very old! Soon I go to the Black Kloof. Before I go, I have words for you. Your father and your mother were of the Tribe of God. Your skin is white, little one. You, too, are of the Tribe of God, and it is not good for you to play with black children. I will tell the people to build a hut for us in the forest. I will teach you my craft. Then, when I am gone, you will be their mata-yenda, their wise-woman, and they will obey you."

And so it had come to pass. For a long time she had lived in the forest, drinking of N'bid Ela's dark wisdom until she had sucked the fountain dry. And more beautiful and glowing in her youth she grew under the African sun every day. More than once N'bid Ela had taken her to the village on the Day of Testing when the young men of the Abama clans gathered to prove their fitness for war and wedlock. In those contests no man had proved himself swifter on foot, or more deadly in his aim with the spear and the bow. The tale of her prowess and wisdom had been carried from kraal to kraal, so that now there were few village headmen who would have thought to venture upon any undertaking without having first consulted her.

At times she wondered at N'bid Ela's strange words. Since the Abamas called all missionaries Men of the Tribe of God, she supposed that her father had been a missionary. Beyond this she could not think. It was foolish to try, like tugging at a vine to which there was no fruit attached.

No one was moving on the dusty trails that criss-crossed the village. Goats lay panting in the shade of a grove of ironwood trees, and the birds perched above them held their wings fan-wise to catch the air. The mushroom houses, shaggy with the thickest of palm-leaf thatch, crouched under the burden of sunlight, but in the palavar house there was permanent dusk. The sudden glitter of copper ornaments was there, and the glitter of spear heads. Brilliant eyes set in dark faces, fantastic headdresses studded with buttons and shells and beads, The tumult and vehement gestures of controversy were there also—and then silence when Sheena came to stand among them.

Her eyes picked out Ekoti, the young chief of the Abamas. "My ears are open, Ekoti," she said.

"The white men sent a runner to our village," the chief said as he got to his feet, "because they wanted to trade with us. As you know, Sheena, we are great hunters and there is an ivory under every man's bed in this village. It seemed good to me that we should trade some of it for guns. And—"

"Why did you ask for guns?" Sheena interposed sharply.

Ekoti looked around him uneasily, then he took a deep breath and at length: "Nothing can be hidden from Sheena. I want the guns to go against the Arab's town. Long ago he drove our people. He drove our brothers, the M'Bama, stole many of their women and made slaves of their young men. If I think to make war against him, is it a bad thing?"

Sheena gave him a cold-eyed stare. "Perhaps," she said softly, "Ekoti thinks too much of war. Perhaps it is not good for him to be Chief of the Abamas."

A low murmur ran around the circle of elders, and Ekoti looked down at the ground. Not until the Jungle Queen smiled on him again would his grasp on the chieftainship be firm. For a time Sheena kept him in an agony of suspense, then suddenly she smiled:

"It is good for a man to speak his heart even though it betray his folly. Because your chief did this without fear, I am pleased with him. But in your fathers' time the Abamas, like foolish young bulls, rushed against the Arab's walls, and they broke their horns. Even if you had guns, the Arab would be too strong for you, Ekoti. Think no more of war with him. Now, go on with your story."

"I sent my uncle, Aku, with two hands of teeth to the trader's kraal," Ekoti took up his story. "I did this because once Aku was on safari with the Bearded One, and he knows the Swahili speech which the traders use, I sent only as many men as were needed to carry the ivory. Truly, my head was sick when I did that! The Bearded One would not give Aku guns. No, he cheated Aku. He offered only cloth and beads. This made Aku angry because he knew that the trader offered less for ten teeth—big teeth, I say—than a coast trader would give for one." He paused for breath, then went on:

"Then Aku would have left the trader's kraal, but the Bearded One would not let his men touch the ivory. There was a fight. The trader drove our people. Aku ran for the bush, but the Bearded One fired his gun and Aku fell. Then the trader's people rushed out and seized five of ours, and took them into their kraal. Aku they took also. Doubtless, he is dead. Doubtless, too, the trader will kill the others if we go against him. Now, we ask you what we should do about this thing." He sat down, and all eyes were turned upon Sheena. She was silent for some time, then:

"Ekoti, you spoke only of the Bearded One. Where was the young Bwana when this evil was done?"

"We do not know, Sheena." He swept out his arm and muscles rippled under his black, satin skin. "All who came back sit here now. And they say that the young, white man was not there."

Sheena's smile came and went quickly. Just for a moment it made her dark eyes shine in the dim light. It was a fleeting glimpse of the real woman behind the taboo which was always before her like a shield. Ekoti saw it and, shrewdly guessing what had prompted it, frowned darkly, and spoke a thought fathered by the wish:

"Perhaps he has gone down the river to the coast."

Sheena shook her head. "The drums would have spoken of it," she said, and then fell silent, her eyes clouded with thought. Minutes passed without a sound but the labored breathing of the old men. Then:

"The trader must be shown that he cannot shoot and cheat our people," she said. "We will drive him."

"Good! Good!" the elders approved in one voice. Only Ekoti looked dubious.

"How can we drive them, Sheena?" he asked. "Their kraal is strong. They have guns. Also, they have five of our people behind their fence."

The Jungle Queen smiled. "You are a warrior, Ekoti, and you have nothing in your head but spears and guns. Hear me now. You have much ivory, also. The Bearded One wants ivory, so you will make a big safari and take all your ivory to his place."

Ekoti's jaw sagged. For a long moment he stared at her in complete bewilderment. At last he gasped out: "Is it in your mind to give him the ivory in trade for our captured ones?"

Sheena laughed softly. "It is in my mind," she said, "to teach him, and you, a lesson, Ekoti. Obey me, and all will be well. Be ready to march at sunrise. Leave your spears behind. Let no man carry more than his knife. I have spoken."

"I hear, and obey," said Ekoti.

At the door of the palavar house she turned suddenly and asked: "Do your wives still sew well, Ekoti?"

"Truly, Sheena."

"Good! I would talk with them now." Wearing an expression of profound puzzlement, Ekoti followed her out into the sunlight.

TOUGH TRADER and hunter that he was, Rick Thorne felt out of his depth in this isolated trading post on the Portuguese side of the Kuango river. It was not the heat, or the loneliness that bothered him—he was used to both. It was Lazaro Pero who had given him a bad case of the jitters. The Portuguese had a hair-trigger temper, and his bald head, inflamed by the African sun, his beady eyes, and his hooked nose combined to give him a predatory look, strongly suggestive of the bald-headed eagles that as a boy Rick had watched circling the buttes in far-off Montana. The worst of it was, he'd been warned against Pero's blind fits of rage before he had left the coast two months ago. And Pero was about through as senior agent up on the Kuango, according to the Chief Factor of the Companhia do Nayanda.

"His record is not good," Freire had told him when he had taken the job. "I will be frank. Senhor Pero has not asked for an assistant but I am sending you up to him. I want to know what is wrong up there, and I expect you to find out. And I will give you fair warning. Look out for yourself, senhor. Watch Pero, he is a devil of a man."

The Chief Factor had made it plain enough that he believed Pero was trading with the Company's goods on his own account. And, certainly, there was much in Pero's talk to justify that suspicion. From the first day of his arrival, it seemed to Rick, Pero had been sounding him out, hinting darkly at some clever scheme he'd worked out, a scheme that would make a bright young fellow who knew how to keep his mouth shut a rich man in a very short time.

And now there was this trouble with the Abamas. Why the devil had he chosen this day to go hunting? If the old Abama headman kicked off, there'd be hell to pay.

The post was quiet now, dozing in the late afternoon heat. The sky was cloudless, a shimmering, cobalt bowl, pouring withering fire down on the red earth of the compound. Pero was lounging in a cane chair, drinking gin.

"Where did you put that fellow?" Rick asked suddenly.

Pero pushed his glass out in the direction of one of the huts that faced the bungalow across the compound. "In there," he answered, and then added callously:

"He will die at sundown. They always do."

A muscle in Rick's jaw tightened, but he said evenly: "We're sitting on a powder keg, senhor. You'd better send those other fellows back to their village before—"

"I heard you the first time!" Pero snapped. "And I tell you again that I am in charge here. I give the orders." He touched the butt of his revolver. "If a black talks back, whip him; if he puts his hand on a weapon, shoot him. That's my rule, and when I give orders I make no distinction between white men and black men. Remember this, senhor, and you will not get hurt."

Rick's mouth was shaped to an oath as he turned on his heel and went into the main room of the bungalow. He went straight to the big medicine chest which stood over against the wall from the door. From it he took out his own first aide kit. When he straightened up Pero was standing in the doorway, his eyes narrowed to slits.

"What are you going to do with that?" he demanded.

"What I can for that poor devil you plugged," Rick told him calmly.

"Holy Saints!" Pero's face became charged with blood. "Did you not hear me tell you to keep away from him?"

Rick put the case down on the floor with slow deliberation. He considered Pero thoughtfully for a moment before he said: "I'm not a doctor, but I took a course in first aide at Luanda. And I'm not going to sit here and let that poor devil die just to please you."

"So!" Pero spat on the floor, then: "Just now I told you that I give the orders here." His hand went down to his holster, and then jerked up as he started back against the wall and froze to it. "Holy Saints!" he gasped.

At the first downward movement of his hand Rick's Colt had flashed from its holster as if by magic. Its muzzle pointed skyward, and the light glinting on its bright metal was reflected by his gray eyes.

"Any cowhand where I come from could teach you gunplay, senhor," he said quietly. "I don't know what you've got against that Abama out there, and I don't know why you blasted him. I do know that you'd better get rid of that gun. If you're packing it when I come back I'll take it to mean that you want to shoot it out."

THE COLT spun on his finger, and plopped snugly back into its holster. He picked up his case and walked across the room. The bravado had been shocked out of Pero. He kept his hands shoulder high and backed out of Rick's path.

The wounded Abama was stretched out on the dirt floor of the hut, with his face turned to the wall. Gently Rick rolled him onto his back and knelt to examine the wound. The native was badly hurt, unconscious. At a glance Rick saw that the deltoid muscle had been torn clean across near the right shoulder joint. The ends of the sinew had contracted, and if the man was to have the use of his right arm again the torn ends of the muscle must be pulled together expertly. It was a job beyond Rick's skill. The Abama groaned and opened his eyes as Rick probed and cleansed the wound. Fear came into his eyes, but faded as Rick patted his shoulder and smiled. Rick made things easier for him with a little opium and, as he bandaged the wound, the native said faintly in Swahili:

"It is hard to die so far from my village, Bwana."

"You will not die," Rick told him. "I will take you downriver to the mission station. What is your name?"

"Aku, Bwana."

"You speak good Swahili, Aku. Perhaps you have traded with Bwana Pero before?"

"Even so. Once I was his headman. I showed him the way to Kilma, the Arab's town."

Rick started so violently that the roll of bandage fell from his hand. He let it roll across the dirt floor, and asked: "You took ivory there, Aku?"

"Oh yes, Bwana! Big teeth we took there."

With a grunt of satisfaction Rick crawled after the roll of bandage. He saw it all now. Pero was selling ivory to Sleman bin Ali who could ship it down the Congo to the Belgian ports without arousing suspicion. He chuckled softly. Sleman bin Ali was a freebooter of the old school. He should have known from the start that if there was a crooked dollar to be made in the Congo the old sinner would be reaching for it. No wonder Pero had not wanted him to talk to Aku! At the thought his face sobered, and he said:

"Let no one know that you have told me this, Aku. You will not leave this place alive if you do." Then he thought that he'd better make sure of it, and he gave Aku a knockout dose of opium. "Rest now," he said. "I will come for you soon."

Pero was sitting on the rail of the verandah when Rick came back. If he had a gun it was nowhere to be seen. He tugged at his beard nervously as Rick came up the steps. Rick dropped into a cane chair and, tilting it back, rolled a cigarette with aggravating slowness.

"Well?" demanded Pero.

"He's got a good chance if he gets proper care. With your permission I'll take him down to Sao Vincente."

Sudden fear came into Pero's eyes. "So—to the mission, eh? What did he tell you?"

Rick shrugged and said, "I doped him, and I'll have to keep him that way until he's over the shock. Besides, what could he tell me? I don't speak his dialect."

A gleam of satisfaction came into Pero's eyes. "Nothing, senhor—nothing!" he said with obvious relief. "I thought that perhaps you would blame me. Well, I am to blame. You see, I am just. I have a heart, too. Take him to Sao Vincente, my friend. Yes, and tell the good fathers that I will pay for everything."

Rick's slow smile quirked the corners of his mouth. "Well, that's generous," he said. "It won't be safe to move for a couple of days, though."

"Do not delay too long, my friend. Holy Saints, I have never known the rain to hold off for so long. In another week there will be enough water in the river to float a canoe, and it may be that you will have to come back on foot."

"Well, I'll have to take that chance," said Rick, frowning. "Right now the trip would kill the poor devil."

"You know best," said Pero. "When you are ready to go take Benji and five of my Swahilis. They know the river and will make a quick trip for you."

Rick was not particularly happy in the choice of Benji. Pero's headman was a civilisado, and his exaggerated idea of the privileges of Portuguese citizenship sometimes pushed him into downright insolence. But he wanted to keep Pero unsuspicious until he had Aku safe in the mission hospital, and raised no objection.

During the two days that followed two things began to worry Rick. One was the vague feeling of uneasiness that Pero's changed attitude gave him. There was something more than the fear of his Colt behind the Portuguese's sudden affability—something he couldn't fathom. The other worry was equally intangible, but so strong in its suggestion of brooding menace that it kept him pacing the verandah of the bungalow for long hours. It was the unnatural silence that had come to the jungle. Not a drum throbbed at night, and not a native came in his canoe to barter his fish on the bamboo float which jutted out into the broad river. The post was isolated, the natives avoiding it as if it were the center of a plague.

On the morning of the third day he stood on the verandah looking upstream. The river was falling, and from the exposed ooze, baking in the sun, came the effluvia of decay and corruption. Beyond the first bend of the river there was no vista, only the unlimited expanse of the jungle, looking more gray than green, without form or perspective, silent, foreboding. The bamboo jetty was still afloat, but he doubted that it would be tomorrow. He decided to leave for Sao Vincente at sundown.

He went into the bungalow to announce his decision to Pero, but before he could get the words out of his mouth a sudden commotion broke out in the compound. Then Benji came running to the verandah steps.

"Safari, Bwana!" he shouted at Pero. "Big safari!"

Both white men ran out onto the verandah and saw many paddles flashing in the sun. Soon the black shapes of a dozen big dugouts could be seen moving rapidly downstream, the beat of a drum timing the rhythmical stroke of the paddles. Strung out in a long, slanting line they came lurching toward the float. As the first canoe slid alongside three big natives leaped out of it. Four others immediately began to pass out the canoe's cargo into the hands of their fellows on the float. In a moment a half-dozen prime tusks lay at their feet. Another canoe shot alongside, and another, and another, and the same process was repeated. Pero's eyes bulged as the pile of coffee-brown tusks grew larger and larger.

"Holy Saints!" he cried out at last. "Not one under forty pounds!" In his excitement he slapped Rick on the back. "Senhor," he exclaimed, "all my life I have dreamed that something like this might happen to me! Ho, Benji! Open the gates! Break out a keg of rum for our guests! Don't stand there gaping, you black scum, jump to it!" Again he slapped Rick's back. "That's the trick of it, senhor, all there is to it! Get 'em dead drunk, treat 'em like hidalgos and they'll trade a prime tusk for a coil of copper wire."

"They'll catch up with you one of these days," Rick told him with a shake of his head.

A long file of blacks was moving up the steep trail to the gates, not all of them shouldered an ivory, but Rick counted thirty-six. He did a little mental arithmetic, and whistled at the total. There was close to a hundred thousand dollars walking up that trail, or he didn't know a prime tusk when he saw one! Then his attention was drawn to the last canoe to reach the float. Four big blacks, one of them a gigantic fellow wearing the headdress of a chief, were lifting something out of it—something sewn up in a hammock of skins. With a puzzled expression he watched the four set the hammock down on the float carefully and run a stout bamboo pole through the lashings looped around it. Then they lifted it shoulder high, and came jogging up the trail.

"What d'you suppose they've got there, Pero?" he wondered. But the Portuguese was out in the compound, driving his crew of Swahilis to work. The doors of the big trade shed were swung open. Soon every man was rolling out kegs, breaking open bales of cloth and stacking them on the shelves that lined three sides of the huge shed. They moved fast under the lash of Pero's tongue and the sting of Benji's cane.

AS THE leading files of the safari passed into the compound Pero came back to the verandah to receive its headman. There was none of the clamor and excitement that usually turned the post into a pandemonium upon the arrival of a caravan. The bearers quietly deposited their ivories on the ground in front of the bungalow; then, as if at an unseen signal, as quietly they all trooped across the compound to form a solid phalanx before the open doors of the trade shed, and stood silently watching the busy, sweating Swahilis within. Observing this maneuver, Rick's eyes widened in sudden alarm. He touched Pero's arm and said quietly:

"We've got trouble. These fellows aren't porters, they're warriors!"

But Pero could not take his eyes from the ivory. "Nonsense!" he muttered. "There's not a spear among them, and—Holy Saints, what is this?" He broke off pointing as Ekoti and his warriors set their burden down at the foot of the verandah steps.

As if in answer to his question the Abama chief drew his knife, and threw a quick look around the compound. Then he ripped open the seam of the skin bundle, and Sheena burst from it, like a gorgeous butterfly from its chrysalis.

Bow in hand, poised to draw and shoot, she faced the two dumbfounded white men. At a nod of her golden head, Ekoti bellowed out a command. The Abamas near the shed dashed forward, threw their weight against the doors and swung them shut, trapping every man the post could muster within.

Sheena's blonde beauty held Rick spellbound. Pero was the first to recover from the shock of it all. He gasped:

"A raid! Your gun, senhor! Holy Saints—" He started to run for the door of the bungalow, evidently with his own gun in mind.

"Hold!" said Sheena, in a clear ringing voice. At the same instant her bow twanged. The arrow plunged into the door post just ahead of Pero, and he pulled up with his hooked nose touching the quivering shaft.

"Be still!" commanded the Jungle Queen. With her eyes fixed on the young trader she notched another arrow. He appeared to be shaking the stupefaction that had taken possession. He passed his hand before his eyes, shook his head, and muttered something in a tongue she did not know. He was almost as tall as Ekoti, and his eyes were very bold when open. There was no fear in them, but something else was there—a gleam that pleased her and yet made it hard to give him stare for stare. He seemed to sense her discomfiture; for a slow smile came to his lips, and he said in Swahili:

"Lady, I have seen many strange things, but never a thing as strange as your coming—or a thing as beautiful as I see now. It cannot be that you have come to steal like a bushman."

"Why like a bushman?" she flashed at him. "Why not like a white trader? They are the great thieves. Your friend has killed one of my people, and he has taken five others. I know that you were not here when this was done, and that is well for you, Brass Eyes!" She shifted her gaze to the Bearded One, and her blue eyes snapped at him. "Are you as ready to die as you are to kill?" she asked.

He made a queer animal noise in his throat, and his fear oozed out of him like a smelly sweat. His eyes darted frantically around the compound, but could find no way of escape. He could not speak, so great was his fear; and his eyes held the dumb pleading look of a sick dog when he turned them on his young companion. Brass Eyes spoke for him:

"Aku is not dead, Lady. This man has done evil, but he is sorry for it. Is it not the custom of these—of your people to hold a palavar when a wrong has been done to them? My friend is willing to talk, to pay whatever you ask."

Sheena regarded him steadily for a time. He was not afraid, this one, and it was only fear that made men lie.

"Where is Aku?" she demanded.

He pointed to one of the huts. And, at a nod of her head, Ekoti sped across the compound to it. Not a word was spoken until he returned.

"He speaks the truth, Sheena," Ekoti reported in a low voice. "Aku speaks well of the young Bwana. There is some trouble between him and the other, but Aku does not know what it is."

"Good!" said Sheena. "Seize the Bearded One, and then search all the huts for guns."

The Bearded One shrank back as Ekoti mounted the verandah steps, and the young one looked as if he would show fight. She laughed softly, and then said: "Be still, Brass Eyes. We are too many for you, and it is no longer in my mind to kill your friend. We will talk now, you and I."

Pero yelped as Ekoti took hold of him. He struggled trying to pull away from the Abama chief's iron grasp.

"Senhor!" he appealed to Rick. "Help me—Holy Saints, you cannot let this she-devil—"

"Better go quietly, Pero," Rick told him. "You've been asking for something like this for—"

"Speak Swahili!" Sheena told him sharply.

Then Ekoti lost patience with the twisting and screaming Portuguese. He hit him once, then heaved Pero's limp body over his shoulder like a dead buck. He stepped aside as Sheena came up the steps and went into the bungalow.

The young one followed her in. She was conscious of his eyes. They never left her as she glided across the room and sat in one of the cane chairs. He came to a stand, looking down at her, his gaze disconcertingly warm.

"Lady," he said with his slow smile, "when I saw you first I thought that I was dreaming. Even now I am not sure that I am awake."

"Are women with white skins so strange to you?" She held his gaze as the snake holds the bird's that it will soon devour. And suddenly she knew that she had power over this man, and yet there was a recklessness, a wildness in him that she could not help but see. Here was a spirit as strong and free as her own. She had the power to stir him, even to control him with her smiles, but he would not tremble at her frown as Ekoti did. To make this one her slave she would have to share the burden of his chains.

"Who are you?" he asked in his wonderment. "Where do you come from?"

"I am Sheena. That is enough for you, Brass Eyes."

"BRASS EYES is not my name," he told her, frowning. "I am Richard Thorne, hunter, trader, anything so long as it keeps me on the move. Call me Rick, it will make it easier for me to believe my eyes."

"Rick—Rick," she repeated the name and smiled, then: "It is a little name to give such a big man." Then her face sobered, and she asked: "Tell me why I should not take all the trade goods here and give them to my people? The Bearded One has wronged and cheated them. Would it not be just?"

"No!" he answered promptly. "It would not because the goods do not belong to the Bearded One. Lazaro Pero is his name. The goods belong to the Company I work for, and taking them will do Pero no harm. Listen, Lady—"

"Sheena."

"Well then, Sheena. Now I will tell you about Pero—"

She listened to all he had to say, and liked the deep, resonant tones of his voice. When he stopped talking she was silent, turning it all over in her mind. Suddenly she asked:

"This man you hunt for, he will think well of you if you send all the ivory my people brought in down the river to the coast?"

He gave her a startled look, then his slow smile came. "Truly, he would think well of me," he said. "He would think me a prince among traders."

"Good! Then I will tell Ekoti to make fair trade with you. I do this because of what you will do for Aku."

"I would do it for any man," he said. "We leave at sundown, as I have said." Then his eyes became troubled, and he asked: "What about Pero?"

"Have no fear for him. As you say, it is best to give him up to his own people for punishment. He knows nothing, and Ekoti will make fair trade with him while you are downriver. Also, Ekoti will watch this place until you come back. Do as you will with Pero then. Now, I go." She rose in a swift, lithe movement and moved to the door. He sprang to intercept her.

"Where are you going?" he asked, and caught hold of her arm. "You can't walk in and out of my life like this!"

At the touch of his hand she felt her heart jump, then she stiffened and thrust him back. "Are you weary of life?" she bashed at him. "No man may touch me. If my people saw your hand on me their spears would drink your blood!"

The unexpected strength behind the thrust of her arm had thrown him back several paces, and the look that came to his face was almost funny in its expression of complete astonishment.

"What are—who—what the devil—" He gulped, and stared at her, speechless. She laughed softly, then turned and left him, still staring.

At sundown, from behind a screen of bush, she watched Rick and his men carry Aku down to the river on a mat of woven grass.

When the canoe was an amorphous blur on the yellow water, in a mood compounded of nameless yearnings and a strange feeling of emptiness, she took the trail back to her forest sanctuary.

RICK made good time downriver, arriving at Sao Vincente a little before sundown two days later. The town was typical of the Portuguese frontier—a cluster of flat-roofed, pink-and-whitewashed adobe houses, clinging to the river bank with the indefatigable jungle pushing at them from behind. The mission of Carmelite friars was a stone building with castellated walls, and cool arched corridors shaded by palms.

While Aku was installed in the hospital, Rick chatted with a plump, worldly-looking brother of the order.

"Christian charity is rare in these parts," said the monk. "You have done an act of mercy for which God will reward you, my son."

"Well," smiled Rick, "there are a lot of black marks against me up there, Father. I'll be lucky if I get a cancellation on this. And, by the way, have you ever heard any talk of a white woman—a sort of goddess—up on the Kuango?"

"Oh, yes! The natives are full of such tales. But it is wise to believe in such marvels only when we see them, my son."

"And it is not always wise to talk of the marvels we see, eh, Father?"

"Not if we wish to be thought truthful, my son."

"That's how I figure it," murmured Rick. Then, "Well, I must leave tonight. It is my wish to pay for Aku's care now."

The monk chuckled. "Ah, you are a jewel. Nothing is asked, nothing is expected, but a gift is always thrice blessed," he added as Rick pressed a small bag of coins into his hand. "God go with you, my son!"

The Kuango was falling rapidly now. A few miles above the town Rick, Benji and his four Swahilis were forced to abandon their heavy canoe. They continued the trek on foot, through the scented cedar forest and across the burnt veldt.

Herds of zebra thundered southward, the scent of greener pastures strong in their nostrils. The natives were leaving their villages, trekking for Sao Vincente in anticipation of famine.

Short rations forced Rick to shoot for the pot, and the heat forced him to short, night marches. A trek of no more than three marches under normal conditions dragged out to six, and it was near noon on that day when he marched into the Kuango factory.

The post was deserted. The compound empty.

After the first shock of it was over, Rick soothed the fears of his jabbering Swahilis.

"There has been no fighting, Benji. Bwana Pero must have marched downriver with the ivory."

"Doubtless he has marched with the ivory!" The headman spat on the ground. "But not down to Sao Vincente," he added with a vehemence that caused Rick to give him a sharp look. But the Swahilis were crowding around them with bulging eyes, and he only said:

"Come to the bungalow, Benji. We will talk of this."

Papers littered the floor of the main room, and the storeroom had been rifled. Pero had taken all his small safari could carry, plus the ivory. But there were several cases of canned food left. Also a dozen muskets stood in the rack, and there was powder and shot. Looking around, Rick wondered vaguely why Pero hadn't set fire to the post. He supposed that it was because Pero had wanted to get away quietly without attracting the attention of the native villages. But what had happened to the Abamas and Sheena who had said they would watch the post?

Then a crushing sense of defeat twisted his mouth awry with a grimace of self-deprecation, and drove everything else from his mind. Freire had sent him up to watch Pero, and Pero had walked out of Kuango with a hundred thousand dollars worth of ivory—taken it right from under his nose! He could hear the old timers chuckling over it—"Did you hear about the fast one that dango, Pero, pulled on young Thorne up at Kuango—" No, not that!

No man could make a monkey out of Rick Thorne and get clean away. Anger so intense that it whitened his lips and made his hands shake, swept over him. By thunder, he'd get that ivory back. He'd get it back if he had to turn the Congo jungle upside down and shake it out! He swung around to face Benji.

"You know where Bwana Pero has taken the ivory?"

Benji's insolent eyes became fixed on a square bottle of gin which stood on a table under the window. Rick poured out a brimmer and the headman swallowed it in a gulp.

"Well?" Rick prompted him.

"Bwana," Benji began, "before you came I counted the teeth. Sometimes the number that came in and the number that went downriver was not the same. But when I told Bwana Pero about it he only cursed me for a fool and said I could not count right. Once he flogged me so I spoke of it no more. But I am not stupid, and I have eyes."

"Are they sharp enough to find the road to Kilma, Benji?"

"I know the road, Bwana. But we are only six. What can we do against Sleman bin Ali?"

"I'll think of that when I get there. All I want you to do is show me the road." He unslung his rifle and handed it to Benji. "Is this a good gun?" he asked.

"Oh yes, Bwana!" said Benji, handling the rifle lovingly.

"It is yours, if you show me the road to Kilma. Also, I will give a musket to each of your men, and powder and shot. Will they go?"

"Oh yes! They will march with me. What else can they do?"

"At sundown then, Benji."

"At sundown, Bwana!"

UP IN THE hills, far beyond the village, Sheena paused to listen to an Abama drummer. She frowned as the drum spoke her nadan, and then split into accurate lengths of tumult the quiet of the jungle. In less time than it would have taken to speak the words she knew what had happened to Rick Thorne, knew that he was already two marches beyond the Kuango. Her first reaction was anger, and her wrath was turned against Ekoti who had dared to disobey her, who had failed to watch the post until Rick's return, as she had told him to do. Her next thought was of Rick. Truly, he was a reckless young fool, yet splendid in his folly marching against Sleman bin Ali and all his guns with only six men!

And Ekoti's fault was hers. She had promised Rick that she would watch the post and his enemy. A fool he surely was, but she could not let him march to his death because of Ekoti's disobedience. It was unthinkable. She must help Rick. But how? She could not overtake him. Another day's march would take him deep into Sleman bin Ali's country. And the half-Arab understood drum-talk, and he would send out men to capture Rick. Well then, Sleman bin Ali had been a thorn in the Abamas side for a long time. Perhaps now was the time to deal with him. Surely there was a way.

She sat down on a rock to think about it and Chim was suddenly quiet. He came to sit beside her, his chin cupped in his hands, imitating his mistress' pose—a grotesque caricature of blonde beauty wrapped in thought.

It was a long time before Sheena's eyes brightened and a faint smile of satisfaction came to her lips. There was a way, there was always a way if she thought about it long enough. But first she must punish Ekoti. With feline grace she rose and spoke to Chim:

"Fill your belly, little one. We must travel far and fast."

When the heat waves slid down to evening and the sunlight lay in broken fragments on the village trails, Sheena's call summoned Ekoti from his hut. Alone in the semi-dark of the palavar house, Sheena confronted him.

"You did not obey me!" she accused him at once.

But Ekoti did not look down at the ground, nor did he squirm under the cold, angry glare of her blue eyes. His face maintained an expression of impassive innocence. And presently he said:

"Do not be angry with me, Sheena. I obeyed. I watched the trader's kraal until I could stay no longer. Four days I watched, but the young Bwana did not come, and—"

"Why did you leave? Why?" the furious girl demanded.

"Because the game left the country, Sheena. Our cooking pots were empty. We are hunters. We must follow the game. Soon I must lead my people south because of this. We cannot stay in this place. Turn your anger against the Arogi, against the witches who hold back the rain. Am I to be blamed for what they do?"

There was a long pause, and then a deep sigh of relief came from Ekoti's lips as he saw the angry light in the Jungle Queen's eyes slowly fade.

"You are not to be blamed," she said. And Ekoti's strong, filed teeth flashed in a broad grin. "Now I will speak of another thing," she went on. "Tomorrow we march south against the Arab's town."

The grin faded from Ekoti's face and his expression settled into one of utter bewilderment. Presently he gave tongue to it: "It is a thing unheard of!"

"Are you afraid, Ekoti?"

"No!" roared the exasperated chief. "I do not fear the Arab, and well you know it! But when I would have gone against him with guns you called it foolish. And now you would go against him with spears. And at such a time."

"Have I said that I will go against him with spears only?"

"Truly, you did not say so. But without guns or spears the thing cannot be done."

"Do not say of the ajap tree in fruit," she told him quietly, "that it bears nothing but leaves. Did you not think the same thing when I said I would drive the Bearded One? Do as I say now and all will be well."

Ekoti was silent for a long time, his face set in grave lines; then: "Always the Abamas have obeyed you Sheena. It is well for us to obey. We would be nothing without you, our enemies would have eaten us up long ago. We will obey you now. But for my people I ask why we must do this thing?"

"Because Sleman bin Ali is our enemy, and because I fear that he will do harm to the young Bwana who is our friend."

"Aie, aie!" rumbled Ekoti. "It is as I thought. I think back to the village where we were born, Sheena. My heart sings at the memory of the days when we played together, and learned to shoot with the bow. Aie, they were good days! I speak of them now because there is a thing that troubles my mind, and when I say what is in my mind I know that it will make you angry."

"Truly, they were good days, Ekoti. I have not forgotten them. Speak and do not fear my anger."

A dubious smile changed the young chief's eyes. Then, as when a man is about to plunge into a cold, mountain stream, he took a deep breath and said, "I speak of a thing I saw in the young Bwana's eyes when he looked at you, Sheena. If we find him alive it will be a good thing for him to leave this country."

"So!" Her blue eyes kindled.

"Even so, because if he tries to take you away the Abamas will kill him. They would do so because they love you, also because of the taboo of N'bid Ela. It is strong magic. Even stronger than you, Sheena. You could not save the young Bwana if my people thought that you would go away with him." And, having spoken his mind like a man, Ekoti braced himself, as if he expected the roof of the palavar house to fall on his head.

But the storm did not break. No one knew better than Sheena the fatal power of imagination working through superstitious fear. It was taboo that gave her the power to command. And something more she had. The love of these simple jungle folk who, during her helpless infancy, had cherished her as one of their own. Never had she felt the sting of a blow, never an unkind rebuke. Her hand fell lightly on Ekoti's shoulder.

"You have spoken well, Ekoti," she said softly. "Now I tell you: I will leave the Abamas and this forest when the leaves of the majuti trees fall."

The saying caught Ekoti's fancy. He left the palavar house chuckling over it deeply, for no man ever had seen the leaves of a majuti tree fall. It was evergreen.

RICK and his little band toiled upward onto the parklands of the M'bama plateau, following the dry bed of a river that stank like a sewer in the sun. It was undulating country with wild and fantastically broken scenery—deep kloofs and granite kopjies alternating with wooded hills, some densely covered with mimosa bush.

That night Rick's tent was pitched in a little clearing overlooking the south-curving valley of the Simla. The dry spell had reduced even this considerable tributary of the Kuango to a miserable thread of water, meandering through cracks in the sun-baked clay of its bed. Soon cooking fires flared against the black velvet of the night. The silence of the surrounding jungle was compounded of sounds seldom separately recognizable, but for the droning of the cicadas, which came rasping through the aisles of the trees, and gave a knife edge to the heat.

When the late meal was over Benji left his companions and came to squat at Rick's fire. Rick watched him fill his wide nostrils with snuff, his eyes narrowed with thought. From little things Benji had let drop, Rick had drawn the conclusion his headman knew more of Pero's activities than he chose to tell. Moreover, he suspected that Benji was working toward some dark end of his own, or he surely would have quit after the first day of this hard, dry trek.

"Kilma is one day's march from here, Bwana," Benji announced suddenly. "Its chief is a half-Arab called Sleman bin Ali."

"That I know," said Rick.

"In the old days," Benji went on as if he had not heard Rick, "Sleman bin Ali came into this country with a big caravan. A Zanzibari merchant sent him, but Sleman did not come back with ivory, or with the merchant's goods. No, he drove the M'bamas who lived here. He killed many and made slaves of others. Then he made them build Kilma, and he made himself chief of this country. He has many men and many guns. I tell you this, Bwana, because, now that we are close to his town I wonder what you are going to do."

"You might well wonder," said Rick with a wry smile.

Benji chuckled. "So you have thought of nothing. I wonder, also, what you would do with the ivory if you got it back, Bwana."

"The Company would pay well, Benji."

The headman spat into the fire. "The Company would pat you on the shoulder and say, 'Good boy! Good boy!' I know the Company! Truly, they would not give you as much as we could sell it for across the border at Bampo."

Rick smiled. So that was it! Pero had an apt pupil in Benji. And Benji needed him for something or he would have kept his plans to himself. He said: "First we must get the ivory. How are we to do that?"

Benji grinned insolently. "For half of it I will tell you that."

"You're in bad company, young feller!" Rick told himself. "One gun against five. Better take it slow and easy, shake this jasper down for all he's got." Aloud he said:

"It is agreed, Benji. For half of it."

"Good. You do well to agree, Bwana, as you will see." He leaned forward. "Listen now. When the rain comes and Pero can get porters he will make a caravan and march for Bampo. It is five marches from Kilma, and we—"

"We cannot ambush a caravan with six guns," Rick interposed with quick comprehension.

"True, Bwana. But there is a M'bama village nearby. They do not love Sleman bin Ali. They will make a trap for the caravan if one of the Company's Bwanas tells them to do so. Oh yes, it will be easy—" He broke off suddenly, straightened up, and stood looking from right to left.

"What is it?" asked Rick.

BENJI motioned him to silence. There was a faint rustling sound which might have been taken by a careless ear for the wind passing through the grass. But to Benji's quick ear it was something else. He was reaching for his rifle when flame spurted out of the surrounding darkness.

Benji pitched forward across the fire without a cry. Rick's Colt roared a split second after the report of the musket. He had fired at the flash of the gun, and a yelp and the sound of a body crashing through the bush told him that he had not missed. He flung himself on the ground and rolled out of the firelight. He could see nothing, but there was the rustle of movement all around him. Benji's men stood bathed in the light of their fire, motionless, fearing to move lest a volley be poured into them by the invisible raiders.

Lazaro Pero's voice came harshly out of the blackness. "You are surrounded! Throw down your gun, senhor!"

Rick threw down his gun. Dark shapes crept out of the bush, hemming him in. Pero pushed through them into the pool of firelight. He rolled Benji's body over with his foot, and said:

"I knew this fool would follow me but I did not think you would be so stupid, senhor. Holy Saints, what a man you would be if you were as quick with your brain as you are with your gun. Perhaps you came to shoot it out with me, eh, Senhor Cowboy?"

"All right," said Rick from between clenched teeth. "You can shoot when you damn well please, and—"

"Kill you?" Pero shook his head. "I see no reason to kill you. No, I will take you to Kilma. My good friend Sleman bin Ali will keep you there until I am clear of this cursed country. Then he will send you down to the coast, and you can tell that fat pig, Friere, what happened to his ivory. A good joke on him, eh? I deeply regret that I shall not be there to see his face when you do tell him. Holy Saints!" He slapped his thigh, and laughed until the tears ran down his cheeks.

Rick wondered if it was worth risking a blast from the guns that bristled around him just to hit Pero once.

Pero wiped his eyes with the back of his hand. "And they sent you to watch me," he gasped. "How such people get rich, I do not understand. Ah, but I see that all this is very painful for you, senhor. Forgive me for making a fool of you also. But enough." He gave a sharp order.

His Swahilis closed around Rick. His hands were bound, a rope was looped around his neck. The order to march was given and, cursing fluently, he stumbled through the darkness on the heels of the man who tugged at the rope about his neck.

IT WAS a long weary trek up into the M'bama country. Day after day the Abamas padded their way along the old, tribal trails. Lean, hungry warriors ranged on the flanks of the long, straggling line of old men, women and children, and it was a lucky man who brought in meat for his wife to roast. The game was far south. The villages along their route were deserted, a cluster of huts and gardens with the dry stalks of the guinea-corn crackling in the hot wind, the true forest, a deserted clearing, a stretch of true forest again. In the clearings the sunlight was a river of fire between the walls of the forest. The jungle was not strong but it was close, the way narrow, and broken light and broken color beat up into their eyes, so that the women and children and the old ones were weary after a short time of such going. The pace was slow.

There was corn and cassava to be gleaned from the neglected gardens, but such sop did not sit well in Abama stomachs. They were hunters and warriors, and jilo, the meat hunger, gnawed hard at their bellies.

Far ahead of the main body Sheena, Ekoti and Chim stood on a kopji, overlooking the valley of the Silma.

"It is bad," said Ekoti. "Soon there will be no water. We should follow the game to the lake, I think."

"There is water and meat in Kilma," Sheena told him.

"There are walls and guns at Kilma also," growled Ekoti. "It cannot be that you think the Arab will open his gates to the Abama."

"He will open them," said the Jungle Queen confidently. Suddenly she tensed, peering ahead into the heat haze which danced and shimmered before her, rendering visibility close to zero. A group of vultures wheeled in perfect grace over the painted woods. A copper armband flashed in the sun as she pointed and said:

"See yonder!"

"Aie, meat!" exclaimed Ekoti, uttering the thought uppermost in his mind.

But another thought had flashed into Sheena's mind at first sight of the scavenger birds. With an involuntary cry of mingled fear and anger, she sped down the hillside, her golden hair streaming in the wind behind her. Chim went bounding after her, the Abama chief in his wake. But neither could match the flashing speed of the Jungle Queen. Both were soon left far behind.

At any other time Sheena would have approached the spot with utmost care, knowing well that some beast must have driven the vultures from their obscene feast. But in her fear for Rick, in her anxiety to be rid of it, or to know the worst, she forgot caution and burst suddenly into the clearing. She got a fleeting glimpse of the leopard crouched over the remains of Benji's body, and then spotted, snarling fury came hurtling at her. But in Sheena the incredible swiftness of the feline beast was combined with the intelligence of man, with a brain as swift and clear as a mountain stream. For Sheena knew no fear of man or beast.

Unlike the hunted creatures of the jungle whose survival depends on the split-second response to the impulse of flight, she did not swerve in her stride but launched herself in a dive under the leopard's white belly. The beast struck downward with one paw as it flashed over her. Its razor-edged claws combed her hair, and her quiver of arrows was torn from her right shoulder. The leopard's spring carried it half way across the clearing and, as its forepaws touched the earth, Sheena sprang to her feet and whirled to face it.

The baffled beast crouched, tail lashing the ground, yellow eyes fixed on the blonde goddess in an unwinking glare. Sheena's leopard skin had been ripped from her shoulder. The beast's claws had grazed her flesh, and a thin trickle of blood ran down her exposed right breast. Her bow was in her hand, but her quiver lay on the ground, out of reach. She dared not move, or take her eyes from the half-starved animal which, flat on its belly, was now edging toward her, inch by inch. Her hand slid down to her knife, the leopard's lean flanks quivered, and a snarl bared its fangs as it prepared to spring. And just then Chim came bouncing into the clearing. He came in behind the leopard, saw it, and let out an almost human scream, and then leaped for the nearest tree.

Startled by the cry the leopard whirled around to confront the new foe. In that instant, in one fluid motion the Jungle Queen pounced on her quiver. The beast sensed, rather than saw, the movement. As quick as a flash it turned, a tawny blur in a swirl of dust and dry leaves, and sprang. Sheena's bow twanged just as it left the ground. She leaped aside as the big cat twisted in the air, then fell on its back, rolling over and over, snarling and biting at the arrow driven into its chest. Then Ekoti came panting into the clearing and a thrust from his leaf-bladed spear put a swift end to the beast's struggle.

When he looked around Sheena was moving up wind from the grisly remains of Benji's body, the beauty of her face marred by a grimace of disgust.

"Enough is left," she said, "to tell that his skin was black."

"Many men camped here," Ekoti observed, looking over the ground. "The spoor is not cold, see!" He squatted, pointing to boot-prints on a patch of sandy soil. "Two white men and many black fellows."

They followed the spoor until Sheena was satisfied that it would lead them to Kilma; then she said:

"I go on. You go back to your people. Tell your warriors that Sheena says that there is meat for them at Kilma."

Ekoti rubbed his wooly head. He was a warrior, and he was no man's fool, but for the life of him he could not see how his spearmen could break into Kilma, and his puzzlement was profound. But what Sheena said could not be doubted. Though he had played with her as a child, and though, outwardly, she appeared to be as other women, he had never doubted that she was something more than mortal, and possessed of powers quite beyond his comprehension. There was conviction and awe in his face when he said:

"I think that I will see a great magic at Kilma."

FAMINE and death surrounded Kilma. The rinderpest had come in the wake of the prolonged drouth, and on the plains vultures gorged themselves on the carcasses of dead cattle, spreading their wings as they reached their ugly heads into the fetid mass, their wing tips and breast feathers greasy with fat. But within the mud-walled town itself there was plenty. Its stilted, thatched-roofed silos were full of grain, and a subterranean stream bubbled into its wells, and fed the fountain in the sequestered gardens of Sleman bin Ali's house.

Like most native African towns, all of which seemed to have the Zulu kraal, with its boma of thorn-bush as impenetrable as a barbed-wire entanglement, for their prototype. Kilma had two gates, one facing the other at opposite ends of a broad, central road. The walls encompassed an area of not more than five acres, and into this space was crowded, haphazardly an unbelievable number of adobe houses with a maze of narrow lanes twisting among them. Sleman bin Ali's house fronted on the main road, and its high-walled garden, with its pond and fountain, green grass and heavy-scented hibiscus and jasmine, was like an oasis in a desert of smells that made Rick shudder whenever he set foot outside the arched gate which gave onto the dusty road.

He was allowed the freedom of the town. Famine was his gaoler, and it was Lazaro Pero's gaoler also; for until the rain came the long trek across the border to Bampo was an impossible undertaking. Sleman bin Ali had given Rick a room in his own house, and often he took his meals with the venerable half-Arab who looked more like a saint than the old rogue he undoubtedly was. After his fashion, Ali was a devout man, strict in his observance of the letter, if not spirit, of the precepts set forth in the Koran; and his long white beard, the spotless, white robe and the austerity he affected were so strongly suggestive of the Biblical patriarch that Rick doubted that it was wholly unconscious. He was a courteous and generous host, and that made it easy to forget his crimes and cruelities.

As the days wore on and still the rain did not come, Pero fumed and fretted. Rick avoided him; for whenever they met the Portuguese never failed to jibe at him, to remind him that soon he must go back to the coast and tell Freire how Lazaro Pero had so cleverly tricked him out of a small fortune in ivory.

The whereabouts of the ivory had puzzled Rick from the first day of his arrival in Kilma. There was no building in the town large enough to hold it. He knew that it had long been the custom of native chiefs to bury their hoards to protect them from the rapacity of well armed raiders; and, finally, he came to the conclusion that the ivory must be cached somewhere out in the hills surrounding the town.

Toward sundown on the fifth day of his stay at Kilma a tribe of natives swarmed down from the hills onto the plain. From the flat roof of Sleman bin Ali's house Rick watched them pour out of a narrow gap in the hills and debouch onto the veldt to cut a black swath through the tall, feathery spear-grass. Pero stood beside Sleman bin Ali, who had an old, brass telescope clamped to one eye. Suddenly the Arab exclaimed:

"Merciful Allah! It is that daughter of Shaitan, Sheena."

"Sheena! Surely you are mistaken, my friend!" said Pero. "What would she want of us? Not the ivory. The trade was fair."

Sleman bin Ali's eyes slanted in Rick's direction as he handed the telescope to Pero. "Wallai," he said, "you are a great fool if you cannot guess what she has come for!"

"Holy Saints, who would have thought of that!" muttered Pero in his beard; then: "They have no guns, a volley will drive them off."

"No!" said the Arab sharply. "If they do not attack, we do no shooting. It may be that she wants only our young friend here. By Allah, if that be all, she can have him! I want no trouble with that she-devil. See, they make camp." He turned, shouting for one of his slaves. A M'bama boy answered his call, and Sleman said: "Go tell Ahmed to double all guards. Let him report to me when it is done." To Pero he said: "Those goat-skin water bags you see on the poles will soon be empty. We will know what she wants before long and, Allah willing, she will be gone in the morning."

OUT in the Abama camp Sheena called Ekoti to her fire.

"There is much to do before the sun sets," she told him, and then swept out her arm in a gesture that took in the surrounding hills. "Somewhere out there the Arab has hidden his ivory. Let all the people, even the women, if need be, go out into the hills to look for it."

"What good is ivory?" growled Ekoti. "We cannot eat it." Then his face brightened and his deep laugh rumbled up from the pit of his stomach. "Ho, ho!" he said. "I think I see what is in your mind now, Sheena. You will make the Arab trade meat for his own ivory! Ho, that is good!"

"Perchance he will trade his town for it, Ekoti."

The chief's laughter ended in a grunt of incredulity. "He is not so big a fool, Sheena."

"We will see," the Jungle Queen told him with a smile. "When you find the ivory do not bring it into camp. Leave it where you find it. Now there is another thing. I go into the town tonight. When it is dark you will take your warriors close to the gate yonder. Let them make much noise so that the Arab will think that you are about to attack him."

Ekoti looked across the plain to the high walls of the town and the thatched-roofed watchtowers standing on them. He shook his head. All this talk of trading towns for ivory was very bewildering, and he refused to perplex himself with it any further. Silent, and wooden-faced, he went to organize the search for the ivory.

Soon the Abamas were leaving the camp in small groups to scour the hills. Sheena remained in the camp, watching the town. Presently, two figures came to stand on the roof of Sleman bin Ali's house, and the sun flashed on the brass of the tube one held to his eyes. She watched them, a faint smile on her lips. The Arab, she knew, would guess what her people were looking for; and the Bearded One would fume and sweat, because he was a man who could not control his passions. He would want to rush out and attack the Abamas. But not Sleman bin Ali. He was cautious, and he would wait until he knew the result of the search.

A woman brought her a pot of bangu, a mess of native corn and greens. She accepted it gratefully, ate, and then slept until the noise of the Abama hunters returning to camp aroused her. The sun was down, and the shadow of the western hills was reaching across the veldt, like a black, open hand with six long fingers. The two figures had returned to the roof of the house to watch the incoming search parties. Ekoti's face was sour when he came to report:

"The Arab is a fox, and he does not hide everything in one hole. We have found some teeth. We left them where we found them, as you told us to do."

"How many, Ekoti?"

"Only two hands, Sheena. But they are big teeth," he added defensively.

"It is enough. You have done well. Now, rest your warriors until the middle of the night."

There was a bright moon that night, and it made a ghost town of Kilma. Starving jackals, driven from the carrion stinking on the plain, howled dismally on the fringe of the bush, and occasionally a dog within the town yelped a half-hearted answer to the challenge of the veldt. When the moon was overhead, flooding the plain with the abundance of its light, Ekoti and his warriors left the camp.

AMID a great ostentation of guns and horns they advanced across the open space, in plain view of the guards in the watchtowers. A gun flashed, and another, and then the sleeping town awoke to the deep, booming alarm of a big drum. Soon many guns were snapping on the walls. The Abamas continued their noisy advance upon the west gate until bullets began to whistle all around them; then, at a shout from Ekoti, they sank into the sea of grass, and fanned out. And where there had been shouting and tumult and the glint of moonlight on spears a moment before, there was now nothing to be seen, and no sound but the rustle of movement through the tall grass.

Meanwhile, Sheena and Chim crouched in an area of shadow on the opposite side of the town. The shadow was cast by one of the watchtowers. Its wooden platform, supported by angle-beams sunk into the adobe, overhung the wall. A bright rectangle of moonlight showed between the peaked roof and the breast-high fence of bamboo which enclosed the square space within. The silhouette of the guard's head and shoulders showed black against the sky. The man's attention was drawn to the west gate by a sudden burst of musketry, his back turned to Sheena. Swiftly she darted forward to within twenty paces of the wall. There she stood for an instant, poised with drawn bow-string touching her ear. At the twang of the string winged peril sped true to her aim. The arrow pierced the guard's gun-arm, and the shock sent him slumping against the bamboo rail, knocking him out.

Under the platform Sheena uncoiled a long length of woven-grass rope and tied it around Chim's waist.

"Up, little one!" she commanded, patting the wall with her hand.

There were cracks in the sun-baked adobe, but it was a hard climb even for an ape, and Chim nearly fell twice before he grasped and swung from one of the angle beams under the platform. Holding one end of the rope, Sheena quickly ran to the other side of the beam, and patted the wall again, calling Chim down. Chim started to come down the same way as he had gone up, but a sharp word from below stopped him. He swung back onto the beam and jumped up and down, scolding Sheena. He was very angry. The night was full of loud and terrifying noises. He was in no mood to play this silly game and felt safer where he was. But when he saw his mistress turn as if to go he came down in a hurry and bounded after her. He was a very surprised and frightened ape when the rope, which he had unwittingly looped over the beam, suddenly tightened and jerked him from his feet.

"Good, little one! Good!" Sheena petted and soothed him as she untied the rope. "Go now!" she hissed. And just then a volley of gunfire crashed on the walls and Chim went like a black streak through the grass.

A moment later the Jungle Queen swung her long, shapely legs over the rail of the platform. A ladder, a tree trunk with slats bound across it, made easy her descent into the town.

IT WAS in the dead of that night that Rick awoke with the report of a musket singing in his ears. By the time he had dressed and made his way through the garden and out onto the central road, calamity was on the loose in Kilma. As he came out of the arched gate a group of half-naked Swahilis raced by, yelling like fiends. Others came rushing, muskets in hand, from the huts that flanked the road, and the screams of their women rose to a shrill crescendo as a ragged volley crashed out on the wall near the west gate.

With his back flat against the wall of Sleman bin Ali's garden, with every man in the town capable of bearing arms running for the west gate, Rick's mind jumped to the obvious conclusion. The Abamas were attacking it in force. His first thought was of escape and, hugging the shadow of the wall, he started to move against the tide, heading for the east gate of the town. At the back of his mind there was the dim idea that if he could get out of the town the Abamas might help him to carry out the plan Benji had suggested. But escape was the dominant idea at the moment—escape from Pero's mockery and the nagging sense of defeat that kept flicking at his high spirit like the lash of a vorslaag.

Darkness closed all the lanes which opened onto the main road. The firing on the walls had slackened, and only the occasional flash of a gun tore a path under the starlit sky. The defenders had evidently gotten to their posts in time to beat back the first onslaught. And now silence, breathless, expectant settled on the town. He was crossing the black opening of one of the lanes when he heard a hiss, and then his name spoken softly.

"Sheena!" He turned quickly and saw her shadowy outline against the wall of a hut.

Sheena beckoned to him, and he stepped into the shadows, and stood very close to her. His eyes were very bright and he asked in a husky voice:

"You came to help me?"

"I have come to settle an old quarrel with Sleman bin Ali," she told him coldly. "He has killed many of my people and made slaves of others. It may be that we can help each other."

"I see," he said. But the disappointed look that brought a slight frown to his face told her that he saw nothing and understood less. She smiled inwardly and said:

"The attack is a trick to keep the fools looking the other way while we leave this place. If you want to go we must go quickly. You will have to run fast. Even so, a bullet may find you."

"I'll take that chance," he said. Then he pointed to the east gate. "There is a small door in the big gate. It is the easiest way out if I can creep up on the guard."

She smiled in the darkness. He was more used to giving orders than to take them. She said: "We go by the same way as I came. Come!" And she turned and ran swiftly down the lane.

Straight to the watchtower she led him and went up the ladder in a quick dash that made Rick stare for a moment. As he heaved himself up onto the platform the Swahilis on the far wall were shouting taunts at the Abamas, calling them women because they would not show themselves. Out on the plain the Abama camp fires winked.

Rick went to the rail of the platform and looked down. Sheena saw his puzzlement and there was faint mockery in her soft laugh.

"Sometimes I follow where an ape leads," she told him. He gave her an odd, startled look. Then he saw the stunned guard with the arrow through his arm. Sheena swung from the platform at arm's length, caught the dangling rope with her feet, and quickly slid to the ground. Rick was very nimble, and soon dropped lightly to the ground beside her.

"Run for the fires!" she told him.

"You first," said he.

SHE looked at him closely. Was he afraid? No, there was not a shadow of fear to dim the brightness of his eyes, now shining with excitement. And suddenly she knew what was in his mind. He wanted to shield her with his body, to protect Sheena, Queen of the Jungle! Was there no end to his folly? Did he think she was like one of the pale-faced coast women, a ninny to be petted and pampered by men? Truly he had much to learn. But now was not the time to teach him. Without another word she sprang forward and went flashing across the open space from which the grass had been cleared for more than a hundred yards.

Again Rick stood staring for a moment, then with a muttered prayer, he started to run. There was a shot. A bullet plucked the dirt close to his flying feet. With a thrill of fear he realized that his white topee and shirt must show like a flare against the black of the ground. Hot lead was sizzling about his ears as he plunged into the grass and, panting for breath, dropped to all fours. He crawled the rest of the way into the Abama camp.

Sheena was waiting for him beside one of the fires. Standing there straight and tall, with the firelight highlighting the bronzed perfection of her body, she looked like a goddess indeed. Several native women were grouped about her, naked but for a few tufts of grass. At Rick's approach they withdrew.

"Lady, you are swifter than the wind," he said.

She gave him an enigmatic smile, but did not speak. He tried to interest himself in the contents of a pot bubbling on the fire. But his mind was not on food. Always his eyes came back to her. She found herself wishing that she had not told the other women to leave the fire. She moved back into the shadows. There was no telling what his youthful folly might prompt him to do next.

But soon Ekoti and his warriors came straggling back from the sham attack. Hungry looking warriors they still were, armed with leaf-bladed spears and painted shields. Some had never seen a white man before, and came to point and stare at Rick. Then a drum began to throb, and the bystanders were drawn away to join in the dancing.

"I know you, Bwana," Ekoti greeted Rick in his deep basso.

"I know you, Chief," Rick returned. "It is in my heart to hope that none of your warriors fell in the fight."

The chieftain chuckled. "There was no fight, Bwana. Those Swahili dogs made much noise with their guns, but not a bullet touched us." Then he looked at Sheena and added: "Perchance, tomorrow it will be different. Tell me, Sheena, do we play at war tomorrow, or do we drive them?"

"We drive them," she answered, and glanced up at the sky, now gray with the false dawn. "Rest now, Ekoti. You, Rick, must come with me."

They left the camp and moved swiftly through the grass. It was light when they climbed a wooded hill and looked down on the west gate of the town. Vast banks of clouds, red-bellied with the first rays of the sun, hid the peaks of the distant mountains, and rolled northward on the wings of a freshening wind. It was the first real hope of rain, and the freshness of the breeze bathed them, wiping out memories of heat, hunger and fatigue. Sheena stood beside Rick, her breasts rising and falling as she drank deeply of the freshness of the morning. She said:

"You must help me now, because I do not think that Ekoti would understand what is in my mind." She pointed to the gap in the hills, "Look well at the country before you."

They stood upon a trail that led down to the west gate. Rick's eyes followed the path through the town and across the veldt to where it entered the gap in the hills. There it joined the old caravan road to Bampo, and appeared again like a red welt on the shoulder of a low hill to the northeast of the town, and then it dropped out of sight into a densely wooded kloof.