RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

"Daughter of the Sun," Grosset & Dunlap, New York, 1921

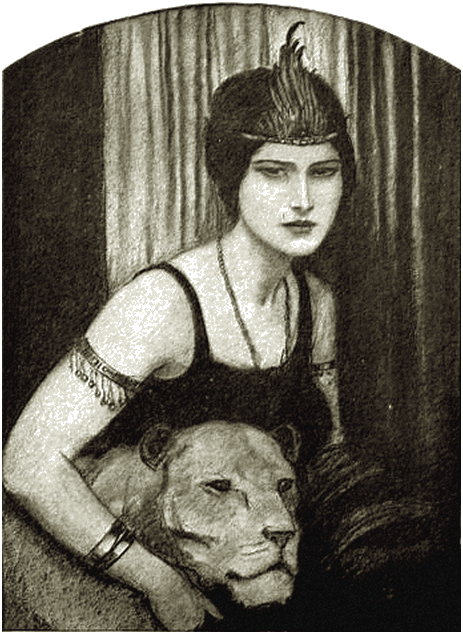

Zoraida Castelmar, daughter of the Montezumas.

In which a young American known as

"Headlong"

plays at dice with one in man's clothing who is

not a man

JIM KENDRIC had arrived and the border town knew it well. All who knew the man foresaw that he would come with a rush, tarry briefly for a bit of wild joy and leave with a rush for the Lord knew where and the Lord knew why. For such was ever the way of Jim Kendric.

A letter at the post office had been the means of advising the entire community of the coming of Kendric. The letter was from Bruce West, down in Lower California, and scrawled across the flap were instructions to the postmaster to hold it for Jim Kendric who would arrive within a couple of weeks. Furthermore the word URGENT was not to be overlooked.

Among the men drawn together in hourly expectation of the arrival of Kendric, one remarked thoughtfully:

"Jim's Mex friend is in town."

"Ruiz Rios?" someone asked, a man from the outside.

"Been here three days. Just sticking around and doing nothing but smoke cigarettes. Looks like he was waiting."

"What for?"

"Waiting for Jim, maybe?" was suggested.

Two or three laughed at that. In their estimation Ruiz Rios might be the man to knife his way out of a hole, but not one to go out of his way to cross the trail made wide and recklessly by Jim Kendric.

"A half hour ago," came the supplementary information from another quarter, "a big automobile going to beat the band pulls up in front of the hotel. The Mex is watching and when a woman climbs down he grabs her traps and steers her into the hotel."

Immediately this news bringer was the man of the moment. But he had had scant time to admit that he hadn't seen her face, that she had worn a thick black veil, that somehow she just seemed young and that he'd bet she was too darn pretty to be wasting herself on Rios, when Jim Kendric himself landed in their midst.

He was powdered with alkali dust from the soles of his boots to the crown of his black hat and he looked unusually tall because he was unusually gaunt. He had ridden far and hard. But the eyes were the same old eyes of the same old headlong Jim Kendric, on fire on the instant, dancing with the joy of striking hands with the old-timers, shining with the man's supreme joy of life.

"I'm no drinking man and you know it," he shouted at them, his voice booming out and down the quiet blistering street. "And I'm no gambling man. I'm steady and sober and I'm a regular fool for conservative investments! But there's a time when a glass in the hand is as pat as eggs in a hen's nest and a man wants to spend his money free! Come on, you bunch of devil-hounds; lead me to it."

It was the rollicking arrival which they had counted on since this was the only way Jim Kendric knew of getting back among old friends and old surroundings. There was nothing subtle about him; in all things he was open and forthright and tempestuous. In a man's hardened and buffeted body he had kept the heart of a harum-scarum boy.

"It's only a step across the line into Old Town," he reminded them. "And the Mexico gents over there haven't got started reforming yet. Blaze the trail, Benny. Shut up your damned old store and postoffice, Homer, and trot along. It's close to sunset any way; I'll finance the pilgrimage until sunup."

When he mentioned the "postoffice" Homer Day was recalled to his official duties as postmaster. He gave Kendric the letter from Bruce West. Kendric ripped open the envelope, glanced at the contents, skimming the lines impatiently. Then he jammed the letter into his pocket.

"Just as I supposed," he announced. "Bruce has a sure thing in the way of the best cattle range you ever saw; he'll make money hand over fist. But," and he chuckled his enjoyment, "he's just a trifle too busy scaring off Mexican bandits and close- herding his stock to get any sleep of nights. Drop him a postcard, Homer; tell him I can't come. Let's step over to Old Town."

"Ruiz Rios is in town, Jim," he was informed.

"I know," he retorted lightly. "But I'm not shooting trouble nowadays. Getting older, you know."

"How'd you know?" asked Homer.

"Bruce said so in his letter; Rios is a neighbor down in Lower California. Now, forget Ruiz Rios. Let's start something."

There were six Americans in the little party by the time they had walked the brief distance to the border and across into Old Town. Before they reached the swing doors of the Casa Grande the red ball of the sun went down.

"Fat Ortega knows you're coming, Jim," Kendric was advised. "I guess everybody in town knows by now."

And plainly everybody was interested. When the six men, going in two by two, snapped back the swinging doors there were a score of men in the place. Behind the long bar running along one side of the big room two men were busy setting forth bottles and glasses. The air was hazy with cigarette smoke. There was a business air, an air of readiness and expectancy about the gaming tables though no one at this early hour had suggested playing. Ortega himself, fat and greasy and pompous, leaned against his bar and twisted a stogie between his puffy, pendulous lips. He merely batted his eyes at Kendric, who noticed him not at all.

A golden twenty dollar coin spun and winked upon the bar impelled by Jim's big fingers and Kendric's voice called heartily:

"I'd be happy to have every man here drink with me."

The invitation was naturally accepted. The men ranged along the bar, elbow to elbow; the bartenders served and, with a nod toward the man who stood treat, poured their own red wine. Even Ortega, though he made no attempt toward a civil response, drank. The more liquor poured into a man's stomach here, the more money in Ortega's pocket and he was avaricious. He'd drink in his own shop with his worst enemy provided that enemy paid the score.

Kendric's friends were men who were always glad to drink and play a game of cards, but tonight they were gladder for the chance to talk with "Old Headlong." When he had bought the house a couple of rounds of drinks, Kendric withdrew to a corner table with a dozen of his old-time acquaintances and for upward of an hour they sat and found much to talk of. He had his own experiences to recount and sketched them swiftly, telling of a venture in a new silver mining country and a certain profit made; of a "misunderstanding," as he mirthfully explained it, now and then, with the children of the South; of horse swapping and a taste of the pearl fisheries of La Paz; of no end of adventures such as men of his class and nationality find every day in troublous Mexico. Twisty Barlow, an old-time friend with whom once he had gone adventuring in Peru, a man who had been deep sea sailor and near pirate, real estate juggler, miner, trapper and mule skinner, sat at his elbow, put many an incisive question, had many a yarn of his own to spin.

"Headlong, old mate," said Twisty Barlow once, laying his knotty hand on Kendric's arm, "by the livin' Gawd that made us, I'd like to go a-journeyin' with the likes of you again. And I know the land that's waitin' for the pair of us. Into San Diego we go and there we take a certain warped and battered old stem- twister the owner calls a schooner. And we beat it out into the Pacific and turn south until we come to a certain land maybe you can remember having heard me tell about. And there—It's there, Headlong, old mate!"

Kendric's eyes shone while Barlow spoke, but then they always shone when a man hinted of such things as he knew lay in the sailorman's mind. But at the end he shook his head.

"You're talking about tomorrow or next day, Twisty," he laughed, filling his deep lungs contentedly. "I've had a bellyful of mañana-talk here of late. All I'm interested in is tonight." He rattled some loose coins in his pocket. "I've got money in my pocket, man!" he cried, jumping to his feet. "Come ahead. I stake every man jack of you to ten dollars and any man who wins treats the house."

Meanwhile Ortega's place had been doing an increasing business. Now there was desultory playing at several tables where men were placing their bets at poker, at seven-and-a-half and at roulette; the faro layout would be offering its invitation in a moment; there was a game of dice in progress.

Kendric's companions moved about from table to table laughing, making small bets or merely watching. But presently as half dollars were won and lost the insidious charm of hazard touched them. Monte stuck fast to the faro table for fifteen minutes, at the end of which time he rose with a sigh, tempted to go back to Kendric for a "real stake" and cut in for a man's play. But he thought better of it and strolled away, rolling a cigarette and watching the others. Jerry bought a ten dollar stack of chips and assayed his fortune with roulette, playing his usual luck and his usual system; with every hazard lost he lost his temper and doubled his bet. He was the first man to join Monte.

For upward of an hour of play Kendric was content with looking on and had not hazarded a cent beyond the money flung down on the table to be played by his friends. But now at last he looked about the room eagerly, his head up, his eyes blazing with the up-surge of the spirit riding him. About his middle was a money belt, safely brought back across the border; in his wild heart was the imperative desire to play. Play high and quick and hard. It was then that for the first time he noted Ruiz Rios. Evidently the Mexican had just now entered from the rear. At the far end of the room where the kerosene lamp light was none too good Rios was standing with a solitary slim-bodied companion. The companion, to call for all due consideration later, barely caught Jim's roving eye now; he saw Rios and he told himself that the gamblers' goddess had whisked him in at the magic moment. For in one essential, as in no others, was Ruiz Rios a man after Jim Kendric's own heart: the Mexican was a man to play for any stake and do no moralizing over the result.

"Ortega," cried Kendric, looking all the time challengingly at Rios, "there is only one game worth the playing. King of games? The emperor of games! Have you a man here to shake dice with me?"

Ortega understood and made no answer, Rios, small and sinister and handsome, his air one of eternal well-bred insolence, kept his own counsel. There came a quick tug at his sleeve; his companion whispered in his ear. Thus it was that for the first time Kendric really looked at this companion. And at the first keen glance, in spite of the male attire, the loose coat and hat pulled low, the scarf worn high about the neck, he knew that it was a woman who had entered with Ruiz Rios and now whispered to him.

"His wife," thought Kendric. "Telling him not to play. She's got her nerve coming in here."

The question of her relationship to the Mexican was open to speculation; the matter of her nerve was not. That was definitely settled by the carriage of her body which was at once defiant and imperious; by the tilt of the chin, barely glimpsed; by the way she stood her ground as one after another pair of eyes turned upon her until every man in the room stared openly. It was as useless for her to seek to disguise her sex thus as it would be for the moon to mask as a candle. And she knew it and did not care. Kendric understood that on the moment.

"Between us there has been at times trouble, señor," said Rios lightly. "I do not know if you care to play? If so, I will be most pleased for a little game."

"I'd shake dice with the devil himself, friend Ruiz," answered Jim heartily.

"I must have some money from Ortega here," said Rios carelessly. "Unless my check will satisfy?"

"Better get the money," returned Kendric pleasantly.

As Rios turned away with the proprietor Kendric was impelled to look again toward the woman. She had moved a little to one side so that now she stood in the shadow cast by an angle of the wall. He could not see her eyes, so low had she drawn her wide sombrero, nor could he make out much of her face. He had an impression of an oval line curving softly into the folds of her scarf; of masses of black hair. But one thing he knew: she was looking steadily at him. It did not matter that he could not see her eyes; he could feel them. Under that hidden gaze there was a moment during which he was oddly stirred, vaguely agitated. It was as though she, some strange woman, were striving to subject his mind to the spell of her own will; as though across the room she were seeking not only to read his thought but to mold it to the shape of her own thought. He had the uncanny sensation that her mind was rifling his, that it would be hard to hide from those probing mental fingers any slightest desire or intention. Kendric shook himself savagely, angered that even for an instant he should have submitted to such sickish fancies. But even so, and while he strode to the nearby table for the dice cup, he could not free himself from the impression which she had laid upon him.

She beckoned Rios as he came back with Ortega. He went to her side and she whispered to him.

"We will play here, at this end of the room, señor," Rios said to Kendric.

As Kendric looked quite naturally from the one who spoke to the one from whom so obviously the order had come, he saw for the first time the gleam of the woman's eyes. A very little she had lifted the brim of her hat so that from beneath she could watch what went forward. They held his gaze riveted; they seemed to glow in the shadows as though with some inner light. He could not judge their color; they were mere luminous pools. He started with an odd fancy; he caught himself wondering if those eyes could see in the dark?

Again he shrugged as though to shake physically from him these strange fancies. He snatched up the little table and brought it to where Ruiz Rios waited, putting it down not three feet from the Mexican's silent companion. And all the time, though now he refused to turn his head toward her, he was conscious of the strangely disturbing certainty that those luminous eyes were regarding him with unshifting intensity.

Kendric abruptly spilled the dice out of the cup so that they rolled on the table top.

"One die, one throw, ace high?" he asked curtly of Rios.

The Mexican nodded.

It was in the air that there would be big play, and men crowded around. Briefly, the unusual presence of a woman, here at Fat Ortega's, was forgotten.

"Select the lucky cube," Kendric invited Rios. The Mexican's slim brown fingers drew one of the dice toward him, choosing at random.

Kendric opened vest and shirt and after a moment of fumbling drew forth and slammed down on the table a money belt that bulged and struck like a leaden bar.

"Gold and U. S. bank notes," he announced. "Keep your eye on me, Señor Don Ruiz Rios de Mexico, while I count 'em."

Unbuttoning the pocket flaps, he began pouring forth the treasure which he had brought back with him after two years in Old Mexico. Boyish and gleeful, he enjoyed the expressions that came upon the faces about him as he counted aloud and Rios watched with narrow, suspicious eyes. He sorted the gold, arranging in piles of twenties and tens, all American minted; he smoothed out the bank notes and stacked them. And at the end, looking up smilingly, he announced:

"An even ten thousand dollars, señor."

"You damn fool!" cried out Twisty Barlow hysterically. "Why, man, with that pile me an' you could sail back into San Diego like kings! Now that dago will pick you clean an' you know it."

No one paid any attention to Barlow and he, after that one involuntary outburst, recognized himself for the fool and kept his mouth shut, though with difficulty.

Ruiz Rios's dark face was almost Oriental in its immobility. He did not even look interested. He merely considered after a dreamy, abstracted fashion.

Again a quick eager hand was laid on his arm, again his companion whispered in his ear. Rios nodded curtly and turned to Ortega.

"Have you the money in the house?" he demanded.

"Seguro," said the gambling house owner. "I expected Señor Kendric."

"You do me proud," laughed Jim. "Let's see the color of it in American money."

With most men the winning or losing of ten thousand dollars, though they played heavily, was a matter of hours and might run on into days if luck varied tantalizingly. All of the zest of those battling hours Jim Kendric meant to crowd into one moment. There was much of love in the heart of Headlong Jim Kendric, but it was a love which had never poured itself through the common channels, never identified itself with those two passions which sway most men: he had never known love for a woman and in him there was no money-greed. For him women did not come even upon the rim of his most distant horizon; as for money, when he had none of it he sallied forth joyously in its quest holding that there was plenty of it in this good old world and that it was as rare fun running it down as hunting any other big game. When he had plenty of it he had no thought of other matters until he had spent it or given it away or watched it go its merry way across a table with a green top like a fleet of golden argosies on a fair emerald sea voyaging in search of a port of adventure. His love was reserved for his friends and for his adventurings, for clear dawns in solitary mountains, for spring-times in thick woods, for sweeps of desert, for what he would have called "Life."

"Ready?" Ruiz Rios was asking coldly. Ortega had returned with a drawer from his safe clasped in his fat hands; the money was counted and piled.

"Let her roll," cried Kendric heartily.

Never had there been a game like this at Ortega's. Men packed closer and closer, pushing and crowding. The Mexican slowly rattled the single die in the cup. Then, with a quick jerk of the wrist, he turned it out on the table. It rolled, poised, settled. The result amply satisfied Rios and to the line of the lips under his small black mustache came the hint of a smile; he had turned up a six.

"The ace is high!" cried Jim. He caught up die and box, lifting the cupped cube high above his head. His eyes were bright with excitement, his cheeks were flushed, his voice rang out eagerly.

"Out of six numbers there is only one ace," smiled Ruiz Rios.

"One's all I want, señor," laughed Jim. And made his throw.

When large ventures are made, in money or otherwise, it would seem that the goddess of chance is no myth but a potent spirit and that she takes a firm deciding hand. At a time like this, when two men seek to put at naught her many methods of prolonging suspense, she in turn seeks stubbornly to put at naught their endeavors to defeat her aims. Had Jim Kendric thrown the ace then he would have won and the thing would have been ended; had he shaken anything less than a six the spoils would have been the Mexican's. That which happened was that out of the gambler's cup Kendric turned another six.

Ruiz Rios's impassive face masked all emotion; Kendric's displayed frankly his sheer delight. He was playing his game; he was getting his fun.

"A tie, by thunder!" he cried out in huge enjoyment. "We're getting a run for our money, Mexico. Shall I shake next?"

"Follow your hand," said Ruiz Rios briefly.

That which followed next would have appeared unbelievable to any who have not over and over watched the inexplicable happenings of a gaming table. Kendric made his second throw and lifted his eyebrows quizzically at the result. He had turned out the deuce, the lowest number possible. A little eagerly, while men began to mutter in their excitement, Rios snatched up cup and die and threw. Once already he had counted ten thousand as good as won; now he made the same mistake. For the incredible happened and he, too, showed a deuce, making a second tie.

Ruiz cursed his disgust and hurled the box down. Kendric burst into booming laughter.

"A game for men to talk about, friend Rios!" he said. And at the moment he came near feeling a kindly feeling for a man whom he hated most cordially and with high reason. "Follow your hand."

Rios received the box from a hand offering it and made his third throw swiftly. The six again.

"Where we began, señor," he said, grown again impassive.

Kendric was all impatient eagerness to make his throw, looking like a boy chafing at a moment's restraint against his anticipated pleasures.

"A six to beat," he said.

And beat it he did, with the odds all against him. He turned up the ace and won ten thousand dollars.

In the brief hush which came before the shouts and jabberings of many voices, Ruiz Rios's companion pulled him sharply by the arm, whispering quickly. But this time Rios shook his head.

"I am through," he said bluntly. "Another time, maybe."

But the fever, to which he had so eagerly surrendered, was just gripping Kendric. That he was playing for big stakes was the thing that counted. That he had won meant less to him than it would have meant to any other man in the room or any other man who had ever been in the room or any other man who would ever come into the room. He saw that Ruiz was through. But, as his dancing eyes sped around among other faces, he marked the twinkling lights of covetousness in Fat Ortega's rat eyes and he knew that, long ago, Ortega himself had played for any stake. Beside Ortega there was another man present who might be inclined to accept a hazard, Tony Muñoz, who conducted the rival gambling house across the street and who was Ortega's much despised son-in-law. Long ago Ortega and Tony had quarreled and when Tony had run away with Eloisa, Ortega's pretty daughter, men said it was as much to spite the old man as for love of the girl's snapping eyes. Tony might play, if Ortega refused.

"One throw for the whole thing, Ortega?" challenged Kendric. "You and me."

"Have I twenty thousand pesos in my pocket?" jeered Ortega. "You make me the big gringo bluff."

"Bluff? Call it then, man. That's what a bluff is for. And you don't need the money in the pocket. This house is yours; your cellars are always full of expensive liquors; there is money in your till and something in your safe yet, I'll bet my hat. Put up the whole thing against my wad and I'll shake you for it."

Plainly Ortega was tempted. And why not? There lay on the green table, winking up alluringly at him, twenty thousand dollars. His, if simply a little cube with numbers on it turned in proper fashion. Twenty thousand dollars! He licked his fat pendulous lips. And, to further tempt him, he estimated that his entire holding here, bar fixtures, tables, wines and cash, were worth not above fifteen thousand. But then, this was all that he had in the world and though he craved further gains until the craving was acute like a pain, still he clung avidly to the power and the prestige and the luxury that were his as owner of la Casa Grande. In brief, he was too much the moral coward to be such a gambler as Kendric called for.

"No," he snapped angrily.

"Look," said Kendric, smiling. He shook the die and threw it, inverting the cup over it so that it was hidden. "I do not know what I have thrown, Ortega, and you do not know. I will bet you five thousand dollars even money that it is a six or better."

Here were odds and Ortega jerked up his head. Five thousand to bet—

"No," he said again. "No. I don't play. You have devil's luck."

With a flourish Jim lifted the cup to see what he had thrown. Again his utterly mirthful laughter boomed out. It was the deuce, the low throw. Ortega strained forward, saw and flushed. Had he but been man enough to say "Yes!" to the odds offered him he would have been five thousand dollars richer this instant! Five thousand dollars! He ran a flabby hand across a moist brow.

"Where's the luck in that throw?" demanded Kendric, fully enjoying the play of expression on Ortega's face.

"The luck," grumbled Ortega, "was that I did not bet you. If I had bet it would have been a six, no less."

"Tony Muñoz," called Kendric, turning. "Will it be you?"

"No!" shouted Ortega, already angered in his grasping soul, ready to spew forth his wrath in any direction, always more than ready to rail at his son-in-law. "Muñoz has no business in my house. Who is boss here? It is me!"

Kendric seeing that Tony Muñoz was contenting himself with sneering and certainly would not play, began gathering up the money on the table. It was then that for the first time he heard the voice of Ruiz Rios's companion.

"I will play Señor Kendric."

The voice ran through the quiet of the room musically. The utterance was low, gentle, the accent was the soft, tender accent of Old Spain with some subtle flavor of other alien races. No man in the room had ever heard such sweet, soothing music as was made by her slow words. After the sound died away a hush remained and through men's memories the cadences repeated themselves like lingering echoes. Kendric himself stared at her wonderingly, not knowing why her hidden look stirred him so, not knowing why there should be a spell worked by five quiet words. Nor did he find the spell entirely pleasant; as her look had done, so now her speech vaguely disturbed him. His emotion, though not outright irritation, was akin to it. He was opening his lips to say curtly, "I do not play dice with women, señora," when Ortega's sudden outburst forestalled him.

Kendric had barely had the time to register the faint impression of the odd sensation which this companion of Ruiz Rios awoke in him, when he was set to puzzle over Ortega's explosion. Why should the gaming-house keeper raise so violent an objection to any sort of a game played in his place? Perhaps Ortega himself could not have explained clearly since it is doubtful if he felt clearly; it is likely that a childishly blind anger had spurted up venomously in his heart when Kendric had exposed the deuce and men had laughed and Ortega felt as though he had lost five thousand dollars. In such a case a man's wrath explodes readily, combustion breaking forth spontaneously like an oily rag in the sun. At any rate, his fat face grown hectic, he lifted hand and voice, shouting:

"I will have no women gambling here. This is my place, a place for men. You," and he leveled his forefinger at the slim figure, "go!"

She ignored him. Stepping forward quickly, she whipped off her left glove and in the bare white fingers, blazing with red and green stones set in golden circlets, she caught up the dice cup. Even now little was seen of her face for the other hand had drawn lower the wide hat, higher the scarf about the throat.

"One die, one throw for it all, Señor Kendric?" she asked.

"I tell you, No!" shouted Ortega. "And No again!"

Then, when she stood unmoved, her air of insolence like Ruiz Rios's, but even more marked, Ortega burst forward between the men standing in his way, shoving them to right and left with the powerful sweep of his thick arms. His uplifted hand came down on her shoulder, thrusting her backward. Her ungloved hand, the left as Kendric marked while he watched interestedly, flashed to her bosom, and leaped out again, a thin-bladed knife in the grip of the bejewelled fingers. Ortega saw and feared and, grown nimble, sprang back from her. Quickly enough to save the life in him, not so quickly as entirely to avoid the sweep of the knife. His sleeve fell apart, slit from shoulder to wrist, and in the opening the man's flesh showed with a thin red line marking it.

There was tumult and confusion for a little while, hardly more than a moment it seemed to Kendric. He only knew that at the end of it Ortega had gone grumbling away, led by a couple of friends who no doubt would bandage his wounded arm, and that the woman, having put her knife away, appeared not in the least disturbed. He knew then that while men talked and shouted about him he had not once withdrawn his eyes from her.

"One throw?" she was asking again, the voice as tender, as vaguely disquieting to his senses, as full of low music as before. He shook himself as though rousing from a trance.

"I do not play at dice with ladies, Señora," he said bluntly.

"Did you bluff, after all?" she asked curiously. She seemed sincere in her question; he fancied a note of disappointment in her tone. It was as though she had said before, "Here is a man who is not afraid of big stakes," and as though now she were revising her estimate of him. "Men will call you Big Mouth," she added. "And I, I will laugh in your face."

"Where is the money you would wager against mine?" demanded Jim, thinking he saw the short easy way out.

Already she was prepared for the question. In her gloved hand was a little hand bag, a trifle in black leather the size of a man's purse. She opened it and spilled the contents on the table. Poured out into the mellow lamp light a long glorious string of pearls appeared, each separate lustrous gem glowing with its silvery sheen, satiny and tremulous with its shining loveliness.

"Holy God!" gasped Twisty Barlow.

"There is the worth of your money many times over," came the quiet assurance in the low voice like liquid music.

"If they are real pearls," muttered Kendric. "And not just imitations."

She made no reply. He felt that from the shelter of the broad hat brim a pair of inscrutable eyes were smiling scornfully.

"Can't I tell real pearls like them, when I see 'em?" cried Twisty Barlow excitedly. He leaned forward and caught the great necklace up in his eager hands. "What would I be wantin' that steamer in San Diego Bay for if I didn't know?" He held them up to the lamp light; he fingered them one after the other; he put them down at the end reverently and with a great sigh. "The worth of them, Headlong, my boy," he said shakily, "would make your pile look sick."

"And yet I'd bet a thousand they're phony," burst from Kendric. Then he caught himself up short. Suppose they were or were not? A woman was offering to play him and he was holding back; he was making excuses, the second already; in his own ears his words, sensible though they were, began to ring like the petty talk of a hedger. "Turn out the die, Señora," he said abruptly. "As you say, one throw and ace high."

With her left hand she quietly shook the box, setting the white cube dancing therein. "You lose, Jim," said Monte at his elbow before the cast was made. "Look out for left-handers." Then she made her throw and turned up an ace.

Kendric caught up box and die and threw. And again he had turned the deuce, the lowest number on the die. He heard her laugh as she drew money and jewels toward her. All low music, ruining a man's blood, thrilling him after that strange perturbing fashion.

In which a spell is worked and an expedition is begun

FOR a moment she and Jim Kendric stood facing each other with only the little table and its cargo of treasure separating them, engulfed in a great silence. He saw her eyes; they were like pools of lambent phosphorescence in the black shadow of her hair. He glimpsed in them an eloquence which mystified him; it was as though through her eyes her heart or her mind or her soul were reaching out toward his but speaking a tongue foreign to his understanding. Her gaze was steady and penetrating and held him motionless. Nor, though he did not at the time notice, did any man in the room stir until she, turning swiftly, at last broke the charm. She went out through the rear door, Ruiz Rios at her heels.

When the door closed after them Kendric chanced to note Twisty Barlow at his elbow. A queer expression was stamped on the rigid features of the sailorman. Plainly Barlow, intrigued into a profound abstraction, was alike unconscious of his whereabouts or of the attention which he was drawing. His eyes stared and strained after the vanished Mexican and his companion; he, too, had been fascinated; he was like a man in a trance. Now he started and brushed his hand across his eyes and, moving jerkily, hurried to the door and went out. Kendric followed him and laid a restraining hand upon his shoulder.

"Easy, old boy," he said quietly. Barlow started at the touch of his hand and stood frowning and fingering his forelock. "I know what's burning hot in your fancies. Remember they may be paste, after all. And anyway they're not treasure trove."

"You mean those pearls might be fake?" Barlow laughed strangely. "And you think I might be slittin' throats for them? Don't be an ass, Headlong; I'm sober."

"Where away, then, in such a hurry?" demanded Kendric, still aware of something amiss in Barlow's bearing.

"About my business," retorted the sailor. "And suppose you mind yours?"

Kendric shrugged and went back to his friends. But at the door he turned and saw Barlow hastening along the dim street in the wake of the disappearing forms of Ruiz Rios and the woman.

Inside there were some few who sought to console Kendric, thinking that to any man the loss of ten thousand dollars must be a considerable blow. His answer was a clap on the back and a laughing demand to know what they were driving at and what they took him for, anyway? Those who knew him best squandered no sympathy where they knew none was needed. To the discerning, though they had never known another man who won or lost with equal gusto in the game, who when he met fortune or misfortune "treated those two impostors just the same," Jim Kendric was exactly what he appeared to be, a devil-may-care sort of fellow who had infinite faith in his tomorrow and who had never learned to love money.

Kendric was relieved when, half an hour later, Twisty Barlow came back. Kendric's mood was boisterous from the sheer joy of being among friends and once more as good as on home soil. He went up and down among them with his pockets turned wrong-side out and hanging eloquently, swapping yarns, inviting recitals of wild doings, making a man here and there join him in one of the old songs, singing mightily himself. He had just given a brief sketch of the manner in which he had acquired his latest stake; how down in Mexico he had done business with a man whom he did not trust. Hence Kendric had insisted on having the whole thing in good old U. S. money and then had ridden like the devil beating tan bark to keep ahead of the half-dozen ragged cut- throats who, he was sure, had been started on his trail.

"And now that I'm rid of it," he said, "I can get a good night's sleep! Who wants to be a millionaire anyway?"

He saw that though Barlow had once more command of his features, there was still a feverish gleam in his eyes. And, further, that with rising impatience Barlow was waiting for him.

"Come alive, Twisty, old mate," Kendric called to him. "Limber up and give us a good old deep-sea chantey!"

Twisty stood where he was, eyeing him curiously.

"I want to talk to you, Jim," he said. His voice like his look told of excitement repressed.

"It's early," retorted Kendric, "and talk will keep. A night like this was meant for other things than for two old fools like you and me to sit in a corner with long faces. Strike up the chantey."

"You're busted," said Barlow sharply; "You've had your fling and you've shot your wad. Come along with me. You know what shore I'm headin' to. You know I've got my hooks in that old tub down to San Diego—"

"There's a craft in San Diego,"

improvised Kendric lightly.

"With no cargo in her hold,

And old Twisty Barlow's leased her

For to fill her up with Gold.

And he'd go a buccaneerin', privateerin', wildly steerin'

For the beaches where the sun

shines on whole banks of blazin' pearls—"

But his rhythm was getting away from him and his rhymes petered out and he stopped, laughing while around him men clamored for more.

"Oh, there'll be a tale to tell when Twisty sails back," he conceded. "But until he's under way there's no tale to tell and so what's the use of talk? A song's better; walk her up, Twisty, old mate."

Barlow's impatience flared out into irritation.

"What's the sense of this monkey business?" he demanded. "I'm off to San Diego by moon-rise. If you ain't with me, you ain't. Just say so, can't you?"

"A song first, Twisty?" countered Kendric.

"Will you come listen to me then?" asked Barlow. "Word of honor?"

It was plain that he was in dead earnest and Kendric cried, "Yes," quite heartily. Then Barlow, putting up with Kendric's mood since there was no other way that one might do for a wilful, spoiled child over which he had no authority of the rod, allowed himself to be dragged to the middle of the room and there, standing side by side, the two men lifted their voices to the swing and pulse of "The Flying Fish Catcher," through all but interminable verses, while the men about them kept enthusiastic time by tramping heavily with their thick boots. At the end Kendric put his arm about the shoulders of his shorter companion, and in lock step they went out. The party was over.

"What's on your mind, Seafarer?" asked Kendric when they were outside.

"Loot, mostly," said Barlow. "But first, while I think of it, Ruiz Rios's wife wants a word with you."

"What about?" Kendric opened his eyes. And, before Barlow answered, "You saw her then?"

"I went up to the hotel. Tried to get a room. She saw me and sent for you. She didn't say what for."

"Well, I'll not go," Kendric told him. "Now spin your yarn about your loot."

He leaned against a lamp post while Twisty Barlow, upright and eager, said his say. A colorful tale it was in which the reciter was lavish with pearls and ancient gold. It appeared that one had but to sail down the coast of Lower California, up into the gulf and get ashore upon a certain strip of sandy beach in the shadows of the cliffs.

"And I tell you I've already got the hull off San Diego that will take us there," maintained Barlow. "All I'm short of is you to stand your share of the hell we'll raise and to chip in with what coin you can scrape. If you hadn't been a damn fool with that ten thousand," he added bitterly.

"Spilled milk. Forget it. It came out of Mexico and it goes back where it belongs. But if you're counting on me for any such amount as that, you're up a tree. I'm flat."

"We'll go just the same if you can't raise a bean," said Barlow positively. "But if you can dig anything, for God's sake scrape lively. We want to get there before somebody else does. And I was hopin' you'd come across for grub and some guns and odds and ends."

"I've got a few oil shares," said Kendric. "If they're roosting around par they're good for twenty-five hundred."

Barlow brightened.

"We'll knock 'em down in San Diego if we only get two fifty!" he announced, considering the sale as good as made. "And we'll do the best we can on what we get."

Not yet had Kendric agreed to go adventuring with Twisty Barlow. But in his soul he knew that he would go, and so did Barlow. There was nothing to hold him here; from elsewhere the voice which seldom grew quiet was singing in his ears. He knew something of the gulf into which Barlow meant to lead him, and of that defiant, legend-infested strip of little-known land which lay in a seven hundred mile strip along its edge; he knew that if a man found nothing else he would stand his chance of finding life running large. It was the last frontier and as such it had the singing voice.

"You'll go?" said Barlow.

But first Kendric asked his few questions. When he had answers to the last of them his own eyes were shining. His truant fancies at last had been snared; he was going headlong into the thing, he had already come to believe that at the end of it he would again have filled his pockets the while he would have drunk deep of the life that satisfied. It was long since he had smelled the sea, had known ocean sunrise and sunset, had gone to sleep with his bunk swaying and the water lapping. So when again Barlow said, "You'll come?" Kendric's hand shot out to be gripped by way of signing a contract, and his voice rang out joyously, "Put her there, old mate! I'm with you, blow high, blow low."

For a few minutes they planned. Then Barlow hurried off to make what few arrangements were necessary before they could be in the saddle and riding toward a railroad. Kendric meant to get two or three hours' sleep since he realized that even his hard body could not continue indefinitely as he had been driving it here of late. There was nothing to be done just now that Barlow could not do; before the saddled horses could be brought for him he could have time for what rest he needed.

The thought of bed was pleasant as he walked on for he realized that he was tired in every muscle of his body. The street was deserted saving the figure of a boy he saw coming toward him. As he was turning a corner the boy's voice accosted him.

"Señor Kendric," came the call. "Un momenta."

Kendric waited. The boy, a half-breed in ragged clothes, came close and peered into his face. Then, having made sure, he whipped out a small parcel from under his torn coat.

"Para usted," he announced.

Kendric took it, wondering.

"What is it?" he asked. "Who sent it?"

But the boy was slouching on down the street. Kendric called sharply; the boy hastened his pace. And when Kendric started after him the ragamuffin broke into a run and disappeared down an alley way. Kendric gave him up and came back to the street, tearing off the outer wrap of the package under a street lamp. In his hand was a sheaf of bank notes which he readily recognized as the very ones he had just now lost at dice, together with a slip of note paper on which were a few finely penned lines. He held them up to the light in an amazement which sought an explanation. The words were in Spanish and said briefly:

"To Señor Jim Kendric because under his laugh he looked sad when he lost. From one who does not play at any game with faint hearts."

His face flushed hot as he read; angrily his big hand crumpled

message and bank notes together. He glanced down the empty

street; then forgetful of bed and rest, his anger rising, he

strode swiftly off toward the hotel, muttering under his breath.

The hotel-keeper he found alone in the little room which served

him as office and bed chamber.

"I want to see Mrs. Rios," said Kendric curtly.

"You'd be meaning the Mexican lady? Name of Castelmar." He drew his soiled, inky guest book toward him. "Zoraida Castelmar."

"I suppose so," answered Kendric. "Where is she?"

"Your name would be Kendric?" persisted the hotel-keeper. And at Kendric's short "Yes," he pointed down the hall. "Third door, left side. She's expecting you."

Had Kendric paused to speculate over the implication of the man's words he would inevitably have understood the trick Ruiz Rios's companion had played on him. But he was never given to stopping for reflection when he had started for a definite goal and furthermore just now his wrath was consuming him. He went furiously down the hall and struck at the door as though it were a man who had stirred his anger by standing in his path. "Come in," invited a woman's voice in Spanish, the inflection distinctly that of old Mexico. In he went.

Before him stood an old woman, her face a tangle of deep wrinkles, her hair spotted with white, her eyes small and black and keen. He looked at her in surprise. Somehow he had counted on finding Zoraida Castelmar young; just why he was not certain. But the surprise was an emotion of no duration, since a hotter emotion overrode it and crowded it out.

"Look here," he began angrily, his hand lifted, the bills tight clenched.

But she interrupted.

"You are Señor Kendric, no? She awaits you. There."

She indicated still another door and would have gone to open it for him. But he brushed by her and threw it back himself and crossed the threshold impatiently. And again his emotion surging uppermost briefly was one of surprise. The room was empty; it was the unexpected and incongruous trappings which astonished him. On all hands the walls, from ceiling to floor, were hidden by rich silken curtains, hanging in deep purple folds, displaying a profusion of bright hued woven patterns, both splendid and barbaric. The floor was carpeted by a soft thick rug, as brilliant as the wall drapes. The two chairs were hidden under similar drapes, the small square table covered by a mantle of deep blue and gold which fell to the floor. Beyond all of this the solitary bit of furnishing was the object on the table whose oddity caught and held his eye; a thin column of crystal like a ten-inch needle, based in a red disc and supporting a hollow cap, the size of an acorn cup, in which was a single stone or bead of glass, he knew not which. He only knew that the thing was alive with the fire in it and blazed red, and he fancied it was a ruby.

He glanced hurriedly about the room, making sure that it was empty. Again his eyes came back to the glowing jewel supported by the thin crystal stem. Now he was conscious of a sweet heavy perfume filling the room, a fragrance new to him and subtly exotic. Everything about him was fantastic, extravagant, absurd, he told himself bluntly, as was everything connected with an absurd woman who did mad things. He looked at the bank notes in his hand. What more insane act than to send an amount of money of this size to a stranger?

The familiarly disturbing feeling that eyes, her eyes, were upon him, came again. He turned short about. She stood just across the room, her back to the motionless curtains. Whence she had come and how, he did not know. She was smiling at him and for the first time he saw her eyes clearly and her dark passionate face and scarlet mouth. He did not know if she were fifteen or twenty-five. The oval face, the curving lips were those of a young maiden; her tall, slender figure was obscured by the loose folds of a snow white garment which fell to the floor about her; her eyes were just now of any age or ageless, unfathomable, and, though they smiled, filled with a sort of mockery which baffled him, confused him, angered him. Upon one point alone there could be no shadow of doubt; from the top of her proudly lifted head with its abundance of black hair wherein a jewel gleamed, to the tips of her exquisite fingers where gleamed many jewels, she was almost unhumanly lovely. She looked foreign, but he could not guess what land had cradled her. Mexico? Why Mexico more than another land? It struck him that she would have seemed alien to any land under the sun. She might have sprung from some race of beings upon another star.

She had marked the look on his face and in her eyes the laughter deepened and the mockery stood higher. He frowned and stepped to the table, tossing down the pad of bank notes.

"That is yours," he told her briefly. "I don't want it and I won't take it."

Then she, too, came forward to the table. Her left hand took up the money swiftly, eagerly, it struck him, and thrust it out of sight somewhere among the folds of her gown. Then finally her laughter parted her lips and the low music of it filled the room. He knew in a flash now that she had never meant to allow her winnings to escape her; that there had been craft in the wording of the message she had sent him; that all along she counted on his coming to her as he had come. She sank into the chair nearest her and indicated the other to him.

"If Señor Kendric will be seated," she said lightly, "I should like to speak with him."

In blazing anger had Kendric come here. Now, seeing clearly just how she had played with him the blood grew hotter in his face and hammered at his temples.

"Señora," he said crisply, "there need be no talk between you and me since we have no business together."

"Señorita," she corrected him curiously. "I am not married."

"Nor is that a matter for us to discuss." He meant, as he desired, to be rude to her. "Since it does not interest me."

"It has interested many men," she laughed at him lightly, but still with that intense probing look filling the black depths of her eyes. "With them it has been a vital matter."

Before he had marked something peculiar about the eyes; now he saw just what it was. They were Oriental, slanting upward slightly toward the white temples. No wonder she had impressed him as foreign. He wondered if she were Persian or Arabian; if in her blood was a strain of Chinese, even?

He gave no sign of having heard her but groped for the door through which he had come. It now, like the rest of the walls, was hidden under the silken hangings which no doubt had fallen into place when the door had closed behind him. He did not remember having shut it; perhaps the old woman in the outer room had done so. And locked it. For when at last his hand found the knob the door would not open.

"What's all this nonsense about?" he demanded. "I want to go."

It was her turn to pretend not to have heard. She sat back idly, looking at him fixedly, smiling at him after her strange fashion.

"I have heard of you," she said at last. "A great deal. I have even seen you once before tonight. I know the sort of man you are. I know how you made your money in Mexico; how you rode with it across the border. I have never known another man like you, Señor Jim Kendric."

"Will you have the door unlocked?" he said. "Or shall I smash it off its hinges?"

"A man with your look and your reputation," she said calmly, "was worth a woman's looking up. When that woman had need for a man." Her eyes were glittering now; she leaned forward, suddenly rigid and tense and breathing hard. "When I have found a man who stakes ten thousand, twenty thousand on one throw and is not moved; who returns ten thousand in rage because a word of pity goes with it, am I to let him go?"

"I don't like the company you keep," said Kendric. "And I don't like your ways of doing business. I guess you'll have to let me go."

"You mean Ruiz Rios?" Her eyes flashed and her two hands clenched. Then she sank back again, laughing. "When you learn to hate him as I do, señor, then will you know what hate means!"

He pressed a knee against the door, near the lock. The hangings getting in his way, he tore them aside. Zoraida Castelmar watched him half in amusement, half in mockery.

"There is a heavy oak bar on the other side," she told him carelessly.

"I have a notion," he flung at her, "to take that white throat of yours in my two hands and choke you!"

The words startled her, seemed to astound, bewilder.

"You think that you—that any man—could do that?" It was hardly more than a whisper full of incredulity.

"Well, I don't suppose that I would, anyway," he admitted. "But look here: I've got some riding ahead of me and I'm dog tired and want a wink of sleep. Suppose we get this foolishness over with. What do you want?"

"I want you. To go with me to my place where there are dangers to me; yes, even to me. I know the man you are and in what I could trust you and in what I could not. I would make your fortune for you." Again she looked curiously at him. "Under the hand of Zoraida Castelmar you could rise high, Señor Kendric."

He shook his head impatiently before she had done and again at the end.

"I am no woman's man," he told her steadily, "and I want no place as any woman's watchdog. Offer me what you please, a thousand dollars a day, and I'll say no."

From its place under his left arm pit he brought out a heavy caliber revolver, toying with it while he spoke. Her look ran from the black metal barrel to his face.

"Do you think you can frighten me?" she demanded.

"I don't mean to try. I'll shoot off the lock and the hinges and if the door still stands up I'll keep on shooting until the hotel man comes and lets me out." He put the muzzle of the gun at the lock.

"Wait!" She sprang to her feet. "I will open for you." She brushed by him and rapped with her knuckles on the door. Beyond was a sound of a bolt being slipped, of a bar grinding in its sockets. "One thing only and you can go: When you come before me again it may be you who begs for favors! And it will be I who grant or withhold as it may appear wise to me."

"Witch, are you?" he jeered. "A professional reader of fortunes? God knows you've got the place fixed up like it!"

"Maybe," she returned serenely, "I am more than witch. Maybe I do read that which is hidden. Quién sabe, Señor Kendric, scorner of ladies? At least," and again her laughter tantalized him, "I knew where to find you tonight; I knew you would win from Ruiz Rios; I knew I would win from you; I knew you would refuse to come to me and then would come. All this I knew when you took your ten thousand from the bank down in Mexico and rode toward the border. Further," and he was baffled to know whether she meant what her words implied or whether she was merely making fun of him, "I have put a charm and a spell over your life from which you are never going to be free. Put as many miles as it pleases you between you and Zoraida Castelmar; she will bring you back to her side at a time no more distant than the end of this same month."

He gave her a contemptuous and angry silence for answer. In the street he looked up at the stars and filled his lungs with an expanding sigh of relief. This companion of Ruiz Rios who paid passionate claim to an intense hatred of the man whom she allowed to escort her here and there, impressed him as no natural woman at all but as something of strange influences, a malign, powerful, implacable spirit incased in the fair body of a slender girl. He told himself fervently that he was glad to be beyond the reach of the black oblique eyes.

Two hours later he was in the saddle, riding knee to knee with Twisty Barlow, headed for San Diego Bay and a man's adventure. "In which, praise be," he muttered under his breath, "there is no room for women." And yet, since strong emotions, like the restless sea, leave their high water marks when they subside, the image of the girl Zoraida held its place in his fancies, to return stubbornly when he banished it, even her words and her laughter echoing in his memory.

"I have put a spell and a charm over your life," she had told him.

"Clap-trap of a charlatan," he growled under his breath. And when Barlow asked what he had said he cried out eagerly:

"We can't get into your old tub and out to sea any too soon for me, old mate."

Whereupon Barlow laughed contentedly.

Of the new moon, a tale of Aztec treasure and a mystery.

ON board the schooner New Moon standing crazily out to sea, with first port of call a nameless, cliff- sheltered sand beach which in his heart he christened from afar Port Adventure, Jim Kendric was richly content. With huge satisfaction he looked upon the sparkling sea, the little vessel which scooned across it, his traveling mate, the big negro and the half-wit Philippine cabin boy. If anything desirable lacked Kendric could not put the name to it.

Few days had been lost getting under way. He had gone straight up to Los Angeles where he had sold his oil shares. They brought him twenty-three hundred dollars and he knocked them down merrily. Now with every step forward his lively interest increased. He bought the rifles and ammunition, shipping them down to Barlow in San Diego. And upon him fell the duty and delight of provisioning for the cruise. As Barlow had put it, the Lord alone knew how long they would be gone, and Jim Kendric meant to take no unnecessary chances. No doubt they could get fish and some game in that land toward which their imaginings already had set full sail, but ham by the stack and bacon by the yard and countless tins of fruit and vegetables made a fair ballast. Kendric spent lavishly and at the end was highly satisfied with the result.

As the New Moon staggered out to sea under an offshore blow, he and Twisty Barlow foregathered in the cabin over the solitary luckily smuggled bottle of champagne.

"The day is auspicious," said Kendric, his rumpled hair on end, his eyes as bright as the dancing water slapping against their hull. "With a hold full of the best in the land, treasure ahead of our bow, humdrum lost in our wake and a seven-foot nigger hanging on to the wheel, what more could a man ask?"

"It's a cinch," agreed Barlow. But, drinking more slowly, he was altogether more thoughtful. "If we get there on time," was his one worry. "If we'd had that ten thousand of yours we'd never have sailed in this antedeluvian raft with a list to starboard like the tower of Pisa."

"Don't growl at the hand that feeds you or the bottom that floats you," grinned Kendric. "It's bad luck."

Nor was Barlow the man to find fault, regret fleetingly though he did. He was in luck to get his hands on any craft and he knew it. The New Moon was an unlovely affair with a bad name among seamen who knew her and no speed or up-to-date engines to brag about; but Barlow himself had leased her and had no doubts of her seaworthiness. She was one of those floating relics of another epoch in shipbuilding which had lingered on until today, undergoing infrequent alterations under many hands. While once she had depended entirely for her headway on her two poles, fore sail set flying, now she lurched ahead answering to the drive of her antiquated internal combustion motor. An essential part of her were Nigger Ben and Philippine Charlie; they knew her and her freakish ways; they were as much a portion of her lop-sided anatomy as were propeller and wheel.

Barlow chuckled as he explained the unwritten terms of his lease.

"Hank Sparley owns her," he said, "and the day Hank paid real money for her is the first day the other man ever got up earlier than Hank, you can gamble on it. Now Hank gets busy gettin' square and he's somehow got her insured for more'n she'll bring in the open market in many a day. Hank figures this deal either of two ways; either I run her nose into the San Diego slip again with a fat fee for him; or else it's Davy Jones for the New Moon and Hank quits with the insurance money."

"Know what barratry is, don't you?" demanded Kendric.

"Sure I know; if I didn't Hank would have told me." Barlow sipped his champagne pleasantly. "But we'll bring her home, never you fret, Headlong. And we'll pay the fee and live like lords on top of it. Hank ain't frettin'. I spun him the yarn, seein' I had to, and he'd of come along himself if he hadn't been sick. Which would have meant a three way split and I'm just as glad he didn't."

Kendric went out on deck and leaned against the wind and watched the water slip away as the schooner rose and settled and fought ahead. Then he strolled to the stern and took a turn at the wheel, joying in the grip of it after a long separation from the old life which it brought surging back into his memory. And while he reaccustomed himself to the work Nigger Ben stood by, watching him jealously and at first with obvious suspicion.

Nigger Ben, as Kendric had intimated, was a man to be proud of on a cruise like this one. If not seven feet tall, at least he had passed the half-way mark between that and six, a hulking, full-blooded African with monster shoulders and half-naked chest and a skull showing under his close-cropped kinks like a gorilla's. He was an anomaly, all taken: he had a voice as high and sweet-toned as a woman singer's; he had an air of extreme brutality and with the animals on board, a ship cat and a canary belonging to Philippine Charlie he was all gentleness; he had by all odds the largest, flattest feet that Kendric had ever seen attached to a man and yet on them he moved quickly and lightly and not without grace; he held the New Moon in a sort of ghostly fear, his eyes all whites when he vowed she was "ha'nted," and yet he loved her with all of the heart in his big black body.

"Sho', she's ha'nted!" he proclaimed vigorously after a while during which he had come to have confidence in the new steersman's knowledge and had been intrigued into conversation. "Don't I know? Black folks knows sooner'n white folks about ha'nts, Cap'n. Ain't I heered all the happenin's dat's done been an' gone an' transcribed on dis here deck? Ain't I seen nothin'? Ain't I felt nothin'? Ain't I spectated when the ha'r on Jezebel's back haz riz straight up an' when she's hunched her back up an' spit when mos' folks wouldn't of saw nothin' a-tall? Sho', she's ha'nted; mos' ships is. But dem ha'nts ain' goin' bodder me so long's I don't bodder dem. Dat's gospel, Cap'n Jim; sho' gospel."

"It's a hand-picked crew, Twisty," conceded Kendric mirthfully when Nigger Ben was again at the wheel and the two adventurers paced forward. "The kind to have at hand on a pirate cruise!"

For Nigger Ben offered both amusement during long hours and skilful service and no end of muscular strength, while, in his own way, Charlie was a jewel. A king of cooks and a man to keep his mouth shut. When left to himself Charlie muttered incessantly under his breath, his mutterings senseless jargon. When addressed his invariable reply was, "Aw," properly inflected to suit the occasion. Thus, with a shake of the head, it meant no; with a nod, yes; with his beaming smile, anything duly enthusiastic. He was not the one to be looked to for treasons, stratagems and spoils. His favorite diversion was whistling sacred tunes to his canary in the galley.

As the New Moon made her brief arc to clear the coast and sagged south through tranquil southern days and starry nights, Kendric and Barlow did much planning and voiced countless surmises, all having to do with what they might or might not find. Barlow got out his maps and indicated as closely as he could the point where they would land, the other point some miles inland where the treasure was.

"Wild land," he said. "Wild, Jim, every foot of it. I've seen what lies north of it and I've seen what lies south of it, and it's the devil's own. And ours, if Escobar's fingers haven't crooked to the feel of it. And if they have, why, then," and he looked fleetingly to the rifles on the cabin wall, "it belongs to the man who is man enough to walk away with it!"

More in detail than at any time before Twisty Barlow told all that he knew of the rumor which they were running down. Escobar was one of the lawless captains of a revolutionary faction who, like his general, had been keeping to the mountainous out-of-the- way places of Mexico for two years. In Lower California, together with half a dozen of his bandit following, he had been taking care of his own skin and at the same time lining his own pockets. It was a time of outlawry and Fernando Escobar was a product of his time. He was never above cutting throats for small recompense, if he glimpsed safety to follow the deed, and knew all of the tricks of holding wealthy citizens of his own or another country for ransoms. Upon one of his recent excursions the bandit captain had raided an old mission church for its candlesticks. With one companion, a lieutenant named Juarez, he had made so thorough a job of tearing things to pieces that the two had discovered a secret which had lain hidden from the passing eyes of worshipful padres for a matter of centuries. It was a secret vault in the adobe wall, masked by a canvas of the Virgin. And in the small compartment were not only a few minor articles which Escobar knew how to turn into money, but some papers. And whenever a bandit, of any land under the sun, stumbles upon papers secretly immured, it is inevitable that he should hastily make himself master of the contents, stirred by a hope of treasure.

"And right enough, he'd found it," said Barlow holding a forgotten match over his pipe. "If there's any truth in it three priests, way back in the fifteen hundreds, stumbled onto enough pagan swag to make a man cry to think about it. Held it accursed, I guess. And didn't need it just then in their business, any way. Just what is it? I don't know. Juarez himself didn't know; Captain Escobar let him get just so far and decided to hog the whole thing and slipped six inches of knife into him. How the poor devil lived to morning, I don't know and I don't care to think about it. But live he did and spilled me the yarn, praying to God every other gasp that I'd beat Fernando Escobar to it. He said he had seen names there to set any man dreaming; the name of Montezuma and Guatomotzin; of Cortes and others. He figured that there was Aztec gold in it; that the three old priests had somehow tumbled on to the hiding place; that they three planned to keep the knowledge among themselves and, when they devoutly judged the time was right, to pass the news on to the Church in Spain.

"I wish Juarez had had time to read the whole works," meditated Barlow. "Anyway he read enough and guessed enough on top of it for me to guess most of the rest while I've been millin' around, getting goin'. Two of the three priests died in a hurry at about the same time, leavin' the other priest the one man in on the know. There was some sort of a plague got 'em; he was scared it was gettin' him, too. So he starts in makin' a long report to the home church, which if he had finished would have been as long as your arm and would of been packed off to Spain and that would of been the last you and me ever heard of it. But it looks like, when he'd written as far as he got, he maybe felt rotten and put it away, intendin' to finish the job the next day. And the plague, smallpox or whatever it was, finished him first."

"Fishy enough, by the sound of it, isn't it?" mused Kendric.

"Fishy, your hat! There's folks would say fishy to a man that stampeded in sayin' he'd found a gold mine. Me, while they guyed him, I'd go take a look-see. And it didn't read fishy to Juarez and it didn't to Fernando Escobar, else why the six inches of knife?"

"Well," said Kendric, "we'll know soon enough. If you can find your way to the place all right?"

"Juarez had a noodle on him," grunted Barlow. "And he was as full of hate as a tick of dog's blood. From the steer he gave me I can find the place all right."

Days and nights went by monotonously, routine merely varying to give place to pipe-in-mouth idleness. But the third night out came an occurrence to break the placidity of the voyage for Kendric, and both to startle him and set him puzzling. He was out on deck in a steamer chair which he had had the lazy forethought to bring, his feet cocked up on the rail, his eyes on the vague expanse about him. There was no moon; the sky was starlit. Barlow had said "Good night" half an hour before; Philippine Charlie was muttering over the wheel; Nigger Ben's voice was crooning from the galley where he was making a friendly call on the canary. The water slipped and slapped and splashed alongside, making pleasant music in the ears of a man who gave free rein to his fancies and let them soar across a handful of centuries, back into the golden day of the last of the Aztec Emperors. The Montezumas had had vast hoards of gold in nuggets and dust and hammered ornaments and vessels; history vouched for that. And it stood to reason that the princes and nobles, fearing the ultimate result of the might of the Spaniards, would have taken steps to secrete some of their treasure before the end came. Why not somewhere in Lower California, hurried away by caravan and canoe to a stronghold far from doomed Mexico City?

He was conscious now of no step upon the deck, no sound to mar the present serene fitness of things. But out of his dreamings he was drawn back abruptly to the swaying, swinging deck of a crazy schooner by the odd, vague feeling that he was not alone.

"Barlow," he called quietly. "That you?"

There was no answer and yet, stronger than before, was the certainty that someone was near at hand, that a pair of eyes were regarding him through the obscurity of the night. So strong was the emotion, and so strongly did it recall the emotion of a few nights ago when he had felt the influence of a strange woman's eyes, that he leaped to his feet. On the instant he half expected to see Zoraida Castelmar standing at his elbow.

What he saw, or thought that he saw, was a vague figure standing against the rail across the deck from him, beyond the corner of the cabin wall. A luminous pair of eyes, glowing through the dark. Kendric was across the deck in a flash. No one was there. He raced sternward, whisked around the pile of freight cluttered about the mast, tripped over a coil of rope and ran forward again. When he still found no one, so strong was the impression made on him that someone had been standing looking at him, he made a stubborn search from prow to stern. Barlow was in bed and looked to be asleep; the Philippine was muttering over the wheel and when Kendric demanded to know if he had seen anything said, "Aw," negatively; Nigger Ben had given over singing and was feeding the canary and freshening its water supply.

Afterwards Kendric realized that all the time while he was racing madly up and down, peering into cabin and galley and nook and corner, there had been a clear image standing uppermost in his mind; the picture of Zoraida Castelmar as she had stood and looked at him when she had said, "I have put a charm and a spell over your life." Now he simply knew that he had the mad thought that she was somewhere on board and that, hide as she would, he would find her. But when he gave up and went sullenly back to his toppled chair, he knew that all he had succeeded in was in making both Nigger Ben and Philippine Charlie marvel. Nigger Ben, he thought sullenly, had come close enough to understanding something of what was in his mind. For the giant African rolled his eyes whitely and said:

"Ha'nts, Cap'n Jim? You been seein' ha'nts, too?"

"What makes you say that, Ben?" demanded Kendric. "Did you see anything?"

Nigger Ben looked fairly inflated with mysterious wisdom. But, thought Kendric, what negro who ever lived would have denied having seen something ghostly? Kendric had searched thoroughly high and low; he had turned over big crates below deck, he had peered up the masts. Now, before settling himself back in his chair, he looked in on Barlow again. Twisty was turning over; his eyes were open.

"I don't want any funny business," said Kendric sternly. "Did you smuggle Zoraida Castelmar on board?"

Barlow blinked at him.

"Who the blazes is Zoraida Castelmar?" he countered. "The cat or the canary?"

Kendric grunted and went out, plumping himself down in his chair. He supposed that he had imagined the whole thing. He had not seen anything definitely; he had merely felt that eyes were watching him; what had seemed a figure across deck might have been the oil coat hanging on a peg or a curtain blowing out of a window. The more he thought over the matter the more assured was he that he had allowed his imaginings to make a fool of him. And by the time the sun flooded the decks next morning he was ready to forget the episode.

They rounded San Lucas one morning, turned north into the gulf

and steered into La Paz where Barlow said he hoped to get a line

on Escobar and where they allowed custom officials an opportunity

to assure themselves that no contraband in the way of much

dreaded rifles and ammunition were being carried into restive

Sonora. "Loco Gringoes out after burro deer," was how the

officials were led to judge them. Barlow, gone several hours,

reported that Escobar had not turned up at the waterfront dives

to which, according to the murdered Juarez, he reported now and

then to keep in touch with his outlaw commander. Steering out

again through the fishing craft and harbor boats, they pounded

the New Moon on toward Port Adventure.

Then came at last the night when Barlow, looking hard mouthed and eager, announced that in a few hours they would drop anchor and go ashore to see what they would see. Nigger Ben and Philippine Charlie were instructed gravely. They were to remain on board and were to maintain a suspicious reserve toward all strangers, denying them foothold on deck.

"The gents who'd be apt to make you a call," Barlow told them impressively, "would cut your throats for a side of bacon. You boys keep watches day and night. When we get back into San Diego Bay, if you do your duties, you both get fifty dollars on top of your wages."

It was shortly before they hoisted the anchor overboard to wait for dawn that for the second time Kendric felt again that oddly disturbing sense of hidden eyes spying at him. Again he was alone, standing forward, peering into the darkness, trying to make some sort of detail out of the black wall ahead which Barlow had told him was a long line of cliff. As before Charlie was at the wheel while Nigger Ben was listening to instructions from Barlow aft of the cabin. The voices came faint against the gulf wind to Kendric. The words he did not hear since all of his mental force was bent to determine what it was that gave him that uncanny feeling of eyes, the eyes of Zoraida Castelmar, in the dark.

This time he was guarded in his actions. He stood still a moment, his jaw set, only his eyes turning to right and left. As he had asked himself countless times already so now did he put the question again: "How could a man feel a thing like that?" At his age was he developing nerves and insane fancies? At any rate the sensation was strong, compelling. Making no sound, he turned and stared into the darkness on all sides. He saw no one.

Suddenly, startling him so that his taut muscles jumped involuntarily, came an excited shout from Nigger Ben.

"Ha'nts, Cap'n Barlow! Oh, my Gawd, save me now! Looky dar! Looky dar! It's a lady g-g-ghost! Oh, my Gawd, save me now!"

Kendric ran back. Nigger Ben was clutching wildly at Barlow's arm.

"You superstitious old fool," growled Barlow. "It's only that piece of torn sail flappin' that Charlie was goin' to sew. Can't you see? I thought you weren't afraid of the New Moon's ha'nts, any way."

Nigger Ben shifted his big feet uneasily and little by little crept forward to look at the flapping bit of sail cloth. Slowly his courage returned to him. He hadn't been afraid at all, he declared, but just sort of shook up, seeing the thing all of a sudden that way. Kendric passed on as though nothing had happened, as he reasoned perhaps nothing had. But just the same he made his second quiet search, in the end finding nothing. But as he went back to his place up deck he turned the matter over and over in mind stubbornly. Coincidences were all right enough, but reasonable explanations lay back of them. If a man could only see just where the explanation lay.

He sought to reason logically; if in truth someone had been standing looking at him, if Nigger Ben had seen something other than the flapping canvas, then that someone or something had gone aboard the New Moon at San Diego and had made the entire cruise with them. That could hardly have been done without Barlow's knowledge. Two points struck him then. First, Barlow had demanded who Zoraida Castelmar was; had not Barlow even learned the name of the girl of the pearls? Second, it recurred to him that Barlow had followed her to the hotel in the border town, had even had word with her, since he had brought Kendric a message. Why had Barlow gone to the hotel at all? His explanation at the time had been reasonable enough; he had said that he had gone to get a room. But now Kendric remembered how Barlow, on that same night, had expressed his determination to be riding by moonrise! What would he have done with a hotel room?

But slowly the dawn was coming, the ragged shore was revealing

itself, Barlow was calling for help with the small boat. Kendric

shrugged his shoulders and kept his mouth shut.

Indicating that that which appears the

earthly

paradise may prove quite another sort of place.

A STRIP of white beach three hundred feet long, a score of paces across at its widest, with black barren cliffs guarding it and the faint pink dawn slowly growing a deeper rose over it, such was the port of adventure into which nosed the row boat bringing Jim Kendric and Twisty Barlow treasure seeking. In the stern crouched Nigger Ben, come ashore in order to row the boat back to the New Moon, his eyes bulging with wonderment that men should come all the way from San Diego to disembark upon so solitary a spot. The dingey shoved its nose into the sand, Kendric and Barlow carrying their small packs and rifles sprang out, Nigger Ben shook his head and pushed off again.

"Up the cliffs the easiest way," cried Barlow, his eyes shining with excitement. "Up there I'll get my bearin's and we'll steer a straight-string line for what's ahead, Headlong, old mate! Step lively is the word now while it's cool. And by noon, if we're in luck—"

He left the rest to any man's imagination and hastened across the sand and to the rock wall. But more forbidding than ever rose the cliffs against the path of men who did not know their every crevice, and it was full day and the sun was up before they came panting to the top. Down went packs, with two heaving- chested, bright-eyed men atop of them, while Barlow, compass in hand, got his bearings.

The devil's own he had named this country from afar; the devil's own it extended itself, naked and dry and desolate before their questing eyes, a weary land, sun-smitten, broken, looking deserted of God and man. As far as they could see there were no trees, little growth of any kind, no birds, no grazing beasts. Just swell after swell of arid lands, here and there cut by ancient gorges, tumbled over by heaps of black rocks, swept clean of dust on the high places by racing winds, piled high with sand and small stones in the depressions. Where growing things thrust up their heads, they were the harsh, fanged and envenomed growth of desert places. The place had an air of unholiness in the light of the new day. A thorn, as Barlow turned carelessly, tore the skin on the back of his hand painfully. The parent stem had an evil look and he cursed it as though it had been a conscious malign agent, and struck at it with his clubbed rifle. From the place where the branch was wrenched away exuded a slow red sticky ooze like coagulating blood.