RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

Roy Glashan's Library.

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

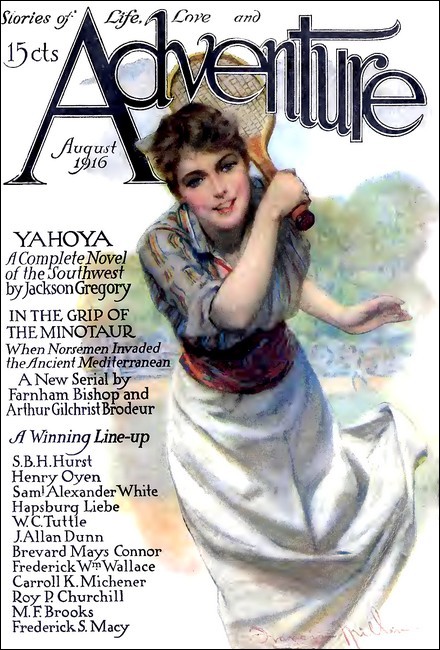

Adventure, August 1916, with "Yahoya"/p>

A book-length story of unusual power telling of a determined man who strikes back into the heart of the Great American Desert. He seeks gold. He finds Yahoya and love. She is too remarkable a girl to miss knowing. And the strange desert race of Indians, with their quaint customs and beliefs, lift the story far above ordinary fiction.

BREATHLESS waiting—for what? Blind terror—of what thing? The waiting interminably prolonged because the man did not know what was the thing he must expect; terror more hideous than mere fear because it was the unknown which menaced. In all of the universe there was now only this one thing which mattered; all else was forgotten. And what was it? To the man the desert in which he lay, helpless and hopeless, had ceased to exist. He no longer saw the hot sky, the molten sun, the limitless stretch of sand, cactus and blistering rock. He saw only the eyes which watched him.

They seemed staring at him terribly, two eyes which were steady, unwinking, immeasurable, inscrutable twin pools of ink. At one instant they became to his fevered fancy the fierce eyes of a savage, desert born and bred, observing his death with a curiosity at once unmoved and strangely childlike. Then he thought that he saw the eyes expand, dilate, grow enormous, the eyes of some misshapen monster thing, into whose lair he was the first man since the first dawn to penetrate. Northrup's reeling brain groped insanely for the visualization of the great body to which the eyes must belong, and which he could not see.

Then, with unconsciousness seeking to cast its black mantle over the man who struggled against it, the eyes seemed suddenly to change again, to grow smaller, smaller, rounder, until they were the evil eyes of the desert's chief curse, Sika-tcua, the yellow rattlesnake. He found himself groping, wondering dully if there were truth in the old tale, if a snake might charm a man and draw him closer and ever closer to the quick forked tongue? He set his two hands out in front of his pain-twisted body, sinking them in the blistering sand, seeking to stop the impulse which had crept upon him.

He knew that the gray wolf at times came down from the ridges; that the panther followed the track of the mule-deer here; that the gaunt, mean-spirited coyote was not averse to sitting patiently and watching the slow death of one of his superior animals, waiting. His tortured thoughts of a coyote were no less terrible than the others now.

All day long the steep rays of the desert sun had smitten at him pitilessly; all day the red-black lava rocks among which he lay had burnt his body; all day the flying sand carried upon the hot blast of wind had seared and scorched his bloodshot eyeballs. It had been in the first, white dawn that he had fallen. Encompassed through the hesitant hours by the material threats of the desert, he had not once groaned. It was Northrup's way to suffer in silence.

But now the unknown had swept the last vestiges of reality aside; it had the seeming of creeping close about him from all quarters of a veritable mundane hell. Halfcrazed with pain in the semi-consciousness which he was always fighting for, it was as if he had passed out of the old life already and into a fierce land of sorcery. Of only one thing could he be certain now—the pair of steady black eyes watching him through a fissure in the rocks above.

Had it been an hour since he had called out? Or had many circling eons reeled drunkenly over him since his voice, disturbing the vast silence, had choked back into his throat? He did not know.

He knew that he had called out, thinking that these were the eyes of a man, a human being like himself, that he had begged for help. He knew that there had come no answer, that the eyes had watched him with the same steady curiosity. He knew that he had shouted and that long ago he had grown still.

Once he had painfully dragged from its holster the automatic which had not been shaken loose in his fall; when, with a blind anger upon him, he had lifted it a little the two eyes were gone. When it had fallen from his weak grasp the two eyes were back there, watching him with the same cursed steadiness.

In a moment of half delirium the quick suspicion had come to him that it was Strang, Strang who had deserted him in his helplessness, robbing him of the scant supply of water to drive on madly, seeking to gain the next water-hole. But no; Strang wouldn't be tarrying here, watching him die. Strang wouldn't even be so much as thinking of him. Strang was taking his own chance, his one chance, and pushing on desperately.

Northrup had lived through the day praying dumbly for the coming coolness of the night. Now the night was coming and he was afraid of it.

He twisted his head a little to look at the sun. He was less sure that the sun was setting than that this was the last time he would ever look upon it. In the west, a riot of color; the sun was sinking through a mist which seemed to rise from a sea of blood. Night was at hand. And with the sign of its coming the sense was strong upon him of the unknown, terror-infested, creeping closer about him.

"Strang might have waited," he thought. His swollen lips and dry, aching throat were long ago past utterance. But he was not past saying within himself:

"I won't die until I know to what thing those eyes belong!" There was much stubbornness in Sax Northrup.

IT WAS not meant that he should die yet. And so he did not

die. It was meant that he should see Strang again, that he should

stumble upon a century-long hidden secret of the desert. So he

lived on where another man would have died.

The silver desert moon was two hours high in the purple sky when he realized that he had lost consciousness and found it again. Before he thought of that he thought of the eyes which had so long watched him; before he saw the moon he saw them. They were over him now, just over him, less than a yard away.

He stared upward through the night light curiously. There was sufficient light for him to see clearly, but his brain cleared slowly.

In seeking to guess the riddle of the two eyes, to conjure up the thing to which they belonged, he had never thought of a woman. And yet a woman it was bending over him, though his mind took long in clearing enough for him to be sure of that.

She was old, unthinkably old, unbelievably ugly. She might have been the barren deity of a barren land. She might have been a skeleton, with the skin upon the fleshless skull tanned by sun and wind through hundreds of years until it was leather. Squatting motionless over him she did not seem to be a living, breathing being until he saw the eyes, the same steady, unwinking black pools of ink with the glint of the moon in them.

The moment was uncanny. The moonlight dragged weird figures from the desert floor, charging them with ghostly unreality. The thing squatting above him might have been a sister thing to the fantastic shapes the moon made everywhere about her.

Northrup shivered. His reason, making its way back through the darkness of his stupor, had not fully reinstated itself. He knew that here in this strange land of aridity there could be no such thing as decomposition. When death came it struck its blow cleanly, unattended by decay. Air, sun, wind, when they had their way undisputed, made of the dead such a thing as that which bent over him. If no prowling beast came to rend apart, then the body would last throughout generations, perhaps centuries.

Fear comes in many guises but never with so cold a clutch as when whispering of the supernatural. At the shock from the pictures whipped up before him by his own imaginings, Northrup again lost consciousness.

Later—he did not know how much later —it seemed quite natural for him to feel that some one was moving about him. He realized dimly that it couldn't be Strang, for Strang had gone on. He knew that it must be the thousand-year-old woman who had come out of the nowhere, riding on a moon-ray, perhaps; who, when she was done pottering around him, would go back the way she had come. He didn't try to turn his head to watch her because he knew that he hadn't the strength left in him.

She had slipped something soft under his shoulders, had even managed to turn his great body a little, making it lie a fraction less painfully. And she had brought him water. That was a joke on Strang! He had gone on furiously, lugging three or four warm cupfuls in his canteen, thinking that there was no other drop to be had until one had crossed many miles of desert.

There came intervals during which Northrup was oblivious to everything about him, brief spaces of time when he awoke to both realization and curiosity. But for the most part he existed in a condition which was a sort of dim border-line between consciousness and stupor. He accepted the present as matter of fact, forgot the past and did not seek to speculate upon the future.

For days he lay upon the talus, upon the first of whose ragged boulders he had fallen from the cliffs of porphyry above. The old woman, moving with the feebleness and the slowness of a Winter sunbeam, forced her shaking hands to construct a shelter over the spot where he lay.

A ragged, home-made cotton blanket stretched above him from rock to rock, a robe of rabbit-skins made at once cover and bed. She brought him water in a rude olla of sun-baked clay, administered gruelly messes made from corn-meal, attending him after the first with a faithfulness like a shepherd dog's. Where she went for the water, what was the source of her food supply, he did not know.

The silence was seldom broken. For hours at a time she would squat near him, her blanket drawn about her shoulders, over her head, her hands lost in its folds, her ancient face turned upon him in an expressionless stare. When there arose absolute need for speech there was no difficulty in understanding each other.

Northrup, through many years of going up and down among people of her breed, had come to understand the tongue of the Indians of Walpi, Oraibe, Taos. When he had called her "So Wuhti," which is the Hopi for Old Woman or Grandmother, she had understood. She had named him "Bahana" White Man, and the ceremony of introduction was complete.

For a long time Northrup, lying grim and quiet, thought that by struggling to keep on living he was but postponing the hour of his death a few hours. Among his lesser injuries he thought that he could count the fracture of his left arm. He could only speculate upon the extent of injury done internally.

Had he been in a hospital with capable physician and nurses attending him there might be a chance. But here, with the halfcooked food a wild woman brought, with the nauseating decoctions which she extracted from he knew not what plants or roots, with a bed of lava rock, his chance seemed little enough. He watched her making his medicines, heating the sticky liquid over a greasewood fire, then setting it aside that she might sing over it and so make it "good medicine," and imagined that the mixture would be about as efficacious as her singing. The latter was horrible enough. But he got well.

And they grew to be companions of a sort, as perhaps nearly any two of God's creatures would if set alone in the world. The fact that the old hag was living here and absolutely alone, that she seemed contented to be here and looked for no other company than her own until Northrup had come, aroused curiosity after a little.

He soon found many questions to ask. And during the five months which passed before he was a strong man again—and one must be certain of his full strength before he seeks to walk out into the desert with the little water he can carry and the knowledge that he must travel forty miles to the first water- hole—he learned much from So Wuhti.

HAD not So Wuhti led him at last to her abode, Northrup would never have found it. It was slow climbing for them both, the woman weighted down by close to a century of years, the man still so weak that a little exertion set him trembling throughout his wasted body.

The chosen chamber of So Wuhti was close up to the cliff-tops, a roughly gouged-out room in the rocks, to be approached only by a steep trail from below. It was constructed cunningly in a great fissure so that while from it the old woman might look out over the desert, it would be a keen eye down there to discover her.

Upon the floor lay So Wuhti's bed, a tumbled pile of cotton blankets of native weave and a rabbit-skin robe. In a smokeblackened corner were a few charred sticks and bits of brush; here and there were sun-baked clay utensils, for the most part black and cracked. A few strings of dried meat, a heap of shelled corn, a pot of water, a prayer-stick against the wall by the bed completed the equipment of the room.

From So Wuhti's boudoir—Northrup always called it that and So Wuhti seemed greatly pleased with the name—it was no trick to come to the top of the cliffs by means of the short ladder. And here one came upon that wonder of the desert of which a thousand tongues have told since first the old Spanish conquistadores dipped into it, which countless artists have sought to catch upon their brushes.

For a hundred miles in all directions the eye passed over gray floor, sweeping up into loma and mesa, the magic desert colorings over it all, deep blues and glittering bronzes, the snow white of drifted sands, the gray-green of cactus and brush, the brick reds of rocky precipices. Through the clear, dry air the eye sped instantly over waterless distances where a man might find slow death in crossing.

Here, just at the cliff's edge, Northrup found again the half- expected, the tumbled ruins of an ancient watch-tower. His mind toyed with the pictures which his fancies suggested.

The vision arose of a gaunt, cat-quick sentinel, hawk-eyed, skin beaten into glistening copper from the sun, keeping guard here while his brothers slept in a younger century; starting up as, many miles away across the rolling floor of desert sand and scrubby growth he caught a quick glimpse of an invading enemy; cupping his hands to his mouth to send outward and downward his warning shout; kindling the ever-ready pile of greasewood fagots to send out over the land other messages of warning, voiceless, lightning-winged. And, as if the old time were not yet dead though the watch-tower of stone was crumbling, he saw a pile of dry greasewood and a black smudge of smoke against the side of the one upstanding slab of stone.

He went back, down to So Wuhti, wondering.

As, little by little, strength came back into his emaciated body, he grew impatient for the time when he might dare to take up the trail again. But a month passed and he knew that it would be as mad a thing to try to move on as to climb to the cliff-tops and leap downward.

There was water here; So Wuhti brought it laboriously from a hidden spring far back and deep down in the great fissure in the rock wall. If he turned back, he knew there was no more water within thirty miles; if he went on it was a gamble if he would find water at the end of forty miles. So he waited for his strength to come back to him.

Slowly, so slowly that perhaps she was never aware of it, So Wuhti's silence slipped from her. She came, in her loneliness, to feel a strange affection for the big-bodied Bahana with his white skin, his yellow hair and blue eyes.

She had never seen a man like him. At first she seemed a little in awe of him, a little afraid of him. In those first weeks she would sit and watch him suspiciously, her lips locked, her eyes bright with speculation. But, as the Hopi legends have it, woman is the daughter of Yahpa, the Mocking-bird, and so, since her father is so great a talker, may not long remain silent. The legends of her forefathers were scripture to So Wuhti.

So it turned out that as they sat together in the old woman's boudoir or upon the cliff-tops, the slow hours passed to the throaty monotone of So Wuhti's talk while Northrup smoked her tobacco in his pipe and listened. It took him no great time to recognize the fact that the old woman was half crazed—a brooding, solitary life and a mind filled with superstitions having worked their way with her.

In the main her conversation was an ingenious fabric of lies told with rare semblance of truth. As if she were recounting some minor happening of the day, she told of a visit she had had from Haruing Wuhti, chief deity of the Hopi polytheism. The goddess, coming up out of the sea, had come across the desert, running swifter than an antelope. So beautiful was she that she had hurt So Wuhti's eyes with her beauty. Aliksai! Listen, Bahana! She is like a soft white maiden, Haruing Wuhti, her hair yellow like the squash blossom, yellower than yours. Her eyes are like turquoises, her mouth as red as a sunset through the sand-storm. She came swiftly at So Wuhti's call. Through the night the goddess sat there, So Wuhti here, and they talked.

So Wuhti shook her head, mumbled, grew silent. The Bahana was not to hear the things of which Haruing Wuhti and So Wuhti spoke in the night.

She explained her presence alone here. She told him of it twice, once in answer to his question, once volunteering the information. Had she gone into the matter a third time Northrup had no doubt that he would then have had three instead of merely two distinct explanations to choose from.

In the first account Northrup found many traces of ancient Indian religions. So Wuhti spoke familiarly of the beginnings of the world which, while she admitted that it was Haruing Wuhti and the Sun who had done the actual work, she herself witnessed.

She called Northrup's attention to the fact that the spot in which he and she were was the top of the world. Hence it became clear that it was very distantly remote from the abiding-place of the chief goddess. Being so far away the goddess must have some one in whom she could trust to see that everything went right. Consequently So Wuhti, a very great favorite with Haruing Wuhti, was stationed here. When there was need she built signal fires at the ruined watch-tower and Haruing saw and understood the matter.

If Northrup didn't take a great deal of stock in this explanation, he had the other one: Further in the desert, so far and across such a waterless tract that the white man could only send his hungry eyes traveling into it, was a land where there were hidden cities. The gods of the underworld had built these cities. Then they had given them to a people, the people of So Wuhti. There were seven of these cities, the Seven Cities of Chebo. (Northrup smiled as he saw a trace of the old legend told by the early Spanish explorers of the Seven Cities of Cibola.) They were very rich cities, having much silver, many turquoises and of late years much gold, which they made into rings and bracelets, the chiefs having cups and plates of gold.

In order that they might remain hidden from the greed of the white men and from the jealousy of other tribes, they set sentinels out through the desert, a hundred miles away. Such a sentinel was So Wuhti. She had but to set fire to the fagots upon the cliffs and the chiefs of the Hidden Cities of Chebo would understand.

Northrup must understand that the gods and goddesses were very close to the people of So Wuhti. Didn't Haruing Wuhti herself come here to chat with So Wuhti, to eat piki with her? It was so.

And by living here alone So Wuhti was doing a kindness at once to her people of Chebo and to her sovereign deity. The priest had told her. As long as she lived she would watch here. When she was to die she would build a big fire which would carry the word across the desert so that another might be sent to take her place. And then Haruing Wuhti would come for her and throw her cloak about her and So Wuhti would be a young mana again, living always where the Big River breaks through the crust and goes into the underworld where the gods live.

Though the old woman's rambling stories with their innumerable digressions and repetitions soon ceased to interest him, Northrup did not fill his canteen and move on when at last he felt that he was his old, strong self. Half-crazed old savage that she was, So Wuhti was none the less human. Nor was there any denying his obligation to her. Had it not been for her he would be now only what the coyotes and strong-beaked birds would have left of him. And now, strong enough to attempt the passage of the desert, he could not fail to see that So Wuhti was coming quickly to the end of her life, and he could not bear the thought of going on heartlessly, leaving her to die alone.

SHE looked at him curiously many times during those last few days together. She, too, had seen her death coming to her at last and looked at it with steady, curious eyes. She was not afraid, she did not seem sorry to go. She was certain that Haruing Wuhti was making her future existences her own concern. It was all arranged.

She had never manifested a hint of emotion of any kind since he had seen her beady eyes peering at him through the crack in the rocks and now he had been here upward of six months. He did not expect for a sign of emotion now. Too long had she had the opportunity of looking forward to the end to be greatly perturbed by it now that it was at hand.

It came with a little shock to him one day that So Wuhti was all human, after all. Out of a still silence by the ruined tower she had moved to him quickly, her crooked claw of a hand suddenly fastening about his forearm.

"You're a good man, Bahana," she said, her eyes unusually bright upon his. "Many days ago you were ready to go. You wait that So Wuhti does not die alone like the coyote. Askwali! I thank you. Haruing Wuhti will bring you many good things. I will tell her."

With all of her madness she was not without wisdom. She set her chamber in order that night; Northrup had the suspicion that in honor of the occasion she even went so far as to bathe. Then, when the first stars were coming out she made a trembling way to the cliff-tops, Northrup helping her up the short ladder.

In the faint light here Northrup saw how she had arranged her hair, and the thing came to him with something of a shock. She had done it up into two whorls, one at each ear, the imitation of the squash blossom which with the Zuni people tells the time when a maiden has ripened into the first blush of womanhood. So Wuhti was ready for the coming of Haruing Wuhti, for the time when again she would be beautiful—a young mana.

When at last the great fire, which at her command he had kindled, had burnt down, Northrup went slowly back into the stone chamber which had so long been So Wuhti's and which was never again to know her presence. As he looked at her blankets laid in order, folded by hands into which the chill had already crept, when he saw the broken jugs and crocks set in their neat row, a sudden moisture came into his eyes. So Wuhti had been good to him and she was dead. So Wuhti was gone and he was lonely!

In the coolness of the night, having only the stars to guide him, his canteen freshly filled, he pushed on, out into the desert.

ONLY because of the great stubbornness which was a part of him, and because of the unswerving purpose which had grown to be a part of that stubbornness, did Sax Northrup battle on with the desert instead of turning back now. For fight was it to be at every step, with the ultimate outcome hidden upon the knees of the barren gods of the Southwestern Sahara.

Already was he in a land into which men do not come, where perhaps before him ten white men had not ventured since the time of Fray Marcos close to four hundred years ago. Here was a region from which a man might bring back with him nothing but a tale of suffering; where often enough he might find nothing but a horrible death. And yet Northrup, seeking that which he sought, with his eyes open went on.

But, thinking that he knew the desert, he came to learn that he had never known it. Alone in the silence he came to understand a little the majesty and power of God.

Day after day, night after night, he saw these things made tangible in the sweep of the sandy floor, in the stern grandeur of the uplifted walls of rock. Through the fragment of eternal silence through which he fought his way he felt these things. He felt himself a small figure alone in a strange, hard world.

Grandeur, majesty, sublimity—he knew them to be of the desert. But they were not the essence of it. Its supreme quality, seen at all times and not to be mistaken, was its savage fierceness. The desert is no hypocrite; its teeth are always bared, poisoned teeth in a snarl at the intruder, threatening no less its own offspring. It is the land of the iron fang.

As he battled on, always was he in the heart of another battle which had outworn the youth of time. A struggle to the death, without quarter, and oh, the silence of it! Here about him was no created thing which the desert did not strive to kill. Here was no living thing upon all the terrible surface which did not strive to kill its brother creation.

Life here had never gotten beyond its primary, elemental phase. It was, over and over, the frenzied seeking to inflict death in order that the conqueror might live; to live in order to kill; to deal death and to flee from death.

The fierce brood of things struggling for existence even from the very womb of their terrible mother were without exception a brood armored and armed, the desert coyote a murderer with a coward's heart and a madman's cunning; the wildcat a machine for assassination; the gray wolf so much cold steel, tireless, swift, merciless, the spirit of slaughter cast into flesh and blood; the rattlesnake as deadly as death itself; even the harsh growth of vegetation, bound to earth by its iron roots so that it might not spring to attack or flee from its enemy, was armed with its thousand knife-thorns to tear at flesh and bite at bone.

Everywhere Northrup sensed the silent, unending struggle, the preying of living things upon one another, the warring of the land which bore them against them all. And he came to know what it meant for a human being to enter this scene of natural warfare.

Like the man and wife in Molière's comedy, fighting like cat and dog but ready to turn united against the interloper into their domestic realm, so these desert things seemed to combine with horrible power against the stranger in their realm, the Bahana who had dared set foot upon the changing sands.

The sun tortured him, thirst came to madden him, spiked cacti tore at his bleeding hands, wind parched, sand blinded him, the rattlesnake and the poisoned spiders threatened when he slept or woke.

As the still, hot days went on he came almost to believe himself in a veritable land of sorcery, of witchcraft, of black magic. It became to him the demesne of the unearthly, the home of illusion, a region bewitched and bewitching him who looked upon it, the one place in the world where the supernatural was a part of nature.

He saw the sun changed into a monster bloodstone, the moon into a disk of white silver, the sober skies into a riot of colors, burning reds, rich purples, greens and golds. His eyes told him of a stretch of level lands which were to be crossed in two hours and he struggled across them for two days; told him of mountains five miles away which his brain, wise from past experience, knew were seventy miles from him.

He walked toward misty veils of pale pink and deep rose; they melted away from him, withdrawing, showing him the barren places which had been softened only in the seeming. He saw things which did not exist, built out of nothingness as by the touch of a magician's wand, hovering in the air. What looked like a lake before him, cool waters stirring softly to a cool breeze, was nothingness, a bit of trickery of the air. To see trees, mountains where they were not, turned topsy-turvy, became a commonplace.

There was one day when, hoarding the little water in his canteen, hurrying on to the vague promise of a water-hole, he saw quick clouds gathering in the sky, black with the rain in them. Caught in a driving current high above, the clouds passed over him. Saturated, struck by a cooler current of air, they burst open like huge water-bags, spilling the rain. He saw it fall in a steep slant. It was raining up there in big drops. And yet no single drop of water came down to him. In the dry air through which it plunged hissing downward it disappeared, drunk up by the air itself as a drop of moisture is drunk up by a dry sand bank. Merely the natural thing here, yet looking like enchantment.

Northrup was a man essentially given to strong, vigorous action rather than to fanciful musings. And yet here, with aught of action denied him beyond the monotonous driving of one boot after the other into loose sand, or up lava-strewn slopes, or about and through clumps of desert vegetation, for weeks his mind was the home of strange imaginings.

He found himself wondering, at first lightly, but at times with a soberness which startled him when he recognized it, if there did exist supernatural forces of which man had no understanding. The thought came to him that such a force had drawn him, Sax Northrup, from the beaten thoroughfares of white men into this empty land. What had brought him here while the men whom he had known of his class and type were driving their motors over smooth roads, dining in comfortable cafés, sleeping upon soft beds and otherwise disporting themselves as befitted the city-bred? What indeed but the wild tale of a dying Indian down in Santa Fe?

The thing which takes men by the hair and drags them to the hidden corners of the four quarters of the world is generally the same thing in whatever garb it chooses to wear—the lure of gold. It had brought him, him and Strang, here.

Through many a day there stood between Northrup and death a scrap of paper and a hope that the paper did not lie. In the main it had told the truth thus far. If, later on, it lied to him, why, then he'd do what many another man has done on the desert, die for want of water.

He had the way, before leaving any water-hole upon which he had come, of taking the paper out of his pocket, studying it thoughtfully, looking up from it across the bleak stretches, out toward a steep-walled mesa or the clear-cut ridges of distant mountains. And always his frowning eyes came back from the old story of sand, lava-rock, gorge, precipice and gray-green desert growth to the bit of paper in his hand.

Already was it more precious to him than the gold which he hoped it might lead him to.

"For if through some mischance I should lose this," he admitted to himself often enough, "why, then, I'd be a dead man in forty-eight, maybe in twenty-four hours!"

A STRANGE map this, which Northrup carried rolled and thrust

into an empty rifle-cartridge for safety. That he had made it

himself did not in any way make it seem to him infallible. The

Indian, dying in Santa, had told him the way to follow and

Northrup had made the rough map from the Indian's words. And he

had known, from the time that he made his first step upon the

long trail, that, trusting himself upon it, having only that to

guide him deep into the secret heart of the land of little water,

was as foolhardy a thing as he had ever done in all the years of

a foolhardy existence. But there had been the golden lure.

As he crouched by some lonely waterhole, trying to get his big body into a scant patch of shade, his eyes turned upon his crude map, Northrup's thoughts had grown into the way of flying back to the manner of this thing coming to him at all.

He had been in Santa Fe, chafing under a short enforced idleness, restive, eager for whatever might come next on the cards. There he had found Strang; or to be exact Strang had found him. Northrup hadn't particularly liked him from the beginning. But men of his class were few and hard to find hereabouts and Strang was not without a certain insinuating way and a perseverance almost as great as Northrup's own.

Besides, Strang in the beginning of the matter had been in trouble and Northrup in his wide-handed, generous way had befriended him. The ridding oneself of a person to whom one has done a kindness is not without its difficulties.

At any rate Northrup and Strang had been together watching a game of cards in an adobe saloon when the Indian had first come into their stories. The native, a tall, gaunt, sinewy fellow thrusting through a knot of men at the door had come almost at a run to where they were.

"Sax Northrup?" he had asked swiftly.

Even before Northrup could answer, there came a little whirring sound and a small arrow, tipped with a blue feather, evidently fired through the open window from without, drove deep into the Indian's side. His eyes, turned toward the square of darkness, were horrible. And Northrup, bending over him quickly, had seen no pain, just wicked, venemous hatred in them. The arrow was poisoned and the wounded man knew it.

In a little room just off the saloon the Indian told his story to Northrup and Strang. To the latter because he asked to stay, since the Indian made no objection, because Northrup had no reason for privacy in the matter.

That night the Indian died. But first he had told his story. Northrup, looking his incredulity, saw a keenness of eagerness in Strang's eyes. And in the end the Indian convinced them both.

"Look!" he had panted, speaking as swiftly as he might in the Hopi tongue. "There is more—like this!"

He had managed to squirm over on his bed, jerking weakly at something tied about his body under his shirt. It was Strang's eager hands which did the actual work. There was a little bag there, made rudely from a piece of buckskin. And in the bag were two gold nuggets and half a dozen turquoises.

"But why do you give this to me?" Northrup had demanded. "You came here looking for me. I don't know you."

"I know you," the Indian had answered. "Where hard things get done, I hear your name. Where dangerous things are, I hear your name. A man must be like you to go there. Now listen: get paper quick; make marks on it while I tell you."

And so Northrup had made his map.

"It is many miles, more than two hundred, before you come to the beginning of the trail," the Indian had said. "Red Rock Gully, you know? And Badger Gulch beyond, and Coyote Gap on the other side, they are known to you."

"Yes," Northrup had answered.

"Then, Bahana, listen. Listen with both ears!"

He made his description of the trail to travel swiftly, seeming to have each great or minor direction in mind, as if he had carefully arranged every detail already. From Coyote Gap Northrup was to go straight toward the rising sun where it lifted between the two peaks in the Spanish Mountains, the peaks known as Los Dos Hermanos. There, in the pass, was water. It was not over ten miles from Coyote Gap.

Then, before going further, the Indian had wriggled up, his back against the wall, and had seized pencil and paper from Northrup.

"Look," he had said, making a little mark. "This is where the north star is. You can always find the place of the Kwinae Wuhtaka—North Old Man—on the desert? Day and night, by the stars?"

Northrup nodded. Already he had begun to feel something of the earnestness which seemed to possess the Indian and which at the jump had gotten into Strang's blood. The Indian grunted his satisfaction.

"Now," the Hopi had said at the end, showing the same readiness which So Wuhti showed months later to meet the Skeleton Old Man half-way, "it is done. You will go, for there is gold at the end of it all, and where there is gold, if it is under hot rocks, a white man will go. The other Bahana," looking shrewdly into Strang's brightening eyes, "will go also. You will make two writings, so that if the wind steals one you will not die for water."

"Oh, I suppose we'll go," had been Northrup's answer. "But look here, my friend—I want to know what's back of this? Why are you so infernally set upon anybody using the stuff you can't use yourself?"

The Hopi's last earthly grin was full of malice.

"It is because I hate Tiyo," had been the full of his explanation.

THE question, "Who the devil is Tiyo?" had come quite naturally to Northrup's lips when he had first heard the name. But now it had long ago been crowded aside, all but forgotten. In due time he'd know, or else he'd never know, and in the meantime he had other matters to ponder upon.

It had been at a spot some ten miles in a general northeasterly direction from the point indicated on his map by the words "Cañon—Pines—Mountain Ridge," that he had had his mishap. Here Strang had left him. Here So Wuhti had appeared before him like a black witch, to become his good angel.

When he had pushed on again he had found that, day after day, the country unfolding before him became more menacing. He found no water of any description, excepting at those spots where little crosses upon his map indicated it. He slept and woke with the knowledge that should he miss one of these holes, should the Indian have lied to him, should the drifting sands have covered and blotted out a spring, why then the tale was told for Sax Northrup.

And there was another thing, a thing which multiplied a hundredfold the danger which lay about him: While the figures upon his map told him definitely that it was ten or twenty-five miles between waterholes it was, after all, just guesswork—guesswork first on the part of an Indian runner, guesswork on his own part; guesswork where the penalty for a mistake might well be death. No, as he went on, there was not much call to puzzle over the question, "Who is Tiyo?"

"In a race across the desert with the 'Skeleton Old Man' it is well to travel light!" Northrup remembered that bit of advice. From So Wuhti's caves he had brought water, corn-meal, a little dried meat which she informed him was rabbit meat but concerning which he had his doubt. At any rate it was meat.

When he came to a pool in a dry creek-bed, a spring great enough to give life to a little splotch of green stuff under the cliffs, he rested, sometimes a day or two if there was a hard pull ahead of him. Here he found animal life, cotton-tails and jack-rabbits for the most part and a few birds. They were tame, having no doubt never set their bright round eyes upon a thing which walked upright as he did, and they were curious.

What he needed Northrup killed, either with his automatic or with stones. The meat had but to be tossed over the limb of sage or mesquite for the sun to "jerk" it for him.

But times came when his stomach was empty and he went long without food; when there were no last, precious drops in his canteen and he began to fear that at last his map was lying to him. But always he forged on; never did the thought of turning back come to him. He knew that Strang had gone ahead, Strang for whom he had felt a mild sort of contempt.

He passed successively the points he had marked "Cave Rocks," where he spent two days and a half in interested exploration of the broken remnants of a civilization which must have been many centuries old before the Spaniards came into the New World; Big Skeleton, where, as the Hopi had foretold, he came upon the sun- bleached bones of what must at one time been a veritable giant of a man, now a pile of bones no longer of interest to preying animals where it lay upon the top of an overhanging boulder; Poison Springs where there were more skeletons, these of thirst- tormented, unwary animals; the Sunken Meadows which might have been originally the home of all the world's butterflies, and where many remained, great-winged, incredibly swift, that they might live at all through the eternal warfare which the bird-folk here waged upon them, where humming-birds brightened the air and mocking-birds shook out their cool, clear notes against desert sun and silence; into the ancient realm of cliff-dwellers where he saw countless orifices punctured into the cliffs a hundred, five hundred feet above some spring where he camped.

As the weeks wore on and he entered more deeply into the heart of the unknown, Northrup became possessed of a faith in the undertaking which had not been with him at the outset. Then he had thought, "I'll go and see." Now he felt, "I'll go and find!"

The very fact that every day he had constant proof of the Hopi's truthfulness began to work its spell upon him. Why should the end of the tale then prove fiction? Was he hourly drawing nearer the desert treasure-house?

ACROSS bare, blistering miles he followed his trail that led

him to those deathless springs which in old times had made these

arid lands an open thoroughfare to moccasined feet. There were

times in those long, silent days of utter solitude when, far to

right or left, he fancied he saw along high cliffs the remains of

an old civilization, man-made trails in the rock, rudely circular

holes in the precipices which well may have led into cool,

chambered dwellings. But it was risking too much to seek to

investigate here where distances are deceptive and water is not

assured. Nor did he have the inclination to linger. His quest had

gotten into his blood.

The time came at last when, standing clear and distinct in the north, he saw the line of cliffs marking his journey's end. He traveled now at night, since the moon was at the full. Through the loose sand which seemed one instant to give away as freely as water only to grasp at his ankles and hold him back the next, he plowed on all that night, his face set toward the north star. In the moonlight the desert about him was touched into a softness of beauty which was no attribute of it in the harsh light of day; the distant mountains looked unreal, mystically lovely, the borders of fairyland.

"What sort of people were the men and women who lived this, knew no life but this?" was Northrup's thought over and over. "The warriors, were they as hard as the desert by day? The maidens, were they as savage as their lovers? Or did the softness of desert moonlight, the tenderness of desert colorings seep into their souls?"

Toward dawn, from a gently sloping loma, he saw the clump of trees, mesquite for the most part, betokening the spot where he was to water and rest. From here, when the coolness of another dusk came, he would press on—over the last lap of the quest.

That day he dozed restlessly, dreaming broken dreams from which he started up repeatedly, muttering. The scenes through which he had so long traveled had had their deeper impressions upon him and suggested wild thoughts which in sleep were unchecked. The speculation of what might lay ahead mingled with them.

He felt all night as if he were in the grip of some power other than his own, not to be explained by materialistic mankind. He dreamed that the old peoples who had striven with the desert for existence, who had mastered it and lived through it, were not dead; that they still had their mountain fastnesses; that he moved among them; that strange adventures were his.

Toward late afternoon, too restlessly eager for further rest, he ate, drank, filled his canteens and struck out for the mountains. And before he had gone a mile, before the sun had wheeled down toward the end of the hottest day he had yet experienced, a thing occurred which sent a thrill through the man's physical being, a fresh shock of wonderment into his heart.

Before him were the heat waves trembling over a wide expanse of barren sand. Sand for miles in each direction, the white, loose sand which one finds in wind-tumbled dunes, like the white sand of the seashore, but waterless. Then slowly into the emptiness of burning air there grew a vision. He looked upon it at first with little interest; this sort of thing could hardly interest him after all these years of life upon the fringe of the desert, he thought. But, ten steps further he grew stock still, his heart thumping wildly, the old sense of the supernatural strong upon him.

He saw, woven into the semblance of reality from sunlight and air, hanging in the air close to the ground, like some master's painting suspended by invisible ropes, a scene of rare beauty, of mad beauty, for this bleak stretch of scant vegetation. It was a garden a hundred feet across, with tall, lush, water-loving flowers such as he had never seen before.

In the heart of the garden a pool of water with shade-trees dropping leaves into it, a pool not of nature's making but of man's. For surely its basin was white rock which man's hand had carved and scooped out; surely there stood carven pillars and columns of white stone about it. The water shone at him with a blue laughter, the white of the rock glistened like snow; the grass and plants flung emerald reflections at themselves; the blossoms everywhere were purple and scarlet and deep rose.

Clearer and clearer grew the desert vision until Northrup, seeing a bright-colored parrot drop from a swaying branch like a floating flower, caught his breath in wonderment.

"My God!" cried Northrup sharply. "Have I gone mad?"

He knew the way in which the thirst-torment ends: in forgetfulness of what one has suffered, in delicious delirium, in fancies like this thing which his two eyes told him was physical fabric.

His eyes had followed the gaudy flight of the parrot. And so they came to see what he had not seen before, to trick him into thinking he saw what he would not believe existed.

A hand had been thrown out—never mirage like this if this in sober truth were not magic's masterpiece—a slow- moving, graceful hand, a bare arm of rare perfection. The parrot had perched upon a finger, seeming to cock a suspicious, jealous head toward Northrup. So Northrup had seen the hand, the arm, the maiden herself.

She was lying upon her side, an arm flung out, an arm under her head. He saw the loose hair about her face, saw—or fancied he saw, for his senses were reeling—the face itself, the lips curving to languid laughter, saw the white robe girt about with a broad band of blue, saw the crimson flower set close to the brown throat, saw the little bare feet from which the white moccasins had fallen. And then—

Then the air had wavered and shimmered and clouded and cleared, and Sax Northrup found himself staring out across an empty stretch of white sand, drifted here and there by the desert winds.

TONIGHT the wind rose with sunset, sweeping across the desert in strong gusts. The white drifts of sand were disposed anew, in fresh designs. The sand, carried in level strata, cut at Northrup's face and hands, stinging him unmercifully like fine particles of heated glass.

Within an hour the wind dropped. The sparse grass here and there was motionless. It was stifling hot for another hour. Then came sudden cold through which Northrup made swifter progress. At dawn he thought that the mountains were not ten miles away, that he could come to them long before noon.

But as the sun rose, the wind came up with it, blowing again in mighty gusts, then settling into a steady storm from the north. Every step of the way now Northrup fought hard. The wind whipped the moisture out of his body until his skin seemed to be on fire. Bend his head as he might, the sand found its way under his hat-brim, cutting his face, driving through his shirt-collar, slipping everywhere into his clothing, running into his boots. An hour after sun-up it was fearfully hot; the sun was a small ball looking very far away yet smoldering with an intense red heat.

He hoarded his water, but again and again his dry throat drove him to lift his canteen to his lips. He sought to see the mountains ahead of him and could not make out the dimmest outline.

The flying sand would have hidden them had they been less than a tenth of the ten miles distant. It had smothered the world; it was choking, stifling him. He tied a handkerchief about his face and threw himself to the ground. He could make no progress against that fierce, raging storm from the north. He knew the folly of matching his strength against it. At this rate he would have exhausted his force, drunk his water in an hour, and then the piling, drifting, flying sand would work its grim way with him.

He began to think the storm would never end. The darkness into which mid-day was plunged grew thicker; the sun was a terrible, unearthly thing, dim and red. Until far in the afternoon the sand-storm swept upon him, racing away into the south with a sound of distant booming, with the whistle of dry sand upon dry wind. Little by little it subsided, the air thinned, a vague blur looking at the end of the world marked the mountains.

Northrup lifted his canteen. He had only a little water, perhaps two cupfuls, left. He drank sparingly and, fearful lest the wind might rise again, blowing for many days as he knew it did at times, he forced his heavy way northward.

He moved like a ghost through a mist of sand all that day. The wind came and went in gusts, dying down utterly toward sunset. The air cleared then, the mountains rose steeper, came marching to meet him. He drank the last drop of water and pushed on.

Moonrise found him, beaten and grimy, at the mouth of the great canon toward which he had journeyed. He hurried on into the cañon. There were black shadows everywhere about him. But slowly as he went on the shadows drew into themselves as the moon climbed higher.

Here, on each side of him, were the walls of the cañon, lifted up in sheer cliffs. Already the cliffs were a hundred feet high; ahead he could see that they stood up into the sky seven hundred, a thousand feet.

The cañon where he stood was perhaps fifty yards in width; a little further on it widened out to three times fifty yards, narrowing again rapidly.

But now Northrup's eyes were concerned not with the walls of rock but with the floor of the cañon. He wanted water, wanted it badly. All day he had been stinted for it; now he must have it, and soon. His throat ached and burned; his tongue felt thick and stiff in his mouth; his whole body cried to him for water.

He believed that he had come to the right cañon; it was as the Hopi had described it, lying due north of the last water- hole, with the tallest peak towering above it. If in the sand- storm he had lost his bearings, why then so much the worse for a foolhardy adventurer.

FOR an hour he sought water and found none. His thirst was

tormenting him, driving him mad.

The moonlight glistening from a white slab of granite tricked him; he hurried stumbling to it only to twist his lips into a silent curse when he saw clearly.

He sucked at his canteen and in sudden wrath threw it from him. A moment of terror came upon him in which he ran here and there blindly. He jerked himself together with anger at himself.

He went to the flat-topped boulder and sat down. He needed rest almost as badly as he needed water. And he must get himself in hand.

The orb of the moon silvered the cliffs above him. Northrup sent his eyes questing everywhere, even up the cliffs. He saw something move, a wolf he supposed. He wasn't interested in wolves; it was water he wanted.

But his eyes remained a moment with the sign of life, hundreds of feet above him. The moving thing came out from a blotch of shadow and stood upon the edge of the cliff. It was not a wolf, it was a man, or else the trickery of the moon was building another taunting vision for him.

The moving form, coming to the very edge, stood still. Northrup saw the man distinctly, almost straight up above him. The face was in profile, etched clear against the sky. It was the face of an Indian, Hopi perhaps, but handsomer than the Hopi Northrup had known, the nose prominent, the features sharply cut and clear. The Indian was naked save for the white loincloth and the band about his head. His arms were flung out toward the moon as if in supplication, his body rigid a moment, his head lifted.

Northrup sought to call out, and a dry whisper in his tortured throat fell hissingly upon his own ears. He sprang up, striving again to call. But the form above him was gone. The man had drawn back from the cliff-edge; the moonlight silvered the rock where he had been.

Hastily Northrup sought the way up there, knowing that he must come upon this man before he was beyond call. He might have used his gun to attract attention—he thought of that now—but already his feet had found the first of the rude steps in the cliff and he was climbing rapidly. When he came to the top, then if the man were not to be seen he would use the gun.

As Northrup's head rose slowly above the edge of the cliff he stopped suddenly, a little gasp in his throat. Here was a great shelf against the precipice, the cliffs falling abruptly to the desert below, rising sheer another five hundred feet back of the level space. The space, itself some hundred feet in length and half of that in width, appeared to him like some mighty stage set for one of the desert's wild extravaganzas.

He saw not one man but fifty, a hundred; he could not estimate how many. All were like the first, gaunt-bodied, clothed in the loin-cloth of pure white, their bodies glistening in the moonlight like polished bronze. They were moving about in a slow, stately procession, their arms lifted to the moon, their faces upturned, their forms swaying rhythmically as they circled about a form standing above them upon a flat boulder. Along the cliff wall upon the far side of the level space Northrup saw other forms, these in the shadow, clothed in white robes, whether of native cotton or buckskin he could not tell, the forms of matrons and maidens, scores of them.

Not a sound had come to him. The feet moving in the wide circle were bare feet falling lightly upon a floor of rock. He saw lips opened, moving in unison as if some mighty chant were bursting from them. And yet no sound of singing came to him. It was as still here as it was out ten miles across the sands.

The form standing upon the boulder about which the others circled, was that of an old man. Northrup saw the hooked beak of a nose like a hawk's, the hair falling about the shoulders, silver under the moon, the black eyes filled with a strange ecstasy. And then the black eyes saw him.

Just Northrup's head coming up slowly from the void below, a great head of yellow, disheveled hair, a great yellow beard, unkempt and made over into gold by the night light, great blue eyes looking fierce as a wolf's from the thirst upon him.

And yet the ceremonial dance, if such it were, went on with no pause. The old man stood still, his arms outflung, his lips moving as the lips of the others moved. He had seen Northrup, he had seemed then to have forgotten him.

Northrup came slowly up to the ledge, his big body seeming unnaturally large when at last he stood upon a level with the others.

"Water!" he cried hoarsely. "I want water."

He had spoken in English. His voice cut rudely into the silence. Those who had not seen him before saw him now. A hundred looks turned upon him, swift and startled. For a moment the swaying bodies and moving lips grew as still as the rocks. Then again the bodies swayed, the lips moved, the silent circle continued as if he had not broken into it.

"Water!" cried Northrup again, moving toward them heavily like some great tawny-maned lion, wrath in his eyes. And in half a dozen tongues, dialects of the southwest he hurled the word at them:

"Water. I want water!"

A fierce anger surged into Northrup's heart. Would these copper-bodied devils of silence keep on with their mad dance while Sax Northrup was dying of thirst?

He bore down upon them, the voice in his throat harsh and savage. They gave back before him, moving but a little to the side, their bodies still swaying, their lips still moving. But he saw that the scores of eyes were turned upon him wonderingly.

So he came almost to the boulder upon which the old man stood. He saw that this one was clad differently from the others, a long robe hanging from his shoulders, girted about by a broad band of red, a chain of glass beads—or were they turquoises?—about the forehead, holding the hair back. He had come almost to this man, thinking him to be the one in authority here, when he found another of the bronze bodies in his path.

Northrup plunged toward him, but this man did not move aside. He was taller than the others, Northrup noted, gaunt-bodied like them, but with mighty sinews standing out upon shoulders and arms and thighs, a man as tall as Northrup. Northrup threw out his arm to thrust this man aside, his one thought to come to the old man. But his arm struck a body hard like rock, unyielding.

"—— you!" shouted Northrup. "Stand aside. I want water!"

The man's body was swaying gently with the other swaying bodies, his lips moving with the other moving lips, his eyes fearless and stubborn and filled with threat. Northrup's two hands shot out, gripping the bare shoulders.

Until now he had seen no sign of a weapon among these people. But suddenly a knife had leaped out in this man's right hand, the moonlight running down the thin, keen blade. And still no sound save Northrup's heavy breathing and scuffling feet and angry, snarling voice. Northrup's rage was like the rage of a mad desert animal. As the knife-blade swept upward, preparatory for the downward blow, Northrup struck. His big fist hammered straight into the Indian's face, the knife clattered to the rocks, the Indian staggering back.

In an instant Northrup was upon him, had caught the lean body in his hungering hands, had dragged it to the cliff's edge, had lifted it high in air until the bronzed limbs stood out against the sky.

Then, his savage blood-lust gone as swiftly as it had come, he had cast the man down upon the ledge at his feet, turning swiftly toward the other forms which had ceased swaying at last. And as he turned he heard a burst of laughter, the soft, tinkling laughter of a woman. Out of silence he had drawn this thing, a woman's laugh bubbling over with mirth like the overflow of a sparkling fountain. And then he saw her.

Beyond the stone where the old man stood was a narrow rift in the wall of rock. Deep in the rift was a blazing fire, throwing into relief the form which had come out from it. The form of a girl, her left arm and shoulder bare and brown, a single stone or bead gleaming upon her forehead, her slender form clad in a long, loose robe of white, her feet encased in moccasins of white buckskin.

And her eyes under her dusky hair laughed, her red lips laughed. And as if an echo of her laughter came the laughter of the gaudy-plumaged parrot perched upon her round wrist.

Northrup stared at her in amazement, thinking himself staring at some soft maiden of the Orient. He forgot the others, forgot the man at his feet who had rolled over, his dark hand going swiftly to the knife upon the rock. He thought of it in time because of what he saw in the girl's eyes.

No sound after the laughter had died away, no single word. But in her eyes was a language which was not to be misunderstood. There was anger there now, a wrath which blazed as brightly as Northrup's had. And there was a command. Her eyes, passing beyond Northrup, were upon the man with the knife.

She lifted her hand as if putting a cup of water to her lips. Then she nodded briefly at the man who stood so close to Northrup with the knife shaking in his hand. Northrup, turning, saw again the picture of anger there, but an anger sullen and hesitant.

He again looked to the girl. Her hand, pointing at this man, made again the swift gesture of lifted cup, then swept in a wide arc, pointing into the rift in the rock walls through which the fire gleamed.

Northrup found himself watching as he might have done were this in reality some extravaganza and he in his seat in the audience. He read the command in the girl's furious eyes, the hesitation and sullen rage in the man's, the wonder in other eyes, and something that looked like fear, a look of baffled fury in the eyes of the old man in the long robe. And then he was following the man with the knife, passing through a long lane of silent, watchful figures, going after his guide through the narrow passageway into the cliffs.

For an instant, as he was passing close to where the girl stood at the mouth of the cleft, Northrup paused, his eyes turned curiously upon her. Her eyes met his steadily, eyes whose color was elusive there in the moonlight. He could only tell that they were big, dark and lustrous.

A word of thanks upon his lips was checked by what he read in her quick expression. The girl's gaze had swept him from the top of his tousled yellow hair to the sole of his dusty boots. Her look, meeting his again, was filled with admiration; her thought stood out plainly, with no attempt at concealment. It was as if she had opened her red mouth and said softly, wonderingly:

"You are the biggest man, the most wonderful, the most handsome I have ever looked upon!"

Northrup's face reddened suddenly and he went on, merely bowing deeply as he passed. He saw the face of the man with the knife; this man too had read the girl's expression and his features were twisted with malicious rage.

NORTHRUP, forcing himself to drink slowly, looked about him between sips of the cold water. He had followed his guide through the narrow cleft, by the fagot fire, up a series of winding, uneven steps in the rock and out upon a second ledge, some distance to the side of the first and some fifty feet higher.

Here, in a niche in the rock, was a clay water-jug, brimming. Above rose the cliffs precipitately upon one side; upon the other they fell straight down to the more gentle slope of the foothills. There was no sign of habitation here, nothing to bespeak human occupation of these heights save the waterjug and the Indian who had brought him here.

Turning, Northrup looked back down the rude stairs and through the cut in the rocks. Upon the lower ledge the old man was standing upon the boulder, his arms lifted, his face upturned, his lips moving. About him the bronze figures, naked save for the loin-cloths, were passing noiselessly, bodies swaying rhythmically.

The girl with the parrot upon her wrist, a slender, peeled willow-rod tipped with feathers in her hand, was watching them. Her lips moved with the others, her lithe body swayed with theirs, the feather-tipped rod in her hand beat time to the voiceless singing.

The man at Northrup's side had slipped silently away, his bare feet falling noiselessly upon the rock staircase. Swiftly he went down, dropping from sight, reappearing by the fire, passing out upon the lower ledge to take once more his place in the circling about the old man.

Was the desert in all truth a place bewitched? And were these voiceless beings the band of sorcerers brewing black magic to cast out through the moonlight and over the world? What strange race of tongueless people was this upon which he had stumbled, following the wild tale of a dying Indian down in Santa Fe? And—suddenly the question which had not presented itself for many days came back to him now—who was Tiyo?

Northrup shrugged his shoulders in answer to his own questioning and again lifted the water-jug to his lips, drinking more deeply now. Time would answer him and in the meantime he was not going to die of hunger and thirst. He sat down upon the verge of the higher ledge, filled his pipe and, resting, watched what went on below.

For the greater part of an hour the silent circling continued. Then, at no signal which he could see, it ceased suddenly, breaking off with abrupt finality.

The girl with the parrot, walking slowly between the two long lines of bronze figures which had drawn up and grown motionless for her passing, went to the boulder where the old man in the white robe stood. As he reached down she put her hand up, taking one of his. She carried it to her lips, the action filled with reverence. The old man stood above her like one great in power, undisputed in authority, accepting homage and reverence as his due; the girl's attitude was one of rare humbleness and humility.

But in an instant the parts had changed. As she had dropped the withered hand, the old man had slipped down from his place of eminence. In a moment he had sunk to his knees, had lifted the blue embroidered fringe of her robe, had carried it to his lips. And the girl's air had suddenly undergone a change lightning swift. Her head was lifted, the round throat showing brown and bare through the opening in her robe; she had gathered her small height so that she looked tall; her manner was subtly arrogant, queenly proud. As the kneeling figure looked up at her the reverence was in his eyes, the power and dignity in hers.

"It's the land of mad folks!" grunted Northrup.

A man knowing as much as Northrup of the Indians of the Southwest, such as dwell in Oraibi, Walpi, ancient Taos, throughout the desert lands of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, knows with what tenacity they cling to traditions which were old centuries before the armored Spaniard came into the New World. He knew them for a deeply religious people, their beliefs stoutly maintained in the face of alien interference, filled with ceremony and symbolism. He knew that this thing which he was watching was some rite deeply important to these people, and could only watch, wondering vaguely what it portended.

Among savage people there is perhaps even less difficulty in selecting at a glance the "higher-ups" than among a people who have gone further with civilization. Already Northrup recognized the very obvious fact that the persons to be reckoned with here were the old man in the white robe, a priest, without doubt, the young man with the knife, and the girl. And now, awakening a keener interest in him, came the knowledge that, for the moment at least, it was the girl to whom all eyes were turned with reverence and obedience.

She lifted the rod in her hand, a baho, or prayer- stick, no doubt, and once more the silent circle was described, the old man leading, the young fellow with the wonderful physique following, the others taking their places behind him. And all of them, passing under the outstretched baho, stooped swiftly to lift the hem of her garment to their lips. She looked over their bent heads with bright eyes, like a young queen just come into her birthright.

In a little they had all passed by her and in silent procession had come through the defile in the rocks, mounting the crooked steps, passing by Northrup with sharp, black eyes turned upon him, across the second ledge and down at the far side, seeming to him to drop one by one into the void below.

After them came the women, matrons first, with their hair arranged in Hopi fashion, done low at each side, the maidens with their hair massed into two great whorls, one at each ear, flashing quick glances of curiosity at him. Upon the lower ledge now were five figures only, the girl with the parrot and the two maidens who stood a little back of her, one on each side, the old man and the man with whom Northrup had struggled.

Now the girl was making swift gestures which for a little perplexed the man who watched her from above, though her companions seemed readily enough to grasp her meaning. Across the few feet which separated them, Northrup could catch their expressions as clearly as if it had been the sun instead of the round moon hanging above them. Into the eyes of the old man and the two attendant maidens came a quick look of horror; into the eyes of the other man a look of black anger.

The girl, seeing what Northrup saw, lifted her head a little higher, her eyes grown brighter, suddenly hard as rock. The gesture again and Northrup knew that it had something to do with him. For the feather-tipped willow-rod was pointed toward him, then out across the ledge where the others had gone, then to the young man before her.

The old man seemed upon the verge of speaking. But, still with locked lips, he shook his head vigorously. The girl whirled upon him, her attitude filled with sovereign menace, and he drew back swiftly as if afraid of her. The two maidens, eyes wide, lips parted breathlessly, stared in sheer amazement at her.

Again the girl with the parrot had whirled about, her back upon the old man, something of contempt in the action, her eyes blazing at the younger man. The gesture came swift and imperious. The fellow who had already felt Northrup's fist, and whose lips were swollen because he had, grew sullen, shaking his head with determined refusal.

The girl took a swift step toward him; he held his ground obstinately. Suddenly, her face showing the fury upon her, she had lifted the prayer-stick as if she would strike him with it. The thing was a slender rod which a man might break between thumb and forefinger. And yet it was the sacred baho!

Northrup thought that he heard a gasp; he knew that what looked like shaking fear had descended from the rod still held aloft. The old man and the young had stooped, lifting the hem of her garment, and the girl, her lips curved into a victor's smile, turned her back upon all of them and came through the defile, to the higher ledge and to Northrup's side. She flashed him a smile which, filled with triumph, was not without the warmth of the admiration which had been in her eyes when he had passed her. Then she went across the ledge, pausing at the brink to look back.

The old man and the two maidens had followed her. The other man, his face convulsed, his eyes like knives, came to where Northrup was now standing. For a moment, the two men looking into each other's eyes, had a glimpse of what might lie in the future. Then again Northrup was following his guide.

The girl, seeming satisfied, went down over the edge of the cliff. Northrup, following his guide, found other steps there, winding downward and turning about a great knob of rock. And then, startled by that which he might have expected, he was looking down into the garden with the white rock basin, the white stone columns, the pool of water and the green-leafed trees he had seen in the mirage.

Here was a third broad ledge, the cliffs at the back curving outward over it, almost like a roof. Close under this overhanging precipice was a building, rudely square, built of white stone and cement with one wide door set between two pillars of stone.

There were half a dozen square openings in the wall, their use as windows obvious. Upon the flat roof were green things growing and the great blossoms looking either white or black in the fainter light there. A temple, Northrup guessed. He was to learn differently soon.

At the side of the pool the girl with the parrot had stopped. The bird, fluttering from her wrist, perched upon a limb which bent and swayed with him. The old man and the younger one, who had guided Northrup here, made again the deep obeisance and passed on, going to the far edge of this ledge and passing down other steps, out of sight. The two attendant maidens, their eyes still wide with surprise and wonder, waited a few steps from their mistress. Again a quick imperious gesture as she turned upon them. They moved back and away, going from her to the stone building, disappearing through the wide door. The girl who had remained turned slowly, her eyes upon Northrup.

For a little she stood looking at him with deep soberness, her oval face like a little child's in its unaffected interest and curiosity. Then suddenly—it seemed that she did all things with rare swiftness excepting when the mood or pose of languor was upon her—a smile touched her lips into gentle curves, her face dimpled up at him, from low in her throat came a little burst of laughter.

"Ishohi! In your big hands did Tiyo look a little bug squirming! For that, Bahana, I thank you! Askwali!"

"Tiyo?" grunted Northrup. "So the gentleman with the carving- knife is our old friend Tiyo, eh?"

The words, coming with the little start of surprise, found utterance quite naturally in English. In the same tongue he added,

"You pretty thing! I wonder if you know you are the prettiest girl I ever saw, red, black, yellow or white?"

She looked at him frankly puzzled, shaking her head slowly. Northrup laughed. Speaking in the tongue his many months with So Wuhti had perfected he said quickly:

"I was just mentioning my delight at meeting up with Tiyo. I have heard of him."

She showed her pleasure at his speaking words which she could understand by clapping her hands. But, again very sober in her regard of him, lifting her face upward until the wonder was he didn't kiss her tempting mouth then and there, she studied him a moment and then declared as though quite satisfied and convinced:

"You are beautiful, Bahana! You are like Sikangwunuptu! Your eyes are like the skies one sees from the mountain-tops. Your hair is like gold, more beautiful than gold."

She came closer, putting up her hand in that swift way of hers until her fingers gently brushed the hair at his temple.

"Yes, you are like the God of the Yellow Dawn."

Northrup whistled. And then, though he felt like a fool for it, he blushed. He felt his face getting red, as red as fire. The girl, seeing his embarrassment, laughed again, her mirth rippling out through the still night, as pure and clean a thing as the moonlight itself.

"You little devil!" muttered the man.

She lifted her brows, making again the sign that she did not understand. Then for an instant Northrup lost sight of her in a new vision which appeared abruptly. He had thought that Tiyo and the old priest had gone on down the rocks somewhere; evidently they had contented themselves by merely going down over the edge and remaining there just out of sight.

For, as if some one had pulled a string and they both were puppets answering to the jerk, their two heads appeared again, the old man's face twisted evilly into a crimson rage, Tiyo's eyes filled with horror and an anger like the priest's. Even the two maidens who had disappeared through the wide doorway were back at the entrance; it seemed to Northrup that their dark faces had grown ashy. He was positive that they had clutched at each other and that they were trembling. He turned questioning eyes back to the girl.

If before she had taken upon herself a seeming of queenliness, now she was like an angry goddess. A moment ago one could not have looked into the limpid, laughing pools which were her eyes and have imagined that they could change so. They blazed with an anger which was greater than Tiyo's and the priest's; they shone with a menace which was hard enough to inspire one with terror. Northrup saw that while the two men held their places there came quickly into their look a certain hint of uneasiness; the two maidens had fled into the dark interior of the stone building.

"Why do you linger, Inaa Wuhtaka (Father Old Man)?" she said with a tone which knew the way to be at once cool, steady and deadly. "Why, Tiyo, do you bring back into the presence of Yahoya your evil face, unbidden? Do you wish Yahoya's blessing? Or her curse perhaps?"

The baho in her hand lifted a little, a very, very little. But the gesture was significant. Both men started back as if they had been struck across the faces. Then, only anger again to be read in the priest's countenance, he began a series of frantic signs which Northrup, looking on in wonderment, was at loss to read, but which the girl seemed to grasp readily.

"Inaa," she said gently, quite as a mother might speak to a forward child, although his years must have numbered seventy at the least, while the maiden was at the first blush of womanhood. "I understand what your locked lips whisper. Your speech comes from your heart and so it is kind. But you will remember, Inaa, that though a priest you are only a man whose path goes the way soon of the Skeleton House. And you will not forget, Inaa, who is Yahoya! Go! Tiyo goes with you."

The thin old hands lifted in protest dropped hopelessly; with no word Inaa, and Tiyo with him, went over the cliffs and out of sight. Northrup, filled more than ever with curiosity, turned to the girl.

"He is like an old sheep, is Inaa," she smiled with pleasant disrespect for the cloth. "All white wool and little brain. And Tiyo—Tiyo is his son."

"And you," said Northrup, wondering at all he had seen. "You are—Yahoya, a great lady—a princess?"

Her smile was as serene as the moonbeam across the still pool as she answered him, stating quite simply as the most matter-of- fact thing in the world:

"I am Yahoya—a goddess!"

"I—I see," stammered Northrup when he could think of anything to say. "I—I might have known it. I never saw a goddess before, but—oh, yes, you're a goddess, all right!"

"Yes," said Yahoya simply, dimpling at him quite like a maiden of flesh and blood, altogether adorable. "I am Yahoya, chief goddess of the 'People of the Hidden Spring,' sister of Haruing Wuhti, daughter of Cotukvnangi, god of thunder, mother of Tokila, the Night, bride of Pookhonghoya, god of war."

Northrup bowed and remembered to take off his hat. From the corner of his eye he looked at the goddess Yahoya in stupefaction. Was she poking fun at him or did she believe all of that stuff?

The question need not go begging for an answer. Her whole being breathed the certainty that she was what she had said she was. The attitude of Inaa the priest and his evil-eyed son Tiyo backed up her belief. They were all so certain of the thing that Northrup, a little dazed, asked himself:

"Well, why not? Everything happens here! Why not find oneself in the presence of deity?"

And he admitted that she looked the part—all except being the mother of Tokila, the Night, or of anything else.

"It is the Festival of Silence," the goddess was explaining to him in the same quiet way. "At such time it is death to make so much as a little sound with the lips, death to a mortal. But I, being an immortal, may do as I please. You, being bidden by me, may speak. Inaa," and she laughed again, mirthfully as at a rare thought, "Inaa is afraid of the Skeleton Old Man. But most of all is he afraid of me!"

"Yes," said Northrup, gathering his wits. "Exactly."