RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

"Desert Valley," Grosset & Dunlap, New York, 1921

"Desert Valley," Hodder & Stoughton Ltd., London, 1921

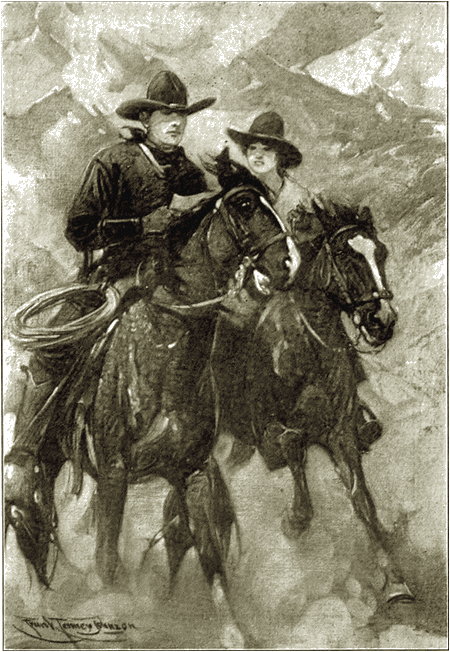

Frontispiece

"I want to show you a letter I got when I came in last night."

OVER many wide regions of the south-western desert country of Arizona and New Mexico lies an eternal spell of silence and mystery. Across the sand-ridges come many foreign things, both animate and inanimate, which are engulfed in its immensity, which frequently disappear for all time from the sight of men, blotted out like a bird which flies free from a lighted room into the outside darkness. As though in compensation for that which it has taken, the desert from time to time allows new marvels, riven from its vitals, to emerge.

Though death-still, it has a voice which calls ceaselessly to those human hearts tuned to its messages: hostile and harsh, it draws and urges; repellent, it profligately awards health and wealth; inviting, it kills. And always it keeps its own counsel; it is without peer in its lonesomeness, and without confidants; it heaps its sand over its secrets to hide them from its flashing stars.

You see the bobbing ears of a pack-animal and the dusty hat and stoop shoulders of a man. They are symbols of mystery. They rise briefly against the skyline, they are gone into the grey distance. Something beckons or something drives. They are lost to human sight, perhaps to human memory, like a couple of chips drifting out into the ocean. Patient time may witness their return; it is still likely that soon another incarnation will have closed for man and beast, that they will have left to mark their passing a few glisteningly white bones, polished untiringly by tiny sand-chisels in the grip of the desert winds. They may find gold, but they may not come in time to water. The desert is equally conversant with the actions of men mad with gold and mad with thirst.

To push out along into this immensity is to evince the heart of a brave man or the brain of a fool. The endeavour to traverse the forbidden garden of silence implies on the part of the agent an adventurous nature. Hence it would seem no great task to catalogue those human beings who set their backs to the gentler world and press forward into the naked embrace of this merciless land. Yet as many sorts and conditions come here each year as are to be found outside.

Silence, ruthlessness, mystery—these are the attributes of the desert. True, it has its softer phases—veiled dawns and dusks, rainbow hues, moon and stars. But these are but tender blossoms from a spiked, poisonous stalk, like the flowers of the cactus. They are brief and evanescent; the iron parent is everlasting.

IN the dusk a pack-horse crested a low-lying sand-ridge, put up its head and sniffed, pushed forward eagerly, its nostrils twitching as it turned a little more toward the north, going straight toward the water-hole. The pack was slipping as far to one side as it had listed to the other half an hour ago; in the restraining rope there were a dozen intricate knots where one would have amply sufficed. The horse broke into a trot, blazing its own trail through the mesquite; a parcel slipped; the slack rope grew slacker because of the subsequent readjustment; half a dozen bundles dropped after the first. A voice, thin and irritable, shouted 'Whoa!' and the man in turn was briefly outlined against the pale sky as he scrambled up the ridge. He was a little man and plainly weary; he walked as though his boots hurt him; he carried a wide, new hat in one hand; the skin was peeling from his blistered face. From his other hand trailed a big handkerchief. He was perhaps fifty or sixty. He called 'Whoa!' again, and made what haste he could after his horse.

A moment later a second horse appeared against the sky, following the man, topping the ridge, passing on. In silhouette it appeared no normal animal but some weird monstrosity, a misshapen body covered everywhere with odd wart-like excrescences. Close by, these unique growths resolved themselves into at least a score of canteens and water-bottles of many shapes and sizes, strung together with bits of rope. Undoubtedly the hand which had tied the other knots had constructed these. This horse in turn sniffed and went forward with a quickened pace.

Finally came the fourth figure of the procession. This was a girl. Like the man, she was booted; like him, she carried a broad hat in her hand. Here the similarity ended. She wore an outdoor costume, a little thing appropriate enough for her environment. And yet it was peculiarly appropriate to femininity. It disclosed the pleasing lines of a pretty figure. Her fatigue seemed less than the man's. Her youth was pronounced, assertive. She alone of the four paused more than an instant upon the slight eminence; she put back her head and looked up at the few stars that were shining; she listened to the hushed voice of the desert. She drew a scarf away from her neck and let the cooling air breathe upon her throat. The throat was round; no doubt it was soft and white, and, like her whole small self, seductively feminine.

Having communed with the night, the girl withdrew her gaze from the sky and hearkened to her companion. His voice, now remarkably eager and young for a man of his years, came to her clearly through the clumps of bushes.

'It is amazing, my dear! Positively. You never heard of such a thing. The horse, the tall, slender one, ran away, from me. I hastened in pursuit, calling to him to wait for me. It appeared that he had become suddenly refractory: they do that sometimes. I was going to reprimand him; I thought that it might be necessary to chastise him, as sometimes a man must do to retain the mastery. But I stayed my hand. The animal had not run away at all! He actually knew what he was doing. He came straight here. And what do you think he discovered? What do you imagine brought him? You would never guess.'

'Water?' suggested the girl, coming on.

Something of the man's excitement had gone from his voice when he answered. He was like a child who has propounded a riddle that has been too readily guessed.

'How did you know?'

'I didn't know. But the horses must be thirsty. Of course they would go straight to water. Animals can smell it, can't they?'

'Can they?' He looked to her inquiringly when she stood at his side. 'It is amazing, nevertheless. Positively, my dear,' he added with a touch of dignity.

The two horses, side by side, were drinking noisily from a small depression into which the water oozed slowly. The girl watched them a moment abstractedly, sighed and sat down in the sand, her hands in her lap.

'Tired, Helen?' asked the man solicitously.

'Aren't you?' she returned. 'It has been a hard day, papa.'

'I am afraid it has been hard on you, my dear,' he admitted, as his eyes took stock of the drooping figure. 'But,' he added more cheerfully, 'we are getting somewhere, my girl; we are getting somewhere.'

'Are we?' she murmured to herself rather than for his ears. And when he demanded 'Eh?' she said hastily: 'Anyway, we are doing something. That is more fun than growing moss, even if we never succeed.'

'I tell you,' he declared forensically, lifting his hand for a gesture, 'I know! Haven't I demonstrated the infallibility of my line of action? If a man wants to—to gather cherries, let him go to a cherry tree; if he seeks pearls, let him find out the favourite habitat of the pearl oyster; if he desires a—a hat, let him go to the hatter's. It is the simplest thing in the world, though fools have woven mystery and difficulty about it. Now——'

'Yes, pops.' Helen sighed again and saw wisdom in rising to her feet. 'If you will begin unpacking I'll make our beds. And I'll get the fire started.'

'We can dispense with the fire,' he told her, setting to work with the first knot to come under his fingers. 'There is coffee in the thermos bottle and we can open a tin of potted chicken.'

'The fire makes it cosier,' Helen said, beginning to gather twigs. Last night coyotes had howled fearsomely, and even dwellers of the cities know that the surest safeguard against a ravening beast is a camp-fire. For a little while the man strove with his tangled rope; she was lost to him through the mesquite. Suddenly she came running back.

'Papa,' she whispered excitedly. 'There's some one already here.'

She led him a few paces and pointed, making him stoop to see. Under the tangle of a thin brush patch he made out what she had seen. But a short distance from the spot they had elected for their camp site was a tiny fire blazing merrily.

'Ahem,' said Helen's father, shifting nervously and looking at his daughter as though for an explanation of this oddity. 'This is peculiar. It has an air of—of——'

'Why, it is the most natural thing in the world,' she said swiftly. 'Where would you expect to find a camp-fire if not near a spring?'

'Yes, yes, that part of it is all right,' he admitted grudgingly. 'But why does he hold back and thereby give one an impression of a desire on his part for secrecy? Why does he not come forward and make himself known? I do not mean to alarm you, my dear, but this is not the way an honest fellow-wayfarer should behave. Wait here for me; I shall investigate.' Intrepidly he walked toward the fire. Helen kept close to his side.

'Hello!' he called, when they had taken a dozen steps. They paused and listened. There was no reply, and Helen's fingers tightened on his arm. Again he looked to her as though once more he asked the explanation of her; the look hinted that upon occasion the father leaned on the daughter more than she on him. He called again. His voice died away echoless, the silence seeming heavier than before. When one of the horses behind them, turning from the water, trod upon a dry twig, both man and girl started. Then Helen laughed and went forward again.

Since the fire had not lighted itself, it merely bespoke the presence of a man. Men had no terror to her. In the ripe fullness of her something less than twenty years she had encountered many of them. While with due modesty she admitted that there was much in the world that she did not know, she considered that she 'knew' men.

The two pressed on together. Before they had gone far they were greeted by the familiar and vaguely comforting odours of boiling coffee and frying bacon. Still they saw no one. They pushed through the last clump of bushes and stood by the fire. On the coals was the black coffee-pot. Cunningly placed upon two stones over a bed of coals was the frying-pan. Helen stooped instinctively and lifted it aside; the half-dozen slices of bacon were burned black.

'Hello!' shouted the man a third time, for nothing in the world was more clear than that whoever had made the fire and begun his supper preparations must be within call. But no answer came. Meantime the night had deepened; there was no moon; the taller shrubs, aspiring to tree proportions, made a tangle of shadow.

'He has probably gone off to picket his horse,' said Helen's father. 'Nothing could be more natural.'

Helen, more matter-of-fact and less given to theorizing, looked about her curiously. She found a tin cup; there was no bed, no pack, no other sign to tell who their neighbour might be. Close by the spot where she had set down the frying-pan she noted a second spring. Through an open space in the stunted desert growth the trail came in from the north. Glancing northward she saw for the first time the outline of a low hill. She stepped quickly to her father's side and once more laid her hand on his arm.

'What is it?' he asked, his voice sharpening at her sudden grip.

'It's—it's spooky out here,' she said.

He scoffed. 'That's a silly word. In a natural world there is no place for the supernatural.' He grew testy. 'Can I ever teach you, Helen, not to employ words utterly meaningless?'

But Helen was not to be shaken.

'Just the same, it is spooky. I can feel it. Look there.' She pointed. 'There is a hill. There will be a little ring of hills. In the centre of the basin they make would be the pool. And you know what we heard about it before we left San Juan. This whole country is strange, somehow.'

'Strange?' he queried challengingly. 'What do you mean?'

She had not relaxed her hand on his arm. Instead, her fingers tightened as she suddenly put her face forward and whispered defiantly:

'I mean spooky!'

'Helen,' he expostulated, 'where did you get such ideas?'

'You heard the old Indian legends,' she insisted, not more than half frightened but conscious of an eerie influence of the still loneliness and experiencing the first shiver of excitement as she stirred her own fancy. 'Who knows but there is some foundation for them?'

He snorted his disdain and scholarly contempt.

'Then,' said Helen, resorting to argument, 'where did that fire come from? Who made it? Why has he disappeared like this?'

'Even you,' said her father, quick as always to join issue where sound argument offered itself as a weapon, 'will hardly suppose that a spook eats bacon and drinks coffee,'

'The—the ghost,' said Helen, with a humorous glance in her eyes, 'might have whisked him away by the hair of the head!'

He shook her hand off and strode forward impatiently. Again and again he shouted 'Hello!' and 'Ho, there! Ho, I say!' There came no answer. The bacon was growing cold; the fire burning down. He turned a perplexed face towards Helen's eager one.

'It is odd,' he said irritably. He was not a man to relish being baffled.

Helen had picked up something which she had found near the spring, and was studying it intently. He came to her side to see what it was. The thing was a freshly-peeled willow wand, left upright where one end had been thrust down into the soft earth. The other end had been split; into the cleft was thrust a single feather from a bluebird's wing.

Helen's eyes looked unusually large and bright. She turned her head, glancing over her shoulder.

'Some one was here just a minute ago,' she cried softly. 'He was camping for the night. Something frightened him away. It might have been the noise we made. Or—what do you think, papa?'

'I never attempt to solve a problem until the necessary data are given me,' he announced academically.

'Or,' went on Helen, at whose age one does not bother about such trifles as necessary data, 'he may not have run away at all. He may be hiding in the bushes, listening to us. There are all kinds of people in the desert. Don't you remember how the sheriff came to San Juan just before we left? He was looking for a man who had killed a miner for his gold dust.'

'You must curb a proclivity for such fanciful trash.' He cleared his throat for the utterance. He put out his hand and Helen hastily slipped her own into it. Silently they returned to their own camp site, the girl carrying in her free hand the wand tipped with the bluebird feather. Several times they paused and looked back. There was nothing but the glow of the dwindling fire and the sweep of sand, covered sparsely with ragged bushes. New stars flared out; the spirit of the night descended upon the desert. As the world seemed to draw further and further away from them, these two beings, strange to the vastness engulfing them, huddled closer together. They spoke little, always in lowered voices. Between words they were listening, awaiting that which did not come.

PHYSICALLY tired as they were, the night was a restless one for both Helen and her father. They ate their meal in silence for the most part, made their beds close together, picketed their horses near by and said their listless 'good nights' early. Each heard the other turn and fidget many times before both went to sleep. Helen saw how her father, with a fine assumption of careless habit, laid a big new revolver close to his head.

The girl dozed and woke when the pallid moon shone upon her face. She lifted herself upon her elbow. The moonlight touched upon the willow stick she had thrust into the sand at her bedside; the feather was upright and like a plume. She considered it gravely; it became the starting-point of many romantic imaginings. Somehow it was a token; of just exactly what, to be sure, she could not decide. Not definitely, that is; it was always indisputable that the message of the bluebird is one of good fortune.

A less vivid imagination than Helen's would have found a tang of ghostliness in the night. The crest of the ridge over which they had come through the dusk now showed silvery white; white also were some dead branches of desert growth—they looked like bones. Always through the intense silence stirred an indistinguishable breath like a shiver. Individual bushes assumed grotesque shapes; when she looked long and intently at one she began to fancy that it moved. She scoffed at herself, knowing that she was lending aid to tricking her own senses, yet her heart beat a wee bit faster. She gave her mind to large considerations: those of infinity, as her eyes were lifted heavenward and dwelt upon the brightest star; those of life and death, and all of the mystery of mysteries. She went to sleep struggling with the ancient problem: 'Do the dead return? Are there, flowing about us, weird, supernatural influences as potent and intangible as electric currents?' In her sleep she continued her interesting investigations, but her dreaming vision explained the evening's problem by showing her the camp-fire made, the bacon and coffee set thereon, by a very nice young man with splendid eyes.

She stirred, smiled sleepily, and lay again without moving; after the fashion of one awakening she clung to the misty frontiers of a fading dream-country. She breathed deeply, inhaling the freshness of the new dawn. Then suddenly her eyes flew open, and she sat up with a little cry; a man who would have fitted well enough into any fancy-free maiden's dreams was standing close to her side, looking down at her. Helen's hands flew to her hair.

Plainly—she read that in the first flashing look—he was no less astounded than she. At the moment he made a picture to fill the eye and remain in the memory of a girl fresh from an Eastern City. The tall, rangy form was garbed in the picturesque way of the country; she took him in from the heels of the black boots with their silver spurs to the top of his head with its amazingly wide black hat. He stood against a sky rapidly filling to the warm glow of the morning. His horse, a rarely perfect creation even in the eyes of one who knew little of fine breeding in animals, stood just at its master's heels, with ears pricked forward curiously.

Helen wondered swiftly if he intended to stand there until the sun came up, just looking at her. Though it was scarcely more than a moment that he stood thus, in Helen's confusion the time seemed much longer. She began to grow ill at ease; she felt a quick spurt of irritation. No doubt she looked a perfect fright, taken all unawares like this, and equally indisputably he was forming an extremely uncomplimentary opinion of her. It required less than three seconds for Miss Helen to decide emphatically that the man was a horrible creature.

But he did not look any such thing. He was healthy and brown and boyish. He had had a shave and haircut no longer ago than yesterday and looked neat and clean. His mouth was quite as large as a man's should be and now was suddenly smiling. At the same instant his hat came off in his big brown hand and a gleam of downright joyousness shone in his eyes.

'Impudent beast!' was Helen's quick thought. She had given her mind last night a great deal less to matters of toilet than to mystic imaginings; it lay entirely in the field of absurd likelihood that there was a smear of black across her face.

'My mistake,' grinned the stranger. 'Guess I'll step out while the stepping's good and the road open. If there's one sure thing a man ought to be shot for, it's stampeding in on another fellow's honeymoon. Adios, señora.'

'Honeymoon!' gasped Helen. 'The big fool.'

Her father wakened abruptly, sat up, grasping his big revolver in both hands, and blinked about him; he, too, had had his dreams. In the night-cap which he had purchased in San Juan, his wide, grave eyes and sun-blistered face turned up inquiringly; he was worthy of a second glance as he sat prepared to defend himself and his daughter. The stranger had just set the toe of his boot into the stirrup; in this posture he remained, forgetful of his intention to mount, while his mare began to circle and he had to hop along to keep pace with her, his eyes upon the startled occupant of the bed beyond Helen's. He had had barely more than time to note the evident discrepancy in ages which naturally should have started his mind down a new channel for the explanation of the true relationship, when the revolver clutched tightly in unaccustomed fingers went off with an unexpected roar. Dust spouted up a yard beyond the feet of the man who held it. The horse plunged, the stranger went up into the saddle like a flash, and the man dropped his gun to his blanket and muttered in the natural bewilderment of the moment:

'It—it went off by itself! The most amazing——'

The rider brought his prancing horse back and fought with his facial muscles for gravity; the light in his eyes was utterly beyond his control.

'I'd better be going off by myself somewhere,' he remarked as gravely as he could manage, 'if you're going to start shooting a man up just because he calls before breakfast.'

With a face grown a sick white, the man in bed looked helplessly from the stranger to his daughter and then to the gun.

'I didn't do a thing to it,' he began haltingly.

'You won't do a thing to yourself one of these fine days.' remarked the horseman with evident relish, 'if you don't quit carrying that sort of life-saver. Come over to the ranch and I'll swap you a hand-axe for it.'

Helen sniffed audibly and distastefully. Her first impression of the stranger had been more correct than are first impressions nine times out of ten; he was as full of impudence as a city sparrow. She had sat up 'looking like a fright'; her father had made himself ridiculous; the stranger was mirthfully concerned with the amusing possibilities of both of them.

Suddenly the tall man, smitten by inspiration, slapped his thigh with one hand, while with the other he curbed rebellion in his mare and offered the explosive wager:

'I'll bet a man a dollar I've got your number, friends. You are Professor James Edward Longstreet and his little daughter Helen! Am I right?'

'You are correct, sir,' acknowledged the professor a trifle stiffly. His eye did not rise, but clung in a fascinated, faintly accusing way to the gun which had betrayed him.

The stranger nodded and then lifted his hat for the ceremony while he presented himself.

'Name of Howard,' he announced breezily. 'Alan Howard of the old Diaz Rancho. Glad to know you both.'

'It is a pleasure, I am sure, Mr. Howard,' said the professor. 'But, if you will pardon me, at this particular time of day——'

Alan Howard laughed his understanding.

'I'll chase up to the pool and give Helen a drink of real water,' he said lightly. 'Funny my mare's name should be Helen, too, isn't it?' This directly into a pair of eyes which the growing light showed to be grey and attractive, but just now hostile. 'Then, if you say the word, I'll romp back and take you up on a cup of coffee. And we'll talk things over.'

He stooped forward in the saddle a fraction of an inch; his mare caught the familiar signal and leaped; they were gone, racing away across the sand which was flung up after them like spray.

'Of all the fresh propositions!' gasped Helen.

But she knew that he would not long delay his return, and so slipped quickly from under her blanket and hurried down to the water-hole to bathe her hands and face and set herself in order. Her flying fingers found her little mirror; there wasn't any smudge on her face, after all, and her hair wasn't so terribly unbecoming that way; tousled, to be sure, but then, nice, curly hair can be tousled and still not make one a perfect hag. It was odd about his mare being named Helen. He must have thought the name pretty, for obviously he and his horse were both intimate and affectionate. 'Alan Howard.' Here, too, was rather a nice name for a man met by chance out in the desert. She paused in the act of brushing her hair. Was she to get an explanation of last night's puzzle? Was Mr. Howard the man who had lighted the other fire?

The professor's taciturnity was of a pronounced order this morning. Now and then as he made his own brief and customarily untidy toilet, he turned a look of accusation upon the big Colt lying on his bed. Before drawing on his boots he bestowed upon his toe a long glance of affection; the bullet that had passed within a very few inches of this adjunct of his anatomy had emphasized a toe's importance. He had never realized how pleasant it was to have two big toes, all one's own and unmarred. By the time the foot had been coaxed and jammed down into his new boot the professor's good humour was on the way to being restored; a man of one thought at the time, due to his long habit of concentration, his emotion was now one of a subdued rejoicing. It needed but the morning cup of coffee to set him beaming upon the world.

Alan Howard's sudden call: 'Can I come in now, folks?' from across a brief space of sand and brush, found Professor Longstreet on his knees feeding twigs to a tiny blaze, and hastened Helen through the final touches of her dressing. Helen was humming softly to herself, her back to him, her mind obviously concentrated upon the bread she was slicing, when the stranger swung down from his saddle and came forward. He stood a moment just behind her, looking at her with very evident interest in his eyes.

'How do you like our part of the world?' he asked friendliwise.

Helen ignored him briefly. Had Mr. Alan Howard been a bashful young man of the type that reddens and twists its hat in big nervous hands and looks guilty in general. Miss Helen Longstreet would have been swiftly all that was sweet and kind to him. Now, however, from some vague reason or clouded instinct, she was prepared to be as stiff as the fanged stalk of a cactus. Having ignored him the proper length of time, she replied coolly:

'Father and I are very much pleased with the desert country. But, may I ask just why you speak of it as your part of the world rather than ours? Are we trespassing, pray?' The afterthought was accompanied by an upflashing look that was little less than outright challenge.

'Trespassing? Lord, no,' conceded Howard heartily. 'The land is wide, the trail open at both ends. But you know what I meant.'

Helen shrugged and laid aside the half-loaf. Since she gave him no answer, Howard went on serenely:

'I mean a man sort of acquires a feeling of ownership in the place in which he has lived a long time. You and your father are Eastern, not Western. If I came tramping into your neck of the woods—you see I call it yours. Right enough, too, don't you think, professor?'

'In a way of speaking, yes,' answered the professor. 'In another way, no. We have given up the old haunts and the old way of living. We are rather inclined, my dear young sir, to look upon this as our country, too.'

'Bully for you!' cried Howard warmly. 'You're sure welcome.' His eyes came back from the father to rest upon the daughter's bronze tresses. 'Welcome as a water-hole in a hot land,' he added emphatically.

'Speaking of water-holes,' suggested Longstreet, sitting back upon his boot heels in a manner to suggest the favourite squatting position of the cowboys of whom he and his daughter had seen much during these last few weeks, 'was it you who made camp right over yonder?' He pointed.

Helen looked up curiously for Howard's answer and thus met the eyes he had not withdrawn from her. He smiled at her, a frank, open sort of smile, and thereafter turned to his questioner.

'When?' he asked briefly.

'Last night. Just before we came.'

'What makes you think some one made camp there?'

'There was a fire; bacon was frying, coffee boiling.'

'And you didn't step across to take a squint at your next-door neighbour?'

'We did,' said the professor. 'But he had gone, leaving his fire burning, his meal cooking.'

Howard's eyes travelled swiftly to Helen, then back to her father.

'And he didn't come back?'

'He did not,' said Longstreet. 'Otherwise I should not have asked if you were he.'

Even yet Howard gave no direct answer. Instead he turned his back and strode away to the deserted camp site. Helen watched him through the bushes and noted how he made a quick but evidently thorough examination of the spot. She saw him stoop, pick up frying-pan and cup, drop them and pass around the spring, his eyes on the ground. Abruptly he turned away and pushed through a clump of bushes, disappearing. In five minutes he returned, his face thoughtful.

'What time did you get here?' he asked. And when he had his answer he pondered it a moment before he went on: 'The gent didn't leave his card. But he broke camp in a regular blue-blazes hurry; saddled his horse over yonder and struck out the shortest way toward King Cañon. He went as if the devil himself and his one best bet in hell hounds was running at his stirrups.'

'How do you know?' queried Longstreet's insatiable curiosity. 'You didn't see him?'

'You saw the fire and the things he left stewing,' countered Howard. 'They spelled hurry, didn't they? Didn't they shout into your ears that he was on the lively scamper for some otherwhere?'

'Not necessarily,' maintained Longstreet eagerly. 'Reasoning from the scant evidence before us, a man would say that while the stranger may have left his camp to hurry on, he may on the other hand have just dodged back when he heard us coming and hidden somewhere close by.'

Again Howard pondered briefly.

'There are other signs you did not see,' he said in a moment. 'The soil where he had his horse staked out shows tracks, and they are the tracks of a horse going some from the first jump. Horse and man took the straightest trail and went ripping through a patch of mesquite that a man would generally go round. Then there's something else. Want to see?'

They went with him, the professor with alacrity, Helen with a studied pretence at indifference. By the spring where Helen had found the willow rod and the bluebird feather, Howard stopped and pointed down.

'There's a set of tracks for you,' he announced triumphantly. 'Suppose you spell 'em out, professor; what do you make of them?'

The professor studied them gravely. In the end he shook his head.

'Coyote?' he suggested.

Howard shook his head.

'No coyote,' he said with positiveness. 'That track shows a foot four times as big as any coyote's that ever scratched fleas. Wolf? Maybe. It would be a whopper of a wolf at that. Look at the size of it, man! Why, the ugly brute would be big enough to scare my prize shorthorn bull into taking out life insurance. And that isn't all. That's just the front foot. Now look at the hind foot. Smaller, longer, and leaving a lighter imprint. All belonging to the same animal.' He scratched his head in frank bewilderment. 'It's a new one on me,' he confessed frankly. Then he chuckled. 'I'd bet a man that the gent who left on the hasty foot just got one squint at this little beastie and at that had all sorts of good reasons for streaking out.'

A big lizard went rustling through a pile of dead leaves and all three of them started. Howard laughed.

'We're right near Superstition Pool!' he informed them with suddenly assumed gravity. 'Down in Poco Poco they tell some great tales about the old Indian gods going man-hunting by moonlight. Quién sabe, huh?'

Professor Longstreet snorted. Helen cast a quick, interested look at the stranger and one of near triumph upon her father.

'I smell somebody's coffee boiling,' said the cattleman abruptly. 'Am I invited in for a cup? Or shall I mosey on? Don't be bashful in saying I'm not wanted if I'm not.'

'Of course you are welcome,' said Longstreet heartily. But Howard turned to Helen and waited for her to speak.

'Of course.' said Helen carelessly.

'YOU were merely speaking by way of jest, I take it, Mr. Howard,' remarked Longstreet, after he had interestedly watched the rancher put a third and fourth heaping spoonful of sugar in his tin cup of coffee. 'I refer, you understand, to your hinting a moment ago at there being any truth in the old Indian superstitions. I am not to suppose, am I, that you actually give any credence to tales of supernatural influences manifested hereabouts?'

Alan Howard stirred his coffee meditatively, and after so leisurely a fashion that Longstreet began to fidget. The reply, when finally it came, was sufficiently non-committal.

'I said "Quién sabe?”" to the question just now,' he said, a twinkle in the regard bestowed upon the scientist. 'They are two pretty good little old words and fit in first-rate lots of times.'

'Spanish for "Who knows?" aren't they?'

Howard nodded. 'They used to be Spanish; I guess they're Mex by now.'

Longstreet frowned and returned to the issue.

'If you were merely jesting, as I supposed——'

'But was I?' demanded Howard. 'What do I know about it? I know horses and cows; that's my business. I know a thing or two about men, since that's my business at times, too; also something like half of that about half-breeds and mules; I meet up with them sometimes in the run of the day's work. You know something of what I think you call auriferous geology. But what does either of us know of the nightly custom of dead Indians and Indian gods?'

Helen wondered with her father whether there were a vein of seriousness in the man's thought. Howard squatted on his heels, from which he had removed his spurs; they were very high heels, but none the less he seemed comfortably at home rocking on them. Longstreet noted with his keen eyes, altered his own squatting position a fraction, and opened his mouth for another question. But Howard forestalled him, saying casually:

'I have known queer things to happen here, within a few hundred yards of this place. I haven't had time to go finding out the why of them; they didn't come into my day's work. I have listened to some interesting yarns; truth or lies it didn't matter to me. They say that ghosts haunt the Pool just yonder. I have never seen a ghost; there's nothing in raising ghosts for market, and I'm the busiest man I know trying to chew a chunk that I have bitten off. They tell you down at San Juan and in Poco Poco, and all the way up to Tecolote, that if you will come here a certain moonlight night of the year and will watch the water of the pool, you'll see a vision sent up by the gods of the Underworld. They'll even tell you how a nice little old god by the name of Pookhonghoya appears now and then by night, hunting souls of enemies—and running by the side of the biggest, strangest wolf that human eyes ever saw.'

Helen looked at him swiftly. He had added the last item almost as an afterthought. She imagined that he had embellished the old tale from his own recent experience, and, further, that Mr. Alan Howard was making fun of them and was no adept in the science of fabrication.

'They go further,' Howard spun out his tale. 'Somewhere in the desert country to the north there is, I believe, a tribe of Hidden People that the white man has never seen. The interesting thing about them is that they are governed by a young and altogether maddeningly pretty goddess who is white and whose name is Yahoya. When they come right down to the matter of giving names,' he added gravely, 'how is a man to go any further than just say, "Quién sabe?"'

'That is stupid.' said Longstreet irascibly. 'It's a man's chief affair in life to know. These absurd legends——'

'Don't you think, papa,' said Helen coolly, 'that instead of taxing Mr. Howard's memory and—and imagination, it would be better if you asked him about our way from here on?'

Howard chuckled. Professor Longstreet set aside his cup, cleared his throat and agreed with his daughter.

'I am prospecting,' he announced, 'for gold. We are headed for what is known as the Last Ridge country. I have a map here.'

He drew it from his pocket, neatly folded, and spread it out. It was a map such as is to be purchased for fifty cents at the store in San Juan, showing the main roads, towns, waterholes and trails. With a blue pencil he had marked out the way they planned to go. Howard bent forward and took the paper.

'We are going the same way, friend,' he said as he looked up. 'What is more, we are going over a trail I know by heart. There is a good chance I can save you time and trouble by making it a party of three. Am I wanted?'

'It is extremely kind of you,' said Longstreet appreciatively. 'But you are on horseback and we travel slowly.'

'I can spare the time,' was the even rejoinder. 'And I'll be glad to do it.'

During the half-hour required to break camp and pack the two horses, Alan Howard gave signs of an interest which now and then mounted almost to high delight. He made no remark concerning the elaborate system of water-bottles and canteens, but his eyes brightened as he aided the professor in making them fast. When the procession was ready to start he strode on ahead, leading his own horse and hiding from his new friends the widening grin upon his face.

The sun was up; already the still heat of the desert was in the air. Behind the tall rancher and his glossy mare came Professor Longstreet driving his two pack animals. Just behind him, with much grave speculation in her eyes, came Helen. A new man had swum all unexpectedly into her ken and she was busy cataloguing him. He looked the native in this environment, but for all that he was plainly a man of her own class. No illiteracy, no wild shy awkwardness marked his demeanour. He was as free and easy as the north wind; he might, after all, be likeable. Certainly it was courtois of him to set himself on foot to be one of them. The mare looked gentle despite her high life; Helen wondered if Alan Howard had thought of offering her his mount?

They had come to the first of the low-lying hills.

'Miss Longstreet,' called Howard, stopping and turning, 'wouldn't you like to swing up on Sanchia? She is dying to be ridden.'

The trail here was wide and clearly defined; hence Longstreet and his two horses went by and Helen came up with Howard. Hers was the trick of level, searching eyes. She looked steadily at him as she said evenly:

'So her name is Sanchia?'

For an instant the man did not appear to understand. Then suddenly Helen was treated to the sight of the warm red seeping up under his tan. And then he slapped his thigh and laughed; his laughter seeming unaffected and joyous.

'Talk about getting absent-minded in my old age,' he declared. 'Her name did use to be Sanchia; I changed it to Helen. Think of my sliding back to the old name.'

Helen's candid look did not shift for the moment that she paused. Then she went on by him, following her father, saying merely:

'Thank you, I'll walk. And if she were mine I'd keep the old name; Sanchia suits her exactly.'

But as she hurried on after her father she had time for reflection; plainly the easy-mannered Mr. Alan Howard had renamed his mare only this very morning; as plainly had he in the first place called her Sanchia in honour of some other friend or chance acquaintance. Helen wondered vaguely who the original Sanchia was. To her imagination the name suggested a slim, big-eyed Mexican girl. She found time to wonder further how many times Mr. Howard had named his horse.

They skirted a hill, dipped into the hollow which gave passageway between this hill and its twin neighbour, mounted briefly, and within twenty minutes came to the pool about which legends flocked. From their vantage point they looked down upon it. The sun searched it out almost at the instant that their eyes caught the glint of it. Fed by many hidden springs it was a still, smooth body of water in the bowl of the hills; it looked cool and deep and had its own air of mystery; in its ancient bosom it may have hidden bones or gold. Some devotee had planted a weeping willow here long ago; the great tree now flourished and cast its reflection across its own fallen leaves.

Helen's eyes dreamed and sought visions; the spot touched her with its romance, and she, after the true style of youth, lent aid to the still influences. Alan Howard, to whom this was scarcely other than an everyday matter, turned naturally to the new and was content to watch the girl. As for Longstreet, his regard was busied with the stones at his feet, and thereafter with a washout upon a hill-side where the formation of the hills themselves was laid bare to a scientific eye.

'There's gold everywhere about here,' he announced placidly. 'But not in the quantities I have promised you, Helen. We'll go on to the Last Ridge country before we stop.'

Howard turned from the daughter to consider the father long and searchingly, after the way of one man seeking another's measure.

'As a rule I go kind of slow when it comes to cutting in on another fellow's play,' he said bluntly. 'But I'm going to chip in now with this: I know that Last Ridge country from horn to tail, and all the gold that's in it or has ever been in it wouldn't buy a drink of bad whisky in Poco Poco.'

The light of forensic battle leaped up bright and eager in Longstreet's eyes. But Howard saw it, and before the professor's unshaken positiveness could pour itself forth in a forensic flood the rancher cut the whole matter short by saying crisply:

'I know. And it's up to you. I've shot my volley to give you the right slant and you can play out your string your own way. Right now we'd better be moseying on; the sun's climbing, partner.'

He passed by them, leading his mare toward a crease in the hills which gave ready passage out of the bowl and again to the sweep of the desert. Longstreet dropped in behind him, driving his two horses, while Helen stood a little alone by the pool, looking at it with eyes which still brooded. In her hatband was a bluebird feather; her fingers rose to it reminiscently. A faint, dying breeze just barely stirred the drooping branches of the willow; in one place the graceful pendant leaves merged with their own reflections below, faintly blurring them with the slightest of ripples. Here, in the sunlight, was a languid place of dreams; by mellow, magic moonlight what wonder if there came hither certain of the last remnants and relics of an old superstitious people, seeking visions? And an old saw hath it, 'What ye seek for ye shall find.'

Helen looked up; already Howard had passed out of sight; already her father's two pack horses had followed the rancher's mare beyond the brushy flank of the hill and Longstreet himself would be out of her sight in another moment. She turned a last look upon the still pond and hurried on.

Now again, as upon yesterday and the day before, the desert seemed without limit about them. The hot sun mounted; the earth sweltered and baked and blistered. Heat waves shimmered in the distances; the distances themselves were withdrawn into the veil of ultimate distances over which the blazing heat lay in what seemed palpable strata; crunching rock and gravel in the dry water-courses burned through thick sole-leather; burning particles of sand got into boots and irritated the skin; humans and horses toiled on, hour after hour, from early listlessness to weariness and, before noon, to parched misery. Even Howard, who confessed that he was little used to walking, admitted that this sort of thing made no great hit with him. During the forenoon he again offered his mount to Helen; when she sought to demur and hoped to be persuaded, he suggested a compromise; they would take turns, she, her father and himself. By noon, when they camped for lunch and a two hours' rest, all three had ridden.

Barely perceptibly the sweeps about them had altered during the last hour before midday. Here and there were low hills dotted occasionally by trees, covered with sparse dry grass. Here, said Howard, were the outer fringes of the grazing land; his cattle sometimes strayed as far as this. The spot chosen for nooning was a suspicion less breathlessly hot; there was a sluggish spring ringed about with wiry green grass and shaded by a clump of mongrel trees.

Helen ate little and then lay down and slept. Longstreet, his knees gathered in his arms, his back to a tree, sat staring thoughtfully across the billowing country before them; Howard smoked a cigarette, stood a moment looking curiously down at the weary figure of the girl, and then strode off to the next shade for his own siesta.

'Rode pretty well all night,' he explained half apologetically to Longstreet as he went. 'And haven't walked this much since last time.'

Between two and three they started on again. It grew cooler; constantly as they went forward the earth showed growing signs of fertility and, here and there, of moisture guarded and treasured under a shaggy coat of herbage. Within the first hour they glimpsed a number of scattered cattle and mules; once Helen cried out at the discovery of a small herd of deer browsing in a shaded draw. Then came a low divide; upon its crest was an outcropping of rock. Here Howard waited until his two companions came up with him; from here he pointed, sweeping his arm widely from north to east and south of east.

'The Last Ridge country, yonder,' he said.

They saw it against the north-eastern horizon. From the base of the hills on which they stood a broad valley spread out generously. Marking the valley's northern boundary some half- dozen miles away, thrown up against the sky like a bulwark, was a long broken ridge like a wall of cliff, an embankment stained the many colours of the south-west; red it looked in streaks and yellow and orange and even lavender and pale elusive green. It swept in a broad, irregular curve about the further level lands; it was carved and notched along its crest into strange shapes, here thrusting upward in a single needle-like tower, there offering to the clear sky a growth like a monster toadstool, again notched into saw-tooth edges.

'And here,' said Howard, his voice eloquent of his pride of ownership, 'my valley lands. From Last Ridge to the hills across yonder, from those hills as far as you can see to the south, mile after mile of it, it's mine, by the Lord! That is,' he amended with a slow smile under Helen's amazed eyes, 'when I get it all paid for! And there,' he continued, pointing this time to something white showing through the green of a grove upon a meadow land far off toward the southern rim of the valley, 'there is home. You'll know the way; I'm only twelve or fifteen miles from the Ridge, and so, you see, we're next-door neighbours.'

To Helen, as she gazed whither his finger led, came a strange, unaccustomed thrill. For the first time she felt the glory, and forgot the discomfort, of the hot sun and the hot land. There was a man's home; set apart from the world and yet sufficient unto itself; here was a man's holding, one man's, and it was as big and wide as a king's estate. She looked swiftly at the tall man at her side; it was his or would be his. And he need not have told her; what she had read in the timbre of his voice she saw written large in his eyes; they were bright with the joy of possession.

'Neighbours, folks,' he was saying. 'So let's begin things in neighbourly style. Come on home with me now; stick over a day or so resting up. Then I'll send a wagon and a couple of the boys over to the ridge with you and they'll lend you a hand at digging in for the length of your stay. It's the sensible thing,' he insisted argumentatively as he saw how Longstreet's gaze grew eager for the Ridge. 'And I'd consider it an honour, a high honour.'

'You are extremely kind, sir,' said Longstreet hesitatingly. 'But——'

'Come on,' cut in Howard warmly, his hand on the older man's shoulder. 'Just as a favour to me, neighbour. Everything's plain out our way; nothing fancy. But I've got clean beds to sleep in and the kitchen store-room's full and—— Why, man, I've even got a bathtub! Come ahead; be a sport and take a chance.'

Longstreet smiled; Helen watched him questioningly. Suddenly she realized that she was a trifle curious about Alan Howard; bath and clean beds did tempt her weary body, and besides there would be a certain interest in looking in upon the stranger's establishment. She wondered for the first time if there were a young Mrs. Howard awaiting him?

'How about it, Helen?' asked her father. 'Shall we accept further of this gentleman's kindness?'

'If we were sure,' hesitated Helen, 'that we would not be imposing——'

So it was settled, and Howard, highly pleased, led the way down into the valley. Making the gradual descent their trail, well marked now by the shod hoofs of horses, wound into a shady hollow. In the heart of this where there was a thin trickle of water Howard stopped abruptly. Helen, who was close to him, heard him mutter something under his breath and in a new tone of wrath. She looked at him wondering. He strode across the stream and stopped again; he stooped and she saw what he had seen; he straightened up and she saw blazing anger in his eyes.

Here, no longer ago than yesterday, a yearling beef had been slaughtered; the carcass lay half hidden by the bushes.

'Now who the hell did that for me?' cried out the man angrily. 'Look here; he's killed a beef for a couple of steaks. He's taken that and left the rest for the buzzards. The low-down, hog-hearted son of a scurvy coyote.'

Helen held back, frightened at what she read in his face. Her father came up with her and demanded:

'What is it? What's wrong?'

'Some one has killed one of his cows,' she whispered, catching hold of his arm. 'I believe he would kill the man who did it.'

Howard was looking about him for signs to tell whence the marauder had come, whither gone. He picked up a fresh rib bone, that had been hacked from its place with a heavy knife and then gnawed and broken as by a wolf's savage teeth. He noted something else; he went to it hurriedly. Upon a conspicuous rock, held in place by a smaller stone, was a small rawhide pouch. It was heavy in his palm; he opened it and poured its contents into his palm. And these contents he showed to Longstreet and Helen, looking at them wonderingly.

'The gent took what he wanted, but he paid for it,' he said slowly, 'in enough raw gold to buy half a dozen young beeves! That's fair enough, isn't it? The chances are he was in a hurry.'

'Maybe,' suggested Helen quickly, 'he was the same man whose camp fire we found. He was in a hurry.'

Howard pondered but finally shook his head. 'No; that man had bacon and coffee to leave behind him. It was some other jasper.'

Longstreet was absorbed in another interest. He took the unminted gold into his own hands, fingering it and studying it.

'It is around here everywhere, my dear,' he told Helen with his old placid assurance. 'It is quite as I have said; if you want fish, look for them in the sea; if you seek gold, not in insignificant quantities, but in a great, thick, rich ledge, come out toward the Last Ridge country.'

He returned the raw metal to Howard, who dropped it into its bag and the bag into his pocket. Silent now as each one found company in his own thoughts, they moved down the slope and into the valley.

THE world is an abiding-place of glory. He who cannot see it dyed and steeped in colourful hues owes it to his own happiness to gird up his loins and move on into another of the splendid chambers of the vast house God has given us; if the daily view before him no longer offers delight, it is merely and simply because his eyes have grown accustomed to what lies just before them and are wearied with it. For, after all, one but requires a complete change of environment to quicken eye and interest, to fill again the world with colour. Thus, put the man of the sea in the heart of the mountains and he stares about him at a thousand little things which pass unnoted under the calm eyes of the mountaineer. Or take up the dweller of the heights and set him aboard a wind-jammer bucking around the Horn and he will marvel at a sailor's song or the wide arc of a dizzy mast. So Helen Longstreet now, lifted from a college city of the East and set down upon the level floor of the West; so, in the less nervous way of greater years, her father.

The three were full two hours in walking from the base of the hills to Howard's ranch headquarters. Continuously the girl found fresh interests leaping into her quick consciousness. They waded knee-deep in lush grass of a meadow into which Howard had brought water from the hills; among the grass were strange flowers, red and yellow and blue, rising on tall stalks to lift their heads to the golden sun. From the grass rose birds, startled by their approach, one whirring away voicelessly from a hidden nest, another, a yellow and black-throated lark, singing joyously. They crossed the meadow and came up the swelling slope of a gentle hill; upon its flatfish top were oaks; in the shade of the oaks three black-and-white cows looked with mild, approving eyes upon their three tiny black-and-white calves. With the pictured memory unfading, Helen's eyes were momentarily held by an eagle balancing against the sky; the great bird, as though he were conscious that he held briefly centre stage, folded his wings and dropped like a falling stone; a ground squirrel shrilled its terror through the still afternoon and went racing with jerking tail toward safety; the great bird saw the frantic animal scuttle down a hole and unfolded its wings; again it balanced briefly, close to the ground; then in a wide spiral reascended the sky.

Came then wide fields with cattle browsing and drowsing; it was the first time Helen had harkened to a bellowing bull, the first time she had seen one of his breed with bent head pawing up grass and earth and flinging them over the straight line of his perfect back; she sensed his lusty challenge and listened breathlessly to the answering trumpet call from a distant, hidden corral. She saw a herd of young horses, twenty of them perhaps, racing wildly with flying manes and tails and flaring nostrils; a strangely garbed man on horseback raced after them, shot by them, heading them off, a wide loop of rope hissing above his head. She saw the rope leap out, seeming to the last alive and endowed with the will of the horseman; she heard the man laugh softly as the noose tightened about the slender neck of one of the fleeing horses.

'That's Gaucho,' said Howard. 'He's my horse breaker.'

But already the girl's interests had winged another way. Within ten steps they had come to a new view from a new vantage point. From some trick of sweep and slope the valley seemed more spacious than before; through a natural avenue in an oak grove they saw distinctly the still distant walls of the ranch house; the sun touched them and they gleamed back a spotless white. Helen was all eagerness to come to the main building; from afar, here of late having seen others of its type, she knew that it would be adobe and massive, old and cloaked with the romance of another time; that even doors and windows, let into the thick walls, would be of another period; that somewhere there would be a trellis with a sprawling grape-vine over it; that no doubt in the yard or along the fence would be the yellow Spanish roses.

Below the house they came to the stable. Here Howard paused to tie the three horses, but not to unpack or unsaddle.

'I haven't anybody just hanging around to do things like this for me,' he said lightly as he rejoined his guests. 'Not until I get the whole thing paid off. What men I've got are jumping on the job from sun-up to dark. I'll turn you loose in the house and then look after the stock myself.'

They passed several smaller outbuildings, some squat and ancient-looking adobes, others newer frame buildings, all neatly whitewashed. And then the home itself. Quite as Helen had provisioned, there was a low wooden fence about the garden; over the gateway were tangled rose vines disputing possession with a gnarled grape; the walk from the gate was outlined with the protruding ends of white earthen bottles, so in vogue in the southland a few years ago; a wide, coolly-dark veranda ran the length of the building; through three-feet-thick walls the doorways invited to further coolness. Howard stood aside for them to enter. They found underfoot a bare floor; it had been sprinkled from a watering pot earlier in the afternoon. The room was big and dusky; a few rawhide-bottomed chairs, a long rough table painted moss-green, some shelves with books, furnished the apartment. At one end was a fireplace.

Howard tossed his hat to the table and opened a door at one end of the room. Before them was a hallway; a few steps down were two doors, one on each hand, heavy old doors of thick slabs of oak, hand-hewn and with rough iron bands across them, top and bottom, the big nail heads showing. Howard threw one open, then the other.

'Your rooms,' he said. 'Yours, Miss Helen, opens upon the bath. You'll have to go down the hall to wash, professor. Make yourselves free with the whole house. I'll feed the horses and be with you in three shakes.'

Before his boot heels had done echoing through the living-room it was an adventure to Helen to peep into her room. She wondered what she was going to find. Thus far she had had no evidence of a woman upon the ranch. She knew the sort of housekeeper her father had demonstrated himself upon occasions when she had been away visiting; she fully counted upon seeing the traces of a man's hand here. But she was delightfully surprised. There was a big, old-fashioned walnut bed neatly made, covered in smooth whiteness by an ironed spread. There was a washstand with white pitcher like a ptarmigan in the white nest of a bowl, several towels with red bands towards their ends flanking it. There was a little rocking-chair, a table with some books. The window, because of the thickness of the wall, offered an inviting seat whence one could look into the tangle of roses of the patio.

'It is like a dream,' cried Helen. 'A dream come true.'

She glanced into her father's room. It was like hers in its neatness and appointments, but did not have her charming outlook. She was turning again into her own room when she heard Howard's voice outside.

'Angela,' he was calling, 'I have brought home friends. You will see that they have everything. There is a young lady. I am going to the stable.'

She heard Angela's mumbled answer. So there was, after all, at least one woman at the ranch. Helen awaited her expectantly, wondering who and what she might be. Then through her window she saw Angela come shuffling into the patio. She was an old woman, Mexican or Indian, her hair grey and black in streaks, her body bent over her thumping stick and wrapped in a heavy shawl. Never had Helen seen such night-black, fathomless, inscrutable eyes; never had she looked upon a face so creased and lined or skin so like dry, wrinkled parchment.

Angela pounded across the floor looking like a witch with her great stick, and waved a bony hand to indicate the bathroom. Catching her first glimpse of Longstreet, who came to his daughter's door, she demanded:

'Your papa?'

'Yes,' Helen answered her.

'You frien's Señor Alan?' And when Helen, hesitating briefly, said 'Yes,' Angela asked:

'You come from Santa Rita, no?'

'No,' said Helen. 'From San Juan and beyond.'

'You come far,' mumbled Angela. She scrutinized the girl keenly. Then abruptly, 'Senor Alan got muchos amigos to- day. Senor Juan Carr comes; El Joven with him.'

Helen asked politely who these two were Juan Carr and El Joven. But the old woman merely shook her head and relapsed into silence frankly studying her. The girl was glad of the interruption when Howard rapped at the door. His arms were full of bundles.

'I've brought everything I could find that looked like your and your father's personal traps,' he informed her as he came in and put the things down on the floor. 'I looked in at the kitchen and figure it out we've got about twenty or thirty minutes before dinner. Come on, Angela; give Miss Longstreet a chance to get ready.'

Angela transferred her scrutiny to him; Howard laughed at her good-humouredly, laid his hand gently on her shrunken shoulder and side by side they went out.

Helen went singing into her bath, her weary body rested by the thought of coolness and cleanliness and a change of clothing. Little enough did she have in the way of clothing, especially for an evening when she was to meet still other strangers. But certain feminine trinkets had come with her journeying across the desert, and a freshly laundered wash dress and a bit of bright ribbon work wonders. When she heard voices in the patio, that of Alan Howard and of another man, this a sonorous bass, she was ready. She went to her father's door; Longstreet was in the final stages of his own toilet-making, his face red and shiny from his towelling, his sparse hair on end, his whole being in that condition of bewildering untidiness which comes just before the ultimate desired orderliness quite as the thick darkness before the dawn. In this case the rose fingers of Aurora were Helen's own, patting, pulling and readjusting. Within three minutes she slipped her hand through the arm of a quiet scholarly looking gentleman and together they paced sedately into the patio.

Howard jumped up from a bench and dragged forward his friend John Carr, introducing him to his new friends. And in employing the word friend and repeating it, he spoke it as though he meant it. Here was a characteristic of the man; he was ready from dawn until dark to put out his big square hand to the world and bring the world home to his home for supper and bed and all that both connote.

But Helen's interest, at least for the flitting moment, was less for him than for his friend; Howard she had known since dawn, hence hers had been ample time to assign him his proper place in her human catalogue. Now she turned her level eyes upon the new man. Immediately she knew that if Alan Howard were an interesting type, then no less so, though in his own way, was John Carr. A bigger man, though not so tall; an older man by something like half a dozen years, but still young in the eyes and about the clean-shaven mouth; a man with clear, unwinking bluish-grey eyes and a fine head carried erect upon a massive brown throat. Carr was dressed well in a loose serge suit; he wore high-topped tan boots; his soft shirt was of good silk; his personality exuded both means and importance. He glanced at Longstreet and looked twice or three times as long at Longstreet's daughter. Helen was quite used to that, and it was for no particular reason that she felt her colour heighten a little. She slipped her hand through her father's arm again and they went in to supper. Howard, having indicated the way, clapped Carr upon the thick shoulders and the two friends brought up the rear.

Helen was still wondering where was the second guest; Angela had distinctly mentioned Juan Carr and another she termed El Joven. Yet as they passed from the patio into the big cool dining-room with its white cloth and plain service and stiff chairs, she saw no one here. Nor did she find any answer in the number of places set, but rather a confused wonder; the table was the length of the long room, and, at least in so far as number of plates went, suggested a banquet.

Howard drew out chairs at one end of the table so that the four sat together.

'The boys will be rolling in for supper in half an hour,' he explained. 'But you folks are hungry and will want to get to bed early, so we are not waiting for them.'

The 'boys' were, supposedly, the men he had working for him; there must be close to a score of them. And they all ate at one table, master and men and guests when he had them.

'Who is El Joven?' asked Helen.

Howard looked puzzled; then his face cleared.

'Angela told you El Joven was here, too?' And to Carr: 'He came with you, John?'

Carr nodded. Howard then answered Helen.

'That's Angela's pet name for him; it means The Youngster. It is Barbee, Yellow Barbee the boys call him. He's one of John's men. They say he's a regular devil-of-a-fellow with the ladies, Miss Helen. Look out he doesn't break your heart.'

Angela peered in from the kitchen and withdrew. They heard her guttural utterance, and thereafter a young Indian boy, black of eyes, slick of plastered hair and snow-white of apron, came in bringing the soup. Howard nodded at him, saying a pleasant 'Qué hay, Juanito?' The boy uncovered the rare whiteness of his splendid teeth in a quick smile. He began placing the soup. Helen looked at him; he blushed and withdrew hastily to the kitchen.

Throughout the meal the four talked unconstrainedly; it was as though they had known one another for a dozen years and intimately. Longstreet, having pushed aside his soup plate, engaged his host in an ardent discussion of the undeveloped possibilities of the Last Ridge country; true, he had never set foot upon it, but he knew the last word of this land's formation and geological construction, its life history as it were. All of his life, he admitted freely, he had been a man of scholarship and theory; the simplest thing imaginable, he held blandly, was the demonstration of the correctness of his theories. Meantime Helen talked brightly with John Carr and listened to Carr's voice.

And a voice well worth listening to it was. Its depth was at once remarkable and pleasing. At first one hearkened to the music of the rich tone itself rather than to the man's words, just as one may thrill to the profound cadences of a deep voice singing without heeding the words of the song. But presently she found herself giving her rapt attention to Carr's remarks. Here again was one of her own class, a man of quiet assurance and culture and distinction; he knew Boston and he knew the desert. For the first time since her father had dragged her across the continent on his hopelessly mad escapade, Helen felt that after all the East was not entirely remote from the West. Men like Howard and his friend John Carr, types she had never looked to find here, linked East and West.

Juanito, with lowered, bashful eyes, brought coffee, ripe olives from the can, potato salad, and thick, hot steaks. Soon thereafter the boys began to straggle in. Helen heard them at the gate, noisy and eager; for them the supper hour was diurnally a time of a joyous lift of spirit. They clattered along the porch like a crowd of schoolboys just dismissed; they washed outside by the kitchen door with much splashing; they plastered their hair with the common combs and brushes and entered the shortest way, by the kitchen. They called to each other back and forth; there was the sound of a tremendous clap as some big open hand fell resoundingly upon some tempting back and a roar from the stricken and a gale of booming laughter from the smiter and the scuffle of boots and the crashing of two big bodies falling. Then they came trooping in until fifteen or twenty had entered.

One by one Howard introduced them. Plainly none of them knew of Helen's presence; all of their eyes showed that. Among them were some few who grew abashed; for the most part they ducked their heads in acknowledgment and said stiffly, 'Pleased to meet you,' in wooden manner to both Longstreet and his daughter. But their noisiness departed from them and they sat down and ate in business-like style.

Never had Helen sat down with so rough a crowd. They were in shirt sleeves; some wore leathern wrist guards; their vests were open, their shirts dingy, they were unshaven and their hair grew long and ragged; they brought with them a smell of horses. There was one man among them who must have been sixty at the least, a wiry, stoop, white-haired, white-moustached Mexican. There were boys between seventeen and nineteen. There were Americans; at least one Swede; a Scotchman; several who might have been any sort of mixture of southern bloods. And among them all Helen knew at once, upon the instant that he swaggered in, El Joven, Yellow Barbee.

The two names fitted him as his two gloves may fit a man's hands; among the young he was The Youngster, as among blondes he was Yellow Barbee. His dress was extravagantly youthful; his boots bore the tallest heels, he was full-panoplied as to ornate wristbands and belt and chaps as though in full holiday attire; one might wager on the fact of his hat on a nail outside being the tallest crowned, the widest brimmed. His face was like a girl's for its smoothness and its prettiness; his eyes were like blue flowers of sweet innocence; on his forehead his hair was a cluster of little yellow ringlets. And yet he managed full well to convey the impression that he was less innocent than insolent, a somewhat true impression; for from high heels to finger-tips he was a downright, simon-pure rascal.

Yellow Barbee's eyes fairly invaded Helen's as he jerked her his bow. They were two youngsters, and in at least, and perhaps in at most, one matter they were alike: she prided herself that she 'knew' men, and to Barbee all women were an open, oft-read book.

Plainly Barbee was something of a favourite here; further, being a visitor, he was potentially of interest to the men who had not been off the ranch for matters of weeks and months. When Alan Howard and the professor picked up their conversation, and again Helen found herself monopolized by John Carr, from here and there about the table came pointed remarks to Yellow Barbee. Helen, though she listened to Carr and was never unconscious of her father and Howard, understood, after the strange fashion of women, all that was being said about her. Early she gathered that there was, somewhere in the world, a dashing young woman styled the 'Widow.' Further, she had the quick eyes to see that Barbee blushed when an old cattle-man with a roguish eye cleared his throat and made aloud some remark about Mrs. Murray. Yes; Barbee the insolent, the swaggering, the worldly-wise and conceited Barbee, actually blushed.

Though the hour was late it was not yet dark when the meal was done. Somehow Howard was at Helen's side when they went to the living-room and out to the front porch; Carr started with them, hesitated and held back, finally stepping over for a word with an old Mexican. Helen noted that Barbee had moved around the table and was talking with her father. As she and Howard found chairs on the porch, Longstreet and Barbee passed them and went out, talking together.

THE Longstreets remained several days upon Desert Valley Ranch, as the wide holding had been known for half a century. Also John Carr and his young retainer, Yellow Barbee, prolonged their stay. It appeared that Carr had come over from some vague place still further toward the east upon some matter of business connected with the sale of this broad acreage; Carr had owned the outfit and managed it personally for a dozen years, and now was selling to Alan Howard. It further devolved that Barbee had long been one of Carr's best horsemen, hence a favourite of Carr, who loved good horses, and that he had accompanied his employer merely to help drive over to the ranch a small herd of colts which had been included in the sale but had not until now been delivered. Carr was a great deal with Howard, and Howard managed to see a great deal of the Longstreets; as for Barbee, Helen met his insolent young eyes only at mealtimes.

'My business is over,' Carr confessed to Helen in the patio the next morning. 'There's no red tape and legal nonsense between Al and me. To sell a ranch like this, when you know the other chap, is like selling a horse. But,' and his eyes roved from his cigar to a glimpse through an open door of wide rolling meadows and grazing stock, 'I guess I'm sort of homesick for it. If it was to do over I don't know that I'd sell it this morning.'

Helen had rested well last night; this morning she had thrilled anew to the world about her. She thought that she had never seen such a sunrise; the day appeared almost to come leaping and shouting up out of the desert; the air of the morning, before the heat came, was nothing less than glorious. Her eyes were bright; there was the flush of joyousness in her cheeks.

'How a man could own this,' she said slowly, 'and then could sell it——' She shook her head and looked at him half wonderingly. 'I don't see how you could do it.'

'You feel that way about it, too?' He brought his eyes back soberly to his cigar.

Howard, whose swinging stride Helen had learned to know already, came out from the living-room, hat in hand, carrying a pair of spurs he had been tinkering with.

'What are you talking about?' he laughed. 'Somebody dead?'

'Miss Longstreet was saying,' Carr said quietly, his eyes still grave, 'that she couldn't understand a man selling an outfit like this, once he had called it his own.'

'Good for you, Miss Helen,' cried Howard heartily. 'I am with you on that. John, there, must have been out of his senses when he let me talk him out of Desert Valley.'

'I don't know but that I was,' said Carr.

Howard looked at him swiftly, and swiftly the light in his eyes altered. For Carr had spoken thoughtfully and soberly, and there was no hint of jest in the man.

'You don't mean, John,' said Alan, a trifle uncertainly, 'that you are sorry you let go? That you are not satisfied——'

Carr appeared to be considering the matter as though it were enwrapped in his cigar. He took ample time in replying, so much time, in fact, that Helen found herself growing impatient for his reply.

'Suppose I were sorry?' he said finally. 'Suppose I were not satisfied? Then what? The deal is made, and a bargain, old- timer, is a bargain.'

Now it was Howard's turn for silence and sober eyes. He looked intently into his friend's face; then with a lingering affection across his broad lands.

'Not between friends,' he said. 'Not between friends like you and me, John. I've hardly got my hooks into it; you had it long enough for it to get to be a part of you. If you made a mistake in selling, if you know it now——' He shrugged and smiled. 'Why, of course it doesn't mean as much to me as to you, and anyway, it's yours until I get all my payments made, and if you say the word——'

'Well?' asked Carr steadily.

'Why,' cried Howard, 'we'll frame a new deal this very minute and you can take it over again!'

'You'd do that for me, Al?'

'You're damned well right, I would!' cried Howard heartily. And Helen understood that for the moment at least he had forgotten that she was present.

A slow smile came into Carr's eyes.

'That's square shooting, Long Boy.'—he spoke more impetuously than Helen had thought the man could—'but I never went back on a play yet, did I? I'm just sort of homesick for the old place, that's all. Forget it.' He slapped Howard upon the shoulder, the two friends' eyes met for a moment of utter understanding and he went on down to the stable, calling back, 'I'm going to take the best horse you've got—that would be Bel and no other—and ride. So long.'

'So long,' answered Howard.

Carr gone from sight, Howard stood musing a moment, unconscious of Helen's wondering eyes upon him. Then he turned to her and began speaking of his friend: big and generous and manly was Carr; a man to tie to, and, though he did not say it in so many words, a man to die for. He explained how Carr had taken the old Diaz ranch that had been Spanish and then Mexican in its time and had made it over into what it was, the greatest stock run north of the Rio Grande and west of the Mississippi. Helen's interest was ready and sympathetic, and Howard passed from one point to another until he had sketched the way in which the ranch had been sold to him. And the girl, though she knew little enough about business methods, was startled to learn how these two men trusted each other. She recalled what Carr had said; between him and Howard a deal involving many thousands of dollars was as simple a matter as the sale of a horse. The two, riding together, had in a few words agreed upon price and terms. They had returned to the house and Howard had written a cheque for seven thousand dollars as first payment; all of his ready cash, he admitted freely, saving what he must keep on hand for ranch manipulation. There was no deed given, no deed of trust, no mortgage. It was understood that Howard should pay certain sums at certain specified dates; each man had jotted down his memoranda in his own hand; the deal was made.

'But,' gasped Helen, 'if anything unforeseen should happen? If—if he should die? Or you? If——'

'In any case there would be one of us left, wouldn't there?' he countered in his off-hand way. 'Unless we both went out, and then what difference? He has no one to look out for; neither have I. Besides,' he laughed carelessly, 'John and I both plan on being on the job a good fifty years from now. Come out here and I'll show you a real horse.'

She went with him to the porch. Carr was leaving the stable, riding Bel. Helen knew little enough of horseflesh and yet she understood that here was an animal to catch anyone's eye; yes, and Carr, sitting massive and stalwart in the saddle, was a man to hold any woman's. The horse was a big, bright bay; mane and tail were like fine gold; the sun winked back from them and from the glorious reddish hide. Carr saw them and waved his hat; Bel danced sideways and whirled, and for an instant stood upon his rear legs, his thin, aristocratic forelegs flaying the air. Then came Carr's deep bass laugh; the polished hoofs struck the ground and they were off, flashing away across the meadowlands.

'Some day,' said Helen, her eyes sparkling, 'I want to ride a horse like that!' She turned to him, asking eagerly, 'Could I learn?'