RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

Everybody's Magazine, October 1917, with first part of "Judith of Blue Lake Ranch"

"Judith of Blue Lake Ranch," Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1919

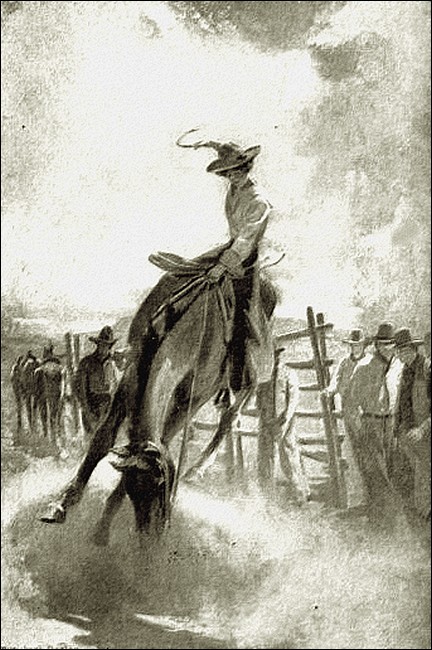

Frontispiece.

Judith's spurs answered him, and the bit brought him about,

bucking as only a devil-hearted horse knows how to buck.

BUD LEE, horse foreman of the Blue Lake Ranch, sat upon the gate of the home corral, builded a cigarette with slow brown fingers, and stared across the broken fields of the upper valley to the rosy glow above the pine-timbered ridge where the sun was coming up. His customary gravity was unusually pronounced.

"If a man's got the hunch an egg is bad," he mused, "is that a real good and sufficient reason why he should go poking his finger inside the shell? I want to know!"

Tommy Burkitt, the youngest wage-earner of the outfit and a profound admirer of all that taciturnity, good-humor, and quick capability which went into the make-up of Bud Lee, approached from the ranch-house on the knoll. "Hi, Bud!" he called. "Trevors wants you. On the jump."

Lee watched Tommy coming on with that wide, rocking gait of a man used to much riding and little walking. The deep gravity in the foreman's eyes was touched with a little twinkle by way of greeting.

Burkitt stopped at the gate, looking up at Lee. "On the jump, Trevors said," he repeated.

"The hell he did," said Lee pleasantly. "How old are you this morning, Tommy?"

Burkitt blushed. "Aw, quit it, Bud," he grinned. Involuntarily the boy's big square hand rose to the tender growth upon lip and chin which, like the flush in the eastern sky, was but a vague promise of a greater glory to be.

"A hair for each year," continued the quiet-voiced man. "Ten on one side, nine on the other."

"Ain't you going to do what Trevors says?" demanded Tommy.

For a moment Lee sat still, his cigarette unlighted, his broad black hat far back upon his close-cropped hair, his eyes serenely contemplative upon the pink of the sky above the pines. Then he slipped from his place and, though each single movement gave an impression of great leisureliness, it was but a flash of time until he stood beside Burkitt.

"Stick around a wee bit, laddie," he said gently, a lean brown hand resting lightly on the boy's square shoulder. "A man can't see what is on the cards until they're tipped, but it's always a fair gamble that between dawn and dusk I'll gather up my string of colts and crowd on. If I do, you'll want to come along?"

He smiled at young Burkitt's eagerness and turned away toward the ranch-house and Bayne Trevors, thus putting an early end to an enthusiastic acquiescence. Tommy watched the tall man moving swiftly away through the brightening dawn.

"They ain't no more men ever foaled like him," meditated Tommy, in an approval so profound as to be little less than out- and-out devotion.

And, indeed, one might ride up and down the world for many a day and not find a man who was Bud Lee's superior in "the things that count." As tall as most, with sufficient shoulders, a slender body, narrow-hipped, he carried himself as perhaps his forebears walked in a day when open forests or sheltered caverns housed them, with a lithe gracefulness born of the perfect play of superb physical development. His muscles, even in the slightest movement, flowed liquidly; he had slipped from his place on the corral gate less like a man than like some great, splendid cat. The skin of hands, face, throat, was very dark, whether by inheritance or because of long exposure to sun and wind, it would have been difficult to say. The eyes were dark, very keen, and yet reminiscently grave. From under their black brows they had the habit of appearing to be reluctantly withdrawn from some great distance to come to rest, steady and calm, upon the man with whom he chanced to be speaking. Such are the serene, dispassionate eyes of one who for many months of the year goes companionless, save for what communion he may find in the silent passes of the mountains, in the wide sweep of the meadow- lands or in the soul of his horse.

The gaunt, sure-footed form was lost to Tommy's eyes; Lee had passed beyond the clump of wild lilacs whose glistening, heart- shaped leaves screened the open court about which the ranch-house was built. A strangely elaborate ranch-house, this one, set here so far apart from the world of rich residences. There was a score of rooms in the great, one-story, rambling edifice of rudely squared timbers set in field-stone and cement, rooms now closed and locked; there were flower-gardens still cultivated daily by José, the half-breed; a pretty court with a fountain and many roses, out upon which a dozen doorways looked; wide verandas with glimpses beyond of fireplaces and long expanses of polished floor. For, until recently, this had been not only the headquarters of Blue Lake Ranch, but the home as well of the chief of its several owners. Luke Sanford, whose own efforts alone had made him at forty-five a man to be reckoned with, had followed his fancy here extensively and expensively, allowing himself this one luxury of his many lean, hard years. Then, six months ago, just as his ambitions were stepping to fresh heights, just as his hands were filling with newer, greater endeavor, there had come the mishap in the mountains and Sanford's tragic death.

Lee passed silently through the courtyard, by the fountain which in the brightening air was like a chain of silver run through invisible hands, down the veranda bathed in the perfume of full-blown roses, and so came to the door at the far end. The door stood open; within was the office of Bayne Trevors, general manager. Lee entered, his hat still far back upon his head. The sound of his boots upon the bare floor caused Trevors to look up quickly.

"Hello, Lee," he said quietly. "Wait a minute, will you?"

Quite a different type from Lee, Bayne Trevors was heavy and square and hard. His eyes were the glinting gray eyes of a man who is forceful, dynamic, the sort of man who is a better captain than lieutenant, whose hands are strong to grasp life by the throat and demand that she stand and deliver. Only because of his wide and successful experience, of his initiative, of his way of quick, decisive action mated to a marked executive ability, had Luke Sanford chosen Bayne Trevors as his right-hand man in so colossal a venture as the Blue Lake Ranch. Only because of the same pushing, vigorous personality was he this morning general manager, with the unlimited authority of a dictator over a petty principality.

In a moment Trevors lifted his frowning eyes from the table, turning in his chair to confront Lee, who stood lounging in leisurely manner against the door-jamb.

"That young idiot wants money again," he growled, his voice as sharp and quick as his eyes. "As if I didn't have enough to contend with already!"

"Meaning young Hampton, I take it?" said Lee quietly.

Trevors nodded savagely.

"Telegram. Caught it over the line the last thing last night. We'll have to sell some horses this time, Lee."

Lee's eyes narrowed imperceptibly. "I didn't plan to do any selling for six months yet," he said, not in expostulation but merely in explanation. "They're not ready."

"How many three-year-olds have you got in your string in Big Meadow?" asked Trevors crisply.

"Counting those eleven Red Duke colts?"

"Counting everything. How many?"

"Seventy-three."

The general manager's pencil wrote upon the pad in front of him "73," then swiftly multiplied it by 50. Lee saw the result, 3,650 set down with the dollar sign in front of it. He said nothing.

"What would you say to fifty dollars a head for them?" asked Trevors, whirling again in his swivel chair. "Three thousand six fifty for the bunch?"

"I'd say the same," answered Lee deliberately, "that I'd say to a man that offered me two bits for Daylight or Ladybird. I just naturally wouldn't say anything at all."

"Who are Daylight and Ladybird?" demanded Trevors.

"They're two of my little horses," said Lee gently, "that no man's got the money to buy."

Trevors smiled cynically. "What are the seventy-three colts worth then?"

"Right now, when I'm just ready to break 'em in," said Bud Lee thoughtfully, "the worst of that string is worth fifty dollars. I'd say twenty of the herd ought to bring fifty dollars a head; twenty more ought to bring sixty; ten are worth seventy-five; ten are worth an even hundred; seven of the Red Duke stock are good for a hundred and a quarter; the other four Red Dukes and the three Robert the Devils are worth a hundred and fifty a head. The whole bunch, an easy fifty-seven hundred little iron men. Which," he continued dryly, "is considerable more than the thirty-six hundred you're talking about. And, give me six months, and I'll boost that fifty-seven hundred. Lord, man, that chestnut out of Black Babe by Hazard, is a real horse! Fifty dollars——"

He stared hard at Trevors a moment. And then, partially voicing the thought with which he had grappled upon the corral gate, he added meditatively: "There's something almighty peculiar about an outfit that will listen to a man offer fifty bucks on a string like that."

His eyes, cool and steady, met Trevors's in a long look which was little short of a challenge.

"Just how far does that go, Lee?" asked the manager curtly.

"As far as you like," replied the horse foreman coolly. "Are you going to sell those three-year-olds for thirty-six hundred?"

"Yes," answered Trevors bluntly, "I am. What are you going to do about it?"

"Ask for my time, I guess," and although his voice was gentle and even pleasant, his eyes were hard. "I'll take my own little string and move on.

"Curse it!" cried Trevors heatedly. "What difference does it make to you? What business is it of yours how I sell? You draw down your monthly pay, don't you? I raised you a notch last month without your asking for it, didn't I?"

"That's so," agreed the foreman equably. "It's a cinch none of the boys have any kick coming at the wages."

For a moment Trevors sat frowning up at Lee's inscrutable face. Then he laughed shortly. "Look here, Bud," he said good- humoredly, an obvious seriousness of purpose under the light tone. "I want to talk with you before you do anything rash. Sit down." But Lee remained standing, merely saying, "Shoot."

"I wonder," explained Trevors, "if the boys understand just the size of the job I've got in my hands? You know that the ranch is a million-dollar outfit; you know that you can ride fifteen miles without getting off the home-range; you know that we are doing a dozen different kinds of farming and stock- raising. But you don't know just how short the money is! There's that young idiot now, Hampton. He holds a third interest and I've got to consider what he says, even if he is a weak-minded, inbred pup that can't do anything but spend an inheritance like the born fool he is. His share is mortgaged; I've tried to pay the mortgage off. I've got to keep the interest up. Interest alone amounts, to three thousand dollars a year. Think of that! Then there's Luke Sanford dead and his one-third interest left to another young fool, a girl!"

Trevors's fist came smashing down upon his table. "A girl!" he repeated savagely. "Worse than young Hampton, by Heaven! Every two weeks she's writing for a report, eternally butting in, making suggestions, hampering me until I'm sick of the job."

"That would be Luke's girl, Judith?"

"Yes. Two of the three owners' kids, writing me at every turn. And the third owner, Timothy Gray, the only sensible one of the lot, has just up and sold out his share, and I suppose I'll be hearing next that some superannuated female in an old lady's home has inherited a fortune and bought him out. Why, do you think I'd hold on to my job here for ten minutes if it wasn't that my reputation is in making a go of the thing? And now you, the best man I've got, throw me down!"

"I don't see," said Lee slowly, after a brief pause, "just what good it does to sell a string of real horses like they were sheep. Half of that herd is real horse-flesh, I tell you."

"Hampton wants money. And besides, a horse is a horse."

"Is it?" A hard smile touched Lee's lips. "That's just where a man makes a mistake. Some horses are cows, some are clean spirit. You can stake your boots on that, Trevors."

"Well," snapped Trevors, "suppose you are right. I've got to raise three thousand dollars in a hurry. Where will I get it?"

"Who is offering fifty dollars a head for those horses?" asked Lee abruptly. "It might be the Big Western Lumber Company?"

"Yes."

"Uh-huh. Well, you can kill the rats in your own barn, Trevors. I'll go look for a job somewhere else."

Bayne Trevors, his lips tightly compressed, his eyes steady, a faint, angry flush in his cheeks, checked what words were flowing to his tongue and looked keenly at his foreman. Lee met his regard with cool unconcern. Then, just as Trevors was about to speak, there came an interruption.

THE quiet of the morning was broken by the quick thud of a horse's shod hoofs on the hard ground of the courtyard. Bud Lee in the doorway turned to see a strange horse drawn up so that upon its four bunched hoofs it slid to a standstill; saw a slender figure, which in the early light he mistook for a boy, slip out of the saddle. And then, suddenly, a girl, the spurs of her little riding-boots making jingling music on the veranda, her riding-quirt swinging from her wrist, had stepped by him and was looking with bright, snapping eyes from him to Trevors.

"I am Judith Sanford," she announced briefly, and there was a note in her young voice which went ringing, bell-like, through the still air. "Is one of you men Bayne Trevors?"

A quick, shadowy smile came and went upon the lips of Bud Lee. It struck him that she might have said in just that way: "I am the Queen of England and I am running my own kingdom!" He looked at her with eyes filled with open interest and curiosity, making swift appraisal of the flush in the sun-browned cheeks, the confusion of dark, curling hair disturbed by her furious riding, the vivid, red-blooded beauty of her. Mouth and eyes and the very carriage of the dark head upon her superb white throat announced boldly and triumphantly that here was no wax-petalled lily of a lady but rather a maid whose blood, like the blood of the father before her, was turbulent and hot and must boil like a wild mountain-stream at opposition. Her eyes, a little darker than Trevors's, were the eyes of fighting stock.

Trevors, irritated already, turned hard eyes up at her from under corrugated brows. He did not move in his chair. Nor did Lee stir except that now he removed his hat.

"I am Trevors," said the general manager curtly. "And, whether you are Judith Sanford or the Queen of Siam, I am busy right now."

"He got the queen idea, too!" was the quick thought back of Bud Lee's fading smile.

"You talk soft with me, Trevors!" cried the girl passionately, "if you want to hold your job five minutes! I'll tolerate none of your high and mighty airs!"

Trevors laughed at her, a sneer in his laugh. "I talk the way I talk," he answered roughly. "If people don't like the sound of it they don't have to listen! Lee, you round up those seventy- three horses and crowd them over the ridge to the lumber-camp. Or, if you want to quit, quit now and I'll send a sane man."

The hot color mounted higher in the girl's face, a new anger leaped up in her eyes.

"Take no orders this morning that I don't give," she said, for a moment turning her eyes upon Lee. And to Trevors: "Busy or not busy, you take time right now to answer my questions. I've got your reports and all they tell me is that you are going in the hole as fast as you can. You are spending thousands of dollars needlessly. What business have you got selling off my young steers at a sacrifice? What in the name of folly did you build those three miles of fence for?"

"Go get those horses, Lee," said Trevors, ignoring her.

Again she spoke to Lee, saying crisply: "What horses is he talking about?"

With his deep gravity at its deepest, Bud Lee answered: "All L-S stock. The eleven Red Duke three-year-olds; the two Robert the Devil colts; Brown Babe's filly, Comet——"

"All mine, every running hoof of 'em," she said, cutting in. "What does Trevors want you to do with them? Give them away for ten dollars a head or cut their throats?"

"Look here—" cried Trevors angrily, on his feet now.

"You shut up!" commanded the girl sharply. "Lee, you answer me."

"He's selling them fifty dollars a head," he said with a secret joy in his heart as he glanced at Trevors's flushed face.

"Fifty dollars!" Judith gasped. "Fifty dollars for a Red Duke colt like Comet!"

She stared at Lee as though she could not believe it. He merely stared back at her, wondering just how much she knew about horse-flesh.

Then, suddenly, she whirled again upon Trevors.

"I came out to see if you were a crook or just a fool," she told him, her words like a slap in his face. "No man could be so big a fool as that! You—you crook!"

The muscles under Bayne Trevors's jaws corded. "You've said about enough," he shot back at her. "And even if you do own a third of this outfit, I'll have you understand that I am the manager here and that I do what I like."

From her bosom she snatched a big envelope, tossing it to the table. "Look at that," she ordered him. "You big thief! I've mortgaged my holding for fifty thousand dollars and I've bought in Timothy Gray's share. I swing two votes out of three now, Bayne Trevors. And the first thing I do is run you out, you great big grafting fathead! You would chuck Luke Sanford's outfit to the dogs, would you? Get off the ranch. You're fired!"

"You can't do a thing like this!" snapped Trevors, after one swift glance at the papers he had whisked out of their covering.

"I can't, can't I?" she jeered at him. "Don't you fool yourself for one little minute! Pack your little trunk and hammer the trail."

"I'll do nothing of the kind. Why, I don't know even who you are! You say that you are Judith Sanford." He shrugged his massive shoulders. "How do I know what game you are up to? Wayward maidens," and in his rage he sneered at her evilly, "have been known before to lie like other people!"

"You can't bluff me for two seconds, Bayne Trevors," she blazed at him. "You know who I am, all right. Send for Sunny Harper," she ended sharply.

"Discharged three months ago," Trevors told her with a show of teeth.

"Johnny Hodge, then," she commanded. "Or Tod Bruce or Bing Kelley. They all know me."

"Fired long ago, all of them," laughed Trevors, "to make room for competent men."

"To make room for more crooks!" she cried, her own brown hands balled into fists scarcely less hard than Trevors's had been. Then for the third time she turned upon Lee. "You are one of his new thieves, I suppose?"

"Thank you, ma'am," said Bud Lee gravely.

"Well, answer me. Are you?"

"No, ma'am," he told her, with no hint of a twinkle in his calm eyes. "Leastwise, not his exactly. You see, I do all my killing and highway robbing on my own hook. It's just a way I have."

"Well," Judith sniffed, "I don't know. It will be a jolt to me if there's a square man left on the ranch! Go down to the bunk-house and tell the cook I'm here and I'm hungry as a wild- cat. Tell him and any of the boys that are down there that I've come to stay and that Trevors is fired. They take orders from me and no one else. And hurry, if you know how. Goodness knows, you look as though it would take you half an hour to turn around!"

"Thank you, ma'am," said Bud Lee. "But you see I had just told Trevors here he could count me out. I'm not working for the Blue Lake any more. As I go down to the corral, shall I send up one of the boys to take your orders?"

There was a little smile under the last words, just as there was a little smile in Bud Lee's heart at the thought of the boys taking orders from a little slip of a girl. Inside he was chuckling, vastly delighted with the comedy of the morning.

"She's a sure-enough little wonder-bird, all right," he mused. "But, say, what does she want to butt in on a man's-size job for, I want to know?"

"Lee," called Trevors, "you take orders from me or no one on this ranch. You can go now. And just keep your mouth shut."

Bud Lee stood there in the doorway, his hat spinning upon a brown forefinger, his thoughts his own. He was turning to go out and down to his horse when he saw the look in Trevors's eyes, a look of consuming rage. The general manager's voice had been hoarse.

"I guess," said Lee quietly, "that I'll stick around until you two get through quarrelling. I might come in handy somehow."

"Damn you," shouted Trevors, "get out!"

"Cut out the swear-words, Trevors," said Lee with quiet sternness. "There's a lady here."

"Lady!" scoffed Trevors. He laughed contemptuously. "Where's your lady? That?" and he levelled a scornful finger at the girl. "A ranting tough of a female who brings a breath of the stables with her and scolds like a fishwife...."

"Shut up!" said Lee, crossing the room with quick strides, his face thrust forward a little.

"You shut up!" It was Judith's voice as Judith's hand fell upon Bud Lee's shoulder, pushing him aside. "If I couldn't take care of myself do you think I'd be fool enough to take over a job like running the Blue Lake? Now—" and with blazing eyes she confronted Trevors—"if you've got any more nice little things to say, suppose you say them to me!"

Trevors's temper had had ample provocation and now stood naked and hot in his hard eyes. In a blind instant he laid his tongue to a word which would have sent Bud Lee at his throat. But Judith stood between them and, like an echo to the word, came the resounding slap as Judith's open palm smote Trevors's cheek.

"You wildcat!" he cried. And his two big hands flew out, seeking her shoulders.

"Stand back!" called Judith. "Just because you are bigger than I am, don't make any mistake! Stand back, I tell you!"

Bud Lee marvelled at the swiftness with which her hand had gone into her blouse and out again, a small-caliber revolver in the steady fingers now. He had never known a man—himself possibly excepted—quicker at the draw.

But Bayne Trevors, from whose make-up cowardice had been omitted, laughed sneeringly at her and did not stand back. His two hands out before him, his face crimson, he came on.

"Fool!" cried the girl. "Fool!"

Still he came on. Lee gathered himself to spring.

Judith fired. Once, and Trevors's right arm fell to his side. A second time, and Trevors's left arm hung limp like the other. The crimson was gone from his face now. It was dead white. Little beads of sweat began to form on his brow.

Lee turned astonished eyes to Judith.

"Now you know who's running this outfit, don't you?" she said coolly. "Lee, have a team hitched up to carry Trevors wherever he wants to go. He's not hurt much; I just winged him. And then tell the cook about my breakfast."

But Lee stood and looked at her. He had no remark to offer. Then he turned to go upon her bidding. As he went down to the bunk-house he said softly under his breath: "Well, I'm damned. I most certainly am!"

WRINKLED, grizzled old half-breed José, his hands trembling with eagerness, stood in the smaller rose-garden culling the perfect buds, a joyous tear running its zigzag way down each cheek.

"La señorita ees come home!" he announced triumphantly as Lee drew near on his way to the bunk-house. "Jesús Maria! Een my heart it is like the singing of leetle birdies. Mira, señor. My flowers bloomin' the brighter, already—no?"

Bud Lee paused. "So you know Miss Sanford then?" he asked.

José threw out his hands and opened his night-black eyes to their most enormous extent. "Do I know God?" he demanded.

"Well," smiled Bud, "as to that...."

"But, señor," cried the devout José, "like on holy days I feel that Dios comes to sit down in the corner of my heart, so without seeing la señorita I know she ees come home! She ees in the air like the light of sun, like the sweetness of my roses!"

"You've known her a long time, Joe?"

"Seence she ees born!" and José, unashamed, wiped away a tear upon the back of a leathery hand. "Señor Sanford and me, señor, we teach her when she ees so leetle!" José's shaking hand was lowered until it marked the stature of a twelve- inch pigmy. In all things must the old fellow gain his emphasis by exaggeration which more often than not took the form of plain lying. "Never at all unteel one year ago does she leave us and the rancho. We, us two who love her, señor, learn her to walk and to ride and to shoot and to talk. You shall hear her say, 'Buenos dias, José, mi amigo!' You shall see her kees the cheek of old José."

Again his leathery hand was put in requisition, this time to wipe clean the cheek to be honored. "And one theeng I tell you, señor," he added confidentially. "Her papa was a wild devil before her. Her mama ees grow up on the ranch; and when she marry el señor Sanford was like a wild boy. And mi señorita, she ees the cross be tween a wild devil and a sweet saint, señor Madre de Dios! I would go down to hell for her to bring back fire to warm her leetle feet een weenter!"

Lee went thoughtfully on his way to the bunk-house. The cook, an importation of Bayne Trevors, a big, upstanding fellow with bare arms covered with flour, was putting on the breakfast to which a dozen rough-garbed men were sitting down.

"I've got orders for you fellows," said Lee from the doorway. "The boss of the outfit, the real owner, you know, just blew in. Up at the house. Says you boys are to stick around to take orders straight from headquarters. You, Benny," to the cook, "are to have a man's-size breakfast ready in a jiffy."

Naturally Benny led the clamor with a string of oaths. What in blazes did the owner of the ranch have to show up for anyway?—he wanted to know. He accepted the fact as a personal affront. Who was this owner?—demanded Ward Hannon, the foreman of the lower ranch, where the alfalfa-fields were.

Bud Lee explained gravely that the newcomer was some sort of relative of old Luke Sanford, who had recently acquired a controlling interest in the ranch. Ward Hannon grunted contemptuously. "The Lord deliver us!" he moaned. "Eastern jasper! One of the know-all-about-it brand, huh, Bud? I'll bet he combs his hair in the middle and smokes cigareets out'n a box! The putty-headed loons can't even roll their own smokes."

"Don't believe," hazarded Lee indifferently, "from the looks of our visitor that—that the owner smokes anything!"

"Listen to that!" grunted Ward Hannon.

"Softy, huh?"

"Well," Bud admitted slowly, "looks sort of like a girl, you know!"

"Wouldn't that choke you?" demanded Carson, the cow foreman, a thin, awkward little man, gray in the service of "real men." "Taking orders off'n a fool Easterner's bad enough. But old man or young, Bud?"

"Just a kid," was Lee's further dampening news. And as he nonchalantly buttered his hotcakes he added carelessly: "Something of a scrapper, though. Just put two thirty-two calibers into Trevors."

They stared at him incredulously. Then Carson's dry cackle led the laughter.

"You're the biggest liar, Bud Lee," said the old man good- naturedly, "I ever focussed my two eyes on. I'll lay an even bet there ain't nobody showed a-tall up this morning."

"You, Tommy," said Lee to the boy at his side, "shovel your grub down lively and go hitch Molly and old Pie-face to the buckboard. That's orders from headquarters," he grinned. "Trevors is to be hauled away first thing."

Tommy looked curiously at his superior. "On the level, Bud?" he asked doubtingly.

"On the level, laddie," was the quiet response.

And young Burkitt, wondering, but doubting no longer, hastened with his breakfast.

The others, looking at Lee's sober face questioningly, fired a broadside of inquiries at him. But they got no further information.

"I've told you boys all the news," he announced positively. "Lordy! Isn't that an earful for this time of day? The real boss is on the job: Trevors is winged; you are to stick around for orders from headquarters. If you want to know any more'n that, why—just go up to the house and ask your blamed questions."

Out of the tail of his eye he saw the swift approach of Bayne Trevors. The general manager's face was black with rage and through that dark wrath showed a dull red flush of shame. He walked with his two arms lax at his sides.

"Give me a cup of coffee, Ben," he commanded curtly, slumping into a chair. "Hurry!"

Benny, looking at him curiously, brought a steaming cup and offered it. Trevors moved to lift a hand; then sank back a little farther in his chair, his face twisting in his pain.

"Put some milk in it," he snarled. "Then hold it to my mouth. For the love of Heaven, hurry, man!"

Then no man there doubted longer the mad tale Bud Lee had brought them. Down from Trevors's sleeves, staining each hand, there had come a broadening trickle of blood. Trevors set his teeth and waited. Benny at last cooled the coffee and held it to his lips. Trevors drank swiftly, draining the cup.

"Get this coat off me," he commanded. "Curse you, don't tear my arms off! Slit the sleeves."

Benny's big, razor-edged butcher-knife cut away coat and shirt sleeves. And at last, to the eager gaze of the men in the bunk- house, there appeared the two wounds, one upon the outer right shoulder, the other upon the left forearm.

It was Lee who, pushing the clumsy cook aside, silently made the two bandages from strips of Trevors's shirt. It was Lee who brought a flask of brandy from which Trevors drank deep.

And then came Judith.

They stared at her as they might have done had the heavens opened and an angel come down, or the earth split and a devil sprung up. She looked in upon them with quick, keen eyes which sought to take every man's measure. They returned her regard with a variety of amazed expressions. Never since these men had come to work for Bayne Trevors had a woman so much as ridden by the door. And to have her stand there, composed, utterly at her ease, her air vaguely authoritative, a vitally vivid being who might, suddenly, have taken tangible form from the dawn, bewildered them. Bud Lee had told of the coming of the Blue Lake owner; he had not mentioned that that owner had brought his daughter with him.

"I am Judith Sanford," she said in her abrupt fashion, quite as she had made the announcement to Lee and Trevors. "This outfit belongs to me. I have fired Trevors. You take your orders straight from me from now on. Cookie, give me some coffee."

She came in without ceremony and sat down at the head of the table. Benny gasped, stood for a moment rooted to the floor, and then, Judith's eyes hard upon him, hastily brought the coffee. From some emotion certainly not clear to him he went a violent red. Perhaps the emotion was just sheer embarrassment. He brought hot cakes with one hand while with the other he buttoned his gaping shirt-collar over a bulging, hairy chest.

Men who had finished their breakfasts rose hastily with a marked awkwardness and ill-concealed haste and went outside, whence their low voices came back in a confused consultation. Men who had not finished followed them. In an amazingly short time there were but the girl, Lee, Trevors and the cook in the room. Then Trevors went out, Benny at his heels. Bud Lee, moving with his usual leisureliness, was following when Judith's cool voice said quietly:

"You, Lee, wait a moment. I want to talk with you."

Lee hesitated. Then he came back and waited.

The men outside naturally grouped about the general manager. His angry voice, lifted clearly, reached the two in the room.

"I'm fired," said Trevors harshly. "As soon as I can get going I am leaving for the Western Lumber camp. Every one of you boys holds his job here because I gave it to him. Do you want to hold it now, with a fool girl telling you what to do? Do you want men up and down the State to laugh at you and jeer at you for a pack of softies and imbeciles? Or do you want to roll your blankets and quit? To every man that jumps the job here and follows me to-day I promise a job with the Western. You fellows know the sort of boss I've been to you. You can guess the sort of boss that chicken in there would be. Now I'm going. It's up to you. Stick to a white man or fuss around for a woman?"

He had said what he had to say and, cursing when his shoulder struck a form near him, made his way down to the stables. Burkitt was ahead of him, going for the team.

"Well, Lee," said Judith sharply, "where do you get off? Do you want to stick? Or shall I count you out?"

"I guess," said Bud very gently, "you'd better count me out."

"You're going with that crook?"

"No. I'm going on my own."

"Why? You're getting good money here. If you're square I'll keep you at the same figure."

But Bud shook his head.

"I'm game to play square," he said slowly. "I'll stick a week, giving you the chance to get a man in my place. That's all."

"What's the matter with you?" she cried hotly. "Why won't you stay with your job? Is it because you don't want to take orders from me?"

Then Lee lifted his grave eyes to hers and answered simply: "That's it. I'm not saying you're not all right. But I got it figured out, there's just two kinds of ladies. If you want to know, I don't see that you've got any call to tie into a man's job."

"Oh, scat!" cried the girl angrily. "You men make me tired. Two kinds of ladies! And ten thousand kinds of men! You want me to dress like a doll, I suppose, and keep my hands soft and white and go around like a brainless, simpering fool! There are two kinds of ladies, my fine friend: the kind that can and the kind that can't! Thank God I'm none of your precious, sighing, hothouse little fools!"

Gulping down a last mouthful of coffee, she was on her feet and passed swiftly out among the men.

"You men!" she cried, and they turned sober eyes upon her, "listen to me! You've heard that big stiff rant; now hear me! I'm here because I belong here. My dad was Luke Sanford and he made this ranch. I was raised here. It's two-thirds mine right now. Trevors there is a crook and I told him so. He's been trying to sell me out, to make such a failure of the outfit that I'd have to let it go for a comic song. He got gay and I fired him. He tried to manhandle me and I plugged him. And now I am going to run my own outfit! What have you got to say about it, you grumbling old grouch with the crooked face! Put up or shut up! I'm calling you!"

The men turned from her to Ward Hannon, the field foreman, who had been Trevors's right-hand man and who now was sneering openly.

"I'm saying it's no work for a kid of a girl," grumbled Hannon. "You run an outfit like this?" He laughed derisively. "It can't be did."

"It can't, can't it?" cried Judith. "Tell me why, old smarty. Spit it out lively."

Jake Carson's shrill cackle cut through a low rumble of laughter. "That's passing it to him straight," said the old cattleman. "What's the word, Ward?"

Ward Hannon shrugged his shoulders and spat impudently. "I ain't saying nothing," he growled, "only this: I got a right to quit, ain't I? Well, I'm quitting. Any time you ketch me working for a female girl that can't ride a horse 'thout falling off, that can't see a pig stuck 'thout fainting, that can't walk a mile 'thout getting laid up, that can't...."

"Slow up there!" called Judith. "Didn't I stick a pig already this morning, and have I keeled over yet? Didn't I ride the forty miles from Rocky Bend last night and get here before sun- up? Listen to me, chief kicker: If you've got a horse on the ranch I can't ride I'll quit right now and give you my job! How's that strike you? I tell you the word on this ranch is going to be: 'Put up or shut up!' Which is it, Growly?"

Again the men laughed and Hannon's face showed his anger.

"Mean that, lady?" he demanded briefly.

"You can just bet your eyes I mean it!"

Hannon turned toward the stable. "All right. We'll see who's going to put or shut up!" he jeered over his shoulder. "You ride the Prince just two little minutes and I'll stay and work for you!"

Bud Lee from the doorway interfered. He was a man who loved fair play and he knew the Prince. "None of that, Ward," he called sternly. "Not the Prince!"

But Judith, her eyes aflame, whirled upon Lee, her voice like a whip as she said: "Lee, you keep out of this. The sooner you learn who's running things here the better for you."

"Maybe so," said Lee quietly. "But don't you fool yourself you can ride Prince. There's not a man on the job except me that can ride him." It was not boastfully said, but with calm assurance. "He's an outlaw, Miss Judith. He's the horse that killed Jimmy Carpenter last spring, and Jimmy——"

"Go ahead, Ward," ordered Judith. "You don't have to stop every time the wind blows, do you?"

Even Bud Lee smiled. But old Carson spoke up, saying: "Bud's right, miss. And if Ward wants to know, he's a low-down dawg to try to turn a trick like this...."

"Go ahead, Ward," Judith repeated. "I've got something to do to-day besides play pussy-wants-a-corner with you boys."

Ward went, his eyes filled with malice. Two or three of the other men joined their voices to Bud's and Carson's, expostulating, telling of that fearful thing, an outlaw horse. Judith maintained a scornful silence.

In due time Ward came back. He was leading a saddled horse, a great, wild-eyed roan that snapped viciously as he came on, walking with the wide, spreading stride of a horse little used to the saddle. Judith measured him with her eyes as she had measured the men in the bunk-house.

"He's an ugly devil," she said, and Lee, at her side, smiled again. But the girl had not altered her intention. She stepped closer, looking to cinch, bit, and reins. She commanded Ward to draw the latigo tighter, and Ward did so, dodging back as the big brute snapped at him.

Judith laughed. "Look out, Ward," she taunted him. "He's after your hair!"

Two men held the Prince. At Judith's command they shortened the stirrups and then blinded him with a bandanna handkerchief. Then, moving with almost incredible swiftness, she was in the saddle, the reins firmly gripped. The Prince, a sudden trembling thrilling through him, stood with his four feet planted. The girl leaned forward and whipped the blind from his red-rimmed eyes.

"There's a good boy!" said Judith coolly. "Buck a little for the lady, Prince!"

Slowly the great muscles of Prince's leg and shoulder and flank corded. The trembling passed; he was like a horse carven in bluish granite. He shook his head a little. Judith, her hand tightening upon the reins, held his head well up, the severe bit thwarting the attempt to get his nose down between his forelegs.

Then suddenly, without sign of warning, the horse whirled, leaping far out to the left, striking with hard hoofs bunched, gathering himself as he landed, swerving with the quickness of light, plunging again to the right. And again he stood still. Judith, sitting securely on his rebellious back, laughed. Her laughter, cool and unafraid, sent a strange little thrill through Bud Lee—who, with fear in his heart, was watching her.

"Look out for him now!" he called warningly.

In truth the Prince had not yet begun. He had tried a trick which would have unseated any but one who rode well. He knew that he had to do with something more than a rank amateur.

Now he plunged toward the corral, his purpose plain, the one desire in his heart to crush his rider against the high fence. But Judith's spurs answered him, and the bit, savage in his jaws, brought him about, whirling, sidling, striking, bucking as only a strong, fearless, devil-hearted horse knows how to buck. He doubled up under her; he rose and fell in a quick series of short jumps which tore and jerked at her body, which strove to tear her knees away from his sides and break the grip of her hand on the reins. But it seemed to the men watching that the girl knew before the horse which way he would jump, that she knew how to sway her body with his so that she and he were not two separate beings but just one, moving together in some mad devil's dance. The Prince, in the midst of the vicious bucking, tried to rear, seeking to throw himself backward; a quick, sharp blow of a loaded quirt between his ears brought his forefeet back to earth.

"Can she ride!" whispered Bud Lee. "I want to know!"

Again the maddened Prince reared and again she brought him to earth. Again he resumed the terribly tearing series of short, sharp bucks. And still, her hair tumbling, blown about her shoulders, she rode him.

Old Carson was muttering and pulling at his lip nervously. Out of the corner of his mouth in a voice that was almost a whimper, he kept cursing and saying to Ward Hannon: "You skunk! You ornery skunk! Hunt your hole after this!"

Suddenly, with a quick, concerted action of spur, whip, and rein, Judith swung the Prince about so that he was headed for the open valley, running toward the west, giving him his head only a little, driving him. He broke into a thundering run, snorting as, with mane and tail flying, he dashed through the men who fell away from his furious rush. And as he ran, Judith spurred him so that his only thought lay in running away from the menace upon his back.

"She ain't giving him time to buck!" laughed old Carson hysterically. "Mama! Ain't she sure enough—God! She's goin' to get a fall."

For horse and rider had come to the wide irrigating ditch which, since Judith Sanford had lived here, had been constructed to carry the water of Blue Lake River down to the alfalfa-fields. She saw it when she was too close to swerve.

The men watching saw her lean forward in the saddle, gather her reins, lift her whip. Then the lifted whip came down, the spurs touched the Prince's sweating sides, the big horse leaped far and clear of the ditch and there floated back Judith's laughter.

Three minutes later she rode back to the bunkhouse and slipped from the saddle. Bud Lee, going to her, had his hat in his hand.

"Now, Ward," she said quickly, her breathing hurried, her cheeks red, "what do you say?"

"I said I'd stick if you rode him," muttered Ward. "And——"

"And," cried the girl with quick passion, "I'll tell you something. You're a great big lumbering coward! Stick with me?" She laughed again, a new laugh, ringing with her scorn. "Here's your outlaw; I've gentled him a bit. You ride him!"

His fellows laughed at Ward; for the field foreman was no horseman and the timorous way in which he had brought out this snapping, vicious animal had testified to the fact. He drew back now, muttering.

"Ride him!" cried Judith, her voice stinging him. "Ride him or get off the ranch! Which is it?"

Ward Hannon, glad of the opening, answered surlily: "Aw! think I want to take orders off'n a woman? You're right, I'll get off'n the ranch!"

"That's two down," said Judith. "Now, take this horse back to the stable; I'm going up to the office. You men come there in five minutes. If you want to stay, and are worth your salt, you can. Or I'll give you your time. It's up to you: it's a free country. But—" and she said it slowly, confronting them—"if you all throw me down and leave me short-handed without giving me time to take on another set of men, you are a pretty low-lived bunch!"

Then, without turning, she went swiftly to the ranch-house. Old man Carson wiped the sweat from his forehead.

"I remember hearing about Luke Sanford's girl," he said simply. "This is her, all right."

"OLD MAN" CARSON—so-called through lack of courtesy and because of the sprinkling of gray through his black hair, a man of perhaps forty-five—filled an unthinkably disreputable pipe with his own conception of "real tobacca" and chuckled so that the second match was required; before he was ready to say his say.

"You just listen to me, you boys!" he said. "I worked with the Down River outfit a year before Trevors sent me word he had a job open here at better pay. That's only seventy-five miles, and news does percolate, give it time. None of you fellers ever saw old Luke Sanford?"

"I'd been working here close to two weeks when he got killed," Bud said as Carson's twinkling eyes went from face to face. "I got my job straight from him, not Trevors."

"That's so," said Carson. "Well, Bud knows the sort Luke Sanford was. He was dead and buried when I come to the Blue Lake, but I'd saw him twice and I'd heard of him more times than that. Quiet man that 'tended to his own business and didn't say so all- fired much 'less he was stirred up. And then—!" He whistled his meaning. "A fighter. All he ever got he fought for. All he ever held on to he fought for. He bucked Western Lumber for a dozen years, first and last. And, by cripes, he nailed their durned hides on his stable-door, too!

"Well, I heard tell about this same Luke Sanford ten years ago and more—about him and his little girl. From what folks said I guess there never was a man wanted a boy-baby worse'n Luke Sanford before Judith come. And I guess there never was a man put more stock in his own flesh and blood than Luke did in her as soon as he got used to her being a she. I don't know just exactly how old she was ten years ago, women folks being so damn' tricky in the looks of their ages, but I'd say she was eight or nine or ten or eleven years old. Anyhow, Luke had took her in hand already."

"Taught her to ride, huh?" asked one of the men.

"You're shouting, Poker Face," nodded Carson with vehemence. "He sure did! Why, that girl's rid real horses since she was the size of a pair of boots. Luke took her everywhere he went, up in the mountains, over the Big Ridge, down valley-ways, into town when he went off on his yearly. And they say Luke wasn't no poky rider, either. You've rode his string, Bud? What are those for horses, huh?"

"I'm a little particular when it comes to a saddle-horse," Bud admitted. "But I never asked any better than old Sanford's string."

"You hear him!" said Carson. "Well, that Judy girl has rid horses like them for a dozen years. And her dad—anyway, folks say so down on the river—showed her his way to ride and his way to shoot and his way to play cards! I guess," and he spoke with slow thoughtfulness, "that she's a real chip off'n the old block. It's my guess number two that she ain't just shooting off her face promiscuous when she says there's something crooked in the deal Trevors has been handing her. And, third bet, there's most likely going to be seven kinds of hell popping around this end of the woods for a spell."

"What are you doing about it, Carson?" asked the man whose unusually vacuous expression gave him his name of Poker Face. "Stick on the job or quit?"

"Me?" Carson sought a match, and when he had found it, held it long in his grimy fingers, staring at it thoughtfully. "Me stay an' let a she-girl boss me? Well, it ain't the play a man might look to me to make, an' I ain't saying it's the trick I'd do every day in the week. But here there's some things to set a man scratching his head: she's a winner, all right, an' I'm the first man to up an' say so. She's got the sand an' she's got the savvy. Take 'em together an' they make what you call gumption. Sure it ain't no woman's job to step in an' run an outfit like this one; a woman ain't nacherally cut out for that sort of thing any more'n a man is to darn socks an' drink tea with lemon in it. Again, tipping it over so's you can look at the other side, like a fair man ought to, what's she going to do? She lands here sudden, striking all four feet in a mess of trouble. She grabs holt of things, seeing they belong to her in a way, an' seeing she's fed Trevors his time. I might go trailing my luck some other-where, if I did the first fool thing that plopped into my nut. But playing fair, I'm going to stick an' do my damnedest to see Luke Sanford's girl put up her scrap. Yes, sir."

"What did she want to fire Trevors for?" asked Benny, the cook.

Carson, looking at him contemptuously, spoke in contemptuous answer about the stem of his pipe. "Any man on the job can answer you that, Cookie. It's been open an' shut the last month Trevors is either crazy or crooked. I said, didn't I, Western Lumber's itching to get its devil-fish legs wropped aroun' Blue Lake timber? They've busted more than one rancher up in the mountains. Trevors is in with 'em. Any man on the ranch that don't know that, don't want to know it!" He removed his pipe at last, and his look upon Benny was full of meaning. "Roll that in your dough, Cookie, an' make biscuits out'n it."

"Go easy there, grandfather," growled Benny.

"That's something I ain't learned," was old Carson's ready answer, lightly given. "I've told you before, if you don't want your name printed plain don't come around asking me to spell it."

Benny growled an answer but did not take up the quarrel. He knew Carson well enough to know that there was no man living readier for a fight or abler to conduct his own part of it. Carson, smaller than Benny, was wiry, quick-footed, hard-eyed. There was something about him that caused a man of Benny's sort to stop and think.

"Qué hay, Bud?" called a voice, and old José, his

face shining with his joy—Bud was certain that Judith had

actually kissed the leathery cheek and wondered how she could do

it!—came down the knoll. "La señorita wants

you!"

"Haw!" gurgled Bandy O'Neil facetiously. "It's your manly beauty, Bud! You ol' son-of-a-gun of a lady-killer!"

Bud Lee swung about upon his heel to glare at Bandy. But suddenly conscious of a flush creeping up hotly under his tan, he turned his back and strode away to the house. Bandy's "haw, haw!" followed him. Lee's face was flaming when he entered the office.

"What do you want with me?" he said shortly, angered at Bandy, Judith Sanford and himself.

"Bow, wow!" retorted Judith, looking up from Trevors's table. "Whose dog art thou? Do you want me to think you are as fierce as you look?"

"You sent for me?" he said coolly.

She looked up at him critically. "What's come over you, Lee? I took you for a cool head—Heaven knows I need a few cool heads around me right now!—and here you show up with red in your eye, barking at me."

"Let's pass up what I look like," said Lee stiffly. "What can I do for you. Miss Sanford?"

"Hm," said Judith. "On your high horse, are you? All right, stay there. What I want is some information. How long have you been on the Blue Lake pay-roll?"

"A little over six months," he answered colorlessly.

"Over six months?" A quick look of interest came into her eyes. "Trevors hired you? Or dad?"

"Your father."

"Then"—and a sudden, swift smile came for the first time that morning into the girl's eyes—"you're square! Thank God for one man to be sure of."

She had risen with a quick impetuosity and put out her hand. Lee took it into his own, and felt it shut hard, like a man's.

"Just how do you know I'm square?" he asked slowly.

"Dad was human," she replied softly. "He made some mistakes. But he never made a mistake in a horse foreman yet. He has said to me a dozen times: 'Judy, watch the way a man treats his horse if you want to size him up! And never put your horses into the care of a man who isn't white, clean through.' Dad knew, Bud Lee!"

Lee made no answer. For a little Judith, back at the long table and looking strangely small in the big, bare room before this massive piece of furniture, stared into vacancy with reminiscent eyes. Then, with a little shrug of her shoulders, she turned again to the tall foreman.

"Why did you tell Trevors this morning that you were going to quit work?" she asked with abrupt directness.

"Because," he answered, and by now his flush had subsided and his grave good-humor had come back to him with his customary serenity, "I felt like moving on."

"Because," she insisted, "you know that there was some dirty work afoot and did not care to be messed up in it?"

Now here, most positively, Bud Lee said within himself, was a person to reckon with. How did she know all that? She was just a girl, somewhere, as old Carson put it, between eighteen and twenty-two. What business did a kid like this have knowing so blamed much?

"You've got your rope on the right pair of horns," he said after his brief pause.

"How did you know that Trevors was working the double-cross on this deal?" she demanded.

"I didn't know," he said stiffly. "I just guessed. The same as you. He was spending too much money; he was getting too little to show for it; he was selling too much stock too cheap."

"What's the matter with you?" cried the girl, surprising him with the heat of her words and the sudden darkening of her eyes. "Why do you insist on being so downright stand-offish and stiff and aloof? What have I done to you that you can't be decent? Here I am only putting foot on my own land and you make me feel like an intruder."

"I am answering your questions."

"Like a half-animated trained iceberg, yes. Can't you act like a human being? Oh, I've got your number, Bud Lee, and you are just as narrow between the horns as the rest of the outfit. You are narrow and prejudiced and blindly unreasonable! I know as much about ranching as any man of you; I know more about this outfit because the best man that ever set foot on it, and that's Luke Sanford, taught me every crook, and bend of it; and now, just because I'm a girl and not a boy, you stand off like I had the smallpox; just when I need loyalty and understanding and when, the Lord knows, I've already got a double handful of trouble, I can't count for a minute on men that have been taking my pay for months! Get some of the mildew and cobwebs out of your head and tell me this: What reason in the world is there why you choose to think I haven't any business wearing my own shoes?"

"That's sure putting it straight," said Lee slowly.

"You just bet it's putting it straight!" she announced vigorously. "And you'll find that it's a way I have, putting things straight. I was trained to the business by a better man than you'll ever be, Bud Lee."

"Maybe so," he admitted without heat. "I'll take off my hat to Luke Sanford for a man. And I'll take off my hat to you, if you want to know. But, training or no training, this is no job for a lady, and shooting up Trevors and riding the Prince isn't going to make it so. Sure enough it's none of my butt-in what sort of thing you do. But at the same time there's no call for me to say you're doing fine when I don't see it that way."

"What you're looking for," sniffed Judith contemptuously, "is a female being extinct this one hundred years! You'd have every girl wear tails to her gowns, and duck and dodge behind fans and faint every time she jabbed her thumb with a pin!"

"I can't see that a woman's place is riding bucking broncos and rampsing around...."

"A woman's place!" she scoffed. "Her place where a blunder- headed man puts her! How do you know what her place is? Do you suppose the blood in a healthy-bodied, healthy-minded woman is any different from your blood? How would you like to be told just what your place is? To be jammed, for instance, into a little bungalow in a city; to be squeezed into a dress-suit and told 'Stay there and look sweet'; to be commanded not to get up a natural sweat, nor to kick over the traces with which some woman had hitched you to the cart of convention. How'd you like it, Bud Lee?"

Bud Lee grinned and a new look crept into his eyes. "Being Bud Lee," he answered frankly, "I wouldn't stand it for one little tick of the clock! If you want me to swap talk with you; all day at ninety bucks a month, all right. I'd say there's two kinds of men, too. There's my kind; there's the Dave Burril Lee kind. You see, he's a sort of relation of mine, is Dave Burril Lee, and I'm not exactly proud of him. He's the kind that wears dress-suits and sticks in a bungalow. He's proud of his name Burril and Lee, both, because big men down South wore 'em before he did, and they were relations. He's swelled up over the way he can dance and ride after a fox, and over the coin he's got in the bank. Then there's Bud Lee who ducks out of that sort of a scrap-heap and beats it for the open."

"I get you!" broke in Judith, her eyes very bright. "And you men here, my men, want me to be the sort of woman that your precious cousin, Dave Burril, is a man? Is that it? Where's your logic this morning?"

"Meaning horse sense?" he smiled. "It's in these few little words: 'What's right for a man may be dead wrong for a woman.'"

"Oh, scat!" she cried impatiently. "What am I wasting time with you for? You're right when you say that if I am paying you ninety dollars a month and grub and blankets I'd better get something out of you besides talk." She swung back to her table. "What was Trevors's latest excuse for selling at a sacrifice?" she asked, her tone dry and businesslike. "Why was he selling those horses at fifty dollars a head?"

"Told me he just had a wire last night from Young Hampton, asking for three thousand," he explained in a similar tone, though his eyes were twinkling at her.

"Pollock Hampton has his nerve!" she snapped. She took up the telephone instrument at her elbow and demanded the Western Union at Rocky Bend. "Judith Sanford speaking," she said crisply. "Repeat the message of last night for the general manager, Blue Lake Ranch."

In a moment she had it. "So Trevors wasn't lying about that part of it," she said reluctantly. And to the Western Union agent, "Take this message:

POLLOCK HAMPTON, HOTEL GLENNLYN, SAN FRANCISCO:

IMPOSSIBLE SEND MONEY NOW OR FOR SOME TIME. HAVE FIRED TREVORS. RUNNING OUTFIT MYSELF. NEED EVERY CENT WE CAN RAISE TO PAY INTEREST ON LOANS, MEN'S SALARIES AND KEEP GOING. THIS IS FINAL.

JUDITH SANFORD, GENERAL MANAGER.

"That may start his gray matter working," she ended as she clicked up the receiver. "Now, Lee, will you stick with me ten days or so and give me time to get a man in your place?"

"Yes, I'll do that, Miss Sanford."

"You will help me in every way you can while you are with me?"

"When I work for a man—or a woman," he added gravely, "I don't hold back anything."

"All right. Then start in right now and tell me about the gang Trevors has taken on. Are they all crooks?"

"I wouldn't say so. I wouldn't put it that strong."

"That little gray, quick-spoken man with the smelly pipe—he's straight, isn't he?"

"That would be old Carson? Yes; he's a good man. You won't find a better."

"Is he going to quit, too? Just because I've come?"

Lee shook his head. "If you work him right Carson will stick right along. Being white clean through, being broader-minded than I am"—and the twinkle came again into his eyes—"Carson'll show you a square deal."

"Has he any love for Bayne Trevors?"

"Maybe you'd better ask Carson."

In a flash she was on her feet and had gone to the door. "Carson!" she called loudly. "Come here, will you?"

There was a little silence, a low sound of laughter, then Carson's sharp voice answering: "I'm coming!"

Judith went back to her chair. She did not speak until Carson's wiry form slipped through the doorway. Then with the old cattleman's shrewd, hard eyes upon her she turned from a clip full of papers she had been looking through and spoke to him quietly:

"You used to work for the Granite Canyon crowd, didn't you, Carson?"

"Yes'm," he answered.

"Cattle foreman there for several years?"

"Yes'm."

"Helped clean out the Roaring Creek gang didn't you, Carson?"

Carson shifted a bit, colored under her fixed eyes, and finally admitted:

"Yes'm."

"Haven't had a real first-class fight for quite a bit, have you, Carson? Not since that gash on your jaw healed? Not since you and Scotty Webb mixed with the Roaring Creekers?"

Carson rubbed his jaw, flashed a quick look at Bud Lee as though for moral support, looked still further embarrassed, and finally choked over his brief:

"No'm."

Judith sat smiling brightly up at his hard features. "I've heard dad talk about that," she said thoughtfully. "I guess I've got at least one real man on the ranch, Carson. Oh, don't dodge like that! I'm not going to put my arms around you and kiss you on the top of your head. But I do love a man that loves a fair fight.... Lee, here, has given me his promise to stick on the job for ten days or so, to give me time to get some one else to look after my horses."

"Yes'm," said Carson, fingering his pipe and looking down.

For a few moments the girl sat still, now and then flashing a quick, keen look from one to the other of her two foremen. Then, abruptly, her eyes on Carson, she snapped: "You've found out, more or less recently, haven't you, that Bayne Trevors is a crook? You've perhaps even guessed that he's been taking money from me with one hand and from the Western Lumber with the other?"

"Yes'm," said Carson. "I doped it up like that."

"Why," cried the girl, "he's fired all of the old men and Heaven knows how many of his sort he's put in their places! Help me clean 'em out, Carson! Where will we begin? I've chucked Trevors and Ward Hannon. Who goes next, Carson?"

"Benny the cook," said Carson gently. "An' I'd be obliged, ma'am, if you'd let me go boot him off'n the ranch."

"That's talking," she said enthusiastically. "You can attend to him. Any one else?"

Carson shook his head. "I got my suspicions," he said. "But that's all I'm dead sure on."

"The others can wait then. Now, I'm taking a gamble on you and Lee. You have all kinds of chances to double-cross me. But I've got to take a chance now and then. I'm going to tell you something: Trevors is trying to sell me out to the Western Lumber people. He is one of their crowd and has been since they bought him up six months ago. They want our timber tract over the north ridge but they don't think they will have to pay the price. They want the lake; they want the water-power of Blue Lake River! They want pretty well all we've got. The ranch outside the stock we've got running on it, is worth a clean million dollars if it is worth a nickel. Well, the Western Lumber Company has offered us exactly two hundred and fifty thousand! Only quarter of what it's worth! They know we're mortgaged; they know the interest we have to pay is heavy; they know Pollock Hampton, for one, is a spender who knows nothing about big business; they think that I, because I'm a girl, am a fool. It looks to them like a melon easy to cut and ripe for the slicing."

She paused a moment, frowning thoughtfully at the floor. Then suddenly she lifted her eyes to Carson's, saying crisply: "Trevors took time at the end to tell me something. That something was that he was going to make me sell. He was excited a bit, I'll admit, or he wouldn't have spoken quite so plainly. And he counted upon the fact of my sex, of course, to feel confident that he could throw a scare into me. He even threatened, if I hadn't come to my senses before the ranch was dry in the summer, to burn me out!"

Carson blinked at her. "How's that?" he asked.

She told him again, coolly indifferent, it seemed to Carson.

"The durned polecat!" whispered the cattle foreman.

"Now then," cried Judith, "you've got your first job cut out for you. Let Bayne Trevors or one of his gang set foot on Blue Lake land, and I'll tell you what I think of you, Carson! Or is the job going to be too big for you?"

Carson smiled deprecatingly. "I'd like to see 'em try it," he said in that soft, whispering voice which upon occasions was characteristic of him. "I sure would, Miss Judy!"

"That's all this morning, Carson," she said quietly. "On your way don't forget to look in on your friend Benny."

Carson went hastily down the knoll, his eyes bright. Judith laughed softly.

"I've got his number, Bud Lee! All that's needed to keep that old mountain-lion on the job is to show him a real fight ahead! And by golly, Mr. Man, there's going to be scrap enough from the very jump to make Carson forget whether he's working for a woman or John W. Satan, Esquire!"

"AND now," said Judith Sanford to the stillness about her—she was alone in the big ranch-house—"not being constructed of iron, I'm going to take a snooze."

She yawned, stretched her supple young body luxuriously, and passed slowly through the empty rooms which, at her command, José had opened to the sweet morning air. Through the great living- room, library, and music-room, where the grand piano stood dejectedly in its mantle of dust, she came to her own chambers at the southwest corner of the building. Her bed was made, the sheets clean and fresh and inviting, dressing-gown and slippers were upon the window-seat, and from her table a vase of glorious roses sent out a welcoming perfume.

"Good old José," she smiled.

Vivid blossom that she was upon the tough, hardy stalk of her pioneer ancestry, creature of ardent flame and passion which her blood and her life in the open had made her, she was not devoid of the understanding of the limit of physical endurance. Last night, through the late moonlight and later starlight, through the thick darkness which lay across the mountain trails before the coming of day, on into the dawn, she had ridden the forty miles from the railroad at Rocky Bend. Certain of treachery on the part of Bayne Trevors, she had arrived only to find him plotting another blow at her interests. She had ridden a mad brute of a horse whose rebellious struggle against her authority had taxed her to the last ounce of her strength. She had shot a man in the right shoulder and the left forearm.... And now, with no one to see her, she was pale and shaking a little, suddenly faint from the heavy beating of her own heart. She had had virtually no sleep last night. She was glad of it. For now she would sleep, sleep.

"I am not to be called, no matter what happens," she said to José who came trotting to the tinkle of her bell. "Thank you for the roses, José."

Slipping out of her clothes, she drew the sheet up to her throat—and tossed for a wretched hour before sleep came to her. A restless sleep, filled with broken bits of unpleasant dreams.

At two o'clock, swiftly dressing after a leisurely bath, she went out into the courtyard, where she found José making a pretense of gardening, whereas in truth for a matter of hours he had done little but watch for her coming.

"José," she said, as he swept off his wide hat and made her the bow reserved for la señorita and la señorita alone, "you will have to be lady's maid and errand-boy for me until I get things running right. I am going to telephone into town this minute for a woman to do my cooking and housekeeping and be a nuisance around generally. While I do that, will you scare up something for me to eat and then saddle a horse for me? And don't make a fire, either; just something cold out of a can, you know."

She went to the office, arranged over the wire with Mrs. Simpson of Rocky Bend to come out on the following day, and then spent fifteen minutes studying the pay-roll taken from the safe, which, fortunately, Trevors had left open. As José came in with a big tray she was running through a file of reports made at the month-end, two weeks ago, by certain of the ranch foremen.

"Put it down on the table, José. Thank you," and she found time for a smile at her devoted servitor; "Now, have a horse ready, will you?" And without waiting for José's answer, taking up the telephone, she asked for the office at the Lower End, as the rich valley land of the western portion of the ranch was commonly known.

Briefly making herself known to the owner of the boyish voice which answered, she asked, for "Doc" Tripp and was informed that the ranch veterinarian was no longer with the outfit. Judith frowned.

"Where is he?"

"Rocky Bend, I think."

"When did he leave us?"

"Three days ago."

"Why?"

"Fired. Mr. Trevors let him go."

"Hm!" said Judith. "Who has taken his place?"

"Bill Crowdy is sort of acting vet, right now."

"Thanks," she said. Clicking off, she put in a call for "Doc" Tripp in Rocky Bend. "Get him for me as quick as you can, will you, please?" she asked of the operator in town.

For five minutes she munched at a sandwich and pored over the papers before her, dealing with this or that of the many interests of the big ranch. When at last her telephone-bell rang she found that it was Tripp.

"Hello, Doc," she said cordially. "I haven't seen you for so long I almost have forgotten how you comb your hair!" Tripp laughed with her at that; across the miles she could picture him running his big hand through the rebellious shock. "Yes, I'm back to stay, and from the looks of it I didn't come any too soon. Yes, Doc, we do miss him," and her voice softened wonderfully to Tripp's mention of the man who had been more than father to her, more than friend to him. "But we are going to buck up and show folks that he knew. He would have made a go of the thing; we are going to do it. What was the trouble with you and Trevors?"

Tripp explained succinctly. He and the general manager had disagreed openly and frequently about that part of the work in which, until the coming of Trevors, the veterinarian had been entirely unhampered. Two months ago Trevors had reduced Tripp's wages and had threatened another cut.

"Just to make me quit, you know," he added. "And I would have quit if it had been any other outfit in the world."

"I know," she said, and she did understand. "Go on. What was the excuse for canning you?"

"Case of lung-worms," he told her. "Some of the calves, I don't know just how many yet. He insisted on my treating them the old way."

"Slaked lime? Or sulphur fumes?" she said quickly. "And you insisted on chloroform?"

"You've hit it!" he exclaimed wonderingly. "How'd you know?"

"I haven't been loafing on the job the last six months," she laughed. "I've been at the school at Davis and hobnobbing with some of the university men at Berkeley. They're doing some great work there. Doc, I'll want to talk to you about it. You're going down there, expenses paid, to brush up with a course or two this year. Now, how soon can you get back here?—Trevors? Oh, Trevors is fired. I'm running the ranch myself. And, Doc, I need a few men like you! Can you come early to-morrow?—To- night? You're a God-blessed brick! Yes, I'll stop that murderous sulphur treatment if it isn't too late. Good-by."

She lost no time in calling for Bill Crowdy, the man whom Trevors had put into Tripp's place.

"By the way," she said when the man with the voice which had sounded so boyish in her ears answered again, "who are you?"

"Ed Masters," he told her. "Electrician, you know."

A glance at the pay-roll in front of her showed that Edward Masters, general electrician, was a new man and was drawing eighty-five dollars monthly.

"What are you doing this afternoon?" she demanded sharply—"just hanging around the office? Is that the way you earn your eighty-five dollars?"

"Not always. But Trevors told me to be on hand to-day to take some orders."

"What work?"

"Don't know," he said frankly. "He didn't say."

"Well," said Judith, "I'll tell you one thing, Ed Masters. If you are one of the loaf-around kind you'd better call for your time to-night. If there's anything for you to do, go do it. Don't wait for Trevors. He's gone. Yes, for good. You can report to me here the first thing in the morning. Now send me Crowdy."

"He's down in the hospital and the hospital phone is out of order."

"And you're an electrician, hanging around for orders! That's your first job. Send the first man you can get your hands on to tell Crowdy I say not to touch one of those calves with the lung- worm. And not to do anything else but get ready to talk with me. I'll be down in half an hour."

She clicked up the receiver, drank a cup of lukewarm coffee, noting subconsciously that José must have had a fire ready against the time of her awakening, and again consulted the files before her. Then again she used the telephone, ringing the Lower End office. This time it was another voice answering her.

"Where's Masters?" she asked.

"Gone down to the cow hospital," was the answer.

"Where's Johnson, the irrigation foreman?"

"Out in the south fields."

"And Dennings?"

"Went to look the olives over."

"Send out for both of them. I'm coming right down as fast as a horse will carry me and I want to talk with them. Wait a minute—I'll tell you when I'm through with you. Who are you, anyway?"

"Williams, the ranch carpenter."

"What are you doing to-day? Repairs needed at the office where you are?"

"No. You see——"

"You bet I see!" she cried warmly. "The first thing I see is that I've got more men on this job than I need. If there's no work for you to do, call tonight for your time. If you've got anything to do, go do it."

She clicked off again, waited a brief second and rang three for the dairy. After she had rung several times and got no answer, she murmured to herself:

"There's some one too busy on the ranch to be just hanging round after all, it seems."

And she went out to José and the waiting horse.

As she rode the five miles down to the office at the Lower End, her thoughts were constantly charged with an appreciation of the wonders which had been worked about her everywhere since that day, ten years ago, when she had first come with Luke Sanford to the original Blue Lake ranch. Then there had been only a wild cattle-range, ten thousand acres of brush, timber, and uncultivated open spaces. Nowhere would one find rougher, wilder stock-land in California. But Luke Sanford had seen possibilities and had bought the whole ten thousand acres, counting, from the first sight of it, upon acquiring as soon as might be those other thousands of acres which now made Blue Lake ranch one of the biggest of Western ventures.

It was late May, and the afternoon air was sweet and warm with the passing of spring. The girl's eager eyes travelled the length of the sky-seeking cliff almost at the back door of the ranch-house, which stood like some mighty barricade thrown up in that mythical day given over to the colossal struggle of a contending race of giants, and she found that there, alone, time had shown no change. Elsewhere, improvements at every turn were living monuments to the tireless brain of her father. Stock- corrals, sturdily built, out-houses spotless in their gleaming whitewash, monster barns, fenced-off fields, bridges across the narrow chasm of the frothing river, telephone-poles with their wires binding into one sheaf the numerous activities of the ranch, a broad, graded road over which she and her father had come here the last time together in the big touring-car.

Here the valley was only a mile across, shut in on both sides by cliff and steep, rocky mountain, walled by cliffs at the upper end, where the river from three-mile distant Blue Lake came down in flashing waterfalls.

But, as she rode, the valley widened, changed in character. At first, wandering herds of beef-cattle, with now and then a riding cowboy turning in his saddle to wonder at her; then a gate to be opened as she stooped forward from her own saddle, and wide fields where the grass stood tall and untrodden and blooded Jersey cows looked up in mild interest; yonder a small pasture in which were five Guernseys, kept in religious seclusion, under ideal conditions, to further certain investigations into the ratios of five different kinds of fodder to the amount of butter- fat produced; across a green meadow a pure-blooded Jersey bull, whose mellow bellowings drew Judith's eyes to the clean line of his perfect back, over which, with pawing hoofs, he was throwing much trampled earth; in a more distant pen, accepting the trumpeted challenge and challenging back, a beautiful specimen of careful breeding in Ayrshire.

The road wound on, following generally the line of the river, which began a generous broadening, flowing more evenly through level fields. Looking down the valley, Judith could see the whitewashed clump of buildings where were the second office, the store and the blacksmith's shop, the tiny cottages. And beyond, the barns, the dairy, the tall silos standing like lookout towers, the alfalfa-fields crisscrossed with irrigating ditches, and still farther on, the pasture-lands where the big herd of cows was grazing.

Here the valley was spread out until from side to side it measured something more than four miles. The bordering mountains, like the river, had grown into a softer mood; rolling hills scantily timbered, rich in grass, were dotted with herds, cattle and horses, or fenced off here and there, reserved for later pasturage.

Across the river, to the south, Judith marked the wandering calves, offspring of the herd; to the north, along the foothills, the subdued green of the olive-orchards.

"It's a big, big thing!" she whispered, and her eyes were very bright with it all, her cheeks flushed. "Big!"

Passing one of the great barns, she heard the trumpet call of a stallion and, turning, saw in the corral one of those glorious brutes which Bud Lee had spoken of to Trevors as "clean spirit." From the instant her eyes filled to the massive beauty of him, she knew who he was: Night Shade, sprung from the union of Mountain King and Black Empress; regal-blooded, ebon-black from silken fetlock to flowing mane; a splendid four-year-old destined to tread his proud way to a first prize at the coming State fair at Sacramento, a horse many stock-fanciers had coveted.

She stopped and marvelled afresh at him, paid him his due of unstinted admiration, and then spurred on to the little clump of buildings marking the lower ranch headquarters. At the store, where a ten-by-ten room was partitioned off to serve as office, she swung down from the saddle and, leaving her horse with dragging reins, went in.