RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

The Cavalier, 1 November 1913, with first part of "Under Handicap"

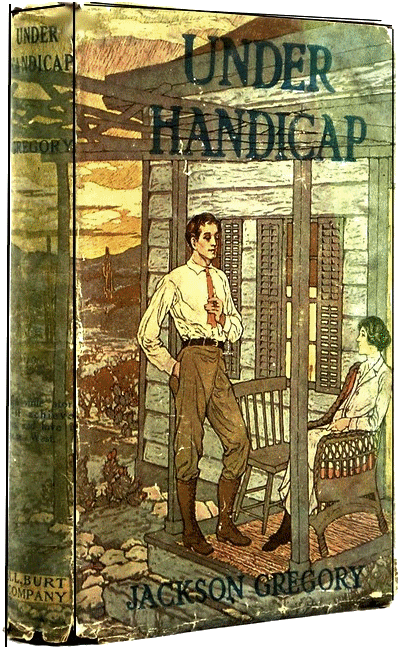

"Under Handicap," A.L. Burt Company, New York, 1914

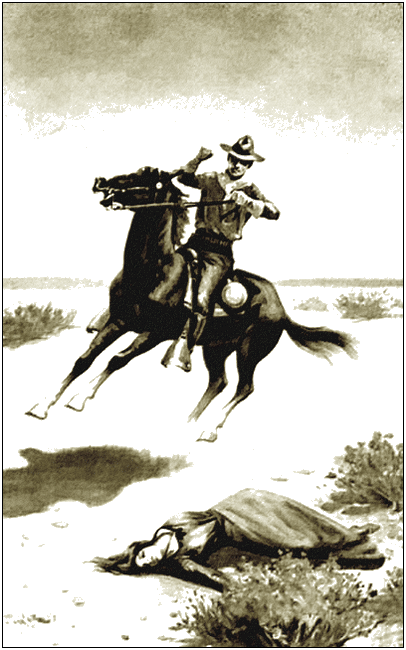

Conniston had seen her first, a huddled heap, almost at his feet.

OUTSIDE there was shimmering heat and dry, thirsty sand, miles upon miles of it flashing by in a gray, barren blur. A flat, arid, monotonous land, vast, threatening, waterless, treeless. Its immensity awed, its bleakness depressed. Man's work here seemed but to accentuate the puny insignificance of man. Man had come upon the desert and had gone, leaving only a line of telegraph-poles with their glistening wires, two gleaming parallel rails of burning steel to mark his passing.

The thundering Overland Limited, rushing onward like a frightened thing, screamed its terror over the desert whose majesty did not even permit of its catching up the shriek of the panting engine to fling it back in echoes. The desert ignored, and before and behind the onrushing train the deep serenity of the waste places was undisturbed.

Within the train the desert was nothing. Man's work defied the heat and the sand and the sullen frown outside. Here in the Pullman smoking-car were luxury, comfort, and companionship. Behind drawn shades were the whir of electric fans, an ebon-faced porter in snowy linen, the clink of ice in long, misted glasses, the cool fragrance of crushed mint. Even the fat man in shirt- sleeves reading the Denver Times, alternately drawing upon his fat cigar and sipping the glass of beer at his elbow, was not distressing to look upon. The four men busy over their daily game of solo might have been at ease in their own club.

At one end of the long car two young men dawdled in languid comfort, their bodies sprawling loosely in two big, soft arm- chairs, a tray with a couple of half-emptied high-ball glasses upon the table between them. They had created an atmosphere of their own about them, an atmosphere constituted of the blue haze from cigarettes mingled with trivial talk. The immensity outside might have bored them, so their shade was drawn low. For a moment one of the two men lifted a corner of it. He peered out, only to drop it with a disgusted sigh and return to his high-ball.

He was slender, young, pale-eyed, pale-haired, white-handed, anemic-looking. He was patently of the sort which considers such a thing as carelessness in the matter of a crease in one's trousers a crime of crimes. His tie, adjusted with a precision which was a science, was of a pale lavender. His socks were silk and of the same color. His eyes were as near a pale lavender as they were near any color.

"The devilish stupid sameness of this country gets on a man's nerves." He put his disgust into drawling words. "Suppose it's like this all the way to 'Frisco?"

His companion, stretching his legs a bit farther under the table, made no answer.

"I said something then," the lavender young gentleman said, peevishly. "What's the matter with you, Greek?"

Greek took his arms down from the back of his chair where he had clasped his hands behind his head, and finished his own high- ball. Nature in the beginning of things for him had been more kind than to his petulant friend. He was scarcely more than a boy—twenty-five, perhaps, from the looks of him—but physically a big man. He might have weighed a hundred and eighty pounds, and he was maybe an inch over six feet. But evidently where nature had left off there had been nobody to go on save the tailor. His gray suit was faultlessly correct, his linen immaculate, his hose silken and of a brilliant, dazzling blue. His face was fine, even handsome, but indicating about as much purpose as did his faultlessly correct shoes. There was an extreme, unruffled good humor in his eyes and about his mouth, and with it all as much determination of character as is commonly put into the rosy face of a wax doll.

"Seeing that you have made the same remark seventeen times since breakfast," Greek replied, when he had set his empty glass back upon the tray, "I didn't know that an answer was needed."

"Well, it's so," the pale youth maintained, irritably.

Greek nodded wearily and selected a cigarette from a silver monogrammed case. The cigarettes themselves were monogrammed, each one bearing a delicately executed W. C. His companion reached out a shapely hand for the case, at the same time regarding his empty glass.

"Suppose we have another, eh?"

Again Greek nodded. The lavender young man reached the button, and a bell tinkled in the little buffet at the far end of the car. The negro lazily polishing a glass put it down, glanced at the indicator, and hastened to put glasses and bottles upon a tray.

"The same, suh?" he asked, coming to the table and addressing Greek.

It was the pale young man who assured him that it was to be the same, but it was Greek who threw a dollar bill upon the tray.

"Thank you, suh. Thank you." The negro bobbed as he made the proper change—and returned it to his own pocket.

Greek appeared not to have seen him or heard. He poured his own drink and shoved the bottles toward his friend, who helped himself with skilful celerity.

"Suppose the old gent will hold out long this time, Greek?" came the query, after a swallow of the whisky and seltzer, a shrewd look in the pale eyes.

Greek laughed carelessly.

"I guess we'll have time to see a good deal of San Francisco before he caves in. The old man put what he had to say in words of one syllable. But we won't worry about that until we get there."

"Did he shell out at all?"

"He didn't quite give me carte blanche," retorted Greek, grinning. "A ticket to ride as far as I wanted to, and five hundred in the long green. And it's going rather fast, Roger, my boy."

"And my tickets came out of the five hundred?"

Greek nodded.

"It's devilish the way my luck's gone lately," grumbled Roger. "I don't know when I can ever pay—"

Greek put up his hand swiftly.

"You don't pay at all," he said, emphatically. "This is my treat. It was mighty decent of you to drop everything and come along with me into this d——d exile. And," he finished, easily, "I'll have more money than I'll know what to do with when the old man gets soft-hearted again."

"He's d——d hard on you, Greek. He's got more—"

"Oh, I don't know." Greek laughed again. "He's a good sort, and we get along first rate together. Only he's got some infernally uncomfortable ideas about a man going to work and doing something for himself in this little old vale of tears. He shaves himself five times out of six, and I've seen him black his own boots!" He chuckled amusedly. "Just to show people he can, you know."

Roger shook his head and applied himself to his glass, failing to see the humor of the thing. And while the bigger man continued to muse with twinkling eyes over the idiosyncrasies of an enormously wealthy but at the same time enormously hard-headed father, with old-fashioned ideas of the dignity of labor, Roger sat frowning into his glass.

The silence, into which the click of the rails below had entered so persistently as to become a part of it rather than to disturb it, was broken at last by the clamorous screaming of the engine. The train was slackening its speed. Greek flipped up the shade and looked out.

"Another one of those toy villages," he called over his shoulder. "Who in the devil would want to get off here?"

Roger sank a trifle deeper into his chair, indicating no interest. The fat man had dropped his newspaper to the floor and was leaning out the window.

"Great country, ain't it?" he called to Greek.

"Yes, it certainly ain't! What gets me is, why do people live in a place like this? Are they all crazy?"

The train now was jerking and bumping to a standstill. Sixty yards away was a little, bluish-gray frame building, by far the most pretentious of the clutter of shacks, flaunting the legend, "Prairie City." Beyond the station was the to-be-expected general store and post-office. A bit farther on a saloon. Beyond that another, and then straggling at intervals a dozen rough, rambling, one-storied board houses. For miles in all directions the desert stretched dry and barren. The faces of women and children peered out of windows, the forms of roughly garbed men lounged in the doorways of the store and the saloons. All the denizens of Prairie City manifested a mild interest in the arrival of Number 1.

"I guess you called the turn," sputtered the fat man. "Here come the crazy folks now!"

A cloud of dust swirling higher and higher in the still air, the clatter of hoofs, and two horses swept around the farthest house, carrying their riders at breakneck speed into the one and only street. At first Greek took it to be a race, and then he thought it a runaway. As it was the first interesting incident since Grand Central Station had dropped out of sight four days ago, he craned his neck to watch.

The two riders were half-way down the street now, a tall bay forging steadily ahead of a little Mexican mustang until ten feet or more intervened between the two horses. The train jerked; the Wells Fargo man, with his truck alongside the express-car far ahead, yelled something to the man who had taken his packages aboard.

"The bay wins," grinned the fat man. "It looks—Gad! It's a woman!"

Greek saw that it was a woman in khaki riding-habit, and that the spurs she wore were gnawing into her horse's flanks. He began to take a sudden, stronger interest. He leaned farther out, hardly realizing that he had called to the conductor to hold the train a moment. For it was at last clear that these were not mad people, but merely a couple of the dwellers of the desert anxious to catch Number 1. But the conductor had waved his orders and was swinging upon the slowly moving steps. From the windows of the train a score of heads were thrust out, a score of voices raised in shouting encouragement. And down to the tracks the woman and the man behind her rushed, their horses' feet seeming never to touch the ground.

A bump, a jar, a jerk, and the Limited was drawing slowly away from the station. The woman was barely fifty yards away. As she lifted her head Greek saw her face for the first time. And, having seen her ride, he pursed his lips into a low whistle of amazement.

"Why, she's only a kid of a girl!" gasped the fat man. "And, say, ain't she sure a peach!"

Greek didn't answer. He was busy inwardly cursing the conductor for not waiting a second longer. For it was obvious to him that the girl was going to miss the train by hardly more than that.

But she had not given up. She had dropped her head again and was rushing straight toward the side of the string of cars. Greek held his breath, a swift alarm for her making his heart beat trippingly. He did not see how she could stop in time.

Again a clamor of voices from the heads thrust out of car windows, warning, calling, cheering. And then suddenly Greek sat back limply. The thing had been so impossible and in the end so amazingly simple.

Not ten feet away from the train she had drawn in her horse's reins, "setting up" the half-broken animal upon his four feet, bunched together so that with the momentum he had acquired he slid almost to the cars. As he stopped the girl swung lightly from the saddle and, seeming scarcely to have put foot upon the sandy soil, caught the hand-rail as the car came by and swung on to the lowest step. The man behind her caught up her horse's reins, whirled, sweeping his hat off to her, and turned back.

"Which is some riding, huh?" chuckled the fat man, his own head withdrawn as he reached for his beer-glass.

"What's the excitement?" Roger's interest had not been great enough to send him to the window.

"Some people trying to catch the train," Greek told him, shortly. For some reason, not clear to himself, he did not care to be more definite.

"I don't blame the poor devils. Think of waiting there until another came by!" Roger washed the dryness out of his mouth with a generous sip of his whisky and seltzer.

The fat man finished his glass of beer and rang for another. Greek sat gazing out over the wide wastes of the desert. He had never before been in a land like this. Now that more than two thousand miles lengthened out between him and New York, he had felt himself more than ever an exile. Heretofore he had given no thought to the people dwelling here beyond the last reaches of those things for which civilization stood to him. He was not in the habit of thinking deeply. That part of the day's work could be left to William Conniston, Senior, while William Conniston, Junior, more familiarly known to his intimates as "Greek" Conniston, found that he could dispense with thinking every bit as easily as he could spend the money which flowed into his pockets. But now, as unexpectedly as a flash from a dead fire, a girl's face had startled him, and he found himself almost thinking—wondering—

Conniston turned swiftly. The girl was passing down the long narrow hallway leading by the smoking-car, evidently seeking the observation-car. Through the windows he could see her shoulders and face as she walked by him. He could see that there was the same confidence in her carriage now that there had been when she had jerked her horse to a standstill and had thrown herself to the ground. Even Roger, turning idly, uttered an exclamation of surprised interest.

She was dressed in a plain, close-fitting riding-habit which hid nothing of the undulating grace of her active young body. In her hand she carried the riding-quirt and the spurs which she had not had time to leave behind. Her wide, soft gray hat was pushed back so that her face was unhidden. And as she walked by her eyes rested for a fleeting second upon the eyes of Greek Conniston.

Her cheeks were flushed rosily from her race, the warm, rich blood creeping up to the untanned whiteness of her brow. But he did not realize these details until she had gone by; not, in fact, until he began to think of her. For in that quick flash he saw only her eyes. And to this man who had known the prettiest women who drive on Fifth Avenue and dine at Sherry's and wear wonderful gowns to the Metropolitan these were different eyes. Their color was elusive, as elusive as the vague tints upon the desert as dusk drifts over it; like that calm tone of the desert resolved into a deep, unfathomable gray, wonderfully soft, transcendently serene. And through the indescribable color as through untroubled skies at dawn there shone the light which made her, in some way which he could not entirely grasp, different from the women he had known. He merely felt that their light was softly eloquent of frankness and health and cleanness. Their gaze was as steady and confident as her hand had been upon her horse's reins.

"She must have been born in this wilderness, raised in it!" he mused, when she had passed. "Her eyes are the eyes of a glorious young animal, bred to the freedom of outdoors, a part of the wild, untamable desert! And her manner is like the manner of a great lady born in a palace!"

"Hey, Greek," Roger was saying, his droning voice coming unpleasantly into the other's musings, "did you pipe that? Did you ever see anything like her?"

Conniston lighted a fresh cigarette and turned again to look out across the level gray miles. Ignoring his friend, Greek thought on, idly telling himself that the Dream Girl should be born out here, after all. Here she would have a soul; a soul as far-reaching, as infinite, as free from shackles of convention as the wide bigness of her cradle. And she would have eyes like that, drawing their very shade from the vague grayness which seemed to him to spread over everything.

"I say, Greek," Roger was insisting, sufficiently interested to sit up straight, his cigarette dangling from his lip, "that little country girl, dressed like a wild Indian, is pretty enough to be the belle of the season! What do you think?"

Conniston laughed carelessly.

"You're an impressionable young thing, Hapgood."

"Am I?" grunted Roger. "Just the same, I know a fine-looking woman when I clap my bright eyes on her. And I'd like to camp on her trail as long as the sun shines! Say"—his voice half losing its eternal drawl—"who do you suppose she is? Her old man might own about a million acres of this God-forsaken country. If she goes on through to 'Frisco—"

"You wouldn't be strong for stopping off out here?" the fat man put in genially. Hapgood shuddered.

And to Greek Conniston there came a sudden inspiration.

"Anyway," Roger Hapgood went on in his customary drawl, "I'm going to find out. It's little Roger to learn something about the prairie flower. I'll soon tell you who she is," he added, rising from his seat.

But he never did. For one thing, young Conniston was not there when Roger returned five minutes later, and it is extremely doubtful if Roger Hapgood would have told how his venture had fared. Being duly impressed with the fascination of his own debonair little person, and having the imagination of a cow, he had smirked his way to the girl, who now sat in the observation- car, and had begun on the weather.

"Dreadfully warm in this desert country, isn't it?" he said, with over-politeness and the smile which he knew to be irresistible.

The girl turned from gazing out the window, and her eyes met his, very clear and very much amused.

"Very warm," she smiled back at him. Even then he had a faint fear that she was not so much smiling as laughing. "The surprising thing is how well things keep, is it not?"

"Ah—yes," he murmured, not entirely confident, and still dropping into a chair at her side. "You mean—"

"How fresh some things keep!"

Roger Hapgood's pink little face went violently red.

"I say!" he began. "I didn't mean any offense. I thought—"

"Oh, that's all right," she laughed, gaily. "No offense whatever. Will you please open that window for me?"

His face became normally pink again as he hastened to throw up the window in front of her. His eyelid fluttered downward as he met the regard of a couple of men facing them. Then he came back to her side.

"Thank you," she smiled sweetly up at him. And she held out her hand.

He didn't know what she wanted to do that for, but had a confused idea that in the free and easy spirit of the West she was going to shake hands. The next thing which he realized clearly was that she had dropped a shining ten-cent piece into his palm.

"Oh, look here," he stammered, only to be interrupted by her voice, a gurgle of suppressed mirth in it.

"I'm sorry that that's all I have in change! And now, if you will hand me that magazine—I want to read!"

Roger Hapgood fumbled with the dime and dropped it. He swept up the magazine from a near-by chair and held it out to her. As he did so he caught a glimpse of the faces of the two men at whom he had winked so knowingly, heard one of them break into loud, hearty laughter. Dropping the magazine to her lap, the lavender young man, with what dignity he could command, marched back to the smoking-car.

A few minutes later Greek Conniston, returning to the smoking- car, found his friend pinching his smooth cheek thoughtfully and frowning out the window. He dropped into his chair, deep in thought. In the brief interval he had taken his resolution, plunging, as was his careless nature, after the first impulse. The girl had interested him; he did not yet realize how much. She came aboard the train without bag or baggage. Certainly she could not be going far. And he—it didn't matter in the least where he went. All that he had to do was to keep out of his father's way until the old man cooled down, and then to wire for money. His ticket read to San Francisco, but he had no desire to go there rather than to any other place. And he told himself that he had a sort of curiosity about this bleak, monotonous desert land.

An hour later the train ran into another little clutter of buildings and drew up, puffing, at the station. Conniston's eyes were alert, fixed upon the passageway from the observation-car rather than on the view from his window. Mail-bags were tossed on and off, a few packages handled by the Wells Fargo man, and the train pulled out. Conniston leaned back with a sigh.

"Roger," he said, at last, "I've got a proposition to make."

"Well?"

"Let's drop off at one of these dinky towns and see what it's like. I've a notion we might find something new."

"That's a real joke, I suppose?"

"Not at all," maintained Conniston. "I'm going to do it. Are you with me?"

Hapgood sat bolt upright.

"Are you crazy, man!" he cried, sharply.

Conniston shrugged. "Why not? You've never seen anything but city life and the summer-resort sort of thing any more than I have. It would be a lark."

"Excuse me! I guess I'm something of a fool for having chased clean across the continent, but I'm not the kind of fool that's going to pick a place like this sand-pile to drop off in!"

"All right, old man. Nobody's asking you to if you feel that way."

Hapgood waited as long as he could for Conniston to go on, and when there came no further information he asked, incredulously:

"You don't mean that, do you, Greek? You don't intend to stop off all alone out here in this rotten wilderness?"

"Yes, I do. If you won't stop with me."

"But how about me? What am I to do? Here I am—busted! What do you think I'm going to do?"

"You can go on to San Francisco if you like. You can have half of what I've got left—or you can drop off with me."

Hapgood argued and exploded and sulked by turns. In the end, seeing the futility of trying to reason with a man who only laughed, and seeing further the disadvantage of being cut off from his source of easy money, Roger gave in, growling. So when the train drew into Indian Creek that afternoon there were three people who got down from it.

INDIAN CREEK stood lonely and isolated in the flat, treeless, sun-smitten desert. Only in the south was the unbroken flatness relieved by a low-lying ridge of barren brown hills, their sides cut as by erosion into steep, stratified cliffs. Even these bleak hills looked to be twenty miles away, and were in reality fifty. Beyond them, softened and blurred by the distance, was a blue-gray line where the mountains were.

"Of all the wretched holes in the world!" fumed Hapgood.

But Conniston didn't hear him. The girl had stepped down from the train, and, without casting a glance behind her, walked swiftly across the wriggling thing which stood for a street in Indian Creek. There was a saloon with a long hitching-pole in front of it, to which a couple of saddle-horses were tied, and a buckboard with two fretting two-year-olds in dust-covered harness. A man, a swarthy half-breed, with hair and eyes and long, pointed mustaches of inky blackness, was on the seat, handling the jerking reins. He called a soft "Adios, compadre" to the man lounging in the doorway, and swung his colts out into the road, making a sweeping half-circle, bringing them to a restless halt, pawing and fighting their bits, at the girl's side. While with one brown hand he held them back, with the other he swept off his wide, black hat.

"How do, Mess!" he cried, softly, his teeth flashing a white greeting.

She answered him with a "Hello, Joe!" as she climbed to his side.

Joe loosened his reins a very little, called sharply to his horses, and in a whirlwind of dust the buckboard made an amazingly sharp turn and shot rattling down the road and out toward the mountains in the south.

"And now what?" grinned Hapgood, maliciously. "Even your country girl has gone!"

Greek Conniston gazed a moment after the flying buckboard, a vague, wavering, unreal thing, through the dust of its own making, and, hiding his disappointment under a shrug, turned to Hapgood.

"Now for a hotel somewhere, if the place has one. Come on, Roger. We're in for it now, so let's make the best of it."

Carrying his suit-case, he strode off toward the saloon, Roger following silently. The lanky, sunburned individual in the doorway watched their approach idly for a moment and then turned his lazy eyes to a cow and calf trudging past toward the watering-trough.

"Hello, friend!" called Conniston.

The lanky individual drew his eyes from the cow and calf, bestowed a long look and a fleeting nod upon the two strangers, and turned again toward the trough, little impressed, little interested in the Easterners.

"I say!" went on Conniston, brusquely. "Where'll a man get a room here?"

"Down to the hotel."

"So you do have a hotel? Where is it?"

The lazy individual ducked his head toward the east end of the street, cast a last look at the cow and calf, and, turning, went back into the saloon.

"Nice sort of people," grunted Hapgood.

Conniston laughed. "Buck up, Roger," he grinned, his own spurt of irritation lost in his enjoyment of Hapgood's greater bitterness. "It's different, anyhow, isn't it? Come on. Let's see what the hotel looks like."

The hotel was a saloon with a long bar at the front, a little room just off, containing a couple of tables covered with red oil-cloth. Beyond were half a dozen six-by-six rooms separated from one another by partitions rising to within two feet of the unceiled roof. The proprietor, busy with some local friends in the card-room, saw the two young men come in and yelled, lustily:

"Mary!"

Mary, a stout and comfortable-looking woman, appeared from the kitchen, wiping her hands upon her blue apron, and with a sharp glance at the newcomers bobbed her head at them and said, briefly, "Howdy."

Conniston took off his hat and came into the bar-room. Roger, with a careless glance at the woman, came in without taking off his hat and dropped into one of the rickety chairs against the wall. And there he sat until Conniston had negotiated for two rooms for the night. Then he got jerkily to his feet and stalked after his friend and their hostess to the back of the house. A moment later he and Conniston, left alone, sat upon their two beds and stared at each other through the doorway connecting their rooms. Conniston studied the bare floors, the bare walls of rough, unplaned twelve-inch boards set upright with cracks between them ranging from a quarter of an inch to an inch in width, and, rumpling up his hair, sat back and grinned into Hapgood's woebegone face. And Hapgood after the same examination and a sight of the rough beds covered with patchwork comforters, groaned aloud.

"Maybe it's funny," he muttered. "But if it is, I don't see it."

"What are you going to do about it?" chuckled Conniston. "You can't fling out and go to the rival hotel, because there isn't any! You can't sleep outdoors very well. And you can't catch a train until a train comes. Which, I believe, will be sometime to- morrow morning."

It was already late afternoon. That day Roger Hapgood got no farther than the bar-room at the front of the house. There he sat in one of the rickety chairs, brooding, sullen, and silent, smoking cigarettes, drinking high-balls, and cursing the whole God-forsaken West. And there Conniston left him.

In spite of his naturally buoyant spirits, in spite of the fact that he knew he had only to swing upon the next train which came through, Conniston felt suddenly depressed. The silence was a tangible thing almost, and he felt shut out from the world, lost to his kind, marooned upon a bleak, inhospitable island in an ocean of sand. The few men whom he met upon the sun-baked street eyed him with an indifference which was worse than actual hostility. When he spoke they nodded briefly and passed on. It was clear that if he looked upon them as aliens, they looked upon him as a being with whom and whose class they had nothing in common, no desire to have anything in common. For a moment his good nature died down before a flash of anger that these beings, with little, circumscribed existences, should feel and manifest toward him the same degree of contempt that he, a visitor from a higher plane of life, experienced toward them. But in Greek Conniston good humor was a habit, and it returned as he assured himself that what these desert-dwellers felt was worth only his amusement.

At the store he bought some tobacco for his pipe and engaged the storekeeper in trifling conversation. The talk was desultory and for the most part led nowhere. But the little, brown, wizened old man, contemplatively chewing his tobacco like a gentle cow ruminating over her cud, answered what scattering questions Conniston put to him. The young man learned that the town took its name from the stream which crept rather than ran through it to spread out on the thirsty sands a few miles to the north, where it was absorbed by them. That the creek came from the hills to the south, and from the mountains beyond them. When one crossed the brown hills he came to the Half Moon country and into a land of many wide-reaching cattle-ranges.

"I saw a team drive out that way after the train came in," said Conniston, carelessly. "Headed for one of the cattle-ranges, I suppose?"

The old man spat and nodded, wiping his scanty gray beard with his hand.

"That was Joe from the Half Moon. Took the ol' man's girl out."

"I did see a young lady with him. She lives out there?"

"Uh-uh." The old man got up to wait upon a customer, a cowboy, from the loose, shaggy black "chaps," the knotted neck handkerchief, the clanking spurs and heavy, black-handled Colt revolver at his hip. He bought large quantities of smoking- tobacco and brown cigarette-papers, "swapped the news" with the storekeeper, and clanked his way across to the saloon. He did not appear to have seen Conniston.

"The girl's father run a cattle-range out there?"

"Uh-uh. The Half Moon an' three or four smaller ranges. He's old man Crawford—p'r'aps you've heard on him?"

Conniston shook his head, suppressing a smile.

"I don't think I have. Far out to his place?"

"Oh, it ain't bad. Let's see. It's fifty mile to the hills, an' he's about forty mile fu'ther on." He stopped for a brief mental calculation. "That makes it about ninety mile, huh?"

"How does a man get out there? A narrow-gauge running from somewhere along the main line?"

"Darn narrow, stranger. You can walk if you're strong for that kind of exercise. Mos' folks rides. Goin' out?"

"It's rather a long walk," Conniston evaded. And shortly afterward, hearing a clanging bell up the street in the direction of the hotel, he strolled away to his dinner.

He found Hapgood scowling into his high-ball glass and dragged him away to the little dining-room. Both the tables were set. At one of them the cowboy whom he had seen at the store was already eating with two of his companions. Conniston and Hapgood were shown to the other table by the stout Mary. Hapgood cast one glance at the stew and coarse-looking bread put before him, and pushed his plate away. Conniston, who had had fewer high-balls and more fresh air, actually enjoyed his meal. The men at the other table glanced across at them once and seemed to take no further interest.

Hapgood waited, bored and conventional, until Conniston had finished, and then the two went back into the bar-room. The sun had gone down, leaving in the west flaring banners of brilliant, changing colors. The heat of the day had gone with the setting of the sun, a little lost, wandering breeze springing up and telling of the fresh coolness of the coming night. And it was still day, a day softened into a gray twilight which hung like a misty veil over the desert.

From the card-room came the voices of the proprietor and the men with whom he was still playing. They had not stopped for their supper, would not think of eating for hours to come.

"If you feel like excitement—" began Conniston, jerking his head in the direction of the card-room.

Hapgood interrupted shortly. "No, thanks. I've got a magazine in my suit-case. I suppose I'll sit up reading it until morning, for I certainly am not going to crawl into that cursed bed! And in the morning—"

"Well? In the morning?"

"Thank God there's a train due then!"

Conniston left him and went out into the twilight. He passed by the store, by the saloon, along the short, dusty street, and out into the dry fields beyond. He followed the road for perhaps a half-mile and then turned away to a little mound of earth rising gently from the flatness about it. And there he threw himself upon the ground and let his eyes wander to the south and the faint, dark line which showed him where the hills were being drawn into the embrace of the night shadows.

The utter loneliness of this barren world rested heavy upon his gregarious spirit. Sitting with his back to Indian Creek, he could see no moving, living thing in all the monotony of wide- reaching landscape. He was enjoying a new sensation, feeling vague, restless thoughts surge up within him which were so vague, so elusive as to be hardly grasped. At first it was only the loneliness, the isolation and desolation of the thing which appalled him. Then slowly into that feeling there entered something which was a kind of awe, almost an actual fear. A man, a man like young Greek Conniston, was a small matter out here; the desert a great, unmerciful, unrelenting God.

First loneliness, then awe tinged with a vague fear, and then something which Conniston had never felt before in his life. A great, deep admiration, a respect, a soul-troubling yearning toward the very thing from which his city-trained senses shrank. He was experiencing what the men who live upon its rim or deep in its heart are never free from feeling. For all men fear the desert; and when they know it they hate it, and even then the magic of it, brewed in the eternal stillness, falls upon them, and though they draw back and curse it, they love it! The desert calls, and he who hears must heed the call. It calls with a voice which talks to his soul. It calls with the dim lure of half- dreamed things. It beckons with the wavering streamers of gold and crimson light thrown across the low horizon at sunrise and sunset.

Greek Conniston was not an introspective man. His life, the life of a rich man's son, had left little room for self- examination of mood and purpose and character. He had done well enough during his four years in the university, not because he was ambitious, but simply because he was not a fool and found a mild satisfaction in passing his examinations. Nature had cast him in a generous physical mold, and he had aided nature on diamond and gridiron. He had taken his place in society, had driven his car and ridden his horses. He had through it all spent the money which came in a steady stream from the ample coffers of William Conniston, Senior. His had been a busy life, a life filled with dinners and dances and theaters and races. He had not had time to think. And certainly he had not had need to think.

But now, under the calm gaze of the desert, he found himself turning his thoughts inward. He had been driven out of his father's house. He had been called a dawdler and a trifler and a do-nothing. He had been told by a stern old man who was a man that he was a disgrace to his name. He had never done anything but dance and smoke and drink and make pretty speeches which were polite lies and which were accepted as such. And now a minor note, as thin as a low-toned human voice heard faintly through the deep music of a cathedral organ, something seemed to call to him telling him again of these things.

The darkening line where the far-away hills in the south were dragged deeper and deeper into the night drew his wandering thoughts away from himself and sent them skimming after the girl he had seen that day. Somewhere out there she was moving across the desert, plunged into the innermost circle of the grim solitude. He remembered her eyes and the look he had seen in them. He could see her again as she jerked in her plunging horse, as she caught the step of the swiftly moving train. The desert had called her; and she, purposeful, strong, as clean of soul, he felt, as she was of body, had answered the call. With the compelling desire to know her springing full-grown from his first swift interest in her, his fancies, touched by the subtle magic of the desert, showed her to him out yonder with the dusk and the silence about her. He got to his feet and stood staring into the gathering gloom as though he would make out across the flat miles the flying buckboard.

"After all," he told himself, with a restless, half-reckless little laugh, "why not?"

He turned and went back toward the town. On his way he overtook a boy, a little fellow of eight or nine, driving a milk- cow ahead of him. He found him the shy, wordless child he had expected, but chatted with him none the less, and by the time they had reached the first of the scattered buildings the boy had thawed a little and responded to Conniston's talk. After the brief, somewhat uncomfortable lonesomeness of a moment ago Conniston found himself glad of any company. And upon leaving the boy at a tumbled-down house a bit farther on he found a half- dollar in his pocket and proffered it.

"Here, Johnny," he said, smiling. "This is for some candy."

The boy put his hands behind his back. "My name's William," he said, with a quiet, odd dignity. "An' I don't take money off'n no one 'less I work for it!"

"My name's William, too, my boy," Conniston answered, much amused; "but you and I have very different ideas about taking money!"

"Proud little cuss," he told himself, as he strode on along the street. "Wonder who taught him that?"

Here and there in the dull dome above him the stars were beginning to come out. On either hand the pale-yellow rays from kerosene-lamps straggled through windows and doors, making restless shadows underfoot. From the door of the saloon the brightest light crept out into the night. And with it came men's voices. Having a desire for companionship, and not craving that of Hapgood in his present mood, Conniston stepped in at the low door, and, going to the bar, called for a glass of beer. There were half a dozen men, among whom he recognized the proprietor of the "hotel" and the men with whom he had been playing cards, and also the cowboys who had eaten at the other table. In the center of the room, under a big nickeled swinging-lamp, a man was dealing faro while the others standing or sitting about him made their bets. A glance told Conniston that the hotel man was playing heavily, his chips and gold stacked high in front of him.

"The strange part of it," he thought, as he watched the bartender open his bottle of beer, "is where they get so much money! Do they make it out of sand?"

He invited the bartender to drink with him, chatted a moment, and then strolled over to the table. The dealer, a thick-set, fat-fingered, grave-eyed man who moved like a piece of machinery, glanced up at him and back to his game. There was no "lookout." A man whom he had not seen before, deft-fingered and alert, was keeping cases. The proprietor of the hotel, the three cowboys, and one other man were playing.

Familiar with the greater number of common ways of separating oneself from his money, Conniston was no stranger to the ways of faro. He watched the fat fingers of the banker as they slipped card after card from the box, and smiled to himself at the fellow's slowness. And before half a dozen plays were made his smile was succeeded by a little shock of surprise. It certainly did not do to judge people out here in a flash and by external signs. What seemed awkwardness a moment ago was now perfected, automatic skill.

The hotel man won and lost, his face always inscrutable, tilted sidewise as he closed one eye against the up-curling smoke from the cigar which he turned round and round between his pursed lips. He had in front of him a stack of ten or twelve twenty- dollar gold pieces which his fingers continually moved and shifted, breaking them into several smaller stacks, bringing them together again, slipping one over another, gathering them into one stack, breaking them down again, so that the golden disks gave out the low musical clink which rose at all times faint and clear through the few short-spoken words. And meanwhile his eyes never left the table and the box.

At the end of the sixth deal he coppered his bet and leaned back to light a fresh cigar. He stood already a hundred dollars to the good. One of the cowboys was winning, having taken in something like twenty or thirty dollars since Conniston came in. The other two were playing recklessly and with little skill, and were losing steadily. The fifth man contented himself with small bets.

Presently the younger of the two cowboys, the fellow whom Conniston had seen at the store in the afternoon, shoved his last two dollars and a half onto the table, lost, and got to his feet, shrugging his shoulders.

"Cleaned," he grunted, laconically. "Gimme a drink, Smiley."

He went to the bar with one lingering look behind him. And in another play or two his companion followed him.

"No kind of luck, Jimmie," he said to the first to be "cleaned." "Ain't it sure enough hell how steady a man can lose?"

"Bein' as my luck took a day off six months ago an' ain't showed up yet," retorted Jimmie, "I guess I'd ought to had sense to leave inves'ments like the bank alone. Only I ain't got the gumption. An' I'm always figgerin' it's about time for my luck to git over her vacation an' come back to work. How much did you drop, Bart?"

"Forty bucks," returned Bart, reaching for the whisky-bottle. "Which same forty was all I had. Here's how."

"How," repeated his companion.

"I'm laying you a bet," said Conniston, quietly, coming toward them from the table.

Jimmie put down his glass, stared reminiscently at it for a moment, and then, lifting his eyebrows, turned to Conniston. "Evenin', stranger. You might have made a remark?"

"If your luck has been working for other people for six months it's my bet that it's on the way home to you right now! I don't mean any offense, and I am not sure of your customs out here. But I'll stake you to five dollars and take half what you win."

Jimmie grinned and put out his hand. "Which I call darn good custom, East or West!"

For a few minutes it looked as though Conniston's money were going to retrieve the cowboy's losses. Jimmie had already twenty dollars in front of him. And then a gambler's "hunch," a staking of everything on one play, and Jimmie sat back with nothing to do but roll a cigarette.

"I might have giv' back your fiver a minute ago, but now—"

He ended by licking his brown cigarette-paper together. But his credit was good with the bartender, and Conniston and Bart joined him in having a drink.

"It looks like my luck had started back toward the home corrals all right," said Jimmie, with a meditative smile. "Only she wasn't strong enough to make it all the way. She got weak in the knees an' went to sleep on the road. Now, if I had a fist full of money—" He sighed the rest into his glass.

"If the stranger," put in Bart, studying his own brown paper and tobacco-sack, "has got any more money he wants to—"

Conniston laughed. "Much obliged. I think I'll quit with five to-night."

Suddenly Jimmie got another of his "hunches." He cast a swift, apprising glance at Conniston, and then, tugging Bart's sleeve, drew him to the door. Conniston could hear their voices outside, and, although he could not catch their words, he knew from the tone that Jimmie was urging, while Bart demurred. They came back and had another drink at the bartender's invitation, after which they stepped to the table and watched the play for five minutes.

"I'd 'a' won twice runnin'," grunted Jimmie. "We ought to make a try."

Bart hesitated, watched another play, and said, shortly: "Go to it. If you can put it across I'm with you."

Whereupon Jimmie returned to Conniston and made him a proposition. And ten minutes later, when Conniston went smiling back to the hotel, Jimmie and Bart were playing again, each with a hundred dollars in front of him.

ROGER HAPGOOD lifted his pale, heavy-lidded eyes from the pages of his magazine and regarded Conniston with a look from which not all reproach had yet gone.

"I hope you've been enjoying yourself in this Eden of yours," he said, sourly.

Conniston sent his hat spinning across the room, to lodge behind the bed, and laughed.

"You've called the turn, Sobersides! I've been having the time of my young life. And now all I have to do is sit tight to see—"

"See—what?" drawled Roger.

"I've laid a bet, and it's wedged so and hedged so that I win both ways!" Greek chuckled gleefully at the memory of it.

"What sort of a bet?"

"Two hundred dollars!"

Hapgood put down his magazine and got to his feet, plainly concerned. "You don't mean that, Greek?"

"I mean exactly that." Conniston tossed to the bed a small handful of greenbacks and silver. "This is all that's left to the firm of Conniston and Hapgood."

With quick, nervous fingers Hapgood swept up the money and counted it. His eyes showing the uneasiness within him, he turned to the jubilant Conniston.

"There are just twenty-seven dollars and sixty cents. Are you drunk?"

Conniston giggled, his amusement swelling in pace with Hapgood's dawning discomfiture.

"I told you I had made a bet. I have laid a wager with the Fates. And right now, my dear Roger, while we sit comfortably and smoke and wait, the Fates are deciding things for us!"

Roger paused, regarding him. "Yes, you're drunk. If you are not, is it asking too much to suggest that you explain?"

"No. I'll explain. At the sign of the local Whisky Barrel there is a game of faro now in progress. Two very charming young gentlemen, named Jimmie and Bart, punchers of cattle, whatever that may be, are deciding things for Roger Hapgood and William Conniston, Junior, of New York. Each of the amateur gamblers—and they actually do play very badly, Roger!—has before him a hundred dollars of my money. If they win to-night I get back two hundred dollars plus half their winnings, and you and I take the train for San Francisco!"

"If they win. And if they lose?"

"We'll take it as a sign that the Fates have decreed that we're not to go on to the city by the Golden Gate, but tarry here! Both Jimmie and Bart are provided with saddle-horses, with chaps—chaps, my dear Roger, are wide, baggy, shaggy, ill- fitting riding-breeches, made, I believe, out of goat's hide with the hairy side out!—spurs and quirts—in short, all the necessary paraphernalia and accoutrements of a couple of knights of the cattle country. If they lose the two hundred dollars we win the two outfits! And to-morrow, instead of riding in a Pullman toward San Francisco, we straddle what they call a hay-burner for the blue rim of mountains in the south!"

Hapgood stared incredulously, a sort of horror dawning in his pale little eyes.

"I suppose this is another of your purposeless jokes," he said, stiffly, after a moment.

"Nothing of the kind! Don't you see we win either way? Frankly, I am persuaded that the two hundred dollars are now winging their way into the pockets of an apparently awkward dealer with slow fingers, and into the pockets of our friend the hotel man. But we will get the horses, and think of the lark—"

"Lark!" shrilled Hapgood. "A lark—to go wandering off into the desert—"

"Not wandering! Pirutin' is the word you want, the real vernacular of the West. Or skallyhutin'! I'm strong for the sound of the latter myself—"

"Oh, rot!" broke in Hapgood. "I was a fool to come out here with a fool like you."

He turned his back squarely upon Conniston and stood staring out the little window, biting his thin lips. Conniston stood eying him, and slowly the smile passed from his face, to be followed by a serious frown.

"I thought you'd kick in for the sport of it," he said, after a moment, his voice quiet and a trifle cold. "You don't have to if you feel like that about it. You still have your ticket to San Francisco. You can have half of that twenty-seven dollars. You can sell your horse if we win the brutes."

Hapgood had been thinking about that before Conniston spoke. And his thoughts had gone further. It would not be long, he told himself shrewdly, before Conniston Senior softened. And then there would be much money to help spend, many dinners to help eat, much wine to help drink, a string of glittering functions to attend. And if he broke with Greek now—

"See here, Greek," he said, affably, forcing a smile. "What's the use of this nonsense? Why not slip your father a wire now. He'll come across. And then we can go on as we had intended and—"

"Nothing doing." For once Conniston was stubborn. "I'm going on with this thing. If those horses come to us I am going to start early in the morning for the mountains to see what I can see. You can do as you please."

Hapgood glanced at him quickly, and, despite the wrath boiling up within him, the shrewder side of his nature prompted a peaceful answer.

"Then I'll go with you. You didn't think that I was the sort of a fellow to go back on you now, did you? We'll see this thing through together."

Conniston put out his hand impulsively, ashamed of having misjudged his friend.

Long before midnight Jimmie left the saloon and crept away to the stable to stroke the soft nose of a restive cow-pony, and to swear soft, endearing curses of eternal farewell. Not long afterward he had the satisfaction of seeing his fellow-cowboy steal through the darkness to whisper good-by to his own horse. And in the early dawn both Jimmie and Bart stood peering out from behind the corner of the barn at two figures riding rapidly southward into the morning mists.

That day's ride was a matter never to be forgotten by the two men. Their muscles were soft from dissipation and long years of idleness. In particular did Hapgood suffer. He was a slight man to whom nature had given none of the bigness of body which she had bestowed upon Conniston. His luxury-loving disposition had made him abjure the sports which the other at one time and another had enjoyed. He was, besides, a very poor horseman, while Conniston had ridden a great deal. To-day his horse—a spirited colt newly broken—was not content to go straight ahead as Hapgood would have had him, but danced back and forth across the road, shied at every conceivable opportunity, threatening constantly to unseat his rider, and jerked at the restraining, tight-gathered reins until Hapgood's arms ached.

The sun soon drove away the early mists and beat down upon the two men mercilessly from a blazingly hot sky. Nowhere was there any shade except the tiny pools of shadow at the roots of the scrub brush. The heat, the dry air shimmering over the glowing sands, abetted by the many high-balls of yesterday, soon engendered a scorching thirst, and as mile after mile of the treeless desert slipped behind they found no water. Over and over Hapgood was tempted to turn back. He felt that his shoulders, from which he had removed his coat, were blistering under the sharp rays of the sun. At every swinging stride his horse made he felt the skin being rubbed off of his legs where they rubbed against the saddle leather. His soft hands were cut by the reins, he was sore from the tips of his fingers to the soles of his feet. But as each fresh temptation assailed him a glance at Conniston, riding a few paces ahead, made him pull himself together. For some day the old man would relent, and then Roger Hapgood would see that for every agonized mile now he would be amply repaid.

And no water would they find until Indian Creek was thirty miles behind them unless they turned from their way and rode a couple of miles to the westward where the straggling stream crawled through the sand. It was as well that they did not know, for the stream, like many of its kind in the dry parts of the West, ran for the greater part of its course underground, showing only here and there in a pool, where, beneath the sand, there was the hard-pan through which the water could not seep.

They had left the town behind them at a lope. Now they rode at a walk, curbing their horses' impatience with tight-drawn reins. They had thought to have reached the brown hills and shade before the day's heat was upon them. But now it was already intense, stifling, awaking from its light doze almost as the sun rolled upward across the low horizon.

And now the temptation upon Roger Hapgood, urging him to turn back—back toward the little town, hateful yesterday, but spelling now at least the courtyard to comfort—was so strong that he would not have had strength to resist had he not realized that the ride back would be longer than the ride on to water. He made no answer to Conniston's sallies, but, sullenly silent, clung to his reins with one hand, to the horn of his saddle with the other, lifting his head now and again to gaze with red-rimmed eyes ahead along the dusty, flat stretch of the desert, for the most part head down, the picture of misery.

Conniston, feeling the heat riotous in his own veins, feeling the ache of fatigued muscles, felt a sudden pity for Hapgood. And still, even through his own discomfort, there laughed always a certain something in his buoyant nature which saw the humorous in the adventure.

It was late in the forenoon when they saw a clump of green willows, and ten minutes later came to a roadside spring and watering-trough. Hapgood threw an aching leg over the horn of his saddle and slipped stiffly to the ground. Conniston dismounted after him, holding the two horses' reins as they thrust their dry muzzles deep into the clear water. Hapgood, applying his mouth to the pipe from which the water ran into the trough, drank long and thirstily, and then, dragging his feet heavily, went to the clump of willows and dropped to the ground in their shade.

"We've done thirty miles, anyway," said Conniston, cheerily, when he, too, had drunk. "Twenty miles farther to the hills, and—"

Hapgood, his head between his hands, groaned.

"Twenty miles farther and I'll be dead. I couldn't eat any of that infernal mess last night, and I couldn't eat beefsteak and mashed potatoes this morning. And I've got pains through me now in a dozen places. I wish—"

He broke off suddenly. There was little use to tell what he wished: a cool club-room on Broadway; a deep, soft leather chair; a waiter to bring him delicate dishes and cool drinks.

For an hour they sat in the shade resting. Then Conniston got to his feet and threw his reins over his horse's head.

"Come on, Roger," he said, quietly, the unusual gentleness of his tone showing the pity he felt. "We can't stay here all day."

Hapgood rose wordlessly and walked stiffly to his horse. He cursed it roundly when it jerked back from him, and for five minutes he strove to mount. The animal, high strung and restless, was frightened, first at his lunging gait, then at his loud, angry voice, and jerked away from him each time that he tried to get his foot into the stirrup. But at last, with the aid of Conniston, who rode his own horse close to the other, preventing its turning, Hapgood climbed into the saddle. And again in silence they pushed on toward the hills.

It took them five hours to do the twenty miles lying between the watering-trough and the edge of the hills. A large part of the last ten miles Hapgood did on foot, leading his astonished horse. And often he stopped to rest, squatting or lying full length on the ground. It was nearly five o'clock in the afternoon when at last they came to the second spring by the roadside. And here Hapgood sank down wearily, muttering colorlessly that he could not and would not go a step farther. And they were still forty miles to the nearest cabin and bed.

Conniston unsaddled the two horses, watered them, and staked them out to crop the short, dry grass. And then he stood by the spring, smoking and frowning at the barren brown hills. They had had nothing to eat since early morning; they had not thought to bring any lunch with them. And now if they spent the night here it would be close upon noon on the next day before they could hope to find food. He looked covertly at his friend, only to see him sprawled on the ground, his head laid across his arm.

"Poor old Roger," he muttered to himself. "This is pretty hard lines. And a night out here on the ground—"

He determined to wait until the cool of the evening and then to persuade Hapgood to ride with him across the hills. It would be hard, but it seemed not only best, but almost the only way. So Conniston filled his pipe, thought longingly of the cigarettes he had left in his suit-case at the hotel, and, lying down near Hapgood, smoked and dozed in the warm stillness.

An hour passed. The shadow of the scrub-oak under which they had thrown themselves was a long blot across the sand. About them everything was drowsy and sleepy and still. Conniston, turning upon his side, his pipe dropping dead from between his teeth, saw that Hapgood was asleep. He lay back, looking upward through the still branches of the oak, his spirit heavy with the heaviness of nature about him. And musing idly upon the new scenes his exile had already brought him, musing on a pair of gray eyes, Conniston himself went to sleep.

The sun was low down in the western sky, dropping swiftly to the clear-cut line of the horizon, the air growing misty with the coming night, the sunset sky glowing gold and flaming crimson, when Conniston awoke. He sat up rubbing his eyes, at first at a loss to account for his surroundings. Then he saw Hapgood sprawled at his side and remembered. And then, too, he saw what it was that had awakened him.

A man in a buckboard drawn by two sweating horses was looking curiously at him while his horses drank noisily at the trough. He was an unmistakable son of the West, bronzed and lean and quick- eyed. The long hair escaping from under his battered gray hat vied with his long drooping mustache in color, and they both challenged the flaming crimson of the sunset. Conniston told himself that he had never seen hair one-half so fiery or eyes approaching the brilliant blueness of this man's. And he told himself, too, that he had never been gladder to see a fellow human being. For the horses were headed toward the hills in the south.

"How are you?" Conniston cried, scrambling to his feet and striding with heavy feet to the buckboard.

"Howdy, stranger?" answered the red-headed man, his voice strangely low-toned and gentle.

"My name's Conniston," went on the young man, putting out a hand which the other took after eying him keenly.

"Real nice name," replied the red-headed man. And dropping Conniston's hand and turning to his horses, "Hey there, Lady! Quit that blowin' bubbles an' drink, or I'll pull your ol' head off'n you!"

Lady seemed to have understood, and thrust her nose deeper into the water. And the new-comer, catching his reins between his knees, took papers and tobacco from the pocket of a sagging, unbuttoned vest and made a cigarette. Licking the paper as a final touch, his eyes went to Hapgood.

"Pardner sick or something?"

"No. Just fagged out. We came all the way from Indian Creek since morning."

"That's real far, ain't it?" remarked the man in the buckboard, with a little twitch to the corner of his mouth, but much deep gravity in his eye. "Which way you goin', stranger?"

"We're going across the hills into the Half Moon country. It's forty miles farther, they tell me."

"Uh-uh. That's what they call it. An' a darn long forty mile, or I'll put in with you."

"And," Conniston hurried on, "if you are going—You are going the same way, aren't you?"

"Sure. I'm goin' right straight to the Half Moon corrals."

"Then would you mind if my friend rode with you? I'll pay whatever is right."

The other eyed him strangely. "I reckon you're from the East, maybe? Huh?"

"Yes. From New York."

"Uh-uh. I thought so. Well, stranger, we won't quarrel none over the payin', an' your frien' can pile in with me."

Conniston turned, murmuring his thanks, to where Hapgood now was sitting up. And the red-headed man climbed down from his seat and began to unhitch his horses.

"You needn't git your frien' up jest now in case he ain't finished his siesta. We won't move on until mornin'."

"Where are you going to sleep?" Hapgood wanted to know.

"I had sorta planned some on sleepin' right here."

"Right here! You don't sleep on the ground?"

The red-headed man, drawing serenely at his cigarette, went about unharnessing his horses.

"Bein' as how I ain't et for some right smart time," he was saying as he came back from staking out his horses, "I'm goin' to chaw real soon. Has you gents et yet?"

They assured him that they had not.

"Then if you've got any chuck you want to warm up you can sling it in my fryin'-pan." He dragged a soap-box to the tail end of the buckboard and began taking out several packages.

"We didn't bring anything with us," Conniston told him. "We didn't think—"

The new-comer dropped his frying-pan, put his two hands on his hips, and stared at them. "You ain't sayin' you started out for the Half Moon, which is close on a hundred mile, an' never took nothin' along to chaw!"

Conniston nodded. The red-headed man stared at them a minute, scratched his head, removing his hat to do so, and then burst out:

"Which I go on record sayin' folks all the way from Noo York has got some funny ways of doin' business. Bein' as you've slipped me your name, frien'ly like, stranger, I don't min' swappin' with you. It's Pete, an' folks calls me Lonesome Pete, mos'ly. An' you can tell anybody you see that Lonesome Pete, cow- puncher from the Half Moon, has made up his min' at las' as how he ain't never goin' any nearer Noo York than the devil drives him."

He scratched his head again, put on his hat, and reached once more for his frying-pan.

LONESOME PETE dragged from the buckboard a couple of much-worn quilts, a careful examination of which hinted that they had once upon a time been gay and gaudy with brilliant red and green patterns. Now they were an astonishing congregation of lumps where the cotton had succeeded in getting itself rolled into balls and of depressions where the cotton had fled. Light and air had little difficulty in passing through. Lonesome Pete jerked off the piece of rope which had held them in a roll and flung them to the ground, directing toward Hapgood a glance which was an invitation. And Hapgood, the fastidious, lay down.

The red-headed man dumped a strange mess out of a square pasteboard box into his frying-pan and set it upon some coals which he had scraped out of his little fire. There was dried beef in that mess, and onions and carrots and potatoes, and they had all been cooked up together, needing only to be warmed over now. The odor of them went abroad over the land and assailed Hapgood's nostrils. And Hapgood did not frown, nor yet did he sneer. He lifted himself upon an elbow and watched with something of real interest in his eyes. And when black coffee was made in a blacker, spoutless, battered, dirty-looking coffee-pot Roger Hapgood put out a hand, uninvited, for the tin cup.

Conniston, his appetite being a shade further removed from starvation than his friend's, divided his interest equally between the meal and the man preparing it. He found his host an anomaly. In spite of the fiery coloring of mustache and hair he was one of the meekest-looking individuals Conniston had ever seen, and certainly the most soft-spoken. His eyes had a way of losing their brightness as he fell to staring away into vacancy, his lips working as though he were repeating a prayer over and over to himself. The growth upon his upper lip had at first given him the air of a man of thirty, and now when one looked at him it was certain he could not be a day over twenty. And about his hips, dragging so low and fitting so loosely that Conniston had always the uncomfortable sensation that it was going to slip down about his feet, he wore a cartridge-belt and two heavy forty-five revolvers. He gave one the feeling of a cherub with a war- club.

During the scanty meal Lonesome Pete ate noisily and rapidly and spoke little, contenting himself with short answers to the few questions which were put to him, for the most part staring away into the gathering night with an expression of great mildness upon his face. Finishing some little time before his guests, he rolled a cigarette, left them to polish out the frying-pan with the last morsels of bread, and, going back to the buckboard, fumbled a moment in a second soap-box under the seat. It was growing so dark now that, while they could see him take two or three articles from his box and thrust them under his arm, they could not make out what the things were. But in another moment he had lighted the lantern which had swung under the buckboard and was squatting cross-legged in the sand, the lantern on the ground at his side. And then, as he bent low over the things in his hand, they saw that they were three books and that Lonesome Pete was applying himself diligently to them.

He opened them all, one after the other, turned many pages, stopping now and then to bend closer to look at a picture and decipher painstakingly the legend inscribed under it. Finally, after perhaps ten minutes of this kind of examination, he laid two of them beside him, grasped the other firmly with both awkward hands and began to read. They knew that he was reading, for now and again his droning voice came to them as he struggled with a word of some difficulty.

Hapgood smoked his last cigarette; Conniston puffed at his pipe. At the end of ten minutes Lonesome Pete had turned a page, the rustling of the leaves accompanied by a deep sigh. Then he laid his book, open, across his knee, made another cigarette, lighted it, and, after a glance toward Conniston and Hapgood, spoke softly.

"You gents reads, I reckon? Huh?"

"Yes. A little," Conniston told him; while Hapgood, being somewhat strengthened by his rest and his meal, grunted.

"After a man gets the swing of it, sorta, it ain't always such hard work?"

"No, it isn't such hard work after a while."

Lonesome Pete nodded slowly and many times.

"It's jest like anything else, ain't it, when you get used to it? Jest as easy as ropin' a cow brute or ridin' a bronco hoss?"

Conniston told him that he was right.

"But what gits me," Lonesome Pete went on, closing his book and marking the place with a big thumb, "is knowin' words that comes stampedin' in on you onexpected like. When a man sees a cow brute or a hoss or a mule as he ain't never clapped his peepers on he knows the brute right away. He says, 'That's a Half Moon,' or, 'It's a Bar Circle,' or 'It's a U Seven.' 'Cause why? 'Cause she's got a bran' as a man can make out. But these here words"—he shook his head as he opened his book and peered into it—"they ain't got no bran'. Ain't it hell, stranger?"

"What's the word, Pete," smiled Conniston.

"She ain't so big an' long as bothers me," Lonesome Pete answered. "It's jest she's so darn peculiar-lookin'. It soun's like it might be izzles, but what's izzles? You spell it i-s-l-e-s. Did you ever happen to run acrost that there word, stranger?"

Conniston told him what the word was, and Lonesome Pete's softly breathed curse was eloquent of gratitude, amazement, and a certain deep admiration that those five letters could spell a little island.

"The nex' line is clean over my head, though," he went on, after a moment of frowning concentration.

Conniston got to his feet and went to where the reader sat, stooping to look over his shoulder. The book was "Macbeth." He picked up the two volumes upon the ground. They were old, much worn, much torn, their backs long ago lost in some second-hand book-store. One of them was a copy of Lamb's Essays, the other a state series second reader.

"Quite an assortment," was the only thing he could think to say.

Lonesome Pete nodded complacently. "I got 'em off'n ol' Sam Bristow. You don't happen to know Sam, do you, stranger?"

Conniston shook his head. Lonesome Pete went on to enlighten him.

"Sam Bristow is about the eddicatedest man this side San Francisco, I reckon. He's got a store over to Rocky Bend. Ever been there?"

Again Conniston shook his head, and again Lonesome Pete explained:

"Rocky Bend is a right smart city, more'n four times as big as Injun Creek. It's a hundred mile t'other side Injun Creek, makin' it a hundred an' fifty mile from here. In his store he's got a lot of books. I went over there to make my buy, an' I don't mind tellin' you, stranger, I sure hit a bargain. I got them three books an nine more as is in that box under the seat, makin' an even dozen, an' ol' Sam let the bunch go for fourteen dollars. I reckon he was short of cash, huh?"

Since the books at a second-hand store should have been worth about ninety cents, Conniston made no answer. Instead he picked up the dog-eared volume of "Macbeth."

"How did you happen to pick out this?" he asked, curiously.

"I knowed the jasper as wrote it."

Conniston gasped. Lonesome Pete evidently taking the gasp as prompted by a deep awe that he should know a man who wrote books, smiled broadly and went on:

"Yes, suh. I'm real sure I knowed him. You see, I was workin' a couple er years ago for the Triangle Bar outfit. Young Jeff Comstock, the ol' man's son, he used to hang out in the East. An' he had a feller visitin' him. That feller's name was Bill, an' he was out here to git the dope so's he could write books about the cattle country. I reckon his las' name was the same as the Bill as wrote this. I don't know no other Bills as writes books, do you, stranger?"

Conniston evaded. "Are you sure it's about the cattle country?"

"It sorta sounds like it, an' then it don't. You see it begins in a desert place. That goes all right. But I ain't sure I git jest what this here firs' page is drivin' at. It's about three witches, an' they don't say much as a man can tie to. I jest got to where there's something about a fight, an' I guess he jest throwed the witches in, extry. Here it says as they wear chaps. That oughta settle it, huh?"

There was the line, half hidden by Lonesome Pete's horny forefinger. "He unseamed him from the nave to the chaps!" That certainly settled it as far as Lonesome Pete was concerned. Macbeth was a cattle-king, and Bill Shakespeare was the young fellow who had visited the Triangle Bar.

Thoughtfully he put his books away in the box, which he covered with a sack and which he pushed back under the seat. Then he looked to his horses, saw that they had plenty of grass within the radius of tie-rope, and after that came back to where Hapgood lay.

"I reckon you can git along with one of them blankets, stranger. You two fellers can have it, an' I'll make out with the other."

Hapgood moved and groaned as he put his weight on a sore muscle.

"The ground will be d——d hard with just one blanket," he growled.

Lonesome Pete, his two hands upon his hips, stood looking down at him, the far-away look stealing back into his eyes.

"I hadn't thought of that. But I reckon I can make one do, all right."

Whereupon without more ado and with the same abstracted gleam in his eyes he stooped swiftly and jerked one of the quilts out from under the astonished Hapgood.

The man who had traveled from the Half Moon one hundred and ninety miles to spend fourteen dollars for a soap-box half full of books was awake the next morning before sunrise. Conniston and Hapgood didn't open an eye until he called to them. Then they looked up from their quilt to see him standing over them pulling thoughtfully at the ends of his red mustache, his face devoid of expression.

"I'll have some chuck ready in about three minutes," he told them, quietly. "An' we'll be gittin' a start."

"In the middle of the night!" expostulated Hapgood, his words all but lost in a yawn.

"I ain't got my clock along this trip, stranger. But I reckon if we want to git acrost them hills before it gits hot we'll be travelin' real soon. Leastways," as he turned and went back to squat over the little fire he had blazing merrily near the watering-trough, "I'm goin' to dig out in about twenty minutes."

Hapgood, remembering the ride of yesterday, scrambled to his feet even before Conniston. And the two young men, having washed their faces and hands at the pipe which discharged its cold stream into the trough, joined the Half Moon man.

He had already fried bacon, and now was cooking some flapjacks in the grease which he had carefully saved. The coffee was bubbling away gaily, sending its aroma far and wide upon the whispering morning breeze. The skies were still dark, their stars not yet gone from them. Only the faintest of dim, uncertain lights in the horizon told where the east was and where before long the sun would roll up above the floor of the desert. The horses, already hitched to the buckboard, were vague blots in the darkness about them.

They ate in silence, the two Easterners too tired and sleepy to talk, Lonesome Pete evidently too abstracted. And when the short meal was over it was Lonesome Pete who cleaned out the few cooking-utensils and stored them away in the buckboard while Conniston and Hapgood smoked their pipes. It was Lonesome Pete who got his two quilts, rolled, tied, and put them with the box of utensils. And then, making a cigarette, he climbed to his seat.

"An' now if one of you gents figgers on ridin' along with me—"

"I do!" cried Hapgood, quickly. And he hastened to the buckboard, taking his seat at the other's side.

"I thought you had a hoss somewheres! An' your saddle?" continued Lonesome Pete.

"I thought that while you were getting your horses—Didn't you saddle him?"

For a moment Lonesome Pete made no answer. He drew a deep breath as he gathered in his reins tightly. And then he spoke very softly.

"Now, ain't I sure a forgetful ol' son of a gun! I did manage to rec'lec' to make a fire an' git breakfas' an' hitch up my hosses an' clean up after breakfas' an' put the beddin' in—but would you believe I clean forgot to saddle up for you!"

He laughed as softly as he had spoken. Hapgood glanced at him quickly, but the cowboy's face was lost in the black shadow of his low-drawn hat. Hapgood got down and saddled his own horse, and it was Hapgood who, riding with Lonesome Pete, led a stubborn animal that jerked back until both of Hapgood's arms were sore in their sockets. Lonesome Pete, the forgetful, remembered after an hour or two of quiet enjoyment to tell the tenderfoot that he could tie the rope to the buckboard instead of holding it. For the first hour Hapgood was, consequently, altogether too busy even to try to see the country about him, and Conniston, riding behind, could make out little in the darkness. The one thing of which he could be sure was that they were leaving the floor of the desert behind, that they were climbing a steep, narrow road which wound ever higher and higher in the hills. Then finally the day broke, and he could see that they were already deep in the brown hills which he had seen from Indian Creek. There was scant vegetation, a few scattered, twisted, dwarfed trees, with patches of brush in the ravines and hollows. Nowhere water, nowhere a sprig of green grass. As in the flat land below here, there was only barrenness and desolation and solitude.

As had been the case yesterday, so now to-day when the sun shot suddenly into the sky the heat came with it. But already the three travelers had climbed to the top of the hills where Pocket Pass led across the uplands and were once more dropping down toward a gray level floor. On a narrow bit of bench land, where for a space the country road ran level, lined with ruts, gouged with uncomfortable frequency into dust-concealed chuck-holes, Lonesome Pete pulled in his horses and waited for Conniston to ride up to his side.

"In case you've got a sorta interest in the country we're goin' to drop down in," he said, as he took advantage of the stop to roll a cigarette, "you might jest take a look from here. This is what they call Pocket Pass as we jest rode through. An' from this en' you can see purty much everything as is worth seein' in this country an' a whole hell of a lot as ain't." He made a wide sweep with his arm, pointing southward and downward. "That there's where we're headed for."

"And that's the Half Moon!" Conniston was eager, as he saw at a glance how the range got its name.

The hills fell away even more abruptly here than they did in the north, cut so often into straight, stratified brown cliffs of crumbling dirt that Conniston wondered how and where the road could find a way out and down into the lower land. They swept away, both east and west, in a wide curve, roughly resembling a half moon. Toward the east, perhaps twenty-five miles from where Conniston sat upon his horse, the distant mountains sent out two far-reaching spurs of pine-clad ridges between which lay Rattlesnake Valley. Due south, as Lonesome Pete's outstretched finger indicated, lay the road which they were to follow and the headquarters of the Half Moon. There again a thickly timbered spur of the mountains ran down into the plain on each side of a deeply cleft cañon from which Lonesome Pete told them that Indian Creek issued, and in which were the main corrals and the range house of the Half Moon.

"Which is sure the finest up-an'-down cow-country I ever see," he added, by way of rounding off his information. "Bein' well watered by that same crick, an' havin' good feed both in the Big Flat, as folks calls that country down below us, an' in the foothills. Rattlesnake Valley, over yonder, ain't never been good for much exceptin' the finest breed of serpents an' horn-toads a man ever see outside a circus or the jimjams. There ain't nothin' as 'll grow there outside them animals. The ol' man's workin' over there now, tryin' to throw water on it an' make things grow. The ol' man," he ended, shaking his head dubiously, "has put acrost some big jobs, but I reckon he's sorta up against it this trip."

"Reclamation work," nodded Conniston.

"That's what some folks calls it. Others calls it plumb foolishness. Git up, there, Lady! Stan' aroun', you pinto hoss!"