RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a public domain wallpaper

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a public domain wallpaper

"The Immortal Light," Cassell and Co. Ltd., London, 1907

"The Immortal Light," Cassell and Co. Ltd., London, 1907

John Mastin (1865-1932)

"I will say to the north, Give up; and to the south, Keep not back."

—Isaiah, xliii. 6.

Totley Brook, near Sheffield, July 1907.

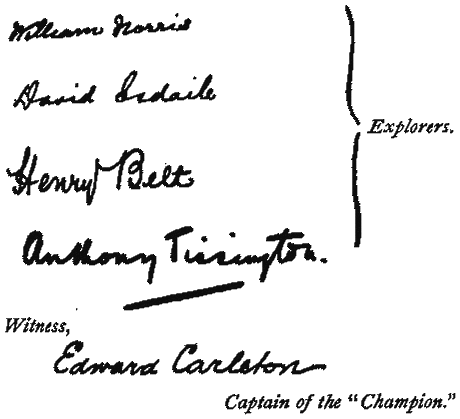

Lest any reader should doubt the truth of the wonderful adventures related in the following pages, we hereby certify that this narrative is a true, unvarnished record of actual facts. As witness our hands—

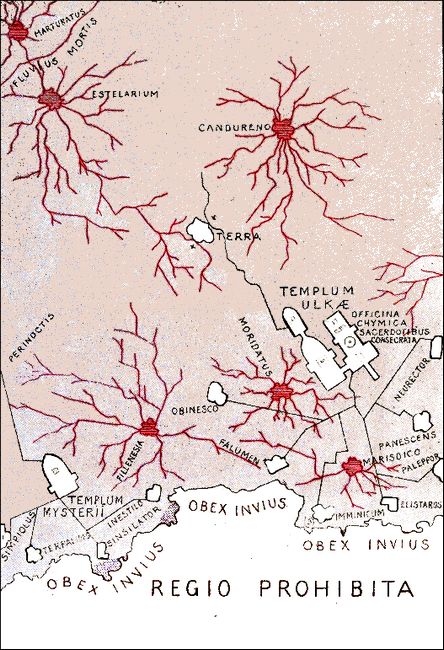

Copy of map engraved on a sheet of white flexible

glass found in the underground temple of Ulka.

"Narrow minds think nothing right that is above their own capacity."

—La Rochefoucauld.

AS one of the four who were sent in charge of an expedition fitted out by private enterprise in order to explore the Antarctic regions, I am asked to write an account of our wonderful and exciting adventures in that unknown land. The success of the expedition was mainly due to Esdaile's invention of self-heating steel which had made him famous a few years before; in fact, it was chiefly because of this that the exploration was mooted, and the ship, the Champion, built, the possibility of success being practically assured from the start Needless to say, the results exceeded our highest and most sanguine expectations.

What befell us in this little-known region was so thrilling and wonderful, that but for our previous reputations and standing as scientists, and the marvellous instruments we brought back, people would have been utterly incredulous. In fact, so far as I am concerned, although I have never given the slightest cause for any one to doubt my veracity, yet when I gave a series of lectures on the subject and illustrated the same with lantern slides from photos taken on the spot, even several old friends remarked that it was really astonishing to see how naturally photographs could be made up to look as though taken from the actual place!

When I came to write the story in sober earnest, recording scientific facts in plain words, I thought it better to have the statements attested by my comrades. Therefore, when I had finished, I got them all to stay at my house for a few days, and the matter was gone into carefully and then duly certified as the plain truth; a copy of this document I give first, so that it may be read and remembered should doubts arise.

My name is Anthony Tissington; I am a botanist and man of science, and am so accustomed to looking at, and thinking of, everything in a plain, scientific, matter-of-fact way, that I have no sentiment about anything except my beloved "flora," and therefore, to save future disappointment, I may say at the onset that I cannot write a novel nor do I write this narrative as an exciting, adventurous tale, or as a delineation of the characters of the persons concerned, but simply as a plain, ungarnished record of solid, serious fact. If I fail to please, or the reader say to himself that such a thing, or so and so, could have been related better, or, more dramatically, I can only express my regret at my inability to gratify, and draw his attention to the saying that "facts are stubborn things;" and as it is useless to attempt to gather figs from thistles, so I suppose it is equally useless for me to try to do more than write, in plain and simple language, all that we passed through in that supposedly desolate, forsaken region, and so, with this explanation and apology, which I dare say few will read, I will proceed to my simple tale, taking the reader's friendly indulgence as already given.

"There are few things more impressive to me than a ship."

—Ruskin.

MYSELF I have already introduced; the other leaders of the expedition were Henry Belt, astronomer, William Norris, geologist, and David Esdaile, a metallurgist. The first two are already well known in connection with their explorations in the Arctic regions, having made three successful journeys there together; they therefore need no further introduction. Esdaile, however, is new to the world as an explorer, although well known in scientific circles as one of the most expert metallurgists of the day, and the inventor of the particular alloy of steel and tin known as "Tynstele," which has the remarkable property of retaining any desired heat from its own latent energy. He therefore merits a somewhat more lengthy introduction.

He was very fond of experimenting in alloys, especially in those metals difficult to amalgamate. Now it is apparently impossible to make certain metals combine with others, owing to the great difference in their melting points; thus tin melts at 232° Centigrade, and if heated much above that temperature forms the yellowish white powder of peroxide of tin, or the "putty powder" of commerce. The melting point of steel is about 1750 to 1800° Centigrade, according to its composition, from which it will be seen that these two metals can never alloy because the tin would cease to be metallic tin long before the steel had become even white hot.

Pure tin is not acted upon by the weather and retains its brightness, but steel soon becomes rusty owing to the formation of oxide. It occurred to Esdaile that if he could by any possible means get an alloy of these two metals, he would have the toughness and ductility of steel, with the tin's freedom from oxidation under the influence of moisture, and thus get a white, untarnishable steel of silvery appearance. He therefore made many experiments in order to obtain this seemingly impossible alloy. Whilst working at this, he also commenced experimenting with sulphuric acid, which is commercially made from iron pyrites, or sulphide of iron.

One day when in Derbyshire, at a small quarry near the village of Drybeck, he saw there some brilliant red ironstone; obtaining a sample, he afterwards reduced the iron from it, but this would not yield sulphuric acid. He melted the iron, but no sulphurous fumes were given off; he therefore left it to cool. In a few hours it was still too hot to touch, and in a week's time was no cooler. He worked at this for some months, and finally reduced it to a definite formula; he found that when melted and treated in the ordinary way it was to all appearance good-quality iron, but when heated along with nitrate of soda, and oil of vitriol in a separate vessel, as if for the manufacture of sulphuric acid, (and no other treatment gave the same result,) it retained its heat while in atmospheric air. If this was then gradually mixed with the best crucible cast steel, made from Swedish iron bars heated to 17500 Centigrade, and in the proportion of one part iron to four steel, and when these had mixed, pure tin was thrown in, the latter seemed to volatilize and instantly disappear, but on being poured out into ingots, the whole was silvery white and never cooled below 60° Fahrenheit. This steel was then made into blooms, bars, rods, and thin sheets, all of a beautiful, silvery, untarnishable whiteness, and being of the best quality of steel (self-hardening, manganese, and other forms) could be used for everything, and never lost its heat, even in a refrigerator. Of course by increasing or reducing the proportion of iron when placing it in the liquid steel, a permanently higher or lower temperature could be given, but that of 60° Fahrenheit was decided upon as the standard.

Recognizing the value of this ironstone, Esdaile purchased the quarry, and was thus enabled to manufacture "Tynestele" to any extent.

The arrangements for the expedition had been left in our hands, and all being scientific and practical men, we did not fail to take advantage of anything and everything which might conduce to the success of the enterprise; and knowing the value of Esdaile's invention in so cold a region, it was utilized very ingeniously in the construction of the vessel. The inner casing or lining which formed the actual interior walls, etc., of the vessel was one of the most important features in the ship, consisting of strong plates of "Tynestele" riveted together, which alone kept the vessel at a comfortable temperature throughout, and the asbestos packing behind kept the heat from being lost All the metallic parts of the vessel and the tools were made of "Tynstele," thus everything possessed a natural equable temperature, and those who inhabited this ship would find it a very cosy home even if compelled to remain in it for any length of time.

Rigorous as is the extreme north, it is mild in comparison with the desolate, storm-riven region of the Antarctic Circle, the land of storms of terrific grandeur, awful in their results, which week after week continue with unabated fury. There the cold is so intense that no animals appear able to exist, as none have ever been seen; life is not possible on the land so far south. Therefore, although provision must be made for travelling on solid ground, yet ordinary sledges would be useless, for dogs could not be obtained there, nor could they be taken there and kept alive for any length of time, so we all put our heads together and devised a kind of motor-car-sledge, driven by superheated steam in a very novel and ingenious manner. As we had proved, "Tynstele" can be made to retain any degree of heat, so a series of coil-pipes was made of this steel to remain at a red heat, and water passed through these became instantly converted into steam. The coils did not foul or deteriorate, and, always remaining at the same heat, made a fire quite unnecessary. Further, in order to utilize the ice and snow for the supply, a tank was provided of such a temperature as slowly melted the contents into liquid form.

Near the engines on this sledge ran a line of eight vertical shafts on either side; these could be instantly connected with the engines, when the vanes on them would rapidly revolve and so raise the car in the air to a height of twenty feet if necessary. At the bows was a snow-clearer, and a propeller at the stern; the runners were of the hardest manganese steel. The wheels were of wood pulp saturated with a mixture of hot shellac varnish and paraffin wax, and then highly compressed into solid segments, through each of which ran a rod containing a pneumatic slide at the point where it joined the hub, the whole forming a series of buffers to relieve the jolt when going over uneven ground. In addition to these each car was fitted with eight air-cushion buffers, which made effective resisters to shock, and the sledges could either travel on the runners when on level ground, or if too uneven for this, the axles could be automatically lowered, when the wheels would come below the runners and the sledge become a carriage. The tyres were of semi-circular section steel, and were as resilient as india-rubber pneumatic tyres, which latter would have cracked with the cold. The cars were made entirely of "Tynstele."

The stores were selected with excellent foresight, and were packed in very small compass, as almost everything had been cooked and then compressed hydraulically into "tabloid" or cube form, including fresh meat which had been boned, then dried by a process which retained all the nutriment, and afterwards tremendously compressed into solid cubes of half-inch face, which were light and easily carried about or stored. When one of these cubes was soaked in cold water for some little time, it absorbed the moisture, swelling out and becoming exactly like fresh meat, and, being already cooked, could be eaten cold, or re-cooked as a fresh joint, each cube providing a full, substantial meal for five hungry men. It was not necessary therefore to take any animals, as by these means fresh meat and vegetables would be always obtainable, and the scourge of the colder regions, scurvy, need not be feared, as the whole crew could live on the very best support exactly as if in a London restaurant. No canned meats or fruit had been allowed, and the stores were of course kept in a properly constructed refrigerator.

Our furs were completely lined with short and very thin strips of "Tynstele," beautifully tempered like a watch-spring and as thin, so that even when we should be exposed to cold, almost too cold for life, we should still be enveloped from head to foot in a comfortable and healthy warmth, and in order to prevent frost-bite we had masks made of a non-inflammable material resembling celluloid, lined with a sheet of gauze like a lady's veil, also made of "Tynstele." As the strips on the clothing were small, and placed almost side by side, and the furs well ventilated, the wearers need have no fear of exposure, and would be able to move freely and even sleep on the ice without any other covering or protection; nor need we fear the tools burning our flesh with cold, as whatsoever was used would be warm.

The remainder of the outfit was of the ordinary character for arctic exploration, and needs no comment.

Everything being on board we embarked, and after a rather stormy voyage, arrived at the coast of Victoria Land—the supposed Southern Continent—and prepared to land and travel along the 170th Meridian of W. longitude the many miles which lay between us and the undiscovered country beyond the hitherto impenetrable ice barrier which we aspired, though perhaps vainly, to conquer.

"From peak to peak, the rattling crags among

Leaps the live thunder."

—Byron.

WE had encountered ice from the 40th parallel, and had been obliged to go far out of our course to avoid the immense floes and bergs; consequently, we approached Victoria Land from the west and hugged the coast till nearly opposite Mount Erebus, where we thought it advisable to land. In fact we could not do otherwise, as the sea beyond was so packed with ice that we should have been obliged to saw our way through. For some distance were high mountain ranges, 7,000 to 12,000 feet above sea level, of which Erebus was the most conspicuous, as it was then in a state of active eruption, belching forth flames and lava and continuous clouds of hot ashes.

"It's a wonder where all that stuff comes from and where it goes to," remarked the captain. "I remember the last time I came here he was pouring out lava in thousand-ton lots, and the coast appears unaltered in any way."

"A tremendous quantity of stuff must have come out of it," said Esdaile, "for I expect it has been going on like this since Sir James Ross discovered it during his expedition of 1839, and for long enough before that, no doubt."

Just then Morgan, the first mate, brought the results of his dredging, as he had been asked to get some specimens of the sea bottom. These he now handed to Norris, who at once saw amongst them bits of granite, sandstone, and thin, laminated lumps of mica, proving the existence of actual rock, etc., near the ice barrier, thus confirming the work of the Discovery, which returned to England in September 1904, with the suggestion that this ice barrier of Ross's may be the foot of a tremendous glacier which covers the land or continent. This peculiar ice barrier was, we found out later, a characteristic feature of the region and was most remarkable in appearance. In some places, it rose to a height of 400 feet where it came straight out of the sea, but where there were rocks and steep, rocky cliffs, the ice would be, in places, only ten to fifteen feet high. The tops of all were flat, forming plateaux of vast extent, penetrating far into the interior and running along the coast in an almost unbroken line. Even from our limited elevation, the land appeared chiefly volcanic, for many crater-like tops could be seen around.

As we stood at the rail looking over, we perceived some seals disporting themselves on a berg close by, and overhead several stormy petrels flew around the ship shrilly screaming. About a mile away a great whale came up to blow and then dived; the noise he made frightened the seals, which slid off the berg into the water, some silently, others giving a gentle flop, as of a flung stone. The petrels and penguins also disappeared, leaving a lonely stretch of desolate ice.

"I thought it was too cold for any form of life here," said Belt to the captain.

"So far as I know," he replied, "no animals can exist here except sea animals and fishes, and they come about March."

"The temperature here is very remarkable; at certain times of the year it is much above freezing point, although that does not last long enough to have any appreciable effect on the ice," said I. "I remember that Ross found layers of cold water sandwiched between warm ones, and also currents of warm, tropical water in various places."

"Yes," replied the captain, "it is a curious fact that at fifty degrees south the water at the bottom of the sea is roughly the same as the Indian and all other oceans. The return currents from the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic Oceans run towards the south past America, Africa, and Australia, until they reach the latitude of about fifty degrees south, when they sink, and then flow at the bottom towards the north, to supply that lost by evaporation in the tropics, and towards the south to take the place of the cold water which there is moving north. This will account for the difference in temperature you mention."

"We did not notice this alteration in our voyage here?" said Esdaile.

"Oh, yes!" replied the captain; "when we got to the 40th parallel the temperature was twenty degrees below zero, but at the 50th parallel it had risen to twenty-eight degrees. At the 60th the temperature was thirty-eight degrees, and yet the sea was not free from ice; at the 65th parallel it again fell far below the freezing point of sea water, and just now the temperature is—63° Fahrenheit, and if we were for a moment unprotected we should be frozen immovable with lightning speed, and a mercury thermometer if exposed would soon be solid as a bar of iron."

After a little more conversation we decided to send up the balloon the next day, and then turned in so as to take a good, long rest before beginning our arduous tasks, as we were exceedingly anxious to proceed as far as possible during the long period of light, before the still longer winter which was just closing again set in. Accordingly, the following day we began our preparations for the ascent, hoping to be able to see over the distant inland ice barrier, and perchance find some place where it could be penetrated. We had brought with us a great quantity of hydrogen which had been compressed into solid bars for convenience of storing; a few of these bars were placed on a hot plate of "Tynstele," under which was a thick sheet of asbestos to insulate it from the cold, and these were placed near the mouth of the balloon, so that the gas in expanding gradually distended the silk until the car was tugging at the hooks. A captive rope was now attached, the hooks unfastened, and slowly the balloon ascended, pulling hard at the rope as it was paid out at the windlass. Up we went to a great height until we felt that the rope had sufficient strain on it, when the signal was given to stop. We now searched the horizon with our powerful glasses, and some distance ahead landwards could be seen the inside of several craters, active and extinct, and far away was that great impassable barrier of ice, stretching high above the land, with mountain after mountain of glittering white, rising up so straight and sudden that apparently no human being could ever mount them, even if it were possible to traverse the terrible space between, which was, in itself, a barrier of great bergs, precipices, and awful cracks, evidently caused by volcanic action, which it seemed impossible for any human being to span, unless perchance by such means as we had at our disposal.

The whole of the horizon seemed one mass of desolate snow and ice, we ourselves being the only living objects within sight. We took some photographs, and whilst these were in progress a report like a pistol-shot was heard from below, instantly followed by a twang on our rope. Looking over the side, what was our dismay to see that the rope was broken half across, for the men had made a mistake, unnoticed until too late, and had attached an ordinary rope to the balloon instead of one made of strands of fine "Tynstele" wire, which was extremely flexible and exceedingly strong, all our rigging being made of these ropes as they could never become frozen or stiff.

We at once telephoned to be hauled in, but Carleton, the captain, told us to let out the gas as the rope had frozen into a rod as hard and unyielding as a hammer-shaft. It was brittle as glass and would have to be thawed inch by inch as it was hauled in, lest it should snap off like a carrot in being bent round the drum of the windlass. We pulled at the valve rope, but it refused to act, and then all of us swung on it and—it broke, tumbling us into the bottom of the car. We were now in an awful plight, for the rope was slowly parting strand by strand, and the balloon was tugging jerkily at it with tremendous force; unless we could liberate the gas, we should be loose in a few minutes and drift away, without food or protection, to certain death.

"Let us open the silk," said Belt, "and split the thing up."

"If we do," said Norris, "we shall ruin it. I am going up to the top," and before any one could stop him, he had climbed up the net like a sailor to perform a feat of reckless heroism and daring, which was greeted with cheers from below. Clad in his furs as he was, he went up and up the netting, now hard as iron wire; in a few minutes he was away from the car, hanging over space with his back to the ground like a fly on a ceiling, threading his hands and feet in the broad mesh as he progressed inch by inch up the bellying surface. Now his head disappeared over the roundness of the envelope, then his shoulders, then his body, and last of all his feet, and we lost sight of him.

We could not speak to each other, and endured an eternity of suspense, every moment expecting to see his body fall past us, to be dashed to pieces on the rough and broken ice below. All the crew had turned out to watch this sacrifice of life, as they thought, and they were looking with strained, upturned faces at the brave man whom they could see slowly crawling to the valve doors far over our heads.

We were just going to rip open the silk when we heard the rush of escaping gas, and the dreadful tearing and tugging ceased. What exactly happened we learned later; Norris had reached the doors to find it impossible to get them open, owing to the spring catch and great pressure of gas inside holding them securely together. He feared to slit the silk there lest the sudden release of pressure should cause it to open right across and collapse, thus precipitating its occupants to the ice below like stones; however, there seemed nothing else for it, and he was on the point of drawing his knife to make the fatal incision and risk the consequences, when he thought he might reach the valve catch with his feet, and so this hero took a good grip of the netting, lay full length across the opening of the doors, and giving a vigorous kick, broke the spring catch; his weight being at the junction of the doors, caused them to open. Luckily his head was outside, or he would have been instantly asphyxiated, for the doors slowly opened more and more under his weight till he was nearly upright, with his body from the waist downwards inside the balloon, where he fortunately became wedged between the folding doors. This relieved the weight from his hands, and so he stretched his head away from the opening as much as possible, whilst the gas poured out in suffocating volume, and it was in this position he was found, more dead than alive, when the balloon came to the ground.

The captain down below, seeing him stretched across the top apparently unconscious, sent six or eight heavy rifle shots completely through the balloon. These holes considerably accelerated the descent, and the balloon fell much quicker than the rope could be thawed and wound in, and this being like a steel bar, took a circular sweep as the car descended, till it caught in the rigging of the vessel and the car danced up and down as the now half-emptied balloon swayed and bobbed as it slowly collapsed. Finally the rope parted where it had previously broken, and the car fell about fourteen feet, throwing all three of us on the ice. Relieved of our weight the balloon now rose slightly, and began to bump and tumble along the ground in a sickening manner, until it was caught and relieved of its living but unconscious burden. Artificial respiration was resorted to, and in a short time Norris came round, to completely recover in a few days, at which we were very thankful, for his noble and successful effort to save our lives had moved us considerably.

Whilst he was still ill an accident happened which proved of great service to us, although it was only by a mere chance that we were not completely destroyed, for without any warning a large berg close by the ship turned over, and the immense weight of ice below the surface of the water, catching under the keel of the Champion, lifted the vessel up bodily and flung it on the land, as easily as a tennis ball is shot from a racquet, depositing it on the side of the cliff in a V-shaped hollow between two rocks, where it wedged itself firmly, fortunately for us on an almost even keel, as in a dry dock. Many of the timbers of the outer shell had been split, but the damage was only such as could be repaired. The situation had its advantages, as we were protected from the danger of being "nipped" between approaching bergs, although we could not now continue the journey by sea unless we blasted the rock to liberate the vessel, which would have to be done sooner or later in order to return, and would be attended with no small risk to the ship. However, the launching of the vessel was not a question to trouble about at the moment, so we began instead to prepare for continuing our journey on land, so that we could start immediately Norris was fit to travel.

Before we could get the sledges from the hold and fit them up, we were stopped for some weeks by the weather. The sky became dull and lowering, great banks of cloud came up from the west, so Carleton quickly made the vessel as snug as possible, telling us we were going to have a taste of a real Antarctic storm; nor was he mistaken, for very soon there came a lurid light creeping along the horizon, and this was immediately followed by a blast of biting wind, and hailstones falling with the force and feel of bullets. In a few moments the air was full of blinding snow and hail; the wind rose, shrieking in the shrouds like mad fiends, and driving the hailstones before it in solid masses which, falling on deck in one continuous pelt, sounded like the rattle of artillery. It was impossible to stand against it, and one of the men who had been delayed with the tying of a halyard, was flung across the deck to the companion with great force, but thanks to his furs, he only sustained a few bruises.

Day after day the storm continued, gathering in intensity till the whole of Nature seemed to be united in one furious and mighty effort of destruction; peal after peal of thunder followed in such rapid succession that the earth trembled with the reverberation of the deafening crashes. Many a berg, shaken to its foundation by the continued vibration, split and came crashing down to earth or sea, adding its noise to the thunders of the heavens, and all this time the lightning played about the ship in blinding flashes, lighting up the darkened sky with an awful glare. The storm tape had been cast down the face of the cliff, with the ball, in the sea through a large crack in the ice; one vivid flash of lightning struck the vessel in two places at once, and for about the space of a second our good ship looked like a meteor, being completely enveloped in a ghastly blue flame, whilst from every projecting point shot out spears and arrows of light,—a sea of St. Elmo's fire—and then the flexible copper tape absorbed it and it flashed over the side like a fiery serpent, and, running over, split the ice, and the solid floe opened out as if sawn asunder; then it reached the ball, which must have been resting on ice far below, for almost at the same instant there was a muffled roar, thousands of tons of water and ice were thrown into the air in all directions, and there, some fifty yards away, where but a moment ago had been a sea of ice, was now a seething froth of foaming water, with large blocks of ice bobbing and tumbling in the turbulation. A few minutes afterwards ail was compact again, with the insulating tape embedded in the ice.

On deck the wind and the hail were terrible, so severe that the strongest could not have stood against them; momentarily we were expecting the support of our friendly rock to be destroyed, but the vertical wall which rose to over four hundred feet at the far side, and the rock in front, saved us from the fury of the gale to a great extent. When we were thrown on this cliff we thought it a calamity, but to this we owed our safety, or, long before the storm had abated, our boat would have been cracked like a nut between the closing and tumbling ice, or blown to pieces by the wind.

"Beneath I saw a lake of burning fire,

With tempest toss'd perpetually."

— Pollok.

GRADUALLY the storm abated, and with the welcome return of calm weather we were able to complete our preparations for the land journey, and our sledges were stored with provisions for a lengthened absence from the ship. Each of the sledges was fitted up with food, implements, etc., so that should they be separated the occupants could look after themselves independently of the others. Thus the crew of forty were divided into five sections of eight each. Two sections, with one sledge, were left to look after the ship and to gather samples of water, dredgings, etc., in charge of Morgan, the first mate, the remainder going with the three sledges. In order that we could all be in communication, each section was provided with a specially designed wireless telephonic apparatus, all being set in unison. These were wonderfully simple, consisting of the ordinary well-known transmitter and receiver, as universally used;—a dry battery was placed inside the instrument instead of the usual Leclanche—and was for making calls only. Instead of wires, one terminal was attached to a covered flexible copper cord, the other terminal was free, so that the ether waves connected the terminal with that of any other similar instrument set in unison. When speech was required, a ring would cause the user at every other instrument to listen, provided his wire was connected to earth. These could be used at the other end of the world if necessary, for water being a conductor, and much electricity present in the sea, the water would connect land to land and so transmit messages to all instruments set in unison, the world over. The matter was simplicity itself and acted splendidly; the sledges, being made of steel throughout, were in constant circuit with the ground, so that it only remained for us to see that the bared part of the earth-wire always touched some part of its surface, while those in the ship had to take care that such exposed portion of the wire rested in the sea, or on the ground. Thus it will be seen that all five parties could be in communication with each other as easily as if in one house, and one turn of the handle would ring all the bells and bring some ear to each receiver. As will be understood, our invention could not be used privately, as any one at any instrument in unison could hear, so that, when one was rung up, all were rung up also, and all heard the message. We had not perfected this sufficiently to be of public commercial value, although for our purpose it was an advantage to communicate with all simultaneously.

When all was ready, with a hearty leave-taking of the contingent in the ship, our three parties started on our perilous journey still farther south.

We got on very well till we reached Mount Erebus, where we stopped to attempt the ascent. This was exceedingly difficult, as the wind was shifty, and blew the sulphurous vapour in clouds of stifling smoke in which we were constantly enveloped. Some little distance farther on, Carleton found an easier ascent, so all of us gradually made our way to the spot, and by a good deal of scrambling and tumbling, we slowly progressed towards the summit. The volcano kept throwing up hot ashes and lava, which occasionally fell amongst us and required no little dodging. As we climbed nearer the top, the snow and ice ceased and the ground became slippery and dangerous, caused, no doubt, by the condensing steam and heat forming a wet slime of moisture on the rock and lava-covered surface of the ground. Added to this danger were the cracks and fissures in the mountain through which in places oozed white-hot lava, as liquid as water, but so intense was the cold that, after flowing a few inches, it was as thick as syrup, and in still other few inches became slimy and crusted over. Through other fissures issued blue, sulphurous flame and smoke, curling up in endless rings till met by the descending fumes, where they formed strata of unbreathable gas, as if each were trying to overcome the other. With much coughing, spluttering, and holding of breaths, we passed this and then found that in places the ground was very thin, and the utmost care was needed lest our weight should cause us to sink into the furnace raging below. Every step had to be well chosen and tested before proceeding, and after several days of toil we reached the summit, where we all lay down quite exhausted, the last portion having been very fatiguing. We were much surprised at being able to breathe so freely, and after resting a while, we made our way to the mouth of the crater, and, seeking a position free from smoke, looked down what seemed like the fiery gullet of a demon. At the top, or lips, all was black and smoke-begrimed, but a few feet below this the inside became a shade lighter, and thus it changed almost imperceptibly into browns and purples and blues until, about half-way down, the colour became rosy red. Nothing was visible below this, as dense masses of smoke, like billows of rose-tinted wool, were rolling and seething from side to side, now coming upward, now sinking back again, then slowly gathering from side to side like milk on the boil, remaining tranquil for a few seconds and then rapidly mounting up the crater with an irresistible rush, boiling and seething as it came, and as it mounted upwards it became somewhat tinted with the local colour of the crater, first white, then pale rose-colour, then cherry red, and then the crater itself became brighter with the reflection of the liquid mass, which was a very pale red, or orange.

We all stood fascinated by the sight, not thinking of our danger, and still lava came up swiftly and strong, until it reached the top and welled over in a fiery flood, at the same time throwing upwards clouds of white-hot ashes and cinders which seemed to fly out of the liquid like fireworks. AH ran back to the higher ground in panic, with the flood of red-hot lava at our heels.

Down the outside of the crater it fell like a waterfall, but of fire, at least three feet deep, pouring over the edge like golden oil, and immediately the edge was passed, breaking and tumbling into millions of splashing fireworks. The effect was appallingly awful, and all noticed—with a shudder—that tons and tons of this liquid fire were pouring down the very place at which we had ascended, and this would, of course, have been flooding over us had we been but four hours later. Still it flowed on, first red, then rose-colour, and as the lower and still hotter portion was thrown out, the colour became pale orange, and lastly, dazzling white. For several hours it continued to flow on at this white heat, and in the meantime the air had become dry and stifling; over the mountain the thunder and lightning flashed and played continuously, and as we were still watching, in a moment there came a terrific crash, making the whole volcano shake as though attempting to cast us down its awful throat, and the white-hot lava, half-a-mile from where we were standing, suddenly leaped into the air and then vanished. What had happened? We ventured a little nearer and saw that the great heat of the lava, or the pressure, had broken off a mass about one hundred feet deep from one side of the crater, and this had gone tumbling down the mountain side, splashing and being splashed by the liquid fire, leaving a wide cleft or spout in the side of the crater through which the lava now ran in an awful torrent. This deep outlet reduced the level very perceptibly, and it soon ceased to overflow. In half-an-hour the bed of lava between us and the crater was hard, and a little later cool enough to walk upon without injury, so we cautiously advanced and again looked into the pit of liquid fire. The force had evidently spent itself, for the liquid would well up almost to the base of the gap, then rush back somewhat cooled, to mix with that below with a hissing roar, and be again heated to a dazzling white and again thrown up. Thus it continued, becoming less and less strong till nothing could be seen at the bottom but a gigantic furnace of boiling, blinding whiteness. Down this went, lower and lower, as if sinking into the very heart of the earth, when, with the speed of a cannon ball, up came a shower of hot stones and ashes, and the gases exploding and taking fire produced a succession of nerve-shaking reports and flashes which were very terrifying.

We had now seen almost more than we cared for, and the question of getting down began to absorb our attention very seriously. Perilous as the ascent had been, the descent was more so, and we all felt we should be very glad if we went down that twelve thousand odd feet in safety. The places where slopes had been were now ploughed-up masses of stone and dangerous declivities of vertical walls of rock, and where had been friendly ledges on precipitous sides, was now filled up with lava as smooth as glass, with no possible foothold. So difficult were such places to negotiate, that many times, in order to pass some awkward spot, we were obliged to go miles out of the direction and return by another way, after hours of stiff climbing to find ourselves but a few yards lower than before.

Thus, yard by yard, was that terrible descent accomplished, and we finally found ourselves, tired, footsore, and bruised, on the somewhat level base where the three sledges had been left. We had been away about a fortnight, and had had very little sleep during that time, so, thoroughly wearied out, we entered our respective sledges and slept hard and long. Whilst we were asleep another storm came on, but so weary were we that the crashes of thunder even were unnoticed by most of us, except as mingling in our dreams as but the thunder and rumbling of the volcano. When we awoke, we were snowed up; the heat from ourselves and the sledges, however, had melted a wide space round us. The sledges had been placed side by side for additional warmth, and for twenty feet around and above, there was an empty space like a vault, the snow in a straight wall rising high above us, with an arched roof. We had a good meal and slept again and then woke for another good meal, by which time we were thoroughly rested and recovered, ready for a further advance.

We tried to dig a way out, but the snow was too deep, so we set our engines going and moved slowly forward, using our snow-shifters. In an hour or so we came to open country where the snow was still fairly deep, but on looking back we saw that we had been in an enormous drift.

"All that mighty heart is lying still."

—Wordsworth.

FINDING the ground in this inhospitable region too rough for sledging, we lowered our wheels and went bumping along at a pace which proved the excellence of the construction and adaptability of the sledges for what was required of them.

Before leaving the ship we had arranged that however often we should speak with each other, at a certain hour once each day communication should be made between all parties without fail, and as the days sped on and this hour arrived, we gave the exact route and distance travelled and direction of the next day's journey, ascertaining that all hands were well and in good spirits. As we journeyed farther, the difficulties became greater and the country wilder, bleaker, and more storm-riven, and the ground so broken and rocky that the wheels were useless. We now used the vanes and propellers, rising to about fifteen feet above the ground, steering round bergs and prominences without mishap, and settled down at the foot of Mount Terror (discovered by Sir James Ross in command of the Erebus and Terror, 1839-41), which reared its noble slopes to a height of over 10,000 feet We were desirous of examining the interior of this extinct volcano, but on our talking it over with Carleton, he thought it advisable to take only a few of the men, as the experience we had had on Erebus with so large a party had added considerably to our difficulties. It was therefore decided that we four should go, accompanied by six of the men, as we were anxious to explore the crater, even if this necessitated a stay of some days inside it Acting on the wise principle of having considerably more food than was necessary, we took sufficient to last us a fortnight, each as usual carrying his own. We then commenced our climb, leaving the rest of the party with the sledges at the foot, in the shelter of a large opening of one of the rocks, in which they were to wait till our return; Carleton deciding to stay with them, having slightly injured his foot.

It is not necessary to describe our arduous journey, which was very similar to that up Mount Erebus, except that here the snow and ice continued to the very top. We had ascended on the south side, and on reaching the summit found it bleak and severe in the extreme, for we caught the full blast of a gale of wind which had sprung up during our ascent, unnoticed by us in the shelter of the mountain, as it was blowing towards the south, which is usual in these latitudes. So cold was the wind that had it not been for our warm clothing we should have been frozen to death. We were now at about the 179th parallel, and there before us, hidden by that awful barrier of ice, lay the unexplored region of the Pole. We stood looking on the surrounding country, which was bathed in brilliant sunshine, and after taking some photographs, discussed the prospects and probabilities before us. Beyond a comparatively few miles, farther south no man had ever trod; the terrible storms, severe cold, difficulties of food, warmth, and clothing, and lack of means of travelling, had so far prevented man from penetrating very much farther than where we now stood. Should we be allowed to cross the barrier? The question of food, warmth, and clothing had been solved, and even that of transit to a great extent, but when we journeyed farther, should we be as others? or perhaps only be permitted to go just a little more and then, like all who tried to penetrate hidden mysteries, be stopped by that unclimb-able, impenetrable obstacle, as impassable as if a mighty power stood beyond and said, "Thus far shalt thou come and no farther." AH this was in the veiled future; but as we talked, the feeling of a great resolve came over us, and we made a compact together that we would conquer this relentless ice-foe, or die in the attempt, and that come weal or woe we would stand or fall together. Then we gave our attention to the examination of the crater, telling the six seamen to stay at the top and interpret any message sent from the captain, who could be distinctly seen with the glass. Looking inwards the crater went down like a deep bowl; so gentle was the slope that many enormous rocks remained supported on the ice instead of rolling down to the bottom, as one might have thought. We started the descent, walking very carefully, tapping and probing at every step, lest the snow should conceal dangerous hollows. Here and there enormous pieces of rock had been torn from the sides by their own weight, or imperfect balance, and had ploughed deep courses in their descent, thus giving evidence of their weight and power, and leaving the same mighty seal in the holes where they had been partly embedded. There were many of these holes, forming shallow caves, whilst the bottom of the crater far below was filled with the tremendous pieces of rock, some of which were bare and others covered with snow, under which their size could be seen to be enormous.

We had not descended more than one-third of the distance when we heard a call from above, and on looking up, one of the men shouted to us that a hailstorm was rapidly approaching, but scarcely had we turned back when they were all hidden from sight by a blinding deluge of hailstones, which rolled down the side of the crater and pelted us with great force. There being a shallow cave or recess at hand, we stepped into it, and it proved an excellent shelter. Outside nothing could be seen but a sheet of hail which obliterated everything, even the opposite slope.

We made ourselves as comfortable as possible, wondering how long we should be in durance, when all at once Norris, who had been idly scraping at the earth with his spike-shod staff, or alpenstock, energetically exclaimed:

"Look here, Esdaile, here is cobalt, as certain as fate;" and there, sure enough, underlying the rough slip earth, were large slabs of the greyish, brittle metal, cobalt.

Esdaile examined it carefully, and said, "Here is wealth indeed, if we could but take it away."

"Would it not cost more to refine it than the thing is worth?" I asked.

"This needs no refining," said Esdaile. "So far it has been very difficult to obtain cobalt in a pure state, as it usually occurs in the same ores as nickel, and it is an exceedingly difficult task to separate the two metals, but here it is pure, and in tons."

This was an exciting find, and on clearing the earth away we found we were standing on a slab of cobalt as big as a paving-stone. This was rough and torn, and probably the whole rock that had been attached to-it was pure metallic cobalt,—Norris said he would swear it was. In our eagerness we forgot all about the rattling hailstorm raging a few feet away, and inserted the steel points of our stocks under the edge of the slab and, giving a great heave all together, got one end partly up and saw that it was about eighteen inches thick, all solid metal, when it slid back again, too heavy for our poor leverage. We tried it again, and just as Belt got his stock under it the whole floor gave way, and down we dropped all in a heap on to something solid, and then slid down an inclined hole for a great distance, finally pulling up, after another big drop, against a mass of earth. The light from a match showed nothing more than a hole, which must have been a kind of shaft, or vent, through which the gases had escaped in the time of the volcano's activity. There was no other way out, so we tried to climb up, but the sides were rock and the inclined earthy vent down which we had slid was far too high to reach; we were also badly bruised, and Norris had severely hurt his wrist, either by falling on it or catching it somewhere. There was not even a glimmer of light, and from the distance we had fallen we must have been a long way below the bottom of the crater, or what we had supposed was the bottom. We were unable to find a foothold anywhere, although we tried till we were weary and exhausted; so we sat down to rest, as effectually caged as in a trap, and without any apparent means of exit or communication with our friends outside.

"It is getting warm," remarked Belt, at the same time sliding his mask into his hood.

"So it is," agreed Norris, following his example; "but it is strange the air is so fresh and sweet; I should have thought that in this hole, closed up as it was, the air would have been deadly."

"Where can it come from?" said I. "Shall we see which way it blows a flame?"

So we tried a match at a time in various places, and in the rocky wall, nearly at the bottom, by the crevices of several slabs of metallic cobalt, the flame was wafted aside, drawn inwards—so the air passed out there. Economizing light, although each had a box of matches, we felt round for our stocks, and inserting them in the cracks and fissures, the earth all round was cut away and the slab pulled back. A great hole was revealed, which the light from another match showed partly blocked up. We scrambled through and could now feel a perceptible current of warm air, and it was quite evident we were either nearing the source of some volcanic heat, or else the extreme cold above kept the natural heat of the ground from escaping, and so it remained comparatively warm, and also gently warmed the air passing through it. On and on we went for several hours, when we called a halt and, sitting down close together, talked over the situation.

"And in the scales on either hand

Sat life, and death—in equipoise."

—Giranoli.

ON looking at a pocket compass, we appeared to be going due south, but it was now getting warmer, and already our "Tynstele"-lined furs felt uncomfortably hot and heavy. Each sat thinking, and after a few seconds I said—

"Do you hear anything? I fancy I can hear running water."

We all listened intently, and could hear a faint sound of water some distance off; we now started again, and as we continued our journey, the sound became more and more distinct, till we at last came to a swiftly flowing river.

"Now," said Belt, "how are we to cross this, or tell how wide it is?"

"That is the difficulty," said Norris; "I fear it is both swift and deep. I have seen a good number of these subterranean rivers, and this flows as fast as a mill-race."

I put my stock in, but it went deep down, and the current ran so fast, that I could not hold the stick straight down, even with both hands. We flung in a heavy stone, but so strong was the stream that we distinctly saw it fall flat on the water and swept almost across the tunnel before it began to sink.

"No one can swim that stream," said Esdaile, "but we must cross it if possible, or die here. You hold me, Tony, and I'll try to stretch across."

With that I gripped him by his hand and wrist, and the others held me, when he stretched across with his stick, which fortunately touched the farther bank; considering the length of the stick, which was six feet, the stream would be about seven feet wide, so that it was possible to jump across with a run.

"It will be a dangerous jump to take," said Belt; "it would be bad enough in the daylight, knowing the bank at both sides, but in this narrow passage, where one can scarcely stand upright, it is no joke to jump over that flowing death on to something no one knows what."

"I am afraid it will be a bit tricky," said Norris. "Let us make a good light and we may perhaps see the other side; we can feel it with the stick, but how are we to tell if it is the far bank or merely a rock in the middle of the stream, or even if there is an opening at all beyond?"

"It is more than probable," said I, "that the passage ends where we are; you remember the lights have all been drawn inwards, and this may have been caused by the suction on the air by this very stream in its swift rush past the opening."

"That is a point, certainly," said Esdaile; "the first one across may reach safety, but my own idea is that it is but a rock in the middle of the stream, for there is empty space above and at each side, and my opinion is that we shall alight on a slip of rock and go bounding into the stream at the other side, or else go smash into a blank wall of earth, or rock, and into oblivion in either case."

Now we had a quarrel as to who should go first; each insisted on trying it, but none would give way, or agree to lots, so matters were at a deadlock, but to stay where we were would eventually mean death; the same result would follow going back, or attempting to swim the stream, and so we again tried with our sticks from all points, to find that in only eighteen inches or so was there anything to be felt on the opposite side of the river. Could we, in a running jump, in the dark and bent nearly double, gauge to a nicety eighteen inches of rock, the height of which could not now be ascertained, and this across seven feet of black water, flowing with irresistible strength and rapidity? It had to be tried, however, and then began another quarrel. Norris insisted on going, but he had risked his life for us in the balloon, and we were all fully determined he should not do it again. I insisted, because I was a good athlete, but all the others objected; I opposed all the rest, and so it went on all round. At last we agreed to draw lots, refusing to let Norris join in it, which made him very angry, but we all positively declined to do anything if he risked being drawn. Then he became sarcastic, and said it was a pity we had not brought with us his feeding-bottle, or a glass case to put him in, but we drew lots without him, and the lot fell upon Belt.

We had each brought a rope, to assist us in climbing the mountain, and after we had stripped, one of these was tied round Belt's waist, the other end being held by two of us, standing at the water's edge, thus giving him plenty of slack. He tied a box of matches on his head and then said he was ready; Norris held several lighted matches aloft, whilst Belt gauged the position of the rock, time after time going backwards and forwards to be sure of the exact direction, and then with a "Good-bye, all," the final run was taken. No one saw what happened, but there was a splash, and the rope dragged taut; in a moment, just as we were commencing to pull back what we feared would be our drowning comrade, there came a shout—

"I've got it! I'm all right; the passage continues here at this side."

The slack of the rope, which had fallen into the water and had been instantly carried away, was dragged straight, and a few seconds after we could see Belt at the other side holding a light, which plainly showed the mouth of the continuing tunnel. Between rushed the racing stream, terrible in its blackness, with the feeble, nickering light across its surface. Norris and I then passed over, and Esdaile made a big bundle of our clothing, etc., and we jerked it across; then he followed, landing safely amongst us. Thus we had performed a series of athletic feats under the instinct of self-preservation, which would scarcely have been possible otherwise. We now dressed, but as the air was so warm we strapped our furs in a bundle, and then, feeling the reaction after all our excitement, we decided to stay here and take advantage of the water to prepare a meal We carefully wrapped a cube of beef and a tablet of potatoes in a large cloth with which we were provided for the purpose, and tied this securely to the rope, throwing the bundle into the stream for the food to soften and swell. Meanwhile we sat down; most of us fell sound asleep, at least I did, but the others only confessed to having "just dropped off." Hauling the food back, we made an excellent meal, though a cold one, and then, much refreshed, recommenced the journey, wondering what it would lead to. We were going along carefully in the dark, as our matches were precious, when Esdaile suddenly exclaimed—

"I thought I felt some one pass me. Was it one of you?"

We all said "No"; but Norris said, "I also thought some one passed me."

"There!" said I, "some one has passed me now. We are not alone;" and I struck a match, but the light revealed ourselves and our black shadows only.

"It Is very strange," said Belt; "I am sure there is somebody about, I can feel their presence!"

So could we all, but nothing was visible, although we all had the feeling that we were passing through crowds of people and were being watched. We felt about, and kept saying, "Now I have you!" to find it was but one of ourselves. This sensation of strange presences grew stronger as we proceeded.

"This is a bit uncanny," said Esdaile. "The place is weird enough, and mystery does not improve matters."

"It is just as though we had actually crossed the dark, swift stream of death," Belt remarked, "and immediately on reaching the other side, entered the abode of the shades, who would, of course, be invisible to mortal sight."

"That is poetic, anyway," said I; "but this goes beyond sentiment. I do not believe in shades myself, but no one can doubt that there is life about us."

This impression continued, but there was nothing for it but to proceed; we had roped ourselves together lest we should become separated, for the tunnel had taken so many turns, and had been crossed by so many other tunnels, that we had to confess ourselves hopelessly lost. At the start, we each had a box of matches, but all had been used except one boxful, therefore we dared not use these for lighting our path, or they would have been used up in an hour, so we went blundering on the rough and heavy way, first upward, then descending, till we were bewildered. Even the compass was no good, for we found that some of the rocks at the side were magnetic, and deflected the needle so much as to prove it quite unreliable. We had crossed the river and started the journey in a spirit of reckless daring, and bitterly regretted we had not waited, for now, when too late, we felt certain that search would be made for us, as the sailors would probably have seen where we had sheltered. Time after time we turned back, to find we were in a cul-de-sac, so that we had now lost all idea of direction and had no alternative but to proceed along the tunnel to wherever it might take us.

We travelled on for some days, coming across many springs, which always abound in the interior of the earth, and in these we prepared our food, but in spite of our having plenty, we were becoming terribly exhausted, both in mind and body, but suddenly, to our intense relief, the passage opened out and we found ourselves in a large cavern. There was a faint, glimmering light from one point, which was very pleasant to see after groping in the dark so long, though we could discern very little by its feeble ray, except that we seemed to have descended into a graveyard, or underground cemetery, for there were many apparent tombstones lying about. We struck a light, and found that what we had taken to be tombstones were masses of lava, and, looking up in the direction of the glimmering light, we saw innumerable stars in the sky, high above, but the dark rock all around was so smooth, and shelved inwards so much, narrowing as it approached the top—an immense distance above—that only a fly could have climbed it. Norris at once pronounced it the empty crater of an extinct volcano, and remarked on our luck in descending into this, instead of into the open arms of an active one. He said that the passage we had come down was therefore only an air-shaft of this volcano, communicating underground with the crater of Mount Terror, and the many openings with which the crater abounded were merely vent holes through which the lava had been tapped from various places in the earth, all culminating in the chamber where we stood, from which the volume of liquid fire would be thrown up out of the crater above. The compass was still useless; in fact it pointed north in five different directions; our watches were also magnetized and had stopped, so that we were in a double plight, knowing neither time nor direction. We traversed various passages, sometimes for what seemed hours, only to meet choking, sulphurous fumes, which drove us back to the cavern, and it seemed as if we had now reached our last resting-place. It was quite evident we were near some volcanic matter, which was not sufficiently great in volume to well into the drains, or channels, and so forward into the crater.

Many days were spent in wandering about, trying to find a way out, and our stock of food was now perilously low. One meal a day was all we allowed ourselves, but in the darkness, without knowledge of time, we feared we were exceeding this limit, so that we must find a way out somehow, and soon, or face death by starvation. At last, in searching along the many passages, we entered one where the roof had fallen in, blocking the way farther, but before the match-light failed, something in the nature of the soil struck Norris as familiar. He took a handful of it, and lighting another match said—

"Look here, Tony, this looks like that edible earth we saw those Russians feeding on and ate of ourselves. Don't you think so?"

I took some, and even in the hurried glance saw there was no mistake, and replied, "Yes, I am quite sure of it," then, turning to the others, continued, "When Norris and I were travelling in Northern Russia some years ago, we were without food and, coming to a small village, found the peasants also without, but they were eating a kind of earth called rock flour, and this is the same."

"How do we eat it?" asked Esdaile.

"It is mixed with food and roasted, and then eaten," said Norris.

"But how are we to roast it?" asked Belt; "it would take all our matches to make a fire, and we could not get one big enough to even warm it."

"That is not really necessary," replied Norris. "We can mix it with our potatoes, which we can crush up into meal, and it will keep us from starving, for when the potato-meal is finished, we can use it alone, and at the least, it will keep us alive."

"That's something to be thankful for, anyway!" said Belt; "but I for one shall only eat it in extremity. I have heard much of edible earths, but never saw any before."

"It is quite common," answered Norris; "when in a state of famine or distress, people in many countries eat certain earths as food, some raw, others cooked, and some alone, or mixed with other food, such as flour, to make it last longer."

"Yes," said I; "it is common enough amongst the very poor. In Spain there is a particular kind of earth called bucaro, very largely eaten; the Hindoo eats his patna earth; the Persian, gheli giveh; the Swede, bergmehl; and so on in many countries."

We tried a little, mixed with potato-meal, and found it of a dry, muddy flavour, and extremely satisfying, but we were bound to confess that our small supply of meal would last a long time, when largely admixed with this new-found food. Each taking as much of the edible earth as he could carry, we proceeded along another passage for a considerable distance, and were just talking of resting, when there came the faint sound of knocking close by. Having located it to come from behind one of the walls of the passage, we tried to make a way through, but it was solid rock.

"Look here, you fellows," said Belt, "if this rock is thin enough to allow of sounds being heard from one side, they can also be heard from the other. Let us hammer at the rock and all shout together."

This was an excellent suggestion, and we set to work with a will, yelling ourselves hoarse and making the whole tunnel echo. After what seemed hours we felt bits of earth dropping around us, and the rock seemed to move slightly, to our inexpressible relief, as we were now too hoarse to shout. Moving aside, we felt and heard the rock crack, and saw thin streaks of light showing through the crevices. These got broader and then, with a crash, the stone was broken right across and fell inwards, we ourselves being almost blinded with the blaze of light pouring through the opening, which went from the roof to the floor of the passage we were in.

"Wie das Gestirn ohne Hast, ohne Rast

Drehe sich Jeder um die eigne Last."

—Goethe.

WHEN we recovered from the blinding glare we saw the heads of several people peering through the opening, their faces expressing the most profound astonishment. We stepped through the gap and were amazed to find ourselves in the midst of some mighty works. On all sides were vast machines and what seemed to be presses and stamps, with hundreds of exceptionally fine men working at them, while from the roof and walls shone a steady, even glow, like a fluorescent screen greatly magnified. The few people who had broken the way through stood surprised, yet expectant; so Norris asked them where we were, in English, French, and German, but was not understood. Belt asked in Greek, which they seemed to comprehend, for one man replied in that language, but the accents fell so differently, Belt could make nothing of it; I then spoke in Latin, which we all understood, and promptly came the answer—

"This is the City of the Sons of Earth."

"Do you speak any language other than Latin?" asked Belt.

"We speak but one language," the man replied, "although we do not know it as Latin. Come with me, and I will take you to our master." So saying, he led the way forward, we all following, very much impressed at the sights which met our gaze. Although, as we found out afterwards, we were in an underground city, we were not at first aware of the fact, as the beautifully soft, yet strong light which permeated everything looked to us like actual sunshine. The people were clad in vestments of an exquisite shade of pink, with just a tinge of purple in it, bound round the waist with some kind of metallic belt skilfully twisted from strands, and as soft and pliable as silk. These belts were tied in a loose knot, and hung down to the knees; around the neck was a single chain of the same metal, shining like platinum; they wore sandals and moved about with stately grace. Those who were actively employed wore a sort of blouse, or pinafore, over the clothing, and these were drawn together at the wrists, as if threaded with elastic, thus leaving the people the unimpeded use of the arms. Our guide, although an ordinary workman, was highly enlightened, and had a far more profound knowledge of electricity, geology, and the sciences than we ourselves had ever hoped to possess, specialists as we were considered to be in our respective branches. After walking a matter of fifteen minutes, through some of the finest streets imaginable, we arrived at the stately entrance of a building cut out of metallic cobalt, the greyish-white metal scintillating in the light in a most curious manner. We were ushered into the presence of a venerable-looking man, who received us with the courtly grace and quiet dignity which prove a cultured mind. On our guide explaining the circumstances of our arrival, the venerable leader said:—

"You are the first strangers who have visited us, and I shall be pleased to know whom I am addressing, since we have no one to whom we may look for introduction."

Belt answered, "We are explorers sent out from England to penetrate the regions of the extreme south, and if possible to reach the South Pole. We accidentally fell down the crater of an extinct volcano, and have been wandering amongst the caves under it for several weeks. We despaired of ever getting out, and expected soon to die of starvation, but we heard your people at work and they liberated us."

"You are welcome to our city," said he, "which we call the City of the Sons of Earth; I am the official head, and my name is Antistes. But I see you require rest and food, so we will talk together later;" and so saying, he gave some instructions to an attendant, who then conducted us to another apartment. On our way Esdaile asked if we could have a wash, as we had only been able to wash ourselves very indifferently in the springs we had passed. He smiled, and brought us to a room containing large bowls of crystal, or clear stone, which he filled with excellent water, and we simply revelled in it.

After this we passed into another apartment, which was handsomely furnished. At the door was some magnificent metalwork, saw-pierced in a wonderful and intricate manner, and this extended around and beyond, straight up to the ceiling, forming a vestibule. Having passed through this, we stepped on what appeared to be a tiger-skin rug, but of enormous size, covering the greater part of the floor. It was soft and thick, but on lifting the edge, which we ventured to do later, we found it made of glass, like woven glass wool, woven or stained in set pattern. Instead of chairs were thick cushions like wool-sacks, soft and delicate as silk and eiderdown, also made of woven glass of exquisite colour and design. The table also was of glass or vitrified earth or stone, and had the rich and wonderful variety of colour and workmanship of our best Venetian glass. On this stood four blown-glass vessels, of such richness and value that any one of them would have sold for sufficient to have made all our fortunes; and in the centre a tall goblet, with four handles, formed of a youth and maiden alternately swinging on the rim by the hands and throwing the body outwards, so that one or both feet rested by the toes against the body of the vase, around which were other figures in splendid design. We had never before seen such a work of art, and its value in our world would be priceless. We all took our seats, wondering what we should have to eat, for beyond the central goblet, which was filled with water, and the four drinking vessels, the table was bare. The attendant filled our glasses with the sparkling water and desired us to commence.

"I think we should be glad of something to eat first, if you do not mind," said I, dubiously, conscious of sundry messages coming from under my waistcoat, and feeling we ought to say something, when he replied, "This is our only food."

"Great Scott!" cried Belt; "do you mean to say we cannot get anything to eat here?"

"Only this," he replied; "we take nothing else, and if you sip it slowly and chew it, you will find it both meat and drink."

We very much doubted this, but could not do otherwise than accept his statement; so without the slightest excitement or hurry we commenced our frugal repast, which tasted very thin, although of delicious flavour; but by the time we had drained our glasses we felt as satisfied, except in taste, as if we had been dining on steak, which caused us no little surprise. During the meal we could not help noticing the splendid bearing of the attendant, who had not the servile manners of a lower-class, or the arrogant effrontery of an upper-class, servant. Instead of this, his manner seemed more like that of a host towards his guest; there was an air of quality about him which was felt rather than seen, and he engaged the four of us in conversation on many scientific subjects, which he entered into deeply. After the meal was over he said "The worshipful master, Antistes, wishes to have conversation with you," and so preceded us to another apartment, where there were more seats, similar to those we had already used. We gazed about us, and found it difficult to realize that we were underground, as all was as light as day; the walls and ceilings were covered with choice frescoes, chiefly of allegorical subjects, which we could not understand, and which shone out as if painted on silk and seen with a strong light behind them. We drew up to the wall and closely examined them, to find they were really mosaics, but could not understand how this wonderful effect was obtained, unless the mosaics were some iridescent light-producing metals unknown to us.

In a few minutes Antistes came in and sat down beside us, when Esdaile gave him a detailed account of our adventures. At the mention of our difficulty at the river, Antistes asked the kind of river, where it was, and if we saw any one.

"I was just about to state," continued Esdaile, "that after crossing this river, we felt that many people were round about us, but saw no one."

"It seems to me a most remarkable thing," said Antistes, "that you, in your present life, should have been permitted to travel there."

"Why so?" asked Norris wonderingly.

"I will explain all shortly," said Antistes, "but I will first hear your story."

Belt then took up the narrative and told of the second crater, and the finding of the edible earth, and how, coming to the sound of knocking, we also had knocked, and been liberated.

"I had no idea we had gone so near the tunnel," exclaimed Antistes, "but this district was at one time very volcanic; in fact, in various places now there are live volcanoes, and the whole earth about here is intersected in many places with old, and active lava-drains, terminating in some crater."

"Do you cut into many?" I asked, thinking it was my turn to say something.

"Oh, yes," he replied, "we cut into them and block them up."

"But when you cut into a live one, how then?" asked Belt

"In that case we should know it was active long before we got near enough to break through, and leave it alone, or strengthen the walls."

"But are you not afraid that the extinct ones may again become active," asked Norris, "and flood your city with molten lava?"

"That is impossible," he replied, with a smile; "one might become active again, but it would find a fresh outlet and not touch us."

"How can you guard against it?" asked Esdaile, in surprise.

"The feeders of a volcano are like the roots of a tree; they draw the lava from all directions, and this runs along till it all settles in one vast chamber, or core, from which it is ejected above. It will follow the line of least resistance, and when we break into a passage, we make the resistance so strong round us, that it would be easier for the collecting lava and gases to go anywhere than near our city and its ramifications, so that we are perfectly safe."

"What is this resistance you use," asked Norris, "that is strong enough to turn the gigantic forces of a volcano?"

"Have you begun to use any natural force in your country which is powerful enough to give light?" asked Antistes, directing our attention to the walls around by a wave of his arm.

"Do you mean electricity?" asked Esdaile.

"Here we call it life," said Antistes.

"How do you generate it?" asked Esdaile.

"We do not make it," he replied; "it grows, it exists, it is and we gather it to use as we want it."

"We on the earth above," replied Esdaile, "almost all over its surface, know how to get but not what it is, or where it is."

"The you have much to learn, and if you can stay, I will try to show you not only what it is, but where it comes from, and how to draw and us it."

"We would gladly know that," replied Norris, "for we are children in these matters."

"We shall all be grateful for any knowledge we can gather, and also if you could help us to get to the extreme south," said Belt, eagerly.

Antistes at once became very serious and said, "I fear you will never do that. Long ago, in ages past, we were forbidden to cross the barrier, and, as obedient children, no one has ever attempted it."

"What barrier?" asked Esdaile. "The barrier of ice?"

"I do not know," he replied; "all I know is, that somewhere not far from here is a forbidden and dangerous district, and our records tell us it is a deadly sin to attempt to pass it. Although we have no fear of what you call death, to deliberately commit an act of wilful disobedience would be to us impossible."

"Circles are praised, not that excel

In largeness, but th' exactly framed;

So life we praise, that does excel

Not in much time, but acting well."

—Waller.

SO serious and reverent were his tones and manner, that no one spoke, and after a slight pause, he continued, "Here, you see, all is warm and equable; there are no storms, strife, or distress, and we are content."

"How comes this warmth?" asked Belt, "and how are you free from distress?"

"The warmth comes from the heat of the surrounding volcanoes, but they are not dangerous to us, as this' life,' which you call electricity, surrounds us as with a shield and nothing can harm us," he replied.

"Do you mean that no accident, illness, trouble, or anything else can harm you?" asked Belt, incredulously.

"Yes," he answered; "nothing can do us the slightest injury unless we deliberately willed it. That you will learn to understand if you stay with us."

"But what is there to hinder our going south?" persisted Belt.

"I will tell you the story as we have it," said Antistes. "Long ago, the lord of life created beings and made them immortal, body and soul. He intended founding a race of gods, and told them not to do certain things, or their bodies would die and they would lose their god-like aspect. They disobeyed his commands, so he turned them out of their lovely country, lest they should discover the great secret called 'life,' for if they did, they could have even defied their lord and made their bodies live for ever. Thinking that in time they might even try to force a way into that lovely place, and steal some of this 'life,' the lord built a barrier all round it, and made It so cold and bleak and desolate that no creature could pass it: so these people who had broken their master's law and spoiled his work, were obliged to go farther and farther away. It is said that so long as this world lasts, no living creature shall ever pass this awful barrier and see the beautiful place beyond. And it is also said that if it were possible for any one to pass it and even view this secret of life, they should never know it, for the mere sight would blast them where they stood, and, in the mere glance of 'life,' they would find a horrible death, its very brightness being their doom."

"Perhaps you are right," said Belt; "many explorations have been made to the north pole, and with considerable success, but with the south pole it has so far been very different."

"Yes," said Esdaile, thoughtfully, "it really seems as if this awful, storm-riven, inhospitable country was arranged so, in order to prevent all explorations beyond."

"Well, we will try it!" exclaimed Norris, "or die in the attempt."

"Nay, try it not," said Antistes, warningly. "To those who would penetrate the mysteries of the divine, and try to force into the secrets of the infinite, disaster comes."