RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

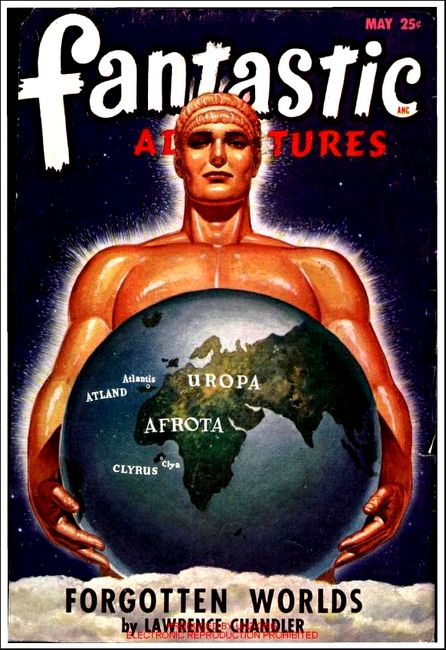

Fantastic Adventures, May 1948, with "You Bet Your Life"

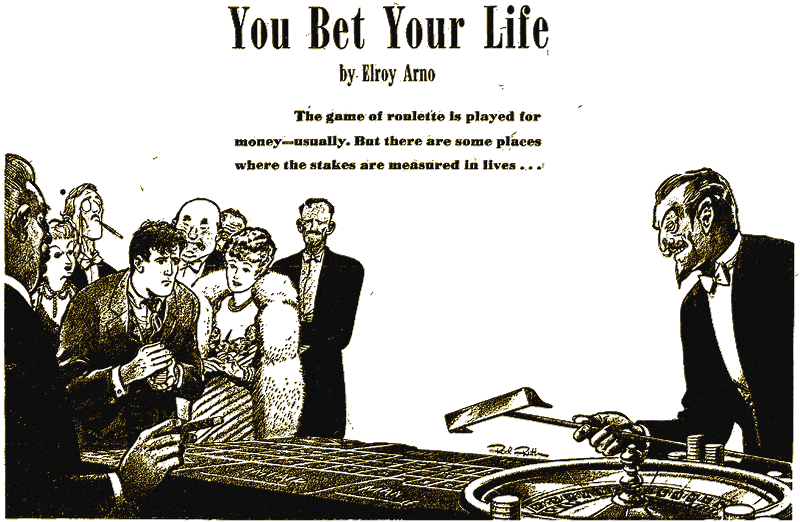

Ross Chaney stood for a moment, watching the croupier apprehensively.

ROSS CHANEY hesitated, the fifty-cent piece still between his fingers. His hand started to shake. He stared with narrowing eyes at the dark-faced croupier. He felt goose-flesh creep up the back of his neck.

"Say that again," he invited. His voice wasn't very steady.

The croupier's face remained expressionless.

"If you don't win sir," his voice was cold and impersonal, "Your body becomes my property."

The meaning seemed to sink into Chaney's brain slowly. He turned pale.

"You mean that if I win I'll take fifty thousand bucks for my measly fifty cents. If I lose, I'll—"

"You bet your life, sir, so to speak. If you lose, you no longer own your body."

The dim, deeply carpeted room was silent. Half a dozen carefully-dressed men were grouped at Chaney's back.

Suddenly Chaney knew that they were trying to make a fool of him. He, Ross Chaney, the poor class-mate, invited to the Millionaire Club to play the part of a sap. He turned on the others, his eyes blazing.

"Look here, what kind of a gag is this? You sponsored me to become a member. If this guy is being funny, I don't like it."

He saw only serious, unsmiling faces. It didn't seem to be a joke to them.

"Ward," Chaney begged, "What the hell is it all about?"

Ward Talmud stepped out of the group and faced the bewildered Chaney. Talmud was a stout, well fed little man with three chins and a pale clammy-looking face. He tried to smile. He put a comforting hand on Chaney's shoulder.

"I'm sorry, Ross," he said, "But this is all on the level. You've been after me to get you in down here. Now you know why the Millionaire Club exists."

Ross Chaney gulped.

"You mean to say that, this is where the money came from. The money you and the other...?"

Talmud nodded.

"There used to be a gambling casino in this building," he said nervously. "We took over the space when they went out. The law caught up with them. At first we called it the Local Yokel Club. Then," he nodded toward the croupier, "he moved in, Ross, I didn't tell you to come into the roulette room. Usually we break the hews gently to new members. You don't, have to play. The stakes are so high that most of us feel we are forced to take a chance."

"But he, you call him," Chaney turned to stare at the croupier. "What's his game? Where does he come from?"

Talmud shuddered.

"Ask yourself who would have access to all the money he needs. Who would force men to sell their souls for one twist of the roulette wheel. You have an answer."

Chaney shook his head.

"I'm sorry," he said, "But it's too fantastic. Why don't you stay away from him?"

The croupier uttered a short, bitter chuckle.

"Because," Talmud said, "we are human. Show me a man who won't risk everything for a fifty-fifty chance at a fortune."

Ross Chaney didn't want to believe what Talmud said. He couldn't believe that the agency behind the wheel wasn't human. He looked at the gambler and the man grinned back at him, lips parted evilly. He bowed slightly as though saying:

"I am Satan, sir, at your service."

Chaney looked quickly at Talmud. "The rest of you have been lucky," he said.

Talmud nodded.

"All but two." He shuddered. "Bill Tower and Shorty Walker bet on the wrong color. They—disappeared. Maybe they just left town," he added hurriedly.

CHANEY looked again toward the croupier.

"You bet your life, sir: Will it be red or black?"

Chaney grinned crookedly.

"Have you ever been broke and out of a job? Have you ever tried to fit in with a crowd that throws away more dough in a week than you ever saw before?"

The croupier didn't answer him directly.

"What do you think, sir?" he asked, and pointed at the wheel.

Chaney swore. Most of them were lucky. They owed their fortunes to a twist, of this wheel. It might be a joke. Perhaps they greeted all newcomers this way.

Ward Talmud had brought him here, and damned if he, Chaney, would make a sap of Talmud.

He dropped the fifty-cent piece on the table. It spun around, rolled a foot and dropped on Black 22.

"Take your pound of flesh," he said in a low voice; The croupier chuckled. He leaned forward and spun the wheel. He dropped the ivory ball on the edge of the wheel and it started clicking around swiftly.

Chaney stared at the wheel. It was like watching someone else lose or win. He couldn't believe that it was actually he who was concerned. The wheel moved slowly. He could feel the warm breath of the men who gathered close behind him. The croupier's eyes were not on the wheel. They were burning into Chaney's face. Chaney wasn't excited any more. He was cold all the way through. He felt no emotion. His arms and legs seemed separated from his body.

"Good Lord," Talmud whispered. "Black 22."

It was true. The ball had not only stopped on black, but it had stopped on the exact number he had chosen. Even Chaney knew that such luck seldom touched a man.

He stood up. He forgot now that his own life had been at stake. The others were forming a barricade between him and the croupier. He was glad, because he looked up. The croupier's eyes were cunning. Like two red-hot coals.

He pushed a stack of money toward Chaney. Chaney picked it up and stuffed it into his pocket. As he did so, his eyes fell once more on the roulette table.

Somehow, after they had looked away, the ivory ball had bounced once more, from Black 22 to Red 34.

He had to do something about it before the croupier saw the changed number.

He pretended to fumble the roll of money and a fifty dollar bill fluttered to the floor. Chaney leaned forward, hit the table and the wheel jarred around a few numbers.

"Greedy man," Talmud said without humor. Chaney managed, to pick the fifty up. With shaking fingers, he tossed the fifty to the croupier.

"Use it to light your fires, if you ever light fires."

"That's a little old fashioned," the man said, and smiled. "I'll be looking forward to seeing you often, Mr. Chaney."

Chaney was able to smile once more. "See you in hell," he said, "and I hope not for a long time."

He turned and followed his companions into the bar. The roll of money in his pocket felt comforting and powerful. Ross Chaney had plans.

CHANEY leaned back in his chair and placed both feet on top of the desk. He stared in an amused manner at his younger brother.

"I tell you, Johnny, this play-boy stuff isn't half bad."

Johnny Chaney stared down at him, standing stiffly near the other side of the desk. Johnny held his cap in his hand. His face was almost as red as the mop of uncombed hair. Johnny ran a gas station on the South Side and he pumped more gas than any other attendant who worked for the company. He made thirty-five a week and was damned proud to get it honestly.

"But Ross," he protested, "You got things all wrong. I don't know where the money comes from and it ain't none of my business. It's this office, and you staying away. Mom wants you to come home."

Ross Chaney chuckled. He leaned forward, opened a box on his desk and removed two Havanas. He passed one to. Johnny, who took it mechanically and pushed it into his cover-alls.

"You ain't a bad kid, Johnny," Ross said. "Maybe I can show you how to pick up some of this dough. Like to get your hands on it?"

Johnny's good intentions did a nose dive. He had come strictly as an upright member of the family to plead with a brother who had, according to Mom, "gone wrong." Johnny's eyes started to shine. He looked around at the huge forty foot room and the rich dark wood of the furniture.

"It ain't crooked?"

Ross shook his head, mimicking Johnny's squeaky voice.

"No—it ain't crooked." For an instant he looked serious, then smiled as he thought how easy it would be to make the family rich. "With me along for a lucky piece, you can't lose."

"But you gotta have money to make money," Johnny said. "That's the first rule."

"In this case,".Ross said dryly, "You need fifty cents to make fifty thousand bucks. You got it?"

Johnny was thinking about all the gas he'd pumped to save a thousand smackers.

"But—how in heck...?"

"Roulette," Ross answered quickly. "One spin at the roulette table."

He stood up. He wasn't sure, what the kid would do if he knew, what the odds were. Better not tell him until it was all over.

Ross Chaney was sure of one thing. He had faced the roulette table twice now and won. The second time he won fairly. Johnny couldn't lose if he stayed under Ross' wing.

"What d'ya think Mom would say?" Johnny asked. "She'd get mad if I gambled."

Ross scowled.

"You're nuts," he said. "A chance to win fifty-thousand and you're spouting goody-goody."

Johnny looked worried.

"I ain't taking no chances?"

Ross shook his head.

"You might lose fifty cents," he said sarcastically. "How can you lose any more?"

Johnny grinned.

"Guess I can't," he admitted. "Gee, Ross, you're a swell guy!"

"I sure am," Ross admitted. "Come on kid."

JOHNNY CHANEY took two spins at the wheel. He quit his job and bought out a chain of service stations on the West Side. Johnny got tired of the desolate poorly furnished house on the south side, moved out and rented a nice place on Ashland Avenue. Johnny was doing all right. He'd probably take one more swing at the roulette table, then quit. Too much money wasn't good for a man.

THE ragged little man with the black patch over one eye stopped Ross Chaney as he came out of the Millionaire Club. Ross was laughing loudly and flourishing a burning five-dollar bill in front of his companions. To the little man with the eye-patch they looked half drunk, and therefore fair prey. He doubled himself up, groaned and shuffled into the center of the group.

"Spare a quarter for a bite to eat," he sniffled. "Just a quarter, gents. That ain't much for gentlemen like you."

Ross Chaney applied the burning fiver to his cigar, sucked the smoke in-deeply and tossed the burning bill on the pavement. For the first time the man with the patch seemed to realize that Chaney was burning money. He stared down at the ashes of the bill.

"My God, sir..." He looked at Chaney. "You're nuts, that's what you are."

Chaney chuckled. He had just taken his tenth whirl at the wheel. No one could stop him now.

"Give the bum a few bucks, Chaney," Ward Talmud said. "You cleaned up again tonight."

Ross Chaney stared down at the pinch-faced bundle of rags.

"What's your name, Bud?"

Somehow all his money had given Chaney a permanent sneer. He tried to hide it, but he was forced to look down his nose at the poor saps who didn't have plenty to spend. Chaney was living high and no one could knock him down now. He was so high that no one could reach him.

"Peter Squab," Patch-eye said.

Chaney looked serious.

"Well, Pete," he said, "you come with me and I'll make you a fortune."

Peter Squab looked, doubtful.

"You're kiddin' me sir. You ain't got a right to kid...."

He stopped. From the look of the others around him, Peter Squab knew he wasn't being kidded, at least not like you'd expect. He stood very still, staring at Chaney. Chaney was waiting.

"You were lucky with your brother, Ross," the little fat man said. Peter Squab had no way of knowing what Talmud was talking about.

"I'm always lucky, Ward," Chaney said. "And if I wasn't, what difference would it make. No great loss."

He looked at the bum and saw only a useless, shivering sack of bones.

"Well," he shouted. "Fortune or no fortune, what do you say?"

Squab tried to grin.

"I'll take all you got to give, mister," he said. "Lead the way."

The crowd parted and Chaney went back into the softly lighted club entrance. Peter Squab removed his hat, smoothed his hair with a rough hand and followed. The light blinded his eyes.

Ward Talmud said:

"Jeez—it's just like Chaney to make it stick. I never saw such luck. If he don't slip pretty soon, I'm going to take another crack at roulette myself."

They stood close together just outside the door. The wind grew colder. Fifteen minutes passed. Talmud kept looking at his watch.

"I got a feeling...."

"No, wait," someone said. "Good God, Ward, they're coming out, both of them."

Talmud whirled around. They were. Chaney led the way, a broad, self-satisfied grin on his face. Rambling along behind him was Peter Squab. Squab held the money in both hands, staring down at it unbelievingly. Chaney came out into the night, held the door for the unseeing Squab, and chuckled. He looked at Talmud.

"Another rich citizen, thanks to me," he said.

Peter Squab had forgotten that the others existed. He stood close to the door, leaning against the building out of the wind. With shaking fingers he tried to count his pile of money. Once a bill fluttered to the ground and Squab pounced on it, muttering under his breath.

He looked up and caught them staring at him. Peter Squab grew tense.

"It's mine," he said. "My money, understand? You can't have any of it."

Talmud, chuckled.

"Seems to have upset the old cootie. Maybe someone better show him how to hide it so his buddies won't take it away from him."

Squab held the roll close to him.

"No one ain't taking nothing," he snarled. "You stay the hell away from me."

He backed away from them. A safe distance from the group of men, he turned and started to run. The wind was cold but he didn't feel it.

Tonight he was going back to the flop-house where they had kicked him put last night.

Tonight they couldn't kick him out. No one could throw him into the street again. If they tried, he'd buy the whole damned joint. The cops better leave Peter Squab alone. If they threw him in the coop, he'd go to the mayor and buy the damned police force.

As he ran, Peter Squab felt more and more of the power that money gave him.. He slowed up, drew up his chest and started to walk, slowly. He didn't have to run again ever.

He turned in at an all night restaurant and sat down at a table near the window. When the waitress brought the menu, she looked at him distastefully.

"No handouts," she said.

Peter Squab fished out a fifty dollar bill. He peeled it off his roll and pushed it at her.

"Start at the top," he pointed at the menu. "I'll tell you when to stop!"

He stared out the window. A bum stood with his nose pressed to the glass, looking eagerly at Peter. Peter turned away, an expression of distaste on his pinched face.

MARY HOWARD stood with her back to the door, watching Ross Chaney as he climbed out of the expensive car and came up the walk. Mary couldn't make out who he was in the dark. She had seen the car coming and adjusted her carefully-dyed blond hair. She stood quietly and the porch swing creaked because she had just left it. She surveyed the worn pair of slippers and the hole in the knee of her dress.

Probably a politician to see Pa, but if it wasn't, she'd have time to run and change. Ross passed under the light at the sidewalk and she saw his face. She turned and ran inside, screaming as she went:

"Ma—Fer God's sake, it's Ross Chaney. He just drove up. Stall him off while I get some clothes on."

Ma Howard reminded Ross Chaney, as they sat on the porch swing, that Mary was as pretty as ever and that she'd been awfully worried about him.

"You ain't been around for weeks." Ma had heard that Ross struck it rich and she saw that he was covered with clothing that shouted "class" half way down the block.

"I've been busy," Ross said. "Made a little dough since you saw me last. Is Mary stepping out any these nights?"

Ma shook her head.

"She's all broke up over you, Ross. Ain't been seeing a man in weeks." It was a lie and Ma knew it. She said what she knew Mary would say. The two were in perfect accord, so far as parting Ross Chaney from his money was concerned.

Ross was satisfied. They sat silently for a few minutes. Then, at a sound from the door, he looked up.

"Ross, honey."

He rose swiftly and Mary came into his arms. It seemed to him at that moment that Mary was as fresh and perfect as a rose. He didn't suspect that the suggestion of a rose garden came directly from Woolworth's.

"Ross, where have you been keeping yourself?"

He held her at arm's length.

"Some big business has been keeping me away," he said. "I almost forgot how swell you looked."

She hoped that he couldn't read her mind. She might not look so swell to him if any of the other boys showed up. Mary Howard didn't believe in letting the grass grow under her feet. After all, money was the most important thing, even if she didn't like the way Ross Chaney carried his head and put on airs about it.

"I been hoping you'd show up," she said, and for the first time, seemed to notice the powerful coupe at the curb. "Ross, that ain't your car."

"Sure," he said. "How about trying it out. I got ideas."

Mary looked at him coyly, then at her mother.

"You wouldn't care, Ma, not for a little while?"

Ma Howard tried to look worried.

"I guess not," she said finally. "Not with Ross."

SO the evening led toward the one haven Ross Chaney knew. It ended at the roulette table, and Mary Howard went home fifty: thousand dollars richer.

That night, Ross Chaney lost the last thing he had ever wanted. For, in spite of the warm kiss Mary Howard gave him on the porch, her real thoughts were not with him, but on the money and the way she would put Ma and herself in an apartment in Beverly Hills.

"You were real sweet," she said, looking up into Ross Chaney's eyes. "That was a funny man at the roulette table, Ross. He looked mad when I won all that money. Can anyone have a chance like that?"

"Only people I know," he said promptly. "It's my luck that pulled you through."

She squeezed his arm and hoped he'd go soon.

"I'd like to try it again some time," she said excitedly. "Thanks, Ross, for letting me keep all the money."

"Sure,"'he said. "Well—I guess I'd better go. Can I see you tomorrow night?"

She kissed him again, warmly this time. After all, a girl can afford a kiss or two for fifty thousand.

"Sure," she said airily. "Tomorrow night, and all the others."

She wondered if you could buy a house and move in the same day. If they couldn't, she and Ma could take a nice hotel room down-town. That would be fun. To hell with Ross Chaney. He couldn't find her, not once she got away.

"Good-night," he said, and went down the walk. She watched him climb into his car. He was whistling proudly.

"Sucker," she said in a low voice and whirled toward the door. "God but he's a nut. When I go back to that gamblin' house again, it won't be with him."

ROSS CHANEY hesitated, the fifty cent piece between his fingers. For the first time in a year, his fingers started to shake. He stared at the narrowing eyes of the dark faced croupier. He felt goose-flesh creeping up the back of his neck.

"Say that again," he invited. His voice wasn't steady.

"I said some of your friends were in today. They weren't so lucky as you have been."

The room was dead silent. No one had come in with Ross. They didn't dare come any more. Each feared that he wouldn't come back. They stared at him as they would a ghost, because he always had come back, to become more domineering and sure of himself after each victory.

"You can't scare me," he said. But he was scared. He wanted to ask who had come. Who had been unlucky.

"Your brother was here," the croupier said.

His brother—Johnny.

"He—didn't—lose?"

The croupier leered at him.

"The girl was here also. The one you called Mary. Peter Squab was here."

Chaney leaned forward over the wheel.

"You're a damned fool," he said. "You can't rattle me with that line. They wouldn't all come the same day. They couldn't all lose at once."

"Money is powerful," the croupier said. "People cannot leave it alone, even if they know it will burn their fingers."

Chaney grinned crookedly.

"It was their own fault," he said. "Mary was a bum, only just a different kind of a bum than Squab was."

"Johnny wasn't a bum," the croupier said. "He was a good kid. You brought them all here."

"Listen here," Chaney shouted, "you shut up. They didn't have to come back. They had enough."

The croupier 'smiled.

"You keep coming back," he said. "You'd come even if you knew you couldn't win. It was your fault that the others came."

Chaney was becoming quite calm now. He had convinced himself that he hated Mary. Hell, what difference did it make about Peter Squab? As for Johnny, well the kid had plenty of fun for a while.

"You can't beat me," he said. "Remember the number I won on the first time?"

The croupier nodded ever so slightly.

Chaney dropped the coin on Black 22.

"It's my lucky number," he said, and leaned back as the wheel spun around.

"You've been quite a profitable venture for us," the croupier said.

He dropped the ivory ball oh the wheel. Chaney didn't look up. He was on guard. His voice was harsh with fear as he asked:

"What do you mean?"

The croupier laughed. The ball was still spinning swiftly.

"I mean the way you acted as our agent."

Chaney's head jerked upward.

"I don't get it!"

The wheel stopped spinning. The ball was poised neatly on Black 21. Chaney sighed. He'd done it again.

"Not quite up to my first touch of luck," he said. "But—as long as it's black, I can't kick. Let's see, that makes it a million this time, doesn't it?"

The croupier folded his hands across his chest and didn't offer to pay off.

"I think it's about time we stopped kidding, don't you?" he said.

Chaney leaned forward, trying to look tough. He felt his knees growing weak. He didn't dare stand up.

"I—don't get it." he said again. This time, it was hardly more than a whisper.

Perspiration stood out on his face. His hands were cold and moist.

The croupier grinned evilly.

"I think you do," he said. "You've done more than your part to help us out. You've donated the souls of three people we could never have reached without your help. It's time to stop trying to evade us yourself."

Chaney didn't speak. His hands gripped the edge of the table.

"You didn't actually think we were childish enough to make that mistake the first night, did you?"

Ross Chaney remembered suddenly the night he had first beaten the wheel. The night he jarred the roulette table; sent the ball skidding away from Red 34 and saved his life.

He tried to speak: to defend himself, but when he opened his mouth, no sound, came out. The room was darker now, and the croupier's face seemed longer, and a sickly shade of yellow.

"You helped us a great deal, Chaney," the croupier said, "and all the time you tried to play us for suckers."

Chaney was thinking of Mary Howard, and Peter Squab, and of Johnny. He was thinking of how little good he'd done with that dough and how much harm.

"And all the time, you were the sucker, Ross Chaney," the croupier, said. "Look around, Chaney, and see what it got you."

The voice was harsh and filled with raw hatred. Chaney turned slowly toward the place where the door had been. His eyes wide open and his fists clenched. Ross Chaney's throat muscles moved convulsively and a horrified scream escaped his dry lips.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.