RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

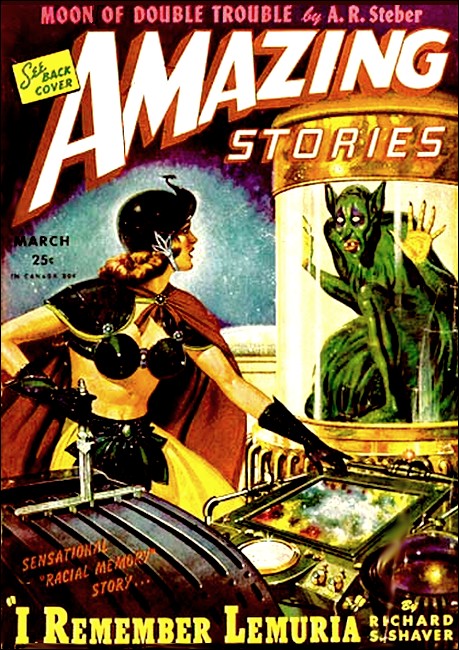

Amazing Stories, March 1945, with "Is This The Night?"

Beneath his feet a boars from the steps...

LIKE all prognosticators of the future, he claimed to have made

a mistake when the time came for the prediction to come true...

THE cab driver said, "I mighta known that address would be stuck on top of some hill. There ain't nothing but hills in this here part of town."

Ray Long stretched his legs and abandoned his gloomy contemplation of the streaming windows. Rain like this, he reflected, was unusual even in California. Almost continuous thunder made conversation an onerous task, while great jagged bolts of fire split apart the night, illuminating the countryside with spectacular brilliance.

Swearing under his breath, the driver put the car in low gear and the slow ascent of the steep incline began. The twin windshield wipers stopped their rhythmic swish-dak, swish-dak and a curtain of water obscured the glass, cutting off even a partial view of the street ahead.

After an indeterminable number of minutes had passed, the cab lurched to a sudden stop and the engine died. The driver flipped up the meter flag with unnecessary violence and said, "This is it, mister. That'll be a buck-twenty-five."

Long fumbled in his pocket while he peered through the fogged side-window. Beyond the sidewalk was a twenty-foot stretch of boggy lawn bordering a tiny wooden bungalow with a microscopic front porch. Pepper trees flanked the house, leaving it in shadows despite the almost constant flicker of lightning.

Long paid the meter charge, added a modest tip and said, "I'll be out in a few minutes. If you're still around, I'll ride back with you. But I'm not paying a waiting charge."

He eyed the driving rain with open distaste, pulled the collar of his trench-coat about his neck and the brim of his felt hat over his eyes, then flipped open the cab door and raced with long-legged strides along the walk leading to the porch.

There, he stopped to shake water from his hat and the folds of his coat, then set his hand to the bronze-painted knocker.

A light went on in the reception hall, its rays visible through narrow panes of glass on either side of the door. A chain rattled and the door swung open a crack, disclosing a woman's face and a narrow strip of a flowered housedress.

"Hello," Long said dourly. "I'd like to see Jonah Brown."

"Who are you?" the face asked. It was a young face, pretty, and framed in blonde hair that fell to the shoulders.

"Ray Long, of the Chronicle, miss."

"What do you want to see my grandfather about?" the girl persisted.

A LONG, earth-shaking roll of thunder forced Long to wait until his answer would be audible. He said savagely, "Maybe you haven't noticed but it's wet out here. And it costs a quarter to have a suit pressed. So if we must play question and answer games, let's do it inside, hunh?"

The girl continued to look doubtful, but she released the door-chain and widened the opening enough for Long to enter a small, modestly-furnished living-room. He removed his hat and trench-coat, placed them on a rack near the door and turned back to the girl.

She was smiling in a friendly way, but there was a haunted expression in her eyes that puzzled him. She could not have been more than twenty.

Long said gravely, "I didn't mean to be rude. But our managing editor likes to send the cheap help out on assignments in this kind of weather. He wants me to get an interview from your grandfather."

She nodded. "Won't you sit down, Mr. Long? Ill ask Grandfather if he'll see you."

She turned and left the room, going along a hall that led to the rear of the bungalow. Long watched the swing of her rounded hips under the thin house-dress with casual appreciation. He ignored the chair the girl had indicated, fished a cigarette from a crumpled pack in the breast pocket of his suit coat and got it burning.

The girl came back almost immediately. "Grandfather will see you, Mr. Long. Please come this way."

He followed her along the hall and into a small bedroom off the rear of the house. It contained a wide bed, a small table with several bottles and a glass on its top, and a straightbacked chair.

There was a man in the bed—a huge-bodied man, with a thin angular face topped by a mane of thick white hair.

Large, deep-set eyes regarded the reporter from either side of a jutting, beaked nose. He lay propped up on pillows, a heavy book in one hand with a finger inserted to mark his place.

The girl said, "This is Mr. Long, Grandfather," gave the visitor a bright, mechanical smile and went out, closing the door softly behind her.

The man in the bed said, "Please sit down, Mr. Long." His voice was deep and resonant. He continued to regard the young man from the depths of those sunken eyes.

Long lowered himself onto the straight-backed chair, pinched out his cigarette and dropped the butt into a pocket.

He said: "Mr. Brown, I represent the Chronicle. Our managing editor ran across a prophecy of yours in the old files of the paper—a prophecy you made twenty-five years ago. Perhaps yon recall what it was."

"I do," Jonah Brown said calmly. "I predicted that the world would come to an end on January 10, 1920."

"Exactly." Long leaned back in the chair and crossed his legs. "We'd like to run an article, mentioning that prediction and explaining how the error occurred in your calculations."

The ghost of a smile touched the old man's thin lips. He said, "The reason is not obscure. I—"

LIGHTNING flashed suddenly, close to the window, and a blast of thunder shook the walls. Rain rattled against the room's single window, like the fingers of a skeleton seeking admittance.

The man in the bed waited until the sound of the storm had faded sufficiently for his voice to be heard, then continued:

"I failed to read, correctly, the message given to me by Almighty God. Long ago the truth was revealed to me, young man. But in my haste to acquaint the peoples of the earth with their impending doom, I miscalculated the date when calamity would fall upon them. It was a trivial error, 'tis true... a matter of twenty-five years."

Ray Long blinked. "In other words, the world will be destroyed this year? In 1945?"

"That is correct," replied Jonah Brown steadily. "To be exact, on January 10, 1945."

An icy finger seemed to touch Long's spine. In spite of his carefully masked contempt for long-haired viewers-with-alarm such as the old man in the bed, he found himself shaken by the uttter certainty in that deep voice.

"But this is January 10th, Mr. Brown. Are you seriously suggesting that this is the night it will happen?"

"I am not suggesting, my young friend: I am informing you of an unalterable fact."

"Of course," Long said hastily. There was no point in antagonizing the old goat. He glanced at his wristwatch. "It is now 9:25. It seems the old globe has less than three hours left to go. Lots of folks aren't going to like that."

He stood up. "Thanks for letting the Chronicle in on the facts, Mr. Brown. I'll send you over a copy of tomorrow's paper in the morning, with my article of our little talk somewhere on one of the back pages. You see, the impending end of the world doesn't rate a better location with our managing editor."

The man in the bed nodded imperturbably but did not speak. Long let himself out of the room, closed the door softly and moved along the hall toward the living room.

The blonde-haired young woman was nowhere in sight. Long shrugged into his trench-coat and pulled his hat down over his eyes. The storm seemingly had passed; he no longer heard the surge of thunder and the brittle crackle of lightning outside the bungalow walls. He caught himself wondering if, twenty-five years from tonight, some other Chronicle reporter would be coming out to learn why old Jonah Brown's second prediction hadn't proved any better than the first.

He opened the door, took a single step... and froze there, both feet on the threshold.

He was staring at... nothing. The street was gone, the hill was gone, the myriad lights marking the city were gone.

There was only black eternal infinity.

His stricken mind refused to accept what the eyes testified. Instinctively he turned to flee back into the home of Jonah Brown. It too had disappeared.

He sought frantically to maintain his balance on the threshold—now a single plank. Slowly it tilted and sent him spinning into space. His scream———

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.