RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Fantastic Adventures, December 1943, with "Professor Cyclone"

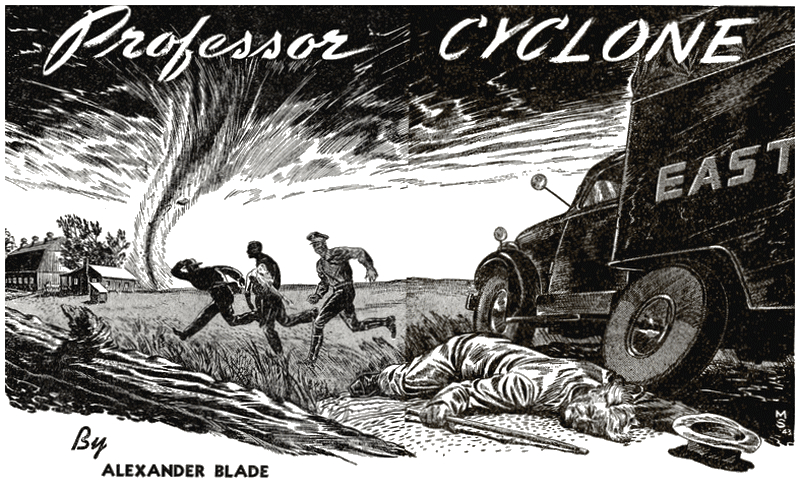

Sands scooped the girl into his arms and, with Beasley

and Clark, raced madly across the field toward the house.

To all outward appearances, Professor Waldon was a harmless little man. Then the farmers in the district discovered he knew how to harness the forces of Nature.

A MAN came out of the kitchen and stood behind his wife on the screened back porch of the farmhouse. He was dressed in overalls and his face was burned red from the sun. His face and hands were dripping wet, and he held a towel.

"You say your name's Waldon, mister?" he asked the middle-aged man who had come up to the house from the road.

Professor Waldon nodded. He was a frail, mousy little man, with mild eyes that never wavered from the man behind the screen. His thin, parchment-like face, wisps of gray hair that fluttered against an almost bare scalp, were indicative of long sunless hours spent indoors.

The woman hadn't moved. She looked frightened, waiting for her husband to handle the situation The farmer's facial muscles worked strangely. The towel fell from his arm and fluttered to the floor. He didn't reach to pick it up. Instead, his fingers balled into heavy fists.

"You the same man's been calling on my neighbors the last few days?"

The professor nodded once more, making no attempt to speak.

"You been asking for money," the man on the porch said in a cold voice. "Lots of money. You been promising protection." His shoulders squared. "From what, mister?"

Professor Waldon's lips tightened. He was wasting time. He'd been wasting time for a week. He'd have to show these country bumpkins that he meant business.

"Am I to understand that you refuse to become a member of my little group?" The question was softly, almost gently, put.

Jack Freed, the man on the porch, stiffened.

"You're damned right I refuse!" He stepped closer to the door. "You get the hell off my place and stay off, understand? You ain't pulling none of this Al Capone stuff on us. If I catch you within half a mile of here again, I'll wring your skinny little neck. I'll run a pitchfork through your gut. That's the answer we got for you city gangsters."

Professor Waldon smiled. It wasn't a pleasant smile. It showed the yellow teeth that were usually well covered. It made his blue eyes squint until they were like pin points of hard steel. He backed away into the darkness.

"You understand the penalty for your refusal?"

Freed took a step forward.

"I understand you're either ready for the county asylum or already escaped from it," he said. "You damned pipsqueak, get out of here."

Professor Waldon turned and walked quickly toward his Ford car. He had tried to collect from seven farmers along this road. Thus far his luck had been poor.

Not that he felt badly about it. His was a strictly untried venture, but he was confident of himself. He stared back at the farm. It was typical of the section. A box of a house flanked by a huge red barn and weather-beaten out-buildings.

Professor Waldon had driven sedately into seven farm yards, and left each of them unsuccessfully.

None of them was to be spared.

His second visit would be greeted with much more respect than the first.

THE cyclone struck Freed's place first. No one saw it coming

because twisters are like that. It ripped down on a little three

mile section of the Plain Road, lifted Freed's house into the air

and tipped it over into the farm yard. It came late on a clear,

warm night.

The barn roof was never found—not a timber or a shingle. The chickens were blown through a fence and killed, a hundred of them. Horses, cows, farm equipment—all destroyed.

The Red Cross was on the scene by eight the following morning. Freed stood in what was once his own back yard, rubbing a calloused hand over his eyes, a grimy bit of cardboard gripped tightly in his left hand.

His wife Sarah stood near him, watching the Red Cross truck come up the drive.

Sheriff Beasely of Bath was with the driver. Beasely walked toward Freed. He was a stocky, keen-eyed man of about fifty. He talked in a stern voice that had developed from running the sheriff's office of Bath for the past twenty years. He gripped Freed's hand tightly.

"Bad luck, Jack," he said. "We've got tents in the truck. We'll leave two for you and be around later with food. Have to get over to Narish's place. The damned thing took every last building he had."

Freed couldn't talk. There was a gleam in his eyes that was more than fear. It was a deep-seated, terrible anger.

He pushed the cardboard ticket toward Beasely.

Nick Beasely's jaw dropped.

"You—got one, too?"

Freed nodded and Sarah started to cry softly.

"That little man was here just last night," she said in a low voice. "Jack threw him off the place."

The truck backed into a level spot, and the driver started throwing canvas out the rear door. Nick Beasely took the ticket, reached into his pocket and removed a half dozen pieces of cardboard identical to it. He stared at them. Each read:

COMPLIMENTS OF PROFESSOR CYCLONE

"My God," he said in a strained voice. "It can't be possible. The guy's the Devil himself."

Freed nodded.

"But I still can't understand," he said. "I heard he threatened the other farmers. They all kicked him out. None of us thought..."

Beasely shook his head.

"I don't get it; not at all," he admitted, and pushed the collection of cards in his pocket. "A dried-up little man threatens a lot of farmers. They get mad and want to tar and feather him. The next night a cyclone drops down and tears hell outa all of them."

His eyes raised to stare steadily into Freed's.

"I don't know how it could be. Where did you find the ticket?" Freed shivered.

"It was in Sarah's pocketbook this morning. We left it on the piano last night."

Beasely nodded again.

"Narish found one stuck in his pocket. The rest found them the same way. How in hell...?"

His voice trailed off as he turned toward the truck.

"Better get these tents ready," he said. "Looks like rain. There's a lot of kids over at Narish's. We'll have to get them under cover."

THAT'S the way it ended. At least, the first incident. By

night the Plain Road looked as though an invading army had spread

across it. Tents were up. Woodlots of elm trees, twisted and

broken in half, gave a ghostly, out-of-this-world appearance to

the fields. Barns, torn into small planks and spread over fields.

Houses completely destroyed. Two school houses leveled to the

ground. Tin roofs wrapped around trees like horse shoes. Men

sobbing, their possessions gone, spirits broken. Desolation for

seven farms.

Midnight—the Red Cross in control. A lonely Ford shook and clattered down the narrow road. Professor Waldon, a smile on his lips, surveyed the havoc.

He passed the tents where Jack and Sarah Freed were sitting beside a single lantern, trying to plan another life.

Professor Waldon grinned delightedly.

This had been a fine test. He was sure that on his next visit to Jack and Sarah Freed they would be more interested in what he had to offer.

FRANCES WALDON opened the door of the green cottage and smiled at the man who had just knocked.

"Oh! Fred, you're here already?"

She held the door wider, a pleased expression on her youthful face. Fred Sands walked into the living-room. He stopped short, staring around.

"Good Lord, haven't you settled yet?"

Frances, in a neat blue apron, dust-cap over her head, smiled defensively.

"We've been in Lansing a week," she admitted. "But Dad's been away most of the time. I've done all the work by myself. It's pretty hard."

Sands settled into a sheet-covered chair, and propped himself up lazily. He was perhaps twenty-six, lean and outdoorish. Sands was taking officers' training at Michigan State.

"Look," he said eagerly. "When I heard you and your Dad had come up from Ann Arbor for the summer, I hurried right over. How about letting me help out. We can put things in order in a hurry."

Frances Waldon stood before him, broom in hand, brown eyes sparkling in admiration. She had known Fred for six months. Now that he had answered her note so quickly, she knew that she held more than a passing interest for him.

"By all means!" She thrust the broom into his hands. "I've cleaned the dining-room. Sweep it out and place the furniture. The kitchen is complete except for barrels of dishes you can unpack."

"Golly," Sands said. "After the way they've been pushing me around, it'll sure be nice seeing you once in a while. You said Pop Waldon is traveling. I thought this was to be a vacation?"

Frances looked worried.

"I don't quite understand Dad," she confessed. "You see, he overworked at Ann Arbor. Last week he just packed up his most precious books and suggested a vacation. We rented this place and it seems that this will be our home for the next three months. Dad's out every day, driving around the country. He's interested in wind storms and their causes. Claims this is the ideal spot to study them. Some insurance company is paying him for his research work."

By this time they were both busy in the small dining-room. One corner of it held a large, glassed cupboard, two barrels of dishes and a table that had been taken apart in sections. With the floor swept, small talk passing the time for them both, Sands was at last busy with the table. Gradually the room took shape and he found himself unpacking the dishes.

"Expect to be here all summer myself," Sands confessed at last. "I'll go into officers' training in the - fall and should see action yet if they don't kill the Japs off before I get at them."

Frances felt a little shudder pass through her.

"You—you'll be at officers' training for some time?"

Fred Sands looked up, tenderness in his eyes.

"Don't worry, sport, I'm not leaving you until I have to. I haven't been able to find a 'best girl', but things are picking up."

Frances Waldon was very busy just then, her head bent low over a barrel.

"Smart, aren't you?" There was a pleased ring in her voice.

Fred smiled.

"Not so smart," he admitted. "Just darned set in my ways."

HE was busy after that carefully unwrapping the dishes that

were to be placed on the cupboard shelves. Half way down in the

barrel, he hesitated suddenly as a creased card fluttered from a

cup and landed face up. He reached in carefully and picked it up,

shielding it with the rim of the barrel.

He read the message quickly, and a frown creased his forehead.

COMPLIMENTS OF PROFESSOR CYCLONE

"Frances," he said in a sharp voice, then regretted that he had spoken.

The girl looked up.

"Break a dish?" she asked.

Fred Sands hesitated, then pushed the card out of sight under the packing.

"Caught a lovely splinter with my thumb," he said. "It startled me for a minute."

Frances Waldon straightened, hearing the chug-chug of a car as it entered the drive.

"Dad's home," she said, and brushed hair back from her face. "He'll be glad to see you, Fred."

Fred Sands straightened, slipping the folded card into his pocket as he did so.

"Good," he said aloud; then, to himself, "But I have my doubts."

The screen opened and Professor Waldon came in, his soft shoes making little pat-pat sounds on the carpet as he crossed the living-room. Nothing marred the pleasure of his gentle smile as he saw Fred Sands standing near his daughter.

"Hello, Fred." He walked toward the couple. "This is a real pleasure. I see you answered Frances' call for help promptly. She needs it. I'm spending more time away from home than I have any right to."

Sands accepted the old man's hand, feeling a bit foolish about his thoughts of a few moments ago.

"Glad that we meet again, Prof," he said. "Still fooling around with air currents, I hear."

Professor Waldon dismissed the subject with a gesture of disinterest.

"Very dry subject, my boy. I'm a crack-pot on it, and in addition to that the Upper States Insurance Company pays me a healthy sum to do a little predicting for them now and then. Can't pass up good money during summer vacation."

They all laughed and Frances suggested dinner.

IT was several hours later when Fred Sands took his leave. In

those hours, however, he noticed that Professor Waldon seemed

aged and a trifle more sure of himself than he had in the old

days. Some of the indecision and the absent-mindedness were gone.

Waldon seemed happy and preoccupied.

Also, Fred Sands thought as he climbed aboard the East Lansing bus, Waldon had a lot more money than usual. He had seen the roll when Waldon paid a delivery boy who came to the back door. The professor's pocket book was bulging with bills— big bills.

Professor Waldon had done even better than Sands could guess. Farmers, unable to accuse an old man of stirring up the winds, were still frightened and superstitious enough not to take the chance Jake Freed had taken. Three thousand dollars was now the set price for protection, and Waldon had visited a dozen farms since morning.

A dozen farms that were protected, at least for the present, from receiving a card like the one pressed deep into Fred Sands' pocket. A card that meant their entire life work wiped away over night:

COMPLIMENTS OF PROFESSOR CYCLONE

FRED SANDS turned on his side, leaned back on his pillow and

tried to look unconcerned about the question he was going to ask.

"Harry..."

Harry Freed, his roommate, looked up from the reading-table and placed his book to one side.

"Thought you'd gone to sleep," he said absently. "Say, this book Eleven Came Back is some..."

Sands grinned.

"I know," he interrupted. "Look, Harry, tell me about that cyclone again, will you?"

Harry Freed's eyes narrowed.

"I'd rather not," he said. Freed was heavy-set and given to slow, careful speech. His body seemed to tense as he continued. "Dad lost... Well, you know, Fred. We were roommates all through school at Ann Arbor. I've had Dad's money behind me. Now I'm in officers' training. I can't get out if I want to, and I ought to be at home— what's left of it—helping Dad clean things up. To talk or even think about it hurts like hell."

Sands nodded sympathetically.

"I'm not being nosey," he explained. "I think I might be able to help..."

"No." Harry Freed stood up. He walked to the door, then turned and faced the man on the bed. "No good. I know you've got money. I told you about that before."

"It's not that," Fred protested. "I can't tell you what is on my mind now, not until I'm sure. I might know something..."

"If it's about that old man who visited Dad, that's out," Freed said. "I never could understand how he could be connected with it. Storms don't work for anyone. He must have been an old screwball. Nick Beasely, the sheriff at Bath, questioned him. He just chuckled in Beasely's face. Says he's a representative of some insurance company."

"Upper States Insurance?" Fred Sands shot the question at him.

Fred's eyes widened.

"Why, yes. How did you know?"

Sands shook his head.

"That's just what I can't tell until I know what I'm talking about. Someone is involved in the thing that I could hurt very deeply. I'm not so sure that the cyclone was natural. You see, I studied wind currents when I was in school. All I'm asking now is did you actually see one of those cards that was left after the cyclone?"

"Sands, if you know anything..."

Fred Sands frowned.

"You're a pal of mine," he said. "I won't talk now, but believe me, Harry, if I find out I can help in any way to protect others from what happened to your family, I won't let anything stand in my way. It might be pretty hard, so I'm going slow. Now, you saw one of those cards?"

Freed nodded.

"Nick Beasely showed it to me. He's trying to trace the print shop that put them out."

SANDS drew the crumpled card from his pocket and passed it

over without a word. Harry Freed took it, turned the printed side

up and stared with incredulous eyes.

"I'll be damned. Where did you get this, Fred?"

"It's the same as the one the sheriff showed you?"

Freed's face turned an angry red.

"The same! Where did you get it?"

"From the last place in the world I'd ever suspect." Sands took the card back again. "Does Beasely, that sheriff at Bath, have a description of this Professor Cyclone?"

"He ought to," Freed said grimly. "Several farmers lost everything they had after he had visited them. They didn't forget. Besides that, he's collected a lot of money up there since then. No one will admit it to Beasely and he's at a standstill. You can't arrest a man for threatening to stir up a cyclone. It would sound pretty silly in court."

Sands got up and started to dress.

"Not so silly but what others are paying protection to avoid the same thing. Is that right?"

"That's right," Freed said. "Are you going out again tonight?"

Sands was buttoning his shirt.

"Tell anyone who calls, I'll be back Monday morning," he said. "It's ten o'clock Friday night now. I'm heading for Bath—and Nick Beasely."

Freed's eyes lighted up.

"Suppose I could go along?"

"Stick to your books, laddie." Sands put a friendly hand on the younger man's shoulder. "Your temper is pitched pretty high. I'm expecting to talk with Professor Cyclone this weekend, and it's going to demand some pretty delicate handling. If I need you, I'll phone."

They shook hands.

"Look up my Dad," Freed begged. "He's feeling pretty low."

Sands opened the door, then hesitated.

"Call Frances Waldon for me and tell her I'll see her Monday night, will you?" He passed a slip of paper to Freed. "Here's the number."

"Sure, glad to. Got a case on the girl?"

"And how," Sands said, and closed the door.

Freed stared at the paper in his hand.

"Waldon?" he said in a low voice. "Afraid to hurt someone's feelings?" He folded the paper carefully and put it into his pocket. He went to the window and stared after Sands as he crossed the campus and disappeared into the darkness.

"Waldon? I wonder?"

As though he had made a decision, Freed went to the closet and dragged out a raincoat. He slipped into it, left the room, closed and locked the door and walked rapidly down the hall.

SHERIFF NICK BEASELY was badly puzzled. Bath wasn't a big

town, and it had suffered from cyclones many times before. Nick

hadn't had a detective case on his hands since that murder at the

school house several years back. Now he wasn't quite sure whether

this was a case for the law or a case for God Almighty. Cyclones

just didn't demand human attention, or brook human interference.

When they came, they came without preview. They certainly didn't

fit into the picture of an old man demanding money to keep them

away.

Nick was no fool. In fifty years he had learned a lot about science and freaks. Maybe this Professor Cyclone could see such things in the stars. Maybe he knew what was going to happen and just tried to scare them into paying for something that was bound to happen anyhow.

Nick rubbed his chin reflectively and took the cards from his pocket once more.

COMPLIMENTS OF PROFESSOR CYCLONE

Damned if it didn't give a man the shudders.

A knock sounded on Nick's office door. He swung his feet down off the desk hurriedly and swivelled until he had a good view of anyone who might come in.

"Open up," he said. "Don't have to knock."

The door opened and a young fellow came in. He had an honest grin, sandy brown hair that refused to stay combed, and blue eyes that sparkled as they saw the stout figure of Nick Beasely at the desk.

"Mr. Beasely?" Fred Sands said, "I heard you take your feet off the desk. Put 'em back, sir, where you'll be comfortable."

Nick's eyes widened slightly.

"Looks like we got a detective in our midst." He stood up and offered a hairy hand. "What can I do for you?"

Sands took the proferred hand.

"My name's Sands—Fred Sands," he said. "Taking officers' training down at East Lansing. I came up to see you about Doctor Cyclone."

Beasely's eyebrows arched and his hand went a little limp in Fred's grasp.

"Everyone wants to see me about that guy," he said sadly. "Sit down. I don't know much but I'll tell it to anyone who's got any business knowing it."

He sat down, swung his feet back to the desk and said:

"Ain't much in the way of chairs. Don't sit around long enough. Pull up that frayed object at my right."

Sands drew the old chair over near the desk, sat down and leaned forward.

"I guess I'm entitled to know what happened," he said doubtfully. "I came up here at Harry Freed's suggestion."

Beasely relaxed. He knew Harry. Jack Freed's boy. Freed had lost as much as the rest of them.

"That puts you in the front line," he said. "What is it you want to know?"

Fred Sands had thought things out pretty carefully since he left Lansing.

"Can you pin anything on this man who calls himself Waldon," he asked. "Has he actually broken any laws?"

Beasely's fist crashed down on the desk.

"Godammit, no!" he shouted. "That's what burns me up. I can lock him up for threatening Freed and the others. A jury will laugh their heads off when I try to accuse him of starting a cyclone. I've heard by back fences that he's back demanding, and getting, a mint of money from other farmers who are scared to death. I know who they are and I'm trying to get them to talk, to go to court and accuse him of blackmail or something. They are scared to death. None of 'em will admit that they've donated a cent to this old cootie. I tell you, Sands, I'm about nuts."

He sank back, eyes closed tightly, fists clenched.

"Then, if Cyclone doesn't get caught in the act of getting the gods to start a storm, or accepting money from your friends, there's nothing you can do?"

"Nothing. I imagine he's giving a receipt of some kind for the money he gets. Claims he's an agent for the Upper States Insurance Company. I've checked that. It's a legitimate outfit. They have main offices in Detroit and temporary offices in the Olds Hotel in Lansing. Nothing black there and they have a Professor Herbert Waldon working for them as a sort of research man."

"You've checked to find out if he's the same man?"

"Look, youngster," Beasely said suddenly. "I don't know why I'm telling you this, except that you're a pal of Harry Freed's. Yes, we've found out that Herbert Waldon fits the description given. We don't know if he's Professor Cyclone, because we've never seen him leave one of them damn cards. But he's air-tight. Protected from every angle. We know where he lives —we know that he has a daughter named Frances—and I know why you're up here this week-end."

He sat back, a triumphant look in his eyes.

Fred Sands scowled.

"You've a pretty efficient outfit, haven't you?" he said coldly.

Beasely grinned.

"Now don't get mad," he said. "And don't be sore at Harry. The kid got to worrying about you and what you were up to. He knew Waldon's name and you mentioned it when you left. Harry called an hour ago and asked me to tell you to lay off. You'll just get in trouble and break some nice girl's heart. I think you know what I mean. I've been handling the law around here for years. I think you're on the level. Can't explain why, but I guess you look square. Now, why don't you go back to school and forget all about it?"

SANDS was silent for a full minute.

He knew that his knowledge might wash up everything that was between Frances Waldon and himself. He didn't blame Harry. In fact, the more he saw of Harry Freed and Nick Beasely, the more he wanted to help. It wasn't a pleasant decision to make, but he made it.

"Look, Nick." He didn't even realize he had used the Sheriff's first name. "You're on the level with me. I'm the same way with you. I'm in love with Fran Waldon. I think she likes me pretty well. But when one man starts out to make a fortune by wrecking the lives of God knows how many innocent people, I can't stand by and watch him do it. You've been trying to establish one fact: Is Waldon the same man who's leaving those 'Compliment' cards?"

Beasely was staring straight into Sand's eyes.

"You don't have to..."

"I want you to have this," Sands continued, ignoring Beasely's words. He drew the crumpled card from his pocket and flipped it on the desk. "This is one of those Cyclone cards. I found it when Miss Waldon and I were unpacking dishes at Waldon's home. It must have fallen from his pocket."

Beasely picked up the card and stared at it with gradually narrowing eyes. A low whistle escaped his lips.

"I think I owe you a vote of thanks for this," he said. "It puts a steadier light on everything. Maybe we better get the State Police in about now. Things are getting a little out of my reach."

He picked up the phone and leaning over, started cranking on the phone box at the side of the desk.

"Hello, Myrtle. Put a call through to East Lansing. Yes, the State Police. I want to talk with Captain Clark—Deems Clark."

HARRY FREED parked in a drive half a block down LaPeer Street

from the green cottage where the Waldon's had moved in. It was

well past two in the morning. After calling Sheriff Beasely, he

had decided to waste no time. He didn't know that Waldon had

already been traced and given up as a bad job. Harry Freed knew

only that his mother and father were living in an old tent where

their home had once stood. Harry wasn't cautious. He was beyond

that. He was mad all the way through. Anger pumped hot blood

through his wrists until the fists that clenched the wheel were

tight with agony.

His eyes, staring through the darkness, were on the front door of the cottage.

Several hours ago he had watched a girl he thought to be Frances Waldon come out and hail a cab to town. Thus far she hadn't returned.

A single light burned at the rear of the cottage. He had to fight himself to keep from entering the little house and throttling the professor with his bare hands.

That wouldn't do. There was a better way.

A big freight truck entered the far end of the block, slipped into low gear and rolled to a stop almost across from him.

Eastern Trucking was lettered in red along the side of the trailer. He noticed it because sight of the truck touched a vaguely familiar spot in his mind. The motor purred slowly.

He looked back toward the cottage. The front door opened and a slightly built old man came out. He was carrying a heavy cane. Harry Freed knew Professor Waldon. He had seen him many times in Ann Arbor.

The professor looked both ways along the street. Although it was dark, Harry slumped over the wheel until he was sure no one could see him.

A strange thing happened.

The lights on the truck opposite him went out. The cab door opened. The professor, apparently satisfied, walked briskly to the truck and climbed in. The lights went on again and the truck roared into low gear and started to move away.

Freed controlled himself with difficulty. Thus far, the truck had not awakened anything but curiosity within him. Perhaps a friend of the professor had offered to give him a lift. That was often done in spite of regulations to the contrary.

He waited until the truck turned the corner on South Logan. Then he backed out and followed at a safe distance.

Logan was well lighted but the traffic was heavy.

Waldon had seen him but a few times. There was no danger as long as he stayed in traffic.

HE could see the truck well enough. He followed it past the

Olds plant, up the incline and over Grand River Bridge. The

traffic lessened and Freed fell behind a safe distance. The truck

didn't hesitate at Mount Hope Avenue, but rolled straight through

on the Eaton Rapids road.

Harry knew the way well. Eaton Rapids was the next town, a small woolen-mill village sixteen miles away.

Then a thought struck Freed.

Between him and Eaton Rapids was a rich, rolling farm country. A section thus far untouched by Professor Cyclone. A group of farm homes where money wouldn't be too hard to collect.

He clenched his teeth and kept driving. Once the truck veered out and stopped. Harry drove straight past, went around the big curve beyond the school house and drove off on a small country road. He stopped the car, doused the lights and waited.

The truck roared past on the concrete and he backed out and followed again. This time he kept his lights out. A mile behind the truck, he could follow its tail light easily enough.

Harry Freed came very close to solving the mystery of Professor Cyclone that night. So close that he was halfway across the sixteen mile stretch before he saw the bridge ahead, and the lantern that lighted a big sign:

Bridge Out—End of Road.

His brakes screamed an answer as he pressed the foot pedal to the floor. The bridge, he remembered, was a big job of concrete. Even as he halted, he knew instinctively that there had been no flood this spring that would move it.

After that, nothing was very clear. The car halted, its front bumpers almost touching the barricade. He could see the dim outline of the truck, its lights out, parked on the bridge. Then a flashlight was in his face.

He heard a voice, the calm voice of an old man, low, yet filled with hatred.

"You can't poke your youthful nose into the affairs of Professor Cyclone. We gave you a chance to escape, but you persisted."

He could see the snout of a long, black cane pressed into his face, then realized with horror that it wasn't a cane at all, but the open muzzle of a gun.

He felt the withering, searing flame as it struck his face and the intense, terrible agony of burning flesh. Harry Freed threw up a protecting hand, trying to force the weapon away from him. Flames enveloped his body and he could see no more.

Then in his mind, a gradual release from horror. A release that was cool and dark and everlasting....

THE man on the wrecker watched the chain grow taut. He turned

to Captain Deems Clark of the Michigan State Police. There was a

tense expression on his face. The job of dragging submerged cars

out of the water wasn't always pleasant.

"She's tight," he shouted. "Okay to start hauling?"

Clark, Sheriff Nick Beasely of Bath, and Fred Sands stood together on the Grand River Bridge. Several cars had halted and their occupants were talking excitedly in a group. A police car, the one that had brought Clark and his friends, was parked in the grove close to the river. The wrecker had its back wheels firmly anchored in the high bank by four-by-fours.

Captain Clark nodded, his thin, browned face showing no visible emotion.

"Take it easy," he said. "We don't want to do this job twice."

The policeman in the wrecker shook his head.

"She's hooked tight," he said, and started the motor. The wrecker slipped into low gear, started forward in jerky movements and rolled up the bank.

Fred Sands wanted to look away. He wasn't soft, but the thought that young Freed might be in the submerged car staggered him. He watched the chain come from the water, weeds dripping from the links. Then the radiator cap and gradually the entire length of the car emerged from the river and rolled on flat tires up the bank.

The crowd of spectators started running toward the scene but the captain warned them away.

He went down the steep bank and waited until the death car was safe on high ground.

"Sands," he said. "You said Harry Freed's car was missing. That you couldn't locate him when you got back. Is this the car?"

Sands followed Beasely down the bank, walking slowly. He nodded his head. Something choked up inside him and he couldn't speak. A blackened, unrecognizable thing hung over the steering wheel of the wrecked car.

The three of them reached the side of the car. The trooper in the wrecker got out. He and his companion hurried the spectators back to the road. Clark opened the door. It was badly jammed and he had to use force. The burned bundle rolled out and hit the ground with a thud. Somewhere behind him Sands heard a woman scream in terror. A low hum of voices started. Clark swore aloud, and slipping out of his coat, he placed it quickly over the body.

Not before Sands saw the fraternity pin, its single diamond still glistening on the remains of the burned coat.

"It's Harry," he said, and turned away abruptly. None of them spoke until they reached the road once more. Clark rounded up his men.

"Get an ambulance out here and take care of the body. Have the car taken into Lansing. We'll go over it for clues. Damned if I know..."

His voice trailed off helplessly. He walked quickly to the patrol car and waited until Sands and Nick Beasely joined him.

"BUT burned," Sands said helplessly.

"The car was in good condition. Yet Harry was burned to a crisp." He shuddered, remembering the last time they had talked together on Friday night. "I'll get the devil who did this if..."

"You won't have to," Nick Beasely said abruptly. "Clark and I are in on this, too. I don't know what happened back there, but someone will pay for it."

Clark started talking. He had the car up to eighty now, and they were hurtling back toward Lansing. He seemed to be reviewing things in his own mind.

"Patrol car reported tracks in the mud this morning just after daylight," he said. "You and Beasely came in and when you mentioned you'd been looking for Freed, I got the idea. Freed must have been pretty close to something. Something that, made him a safer bet dead than alive."

"But how in hell did he get burned like that?" Beasely asked. "He didn't just drive into that river by himself."

Clark shook his head.

"Might have been an accident," he suggested. "After all, people do light cigarettes in their cars."

Sands shook his head.

"That's out," he said. "Harry Freed never smoked a cigarette in his life. He was checking up on Professor Waldon and he found out too much. It's up to us to find out the same thing, and keep from getting ourselves murdered."

"Professor Waldon," Beasely said in a choked voice. "We've got evidence that condemns him in our own minds, but how in hell does he do it? We've got to find that out. Professor Cyclone is a damned slick bundle."

Clark was silent for a while. He took the turn on Mount Hope Avenue and roared across the short cut toward East Lansing.

"We'll find out," he said grimly. "And God pity Professor Cyclone when we do."

"NO." Frances Waldon stepped away from the door and allowed

Sands to enter the cottage. "Dad left last night after I went to

town. You and I had a date, remember?"

Sands said he did, apologized for not keeping it, and Frances continued.

"I went out about nine. Dad said not to wait up for him. Said he had a trip to make to Ann Arbor and promised to be home today."

Sands was at a loss for words. He could hardly tell Frances what had happened to Harry Freed. What they suspected. He remained standing just inside the door.

"I—I wanted to see him," he said lamely. "I wish I could stay, but they're expecting me at school. Your Dad won't be back until late?"

Frances grasped both his hands in hers. She stared at him, a worried look springing into her eyes.

"Fred—what did I do—what did Dad do to make you stay away? You realize you're acting very strangely?"

Sands choked. He wanted to shout the whole story at her. To tell her that Waldon, her father, was Professor Cyclone. That he had destroyed homes —had killed Harry Freed. He tried to keep his voice low.

"I'll tell you a little later," he said. "Something's come up that makes it important to see your Dad, that's all."

"Something about school?"

Sands nodded, hoping he wouldn't have to go into detail. Frances seemed vastly relieved.

"I'm sorry," she said, "but, at least it isn't as serious as your expression indicated. You will come in for an evening soon?"

Sands promised and left hurriedly. Once outside, he traversed the length of the street, turned on to Logan and hailed a cruising police car. Clark and Beasely were waiting for him.

"I—I feel like seven kinds of a heel, spying on that poor kid," he said, when he was in the car. "She knows nothing of what's going on. Says her father left for Arm Arbor last night. Doesn't expect him back until later today."

Beasely sighed.

"It's like tracing a turtle in a swamp," he said disgustedly. "The farmers who have paid him money won't talk. We don't know what he's up to, so how can we catch him?"

Captain Clark was threading the car swiftly through traffic.

"I'm not so sure of that," he said. "A few minutes ago the East Lansing office turned in a report that a heavy storm had hit along Grand River just outside Eaton Rapids. Half a dozen houses were blown down. Three people killed outright."

The car was moving swiftly toward the outskirts of town. They hit the pavement behind a tractor, roared around it on two wheels and Clark pushed the gas pedal to the floor. The three of them were silent until the car straightened itself out.

Sands released his grip on the door handle.

"You think Professor Cyclone may have something to do with it?"

Clark didn't answer but Beasely grunted.

"Maybe opening up a new field for his protection agency," he said.

"Harry Freed was killed on this road," Clark said coolly. "He was driving toward Eaton Rapids. Now a storm has destroyed an entire section in the same direction. That could mean that Freed was stopped while following the professor."

The miles were clicking away smoothly. On the wide drive near the bridge where Harry Freed had died, a huge truck passed them, going in the opposite direction. Along the side of the trailer were the words, Eastern Trucking.

Harry Freed had known something about that truck and its passenger. Something that might have been a key to the mystery of Professor Cyclone.

Harry Freed was dead and Professor Cyclone was headed safely toward home.

CAPTAIN DEEMS CLARK guided the police car carefully down the

rutted road, following heavy tire treads that had already dug

deep into the soft clay.

"I understand it's only a small section," he said meaningly. "About eight houses, like that first small storm at Bath."

Beasely growled something about, "Only a beginning," and Fred Sands frowned.

"That's the way Professor Cyclone seems to operate," he said. "He scares the daylights out of some, then comes in and collects the dough from the rest."

Sands was worried about something. Something he had noticed this morning in the heavy dust along the edge of the bridge. Tire tread marks. Marks that a heavy truck would make if parked there. Someone may have had tire trouble and used the broad concrete strip to change a tire. But that didn't satisfy him.

They were five miles into the back country now. Sands wondered why a large truck had come in here. Had chosen this narrow, dead- end country road. Even as he was worrying about this, he noticed that the tire marks turned off abruptly into a corn field.

"It must be only a short way now to where the storm struck," he said.

Clark turned quickly.

"Just over the next hill," he said. "How did you know?"

Sands wondered himself. It was a long shot, but worth a gamble.

"I've got an idea," he said. "Drop me off here and pick me up when you come back."

Clark stopped the car without hesitation. Sands climbed out into the road.

"We're going to find out if Professor Cyclone came through here before the storm," Clark said grimly. "It won't take more than half an hour."

"Good." Sands stood away from the car and Deems Clark started the motor. "I'll try to be here. If I'm not, wait for me."

"Damned if I wouldn't like to know what you got on your mind." Nick Beasely scratched his ear. "So far, I can't get a glimmer."

Sands shook his head.

"Probably I'm all wet," he admitted, "But, if I'm not, I'll tell you everything when you come back."

Clark's car moved over a little rise and dropped out of sight into the valley beyond. Sands turned, walked back several hundred feet to the spot where the truck wheels entered the field. He wondered if the trail ended behind some farmer's tractor. Still, he'd seen tires like these before. They weren't usually used on anything but the big jobs.

The trail led clearly down a small lane, turned and skirted the corn field. Carefully Sands followed it through a small woodlot. Ahead of him he could see where the truck had parked. Several two-by-fours had been pushed under the wheels. The grass was covered with grease. The limbs of trees had been snapped off about ten feet from the ground.

That indicated that a large truck had come through here. But why had it parked back here in the woods?

THEN the full meaning of his discovery flashed on Sands. To

the west, in the direction Captain Deems Clark had driven, every

tree, every bush was uprooted and flung in the opposite direction

from which the truck had been parked.

A giant wind machine!

No, that was impossible. No fan in the world would create a cyclone. Yet, Professor Waldon—or Cyclone, as he seemed to delight in calling himself— had always been interested in wind currents and what caused them. He had succeeded in breaking down and controlling atoms. Thus he had tremendous energy at his disposal. Had he succeeded in inventing a machine so compact that it would fit into a truck, and yet so powerful that it could stir up high and low pressure areas strong enough that a twister might result?

With Professor Waldon, it might not be impossible. Fred Sands remembered him as a man well ahead of his colleagues in every branch of his field.

But the truck?

It was fairly clear in Sands' mind now that whatever Cyclone possessed in the manner of machinery was housed in the body of a huge truck. A truck large enough to sink deeply into the field and high enough to knock branches off well above the ground.

He was disturbed from his thoughts by the sound of Captain Clark's horn blowing back on the road.

He hurried back across the field.

"Find out anything from the farmers?" he asked, before Nick Beasely could question him.

Clark nodded.

"I'll give you the story. It's short and not sweet. All seven men who lost their farms last night had met Professor Cyclone and refused to pay him money. Now, what's your story?"

Sands frowned.

"I want to stop on the Grand River Bridge when we get there," he said. "Then I think I can give you the whole story, at least as far as it goes."

IN ten minutes the police car drew up on the opposite side of

the bridge from the spot Fred Sands had discovered the tire

tracks. The three men crossed the concrete. Sands bent low over

the dust and sand that had been thrown aside by passing wheels.

The tracks were still clear, but very faint. The tread was

identical to the one he had followed into the field. He

straightened.

"I'm sorry I had to be the one to find this," he said, and he meant it. "I hate to do anything that will harm Frances Waldon, but I think we're ready to close in on the professor."

Clark was on his haunches studying the wheel marks.

"I'll be damned," he said, as understanding dawned on his face. "Those heavy tracks on the road back there? The same ones?"

Sands nodded.

"I think I've got it figured out," he said. "Professor Cyclone must have some sort of a wind-making machine mounted in the trailer of that truck. Last night Harry Freed followed him out here. Cyclone knew he was being followed. He doused his lights and parked in the darkness on the side of the bridge. Somehow he stopped Harry's car, recognized him and killed Harry. He pushed the car into the river. Then he drove into that field, hid in the woods and started a disturbance that caused that cyclone.

"Do you remember that as we were driving toward Eaton Rapids we passed an Eastern Trucking job headed for Lansing?"

Clark nodded.

"Faintly," he said. "About here, wasn't it?" Sands nodded.

"Eastern Trucking runs only one truck through here. It stops at the woollen mill in Eaton Rapids. Call them and find out if a truck stopped there this morning. If it didn't, we've got our party. We'll have to locate an Eastern Trucking job with a tire pattern like this one here and back in the field."

Beasley started muttering under his breath.

"Sounds reasonable, doesn't it, Sheriff?" Clark asked.

Beasley exploded with indignation.

"Me, I been sheriff at Bath for thirty years," he said. "Damned if that truck couldn't have run over me, and I'd never guess what it was for. What the hell we waiting for? Get those tire patterns photographed, check with Eaton Rapids and let's go to work."

THE Eastern Trucking outfit at Lansing was located on a back

street near the river. Captain Clark was well known to the

warehouse boss and garage mechanics. In fifteen minutes he had

checked every tread in the outfit. Discouraged, he straightened

from the last wheel and faced the blackened, overalled chief

mechanic. Sands and Nick Beasley were waiting in the office.

"None of the trucks has gone out last night or this morning?"

The mechanic checked with his work sheet.

"Grand Rapids and Detroit trailers hauled in this morning. You've checked them both. Nothing went out last night except the truck to Chicago. I called long distance. It got in there right on the nose. Checked in at every way-station on time. No sir, Captain, it couldn't have been one of our trucks."

"But the name, man? It was printed just the same way these are."

The mechanic shrugged.

"That would be easy," he said. "Any one trying to copy us could do that job. You take when a man stops driving for us, for example. We give him a buck so's he can paint out our name the first thing. Some of 'em don't do it for a long time. We have to sic the cops on them sometimes. If a driver gets in an accident and is using our name, the insurance company comes down on us like a ton of bricks."

Clark nodded.

"By the same token, if a crook was using your name for bootlegging or something worse, he'd be able to push a lot of suspicion in your direction?"

The mechanic nodded.

"That's right. Now you take just last month, one of our men quit. I know for a fact that he didn't repaint his truck. He's a farmer northeast of here. I talked with him this afternoon, and he said he's been busy putting in late crops. Promised to have the name changed right away."

"You saw him—here—this afternoon?" Clark's eyes narrowed.

"Downtown," the mechanic corrected him. "Says he drove down to Detroit for a load of last year's corn."

Clark grasped the other man's arm tightly.

"His name?" he said. "What's his name and address?"

The mechanic frowned.

"Freed," he said. "Yeah, that's it. Jack Freed. Owns some land over near Bath. Quite a lot of farmers own trucks and drive for us part time."

CAPTAIN DEEMS CLARK seemed in danger of blowing up. His face

turned a chalky white and his lips straightened into a firm

bloodless line.

"Why in hell...?" he started slowly. Then, "Jack Freed! Well, what do you make of that?"

Sheriff Nick Beasely and Fred Sands were waiting anxiously in the office when Clark went in. Clark went directly to the phone, dialed East Lansing and contacted the radio man.

"Browne," he said in a queer tight voice. "I want you to put out a state wide alarm. Pull every man off his regular route and start him scouring the back roads. I want to pick up a truck." A moment of hesitation and Clark smiled a little grimly. "Yes, I know there are lots of trucks. This one will either be well hidden in some barn or back street around Lansing or it will be on the highway. If it's on the highway, it will be splashed with fresh paint. Yeah! If they find a freshly painted truck, have them dig underneath to the original color. The words Eastern Trucking will be hidden under the fresh stuff. Got that?"

He listened carefully until the message had been repeated back.

"Yes," he said. "That's all, but give it everything you've got."

He hung up and turned to Beasely.

"Got something?" the sheriff asked.

"Plenty," Clark said. "Sheriff, how did Jack Freed come out in that cyclone damage? Was he insured?"

Beasley's eyebrows lifted.

"Perfect," he said hesitantly. "That is, he wasn't covered by insurance so far as I know. Seemed to have some money saved. He's all built up again. The house is better than ever."

Clark nodded his head.

"The others?"

"Well," Beasely went on, "not so good, most of them. Lot of them poor farmers up there. Don't know what some of them would have done if the Red Cross hadn't stepped in."

Clark had entered some notes in his notebook. He put the book back into his pocket and started tapping the top of the desk with his pencil.

"Didn't it ever seem funny to you, Sheriff, that Freed could put his son through college the hard way, and yet have money to start rebuilding so soon?"

Beasely shook his head.

"Never gave it much thought," he admitted.

CLARK slipped the pencil into his pocket, brushed his knees

where he had been kneeling on the garage floor and started for

the door.

"Jack Freed," he said over his shoulder, "used to drive for Eastern Trucking. He was here in town this morning. I think I've got a pretty good idea where he was last night."

"Wait a minute." Sands had caught up with the Captain. They stood at the curb as Clark inserted the key into the car door. "If Freed was on that truck, he wouldn't kill his own son."

"That bothers me a little," Clark admitted. "But Professor Cyclone had to have a driver and a helper to get him around the country. He had Freed behind a very bad eightball. Suppose this machine would look a little odd to haul down the highway in an open car. Suppose Cyclone found out Freed had a truck and offered him more money than he had ever seen before to mount the machine in his truck and become a partner? If Freed was driving last night and Cyclone killed young Freed, perhaps his father couldn't tell who the man in the car was?"

"Don't sound like Jack Freed," Nick said. "Not killing his own son."

Deems Clark climbed behind the wheel.

"No," he said slowly. "Freed might go a long way to make money, but if Cyclone killed his son, Jack Freed is going to do a lot of thinking when the State Journal releases the story of Harry Freed's murder in the afternoon edition. I think, Sheriff, there'll be some fireworks around Bath when Freed reads that paper. Maybe we ought to be there."

"Maybe," Beasely said, and got into the car quickly. Fred Sands hesitated, then backed away.

"I think," he said, "I'll take another angle, if you don't mind. Frances Waldon has to know about this sooner or later. It's reached the point where I'd better have a talk with her."

His voice was flat, emotionless. Clark stared at the younger man with unmasked pity in his eyes.

"That's your business," he said. "I'm sorry, Sands, that you had to get mixed up in this."

Sands stiffened.

"I'm not," he said. "I've helped and I'm damned glad of it. Professor Cyclone has it coming to him. Harry Freed was a good friend of mine. I think Frances will understand. Good luck! I'll try to get to Bath if you need me."

"We won't," Clark said, and stepped on the starter. "We'll have a police net around the center of the state that will catch the man we want. No one's going to get hurt, unless he's got it coming to him."

"MEN," Captain Deems Clark said, "we're ready for the

roundup."

He hesitated, removing a stack of typed reports from Sheriff Nick Beasely's desk, and placing them before him. Beasely's office was overflowing with Michigan state police. They stood in lines around the room, some of them making notations as the captain spoke. Nick himself, a little bewildered at entertaining so many uniformed men in his office, sat near Clark. His eyes were focused on a large fly that buzzed outside the screen.

"We've found our men, and we know how to trap them. We've taken a day to set that trap. The difficulty in making the trap work is this: Professor Waldon is undoubtedly the man we are after. We've traced him carefully from the first. Our trouble lies in proving beyond doubt that Professor Waldon, or Cyclone, as he calls himself, is responsible for these storms that have ravaged parts of the state. A man like Professor Cyclone hasn't any heart in his body. If he escapes us this time, God knows when we'll get another chance. He has a machine. What it does we all know. How in hell it does it, I don't even dare to guess. Needless to say, if he suspects us, he'll turn the power of that thing loose and destroy any man who comes near him."

Clark stopped, picked up the first sheet of his file and turned it over.

"Don't mistake this as a routine assignment," he continued. "We've talked with ten farmers just outside Bath. They've all been approached by Cyclone and they've all paid him money for protection. I've used the power of the entire force to make them come over to our side. I've promised them that if they defy Cyclone and make him carry out his threat to destroy their homes, we'll catch Cyclone before he can act. Is that clear?"

A murmur of assent arose and Clark continued.

"Every road is watched. Cyclone can't move anything into the district without us spotting him. When he does, we'll check on every move and close in before he has a chance to use this invention of his. Every man knows his post. All of you hold the fate of these farmers in your hands. It's up to you to see that their homes remain intact. Any questions?"

A sigh of agreement, then silence again as though every man had heard enough and was ready to get started.

"All right," Clark said. "Dismissed. Leave the building in pairs. Spread out and make yourselves scarce. I don't want Cyclone to get a tip-off on what's going to happen."

FRED SANDS drove slowly down LaPeer Street in Lansing, until

he reached the green bungalow where Professor Waldon and his

daughter lived. He went up the steps to the porch and knocked on

the door. No answer. Sands tried again, then went around the

house and tried the back door. The house was locked up

tightly.

Discouraged, he was about to leave when he noticed a slip of paper under the back door. He reached down, picked it up and his face registered disgust. A milk bill.

He was about to replace it under the door when he saw the faint tracing in the printed side of the bill. Turning it over he noticed two words traced hurriedly on the blank side. Someone had used a sharp instrument, perhaps a long fingernail to trace the message: Bath. Hurry!

That could mean only one thing. The Professor had gone to Bath. Frances had either been forced, or had volunteered to go with him. Her message indicated danger—fear.

Frances, Sands thought with a measure of relief, must know more than he had guessed. She was with her father now. Only he, Fred Sands, would be expected here by Frances Waldon. Then the message was meant for him and written hurriedly when the professor hadn't suspected. He folded the note quickly, pushed it into his coat pocket and ran to the car. By county roads Bath was only a few miles northeast of Lansing. But how would he know where to look when he got there?

Sands gave the car everything it could take, settled back behind the wheel and prayed that he wouldn't be stopped. When he passed East Grand River Avenue on Highway 27, the speedometer read eighty-five. He didn't stop for lights. A fine would be much easier to handle than another possible murder. There was no doubt in Fred Sands' mind that Frances was in grave danger.

Professor Cyclone had murdered once. He was crazy. Crazy in a Cold, scientific way that made even the murder of his own daughter possible. Frances Waldon had learned too much about her father's work.

PROFESSOR WALDON was speechless with rage. A great change had

come over him since that first visit to Jack Freed. A change that

brought an ugly glitter to the mild eyes and left his lips parted

so that the yellow teeth were always visible. He backed away from

the man on the tractor, his hand clenched around the grip of his

cane, blood drained from his face.

"You—you dare defy me after what has happened to the others?"

Clare Cragg had been farming his eighty for a good many years. Right now he wasn't quite sure of himself. He wondered if Captain Deems Clark of the state police could really give him the protection he had promised. Cragg wasn't a man to go back on his promise to the law. He leaned over from his seat on the tractor and stared into Waldon's fiery eyes.

"I already paid you three thousand bucks to leave me alone." He remembered Captain Clark's orders. "You see, Professor, a bunch of us farmers has got together. We figure them cyclones was natural. That you didn't have nothing to do with them. You're just collecting dough under false pretences and none of us is gonna pay."

He hoped, as he watched the little man in the dark coat get ready to shout again, that he had made the story sound right. It wouldn't do for the Professor to know he was laying a trap.

Professor Cyclone seemed to shrink away from the tractor. A rage had taken hold inside him. A rage that made him burn with hate for the entire world.

"You can't fight me." His voice was deadly calm. "No one can fight me. If I wanted to I could destroy you all."

His words rose gradually until he was screaming. "I could destroy the state, the country. Perhaps the world."

Cragg had a hard time to act then. He chuckled and he flattered himself that it sounded like the real thing.

"Go ahead," he invited. "Play God. Tear the hell out of us. It oughta be something to see!"

"It will be!" Professor Cyclone shouted. "I'll—I'll break every..."

He fell abruptly silent, turned on his heel and hurried across the yard toward the road.

Cragg started the tractor and rolled away across the field. He thought he caught the movement of someone in the car that Cyclone was driving. He couldn't be sure, but it looked like a woman's hat.

FRED SANDS reached the Bath Road where it branched off Highway

27. As he slowed for the turn, two state policemen stepped from

the bushes with stubby sub-machine guns. Sands stopped, then

recognized one of the officers who had helped pull Harry Freed's

car from Grand River.

"We meet again," he said.

The cop looked doubtful. Then he grinned, lowered the gun and offered his hand.

"Cap tells me you're getting to be quite a detective," he said; then, to his companion: "Put down the tommy-gun, Pete. This is Fred Sands I was telling you about."

Pete Shilland came forward, grasped Sand's hand, then stood at one side, his eyes on the road behind.

"Say," Sands said, "what's the game? Get a lineup on something?"

His friend with the tommy-gun looked puzzled.

"Ain't you heard? Cap Clark's setting a trap for this Cyclone guy. A lot of farmers have told the old boy they ain't giving any more money. When he cracks down, we'll be there to get him."

Sands sat still, thinking.

"You didn't see an old Ford, about a 1932 model, pass here earlier in the day?"

Pete Shilland looked around a little startled.

"Sure," he said. "Sure we stopped one. Girl driving and a nice-looking old gent sitting with her. Remember, Ed?"

Ed scratched his chin.

"Damned if I don't!" He flashed a startled look at Sands. "Why?"

"First," Sands asked, "tell me what time they went by, what you said to them and anything you can remember about the pair."

Pete Shilland stepped closer to the car.

"I remembered 'em because they passed just at noon. I was eating a sandwich at the time we stopped them."

"Yeah," Ed offered, "that's right. The girl said they were going north. Had a farm up there somewhere. The old guy wanted to ask a lot of questions and all that. Wondered why we were here."

"Yes," Sands said. "I should think he might. What did you tell him?"

"Cap Clark said we were to tell any one who asked that we were looking for a bank robber from Detroit. We got a fake description and everything."

"And you didn't have a description of the old man in the car?"

A light of understanding started to dawn in Ed's eyes. He stared at Shilland and then back at Sands.

"You don't mean that nice old gent might have been ..."

"No mights about it," Sands said. "You let Professor Cyclone go through the blockade. I only hope to God that he didn't suspect!"

"I'll be damned!" Shilland was shocked. "The girl must have thrown us off. She didn't look like a crook."

"That's what I hope," Sands said, and there was a prayer in his voice. "Was Professor Cyclone carrying a cane?"

Ed nodded.

"Sure, he looked kinda feeble."

Sands' smile was a little strained.

"He had that cane handy when he was talking, didn't he?"

It was Shilland's turn.

"Yeah, got out of the car and stood there while he talked with us. Reached up and flicked a piece of lint off my shoulder."

"I thought so," Sands said. "If you see that cane again, you'd better go in with your tommy-gun wide open. Harry Freed died with the snout of that cane in his face. If you'd given the wrong answer this noon, you might both be dead now."

"God," Ed said, and looked as though he was going to be sick. "I'd better radio Cap right away."

He turned and ran back into the brush where the prowl car was hidden.

Shilland continued to stare at Sands, his hand creeping to the spot on his shoulder where the cane had tapped him. His hand was shaking.

"You mean the guy that was burned to death? That cane did it?"

"Only a guess," Sands answered. "But I think, on the strength of what happened here, it's a good one. You might as well follow me into Bath. You're no good here."

"Yeah!" Shilland still had that faraway look in his eyes. "I guess we better. Things should start popping over there, huh?"

"Popping isn't the word for it," Sands said with ice in his voice. "I'll see you at Bath."

It took him just a quarter of a mile to reach eighty-five. The car took the road like a swallow.

"WAITING!" Captain Clark said in disgust. "I'm getting damned

tired of it."

He strode the length of Beasely's office, and slumped down into a chair.

"No more reports since I came in?" Fred Sands asked.

They had been sitting in the darkened room since seven. The clock, outlined by a light that reflected from across the street, read twelve-twenty-five. After midnight, and no news.

"No more," Clark said. "Nick, what in hell are we going to do?"

Nick Beasely stirred as though he had just awakened. That wasn't true. He had sat very still over his desk, dreaming of what could happen to those poor devils who had defied Cyclone. Wondering where the storm would strike.

"Damned if I know, Deems," he said in a dispirited voice. "Damned if..."

"Well." Sands stood up. "I'm doing something right now. I'm going to look over Jack Freed's place. The last we heard, this man Cragg reported that Cyclone left his farm and that there was a girl with him. There are two possibilities that don't sound very pleasant. Freed might have murdered Cyclone when he found out what happened to Harry."

"Possibly," Clark said, "but more likely Cyclone took care of Freed if the old man got tough. I've got three hundred men within a radius of ten miles of here. Why in hell don't some of them report at least one suspicious action?"

"Then there's that truck," Beasely said. "It's got to get through the blockade ..."

"Wait." Sands walked to the door. He had tried desperately to push Frances Waldon from his mind long enough to think clearly. "The truck. It belonged to Jack Freed and he had no reason to suspect that we'd traced it to him."

Sands whirled on Clark.

"At what time did you establish the police blockade, Captain?"

"About eleven this morning," Clark said. "You... don't think...?"

"Why couldn't he have driven up here last night and hidden the truck in the first place he'd normally think of, his own barn?"

"That's right!" Beasely shot to his feet. "Freed rebuilt his barn in a hell of a hurry. There'd be plenty of room."

Clark drew his pistol from the holster, squinted at it as he snapped the chambers around, then slipped it back.

"We won't wait any longer," he said. "The car outside can get in touch with me by radio. We're paying a quiet visit to Jack Freed."

JACK FREED, holding a folded newspaper in his hand, stormed

across the back yard and into the new barn. Parked at the far end

of the structure was his big, newly painted truck. Beside it,

small and dilapidated, was Professor Cyclone's Ford. Freed felt

white hot anger inside him. Unreasoning anger that clenched his

fists and made his mind turn back swiftly to his first experience

with the professor.

Fred ran across the newly-laid floor toward the truck. Cyclone was a damned little liar. A cheap, two-bit murderer. He had somehow found out that Freed had a truck. He had come to Freed after that first storm and offered him ten thousand dollars for the use of the truck with Freed himself to drive it. Freed had no choice. Besides, it looked like nice business. He could rebuild his farm and have a job again. All he had to do was drive, see nothing and keep his mouth shut.

But that night outside of Lansing when he had parked on the bridge. Freed knew Cyclone killed a man that night. If he had only known that it was his own son who had died. He had never seen Harry's car. The boy bought it in Lansing.

Fred shuddered. He couldn't have been expected to recognize Harry's body, not the way it was...

He shook his massive head slowly. A small, neat door had been built into the side of the trailer. Freed opened it, stepped upon a box and went inside. He closed the door, the bright lights within blinding him for a second. Then, leaning back against the closed door, his eyes widened.

"What the hell?" he said. "You got a girl here?"

One entire side of the trailer was fitted neatly with banks of switch controls. Large and small tubes sent forth a faint glimmer of light, and gauges evidently meant to record certain air pressures. In the back end, heavy, lead tanks, reaching to the ceiling, looked like oversized sausages. Professor Cyclone had been seated at a small desk, his back to the door. Frances Waldon sat at the front end of the trailer, her legs and arms bound to a chair. She seemed bewildered, unable to understand what had happened.

Professor Cyclone turned slowly, a foolish grin on his face.

"The girl? Oh yes, my daughter. Well, you see, Freed, my daughter has finally found out what a powerful, what a very powerful man her father is. She wasn't safe left alone. Now she isn't safe anywhere. Frankly, I'm wondering just what to do with her, Freed."

Freed tried to suppress a shudder. The old guy was nuts all along, but now he was getting simple. Simple, but dangerous.

"Look," he said. "I'm all done with this. What the hell you and your kid do ain't my business. I'm finished."

Professor Cyclone grinned. It was a wolf's grin, without humor. His eyes glistened in the light. He turned full around, his cane resting on his knees.

"So," he said, "you are going to quit? Who told you you could? When did you make all these plans?"

FREED whipped the newspaper from behind him. He held it close

to Cyclone, so that Harry Freed's picture was close to the old

man's eyes.

"Body Found in Grand River," Freed said with emotion shaking his voice. "You know who put it there, don't you, Professor?"

Cyclone swore.

"The meddling fools," he said. Then he regained his former calm. "Why Jack, of course I know. We both put it there. You wouldn't want anyone to know you killed your own son?"

Freed lost his temper completely.

"You crazy, goddam loon!" He lunged forward.

Too late. He heard Frances Waldon scream and felt red hot flame searing his face. He clutched at his eyes, moaning and fell forward on the floor. The flame stopped eating at him. He heard Professor Cyclone chuckle.

"You never felt the power of my cane, did you, Freed? Harry felt it."

Freed continued to roll on the floor, sobbing with pain, his fingers clawing at the scorched, raw flesh on his face.

Frances Waldon started to struggle, trying to release herself from the chair. Professor Cyclone went to her side. He stood looking down at the girl. Any pity or love he may have had for her had vanished. He was completely, terribly, calm.

"You little fool!" He slapped her face. "Sit still or I'll give you the same treatment."

He pointed the cane at her. Frances waited, suddenly motionless.

"You're insane," she said. "Completely insane."

Professor Cyclone chuckled. He turned and limped back to the desk. Once in his chair, he faced them: the girl and the faceless, writhing object on the floor.

"A fine pair, you two. You dare defy the most powerful man on earth. Fools."

He toyed with a chart he had picked up from the desk top.

"Today a few men also defied me." He was speaking as though to himself. "I am powerful enough to wipe an entire state from the map. Yet they laugh at me."

He took the chart with him, pushed the chair to the opposite side of the trailer and sat down before a board covered with switches and dials.

"Professor Cyclone has only started," he murmured. "Perhaps, Frances, you remember that I always had an uncanny understanding of wind storms and how they were formed? A cyclone is comparatively simple. A violent wind blowing spirally inward from a large high pressure area to a small calm area where the barometric pressure is low. You couldn't understand that. You couldn't understand how by the use of the cosmic rays, the atoms of the atmosphere could be so directed by radio that they would produce such a storm. Yet, in those energy tanks, I can build up a storm that, if stirred up in full force, would cut a swath of terror through the entire country."

He watched the girl's eyes widen in terror.

"Don't be frightened, girl," he said. "Tonight I will destroy only those who defied me this afternoon. You are safe. I may have to keep you prisoner until you see things my way. After that, we will both be safe from fools like Freed who think they can fight Professor Cyclone."

DURING this time, Jack Freed had grown quiet. He lay on his

back, sightless eyes turned upward. Frances looked at him once,

then turned away quickly.

"You do not like the handiwork of my little weapon?" The professor chuckled. "Neither did Harry, his son. I'm an old man, Frances. That cane is another smaller touch of my genius. A combination of atomic pellets that, when exploded, force burning energy from the barrel. It proves handy, especially because such a weapon is completely unsuspected."

He watched his daughter anxiously for a minute, then seeing that his talents were wasted on her, turned away with an exclamation of disgust.

He leaned over the controls and turned a switch on the board. At once the trailer was alive with a low hum. It built up gradually as they sat there, until a steady roaring sound came from the valves on the lead storage tanks. At last, seemingly satisfied, Cyclone started to regulate the dials, checking the map-chart carefully as he did so.

"Energy can be hurled in any direction," he said as he worked. "These dials, set according to a carefully prepared chart, will send a storm into any given area. I can pick out one acre of land if I wish, send a cyclone tearing into it, then make it lift into the sky to spend itself after that acre has been laid to waste."

The girl was fascinated in spite of herself. She leaned forward in her chair.

"You—you can't destroy again. Please Dad, think of those men, their families. Their farms are all they have in the world."

Tears of genuine pity were in her eyes.

"Shut up," the old man snapped. "I know now that it would be better to put you out of the way. Perhaps, after I finish..."

The sound within the trailer was steady now, drowning out any other noise. The tubes, some of them hardly larger than a finger tip, others two feet in length, were in rows, according to size. The largest ranged against the floor of the truck. The smallest were up close to the roof. All of them were flashing steadily as though the power had now reached every filament.

"There will be no violence here," Cyclone shouted above the sound. "You need not be frightened when the air becomes suddenly dry. There will be a vacuum for a second, then plenty of air to breath. It will be hot and dry. The force will generate in the air where I have set the dials. It will start several miles from here."

Frances remained silent, still as a carved figure.

Cyclone's slim fingers reached for the release buttons.

They paused in midair, and he whirled in his chair, coming to his feet with the cane aimed at the door.

FRANCES had not heard the door open. Now she saw the crouched

figure of Fred Sands standing in direct line with the cane

muzzle.

A scream of terror escaped her lips, but it was drowned in the noise that the cyclone generator made. She did not see Jack Freed come to his knees slowly behind the tense form of Professor Cyclone. Freed knew who was in that doorway. He could see Cyclone through a mist of suffering. He knew that Cyclone would release flame in Sand's face at any moment.

Cyclone's arm jerked up. His fingers closed about the grip, just as the crashing force took him behind the knees. He went down like a rock, the cane flying from his hand, a scream of fear on his lips.

The cane struck the bank of tubes and at once the humming of the cyclone storage tanks stopped. The circuit was broken. Glass shattered against glass.

"Get the hell out of there!" It was Captain Deems Clark shouting from somewhere outside the barn. "Here she comes."

Frances tried to struggle out of the chair and fell forward with its weight on top of her. She saw Sands run towards her, felt his fingers fumbling hurriedly with the rope.

Her father was screaming. He was on his back, Freed's arms grasped firmly around his waist. The two of them rolled over and over the length of the trailer.

Nick Beasely's head poked in the door. He was scared. His lips moved but little sound escaped them.

"No time... hell to pay..."

Frances was free now. She felt Fred's arms around her a second before he jumped from the door of the trailer and hit the barn floor on the run. She buried her head in his chest, feeling his heart pounding as he reached the barn door.

She wondered why he didn't put her down. Then, daring to open her eyes once more, she saw the funnel-shaped twisting cloud that was tearing toward them across the field and a scream parted her lips.

Sands was trying to reach the house.

The wind tore at them pushing them away from the door.

Deems Clark appeared around the corner of the house and pushed them inside.

"The cellar," he shouted, but his words were whipped away before they could hear him.

Sands reached the cellar stairs and stumbled down them. He put Frances on her feet. With Clark's help, they managed to reach the cellar wall closest to the onrushing cyclone. Beasely had got there safely and was staring with wild eyes out the broken cellar window.

"Good God," Beaseley's voice was filled with awe. "Look! Out there!"

Professor Cyclone had managed to escape Fred. He had reached the yard and was trying to make his way across it. He had his cane once more, using it to pull himself forward as he lay flat on the ground. The professor had reached a point half way between the house and the barn. He lay flat on his face, the cane pushed deep into the soft turf. His face was pressed to the grass.

The funnel of the cyclone rushed forward, debris twisting about in its black center. It reached the yard, pounced on Professor Cyclone's body and sucked it up into the air.

Professor Cyclone didn't seem powerful any more. He was no more than a straw, picked up with coat-tails waving wildly, and tossed with terrible force against the barn. Then the barn itself crushed in, and with a thunderous roar, ripped apart, board by board.

In the blink of an eye Professor Cyclone, the barn itself and all that remained of Cyclone's invention were broadcast like seed across the field.

THEN the wind was gone and the air was still and electric,

accenting the tiniest noise. Sands turned to Deems Clark and saw

that the captain's eyes were on something across the way.

The captain was viewing the last resting place of Professor Cyclone. His frail old body was firmly enmeshed in a chicken-wire fence on the far side of the field. The cane, clutched in one stiffened hand, hung down as though to keep him from falling.

Sands helped Frances Waldon to her feet, burying her tear- stained face against his shoulder.

"That was one cyclone," he said in a low voice, "that the Professor hadn't planned on."