RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

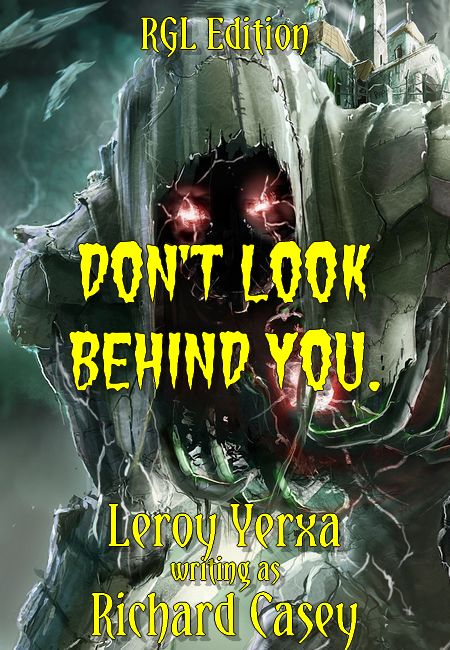

Amazing Stories, September 1945, with "Don't Look Behind You"

Something...some THING, was there behind him. He knew t, but dared not turn to look.

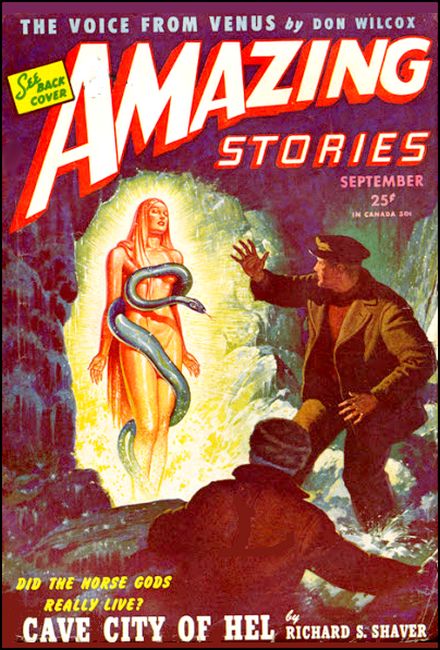

"I know there is another world, peopled by something

unhuman," wrote Wallace in his book—and he was right!

MARIE WALLACE moved quietly down the darkened hall and hesitated at the library door. She looked in at the profile of her father at the big desk. She knew that he must be tired. Her hand, resting on the panel of the partly opened door, slipped and produced a sudden sound against the varnished surface. The old man in the study whirled in his chair, coming half out of it, his body twisted in a tense, frightened posture.

"Marie?"

The girl was puzzled.

"It's I, father. What on earth is wrong with you?"

She saw the wild, frightened look on his face, the distended eyes that softened slowly and became normal.

"I'm—I'm jumpy, I guess," he admitted, and arose. He was tall, but very thin and tired looking. He came toward her, the frightened expression replaced by an uncertain smile. "Guess I need some rest."

Marie Wallace went into the library, meeting him halfway, her arms outstretched to rest on his thin shoulders.

"Dad," she begged, "out with it. Something's been hurting you. Something you need to share with me. I'm the only one now, you know."

He stood quite still, studying her grave lovely face, wondering how much he dared say. She was right. He'd have to tell someone soon. Tell—or keep that horrible pain bound up inside him until it drove him mad.

His eyes evaded hers. He returned to his desk and slumped down in the deep leather chair. Marie seated herself on the edge of the desk, her slippered toes touching the carpet, the blue robe trailing softly over the dark wood.

"Is it the book?"

She knew the book worried him a lot. It had gone swiftly before mother died. Now it was being written at a much slower speed—each page a week's work in his mind.

He shook his head.

"The book has nothing to do with it," he said. She thought that his voice was almost stubborn, as though the book might be playing a part and that he refused to acknowledge it. "It's—it's something far more subtle, more devilish than that."

He was going to tell her now. She knew he was. She saw the skin at the corners of his eyes wrinkle and watched his fists clench slowly.

"It's so damned childish," he blurted out. "Like a nightmare."

She waited. The room was cold and she drew the robe closer about her white throat.

He looked up at her.

"Marie," he said simply, "thousands of people get the same feeling. I used to have it as a child. It's a very simple thing, really. It's that horrible feeling you get sometimes late at night that something or someone is staring at your back."

She smiled.

"I don't quite understand." He frowned.

"But you do. That is, you will, if I can say it the way I want to. Let's say that you're curled up with a good mystery book some night. You hear strange, imaginary sounds in the room. Then, suddenly, because your subconscious mind forces you to, you look behind you."

She nodded slowly, remembering the fright in his eyes when he had looked around at her.

"Go on."

He shook his head.

"There isn't so much more to tell. It's the simplest thing in the world. Your mind is wrapped up in some mystery, or you're alone, and you have that urge to look around suddenly, as though to discover something behind you. Of course it's all quite silly. There is never anyone there."

"I know," she nodded. "I've done that. Everyone does it dozens of times in their life. It's—it's sort of a little games of nerves we play with ourselves when we're excited. Surely that isn't what you wanted to tell me. You're too old to be frightened by that!"

HE placed both hands on the desk before him and flexed the

fingers slowly, staring at them. He nodded.

"That's exactly what I'm trying to tell you that I am frightened of," he said. "You see, Marie, in only one respect does my experience differ from the others."

He was silent for a moment, and she felt herself go rigid from head to foot. She knew what was coming. Knew, somehow, what he was going to say. If he said it, it would mean that her own father was quite mad.

"When I turn around," he said, "I actually see something. Just the tiniest bit of a disappearing monster. Just the shadow of something horrible."

Marie slipped quietly from the desk. The library now was more full of shadows. A place apart from the rest of the house. She wanted to take him out of it. Wanted to lock the door and lead him away.

She forced a smile to her lips, but her cheeks were pale and she could feel ice in her fingertips. She sat down on the edge of his chair and put an arm about his shoulders.

"But—you couldn't actually see anything, Dad," she said, trying to sound comforting. "You're tired. The book has been a tough assignment. Take a rest. We can go up to the lake for a week. By the time we get back, things will clear up."

His voice was cold and emotionless.

"If you're trying to say that my mind is affected, Marie, don't believe it. This is all quite real to me. I've studied the thing out carefully in my mind. I've turned around suddenly six different times this evening. I could feel cold, deep eyes staring into my back. Each time, I saw that shadow. Saw a bit of something black, grim and savage, as it faded from the corner of my field of vision. It may be a man. It may be something far worse, but it's there and no one can convince me otherwise."

Deep in her heart she believed him. Her father was no fool. Neither was he an insane old man. His mind was one of the most brilliant in the country. He ranked among America's high ten philosophers and thinkers. Scholars around the world paid tribute to the quality of his brain.

But he was first and always her father, and she had to do something to get him away from this hell he faced.

She had a hard time to keep herself from turning around, to stare into the shadows behind the chair. She fought against the desire.

"Dad—let's get out of here."

He arose and went with her, arm in arm, down the hall and up to his room. She kissed him good-night tenderly and pinched his nose.

"Get a good night's rest, Dad. Maybe, if the sun shines tomorrow, we will find a brighter view of this old horror world you've created."

LEE CHALMERS climbed out of the coupé, found his gladstone in

the rumble seat and ran up the steps to the big white door.

Before he could use the old-fashioned knocker, the door opened

and Marie Wallace was in his arms. He spent several seconds

tasting her lips, decided she hadn't changed a bit in a week and

put her back on her feet once more.

"How's your Dad?"

Marie's eyes clouded, then she smiled.

"Come in and see for yourself. The book's almost done. Two or three more nights and it will be ready."

He nodded.

"Good," he said, and followed her in, admiring the keen silken flash of her ankles, the smooth sway of her hips.

"That company of mine is ready to spend ten thousand on advance promotions of 'Future World.'"

In the hall he dropped his bag near the stairs, for he had been here often and knew that his room was at the top of them. Marie turned and the smile was gone.

"Lee," she said. "Lee—there's something terribly wrong with Dad."

A lot of the sunshine went out of Lee Chalmer's life right then. Thus far this morning he had been a slim, blond young man with a great future at Milestone Publishers, and the sole possessor of a heart belonging to the loveliest young girl in Vermont. Now—what?

"What could possible be wrong with him? Last week he was as fit...."

She shook her head.

"Listen closely. He's in the study now. We'll have to go in in a minute because he heard your car drive in. He asked to talk with you. I don't know what he's going to say, but I do know you won't believe it, and I'm afraid, because I'm sure that every word he'll say will be true."

Chalmers flashed her a bewildered smile.

"You succeed in being very confusing."

"I know. What I'm going to say now will be even more so. You know Dad well. You recognize his ability and you've studied his habits for years. Perhaps you can help..."

She told him about last night. About the monster from the world of shadows. About the thing her father saw when he looked behind him.

WHEN she had finished the story, Lee Chalmers was no longer

smiling. He whistled very softly.

"And a thing like that, concocted in the mind of one of the world's finest brains. Could he be going slightly mad?"

"I thought of that," she admitted. "But if you'll check his manuscript, you'll never believe it. The book has never wavered from its course. Every chapter, every word, right up to the present, has been carried through with one thought to a uniform end. His mind is working brilliantly. Perhaps too brilliantly."

He stood there in the hall staring at her. He found a cigarette, offered her one and helped her light it. Their fingers shook a little. He admitted to himself that the story affected his strangely.

"A little too brilliantly," he asked. "What do you mean by that?"

A shudder passed through her body.

"Perhaps—clever men see things that aren't revealed to ordinary mortals like ourselves."

"Don't you believe it," he said. "I'm going to talk with him about the book. I'll get his mind off this dream stuff he's thinking about. You'll see. We'll take him out for some golf this afternoon and he'll forget all about it."

JAMES WALLACE looked up from his desk, laid his pen aside and

arose. He accepted Lee Chalmer's outstretched hand.

"Glad you could come up, Lee," he said. "I wanted to talk with you about 'Future World.'"

Chalmers sat down on the desk.

"Go ahead," he said. "It's a swell morning, the birds have been singing just for me all the way up from New York, and Marie says we won't have to postpone the marriage much longer. I'm very happy."

He wasn't. He was worried. Worried and a little frightened about what he had just heard.

Wallace sat down again a little heavily. He passed one hand over his eyes. He hadn't slept last night. He was tired. In spite of that, he managed a smile.

"You're good for me, boy. At times I might have stopped work on the book if it hadn't been for Marie and yourself."

"Thanks," Chalmers said soberly. "'Future World' isn't a new idea, but we've never had a really fine mind turn out anything along this line. Anything new in the later chapters?"

Wallace shook his head. He leaned back in the chair and stared at the ceiling. When he was working on, or thinking of the book, everything else became secondary. The book could almost be placed in capital letters and outlined in gold. It meant that much to him.

"The same," he admitted. "It sounds right, doesn't it? I am on the right track, am I not? I say that we will go on to a higher plane. That each time, instead of slipping a notch, civilization will go to a new and better world."

Lee Chalmers nodded.

"It isn't so much the outline of the thing that impresses me and the men I work for," he admitted. "The higher plane idea isn't new. In your case, however, we've found a mind that can delve into that world after a world, and offer clear, workable reasons for it being what it is. I'll always remember what you said when your wife died."

He paused, seeing a fleeting expression of pain pass over Wallace's face.

"Pardon me for reminding you of a painful moment, sir," he added, "but you told us that your wife was moving into a new and vastly more wonderful apartment that your own mind had prepared for her. That, in a measure, your own clear thinking had paved the way for her to move forward and upward to another better place."

Wallace nodded slowly.

"I think I'm right," he admitted. "It's amazing what contemplation can bring from the inner mind."

THEY were silent then, staring at each other, each with

something on his mind, each hesitating.

"I—I suppose we ought to have lunch," Wallace said. "Marie said I had to give up my work and golf with you two this afternoon."

He started to rise.

"Good," Chalmers said. He was relieved that neither of them had mentioned what they most wanted and yet most dreaded to talk about. "I'll call Marie."

He started toward the door, then heard Wallace gasp as though in sudden pain. He whirled around to catch Wallace standing by his chair, staring behind him at the blank wall.

Wallace came around again, slowly, his face drained of color. The two of them looked at each other. Chalmers grinned a little foolishly. He had been facing the wall. There was nothing there. Nothing.

"I thought..." Wallace said in a strained voice, then added, "No matter. I think I'll see a doctor. I'm having a little trouble with my heart."

Chalmers knew what the trouble had been. There, somewhere against a blank, cream colored wall, James Wallace had again turned to catch sight of his monster.

It couldn't have happened. There was something wrong with Wallace's mind. Something deep and sinister, Chalmers thought. He must have a long talk with Marie.

BUT his talk with James Wallace's daughter didn't come that

day. That afternoon they golfed at the Beechnut Club twenty miles

away, and it was dark when they started the drive home. He didn't

know how it happened. You never know. The pavement was slippery

because it rained a little just after six o'clock. The curve was

sharp and the lights on the other car were far too brilliant.

Lee Chalmers tried bard to hold his coupé on the slippery shoulder, then they were rolling over and over through space. The coupé landed on its top with a hellish crunching sound and everything was quiet. Marie started to sob. The lights were still on on the dash and somewhere gasoline dripped slowly. It might have been only water. Chalmers couldn't be sure.

He fought his way out of the upturned car, managed to get Marie out, then cursing silently, dragged Wallace's prostrate figure from the other side. By that time a state police car screamed down upon them and the night was alive with headlights. A lot of people were talking loudly, and all trying to tell what happened. Chalmers fought the pain as long as he could. He knew that his left arm was broken because he couldn't move it. He saw the deep, bleeding scar on John Wallace's cheek and hoped dumbly that it didn't hurt too much. Then someone made him lie down on the stretcher and he swore because they insisted on carrying him up the side of the ditch to an ambulance. He knew that Marie was sitting beside him in the ambulance, crying softly. He knew that her father was opposite him, with a white coated man working on that damned cut on his cheek. Then Chalmers passed out and didn't care any more.

JAMES WALLACE was impatient, for he had wasted three days away

from "Future World," and every day with the manuscript now was

precious. There had been the matter of the cut on his cheek. It

was still under a bandage, and it would leave scar tissue in a

heavy line from under his eye, down to his chin. Now it was red

and ugly. Marie had fortunately come out of the accident in fine

condition. Her nerves were better, now that Chalmers had his arm

in a sling and was coming along nicely.

Wallace hit the top of the desk with his fist. He wished that his nerves were better. The urge to turn and stare behind him hadn't troubled him for some hours now. He wrote swiftly and easier than he had for some weeks.

"Thus—man must go on to his reward, living each life in a more perfect existence, passing from one world to another. Perhaps that is the final explanation of the planetary system. Perhaps that is why we are unable to gather more than a rudimentary knowledge of what goes on up on other planets. Call it planet, world, or another dimension of life, we do, I have concluded, go on and on, upward and upward toward the light of divine knowledge."

He placed the pen carefully on the desk. A strange feeling crept over him. Here he was, after seven years of hard work, finishing his brain child. Seven years of cudgelling his brain for the correct answers, and now?

But what of that phantom from behind? Was there a message there?

He leaned back in his chair, his body shaking strangely. He felt light headed, almost giddy with the weight of the work lifted suddenly from his mind.

He wondered how a man would feel, after spending his lifetime and draining his well of knowledge to produce a certain set of theories, if he should suddenly find out that he had been wrong.

"What makes me like this?" he muttered. "What puts the doubt in my mind?"

He hadn't told Marie everything.

He had often turned quickly, seeking that elusive horror behind him, and he had recognized the features of a face. Not all the face but part of it. A dark, lopsided ear, perhaps, or a jutting, ugly chin.

IT was growing dark outside. Chalmers' car came up the drive

and halted. That would be Chalmers getting out, Wallace thought.

The door slammed slowly because Chalmers was cumbersome with the

bad arm.

Wallace looked at the pile the manuscript made. A neat white oblong against the mahogany of the desk.

He felt a presence in the room. He stiffened, his fingers clutching the arm of the chair. Tonight, more than ever before, he sensed the full horror of the thing. It wasn't Marie. Chalmers hadn't had time to come in yet.

"Don't look behind you," he whispered to himself. "Don't look..."

But he couldn't help it. He—couldn't help...

His head turned suddenly, and this time he saw more than the brief flash of a face.

He saw the full face.

He saw the face of a man, not living on a higher plane, but a man, if you could call him that, from a beastly, filthy underworld. James Wallace stared, because in that face he saw the loss of his work, the loss of his entire life's thought. The face had a scar. A white scar against dark, leathery skin, running from under the eye down to the chin.

James Wallace knew that, leaving as he was against his will, he was not going on to the higher plane he had dreamed of. The scales, instead, tipped the other way, and he was going down.

It was very dark and cold and he clutched his face with both hands and tried hard not to cry out as the pain stabbed at his heart.

"HEART failure," the doctor said quietly. He stood up and

started to put his things away in his bag. "I'll call an

ambulance. I assume you'll want him taken to town."

Chalmers had his good arm tightly about Marie Wallace's waist. He held her, staring at the straight, stiff old figure in the leather chair. Chalmers' eyes were dry and his face was twisted in pain. Pain that came from inside.

"Yes," he said. "Yes—that will be best."

The doctor went out into the hall. Chalmers could hear him asking central for a number.

"Marie," Chalmers said, "you'd better try to rest."

She wiped tears from her eyes. Her face was very pale and her eyes seemed larger than ever. She couldn't look at her father now. Couldn't look—ever again.

"I'll—go."

"Let me go up with you."

She drew away from him gently.

"No—Lee, I'd rather be alone. You—stay here until they come."

He nodded. He knew what she wanted.

She was quite steady when she went out. Chalmers could hear the doctor still talking on the phone. He felt a queer shudder pass through him.

Heart failure? Perhaps, if there had been a terrific shock to produce it. Chalmers thought he knew what the shock had been. The manuscript was here, but sometime after James Wallace died, the wind had whipped in and scattered the pages about the floor. Many of them were in the fireplace, burned, irreplaceable.

The position in which James Wallace had died caused Chalmers more concern than anything else. His head was turned in an unnatural position, and his eyes, full of terror even in death, were staring behind him at the wall.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.