RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

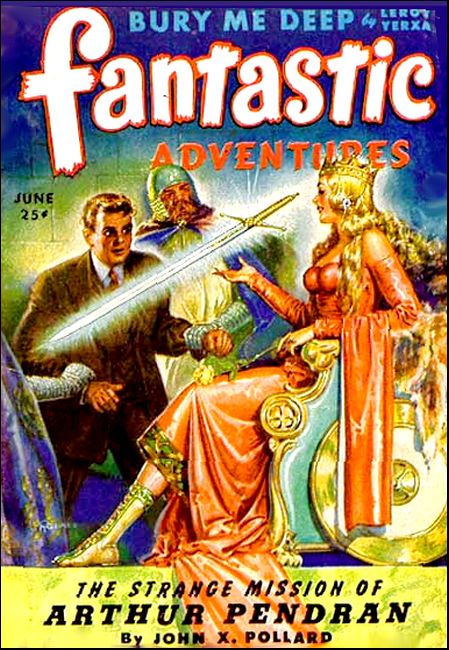

Fantastic Adventures, June 1944, with "Horn o' Plenty"

"HOT-LIPS" JOHNSON walked lazily out of Casey's Dance Palace, his trumpet dangling from his right hand, perspiration standing out on his black forehead. The parking lot was dusty and hot under a July Harlem moon. Hot-Lips stared around him, trying to find company for the few minutes he planned to rest. Inside, the boys were "grooving it on down" with the Two-O'Clock Jump. Hot-Lips snapped his fingers in rhythm with the music, and wandered toward the street.

"That you, Johnson?"

Hot-Lips stopped in his tracks, swayed around with the music and stared behind him. His eyes twinkled.

"How come I didn' see you when I stepped out?"

Charlie Washington, a little out of bounds in his tight trousers and sweat-shirt, grinned from ear to ear.

"Guess I and my old horn was listenin' to the jive hounds in there," he admitted. "Ol' horn kinda likes jive."

Hot-Lips looked puzzled.

"What you talking 'bout, tall, dark and handsome? What horn you talking 'bout?"

Charlie Washington backed toward his Ford that was parked under the window.

"My bugle-horn, of course," he said "Me, I got one of them bugle-horns on the car. Shore does like music."

Hot-Lips was a little worried about Charlie's condition.

"Ain't no horn can listen to music," he said. "You're crazy as a skeeter-bug."

Charlie Washington frowned.

"Ain't neither," he protested. "This ol' bugle-horn just listens to music and plays it all by itself."

In spite of himself, Hot-Lips was growing interested. He followed Charlie Washington, and together they lifted the hood on the Ford. Underneath was the shining horn. It had four trumpets.

"This here horn used to play just one tune," Charlie Washington said dolefully. "Just the first few notes of Bugle Call Rag. Shore got tiresome."

"Go on," Hot-Lips said. "You ain't telling me it can play more than that now?"

Charlie Washington nodded.

"Been' playing right along with you all evening," he claimed seriously. "Can't quite decide which one of you is hottest."

That was a personal slam against the best trumpet man in Harlem. Hot-Lips backed away slowly, his fingers itching for competition.

"How long dis horn been playing like me?"

Charlie Washington looked thoughtful.

"First time was at the carnival," he said. "Ol' horn just ripped off some notes from the merry-go-round, then stopped. Tell you, I was some surprised."

"I should think," Hot-Lips agreed. "How 'bout a little jam session just so's I can make sure?"

Charlie Washington looked pleased.

"Sho' would be somethin'!" he agreed. "Now, I'd like to hear you two take off on the Two-O'Clock Jump!"

Hot-Lips Johnson was grinning. He polished his beloved trumpet on his sleeve, lifted it in the air and placed his lips to the mouth-piece.

"Give!" Charlie Washington begged.

Hot-Lips gave!

IN all Harlem there was no other playing like that. At his

lips, the trumpet became something fit for Gabriel to rave about.

When he ran up and down the scale, every curly-headed baby in the

district climbed out of its cradle and got ready to cut a

rug.

The first bell-like notes escaped Hot-Lips trumpet. Inside Casey's dance hall the band stopped playing. A hush fell over everyone. Johnson was doing a solitary jam session. Man, that was something to stop the world for!

But what was the other sound? There couldn't be anyone in Harlem who had the nerve to stand up to Hot-Lips?

As the crowd drifted to the doors and windows, staring out at the dusky figures in the parking lot two trumpets started to work together.

At first, the second one was a little fuzzy. Then it caught up with Hot-Lips and started to put in the licks that Johnson missed.

In five minutes the crowd at Casey's was swaying, punch-drunk. In ten minutes a first class contest was going on, and Hot-Lips was sweating to keep up. In a half hour the story was all over town.

Charlie Washington had bought a bugle-horn that could keep pace with the best rhythm-man in town.

From then on, the story grew like the immortal bean-stalk. Charlie Washington, worth two-bits and not a cent more, had become famous. Every boy in the neighborhood bought a horn and tried to work it out on the trumpet of Hot-Lips Johnson. That rhythm man fell in love with Charlie's car and offered him twice what it was worth just so he'd have the horn around when he felt a spell coming on.

IT never occurred to anyone that the horn might someday

outplay Hot-Lips himself. Johnson played his best, and he played

often. The horn seemed to listen and learn. Once in a while it

knocked off a tune or two when Johnson wasn't around.

Then Hot-Lips went to Albany for a week, to play with Jan Strutter's Hot Numbers, and Charlie's Ford got a contract at Casey's Dance Palace.

They say there was never anything funnier in Harlem than the sight of Charlie Washington's old Ford, its hood pushed up, squatting there in the brass section. They say that nothing Hot-Lips Johnson ever produced could equal the quality and tone that the bugle-horn turned out.

Harlem came and saw and paid homage. The cats were wild for more. Major Bowes made an offer and Charlie turned it down. He was happy at Casey's.

Then Hot-Lips came back from his week, ready to accept the cheers of the crowd he expected at the station. He wandered around to Casey's that night with an almost pale expression on his face. His pep was gone. His job was gone. Casey's Rhythm Cats didn't need him any more. He had been replaced by the machine age. Canned music, played by a bugle-horn, and contained in the rattling body of a decrepit Ford.

If Johnson had been a better man, he might have stuck it out. Instead, it drove him to cheap dance halls, and increased his yen for raw whiskey. He got a little short of cash and joined up with Spike Howard's gang of hoodlums.

Spike was plenty smart. He sent Johnson out on a couple of small safe-cracking jobs, just to get the feel of things. Then, one night, he sent for Johnson and met him behind the gambling room at Casey's Dance Palace.

Spike had been in every crooked deal he could find since his Mammy first tossed him into the street. He had a scar on his cheek from an old razor fight and he'd been collecting on that scar ever since.

"Look here, Johnson," Spike said, as soon as they could talk alone. "You been working fo' me about two months now. Ain't it time you caught up on yo' own homework?"

Johnson scowled.

"What you talking 'bout?"

Spike grinned and it made the scar glow as though it were bleeding.

"This Charlie Washington boy," Spike prompted. "You ain't gonna let him get away with what he done, is you?"

Hot-Lips scowled a little harder.

"Ain't nothin' I can do, is there?"

"Ain't no reason why you can't steal that four-wheeled juke-box?"

Johnson looked startled.

"Never thought of it like that."

Spike pushed a wad of greenbacks across the table.

"I can peddle that jumpin' jive-hound to a guy in Chicago," he said. "You can count one hundred bucks in the hunk of dough. You deliver that four-wheeled trumpet to the freight siding down near my place and the money is yo's!"

Johnson brightened.

"You can also get your ol' job back with Casey," Spike said, adding the clinching touch.

Johnson stood up slowly, and when he went out, the money was clenched tightly in his big hand.

IT might have worked, too. He might have succeeded in stealing

Charlie Washington's Ford if he had disconnected the horn before

he drove it out of Casey's Dance Palace.

But the horn objected.

Casey's was deserted at four o'clock. Hot-Lips Johnson managed to back the Ford out the rear door and get as far as the street.

What happened after that is history in Harlem.

The trumpet horns started to bleat the minute they reached the street. It was terrible.

First came the Bugle Call Rag.

"You can't get 'em up,

You can't get 'em up.

You can't get 'em up this morning."

High and shrill came the warning in Harlem's deserted streets.

Windows flew open and lights went on. Heads poked out the windows, and started a cry of protest.

Johnson, driving as fast as the car would go, felt sweat pop cut on his forehead.

The horn was silent for only an instant after finishing the last notes of the Rag. Then, evidently becoming playful, it imitated a police siren for five blocks and worked from that right into a heart-breaking rendition of It's Murder, He Says.

By this time, Johnson had gone completely wild. He cut across lots between a couple of apartment buildings.

As he emerged on the street again, holding fiercely to the wheel, the horns broke into the sad, mournful strains? of In the Hush of Evening. That was too much. Hot-Lips Johnson cleared the door and fell headlong into the street. By this time a crowd bad collected on the sidewalk. The Ford didn't stop rolling. It rounded the next corner and sped down between the lines of men and women who filled the sidewalks. There are those who will swear that as it neared the building excavation on the next corner, those trumpets were dolefully swinging out with My Last Goodbye.

It was a fact that the deep excavation was half filled with water. The Ford didn't hesitate, but plunged straight through the fence and tipped end over end into ten feet of muddy water.

A howl of sadness arose and swelled until it reached the outskirts of Harlem.

The last tune that Charlie Washington's bugle-horn ever played, was beating shrilly against the night as the Ford plunged toward the water.

"And so help me," Charlie Washington said afterward, with tears in his eyes, "that ol' Ford was tooting Taps just as it went under."

SOMEHOW, when it was all over, no one had the heart to punish

Hot-Lips Johnson. He hung around Casey's for a long time,

pleading with Charlie Washington for forgiveness. Perhaps Charlie

felt that he hadn't been entirely fair with Hot-Lips. Anyway,

after a few weeks, Hot-Lips was back in the band. His trumpet was

sweeter than ever, but he never played again within hearing

distance of a bugle-horn.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.