RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on the cover of Startling Stories, November 1939

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on the cover of Startling Stories, November 1939

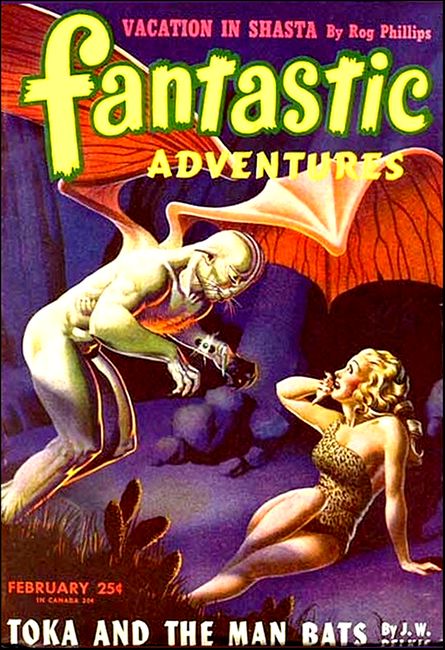

Fantastic Adventures, February 1946, with "Lark on the Ark"

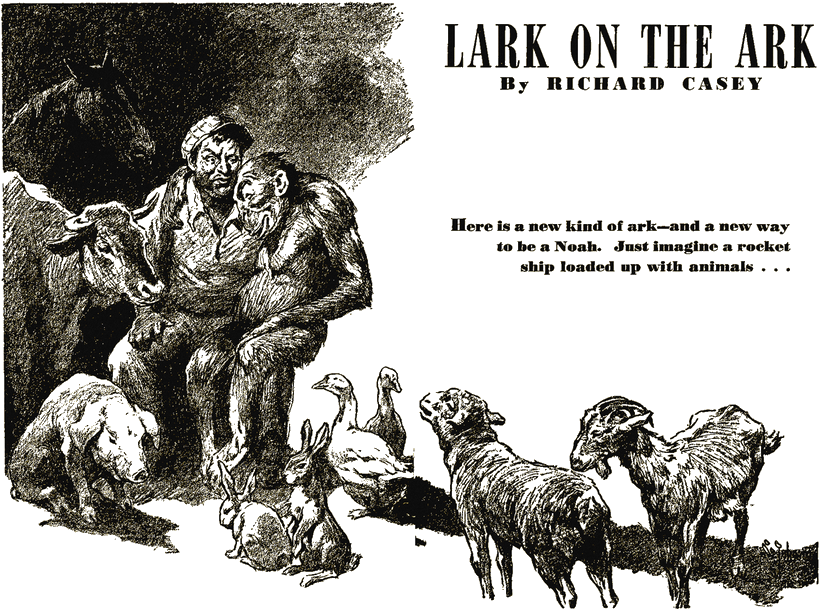

Animals, two-by-two, surrounded him.

Here is a new kind of ark—and a new way to be a Noah.

Just imagine a rocket-ship loaded up with animals...

PROFESSOR Lucius Lavender opened the door with great dignity and ushered the news-reporter inside. If Bill Barnes was startled by the upheaval in Lavender's home, he tried not to show it. Crackpots were funny. Your best bet was to get a story and move out before they started to affect you.

Barnes wondered if he should bow to this gaunt, mild-eyed creature, whose ears seemed about to flap, but never quite got to it. He compromised by offering a quick nod of his head.

"I'm Bill Barnes, reporter from the News. We'd like a story about that ark you are building." He didn't add that this was the fifth "end of the world" story he had covered this year.

"Certainly," Professor Lavender said in a grave-yard voice, "please come with me. I resent somewhat your idea that you might find an ark here. I plan to remove myself and my animals from this doomed world with the help of a rocket-ship."

Bill Barnes' eyes popped open alarmingly.

"A rocket?" He moaned, not knowing what else to say. "You've built a rocket?"

However, by this time Professor Lavender was off on a tour of the house.

The rooms they passed through on their trip to the rear of the house were bare of furniture. Several cages in each room held pairs of monkeys, rabbits and other small animals. The dining and living rooms were full of stalls in which there were horses and giraffes and other animals too numerous to mention.

"I'd like you to meet my assistant, Mr. Wilson," Lucius said.

A fat, dumpy individual came from the hall and approached Barnes. He would tip the scales at about three hundred, Barnes decided, and would roll in any direction very easily.

"Real name's Wilson," the man-mountain rumbled, "but call me Pudge."

"Please," Professor Lavender said in a discouraged voice. "No assistant of mine will be known by that name. Refer to him as Mr. Wilson, assistant to me on the expedition."

"Certainly," Barnes agreed, "anything you say. Now, if I can see that rocket-ship..."

LUCIUS led the way through the small porch into the back yard.

Barnes walked down the steps and stopped short at the edge of a

deep hole that had been dug where the lawn once grew.

At least something was going on here that indicated hard work. The hole was about thirty feet deep and lined with concrete. The high fence around the yard kept it hidden from curious eyes. The blunt, circular nose of a rocket-ship projected five feet above the rim of the hole.

Barnes turned to Professor Lucius Lavender, who was studying the rocket-ship with nothing less than reverence.

"You mean this thing is going to fly?"

"Certainly," Lucius answered enthusiastically, "isn't it nice? I copied the lines from a Buck Rogers space-ship."

Barnes gulped.

"You're going to take off in it?"

"Why not?" Professor Lavender stepped closer to him. "Papers will carry a forecast of fair and warmer for tomorrow. They're all crazy, you understand—crazy!"

Barnes backed away slowly, aware of the fire in Professor Lavender's eyes.

"Yes, I quite understand. You will be safe, of course?"

"Of course." The Professor's voice was rising steadily. "Tomorrow the rain will start. It will rain on and on for forty days and forty nights. My assistant and I will take off tomorrow morning for Venus. We will take our animals with us and start a new way of life on another planet."

"Quite an idea," Barnes agreed with little enthusiasm. He was secretly wondering how much powder it took to blow a rocket-ship into space.

"I suppose you have everything all figured out?"

"Everything," Lucius Lavender repeated in a hollow voice. "The power will be supplied by TNT. We have it at the bottom of the pit right now."

Barnes turned and without much dignity hurried back toward the house.

"I guess that's all," he said. "I hope you have a pleasant trip."

"We could use another member for the crew," Lucius said hopefully.

"No, I guess I'll stay here and drown with the rest of them," Barnes said. "I get dizzy in high places."

In the living room, Pudge Wilson was putting fresh hay under the cow.

"I suppose you are anxious to get started on the trip?"

Pudge nodded his head very slightly as though he had given the trip no serious thought.

"Guess so," he admitted. "They say on some of the planets, the air makes a man weigh only about fifteen pounds. Wouldn't that be something?" A gleam of hope came into his eyes.

Barnes took a last look at the great hulk of human flesh and agreed that it would.

Safe, in the street he glanced back over his shoulder at the fenced in back yard. He didn't slow down until he had covered three blocks.

Professor Lucius Lavender and his over-sized assistant were going somewhere all right, with that TNT under them.

Barnes didn't think it would be to another planet.

PROFESSOR Lucius Lavender had planned well, but at the last

minute Pudge Wilson ran into troubles that the partnership of

Lavender and Wilson had not anticipated. The pair of full grown

giraffes, purchased from the local zoo, were not designed to fit

the rocket-ship. That portion of the ship which was to house the

animals was separated from the Professor's control room by a

small hatchway. If the giraffes were in their proper quarters,

they could only stand upright by pushing their heads through the

hatchway to study the Professor gravely while he was at work. He

was forced to decide that the giraffes would not be necessary in

his new world. They were to be left behind. However, there was a

perfectly fine collection of other animals: horses, ducks, cows,

etc., that would fit the ship. Preparations were made to

take off.

It was noon and the rocket-ship was prepared for the flight. No one had shown the slightest interest in Lucius Lavender's enterprise. In fact, Bill Barnes had killed the story purposely so that no curious onlookers would lose their heads when the TNT exploded.

Professor Lavender managed to pull his assistant through the door of the ship with a more than normal amount of energy. With Pudge, came a copy of the evening newspaper. The weather report predicted fair and warmer for tomorrow.

"Just as I told you," Lucius said. "Poor souls, they know not that they face death in a few more days."

PROFESSOR Lavender climbed carefully into the control room and

called for Mr. Wilson to follow. He waited in vain for Pudge's

fat face to show through the hatchway. At last he walked across

the tiny room and stared down into the well of the ship at Mr.

Wilson and the animals. "Are you coming up here?"

Pudge Wilson looked very sad. "Professor, I guess you'll have to make this trip without my help. I came along to take care of the animals. You didn't figure on my size when you made that door to the control room. I could never get through that little hole even if I did trust the ladder that leads up to it."

And so it happened, when the rocket-ship took off, Pudge Wilson was condemned to spend the entire trip with his animals.

Professor Lucius Lavender wasn't quite so sure of himself when he finally sat down at the controls.

"Get hold of something down there," he shouted, "and hold on. There may be quite a disturbance when the TNT explodes."

Something in Pudge's voice indicated that he didn't realize the full importance of this moment.

"I'm holding on, Professor," he cried in a plaintive voice, "but I ain't entirely sure I ought to be going, now that I've had time to think it over."

Then came a terrific explosion of TNT and Pudge's animal quarters turned to a hurling, yelling hodge-podge of flying fur. In the control room, Professor Lucius Lavender felt a delicious sleepy sensation pass through his body, and suffered a complete blackout.

He would always remember his first sensation upon reawakening. The thing that surprised him most was that the ship was actually hurtling through space. When he shouted to Pudge Wilson giving him this stupendous bit of news, the fat man was singularly unimpressed.

"I had an idea we might be," Pudge called back dryly. "There's an ape down here that has been sitting on my lap ever since we took off. That force of gravity stuff is so strong that I don't think she can get off."

PROFESSOR Lucius Lavender's rocket-ship had been ducking about

in space for twenty-four hours. Thus far the professor wasn't

quite sure what course he should take. Lavender hadn't really

figured this far ahead. Neither had Pudge Wilson. Mr. Wilson,

isolated in the animal ward, felt very sorry about Mrs. Wilson, a

person he had forgotten about until now.

The animal ward didn't help a man's appetite. Pudge was feeling very low. He decided to chance another trip up the frail iron ladder to the control room. Professor Lavender was just deciding on a course when Pudge's head came through the hatch for the third time since morning.

"I wish you'd leave that hatch closed." Lavender turned with nose elevated slightly. "It smells terrible down there."

Pudge controlled his temper. He had heard about people forced to live together, and finally killing each other because of raw tempers.

"You're lucky, Professor," he said. "You don't have to live down there with them critters. Thank the Lord you didn't get the bright idea of including skunks in this new world you're settin' up."

Lavender didn't hear. He was busy staring at an object that had flashed on the vision screen.

"That's it!" His voice was triumphant. "I'm sure it is."

"Skunks is terrible," Pudge continued, "but apes is bad enough."

"It must be," Lavender's voice was shaking. His hands clutched the controls, holding the rocket on its course. "We're directly in line with it."

"Now, you take them horses—" Pudge went on hopefully.

Lavender swivelled around in his chair.

"You take the horses," he shouted. "For the tenth and last time, I'm warning you not to interfere with me. Get below and stay there."

"I ain't going." Pudge balked. "I'm gonna stay right here in this ladder where I can poke my head up for fresh air."

The rocket lurched suddenly into a space-pocket and Pudge plunged from his perch, landing on his back in the cow stall.

"If I thought you did that on purpose—" he shouted wrathfully.

Then, shaking his head doubtfully, he righted himself and went back to work. A little later he thought of his wife again, and remembered that he had meant to ask the Professor about that detail. He raised his voice so it carried up through the floor, to the control room.

"Hey! Professor, why didn't we bring our wives on this expedition?"

A moment's hesitation, and Lavender's voice drifted back.

"I've never had a wife."

Pudge nodded, content with the answer, then his cheeks reddened.

"Why, the inconsiderate bum," he sputtered. "I got a wife, ain't I?"

PROFESSOR Lavender had spotted Venus on the glass of the

vision-screen. The planet was still thousands of miles away, and

the Professor had neglected to install a speedometer in his

rocket. It might be days or weeks before they reached the green

planet, but at least he was aiming straight at it.

He had half-a-dozen more rockets to discharge before they were out of fuel. However, other problems had arisen.

His assistant was howling to the high heavens about the odor in the animal ward. Food was running short. The ward was much too small.

One of the apes had fallen in love with Pudge. The ape, a two-hundred-pound creature from Africa, insisted on making love to Pudge at every opportunity. Pudge didn't like it.

Pudge spent most of his day clinging to the uppermost rungs of the ladder, his head poked into the control room. The ape, moaning with admiration, hung below him, picking fleas and staring at Pudge with dreamy eyes.

Pudge looked as though he were sitting in a steam-bath. His head, protruding through the control room hatch, was as red as a boiled ham. The control room gradually became contaminated by Pudge's collection of wild-life.

Water, that terrible destroyer that the Professor had left earth to escape, would be appreciated now. The whole ship needed a good bath. If a garbage-scow had passed, both Pudge and the Professor would have exchanged posts with the scow-captain and appreciated the opportunity to do so.

THUS went the days on board Professor Lucius Lavender's

ark.

Venus drifted closer, becoming a large apple at which he aimed. The supplies were low and Pudge's morale dropped with them.

"We must suffer, escaping from the world, that we will appreciate the beauty of our new home," the Professor insisted.

"I wish the missus was along," Pudge insisted. "She can sure bake a mean pan of biscuits."

Professor Lavender became impatient.

"Perhaps I should have left you on earth, to suffer and die with the other sinners?"

"Maybe." Pudge wasn't sure. He went back to the discomforts of the animal-ward, preferring the company of a love-sick ape to further conversation with Professor Lavender.

On the seventh day, as nearly as the Professor could judge time, the rocket-ship sped downward at an increased rate of speed, directly toward the planet of Venus.

He called for his worthy assistant to come top-side. Pudge's head came through the hatch and glared at him balefully.

"That darned ape is getting serious. How long before we hit ground again?"

Professor Lavender was inclined to act lofty these last days of the expedition. His accomplishment was great and the power of it had gone to his head.

"Please don't trouble me with incidentals from the live-stock department," he begged. "We will land on Venus shortly. It will be your task to see that the animals are set free and provided with proper material on which they can graze."

Pudge's head bobbed with amazement.

"You mean to tell me we're really gonna land on another planet?"

Lavender expanded with importance.

"And what had you expected?"

Pudge was taken aback.

"Kinda guess I didn't expect much," he said sheepishly. "But I'd sort of like to get back home, what with this damned ape after me, and the animals all going nuts. What's Venus like?"

Lavender's eyes kindled.

"Venus," he said dreamily, "is the earth's sister-planet. My study of its surface indicates that it has the same attributes—"

"I mean, is it like home? I don't know nothing about them attribute things."

"Please," the Professor begged. "Venus will be a virgin country, much like earth but unsoiled by the footprints of man."

"What does that mean in English?" Pudge wanted to know.

"There won't be any one there but us, and the weather will be fine all the time," the Professor snapped.

"Thanks," Pudge said, and dropped below.

"SOMETIME during the night, we will land on Venus. I have the

shock-cushions ready. I can only hope that we do not hit too

hard."

These had been the Professor's last words before Pudge went below for the night. Pudge wasn't very much enthused about hitting anything. The end of the trip promised him some relief, and it was for this escape from the animals that Pudge lived.

He knew it must be close to the middle of that uncertain time called night. The animal ward was always dark. Putting in windows had been another one of the Professor's weak points. Pudge sat in the dark. Across from him the ape leaned sleepily against the wall, it's eyes on Pudge's nose. Every time Pudge wriggled his nose at a passing fly, the ape leaned forward eagerly, then sank back to wait again.

The poor ape couldn't understand why Pudge could look so much like her, and yet carefully avoid her advances.

WOOSH—W H A M!

Pudge felt his backbone curl up, then straighten out again. A howl went up in the darkness. The rocket hit something hard, seemed to bounce backward, and roll end for end a half-dozen times. Then the rocket was still and only the continued protests of the animals could be heard.

Pudge righted himself with great difficulty and managed to stand on both feet. He started to count his bruises, by feeling for them in the dark. There were too many sore spots. He gave up.

He started to feel his way about in the dark. His fingers touched the ape's broad nose, and he drew away in disgust. The ape sniffed loudly, lovingly, in the blackness near him.

The ship must be on its side. Pudge felt his way across the room to the ladder, followed it, clinging to its rungs whenever possible, and at last managed to open the hatch.

He leaned through it and stared at Professor Lavender. The Professor was lying on his back, staring out through a broken glass near the control-panel. Lavender rolled over as Pudge's head came into sight.

"Prepare to leave the ship and claim this place in the name of the United States," he commanded weakly.

"For a man who's come so far to get to Venus, you don't seem very glad about it, Professor."

Professor Lavender sighed.

"Have you looked out the window yet?" he asked.

Pudge grinned a little wickedly.

"Can't get into the control room," he said. "And you didn't exactly build my end of the ship for an observation post."

The Professor's face reddened.

"Then let me tell you that the scenery from here looks a great deal like a New Jersey countryside. There are a couple of farmers coming down the road, and they are followed by a half-dozen cows and a dog."

Pudge's groan released all the heartache that was inside him.

"And to think I nursed them damned hay-burners all this distance!"

THE FIRST farmer paused and stared at Professor Lavender's

rocket-ship as it lay on its side in the hay-field.

"It seems that another earthling has become dissatisfied and come to Venus for retreat."

The second farmed nodded.

"What a laugh we'll have when he pokes his head out and expects to find a Venus of the story-books. Harry, how in the dickens did those stories of three-armed men and six-headed women ever get started?"

Harry grinned.

"We got a good Chamber of Commerce," he said. "If the people on earth found out this was just another big subdivision, men would want to start another war right away. We got something here, mister, and we ain't gonna spoil it by letting the whole world in on the secret."

At this moment, Professor Lucius Lavender managed to unscrew the outer hatch of his rocket-ship, and climb out to face the two farmers on the road.

He, in his torn, poorly fitted clothing, presented a scarecrow appearance. The two farmers stared at each other. Pudge, having a slightly easier time of it, squeezed through the hatch and stood at the Professor's side.

The Professor waved at the two farmers.

"Ho, there," he shouted. "Have we made some mistake in our calculations? Isn't this Venus?"

The two men walked toward him.

"This is Venus, all right," the first one said. "You're about a hundred miles from the capital city." He chuckled. "Funny, but we named it Washington, just like on earth."

The Professor's face turned very red. His adam's-apple worked up and down quickly.

"But—I thought .."

The farmer named Harry laughed-heartily.

"You thought you were going to land on an uninhabited planet where there were lots of crazy looking people."

The professor gulped.

"But—Venus—inhabited?"

"And why not? We started a colony up here a hundred years ago. Nice layout. Just like on earth. Of course the weather—"

"Wait a minute." Pudge Wilson rounded the Professor's slight frame and faced the two farmers. "You mean to tell me you got animals up here just-like on earth?"

"Certainly," Harry answered. "That bunk about lizards and eight-legged apes is enough to make anyone sick. Sometimes I think the Chamber of Commerce over-does it."

His companion nodded.

"Sure does," he agreed.

PUDGE wasn't listening. He stared at Professor Lavender with

half-closed eyes. The Professor backed away a few feet.

"Apes," Pudge said in a low voice. "Horses, cows, rabbits that grow into dozens. No hay—no straw..."

"Be calm, Wilson," the Professor urged.

The farmer, Harry's friend, was still talking.

"Course, there's no women here." His eyes gleamed suddenly. "That is, of course, unless you fellows brought some along?"

The Professor looked doubtful, and Pudge pivoted suddenly to face the reception committee.

"Not-even-my-wife," he said in a doleful voice. "He was so interested in growing a new race of animals that he didn't even think about women."

Harry looked sad, then smiled again as though trying to forget how nice a wife might fit into the landscape.

"Oh, well, we handle the population angle by laboratory control at the capital," he said. "It works out pretty good."

"You've got all the animals you need?" the Professor asked hopefully.

"And more," Harry said. "Wouldn't give a dime a dozen for all the livestock on earth. We've developed a finer breed. If you got animals on that ship, you'd better not let them off. The livestock department at the capital will insist on examining them before they are slaughtered."

Professor Lucius Lavender stared at Pudge, and Pudge's eyes grew openly hostile.

"Well," the Professor said hopefully, "at least we've escaped a horrible death on earth."

For the first time since their arrival, the two farmers seemed greatly interested.

"Death—on earth? You can't mean that?" Harry cried.

Professor Lavender's eyes brightened and he looked for the first time as though he was really enjoying himself.

"Oh, yes," he cried. "Of course, there was no way for you, or the others, to know. I had the flood figured out mathematically. The great rain started the day we left. By now the world must be half flooded. It will be a matter of days before life on earth is destroyed."

The two farmers stared at each other, and both of them started to laugh. Pudge Wilson tightened his fists and refused to remove his eyes from Professor Lavender's peaked face.

"Go on, you two," Pudge invited grimly. "What's funny now? I'll bet it'll kill the Professor. If it don't, maybe I will."

Harry was laughing the harder.

"We get a daily report from our observatory," he said. "Our telescopes are so powerful that they see all the news that is fit to print about earth. I've been reading the papers for years, and there has been no recent mention of a flood."

"No," his companion added. "And here's the funniest thing about floods. We get one hour of sunshine in the morning. After that, it rains for twenty-three hours every day here on Venus."

Professor Lucius Lavender made a desperate but unsuccessful attempt to escape Pudge Wilson's fist. He went down on one knee.

"That first sock is for taking me away from home," Pudge howled, and let loose again. This time he connected solidly, and Professor Lavender stretched out at full length, staring up pleasantly at non-existent stars.

"And this is for locking me up with that damned ape."

Professor Lavender couldn't move. He felt pleasantly paralyzed. Little stars zipped around inside his skull and he heard angels singing.

It started to rain, and the water poured down on his upturned face in an avalanche.

Pudge leaned over him, and with great pleasure in his voice, whispered:

"So you wanted to escape the flood, did you? Remember, Professor, I can have that ape shot. You can't escape the rain. Twenty-three hours every day, Professor, remember!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.