RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Fantastic Adventures, December 1943, with "Pearl-Handled Poison"

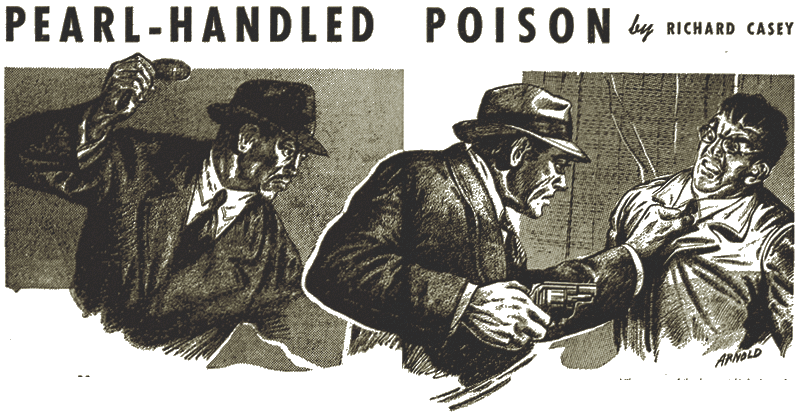

Mike, unaware of the danger at his back, caught

the man's coat lapels between savage fingers.

Mike was in a tight spot. He needed a gun—quick! And a dead hand gave him one!

IN the first place, you gotta understand that there's something inside Americans that make 'em different than the little yellow Japs. Some people call it conscience. In Mike Humphry's case, I didn't think the guy even had one. Anyhow, he never showed it.

Before the war, Mike took cash from wherever it came. He organized the laundry drivers of Seattle, collected two grand a week and headed for bigger things. Mike weighed two-fifty in his stockings and without benefit of shoulder pads. He moved like a cat and struck like an eagle. He never smiled and he never left the tough jobs for his boys.

Then Pearl Harbor came along, and Mike's kid brother joined the Air Force and went to the South Pacific.

Mike didn't let the war cramp his style. He had Seattle organized tighter than a full sardine can. He collected enough cash to float the war debt and he carried a snub-nosed automatic everywhere he went just to enforce his point of view.

His kid brother sent a few letters, and every time Mike read one of them, he'd draw a couple of thousand from the bank and go for a walk. I caught him two or three times coming out of the U.S.O. center. He'd just pass it off with a foolish grin. Once he went down and gave the Red Cross a pint of his blood.

"If you tell the boys, Johnny," he barked at me, "I'll fill you so full of lead that you'll sink like a Jap submarine."

That was Mike Humphry, tougher than nails and soft in his heart for that kid in the Air Force.

About that time, Mike started doing business with Mr. Smith. Mike and me never saw Mr. Smith. One of Mr. Smith's boys came around to the club. He was a dried up little shrimp who dodged his own shadow and looked scared every time he sidled up to Mike.

Anyhow, Mr. Smith had dough—plenty of it. He sent word that he was a South American representative and he couldn't get enough steel and war material from the regular sources. He wanted to get some off the black market. Mike took care of that. They were preaching all over the west coast that our little brown brothers down south were great guys.

"Help 'em," they said, "and make 'em our pals after the war."

Mike helped 'em. We picked up all the steel and powder we could find in Seattle and a ship-load of it cast off after dark one night. The ship had the name BRAZIL painted all over the front of it. That sounded good to Mike and me, and we went to the club with a nice little wad of green-backs to put away. The next day Mike sent half the cash to the Red Cross and told me he'd push me off the Bay Bridge if I told anyone.

It went on like that for a long time. Mr. Smith never showed up himself, but the little guy who represented him came every week. There were a couple more ship-loads of stuff and a lot more cash to distribute.

Mike sent a handy gadget to his brother. He picked out a little pearl-handled revolver, got permission from the authorities and sent it in case the kid got in a tight spot. That gun was a pretty little thing. It had mother-of-pearl all up and down the grip and the barrel was of the smoothest, hardest steel I'd ever seen. It felt good and sort of comforting just to hold it.

Then Mike got word that his kid brother had been shot down over the Bismark Sea, and would he please accept the medal that the kid had earned the last time he took a dive.

Mike took that pretty hard. For a week he wouldn't even see Mr. Smith's representative.

"Johnny," he said. "What the hell am I living for? They won't take me in the Army. All I can do is give cash."

I grinned.

"Sort of a Robin Hood," I said. "Robbing the ginks with dough and paying off to Uncle Sam. You're doing okay, Mike."

"You ain't told anyone I'm going soft?" His eyes were almost pleading. I never saw Mike like that before.

"No one," I said. "In fact, I been giving blood myself. Got too damned much, anyhow."

THEN his brother's letter came. It was written before the

kid crashed, but the mail got screwed up and it reached Seattle a

week after the boy died. I never saw the letter, but Mike got

hard and cold when he read it. He tore the letter up in little

pieces and his lips were working mighty queer when he looked up

at me.

"Mr. Smith's man been in lately?" he asked.

I told him yes. The guy was driving me crazy, trying to get to see Mike.

"Good," he said. "This time I'd like to meet Mr. Smith himself. Kinda funny he hasn't been around himself."

I didn't think so. A good many of the boys didn't like to face Mike personally, but I couldn't tell him that.

"The next time he comes in, Johnny, put a tail on him. I'd like to see where Mr. Smith hangs his hat."

The shrimp came in a little later that same day. Mike was with him for a half hour and promised some more stuff. Then the shrimp came out and I tailed him half way across town. He was slippery but I switched another man on his trail and found out he went into a little restaurant down on First Street.

"Good," Mike said when I told him. He took his automatic out and had a look into the chambers. "We'll go down and see Smith personally."

How did he know Smith was a Jap? Just figured it out, I guess. Mike wasn't so smart. He only went through grade school. Just the same, it didn't take a master-mind to connect Smith with the kid's last letter.

"The kid said he was going out with a couple of bombers to spot a Jap supply ship masquerading as the BRAZIL!"

Mike told me that on the way down town, and he said it in a voice that made my spine shrivel up and ice water start to percolate in my veins.

There wasn't anything we could do about the BRAZIL, or nothing I could say to make him feel better, so I shut up.

Mike don't like company on that kind of a job. I stayed in the front of the restaurant and he went back and pushed the curtains open that led into the back room. I pulled out my rod and laid it on the table. Lighting a cigarette, I watched the front door. The girl at the cash register kept an eye on me, but she didn't dare to move. There wasn't anyone else in the joint.

I heard Mike's voice, smooth as glass, talking to someone behind the curtain.

Then Mr. Smith, I guess it was, started to protest in a high- pitched, frightened voice. They kept talking like that for a while, Mike's voice low and almost gentle. Mr. Smith was getting excited.

Then there was a shot, a shrill, pig-like squeal of pain, and another shot.

I DIDN'T waste much time getting to that curtain. Before I could

push it aside, Mike heaved through it and stood there, his mouth

open, eyes wide. His arms were hanging limply at his sides and

his coat was torn from his shoulder as though something heavy had

ripped it open.

"What the hell," I snorted. "I thought he got you."

Mike didn't say a thing. He just stood there staring at the girl by the cash register.

I pushed by him into the back room.

There were two Mr. Smiths. Anyhow, there were two Japs stretched out on the floor, and both of them had slugs in their bellies. I kneeled down and saw that one of them was holding a lead-filled, wicked-looking blackjack. He must have come up behind Mike.

He was lying on his face near the other Jap who had crumpled up in the corner. Mike had been facing Mr. Smith the first, and his shot had carried straight through his heart.

Then I saw the gun. At first I couldn't believe it, but there wasn't another like it in the States. It was near the wall, tossed against the baseboard with the grip leaning upward. I picked it up, and turned it over in my hand. The barrel smelled clean and there wasn't a trace of powder inside it. I opened, the chamber but it wasn't loaded. I guess my hand started to shake a little, and I was wondering if maybe I hadn't given too much blood that last trip to the Red Cross.

It was the same rod Mike had sent to his kid brother. The pearl handle glistened in the lamplight, and I saw a little groove had been filed carefully into the base of the grip.

Mr. Smith and his partner had been fighting something they didn't reckon with. I wiped my prints off the rod and put it back against the wall carefully. The coppers would have a lot of figuring to do if they found a solution. The kid that owned that rod was at the bottom of the Pacific, about six thousand miles away. I don't think they worried very much. There's too damned many Japs anyhow.