RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting of a galiot in a storm,

attributed to John Sell Cotman (1782-1842)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting of a galiot in a storm,

attributed to John Sell Cotman (1782-1842)

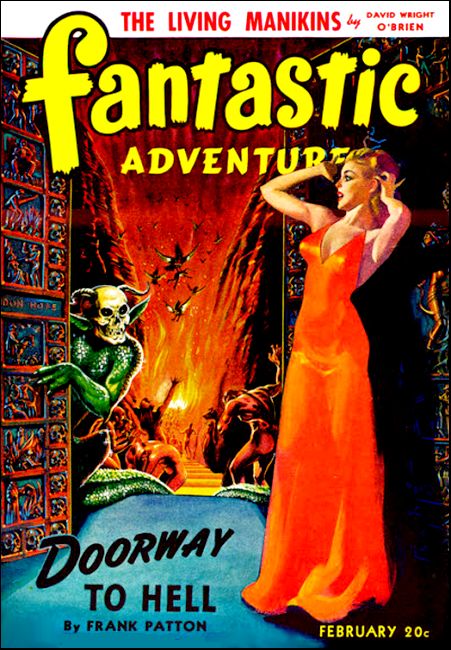

Fantastic Adventures, February 1942,

with "The Appointment With the Past"

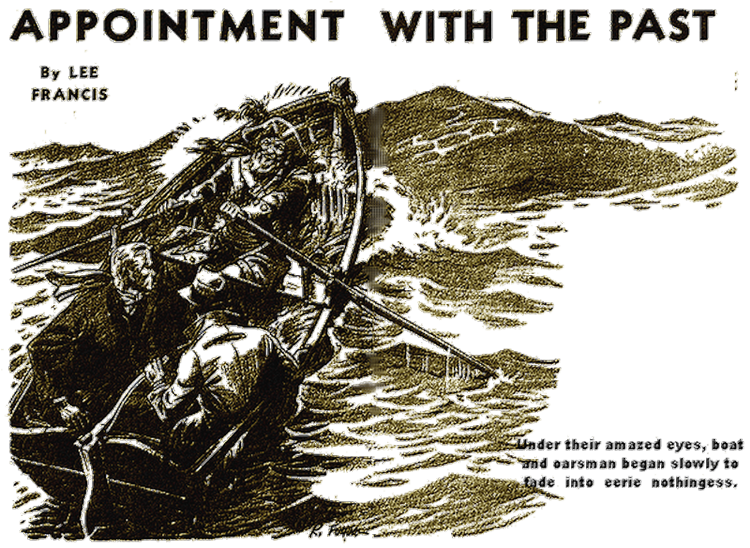

From the sixteenth century came a fantastic ghost galiot, seek-

ing two men from today who could rectify an ancient wrong...

CAPTAIN JOHN WEDGE of the Red Widow watched the Dutch galiot heave to. In spite of the badly tattered sails and the weathered condition of the vessel, Wedge recognized Captain Vanderdecken's ship at once.

Wedge swung down the ladder gracefully and dropped into the long-boat. Ruff Slants, the mate, leaned far over the rail.

"Put a shot into her mainmast if she tries to show her heels," Wedge shouted.

The mate grinned broadly. His small eyes were glistening.

"Aye, sir!" His voice rumbled like far-off thunder. "We'll teach them a thing or two. Don't you worry, Captain."

Wedge settled his splendidly attired figure in the prow of the long-boat and pulled the plumed hat down close to his eyes.

"Pull away," he ordered. "We've a score to even with Captain Hans Vanderdecken."

The long-boat swept away from the Free Rover's ship and sped swiftly across the green swells of the Atlantic. Captain Wedge was right enough about the weather-tossed ship that had come around and stood by off some five hundred yards. The Oriental, a three-masted Dutchman with tattered, dirty sails, had seen hard days since Wedge had watched her slip under the mighty guns of the Sovereign of the Seas and clear the English coast for Tunis.

Captain Hans Vanderdecken was a quiet, honorable man. As a Dutchman, he loved his country and went to many ends to preserve his own reputation. He stood now at the rail of the Oriental waiting for the slim, polished long-boat as it knifed the waves toward him. He knew that Captain Wedge and his splendid fighter, the Red Widow, were on an unpleasant mission.

Hans Vanderdecken was no fighter; yet he was not the one to run from a battle. The Red Widow carried thirty-two heavy cannon. His own craft had but sixteen on her gun deck and his men had little spirit left for fighting.

The Dutchman held his ground, his velvet clothing faded and spotted by sun and salt water. His face was unkempt and covered by a rough beard. Behind him, a sullen crew presented no better appearance. They had known what was coming and waited stolidly, unafraid of the death that they had faced so often.

The long-boat scraped the side of the ship. Captain Vanderdecken met John Wedge at the rail, offering his arm to assist the Free Rover aboard.

Wedge, his handsome face stormy with anger, vaulted over the rail alone, ignoring Vanderdecken's gesture of friendship.

"Captain Hans Vanderdecken." Wedge's voice was sharp. "It seems you couldn't escape us, for all your blundering about the sea."

Vanderdecken's face expressed sadness and bewilderment at once.

"But, Captain Wedge," he protested. "I've been searching for you these many weeks. I had no wish to escape the Red Widow."

Wedge's fists clenched tightly. He strode a few steps up the deck, turned and faced the Dutchman, trying to control his temper.

THREE of the seamen from the Red Widow had left the

long-boat and were at the rail, waiting for their captain's

orders. Wedge faced the captain of the Oriental with head

thrown back, long black hair blowing in the wind. In silken cape,

knee-breeches and square-toed, buckle-topped shoes, he was an

arrogant, splendid figure of a man. In contrast with his finery,

Vanderdecken seemed a member of his own crew. Wedge stared into

the Dutchman's sunken blue eyes.

"Captain," he said calmly. "You were once an honest man. I trusted you on a mission that meant life to sixty of my closest friends. You carried so vast a fortune that it turned your head. You failed on that mission, and now I'm going to punish you as I would singe the mangy beard of a Spanish don."

"First, you will hear my story?" Vanderdecken's voice was low, harsh with emotion.

Wedge reached into the pocket of his breeches and drew out a small sheet of rolled parchment. He thrust it toward Vanderdecken.

"This message came overland by stage from Tunis," he said testily. "Johnathan Fisher's son escaped from the Dey. Read it and profit by the knowledge of what you have done."

The Dutchman took the scroll hesitantly. It was dated, Tunis, the thirtieth day of the third month, 1648.

To My Dear Friend and Loyal Partner, Captain John Wedge:

This message is sent at a poor time. The ship to which you entrusted the silver has not arrived. The Dey is deeply angered and will not wait longer. We shall, all sixty of us, including the women, die at the hands o the Dey before this reaches you.

I pray to God that my son will escape and reach you with this message. I know not who took to sea with the silver and failed to arrive in time to appease the Dey's wrath. I can only say that whoever he may be, may his ship sail the seven seas without peace for the remainder of time, and may he never rest so long as the trade winds blow.

Your Ob't Servant, Johnathan Fisher.

Vanderdecken's eyes swept up to catch the fanatical fury on Wedge's face.

"This is a great injustice," the Dutchman protested in a broken voice. "We arrived outside Tunis only a day late. There was no point in leaving the silver, with the terrible deed already done. I tried to return hastily and report my failure to you."

Wedge waved his arm angrily.

"No explanation is necessary, Captain," he snarled. "You were sent to save the lives of those unfortunate people. Nothing can justify; your failure to do so."

Dutchman and Free Rover stared at each other. Vanderdecken's expression was that of a man who faces an unjustified death. There was no pity in Wedge's eyes. His anger was a deep, tangible thing that could not be quenched by explanations.

"Believe me, sir," Vanderdecken said haltingly. "Above all, I am a man of honor. There was mutiny, and worse, aboard my ship. I was unable . . ."

"Enough," Wedge thundered. "You shall find no forgiveness in my heart. You say the silver is still in your hold?"

Vanderdecken nodded hopelessly.

"Every bar," he said. "I planned to return it to you."

Wedge turned toward his own men.

"Lock this blubbering fool in his cabin," he shouted. "Signal the mate to pull alongside and set the grappling irons. Prepare to remove the cargo to the Red Widow."

TOURING the half day it took to handle the silver,

Vanderdecken remained locked in his cabin. Wedge, in turn, did

not leave his spacious quarters below deck on his own ship.

Slants brought him news that the silver was in the hold and the

Oriental empty of wealth. Then Wedge went on deck.

In a manner, he pitied Vanderdecken. The Oriental had once been a fine ship. Now, her hull covered with barnacles from many months at sea, and scoured clean of paint by the storms she had faced, Vanderdecken's craft was a sorry object. Vanderdecken was released from his cabin at Wedge's orders. Wedge waited until the Dutchman came abreast of him on the other deck.

"Order your crew to cast off," Wedge shouted. "Put on a full head of canvas and stand away."

Vanderdecken could not answer. Five minutes later the ships had scraped slowly apart. Men went swiftly into the shrouds of the Oriental. They moved mechanically, expecting death yet asking no quarter.

The wind stirred the square-rigged canvas of the main mast and the Dutch galiot moved away. She cut the water lazily, as though she no longer had a goal. The Red Widow remained motionless. Below, on the gun deck, the master gunner had ordered powder broken out and sixteen guns were primed, with fuses ready. The Oriental was under a full spread of canvas now and moving swiftly southward. Captain John Wedge watched her coolly, calculating a fair distance for the first shot. He turned to the waiting Master gunner.

"Give her a ball across the bow," he said sharply. "When she comes about, let her have a broadside that will send her to Davey Jones."

The first gun roared and smoke belched from its ugly barrel. The foremast of the Oriental took the blow squarely and crumpled into the sea. The Dutch ship swung around slowly, as though bewildered by the attack.

"Now!" Wedge shouted.

The Red Widow groaned in protest under the force of the sixteen-gun broadside. A cheer went up from the quarter deck and the Oriental bucked suddenly and leaned over like a wounded thing. Fire broke out below her decks and licked upward into the sails. Canvas billowed down like a dirty shroud over a casket. The Oriental was little more than that. Her nose dived down sharply. Long, hissing streamers of smoke floated into the sky as water came up eagerly and licked over the foundering ship.

Wedge watched the last bit of timber as it caught in the whirlpool and was sucked down behind the stricken vessel. Then he turned to the mate.

"So much for our fine Captain Vanderdecken," he said. "May his death avenge the murder of my men."

Slants shook his head slowly.

There was a puzzled, frightened look on the mate's ugly face.

"I'm wondering about that curse, Cap'n Wedge," he said. "Curses ain't put down to be forgotten. They don't rest easy until they have been filled."

John Wedge chuckled.

"Hans Vanderdecken has filled his part of the bargain," he said. "I made sure the Oriental won't sail after this day. She's spiked down snugly in Davey Jones' locker."

FOG settled over New York Harbor, blotting out the Statue of Liberty and Staten Island. A dense blanket of white hung close to the water. The Jersey Ferry plowed uncertainly ahead as though seeking her mooring through memory of many past trips. In the wheel house a portly, blue-uniformed captain kept his ears and eyes alert to the changing sounds near him.

Fog horns ripped the silence in every direction. A sullen-faced young man and a slicker-clad girl leaned over the lower rail, watching the barely visible water as it drifted below them. Robert Fisher, of medium height and handsome in a sullen, tired way, waited for the girl to make some explanation. At last she looked up, staring at him with brown, tear-filled eyes.

"Then it's to be that way?" she asked in a low voice.

Fisher turned suddenly, pushing her against the rail, his hands closing tightly over her wrists.

"You're damned right," he said harshly. "You've been running around with the heel and you don't deny it. The News job keeps me busy but I still manage to get around a lot nights."

She struggled silently, trying to release his grip on her arms.

"Please, Bob, you're hurting me."

"And I'll hurt you worse," Bob Fisher said. "I'm not playing second fiddle to Adams. You're a two-timing . . ."

Arlene Williams managed to release one hand. She brought it across his cheek with all her strength.

"You're the most stubborn, unreasonable man I've ever seen. I've had dinner with Mr. Adams a few times. We work at the same office. I don't like being alone, and I can't see that any harm is done . . ."

She bit her lip and blood showed against the smooth whiteness of her teeth.

"I told you to stay away from him," Fisher almost shouted. "Now, by God, it's all over between us. I'll take the ring and we'll call it quits."

Arlene Williams stamped her small foot against the deck.

"Ralph Adams is a much finer person than you will ever be."

"Shut up!"

The girl drew the engagement ring from her finger. Her lips quivered angrily. Fire flashed from the brown eyes.

"Don't ever speak to me again," she said. "Take your ring and—and toss it into the water if you want to."

Her sharp heels clicked firmly against the deck. Fisher had one glimpse of smooth, silken legs as she rounded the deck house. Then he was alone.

The ferry ploughed slowly ahead. Fisher leaned over the rail staring moodily into the oily waters. With a gesture of resignation he tossed the ring into the water and watched the flash of the small stone as it sank.

Below deck, bells started ringing loudly. Fisher glanced toward the wheel house, a puzzled frown on his face. The ferry wouldn't land for several minutes yet, He heard the captain shout hoarsely from the top-deck.

"Ahoy there, come about, or you'll run us down!"

THE stout officer was leaning over the rail above Fisher's

head, a megaphone held tightly to his lips. Fisher tried to see

through the fog ahead but the wet vapor curtain hid everything.

The engines stopped abruptly and the ferry floated slowly ahead.

He could hear the passengers gathering behind him, the excited

whispers near his elbow. Then a strange, weather-beaten ship

struck the side of the ferry and scraped slowly along the rail.

Long grappling hooks flew from above, caught on the rail and drew

the two vessels tightly together.

The ship—from what he could make out through the mist—was like nothing Robert Fisher had ever seen. It towered above them, the brightly colored sails partly hidden in the fog. From its masts, like something from \ pirate book, canvas flapped idly in the slowly rising breeze.

The captain of the ferry was cursing loudly. Then a man leaned over the rail of the sailing vessel. He was dressed in an oddly pointed hat with a red plume. His coat, fashioned from blue velvet, had lace cuffs and a white lace collar about the neck. The stranger's face, that of a man of about fifty, held a strange, sad quality that puzzled Robert Fisher.

The man's eyes studied the deck of the ferry and suddenly met Fisher's gaze. He turned and spoke to someone out of sight behind him in a strange tongue that Fisher could not understand.

Robert Fisher felt his knees go suddenly weak. He wanted to turn and run, yet stood waiting, as though hypnotized by what was taking place.

The ferry captain was still sputtering. Commuters moved away quickly and took refuge in the main cabin.

"Get that blasted carnival ship out of the way!" the captain howled. "You've got harbor traffic tied up."

The man on the ship ignored him. It was as though only one man were visible to his eyes.

"You're name is Fisher—Robert Fisher?" he called.

Fisher nodded slightly, and then wished he hadn't.

"Good! Prepare to come aboard."

"Come aboard?" Fisher gulped. Suddenly there was a deep, terrible fear within him.

He saw the two seamen as they swung over the rail and clambered down to him. Their dress was simple, crude. Bright bandanas were wrapped tightly around their heads. They carried long, glittering cutlasses.

"I—I don't understand." Fisher, still wanting to run, reached up and grasped the wet ladder dangling from the mystery ship's rail above him.

"There is no time for explanations," the man on the ship said. "You are to come aboard at once."

The seamen were at his side now, ready to carry out their orders.

Fisher had a strange feeling that he was suddenly living a dream. He started to climb up the rungs of the rope ladder. Once he had gained the railing, he looked back and saw Arlene Williams running along the deck of the ferry toward him. There was fright in her eyes.

"Bob!" she shouted. "Bob, come back!"

Already her voice sounded far away, as in another world. He had no control of his own emotions. The whole thing was like a shock to his body, leaving him with no will to act as his own master.

"Please, Bob!" Arlene's voice rose to a scream of terror. "Get off that ship!"

HE WAS standing at the rail. Beside him, the strangely dressed

captain of the old vessel stood watching him intently. Seamen

were rushing about the deck. The whistles and sounds of the

harbor were growing faint. When he looked again the ferry had

disappeared. Only the faint, rippling blackness of water was

below. He looked up at straight masts and slowly filling sails.

Wind was sending the fog up in snake-like wisps and the whole

length of the polished deck was visible. Then the strange sails

filled and billowed out. They snapped and creaked in the wind.

The fresh air blowing in Fisher's face brought his senses back to

him.

He turned to the strange captain.

Before he could open his lips to protest the man spoke to him.

"I know the Oriental seems a strange ship to you. We have a long voyage to make. However I give you my promise that I am your friend. You shall have an explanation-after you have rested awhile."

Rested? Fisher thought he would rest like a caged animal, brought here almost against his will and trapped as surely as though ten feet of concrete separated him from the things he knew.

Why he had come he couldn't guess, unless, in his own anger toward Arlene, he thought that any escape from the old routine would offer him relief.

THE building was on the New Orleans waterfront. The night was foggy and dark. A single light burned on the second floor, sending a pale yellow gleam across the dark water below the pier. The door to the lighted room was stenciled Laird and Wedge—Marine Insurance.

The title was misleading. Jim Wedge was no longer a partner. He and Laird had broken their partnership a little over an hour before. It was a bitter parting, filled with accusations and anger.

Laird, a stout, bald-headed man of forty had started James Wedge in business five years ago. Wedge had plenty of ability, but he also had a bad temper. It flared often, and usually beyond his control.

Laird sat stiffly behind the desk as Wedge, mouthing a steady tirade of abuse, paced the floor.

"And I say I borrowed the cash honestly and will leave the full sum, plus interest, at the bank on Monday," Laird said quietly.

Jim Wedge, tall and brown-skinned, whirled about, his blue eyes boring angrily into Laird's. He pounded on the desk top with his fist.

"We were partners," he shouted. "You had no right to take that money without consulting me first."

"I told you before," Laird answered quietly, "that since you didn't plan to come home until tonight, I knew of no way to consult you first. I had the chance to make an investment that will net plenty, The money is safe. I have a receipt for it from one of the city's biggest brokers."

"That's not the point," Wedge persisted. "We agreed to handle the company funds together. It's the principle of the thing. I say that in taking the money without my knowledge, you committed a breach of trust."

"You're a hot-headed young fool!" Laird stood up, leaning on the desk.

His breath was beginning to come hard. "Rules are fine, but when you've lived a few years longer, you'll find they occasionally have to be changed to fit the case."

"Damn you, Laird!" Wedge's face turned brick-red. "You're a smooth one. How do I know you'll return the money?"

Laird's fists tightened but his voice remained under control.

"I've taken enough of your talk," he said. "That finishes it. You and I are washed up—finished. I'll have the full amount of the check sent to your bank on Monday. From now on the partnership is dissolved."

"And good riddance," Wedge said testily.

He snatched his hat from the desk, wheeled about and slammed the door behind him as he went into the hall. He walked swiftly downstairs and out into the darkness. He groped his way across the planking of the wharf toward the gate to the street. Blinded by the fog and his own anger he couldn't find the gate in the blackness. He wandered about slowly, trying to locate the fence. He was afraid to get too close to the edge of the wharf. No one would be around to lend a hand if he fell into the bay.

He hesitated, trying to get his bearings by sound. The faint splashing of water came from below him. A fog horn was roaring in the distance. There was a boat somewhere near. He could hear the water lapping against its sides and the scraping of oars as they rubbed in invisible oarlocks.

A voice spoke to him from the water.

"You're name is Wedge?"

He whirled around, cold sweat on his forehead.

"Who are you?" he demanded hoarsely.

"The ship is waiting for you in the harbor," the voice said.

WEDGE waited silently. The sound of the oars was stilled.

He wondered if Laird had promoted some wild scheme to be rid of

him. Then, hearing footsteps near him in the fog, he turned and

started to run. His shoe caught between the planks and he went

down heavily.

"No one will harm you." The same voice, low and cultured, was close to him. "You are needed to make my voyage successful."

He struggled to his feet. A rough hand was on his shoulder and he lashed out with his fist, trying to find the body behind it. Something hit him on the head and he slumped down, white-hot pain in his head.

Wedge was sure that he didn't entirely lose consciousness, yet when he was again in possession of his senses, he was in a small boat. Wedge lifted himself carefully from the planks. He stared uncertainly at the man opposite him.

"I'm sorry my men had to treat you roughly," the stranger said. "But I could not risk losing you. I have searched for a long time."

"If Dave Laird is in on this," Wedge said angrily, "I'll see him in hell for his trouble."

He couldn't make sense of his surroundings. The man near him was dressed in Seventeenth Century Dutch clothing. He looked like something from the Mardi Gras with plumed hat, velvet coat and breeches worn above white silk stockings. His shoes were square-toed and topped with silver buckles.

"I know not of a Dave Laird," he said. "Allow me to introduce myself. I am Captain Hans Vanderdecken of the good ship Oriental."

"Cut the comic opera," Wedge said.

The boat was cutting the water swiftly, two men at the oars. Wedge waited for some chance to escape. The boat slowed and drifted now. A voice called out from above them. It was in a foreign tongue that Wedge could not understand.

"Aye," the Dutchman answered. "We've found our man."

Wedge strained his eyes toward the rough planked sides of the vessel. Above his head was a row of cannon, different from any he had ever seen, jutting from the side of the craft. He heard sails snapping gently in the fog and the steady creak of masts as they leaned to the breeze.

Suddenly Wedge sprang to his feet and jumped into the water. Before he could take more than a few swimming strokes, however, he felt a crushing blow on his head. These beggars were handy with a belaying pin. The water started to creep over his face and a strong arm went around his neck. After that he choked from the water he had swallowed and heard far away voices, as though in a dream. Try as he might, Jim Wedge could fight no more. Abruptly, his senses left him.

ROBERT FISHER awakened from a troubled sleep. He climbed wearily from the rude bunk, realizing that for the first time in many hours the Oriental was in quiet waters. Fisher was no sailor. The nightly trip on the Jersey Ferry was his one contact with boats. Just how long he had been on the Oriental, he couldn't guess. They had locked him in a tiny cabin below deck where he had awakened only long enough to be sick, sinking into a deep slumber when his stomach calmed. His sole companion, a small black kitten, was poor company.

He knew little of Captain Vanderdecken and still less of the crew. There had been no explanation given and Fisher was much too sick to care what had happened since he left the ferry.

Now that the ship no longer swayed and groaned in the wind, he felt better. There were voices outside the hull of vessel. At first he hoped a rescue party was boarding the Oriental. Then footsteps sounded on the deck above.

He had not attempted to leave the cabin before. To his surprise, the door was unlocked. He stepped outside, staggered and clutched the wall to keep from falling. The black kitten rubbed on his shoes and purred contentedly. Fisher walked slowly along the dark passage outside the cabin, saw light sifting down the stairs ahead of him and went toward it. Footsteps were descending the steps. He moved swiftly into the shadows below the stairs and waited. Two seamen came down, carrying the limp, water-soaked figure of a tall young man. They passed Fisher's hiding place, entered a cabin across the passage-way and came out without their captive. He waited, holding his breath as they came near him and went back up to the deck.

Fisher walked hesitantly toward the cabin. He pushed the door open quickly and stepped inside. The man jumped from his bunk, fists clenched, and staggered toward him.

"Who the hell are you?"

Fisher grinned.

"A friend in need," he said sourly. "We both seem to be in—or on—the same boat. My name is Robert Fisher."

James Wedge relaxed.

"My name's Wedge," he said slowly. "Jim Wedge. Did they kidnap you?"

Fisher nodded.

"Took me from New York Harbor in a fog," he said. "It's all so damned puzzling."

Wedge sat down and started to remove his water-soaked clothing.

"For me, too," he said. "Did you say you were from New York?"

"Right," Fisher answered. "Worked for the News. I was on the ferry headed for Jersey, when this boat picked me up."

Wedge looked up, puzzled.

"I can't make it out," he admitted. "Here we are in New Orleans. Why in hell did they come all the way down the coast and into the gulf just to find me. We must have been chosen pretty carefully for whatever use they intend to put us to."

Fisher stood quietly as Wedge removed his outer clothing and placed it over the edge of the bunk where it would dry.

"You're sure this is New Orleans?" he asked.

Wedge scowled.

"I was in my office half an hour ago," he said. "I ought to know."

Fisher's eyes wandered about the cabin.

"I guess I've been on board two or three days," he said, in offering an explanation. "I've been sick most of the time. The only man who seems to be able to talk English is the captain. He won't tell me why I am here or what's in store for me. He did say that he was my friend and that I need not fear him."

Wedge chuckled.

"I left behind an incident in my life that wasn't very pleasant," he said. "I'm not so sure that I'm sorry for all this, now that I've had some time to think it over."

Fisher seemed a little startled at Jim Wedge's confession. He remembered his own quarrel with Arlene. When he thought of it that way, there wasn't much left for him in New York.

WEDGE was busy over a small sea-chest in the corner.

"It seems we have clothing," he said. "That is, if we're not fussy."

He pulled out a pair of blue trousers, a striped red-and-white shirt and started to put them on. Half-way through the task, he hesitated, bent over and drew a small paper ticket from the chest. He studied it, then passed the slip to Fisher.

"Can you make anything of this?"

Fisher studied the slip.

"Written in Dutch," he said. "I know that much. Can't read it, though. Wait!"

He studied the paper more closely. His face turned white and he read in a harsh, low voice.

"Good ship, Oriental, Captain Hans Vanderdecken in command, the year of 1648." Fisher hesitated, looking up. "That much is clear enough."

Jim Wedge's face mirrored his bewilderment.

"Brother!" he said in a shocked voice. "Ships don't sail around for three centuries."

All trace of humor was wiped clean from Fisher's face. He stood very still, listening to the wind as it hissed through the sails above deck. The cabin was silent, save for the steady creaking of the masts. There was a high sea running, rolling the Oriental slowly from side to side.

"I wish we were sure of that," he said huskily. "I—wish—we—were--sure."

WHAT greeting they would receive from the ship's captain, Jim Wedge and Robert Fisher didn't know. Together, they decided to face Captain Vanderdecken and demand an explanation. Fisher stepped into the sunlight of the upper deck first. The Oriental was at sea. As far as the eye could see, green, rolling water swept away to the horizon. The men of the ship were busy, hurrying about the deck in a workmanlike manner. They paid no attention to the two Americans who advanced hesitantly across the rolling deck.

Wedge stretched himself carefully, breathing deeply of the clean air.

"Damned if I know where we are," he said. "But it's the first good air I've had today. I've a feeling this isn't going to be half bad."

Captain Vanderdecken saw them from his post on the quarter-deck. He approached with the rolling easy stride of a man long accustomed to ships. The wind had whipped new color into his cheeks and his eyes were sparkling.

"You have both rested, I see."

Jim Wedge took command of the conversation automatically. There was something in his superior size and commanding personality that made Robert Fisher happy to let the big man handle his interests.

"Captain," Wedge said firmly, "you've treated us well enough. Aside from that crack on the head, I've no kick coming. What do you propose doing with us, now that your job of kidnaping has been successful?"

Vanderdecken remained silent, as though planning just what explanation he should give. Seamen passed them, so intent on their work that they did not seem to notice the presence of strangers on board. Fisher watched the men of the Oriental with gradually growing concern. More and more he became sure that were he invisible they could pay no less attention to him. At last Vanderdecken spoke, his voice hesitant as though not knowing how much to tell them.

"I know that the hardest part of my mission is to free you men from worry. Unfortunately I cannot tell you everything that will become more evident in days to come. Until an explanation can be given, please trust me . . ."

"Hold it!" Wedge interrupted angrily. "You're not telling us a thing. Are we to consider ourselves your prisoners?"

Vanderdecken's eyes snapped suddenly and an expression of anger became visible on his face.

"I had hoped that time would change many things," he said bitterly. "I find the same intolerance still waiting to keep me from my goal. Yes, gentlemen, if you choose to be unfriendly, consider yourself my prisoners until further notice."

"You refuse to tell us why we were brought aboard your ship?"

"I think it unwise at present," Vanderdecken snapped. "Your only contact is with me. The men are Dutch. They will ignore you until such time as I give them instructions to do otherwise. You will do exactly as I say."

"Then, damn you," Wedge said, taking a threatening step forward, "you may expect nothing but trouble from us. I, for one, will not be dragged about the seven seas. I'll take the first opportunity to escape that presents itself."

Vanderdecken stared at him.

"That would be unwise," he said gently. "If you will look at the rather crude calendar that I keep carved in the main-mast, you will note the date as March first, the year as 1648. I'm afraid, gentlemen, that the calendar is accurate enough to assure you of being picked up by some Spanish galleon or slave ship whose captain would not treat you so well as I intend to."

Fisher remembered the tag in the small chest below deck. His eyes widened in sudden fear. Wedge was not so easily frightened.

"And I say you're a liar!" he stormed. "The days of fairy tales are over. This tub may be dressed up like a flagship of the Spanish Armada. It proves nothing to me, except you and your crew are a bunch of screwballs."

CAPTAIN VANDERDECKEN seemed indifferent to this last outburst.

His eyes were focused on a tiny black dot that was growing

against the horizon. Now he drew a metal tube from his pocket and

walked quickly toward the rail. The tube was about two feet long,

hollow, and bound with brass rings. He stood there for some time,

and when he turned back to his prisoners, there was a strange

glint in his eyes.

"They call this a Dutch trunk," he said, holding the instrument out to Wedge. "Fate has ruled that our first meeting with the accursed Dons would be at this point. If you will look at the approaching galleon through this, I'm sure you'll accept as true what I told you a few moments ago."

Jim Wedge snatched the glass from him and stared through it toward the other ship. A frown crossed his face and he handed the tube to Fisher.

Silently, Fisher stared through the glass at the speck on the sea. Although blurred and imperfect, the image he saw was a huge, black-decked galley, resplendent with bright sails, carved figure-head and a row of black-muzzled cannon that protruded from her sides just below the rail. He turned, the glass held limply in his fingers.

"I guess," he said in a low voice, "that does it. I'm damned sure this isn't my idea of 1943."

Wedge was glaring fiercely at the captain.

"I'm still not so sure that this isn't some sort of a DeMille production," he said angrily. Vanderdecken looked puzzled.

"DeMille?"

Wedge shrugged.

"Forget it, Captain. What do we do now?"

Vanderdecken took the glass once more and studied the Spanish ship for several minutes.

"Equip yourselves with cutlasses from the sea chest below deck," he said abruptly. "We shall engage the Donna Marie before the day is over."

Wedge seemed surprised.

"And just what would the Donna Marie—I take it that's yonder boat's name—want with this old tub?"

Vanderdecken wet his lips.

"There are many things you do not know concerning our ship. For one, we are carrying silver bars in the hold. Philip of Spain needs silver badly. We'll singe his mangy beard before the sun sets this day."

"NIGHTMARE or not," Jim Wedge said to Fisher, "we sure as hell are gonna fight that Spanish ship."

Several hours had passed since their conversation with the captain. During that time, sea chests were broken out and cutlasses distributed to all the men. The gun deck was seething with life. Shot and powder were dragged up from below and everything movable was battened down tightly.

"They say the pen is mightier than the sword," Fisher said, running his finger along the sharp edge of a cutlass. "Right now I wish I'd taken fencing in high school."

The Donna Marie was half a mile to the rear and coming up fast. Fisher and Wedge were drawn close by their common danger. Fisher, smaller and less imaginative, left leadership to his stronger companion. Wedge, in turn, liked the smaller man because of his ready laugh and his willingness to see everything in the best light possible.

They had talked long and calmly of their situation, and decided to make the best of it.

To Wedge's surprise, although Vanderdecken had prepared for battle, the Dutchman kept his ship under a full head of canvas and was making a run for it. Toward five o'clock they saw Vanderdecken coming toward them across the quarter deck. He carried a brace of pistols in his sash and the heavy cutlass dragged against his hip as he walked. There was no alarm in his voice as he greeted them.

"I see you are both armed. The Donna Marie will be within range in half an hour if the wind holds. I attempted to out-run her, although I knew it would be useless."

Wedge interrupted him.

"As little as I know about ships," he protested. "Surely this small ship can be equipped to outsail so large a vessel?"

Vanderdecken shrugged.

"It has been thus before," he said. "Fate decided my first voyage; the others are patterned after it. You had best be resigned to defend yourselves."

He stared at the Donna Marie, now almost within firing distance.

"Just what is to prevent our ship escaping?" Fisher asked.

"You will understand all these things in due course," the Dutchman said. "Meanwhile, be careful. The Spaniards fight trickily, so keep a wall at your back lest they strike from behind."

He wheeled and left them alone. Fisher stared at Jim Wedge.

"I'm damned," he said, "if I like this. I wonder if he really wants us to come through this alive?"

THE Oriental was ready for battle. Men with loaded

muskets swarmed high into the shrouds, ready to fire down on the

deck of the Donna Marie. The ship's sixteen small cannon

were loaded, and sweating, grim-faced gunners were ready to light

the fuses. Wedge, keeping his post at the deck house, watched

with fascination as the Donna Marie came abreast of them.

The side of the huge galley was bristling with guns. Men, their

heads bound in bright cloth, stood with cutlasses in their teeth,

ready to board. He heard the thin, high notes of a horn sound

across the water.

Vanderdecken was everywhere, keeping his men in check, watching every inch that the Spaniard gained as it swing alongside. The Donna Marie loosed its first broadside and the sky was suddenly black with smoke as the cannon belched their loads. The shots fell into the water, fifty yards short of the Oriental's hull.

"Good!" Vanderdecken shouted. "Let the fools waste their ammunition."

"That guy's got guts," Wedge said, and Fisher nodded.

"Either that, or he isn't much worried about this attack."

Wedge looked thoughtful.

"You'd think he'd been through the same thing before," he said. "Nothing surprised him from the first."

The Donna Marie was close in now. She heeled over stiffly before the wind, coming on confidently as though all ready to board. The cannon roared again and shot ripped through the upper sails, sending shredded canvas fluttering to the deck. Somewhere aloft, a man screamed and his body hurtled down. Blood spattered as he hit the deck.

Below, the Oriental's guns awakened and sent a volley across the water. Wedge could see them hit and bounce away from the Donna Marie. Some found their mark and wood splinters flew into the air. The main-mast of the Donna Marie crumpled suddenly and crashed to the deck. The sails dipped and dropped into the sea. Men swarmed over the wreckage, cutting the mast loose from the deck.

A cheer went up from the Oriental's gun deck and a new volley followed the first.

The Donna Marie was so close, now, that her sails mingled with the Oriental's canvas and the red and yellow standards, flying from her masts, were almost over Fisher's head. The ships hit and grappling irons flew through the air to draw them tight. The guns of the Donna Marie were pointed high in the air, where they could do nothing but pound at the Oriental's masts.

The Oriental had one chance. Her own cannon were directed low, in a position to blast away at the hull of the Spaniard. As long as they were in action, Captain Vanderdecken had a slim chance.

Fisher grasped the hilt of his cutlass and waited. Ahead of him, Wedge swung his weapon wide and sprang toward the first Spaniard to come aboard. The crew of the Donna Marie swarmed down the ropes or leaped straight from the rail to the deck of the Oriental. Vanderdecken, three men at his side, dashed into the melee with pistols roaring. Men were shouting oaths, screaming and dying about him. Fisher saw Wedge forced slowly backward by the expert blades of the enemy. Wedge was getting the worst of it.

SUDDENLY awake to the desperate situation his friend was in, Fisher

ran forward, swinging the cutlass with anger that amazed him. The

fury of his attack sent Wedge's adversary reeling back and Fisher's

blade plunged into the Spaniard's throat. Wedge gained time, pivoted

and took on another fighter. He plunged the blade deep, ripped it out

savagely and lunged again. It was like a terrible dream. Time after

time he wiped the sweat from his eyes, saw the blurry figure of another

Spaniard rushing him, and fought wildly to preserve his own life.

Always Fisher was near and ready to take advantage of every opening.

"Stick close!" Wedge managed to gasp. "We may... have a... chance!"

Fisher stuck. Below deck, the guns kept up their murderous steady pounding. The deck was slippery with blood. Fisher skidded and fell, staining his coat with the warm moistness of blood.

Fisher, surprised that he was still alive, felt a new, fierce resentment for the men of the Donna Marie. The Dons, Vanderdecken had called them. Each time his cutlass took a Spaniard's life his heart pounded with the excitement of battle.

"She's going down!"

He heard the high, shrill voice above the clanging weapons. It rose and swelled from the throats of desperate men. .

"The Donna Marie is sinking!"

Barooom!

The cannon roared again and again, ripping huge holes into the stricken Spaniard. Both Americans were aware of a new spirit about them. The Spaniards turned and ran as though the Devil were in pursuit. Some fell back, fighting as they went, trying to regain the decks of their own vessel. High in the masts the banner of King Philip of Spain was cut loose and fluttered down.

Abruptly the balance of the enemy broke and fled. They swarmed over the rail of their own vessel, some of them falling into the narrow chasm of water between the ships. Vanderdecken, his coat torn and blood-soaked, was visible again. Seemingly satisfied at the turn of events, he turned toward his own remaining men.

"Free the grappling hooks," he shouted. "She's heeling over."

Fisher rushed in with the men, tearing the grappling irons away and dropping them into the sea. They worked furiously, and one by one the irons clanked free and rattled down the side of the ship into the water.

The Oriental was free. The force of the Donna Marie, pushing against her side, sent the Dutch galiot sidewise and clear of the enemy vessel. Few of the Spaniards had escaped to their own deck without wounds. The Oriental swung around slowly like a wounded animal and drifted free. A bare hundred feet separated the two ships. The Donna Marie tipped far over, the huge gap in her side already below the water line. A boat swung free from her and bobbed across the water. A white flag hung limply at the bow.

"Give them a taste of grape!" Vanderdecken shouted. "Let none escape that bloody hell-ship!"

Fisher watched the men in the boat as she drew close. He pitied the poor devils, and yet, had they not tried to murder them all?

Sick revulsion twisted within him as a single cannon exploded and sent grape shot into the doomed boat. A broken, bloody mass of wreckage, it sank quickly, leaving no trace. His eyes shifted to the Donna Marie. The galleon heeled far over and slipped quietly beneath the waves. A cheer went up around him.

JIM WEDGE had his hat in one hand, cutlass swinging limply in

the other. There was something about Wedge, standing strong and

undaunted in the midst of death, that sent a shiver up Fisher's

spine. It reminded him of something or someone he had seen once

before. Some bit of bloody glory that he had witnessed as in a

dimly remembered dream.

Fisher fancied at that moment that Wedge, and not Vanderdecken, controlled the fate of the Oriental. He was proud of his companion, and yet filled with a fear that he could not explain.

Wedge turned and approached him with graceful, firm steps.

"It's to hell for the Donna Marie," he said crisply. "Thanks for the help when I needed it most. I hope they can get this tub back into sailing condition."

Fisher leaned weakly against the rail.

"I guess we've had our baptism of fire," he said.

"But good," Wedge replied gruffly. "Bob, this beats selling insurance after all. Let old Vanderdecken keep his secret for a while. I'm beginning to enjoy life aboard the Oriental."

Fisher wondered. Wedge was so damned cock-sure of himself. He closed his eyes, trying to refresh a fuzzy memory. It was useless. Wedge fitted into this as though he were meant for it. He couldn't toss away the idea that he had seen Wedge like this before, self-assured, ready to plunge into battle with the odds ten-to-one against him.

"Hell for the Donna Marie," Fisher repeated softly to himself. "I wonder if this is only the beginning."

WEDGE said, "I'm sure that the sinking of the Donna Marie was no surprise to Captain Vanderdecken."

Fisher nodded in agreement.

"I remember how he seemed to anticipate every move," he agreed. "We were fighting terrific odds, and yet he never faltered. Yet, I'll swear he's not the type that likes a fight."

It was late in the afternoon, the third day after the battle. The Americans were stretched full length across the main hatch, staring at a cloudless, empty sky. The Oriental's masts were patched and repaired and almost all trace of the battle had been removed. The deck-house still showed jagged holes where cannon balls had blasted through it.

The Oriental had been quiet, almost too quiet for the past two days. Although they understood nothing of what the crew said, men had gathered in little groups and talked among themselves until they were ordered apart by the mate. They lounged about afterwards with scowling faces.

Several times since the battle, Fisher had caught the mate, a huge Dutchman named Hendrik von Rundstad, staring at him as though puzzled by his presence. Von Rundstad had a sour, unhealthy look about him that worried both Fisher and Wedge.

Fisher agreed with Wedge on the subject of Captain Vanderdecken. The captain had a manner of dashing away in time to stop some minor disturbance. Each time, he returned to them with a satisfied smile, as though his life was being lived with a precision that satisfied him.

"Jim," Fisher said suddenly. "Has it occurred to you that we're taking all this pretty calmly?"

Wedge rolled over on his side and scowled.

"I don't know that I understand you." Fisher sat up.

"I mean, being thrown into this impossible situation. A couple of business men torn up by the roots and tossed into the past. We go on as though nothing had happened, and yet Vanderdecken refuses to tell us a thing. Why do we go on as though we were actually..."

He hesitated and Wedge smiled.

"As though we enjoyed it?" he offered. "To tell the truth, Bob, I do get a kick out of this new life of mine. I got mixed up in an unpleasant situation in New Orleans. That battle with the Donna Marie satisfied something inside of me. It brought a content that I've never known after any undertaking I've been through before."

"I know," Fisher said impatiently. "But the future—what of that?"

"Let the future take care of itself," Wedge urged. "The captain has a plan. How he engineered all this is beyond me. The past is cut off and we can't return to it. Either we follow the path he has suggested or we'll lose what little sanity we have left. There's no choice."

Fisher got to his feet.

"Another thing!" he said. "These Dutchmen are planning trouble. I don't like the looks of that goon, Hendrick von Rundstad. Every time he looks at me, I feel a rope around my neck."

Wedge allowed an unconcerned grin to twist his lips.

"Von Rundstad isn't so tough," he said. "I've a hunch we can handle him if he starts anything."

It was dark, now, and they crossed the deck slowly, watching the stars as they grew brighter above the whipping sails.

Just before Wedge slept, his mind wandered to Dave Laird and the fight they had had not so many days ago.

"Maybe not an easier life," he said aloud. "But a damn sight more interesting one."

Fisher stirred in his sleep and muttered something Wedge couldn't make out.

"Nothing," Wedge said. "Get some sleep, boy. I'm just thinking out loud."

IT WAS close to morning when Wedge awakened. He sat up

quickly, ears and eyes alert to the faint sounds above. He

reached for his cutlass. The sounds came again, padded footsteps

on the deck.

Wedge arose swiftly and slipped into the boots that the sea-chest had supplied. He decided against awakening Fisher. There was probably no reason for alarm.

He reached the deck swiftly and stood deep in the shadows of the hatch way. Shadowy forms were crossing the planks, converging near Captain Vanderdecken's cabin. The gray light of dawn was visible, and the ship rocked and bucked gently in the wind. Wedge waited, then saw von Rundstad, the mate, knocking on Vanderdecken's door.

They closed in like a silent wolf pack. Wedge wondered how he could know so much about these men and what they were thinking. He was sure it was mutiny. The mate carried a cutlass in one hand and a pistol in the other. The men carried on a whispered conversation that, even if Wedge were able to hear the words if he were closer, he would not have understood.

Wedge saw a lantern light up through the window. He held his cutlass tightly, waiting. Captain Hans Vanderdecken stepped out of the door, bathed in the yellow rays of the lantern. Neither surprise nor fear showed in his expression. His voice was low and controlled, and several of the crew stepped away from him, as though impressed with his argument. The men were hesitant, but von Runstad stepped forward, pistol leveled at Vanderdecken's chest.

A horrible fury filled Wedge and lie sprang forward. The crew shouted their encouragement to the mate and Wedge heard the pistol roar. He stopped short, saw the captain pitch forward on his face and lay still.

Wedge knew that thus far the crew had not noticed his approach. Armed only with the blade, he would stand no chance in fighting them. He turned and slipped back into the shadows of the deck house. Two men were dragging Vanderdecken back into his cabin. The group was dispersing. The mate entered the cabin, and for several minutes there was activity around the lantern inside. Then the light faded and the two men followed von Rundstad to the deck. They were headed directly toward Wedge. He went down the stairs quickly, and back into the cabin where Fisher was still sleeping. He bolted the door and waited. They did not follow and for a long time he sat alone, waiting for Fisher to awaken. The sun came up at last, with the glinting hardness of copper. Fisher rolled uneasily in his sleep and muttered under his breath.

WHEN Bob Fisher awakened, Wedge was still sitting on the edge

of the bunk. He said nothing until Fisher was dressed and about

to go on deck. Then he said:

"Von Rundstad and the crew have mutinied. Captain Vanderdecken is in his cabin, either dead or badly wounded."

Fisher turned, his eyes showing alarm. "How did you . .

"I awakened when it happened," Wedge went on. "I let you sleep because there was nothing we could do about it."

"Now we are in trouble," Fisher said. "The more we see on this ship, the less I understand."

He wandered across the cabin, turned and paced back again as though afraid to go beyond the door.

"We've lost our last chance to escape," he said. "Von Rundstad will get rid of us fast, now that he has control of the ship."

Wedge stood up and went to the porthole. He stared out at the sea.

"I'm not so sure," he mused. "Von Runstad had plenty of time to kill us this morning. He's left us completely alone. I stayed awake to make sure he would."

Fisher scowled.

"Don't you believe it," he cautioned. "He'll take care of us when the time comes."

THE Oriental had good sailing weather for the next week. Those seven days were a nightmare for Bob Fisher. Wedge felt a little better, though his ability to feel at home on the ship helped somewhat. They were allowed the full freedom of the deck. Food was brought to their cabin as usual and the crew maintained complete silence. Vanderdecken was missing but his absence was the only change.

Wedge tried on two occasions to reach the captain's door. Each time he was turned away by the appearance of half a dozen husky seamen. Yet he was sure that Vanderdecken was yet alive. Food was taken to his cabin twice daily, and by the middle of the week he could be seen moving about inside.

Von Rundstad was in complete charge of the ship. He pushed the men every hour of the day, keeping the Oriental >under a full head of canvas. The big ugly Dutchman carried both pistols and cutlass constantly and swaggered about the decks at all hours.

To help Vanderdecken was out of the question. The two Americans were fortunate to have saved their own necks. They went about the ship quietly, taking what food was offered them and avoiding von Rundstad. The mate paid them no more attention than if they hadn't existed at all.

Slowly, Fisher's interest in the sea grew, until life was more bearable for him. He and Wedge spent long hours mastering the ways of the Dutch galiot. Wedge taught him the use of the cutlass and they both hardened themselves to the life they were living.

The second week crept by and the Oriental still tossed and bucked its way southward on an empty sea. On the eighth day, Fisher was leaning over the rail, watching gulls that flew in from the east. Against the horizon a huge, black rock appeared, rearing upward into the sky as they came closer. Fisher rushed to the cabin and awakened Wedge, who had been resting throughout the afternoon.

"Gibraltar!" Fisher shouted. "We're headed for Gibraltar!"

Wedge sat up dazedly.

"You're nuts," he protested. "You can't cross the Atlantic in less than a month on a tub like this."

Fisher was too excited to be easily discouraged.

"I saw it, I tell you." He hauled Wedge to his feet. "It's ahead and slightly to the east of us. You can spot it without the glass."

With one landmark, one familiar thing to base their hopes on, both men rushed to the deck. The Oriental had come around and Gibraltar, stark and black against the sky, lay dead ahead. Even Wedge could no longer doubt after that first look. He stared for a long time, some of the bewilderment leaving his face.

"Do you realize that to sail here from New Orleans would take months on this vessel?"

Fisher waited. His own ignorance of the sea forbade any reply. Wedge grasped his shoulders, staring at him with wonderment in his eyes.

"You know what that means?"

Fisher shook his head.

"It doesn't make sense to me," he confessed.

Wedge retained his grip. An awed look filled his eyes.

"We didn't sail from home," he said in a low voice. "This is the last proof we need that this voyage is beyond understanding. The Oriental is a Dutch ship. We fought the Donna Marie a few days after we left port. In 1648 the Spaniards fought Dutch and English ships as soon as they came into Spanish waters. I tell you, Bob, this thing is beginning to make sense, and I don't like it."

HIS hands dropped to his side and he leaned over the rail with

eyes glued on the huge rock ahead.

"It doesn't add up for me," Fisher confessed. "What are you getting at?"

Wedge whirled around.

"We're in the past, all right," he said in a hushed voice. "We're headed into the Mediterranean, just as Dutch and English ships did centuries before our time. Vanderdecken told us we were here for a purpose. We're a couple of pawns to be played when the time is ripe."

"We can make a break for it at Gibraltar," Fisher suggested. "There's a narrow strait there. We could jump ship and swim ashore."

"No good," Wedge's lips tightened. "If I'm right, and we've no reason to think otherwise, this is Gibraltar of the Seventeenth century. The Bloody Rock, ruled by cutthroats and pirates. A thousand miles of hell on either side, one overrun by Berbers and Moslems, and on the other, King Philip of Spain with his armies."

Fisher had no answer. He was staring at the towering stone giant that grew larger as the Oriental swept onward ahead of a fresh, strong wind.

CAPTAIN HANS VANDERDECKEN was on deck again. He had been escorted from his cabin each morning for a week, by two husky seamen. There was a difference in the spirit of the men on board. They still obeyed von Rundstad, but the man was so overbearing that hatred seemed to be growing against him. The galiot had been anchored for a week in a small cove on the Spanish coast. The mate was waiting for something. Perhaps he feared the passage through the Inland Sea until such time as the Oriental could be repaired for the journey.

Twice, Fisher had seen men whipped by the mate himself, who wielded the cat-o-nine tails with the dexterity born of long practice. The crew grew weary of him. More and more, Fisher felt, Vanderdecken was taking over his old place at the helm.

Sunday afternoon was hot and still. The sun burned down, blistering the planks of the deck and sending men over the side into the cool water. Vanderdecken was much better. Although he had been allowed to talk with no one but the two who guarded him, the captain had a new look of confidence about him as he walked about the deck in the quiet of the afternoon.

A tension sprang up, as though wills were about to clash and no one would guess from where the storm would first come. Captain Hans Vanderdecken left his cabin, alone. The mate was sitting by himself on the steps that led to the quarter deck. Vanderdecken walked toward him slowly and several of the crew fell in behind. Fisher edged closer, careful to keep out of the group of grim-faced men.

Vanderdecken halted a few steps from the mate and spoke to him in a calm voice. Von Rundstad had evidently been dozing in the sun. He sprang to his feet, jerking his cutlass free of his sash. With legs braced well apart, he faced the members of the crew who gradually moved in behind their captain.

He bellowed something in a loud, angry tone and took a threatening step forward. Vanderdecken held his ground. He reached behind him and took the hilt of a blade one of the men held for him. The men backed away slowly and a look of cunning came into von Rundstad's eyes. Fisher, realizing what was about to happen, went closer. He was afraid the Dutch captain was still too weak to face the weapon of the mate.

Vanderdecken danced in swiftly to deliver the first blow and their blades met, von Rundstad's coming down full force to be halted in mid-air and pushed aside.

The mate charged like an angry bull, slashing huge arcs in the air but gaining no blood for his trouble. Vanderdecken was fast. The circle of men widened and the captain went in again swiftly, his blade playing a ringing tattoo against the mate's weapon. They fought warily, each dancing about, taking the touch of metal as sparingly as possible. The captain was light on his feet, but the mate, sweating and swearing under the hot sun, started to blunder and stumble when he was in a tight spot.

How long they parried thrusts, Fisher wasn't sure. The sun grew so hot that he ripped his collar away. His tongue was dry. Still the men danced around each other. Thrust, parry and thrust. Von Rundstad was growing worried. Much heavier than his opponent, he couldn't hope to last much longer. Also, there was the feeling of shocked surprise that his men had turned against him. It shone in his eyes, the look of a betrayer betrayed.

The final blow was swift and came so suddenly that Fisher felt let down and disappointed. He had been hoping for von Rundstad's death. Vanderdecken's weapon darted in swiftly, touched the mate's wrist and it was over. Von Rundstad's cutlass flew from his nerveless fingers and he stood there like a bewildered ape, holding a severed, blood-soaked finger. His wrist was cut to the bone and the finger, where Vanderdecken's weapon had slipped downward, had fallen from the hand completely.

Vanderdecken wiped the blood from his blade and stepped back. He gave a single low command and the crew closed in on von Rundstad.

Fisher turned to go to his cabin. Wedge would want to know that the ship had once more changed command. To his surprise he discovered Jim Wedge had come out on deck and was standing just behind him. The same devil-may-care expression that he had had during the battle of the Donna Marie, was on his face.

"I guess Vanderdecken knew what he was talking about when he told us to depend on him," Wedge said. "From our viewpoint, that fight wasn't so much, but considering the times, Vanderdecken is pretty handy with a steel blade. You saw that, didn't you?"

WITH Hendrik von Rundstad's downfall, the Oriental set

sail at nightfall under a full head of canvas. Fisher spent hours

in the shrouds, his glass trained on the galleys that swept past

them toward the African coast. Vanderdecken remained more and

more to himself, and never spoke to them, even though he was once

more free of his cabin and busy above deck.

Inside the straits, the Oriental was left unmolested and kept so true a course that they were sure she was now close to her destination. Wedge was busy below deck, working on a crude calendar he had cut into the beams of the cabin. Fisher watched life on the deck below him. The carpenter was busy building a large cage-like affair of heavy wooden slats. He had worked on it since that morning and the crew detoured widely each time one of them came close to him. There was something about that cage with its solid plank bottom and heavy bars that sent a vague uneasiness through Fisher's mind. The men he had seen today were tight-lipped and grim. The Oriental was suddenly a silent, brooding ship.

Wedge came on deck, dressed in new breeches and a pair of high boots. Vanderdecken had supplied them both with new clothing of his own time, and Wedge looked the part of a swashbuckling hero.

Hans Vanderdecken was calling all hands on deck. They lined up, a nervous, bewildered group who knew they deserved punishment and hoped they could evade it.

Hendrick von Rundstad was dragged into the sunlight before them. This was a different man than the swaggering, bullying mate who had engineered mutiny. He staggered and fell before the captain. When he rose, his shaggy head was bent forward, eyes staring at the deck.

Fisher, climbing down slowly, heard the captain speak and the protesting shout of the mate. It was the first time he had spoken in English.

"Not da basket! Please Cap'n, not da basket!"

Vanderdecken stood firm as several men dragged the carpenter's creation across the deck and placed it near the rail. Fisher reached the deck and went closer. Von Rundstad howled as though he were being murdered. Men grasped him by the arms and dragged him toward the cage. They forced him into the wide hole at the top. He grasped the bars and started to shake the cage like a gorilla, shouting and sobbing at the same time. The carpenter nailed the slats down firmly.

The men lifted the cage to their shoulders and carried it to the rail. They attached a heavy rope to the top and tied the other end firmly to the rail. With only the voice of the mate to disturb the silence, the basket was tossed over the side.

The rope went taut, held and the basket bumped loudly against the side of the Oriental, and it hung motionless just above the waterline. Fisher felt warm and cold at once. Perspiration stood out on his face and the palms of his hands. He clenched his fists tightly, trying to remain calm and undisturbed at what had happened. They were going to leave the poor devil hanging there in the sun until he rotted and died.

As much as he hated von Rundstad, Fisher remembered that the mate could have murdered Vanderdecken long ago, yet had let him live. Fisher didn't know that the men feared Vanderdecken so much that they refused to let him die. He could think only of the man in the basket, swinging to and fro in the wind until hunger and heat drove him stark, raving mad.

He walked quickly toward the captain. Vanderdecken and Wedge were talking quietly. The men were once more back at their posts.

"Good lord, Captain," Fisher blurted. "You can't—I mean, how can you do this, even to an animal?"

Wedge looked at him queerly.

"Get hold of yourself, Bob," he advised. "The captain has to maintain discipline among the men. He' can't chance another mutiny because he fails to punish the leader of this one."

Fisher was sick of the whole thing. He had never expected Jim Wedge to side against him at a time like this. He turned to the captain.

"Then you intend to—to let him die down there?"

Vanderdecken's eyes were cold as ice.

"There is one thing you must understand," he said without visible emotion. "The basket is cruel but mutiny calls for harsh measures. When Von Rundstad has enough, he can escape. We supplied him with a knife."

Wedge chuckled.

"If he needs rest, Bob, he can always cut the rope."

Something in Fisher's brain snapped like a tightly wound watch.

"You're a damned fool," he said fiercely. "You're turning into a heartless, miserable pirate like the rest of them."

He turned and went blindly across the deck to the stairs.

ROBERT FISHER slept little during the next ten days. Wedge moved to one of the smaller cabins and left him alone. Jim Wedge had tried to be friendly, but after their quarrel, Fisher preferred being left to himself.

Fisher roamed the deck by day and most of the night. His eyes held a fanatical gleam of hatred for everyone around him. Twice he attempted to cut the rope that held Von Rundstad's basket above the water. Both times he was hurled back by Vanderdecken's men and left cursing on the deck. The last time he had gone to his cabin, crying out for Vanderdecken to have mercy on a dying man.

Hendrik von Rundstad was slowly going mad. He shouted and pleaded for his life until he was too hoarse to speak above a whisper. Then he crept around the swaying cage, his shaggy head weaving from side to side, skinny hands clutching the bars. The men themselves, troubled by Fisher's attitude and watching the mate refuse to die in his cage, tried to get Vanderdecken to change his mind. The Dutchman remained unmoved by their pleas. He and Wedge were spending more and more time together, walking the deck alone.

On the tenth day Fisher awakened from his nightmare to hear the steady bump-bump of the basket as it swayed against the ship. He went to the deck, thanking a merciful God that the day was cloudy and the sea calm. Hurrying to the rail, he stared down at Von Rundstad. The mate lay motionless. Perhaps he was still asleep. One clawlike, bony hand protruded from the open bars of the cage.

Fisher took a cautious look about. He was alone on this section of the deck. Drawing a pocket knife, he stole forward to where the rope at the rail supported the cage below. With a quick motion he slashed the rope and sent the mate's makeshift coffin plunging into the sea. He left the rail and went down to his cabin. As he slammed the door behind him, the high thin voice of the watch came from the crow's nest: "Tunis—dead ahead!" Fisher sank face down on the bunk. He heard footsteps on the deck and Captain Vanderdecken giving orders.

"Give her a full head of canvas. Well make port by noon. All hands into the shrouds."

"Tunis or Hell," Fisher thought bitterly. "Let the bloody murderers sail where they want to. We'll all die when the time comes."

The picture of Hendrix von Rundstad's insane eyes had burned an unforgettable picture of horror into his tired brain.

JIM WEDGE had no intention of missing any part of new

developments. He was at the wheel, staring through the glass at

the white, flat-topped houses and the colorful galleys along the

far shore.

"A beautiful sight from a distance," a voice said from behind him.

Wedge nodded without looking away from the city ahead of them. Captain Vanderdecken waited until he turned away from the view. The captain's face was grim.

"You see Gouletta from here," he said. "Tunis is inland. We reach it by small boats through the canals."

"We stop at Tunis?" Wedge asked.

"Tunis," Vanderdecken said quietly, "is our goal."

Goal? Then, perhaps, they would know what fate held in store for them. The Oriental was already close in. A Moorish galley swept past them toward Gouletta. The high banks of oars moved in swift precision. Blackamoors were visible, scurrying along the deck of the strange craft. Wedge turned once more toward the glittering, walled city ahead of them.

"I must warn you that from now on you must never interfere with my actions," the captain said. "Christian ships are not welcome here. The Dey is king of the cutthroats. He rules Tunis with an iron hand and demands a share of booty from all who use this port. English Free Rovers use Tunis for refitting their ships and selling their riches. In turn, the Dey demands steady toll from them. If we were to meet one of these galleys at sea, they would not hesitate to sink us and kill every man on board."

Without looking around, Wedge asked casually:

"Will it be possible for you to tell us what is to become of Fisher and myself? The kid's pretty upset. It wasn't that he had any love for the mate. He thinks we're all against him and it's driving him half crazy."

Vanderdecken nodded.

"I know," he said. "I had hoped that such things would affect him strongly. I'm afraid he will have another shock before the day is over."

"Damn you, Vanderdecken," Wedge exclaimed good-naturedly. "Sometimes I get the feeling that you know every act of this play we're in. I wish you'd take me into your confidence."

The captain stared at Wedge's tall figure a little wistfully.

"You are a clever man," he said. "I think also, a tolerant one. Perhaps through you, more than anyone else, my voyage will end successfully."

"You flatter me," Jim Wedge said. "I'd feel a damn sight better if I knew what was coming next."

The Oriental sailed quietly into the blue waters of the bay. The sails were furled and the anchor slipped into the water to halt her slow progress. There were several galleys anchored close to them and an African slave-ship near one of the docks. Black men and women were chanting sadly as they trudged slowly up the plank and into the hold of the slaver.

A small bright barge swept away from the shore and cut the water toward the Oriental. Wedge could hear the fat, turbaned official giving loud orders from the bow. The barge came alongside the Oriental and the black-moors rested on their oars. Two of them lifted a long, tightly bound bundle between them and climbed over the rail. The bandy-legged official followed, grunting as he reached the rail and jumped wearily to the deck. Vanderdecken met him.

The official offered a pudgy brown hand and the Dutchman ignored it coolly. The blackamoors dropped the bundle at the captain's feet and stood like two grinning black apes with their ham-like paws on long, curved blades.

Near the docks the steady throbbing of drums started and unfamiliar instruments screamed wild, discordant music that swelled above the war drums.

"We have come on the mission that the Red Widow could not perform," Vanderdecken said quickly. "The great captain of the Red Widow asks you to accept our riches and send the hostages aboard at once."

IT WAS obvious to Wedge that the war music and the grinning

complacency of the official were troubling the Dutch captain. The

faces of the blackamoors were equally unpleasant. The turbaned

Moor allowed an ugly grin to pass over his face.

"We could not bring all the hostages with us," he said. "You were to arrive here on the thirtieth day of the third month. You are late. The Dey would not wait for you."

He pointed a dirty finger at the bundle on the deck. Vanderdecken's lips trembled strangely.

"You—you have not..."

The Moor leaned over and ripped a portion of the bundle open with his dagger. Wedge leaned forward and his face turned an ugly gray. Vanderdecken's breath sucked in loudly.

The face of a dead man stared up at them from the partly-opened bundle. Vanderdecken sank to his knees, drawing the shroud down to expose more of the body. The Moor backed away and the blackamoors drew their weapons.

"The Dey bargains only once," the Moor said harshly. "You did not keep your promise."

He scrambled over the rail quickly. The drums were pounding loudly along the shore. Two galleys started to close in on the Oriental. Vanderdecken sprang to his feet.

"Up anchor!" he shouted. "Clap on all the canvas we have. Move, you dogs, or we'll all rot in Tunis!"

The anchor rattled out of the water. Men sprang into the shrouds. Wedge, standing above the body on the deck, knew nothing of what went on. He was aware of Bob Fisher, as the New Yorker's shadow fell across the body of the dead man.

The corpse, stiff and blood-soaked, was a duplicate of that of Robert Fisher.

It could have been his twin. A knife had slashed the neck from ear to ear.

Fisher, as he stared down at the corpse, straightened like a marble statue and the blood drained from his face.

JIM WEDGE covered the body quickly, but he was too late. Fisher dropped to his knees, drew the shroud away again and stared into the wide, lifeless eyes. His breath came audibly and his eyes as they turned upward to Wedge's were wild and blood-red. He held a finger to his own neck, tracing the path of the knife.

"My God, Jim," he whimpered pitifully. "It's me!"

He stood up. His hands were clenched tightly as he stared at the lifeless figure.

"You'd better go below," Wedge said. His voice was harsh. "There's nothing you can do here. Whoever the man is, he can do you no harm."

Fisher took a threatening step toward him.

"Damn you, Wedge!" he shouted. "For a month you've been ordering me around. Now I see myself lying there with a knife slash in my throat and it doesn't worry you at all."

His voice rose to a shrill scream.

"You can't hide from me any longer, Wedge. You're a pirate like the rest of them. I'll kill . . ."

Wedge clutched his shoulder and pushed him toward the hatch.

"Shut up, Bob," he said coldly. "You don't know what you're saying."

Fisher wrenched loose.

"I'll go," he said, almost whispering. "But look out for me, Wedge. I'm going to get all of you before I'm through."

Wedge looked tired.

"Go to bed, Bob," he said. "If I could have chosen a companion for this voyage, I wouldn't have taken a sniveling fool."

He stood alone, watching Fisher go below deck. Then, without emotion, he picked up the corpse and tossed it over the side.

"Perhaps," he thought, "things affect me differently than they do Fisher. The boy's all right but he can't stand this life. There must be a solution to all this, but with a crazy man on my hands, it's going to be harder than ever to find it."

THE Oriental slipped from the Bay of Tunis with the

help of a strong wind. The Dey's galleys were in hot pursuit but

once on the broad waters of the inland sea, they were no match

for the swift little Dutch galiot. Then came the long, restless

repetition of the first voyage all over again. The decks were

badly weathered, sails needed repair and the masts needed

refitting. Barnacles were clinging to the hull from the long stay

at sea.

Jim Wedge found himself more and more alone. Fisher was beyond reason now. West of La Coruna, Spain, one of Philip's galleys challenged them to battle and managed to send a shot over the Oriental's bow. Vanderdecken was no longer wasting time. The Oriental kicked up her heels and made a run for it, leaving the Dons to curse in her wake.

Vanderdecken spent long hours on the quarter deck, searching the horizon with his glass. Wedge, waiting for the next phase that he was sure would come, wandered for hours about the deck remembering the pleasant life of New Orleans and wished more and more that he had never quarreled with Dave Laird. From Vanderdecken he learned that the Dey had murdered sixty men, women and children—all English—because the Oriental had not arrived on the proper date. This was all the information the Dutch captain would offer and it left Wedge in the dark as much as before. Who the corpse had been, he could not guess; but the strange resemblance between it and Bob Fisher drove him almost mad.

Wedge kept his own calendar carved on the wall of his cabin. He figured roughly that a month and eight days had passed since that foggy night in New Orleans. On the eighth day out of Tunis, while working with his calendar, he was suddenly startled by the stealthy scrape of boots inside the cabin door.

He looked up quickly, to find Fisher moving toward him like a stealthy cat, cutlass held point forward in his hand. Fisher's face was white as a sheet and a wild light of hatred shown from his narrowed eyes. Wedge realized that his own weapon was on the far side of the room. Fisher came toward him slowly, cutlass raised.

"Bob—wait!" Wedge cried. He tried to jump aside but the cutlass came down in a wicked arc, hitting him on the shoulder. He felt it rip his flesh like white-hot metal. Bright sparks flashed in his brain and he plunged forward into darkness.

WHEN Wedge regained consciousness he was alone in the

cabin. His shoulder ached badly. Placing a hand on it, he

realized it had been bandaged. He stared at the ceiling, trying

to collect his thoughts. The kid must have gone raving crazy to

attack him like that. Wedge wondered why he wasn't dead.

He heard footsteps outside, saw Vanderdecken come in and closed his eyes tightly as the captain came toward him.

"Are you awake?" he asked quietly. Wedge nodded. He didn't feel like talking.

"Fisher is in chains below," Vanderdecken said. "I had been watching him closely. I'm sorry I did not arrive in time to save you the wound."

Wedge sat up, painfully leaning on his good arm.

"Thanks," he said. "I guess the kid saw too much in Tunis. It's sent him out of his head."

Vanderdecken seemed to want to open a conversation, and didn't know just how to go about it.

"I'm sorry," he muttered at last, "that I caused hatred between you and your friend."

Wedge's lips tightened.