RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

Fantastic Adventures, June 1943, with "Citadel of Hate"

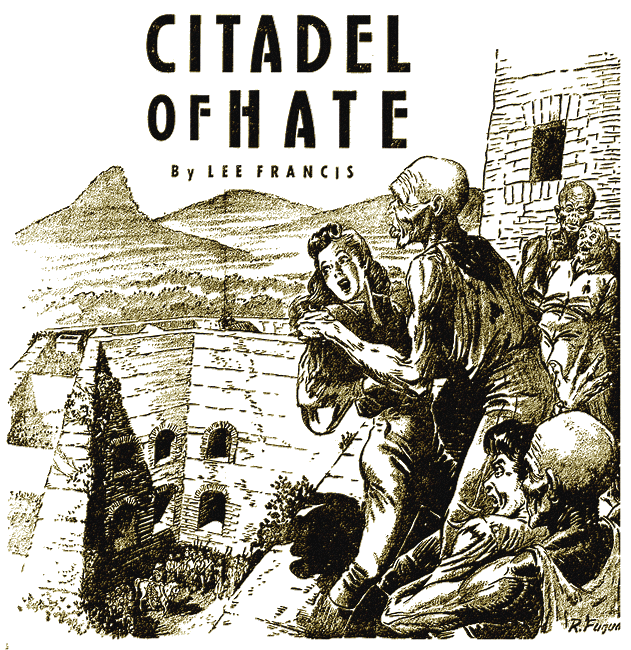

King Christophe came back from the dead to regain his kingdom. Between him and victory were four people and a golden bullet.

I'LL never forget that first morning the S.S. Berwain rocked gently at anchor on the bay of Cape Haitian. Perhaps, if it hadn't been for George Weston's urgent note, I would have spent another week on board with Captain Wingate, touching the islands of the Caribbean. I knew Professor Weston needed me—and badly. His letter, addressed to me in New York, was creased and dirty in my coat pocket:

Christopher Weils,

Annipol Hotel,

New York City.

Chris:

For once in my life, I'm going to depend on our friendship and that alone to bring you to Haiti as speedily as you can make the trip.

I cannot, for reasons that will later be evident, give you any reason for coming. Suffice to say, that you know I never fly off half-cocked.

I came here for research. I have found a country tottering on the edge of disaster. I, also, am involved. I'm depending on you, Chris. Meet me on August 27 at Cape Haitian.

Your old friend,

George Weston.

I read the note over a dozen times during the trip down.

Haiti is not strange to me. In fact, very little of the world is.

Weston knew my love for trouble, be it of the small or desperate

variety. I believe his knowledge of the scraps I've been in,

prompted his note. I couldn't let him down.

That morning, sitting there off shore, I wondered about the strange 'disaster' he mentioned. Before us lay the curl of beach, banks of sugar-cane stretched inland and beyond the green forest. There was no sun in the scarred, bottomless ravines that ran back into the mountains. Over Haiti, that same smouldering look of the past was evident. A country nursed with blood and hate.

I heard the gruff voice of Captain Wingate as he emerged from his cabin. A boat scraped against the side of the S.S. Berwain, and we were headed for the coral beach. Half a dozen native blacks pulled at the oars.

The jetty was covered with grimacing black men and women. Stacks of mangoes, bananas and alligator-pears were everywhere. I stepped out of the boat to look for the gray-haired Professor Weston somewhere in the throng of wooly heads. He was nowhere in sight.

A HUGE black man came out of the mêlée. His body was enormous

and shining. He came straight toward me, a big grin on his face

and bowed shortly with his shoulders.

"White fella' look for Mr. Weston?"

His face was black as ebony. A red scar cut across his chin and gave his mouth a natural sneer. His arms were big and muscles rippled under dark skin.

"Weston?" I repeated slowly. "I'm looking for no one."

A moment later, I was glad that I had lied to him. An expression of bewilderment crossed his face. His head darted around and he seemed to be looking for support from someone in the shadows beyond the jetty. I studied the buildings that rotted along the shore. No one seemed to notice him. He turned toward me again.

"Mr. Weston say you are young man with red hair, much big muscle and blue eyes," he repeated the words mechanically. "I am sure you are Mr. Wells."

"Suppose I am?" I liked the man less and less.

"Mr. Weston say you come with me," he invited. "He wait for you in his carriage."

That wasn't like George Weston, I knew.

The black turned on his heel and threaded his way swiftly down the jetty. Trying to dodge among the piles of fruit and cages of parrots that seemed to dominate the place, I followed. The snug feeling of the small automatic I carried under my coat made my frame of mind a little less uncertain.

We reached the end of the dock, and hurrying to keep pace with my man, I found myself in one of the huge, rotting warehouses that line the bay. It was dark and cool inside and evidently a shortcut to the street beyond. The black was nervous. I flatter myself that I was a tougher-looking customer than he had anticipated.

There were three piles of sugar-cane close to the entrance. We passed the first and I realized suddenly that he was no longer with me. I stopped in my tracks. A short dash would have placed me in the safety of the street.

Shuffling footsteps sounded behind me. Whipping about, I drew the automatic from my belt. A black man was close to me, his face an expressionless mask. His hand was gripped about the handle of a broad cane-knife.

I dodged swiftly to one side and fired as I dropped. The heavy blade of the knife swooped down in a wide arc and missed my head by inches. I tried to roll over quickly and saw him double up with pain. I had placed the shot in his chest.

As I came to my feet, the black with the scar chin was close to me. His fists were balled into huge lumps. He lashed out as I tried to regain my balance.

"Wham!"

A sickening pain surged through my head and I staggered backward against the pointed sticks of cane. Lying there half conscious, I heard far-off voices and cursed myself for having so neatly walked into a trap. It was useless to attempt to move. My body seemed paralyzed by the blow. I closed my eyes and darkness swirled over me.

I LEARNED afterward, that the black man with the red scar was to be my bitterest enemy as long as I stayed in Haiti. I learned that past his grinning inspection went every black slave who was later to serve in the hell-gangs of Henri Christophe.

But all this took place weeks later. At the time I was trussed carefully and tossed into a wooden-wheeled wagon. Straw and cane were thrown over me.

From George Weston, I learned that he had been waiting in the street that day I arrived.

Weston had arrived in Cape Haitian six months before, with his daughter Helen. I remembered George as a slightly-built professor of history at the eastern college I had attended. Weston was a man of fifty, with keen gray eyes behind thick-rimmed glasses. He never tired of these summer trips that resulted in new material to be analyzed during the winter months. Helen, twenty, and the owner of the sweetest smile I have ever looked upon, always went with him.

They sat in their carriage close to the jetty, waiting for me to arrive. Weston wasn't afraid for me. He had no way of knowing that his mail was tampered with; that plans were made well in advance for my quick disposal. The boats from the ship landed and went away again. Weston leaned forward in his seat, waited eagerly for some sign of the red hair I'm attached to. I must have lost myself quickly in the crowd, because he never saw me. At last he turned to Helen:

"I'm sure he was on that ship," he said. "He wired that he'd look for us here."

Helen Weston frowned.

"Dad! Those devils couldn't have found him first?"

Weston looked uneasy.

"I think not," he said. "No one but ourselves knew he would be here."

A small ox-drawn cart emerged from the building before them. It was piled with sugar-cane. A great black man with a red scar on his chin was driving the beasts. If Weston had known that I lay under that cane, I'm sure the events that followed would have been greatly altered. He remembers having noticed the satanic grin on the driver's face as the cart rolled slowly past.

"That man frightens me." Helen shivered.

"He was a tough-looking customer," Weston admitted. "The blacks are thoroughly stirred up, Helen. If Chris doesn't get here, I'm going to have to ask for help higher up."

The girl turned and watched the ox-cart move out of sight in the dust of the road. She placed a small hand on her father's knee.

"This thing is too much for us," she said slowly. "Even for Mr. Wells. No one man can face the wrath of a ghost king. Dad, I think you'd better call for troops."

Weston's face hardened.

"And be laughed out of any office I visit as a fool-headed, imaginative history bug," he answered bitterly. "No, Helen, it's still our fight. I'm going to get a look at that ship's passenger list. Something is wrong and I'm going to find out what it is."

CAPTAIN Wingate was just coming ashore, when George Weston and

his daughter reached the dock. Weston told Wingate enough of what

was going on to interest him. Captain Wingate was a man who loved

adventure. During the trip down from New York, he had expressed

himself on this subject to me, in the typical Wingate manner.

"Wells," he roared one night, as we sat over a late brandy, "I'm gonna give up this tub one of these days and get into trouble up to my neck."

I laughed at him, trying to picture the rotund little man with the fierce black mustache doing anything but bullying his crew about the deck.

"What kind of trouble would you prefer, Captain?" I asked.

At that, his face had grown a ruddy red. He slammed the empty glass on the table-top and stood up.

"All right, you man-sized bully boy," he threatened. "The next time you get into a brawl, call on Cap'n Wingate. He'll show you who's the right man with knife or pistol!"

So, with my disappearance, Wingate abandoned his former plans, turned the tramp schooner over to the first mate and went ashore with Helen and George Weston. I like to think now that the Captain, for all his shouting, was really worried about my failure to meet Weston. At least, during the next twenty-four hours, Wingate had ample time to prove his sincerity.

I AWAKENED with a terrific pain in my jaw. Gradually, I realized that I had been tossed under a pile of sugar-cane and straw. The floor beneath me was bouncing about. Fully awakened at last, I heard the rough, grating sound of wheels in deep sand. Afraid to betray myself, I searched about under the stuff with a cautious hand. My coat was missing and the gun also. My shirt was torn and I felt sticky moisture on my lips.

Another man lay at my side.

I touched him first with a finger-tip, and the skin of his arm was already cold and growing stiff. It must have been the black who attacked me with the cane-knife. As silently as possible, I explored his body. In one pocket, I found a closed knife. Open, it consisted of a seven-inch blade and as much handle. A valuable weapon. My head must be above the rear wheels. Cautiously, I edged backward.

The wheels stopped rolling. Had we reached the end of the journey? No! A voice sounded above, low and guttural, and the wheels turned again, more slowly than before. Dust filled my nose and I tried to keep from sneezing.

Before the cart had gone ten feet farther, I had dropped to the ground and covered the distance to the thick jungle that bordered the road. It was with great relief that I watched my friend of the scarred chin ride unsuspectingly into the heavy forest that borders Cape Haitian.

My first plan was to follow the cart. To find out where he was taking his cargo of death.

George Weston was waiting for me somewhere in Cape Haitian. Better see him and get a full explanation before riding into this thing blindly. Keeping well out of sight of the road, I started back toward the red roofs of the village.

A closed carriage came from the town and up the long hill toward me. The gray-headed man, who drove, looked familiar. As they drew abreast of me, I stepped from the trees.

"George—George Weston. How about a lift?"

I had meant to sound casual, but my voice must have startled them all. In five minutes, I had told my story and revived our old friendship. Helen Weston was more lovely than ever, with a sweetness that seemed unreal.

"But, why did you go with the man?" Weston asked when I had told my story.

"I guess I'm an eternal damn fool," I admitted. "It looked like trouble and I wanted to get to the reason behind it.

"Well," Captain Wingate said a little sourly, "You're safe now, so I can return to the ship."

"But the fun is only starting," I protested. "Scar Chin will be back. George has a story to tell us and I'd like you to be around."

Wingate flushed with pleasure.

"I'm not really needed," he protested weakly.

Helen Weston looked at the roly-poly captain.

"Oh! But you are, Captain Wingate. Father called Mr. Wells down here because he could trust him. We need every man we can get..."

I DID not hear Wingate's reply. My attention was focused on a

small ox-drawn wagon that moved toward us, going in the opposite

direction.

The others in the carriage had no reason to notice the oxen or the load of cane and straw. They might have noticed the man with the scarred chin, if he had been driving.

On the board that crossed the front of the old conveyance, a black man sat holding his whip as though it were unreal and of no use to him. He paid no heed to us, but went by slowly, his head facing directly ahead.

I was staring straight at the man who had laid at my side in the wagon. The man I had shot in the chest at the waterfront. He could not be alive, yet even as I watched, he lifted his whip, spoke to the oxen, and brought it down smartly on their backs.

"Don't you agree with me Chris?"

"What's that?" I whipped around, perspiration standing on my forehead. Weston was staring at me in bewilderment. "Sorry, I didn't hear..."

"Why, you look as though you'd seen..."

"A ghost," I admitted. "That's exactly what I saw."

I told them about the man on the ox-cart. Wingate exploded.

"Another story to get me away from my ship," he said. "Damn fairy tales. Dead men don't drive oxen."

George Weston had been impressed by my story. For several minutes, we were silent. Wingate showed no anxiety to return to Cape Haitian, and the carriage went steadily forward.

"You'd be surprised," Weston said finally. "Here, dead men do live. Worse than that, they're dangerous!"

A SUDDEN tropical storm whipped across the bay of Cape Haitian, churning the blue waters to muddy froth. It caught us on the road as our horses trotted toward Sans Souci. The palace itself, Christophe's finest, was hidden in a mist of rain. The mid-day storm gave it a sinister, grim look that I had never noticed when I was in Haiti before.

We tied the horses in the open by the dwindling road and followed George Weston up the age-worn steps and across high terraces that lead to the upper stories. He turned once with a smile.

"I am here primarily to study the history of King Henri," he explained. "Sans Souci seemed to be the ideal place."

The palace was in bad condition. The windows and doors were rotted with age. The gaping holes reminded me of the toothless grins of old men.

Yet it was rugged and beautiful. We stopped before a solid oaken door and Weston lifted the heavy ring and drew it open.

There was a small room behind the panel, warm and well furnished.

"This is our home—for the present," Helen said, leading us across the carpeted floor. "We have books for dad and oils for my hobby of painting. A stove and a well-stocked larder take care of our needs."

"Helen will get some food." Weston removed his drenched coat and we followed his example. "After you've eaten, Captain Wingate can take the carriage back to Cape Haitian. We have horses here."

Wingate scowled.

"Who says I'm going back?" he demanded.

"Why—why, I thought..." Weston protested.

It was time that I stepped in to save the poor captain's pride.

"Wingate has decided to stay and help us see this thing through," I explained. "He told me as we came in."

"I said no such..."

The captain started to bluster, hesitated and a broad grin crossed his red face.

"All right," he admitted. "I'm interested in dead men who ride about in broad daylight. The good ship Berwain can go hang for the time being. They'll pick me up on the next trip, if that lousy first mate can steer a course to New York and back."

George Weston had a strange tale to tell. In justice to the man, I can add nothing to what he told us as we sat in the bright light of the gas lantern that black afternoon. The thunder and lightning crashed above our heads and the rain fell in torrents about the dead palace of Christophe.

WESTON started his story over a cup of steaming coffee. The

small room was pleasantly furnished with chairs and a divan. I

confess I watched Helen Weston with renewed interest as she lay

curled like a comfortable doll on the divan. Her lips were

rounded into a small oval and her attention was focused on the

old man.

"We had trouble here," Weston began, "within a week after we came. Liberté, a black boy whom we hired to work with us, told of seeing strange men about the palace. He was never able to show them to us. I obtained permission from government officials to visit Laferrière, King Christophe's citadel."

"That's the fort he built when he was ruling Haiti, isn't it?" Wingate asked. Weston nodded.

"A fort built by dead men," he said. "At least, men who were dead to life as we know it. Every rock of that edifice was dragged into place by hands that dripped blood and minds that refused to function from the pain they underwent.

"From the first, we heard a strange tale that Henri Christophe had returned. I discounted it at first. Then I ran across an old manuscript. It seems that Christophe had pounded the life from his last slave. Mobs of free blacks were about to murder him. He shot himself with a... But wait, I'll show you."

Weston reached into the book-shelf at his elbow and drew down a thin volume. It was mildewed with age and the pages stuck together as he opened it across his knee. He read softly from one of the pages.

"Christophe had one avenue of escape. In the cabinet beside him was a small pearl-handled pistol. He had constructed a bullet of solid gold. The bullet was in the possession of a voodoo priest for many months. With the magic bullet, Christophe shot himself to death before the mob came. He was interned at Laferrière, but it is written that in the gold lay a power that one day would bring life to Christophe and destruction once more to the peoples of Haiti..."

I was greatly impressed by the passage. I took it from Weston's fingers and studied it carefully.

"Written by a French court attaché who was visiting the court here at Sans Souci at the time," Weston explained. "As fantastic as it sounds, King Henri Christophe is alive again. He is building Laferrière mightier than before. Every native in Haiti awaits a summons to death."

"Bah!" Wingate stood up impatiently. "Fairy tale; a damn fairy tale! Can't believe it."

Weston smiled wanly.

"Neither could I," he admitted. "Not until I visited Laferrière."

"Now, don't tell me you've seen the deceased monarch," I begged. "After all, Weston, I came down here to help. I can't start out by believing in ghosts."

Weston's face was white. He gripped the arms of his chair as though afraid of what he was about to say.

"I never reached Laferrière," he confessed. "On the last steep climb to the gate, I heard voices in the opening. From the trees, I watched a strange band of naked black men toiling up the slopes. They were dragging a stone half as big as this room."

He stopped talking, sipped his coffee as though he expected it to help.

"A great hulking brute stood by those men. Every time one of them slackened his grip on the rope, this giant brought a barbed whip down across his back. I stood there for a while and then I turned and ran. I ran nearly every foot of the way back here. When I arrived, Helen tells me I looked more dead than alive."

"But not ghosts," I said. "Surely these men were human— something you could understand."

"The man with the whip," Weston answered haltingly, "was Mano Franca, the same scar-chinned black who tried to kidnap you this afternoon."

AFTER hearing Weston's story of the scar-faced Negro, it was obvious that I would make the trip to Laferrière at the first opportunity. Weston held the position of a sane man attempting to convince others of an insane idea. If what he had seen was an actuality and not a dream, events had taken a serious turn. Many of the natives had disappeared during the past three or four months. More were going nightly.

Into the slave gangs of Henri Christophe? Into a ghost army? Weston said yes. He wanted me to see it with my own eyes. To help him in his one-man crusade against a ghost king.

WE started for Laferrière at sundown. Just before evening, the

storm cleared. The sun came out low and red against the steaming

jungle and sank into blackness. Night birds took up their strange

calls and the palace resounded to ghostly echoes in the open

corridors.

"I hate to take Helen," Weston said, when the horses were saddled. "I have no choice. I can't leave her here alone."

"As though I would even consider it." Helen Weston's eyes were flashing. "I love going along. We'll keep well hidden."

The trail to Laferrière was narrow and well-covered with jungle brush and vines. We were all clad in raincoats and managed to keep fairly dry, despite the water dripping from the foliage overhead.

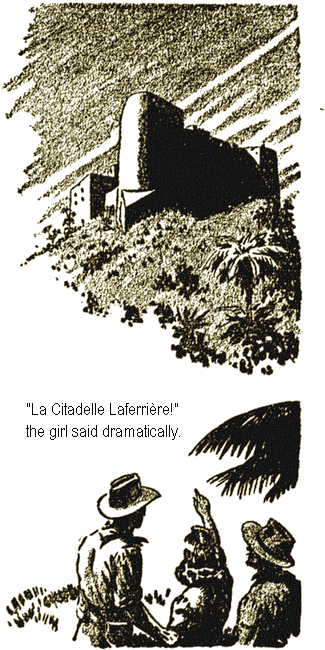

The moon came out presently. A high mountain, jagged and rock- covered reared up ahead of us through the trees.

Weston reined his horse close to mine and we stopped.

"Laferrière," he breathed.

I had seen Christophe's castle before, but at night and with the stories of the afternoon still in my mind, it was awesome.

It swept on upward almost to the clouds above it. Solid, smooth walls towered until my neck was tired from bending upward.

"My God," Wingate breathed. "How did they ever build it?"

"Slaves," Weston answered quietly. "Slaves and blood and death. Now it's happening all over again."

We rode on slowly in single file. Wingate was at the rear and Weston led the way. The girl was behind me on the steep trail. A soft sound came from behind. It was hardly noticeable, but somehow sinister. Swish.

I twisted about in the saddle. Two horses still plodded upward. Wingate and Helen Weston were gone. Gone so completely that no sign of them was visible in the darkness of the jungle.

I shouted to Weston to halt and swung quickly from my horse. Not a moment too soon. A long, vine rope swished down at the place I had occupied in the saddle. Its loop dangled there for an instant and swung up again into the tree. On one knee, I drew the service pistol Weston had given me and fired. No sound came from above. A high pitched scream of terror cut the stillness and its echo pounded back and forth across the wooded slope. I knew it was Helen Weston.

FOR the first time I was aware that Weston himself was in

trouble. He seemed to be threshing about in the undergrowth

ahead. I ran forward in time to see a black bending over him with

a huge club raised to strike. I lifted my gun and fired. The

black gave a howl of pain and toppled back into the brush. Weston

arose. His throat was marked with blue-black streaks where iron

fingers had fastened.

"Helen?" His eyes were terror stricken. "Is she safe?"

I shook my head.

"They got her and Wingate, both. She's still alive. I heard her scream from the slopes above us."

We ran up the trail. I fancied that footsteps in the jungle followed our own. Once I held Weston back, listening. If I were right, our followers were clever. As long as we stood still, no sound came from the jungle. Laferrière was close now. I could see a momentary flash of light against its wall. It seemed as though a door opened and closed quickly at the base of the structure. Then the jungle was silent again and the footsteps that had followed our own were gone.

I believe my shot had frightened the blacks away. Weston was frantic for Helen's safety and I was in no better condition. Carefully, we made our way forward with pistols drawn. It seemed useless to approach such a place without more protection. We had no choice. Wingate and Helen Weston had evidently been carried beyond those walls. We had to find them while there was yet time. God alone knew what tortures were planned for them. Close to the wall of Laferrière now, Weston took my arm and we halted.

"I know of a small entrance on the far side," he whispered tensely. "It opens into the court close to Christophe's tomb. I've used it often to avoid the main gate."

I nodded, released the safety catch on my pistol and followed him along the wall. The valley below was moon-washed and bright. Occasional night birds swished by in the gloom, their bright feathers flashing in the uncertain light. Within Laferrière all was silent. I felt as though we were being watched every moment.

We rounded the last corner and Weston located a small stone door. In its center was an iron ring which he pulled at cautiously. The door, hardly, two feet square, opened easily.

On my knees, I looked through the aperture. Its sides were nearly six feet thick. Inside, the moon flooded a huge empty court. I went through the small tunnel, working my way forward on my stomach. The gun was between my teeth. Weston followed and we stood up. The flooring was worn smooth with many footsteps. A gasp escaped Weston's lips.

"The tomb! Christophe's tomb is gone!"

I HAD never been within the walls of Laferrière, but I realized the implications of his words. Henri Christophe had been buried in the court under a small, roofed tomb. There was no doubt, now, in our minds that he was alive. No such structure broke the smoothness of the court.

"I think the devils must be somewhere within the inner walls," Weston whispered suddenly. "Otherwise we could never have gotten this far safely."

We made our way across the court, staying in the shadows as much as we could. Weston had spent many hours here before the citadel became haunted by the return of its master. Also, with Helen's help, he had mapped every corridor. I stayed close behind him as we entered the first row of gun-chambers which lined the opposite wall.

Every cannon had been pushed carefully into place and beside them cannon balls were neatly stacked for action. The halls were clean and lined with hanging lanterns. This was no fort of the dead. As old as the weapons were, I realized they could hold off anything short of an attack by a well-organized army.

Clang.

The sound of a closing door came from the room below.

"Wait!" Weston stopped short as we drew into one of the small rooms that contained the guns.

"Someone... below."

For a few moments, no further sound troubled the empty halls. Then came the cry of a girl. Helen Weston's voice filled with horror and fear.

"No! Don't leave me! Please."

"The dungeons," Weston said. "This way."

Half running, I went along the hall with him. He stopped before one of the canons leaned against it and the thing moved easily to one side. A black, yawning hole opened beside it. He leaned over the hole, looking downward anxiously.

"Thank God," he said. "This is one of the old passages I discovered. I'm glad they failed to guard it."

I could hear faint voices drifting up from below. Weston dropped into the pit quickly and I heard his footsteps on the stone steps. I followed, paced myself to the uneven steps and hurried into the inkwell he had opened. Ahead, I could hear the heavy, guttural voices. I did not hear Helen Weston again as we went down into the pits below Laferrière.

They had depended on Weston's knowledge to lead him here. Fools that we were, we walked into their trap, baited with our own lives. The stairway ended and we were in a narrow, low tunnel. Water dripped from above and to avoid it, I bowed my head, holding the pistol under my coat.

Weston, frightened for Helen, ran straight into the room before he could determine whether or not it was safe to do so. We must have looked like two silly school boys, suddenly standing there with a small army of wicked-looking blacks on all sides of us. I twisted about suddenly, pistol drawn and then stopped short.

THE chamber was perhaps fifty feet long. More than a hundred

blacks were crowded into it. They lined the walls, knives drawn,

waiting for a command. Then I saw the ghost king of Haiti. Henri

Christophe was standing at the far end of the chamber. He was

dressed in clothing of the Sixteenth-Century French Court. He

looked like a grotesque, punch-drunk prize fighter attending a

fancy dress ball. Silk gloves, knee breeches and silk stockings.

His head protruded from a ruffled collar, his eyes staring at us,

a wide grin on his face.

"Welcome!" His lips were thick and red. "We have just placed our queen on the throne. It is a fitting place for a white woman."

The sneer on his lips told me that Helen Weston was more than a queen. She was a symbol of his hatred for the whites. A symbol that Christophe had dragged here to degrade, that his men could see what happened to the white men and women who defied him.

Helen sat on a huge throne in the shadows beyond Christophe. Her dress was torn and dirty. Her eyes were wide with terror and they held mine beseechingly.

She sat on a throne of human bones. The thing was fashioned cunningly of skulls, ribs and every part of the human skeleton. Helen's wrists were bound firmly to the arms of the chair and the thongs had been drawn through the vacant eye sockets of two human skulls.

The heavy figure of Captain Wingate was stretched on the floor at her feet. His arms and ankles had been bound to stakes in the floor. A wide gash was visible at the hairline of his head. Blood oozed from it freely and the man looked more dead than alive.

"Pinion them to the walls." It was Christophe who spoke.

For an instant I saw red. If we are to die, I thought, then we'll die the hard way. My pistol whipped up until it pointed straight at his head.

"Tell them to stay away," I shouted. "If one man steps forward, I'll shoot."

He seemed taken aback for an instant. Then that same diabolical grin crossed his face.

"You are not aware of my powers," he said silkily. "No gunshot will harm me."

The blacks closed in slowly, waiting for a chance to throw me.

"Don't shoot." It was Weston, pleading.

It was too late. One huge Negro sprang. As he did so, I brought him down with a shot in the belly. Pivoting, I fired three more shots at Henri Christophe. I saw them hit and plow into his shirt. I saw the holes, round and well-defined. Yet, he did not waver.

No blood came from his body. The grin did not change. My arms were pinned back quickly, now, and struggle as I might, I could not throw them off. It was a useless struggle. I could not take my eyes from the ghost king. He stood there quietly, waiting for me to realize the foolishness of my attempt. I saw the man with the scarred chin close in, a heavy club in his hands. His face blotted out the rest of the room. My arms were held tightly behind me. I saw the club descend, shouted an oath of hate into his sweating face; then stars danced evilly through my brain.

THE blacks had left the dungeon finally. Henri Christophe showed no sign of pain at the gunshots I had inflicted. Without further words, Weston and I were thrown on our backs and shackled to iron rings that hung from the wall. The room was silent for what seemed hours. Helen Weston told her father how they had been dragged here and used as bait to capture us. She managed to keep her nerve now that we were with her. Time dragged on and no one came to see that I was alive.

Then we were troubled by what sounded like approaching footsteps beyond the wall of the dungeon. A section of stonework came away slowly and an old woman came into the cell. She stood alone at the far end of the room. Her body was swathed in foul, gray cloth. She appeared to be ageless, with dried skin and long witch-like fingers. When she opened her mouth to speak, her gums were gray and toothless. The voice, however, was kindly.

"You must all be quiet," she said commandingly. "I will take those whom I am able to free."

"Who are you?" Helen demanded, as the old woman approached her.

The visitor worked over Helen's bonds, freeing her wordlessly. Then, as she freed Wingate and helped him to his feet, she said:

"It is of no importance. I am nameless now." Then, turning to Weston, "I cannot free you or the other of your chains. I will lead your daughter and this fat one to safety. It will be up to them to return for you."

Captain Wingate rebelled at this. He tried desperately to free us both. At last, sweating at the heavy rings that were buried in the wall he gave up.

"I'll get to my ship," he told Weston. "They won't sail before tonight. We've been carrying three Browning machine guns since the war broke out. I'll get the crew and those guns. We'll come back and blow this damned death house off the map."

Helen had been binding the wound on my head. She finished, kissed her father and then turning to me, leaned over and kissed me on the cheek. I'm afraid I blushed a little.

I struggled up to a sitting position. "I'm glad they got out of this mess." I said. "I wonder where the old woman took them."

Weston shook his head.

"I have only one solution. Henri Christophe had a tunnel dug from here to Sans Souci. He murdered everyone who worked on it, so that the secret would remain his own. He evidently had no fear of our locating it. The thing isn't shown on any of the maps."

"Then the woman? How could she know of it?"

Weston shook his head slowly.

"I can only answer riddles with riddles," he said slowly. "How did she know of us? Why should she take the chance to come to our rescue when we don't even know her?"

My head felt better under the tight bandage. I thought of Helen and the kiss she had given me. Weston seemed to read my thoughts.

"Helen thinks a lot of you, Chris," he said.

Footsteps sounded in the hall leading to our prison.

Weston said shortly, "Wait until they discover Helen and Wingate are missing."

I WATCHED the small door that lead from the dungeon. The lower

portion of a black man became visible and he bent his shoulders

to enter the door. It was the man with the scarred chin, Mano

Franca. His features were contorted with anger and his eyes

widened until the whites of them showed. He looked around the

room quickly. Then he ran swiftly toward me, put his hands under

my armpits and dragged me upright. His teeth were yellow and

clenched.

"The woman," he snarled. "The woman and the fat one. Where are they?"

I shrugged my shoulders and he dropped me rudely to the floor. I swore under my breath at the chains that kept me from resisting. He repeated his question to Weston, shaking the old man violently. Weston didn't trouble himself to answer. Mano Franca was violently angry, and yet puzzled. It was clear that he knew of no opening to the dungeon other than the one through which he had come. I believe that a strange superstitious fear swept through him at that moment. A fear that lay dormant in the hearts of all the blacks. He turned on his heel and dashed from the dungeon. His voice, thick and guttural, drifted back as he retreated down the tunnel.

"Now we're in for it," Weston groaned. "He'll be back with the whole mob of them."

"I wish I could get one arm loose." I tried to jerk free the ring that held my right wrist to the wall. It was useless. The chains were heavy and one link was buried deep in granite. Many voices sounded in the tunnel. I recognized the anxious, hurried voice of the scar-chinned black and the heavy, measured tone of Henri Christophe. They came in quickly, and Christophe stood alone at the door while four of his men went quickly about the room.

One man, and one alone, knew how Wingate had escaped. Henri Christophe stood quietly, his huge body tense. His eyes were not on us, but on the section of wall through which the two missing prisoners had escaped. Slowly, the monarch's eyes swept around and stopped on mine. They were black as night, boring straight into me. He seemed to be saying:

"You know the secret of the tunnel, but it will do you no good."

He shouted something to his men in a strange, primitive language I did not understand and they retreated to the tunnel behind him. Mano Franca went last, seemingly reluctant to miss this chance to inflict further torture on our already exhausted bodies.

SOON we were alone with the ghost king, Henri Christophe. He

walked across the cell deliberately, raised the heavy riding crop

in his thick hand and brought it down sharply across my face. If

I had been free at that moment, I would have torn that arm from

its shoulder. My whole body burned with pain and hatred of

him.

"Who helped the white ones to escape?" His voice was harsh and cold. "Tell me, before I beat the words from you!"

Weston raised himself against the wall, trying to stand upright under the weight of the chains.

"You're bluffing," he said slowly. "We won't tell you a thing. They'll be back with troops soon. You'll regret every minute you've kept us prisoners here."

Christophe's whole body straightened and swelled with pride. He turned toward Weston.

"All the troops in Haiti could not drive me from Laferrière," he roared. "I am King of Haiti. Do you understand? I am ruler of all I survey from the towers of this place. No man can take from me what I have."

I guess at that moment I believed him. I believed that Henri Christophe was strong enough to carry out his boast. The only safety we had now was to frighten him in some manner. To make him think that immense armies would come here to attack him.

"You are not afraid of the United States Army?" I asked with as much sarcasm as I could muster.

He hesitated in his reply and then a broad grin covered his thick face.

"I am not afraid of God or the United States Army," he answered. "And I am even less afraid that such an army will march against our tiny republic when world matters are so threatening."

So that was it! The man must have known. Must have been able to control his own return to the world, to place himself in Haiti when world problems were all important. I decided to go on talking. To stall until Wingate and the girl had time to do something for us. But Christophe was not in a listening mood. He strode quickly toward the door and his voice roared up the passage.

"Franca! The chains! Throw these men into the slave gang."

Mano Franca must have been waiting close by. He entered the cell like a panther, and in his arms he carried two lengths of heavy chains. My arms were jerked upward rudely and released. In three minutes Weston and myself were standing in the center of the cell, both our legs bound in short lengths of heavy metal. I could take only short steps or find myself tripped and sprawling full length on the floor.

"March!"

We had been stripped to the waist and the quick flexing of Christophe's heavy arm brought the leather strap down across my bare shoulders. We went up the tunnel slowly and into the open air of the court. It was daylight now, and the activity within Laferrière had been increased tenfold. The court itself was perhaps five hundred feet square. Above us were other open spots, built atop the wide walls. Everywhere slaves toiled in chains like the ones we wore. They were, for the most part, clean smooth-skinned blacks brought from the sugar plantations around Haiti. Their faces wore set expressions and their bodies moved as puppets. At the sight of Christophe and Mano Franca, they increased their speed.

GREAT guns had been rolled into place at the slits of the

walls. Cannon-balls were stacked neatly in pyramids along the gun

embrasures. The place was as neat and well-cleaned as the deck of

a battle ship.

"Take them to the valley and put them into the line of builders." Henri Christophe dismissed us with a curt nod of his head.

Weston leaned close to me.

"Keep your chin up," he whispered. "We're in for it. They'll make us haul rocks up the hill to rebuild the walls."

The scar-chinned Franca silenced him with a well-placed blow of the whip and we both stood with bowed heads. It was useless to fight now. Perhaps later we'd have our chance.

With a number of slaves that Franca collected hurriedly from court, we were driven like animals toward the heavy door of the fort. The doors swung open and the green, sun-flooded valley was visible below.

"March!"

A heavy crack of the whip sent me reeling forward through the gate. Franca was close behind. When he brought that thing down again, I could grab the end of it and upset him quickly.

"Easy." Weston had divined my thoughts. "You can do nothing yet. We'll have our chance."

The whip descended again, cracking around my bare waist. That wickedly-scarred chin was due for some punishment before I was through. Mano Franca would have to whip hard and watch me closely, I decided. I'd pay him back, with interest, when Wingate returned.

IT was to be some time before Helen Weston and the ruddy-faced Wingate would be of further help to us. They had gone through the secret tunnel quickly, feeling their way in the inky blackness. Once Wingate stopped Helen by placing a thick hand on her arm. The old woman who led them was already several yards ahead in the musty crypt.

"Keep your eyes open," he whispered hoarsely. "God knows what this old dame is up to. She may murder us both before we get out of here."

Notwithstanding Wingate's warning, Helen trusted the one who guided them. Her trust was well-placed. They reached the blank end of the tunnel and the woman fumbled against the wall ahead of them. A hidden mechanism started to purr within the wall and daylight flooded the place. They were in the halls of Sans Souci.

"Jerusalem!" Wingate said. "Right back where we started from."

The woman went ahead of them and stood in the huge hall of the palace. They studied her carefully now, with the light full on her features. She seemed almost ageless, her face skinny and the bones of her elbows sticking out, taut and brown under her skin. Her lips were purple and cracked and the smile she gave them was almost a grimace.

"You are safe now," she said, her voice like a cracked record. "Go to Cape Haitian at once and tell the whites there to leave Haiti. They will all die unless you do this."

Helen Weston was a clever girl. She knew that this woman was playing for higher stakes than seemed evident at first glance. She wanted to make friends with her.

"Why do you say this?" she asked kindly. "You have a reason for freeing us, for giving us this warning."

The three of them were standing in a small group under the broken roof of a wild and desolate jungle palace. The sun streamed downward. A brightly colored cockatoo spread its feathers in the sun to dry. Wingate confessed that he wanted to leave without further talking. He felt safer with a gun or a knife to fight with. He had nothing. The woman hesitated before she attempted to answer Helen Weston. At last, she turned and walked swiftly from them. They followed, and as she walked, her voice drifted back.

"Christophe has returned to rule Haiti. Before a week is gone, the blacks will rise and kill every white man, woman or child on the island. By the time this has been done, Christophe will be safe from any assault. You cannot save the two you left behind. It is better that you leave before it is too late."

They reached the outer door to the great room. Before them, Wingate recognized the road, our carriage still tied beside it.

Taking Helen's arm, he drew her down the wide steps.

"Better keep our plans to ourselves," he said quietly. "She may not be so friendly if we don't agree with her."

Helen nodded. She turned toward the old woman who had stopped at the top of the steps.

"We thank you for helping us," she said. "We hope you will not suffer. If you need us again..."

The woman grinned. Her mouth was defiant and a thin cackle came from between her toothless gums.

"Never fear," she answered, "Henri Christophe cannot harm me."

She turned and disappeared into the palace. Wingate turned toward the carriage and a shiver played up and down his back.

"Let's get out of the cursed place," he said. "This is something we can't fight alone."

ON their quick ride down to Cape Haitian, they planned their

strategy for action.

"I've got eighteen men in my crew," Wingate explained as the horses trotted along the sandy road. "Three Brownings should cause a lot of trouble if we can once get inside the wall of Laferrière."

Helen protested.

"But three guns against how many hundreds? I think that half the population is ready to fight for this ghost king."

Wingate nodded his head grimly.

"I know," he agreed. "There are no American troops stationed here since the marines left. The American consul would laugh at our story. We dare not go to the Gendarmerie. They may be mixed up in this mess on Christophe's side."

They were silent after that. The sun moved higher into the cloudless sky and the bay of Cape Haitian became visible, a huge half circle of blue at the foot of the hill down which they rode.

Wingate's ship still rode at anchor in the bay. Within an hour he had his plan before the crew. They were ready and anxious to escape the routine of ship life. A good fight sounded welcome to them.

Under the cover of night, Wingate, Helen Weston, the crew and three gleaming machine guns went ashore in the ship's boats. They climbed into waiting carriages and went swiftly along the road toward the citadel of Laferrière.

THAT day in chains was intolerable for me, and much worse, I'm afraid, for poor Weston. The sun set quickly in a great red ball over our shoulders. We had toiled upward hour after hour, a hundred sweating men, with ropes tied around our waists. Behind us, like a wheelless juggernaut, a granite boulder inched upward under our combined strength. Every man who hesitated received three lashes across the face and body. The scarred chin of Mano Franca quivered in delight as he administered this punishment.

We were close to the gate now, and it was already dark. Weston was toiling close to my side, great beads of sweat standing out on his body. He had raw, deep gashes where the whip had paid special attention to his tender white skin.

"We've got to do something fast," I whispered, hoping Franca was far enough away that my voice would escape his attention. "Once inside the wall and we have to go through another day of this."

Weston nodded slightly. He was either too tired or too weak to reply.

"The boulder," I whispered again. "If we were able to release our weight and trip a couple of the men. It might roll backward."

Weston's eyes widened as he turned to me.

"But in these chains..." He stopped abruptly. The scar red- chin black was close to us.

The slaves were humming softly behind us. It was a low, wild chant of fear and hate. I would go crazy facing this any longer. Mano Franca passed behind us and down the line.

"Pull as hard as you can," I told Weston. "Then, when I touch your arm in the darkness, throw yourself back with all your strength against the man behind."

I knew from the way he nodded that he felt we had little chance to escape. We were at the gate now. It was pitch black outside. A few lanterns hung from the wall above. Every man in the double line of blacks was straining those last feet. Weston and I were placed at the lead of each line. Franca was far down the hill, urging the stragglers with his great whip.

"Now!" I shouted and released my weight from the pull rope. I tackled the man behind me with all the force I could muster. I knew that Weston was doing likewise. High-pitched screams of fear arose. The slaves were going down like tenpins under the force of the weight and the lack of pull from above. Franca's great voice boomed out in anger and the whip renewed its fury.

Now was our chance. The dark ground was covered with the bodies. They rolled backward, pulling me with them. The boulder lost its stolid hold on the earth and plowed backward. With feverish fingers, I jerked the rope from my waist and was free. Weston was already at my side. I started running toward the jungle that bordered the path. The chains between my ankles tripped me and I fell headlong among the creepers. Weston was beside me, helping me to my feet.

"We've got to go cautiously," he urged. "I know a way. Follow me but try not to fall again."

A CRY of anger drifted up from behind. The boulder had rolled

downward, dragging some of the men to their deaths. Others were

behind us, rushing in all directions through the jungle. A gun-

shot cracked out; a long moment of hesitation, and then another.

Thank God that the weapons they used were a hundred years old. It

took time to load them and they were little better than pea-

shooters in the thick gloom.

We were going more slowly now. I found that I could hop along a foot at a time and remain upright. Weston was ahead, moving deliberately into the thickest creepers. The sounds behind grew fainter and died in the night. At last, he stopped.

"In an hour they'll have a searching-party after us." He sat down on a rotted section of mahogany log. "We've got to find the road and stay close to it. We can't fight until we rid ourselves of these shackles."

I nodded, saving my voice and we went onward. Several times, we fell forward, face down in the slime and mud of the lower valley. At last we came out on the road to Cape Haitian and Weston held up a cautioning arm.

"Wait," he said. "Something's coming toward us..."

We stood in the brush close to the sandy strip. Three carriages came along the sand without lights. They were close before I saw the round-faced Wingate riding astride one of the horses on the lead carriage.

"Cap'n," I shouted and—forgetting my chains—tried to run into the road before him. "It's Wells! Weston and I escaped."

Those infernal chains tripped me and I fell head-first into the dust as the first carriage stopped. Wingate dropped from his mount and came to my rescue. Soon the entire group of men were about us.

"Oh Dad! Dad!" Helen Weston ran toward us from the last coach. Her arms swept about her father. "I'm so glad you're free." She saw for the first time that the skin of his back and shoulders was cut and torn.

"Those devils! Those—those..."

"There, there." Weston patted her awkwardly as she burst into tears. She dried her eyes quickly and came to me.

"Chris, are you all right?"

It was the first time she had called me by my first name. I was suddenly proud and felt much better than I had for a long time.

I took her hand and clasped it tightly.

"Fine," I agreed. "But I'd like to get these chains off."

Wingate whispered to one of his men who then went back to the carriage.

"We have files," the Captain explained. "Thought I'd bring them along. I remembered those chains in the cell."

IN ten minutes we were free of our bonds. With my back treated

and a shirt once more across my shoulders, I felt much

better.

"And now," Wingate said, "we'll go back and clean up on the little self-made God. I'll venture his skin will feel the sting of our little hornets."

He patted the shining barrel of a Browning that lay across the seat in front of us.

While we rode, Wingate told us of the old woman who had freed them.

"And she's right, too," Helen chimed in. "Cape Haitian is strangely quiet. We saw no one in the streets. Everyone seems to expect something terrible to happen. I believe this strange man Christophe holds a spell over them."

Wingate grunted.

"Spell, my eye," he protested. "He's got nothing a few well-placed tracer bullets won't stop."

Weston had been silent all this time. We were close to the trail that left the main road to Laferrière when he looked up suddenly, a strange fear in his eyes.

"Wingate," he said, "I don't know exactly how to explain this. Henri Christophe is more than a man. Don't ask me how, but I think he has made of himself something that cannot be destroyed. Something that has thrown a fear into every black body on this island. I'm not so sure that your machine guns can destroy that."

I knew that Weston was choosing his words carefully. He was trying to tell the Captain that something that could not be destroyed was ahead of them. Wingate was impatient and angry at this seemingly outlawish attitude.

His mustache quivered a bit under his retort.

"Coming down from Florida," he said firmly, "we knocked three enemy planes out of the sky with those guns. My men have fought off a sub crew with side-arms and their bare hands. We'll take our fighting as it comes."

"I know, but this is..."

Wingate jerked at the reins of his horses and the carriage halted.

"You're going to tell me this is different," he said. "Now I'll tell you what I think. This—this ghost king you're afraid of isn't any more ghost than I am. He's got a lot of old cannons and he dresses up to scare hell out of these black- hearted savages. I'll make him walk the plank of his own danged fort before we're through with him. If you don't want to fight with us..."

Weston shook his head.

"I'm sorry, Captain," he said in a low voice. "You're a fighting man and I'm proud to be with you. Let's get on with it."

DURING their conversation, I had been doing some thinking. It was useless to tell Wingate that I agreed with Weston. The small, gray-haired professor had been taught in the best schools of the world. He had imagination and an ability to balance it with good judgment. I was convinced that he was right. That Christophe was returned from the dead. I had proven that when I tried to destroy him in the cell. His flesh had been unharmed by the lead from my gun. More than that, I had shot a man in Cape Haitian. Later, that same man had driven calmly past me on the way back to town.

"Wingate," I said suddenly. "What do you plan to do once we reach Laferrière? Somehow, we have to get that gate open."

The carriages had stopped. We were at the end of the road. From here on, it would be a sharp, creeper-choked climb to the base of the fort itself.

"We'll storm the gate with a log," Wingate said. "Three men will cover our assault with the guns."

The men were out of the carriages, murmuring among themselves.

"I'd like to make a suggestion," I said.

Wingate nodded.

"It may mean a number of deaths if you go into the open. You're expected back, depend on that. Christophe will have his men placed at points atop the walls where they can subject us to a withering fire, yet remain out of reach of our guns."

Wingate seemed to think that over. The men were crowded about us on the road. The moon was high, now.

"You may be right," Wingate agreed. "What do you suggest, Wells?"

"Give me one of the guns," I said. "I'll manage to get it up alone and, with a length of rope, I'll have everything I need. You make a lot of noise in the jungle around the main gate. Meanwhile, I'll find a hidden spot, throw the rope over the wall where it's lowest and climb it. I'll tie the gun to the bottom of the rope and draw it after me once I'm inside. From the wall, I can rake the inner court with fire while you storm the gate."

I could see that Wingate was impressed.

"All right," he agreed. "I'll send a man with you."

"No. The gun's heavy, but I'll manage. I'd rather do this my own way."

Helen Weston walked toward me.

"I'm going with you," she said calmly.

In the brief instant that our eyes met, I know I wouldn't have it any other way. Funny how it breaks on you like that, with one silent, heart-touching look into deep eyes. If I left her with the men, God knows what might happen when they ran for the gate. Yes—she would be safer with me.

"Good," I agreed, and I knew she understood why I had not hesitated. I was never good at putting words together.

Our plans made, we worked swiftly.

WESTON took nine men and one of the guns and went up the main

path toward the gate. Wingate followed with the remainder of the

crew. They separated, should an attacking party meet them on the

trail. Most of the men were armed with pistols. Helen insisted on

carrying the heavy coil of rope and together we struck off at a

tangent toward the side wall of Laferrière.

In twenty minutes, we had reached a niche in the wall, perhaps sixty yards from the gate. I knew that Weston and Wingate were thus far safe. No guns had been fired.

Wordlessly, we studied the wall above. It was studded with protruding boulders. At last, I found one close to the top that furnished a two foot jagged edge over which the rope could be tossed. I took the rope from Helen and tied one end of it carefully around the tripod of the gun. The belt of cartridges was in place. All was ready. I threw a loop of rope upward. It hit the rock and slipped away, falling around me. I tried again. This time it caught. A few sharp tugs convinced me it was caught securely.

Helen stood close to my side. I turned to her and saw that strange look in her eyes once more.

"Stay in the forest close to the wall," I whispered. "You'll be safe there. When it's over, I'll come back."

She said nothing, but her face was lifted to mine, tears glistening in her eyes. I felt a choking, helpless feeling in my throat. Bending quickly, I kissed her lips. Her response was immediate. We stood quietly, our arms about each other, then I pushed her away determinedly and reached for the rope.

A strange hush had fallen over the forest. It was as though a thousand eyes were upon me. As though the world was waiting for me to climb that rope to the wall above.

"In the jungle," I said once more. "Don't try to join the others or to run. You'll be where they can't find you."

She nodded and I swung upward, hand over hand. It was an easy task. I had climbed many a ship's rope in my day. The rocks scraped my body as I went upward, but the still air, the feeling of being free and ready to fight once more was wonderful. I stopped once, swaying back and forth in mid-air. Soft footsteps told me that Helen was leaving the wall. Upward again, my fingers closed over the top and I drew myself onto it. Not a sign of life marred the place. Then, like a crack of a cannon, the sound of a single pistol shot rocketed upward and re-echoed through the darkness. I crouched there, waiting.

Crack—crack—crack!

IN quick succession, three shots followed the first. A single

cry of pain sounded near the gate. Yet, strain my eyes as I

might, nothing was visible in the blackness. Feverishly, I

started to pull the gun upward. In my desperate attempt to be

ready for what came, my strength was twofold. The gun came much

more easily than I had expected. It vibrated and scraped against

the wall in the pitch blackness below me. My arms ached, but I

drew it upward steadily, hand over hand. No more shots sounded. I

still saw nothing move within or outside the citadel. I had a

coil of rope at my feet now.

A shock of horror raced through my body as the first knot came into view. Feverishly, I drew the burden at the end of the rope over the edge of rock.

It was no gun that I had scraped and hauled up the stones of Laferrière. Helen Weston, her mouth silenced by a gag, lay on the rock before me! Her body was still and her face was bloodless. Her wide eyes stared up into mine with the fear of death in them.

I was still bending over her, struggling to release the gag when harsh grating footsteps rang out behind me on the wall. I tried to spring upright, at the same time half freeing my pistol from the holster. My eyes swept up two lean, muscled legs and succeeded in reaching only the knees. Something broad and heavy struck my head a terrific blow and a wave of sickness swept over me. I felt Helen, soft and yielding, as I pitched forward on top of her. My head felt as though it had been split open with the force...

"OLD home week, I call it."

I opened my eyes slowly and was again aware of the intense pain that seemed to sweep wave upon wave across the top of my head and down my neck. I recognized the voice I had heard as Wingate's. We were once more in the cell. The room under Laferrière. I forced my eyes open and tried to put a hand to my forehead. Both were chained securely to the wall.

"He's coming around," Weston's voice was clear to my ears.

I struggled to place my back against the wall where I had been lying and pushed myself upright. My head was clearer now but the intense pain remained. Wingate and Weston were both here. Both chained against the wall where they had been a few hours ago.

Wingate started to talk in low tones.

"It was them damned savages," he said bitterly. "They attacked us in the jungle. Killed every man with their sugar-knives. We didn't have a chance."

I remembered the still figure of Helen Weston lying before me on the wall.

"Helen?" I cried. "Did you see her? Is she safe?"

"Good Lord!" It was Weston. "Didn't you hide her?"

I told them quickly what had happened. When I finished, Wingate shook his head.

"Then she's within the citadel somewhere," he said. "We were surprised at the gate. We never saw you at all. They must have played some sort of a grisly joke on you by substituting her for the gun."

"I was an awful fool," Wingate said in a subdued voice. "If I hadn't been so sure of myself..."

Weston interrupted him.

"Forget it, Captain," he said. "You've been a real help all along. Without you, we'd stand no chance at all. As it is, we all have a chance to escape."

HALF an hour dragged by without our hearing from our captors.

Sounds drifted down occasionally from the halls above us and

there seemed to be something astir within the citadel. The heavy

rumbling of what I took to be cannon, occasionally broke the

silence. Here was activity beyond anything I had yet seen.

Henri Christophe came himself to the cell. I am forced to say that in spite of my personal opinion of this man—or ghost, whichever he may have been—I did admire his splendid physique. Each time he appeared before us, there was no hint of doubt in himself.

Here was a giant black man, heavy with muscle and handsome as a barbaric cannibal. He wore the finest silk clothing. As he stood in the center of the room, looking at us with those deep black orbs, his shoulders were held high with purpose and his voice never lost its complete control of the situation.

"So you have come back to us," he said.

There was no answer. He expected none.

"You no doubt wonder what has happened to the white woman?"

"She is safe?" I asked aloud.

A suggestion of a sneer crossed his face.

"Only so long as you make no attempt to hinder me further," he answered.

Weston opened his mouth as though to speak, thought better of it and remained silent. It was evident that Christophe's interest, at least for the time being, lay in me.

"You are returning to my chambers with me," he said.

He released my chains and, rubbing the blood back into stiff wrists, I arose and went toward the door. Christophe came behind me, a wide-bladed knife swinging idly at his side.

We went up into the open court.

It was empty. We crossed it quickly and entered a small door on the opposite side. Inside, it was dark, but I felt my way forward and up a long flight of steps. I found myself on an upper balcony. A low wall ran across one side. All this time, my host had not spoken. Perhaps it was the clear, heady air that stirred him to almost pleasant conversation. Or perhaps he wished only to taunt us.

"I suppose you wonder greatly about my presence here?" he asked suddenly.

I turned, somewhat surprised, to find that he had pushed the knife into his belt and was standing with arms akimbo, a grin on his face.

"I—I don't understand it all, if you'll have the truth," I admitted.

He chuckled.

"Don't worry your puny brain," he urged. "Sufficient to say, I am soon to rule this land with my hand and mine alone. There will be no place for men who think for themselves."

I admired certain qualities in this black giant, just as any man admires a worthy opponent.

"But Haiti," I protested. "Surely men here were doing well. They care for themselves. They function well with their present governing body."

"Bah!" His face expressed disgust. "These natives are but slaves. They are fit only to obey. They do not think for themselves."

He walked quickly to the wall that surrounded the edge of the fort and motioned for me to stand at his side. I joined him reluctantly, and he pointed out across the jungle.

"This is my land." He spoke with great emotion. "Many years ago I ruled all this. At last, because foreign powers meddled, I was forced to leave to avoid assassination. You have read that I shot myself rather than face death at the hands of my people?"

I nodded, wondering why he told me this.

"Do I look like one who is afraid to die?"

He faced me directly, his face close to mine. He seemed anxious that I understand him.

"No," I admitted. "On the contrary, you seem quite fearless."

He relaxed, leaned on the wall and stared again into the darkness.

"My people laughed when they found I had shot myself. They did not know that in that yellow bullet was the secret that would make possible my return here."

"So that was it," I thought. "The golden bullet of Henri Christophe."*

[* Henri Christophe ruled Haiti as "King"—a black emperor, crowned by a French bishop on June 2, 1811. The man seemed to be a weird combination of sanity and madness. He built Laferrière with the backs and hands of slaves. He compelled every grown man and woman to work fourteen hours a day. Haiti became rich and its wealth was Christophe's. Ships of all nations came to Haiti. Scholars and diplomats followed until men of every nation paid homage at the court of the King.

Every morning he rode the countryside, carrying a telescope. There was no hope for the unfortunate Haitian who was idle when Christophe's eye fell upon him. The King ruled with fear, and on the highest mountain he built his monument to fear—Laferrière. Built it with the blood and sweat of his people.

Tens of thousands of men died to build that fort of horror. Three hundred and fifty cannons were dragged up the slopes by human animals. Barbed whips sent them ahead when they thought they could go no farther.

The citadel was finished but it was separated by miles from Sans Souci, his palace. Two men knew the secret of the tunnel. Christophe was one of them. The other, a mulatto engineer, died on the rocks below the castle wall.

Henri Christophe lived a haughty, proud life until revolt overthrew his kingdom. Of his death, it has been said, "He had, in his bedroom, a cabinet in which there lay a gold-chased pistol with a golden bullet. He pushed the bullet into the barrel carefully and primed the pistol.

"Hordes were already in the palace. A shot rang out in the King's room. They found him lying on the floor, a scarlet stain marring the white silk of his night-shirt."—Ed.]

HOPING to learn more, I said aloud: "But I don't understand. If you were dead, how..."

He looked thoughtful.

"Why I tell you this, I do not know," he confessed. "I suppose that, although I am ready to kill men who think for themselves it is refreshing to have one near me who understands my greatness.

"I did not die! One person alone knew the truth. She was a priestess who cast a spell on the golden bullet. It was she who saw that my body, with life suspended within it, was carefully placed in the vault here at Laferrière. I need only remain there until my will was strong enough to break away. It happened a short time ago. Now I am free again, to live as I did before."

"And you expect me to believe this nonsense?" I did believe, but somehow I felt that to keep him talking would delay my own fate at least by minutes. Oddly, enough, he did not seem angry.

"What I tell you is the truth," he said slowly. "Except that this time, now that I am alive, I will remain so forever. No power of man can destroy me."

He left the wall and strode across the small court into one of the many halls. I followed, knowing it was expected of me. It would do no good to attempt escape now. Helen's life depended on my doing, at least for the present, exactly what Christophe asked of me.

There were lights ahead of us, and as we entered the room at the end of the hall, I became aware of a difference in the atmosphere. It was a large, well-furnished chamber about forty feet square. Rich rugs covered the floor. The walls were lined with books and a number of early French chairs were placed about the room. Two people were here. The scar-chinned Mano Franca sat on his haunches near the far end of the room. A delighted grin covered his face. He was staring upward at Helen Weston, who sat by herself in one corner.

"A watch-dog who knows but one master," Christophe said. "You see, the woman is safe, thus far."

As we entered, Helen arose and came toward me. Her face was very white, but otherwise she seemed well.

"Dad?" she asked anxiously. "Is he all right? Where is he?"

I took her small hands in my own.

"Both he and Wingate are safe," I answered.

"You know that the girl is safe." Christophe said. "She will remain safe if you and I can reach an agreement."

"You're doing the talking," I answered.

"Very well!" He crossed to a divan and sat down. "I need those guns you brought here."

"I imagine you've got them," I answered.

Christophe nodded.

"You are correct," he agreed. "But they are useless until I learn how they are fired."

HERE was my chance. If I could get close enough to turn one of

the Brownings on his men, we might still win out.

"If you are thinking of destroying us with the weapons, dismiss the thought," he said calmly. "I am ready to give you all a chance to live—and no more."

I motioned for Helen to sit down and took my place at her side. The hulking Franca arose from the floor and knelt on the carpet close to Christophe. I held Helen's hand tightly in my own and squeezed her fingers.

"Go on," I urged.

"I have seen your mechanical guns working at Cape Haitian," Henri said abruptly. "In one day I will send my soldiers forth to bring back slaves. They will murder the small population of whites on the island and will frighten the remainder of the inhabitants in a manner that will place them all under my control. Those guns would help a great deal in doing it. I ask you, in exchange for your freedom, to show us how to use the mechanical guns."

"We will all be set free?"

He nodded.

"The four of you will go at once. You will sail in your Captain's ship and escape the fate of the other white inhabitants."

I admit for a moment it seemed an attractive offer. After all, it was up to the others to take care of themselves. Then I realized that it was not the freedom for myself that I wanted. It was safety for Helen Weston and the two men locked in the cell below. They would never forgive me if I sold out now.

"And if I refuse to help you?" I asked.

Mano Franca drew his huge knife from his belt and ran a thick finger down the blade. He was grinning directly at me.

"Men die many ways in Laferrière," Christophe said slowly. "It will not be hard to dispose of you all."

Every man has a weak spot in his armor, I said to myself. Four of us are at his mercy. No help will come from outside. Somewhere, somehow he can be outwitted. Agree with him now and watch your step.

"All right," I said. "I will show you how to fire and care for the guns. As soon as I have finished, you will see that we all manage to reach Cape Haitian safely?"

Henri Christophe stood up and nodded approvingly.

"That is good," he said. "I have no quarrel with you. To be rid of you in any manner will be welcome. But I must have your promise that you will not return to the island of Haiti after you leave."

"After we leave Cape Haitian," I said deliberately, "I and the others will not return again."

"But before I go," I added to myself, "there are a few scores to be evened up."

"BUT we are helpless," Wingate protested.

I had been returned to the cell to await morning. I told the two men what had transpired in the lounge of Henri Christophe and how we figured in it.

"I'll think of something," I said in answer to Wingate.

"And you say that, for the time being, Helen is safe?" Weston asked.

I nodded.

"Christophe is, in many ways, almost human," I told them. "He has an overrated opinion of himself, but he won't break his promise until he learns how to use those guns."

"And afterward he'll throw us all over the walls," Weston added. "I, for one, am in favor of telling him nothing."

Finally, with nothing to be gained until the following morning, we slept. It may have been minutes or hours before I awakened. At least, the steady darkness of the cell remained the same. At first, I wasn't aware of what had caused me to sit suddenly upright, my eyes staring into the gloom. Gradually, I made out the sprawled figures of Wingate and Weston sleeping on the floor across from me. There was someone coming toward me from the far end of the room.

"Do not cry out." The voice was dry and thin. "If I am found here, it will mean my death."

The voice was that of an old woman. As she came closer, I made out the gray cloth that covered her from head to foot, the thin parchment-like face. This, then, was the old crone who had helped Helen and Wingate escape-once before. Then full realization broke over me.

Henri Christophe had said that he alone knew of the tunnel to Sans Souci. One person had remained alive after he had died from the golden bullet. This, then, was the priestess who had placed the charm on the golden bullet. The one who had cared for Henri Christophe's body until he returned to life.

I waited silently until she stood over me. Her face was not unkind. In fact, I could find no expression whatsoever in it. She stood silently, listening, her body tense and straight.

"The others must remain asleep," she said at length. "You alone can do the task."

She leaned over me, produced a set of rusty keys and released my wrist from the metal rings.

"Arise quickly, and follow me."

"Thanks," I whispered, and stood up.

I STAGGERED for a moment, caught myself and saw that she was

already across the room. We followed the tunnel upward and I was

somewhat surprised that instead of leaving Laferrière by the

secret entrance, she went directly up the steps toward the court.

Once we stopped, heard heavy footsteps pass above, and went on

again quickly. At last, in a small hallway close to the court,

she stopped. I felt her skinny old hand on my own as she drew me

back into the darkness.

"Henri Christophe must die."

I confess a chill ran through me at the harshness of her voice.

"But—I don't understand."

"You will," she said. "Listen and mark my words well. Who I am matters not. Sufficient to say that many years ago I loved Henri Christophe. His heart was not for me. I watched over him through life and I stood alone with him when he died. I knew that destiny should give him a second chance at his star. I gathered a bit of precious metal and caused it to take on unique powers."

"The golden bullet," I breathed.

"The golden bullet," she repeated.

"Henri arose again as I had made sure he would. Now, as time passed, I realized I had made a mistake. Henri Christophe should not have the power that has been given to him. I am too old to make him look at me. He, strutting in his rebirth of youth and power, will look upon women much younger, while I suffer for the act I have committed."

Standing there in the darkness, I could realize some of the torture that filled the old woman. She was forced to stand by while an object of her own creation, a zombie of the dead, arose from under her spell and, ignoring her, made his own selfish place in this world of hell.

"But," I asked, "what can I do?"

"Is that not evident?" she asked. "What gold has built, gold can destroy."

I had never thought of that. Henri Christophe had been immune to the usual instruments of death. Lead failed to harm him.

A golden bullet had killed him. Another one could do the same.

"But gold," I protested. "I cannot find it here. I have no gold."

The woman drew something from the folds of her dress.

"This is a pistol that I took from the white man, Wingate," she said and thrust it into my hand. "I, also, am out of touch with the world. The girl called Helen owned a gold bracelet. I stole it from her when we were in the tunnel. I have molded a golden pellet and replaced one of the bullets in this gun with it. If fired into the king's head, it will solve for all time the problem of Haiti's salvation."

Never had I felt more humble before a woman. Here was a high priestess, born and nurtured in the savage jungle, aware of her duties to her people. I did not ask her why she had not shot Henri Christophe herself. It was clear that somewhere in that aged body lay dormant a love for the great black man.

"I don't know how to thank..."

"Don't thank me," she pleaded and pushed the weapon into my hand. "I will lead you to his chamber. Then I must leave you."

"But his men," I asked. "Won't they go on fighting?"

"Without Henri Christophe's leadership, they are helpless," she answered. "It is his will that forces them on."

THERE was no more to say. Praying for Helen's safety, I

followed the high priestess across the court. We kept well to the

shadows along the wall. I recognized the way to the lounge where

I had been a few hours before.

"He sleeps on the divan by the fire," she whispered. "I can go no further."

I took her hand in mine and bending forward, brushed my lips across the wrinkled fingers. I heard a sigh escape her lips.

"May good fortune bless you."

She was gone and I stood alone in the dimly-lit hall.