RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

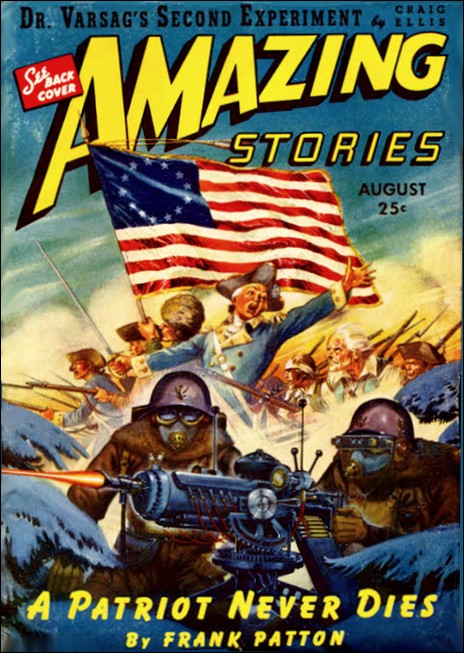

Amazing Stories, August 1943, with

"Meet the Authors: Lee Francis"

IT WAS a hectic year for the first appearance of Lee Francis. Women were shamelessly wearing their skirts cut well above the ankle and had gone so far as to powder their cheeks. Vitamins hadn't been mentioned yet, but calories were all the rage. Milk was going as high as nine cents a quart and you couldn't touch a good sirloin for less than forty-two cents a pound. Lindbergh hadn't been heard from, but the N C 4 was making a breathtaking trip to the Azores. Woman sufferage was more than a gag, and Babe Ruth was on his first year run toward the top.

Public school in New York then a quick trip to Auburn. We finally settled in Malone, New York, just a bit south of the line. That's where the fun-o'-living started.

I stole torpedoes from the railroad tracks and exploded them at the risk of blowing ourselves to bits, all for the noise they made. I watched Ringling Brothers shoot a wild elephant by chaining it inside a box-car and shooting it to kingdom come. I tried making a parachute of a square yard of canvas and some light rope. With a twenty-foot jump from a hay stack, I pioneered and bested the supposedly hard landings of the present day paratroops. Tom Swift And His Giant Cannon got me started on the finer books.

Nineteen years old: hitch-hiking to the west coast and a quicky up the shore to Vancouver via lumber boat. Those were lonely days. Six months cutting spruce and pine. Hidden in a lumber camp a hundred miles from the coast, and finally spending six months' pay in five days. Most of those days were spent getting over a headache and nursing a knife-wound in the wrist. Those saloon brawls with lumberjacks at their worst were some business.

The birds went south and I, damn fool, went north. Supply boat to Seward, Alaska. Salmon, sourdough and more salmon. Six more months in a salmon cannery and I'm still combing fish scales out of my wig. A rifie and a cabin inland and I was happy, for a while.

The monthly mail plane made the mistake of dropping a bundle of magazines to me. I found six copies of Amazing, went nuts over fantasy and science fiction, and as a matter of course, wrote my first story. Lots of wasted postage, three months waiting and the damned thing literally dropped back from the sky into my lap. A nice letter from the editor kepi me hooked, but good.

Over a typewriter in Seattle. I lived in Jap restaurants on First Street and ate myself full of fresh fish, mashed potatoes and bread. Staring down across the slanted roofs of Seattle at the Bremerton Ferry gave me my first real conception of the future. That ferry was a shiny, chrome-colored affair built to future's lines. I went to work.

About the realism and local color of "Citadel of Hate" I was there, buddy, and I ought to know. Don't let Haiti fool you. The marines left a lasting impression on that island that I think will scare away the ghost of King Christophe for all lime.

Drop in when you're in Seattle. You'll find me down on First Street about five in the afternoon. I'll be drinking black coffee, swilling down fresh salmon steaks and mashed potatoes. Tojo the Jap, who used to run this place, is somewhere in a California camp. He left town right after Pearl Harbor. The fish still tastes good, and the table-cloth is usually white enough to stand the tracing of a new plot.

Some day, when a steady row of traffic goes up the Alaskan Highway, you'll find my camp on the shore of a little lake about half way up. The claims staked out and ready. I hope some time to drop in on the editor of Amazing Stories and talk things over like I was used to it. That first letter of his, dropping out of the sky over a cabin deep in Alaska set my mind on fire. It's a great life, this writing your wildest dreams and deepest prophesies. The dreams of today are the facts of tomorrow, or isn't that original?

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.