RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

Amazing Stories, September 1947 with

"Terror on the Phone"

THIS account is presented in part by Doctor Jean Medeor of High Junction, Colorado and made complete by the diary of Frederick Cool. Doctor Medeor is no longer alive to present what proof she may have had of its truth. I am too tired and shocked to care whether or not the medical profession believes. Frederick Cool is also gone, yet the painful scrawl of his last weeks present a picture too pitiful to misbelieve and too fantastic to dare accept as the whole truth. It is the picture of a man dying the worst imaginable type of death. For Frederick Cool's brain was stolen and he died insane. Do I confuse you? Listen to Doctor Jean Medeor's letter written in the early Fall of 1944:

Doctor Peter Fromm

235 Trust Building

Fresno, California

Dearest Peter:

I told you that it would be hard to stay in High Junction this winter. I'm lonely for those cloudless, warm skies, and for you. I'll stick it out, for I know that a young doctor, and especially one of the weaker sex, doesn't get a chance to hang out her shingle every day.

High Junction is up here on the Divide where it gets snowed in sometimes for several weeks. The temperature drops to thirty below and shows a strange reluctance to rise again. I'm afraid I'd rather be Mrs. Doc Fromm this winter, but I decided to become a career girl, and I'll stick it out.

I do have an interesting case. Frederick Cool is his name and he used to run the telephone exchange here at High Junction. I'm afraid he's slightly wacky, Peter. Yet, he's nearly sixty and quite harmless. He has the smoothest face and kindest blue eyes I've ever seen.

Cool came to me three weeks ago. He said he had retired from his job at the exchange, because they had in-stalled one of these mechanical relay systems here for handling telephone calls. You remember the one down-town in Riley Township? A small, brick building, locked up, windowless, with a magic inside that sorts and puts through any call you care to dial? With them, one operator can handle several small towns. That gives you the picture.

Frederick Cool is insane for sure, Peter. I would say, after questioning him for some time that he retains only a vague idea of what goes on about him. I treated him kindly, advising him to get away from High Junction and take a vacation in a more friendly climate. He had a temper tantrum and wanted to know what a woman doctor would know about that. Threatened to change doctors. I reminded him that I was the only one in town and he calmed down a lot.

He said he was sorry, and that there was something that I ought to know about. I'll never forget how the poor old man affected me. It was a cold, unfriendly day to begin with, and a first snow had placed a wet blanket on everything, including my state of mind. Cool leaned forward and said:

"You see Doctor, I know I'm crazy. That's unusual, isn't it? Most insane people think that they are normal. I know better, and I know why."

His words were spoken hardly above a whisper.

"I haven't told anyone," he continued, "and I'm not going to tell you. My mind isn't clear now. I couldn't remember all the details, so I wrote them down."

He was wearing an old tweed suit with frayed cuffs, and trousers neatly patched at the knee with a slightly different colored fabric. He brought from his inside coat pocket a collection of papers. They were as many as the colors in Joseph's coat—pages torn from magazines with notes made in the margin—sheets from nickel scratch pads.

He passed them to me and ducked his head as he spoke, as though talking to the floor.

"I'm ashamed of the condition of my diary. I wrote when I could when my mind was clear."

Truthfully, Pete, I didn't want to read the stuff. I couldn't hurt his feelings.

"I'll keep this in my desk," I promised, and read it when I can. Perhaps it will give us a basis for treatment of your case."

That ended our conversation. He wandered out into the street and down past the new telephone building. It's a small, fifteen foot affair with a freshly painted, locked door. Inside, the mechanical 'operator' takes care of the job Cool used to take so much pride in. Cool hesitated opposite the building, then as I watched him, he shook his head slowly and went shuffling onward.

I didn't have time to look at the diary until the following Thursday. Then, as I expected Cool in on Friday, I scooped his papers from my desk, dropped them into my bag and took them to my hotel room. My room is very lonely, Pete. I guess I've mentioned that in every letter. I'll be very happy when I've proved to the world that I can be a good doctor, and have the chance to settle down and prove that I'm just as good a wife. Do I bore you, future husband?

Finally I put my bare feet on a hot water bottle, picked up Frederick Cool's strange manuscript and started to read. I intended to put it aside in twenty minutes. When the Central-Divide freight came through town at three this morning, I was still reading. Pete, I'm going to say the same thing that Cool did in my office the other day.

I'm ashamed of the condition of the diary. Cool wrote only when his mind was clear. He didn't write well. I tried to read with a cool, scientific approach. Now I'm exhausted and all tied up inside. I'm not at all sure of my own sanity. I'm sending the diary to you because it has given me a queer, lopsided viewpoint on life. Perhaps the intense cold has affected my brain. Perhaps I'm going crazy. You're the only one I can depend on. I've always come to you when I couldn't plan for myself, and you've never let me down.

You're so far away from this icy bit of Hades, perhaps you can read with a clear mind. I want your clear, honest opinion of Fred Cool's manuscript. I'm only sure of one thing now. When I pass that tightly locked phone building on Main Street, I stare at the windowless walls and wonder if strange death lurks within the sealed crypt. For Heaven's sake, don't tell me I'm mad until you've read every last word.

I love you, Doctor, in case you've forgotten.

Jean.

THE diary was in bad order when I started to assemble it. I became so

fascinated by the worn pages that I asked my secretary to transcribe them at

once. She worked on them as I read and soon the whole story was assembled in

some order and ready for study. For some time, I wondered if a trip to High

Junction would be necessary. It would be a good excuse to rush to Jean's

side. However, we had both decided that we must live alone, at least until we

could convince Jean's father that her study at medical college had not been

wasted time and effort. We hoped that once she had proven her worth to High

Junction, the old man would bless our marriage and accept me as a son instead

of a rank impostor.

It was a difficult decision, but I knew that I must stay away from Jean as long as I could. We would weaken easily if fate threw us together much oftener. We planned to marry in the Spring.

Perhaps, also, the diary of Fred Cool had the power to upset a man's thought processes, until the reader felt that he might be slightly mad to accept the material he found on those pages. Perhaps I, like Jean Medeor, wasn't able to think clearly after reading so unusual a story. You may judge.

—Doctor Peter

Fromm

Fresno, California

MY NAME is Frederick Cool. I am an old man now, yet not old judged by normal standards. I am done with life. Even now I am dead. Dead as surely as though someone held a knife at my throat. More accurately, my brain is being dissected bit by bit, and placed in another receptacle, prepared for it long ago. It will go on functioning, yet it will not be mine. My brain is helping a killer. A killer so powerful and so subtle that no one recognizes it or is able to prepare for war against it.

Let me tell you why I die without a brain, without knowing much of what goes on about me—or caring.

Twenty years ago I rode into High Junction in an empty freight car bound for California. In those days, three engines puffed up the mountain, dragging their heavy trains over the hump. I was young then, disowned by my family in England and recently arrived in America on a tramp steamer. I stayed in High Junction. I hadn't planned to do that, but a yard detective found me, half-frozen, jumping up and down beside the freight trying to warm myself. He warned me to get away from the train and foolishly I tried to quarrel with him. I awakened in jail, a hard lump on my head where he had hit me with his billy.

A sheriff with a walrus mustache warned me out of town in twenty-four hours—"or get yourself a job."

My last dollar was gone. I went to work for the High House, a two story, shingled affair, where I got three dollars a week and a small room beneath the stairs where I could sleep. Those first years were hard. Somehow, High Junction got into my blood. I would lie quietly on my bunk at night, listening to the freight trains as they puffed over the Divide. I would listen to the thin, high scream of the train whistle and the howl of the north wind, and somehow, I knew that I'd never go beyond this place. I hated it, and yet it was home. Perhaps I didn't hate it at all. It had a power that kept me from going on.

I worked for the railroad, laying ties for a spur line up to the mine. I worked one summer, deep in the mine.

Then, at last, I had a steady job.

The job wasn't important to the world. It was very important to me. The day I walked into the dusty loft above the General Store, I was as proud as a king looking for the first time at his throne.

High Junction depended on the "valley" for everything. The "valley" was Denver. If a woman needed a doctor—if the hotel needed supplies—anything—they phoned the "valley" for help. The Mayor called the "valley" for a sheriff to come up after a murderer.

Every call—every bit of business transacted with the "valley" had to go through my office. I ran the telephone exchange.

I thought I was the most important person in High Junction. Once we were snowed in for a week. I walked a mile through waist deep snow and found the break in the wire. I made contact with a portable phone and asked for a doctor to come and see Mayor Wiggins through a spell of the flu. Doc Deverish came. He had to leave the train three miles down the pass and ski from there. He saved Wiggins and the Mayor gave me a gold watch for doing what I did.

"You saved my life, Fred," he told me. "I was about ready to kick off my boots and give up the ghost."

Yes, I was very important to High Junction in those days.

IN looking back across the years, I see many things clearly that at the time

were confusing to me. I recall the first time I felt cause for alarm, and how

it affected my entire nervous system.

I had been alone in the office all evening. It was well after midnight, and few calls were coming through. To some, the loft would have been a lonely place. To me, it was home. I had a small stove which kept me warm and brewed my coffee. I decided to close up for the night, and was banking the fire when the warning light flashed on above the switchboard.

No one was formal on the telephone in those days. I put the speaker over my shoulders and spoke.

"Yes—who is it?"

I thought I could recognize any voice in town, but I wasn't familiar with the cold, impersonal voice that spoke now.

"This is you, Fred Cool," it said. "Just testing."

Someone must be joking, and yet it didn't seem very funny at that time of night.

I chuckled, but deep inside, the voice gave me a start.

"I suppose, then," I said, "that I'm speaking to myself?"

There was no answer.

"Who is this—really?" I asked sharply.

I could have waited all night. There was no reply. I hung up. I was shivering slightly, though the room was warm. The complete strangeness of the voice troubled me. I returned to the fire and drank a cup of coffee. I tried after a time, to convince myself that the whole thing could be blamed on my imagination. It was no good. Then the content of the message started to get under my skin.

"This is you—Fred Cool..."

That sounded so damned silly that I decided I was a fool to be taken in by such an unfunny joke. I left it that way.

The next day I was careful not to say a word about the incident. I felt sure that whoever the person might be who had called, he or she would rib me about what had happened. Such an opportunity would be too good to miss.

No one spoke about it. The owner of the voice did not call again—that night.

Those were strange years at High Junction. The town wasn't much. The main road came through here once but they changed the roadbed to a deeper, safer pass over the Divide. It left High Junction a small iron-mine town with a single train that puffed through once a day, weather permitting. People kept to themselves. They went to the "valley" only when it was necessary. Each man was respected for what he was, and not for the earthly goods he had collected. I held a respected place in the community. Not an attractive man, I never married. I lived alone, and I suppose, seemed somewhat of a hermit.

I didn't live what was termed a "normal" life. I ate when I wished, slept part of the time at the hotel and part of the time at the exchange, and came and went as I pleased. Often I stayed up throughout the night, taking care of emergency calls.

I tell you this, so you will realize, as I go on, that I knew how people talked about me. My actions, though strange, are explained entirely by the terrible fear that haunted my mind.

The voice spoke to me again at night, when a thunderstorm lashed at the mountains and lightning splashed its death lights across the water-swept crags. The storm was so violent that I failed to hear the bell ringing and noticed the warning light only when the lightning diminished and the room was quite dark.

I hurried to the switchboard, expecting news of fire or washout.

"How do you like the storm?" the voice asked.

I recognized it at once, though four months had passed since it had first troubled me. I was trembling, but I managed to steady my voice.

"It's—bad, isn't it?" I acknowledged. "However—I seem warm and safe."

I could never capture the quality of the voice. I could never explain it. Yet, I try here, for it was so important to know everything I could about it. If possible, it was a voice like drops of ice water plopping against my brain. It was cold and depthless, yet mechanical, as though recorded in hell.

The hair on my neck seemed to prickle and my heart pounded.

I said: "Who's calling? I don't recognize ..."

"Fred Cool," the voice snapped at me. "You remembered me at once. I could tell by the fear in your voice that you know me. You are Fred Cool—so am I. Amusing, isn't it?"

I was badly frightened.

"See here," I snapped. "I don't think this is funny. Perhaps I'm a poor practical joker, but I don't like this..."

The voice was suddenly very angry. "It's no joke. You will realize that soon."

DOC DEMOREST decided to come to High Junction. He was an old timer from the

"valley." A good man, but tired. He wanted to escape the big town. I went to

see him soon after he arrived. He was a sage as well as a medical man. In his

dark office, pale faced, bearded and fortified behind a huge roll-top desk,

he stared at me with twinkling eyes.

"Sit down, Mr. Cool," he said. "You don't impress me as a man troubled by minor ailments."

I was fifty then. I felt nervous and irritable. Often I forgot to speak to people I had known for years. Didn't even see them on the street, though they reminded me of our passing later.

I sat down a little heavily in the leather chair opposite him. I breathed a little hard and felt tired most of the time. I heard the voice often now. Sometimes I heard it in my mind, even though I was away from the office.

"I want a complete examination," I said.

Doc Demorest didn't move. His eyes weren't twinkling now. He stared at me solemnly, a little sternly.

"You're in good shape, Cool," he said. "Don't start taking pills at your age. Go home and forget it. You'll live a good thirty years yet."

I said: "I'm not sure. I notice a falling off in vitality. People tell me I act odd. I'm absent-minded and a little—strange."

Demorest chuckled.

"We're all a little batty above the neckline," he said, and tapped his head with his finger. "I'm crazy as a loon myself, but people expect a doctor to act odd. I get away with it nicely."

Normally I would have laughed with him. I wasn't in a laughing mood. I had to get the whole thing off my chest. It needed telling.

"See here, Doctor," I said eagerly. "I've been hearing voices."

"Lots of people hear voices," he said. "Lots of voices to hear."

I grew impatient.

"I mean a very special voice. A voice on the telephone."

He leaned forward in his chair. He studied me with his bright little eyes.

"Make up your mind, man," he said. "First you heard voices. Now it's a voice. Is it a babble of voices or just one voice?"

I felt ill and miserable. I stared down at the faded green rug.

"It's a voice," I admitted. "A voice that doesn't let me rest."

I told him the whole story then. How, ever since that first night, the voice had tormented me. When I finished, he straightened in his chair, searched his desk for a battered pipe and packed it full of tobacco. His movements were deliberate. He was deep in thought. When the pipe was lighted he puffed deeply and stared at the ceiling. Then he rose and went to the window. He came back after a while and put a kindly hand on my shoulder.

"I'm an old man," he said. "You are approaching the boundary of old age. As one man to another, why haven't you married and settled down to a normal life?"

He made me very angry. He was like the rest of them.

"Get married and settle down," they said. "You'll go batty, living alone." I didn't argue with him.

"Perhaps I should have," I admitted. "You see, I left the only girl I ever loved in England. She turned me down when my family took away my chance to gain a fortune.

"True, I'm lonely at times. Perhaps I envy other men."

I stood up, staring at him, trying to get across what was in my mind.

"But don't blame my present condition on lack of companionship. It's something deeper, more horrible than loneliness."

He nodded.

"I can't understand it," he admitted. "Somehow your 'voice' sounds convincing. I have heard people talk about you. I can't agree with them that you are feebleminded. It's something else. Something I can't quite put my finger on. I'll drop in at the telephone office some evening. I want to talk with you up there."

He opened the door for me when I went out, and I felt comforted by his understanding. I tried very hard that day to speak to all my friends. I was so careful to do so that I heard later that they stared after me when I passed. It was as unusual for me to speak to them as it had been to ignore them. They commented on it.

I was branded as a friendly but slightly warped old character. I did not imagine how much that affected my already faltering faith in myself.

AS THE years passed, I started to imagine impossible things. I talked often with the voice, yet knew no more now than I had to begin with. It always teased me until I often felt that I could stand no more of its merciless company. I wondered if it were possible to divide a man's mind into two parts and create two brains from one. I wondered where that other Fred Cool could be located, and spent hours trying to cudgel the answer from my tired brain. Hidden somewhere in that tangle of wires behind the switchboard was another Fred Cool. A merciless, mechanical Fred Cool who had cold murder in his voice. He was murdering me, bit by bit. Driving me mad.

Doctor Demorest came often. He liked to sit near the stove late at night, after he had escaped his own work and talk about his boyhood in France. I often talked about my early visits to Paris, and because I had learned to love that city, I held a place of respect in his heart.

Though we visited in perfect harmony, I knew that he had another reason for coming. He watched me closely, questioning me at great length about the voice in the switchboard.

"Take my word for it," he said one night, "one day all you people will be replaced by the machine. Mechanical controls will dial the number and get the party. Small towns will not employ operators. One operator will take care of a half dozen towns and the rest will be done by machine."

I agreed with him. I hated the thought of being replaced and having to leave this dusty, lovable junk room of the past.

I was older now. Older than my years. Though my mind was slow, perhaps even feeble, I handled the switchboard expertly, never faltering, never making an error. I was perfectly confident of being able to handle any number of complicated calls.

That night, the answer dawned on me.

Demorest came up about eleven. We had talked about the wonderful mechanisms

to come. It dawned on me that I had been a little hazy and uncertain about

things all day. Now, sitting at the switchboard, my mind was as clear as a

bell. I had been away from the office all day, and a substitute had taken my

place. How could I be so dense away from the exchange, and so

brilliant-minded when I was here?

"See here, Doc," I said, "don't think I'm entirely an ass. I enjoy your company very much but I know your real reason for coming here so often."

He chuckled.

"And what does the patient suspect?"

"That you are studying me," I said. "You know that I act queerly. So do I. You're questioning me, watching me—trying to guess just what really is wrong."

He frowned, then nodded slowly.

"I don't know just how to tell you, Fred," he admitted. "But the Town Council wants to replace you. There have been complaints."

That was a thunderbolt for which I was not prepared. I'm not sure that it surprised me, but I am sure that I was shocked. severely.

"But my work here has been excellent."

He nodded.

"I know. But you see, Fred, you act like a halfwit when you're in public. Everyone notices it. Fred Beecher down at the store says you're as crazy as a loon. Beecher is boss of the Council."

"Blame it on the headaches," I said violently. "I have them all the time now. I feel like blowing up in everyone's face. I have to choke back my rage and my fear. My head is a roaring, empty box. I can't act like a normal, balanced human, with that monster stealing my brain away from me."

He looked very grave.

"You still hear the voice?"

I started to shiver. My hands were icy cold.

"Not for a month," I admitted. "But—it's there. It's there waiting for me."

His eyelids lifted questioningly.

"Still there, is it?"

I knew I had said the wrong thing.

It was an idea that obsessed me. I hesitated to share it with Demorest, but I had no choice now. He was the last person who could protect me.

"I'm crazy," I said. "We'll admit that for the sake of an argument. Doc, I'm sure that there is another Fred Cool."

He leaned forward, eyes half closed. His lips were tight.

"Go on," he said.

"Another Fred Cool," I said. My lips were dry. "He's behind the switchboard. A brain—a mind—whatever you wish to call him, hidden in the labyrinth of wires. He's—stealing something from me. He's taking my brain. I can think clearly when I'm on the job, because, actually, I'm not thinking at all. That monster in the board is thinking. That other self. That's why I feel confident and free when I'm here, and like a hopeless idiot when I'm not."

Demorest didn't say he agreed. He didn't say that he didn't. He sat very still, smoking, staring at the ceiling as he fingered his pipe. The room was very quiet. After a long silence, he arose.

"Come in and see me tomorrow, Fred," he urged. "We've got a big problem to iron out."

As I watched him leave, I knew that I had lost. I had sealed the crypt of my own fate. Doctor Demorest was finally convinced that I was quite mad.

I leaned forward with my head on my arm. I'm afraid I cried. It was very lonely and I was no longer a young man. It's hard to lose your last true friend.

I must have slept after that, still seated at the switchboard. It made no difference. The calls went through perfectly, correctly guided by the monster in the switchboard who called himself Fred Cool.

Many changes took place in High Junction while I was away. Mostly changes for the worse. Main Street shrivelled and dried up for lack of paint and no interest in maintaining a ghost town. The daily train came only once a week now. Five hundred people remained, most of them miners, a few old timers.

I was almost a stranger in town now. A town of ghosts, yet to me a place of refuge. Doctor Demorest was dead. He had died a year ago, but it had been five years since I last saw him. Five long years since he had sent me to the state insane asylum. Because society condemned me and because I knew my job would be taken away, I went almost eagerly. Five years of sunshine and kind treatment had turned me into a weak, harmless type who could harm no one, and I was considered a fool by most people.

Jake Beecher, a teamster, gave me a place to sleep in his stables and I earned my keep by taking care of his horses. Old timers remembered me, and they were kind. Newcomers laughed at me. My clothes were not good and I'm sure my expression must have been vacant. I make these notes when my mind is quite clear and I can see these things. It is not often now that it remains clear.

Once I visited the lonely room above the general store, to stare a long time at the Old switchboard. It is dead now, its wires twisted and broken, dust laying across it in a deathly grey sheet.

Doctor Demorest had been right.

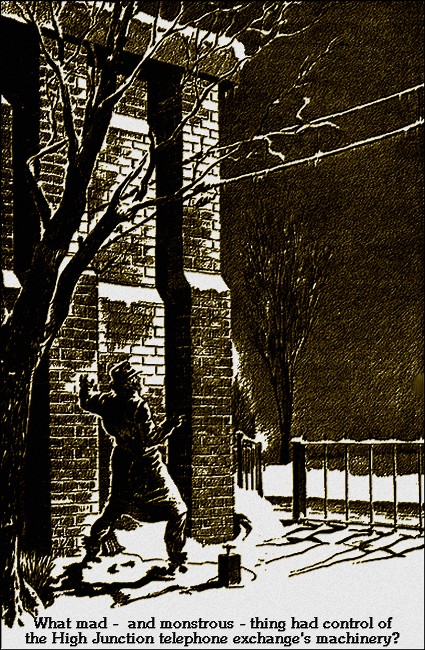

The mechanical man had arrived. No longer does High Junction have a human operator. In a neat, square brick building on Main Street, a complicated machine lurks in hiding. It has the power to accept calls, sort them quickly and send them in the proper direction. I know little about this wonder, and I have never seen the interior of the building. It is locked and mysterious.

I was able to find a certain comfort in lurking near the new phone building. The windowless walls hid everything from me. Yet, by going there, I am able to recapture some of the old spirit—some of the strength that is gone from my mind.

I know that people notice, and joke about my visits. I heard Jerry Beecher tell a friend:

"Old man Cool is harmless. Before he went batty, he used to run the exchange here. He and that telephone building have something in common."

I wanted to make them see that there was something in that building that was mine. The very brain—the mind that used to be mine—stolen from me and locked away in that tomblike building on Main Street.

It was late Fall. I had worked hard all day and when darkness came, I wandered to the phone building and sat alone on the steps. I was sitting near my own tomb. Sitting in the dark, a man alone, waiting for his brain.

"Hello, Fred Cool," the voice said close to my elbow. I jerked around, startled by its nearness. I knew the voice at once. A shudder swept through me. I hadn't heard it for five years. I tried to get control of my nerves, but it was difficult.

"H-hello..."

There came a sardonic, emotionless chuckle.

"So you remember me, do you?"

"I do," I said.

Another chuckle.

"So Fred Cool remembers Fred Cool. Ironic, isn't it?"

I had nothing to say. Dead. silence followed. Someone passed on the sidewalk and stared at me. The speed ofthe footsteps increased. Whoever it was, was afraid. Afraid of me. "You've been away."

"I suppose you missed me," I blurted out miserably. "Missed the opportunity to grasp all that was left. To leave a shattered, useless hulk."

The voice sighed.

"No," it said. "No, I'm quite satisfied. You see, I have all I need. I knew where you were, for our brain is one. You are me, and I am you. You see, you have all the bulk of the brain and none of the ability to use it. I have nothing in actual bulk, yet all the ability to think. That leaves you a halfwit, while I am a human mind, plus mechanical perfection. A very high quality, Cool. Very high."

I UNDERSTOOD it. A great mind in a maze of wires, unable to act for good or

for evil.

"I'm growing tired of this place," the voice said. "These people are so much like insects. Trivial things occupy them. They trouble me for all sorts of futile, silly things. I'm developed for greater fields, Cool. Our brain was a very fine one. You remember that."

"What do you propose to do?" I asked cautiously. I was responsible for this monster. I had to learn what it planned. I had to prevent...

"I will destroy High Junction," the voice said calmly. "Destroy it person by person. Then there will be no use of a telephone office here. They will take me and my complicated equipment to a larger, more interesting place. Perhaps, if I am not satisfied, I will go on destroying."

It sounded impossible. I might have been apt to blame this nightmare on my own warped brain. Yet, how could I? It was my brain that was talking. I wanted to run from this accursed spot and never return. Still, Fred Cool planned these terrible deeds, and I was Fred Cool.

I sought information that would help me destroy the brain that was my own.

"You cannot destroy anything," I said. "You can't escape from the building. You're tied among the wires."

The voice was metallic and grim when it spoke its last warning.

"Remember, Fred Cool, that there is always a way. Wait for Winter to come, and you will understand my plan."

A new doctor came to High Junction this week. Her name is Miss Jean Medeor, and she is as lovely as she is kind. In many ways, she reminds me of the girl I left in England so many, many years ago. I'm sure that she will be successful, although I don't know why she chose such an out of the way place to start a practice. She told me that she was in love, and that she wanted to be far away from her lover, as it would prove whether she could be a success or not.

I don't understand just what she means, but when I see her, with bright blue eyes, and a smooth, intelligent mouth that shapes itself into sympathetic ovals as I talk to her, I feel as though I want to cry.

I am very lonely and she makes me relive those first days, when I, also, had so much to live for.

Perhaps it was her youth and understanding. I told her my story, and left my diary with her. I know that in her heart she does not believe me. Perhaps she will when she reads what I have written. I pray that she does, for she is my last salvation.

Winter has arrived. A storm swept down from Canada last night and now the voice will act. I will try to save High Junction. I must try. It is my own brain that threatens to destroy it.

MOUNTAIN PASS SNOWED IN

Mining Community Cut Off From World

"A polar front, sweeping down from the Canadian Rockies late yesterday, brought a blizzard that cut off High Junction, Colorado, from contact with the rest of the world. The town, inhabitated by approximately five hundred miners and their families, cannot be reached for some time. The railroads are tied up with more urgent clearance problems on the main lines. Phone contact has been maintained and citizens of High Junction report that everything is satisfactory in the community. They say that help will not be needed at once."

I stopped reading at this point, and cold fear swept through me.

Phone contact had been maintained.

Frederick Cool whom I had long ago accepted at his face value, had said that the brain would get its revenge when winter came. Somehow, I knew that this was it. I had tried a number of times to imagine how a telephone relay system could get revenge. How it could harm a town. It seemed incredible, almost laughable, until this moment. Now I thought I understood.

The telephone reported that everything in High Junction was all right. It lulled the fears of the people in the "valley." It made them feel that they need not hurry. That time could be wasted.

Cold perspiration broke out on my forehead. I thought of Jean Medeor isolated up there behind a wall of ice and snow. Jean, fighting alone against—God knows what odds probably at this very moment trying to contact me.

I hurried back to the office and placed an urgent call. I heard the operator in the "valley" speak to Jean, and then she was on the wire.

Or was she?

The voice sounded like hers—and yet it was metallic, and a little abrupt. Not the voice that Jean would use when we had not talked for several weeks.

"Hello, Peter. I'm so glad you called. I'm all right. I suppose you've heard that we had a bad storm?"

I DIDN'T like that. She anticipated my worry. She—if it was

she—was trying to show me that she was all right.

"Jean," I said. "That business about the phone? Has anything happened?"

"Everything is under control," she said. "Don't worry about me."

Mechanical metallic the voice of a machine

"Oh," I said. "Oh, well, I thought I'd better check up on you. After all, I do worry about the girl I'm going to marry. Can't find one who'll accept a poor doc every day in the week."

She didn't laugh.

"Everything is under control," she said again. "Don't worry..."

I hung up abruptly. I swore under my breath. I hadn't talked to Jean. I had talked to a monster. A mechanical, murderous ventriloquist. I sat there for ten minutes, thinking—trying to plan. Then I hurried to the apartment, packed a single bag, put on the warmest clothing I could find and caught the afternoon plane for Denver.

I must have seemed foolish, rushing around the dinky offices of the Central Divide Railroad Company, trying to stir up some of the lethargy that seems to exist when a man wants something done and can find no one to do it. I talked with Jake Punkas, president of the tiny spur line that ran through High Junction. He was a slim little man, partly bald and carrying about that expression of one who could very easily go crazy if one more person asked him a foolish question.

I couldn't tell him why I was here. I could only tell him part of it, and that didn't make sense to him.

"But we've been in contact with the Junction since yesterday," he protested. "There's a good doctor up there, plenty of supplies, and they tell us that everything is under control. What more can you ask for? We haven't the equipment to send up now. In a coupla days..."

In a couple of days...?

I couldn't wait, and I couldn't convince anyone here that I was anything but a half-baked medico who had bats in his brain and was releasing them upon a much too busy world.

I had to get to High Junction at once.

I bought a ski outfit, packed my bag full of supplies and started alone. A farmer took me up the canyon as far as his car would go and dropped me there with nothing but mountains of snow and ice ahead of me.

He shook his head when I said I was going through to the Junction.

"Thirty miles almost straight up," he said. "Don't try it, Mister. The canyon's got fifty foot of snow in places. Slides and stuff ain't to be fooled with. You'll never get through."

When I thanked him and started out, he called after me.

"If you get lost and can't make it, stick near the tracks. They follow the river all the way up. The rescue crew will be through. They'll pick you up.

It was cold. So cold that it crept through me in ten minutes. I've never been good on skis. After a half hour, the scraping of those skis against the snow started a little tune through my brain. It persisted hour after hour, until at last, when I fell exhausted beside the trail, I was still saying over and over to myself :

"You'll never get through—you'll never get through—you'll—never—get..."

They said that it took longer to "thaw me out" than any man they'd ever seen. They were the train crew, and through some fortunate incident, they had been able to leave Denver much sooner than they had expected. In fact, the rescue crew left town on the same afternoon I started that hopeless skiing trip up the pass. My heavy clothing had saved my life.

I was still weak, but I had eaten hot soup and sat with the men in the caboose of the train. Ahead of us, a huge rotary plow fought its way up through the canyon.

The rotary broke down time after time, and the crew had to dig away the drift to give it a new hold against the snow. The river left a torn, black line down the canyon and the cliffs rose on both sides, dark and ominous.

We reached a high, flat plateau above the pass. Great peaks flung up their teeth like heads, making a circle around the flat waste of snow.

Ahead of us, where the town of High Junction should have nestled in the valley, there was nothing but a jagged pile of ice and snow.

One of the men swore softly. We stared at each other, our silence conveyed an understood message. Then the old brakeman said:

"They—they said everything was all right. That we didn't have to hurry."

"What's happened?" I asked.

The brakeman turned red, swollen eyes toward me.

"That's—High Junction," he said.

The train plowed ahead slowly.

"I seen the same thing happen over in Skinner Pass, 'bout sixty years ago," the brakeman said softly. "Slide came down and wiped out a thousand of 'em in one night. It was a hell of a mess."

The thin, eerie scream of the whistle announced that we had gone as far as we could go. The snow was twenty feet deep on the level. Ahead—God alone knew how many feet of jagged ice lay piled on top of the tiny hamlet.

IN A few hours, the engine had returned to the valley and brought us a complete rescue crew. Huge shovels worked in the moonlight, digging down to what had once been a town.

I guess they knew it was a useless job before they started. One thing kept them working steadily, throughout that long night, and other nights to come. Somewhere, down there at the bottom, there might be someone—something that still breathed. Up until a few hours ago, they said, they—had maintained phone contact with the town. I knew differently, but I couldn't tell them that.

But High Junction was gone. Gone as completely as though the great glacier had swept down upon it, crushing it to the ground.

I couldn't have stayed if it had not been for Jean. I borrowed a shovel and went to work with the men. Spotlights swept across the snow. I worked for ten hours before I could see what once had been Main Street. Fate intervened then, and I found that according to a small map Jean had once drawn of her accepted "home town," that the main tunnel was but a short distance from her office.

I worked without feeling now. My emotions were long since frozen by the cold and the uttter horror that was inside me.

At last with the help of my new-found friend, the brakeman of the rescue train, I located Jean's office, and found the broken plate glass with Jean Medeor, M.D. painted across it. The roof had collapsed, but near the stove, where we found her, the snow had not crushed everything from sight.

The stove itself was still warm, and she was close to it. Three timbers protected her body from the crushing weight above.

I didn't stay in the room. The brakeman said he would wait until a stretcher came down from above. I found a letter which she had been writing to me when it happened, and I took it out and up to the surface. I hid myself as far from the others as I could, and read it. It was my last contact with Jean, and I wanted to share it with no one.

"Dearest Peter..."

That was the most tender, pathetic greeting I had ever read.

Dearest Peter,

Fred Cool came to me today. He was exhausted and so frightened that he could hardly speak aloud. Last night he talked again with the voice—the brain. He visited the crypt of death that we so foolishly call the phone building.

I had to go with him—to see what he had seen. I had to stop guessing and satisfy myself as to my own sanity.

I met him at ten last night. High Junction retires early. We were careful not to be seen together on the street. Cool opened the door, for he had stolen a key. We slipped inside.

The storm was growing bad. I'm very much frightened when the wind comes down from the north. It does strange things up here—landslides—houses buried until Spring.

"Nothing to be afraid of," I told myself. "If Pete were here..."

It wasn't what I saw in that building, Pete. It was what I felt. In the darkness I could see only the ghostly wires that crossed and recrossed into banks of metal cabinets. There was a steady clicking, and the hum of power.

I sensed the other Fred Cool. I had long since accepted the fact that the voice didn't actually exist. It could contact Cool through thought waves, but could not be heard aloud.

Another Fred Cool actually lives in that icy, tomb-like place. A Fred Cool that is evil and a monster of death.

Fred Cool was ahead of me in the darkness. I could hear his breathing, as though even then he could hear the brain speak to him. He turned and I felt his hand on my shoulder.

"Go back," he whispered hoarsely. "Go back. I didn't realize. It is too late."

A panic seized me and I turned to run. I was frightened as a small girl is frightened on a moonless night. I heard a small, pathetic sigh behind me, but I dared not turn back. Outside, I turned in time to see the door click behind me.

Fred Cool never came out. The door closed before he could escape. I ran back and pulled on the handle. It was locked. I started to pound on the door, half crazed, wanting to help the poor old man inside. I heard a voice purring in my ear. At least I thought I heard it.

"This is none of your business. There is only one Fred Cool now. He cannot be saved."

I must have gone on pounding on that door, because someone came up the walk and spoke to me.

"Why, Doctor Medeor, what's going on?"

I pivoted and stared into the eyes of Mayor Joe Green. He had a puzzled, twisted grin on his face.

I tried to laugh.

"Guess I'm crazy," I said. "I've always wanted to see the inside of this place."

I know that sounded crazy, Pete. I know that I acted the part of a fool, but I just couldn't think straight. I had to say something. Green kept on smiling.

"You sure take a funny way of getting in," he said. "Next time the inspector comes up from the valley, I'll have him show you through the place."

He took my arm and guided me down from the steps. It's no good. Do you understand, Pete? Cool's body is in there. They take me there and they'll find it. They'll remember tonight and that I was there. They'll want an explanation that I dare not give.

I must destroy the building, Pete. The monster lurks within it, ready to strike. They'll catch me and I'll die for the murder of a man who came to me begging for peace. Peace from his own brain.

That monster grew bit by bit, sucking knowledge from a human brain. It hides there, partly wire and partly matter. Thick, clever and murderous. It must die, as I sooner or later will die, for murdering a man whom I tried to help.

That's my problem, and I need you, Pete. Need you more than anyone.

Jean.

THE letter was complete. Her signature was there and the envelope was

addressed to Fresno. The stamp had been placed neatly in the upper righthand

corner.

I had a job to do. I couldn't help Jean now. But the telephone building was still standing. The brick walls had withstood the battering ram of ice and snow.

I visited High Junction again that week, after spending a day in Denver. I rode up in a freight car, hiding myself from anyone who might recognize me. The car was filled with empty coffins, going up to the Divide to their rightful tenants.

In my bag I carried twenty sticks of dynamite.

The streets were clear when I came back to High Junction. The buildings were gone. Sprawled, ugly beams were everywhere. Men worked silently by lantern light.

I found the phone building and here there were no lights at all. Fred Cool's brain was alone, untouched, untroubled.

I packed the dynamite carefully into the small ventilation opening near the base of the structure. I broke the last stick and pushed the last of the brown powder carefully into place. Then I thawed ice with my breath and watched it freeze again, a tight seal over the explosive.

The fuse was long, and I was safely away from the place and mingling with the rescue workers when the place blew up.

The explosion rocked the mountains, and as I stared back at the dark, unhealthy cloud that reached into the sky, I fancied that I could see the spirit that hung over the place. It was like a black, fearful cloud of death that faltered and sifted to the earth destroyed, leaving only ashes and bits of broken wire.

There is no more to my story.

I think it fitting that I rode back to the valley in the same car, with the same load of coffins. This time I rode with the girl I loved—Jean Medeor.