RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

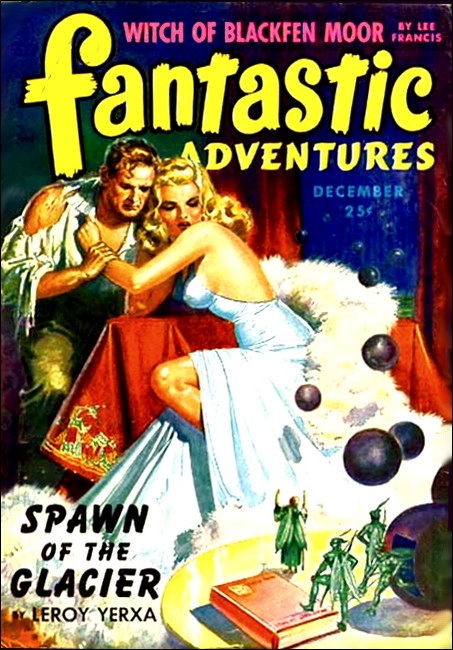

Amazing Stories, August 1943, with "The Witch of Blackfen Moor"

She was like a slender, lovely goddess, but she belonged to the Hall.

WALTER BREWSTER whirled around suddenly. His stern, gray eyes bored into those of his wife.

"Gratitude be damned," he said in a harsh voice. "It isn't that I've asked for. I've wanted your admiration and love. I've had no pleasure in your companionship since we were married. You'd make a fine mate for the Devil."

Pamela Brewster dropped the riding crop with an angry little motion and stiffened with rage. They were separated by the long length of deep carpet that covered the floor of the library. Pamela Brewster's eyes were narrowed with hate. Her slim, vibrant body contrasted strangely with that of the dumpy, middle-aged man. She had a touch of life about her that made men stare at her with quick interest. She was content only when others followed her about with adoration and her husband lost himself in other interests.

Her shoulders jerked as she walked swiftly across the room to him and stared defiantly up into his face.

"Marriage with Satan might have its good points," she said in a low voice. "At least life in hell would be more exciting than the year I am about to face."

Walter Brewster looked bewildered.

"What are you talking about?"

He stepped close to her but she backed away as though hating the thought of having him near her.

"You're a fool," she said coldly. "Why do you think I've stolen every hour that I possibly could away from this prison of yours? Why have I been riding away into the moor every morning, and staying away from you until I'm exhausted and starved. Yes, Walter, after all these years you've managed to trick me into supplying an heir for the Brewster millions. You can sit snugly in your library and gloat over the future while I become more miserable than I have ever been, living with you."

Her husband slumped down wearily in the great leather chair where he had so recently awaited her home-coming. Every word that she spoke, every gesture of her angry body, cut like a white hot barb.

"I'm—I'm sorry," he managed to mutter. "I didn't know...."

She stamped her foot angrily.

"Of course you didn't know, you blundering idiot. You haven't known anything about me since we married. You've locked me away up here on Blackfen Moor and expected me to wait dutifully for your every whim. But I haven't waited, have I, Walter?"

Her eyes became cunning. Walter Brewster sprang to his feet. His fists were clenched and the blue veins of his forehead stood out cruelly in the dim light.

"Shut up," he said hoarsely. "I've had all I can stand. Get out!"

The woman leaned closer to him, a taunting smile on her lips.

"You're going to have that child you wanted so badly, Walter. I swore that you never, would, but I was wrong. Perhaps, Walter, you would like your child to be an offspring of Satan?"

WALTER BREWSTER, beside himself with rage, reached out with

twisting fingers, but she evaded them and stood panting a few

feet away.

"That would be murder," she said. "As much as you hate me, you could never kill me."

Brewster stood very still, his head bent forward, arms hanging limply at his side.

"I'm—I'm sorry," he said contritely.

"Pam, what have I ever done to make you turn against me? I told you Brewster Hall would be lonely. Since you first came, I've tried to be a companion."

"Yes, you've tried, Walter." Her voice rose to a hysterical sob. "You—a man twenty years my senior—have tried to understand the mind and emotions of a girl who craves freedom and a good time. You've succeeded only in making yourself a father to me. I haven't been the simple, knitting kind of female you expected and you've tried to control me by shouting and threatening me when I break away from the Brewster tomb and look for amusement."

"But now," he pleaded. "Surely things can be different. We'll have...."

"Yes. The child. But don't be too sure that we will, Walter. Perhaps I'll die and leave it alone with you. You'll like that, won't you?"

He took another hesitant step toward her, misery etched on his face.

"Pam, please!"

She backed away swiftly, reaching for the riding crop.

"Stay away from me." The crop went high in the air. "I hate you, Walter Brewster. I'm moving to the west wing tonight and I'm taking Margaret with me. She's the only servant I'll need. Don't try to follow me into the moor because I can outride you. After a while I'll leave the Hall no more. You'll be happy then, when I am chained to my room and cannot escape you."

"The child?" he asked quietly. "You won't harm it?"

A wild laugh escaped Pamela Brewster's lips.

"Not for the world!" She seemed on the verge of breaking under the strain of the quarrel. "Remember, Walter, I am a consort of the devil. You said that yourself, and I hope that our offspring will be proud to carry its father's name."

She turned and left him alone. Logs in the vast fireplace at the far end of the library crackled loudly and he listened to them, and the firm, angry tread of her riding boots as they crossed the marble floor of the great hall and faded toward the servant's quarters.

At least she had chosen Margaret Jenson, the family nurse, for her companion. Margaret's fat legs had traveled the vastness of Brewster Hall since Walter himself was a child. No harm would come to the mother or child as long as Margaret's white-haired, patient head could remain in charge.

WALTER BREWSTER picked up his pipe, lighted it carefully and

then put it down once more on the tobacco stand. He wandered

toward the tall French windows and stared out upon Blackfen

Moor.

He had to admit, as he watched the sun sink over the foggy, brush-covered marsh, that Brewster Hall wasn't the place for a girl who was accustomed to having London society at her beck and call.

The Brewster tradition had been born on Blackfen Moor and the spirit of the rugged English countryside was in his blood. Perhaps he had been selfish to bring Pam here.

Brewster's thoughts changed abruptly as he saw the heavy storm clouds scudding in low from the sea. There would be a storm tonight, and heavy winds that would bring the moor alive with the ghostly movements of wild things. Brewster found his jacket, picked up the pipe and clamped it tightly in his teeth, and crossed the court and struck off toward Langley Crossroads.

If Pam were to have a child, Doc Quantry would have to know. Pam's hatred, Walter Brewster could not fight. That she get the finest care was of uppermost importance in his mind. The cold wind, wet with spray from the sea, made him feel better. Pam's wild foreboding seemed less real out here on the moor.

He shook his head impatiently, remembering her words:

"I am a consort of the Devil. Remember, Walter, you said that yourself."

THE night was bitter, even for Blackfen Moor. Doctor Thaddius Quantry wrapped his muffler tightly around his neck and drew his great coat close to his chin. In the hall of the small cottage he picked up his bag and stepped out on the porch. Langley Crossroads was asleep. He pulled out his stem-winder watch. Midnight. Walter Brewster had called shortly before twelve. The call was urgent. The long awaited heir to the Brewster estate was on its way.

Doctor Quantry looked toward the laboratory behind the house. A light was burning over the bench inside. Quantry smiled. His young assistant, Philip Brown, was still hard at work on the typhoid germs. Upstairs, Quantry's daughter Phyllis slept soundly, unaware of her father's hurried exit. Langley Crossroads, its small, thatched cottages in darkness, waited for day to awaken it. Quantry climbed stiffly into the carriage, touched his horse with the whip and they were away.

The beast kept up a sharp canter all the way to the crossroads that branched away from the London road toward Blackfen Moor. Then the carriage slowed and the doctor was forced to prod the horse continually to keep him on the move.

Animals feared and hated Blackfen Moor, he thought. Perhaps humans, excluding doctors of course, would be wiser to stay away from the Moor at night. It, like the rest of England's fairy infested country, had a full share of werewolves and gnome people.

Quantry chuckled. Doctors, with their hard-headed, scientific explanations, were the first to admit healthy superstition. To themselves, at least. Blackfen Moor held no terror for him, yet he freely admitted that he had, during his twenty years on its broad acres, seen things that made him hunch a bit lower in the carriage and apply the whip with added fervor.

Brewster Hall loomed in the darkness ahead. Its high, rock walls looked more like a prison than a home. The Brewster name went back to centuries long forgotten. Modern plumbing and electric lights stuck out amidst the medieval surroundings like small warts of modernism, unwelcome but necessary to the process of living in the twentieth century.

Thaddius Quantry admitted, as he saw the light burning in the west wing, that he must thank God electricity had come to dispell some of the gloom that hung over Blackfen Moor.

Quantry tethered the horse quickly and mounted the stone steps to the great hall. Roberts, the butler, opened the door. Roberts, like Margaret Jenson the nurse, had been with Walter Brewster from the first.

"Good evening to you," Quantry said. "The Missus? Is she holding up?"

Roberts, his stiff figure and calm, pleasant face always ready for any situation, smiled slightly.

"She's not receiving guests, tonight, sir. But, in your case—"

QUANTRY chuckled, gave the butler his coat, and went swiftly

across the hall. He met Walter Brewster at the winding staircase.

Brewster looked bad. Almost a year had passed since he had talked

with his wife. During that time his only knowledge of her was

gained through Quantry who made regular visits to the west

wing.

"Good evening, Walter," Quantry said. "You'd better take a sedative and sleep a while. Remember that heart of yours..."

Brewster waved an impatient arm. "Thadd," he begged, "make sure she's all right. If anything happens..."

Thaddius Quantry grunted. "You've been too damned good to her all along," he said impatiently. "The woman's a shrew if ever there was one. I'm a mild-mannered man, but at times that wife of yours tries me sorely."

Brewster sighed.

"I know," he admitted. "This has been pretty hard on her, though. After it's over, if she'll listen to me, I'll suggest a trip to London."

Thaddius Quantry was part way up the stairs. He stopped and turned around, a pitying smile on his lips.

"Walter," he said. "I've been family doctor to the Brewsters for a long time. You've done everything possible to make Pam at home here. She's—if you'll pardon me for saying it—a bit out of place on Blackfen Moor. She should be free to run wild in London. Only remember this, once you send her there, she's lost to you forever."

"If that's the way she wants it." Brewster said heavily. "It will have to be."

The doctor went upstairs quickly, turned down the long, drapery-hung hall toward the west wing and disappeared into the gloom.

WAITING patiently as he was destined to do for several hours,

Walter Brewster started as he heard a high-pitched scream of fear

from the suite of rooms Pamela Brewster had chosen. Cold sweat

stood out on his forehead and he turned and went haltingly into

the library.

Several times in the early morning he heard that same cry again. Each time it rose in pitch and sank to a groan of agony. Unselfishly, he blamed her suffering on himself. Once, Margaret Jenson came in hurriedly. He jumped from his chair, only to find that she brought a message that all was well.

Toward noon the cries lessened and the house was silent. Doctor Thaddius Quantry came slowly down the stairs to the great hall.

Brewster, his features pale as the marble floor under his feet, waited at the door. Quantry had a frightened, animal look about him. He had lost all the calmness of a country doctor. He took his coat mechanically as though trying to evade Brewster's eyes.

"The ... baby?" Brewster asked. "Pam? They both are all right?"

Quantry faced him squarely.

"Dead!" he said in a quivering voice. It was not like Quantry to lose control of his emotions.

Brewster's lips tightened.

"Not ... not both of them?"

Quantry launched into a hurried, somewhat garbled explanation.

"Your wife refused to live," he said. "She fought me off when I should have been able to help. She wanted to die. I tried to help her when the suffering was worse. She refused my help."

"But the child," Brewster begged. "Surely you could have saved it?"

Quantry drew the scarf tightly around his face. Only his eyes, cold with fear, were visible above it.

"Walter," he asked gently, "did Pam ever show interest in witchcraft or sorcery?"

Brewster's fists clenched tightly at his side but his answer was calm and low-spoken.

"No. You have a reason for asking?"

Quantry seemed at loss for a reply. He took his bag from the butler. His eyes were nervous, darting about the great hall.

"No reason," he said abruptly. "I'm sorry, Walter, believe me I am. I will sign the death certificates when I return home."

They faced each other, old friends torn apart by sudden mistrust of each other. At last Walter Brewster found words.

"I am free to go to them now?" he asked.

Quantry shook his head, shooting a meaning glance over Brewster's head at Roberts, the butler.

"I'm sorry," he said. "I think it best that you do not see them now. It will be better to remember Pam as you knew her before."

"But, my God, you can't keep me away from my own wife."

"I think she did a fine job of that herself," Quantry said harshly. "Now, for heaven's sake, get some rest before I have to sign a death certificate for you as well. It can do you no harm to stay away from the dead. It may be fatal if you go to them."

He turned quickly and went out into the night. Pronouncing the woman dead was a blessing! To say that Walter Brewster's child had died in birth was a lie. Nurse Jenson would keep her secret and Walter Brewster would be safer without the knowledge of what had happened.

Doctor Thaddius Quantry shuddered as he climbed wearily into the carriage.

"I TELL you, Thadd, I know you're lying." Walter Brewster leaned forward in his chair, his face red with excitement.

"That night after you left, I couldn't find Nurse Jenson. After she came back from the moor I tried to question her, but she was too frightened to talk."

Doctor Quantry tried to remain calm. Brewster had come to Langley Crossroad soon after dinner, and for the past two hours he had steadily questioned Quantry to no avail.

Twenty years had passed since that night at Brewster Hall—twenty years that changed both men; but the greatest change was in Walter Brewster. He had grown so wealthy that the influence of his money was felt far beyond Langley Crossroads. The Brewster millions had become a powerful part of financial London and every such undertaking that took place there.

Both men knew that Brewster's days were numbered. Perhaps this fact, more than any other, made them equally stubborn tonight.

Quantry placed the half-emptied glass of wine on the table. He shook his head sadly.

"It's no use, Walter," he said. "If you're trying to make me say your daughter is alive, I can't say it. I signed death certificates for both of them and you yourself saw them buried at the Rightwood plot."

Brewster picked up his glass, drained the contents hurriedly and put it down again. The force of his arm splintered the empty glass in a dozen pieces but he seemed not to notice.

"I saw two caskets put into the ground," he said.

Thaddius Quantry's expression didn't change, but his mind was in a turmoil. He had never thought this night would come. Brewster had been satisfied for so long that this new turn had come entirely as a surprise.

"Why are you so anxious to find this—this daughter of yours?" he asked.

Brewster sprang to his feet.

"Then you admit that she's alive?"

"I admit nothing of the sort," Quantry objected angrily. "The child was born dead. I'm too old a friend of yours to..."

"Rubbish!" Brewster grinned suddenly, a knowing, unpleasant grin. "You say she was born dead, do you? Then explain to me why I heard a child cry out after you left the house. Why the nurse left soon afterward, carrying a basket, and came home close to midnight without it. Why didn't you want me to see my baby and my wife after they died?"

Quantry's forehead was moist. His hands were clamped tightly to the arms of his chair.

"I am the only living person who knows what happened that night," he said stubbornly. "The nurse died five years ago. So far as I am concerned anything she did or said had nothing to do with your child. I saw it buried myself."

BREWSTER walked toward him towering over the old doctor.

"That casket was exhumed last week," he said in an icy voice. "There was no body in it. The box had been filled with earth."

Quantry started forward. He moistened his lips.

"Why are you so anxious to have your baby back now?" he asked quietly. "For twenty years the case has been closed. Surely you can't expect..."

Brewster's hand descended on his shoulder. The big man's voice was quiet, subdued once more.

"Because I realize now that I owe everything to the baby," he said. "I suppose you and Nurse Jenson thought I would abuse it because it belonged to Pam. I'm an old man, Quantry, and the boy, or girl—only you know which—would be almost of age. It could have a fortune when I die. I'm the last of the family and I want a chance to do a justice which I fully believe is due."

Thaddius Quantry stood up slowly. He walked to the window and stared out across the moor.

"If I told you the baby was alive and that Nurse Jenson took it away that night, what would you think of me?"

Brewster started forward eagerly.

"I'd think you were an ungrateful old busybody but if you did all this for my sake, I couldn't find myself being angry with you."

Quantry wheeled around.

"I cannot tell you why I did it," he said in a tired voice. "I will tell you that it wasn't for the reason you thought. I hope to God you never find Frances...."

"Frances?" Brewster placed a big hand on Quantry's arm. "Then it was a girl?"

Quantry nodded.

"Your wife named her before she died. Then she asked that the girl be taken away where you would never see her."

"But, my God, Thadd," Brewster started.

Quantry interrupted.

"I started to say I hope you never find the girl. The nurse took her to a poor family deep in the moor. What happened to her I don't know."

"I'll find her," Brewster said. "I'll find her if I have to search every town in England. And Thadd, when I do, I'll bring her here and you'll apologize to her on your knees for any harm you've caused her."

Quantry turned away from him, looking toward the dim, misty world of Blackfen Moor. A shudder passed through his thin body.

"For your own sake, Walter," he said in a hushed voice. "I hope you never do. If I'm wrong, and you love her as much as you think you can, then come to me with the girl and I'll try to make amends for what I did."

Brewster was putting his coat on hurriedly. He went to the door, paused and said in a more friendly voice.

"Don't worry, Thadd. As much as I'd like to wring your scrawny neck this minute, I think you did what you thought was best. I can't condemn you for that."

He went out, slamming the door behind him. Quantry stood as though in a trance. He heard Brewster's car start outside and listened to the sound of the motor as it faded into the moor. He turned, shook his head quickly as though to dispel a bad dream and went toward the wine bottle on the table. Pouring a full glass, he drank it down in a few gulps and sank into the chair.

"You have the wiseness and the kindness for which men give You credit," he said in a low voice, "In the name of Your Father, don't let Walter Brewster find that child."

THE trip to Brewster Hall was a long one. Roberts, always the perfect butler, drove as he acted, in a slow, sedate manner. Blackfen Moor had a foggy depressing night in store for the few visitors who must cross it.

In spite of the fog, the rutted road and the rain that would surely come before they could reach home, Walter Brewster felt a great weight lifted from his shoulders. He tried to analyze the feeling he had for Frances Brewster...

"Damn! What was that?"

The car jerked suddenly to one side, hit the soft mud at the edge of the road and Roberts managed to swerve it back into the ruts.

"Be more careful," Brewster managed. "We've plenty of time. Don't wreck the car."

Roberts mumbled a low apology and kept on the road. He was driving faster now. The butler seemed ill at ease, his head turning from time to time as he stared across the moor. Brewster found himself watching Roberts with nervous eyes.

"Did something startle you?" he asked in a more kindly tone.

For a minute Roberts was silent. Then he stopped the car suddenly and turned in his seat. Stark, unreasoning fear was in his eyes.

"I'm—I'm sorry, sir. Have you seen anything—that is—anyone following along the road?"

"On foot?" Brewster roared. "Don't be a fool! We've been driving well over thirty-five."

The butler started the car again.

"You must be right sir, but—I'd swear..." His voice trailed off into nothingness.

"You thought what?" Brewster asked angrily.

Roberts was driving much faster now. The car bounced over the ruts and Brewster held tightly to the side of the seat.

"When I swerved out of the road," Roberts said, "I did it to avoid hitting a man. That is, I think it was a man."

"You're seeing things," Brewster said sharply. "There's no one on the moor tonight."

Suddenly Roberts slammed on the brakes and Brewster slid forward, cracking his knee on the back of the seat.

"Clumsy..."

He stopped abruptly, staring ahead into the gathering mist. In the road, not ten feet ahead, stood a hooded man with arms upraised. His features were not visible, but a black gown hung down to his ankles and his feet were buried in the mud. Brewster's heart started to pound violently. His hands were shaking.

"It's he again, sir," Roberts said in a hushed voice. "He's been with us all the way from the cross-road."

"Damn you," Brewster said in a strained voice. "You'll have me believing it in a minute."

He leaned toward the window and stuck his head out into the fog.

"Say there—you in the robe. Get off the road, will you?"

THE robed man walked toward the car slowly. He came close to

the window. Brewster could make out a dark, wrinkled face and two

vacant, staring eyes that seemed to have no pupils. They were

large and almost white in color. The stranger leaned close to

Brewster before he spoke.

"I'm here, sor, to help you in your quest." The voice was hollow and matter-of-fact.

Brewster sank back on the cushions. There was only one quest he was interested in and this filthy, marsh creature could not know of that.

"I'm afraid I don't understand you," he said coolly. "Now that you are out of the road, we'd like to proceed."

The stranger stood his ground, two slim-fingered, muddy hands clutching the side of the car.

"But you're wrong, sor," he insisted. "I know of the babe. Perhaps you'd be looking for it?"

Brewster's hands clenched and he gazed at the man with horror in his eyes.

"How—could—you...?" His breath came hurriedly, hoping and yet dreading that this queer creature might know of Frances. "I have told no one."

"Then you have news before going to further trouble," the man said. "You don't want to leave me alone on the moor when I can tell you where Frances Brewster may be found?"

"Frances...." The man knew his daughter's name. Brewster thought only Quantry and the dead nurse knew that. Could this be some kin of Nurse Jenson's? No, he decided, the man is too unearthly. Too much like the nightmare creatures of the moor.

He pushed the door open quickly, and moved to the far side of the seat.

"Get in," he said. "We cannot talk here."

The stranger chuckled.

"Thank you, sor. It's been long since I drove about, gentlemanlike, in a fine coach."

The stench of him, when he closed the door, was as though he had lived his life in the unwashed robe. His teeth, which Brewster could make out in the faint light, were strong and sharp.

Roberts started the car mechanically, never daring to look back at the man behind him. He drove swiftly, the few remaining miles to the hall.

Let the Master handle this creature. Roberts had seen many strange things on Blackfen Moor, but this robed man was the strangest and the most terrible.

Once in the library, Brewster turned on all the lights and touched a match to the wood in the fireplace. Under strong light the deep-lined face and the round, almost white eyes of his visitor didn't trouble him so deeply. The very fact that he might find out something of Frances was enough to allay his fears.

The stranger remained standing until Brewster had finished. Then he went to the windows and drew all the shades carefully. Brewster watched him through half-closed eyes as he leaned close to the door and listened for an indication that someone was outside. Then he shuffled across the rug and stood before the master of Brewster Hall.

"We have long known you would look for your daughter when the time came," he said.

"But I don't understand how you found out I was searching for her."

WALTER BREWSTER had no intention of saying too much. There was

that feeling of distrust. A feeling that he was dealing with a

crafty, almost unworldly creature.

The man's face never changed expression. He had a mission and only words would perform it.

"I know where you can find her."

Brewster leaned forward eagerly. It made no difference how or where. He must see Frances at all costs.

"You can lead me to her?"

The man nodded.

"What is your price?" Brewster sprang to his feet. "Name any amount. It makes no difference who you are or where you came from. I'll ask no questions. Take me to my daughter."

The stranger remained calm.

"Wait, sor," he said. "You will have to enter the wildest part of the moor. It's a dark, rainy night. It's not comfortable for so fine a gentleman." His words were tinged with sarcasm. "Perhaps the shock would be too great."

"Shock?" Brewster demanded impatiently. "Shock? I don't understand. My daughter is all right?"

A quick nod of the robed head, and a hard chuckle.

"Right as light, sor. The price will be fair enough."

"Name it, I say. We must start at once."

"There is no price, other than you show me, this night, a will that leaves all your possessions to your only child. Also, that you promise that regardless of what happens, she will have a home here as long as she lives and that she be allowed to bring her friends here as she pleases."

"The will can be arranged at once." Brewster stepped to the wall and jerked on the long bell cord. "Roberts will bring it. It does not, of course, state my daughter's name, because I did not know it. The rest is taken care of by law. As for a home and a place to bring her friends, Frances may bring whom she pleases to Brewster Hall. I imagine the girl has been poor. That she has many girl companions among the poor families of the countryside."

A cunning smile crossed the stranger's face.

"I wouldn't say that she had poor friends, sor," he said softly. "But they's them that thinks we're a bit queer."

Brewster's jaw dropped.

"You—you are one of my daughter's companions?"

The robed head nodded in agreement.

"Her best friend," he said coldly. "They call me Monk, and there are a lot of us who don't look so pleasant as I do. We ain't bad when you get to know us."

Brewster shuddered.

"I hadn't expected...." he began, but a sharp knock on the library door interrupted him. Roberts stepped in, his eyes flashing suspiciously at the man with his master.

"You rang for me, sir?"

Brewster's shoulders squared suddenly and then dropped again. His voice was tired.

"Yes, Roberts. Bring my will from the study."

WALTER BREWSTER prided himself that he knew every inch of Blackfen Moor. Tonight, however, it may have been the rain that slanted across the sky in white sheets. Whatever it was, he found himself in a strange world, able only to keep his eyes on the steadily plodding figure in black who went ahead of him into the wildest part of the moor.

Brewster lost sight of Monk several times, then by brushing the rain from his heavy brows and straining his eyes into the distance, Monk became visible again, silhouetted against the white trunk of a barkless tree or outlined by a lightning flash. They moved steadily ahead for hours. Brewster's breath was coming hard and he realized that this was more exercise than he had dared to take for the past several years.

Never a word passed between them after they left the Hall. The man who led him seemed to be following a well-worn path, so sure was he of his direction.

Brewster could find no familiar landmark in the vast bog. The land was lower here. His feet sank into the soft turf and water oozed into his shoes. He was thoroughly miserable when at last Monk stopped and waited for him to mount a small hill to his side.

With water tracing the wrinkles of his face and the robe wet and clinging to his skinny body, Monk looked even wilder than he had at the Hall.

"A fair hike for a man of your age," he said, and the grin that accompanied his words was unpleasant.

Brewster, a little frightened from the beginning, wondered why he had trusted himself to the stranger's care.

"We are close to the place where my daughter lives?" he asked.

Monk remained standing before him, a sardonic grin on his lips, colorless eyes staring into Brewster's face.

"Very close," he said. "You are still sure that you wish to go ahead?"

Brewster grew angry.

"By all means, man," he said impatiently. "Am I a fool to come this distance in the rain and turn back when I am close to finding the child I've longed for these twenty years?"

Monk shrugged.

"Come along, sor," he said, and struck out across the top of the knoll.

The walk after that was a short one. Brewster saw the dim candle flame at a distance and knew they approached a hut.

Something within him warned that his daughter could never live in so filthy a shanty, and yet he had come so far that he could not turn back. Just what he expected as Monk threw open the door, Brewster did not know. He did not expect the single, poorly lighted empty room into which he walked. There was a table in the center of the dirt floor and on it a single candle burned down until the wax ran from the holder and onto the rough planks. Brewster looked about quickly, wheeling toward Monk as he slammed the door.

"You've—you've tricked me!" he said hoarsely. "No one, least of all my own daughter, lives in such a hovel."

Monk remained calm.

"Be patient, sor," he said. "You will remain here out of the storm. I will bring the girl to you shortly."

He turned and went outside. Brewster stepped to the door quickly, looked for a bar with which to lock it and found none. He backed slowly to the table, and sat down on its broad top.

HE sat there for several minutes.

Outside the storm had grown more violent. The low brush growth outside the single window whipped back and forth in the wind. Lightning, jagged and sharp, outlined the hill down which they had come and the single, whitened stump at its top.

The rain swished angrily against the window and dripped through the thatched roof. For the first time in his life Walter Brewster was really frightened. If he returned to the Hall without a knife in his ribs, the journey held more pleasure than he now imagined possible.

He heard footsteps slushing through the mud outside. Voices, low and mixed hopelessly by the wind, came to him through the door. The panel swung open. Monk came in, holding the door wide, his body bent low from the waist.

A girl walked proudly into the hut. Her body was covered with a snug red cape that fell to shapely ankles. Her head fitted snugly into a high peaked red hood. It wasn't her clothing that Brewster saw first. The face, her face, was tanned and had the softness of silk. Wide, almost black, eyes stared at him wonderingly but there was no smile of greeting on the full, red lips.

Brewster stepped toward her, arms outstretched.

"Frances!" he said in a hushed voice. "My God, girl, you're the image of your mother."

She turned away from him slightly, looking questioningly at Monk. Some signal must have flashed between them because a smile parted her lips and she allowed Brewster to take her hands in his.

"I—am—glad," she said haltingly. "I am told that I am to go to Brewster Hall with you. I hope you will have me."

Brewster was about to clasp his arms about her. He wanted to draw the child close. To tell her that if she wished it, Brewster Hall and the whole world would be at her command. To his surprise and anguish, she stepped away from him hurriedly, eyes smouldering with an emotion that was new to him. There was either intense hatred or fear there. She did not want him to touch her body.

"I'm—I'm sorry if I startle you." His arms dropped at his side. "It's been so long, and now that I find I have such a bewitching creature for a daughter, I'm afraid my emotions aren't quite under control."

The smile returned, but she stayed well out of his reach.

"Shall we go to your home?" the girl asked abruptly.

"By all means," Brewster said eagerly. "We will start at once."

He turned to Monk.

"You can guide us out of the moor?"

Monk grinned, and his teeth glittered strangely in the candle light.

"If the girl needs me," he said. "But she knows the moor well."

Frances Brewster turned quickly, her eyes on the robed man.

"Please," she said. "It is all strange to me. You will come!"

It was a command, not a question, and Monk bowed again in deep respect.

The rain had not lessened in volume but the girl did not seem to mind. She walked ahead of Brewster, her slim figure weaving gracefully through the marsh. As happy as was Walter Brewster to find his daughter, the strangeness of the meeting, and the frightened greeting she offered him, left him taken aback.

He was a tired, very uneasy old man. The girl, although startling in her beauty, was almost too much like Pamela in appearance. Could he be happy with her? Walter Brewster wasn't sure. Not at all sure.

DOCTOR THADDIUS QUANTRY jumped from his bed, only partly awake. His bare feet against the cold floor brought him quickly to his senses. The telephone in the hall was ringing. For how long, he could not guess, but there was something about the call at two in the morning that made him nervous. People did not call Quantry at this time of the night unless something serious was afoot.

He picked up the receiver.

"Quantry speaking," he said, a little sourly. "Who is it?"

"Doctor Quantry." The voice on the wire was low and vibrant. He could detect no fear, but there was something in it that sent little currents of fright prickling down his spine. "This is Frances Brewster. Will you come to the Hall at once?"

"Frances Brews...." The doctor's jaw dropped. "You said...?"

"Please, Doctor, there is no time to waste. My father is very ill."

Quantry tried to remain calm. Only tonight he and Walter had talked of the missing girl. Now, a few hours later, she was speaking to him in a voice as cool and matter-of-fact as though she had lived with her father since birth. Quantry sharpened his voice slightly to cover the shakiness that he felt.

"But, good lord, girl, where did you come from?"

Frances Brewster's reply was more abrupt than his question and filled with sudden impatience.

"While we stand here discussing me, my father is dying. Are you coming or aren't you?"

Quantry awakened to the critical Condition he was facing.

"I'll be there shortly," he said. "Wait for me and see that your father is given every attention. Roberts will know what to do."

She started to say something else, but Quantry hung up quickly and ran from the room. He shouted down the corridor.

"Phyllis, tell Philip to saddle the horse. I think the boy's still in the laboratory."

Sounds came from the far end of the hall and Phyllis Quantry, lovely in a soft sleeping gown and a wealth of wild, brown hair, pushed a sleepy head through a doorway.

"But Dad—tonight? The storm is still bad."

Quantry grinned. "Sorry," he said. "Can't be helped. Move along now. Walter Brewster's had a bad spell."

He thought it better not to confuse the situation by mentioning the return of Brewster's daughter.

Phyllis was fully awakened now.

"Sorry, Dad," she said. "I'll call Philip at once."

He made sure she was on her way toward the rear of the house with a lamp, then returned to his room and dressed quickly. From the rear door he heard the girl's voice calling Philip Brown from the laboratory and the polite tone of Brown's reply.

WHEN Quantry reached the front door, Brown had already saddled

the mare and was waiting in his rain coat for the doctor to come

out.

Brown had a tall, slightly bent body and keen eyes that came from patient hours over test tubes.

"Nice night, Doctor," he said with a grin.

Quantry swung into the saddle and took the reins from the younger man.

"Brewster's had a bad spell," he said. "I may be out until morning. If any calls come in, take them, will you?"

"And leave my little pets, the typhoid bacillus?"

Quantry grunted impatiently and brought the quirt down on the mare's flank. Philip Brown jumped to one side as the horse leaped forward. He waved his fist after the doctor in mock anger.

"I'll sue you for that, Doc Quantry," he shouted after the retreating figure. "So help me, I'll sue you."

Still smiling, he turned toward the laboratory. Phyllis was staring at him from the partly drawn curtain of her window. He blew her a kiss and, with head down against the rain, went back to the laboratory.

Quantry could see the single light at the entrance of the old castle. The rain blotted out the remainder of Brewster Hall as though it did not exist. He spurred the horse onward with a sharp dig on her flanks. No one awaited him as he went quickly up the steps to the porch. He found the knocker, applied his hand to it with gusto, and blew the rain from his nose as he waited.

Footsteps sounded loud against the tile floor and the door opened. Quantry's eyes widened. It was Frances Brewster, right enough. The girl was the image of her mother, yet even more lovely in her youth. The doctor stared at her, and the thing that had been troubling him these many years was once more uppermost in his mind.

"Come in quickly," she said. "Father is in the library."

Quantry stepped inside, removing his coat. Roberts wasn't about. He tossed his coat on a chair by the door and followed the girl into the library. She was wearing a red cape and snug boots covered her small feet. Quantry's eyes studied her perfect shoulders, trying to pierce the soft fabric that covered them.

Then he saw Brewster stretched out on the library couch and he went past the girl and kneeled swiftly at the stricken man's side.

He tested Brewster's pulse and heart quickly. There was still life, but little of it, in Walter Brewster's exhausted body.

Quantry turned to the girl.

"He has had the pills I left with Roberts?"

There was a cold stubbornness in her eyes.

"I tried to tell you that Roberts was not here."

Ignoring her, Quantry delved into his bag and brought out several vials. He pressed a small bottle of liquid to Brewster's lips and forced him to drink. Brewster's breath came harder, and moaning with pain, he opened his eyes. His gaze riveted to the slender, feminine figure behind the doctor.

He muttered something that the doctor could not understand, and started to struggle fiercely. Try as he might, Quantry could not hold him down. Seemingly unable to recognize his old friend, Brewster tottered to his feet and took one hesitant step toward the girl. She drew away from him hurriedly.

"Creature of Hell!"

Brewster's words were thick with pain. He pitched forward on his face, rolled over once and stared up at the ceiling with slowly glazing eyes.

QUANTRY dropped to his knees, placing the stethoscope to the

man's chest. He rose and faced the girl with cold anger in his

steady eyes.

"Why did you come?" he demanded. "He was well enough alone, without you."

Frances Brewster smiled.

"I believe, Doctor Quantry, that a sizable fortune comes to me with my father's death?"

"You could have left him alone to die in peace. What did he do, to deserve the end you brought him?"

The girl's lips curled into a savage snarl.

"He cursed me as he cursed my mother," she said. "And you, fool that you are, pronounced me dead to hide the secret from him."

Quantry took a threatening step forward. His fingers clenched, then loosened slowly. His voice shook with fury.

"If that death could only have been real," he whispered. "I wish to God that I had killed you that night, while there was yet time to save you from—from...."

"From Hell, Doctor?"

Quantry shuddered, and the girl went on.

"Let us not forget that you did sign that death certificate, and that if you do not serve me as I wish, I will betray you to your own kind. I imagine your reputation would suffer considerably if it became known that I am alive."

The color drained from Quantry's face.

"And to think that I let you live, hoping somehow..."

The girl interrupted him, drawing her shoulders up proudly.

"...somehow, I would escape the fate my father and mother gave to me? It is not too bad, Doctor; I will show you."

She flung back the cape from her shoulders suddenly, and stood before him with back and shoulders bared.

Quantry felt a shudder go through him, shaking his very soul. He cursed himself fervently and muttered a prayer under his breath.

The girl was straight and tall. The tiny, bone knobs that had projected from her back on the night she was born, had grown to wide-spread, batlike wings. She raised her arms above her head and the wings sprang outward with a sudden flurry of sound. She stepped close to him so that the horrible, ribbed things fluttered over them both. The still air of the room reeked with a fetid animal odor.

She was an eerie, yet lovely, creature of unnamed regions.

"I am a lovely sight, am I not, Doctor Quantry?" Her eyes hardened and became points of blackness. "Do you think I have any pity for the parents who conceived me as I am?"

Quantry sank back on the couch, his mouth wide. He could only shake his head. When he tried to speak, a dull, croaking sound came from his throat.

"The wings," she said. "They are almost ready to fly. With your care and the riches left to me by my father's will, I shall soon be ready for my conquest."

"Conquest?" He managed to repeat the one word.

The girl's wings sank to her sides and she faced him like a carved statue.

"Do you imagine that I will not make the world pay for this life I live?" Her voice sank to a whisper. "I have friends, Doctor. Friends who have been waiting impatiently for this time. You will grow to know them well and care for them when they need care. That is your part of the debt."

QUANTRY struggled to his feet and went swiftly toward the

door. He dared not look back, or think of what he had seen, lest

he go mad before he could escape.

Her voice drifted to him as he opened the door.

"You will come often, Doctor. When I call you here, don't hesitate, or I will tell the world that you abducted me at birth and told my loving parent that I died."

Quantry whirled around, his teeth bared. He leaned against the door like a caged beast.

"You—you witch!" he shouted.

The girl's laughter echoed through the stillness of the hall.

"A witch? Yes, Doctor Quantry. The witch of Blackfen Moor."

PHILIP BROWN had studied with Thaddius Quantry for twenty years. Brown, a quiet, sincere man of thirty-five retained much of his youthful appearance and all of the humor he had when Quantry brought him, at fifteen, to learn the inner workings of a doctor's laboratory. Philip Brown, because he was satisfied with the quiet life of Langley Crossroads, lived contentedly at the cottage and became more a member of the family than a long period boarder.

He had done some notable research work with typhoid bacillus, and London medicine journals gave him credit for improvements in treating this dread disease. Between his long trips to London, Philip Brown continued to court Phyllis Quantry with a steadiness that threatened to drive her mad.

It was close to morning of the same day that Quantry had gone to Brewster Hall. The old doctor had returned home several hours ago and Brown heard him lead the mare to the stable. He was a little disturbed that Quantry had not stopped in at the laboratory, but knew the old man would be tired and hoped he had gone straight to bed.

Brown glanced at his watch. Nearly six. He put several cotton-sealed test tubes away carefully, and turned the switch that cut the yellow light from the laboratory. Pale dawn over Black-fen Moor, sent a gray shaft of light into the room. Outside, the air was fresh and the rain had vanished.

Accustomed to a light snack after working all night, Brown entered the small kitchen. To his surprise, Phyllis was up and dressed in neat blue calico.

She greeted him with a smile as he came in.

"Good morning, Philip. You worked a full shift, I see."

Brown sank down in the chair at the table, sniffed the hot buns that she had placed on the cloth, and groaned.

"Sometimes I think typhoid germs aren't so bad after all, and why do I waste my time chasing them around corners."

The girl brought coffee from the stove and poured a fresh cup for him. She stood back, studying the grave-faced young man. Philip, she thought, could be in London, supported by rich patients and making a fine name for himself. Perhaps the very fact that he was content to remain here had discouraged her feelings toward him.

Phyllis Quantry was by no means unattractive. She had met Philip when she was a child of six and had grown up to regard his as a vastly older person. At twenty-six, Doctor Quantry's daughter was all things that Frances Brewster was not. Their figures compared favorably, but Phyllis Quantry's light brown eyes and well-braided hair produced the effect of light-heartedness that could have no connection with evil.

BROWN drank his coffee in long sips and munched on the fresh

rolls.

"Back to the subject of your early arising," he said at last. "I'm not accustomed to such attention. Are you going away for the day?"

The girl shook her head and her eyes clouded.

"I want to talk with you, Phil."

Brown turned in his chair and stared at her. Phyllis voice was low and filled suddenly with emotion. He thought she appeared to have been crying and cursed himself for not noticing before.

"Something is wrong?"

She sat down opposite him.

"Phil, it's about Dad. He's been acting strangely the last few days."

Brown chuckled.

"Oh, that," he said. "Haven't you noticed that whenever he and old Walter Brewster get together, the sparks start flying?"

For a moment she didn't answer. Then her eyes met his.

"Mr. Brewster is dead," she said.

Brown put the cup down quickly.

"Last night?" he asked.

She nodded.

"Dad refuses to talk about it. He says Mr. Brewster's heart was very bad and that last night something happened that was too much of a shock."

Brown looked thoughtful.

"He told you about his visit to the Hall?"

Phyllis leaned over the table.

"That's what troubles me," she confessed. "Dad told me only what I've told you. You probably heard him come in some time ago?"

Philip Brown nodded.

"I met him on the stairs. I've never seen Dad with that wild, frightened look in his eyes. I asked him if he wanted coffee or tea and he just shook his head. I had to follow him to find out what I did. He seemed so terribly depressed about something. It was as though he were trying to—well—to escape from something or someone."

Brown chuckled.

"Bosh!" he said. "Doc Quantry never tried to escape trouble in his life. He was tired and you misunderstood him."

Phyllis' eyes were suddenly misty with tears.

"I've always thought you would listen to me, although others might not. Dad's been under some sort of strain for years. Brewster has something to do with it and I can't understand what. I wish you..."

"Look," he interrupted her eagerly. "You know I'll do anything on earth to help you out. I think this is your imagination, but I'll try to help. Should I talk with your father?"

She rose, frightened by his suggestion.

"No, not to him. I'd—I'd like you to go to Brewster Hall. Perhaps some of the servants can give you a clue of what was wrong between Father and Walter Brewster. I'd like to help him if I can, but—well, without you on my side, it's pretty helpless."

BROWN stood up slowly and rounded the table until he was

standing close to the girl.

"Phyllis," he said hesitantly. "I wish you'd..."

She drew away from him.

"Please, Phil, I know what you're going to say. You've said it before and it hurts to say no. I like you a lot, but you seem more like..."

His face turned suddenly red.

"You were going to say I was more like a father or a brother to you?"

She nodded, not trusting her voice. A tear slipped down her cheek.

"You'll go to Brewster Hall for me, and for Dad?"

"I'll go," he said stiffly. "For you."

She heard him in the front of the house, searching for his pipe, and remembered she had cleaned it carefully and filled it with fresh tobacco.

"You'll find your pipe on the table in the hall," she called.

His single word—"Thanks"—drifted back to her.

She sat down at the table and started to cry softly. If only Phil Brown wasn't so slow-minded and good-natured about such things. The man she married must sweep her away from the commonplace. He must have fire and spirit that did not come from long hours hunched over test tubes.

THE butcher, his fat belly torn open with a knife, had not lived long enough to tell who had attacked him. It had happened quite suddenly, disaster sweeping down on the peaceful hamlet of Langley Crossroad in the light of day. Disaster made doubly horrible by the fact that death had struck in the bright sunlight and had not waited for the blackness of night to carry out its grim task.

Doctor Quantry was dragged into it soon after dinner. He had eaten silently, talking to his companions only enough to relieve the strain of a meal without speech. Quantry was nervous. Soon, he knew, the phone would ring and Frances Brewster would summon him to Brewster Hall. The witch of Blackfen Moor, she called herself, and she had a purpose in binding him to her with the threat of exposure.

The bell tinkled loudly in the hall and Quantry hunched forward in his chair, his cup of tea sinking to the cloth. Phyllis rose and went to the door. While she was gone, Quantry felt Philip's eyes focused keenly upon him, and he dared say nothing.

Phyllis returned, her face pale, voice low and even.

"It's the constable," she said.

"You're needed in town at once."

Quantry stood up, his knees shaking beneath him.

"For what?"

He hoped the girl at the Hall had not already carried out her threat to betray his secret.

"Butcher Moydan was killed in his shop. The constable says your coming will be a matter of form."

Both men left the room at once. As Philip Brown went out, he turned and sent a reassuring smile in the girl's direction. Then he followed Quantry into the street.

THE constable, William Laughlin, talked rapidly as they walked

down the lane toward the thatched shop.

"He's lying there in a pool of blood, he is!" Laughlin was a skinny, excitable man of fifty. "I'm telling you, Moydan looks like one of his own slaughtered sows. Ripped clean through the belly, and over five hundred pounds of meat stolen."

"Meat," Philip Brown said questioningly. "I don't understand. How could anyone steal that much meat, and murder a man, in broad daylight?"

Constable Laughlin shuddered.

"It's the people of Blackfen Moor," he said with an uneasy glance over his shoulder. "Them that are heard but ain't seen."

"Rubbish." Quantry was regaining his nerve. "We'll get to the bottom of this soon enough. Call in men from the Yard and have them track down our killer."

"Oh, they's tracks, right enough," Laughlin protested. "Not human ones, mind you, but they's cart tracks and blood in the road half way to Brewster Hall."

Quantry felt the skin on his neck prickle sharply. "But how...?"

"Easy enough," Laughlin said. "If you're going to ask how it could happen. Moydan always closed the shop for an hour at noon. They's them that remember a man driving a cart away from the back door about half-past the hour. The cart went toward the moor and up the road toward Brewster Hall. That reminds me, I'd best send a man up to warn Walter Brewster a murderer is at large near his home."

"That won't be necessary," Quantry said quickly. "Brewster died late last night. I was with him to the end."

The constable groaned.

"If it ain't one, it's two," he said. "Now we'll be digging two holes in the graveyard. Well, here we are."

They had reached the dirty, fly-specked window with William Moydan—Butcher lettered across it with black paint. The constable turned in and the two men followed him in. He unlocked the door.

Moydan had been a big man, and in death he wasn't a pretty sight. He lay stretched out before the counter, his arms and legs flung wide, the mountain of a belly pushed upward. The meat cleaver, red with blood, lay at his side. Quantry's breath sucked in sharply, and Philip Brown, after a single glance, went back to the door and stood there, staring out the glass and down the quiet street. He heard Quantry say: "He's dead enough. You'd better have him moved to the morticians."

Laughlin muttered something about needing six men to do it. Brown felt Quantry's hand on his shoulder and they went out into the sunlight.

Neither of them spoke until they were halfway home. Then Quantry stopped suddenly in his tracks.

"Tell Phyllis I'll be home in time for supper," he said. "I think I'd better run a little errand before it's too late."

Brown turned, startled by the sudden bitterness in his friend's voice.

"Look, Doctor," he said hesitantly. "If you're in trouble..."

Quantry shot him a keen glance, then grinned stubbornly.

"Ever since I was born, I've been in some kind of trouble. People always load me down with theirs when I haven't enough of my own."

Brown wouldn't be led away from the point.

"I mean it," he said. "There's bad blood between you and someone up at Brewster Hall. I'd like to go up there and see things through for you. Phyllis thinks..."

He stopped, flushed.

Quantry grunted.

"So that daughter of mine has been putting you up to things, has she?"

"No... that is," Brown stammered, "we were worried about you. If there's anything I can do..."

"Forget it, boy. You stick to research and leave the country doctoring to me. I'll run out and make sure Brewster's body is taken care of. I have to take the undertaker out and make a few arrangements."

Surprised that he could be brushed aside so easily, Philip Brown walked alone toward the cottage. Close to home, he stopped and turned. Doctor Quantry was just visible near the road that led into Blackfen Moor. He was walking swiftly. A stubbornness showed in Philip Brown's eyes and his jaw stiffened. He had been pushed around once too often. This time it was different. He couldn't let Phyllis down. He started along the moor road.

FRANCES BREWSTER heard the knocker above the raucous sounds in the dining-hall, and went to the door. Her face was still flushed with pleasure, but the smile suddenly went cold.

"Doctor Quantry? You came even before I called for you."

Thaddius Quantry was covered with dust from head to foot. The sun had soaked up the rain quickly from the road and left it dry and gray. The doctor's face was grim.

"You'll ask me in?"

"But of course." The girl stepped away from the entrance, allowing him to precede her into the great hall. "I hope your visit will be short and to the point. You see, I am entertaining."

Quantry faced her, his eyelids lifting in surprise.

"You have guests?"

The girl grinned delightedly, her face glowing.

"You will see them all presently," she said. "Come to the balcony that overlooks the dining-hall."

Puzzled, Quantry followed her up the broad stairs and along an upper corridor. He was forced to admire the trim figure of the girl as she walked ahead of him. With her body clad in the robe, the wings were not visible and he could almost forget them, so lovely was she in her disguise.

Ahead of them was the huge, grilled wall from which one could look down on the dining-table without being seen. The girl stopped, pointing a finger downward and Quantry turned to survey her friends. His eyes bulged and he clutched the rail of the balcony to steady himself.

In that instant all was forgotten except the hellish, unbelievable sight that was taking place below him. Walter Brewster's banquet table was running red with the blood of huge chunks of fresh meat. Its entire length was lost under slabs of beef and pork.

Arranged solemnly around the table, in ancient, high-backed chairs, was the most horrible collection of beasts he had ever seen. Some of them wore clothing, like Monk. Others wore nothing, resembling huge apes with grinning, evil faces. There were short creatures with immense paunches and thick, hanging chins. There were skinny, lank animals with huge ears that covered the sides of their heads and scalps that were dark-skinned and hairless.

Quantry turned, staring at the girl.

"These—these..." he gulped, not able to express what was in his mind.

"Creatures from Hell, Doctor," the girl breathed softly. "My best companions. Friends with whom I was condemned to live and to grow to womanhood. They look to me for leadership."

"But the meat," Quantry realized that the half-formed fears in his mind had proven correct. "This is the meat from the village. Those demons murdered the butcher."

The girl chuckled.

"Monk did that," she explained in a matter-of-fact tone. "You see, they live on fresh meat. It is better thus, than for them to feed on human flesh."

QUANTRY could believe that. As he watched, several of them

reached for a slab of beef. They screamed and fought over it like

dogs. A monkey-like, chattering creature jumped on the table,

grasped the beef in both arms and ran to the far end of the room.

He sat there tearing the meat fibers apart eagerly and stuffing

them into his mouth.

"But you can't expect to get away with this," Quantry protested. "The police will find the wagon. They will see that you are punished."

The smile left Frances Brewster's face. She was very close to him, her black eyes boring into his.

"I have learned one thing, Doctor," she said. "You mortals have an all powerful weapon called money. Money will buy everything on earth, even justice. I will fight every agency that is against us. By the time they decide that we are to be wiped out, we shall be too powerful."

The clatter of the door knocker came from the hall and the sounds below them stopped abruptly. The girl turned away from him and went back toward the stairs.

"We are having many visitors today," she said. "Would you care to greet them with me?"

Quantry hesitated. He must remain at her beck and call if he wished to live. What if Laughlin and the police had already tracked the cart to the Hall? Were coming to take away their man? What would be said when they found that Frances Brewster was alive?

He waited as the girl went down the stairs and threw open the door. From his vantage point, Quantry saw Philip Brown as the younger man took off his hat, spoke to Frances Brewster and stepped inside. Quantry went down to them hurriedly.

"Philip," he said. "I hadn't expected you."

Brown stared at him, then realized that the doctor was angry, and came toward him, smiling.

"Sorry, Doc," he said. "I was a bit worried about you this morning. Thought I'd come out and make sure you were all right."

He turned toward Frances Brewster, his eyes filled with admiration.

"Doctor, you didn't tell me such a charming young lady resided at the Hall. Was that the reason you hurried out here, keeping the secret from us?"

Quantry saw the warm, attentive look the girl gave Philip Brown and a new fear sped through him. It would be better to end this thing quickly.

"Philip," he said, "I assume you introduced yourself at the door. In the event that you did not, this is Frances Brewster, Walter's daughter."

BROWN frowned, a look of understanding flooding his face. He

stepped toward the girl and held out his hand. She took it in

both of hers and stood very still, staring up at his face.

Quantry was shocked to find a look akin to admiration in her

eyes.

"So!" Brown said slowly. "Now I understand why Doc Quantry was so worried about us coming with him to Brewster Hall, Miss Frances. We thought you were dead. Surely you've been away for many years? I'd have seen..."

She did not remove her hands from his. He felt nervous, and a little happy at the warm contact.

She nodded.

"I've been away a long time," she said. "Only now do I realize how long it has been."

The meaning escaped neither of them. Quantry cleared his throat hurriedly and Philip Brown turned red about the neck.

"I—I'm very glad to meet you," he stammered. "I hope that now we have discovered the doctor's-secret, you will let me see you more often."

"Thank you," the girl answered. "I'm sorry you can't stay longer, but Doctor Quantry was about to leave. I have some friends dining whom I don't wish to leave alone for long."

Brown smiled.

"I understand how that is," he said. Frances Brewster stared hard at Quantry.

"I'm not sure you do," she said. "But, in all events, we shall meet again. The doctor has just discussed one of my friends with me. You see, he had a little trouble with a knife, and the doctor has done a fine job on the wound."

Quantry thought of the deep slash in Moydan's body and the devilish creatures that even now were leaning forward at the dining-table aware of every word he spoke.

"Thank you," he said with as much coolness as he could muster. "And now, Philip, if you are ready."

They went out on the porch and the bright sunshine made Quantry feel better. Thank God, Philip had not seen the things at the Hall. Nor did Brown mention a word of Frances Brewster.

At last, no longer able to keep his thoughts to himself, Quantry looked sharply at his friend.

"I wish you hadn't followed me today," he said. "I'm not accustomed to being treated like a child."

Brown chuckled, pushed his pipe firmly in the side of his mouth and waggled a finger at the old man.

"Shame on you for keeping such a charming secret from me, Doc," he said. "Frances Brewster is beautiful and you and Walter kept her hidden all these years. I realize today why Langely Crossroads is such a fine place for me to work."

Quantry had been afraid of this.

"There are other things at the Hall which are not so pleasant," he said bitterly. "I'd advise you to stay away."

"Can't promise, Doc," Brown said quickly. "But that girl's got something that makes all my typhoid bacillus seem unimportant!"

IN the month since Philip Brown had first seen the girl of Brewster Hall, many things had happened in Langely Crossroads. Farmers reported that their animals had been killed at night and only the bones found in the morning. Men were knocked down while returning from their fields and food taken from them. No one ever saw these mysterious invaders who stole flesh by the dark of night. They were sinister shadows, prowling when the moon was hidden.

For the first time, Philip Brown was on his way to visit Frances Brewster. He had phoned first, asking for the opportunity, and now in the dimness of early evening, he rode swiftly toward the castle on Blackfen Moor.

The girl had awakened something in Philip Brown that he had never thought existed. He pitied her for her supposed loneliness and marvelled at her beauty. He felt alive and awakened to the things about him that he had missed during the long lonely years spent over test-tubes.

Brown was no fool. He was not sure that he had succeeded in finding out everything that troubled Quantry. The girl for example? Why had she been hidden for so long, to come suddenly to the Hall when her father died?

He reached Brewster Hall and waited quietly while the girl's footsteps came to him from inside. The door opened and she was smiling at him, more youthful and lovely than before.

Frances Brewster was angry at herself for the emotions she felt toward the man. Since he had left the other night, she had tried without success to keep him from her mind.

She held her hand out in welcome.

"I'm glad you called, Philip. I've been expecting to hear from you."

He held her fingers in his, feeling the warmth of them course through his body.

"Thanks," he said. "You're going to invite me in?"

A startled look came into her eyes and she glanced behind her hurriedly.

"I'd rather walk in the garden if you don't mind," she said. "Have you been in Langely Crossroads long?"

IT was pleasant in the old garden behind the castle. Walter

Brewster had lavished every care on the grounds. There was no

suggestion of strife or unhappiness here. They walked side by

side for a distance, reached the edge of the garden and wandered

into the moor. Her hand sought his and held it tightly as they

walked. Her voice was soft and confiding, telling of her love for

the moor and how beautiful it was tonight under the moon.

He tried to find out something of what had happened to her since that night when he was fifteen and Doctor Quantry had ridden home to announce that both she and her mother were dead. At his mention of her personal life, her fingers tightened in his and a frown crossed her face.

He wondered also why each time she saw him, the long cape covered her slim body, its lower edge trailing in the grass.

They walked for what seemed a long time. The moon rose high and for the first time in weeks, a soft peacefulness spread over Blackfen Moor. It could be beautiful like this forever, Brown thought, but usually it chose to show its teeth in storms and become a forbidding, remote place.

They found a stump and the girl sat down. Philip lighted his pipe and stretched out on the grass at her feet. Smoking peacefully, he talked of any small thing that came to mind.

Frances Brewster was completely at peace with the world.

"You have become quite famous in research work on typhoid, Doctor Quantry tells me?" Her words were a question.

He took the pipe from his mouth, and chuckled.

"I've become second brother to a test tube," he said dryly. "I'm only be-' ginning to realize what I've been missing."

They were silent for a time, and he wondered if the girl resented his ready friendship. He stared up at the full softness of her face, the dark eyes that stared into space across the moor.

"I suppose you have many friends," she said wistfully. "That is, you've been out with many women and have been about London a great deal?"

He shook his head.

"Sorry," he said; "can't qualify for that role. I've lived more or less a lonely life. Don't get much time away from writing reports and checking my findings."

It was growing late. The grass was cool with dew. A wind sprang up and the sea started to pound noisily against the rocks in the distance.

"Frances," Brown said suddenly.

"Yes?" There was a guarded note in her reply.

He stood up.

"There's something wrong at the Hall," he said suddenly. "Something that's troubling you and Doc. Is there anything I can do to help?"

The girl stared at him. A tear formed and dropped to her cheek.

"Nothing," she said firmly.

"But ..."

"I'm sorry. Nothing that is any of your business and you're better off to leave me alone. You shouldn't have come tonight and I had no business stealing away with you the way I have."

THE sudden change in her voice startled him. For the last few

hours he fancied they had been quite close.

Now she seemed to freeze toward him as though his presence was unwelcome.

She came very close to him, her hands on his wrists, her face tipped upward.

"I was a fool to come out here with you tonight," she went on, simply. "I was lonely. You're the first man who has been kind to me and I like you a great deal. But that can't alter things as they are. I'll have to ask you not to come again."

He realized then that love had come quickly, welding him to her so tightly that an unkind word cut him to the quick.

"And if I refuse to stay away? If I say that I've fallen in love with you and that I can't change it?"

A gasp escaped her lips and she stepped away from him quickly.

"You can't. You haven't any right."

"But you're not married," he said. "Surely your life is your own. I think you should give me some explanation."

Both wondered what to do or to say next. The night wind was cold and the moon blotted itself out behind rising clouds.

"I told you to go," she said. "I don't want..."

"You don't want to give way to your emotions," he said in a sharp voice. "I'm no fool, Frances. I love you and I think you love 'me. I thought it that first day I met you in the Hall."

He moved toward her suddenly, his arms sweeping about her waist. A low cry of pain escaped her lips and she jerked away from him. Too late! His hand closed about something rough and hard beneath her cloak. A puzzled, frightened look came into his eyes as she managed to break away to stand panting a few feet from him. Her eyes grew cold.

"You shouldn't have done that."

"What the devil?" His face turned pale. "I—I don't understand."

Her hands went to her throat and fumbled quickly with the catch that held the cape close to her. There was neither kindness nor love in her eyes now. Just that cold, expressionless stare.

"You wanted to know why I couldn't let you come again." The words were spoken mechanically, as though her mind or heart had no control over them. "I tried to make you go. You would never have known. Now you have hurt me and you have made it necessary to hurt you."

With a sweep of her arm she tossed the cape to the ground. She was clad in an exotic, low-cut gown and her shoulders and back were bare. Brown's breath sucked in sharply and his eyes widened.

Huge, bat-like wings spread slowly from her back and rose until they were poised above her body. She stood there in the darkness, a shiver passing through her body.

"I—I don't..." He felt like a fool. A poor, blinded fool, unable to understand what he was looking at. Frightened and filled with pity at the same time for something that was beyond his comprehension.

Her eyes remained hard and she made no attempt to hide the horror of her affliction.

"No one has understood," she said coolly. "If for once, someone did, it might help me to forget."

"But—they can't be real. It isn't... isn't human."

"I had no control of my destiny," she said.

"In the name of God," he gasped. "Something must be done."

A quick, hard laugh escaped her lips.

"God's name has had no place in my life," she said. "The situation is very much the reverse."

She bent quickly, retrieved her cape and started to don it. Philip Brown stood there, not knowing what to do or to say. Something of what must be in Doctor Quantry's mind was beginning to dawn on him, and he didn't relish sharing the terrible secret.

QUANTRY continued to visit Brewster Hall daily. He knew nothing of Philip's experience and managed to make the trips appear casual. The work he did there was too horrible for him to mention or to think of once he was away from the place. He became acquainted with Frances Brewster's companions, as she delighted in calling them. Monk was away on business and came back with a deep knife gash in his side. Quantry treated it without daring to ask questions, only to find that a farmer had been attacked the night before, his live stock stolen and the man himself murdered. The farmer had managed to slash at the intruder with his scythe before the man completed his gruesome job. There was blood on the road and on the scythe.

The trail led to Brewster Hall. It went on that way for the better part of a month. Langely Crossroads and gradually the whole coast felt the horror of a mysterious ruling force that could not be reached or punished. Quantry knew where the murderers and thieves came from. He could say nothing.

Philip Brown knew enough to keep him awake for hours, trying to reason the whole thing out with the cool mind of a research man. It got him nowhere. He would look up from his bench suddenly, and see the image of Frances Brewster standing before him as she had that night, smooth shoulders bare to the wind, those waving, ghastly wings balanced above her.

He could face it no longer. Something could and must be done. He loved her, and if she were the Devil himself, it could make no difference. He would speak to Quantry.

The opportunity came that afternoon. Still trying to keep up his interest in the laboratory, Brown spent several hours starting and developing new cultures. Doctor Quantry came in soon after noon and stood behind him, watching the young doctor work. Phyllis was away—at the village he supposed. Quantry wanted to tell Brown more. To confide in him and try to shift some of the burden that weighed heavily on his heart.

It was to be easier than he thought.

Brown turned suddenly, his face dark with concern.

"Why didn't you tell me about Frances?" he asked abruptly.

Quantry looked startled.

"I'm sorry, boy," he admitted. "I wanted to. After that night the mother died, I sent the baby away with the nurse. I had no idea who was to bring up the child. The nurse died and I never worried a great deal until Brewster came and demanded my help in finding his baby."

Brown nodded;

"That isn't what I mean," he said. "Why didn't you tell me about her affliction?"

QUANTRY looked at him steadily for a moment and dawning

understanding showed on his face.

"You've seen her body beneath the robe?" His tone was accusing. "You've been up to see her alone?" Brown was angry.

"I'm free, white and considerably over the age limit," he said. "I had every right to see the girl again."

"But what did you see?" Quantry slumped down in the nearest chair. "What possessed her to taunt you with —with...?"

"With those ghastly wings?" Brown shook his head. "I forced her to it. I love the girl, Doc, and I'm sure she loves me. It hurts like the devil to find that she is..."

He stopped talking abruptly, and a questioning look came into his eyes.

"Just what is wrong with Frances Brewster? You were there when she was born. Is it a curse? Such things that we read of, but never think to see?"

Quantry failed to answer for a long time. When he did, it was in a detached, far off voice of a man who cannot explain what he wants to say.

"I don't know," he admitted. "Pamela Quantry was a high-strung woman. She ran around with every young fellow between here and London. She practically killed her husband by laughing in his face every time he accused her of unfaithfulness. I know that Walter quarreled with her. She told me the night she died that he said she was a good wife for the devil. After that she laughed wildly and said it wasn't such a bad idea."

"Idiotic," Brown said.

"Not so," Quantry went on. "When the baby was born, it had a tiny stump growing from its back. I tell you, Philip, I came close to losing my mind that night."

"But it's utterly fantastic," Brown said in a low voice.

"Perhaps, but deny that the wings are real. Deny the truth you are faced with. I get the impression that the girl has moments of complete sanity when she is as tender as any woman. Then those damned wings take control of her and she becomes a demon. She told me herself, that the day they are strong enough to enable her to fly, she will go forth with her companions and rule the world."

"Companions?" Brown turned away from the table, looking down at the old man in the chair. "She isn't alone at the Hall?"

Quantry groaned.

"I wish to God she were," he said.