RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

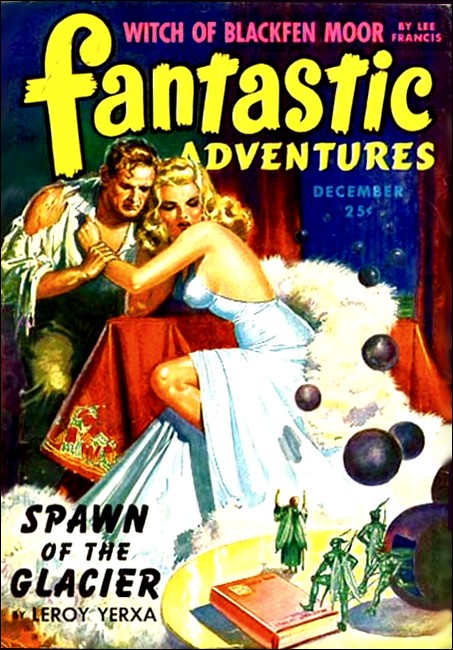

Fantastic Adventures, December 1943, with "The The Wooden Ham"

"You mean it is of wood—this beautiful pig-shamk?" the officer asked.

There was little food for the Dutch after the Nazis took

over. But they had their own method of keeping up morale.

TWO German officers marched briskly along the deserted street, hands on pistol butts, ready for target practice on any citizen who disregarded the Amsterdam eight o'clock curfew. Haarlem Street was dark and deserted as only a street can be when its people are cowering in the darkness of their rooms, under the Nazi yoke.

The faint glow of a single street lamp sent dim reflections against the tape-sealed window of a small butcher shop. Oberleutnant Carl Vaderlan caught a glimpse of something in that dirty window that stopped him in his tracks. He turned and stared at the pile of rich red meat displayed beyond the glass. In the center of the display a huge, juicy ham held the dim spotlight of the street lamp.

"Ho," he said in a brisk, hunger-sharpened voice. "What have we here?"

His companion followed him to the window and the two of them stared with wet lips at the well-cured masterpiece.

"You also are hungry?" Oberleutnant Vaderlan turned to his friend, the tone of his voice obviously suggesting that they do something about it without further delay.

Sergeant Anton Seyfahrt,* short, stout and a great eater, turned to the Oberleutnant with a grin on his sweating face.

[* The name "Sayfared" in the original is probably a typographical error. —R.G.]

"It looks fine," he said. "Fortunately I lived in Holland before you came. Have you never heard of the wooden hams of The Hague?"

Vaderlan's chin dropped. He scowled angrily.

"You mean it is of wood, this beautiful pig-shank?"

Anton Seyfahrt nodded.

"A great injustice to us both," he admitted. "But I'm afraid that in all Holland our Fuehrer has left no such luscious tid-bit for a prize."

"But—but of wood," the Oberleutnant objected. "The Dutch scum who tease our palates in this manner should be shot."

Sergeant Seyfahrt continued to smile.

"It is at our Fuehrer's orders that such ersatz ham exists," he said. "In The Hague, long before the war, poor people put such hams on their tables to improve the atmosphere. Our government has suggested that butcher shops supply not only wooden hams, but steaks so rare that they would seem to melt in the mouth. A silly thing, yes, but it makes these Dutchmen happy to see and to remember what they used to have before we took their meat for our own families at home."

Oberleutnant Vaderlan was obviously displeased. He hated to leave with no more than the thought of such food in his mouth. If the Fuehrer approved of such a farce, so be it. He clicked his heels smartly and turned away from the display.

"We are already late for our appointment." His voice was sharpened by anger and the gnawing hunger in his stomach. "We must hurry."

The Nazi officers stepped away smartly down the street and the lone street lamp continued to glow on the breath-taking, ersatz ham.

BEHIND the little butcher shop on Haarlem Street, Papa Jan Karr sat in his chair, his gray old head leaning forward on bony hands. The hands, white and covered with little blue veins, clutched tightly around the top of a stout cane. His eyes were closed and he was listening. Jeanne Karr, the old man's daughter, was reading quietly from a crumpled letter, her shoeless feet pressed close to the small coal-burner. Her two children, Peter and Rosana, cuddled tightly under the single sheet on the bed, drawing warmth from each other's frail bodies.

Jeanne Karr's voice was low and warm and the three of them listened closely as she read by the light of a weak-burning candle.

"... and I will be home soon. The Germans treat us well. I work each day in the gun factory, turning out more cannon for the great German Army to use...."

With a sob she dropped the paper to her knees. Papa Karr looked up and frowned.

"They make him write that way," he said kindly. "You needn't worry about your Johann. He will come home safe when it is over."

The girl continued to sob. Peter, his skinny, eight-year-old body quivering with pent-up emotion, climbed from the bed and went across the room, putting his small head on her lap.

"Don't cry, Mommy. The bad Nazis will go away some day."

Jeanne stopped crying quickly and put her hand over the little boy's lips.

"Hush, child. You mustn't talk like that."

At the front of the shop, someone knocked sharply on the door. Papa Karr leaned forward, his eyes growing suddenly hard.

"They have come again."

Jeanne said, "No—no," in a strained, small voice. The little girl, Rosana, started to cry in a whimpering monotone.

"Mama Jeanne, please, I'm hungry, Mama Jeanne."

The knock sounded again, more insistent than before. Jeanne stood up and went quickly through the curtain that separated the room from the shop. The old man called to her sharply, warning her to come back. Jeanne, hardly more than a child herself, went slowly toward the door.

A stranger stood outside. He wasn't in uniform. She went closer to the door, trying to see his face. The man might be a Jew. He was dressed in a ragged, dark cloak that hung to his ankles. His face was kindly, and in the lamp-light she could see him smile softly to her. She put one hand on the bolt, wanting to let in a friend, and dreading that he might be another Nazi playing some filthy trick to gain entrance.

"You may open the door." She could hear him faintly through the glass. "I mean no harm."

There was something in the warmth of his eyes, the kindly, pale face framed by long, shoulder-length hair and the heavy brown beard. She drew the door open silently and he stepped into the darkness of the shop. Jeanne drew the bolt tight once more.

"You want food?" she asked.

The stranger was ragged and lonely looking, and yet there was something in his face that made her feel warm and safe when she stood near him.

"You have food to sell?" he asked.

The voice was soft and yet filled with a confidence that she had not heard for a long time.

"A little," she said hesitantly. "We get few provisions now, but for our friends who are starving, there is always an ox-tail or a bit of liver."

THE man walked past her slowly and drew the curtain from the entrance to the inner room. He stepped inside. Papa Karr struggled to his feet and leaned heavily on his cane.

"Welcome to our home, such as it is."

"Papa," Jeanne said quickly. "The stranger does not care to hear of our misfortunes."

"But I hear of all misfortunes," the man said. He walked toward the children. Although they usually fled before those they did not know, both Peter and Rosana stepped forward and accepted his hand.

"Your family is hungry," the man said. "Have you not eaten tonight?"

Jeanne gazed at the floor.

"We have only two pounds of liver in the ice chest," she confessed. "When that is gone, there will be no more. The children have had all the meat since last week."

"And you can get no more?"

Her temper flared. She faced him with hard, glittering eyes.

"How would you expect us to? The Nazi dogs take all our food. Surely you live near here. You must know."

At once she was sorry that she had lost her temper. There were so many worries. So many heart-breaks. He did not seem to resent the hard words.

"I am sorry," he said. "Yes, I know that you suffer. Especially the little children."

"And how, sir, can we prevent it," Papa Karr demanded. "I have searched every stall in the city. I have stolen...."

"I know what you are forced to do," the stranger said. "Believe me, those who starve you must destroy themselves so that forever after this war, men will be free."

"Who are you, who can evade the Nazi gunmen who enforce the curfew?" Papa Karr demanded. "Who can walk freely in the streets when no man is allowed abroad?"

The man backed slowly toward the door. In the candle-light his beard glinted red and his face seemed paler than ever.

"Let us say that I am the man who came for the wooden ham," he said quietly. "Guard your window well, for tonight you are rich in food and tomorrow the children of Amsterdam will eat."

He passed beyond the curtain and it fell, hiding him from the little group in the cold room. Jeanne stepped after him quickly. If she had hurt his feelings, there was yet the two pounds of liver. He could have a bit of it.

She went into the shop with her key, meaning to give him meat and let him out of the door. Her eyes widened with fright as they swept around the miserable room. The man had vanished. He could not get through the door, for it was locked and she held the key in her small, cold hand.

She returned to the room where her family waited. Papa Karr was seated in his chair, rocking back and forth gently, propelled by the cane. His eyes were staring straight ahead as though into some far-off land. The children, still excited by the visit, sat close together on the bed.

"For tomorrow the children of Amsterdam will eat." Papa Karr's thin lips moved slowly, pronouncing the words with a reverence that Jeanne had never heard.

Peter came toward her slowly, his tiny hand folding around her finger.

"Mommy," he said in an excited whisper. "There was a white light around that man's head."

"Praise the Saints!" Papa Karr sprang to his feet. He stood there quivering in every limb, steadying himself on the long, tough cane. "The child is right! I saw it too! Jeanne, daughter, fetch the wooden ham."

Jeanne stared at him as though he had suddenly gone mad. Then a strange new light shone in her eyes. She turned and ran eagerly into the shop. The three of them heard her little gasp, then the glad cry that came from her lips. She came back quickly. In her arms, held tightly like a newborn child, was a huge, well-smoked ham.

It was not of wood.

She put it carefully into Papa Karr's lap and stood before him, tears streaming from her eyes.

"You must help me, all of you." Her voice was eager and filled with awe. "All the other wooden meat has turned to real meat. Quickly, before the German patrols see us."

OBERLEUTNANT VADERLAN was returning from the S.S. meeting. Still with him, Sergeant Seyfahrt paused once more before the butcher shop on Haarlem Street and called to his superior officer who had already passed several feet beyond the window.

"Anton, come here quickly. I have discovered a fine joke."

Angered by this reminder of his lost ham, the Oberleutnant paused. His eyes caught the empty shop window and he sauntered back to his friend's side.

"It is gone," he said in a mildly surprised voice. "The wooden ham, all the ersatz meat, is gone."

Seyfahrt chuckled.

"It is a good joke, yes? These Dutchmen are getting so hungry now that they eat wood. Wait until our Fuehrer hears of this! Tomorrow, probably, all the children of Amsterdam will be chewing on that cleverly painted ham."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.