RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

Fantastic Adventures, October 1942 with

"Corporal Webber's Last Stand"

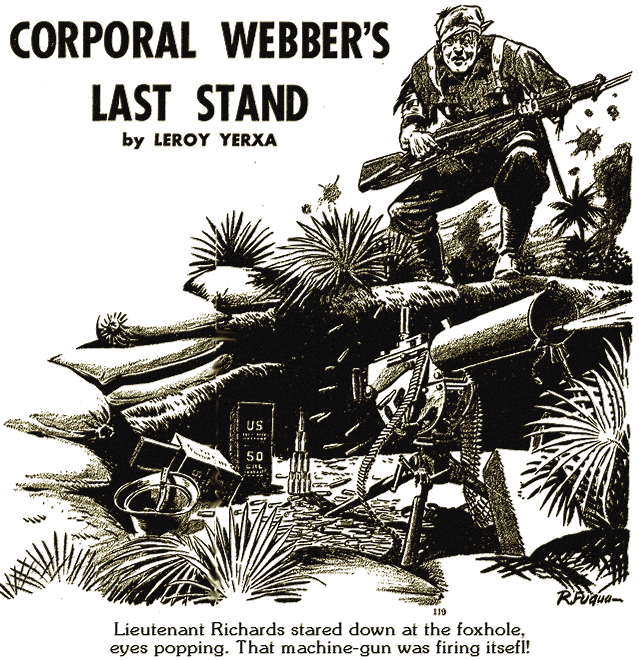

Webber didn't want to kill, even if it was war, so be decided that if he died, he'd escape that duty!

LIEUTENANT SAM RICHARDS pushed the flimsy bamboo door open and strode in. The rain blew after him, drenching the tall trench-coated figure. He ripped the stub of cigar from heavy lips and shook like an angry dog.

"Holy smoke," Sam muttered, "It's raining solid outside."

Walt Hubberd, slim, mustached and very tired, looked up over the stack of batteries from the communication set. He smiled, eyes twinkling from under heavy brows, and wiped water from his face.

"Yeah," he looked up at the roof. "They sure left these shacks well ventilated."

Ducking down again, he slipped his headphones on. Richards took off his coat and tossed it in the corner.

"Webber's at it again," he announced.

Hubberd's eyes narrowed to angry green slits.

"Sam," he measured the words in a low, tense voice, "I know you're the superior officer, king bee of the platoon and all that, but sometimes I can't figure you out. Why do you keep sticking up for that guy?"

Richards looked stern, trying to hide his fatigue. With the whole army south of him now, Balanga to be held until Bataan could be cleared of armed men, it was up to him and the platoon to hold the gully and two ridges until hell cracked. He grinned crookedly. Nine men and two guns left against two, maybe three hundred Japs.

"Come here, Walt." He spread the badly folded map out before him. Hubberd took off the earphones slowly.

They bent over the map and for the hundredth time tried to find a loophole. Richards' finger traced the small gully from the north, indicating the two gun-pits at the south lip.

"They have to come through the hole," he said quietly. "As long as we can cover that spot with a cross-fire, they'll stay in their own little rat-trap. The question is, how long can we keep their big guns from finding our positions?"

Hubberd shook his head.

"Looks to me as though they'll go through that hole like water through the dike inside of twenty-four hours."

Over the hill the two Brownings cut loose, rattling lead across the gully edge. Richards stood up, his lips tight on his cigarette.

"Nine men left," he muttered. "And now Webber's trying to turn them against me."

"What?" Hubberd's eyes darkened with fury. "Why that dirty—!"

Richards lifted a hand commandingly.

"Stow it," he grunted. "I can't be sure what's making him tick yet. This morning he made his gunner hold fire until almost twenty Japs managed to sneak through. They're headed south right now to snipe at the main body."

"That scum," Hubberd stood up, hands clenched behind him. "I'd like to drag him in here and wring his neck."

"So would I," Richards folded the map quickly, stuffing it into the inside pocket. "But I can't be sure. Walt—I think the poor kid's going batty. He's been crying all day about hating to shoot human beings; that it isn't right."

"They aren't human," Hubberd ground out. "Remember what they did up north last week?"

Richards nodded.

"Sliced the ears of one of my men and staked him on top of an ant hill."

"Why can't Webber see that! We're in the right in this war. We gotta kill them dirty snakes!"

"Maybe he will see it, before long . . ."

"Hell, I doubt it! He's just plain yellow!"

SOMEONE was stumbling and sliding through the mud from the hill behind the

shanty. Hubberd's head jerked forward, and the heavy service pistol came out.

The door rattled under a heavy fist. "Come in."

It was Edwards, first gunner in Webber's pit. He came in half drowned and swaying a little as he walked. His face had every emotion washed out of it, as though he wanted to vomit.

"Webber!" he leaned on the table, gripping it tightly. "The damned fool has killed himself."

Richards slumped back, pushing the dented helmet from his rough, sandy hair. Hubberd stopped pacing and stood very still by the door.

"Nine men left and Webber commits suicide! I told you he was yellow!"

Richards stared at the gunner, lips drawn out straight and hard.

"How did it happen?"

Edwards sat down, rocking his head in his arms.

"I was on the gun," he said slowly. "Webber told me to hold my fire, like this morning. I knew number two pit was firing hell bent for election and expected me to alternate. The Yellow Bellies were going over the gully lip every time he stopped firing. I cut loose and Corporal Webber commanded me to cease firing. I kept right on giving them hell, and he started sobbing like a baby."

"'You can't kill those men,' he kept shouting. 'They got families like us.'

"I shut my mouth and kept on alternating every twenty rounds. After a while they stopped crawling out of the rat trap, and I let the gun cool down. I looked at Webber. He was sitting in the mud, tears streaming down his cheeks. Honest to God, Lieutenant Richards, sir, the Corporal was playing with empty cartridge shells. He played like a kid with blocks, making little piles of them and sobbing like hell all the while."

He stopped talking and brought out a filthy cloth. He blew his nose loudly.

Hubberd hadn't moved from his spot by the door. He was staring queerly at Richards.

"Go on," Sam said. "What then?"

Edwards gulped.

"When the Yellow Bellies went through again I started a cross-fire. This time Webber stood up with his arms over his head and howled like a sick dog. I didn't see him do it, but he must have scrambled out of the pit and around in front of the gun. Before I could hold fire he got a salvo in the knees and fell right in my face—" he almost broke down. "It was awful—awful."

The lieutenant stood up. He clutched the coat and pulled it on stiffly. Bending over Edwards, he gripped the gunner's shoulder.

"Come on," he said. "We're going back to the gun."

NUMBER ONE gun pit was boiling lead. They reached it through the shallow

trench. Assistant gunner Brown and the platoon's skinny truck driver, Slim,

fed the 30-caliber Browning all the lead it could gulp. Sure that both guns

were still in action, Richards turned toward the bloody mess in the far side

of the pit.

Corporal Webber had died hard. His knees were broken and shredded with a line of slugs straight up the belly and over his head when he pitched forward.

"Slim," Richards growled. The truck driver came forward.

"Yes, sir!"

"Take him back over the hill and cover him up."

He watched Edwards take his place again behind the heavy barrel of the Browning. Turning to leave, he kicked something in the center of the pit. Stacked neatly in little pyramids of ten, the small row of empty cartridges stared up at him. For a second, compassion softened Richards' muddy, scarred face. Then he kicked at them savagely, trampling them into the mud. What if Webber was right, and killing of any kind was wrong?

Edwards' finger tipped lightly against the trigger, sending a salvo of lead across the field. The gun across the ravine answered him.

With a strange gleam in his eye Richards went back along the trench to the safety of the hill. His face was blanked of emotion. The rain had stopped, leaving broad leaves to drip—and down across the hill a brightly-plumaged bird flashed against the wet green. Both guns ceased firing and a fiery lopsided sun came out for a while, sinking into the brush-land toward the west.

SOMETIME after midnight Lieutenant Sam Richards came up on one elbow off the

hard floor. Guns were clattering to the north.

Rattle—stop—rattle. Jap machine guns coming in close. Branches

ripped off the trees atop the hill. He got into his coat and went

outside.

The bamboo hut went white and clear against a dazzling light in the sky.

Crump. The sulky, earth-ripping trench mortars were tearing holes somewhere near his gun positions.

He ran, head down toward the lip of the gully and number two gun. Edwards and Slim would take care of themselves.

Crump. The way those mortars were raising hell, there would be plenty of Japs in the gully in a few minutes. He crossed the gully edge, and snaking across it studied the land to the north. No movement yet. On again, he pitched face down in a fox hole, the tree above him tearing itself apart under a shower of lead. Belly pressed into the mud he almost fell into number two pit.

Two men alive, two more faces up, lying against the side of the hole. Tanner, number one gunner, saw him, and crawled out from under the trigger. His face was twisted and filthy with grease and smoke.

"If you'll take over for a while, sir?"

Far to the north, big guns started to rumble. 105 mm howitzer shells ripped into the gully, shaking the ground as they dug in. They were cleaning up for the advance.

Sighting down the barrel, Richards felt the water jacket lovingly and lined the Browning over the stake driven outside the pit. His assistant jammed in a new cartridge-belt. Richards pulled the trigger back and felt them engage. Before he could see the Yellow Bellies, he opened up. The trigger came back almost gently and the front of the pit blued with smoke and dirt. Edwards heard the salvo from number two, and cut loose with his reply.

SOMEWHERE out front Richards thought he heard an outcry. The howitzers

stopped and he felt rather than saw the long line of creeping Japs in the

gully.

The first belt was empty. Another rammed into place and again the trigger tripped back. Behind him he heard the crump of a mortar shell. They were creeping up. Finding the range. On the other side he knew Edwards was in the same spot.

Crump. Richards jerked forward, felt the rough shower of flying mud and knew something hit his helmet with a jarring shock. He shook his head, felt the cartridge belt feed out again and turned. The pit was half filled with débris. His men were buried alive under it. Dropping the pistol grip he started to dig savagely with bare hands. They came out of the soft soil, dripping red.

The gun across the gully stopped abruptly. He grabbed like a crazy man for the half-buried ammunition box, and waited for Edwards to start firing again. There was another burst of fire from number one pit. Breathing easier he answered with his own gun.

A terrific explosion ripped at the sky across the ravine. For fifty feet on all sides of number one gun, the earth went up, heaving trees and mud in all directions. Sam groaned. He'd have to fight alone. He tried to drag the heavy Browning back. The mortars had almost got his range. He felt a twinge of pain in his knee and sank back swearing. The bastards had broken his knee cap.

The bloody hand went back to the pistol grip. His lips were dry and tasteless. He kicked the gun over. The night was suddenly very silent.

"What the hell's the use!" he thought out loud, trying to pull his game leg out more comfortably.

Voices sounded, smooth and oily in the gully. They were going through it by the dozen. Through to the south where they'd flank the whole damned army unmolested. But maybe their cause was right . . .

His knee hurt like hell.

Then the death-rattling of number one gun broke loose from across the ravine. Its sudden clatter brought him upright, and he pitched forward against the side of the hole. The knee was forgotten. This time he knew there were screams. Howling, slobbering Sons of Heaven were dying. Japs—yellow-bellied Japs were falling and dying out there on top of the ravine.

RICHARDS looked over the edge of the pit, eyes wide with amazement. The first

gun was running wide open, spitting out compressed hell. The main Jap

movement had already left the ravine and were concentrated in the open field

to the south.

He had thought the howitzer shell had blasted number one pit from the map. Common sense told Lieutenant Richards that a Browning only fired two hundred-fifty rounds without reloading. Still the gun didn't hesitate. It was stacking Yellow Bellies up like red chips, rattling on and on like an angry hornet.

Forgetting his own safety, Richards went up on one elbow and lifted his helmet into the air. He waved it wildly, the powerful, seamed face lighting up.

"Give it to 'em, you tough hided son of a—!!!"

Then, as suddenly as it had started, the gun was silent again. Only the groaning of dying men disturbed the night. He listened carefully for a long time, as they who were left went back along the gully toward the north. Then he started crawling painfully toward the first gun. There was something here that Lieutenant Sam Richards couldn't figure out. Something that—!

He reached the gully, lowered his game leg over the edge and dropped silently down. Up the opposite bank, he crawled slowly, pulling most of his weight with his strong arms. Then he realized what the howitzer shell had done to the first gun pit.

It wasn't there. At first he looked for the gun. Where the pit had been there was nothing but a deep, ragged edged scar. A spewed up, broken tree leaned over it at a crazy angle. Edwards' body, blanketed with mud, lay face down on the lip of the shell hole.

Richards' knee was giving him trouble again.

The solitary tripod was all that remained of the Browning. Rolling over painfully he reached out and grasped one of its legs in his hand. As though waiting for. the safety of silence, the moon slithered between heavy cloud banks and flashed broken streamers of quick-silver across the open pit. Something glinted in the dirt beside him. Richards' face turned stark white, frozen with holy fear.

His hand went out, reverence in the touch, as his fingers fell on a precisely stacked pyramid of empty cartridges. They were in a neat row, exactly like the ones Corporal Webber had played with before he went down under the Browning's ripping hell. Slowly his hand came away, and he slipped one of the shells into his pocket.

"I knew you weren't a coward, Webber," he whispered. "Where you are, things are plainer to see. Folks have a better idea of what's right and wrong. And I'll give the boys your message, Corporal. I'll show 'em this cartridge and tell 'em where I found it. And I'll tell 'em how you came back to do the right thing when you saw it. I'll tell 'em, because knowing you're doing the right thing makes it easier to do. And you oughta know, Corporal Webber!"