RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

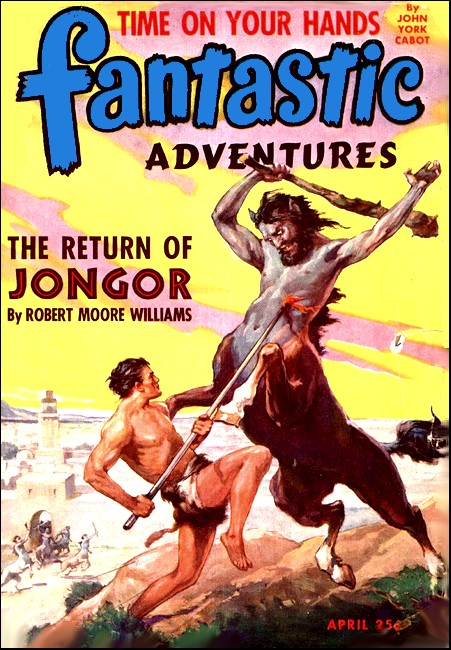

Fantastic Adventures, April 1944, with "Freddy Funks's Forgetful Elephant"

Truju fingered his lip and thought it over. "The best

thing to do," he told her, "is to send you to Chi-ca-go."

TRUJU, wrinkled by long years in the steaming jungle, sat cross-legged on a mahogany log and stared at Dora. Dora was all washed up. As an elephant, she was a hulking mass of wrinkled leather and broken heart. Dora sat on her haunches, small red eyes brimming with tears, trunk drooping pitifully.

Her ears flapped dejectedly at a passing fly and two tears overflowed and rolled down her trunk.

Together, Truju and Dora transported logs from the Rajah's jungle to his mill. Thus far they hadn't moved a log all morning. Dora just wasn't up to it.

Truju had considered the problem from every angle.

"You one sad elephant, huh?"

Dora nodded sadly. A fresh batch of tears welled up and a moan escaped her mouth.

"You like to see your boy friend in America?"

Dora's eyes brightened and the curling trunk moved up and down quickly. She trumpeted. It wasn't loud because, as nice as the trip sounded, she knew she didn't have a chance in the world of really going. It was just some more of Truju's peace talk.

Truju sat motionless for a long time.

"I got magic talk," he said at last. "I don't know much about America. They took Oscar to Chi-ca-go. You want to go to Chi-ca-go?"

Dora shifted her weight carefully and came to all four feet. She pushed her trunk out carefully and nosed Truju with it.

Truju smiled.

"You listen close now. Oscar say he go to a field. He call it field mu-see-um. You can find, in Chi-ca-go?"

Dora did a cumbersome little dance, lifted her trunk to the sky and trumpeted loudly.

"Good!" Truju leaned forward. "This afternoon you go to hunt in jungle with Rajah on back. I make magic spell now. When you deep in jungle, stomp earth three times and trumpet two times. You be in America."

Dora was overcome with joy as Truju continued:

"When ready to come home, do same thing. You can remember?"

Dora didn't even hear that. She was already, at least in spirit, entwining her beautiful trunk around Oscar's, and listening to affectionate little grunts from her boy friend.

IT was a bright, summer morning in Lincoln Park. Freddie Funk,

whistling an off-key rendition of Love in Bloom, left the

bus near a grove of trees, and started walking across the grass.

Freddie's mind was in tune with the morning. He had a commission

to do a landscape painting. Nice day, pleasant assignment, and

most important, more cash to support his ration points. Last week

he had thought he might have to eat the points themselves,

without gravy.

Mr. Funk found a pleasant spot close to the lagoon, put his materials on the grass and prepared for work. However, his luck was not to last.

While deep in the task of choosing a proper color of blue for the sky, he noticed the wind was growing stronger. He tried to ignore it, but found his own whistle dying in the approaching storm.

His first thought was to make a quick dash for the zoo, but the rain caught him before he could move. With an arm full of hurriedly gathered paints, and a heartful of hate for the Powers that be, Freddie Funk stood under a huge elm tree and watched the first rain drops hit the sod near him.

Then a startling think happened. The tree under which he stood seemed to change suddenly, and the foliage grew longer. The trunk became slimy and wet with moss. The sky darkened until he could hardly see beyond the clearing. He wiped the water from his eyes and tried not to notice that the grass was suddenly high enough to reach his knees and the clearing was entirely strange to him.

Then the air filled with a sound not entirely foreign to him. There came the high-pitched, trumpeting call of an elephant. It couldn't be coming from the elephant shed at the zoo. That was probably half a mile away. Perhaps one of them had escaped!

But no, the creature that emerged from the lush growth near the tree was a complete stranger. It had the meanest eyes Freddie Funk had ever seen.

The elephant walked slowly into the middle of the clearing. The wind went down as suddenly as it had arisen and the storm died, as though someone had turned off the supreme water tap. Freddie could see the grass shrink back into the ground and the tree return to normal. The park was the same and the sun was shining once more. Only one thing troubled him.

The elephant was still there.

The elephant stood very still, staring at Freddie. Freddie tried to fade into the tree, gave up, and waited, determined to die like a man.

The elephant stared for a minute, then settled back on its haunches and let its trunk droop to the ground.

Freddie Funk decided to make a run for it. He edged away from the tree and took a few steps toward the lagoon. The elephant opened its eyes a little wider, stood up and took two earth-shaking steps toward him. Mr. Funk froze in his tracks. The elephant came so close that its breathing was clearly audible to Freddie Funk. In Freddie's imagination the creature was about to pounce. He wondered if he were to die by being trampled on, or if the huge creature would swallow him alive and digest him at leisure.

With the first spell of horror gradually dwindling down to icy fear, Freddie noticed something about the beast that he hadn't been in condition to see before. On its back was a square boxlike thing with a canopy over it. A heavy leather strap circled the elephant's belly and held the box from falling off. Freddie thought he detected a gleam of reproach in the elephant's eye.

Was it possible that the mountain of Mesh was going to spare his life?

Freddie stood still and the elephant did likewise. No one came to Freddie's rescue.

DORA was puzzled by her first contact with Chi-ca-go. Truju

had been a good friend, but this strangely dressed, curly-topped

creature didn't seem to understand her. She winked one eye and

waved her trunk at him in a friendly gesture. The man turned in

panic and started to run. Dora wasn't going to lose the first

friend she had met in the new world. She juggled along behind him

like a pet dog, although with slightly larger proportions. She

nosed out a gentle trunk and wrapped it around Freddie's waist. A

horrible gurgle escaped Funk's lips. His arms and legs flashed in

the air. Dora stopped running, lifted him gentry to her broad

head and sat him down.

The contest was a draw. Both of them were puzzled. Freddie because he was still alive, and Dora because Freddie seemed afraid of her.

Freddie Funk looked down on the broad gray flanks and the twitching, eager trunk. It was plain enough that the animal had been trained. That she belonged either to a circus or the zoo.

He remembered something about an elephant's steering gear. If you kicked her on the right side of her head, she went in one direction and if on the left side, the other. He didn't remember which way she was supposed to go, but it didn't make much difference. One duty was clear to him. He must get the beast back to the zoo before it ran down and killed someone. In fact he was getting quite a heady feeling now at having escaped doom so neatly. He must have a power over animals. It wasn't just anyone who could handle an elephant as easily as he could.

"Giddap," Freddie said.

Dora shook her head a little.

"Start moving," Freddie commanded. "March—get into gear—move."

Dora failed to respond. Freddie pecked her gently on the side of the head with his heel. Dora went into motion slowly. She turned toward the south end of the park. She started to amble ahead slowly, swinging from side to side as she moved. Funk grasped a handful of her ear and held on. He wondered what he had ever seen in Dumbo that was funny. Right now elephants were far from being attractive or funny.

Dora had no particular goal in view. She was looking for a field, because Oscar would be in a mu-see-um field somewhere near the city. She was more anxious to see what America was like. The man on her head was a good companion. He just held onto one ear and was very little trouble to her.

THE cop at Michigan and Chicago turned around to whistle at

the south-bound traffic, put a white-gloved hand over his head

and started to wave. The whistle made no sound. His hand stayed

aloft and his eyes bulged.

"My God! Pachyderms!"

Coming down Michigan Avenue at a sedate speed was Dora, the elephant, with a very unhappy Freddie Funk perched atop her back. Freddie, unable to get down once Dora's journey started, had climbed to the comparative safety of the howdah and was bouncing from one side of it to the other. Behind Dora, stretched out as far as the cop could see, was a double line of traffic.

The cop turned around, ignored the traffic light, and placed both hands carefully on his hips. A snarl took possession of his lips and he became a man with a purpose in life. Dora moved up to the intersection, became a little timid about all the movement about her, and stopped in the center of the street.

"Well. Well." The cop was beginning to get his wind up. "If it isn't the Rajah of Evanston. Good morning, Rajah. And where might you be headed for?"

Freddie looked down the vast curve of Dora's flanks, smiled uncertainly, but made no move toward dismounting.

"I'm sorry, Officer," he said weakly. "I—that is—I can't seem to do anything about it."

"Maybe a traveling medicine show?" the cop said with smooth syrup of cyanide dripping from his tongue.

"And what are you selling, little man?" Freddie fidgeted.

"I can't get down," he wailed. "It isn't my elephant. The darned animal put me up here. I found her in the park."

"Well now, and ain't that nice." The cop's voice changed suddenly, to a domineering roar. "Well, you can take her back to the park and drop her right where you found her. I ain't having that pachyderm parked on my corner."

This conversation had taken a few moments; meanwhile small boys, and some who weren't so small, had gathered on all four corners. Traffic was snarled for blocks in all directions, and horns were adding to the general volume of noise.

Dora was nervous. All this was new to her, and although she was determined not to become frightened, her heart fluttered heavily. The man in the blue uniform was becoming nasty and she didn't like him. Dora pushed out a swinging trunk and nudged him gently. The cop lost his balance and went flat on his back. His face turned several strange and unpleasant colors and the sounds that came from his lips told Dora that he was displeased with her attention. A bit sorry for him, she curled her trunk around his middle and put him on his feet again.

Walter O'Reilly was a God-fearing, honest member of the police force. There was nothing in the regulations about the handling of elephants at intersections. It was also plain to him that the pale-faced, curly-headed chap on top of the beast was no better help than none at all.

Action would have to be taken—and fast. O'Reilly had lost what little dignity remained. He had but one course open. It was the call of the wild, the ultimate of ultimates in the police department. Adopting a swaggering pose, he howled at the top of his lungs:

"I arrest ye in the name of the law for everything in the book! Come along now, we're going to the station."

DORA remained motionless, her red eyes focused on O'Reilly.

Freddie Funk started to say something, then decided it would be

better unsaid. He climbed out of the howdah, took a long breath

and slid down Dora's side. He hit the pavement, fell, then picked

himself up.

"All right, Officer," he said. "I'm ready. Anything to get away from that—that monster."

O'Reilly had a problem. In fact, there seemed small chance of evading the problems that continued to arise with the minutes. The traffic was out of control now, so helplessly tied up that a special squad would have to come and unsnarl it. Irate citizens, themselves staying a careful distance away, were howling their lungs out for action.

"The elephant," O'Reilly said. "Get him out of the street, will you?"

He wanted to say please, but his dignity wouldn't stand for it.

Freddie grinned, but without humor.

"Couldn't we call the zoo, or something?"

O'Reilly moaned.

"It's your elephant, ain't it?"

"No!" Freddie shuddered. "It isn't. I can't help it if the thing insisted on giving me a ride."

O'Reilly was beyond anger. Inside him, a seething mass of indignation, horror and plain fear ran rampant.

"We gotta think this over." He went toward the curb and Freddie followed. It was as simple as that. Dora, seeing her friend walking away from her, followed Freddie from the street to the cool turf of the bit of park near the water tower. Automobiles started to flow forward again and O'Reilly sighed.

"Anyhow," he said, "she follows you. That oughta prove—"

"It doesn't prove anything," Freddie protested. "I don't own the elephant. I never saw it before. Now can I go?"

O'Reilly regained some of his strength.

"To the station," he said. "I'm calling the wagon right now."

DORA had some trouble following the wagon. She felt that it

was trying to escape her, and Freddie Funk, her closest friend,

was inside it. Dora heaved and bumped her tonnage along the

Street, trunk and rump swinging in unison. If Loop traffic was

tied up in knots and the two cops in the wagon were more than a

little disgruntled by their unwonted shadow, Dora didn't know

it.

The wagon pulled up at the police station. Freddie was whipped out of sight before Dora could catch up. She stood outside the station, leaning wearily against a lamp post. The crowd switched quickly to the opposite side of the street and Dora waited for Freddie to reappear.

The desk sergeant was faced with a situation unique in police history. He stared across the desk at a hushed, appreciative audience made up of two cops and a white-faced, bedraggled Freddie Funk.

"It don't belong to no one," he announced gravely. "I called the zoo and the circus. I even called the Field Museum. That elephant has gotta be yours."

"But it isn't," Freddie protested. "I told you before, I was in the park and it just—"

The sergeant waved an impatient hand to cut off Freddie's protests.

"We know," he said. "You'd think there wasn't any elephant. No one knows anything about it. No one owns it."

A light dawned in his eyes.

"Hey," he said suddenly. "This ain't a gag, is it? You guys ain't kidding all the time?"

There was breathless hope in his voice.

"Aw, Sarge, quit the kidding!"

"The elephant's real enough," the other cop said. "We left it outside when we—"

CRASH!

Proof! Proof everlasting, that would brand the desk sergeant for the remainder of his career.

The front of the station bulged in suddenly, and bricks showered from a two-foot area around the door. Both doors flew into the hall, glass shattered on stone; and Dora, carrying the sill around her neck like a wreath, heaved into sight.

"My Gawd!" the sergeant shouted.

"My very words," one of the blue-coats said, a little sarcastically. "Seeing is believing, eh Sarge?"

"THIS case is without precedent," the Judge said. "We have

checked every possible point to find out if an elephant has

escaped. It is necessary to assume that the pachyderm belongs to

you."

Freddie Funk sat alone in the small courtroom, head drooping rather pitifully, the weight of the world on his shoulders. A week had passed since Dora first walked into his life. She was waiting for him now, tied outside the court, a squad of fifteen policemen ranged around her.

"But it isn't mine," Freddie wailed for the thousandth time. "I was just standing there, minding my business."

"We know." The judge waved his hand. "However, possession, in this case, is the deciding factor. Young man, there is nothing to be gained by falsehood. Why don't you take your pet and go home?"

Freddie thought of the kitchenette apartment and Aquanis, his wife. A nice setting for an elephant!

"Home?"

The judge began to rustle papers on the bench.

"Young man, do you realize there's a war on. The zoo will not consider feeding the beast under present conditions. The museum is filled with elephant exhibits. They don't want to be troubled. You'd better find a home for the beast before it gets into further trouble. I can't promise you protection if this goes much farther."

His attitude was threatening. Freddie stood up. An elephant as a boarder. He didn't have enough ration points to feed Aquinas and himself.

Freddie left the courtroom with bowed head. What had he done to deserve such a fate? Outside, he went through the police squad, waited for Dora to lift him aboard and then held on tightly as Dora started to jog toward Michigan Boulevard. Where would he go? Where could any man, tied down for life to an elephant, go at a time like this? There was little hope of escaping his fate.

THE farmer, Ezra Wiggin, stared at Freddie Funk with

good-natured disbelief.

"An elephant? And what would I do with an elephant?"

Mr. Wiggins had twenty acres and a small house fifteen miles from the city. It had been a long trip. Dora was drinking the mud-puddle dry in Mr. Wiggin's farmyard.

"Wouldn't an elephant be good for hauling a plow, or something?" Freddie asked.

"I got a tractor."

Freddie considered that.

"It might break down," he said. "An elephant could drag the plow and the tractor both."

Wiggin guffawed.

"That don't make sense."

Freddie groaned.

"Look," he begged. "For two weeks nothing has made sense. I'll tell you what I'll do. You keep it here and feed it hay and—and stuff, and I'll pay you five dollars a week."

Mr. Wiggins did a little fast calculation.

"Nope," he shook his head. "That big galoot would eat five bucks worth of hay alone."

"Ten dollars," Freddie said, remembering his ration points.

Wiggin went into conference with himself.

"Might not be a bad idea," he agreed finally. "No monkey business, mind you. If that mountain of flesh gets into trouble just once, out it goes."

"Oh, but it won't," Freddie assured him. "I'll come out once a week; and besides, I hope to sell it pretty soon. The Field Museum is thinking about taking it."

Dora had risen from her mud wallow and walked within hearing distance of the two men. At the mention of the Field Museum her ears flapped once and lifted slightly. Her eyes brightened. At last she was getting a line on Oscar, her boy friend. Truju had told her he was in the mu-see-um field. Maybe they didn't say it that way here in America. The names sounded a lot alike.

She walked toward Freddie and nuzzled the tip of her trunk into his arm pit.

"See?" Freddie offered. "She's very gentle."

"Just the same," Wiggin insisted, "I'm chaining her to the barn. Can't be taking no chances."

Freddie hoped the barn was a strong one. He'd pay any amount to keep the beast away from him.

Almost feeling that the elephant could understand him, he turned to Dora.

"You're going to have a nice home with lots to eat," he pleaded. "Now, be good and stay put, will you?"

Dora's eyes twinkled.

"Don't you leave 'til we get her chained up," Wiggin ordered. "Darned if I ain't a fool even to consider—"

"Come on," Freddie interrupted hurriedly. "Where's that chain?"

FREDDIE FUNK was happy. At least, his mind know peace it had

not felt for weeks. The elephant was safe at Farmer Wiggin's

place and Freddie, seated comfortably in his thirty-nine coupe,

hummed toward home. The car hummed, that is, because Freddie

himself was, as usual, whistling an unreasonable facsimile of the

latest song hit.

Small worries take the place of large ones. Freddie noticed the gas tank was suffering pains from too little fuel. He spotted a station a quarter of a mile ahead, mentally checked his ration points and decided he could stand three gallons. Spinning the wheel, he drove in and got out of the coupe. An over-ailed attendant came out of the two-by-four building.

Freddie sought other places more necessary at the moment. When he returned, he found another car had come in for service.

The new arrivals were a tough-looking bunch. Four men, all resembling Funk's idea of Al Capone, sat patiently as the attendant filled their tank. Freddie, waiting to pay his bill, sauntered toward the other car.

Then it happened. The little spot of bad luck developed into a big one. One of the men poked an ugly snouted machine gun from the rear seat.

"Stick up the mitts."

Freddie hesitated, saw the attendant reach, and did likewise.

The front door opened and the driver got out. He was a tall, thick-lipped individual with wide, innocent eyes. He frisked Freddie and the station attendant. Freddie's pocket gave up four bucks, his last hold on the world of finance.

"Your dough inside?" the thick-lipped guy asked.

The attendant shook his head quickly, unable to bring forth verbal response.

Thick Lip went across the gravel and entered the station. He was busy for a minute over the cash register. He came out and approached Freddie.

"That your car?"

Freddie nodded.

Thick Lip turned calmly and filled the tires with lead. Then he re-entered his own car.

"Better not try to put in an alarm," he said. "I cut the phone wire."

Freddie, however, didn't hear this. Across the road there was a wooded area of about one acre in extent. Freddie Funk saw something among the trees that sent his heart spinning. The elephant, evidently escaped from Farmer Wiggin's place, was peeking slyly from the brush close to the road. It looked as big as a house, standing there in the shadows.

The man in the car was watching Freddie Funk. He turned, following Freddie's gaze. His mouth opened and he gulped down whatever he was going to say. One of the men in the rear seat turned and saw Dora's huge bulk.

"Elephants," he shouted. "Cripes—let's get out of here."

AFTER that, things happened too fast for Freddie. He knew that

a fist came out quickly and sent him spinning into the dirt. With

a loud, angry trumpet, Dora ambled swiftly out of the underbrush

and across the road. It had been only a few miles across pastures

from Wiggin's place. Now, with her friend Freddie in trouble, she

moved in. This was Dora's call to battle.

Freddie afterwards wondered why none of them shot her. It probably had been the complete surprise of it all. Not often do gangsters shoot elephants. Perhaps they didn't know a bullet would stop her.

Dora was across the pavement and beside the car in much faster time than she had ever made before. She snorted and fumed as she ran and her eyes were red with hate.

With a howl of fear the driver, Thick Lip, dove out of the car and started to run in the opposite direction. The others tried to follow, but they were too late. Dora slipped her trunk under the running board, felt for a hold and lifted. The car tipped upon one side and rolled over. The air was filled with screams of fear and protest. Freddie, partly dazed by the blow he had received, sat up a few feet away and watched the car crumple up as it rolled.

Then the attendant had one of the machine guns, and was lining up the crooks.

"Five hundred bucks," he was saying with a sob in his voice. "Jeez, mister, your elephant is a peach. That's all the dough I got in the world."

Thick Lip was gone, but his buddies were ready for the police. Freddie, still sitting on the ground, felt Dora's trunk go around him tenderly and she lifted him to her head. Freddie leaned over and patted her. Dora squealed and pushed her trunk into his hand. All was well in the world of Freddie Funk and Dora the elephant.

For how long? That, Funk thought, remained to be seen.

BECAUSE Dora had captured most of the notorious Crooked Cash

gang, the city council thought it ought to do something extra

noble about the whole thing. Freddie knew Thick Lip, the leader

of the crooked Cash outfit was still at large, and that he,

Freddie, was easy to find as long as Dora was with him. It would

do no good to worry. That Thick Lip would do something about

losing his buddies, Freddie never doubted. He lived in constant

fear that the gangster would hunt him down and murder him as soon

as he possibly could.

The city council voted that Dora should be allowed the freedom of the city streets so long as' Freddie kept her with him and allowed the elephant no private excursions. The city could stand the publicity, and Dora became Fighter, the Courageous Gangster-Hunting Pachyderm of Chicago.

The name gave her a spot in the limelight and included an appearance at Soldier Field. It also gave free rides to the Mayor's two children. Dora was on the front pages.

In spite of all this, she was unhappy. An elephant can get just so close to a man before one or the other has to do something about it. Dora's new home was in a deserted fire station outside the Loop, but the city stopped feeding her after the first pangs of public acclaim died down. The job fell on Freddie's weak pocketbook. All this, and Dora's constant company whenever he went out, troubled Freddie Funk deeply. Hence the trip to the Field Museum in the hope of a solution.

With Dora browsing around outside the Field Museum, Freddie Funk approached the office of Curator William Biggs, the man who had shown interest in Dora's hide. Biggs was a slim, dark-faced chap with a pump-handle nose and glasses to match. He accepted Freddie's hand as though it was a sacrificial object.

"Most happy, you know. Not every day a fellow brings in a real live pachyderm to sell. Unusual, quite."

"Thanks," Freddie offered. "I—I wonder if you're really interested in buying; that is, I want to get a decent, price, but I am anxious to get rid of the animal.

"Quite." Biggs nodded quickly, his eyes opening and closing each time his head wagged. "I'm not prepared to name a price. However, to state the facts with droll humor, we'll give the old girl a safe and everlasting home."

Freddie shuddered. He knew that they would kill the elephant, then use her bones and skin to mount a life-like figure of her in the elephant hall. In spite of himself, the thought gave him a shiver.

It hardly seemed fair

"It—it wouldn't hurt much, would it?" he asked suddenly.

"It won't hurt you a bit," Biggs said, then laughed at his own high humor. "It might, that is, cause some inconvenience to the elephant. After all, she wouldn't be able to move around much, stuffed."

Freddie shuddered, trying to pass over the subject lightly.

"You'd be willing to pay...?"

"For the time being I can't discuss—"

BANG! CRASH!

Freddie whirled around sharply; and Biggs, after collecting his wits, stared toward the outer doors with wide eyes and a bobbing Adam's apple.

"I say—this isn't allowed; not a live elephant."

Dora didn't care what was allowed. She stood in the middle of the main ball, part of two swinging doors draped around her head, a frightened attendant hanging in her trunk.

Dora had found Oscar!

SHE was a little angry at Freddie Funk. She had been waiting

outside for some time when a couple of women, passing her,

mentioned they were going directly to the Field Museum. Dora's

mind turned over in crazy flip-flops and she knew that the Field

Museum wasn't a field at all, but a huge building.

If Oscar was here, she was going to find him.

The doors had been difficult but she managed to push through. The attendant had tried to shoo her away, so she carried him along with her. Now, her trunk high in the air, Dora saw Oscar standing at the far end of the hall, a magnificent specimen of leathery brown.

With him were several other gentlemen elephants and a couple of frowsy females.

Dora heard Freddie shout at her; but Freddie had brought her here without letting her know what was inside. She failed to consider that Freddie knew nothing of her love. Freddie was shouting louder and waving his arms.

Dora ambled quickly down the hall to Oscar's side and started to rub her thick hide against his.

People were gathered at the head of the marble stairs and in the lobby. No one seemed to know what to do.

To Dora's surprise, Oscar was very cold and stiff. He paid no attention to her. She reached up tenderly and wrapped her trunk around his. Oscar remained still and disinterested. Dora made little love noises in her throat but her boy friend seemed intent on ignoring her.

Dora became angry. Perhaps the frowsy females who stood near him had turned Oscar's head. Dora trumpeted savagely and started to shuffle around the big hall. Nothing she could do would bring Oscar's mighty head down to her level.

In a sudden fit of anger, she wrapped her trunk around his, and jerked. A horrible rumble came from beneath them and Oscar, weighing no more than a third of what he used to, tipped over and crashed to the floor. Dora backed away.

Oscar was dead. There was no doubt about that. Stretched full length on the marble floor, he retained the same stiff appearance. Dora lifted her trunk to the sky and trumpeted her grief. The museum echoed like a lonely tomb. Then Dora, head down, turned and shuffled slowly toward the door. Her red eyes were overflowing with tears. She saw and heard nothing. Once outside, she moved swiftly across Grant Park toward the north.

IN a little grove of trees near the north end of Lincoln Park,

Freddie Funk sat with knees drawn up under his chin. He was still

for a long time, back against a tree, staring at the

broken-hearted elephant opposite him.

Freddie has followed Dora to their first meeting place. Dora was sitting on her haunches, trunk hanging before her without a quiver left in it, tears streaming down her trunk.

"I—I guess you used to love that elephant at the museum?" Freddie said.

Dora nodded her head from side to side. Love Oscar? What had they done to him? She wished she had stayed at home with Truju. That she had never found out about Oscar.

"I'm sorry," Freddie said. "You and I get along all right. I hope you're not mad at me?"

Dora thought that over, then shook her head. Freddie wasn't to blame. He'd been a good pal all along.

"What I'd like to know," Freddie went on, "is where the heck did you come from. You aren't like any elephant I ever saw. I know darn well you understand everything I say."

Dora nodded again, and a fresh outburst of tears started.

"Aw, cut it out," Freddie Funk pleaded. "That won't help. You oughta go back where you came from and forget all this."

Dora's eyes brightened. Now that wasn't a bad idea. Truju said all she had to do was—

Suddenly a shudder coursed through her body.

What had Truju said? What was the magic spell?

Dora had forgotten. Truju said all she had to do was—

No use. She couldn't remember a bit of it. A fresh torrent of tears started.

She was in America, Oscar was dead; and she had no way of going home again. Freddie Funk seemed to understand that she was lonely and bewildered. He stood up and put his arm around her trunk.

"Take it easy," he urged. "Everything will work out all right."

But would it? Funk was frightened. Thick Lip, the escaped leader of the Crooked Cash gang, was on the prowl. Twice, late at night, Freddie had ducked into doors just in time to avoid a strange car that hurtled past him with guns poked through the windows.

The museum was threatening to sue for the damage Dora had done and Freddie wondered what he would use for money if they really got tough. The novelty of having an elephant running around the town was beginning to wear off for the city council. Discussions were under way about the probable market for elephant steaks to help relieve the meat shortage.

Dora was beginning to get irritable.

EVERY night she insisted on revisiting the grove at Lincoln

Park. There she would sit for a full hour, nodding her head back

and forth eagerly, eyes suddenly bright, then fading again as she

failed to revive a poor memory.

She thought of every possible magic word Truju ever used, then gave it all up as a bad job. Who the hell said elephants never forget? There couldn't be more than one or two magic words, and still she couldn't think of them.

Dora started to lose weight, Freddie lost confidence and the city council was losing patience. The peanut market in Chicago was losing most of its natural resources. Dora had to eat.

Thick Lip was out, once and for all, to get Freddie Funk. This time Thick Lip left his gang behind. He armed himself with a rod and followed the elephant and her keeper on one of their nightly trips to the park. It was close to nine in the evening.

Freddie had gone through the usual dozing spell and Dora had once more sobbed her eyes out. The problem was too deep for her.

Thick Lip was no fool. He planned to shoot Funk from behind the tree against which Freddie leaned, make a run for it and escape the elephant in the darkness. All might have gone well if the moon hadn't figured into the hand.

Freddie, arising from his post, approached Dora and started to lead her away. Thick Lip aimed the gun carefully, but the moon sent a beam of light rippling down the barrel of his gun. Dora caught the flash of light, saw the twisted face above it and pushed Freddie to one side roughly.

The gun cracked, and the bullet buried itself in Dora's thick hide. It didn't hurt much, but the sting and the sight of the man who had once before attacked her friend, sent Dora on a rampage.

Thick Lip saw his mistake almost at once, but it was too late.

Dora went into action. She was around the tree and after Thick Lip with one long, very ungraceful bound. Dora could cover a lot of ground when she had to.

This time her anger was a terrible thing. She played with the gangster as though he were a rag doll. Thick Lip lived only during the first bounce, but Dora kept right on playing ball with him until there wasn't enough left to throw.

She felt alive and vibrant again. This was more like it. Life had lost its excitement and now she was recapturing some of it. After a while, things were very quiet. No spectators showed up and she lost interest. Freddie had managed to get to his feet and was leaning against a tree, eyes wide with horrified interest.

Feeling that a battle cry of victory was in order, Dora turned and started pawing the ground, her trunk lifted toward the sky.

Then destiny played its part.

She lifted her right foot and brought it down sharply three times. She trumpeted loudly, just twice. Three trumpets and two foot-falls would have left her in Chicago. The ratio, however, was as Truju had outlined it. Dora had, by a strange error, hit on the magic formula.

The moon sank out of sight behind a cloud and the wind was suddenly hushed. Then from nowhere, a hot rushing storm came up. The trees bent double. Freddie Funk, holding tightly to the tree closest him, felt the bark change under his fingers. He looked upward and saw that he was holding the trunk of a giant fig tree. Grass had sprung up around his knees. He closed his eyes and started to pray.

Then the wind was gone. Freddie opened his eyes slowly. The park was the same. The moon was out again and the turf was smooth and green under his feet.

Dora and Thick Lip were both gone.

Freddie sat down limply, understanding little of what had happened. One thing he was sure of. His worries were over.

OUT were they?

Two days later, his apartment phone rang. "This is Mr. Wiggin calling," said a voice at the other end of the wire. "I still got that box thing we took off your elephant when you left her here at my farm."

"Oh." Freddie Funk wondered if he'd ever hear the last of Dora. "You mean the howdah. Couldn't you use it for firewood, or something?"

Mr. Wiggin grunted.

"I got enough wood," he said grumpily. "Besides, it's mostly padded cloth. No good to me. I'll bring it in on my next trip to town."

Freddie groaned.

"But—but I haven't the slightest use for it."

"Can't help that," Wiggin retorted. "I got no right to keep another man's property. You'll have it back in a day or two."

"But—"

The receiver clicked in Freddie's ear.

Freddie Funk put the phone down with a bang. He thought things over for a moment, then shrugged.

"No use trying to keep a thing that size in this apartment," he told himself. "When Wiggin delivers it, I'll chop it to pieces and let the janitor burn it."

DORA was quite happy. Only one thing marred her pleasure:

Truju was lecturing her again.

"You a bad elephant, Dora!" Truju regarded her gravely from his seat on the mahogany log. "First you forget how to come back, then you forget to bring the Rajah's howdah with you. The Rajah say he like to kill you."

Dora heard only about every third word. She found herself missing Freddie Funk. She wished she had brought him home to India with her.

"That howdah one good thing, Dora," Truju went on. "The Rajah say he put hundred fine rubies in lining so he have mad-money when he get too far from home. Them rubies make any man rich, Dora."

Dora's eyes brightened and the last traces of tears left them. So Freddie had his reward after all. Maybe everything was for the best. She had never been cut out for city life. She had saved Freddie from being killed, and had left him rubies to make him a rich man.

"Elephants supposed to have good memory." Truju waggled a lean finger at her. "I maybe whip you for being bad elephant."

Dora pushed her trunk into a nearby pool of water, sucked up a trunkful and gravely squirted it into Truju's face.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.