RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on detail from a public-domain wallpaper

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on detail from a public-domain wallpaper

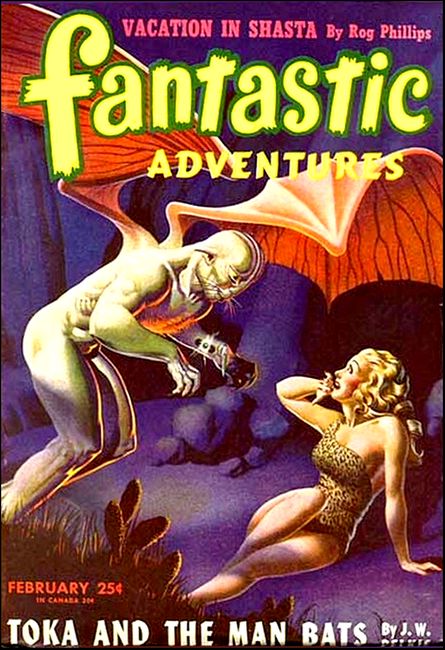

Fantastic Adventures, February 1946, with "Moon Slave"

I STOOD near Minister Niles, watching as they lowered Lawrence Rancin's coffin into the black, rich earth of the New England graveyard. Nick Fan-ton, the minister, and I were the only mourners present. None of Lawrence Rancin's friends had come. They hadn't time. Evelyn, his lovely, rather spoiled wife, was too overcome with grief at the last moment to come to the cemetery. The moon, full and cold with disinterest, lighted the spot. It glinted on the shovel as Sam Peevis removed the funeral trappings and started slowly to fill in the grave.

Yes, I said the moon; for we were burying Lawrence Rancin at night, on the very night he had died, and by his own request.

None of us was very keen about the idea; but being the only one at Lawrence's death bed, I had listened to him gasp out those last wards, and felt it my duty to see that his wish was granted.

The grave was filling slowly, and the cement box that held the coffin and all that remained of Rancin, had disappeared from sight. I felt the minister's hand on my arm and it startled me. I guess I drew away from him quite suddenly, because he cleared his throat and spoke in a low voice.

"Don't you think we can leave now?"

I managed a smile, because I didn't want him to know how I felt just then.

"You go back," I said. "Nick and I promised to stay."

I looked across at Nick Fanton's pale face and saw him nod. Minister Niles turned without a word, kept his eyes down-cast on the moon-lighted gravel road and walked toward town. The steady "clump-clump" of falling clods, and his footsteps against the gravel were the only sounds in the graveyard. Then the grave was filled. Sam Peevis tapped it down neatly, wiped his shovel on a piece of burlap and looked at us questioningly.

"Here, Sam," Nick said. "Go down to town and warm your stomach with a few bottles of ale."

It was the first time he had spoken since we came. Sam Peevis grinned nervously and accepted the five-spot. He pushed it deep into his pocket.

"Thank you, sir," he said. "I believe I'll do that very thing."

His feet beat a tattoo on the gravel, and I knew why he was in such a hurry. It wasn't tike Sam Peevis to fear a place in which he had spent most of his life. Tonight was different, however. Sam Peevis wanted to see the lights of town again, and forget what had caused this bit of midnight business.

Nick and I just stood there and looked at each other. Then he stared down at the freshly filled grave.

"I guess that's all we can do," he said. "Let's get out of here."

He started to jump the grave, then thought better of it, circled the mound and took my arm.

I felt suddenly savage. "It wasn't right, Nick. Larry was a decent guy. He didn't deserve..."

He didn't interrupt me. I got control of myself and shut up. It was better that way.

At the entrance of the graveyard we stopped and looked back through the thick, interlacing branches of the giant elm trees at the lonely spot we had just left.

"Maybe he's better off," Nick said. "He was completely, hopelessly lost."

LARRY RANCIN had been a happily married man of thirty. His

banking business in New York went smoothly enough. His wife,

Evelyn, was the most attractive woman on the Bay. Yet Rancin had

seen the vision of Cory Rock and gone mad over her.

I have seen her also. Sometimes, when the moon is bright, you can stand at the point and see her out there, sitting on the rock, the waves lashing up angrily at her. She sits there, afraid of nothing, her long wavy hair touched by moon silver and blowing in the wind.

Sometimes she seems to be without clothing, and sometimes the moon weaves tiny half moons about her, that form a dancing, jewel-like setting about her hair and her waist.

Men have seen her dive cleanly into the water and disappear, not to be seen again for many nights.

I can't deny that she affects you strongly. Whether she was an illusion, or some wild, lovely child of the coast, I didn't know. I didn't care. That first night on Rigger's Bay, I had to fight every nerve inside me to prevent myself from diving into the water and swimming to her.

Lawrence Rancin saw the girl also. He must have, because his lips formed two words before he died, and I knew who he was talking about. In the evening we dragged his half-dead body from the water below the cliff.

His arms and legs were torn and crushed by the force of the sea. A sea that pounds relentlessly against the high rocks. We carried him up to the Fanton house and called the doctor, and his wife, Evelyn. Oddly, Evelyn seemed angry. She refused to watch his burial. I remember those last two words, whispered to me in the lamplight while he turned his head restlessly and stared out at the sea. Those fatal words that were to mean everything—and nothing—in the days to come.

"Moon Slave..."

FANTON'S place was a sturdy, clap-boarded old New England house.

It had several bedrooms, all fitted with Mother Fanton's comforters

and patchwork quilts. Downstairs, there was a rugged, scrubbed kitchen

with a pump at the end of the sink that brought water from the cistern,

a dining room that often in the old days sat a dozen sea captains, a

couple of small rooms that Nick and I used for summer offices, and the

huge "sitting" room.

We were sitting in that last room now. Nick stretched across a big easy chair, his head hanging down over the arm, staring at the ceiling. Jean Fanton stood near the fireplace, where she had just placed a log on the flames and was brushing her hands on an old pair of blue corduroys. George Fanton, the father of Nick and Jean, sat by the window, staring out at the white capped bay.

"Now look here, Lee Judson," Jean said sharply, "you may as well stop brooding over something that you can't help, and snap out of it."

I looked up quickly and realized that I must be acting like a genuine sour-puss. I had let Ranch's death affect me pretty strongly, not so much because we were friends, but because of the strange reference he had made to the phantom girl of Cory Rock. I had said nothing to them about it, and the secret, or at least I considered it one, was getting the best of me. I stood up.

"Sorry," I said. "I came up here for two weeks of peace and rest. Feel like taking a walk?"

Jean crossed the room and stared up at me. I must admit that any memories of Rancin fled at that moment. Jean is one of those clean-featured, bronzed natives of the coast. Slight of figure, her brown eyes, chestnut hair and clever collection of curves, pack a terrific wallop. I, Lee Judson, was in the fortunate position of holding an option on this charm, and I had no intention of letting the option run out. We planned to get married just as soon as Uncle Sam could decide whether he needed me most in a law office or in a uniform. As most of my cases were rather important from the Navy's standpoint, I figured on a fifty-fifty chance of remaining before a jury box.

"Let's go out on the Point," Jean said. "The sun is so bright, we can probably see across to town."

Town, Ray ford Village, lay five miles straight across the bay from Rigger's Point. It was a pretty sight on a clear day, but as we had just dragged Rancin's body out of the Bay last evening, the place didn't appeal to me.

I guess my expression must have indicated this, as she grabbed my arm hurriedly.

"All right, sour face," she said. "We'll take the road to town and come back past Evelyn Rancin's house. Someone has to cheer her up."

Her father cleared his throat hurriedly, and I knew he didn't approve of Evelyn Rancin. Few old timers did. Jean was ready with a come-back.

"You go back to sleep, you old seal," she said. "I'll take care of little Jean. Evelyn Rancin won't contaminate your pure daughter."

As this seemed to be the extent of the spirit of revolt, we left Nick staring at the flowered wallpaper on the ceiling and walked down to the road. We had gone half a mile along the dusty pike before I gained courage to tell Jean of Lawrence Rancin's reference to the Moon Slave.

When I had finished, she stared straight ahead for some time. Then, without looking directly at me, she said:

"Is that all he told you?"

I nodded.

"Ever hear the vision of Cory Rock called a Moon Slave before?" I asked, trying to sound bright and in a conversational mood.

She shook her head.

"Lee, did you know that Lawrence Rancin isn't the first man who has jumped from the Point?"

"I've heard of others," I said guardedly, "but I never knew them personally or saw them."

She slowed down a bit, talking quite earnestly,

"There have been seven in all," she said. "Over a period of nine years, seven young men have gone to their death from Rigger's Point. In each case, the old timers claimed that the man was trying to reach the vision he saw out there. It's—it's sort of a fairy tale, like the one about the seaman who wrecked their ships centuries ago, to follow sirens and mermaids. It gives me the shivers."

That was putting it mildly, and I started to gain a new respect for Jean's intelligence. She had thought more of Rancin's death than she confessed in public.

A BUGGY appeared on the road, coming in our direction. It was

moving fast, sending spurts of dust into the air behind it. It

could see the black frocked figure of Minister Niles standing up,

hurrying his mare with quick, deft flicks of the whip.

We stepped from the road until he could pass, but he saw us and halted. There was perspiration on his face, and a cold, gray look of fear about his mouth.

"Judson, I'm glad you were coming to town."

I held the mare while he climbed down, and said "hello" to Jean. Then he turned once more to me.

"Judson," he said again, "you said that Rancin made a specific request that he be buried by moonlight, and on the night of his death?"

I nodded, wondering what he was leading up to. He said no more, staring first at Jean and then myself. Finally he swallowed.

"I don't understand it, Jerusalem, but I don't."

Jerusalem was Minister Nile's closest approach to a curse and he used it only when over-excited or badly confused.

"Just what don't you understand, Mr. Niles?" Jean asked. "Don't keep us in the dark."

"Last night," Niles said, "after we left the graveyard, Sam Peevis went back past it on his way home. Sam may have been drunk, because someone gave him money and he spent an hour at the tavern."

He looked accusingly at me, but I didn't betray where the money had come from.

"Sam says he saw a woman in the graveyard. He saw her hair and it was down about her neck, so unless he was drunk, he couldn't have been mistaken."

"Why all the excitement over Peevis' story?" I asked a little angrily. "Perhaps Evelyn Rancin went there herself, to grieve at the grave of her husband."

Niles' face grew grim.

"If she did," he said, "she's in trouble. This morning when Sam went over to remove the funeral equipment, the grave was open."

His breathing was hard.

"Lawrence Rancin's body is missing."

I could think of nothing to say. I wished that Jean wasn't there. That she hadn't heard what was said.

"Gone?"

She mumbled that one word, as though in a trance. Her face was cleansed of all color.

Niles nodded vigorously.

"The coffin was open. Nothing in it but the carnation Evelyn had put in his button-hole."

"I think I better go back to town with you," I said. "Jean, will you go back to the house and wait?"

She answered me by climbing into the buggy.

"You and I started out together," she said quietly, "and I'm not going back alone."

There was nothing to be gained by argument now. I held the mare while Niles climbed in stiffly beside Jean. Then I took the reins and guided the buggy in a U-turn. It was after we turned and were well on the way to town that I saw it. Saw Jean's hands, resting together on her lap. The nails were long and usually wore a deep, red polish.

Now they were cleansed of polish, and under the tips was black, rich dirt.

I tried to keep my eyes on the road, but a strange premonition of danger swept over me.

Jean hadn't gone to the funeral last night. She said she went to her room early. The corduroy trousers which were worn in the garden, and on our many hikes, were smootched with the soil of Rigger's Point.

I swore softly at myself for doing it, but I couldn't prevent my eyes from straying to those pants, studying them carefully.

Below the right knee, a line of dark dirt impregnated the corduroy fabric. Dirt that was never found at Rigger's Point.

A fear grew inside me. A fear for my own sanity.

Once more I looked at the fingernails. Then I brought the whip down sharply on Minister Niles' mare. The sudden, savage gesture startled them both, as I was usually gentle with animals.

"Lee," Jean said sharply. "What's wrong with you?"

"I was just wondering," I said, "if there is any connection between Lawrence Rancin's request to be buried at night, and the Moon Slave on Cory Rock."

Neither of them answered, and it was a silent, bewildered little group that continued to ride hurriedly toward Rayford Village.

When I looked again, Jean's hands were thrust deep into the pockets of her trousers.

I wondered if those hands had dug into the soft, death-filled earth of Ray-ford Graveyard.

WE ACCOMPLISHED nothing that day. The entire village of

Rayford was stirred to hysteria by the mysteriously robbed grave.

Men, already sworn in as special deputies, were roving the

countryside looking for some trace of the body, or a trail left

by the ghoul. Someone notified Nick Fanton, and he came in early

in the afternoon, threatened Jean with sudden death if she did

not return home, and joined the search at my side.

The search was foolish and we knew it. Whoever stole Lawrence Rancin's body did it with a clear-cut purpose in mind. It wasn't likely that the ghoul would drop the corpse behind some bush or along a lonely path. Still, the task of searching out every nook and cranny provided the townspeople with some outlet for their emotions.

Evening came, and Nick and myself returned to the town tavern to refresh ourselves after a hot afternoon. We learned from Minister Niles that Evelyn Rancin had been notified. In fact, the minister himself had made a discreet search of the Rancin house; not, he assured us, in a suspicious manner. He had just "looked around" without arousing Evelyn's suspicions. Evelyn was quite the most shocked person alive, he said, and he could place none of the guilt upon her shoulders.

I was thinking of this when Nick and I sat at the scarred oak table near the rear of Barr's Tavern. It seemed evident, almost shockingly evident to me, that Jean must in some manner be involved. It could have been she who was seen last night. After Nick and I returned from the burial, Jean did not appear. I had seen her again this morning, and at that time, rich dirt was still visible under her nails. It wasn't like Jean to be careless or slovenly in the care of her body. Perhaps she was still under a terrific strain....

I wonder why suspicion should grow so swiftly against a person you hold closer than any other in the world? Sometimes that is so. You want so completely to trust them, and yet they are the first to be condemned if anything goes wrong.

I knew that Evelyn and Jean were old friends. Evelyn Rancin was a little wild, and she paid no attention to tongue-waggling in the village. Ray-ford is a quiet place and it was always picking on the one or two "fast" women, who are supposed to be bad medicine for anyone else to associate with. Perhaps Evelyn Rancin wasn't as bad as she was pictured, but the elderly members of Rayford Village drew a scarlet circle around her and wouldn't venture inside with anything but their gossiping tongues.

I wondered what Jean's habits were, when I wasn't at Rayford. It had been three weeks since I last journeyed up from New York.

"Nick," I said suddenly. "What's your idea about all this?"

Nick Fanton, Jean's younger brother, is a curly-headed, handsome loafer with a spark of genius in him and lights to a flame any time he really applies himself to hard work. He seldom does it, but when money is scarce in the Fanton home, Nick goes to work on some new idea and puts the family on easy street. Nick thinks as he talks—slowly, and only when necessary. He finished sipping his glass of ale, placed the empty glass on the table and leaned back in his chair.

"I've got sore feet from hiking over every by-way within five miles of town," he said. "Why don't we stop kidding ourselves? Why don't we do a little grave digging of our own?"

I'LL admit that the suggestion, given casually, caught me

entirely off guard. Nick wasn't anyone's fool, and he had

approached the problem much as I had.

"You think there might be some connection between last night's episode and the others?"

He didn't answer directly. He stared straight into my eyes, and for the first time in a month, he looked sober, deadly serious.

"Don't you?"

I nodded.

"Rancin asked to be buried at once, the very night he died," I said. "I don't know what happened to the other men who died in the sea because of the vision of Cory Rock, but I'd like to find out."

He nodded and stood up.

"Come on," he said.

I remembered Jean's discussion. Remembered that seven men had died near Cory Rock. I followed Nick into the street and we walked swiftly toward the edge of town, up toward the graveyard. I said:

"Nick—who was the last victim, before Lawrence Rancin died?"

"Fred Fletcher," he answered. "Fletcher was a pal of mine. He used to sit out there on the Point every night, staring out to sea. I told him to stay away. He laughed and said he was interested in the vision of the girl only from a scientific point of view. Wondered what caused the phenomenon."

"Well?"

He was still walking steadily but I managed to catch up to him and take my place at his side. I could see that his face was very red. Anger stirred deep within Nick Fanton that night.

"He was a damned liar," he said abruptly. "Fletcher was in love with that vision. One night she must have called, for he stood up and jumped a hundred feet to his death against the rocks. I helped carry what was left up the path to town."

We were beyond the last house now, and Sam Peevis' place stood dim and black, far ahead. We reached the dark, neat square of Peevis' house and Nick knocked sharply on the door. Several seconds passed and a lamp flickered and grew strong on the kitchen table. Sam came to the door in his night shirt.

"I've got a job for you, Sam," Nick said. "It calls for some night work, and a little extra cash in your pockets."

Sam stood very still, holding the lamp high, studying us. He shrugged.

"Rayford is a pretty healthy place these days," he said. "Not many dead 'uns to tuck in. I can use the money. Hold on a jiffy."

We waited while he went back inside and shuffled around the room. Then he came out, picked up a heavy spade that stood by the door and started toward the gate.

He seemed to know what he was wanted for, and yet we hadn't mentioned anything to him. I looked at Nick. Nick grinned back at me and winked.

"I guess Sam isn't the strictly upright citizen we sometimes think," he said and followed the grave digger across the yard and in among the graves.

We had gone perhaps twenty yards when Sam Peevis stopped and turned around to wait.

"Which 'un we diggin' up?" he asked casually.

That was a little too much for me to take straight. This was a new business to me, and not an entirely pleasant one. I'm old fashioned enough to feel a certain horror in disturbing the remains of the dead.

"Look here," I said a little sharply. "What makes you think—?"

"Stow it," Nick Fanton said sharply. "He knows what we're after and there's no use concealing it. Sam, we want to see the inside of Fred Fletcher's coffin. We were both a little surprised that you were ready to go graveyard sightseeing. Isn't this idea rather novel, or do you make a habit of such midnight visits?"

Sam Peevis grinned.

"They's no accounting for tastes," he said. "For me, ale wets my tongue and my conscience. If the pay is good, any job is easy."

I wasn't satisfied, and I was a little disgusted with Nick Fanton's approach to the problem.

At least, we were accomplishing something and that was what we came here for.

SAM PEEVIS found Fletcher's grave easily, and though the grass

was beginning to choke the headstone, after cutting the sod away

carefully, he worked swiftly downward until his spade hit the top

of the casket. The graveyard was dark tonight, and the moon

didn't shine. Somehow I was thankful for that, although the

shadows weren't exactly reassuring. I had grown to hate the moon,

and regard it as a huge, staring eye of death. I welcomed its

absence. I heard Sam Peevis grunting and swearing over the

casket, and at last the wrenching, hollow sound as the lid came

loose. Nick Fanton stepped to the edge of the grave and shot the

spot of his flashlight downward. He didn't speak, but I heard him

take a quick, hard breath. Sam Peevis was climbing clumsily out

of the grave. Nick turned to me.

He handed me the light and without a word, waited for me to look. I took a deep breath and stepped to a vantage point where I could look down at what lay below. I pressed the switch on the flashlight.

"Damn ..."

I heard Nick at my side. We were both silent after that. We were right. The coffin, its white satin interior dulled and spotted with age, was empty. There was no sign that the body of a man had ever disturbed the smooth cushions.

"Peevis," Nick said.

Peevis had climbed entirely out of the grave now and stood away from us, his mouth foolishly open, staring in our direction. At the sound of Nick's voice, he stepped toward us eagerly.

"Look here, you two," he said. "I don't know what you're up to. I ain't never dug up no grave like that before. Sometimes I stole rings and things outa them for people, but stiffs can't use rings anyhow. I never stole no bodies."

His voice was alarmingly high-pitched and frightened.

We had placed ourselves in a bad spot. If anyone should come this way and discover us over an empty grave, we would be in a position that no amount of explaining could get us out of.

Nick Fanton was thinking quickly, and I guess a little more clearly than I.

"We're getting out of here," he said. "When we're gone, you make sure that our footsteps and your own are covered. Then you go home and leave the grave open. Keep your mouth shut and we'll all be safe; open it and I'll put you on the spot that won't be healthy for your peace of mind, understand?"

Sam Peevis wasn't too intelligent, but he recognized a bad spot when he was in it. He probably reasoned as we did. An empty grave had been found this morning and it hadn't been blamed on him. Therefore, why should he spend sleepless hours over this one.

"Give me my money," he said gruffly. "I'll do like you say."

The transaction was made hurriedly and we left him there in the darkness, muttering to himself and scrapping fresh dirt over our deeply imprinted shoe marks.

On the road, we avoided the village and went straight up the Bay pike toward home. Neither of us spoke for a long time. We were wondering if all those seven graves had been robbed. If every man who died for the Moon Slave had deserted his grave for some mysterious mission.

"THE more I think about it," Nick Fanton said savagely, "the

more I'm inclined to blame the whole damned business on Evelyn

Rancin."

Together we had left the house early in the morning, detoured from the road through the swamp that surrounded the Rancin place, and were now seated in an open glade, the sun beating warmly upon us, our backs pressed to a pair of dwarfed cedars.

There was no doubt in our minds that by this time the second empty grave had been discovered. Whoever was responsible, would be on guard from now on. We had to strike soon, and strike before we ourselves were in danger.

"Evelyn could easily be responsible," I agreed. "But why should she have murdered her own husband? Larry wasn't any God's gift to women, but he thought a lot of Evelyn in his own way. He'd have killed himself if she asked such a sacrifice of him."

Nick nodded.

"I know," he admitted. "Yet Evelyn has had a mysterious, will-o-the-wisp reputation since she came here. No one ever sees her come and go."

He stopped abruptly, and stared at me.

"Lee," he asked almost wistfully. "Have you ever seen the vision of Cory Rock?"

The question gave me a start. Nick was usually such a matter of fact person. I knew from the way he spoke that he had not only seen the Moon Slave, but had been as captivated by her as I was.

"Yes," I admitted slowly. "I heard so much about her that one night I sat on the point above the cliff and waited for her. It was stormy, but after a while the moon came out and there she was, sitting out there on a ledge, above the waves. Water broke over her but she didn't seem to notice it. She was the most perfect creature I've ever seen."

He seemed to be thinking. At last he nodded, as though answering his own question.

"Doesn't it strike you odd that a woman could possibly swim that wild stretch of water between the rock and the beach under the cliff? That's one of the most treacherous death holes along the entire coast."

I was aware of that. I had often wondered. Still, Evelyn Rancin had lived along the coast all her life. She had taken medals at every swimming meet held at the village.

A lump arose in my throat as I remembered that Jean had competed in those swimming meets also. That Jean's slim form could cut the water, smooth or rough, with an easy breast stroke that defied description.

Nick was still waiting for me to answer.

"Are we sure that this is a woman," I asked. "Couldn't it be some weird devilish phenomenon of the sea that has no existence in fact?"

"You forget," he said dryly, "that men are missing from their graves. That was no trick of the eye."

He stood up.

"We are going to see Evelyn Rancin," he said. "I think she has some answers that will prove interesting."

EVELYN RANCIN had refused to leave the low, stone house when

her husband was buried. She had locked the oak doors and burned a

candle in the window, as though hoping that some trick of fate

would bring him home. Her eyes were dry when she greeted us at

the door-, but I knew that she was badly shaken.

"Nick—Lee," she said. "Come in. I've been wondering when someone would come over." She shuddered. "Someone human, that is."

I remembered Minister Niles' visit of the day before, and knew how badly she hated the stiff, sanctimonious old man.

We went in and Nick draped himself over an easy chair in the small, warmly decorated parlor. I sat down on the piano bench and Evelyn sat opposite me. She reached out and touched my hand.

"Lee," she said. "I guess I was a fool not to come for the funeral. Since Larry's body has been missing, they all point at me as though I stole it myself."

Her fingers touched the back of my hand. I looked into her eyes. They were brown and deep and moist, and I realized that the feeling I had had for her years ago still lived somewhere down deep inside. She might be frightened and stirred badly by what had happened. It didn't erase entirely the smoothness of her poise. Evelyn Rancin still had the power to make men curl up inside and feel grateful for being allowed to share her emotions.

"Matter of fact," Nick Fanton said slowly. "We came over to talk about the body. You didn't steal it, did you?"

Evelyn's hand darted away from mine and for a moment, touched the bodice of her gown above her heart. Then she clasped both hands in her lap. Her face turned very pale.

"That wasn't exactly a clever thing to say, Nick," I said. "We've been Evelyn's friends for a long time. There's no point in making it tougher for her now."

He sat up in the chair, a rather cruel smile on his lips.

"Why beat around the bush?" he asked. "If Evelyn is innocent, she shouldn't feel hurt."

Evelyn Rancin stood up. Suddenly her eyes were blazing with anger, and I didn't blame her.

"You get the hell out of here, Nick Fanton!" she said wildly. "I've taken it from every direction. I might have known you'd be no different."

Nick stood up lazily. He tossed his head, sending a stray curl back into place. He stared toward the door.

"You coming, Lee?" he asked.

I didn't like the ugly implication in his voice. My fists were clenched at my sides.

"No," I said. "I'm staying. I came to talk with Evelyn Rancin, not to crucify her."

He stopped at the door, and turned to grin at us.

"Plenty of time for that, after we find out the truth about her," he said. "Have a good time, you two."

Before I could rise to go after him for that remark, I felt Evelyn's hand on my arm, holding me back.

"Let him go." Her voice was low. "He's a beast. You can't change him."

I HUNG around Rancin's place for half an hour, and spent most

of it apologizing for Nick. I knew that he was excited about our

findings and didn't entirely blame him for blowing up. Perhaps it

did look bad, my fighting in Evelyn Rancin's defense, when I was

engaged to marry Nick's sister.

Somehow I couldn't picture the pleasant, rambling house as a hiding place for corpses. I chose to believe that Evelyn was a good kid at heart, and resented intruders even as I did. Anyhow, the visit ended pleasantly enough and I started across the swamp toward Rigger's Bay feeling that we would have to search further for the secret to the empty graves.

It was nearly noon, and I stopped along the way to strip several bushes of huckleberries. I took my time, and before I realized it, the sun was dropping and the swamp was growing cool and moist with evening winds. The pounding of the sea told me that I must be half a mile below Rigger's Point and probably close to the cliff that looked out upon Cory Rock. I started to move more swiftly. The sun was gone before I reached the road.

I wanted to turn and follow it home. I was both mentally and physically exhausted. I couldn't escape the magnetic pull that the cliff had for me. Here, or at least within this unholy mile, seven men had died in an attempt to reach the vision of Cory Rock, Lawrence Rancin's Moon Slave.

I crossed the road and started to climb slowly over the huge boulders that had been thrown up by the angry sea during centuries that man knew nothing of. The sea was wild tonight, and clouds scudded across the sky, leaving the moon clear and yellow, then hiding it completely from sight. I moved slowly, staying close to the shore and working my way upward to where Rigger's Point sends its jutting, granite face far out over the water.

Almost to the top of the cliff, I stopped suddenly, my heart pounding with excitement. Something white flashed momentarily, then disappeared below the top of the boulders. I waited, straining my eyes, trying to see it once more.

There was a woman out there, close to the edge of the sea, working parallel with me toward the top of the cliff. Slowly, cautiously, I moved toward her. Now I could see her clearly. Although the night was too dark for me to recognize her, the occasional flashes of moonlight revealed that her hair hung to her shoulders and was blowing wildly in the night wind. She seemed clad in a white bathing suit, or perhaps she was entirely unclothed.

We had both reached the cliff top now, and I saw that she was staring out toward the sea. Staring straight at the high bulwark of Cory Rock. The rock was fax below, and nearly two hundred yards from the shore. I tried to secure a vantage point where I could see what she was looking at.

It was impossible.

Below us, the water was deep and it sulked off shore for suspended seconds to crash in against the cliff with terrific force. The moon was overhead now, a huge, baleful eye staring down at us. She turned toward me for an instant and the outline of her face was crystal clear.

It was Jean Fanton.

Almost before I could realize what she had planned to do, she turned and was leaning over the precipice. I heard the water crash against the cliff, then roll out again. My heart jumped into my throat and I cried out quickly in alarm.

"Jean—Jean, for God's sake!"

I was too late.

SHE spread her arms aloft and dove cleanly downward toward the

surface of the sea. I ran toward the spot where she had stood,

and leaning far over, tried to see where she hit the water.

The moon was in league with her now, for suddenly it vanished behind low flying clouds and I could see nothing ten feet below the edge of the cliff. I waited for seconds, minutes, for her to cry out. No sound came from below. The sea gathered itself up once more and lashed in furiously, battering at the cliff.

I couldn't help Jean Fanton now. My worst fears were realized. There was no doubt in my mind who the Moon Slave was, though why Larry Rancin had called her by that strange name, I couldn't guess.

I turned and went swiftly toward the house. I saw a light burning in Nick's room, and entered the darkened living room with as little noise as possible. I was afraid to awaken Jean's father, so I removed my shoes and went silently upstairs. Nick's room was at the end of the corridor, looking out over the Bay. I waited at the door, then knocked lightly. There was no answer.

I knocked again, then touched the door with my hand and it swung open without a sound. I looked in.

Nick wasn't there. The bed had not been slept in. I was about to turn and leave when a sparkling bauble on the floor caught my attention. It was just inside, partly hidden in the carpet.

I started to close the door, but something about that object fascinated and horrified me at once. I bent over and picked it up. It lay in my hand, a sparkling, glasslike bit of stuff shaped like a crescent half-moon.

It was like one of the glittering little objects that I had seen before, flashing from the waist of the Moon Slave.

Did Nick Fanton know his sister was the Moon Slave? Was he trying to protect her by throwing the guilt upon Evelyn Rancin?

The outside door down stairs opened and closed softly. I hurried into the hall and toward my own bedroom. I left the door open a crack after I entered. I stood there, not turning on the light, wondering who would come up the stairs.

I expected to see Nick, and when Jean came up, clothed in her aged corduroys and faded blue shirt, it threw me off guard. I was so overjoyed to see her alive after the incident at the cliff, that I lost my sense of caution. Throwing the door wide open, I ran toward her.

In an instant she was in my arms, her soft hair against my shoulder, crying as though her heart had been broken.

"Lee... Lee, call father. Do something. Nick fell over the cliff and I can't find him. Lee, I think Nick's dead like the others."

A hatred welled up inside of me. A hatred not for Jean, but for the thing she represented to me. I pushed her away from me suddenly, wanting to strike her down.

I had seen her out on the cliff alone. Nick hadn't been there then. I had hoped to prevent any more men from following unlucky Larry Rancin's trail to death.

Now Jean Fanton, the woman I worshipped, had enticed her own brother to his death.

I watched her sink to the floor at my feet, her head buried in her arms. Sobs shook her body. Her long, dark hair was fanned out on the carpet, wet with sea water.

"Jean," I said, "get up on your feet. Tell me what you've done."

She didn't answer at once. Then, sobbing pitifully, she lifted her head and stared up at me.

"I didn't mean to do it, Lee. God knows I didn't mean to do it. Nick's dead and I killed him. I..."

She saw my eyes and read what was in them. Her head sank to the floor again and the sound of her crying mingled with the steady, heartless pounding of the sea.

The phone downstairs was in the hall near the front door. I stepped past her and walked down mechanically, wishing it had been me instead of foolish, headstrong Nick Fanton.

WE COULDN'T locate Nick Fanton's body. Men came from town

that night and for some reason unknown to myself, I lied,

refusing to implicate Jean in the killing of her brother. Her

light was on when the searching party came back from the cliff.

We asked her to come down to the living room and when she

appeared, I was struck by the change that had come over her.

She was fully composed now, and dressed carefully in what I had always chosen to call her "Sunday gown." She seemed to realize that I had protected her, and she answered Minister Niles and Sheriff Beasley calmly. She told how she had followed Nick to the cliff and tried to prevent him from jumping into the sea.

Then they were gone, with the promise to send up the coast guard in the morning to make a thorough search for the missing body. Old George Fanton stood up well under the strain of the night's events, and after the others had left for town, the three of us sat in the living room, no one wanting to talk, no one wanting to go to bed.

There was fear in all of us now. I knew that I couldn't protect Jean forever. I'm afraid George may have suspected but he demanded nothing from his children and waited for Jean to tell him what she wished him to know. As for Jean, she sat curled up in a despondent little bundle before the fire, staring at the flames and asking nothing from us but to be left alone.

An hour passed and the storm clouds vanished. The moon was clear now, hanging out over the bay in an almost perfect sphere. I went to the window and stared up at the sky. I heard Jean stir, then rise from her place before the fireplace.

"Lee," she said. "I want you to go with me. I have something to tell you and something you must see."

"I don't care to go out," I said. I wasn't angry. I didn't have any anger left in me. I was all washed out and replaced by a sick, down at the heel feeling, as though the world had ended and I was left out in space.

She came to my side and put her hand on my arm.

"Lee," she said again, "You're trying to be noble and you're quite well satisfied with yourself, because you think you're protecting me. I insist that you go with me."

I shrugged. What harm could she do now? If she planned to get me out of the way, what difference would it make?

A strange, desperate loneliness came over me. I'm not emotionally high strung, but all that had happened had not deadened my love for her. To me, regardless of what strange powers held sway over Jean Fanton's mind, I couldn't go on without her.

I turned swiftly and swept her into my arms.

"Jean, I don't give a damn what you've done. I don't care what you do. I can't hate you. I—I..."

She struggled gently to push me away and when we were separated, her face was quite cold and emotionless.

"Then you'll go with me?"

"Where?"

"To Evelyn Rancin's," she said.

THE swamp was lonely and cold. We crossed it, not daring to

speak to each other until we were in sight of the Rancin place.

Then Jean stopped.

"Promise to say nothing," she said. "You must let me talk It's the only way I have to show you what you must see."

I promised and we went on. She knocked at the door. There was no answer. I went around the house, looking into the rooms that were lighted, then knocked at the back door. Still no response came from within. I knocked again, and heard footsteps inside.

The door opened and Jean slipped out.

"The front door was unlocked," she said. Her voice was filled with a new excitement. There was an undercurrent of fright that I had not expected. "I've looked in every room. Evelyn has gone. We'll have to hurry."

I didn't question her. She started backed across the swamp and I stumbled after her as she moved swiftly ahead of me. She was familiar with every path and every pit in the weird place. We reached the road. Across it were the same granite boulders among which I had made my way earlier that same night.

It dawned on me that perhaps the trip to Rancin's was to throw me off guard. I alone knew Jean's secret. Was she leading me to my own death at the top of the cliff?

She went on, upward through the stone field, and stopped only when we had reached the crest of the cliff. She turned to me almost savagely.

"Lee Judson," she said. "If you're a coward, this is the time to turn back."

I waited without speaking, listening to the sea far below and remembering how she had dived from this spot and had come back to the house alive and unscratched.

"You used to swim with me at the village," she said. "You took diving at college. Lee, will you go over the cliff with me?"

I tried to smile, but I'm afraid my face was pretty chalky. It wasn't fear—that is, not fear of death. I feared now that I would lose her. As much as I hated what she represented, I couldn't feel that she would destroy me as she had the others.

"If you can think of any easier way to commit suicide," I said, "I'd rather."

"It's a long drop," she was talking as though she hadn't even heard my protest. "The waves come in hard, then as they go out, the water is calm for a few seconds. You have to hit the water when it's calm, and hit clean. There's a forty foot depth just at that time, and you won't land on the rocks."

I took her wrist in my hand and squeezed it tightly.

"I'm game," I said, "so long as you're going with me."

Her answer was a quick step toward the edge of the cliff. The waves struck with sudden fury, then retreated. The surface of the water was calm and the moon made it look like spreading quicksilver. She leaned forward and dived cleanly. I waited, as she hit the dark water and watched the circle widen where she disappeared. Then a tiny brown head bobbed on the surface.

I kicked off my shoes, waited for the next wave to subside and followed her with the best dive I'd ever done in or out of college. It was a good one, and I felt fairly safe during the moment before I hit the water. Then I was holding my breath and sliding down and down. I came up sputtering and fighting for breath. Jean had reached the rocks and was standing on a low ledge against the cliff. A wave caught me and threw me after her. I hit hard, but luckily I had my second breath and was able to hold out. Her hands grasped mine and she drew me out of the water.

What was to happen? She had her chance to kill me, and she had let me live. For some more terrible fate?

"Stay close to the cliff. When the waves come in, grab the rock and hold on. Follow me."

I knew she had been here before, for she followed the narrow ledge along the base of the cliff as though it were a wide path. I was behind her, choking and fighting as the waves tried to tear me away.

Where the ledge fell away to leave only smooth, polished rock, she stopped again.

"Take my hand," she said. "We'll dive together. Take a good breath. It's a long way under."

NOW it had come. She would swim with me under the edge of the

cliff, then a sudden push against a familiar hidden rock, perhaps

a deadly whirlpool. I didn't give a damn. Most of the strength

had been knocked out of me. I breathed a deep breath, took a firm

hold on her wrist and jumped into the water.

Jean is a fine underwater swimmer, and I stayed with her easily, following while she guarded me deep under water, then suddenly back toward the face of the cliff. Her wrist was strong under the touch of my fingers. She swam with her right arm. Down here, the water was calm and without motion. Staring ahead, I saw a small opening under the cliff and knew where we were going. We entered the tunnel and though my lungs felt as though they were ready to burst, I held out, waiting for her to go to the surface.

I concentrated on her, watching the slender bronze arms and legs work smoothly under her drenched dress. Then there was light ahead—a dim blue light. We shot upward.

She touched my shoulder gently just before we reached the surface and pressed her hand to her mouth. It was a signal for me to come up slowly and to be quiet.

Then my head was out of water and we were both close to the edge of a circular pool of water. A stone outcropping hid us from the cave above, and the same strange blue light filled the place. I heard a voice say:

"O Moon—O Slave of the Moon—this is another wonderful night."

The voice was harsh and I couldn't tell whether the words were spoken by a man or woman. Then, with the water cleared from my eyes I saw Evelyn Rancin.

She had come to the far side of the pool and was standing there, her dress soaked with water, her arms hanging despondently at her sides. I had never seen such sadness on the features or in the eyes of a living person.

She saw us and her voice rose in a scream of fear.

"Look—there in the pool!"

I was so startled that I didn't think very clearly. I grasped the edge of the rock and drew myself up, throwing my body on the floor of the cave. With my eyes still on her, I sprang to my feet and started to sprint around the edge of the pool. I heard Jean cry out and knew that she was trying to follow.

"Lee—be careful I Behind you!"

I turned, but I was too late. I saw seven men sitting stiffly around the circular cavern.

Seven dead men.

They looked alive, for they were seated on carved, black stone chairs.

Yet, I had seen two of them buried and knew the others for the victims of the Moon Slave. All this happened in an instant. Then a face loomed up before me and a club descended against my skull. I went down, fighting to keep a foothold on the slippery rocks. Then I knew the face behind that club.

I was staring straight into deep, Satanic eyes of Nick Fanton.

I heard a far away voice. It was a deep, almost reverent voice, repeating mechanically a sentence that drove fear into my brain.

"Victim of the Moon Slave. By the power of the moon that controls the sea, and the sea that controls man, open now your eyes. Victim of the Moon Slave...."

I OPENED my eyes slowly, and felt my body thrust into an

upright position. My arms were placed on what felt like slimy,

cold arms of a chair. Then the haze before my eyes cleared and I

knew with certain horror that I had been placed on a seat of

honor in the very center of the ring of dead men.

Was I alive or dead?

Had I died as I fell and was I under the death spell of that voice? No, I felt warm blood pumping once more into my veins and realized that, fortunately for me, I had appeared dead a moment ago. I sat rigidly, trying not to blink, staring straight at Nick Fan-ton. He was before me dressed only in white shorts with a mass of tiny half moons hanging from his hair. More of them were sewed around the shorts. His tanned body glistened in the blue light of the cave, and for the first time, I realized what it is like to stare into the deep set eyes of a madman.

He turned away and I had a chance to blink rapidly and to stare around at the cavern. Evelyn Rancin was still standing by the pool waiting for God knows what. Jean was on the floor. Her wrists and ankles were bound with bits of my trousers. She stared at me looking for some sign that I was living. If she saw me blink, she didn't betray me.

"Nick," she said. "Nick, please go away. Don't stay here. They'll find you sooner or later."

He walked toward her. He kicked her in the side and watched as she buried her face in her arms and cried.

"You're a fool," he said savagely. "Evelyn was a fool also. Love has no place on the throne of power. Love for a sister or for any woman."

He looked across the cave at Evelyn Rancin.

"Go on, fool," Nick shouted at her. "You said you were going to end your life. Jump into the pool and drown, and good riddance to you."

He turned to me and I became rigid again, trying to act as dead as the corpses around me.

"Welcome to the Moon Circle, Lee Judson," he said softly. "You didn't suspect Nick of robbing those graves did you? You didn't know that the vision of loveliness that dragged men from their graves was no vision at all, but Nick Fanton. No earth woman could swim that torrent to Cory Rock. Not even Nick Fanton, agent of the Moon Slave, could swim it, not until tonight."

Jean cried out.

"Nick—no, Nick, you can't swim it. You'll drown."

I was trying to control myself now. I must learn the truth before I sprang from that death chair and throttled Nick Fanton for what he had done. But he was talking smoothly, confidently.

"You are dead, Lee Judson. Ready for the sacrifice to the Moon Slave. You know little of the Moon Slave, Lee. She came to me in a dream one night."

"'Nick Fanton,' she said. 'The Moon Slave demands ten men. Ten strong men—dead and brought to her beneath the cliff. You know the place, Nick Fanton. Bring those ten men, and as your reward, you will be able to swim to the rock. Swim into the arms of the Moon Slave.'"

He paused, and his breath was coming hard.

"Jean had to interfere, didn't she, Lee? She followed Evelyn to the graveyard that night, because Evelyn knew my secret. Evelyn loved me, and she didn't dare to tell Lawrence. Jean knew my secret and was trying to save me from myself."

He whirled on his sister.

"You're wrong," he said, "in trying to cheat me of my sublime reward. You and Evelyn reached the grave too late. You pleaded with Evelyn not to tell anyone what she knew about me. You both decided to save me. All the time, I didn't want either of you. I didn't want you, understand?"

He was screaming, and his voice filled the cavern with furious sound.

"Now I have ten dead men. Tonight I swim to Cory Rock and claim the Moon Slave as my reward. I leave ten strong men here. Dead men to fulfill the contract to the moon and the sea and the Moon Slave. First I have to perform one duty to make sure no one returns to the village to tell my story. I may want to return myself some day, when I have tired of the prize I find on Cory Rock."

I had heard enough then, and inside me was the strength of a man who suddenly has all of his problems settled. He started to turn toward me and I lashed out with both feet. The blow sent him toppling backward and before he could regain his feet, I was after him, slipping and sliding across the cave. I went down hard, my knee in his stomach and felt the breath go out of him.

He struggled, gripping my throat with both hands. I tried to get away, but slowly, very slowly, he turned until I slipped and he was above battering my head against the stone floor.

He struck me twice with all his strength and my mouth was bleeding badly. Not once was I afraid that he would kill me. There is a strength that comes Into a man at a time like this. A strength beyond human understanding. I managed to lift my knee until it was against his chest. Then I lunged out with all my strength and his fingers slipped from my throat. He fell backward and his head struck sharply against one of the stone death chairs. The stiff corpse of Lawrence Rancin toppled forward and fell on Nick Fan-ton. Oddly, Rancin's body seemed to hold Fanton's inert figure against the floor.

I stood up, panting, and went to help Jean.

WE HAD Nick Fanton confined to a sanitarium at Bar Harbor. I

went down quite often to see him, but he would never speak to me.

Once he accused me bitterly of robbing him of his reward and

taking away his Moon Slave. He was never violent again.

Jean and I were married that fall. Before the wedding, Evelyn Rancin, Jean and I were together for an evening, talking over what had occurred.

I had helped the authorities remove the bodies of the nine men from the under-cliff cavern. It wasn't a pleasant task. Now it was all over.

Evelyn told her story simply. She had been in love with Nick for several years and Jean knew it. They both decided that though Nick was headstrong and ready to run away with Evelyn at once, a divorce would have to be arranged. Jean and Evelyn suspected Nick, because he started acting so strangely whenever a man succumbed to the charms of the Moon Slave and died by diving from the cliff. Jean traced him to the under water cavern, but because he had not actually murdered these men himself, she couldn't make herself turn him over to the authorities.

They had seen Nick steal Larry Rancin's body, and yet they both continued to protect Nick. I understand that, though I'm not sure the authorities would have, if I told the full story.

Now that it's all over, there is one point that I never could clear up and I don't think it's within the power of man to do so. Nick Fanton was just an agent. He worked because, as some people would express it, he was an insane man following insane desires.

It went deeper than that. There is a Moon Slave of Cory Rock. I have seen her, and still see her when I feel strong enough to go to the cliff without fear of succumbing to her charms and diving to my death at her call. Men stay away from the cliff now, and to my knowledge, the Moon Slave has never visited anyone but Nick Fanton in his dreams.

Perhaps some day the power of the moon and the tides will work again in terrible unison. Perhaps that vision of loveliness and death will hover over the bed of a man and fill him with a desire that will drive him mad as it did Nick Fanton.

You can't control those things, or predict them.

The moon and the sea are powerful. They control people and events, and no man can explain the Moon Slave of Cory Rock any more than he can explain the patterns of the northern lights. Perhaps, like the rainbow of color that weaves itself into the northern sky, the Moon Slave of Cory Rock is not real at all, but only a pattern of extreme loveliness, reflected there by the moon.

Some lovers see romance in the face of the moon. Jean Fanton and I see death and destruction. We prefer to spend our evenings in the warm, friendly atmosphere of greater New York, and go to Rigger's Point only once a year, when we visit Jean's father and take boxes of new gowns and hats to Evelyn Rancin.

Evelyn is resigned to her place in life, and our visit is the one bright spot in her year. Her life is quiet and she makes regular trips to the grave of her husband. She sits for long hours at the very spot I stood that first moon-lit night and stared down at the grave of Lawrence Rancin, then up at the cool, unexcited eyes of the Moon Slave's bridegroom, Nick Fanton.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.