RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

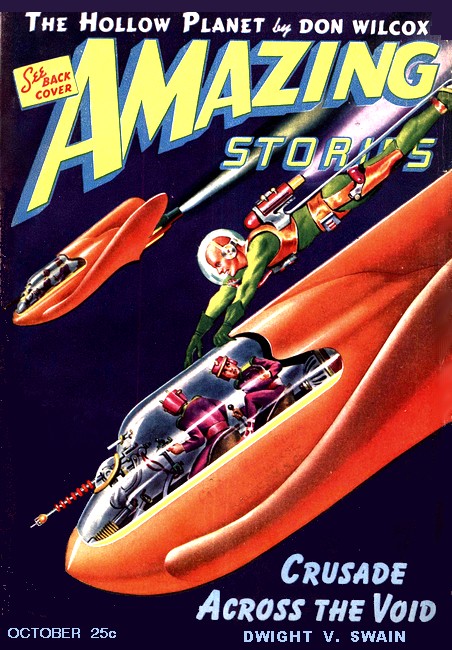

Amazing Stories, October 1942, with "Oliver Performs a Miracle"

FERRIS hesitated as though he couldn't have heard correctly. Then all four of the chair legs dropped with a loud bang and he stood up slowly.

"There's them who can't do a thing for themselves." He groaned. "Well, if you can't—you can't."

He went out the door, letting the screen plop back in Oliver's face. The pump hose came off its hook and clattered against the fender.

"Hey!" Oliver said angrily. "Take it easy there. Can't be buying new fenders every week."

Curley chortled, belly shaking with mirth.

"Since when," he asked, "have you ever bought more than a can of wax for this death-trap?"

The smaller man's face turned livid.

He straightened a full five-foot-five, and his pale-blue eyes turned two shades darker.

"I'll thank you to be more careful how you describe my property. There ain't a better car been made than that twenty-nine Model A, and this one gets the best attention a fella can give it."

THIS was an old story to Curley Ferris. Brady chugged in every Monday morning

on his way to town. He always tipped the small, dignified face at the same

angle and launched a new battle in defense of the A. He and the old Ford went

together in a manner that made Curley's big heart warm when he saw them roll

into the drive. Wordlessly he hung the hose back on its hook, turned and

wobbled back toward the small garage.

Hoisting his bulk once more into the chair, he grabbed the paper. It was too late. Oliver was at his side, sentences piling themselves on each other in one rush.

"You billy-goated old elephant!" His hands were shaking. "What do you expect of a car that's ten years old? Want me to buy one of them high fallutin' Cadeelacs? Poor man like me can only afford one car. There's a limit to what I can stand."

Curley studied him coolly over the specs.

"Talking about limits," he grunted, "when I see you driving in here winter, summer, and spring in that danged old rattle-trap, I just wonder if there is any limits. That car has sure passed 'em all. It'll take you straight to Heaven—or else to Hell, wherever they finally decide to put you."

"Why—why!" Oliver sputtered like a hot griddle. "The engine under that hood is as clean as the day they put it in."

"I'm clean too." Curley's eyes were twinkling, but his jaw had frozen in mock anger. "But on the road I can't do over three miles an hour."

"If you're saying my car ain't fast!" Oliver's neck was turning a lovely pink. "Well! Maybe not—but she ain't no darn road-hog either. She just gets me there and gets me back."

"And shakes you up like a butter-churn, doin' it," Curley added.

Oliver's ears twitched violently.

He tried to speak in a rich, deep voice but somehow his anger betrayed him, and a high falsetto resulted.

"I ain't a rich man. You can't get more out of a car than you put in, and that watered gas of yours... It is a well-recognized law of physics that no mechanical instrument will give up more power than is put into it. That's why perpetual motion machines and stuff like that don't work. It's a wonder to me that my A gets enough energy out of your gas to even shake like a butter-churn!"

Oliver was talking fast, airing his scientific knowledge.

"You've got to use energy to produce energy. For instance, if you burn gasoline in a motor, it changes its identity. It becomes energy, not matter. But it doesn't all change, because much of the matter is only changed into other matter—fumes, and so forth. Some of the energy is lost in friction, too.

"Some scientists have said that energy could be changed into matter, to reverse the process. But they haven't found out how to do it yet. Unless maybe you know the secret underneath that watered pump of yours..."

Curley was in high gear now.

"As far as getting more out than you put in, why don't you run the thing on water altogether? Three gallons of gas a week ain't making me rich."

The argument had progressed beyond Curley's original desire to heckle Oliver. He was relieved that the phone on the far wall started to ring. One long—two short—that was his signal.

"See who it is." He hated like tarnation to get up.

Oliver frowned a little and went across the greasy floor.

Picking up the receiver he said,

"Yep?"

Then his small face turned a shade lighter.

"Who? Thunderation! Yep—Yep! Well I'll be hanged!"

He hung up slowly, turning with a sickish yellow light on his face.

"Well?" Curley demanded. "Don't stand there like a horse with distemper. Who was it?"

"Convicts," Oliver said hollowly. "Two men escaped from state's prison. They are headed this way."

FOR the first time this morning Curley acted with some pretense of speed.

With shirt-tail flying from the creaseless pants, he was into the backroom

like a shot and out again with the shotgun.

"Let 'em come" His puffy face had tightened and grown fierce. "We'll blow 'em to kingdom-come!"

Oliver stood listening. The prison alarm sounded faintly across the farmland. Sirens were already screaming faintly far down the road. He sidled behind Curley's bulk, feeling a little more concealed. He shivered.

"Suppose they might go the other way?" It was an expression of hope.

"Nope—not a chance." The hand around the shotgun tightened. "This is the only good road. They'll try to lose the police in that mess of county roads south of here."

The sirens were closer now, and Curley's gun wavered a little. He'd shot a rabbit once, and had almost cried.

"Look!" His hand clutched Oliver's shoulder. Two men jumped out of the bushes and ran toward Oliver's car.

Oliver started to jump up and down.

"Shoot!" he ordered. "Shoot 'em before they get my car."

The heavy gun came up, hesitated, then dropped again. Perspiration stood out on the fat man's face.<7P>

"I can't do it."

They were across the drive already, and climbing into the flivver.

"Don't be scared," Oliver howled. "Let 'em have it."

The Ford coughed, started to idle spasmodically.

"I ain't scared. Just remembered—the shells are all up in the bedroom. It ain't loaded."

Something in Oliver's timid heart snapped. Like a hen protecting its young, he shot toward the door. The screen cowered before the onslaught. With the full power his thin legs could muster he was after the retreating car. Sirens closed in from all directions.

In a low, flat dive he pitched forward into the rear seat. He hit the floor with an unhealthy groan of pain.

"Well—well!" The stoutest one of the pair of convicts turned and looked down at him. "I think it's a man."

There was a painful lump rising on Oliver's thinning scalp and another on the bony left knee. Now that he was in the car, he wondered why he'd ever left Curley. They were on the highway going ahead at a noisy, but fairly fast clip.

The driver looked over his shoulder at the frightened little man in the back seat. He was tall and had a thin, tight lower lip. There was a livid scar across his neck. Stout had pulled a gun from somewhere and held its short barrel aimed at Oliver's head.

"Say Grampa!" Scar Neck asked, "why don't you feed this trap a good tonic?"

OLIVER realized that for the time being he was safe. They were going about

forty miles an hour and that was the best the A could do. It was a matter of

minutes before the police would be upon them. He became quite brave.

"If you're so darned smart," he suggested," find a tonic yourself. This is as fast as I have to drive, not being a law-fearing man."

Instantly he wished he'd remained silent. He gulped and felt very ill as the gun poked forward against his stomach.

"How in Hell can we get some speed out of this Kiddy-Kar?" he grated.

Oliver had climbed painfully up onto the seat cushion now.

"You might try putting in a supercharger," he quavered. Then—"No-no—you ain't hardly got the time."

Stout turned on him, the tenseness of his yellow face silencing any further outbreaks. Heavy lips curled up, leaving a row of broken teeth leering at Oliver.

"Shut up, wise guy!" he ordered. "If we go out, you'll be right with us."

Oliver looked at the wavering tommy-gun. Stout's thick finger was rippling over the trigger, shaking with fear. The little man realized that Stout meant what he was saying. Oliver wished sincerely that he had taken Reverend Beecher's advice and attended church other than on Easter Sunday—he wished he could erase his past sins—that time twenty years ago when—

One of the police cars was close behind now. He could hear its wheels howl in protest at the curve they had just come around. Stout would shoot him before they would have a chance—

You can't get more out of a thing than you put in, he had assured Curley. Now he wished that by some miracle he could. If only something could happen to save his neck.

The gun came forward, Stout's eye leering at him from its further end.

"Do something!" Stout commanded, "or I'm letting 'er tear."

OLIVER'S right eye focused on the dashboard. The gas gauge was bouncing up and down wildly. The eye traveled toward the speedometer, the key—THE KEY—THAT WAS IT. If they turned off the key now, the Ford would backfire like all get out. Perhaps in the excitement—! But they wouldn't be foolish enough to do that. Maybe if he told them to turn it to the left...He'd never tried that himself, but—

"The car's got two motors!" Oliver howled. His voice held a desperate eagerness. If they would only believe him. "Turn the key way to the left and the other motor will come on."

Scar Neck looked at Stout. His lips were quivering strangely. The police car was almost up with them now. Men were visible at the windows, rifles poking toward them.

"He's nuts," Stout said in a strained whisper.

Scar Neck shrugged his shoulders.

"Maybe not," he said.

He felt for the key with one hand and gave it a violent twist.

Oliver felt his body slam back against the cushion as the flivver took a sudden gulp of gas, shivered from bumper to trunk and leaped forward like a racing car.

Scar Neck's foot fell from the gas pedal, but the car only went faster. Oliver saw the controls whip into reverse.

"Cripes," Scar Neck howled gleefully, "we got a bird on our hands."

Oliver was thunderstruck. He had prescribed the impossible and it was happening. He was getting more out than he had put in, and he didn't think he liked it. Now they had the road to themselves. The last police siren had faded out, and the sounds of the chase were criss-crossing among themselves far behind.

The A flew through Fayetville with everything but wings to push it faster. They collected a stray cat and a chicken en route, and dove like fury into the open country beyond. Oliver wondered dazedly what the citizens of Fayetville would think now. Who said the A wasn't a Super Car?

WITH the police lost far behind, Scar Neck felt safer. "Better stop and collect ourselves," he announced finally.

He pressed the brake pedal and released his foot from the gas. Nothing happened. Nothing, that is, except a marked increase in their speed. He pushed the brake harder. There was a strong burning odor and the brake lining went up in a puff of smoke. The speedometer had long since hit its limit and blown out its own heart. They must be doing over ninety. Oliver wished mightily that he could be back at the Gas Palace.

"We gotta stop this chariot," Scar Neck shouted. They hit a curve on two wheels, straightening out again. His face held a look of horror. The front left fender got tired of holding on and fell behind with a loud rattle of tin.

"Do something!" Stout considered Oliver the miracle man by now. "I got a wife and two kids."

Stout's face was even more yellow than before, but the teeth had retired between the tight, anxious lips. He waved the gun again, and Oliver wondered if it was worth all this trouble. He had no idea what to do next. Another fender left for parts unknown, followed by a very important-sounding gadget, somewhere below them.

"I—I can't stop it," he wailed. The wind shrieking into his face, cut short any further explanation. The top had ballooned up from the flivver and settled in a ditch fifty feet behind. Telephone poles were rushing past like an animated picket fence. A lone farmer, watching them from the roadside, almost twisted his neck loose in an attempt to follow the flying flivver's trail.

Stout had the gun aimed at Oliver's neck again, but the little man rather welcomed the idea of getting shot. Anything else would be welcome right now!

They were skimming the concrete now, and Scar Neck seemed to exercise all he had to keep them out of the air. The motor roared in protest. Wind howled over the open-topped car until it sounded like a diving Spitfire.

Stout lost his nerve. His tear-steeped eyes swept over Oliver pleadingly.

"We don't mean you no harm. Sure—we're from the pen, but we ain't really bad boys."

Oliver took courage. His brain turned over slowly. He had bought only three gallons of gas. It would run out in a minute and they would have to stop. Why not let them go on thinking he was the brains of the outfit?

"Shoot some holes in the gasoline tank."

He ordered Stout to do it, in as superior manner as he could, controlling the urge his voice had to break on the high notes.

STOUT bestowed a thankful, tear-stained glance upon him. He picked up the

gun, aimed at the fuel tank up under the dashboard and cut loose.

"Rat-tat-tat-tat—"

Somewhere behind, the last fender hit the road and bounced away into the ditch. Gasoline trickled slowly out of the holes in the tank. Then something happened that added to the already perplexed trio's worries. Gas continued to spurt from the tank. It flowed freely, splashing out over the men in the front seat. Finally it came out like a streaming fire hose, gallons and gallons of it spouting over the car and flying into the road behind. The Model A had gone completely off the beam.

Three gallons of gas left a half hour ago. Now it was flooding them with more fuel than three tankers could carry. Oliver bowed his head, waiting for the end. And while he waited, he thought.

Somehow, the turning of that key to a position he'd never tried, simply because it had never occurred to him, had performed the scientific miracle he'd mentioned to Curley—had reversed the normal processes of energy and matter. Here was the A changing energy, perhaps free energy from the air, back into matter! The car was making gasoline by the gallon! And the net result was that the cylinders still churned furiously, from energy surging through them to become matter, driving the car as though the normal processes of physics were still going on.

Something wrenched out from under his feet, the floor boards dropped down and he was counting checker-board slabs of concrete flashing under him. He yearned to drop through the hole and disappear forever. Stout was on his knees, bending over the seat back in a position of prayer.

"Please save us," he begged. "We'll give you all the stuff we stole."

A car loomed up far ahead. It was cruising along in the same direction as they, at a sedate speed. The road narrowed in between two high rocky walls. It was getting dark. Everything had fallen out of the flivver but the motor.

Thoroughly cowed, Stout had curled into a miserable ball to escape the spurting gas that still belched from the bullet-torn tank. Scar Neck leaned against the wheel, eyes bugging at the car ahead. If he tried to swerve around at this speed, they'd roll over into the rocks and slice apart like soft butter.

AN idea turned over slowly in Oliver's mind. It hesitated—caught

against a brain cell—and lodged firmly there. He mustered the remaining

strength in his frail arms and pulled himself upright. The idea was so simple

that he felt like crying. He shouted over the howl of the wind into Scar's

ear.

"Turn off the key."

Scar's body snapped forward. One hand crept toward the dash, touched the key and turned it around. His face was shining with gratitude.

The flivver coughed like a dying dinosaur—leaned forward on its front wheels—and backfired like an eight-inch gun. But it started to lose speed.

The other car was too close to avoid a collision. The rear end of it seemed to push back. It sat down on them abruptly and refused to get up. Oliver saw Stout flying over the back of the seat...

CENTURIES later he regained consciousness. It was very dark. His head had

popped through something that felt like a square of cardboard. The

"something" was cutting his neck painfully.

He remembered the accident. Good Godfrey! He was still alive, and lying on his back in the deep ditch.

He jerked the horse-collar thing from his neck. It scraped his face, and came loose. He saw it was the inner side of a car door. There was a large, white circle painted on the surface and his head had gone straight through the bull's eye.

With bleary eyes, Oliver tried to read the white letters painted around the white circle. His face relaxed and the bewilderment vanished. Stout and Scar Face, if they were still alive, would be well taken care of, for a comforting message greeted his eye. STATE POLICE PATROL, it said. The car they'd crashed into had been a police car.